- Contract Law Research Topics Topics: 113

- Crime Investigation Topics Topics: 131

- Intellectual Property Topics Topics: 107

- Supreme Court Paper Topics Topics: 87

- Death Penalty Essay Topics Topics: 142

- Juvenile Delinquency Research Topics Topics: 133

- Criminal Behavior Essay Topics Topics: 71

- Capital Punishment Essay Topics Topics: 65

- Criminal Justice Paper Topics Topics: 218

- Court Topics Topics: 140

- Civil Law Topics Topics: 54

- Gun Control Paper Topics Topics: 168

- International Law Essay Topics Topics: 117

- International Relations Topics Topics: 176

- International Organizations Essay Topics Topics: 97

243 Police Research Topics + Examples

If you’re a criminal justice student, you might want to talk about or write a paper on the work of police officers and the hot issues in policing. Luckily, StudyCorgi has compiled an extensive list of police topics for you! On this page, you’ll find law enforcement essay topics, as well as questions and ideas for presentations, research papers, debates, and many more! Outstanding police essay examples are also waiting for you below!

🏆 Best Police Topics to Write About

✍️ police essay topics for college, 👍 good police research topics & essay examples, 📌 easy police essay topics, 🎓 most interesting law enforcement topics, 💡 simple law enforcement research topics, ❓ research questions about police, 🔎 law enforcement research paper topics, 🚔 controversial policing topics.

- Why I Want to Be a Police Officer

- Police Recruitment and Training

- A Police Officer’s Education and Duties

- What Is the Police Authority?

- Enhancing Police Training Program Proposal

- Conflict and Power: Police and Community Collaboration

- Police Officers Treatment Towards Civilians Based on Social Class

- Police Patrol Effectiveness Research Assessment The paper recaps debates that have arisen on the police patrol effectiveness in crime prevention, by investigating research on the said issue.

- Police Officers’ Wellness and Mental Health An increasing number of police officers are facing depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and even suicide.

- Public Role and Control of Police Citizens of democratic states have a right to exert control over the police. This claim is based on the fact that police are a part of the government.

- Laptop Computers in Police Cars: Benefits & Drawbacks This paper will investigate these problems and their prevalence with respect to the utilization of laptops in police vehicles.

- Police Professionalism and Ethics of Policing Accountability must persist given the discriminatory patterns among officers, who should be allowed room to improve as long as their good faith can be observed.

- Police Service Transformation: Research Onion The research onion depicts the research strategies and approaches that will be employed in this study. They are discussed in more detail in this paper.

- Police Corruption: Understanding and Preventing Police corruption remains one of the leading challenges, affecting law enforcement agencies in the United States and around the world.

- Essay on Police Brutality in the United States Police officers are allowed to use “non-negotiable coercive force” to maintain public order and control the behavior of citizens.

- Police Officers: Qualifications and Responsibilities The police are in charge of upholding law and order, protecting the public, and stopping, spotting and looking into illegal activity, making it a dynamic occupation.

- The Police Sexual Harassment: Case Study This paper reviews a case involving sexual assault by a police officer with the view to discussing its cause, results, and what could have been done to prevent the wrongdoing.

- Textual Analysis of the Song “Police” by Suprême Ntm The purpose of this paper is to analyze the song “Police” written and performed by a French hip-hop band Suprême NTM. It is dedicated to the problem of police brutality, racism.

- The Phenomenon of “Defunding the Police” The work Defunding the Police aims to explore the meaning of “defunding the police” and arguments and counterarguments surrounding this initiative.

- Mental Health and Well-Being of Canadian Police Officers The paper presents the problem of mental health in Canadian police officers. Even before the pandemic, stress and anxiety were common among law enforcement officers.

- The Six Virtual Police Department The six departmental units include the Chief of Police, Special Operations Division, Patrols, Investigations Division, Civilian Unit, and Support Service Division.

- The Use of Force in Police: Theoretical Analysis This discussion evaluates force standards and police leadership responsibilities through the prism of deindividuation and contagion.

- About Police Chaplaincy Program The article argues for launching a police chaplain program to connect the community with the police and provide survivors with the emotional and social support they need.

- Organization Effectiveness of a Police Department The organization is a core and framework of effective performance. The organization allows the police department to ensure effective management and organization of human resources.

- Western Australia Police Communications Centre’s Change The WA Police Communications Centre is a vital organ of the regions police force. This essay seeks to analyze the challenges that affect the centre.

- Police Administration and Key Effectiveness Factors When evaluating the impact of a police force, the best indicator would be to examine repetitive police action in preventing the same types of crimes.

- “Police Solve Just 2% of All Major Crimes” by S. Baughman Baughman’s article is about the insufficiency of the work that the police do to solve severe crimes since only 2% of cases result in a conviction.

- Police Response to High Speed/Hot Pursuits Police officers have the responsibility of defending the lives of citizens by maintaining law and order, however, in attempts to avoid being arrested.

- The Royal Canadian Mounted Police Officers The Royal Canadian Mounted Police is the national police force of Canada. They are responsible for policing in provinces, local communities, municipalities, and airports.

- Servant Leadership in a Police Organization The paper studies servant leadership, explicitly comparing and contrasting its traits with the major traits of a leader as outlined in the Good-to-Great book series.

- The Impact of Technology on the Police Patrol The use of complex technological systems by police officers to ensure the safety of citizens is a vital step in the development of the infrastructure of security and public order.

- Police Standards Should Be Modified There is a certain need for standards modification in the police that should be performed immediately. A particular amount of inequality exists in the departments of the police.

- Police Use-of-Force in Graham v. Connor & Tennessee v. Garner Cases A state police officer shot Garner to death as he fled the crime scene. Even though Garner was unarmed, the police officer felt he had the right to shoot him to prevent his escape.

- Benefits and Challenges of Using Drones for the Police Drones are becoming a state-of-the-art trend in policing; however, their implementation may face some difficulties regarding privacy and information security.

- Police Use of Force and Its Limits The paper aims to define what it means to be a police officer, discuss the legal use of nondeadly and deadly force, and determine the limits placed on police power.

- Leadership in the Los Angeles Police Department LAPD continues to develop and implement new and innovative programs in which its officers are trained to become good leaders.

- Policing From Above: Drone Use by the Police Drones are among the few technologies that law enforcement agencies could use to alleviate many of the challenges they face in their ordinary duties.

- All Police Officers Should Wear a Body Camera This paper suggests that the use of body cameras positively contributes to the reinforcement of procedural justice, as the prevention of unethical behavior and police brutality.

- How Does ‘Police Culture’ Influence Police Practice? Police culture is influenced by a number of social and political factors which determine its main functions and internal structure.

- Mentoring Programs in Police Departments The given proposal revolves around a one-on-one mentoring program that can be used by police departments to improve officers’ competence.

- Courtelaney Pass Police Department: Potential Problem Solutions There are four essential problems in the Courtelaney Pass police department: racial tensions, questionable investigative and enforcement practices, poor community reporting, and the lack of diversity.

- Age Influence on the Support for Police Action This paper addresses to what extent age influences the support for police action. The hypothesis is that old aged people are in support of the idea of police action.

- Police Misconduct and Its Affecting Factors Police discretion is a necessary element of the policing activity. Many situations which officers encounter on a daily basis require judgment and appropriate decision-making.

- The Wokefield Police Department’s Work in Memphis The Wokefield police department has a law enforcement mandate in Memphis. The region has experienced an upsurge in juvenile offenders, especially in the carjacking.

- Observation of Protest Against Police Brutality The event was a protest against police brutality in downtown City Hall. The event’s focal point was the ongoing issue of police brutality against Black people in the country.

- Dealing with Stress in Police Training Police officers are trained to handle stressful situations in different ways, and the approach used in their training has been a topic of debate in the recent past.

- The Houston Police Department’s Services and Challenges The Houston Police Department offers critical services in Texas and assures the people of peace and stability. The police department, however, faces several challenges.

- A Police Failure in the Uvalde Mass Shooting The mass shooting in Uvalde is a prime example of how neglect of proper policing guidelines and management strategies can cause dire results for the local community.

- The Police Department’s Ethical Challenges Policemen should not allow immoral behavior to jeopardize their responsibilities. Officers must safeguard their relationships with the local people who depend on them.

- Police Brutality and Racial Bias Considering the long history of slavery, several generations have inherited racial prejudice towards Afro-American people, who have become the subject of abuse in many fields.

- Police Management in Killeen, Texas Killeen police station workforce is made up of three different generations, including millennials, boomers, and generation X.

- Effect of Brooklyn Nine-Nine Show on Perception of Police By connecting eight seasons to various crimes, Brooklyn Nine-Nine positions the police station as an inclusive workplace that saves people’s lives and promotes dedicated workers.

- Police Brutality in the United States The existence of systemic racial bias in law enforcement leads to unequal treatment and a higher likelihood of police brutality when dealing with people of color.

- Police Brutality During COVID-19 Pandemic In the United States, there has been a perceived and observed police injustice towards minority communities, especially Blacks.

- Interactions of Local Police and Homeland Security Officials The purpose of this paper is to compare the interactions of the two agencies in lawkeeping and order by examining their structural responsibilities as captured in the state laws.

- Sociological Positivism Theory in Police Practice Sociological positivism is primarily concerned with how specific social conditions in a person’s experience might contribute to an increased proclivity for crime.

- Cultural Influences on Police Decision-Making The paper identifies cultural influences on police decision-making. There has been a deterioration in trust between the police and some social groups.

- Police Misconduct Against the Black Community Police misconduct has escalated against the Black community and other ethnic groups. Mistreatment by police officers is determined by two significant factors: race and sex.

- The Dallas Police Department Police Academy and Training Curriculum The paper states that the future of diversity hiring in law enforcement will be driven strongly by organizational structure and leadership going forward.

- Community Policing: Police Officers’ Role Orientations Community policing has shown to have multiple benefits for both local citizens and law enforcement in the activities to both prevent or respond to potential threats or disruptions.

- Aspects of Police Culture and Diversity This paper discusses the topic of police culture and diversity. In the American law enforcement system, some police departments do not appreciate diversity.

- The Secret Police in East Germany The Secret Police in East Germany, also known as the Stasi, was an organization established by military forces and ministers to exercise total control over the population.

- The Los Angeles Police Department’s Overview The Los Angeles Police Department is headed by the board of police commissioners, which comprises a five-member team appointed to oversee the department’s operation.

- Police Misconduct: New Rochelle Police Officer Case Study Officer Michael Vaccaro was driven by the desire to punish the criminal Malik Fogg; however, he used too much force.

- Motivating Police Officers to Serve and Protect The proposal focuses on the idea that Heritage PD could significantly benefit from the use of motivating factors when approaching police officer productivity.

- Police Officers’ Excessive Use of Force Although law enforcement officers are allowed to use lethal force, they should exercise that authority only when the suspect possess threat of harming others physically.

- Police Accountability and Reform The paper states that the police are experiencing a crisis that has made them under scrutiny and pressure from the public to make reforms.

- Discussion Misuse of Lies in the Police The paper discusses situations where police officers may misuse lying when dealing with mentally ill people or people in crisis.

- Improving Police Morale and Community Communication This paper’s purpose is to examine the police department on street patrol, and also to reveal the issue of mass dismissal of police officers.

- The Police in the Modern World The police in the modern world is a body endowed with certain powers and responsibilities. Its mission is to enforce the law, prevent crime, and ensure public safety.

- The San Diego Police Department’s History and Work This work describes the work of the San Diego Police Department, its brief history, and statistics about working there.

- Restructuring of Los Angeles Police Department Fiscal Budget The foundation of the paper is a breakdown of the Los Angeles Police Department budget, a proposal to reduce the budget and its effects.

- The Legality of the Scope of a Police Search The paper discusses the two court cases which demonstrate that the legality of the scope of a police search is a controversial legal question.

- Police Killing Black People in a Pandemic Police violence as a network of brutal measures is sponsored by the government that gives the police officers permission to treat black people with disdain.

- The History of Relationships Between Police and African Americans The paper describes the necessity to spread the knowledge of racism’s history and discuss it to ensure the next generations’ tolerance.

- Police Civil Liability in the Light of Monroe v. Pape People want to know that in trouble, such as, for instance, a robbery or car theft, police will come to their aid and guarantee protection.

- Collaborative Organizational Changes in Police The paper states that both Future Search and Open Space techniques are applicable and beneficial in military organizations such as the police.

- Police Officer With a Juvenile Police officers faced with a juvenile under arrest makes their decisions based on the balance of legal and situational factors relevant to the case.

- Researching and Analysis of Police Abuse The analysis of high-profile cases of police abuse allows assuming that there would not have been fatal outcomes if the officers had respected the basic rights of their victims.

- Police Misconduct in Criminal Justice Police misconduct is one of the issues involved in criminal justice, and there are various aspects and events entailing unconstitutional practices in law enforcement.

- The Influence of Police Bias on Disparity in Juvenile Crime: Methodology The issue of racial disparity in the criminal justice system remains a topical one. 64% of the charged youth are people of color.

- An Inside View of Police Officers’ Experience with Domestic Violence “An Inside View of Police Officers’ Experience with Domestic Violence” is an article authored by Horwitz et al., published in 2011.

- Internal Problems of Mississippiville’s Police Chief Hiring Process Mississippiville is in a difficult situation, including a tense social environment, in part caused by the ineffective management of the previous chief of police.

- The Civil Rights Movement: Minorities vs. Police An opposition between minorities and police appears to be a problem that started during the Civil Rights Movement and continues to modern days.

- Police Sexual Harassment Suit This paper analyzes the case of the ex-Round Lake Height’s policeman, Hossein Isbitan, who filed a Lawsuit against his boss despite other problem-solving measures at his workplace.

- Police Officer Characteristics and Evaluation Most people would prefer their police officers to be capable of making decisions and taking action, especially in tense situations where swift choices are necessary.

- Race and Police Brutality in American History Racism and police violence since the time of colonization has had intense effects on Black and Indigenous communities.

- Factors That Justify the Use of Deadly Force by Police Police shootings and killings of unarmed civilians arguably qualify as violations of the use-of-force standards that warrant the arrest and conviction of the perpetrators.

- Police Brutality: The Killing of Daunte Wright Police brutality is defined as the use of unjustified or excessive force by the police, usually against citizens. It refers to the violation of human rights by the police.

- US Police Brutality and Human Resources Connection Police brutality is one of the most pressing crisis problems in the United States, it requires additional research and immediate solutions.

- Police Discretion: Criminal Justice While in the academy and for their period of training, police are particularly skilled on how to handle various situations that they will come across.

- How Police Supervisory Styles Influence Patrol Officer Behavior The field supervisor, also identified as the patrol sergeant, directly oversees officers’ conduct, performance, appearance, and tactical operations assigned under their command.

- Discussion of Police Misconduct The paper discusses criminal justice system has developed various approaches that guarantee that police can be held accountable for their misconduct.

- Police Brutality on African Americans Police brutality against African Americans has been on the rise even after several constitutional and legal reforms made by the country to control it.

- Police Brutality Toward Black Community The black community needs help since they suffer due to police brutality, receive various kinds of injuries, and experience traumas.

- Analysis of Decision-Making Processes in Boston Police Department The paper covers the role of police in homeland and application of these systems to the Boston Police Department.

- “Learn About Being a Police Officer” by Kane Being a police officer is one of the most challenging professions because it requires dedication, determination, and sacrifice.

- Measuring Crime: Lynnfield’s Local Police Force Stop & Search Data The study aims to assess any obvious trends that may be associated with disproportionate and/or discriminatory exercise of ‘stop and search’ policy by law enforcement agencies.

- The Use of Wiretapping in Police Technology The report discusses Chapter 14 of the book “Police Technology” by Raymond E. Foster. Dr. Foster has written extensively on technical tools and gadgets for law enforcement.

- Police Selection Process: Metropolitan and New York Police Departments The Metropolitan Police Department and the New York Police Department selection process evaluates knowledge, abilities, skills, character and traits.

- The Savannah-Chatham Metropolitan Police Department: Most Pressing Issues This report outlines the main problematic issue with the functioning of the Savannah-Chatham Metropolitan Police Department.

- Police Reforms Implementation: The Los Angeles Police Department 83% of the LA residents vouching for the good job of the police especially because the LAPD has desisted from using serious force since 2004.

- Ending Racial Bias and Bureaucracy Within Police Police officials may engage in bureaucratic or administrative corruption for private gain, which facilitates distrust in the efforts of law enforcement.

- Profiling Procedures in the Los Angeles Police Department The law enforcers and most commonly the police, have profiling procedures that separate certain groups of people from the majority.

- Police Shooting and Issue of Discrimination The issue of discrimination and police shootings can be resolved by observing both officers and citizens – collecting information by cameras can serve as objective material.

- Police Force Diversifying Strategies The presence of women officers and officers of color may act as a complementary stimulus, as they have an approach that could be more relatable for future personnel.

- Human Sex Trafficking and Police Technology: An Issue of the Past or Present? The paper provides an introduction that describes human sex trafficking before taking a specific approach of understanding the vice in Houston, Texas.

- “How to Fix America’s Police” by Stoughton The authors of the article suggest that the US police’s current situation could be fixed in two ways: either through state intervention or through local one.

- Police Brutality Against African Americans in America The purpose of this article is to describe the different approaches to researching the problem of police brutality against African Americans.

- Inequalities and Police Brutality Against the Black This paper aims to research racial inequality and hostile police attitudes towards the black population in the United States.

- Police Brutality Against African Americans The issue being examined refers to the problem of police brutality on African Americans. The mentioned problem is a burning one and is vividly expressed in modern society.

- The Significance of Police Discretion to the Criminal Justice System This paper is an investigation into the meaning of police discretion. It highlights the benefits of police discretion to the role of the police department.

- Report for the Chief of Police The current report contains the definition and description of the Uniform Crime Report, the data-gathering strategy used for the analysis and its rationale, and crime trends.

- Management Solution Needed for the Metropolitan Police Service The dangers of getting the balance right between security, easy access, and reduction of risk are to be the main focus of the response to the tasks.

- Organizational Change in Police Departments: A Theory-Based Analysis When examining the case of implementing Compstat systems in police districts the first to consider is the positive appeals of such as system.

- Interview With Chief of Police Mr. William Evans I had a rare chance of interviewing the Chief of Police for Hinds Community College Mr. William Evans in his office on Wednesday 19 November, 2014 at 5 p.m.

- Racist Actions of the American Police Force in “The Black and the Blue” by Matthew Horace In the book “The Black and the Blue,” Matthew Horace gives testimony from behind the blue wall of secrecy and paints a society where police molest citizens.

- Police Brutality and Impunity for Police Violence The overall purpose of this paper is to explore the topic of police brutality and police impunity as it is discussed in modern studies.

- Police Brutality Against African Americans and Media Portrayal Police brutality toward the African-American population of the United States is an issue that has received nationwide publicity in recent years.

- Investigation of the Chicago Police Department This paper will analyze some of the critical issues found in the investigation of the Chicago police department by the United States Department of Justice.

- Police Violence Against African Americans in the USA The statistic shows that the violence from law enforcement officials causes thousands of deaths of black men in the USA.

- How the Police Use Facial Recognition? Some law enforcement officers, especially in Florida, do not trust the application of technique as a warrant of arrest.

- Rodney King’s Police Brutality Case: What Went Wrong Rodney’s case remains a historic example of police brutality. The interplay of several factors might have led to the acquittals of the officers in the first trial.

- “The Black Officer Who Detained George Floyd Had Pledged To Fix the Police”: A Story of Alex Kueng “The Black Officer Who Detained George Floyd Had Pledged to Fix the Police” article allows concluding that the police system cannot be reformed from within.

- Metropolitan Police Service: Identity Management Solution Within the context of Metropolitan Police Service case study, the research underlines the need for such institution to ensure production of a viable management system.

- Role of Police Agencies in Law Enforcement The police have hardly had any authority to control the most of the white color crimes. In addition, lack of expertise among the police also contributed to this problem.

- Police Corruption in California The analysis of the information proves that police corruption in California depends on the work and social environment of police officers.

- Racial Profiling of Minority Groups by the Police in the United States This research paper will address racial profiling of minority groups by the police in the US through the analysis of background, theories, and concepts.

- Chesterfield County Police Department: Hiring Process This paper will explore the applicable requirements of the Chesterfield County Police Department for the position of an entry-level law enforcement officer.

- Beyond “Police Brutality”: Racist State Violence and the University of California – Article Review The article highlights the issues with police attitudes toward the application of seemingly extreme measures to non-violent perpetrators.

- Police Misconduct and the Misuse of Force Police misconduct is a vital concern as it affects the functioning of society and might cause much harm to individuals.

- The Issue of Police Injustice in the United States In March 2020, a tragic event led to the death of a black emergency medical technician, B. Taylor. According to descriptions, police were investigating a drug case and suspected her.

- Health Safety in the Police Department It is especially important to provide a healthy working environment for workers of a police department, as they need to continue their service even at the time of a health crisis.

- American Society Police Brutality Causes and Effects Police brutality in America is visible and accompanied by racial discrimination and creates negative consequences for society because it imposes trust issues.

- Police Brutality: The Rodney King Case The case of Rodney King is a demonstration of police brutality in the United States. This paper will conduct a comprehensive analysis of the incident, explaining it in detail.

- Sexual Assault Female Victims Avoid Reporting to Police Among the most under-reported crimes in the United States, one of the leading roles is occupied by sexual assault. Sixty-five percent of female victims avoid reporting to police.

- Evaluating Budget Documents of Police Department The paper will analyze the budget which was presented by the police department indicating both the estimates and the adjusted figures.

- Professional Ethics: Police Department The science of ethics attempts to give humanity the answers to the existential question of what is moral and what is not.

- National Association of Police Organizations This paper focuses on the performance of the National Association of Police Organizations, including its purposes and contribution to the United States’ law enforcement community.

- Forensic Psychology in the Police Subspecialty Forensic psychological officers have crucial roles in the running of the police departments. This is because law enforcement chores are entitled to many challenges.

- Forensic Psychology for Police Recruitment and Screening The quest for competitive and effective police officers led to the introduction of some measures to help in the recruitment of individuals.

- Procedural Justice in Contacts with The Police Analysis The paper examines the relational model of authority that indicates the procedural justice role in the public evaluation of and support for the police.

- Testing Food Service Employees: Policy Assessment Mary Mallon, or Typhoid Mary as she was called, worked as a cook and was reputed to have caused infections of Typhoid fever in 47 people and caused the death of 3.

- Motivation & Control: The Police Supervisor’s Dilemma It is universally acknowledged that the effectiveness of the work is toughly connected with a consistent organizational structure and subordinate system.

- Police Supervisor’s Dilemma: Control and Motivation The level of control needed in a police institution is related to the capability of officers to construct an inspiring environment.

- Community Policing Assignment: A History of Police Work in the Criminal Justice System Community policing led to the introduction of a system where the police officers and members of the community get a closer relationship.

- Dismal City Police Department: “Do More With Less” The approach of community policing as well as the strategies used and its implementation vary widely depending on the requirements and the reactions of communities.

- UK Police Are Changing Their Attitude to Racial Issues The increased number of black and Asian police officers influenced positively the way suspects from minority ethnic groups were handled

- Police Brutality: Analysis of the Problem Police brutality is directed towards racial minorities and poor immigrants who cannot protect their rights in the courtroom and have no money to file a law case against officers.

- Criminal Justice Ethics: Police Corruption & Drug Sales The growth of police corruption instances involving drug sales is relatively easy to explain. The financial rewards offered by the sales of illegal drugs are enormous.

- Police or Custodial Brutality in the United States The aspect of police or custodial brutality is the subject matter of the study. This has become a serious problem in the administration of law, order, and human justice in the USA.

- US Police Challenges Today: Police Discretion Police discretion is essential to the success of an officer and the public. Discretion means judgment, and for law officers, this can be the difference between life and death.

- Police-Community Relations: Leadership Project Police-community relations are essential in curbing crime because the community has got vast knowledge in relation to the crime being practiced in the community.

- Assessing Role of Technology in Police Crime Mapping The role of technology in police operations has become pivotal because it aids our law enforcement agencies to do their tasks easier and less time-consuming.

- Police Brutality and Mental Health of African Americas The authors hypothesize that the effect of experiencing blackness has a twofold impact on the young African Americans’ mental health

- America as a Superpower and the World’s Police The international policing role and strategy of the United States during the Cold War has become even more necessary in this period of terrorism and instability.

- The Report on the Courtelaney Pass Police Department The situational report on the Courtelaney Pass police department presents a number of important issues that should be addressed by the police administration.

- Police Liability Issue and Consequences of Illegal Actions The issue of the liability of police officers and their degree of responsibility for certain actions is the topic that is discussed in the media periodically and causes a great public response.

- Addressing the Gulf Coast Police Department Understaffing Despite the best efforts of recruiters, police departments all over the US are understaffed. The present paper analyzes the reasons for GCPD’s problems and offers measures to address these issues.

- Police Attitudes and Professionalism: Interview The interviewee chosen for this assignment is a 34-year old white married male, currently working as a full-time police officer in the Miami Police Department.

- New Orleans Police Department’s Ethics and Leadership

- Local Police Response to Terrorism

- Police Work: Public Expectations and Myths

- Are African Americans More Harassed by Police?

- Undercover Police Investigations in Drug-Related Crimes

- Dallas Tragic Events: The Shooting of Police Officers by a Perpetrator

- Driving and Police Stop in Dramatic Interpretation

- Police Administrators and Their Ethical Responsibility

- Police Brutality Increasing: Support for Black Males

- Police Injustice Towards African-Americans

- Police Unions’ Development in the US

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Sexual Harassment Class Action

- Police Officer Murder, Trial and Punishment

- Myths of Policing: Police Work’ Expectation

- Police’s Brutality Towards African American Males

- Chesterfield County Police Department Structure

- Racial Profiling: Trust, Ethics, Police Legitimacy

- Police Brutality Toward African-American Males

- Police Detective Career: Information and Issues

- Criminal Profiling and Police Corruption

- Liability Issues for Police Departments

- Police Work’ Concepts and Operationalization

- Police Administration: Structures, Processes and Behavior

- Police Reform in Florida

- Police Shooting of Richard Cabot in Pittsburgh

- Police Violence and Subterfuge Cases

- Police Brutality: Reasons and Countermeasures

- The Issue of Police Brutality in Community

- The Rise of Police Brutality against African-American Males

- Are Illegal Police Quotas Still Affecting American Citizens?

- What Is the Name of American Police?

- What Are the Four Types of Police System?

- Are Women More Effective Police Officers?

- What Are Young Adults’ Perception of Police?

- What Are Some Nicknames for the Police?

- Which Country Has the Best Police System?

- Which Country Has the Largest Police Force in the World?

- When Did Police Brutality Start?

- Can the Police Reduce Crime?

- Are Police Allowed to Punch You in the UK?

- Which Countries Have Police Brutality?

- What Causes Police Corruption?

- What Is Excessive Force by Police?

- Which Indian State Has Most Powerful Police?

- What Is the Highest-Paid Job in the Police?

- How Does the Los Angeles Police Department Represent the City?

- How Can We Overcome Police Brutality?

- What Does Three Stars on a Police Uniform Mean?

- Should Police Officers Wear Cameras?

- Should the Police Have More Power?

- Do Police Officers Salute Military?

- Why Were the Police Unable to Catch Jack the Ripper?

- Which Country Has Private Police?

- How Many Police Are There in the UK?

- Are Body Cameras Fighting Police Misconduct?

- When Does Police Discretion Cross Boundaries?

- What Is the Issue of Police Brutality?

- How Does Police Brutality Violate Civil Rights?

- What Human Rights Are Being Violated by Police?

- Police use of force: trends, policies, and effects on public trust.

- How do police-worn body cameras affect officer accountability and transparency?

- Challenges and benefits of technology use in modern police.

- De-escalation techniques in police and their effects on reducing violent encounters.

- How does law enforcement address human trafficking?

- Police corruption and misconduct: causes, consequences, and prevention.

- Law enforcement challenges in investigating digital offenses.

- The effects of the militarization of police on civil liberties.

- The impact between the use of body-worn cameras and police use of force.

- The influence of implicit bias on police decision-making.

- Defunding the police: should funds be reallocated from law enforcement to social services?

- Are “stop-and-frisk” police practices constitutional?

- Facial recognition technology use by police: balancing public safety and privacy.

- Should no-knock warrants be banned?

- Do police unions promote the abuse of power?

- Is it possible to escape racial bias in predictive policing algorithms?

- The school-to-prison pipeline: do police officers belong in schools?

- Should drug testing for police officers be mandatory?

- Should the use of chokeholds and neck restraints in law enforcement be banned?

- Is anti-bias training for police officers effective in reducing violent police conduct?

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, September 9). 243 Police Research Topics + Examples. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/police-essay-topics/

"243 Police Research Topics + Examples." StudyCorgi , 9 Sept. 2021, studycorgi.com/ideas/police-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) '243 Police Research Topics + Examples'. 9 September.

1. StudyCorgi . "243 Police Research Topics + Examples." September 9, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/police-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "243 Police Research Topics + Examples." September 9, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/police-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "243 Police Research Topics + Examples." September 9, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/police-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Police were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on June 24, 2024 .

Police Topics for Research Papers

Erin schreiner.

The field of law enforcement provides a number of interesting topics worthy of exploration. If you plan to write a research paper that relates to this subject, selecting a topic that is current and engaging to you can prove a wise choice. Before you make your final topic decisions, consider some of the exciting options at your disposal and select the one about which you can find the most interesting information and that personally appeals to you most.

Explore this article

- Universal Precautions and the Police Force

- The Use of Tasers

- Communication Tools in Police Work

- The Effectiveness of Non-Motorized Officers

- Professional Development in Law Enforcement

1 Universal Precautions and the Police Force

Police work presents many dangers, one of which is the danger of contracting a disease through contact with human bodily fluids. Focus your research paper on the topic of universal precautions that officers can use to prevent disease contraction. Research the current universal precaution practices associated with police work as well as alternative options that could prove even more effective in keeping officers safe. Reference statistics in your resulting paper, using these numbers to prove the danger of disease contraction and the effectiveness of universal precautions or other prevention methods.

2 The Use of Tasers

Tasers are a relatively new tool in the police arsenal, and one that is often met with controversy. Gather information on tasers, their effectiveness and the dangers associated with taser use for your research paper. In your report, outline the benefits and weaknesses of using tasers, and discuss the precautions that police officers must take to use these tasers in a safe and effective fashion.

3 Communication Tools in Police Work

Communication is key to successful police work. Explore the tools of communication that police have at their disposal for your research paper. In your paper, discuss how each of these tools is used currently. Also, explore the potential changes to communication tools on the horizon, and explain how these changes could have an impact on the ease with which police can communicate necessary information.

4 The Effectiveness of Non-Motorized Officers

While many police officers cruise the town in squad cars, some have no motorized transportation at their disposal. Research these non-motorized officers, including foot patrolmen, bicycle-riding officers and even mounted police. Discuss situations in which these officers could be preferable to those who depend upon motorized transportation. Also, explore ways in which the effectiveness of these officers could be enhanced.

5 Professional Development in Law Enforcement

The field of law enforcement is an ever-changing one. For your research paper, explore the ways in which police officers are kept up to date on changes in the law enforcement field. Explore whether or not professional development is requisite for officers in your area, as well as how professional development is implemented. Also, discuss how this process could be improved upon to ensure that officers have the information they need to do their duties to the utmost effectiveness.

- 1 Police One: Law Enforcement Topics

About the Author

Erin Schreiner is a freelance writer and teacher who holds a bachelor's degree from Bowling Green State University. She has been actively freelancing since 2008. Schreiner previously worked for a London-based freelance firm. Her work appears on eHow, Trails.com and RedEnvelope. She currently teaches writing to middle school students in Ohio and works on her writing craft regularly.

Related Articles

Law Enforcement Research Paper Topics

What Are the Three Types of Police Patrols?

The Most Dangerous Air Force Jobs

What are Facts on the Cause of Police Brutality?

Career as a CN Rail Police Officer

Topics for a Nursing Research Paper

Science Research Paper Topic Ideas

Correctional Officer Testing

What Are the Branches of Homeland Security?

How to Make a Citizen's Arrest in Oklahoma

The Methods of Extinguishing Fires

The Use of Computers in Police Departments

Environmental and Industrial Use of Bacillus Subtilis

Business Research Paper Topics

Wildlife Speech Topics

What Was Nixon Accused Of?

How to Write a Paper on Strengths & Weaknesses

How to Find Past Information on a Resident at an Old...

Research Paper Topics About Animals

Tools or Equipment Needed for a Police Officer

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

Police1 Research Center

Find the latest information about research conducted by law enforcement organizations and academic institutions such as the National Police Foundation, the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), among other organizations focused on officer wellness, intelligence-led policing and LEO safety issues. Research recently shared includes ‘resistance-related injuries’ among officers, the experience of minority applicants during the police recruitment process, and preventing vehicle crashes and injuries among officers.

- Data shatters the small-town myth about law enforcement safety

- Police1 asked: How satisfied are police officers with their careers?

- Police1 asked: Does public perception of law enforcement impact officers’ morale?

- What officers said were the biggest challenges of 2023

- What do we really know about police suicide?

A Police Officer’s Guide to Academic Research

- © 2023

- Anne Eason 0

University of the West of England, Bristol, UK

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

- Uniquely tailors discussion of research and academic skills to a higher education police audience

- Accessibly written by experts in the field with unique professional experience

- Provides a thorough understanding of the importance of evidence-based research in operational settings

859 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

This book highlights how the practical skills of the police officer can be transferred into the realm of academic research and support them in becoming part of the evidence-based policing movement. It starts by exploring the professionalisation of the police service through higher education accreditation and the different methodologies of social research practice. Using operational comparisons and a little humour, it guides the reader through the swamp of concepts and processes, such as ethical approval, research paradigms and data gathering and analysis. It then takes them on a journey of reflection and reflexivity, challenging their own perspective on policing and working within the wider criminal justice sector and how they can make a valuable contribution to the development of policing practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Doing Research on, for and with Police in Canada and Switzerland: Practical and Methodological Insights

Police Research and Public Health

- Criminology

- Criminal Justice

- Professionalization

- Research method

- Evidence-based research

- Police force

Table of contents (7 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

- Anne Eason, Kieran McCartan

A Climate of Change

- Jack Greig-Midlane, Michael Harris

The Three R’s—Reading, ’Riting, and Research

- Iain Sirrell

Research Methodologies: Research Who?

- Anne Eason, Veronika Clegg

Ethics and Considering the Risks of Desensitisation

- Kieran McCartan

Looking in the Mirror

Conclusion—putting it all together, back matter, editors and affiliations, about the editor, bibliographic information.

Book Title : A Police Officer’s Guide to Academic Research

Editors : Anne Eason

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19286-9

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : Law and Criminology , Law and Criminology (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2023

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-031-19285-2 Published: 02 January 2023

eBook ISBN : 978-3-031-19286-9 Published: 01 January 2023

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIV, 118

Number of Illustrations : 1 b/w illustrations

Topics : Policing , Research Methodology , Crime and Society

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

123 Police Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Police officers play a crucial role in maintaining law and order in society. Their job involves protecting citizens, preventing crime, and enforcing laws. As such, police officers must possess a wide range of skills and knowledge to effectively carry out their duties. One way to help police officers develop these skills is through essay writing. Writing essays on various law enforcement topics can help officers improve their critical thinking and communication skills. To help police officers get started, here are 123 essay topic ideas and examples:

- The role of police officers in society

- The history of policing in the United States

- Community policing strategies

- The importance of diversity in law enforcement

- The impact of technology on policing

- Police discretion and its role in law enforcement

- The use of force by police officers

- Police training and education requirements

- Police accountability and transparency

- The challenges of policing in a multicultural society

- The role of police unions in law enforcement

- The ethics of undercover police work

- The impact of social media on policing

- The relationship between police officers and the media

- The history of police corruption

- The impact of police militarization on communities

- The role of police officers in responding to mental health crises

- The use of body cameras by police officers

- The role of police officers in preventing domestic violence

- The impact of drug legalization on law enforcement

- The challenges of policing in rural communities

- The impact of immigration enforcement on police-community relations

- The role of police officers in school safety

- The impact of gang violence on policing

- The challenges of policing in high-crime neighborhoods

- The impact of mass incarceration on policing

- The role of police officers in responding to mass shootings

- The impact of police militarization on civil liberties

- The challenges of policing in a post-9/11 world

- The role of police officers in responding to natural disasters

- The impact of police shootings on community trust

- The challenges of policing in a digital age

- The role of police officers in preventing human trafficking

- The impact of police body cameras on officer behavior

- The challenges of policing in a politically divided society

- The role of police officers in responding to hate crimes

- The impact of police misconduct on community relations

- The challenges of policing in a post-Ferguson world

- The future of policing in America

In conclusion, writing essays on various law enforcement topics can help police officers develop their critical thinking and communication skills. By exploring these essay topic ideas and examples, officers can gain a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities facing law enforcement today.

Want to research companies faster?

Instantly access industry insights

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Leverage powerful AI research capabilities

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2024 Pitchgrade

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Research, Science, and Policing

Expectations that policing will be evidence-based and scientific have increased significantly in recent years. [1] The logic behind this trend is undeniable – no government agency should use practices that are ineffective, and police in particular should adopt strategies, tactics, and policies that achieve the most good and cause the least harm.

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) established its Law Enforcement Advancing Data and Science (LEADS) Agencies program to help law enforcement agencies meet these growing expectations. [2] The program’s objective is to help agencies become more effective through better use of data, analysis, research, and evidence. Science does not have all the answers, however. Police leaders have to balance research and data with experience and professional judgment. [3]

Overcoming Bad Habits

Designing police practices on a solid foundation of research makes sense for many reasons, especially if one considers the alternative. If policing is done a certain way because “we’ve always done it that way,” it is likely that changing times have rendered that approach ineffective, even if it was working well at one time. If practices are based on someone’s opinion about what works, there is a good chance that selective perception, limited personal experience, and bias (conscious or unconscious) are contaminating decisions that should promote the public good. If a police agency is satisfied to do things just because others do it, the agency is probably settling for mediocrity.

Limits of Science

But research and science have their limits, some technical and others more philosophical. For example, a randomized controlled trial (RCT), called by some the gold standard of research design, maximizes internal validity, which is the confidence we have in its findings. By its very nature, though, the extent to which the findings of a RCT are generalizable to other settings (external validity) is unknown. This helps explain why arrest for misdemeanor domestic assault was the most effective of three options for reducing subsequent assaults in Minneapolis, but not in other jurisdictions. [4]

It is also important to remember that science never “proves” anything. Rather, it tests theories (formal explanations about how something works) by confirming or disconfirming null hypotheses, a fancy way of saying that all scientific knowledge is tentative. Even principles and “facts” that are relatively well-established are periodically subjected to further testing, and often debunked. Research on eyewitness identification, for example, led to revised practices and model policies for conducting in-person and photo lineups. [5] Double-blind procedures are now the industry standard and sequential presentation seems to have advantages over simultaneous, but further studies are sure to challenge whatever becomes the new status quo.

A more philosophical issue arises because policing is a function of a government that is “of the people,” not “of science.” We choose to have guilt or innocence decided by a judge or jury, not a computer algorithm. Scientists might someday develop a brain scanning technology that can accurately detect deception, but whether and how police are allowed to use that technology will be determined by public opinion, politics, and judicial interpretation of the Fourth and Fifth Amendments, not by research.

Applying Science and Research

Several considerations are essential for the proper application of science and research in police administration. One is constant appreciation for the multi-dimensional “bottom line” of policing. [6] A study may determine that one strategy is more effective than another at reducing crime, but police must also consider its effects on fear of crime, public trust, efficient use of resources, and equitable use of force and authority, not to mention key values such as legality, transparency, and accountability. Researchers have the luxury of focusing their studies on one isolated outcome, but law enforcement executives have to juggle multiple outcomes, all of which matter.

A mistake that police leaders should avoid is over-interpreting a study’s results. For example, a widely accepted conclusion from 1980s response time studies was that rapid response did not matter. More accurately, however, the studies found that an immediate response to cold crimes had little benefit, whereas quick reaction to crimes in progress was actually quite productive. [7]

Two other factors that police should weigh when considering the implications of research are context and purpose. Several studies have found foot patrol to be effective, [8] but its applicability for the Wyoming Highway Patrol or even the typical suburban department might be limited. Hot spots patrol is regarded as an evidence-based crime reduction practice, [9] but if an agency is trying to reduce identity theft or acquaintance rape, some other approach is probably needed.

Striking a Balance

Not surprisingly, law enforcement needs to follow the middle way. Building and testing a scientific knowledge base for policing is a high priority that will pay huge dividends in increased effectiveness and better public service. At the same time, all concerned need to recognize that police policies and practices are inevitably influenced by law, values, politics, and public opinion. One of the responsibilities of police leaders is drawing on wisdom and experience to make their agencies as rational and scientific as possible, given the multitude of challenges and considerations that inevitably constrain real world decision-making.

Action Items

- Stay abreast of CrimeSolutions, [10] the Campbell Collaboration, [11] the What Works Centre for Crime Reduction, [12] and other sources of evidence-based police practices.

- Carefully assess relevant studies to determine their applicability to your jurisdiction.

- Beware of confirmation bias, which is the tendency to value studies that confirm what you already believe and reject studies that challenge your beliefs.

- When necessary, conduct studies in your own agency to answer key questions about what works best in your context. [13]

- Don’t be afraid of tinkering and trial and error. Measuring performance, trying something a little different, and then measuring again is the path to continuous improvement. Most programs and practices don’t work perfectly right away, and even if they do, they will likely need tweaking over time as conditions change. [14]

- Always remember the multi-dimensional bottom line of policing – a practice that achieves one outcome but has negative effects on others is a practice ripe for improvement.

About the Authors

Gary Cordner is a former police officer, police chief, professor, and CALEA commissioner. He is also past editor of the American Journal of Police and Police Quarterly . Along with Geoff Alpert, he is a Chief Research Advisor for the LEADS Agencies program.

Geoff Alpert is a professor of criminology at the University of South Carolina. As Chief Research Advisors, he and Gary Cordner help administer the LEADS Agencies program.

[note 1] Cynthia Lum and Christopher S. Koper, Evidence-Based Policing: Translating Research Into Practice (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[note 2] See NIJ’s Law Enforcement Advancing Data and Science Scholars Program for Law Enforcement Officers .

[note 3] Jenny Fleming and Rod Rhodes, “Experience Is Not a Dirty Word,” Policy & Politics Journal Blog (2017), https://policyandpoliticsblog.com/2017/06/20/experience-is-not-a-dirty-word/.

[note 4] Christopher D. Maxwell, Joel H. Garner, and Jeffrey A. Fagan, “ The Effects of Arrest on Intimate Partner Violence: New Evidence From the Spouse Assault Replication Program ,” Research in Brief , National Institute of Justice (2001).

[note 5] See Eyewitness Identification .

[note 6] Mark H. Moore and Anthony Braga, “The ‘Bottom Line’ of Policing: What Citizens Should Value (and Measure!) in Police Performance,” Police Executive Research Forum (2003), http://www.policeforum.org/assets/docs/Free_Online_Documents/Police_Evaluation/the%20bottom%20line%20of%20policing%202003.pdf.

[note 7] William Spelman and Dale K. Brown, Calling the Police: Citizen Reporting of Serious Crime (Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum, 1981).

[note 8] See http://www.jratcliffe.net/blog/tag/foot-patrol/.

[note 9] See http://cebcp.org/evidence-based-policing/what-works-in-policing/research-evidence-review/hot-spots-policing/.

[note 10] See https://crimesolutions.ojp.gov/.

[note 11] See https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/about-campbell/coordinating-groups/crime-and-justice.html.

[note 12] See http://whatworks.college.police.uk/Pages/default.aspx.

[note 13] Ian Hesketh and Les Graham, “Theory or not Theory? That is the Question,” Australian Policing: A Journal of Professional Practice and Research 9 no.1 (2017): 10-12. http://www.cwaustral.com.au/emag/1707/aipol-volume-9-number-17/.

[note 14] Nick Tilley and Gloria Laycock, “Engineering a Safer Society,” Public Safety Leadership 4 (2016), http://www.aipm.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Research-Focus-Vol-4-Iss-2-Engineering.pdf.

Cite this Article

Read more about:, related publications.

- Open access

- Published: 12 December 2022

Unpacking the police patrol shift: observations and complications of “electronically” riding along with police

- Rylan Simpson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3214-3797 1 &

- Nick Bell 2

Crime Science volume 11 , Article number: 15 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3603 Accesses

5 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

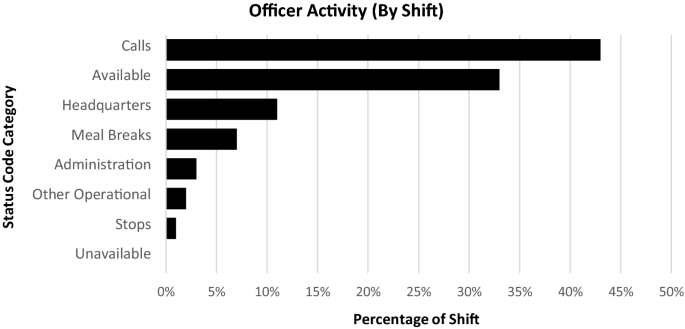

As frontline responders, patrol officers exist at the core of policing. Little remains known, however, about the specific and nuanced work of contemporary patrol officers and their shift characteristics. Drawing upon computer-aided dispatch (CAD) data for a random sample of 60 patrol shifts, we empirically analyse the activities of patrol officers working in a Canadian police agency. Our analyses reveal several interesting findings regarding the activities of patrol officers, the nature and prevalence of calls for service attended by such officers, and the temporal patterns of different patrol shifts. We discuss our results with respect to both criminological research as well as policing practice. We also highlight the complications and implications of using electronic police records to empirically study officer activity.

Introduction

As a core pillar of the criminal justice system, the police have existed at the forefront of scholarly and public attention for decades. Given the implications of their work, such interest is well-justified. From a scholarly perspective, the police are highly visible representatives of the criminal justice system and related to both social and crime control. From a practical perspective, the police impact the lives of people and the safety of communities. Not all entities within the policing institution, however, are equally implicated in these matters. Most salient among these discussions are the patrol officers: the uniformed, public-facing, and frontline personnel responsible for conducting the voluminous, street-level work of police. Yet, despite this importance, the nuance of patrol work has arguably received less empirical attention than some related topics, such as the structure of police organisations and the effects of police on crime. Considering the diverse role of police (e.g., Bittner, 1967 ; Lum et al., 2021 ; Thacher, 2022 ; Wilson, 1968 ), it is critical that research tackles the pressing questions of what patrol officers do, when, and for how long to then inform related conversations about their work.

To contribute to this aim, we draw upon computer-aided dispatch (CAD) data for a random sample of 60 patrol shifts to explore the practices of patrol officers working in a Canadian police agency. Our observations present a more mundane and nuanced depiction of policing than sometimes presented in public narratives. Handling calls for service, most of which are classified as low priority and not crime-related, comprises only a modest proportion of officers’ time on patrol. Other activities include being available to handle calls for service, working from headquarters, engaging in meal breaks, and completing administrative and other operational tasks. Given the reliance of modern police on electronic data to map and assess their practices, our use of these data to observe patrol officers exhibits wide, international relevance. We discuss such relevance in light of its practical considerations and methodological implications.

The role of the patrol officer

Patrol officers are the backbone of police. They comprise the largest proportion of all officers in many police agencies. As frontline responders, they are directly responsible for responding to calls for service, including emergencies and non-emergencies, and investigating crime. In less direct capacities, they are tasked with representing the institution through their uniformed presence, preventing crime, and engaging in the additional tasks of police, like managing fear, providing social service referrals, and confirming the welfare of people. The consequences of the work of patrol officers is significant. Nearly all public-police interactions and crime investigations start at the patrol-level, and the activities and decisions of even the most junior patrol officer exhibit the potential to shape the trajectory of an entire event and the outcomes for all affected people. The ability for patrol officers to effectively balance their responsibilities, including for reactive and proactive policing, can also impact a whole sleuth of policing outcomes, from response times to crime rates to clearance rates.

Research has long argued that much police work does not regard crime, but rather social order and peacekeeping functions (e.g., Bittner, 1967 ; Wilson, 1968 ). Consistent with this argument, recent research that explored police calls for service from across the United States found that “traffic-related problems, everyday disputes, worries of suspicious behaviors, disorders, disturbances, and general requests for help and assurance” comprised the majority of calls for which officers are dispatched (Lum et al., 2021 , p. 17; also see Simpson & Orosco, 2021 ). If patrol officers are handling these calls, then it would suggest that their work is diverse as a function of these diverse requests. But patrol work is not only about handling calls for service.

Many crime control efforts are directly implicated in the work of patrol officers. For example, hot spot policing, of which has been the subject of enormous scholarly attention (Braga et al., 2019 ), most often involves patrol officers spending time patrolling high crime areas referred to as “hot spots.” As one case in point, Koper ( 1995 ) argued that the optimal length for patrol stops is 11 to 15 min (also see Telep et al., 2014 ). Other kinds of proactive police work, including traffic-related enforcement, also typically falls upon the shoulders of patrol officers, who sometimes engage in traffic stops when not handling calls for service (Wu & Lum, 2020 ). A similar logic can be presented for proactive drug- and weapons-related enforcement as well, which frequently manifest in the form of officer-initiated stops (White & Fradella, 2016 ).

Exploring the effects of these different activities falls outside the scope of this article. However, the fact that patrol officers, whose work can be fluid and dynamic, are often tasked with engaging in these activities as well as handling calls for service implies that they must manage their time in a way that allows for competing demands to be addressed. This is especially the case when performance metrics for patrol officers include both reactive and proactive policing outputs. As generalists, patrol officers must not only exhibit some competency in most areas, but also must be available to complete many different tasks.

Measuring the work of patrol officers

Assessing the activities of patrol officers is no easy feat. Although much patrol work is public, insofar that it is frequently conducted in public spaces and in the purview of members of the public, it is not necessarily accessible, at least from an empirical perspective. To fully understand the work of patrol officers, one must observe the work of such officers: not just at a single call for service, not just for a few hours, but for an extended period of time and at different times.

Researchers tackling patrol-related questions have largely employed two approaches. First, is the ethnographic or field study approach that has placed researchers in the seat of patrol cars (e.g., Famega et al., 2005 ; Parks et al., 1999 ; Sierra-Arevalo, 2021 ; Todak & James, 2018 ). By physically riding along Footnote 1 with police, researchers are able to manually observe the work of patrol officers and its intricacies in tremendous detail. Second, is the secondary data approach that has situated researchers at the epicentre of police records (e.g., Simpson & Hipp, 2019 ; Webster, 1970 ; Wu & Lum, 2017 ). By post hoc assessing the activities of patrol officers via secondary data, researchers are able to assess patterns in public demands on police as well as the activities of officers. For example, researchers can assess the frequency of different call-types and their dispositions as well as the number of some proactive activities conducted by patrol officers.

Like all research methods, each of these approaches presents benefits and weaknesses. Whereas field research may provide a richer and more holistic assessment of the practical work of patrol officers, it can be time-intensive and costly, which can limit the number of shifts that can be reasonably observed. It can also present the risk of reactivity, whereby officers change their activity as a function of being monitored. Whereas secondary data analyses offer a greater ability to compile larger volumes of data over longer periods of time, at lesser costs, and without concerns about reactivity, secondary data generally do not offer a comparable depth of information about individual officers or their shifts. Because of data limitations, including privacy concerns if the data are publicly available, these typically quantitative examinations are frequently conducted in the abstract: researchers are often forced to study macro-level trends as opposed to more micro-level behaviours. For example, researchers may quantify the number of traffic stops conducted or types of calls for service attended during a day/week/month/year, but may not be able to disentangle how many stops were conducted and how many calls were attended by how many different individual officers and in the context of which specific shifts.

As part of the present research, we supplement existing literature by employing more of a hybrid approach to “electronically” ride-along with police for a random sample of 60 patrol shifts. Specifically, we pose the following questions: (1) How can CAD data be leveraged to measure the activities of patrol officers?; (2) What do CAD data suggest about the activities of patrol officers in terms of substance and time?; and (3) What are the challenges of using CAD data for research purposes and how might such challenges inform future researchers’ use of these data? As we outline below, the data that we draw upon and the analyses that we conduct are rich in volume and nuance. We also focus on the shift as our unit of analysis. By testing these questions at this unit using these data, we are able to provide a comprehensive snapshot of patrol officer activity as well as highlight the methodological implications of using electronic records to study patrol work. These contributions are especially important given the salience of current debates surrounding policing and how the work of patrol officers could, should, or ought to look in an era of reform.

Methodology

The present research draws upon data from a municipal police agency in Western Canada. This agency provides policing services for a population of approximately 45,000 full-time residents. It is dispatched by a consolidated call-centre that is staffed by trained, non-sworn employees who handle police-related calls for multiple cities in the region. Its urban jurisdiction covers a variety of different geographies and land-uses and has a median household income above the national average. Its crime rate falls below the national average.

The present research explores patrol officer records electronically collected via the CAD system of the police agency under study. In lieu of analysing shift logs for all officers for all possible patrol shifts, which would be neither practical nor necessary, we analyse a random sample of 60 patrol shifts associated with 28 different officers from 2019. Footnote 2 The variation in the number of shifts per officer was the result of our below described sampling strategy and the finite number of officers assigned to the patrol section.

Standard patrol shifts at this police agency are 12 h long and subdivided by time of day. The regularly scheduled “day shift” commences at 7:00am and the regularly scheduled “night shift” commences at 7:00 pm. All patrol officers work a four shift rotation, whereby they complete two day shifts followed by two night shifts before receiving four rest days. As a function of this shift pattern, each patrol officer works across different times and days of the week each week. All officers patrol alone at this agency, with one officer per vehicle (unless training).

In order to ensure that we represented all shift times, days of the week, and months of the year in our sample, we employed a stratified random sampling strategy to select our shifts. First, we randomly sampled three weekday (i.e., Monday–Thursday) and two weekend (i.e., Friday–Sunday) dates within each month. Next, we randomly selected shift times for each identified date, ensuring that we retained at least one day shift and one night shift for both weekday and weekend dates within each month. Finally, we randomly sampled an officer for each identified shift whose electronic data we then compiled. Because our unit of analysis is the shift, we did not consider officer particulars as part of our sampling process. See Table 1 for a summary of our sample of shifts.

Shift logs and status codes

Each shift log began when the patrol officer signed into the CAD system and concluded when they signed out of the CAD system. While signed into the CAD system, all documented Footnote 3 activities of the officer were electronically recorded in the form of two-digit status codes. These status codes are generated by officers via their in-car computers and/or dispatchers via their dispatch software. For example, an officer can use their in-car computer to mark themselves at their headquarters (“HQ”). An officer can also use their in-car computer to mark themselves as conducting a foot patrol (“FP”) or roadblock (“RB”). Dispatchers, namely those working in the capacity of radio-operators, can also update status codes on behalf of officers (e.g., see Simpson, 2021 ). For example, dispatchers can mark officers as available (“IS”), engaged in a traffic or person stop (“TS” or “PS,” respectively), or providing cover for another officer (“CU”), among others.

Given that status codes reflect the type of activity that a patrol officer is engaged in at any documented point in time (at least in a rudimentary form), we can use them as a measure of officer activity. Moreover, given that updates to officers’ status codes are date- and time-stamped within the CAD system, analysing them and their textual remarks allows us to post hoc estimate the amount of time that officers spent on each activity. For example, if the shift log indicates that the officer conducted a person stop (“PS”) at 1:05 pm and then initiated a meal break (“62”) at 1:09 pm, we would estimate that the officer spent four minutes on the person stop. Similarly, if the shift log indicated that the officer initiated a roadblock (“RB”) at 11:03 pm and then became available (“IS”) at 11:43 pm, we would estimate that the officer spent 40 min at the roadblock.

In their raw form, patrol officers used a total of 23 different status codes during our sample of shifts. With that being said, many status codes are similar in substance and therefore we grouped them into broader categories that effectively captured their shared theme. For example, we grouped all status codes related to calls for service into the shared category of “calls” and all status codes related to administrative tasks into the shared category of “administration.” This resulted in a final list of eight different status code categories, which we retained for our analyses (see Table 2 ).