A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Use the guidelines below to learn about the practice of close reading.

When your teachers or professors ask you to analyze a literary text, they often look for something frequently called close reading. Close reading is deep analysis of how a literary text works; it is both a reading process and something you include in a literary analysis paper, though in a refined form.

Fiction writers and poets build texts out of many central components, including subject, form, and specific word choices. Literary analysis involves examining these components, which allows us to find in small parts of the text clues to help us understand the whole. For example, if an author writes a novel in the form of a personal journal about a character’s daily life, but that journal reads like a series of lab reports, what do we learn about that character? What is the effect of picking a word like “tome” instead of “book”? In effect, you are putting the author’s choices under a microscope.

The process of close reading should produce a lot of questions. It is when you begin to answer these questions that you are ready to participate thoughtfully in class discussion or write a literary analysis paper that makes the most of your close reading work.

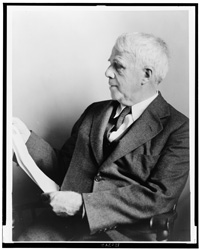

Close reading sometimes feels like over-analyzing, but don’t worry. Close reading is a process of finding as much information as you can in order to form as many questions as you can. When it is time to write your paper and formalize your close reading, you will sort through your work to figure out what is most convincing and helpful to the argument you hope to make and, conversely, what seems like a stretch. This guide imagines you are sitting down to read a text for the first time on your way to developing an argument about a text and writing a paper. To give one example of how to do this, we will read the poem “Design” by famous American poet Robert Frost and attend to four major components of literary texts: subject, form, word choice (diction), and theme.

If you want even more information about approaching poems specifically, take a look at our guide: How to Read a Poem .

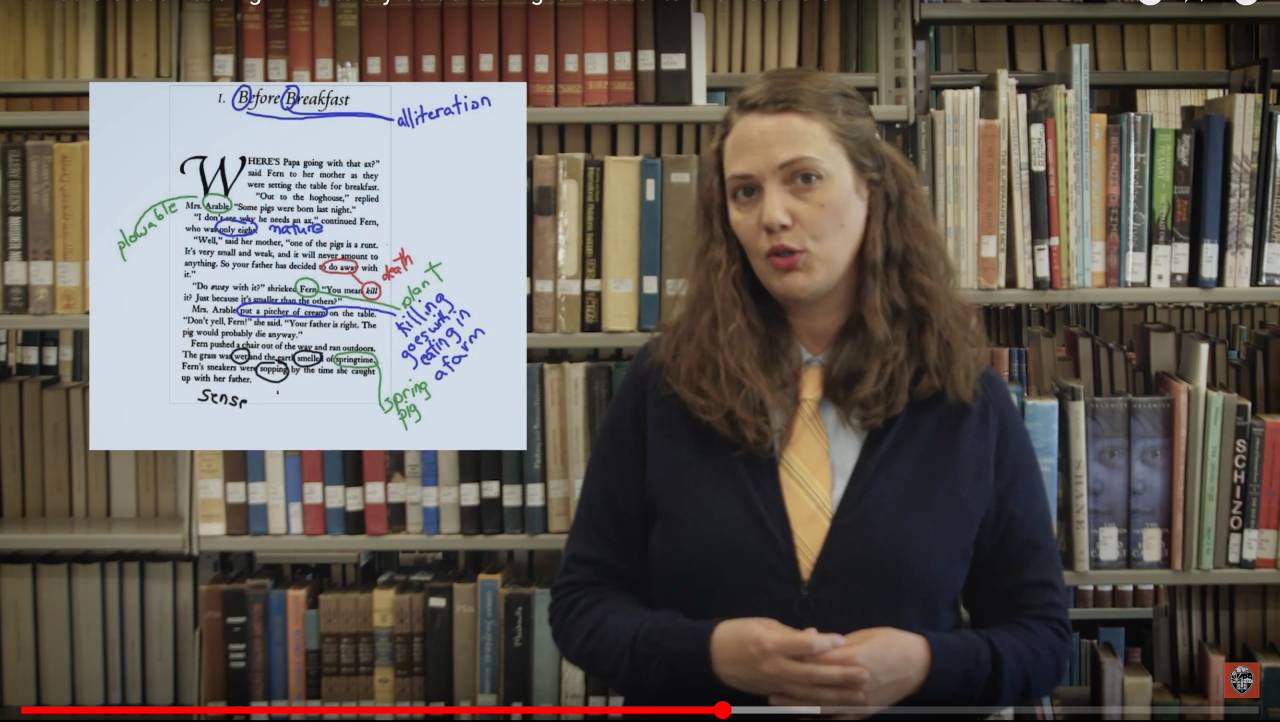

As our guide to reading poetry suggests, have a pencil out when you read a text. Make notes in the margins, underline important words, place question marks where you are confused by something. Of course, if you are reading in a library book, you should keep all your notes on a separate piece of paper. If you are not making marks directly on, in, and beside the text, be sure to note line numbers or even quote portions of the text so you have enough context to remember what you found interesting.

Design I found a dimpled spider, fat and white, On a white heal-all, holding up a moth Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth— Assorted characters of death and blight Mixed ready to begin the morning right, Like the ingredients of a witches’ broth— A snow-drop spider, a flower like a froth, And dead wings carried like a paper kite. What had that flower to do with being white, The wayside blue and innocent heal-all? What brought the kindred spider to that height, Then steered the white moth thither in the night? What but design of darkness to appall?— If design govern in a thing so small.

The subject of a literary text is simply what the text is about. What is its plot? What is its most important topic? What image does it describe? It’s easy to think of novels and stories as having plots, but sometimes it helps to think of poetry as having a kind of plot as well. When you examine the subject of a text, you want to develop some preliminary ideas about the text and make sure you understand its major concerns before you dig deeper.

Observations

In “Design,” the speaker describes a scene: a white spider holding a moth on a white flower. The flower is a heal-all, the blooms of which are usually violet-blue. This heal-all is unusual. The speaker then poses a series of questions, asking why this heal-all is white instead of blue and how the spider and moth found this particular flower. How did this situation arise?

The speaker’s questions seem simple, but they are actually fairly nuanced. We can use them as a guide for our own as we go forward with our close reading.

- Furthering the speaker’s simple “how did this happen,” we might ask, is the scene in this poem a manufactured situation?

- The white moth and white spider each use the atypical white flower as camouflage in search of sanctuary and supper respectively. Did these flora and fauna come together for a purpose?

- Does the speaker have a stance about whether there is a purpose behind the scene? If so, what is it?

- How will other elements of the text relate to the unpleasantness and uncertainty in our first look at the poem’s subject?

After thinking about local questions, we have to zoom out. Ultimately, what is this text about?

Form is how a text is put together. When you look at a text, observe how the author has arranged it. If it is a novel, is it written in the first person? How is the novel divided? If it is a short story, why did the author choose to write short-form fiction instead of a novel or novella? Examining the form of a text can help you develop a starting set of questions in your reading, which then may guide further questions stemming from even closer attention to the specific words the author chooses. A little background research on form and what different forms can mean makes it easier to figure out why and how the author’s choices are important.

Most poems follow rules or principles of form; even free verse poems are marked by the author’s choices in line breaks, rhythm, and rhyme—even if none of these exists, which is a notable choice in itself. Here’s an example of thinking through these elements in “Design.”

In “Design,” Frost chooses an Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet form: fourteen lines in iambic pentameter consisting of an octave (a stanza of eight lines) and a sestet (a stanza of six lines). We will focus on rhyme scheme and stanza structure rather than meter for the purposes of this guide. A typical Italian sonnet has a specific rhyme scheme for the octave:

a b b a a b b a

There’s more variation in the sestet rhymes, but one of the more common schemes is

c d e c d e

Conventionally, the octave introduces a problem or question which the sestet then resolves. The point at which the sonnet goes from the problem/question to the resolution is called the volta, or turn. (Note that we are speaking only in generalities here; there is a great deal of variation.)

Frost uses the usual octave scheme with “-ite”/”-ight” (a) and “oth” (b) sounds: “white,” “moth,” “cloth,” “blight,” “right,” “broth,” “froth,” “kite.” However, his sestet follows an unusual scheme with “-ite”/”-ight” and “all” sounds:

a c a a c c

Now, we have a few questions with which we can start:

- Why use an Italian sonnet?

- Why use an unusual scheme in the sestet?

- What problem/question and resolution (if any) does Frost offer?

- What is the volta in this poem?

- In other words, what is the point?

Italian sonnets have a long tradition; many careful readers recognize the form and know what to expect from his octave, volta, and sestet. Frost seems to do something fairly standard in the octave in presenting a situation; however, the turn Frost makes is not to resolution, but to questions and uncertainty. A white spider sitting on a white flower has killed a white moth.

- How did these elements come together?

- Was the moth’s death random or by design?

- Is one worse than the other?

We can guess right away that Frost’s disruption of the usual purpose of the sestet has something to do with his disruption of its rhyme scheme. Looking even more closely at the text will help us refine our observations and guesses.

Word Choice, or Diction

Looking at the word choice of a text helps us “dig in” ever more deeply. If you are reading something longer, are there certain words that come up again and again? Are there words that stand out? While you are going through this process, it is best for you to assume that every word is important—again, you can decide whether something is really important later.

Even when you read prose, our guide for reading poetry offers good advice: read with a pencil and make notes. Mark the words that stand out, and perhaps write the questions you have in the margins or on a separate piece of paper. If you have ideas that may possibly answer your questions, write those down, too.

Let’s take a look at the first line of “Design”:

I found a dimpled spider, fat and white

The poem starts with something unpleasant: a spider. Then, as we look more closely at the adjectives describing the spider, we may see connotations of something that sounds unhealthy or unnatural. When we imagine spiders, we do not generally picture them dimpled and white; it is an uncommon and decidedly creepy image. There is dissonance between the spider and its descriptors, i.e., what is wrong with this picture? Already we have a question: what is going on with this spider?

We should look for additional clues further on in the text. The next two lines develop the image of the unusual, unpleasant-sounding spider:

On a white heal-all, holding up a moth Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth—

Now we have a white flower (a heal-all, which usually has a violet-blue flower) and a white moth in addition to our white spider. Heal-alls have medicinal properties, as their name suggests, but this one seems to have a genetic mutation—perhaps like the spider? Does the mutation that changes the heal-all’s color also change its beneficial properties—could it be poisonous rather than curative? A white moth doesn’t seem remarkable, but it is “Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth,” or like manmade fabric that is artificially “rigid” rather than smooth and flowing like we imagine satin to be. We might think for a moment of a shroud or the lining of a coffin, but even that is awry, for neither should be stiff with death.

The first three lines of the poem’s octave introduce unpleasant natural images “of death and blight” (as the speaker puts it in line four). The flower and moth disrupt expectations: the heal-all is white instead of “blue and innocent,” and the moth is reduced to “rigid satin cloth” or “dead wings carried like a paper kite.” We might expect a spider to be unpleasant and deadly; the poem’s spider also has an unusual and unhealthy appearance.

- The focus on whiteness in these lines has more to do with death than purity—can we understand that whiteness as being corpse-like rather than virtuous?

Well before the volta, Frost makes a “turn” away from nature as a retreat and haven; instead, he unearths its inherent dangers, making nature menacing. From three lines alone, we have a number of questions:

- Will whiteness play a role in the rest of the poem?

- How does “design”—an arrangement of these circumstances—fit with a scene of death?

- What other juxtapositions might we encounter?

These disruptions and dissonances recollect Frost’s alteration to the standard Italian sonnet form: finding the ways and places in which form and word choice go together will help us begin to unravel some larger concepts the poem itself addresses.

Put simply, themes are major ideas in a text. Many texts, especially longer forms like novels and plays, have multiple themes. That’s good news when you are close reading because it means there are many different ways you can think through the questions you develop.

So far in our reading of “Design,” our questions revolve around disruption: disruption of form, disruption of expectations in the description of certain images. Discovering a concept or idea that links multiple questions or observations you have made is the beginning of a discovery of theme.

What is happening with disruption in “Design”? What point is Frost making? Observations about other elements in the text help you address the idea of disruption in more depth. Here is where we look back at the work we have already done: What is the text about? What is notable about the form, and how does it support or undermine what the words say? Does the specific language of the text highlight, or redirect, certain ideas?

In this example, we are looking to determine what kind(s) of disruption the poem contains or describes. Rather than “disruption,” we want to see what kind of disruption, or whether indeed Frost uses disruptions in form and language to communicate something opposite: design.

Sample Analysis

After you make notes, formulate questions, and set tentative hypotheses, you must analyze the subject of your close reading. Literary analysis is another process of reading (and writing!) that allows you to make a claim about the text. It is also the point at which you turn a critical eye to your earlier questions and observations to find the most compelling points, discarding the ones that are a “stretch.” By “stretch,” we mean that we must discard points that are fascinating but have no clear connection to the text as a whole. (We recommend a separate document for recording the brilliant ideas that don’t quite fit this time around.)

Here follows an excerpt from a brief analysis of “Design” based on the close reading above. This example focuses on some lines in great detail in order to unpack the meaning and significance of the poem’s language. By commenting on the different elements of close reading we have discussed, it takes the results of our close reading to offer one particular way into the text. (In case you were thinking about using this sample as your own, be warned: it has no thesis and it is easily discoverable on the web. Plus it doesn’t have a title.)

Frost’s speaker brews unlikely associations in the first stanza of the poem. The “Assorted characters of death and blight / Mixed ready to begin the morning right” make of the grotesque scene an equally grotesque mockery of a breakfast cereal (4–5). These lines are almost singsong in meter and it is easy to imagine them set to a radio jingle. A pun on “right”/”rite” slides the “characters of death and blight” into their expected concoction: a “witches’ broth” (6). These juxtapositions—a healthy breakfast that is also a potion for dark magic—are borne out when our “fat and white” spider becomes “a snow-drop”—an early spring flower associated with renewal—and the moth as “dead wings carried like a paper kite” (1, 7, 8). Like the mutant heal-all that hosts the moth’s death, the spider becomes a deadly flower; the harmless moth becomes a child’s toy, but as “dead wings,” more like a puppet made of a skull. The volta offers no resolution for our unsettled expectations. Having observed the scene and detailed its elements in all their unpleasantness, the speaker turns to questions rather than answers. How did “The wayside blue and innocent heal-all” end up white and bleached like a bone (10)? How did its “kindred spider” find the white flower, which was its perfect hiding place (11)? Was the moth, then, also searching for camouflage, only to meet its end? Using another question as a disguise, the speaker offers a hypothesis: “What but design of darkness to appall?” (13). This question sounds rhetorical, as though the only reason for such an unlikely combination of flora and fauna is some “design of darkness.” Some force, the speaker suggests, assembled the white spider, flower, and moth to snuff out the moth’s life. Such a design appalls, or horrifies. We might also consider the speaker asking what other force but dark design could use something as simple as appalling in its other sense (making pale or white) to effect death. However, the poem does not close with a question, but with a statement. The speaker’s “If design govern in a thing so small” establishes a condition for the octave’s questions after the fact (14). There is no point in considering the dark design that brought together “assorted characters of death and blight” if such an event is too minor, too physically small to be the work of some force unknown. Ending on an “if” clause has the effect of rendering the poem still more uncertain in its conclusions: not only are we faced with unanswered questions, we are now not even sure those questions are valid in the first place. Behind the speaker and the disturbing scene, we have Frost and his defiance of our expectations for a Petrarchan sonnet. Like whatever designer may have altered the flower and attracted the spider to kill the moth, the poet built his poem “wrong” with a purpose in mind. Design surely governs in a poem, however small; does Frost also have a dark design? Can we compare a scene in nature to a carefully constructed sonnet?

A Note on Organization

Your goal in a paper about literature is to communicate your best and most interesting ideas to your reader. Depending on the type of paper you have been assigned, your ideas may need to be organized in service of a thesis to which everything should link back. It is best to ask your instructor about the expectations for your paper.

Knowing how to organize these papers can be tricky, in part because there is no single right answer—only more and less effective answers. You may decide to organize your paper thematically, or by tackling each idea sequentially; you may choose to order your ideas by their importance to your argument or to the poem. If you are comparing and contrasting two texts, you might work thematically or by addressing first one text and then the other. One way to approach a text may be to start with the beginning of the novel, story, play, or poem, and work your way toward its end. For example, here is the rough structure of the example above: The author of the sample decided to use the poem itself as an organizational guide, at least for this part of the analysis.

- A paragraph about the octave.

- A paragraph about the volta.

- A paragraph about the penultimate line (13).

- A paragraph about the final line (14).

- A paragraph addressing form that suggests a transition to the next section of the paper.

You will have to decide for yourself the best way to communicate your ideas to your reader. Is it easier to follow your points when you write about each part of the text in detail before moving on? Or is your work clearer when you work through each big idea—the significance of whiteness, the effect of an altered sonnet form, and so on—sequentially?

We suggest you write your paper however is easiest for you then move things around during revision if you need to.

Further Reading

If you really want to master the practice of reading and writing about literature, we recommend Sylvan Barnet and William E. Cain’s wonderful book, A Short Guide to Writing about Literature . Barnet and Cain offer not only definitions and descriptions of processes, but examples of explications and analyses, as well as checklists for you, the author of the paper. The Short Guide is certainly not the only available reference for writing about literature, but it is an excellent guide and reminder for new writers and veterans alike.

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

How to Do a Close Reading

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Close Reading Fundamentals

How to choose a passage to close-read, how to approach a close reading, how to annotate a passage, how to improve your close reading, how to practice close reading, how to incorporate close readings into an essay, how to teach close reading, additional resources for advanced students.

Close reading engages with the formal properties of a text—its literary devices, language, structure, and style. Popularized in the mid-twentieth century, this way of reading allows you to interpret a text without outside information such as historical context, author biography, philosophy, or political ideology. It also requires you to put aside your affective (that is, personal and emotional) response to the text, focusing instead on objective study. Why close-read a text? Doing so will increase your understanding of how a piece of writing works, as well as what it means. Perhaps most importantly, close reading can help you develop and support an essay argument. In this guide, you'll learn more about what close reading entails and find strategies for producing precise, creative close readings. We've included a section with resources for teachers, along with a final section with further reading for advanced students.

You might compare close reading to wringing out a wet towel, in which you twist the material repeatedly until you have extracted as much liquid as possible. When you close-read, you'll return to a short passage several times in order to note as many details about its form and content as possible. Use the links below to learn more about close reading's place in literary history and in the classroom.

"Close Reading" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia's relatively short introduction to close reading contains sections on background, examples, and how to teach close reading. You can also click the links on this page to learn more about the literary critics who pioneered the method.

"Close Reading: A Brief Note" (Literariness.org)

This article provides a condensed discussion of what close reading is, how it works, and how it is different from other ways of reading a literary text.

"What Close Reading Actually Means" ( TeachThought )

In this article by an Ed.D., you'll learn what close reading "really means" in the classroom today—a meaning that has shifted significantly from its original place in 20th century literary criticism.

"Close Reading" (Univ. of Washington)

This hand-out from a college writing course defines close reading, suggests why we close-read, and offers tips for close reading successfully, including focusing on language, audience, and scope.

"Glossary Entry on New Criticism" (Poetry Foundation)

If you'd like to read a short introduction to the school of thought that gave rise to close reading, this is the place to go. Poetry Foundation's entry on New Criticism is concise and accessible.

"New Criticism" (Washington State Univ.)

This webpage from a college writing course offers another brief explanation of close reading in relation to New Criticism. It provides some key questions to help you think like a New Critic.

When choosing a passage to close-read, you'll want to look for relatively short bits of text that are rich in detail. The resources below offer more tips and tricks for selecting passages, along with links to pre-selected passages you can print for use at home or in the classroom.

"How to Choose the Perfect Passage for Close Reading" ( We Are Teachers )

This post from a former special education teacher describes six characteristics you might look for when selecting a close reading passage from a novel: beginnings, pivotal plot points, character changes, high-density passages, "Q&A" passages, and "aesthetic" passages.

"Close Reading Passages" (Reading Sage)

Reading Sage provides links to close reading passages you can use as is; alternatively, you could also use them as models for selecting your own passages. The page is divided into sections geared toward elementary, middle school, and early high school students.

"Close Reading" (Univ. of Guelph)

The University of Guelph's guide to close reading contains a short section on how to "Select a Passage." The author suggests that you choose a brief passage.

"Close Reading Advice" (Prezi)

This Prezi was created by an AP English teacher. The opening section on passage selection suggests choosing "thick paragraphs" filled with "figurative language and rich details or description."

Now that you know how to select a passage to analyze, you'll need to familiarize yourself with the textual qualities you should look for when reading. Whether you're approaching a poem, a novel, or a magazine article, details on the level of language (literary devices) and form (formal features) convey meaning. Understanding how a text communicates will help you understand what it is communicating. The links in this section will familiarize you with the tools you need to start a close reading.

Literary Devices

"Literary Devices and Terms" (LitCharts)

LitCharts' dedicated page covers 130+ literary devices. Also known as "rhetorical devices," "figures of speech," or "elements of style," these linguistic constructions are the building blocks of literature. Some of the most common include simile , metaphor , alliteration , and onomatopoeia ; browse the links on LitCharts to learn about many more.

"Rhetorical Device" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia's page on rhetorical devices defines the term in relation to the ancient art of "rhetoric" or persuasive speaking. At the bottom of the page, you'll find links to several online handbooks and lists of rhetorical devices.

"15 Must Know Rhetorical Terms for AP English Literature" ( Albert )

The Albert blog offers this list of 15 rhetorical devices that high school English students should know how to define and spot in a literary text; though geared toward the Advanced Placement exam, its tips are widely applicable.

"The 55 AP Language and Composition Terms You Must Know" (PrepScholar)

This blog post lists 55 terms high school students should learn how to recognize and define for the Advanced Placement exam in English Literature.

Formal Features

In LitCharts' bank of literary devices and terms, you'll also find resources to describe a text's structure and overall character. Some of the most important of these are rhyme , meter , and tone ; browse the page to find more.

"Rhythm" ( Encyclopedia Britannica )

This encyclopedia entry on rhythm and meter offers an in-depth definition of the two most fundamental aspects of poetry.

"How to Analyze Syntax for AP English Literature" ( Albert)

The Albert blog will help you understand what "syntax" is, making a case for why you should pay attention to sentence structure when analyzing a literary text.

"Grammar Basics: Sentence Parts and Sentence Structures" ( ThoughtCo )

This article provides a meticulous overview of the components of a sentence. It's useful if you need to review your parts of speech or if you need to be able to identify things like prepositional phrases.

"Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice" (Wheaton College)

Wheaton College's Writing Center offers this clear, concise discussion of several important formal features. Although it's designed to help essay writers, it will also help you understand and spot these stylistic features in others' work.

Now that you know what rhetorical devices, formal features, and other details to look for, you're ready to find them in a text. For this purpose, it is crucial to annotate (write notes) as you read and re-read. Each time you return to the text, you'll likely notice something new; these observations will form the basis of your close reading. The resources in this section offer some concrete strategies for annotating literary texts.

"How to Annotate a Text" (LitCharts)

Begin by consulting our How to Annotate a Text guide. This collection of links and resources is helpful for short passages (that is, those for close reading) as well as longer works, like whole novels or poems.

"Annotation Guide" (Covington Catholic High School)

This hand-out from a high school teacher will help you understand why we annotate, and how to annotate a text successfully. You might choose to incorporate some of the interpretive notes and symbols suggested here.

"Annotating Literature" (New Canaan Public Schools)

This one-page, introductory resource provides a list of 10 items you should look for when reading a text, including attitude and theme.

"Purposeful Annotation" (Dave Stuart Jr.)

This article from a high school teacher's blog describes the author's top close reading strategy: purposeful annotation. In fact, this teacher more or less equates close reading with annotation.

Looking for ways to improve your close reading? The articles, guides, and videos in this section will expose you to various methods of close reading, as well as practice exercises. No two people read exactly the same way. Whatever your level of expertise, it can be useful to broaden your skill set by testing the techniques suggested by the resources below.

"How to Do a Close Reading" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, part of Harvard's comprehensive "Strategies for Essay Writing Guide," describes three steps to a successful close reading. You will want to return to this resource when incorporating your close reading into an essay.

"A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis" (Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center)

Working through this guide from another college writing center will help you move through the process of close reading a text. You'll find a sample analysis of Robert Frost's "Design" at the end.

"How to Do a Close Reading of a Text" (YouTube)

This four-minute video from the "Literacy and Math Ideas" channel offers a number of helpful tips for reading a text closely in accordance with Common Core standards.

"Poetry: Close Reading" (Purdue OWL)

Short, dense poems are a natural fit for the close reading approach. This page from the Purdue Online Writing Lab takes you step-by-step through an analysis of Shakespeare's Sonnet 116.

"Steps for Close Reading or Explication de Texte" ( The Literary Link )

This page, which mentions close reading's close relationship to the French formalist method of "explication de texte," shares "12 Steps to Literary Awareness."

You can practice your close reading skills by reading, re-reading and annotating any brief passage of text. The resources below will get you started by offering pre-selected passages and questions to guide your reading. You'll find links to resources that are designed for students of all levels, from elementary school through college.

"Notes on Close Reading" (MIT Open Courseware)

This resource describes steps you can work through when close reading, providing a passage from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein for you to test your skills.

"Close Reading Practice Worksheets" (Gillian Duff's English Resources)

Here, you'll find 10 close reading-centered worksheets you can download and print. The "higher-close-reading-formula" link at the bottom of the page provides a chart with even more steps and strategies for close reading.

"Close Reading Activities" (Education World)

The four activities described on this page are best suited to elementary and middle school students. Under each heading is a link to handouts or detailed descriptions of the activity.

"Close Reading Practice Passages: High School" (Varsity Tutors)

This webpage from Varsity Tutors contains over a dozen links to close reading passages and exercises, including several resources that focus on close-reading satire.

"Benjamin Franklin's Satire of Witch Hunting" (America in Class)

This page contains both a "teacher's guide" and "student version" to interpreting Benjamin Franklin's satire of a witch trial. The thirteen close reading questions on the right side of the page will help you analyze the text thoroughly.

Whether you're writing a research paper or an essay, close reading can help you build an argument. Careful analysis of your primary texts allows you to draw out meanings you want to emphasize, thereby supporting your central claim. The resources in this section introduce you to strategies suited to various common writing assignments.

"How to Write a Research Paper" (LitCharts)

The resources in this guide will help you learn to formulate a thesis, organize evidence, write an outline, and draft a research paper, one of the two most common assignments in which you might incorporate close reading.

"How to Write an Essay" (LitCharts)

In this guide, you'll learn how to plan, draft, and revise an essay, whether for the classroom or as a take-home assignment. Close reading goes hand in hand with the brainstorming and drafting processes for essay writing.

"Guide to the Close Reading Essay" (Univ. of Warwick)

This guide was designed for undergraduates, and assumes prior knowledge of formal features and rhetorical devices one might find in a poem. High schoolers will find it useful after addressing the "elements of a close reading" section above.

"Beginning the Academic Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Harvard's guide discusses the broader category of the "academic essay." Here, the author assumes that your essay's close readings will be accompanied by context and evidence from secondary sources.

A Short Guide to Writing About Literature (Amazon)

Sylvan Barnet and William E. Cain emphasize that writing is a process. In their book, you'll find definitions of important literary terms, examples of successful explications of literary texts, and checklists for essay writers.

Due in part to the Common Core's emphasis on close reading skills, resources for teaching students how to close-read abound. Here, you'll find a wealth of information on how and why we teach students to close-read texts. The first section includes links to activities, exercises, and complete lesson plans. The second section offers background material on the method, along with strategies for implementing close reading in the classroom.

Lesson Plans and Activities

"Four Lessons for Introducing the Fundamental Steps of Close Reading" (Corwin)

Here, Corwin has made the second chapter of Nancy Akhavan's The Nonfiction Now Lesson Bank, Grades 4 – 8 available online. You'll find four sample lessons to use in the elementary or middle school classroom

"Sonic Patterns: Exploring Poetic Techniques Through Close Reading" ( ReadWriteThink )

This lesson plan for high school students includes material for five 50-minute sessions on sonic patterns (including consonance, assonance, and alliteration). The literary text at hand is Robert Hayden's "Those Winter Sundays."

"Close Reading of a Short Text: Complete Lesson" (McGraw Hill via YouTube)

This eight-minute video describes a complete lesson in which a teacher models close reading of a short text and offers guiding questions.

"Close Reading Model Lessons" (Achieve the Core)

These three model lessons on close reading will help you determine what makes a text "appropriately complex" for the grade level you teach.

Close Reading Bundle (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This top-rated bundle of close reading resources was designed for the middle school classroom. It contains over 150 pages of worksheets, complete lesson plans, and literacy center ideas.

"10 Intriguing Photos to Teach Close Reading and Visual Thinking Skills" ( The New York Times )

The New York Times' s Learning Network has gathered 10 photos from the "What's Going on in This Picture" series that teachers can use to help students develop analytical and visual thinking skills.

"The Close Reading Essay" (Brandeis Univ.)

Brandeis University's writing program offers this detailed set of guidelines and goals you might use when assigning a close reading essay.

Close Reading Resources (Varsity Tutors)

Varsity Tutors has compiled a list of over twenty links to lesson plans, strategies, and activities for teaching elementary, middle school, and high school students to close read.

Background Material and Teaching Strategies

Falling in Love with Close Reading (Amazon)

Christopher Lehman and Kate Roberts aim to show how close reading can be "rigorous, meaningful, and joyous." It offers a three-step "close reading ritual" and engaging lesson plans.

Notice & Note: Strategies for Close Reading (Amazon)

Kylene Beers (a former Senior Reading Researcher at Yale) and Robert E. Probst (a Professor Emeritus of English Education) introduce six "signposts" readers can use to detect significant moments in a work of literature.

"How to Do a Close Reading" (YouTube)

TeachLikeThis offers this four-minute video on teaching students to close-read by looking at a text's language, narrative, syntax, and context.

"Strategy Guide: Close Reading of a Literary Text" ( ReadWriteThink )

This guide for middle school and high school teachers will help you choose texts that are appropriately complex for the grade level you teach, and offers strategies for planning engaging lessons.

"Close Reading Steps for Success" (Appletastic Learning)

Shelly Rees, a teacher with over 20 years of experience, introduces six helpful steps you can use to help your students engage with challenging reading passages. The article is geared toward elementary and middle school teachers.

"4 Steps to Boost Students' Close Reading Skills" ( Amplify )

Doug Fisher, a professor of educational leadership, suggests using these four steps to help students at any grade level learn how to close read.

Like most tools of literary analysis, close reading has a complex history. It's not necessary to understand the theoretical underpinnings of close reading in order to use this tool. For advanced high school students and college students who ask "why close-read," though, the resources below will serve as useful starting points for discussion.

"Discipline and Parse: The Politics of Close Reading" ( Los Angeles Review of Books )

This book review by a well-known English professor at Columbia provides an engaging, anecdotal introduction to close reading's place in literary history. Robbins points to some of the method's shortcomings, but also elegantly defends it.

"Intentional Fallacy" ( Encyclopedia Britannica )

The literary critics who developed close reading cautioned against judging a text based on the author's intention. This encyclopedia entry offers an expanded definition of this way of reading, called the "intentional fallacy."

"Seven Types of Ambiguity" (Wikipedia)

This Wikipedia article will introduce you to William Empson's Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), one of the foundational texts of New Criticism, the school of thought that theorized close reading.

"What is Distant Reading" ( The New York Times)

This article makes it clear that "close reading" isn't the only way to analyze literary texts. It offers a brief introduction to the "distant reading" method of computational criticism pioneered by Franco Moretti in recent years.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1999 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 42,251 quotes across 1999 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

BibGuru Blog

Be more productive in school

- Citation Styles

How to do a close reading essay [Updated 2024]

Close reading refers to the process of interpreting a literary work’s meaning by analyzing both its form and content. In this post, we provide you with strategies for close reading that you can apply to your next assignment or analysis.

What is a close reading?

Close reading involves paying attention to a literary work’s language, style, and overall meaning. It includes looking for patterns, repetitions, oddities, and other significant features of a text. Your goal should be to reveal subtleties and complexities beyond an initial reading.

The primary difference between simply reading a work and doing a close reading is that, in the latter, you approach the text as a kind of detective.

When you’re doing a close reading, a literary work becomes a puzzle. And, as a reader, your job is to pull all the pieces together—both what the text says and how it says it.

How do you do a close reading?

Typically, a close reading focuses on a small passage or section of a literary work. Although you should always consider how the selection you’re analyzing fits into the work as a whole, it’s generally not necessary to include lengthy summaries or overviews in a close reading.

There are several aspects of the text to consider in a close reading:

- Literal Content: Even though a close reading should go beyond an analysis of a text’s literal content, every reading should start there. You need to have a firm grasp of the foundational content of a passage before you can analyze it closely. Use the common journalistic questions (Who? What? When? Where? Why?) to establish the basics like plot, character, and setting.

- Tone: What is the tone of the passage you’re examining? How does the tone influence the entire passage? Is it serious, comic, ironic, or something else?

- Characterization: What do you learn about specific characters from the passage? Who is the narrator or speaker? Watch out for language that reveals the motives and feelings of particular characters.

- Structure: What kind of structure does the work utilize? If it’s a poem, is it written in free or blank verse? If you’re working with a novel, does the structure deviate from certain conventions, like straightforward plot or realism? Does the form contribute to the overall meaning?

- Figurative Language: Examine the passage carefully for similes, metaphors, and other types of figurative language. Are there repetitions of certain figures or patterns of opposition? Do certain words or phrases stand in for larger issues?

- Diction: Diction means word choice. You should look up any words that you don’t know in a dictionary and pay attention to the meanings and etymology of words. Never assume that you know a word’s meaning at first glance. Why might the author choose certain words over others?

- Style and Sound: Pay attention to the work’s style. Does the text utilize parallelism? Are there any instances of alliteration or other types of poetic sound? How do these stylistic features contribute to the passage’s overall meaning?

- Context: Consider how the passage you’re reading fits into the work as a whole. Also, does the text refer to historical or cultural information from the world outside of the text? Does the text reference other literary works?

Once you’ve considered the above features of the passage, reflect on its relationship to the work’s larger themes, ideas, and actions. In the end, a close reading allows you to expand your understanding of a text.

Close reading example

Let’s take a look at how this technique works by examining two stanzas from Lorine Niedecker’s poem, “ I rose from marsh mud ”:

I rose from marsh mud, algae, equisetum, willows, sweet green, noisy birds and frogs to see her wed in the rich rich silence of the church, the little white slave-girl in her diamond fronds.

First, we need to consider the stanzas’ literal content. In this case, the poem is about attending a wedding. Next, we should take note of the poem’s form: four-line stanzas, written in free verse.

From there, we need to look more closely at individual words and phrases. For instance, the first stanza discusses how the speaker “rose from marsh mud” and then lists items like “algae, equisetum, willows” and “sweet green,” all of which are plants. Could the speaker have been gardening before attending the wedding?

Now, juxtapose the first stanza with the second: the speaker leaves the natural world of mud and greenness for the “rich/ rich silence of the church.” Note the repetition of the word, “rich,” and how the poem goes on to describe the “little white slave-girl/ in her diamond fronds,” the necessarily “rich” jewelry that the bride wears at her wedding.

Niedecker’s description of the diamond jewelry as “fronds” refers back to the natural world of plants that the speaker left behind. Note also the similarities in sound between the “frogs” of the first stanza and the “fronds” of the second.

We might conclude from a comparison of the two stanzas that, while the “marsh mud” might be full of “noisy/ birds and frogs,” it’s a far better place to be than the “rich/rich silence of the church.”

Ultimately, even a short close reading of Niedecker’s poem reveals layers of meaning that enhance our understanding of the work’s overall message.

How to write a close reading essay

Getting started.

Before you can write your close reading essay, you need to read the text that you plan to examine at least twice (but often more than that). Follow the above guidelines to break down your close reading into multiple parts.

Once you’ve read the text closely and made notes, you can then create a short outline for your essay. Determine how you want to approach to structure of your essay and keep in mind any specific requirements that your instructor may have for the assignment.

Structure and organization

Some close reading essays will simply analyze the text’s form and content without making a specific argument about the text. Other times, your instructor might want you to use a close reading to support an argument. In these cases, you’ll need to include a thesis statement in the introduction to your close reading essay.

You’ll organize your essay using the standard essay format. This includes an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Most of your close reading will be in the body paragraphs.

Formatting and length

The formatting of your close reading essay will depend on what type of citation style that your assignment requires. If you’re writing a close reading for a composition or literature class , you’ll most likely use MLA or Chicago style.

The length of your essay will vary depending on your assignment guidelines and the length and complexity of the text that you’re analyzing. If your close reading is part of a longer paper, then it may only take up a few paragraphs.

Citations and bibliography

Since you will be quoting directly from the text in your close reading essay, you will need to have in-text, parenthetical citations for each quote. You will also need to include a full bibliographic reference for the text you’re analyzing in a bibliography or works cited page.

To save time, use a credible citation generator like BibGuru to create your in-text and bibliographic citations. You can also use our citation guides on MLA and Chicago to determine what you need to include in your citations.

Frequently Asked Questions about how to do a close reading

A successful close reading pays attention to both the form and content of a literary work. This includes: literal content, tone, characterization, structure, figurative language, diction, sound, style, and context.

A close reading essay is a paper that analyzes a text or a portion of a text. It considers both the form and content of the text. The specific format of your close reading essay will depend on your assignment guidelines.

Skimming and close reading are opposite approaches. Skimming involves scanning a text superficially in order to glean the most important points, while close reading means analyzing the details of a text’s language, style, and overall form.

You might begin a close reading by providing some context about the passage’s significance to the work as a whole. You could also briefly summarize the literal content of the section that you’re examining.

The length of your essay will vary depending on your assignment guidelines and the length and complexity of the text that you’re analyzing.

Make your life easier with our productivity and writing resources.

For students and teachers.

- Utility Menu

ef0807c43085bac34d8a275e3ff004ed

Classicswrites, a guide to research and writing in the field of classics.

- Harvard Classics

- HarvardWrites

Close Reading

Close reading as analysis.

Close reading is the technique of carefully analyzing a passage’s language, content, structure, and patterns in order to understand what a passage means, what it suggests, and how it connects to the larger work. A close reading delves into what a passage means beyond a superficial level, then links what that passage suggests outward to its broader context. One goal of close reading is to help readers to see facets of the text that they may not have noticed before. To this end, close reading entails “reading out of” a text rather than “reading into” it. Let the text lead, and listen to it.

The goal of close reading is to notice, describe, and interpret details of the text that are already there, rather than to impose your own point of view. As a general rule of thumb, every claim you make should be directly supported by evidence in the text. As the name suggests this technique is best applied to a specific passage or passages rather than a longer piece, almost like a case study.

Use close reading to learn:

- what the passage says

- what the passage implies

- how the passage connects to its context

Why Close Reading?

Close reading is a fundamental skill for the analysis of any sort of text or discourse, whether it is literary, political, or commercial. It enables you to analyze how a text functions, and it helps you to understand a text’s explicit and implicit goals. The structure, vocabulary, language, imagery, and metaphors used in a text are all crucial to the way it achieves its purpose, and they are therefore all targets for close reading. Practicing close reading will train you to be an intelligent and critical reader of all kinds of writing, from political speeches to television advertisements and from popular novels to classic works of literature.

Wondering how to do a close reading? Click on our Where to Begin section to find out more!

- Where to Begin and Strategies

- Tips and Tricks

English and Related Literature

University | A to Z | Departments

- Department of English and Related Literature

- Writing at York

- Writing Resources

Close reading

- Resources for schools

- Writing Curriculum

- Writer in Residence

- Writing Community

- Getting help with your writing

- Active Silence

- Writing Team

- Equality and diversity

- Current staff and students

Elaine Showalter describes close reading as:

...slow reading, a deliberate attempt to detach ourselves from the magical power of story-telling and pay attention to language, imagery, allusion, intertextuality, syntax and form.

It is, in her words, ‘a form of defamiliarisation we use in order to break through our habitual and casual reading practices’ (Teaching Literature, 98).

As readers, we are accustomed to reading for plot, or allowing the joy of the reading experience to take over and carry us along, without stopping to ask how and why a particular passage, sentence, or word achieves its effects.

Close reading, then, is about pausing, and looking at the precise techniques, dynamics, and content of the text. It’s not reading between the lines, but reading further and further into the lines and seeing the multiple meanings a turn of phrase, a description, or a word can unlock.

It is possible to close read an extended passage, but for essays it is often a good technique to do the close reading first and then to use very short extracts or even single words to demonstrate your insights. So instead of doing a close reading of twenty lines from A Midsummer Night’s Dream *in* your essay, you would do it independently, and then cite and explain three key phrases, relating them clearly to your developing argument.

Close reading is also sometimes known as Practical Criticism, rooted in the techniques espoused by the Cambridge critic I. A. Richards.

He felt it was essential that students put aside their preconceptions and learn to appreciate the liveliness and multiplicity of language.

With that in mind, he gave students poems without any information about who wrote them or why they were written.

In the hands of subsequent critics, like William Empson, the technique became a way to offer virtuoso accounts of particular poems and literary works, with an emphasis on ambiguity and the multiplication of possible meanings.

In essence, close reading means taking a step back from the larger narrative and examining the constituent parts of a text.

Think of close reading as something that you do with a pencil and book in your hand. Mark up the pages; fill the margins.

“Annotate to appreciate; annotate to understand… It builds reading confidence; it helps us understand how literature is made—because it puts us there among the phrases.” Sometimes the Best Way to Read is to Mark up the Book - on the revelatory power of annotations

And then transcribe the poem, the passage, the quotation.

Accurate transcription of quotations is, for some, the first and last rule of close reading. If your passage isn’t transcribed meticulously, down to the last comma and (with poetry) spacing on the page, you can’t read it closely.

Careful transcription will also help you get inside a passage: you’ll get a feel for its rhythms, its twists and turns, its breathing. Look at the words.

Don’t take your eyes off the words. Work from the actual text in front of you, not from a sort of mental paraphrase of what the text says. As you do so, remember to think carefully about sound, not only when reading poetry but also when analysing prose.

Read the passage aloud, paying close attention to the rhythms of sentences. You might be surprised by what you hear: the eye can often glide over aspects of a text that the ear is keen to pick up. Remember, too, that it’s important not only to detect certain features but also to consider their effects. If you need to pause to catch your breath in the middle of a sentence, ask yourself why. How are form and content working together?

Close, not closed readings

Close reading has been criticised for being divorced from context and for pulling away from the historical and political engagements of the literary text.

Partly for that reason, it is important to think about the purpose behind your close reading – we are looking for close readings, not closed readings. Essentially, the close reading is the starting point for your essay, letting you find what is interesting, intricate, and unexpected about a literary text.

In the essay itself, you need to stitch that revelation about the complexities and ambiguities of particular terms, phrases and passages into a larger argument or context – don’t simply list everything you have found; craft it into an argument, and be prepared to downplay or leave out some of the elements you have spotted if they don’t relate to the larger picture.

For this reason, you might want to follow the “Rule of 2”. Your analysis of your quotation should be twice as long as the quotation itself. It's a nice reminder that we always need to go back and explain the textual evidence that's being cited.

Each piece of textual evidence needs and deserves detailed analysis if it's being used to support the argument's claims. It also helps to remind us to vary the lengths of quoted textual evidence so that an essay doesn't end up with only very brief quotations or long block quotations, but includes a mixture of different lengths that will best suit the claim being developed at any given point in the argument.

Some questions you may like to ask

- Who is speaking? Who is being spoken to? What is the reader assumed to know/not know? (University essays aren't written for an interested aunt or friend on a different course, but for an audience familiar with the themes and readings under discussion. Students are writing for an audience of engaged and interested peers. This means that the writer can assume that their reader knows the text and doesn't need extensive plot summary in the introduction or start of the essay. This frees up space for analysis and the laying out of each section's claims. It also helps to develop an authoritative voice: you are an expert speaking to other experts.)

- What is the point of the details included in the passage (eg if mundane things are mentioned, why is that; if there are elements of description that don’t seem to contribute to the plot what do they do instead)?

- What generic clues are here (what kinds of writing are hinted at)?

- Are there words or phrases which are ambiguous (could mean more than one thing)? If so, are we directed to privilege one reading over the other or do we keep both in play? Does one meaning open up an alternative story/history/narrative? What are the connotations of the words that are chosen? Do any of them open up new or different contexts?

- Are there patterns which emerge in the language (the repetition of words or of certain kinds of words? Repeated phrases? Rhymes or half-rhymes? Metrical patterns?). What effects do they create?

- Is there any movement in the passage you are reading? Are there any shapes or dominant metaphors?

- What kind of rhythm does the passage have? What is its cadence?

- Is there anything that troubles you about the passage or that you’re not sure you fully understand?

- Have you been to the dictionary (remember the full Oxford English Dictionary is available online through the library)?

For more specific advice, you might want to read our Ways of Reading series

- Ways of Reading a Novel

- Ways of Reading a Poem

- Ways of Reading a Film

- Ways of Reading a Play

- Ways of Reading a Translation

Extra Reading (and remember you can close read secondary as well as primary texts)

Thomas A. Foster, How to Read Literature Like a Professor: a Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines (Harper, 2003). Elizabeth A. Howe, Close Reading: an Introduction to Literature (Prentice Hall, 2009). George Lakoff and Mark Turner, More than Cool Reason: a Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor (Chicago, 1989). Frank Lentricchia and Andrew DuBois (eds), Close Reading: the Reader (Duke, 2002). Christopher Ricks, The Force of Poetry (Oxford, 1995). Elaine Showalter, Teaching Literature (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2002).

For more on Practical Criticism, with some useful online exercises, try the Virtual Classroom on Practical Criticism

There’s a neat example by Patricia Kain at Harvard College’s Writing Center .

Trev Broughton , Alexandra Kingston-Reese , Chloe Wigston-Smith , Hannah Roche , Helen Smith , and Matthew Townend April 2018

This article is available to download for free as a PDF for use as a personal learning tool or for use in the classroom as a teaching resource.

Department of English and Related Literature University of York , York , YO10 5DD , UK Tel: work +44 (0) 1904 323366 | [email protected]

Legal statements | Privacy | Cookies | Accessibility © University of York | Modify | Direct Edit

Write a Close Reading

Choose a passage, step 1: read the passage, step 2: analyze the passage, step 3: develop a descriptive thesis, step 4: construct an argument about the passage., step 5: develop an outline based on your thesis.

- Tips for Close Readings

- Close Reading in English Literature

- Close Reading in Philosophy

Ask Us: Chat, Email, Visit or Call

More Help: Writing

- Book Writing Appointments Get help on your writing assignments.

If you have not been assigned a passage or poem, then you must select a text and a specific passage.

Limit your selection to a paragraph or two at the most. In some cases, a sentence or two (or a few lines, if you are dealing with a poem) will be sufficient. Keep in mind that literature (and especially poetry) can be very dense. You will be surprised at how much you can glean from a short section – and how easily you can be overwhelmed by selecting a section that is too long.

Look for unusual or repetitive images or themes and passages with rich imagery or language.

Also pay particular attention to passages that relate to central characters or definitions of keywords; you may decide to focus on one section and how it helps you understand a character, relationship, issue, or idea.

Take notes as you read. Mark anything that seems relevant or interesting to you – even if you are unsure why a particular section of the text stands out.

Ask yourself: How is language and/or argument being used? Take notes about your observations of the passage, even if these observations seem simplistic or self-evident. Also pay attention to how language use changes over the course of your passage. For example, if the same word appears at the beginning and end, does it mean different things in both places? Does the author's tone or attitude change?

After you have read the entire text, you can return to these sections to look for repeated patterns, themes, or words. Often, a close reading will focus on one example of a theme or pattern to study the significance of this theme or pattern more in depth.

Begin by writing answers to some of the following questions, focusing on the kinds of rhetorical and literary devices you see in the passage.

- What words are being used here?

- Are any words repeated in this passage?

- What adjectives are used? What nouns do they describe? How do they alter your understanding of these nouns?

- Are any two (or more) words used in this passage connected in some way?

If any words are unfamiliar, look them up. If you are analyzing an older text, keep in mind that words may mean different things at different points in history—so be sure to look up any words that may be familiar but used in an unfamiliar way. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) will provide you with definitions as well as histories of word use.

Whether you are looking at an historical or contemporary text, remember that words can be used in different ways. Ask yourself: Are any words being used in unusual ways? Are any words referring to something more than what is simply stated? Are any two (or more) words in the passage connected in some way?

Narrative Voice

- Who is speaking in this passage?

- What narrative perspective is being used in this passage?

- What does the narrative voice tell you?

- What characters does it give you access to?

- Is the speaker being straightforward, factual, open?

- Is the speaker being direct or ambiguous with their message?

- Does the voice carry any emotion? Or is it detached from its subject?

- Do you hear irony (what is said is different from what is meant)? If so, where?

Rhetorical and Literary devices:

- Do you notice any figurative language, such as metaphors and similes?

- Do you observe any imagery?

- Is the sound of the language and sentences important (e.g., rhyme, repetition, choppy or long sentences)?

- What is the effect of these devices and techniques? (e.g., do they add emphasis or connect key ideas?)

Once you have finished looking at the language in detail, you can use your observations to construct a descriptive thesis. For example, you could argue that a passage is using short, simple sentences, or that it is using irony or a combination of these things. Your descriptive thesis should attempt to summarize the observations you have made about HOW language is being used in your passage.

Remember, this is not your final thesis statement. It's just your first step to arriving at an analytical thesis.

Now that you have some idea of HOW language is being used in your passage, you need to connect this to the larger themes of the text. In other words, you now need to address WHY language is being used in the way (or ways) you have observed.

This step is essential to a successful close reading. It is not enough to simply make observations about language use – you must take these observations and use them to construct an argument about the passage.

Transform your descriptive thesis into an argument by asking yourself WHY language is used in this way:

- What kinds of words are used (intellectual, elaborate, plain, or vulgar)? Why are words being used in this way?

- Why are sentences long or short? Why might the author be using complicated or simple sentences? What might this type of sentence structure suggest about what the passage is trying to convey?

- Who is the narrator? What is the narrative voice providing these particular descriptions? Why are we given access to the consciousness of these particular characters? Why not others?

- What images do you see in the passage? What might they represent? Is there a common theme?

- Why might the tone of the passage be emotional (or detached)?

- To what purpose might the text employ irony?

- What effect/impact is the author trying to create?

After you have established your thesis, you’ll need to write an essay that supports this argument with examples and analysis.

For example, you might argue that in the novel Jane Eyre , Jane’s friend Helen Burns uses language and imagery to describe God in a very different way from characters who represent religious authority. To prove your argument, you must organize your essay to show examples of how Helen Burns describes God and interpret her description. You must also analyze how her description differs from the status quo in the novel and tell readers why this difference matters to our understanding of the novel.

- << Previous: Start Here

- Next: Tips for Close Readings >>

- Last Updated: Oct 2, 2023 1:29 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uoguelph.ca/CloseReading

Suggest an edit to this guide

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

Literary Research in Harvard Libraries

- Distant Reading, Close Reading

- Get Organized

- Find Background

- Where to Search

- Search Vocabulary

- Obscure/Recent Topics

- Literary Journalism Search (under construction!)

- Find Primary or Archival Material

- Literary Theory

- Foreign Language Literatures

Distant Reading

About distant reading.

"Distant reading" has a specific meaning (coined by Franco Moretti), but can also generally refer to the use of computational methods to analyze literary texts. To learn more, start with Debates in the Digital Humanities , or explore this HOLLIS search for scholarly guides to the Digital Humanities and this MLA search for "distant reading" and related terms .

Ngram Viewers: Chart word usage over time

Beware: ngram counts are only as relevant or interesting as the corpus of texts they're measuring. Is the spike or drop you're observing attributable to a change in how language is used, or just material circumstances that make something likely to be included or excluded from your corpus? Think about the long-term durability of various kinds of paper, library collection policies, wartime effects on publishing, etc.

- Google Ngram: choose a sample of the Google Books corpus, including the "Google million." Search up to 5 consecutive words. Visit About Google Ngram for details and advanced features.

- HathiTrust Bookworm : samples the HathiTrust Digital Library. Unigrams (single words) only. More precise options for specifying type of publication. Select a plot point to see a snapshot of texts with "hits."

- Mediacloud : lots of options for visualizing topics in the news. Requires creating a free account.

Databases and Datasets

- HarvardKey-restricted : the library licenses access to many kinds of databases that provide data , searchable full-text corpora , and other kinds of tools.

- Free to access : the web abounds in open-access portals that encourage you to explore texts on a macro scale. Some big ones include the Digital Public Library of America , HathiTrust and its HathiTrust Research Center , Europeana , and the Internet Archive . There are many, many more.

- Specialized datasets , such as the ECCO corpus, may be available by request

- For details and specific recommendations , ask me!

- For additional leads and ideas , see library research guides that mention data

Build Your Own Project: Campus Resources

- Digital Scholarship Group

- Lamont Media Lab

- Harvard Map Collection

- Institute for Quantitative Social Science

Close Reading

About close reading.

Close reading is an activity that keeps you focused on and within a text—appraising individual words, shapes of thought, rhetorical devices, patterns of description and characterization, and so forth, in order to understand the text's artistic achievement. For more on the history and practice, see the JHU Guide's article on Practical Criticism or this HOLLIS search for "close reading" and literary criticism .

Trace Word Meanings over Time

- The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) : widely accepted as the most complete record of the English language ever assembled. Each entry includes a pronunciation key and etymology (in Old or Middle English, for example), identifies a word's earliest known use, and lists the word's changing meanings (including those now obsolete). Quotations from literary texts and other historical records illustrate different usages over time. The OED has a fascinating history of its own .

Trace Occurrences of a Word across Texts

- Concordances : These are published, alphabetized lists of individual words used in a single text (e.g.Thoreau's Walden ) or larger oeuvre (e.g. Ezra Pound's Cantos or Milton's English prose ). In HOLLIS, add "concordances" to the author's name, e.g. concordances AND "Keats, John" . Many concordances are now published online instead: examples include the Victorian Literary Studies Archive Hyper-Concordance , the Open Source Shakespeare Concordance , and the Online Concordance to Wallace Stevens' Poetry .

- Searchable full-text collections : When a concordance isn't available, there may be digital editions of the literary text(s) you're studying. For English and American authors, try LION (Literature Online) : it contains a library of 350,000 texts from the 8th century through the 20th. For more, see our guide to Finding Full Text Books Online .

- Variorum editions : Some texts exist in multiple versions. The differences between these versions, from the removal or addition of whole passages to subtle changes in punctuation, can make enormous differences in interpretation. A variorum edition collates textual variants and attempts to account for them, in some cases, by including the critical conversations they have engendered. A HOLLIS search for an author's name plus "variorum" or "variants" ( "Shakespeare, William" AND (variorum OR variants) will bring up variorum editions as well as literary criticism that focuses specifically on textual variants.

Understand Literary and Rhetorical Terms

These special terms provide literary scholars with a shorthand for describing the formal properties of language, but they can also give you new lenses with which to view texts. The word "chiasmus" is shorter than "repetition of ideas in reverse order"; the concept of chiasmus might make you more alert to the order in which ideas are repeated within a sentence or a paragraph.

- The Reference Works collection in Literature Online is an excellent selection of searchable guides specific to literary studies. Pro tip : you can use the general search box and then filter your results to "Reference."

- Silva Rhetoricae : An award-winning website, maintained at Brigham Young University, that provides overviews of rhetorical practice, definitions of rhetorical figures, and very helpful examples of each.

- Individual guides and dictionaries: a HOLLIS search for dictionaries of poetics and literary terminology is a good way to see what's out there. For a helpful selection, start at call number RR 3005.31 in the Loker Reading Room.

- << Previous: Foreign Language Literatures

Except where otherwise noted, this work is subject to a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which allows anyone to share and adapt our material as long as proper attribution is given. For details and exceptions, see the Harvard Library Copyright Policy ©2021 Presidents and Fellows of Harvard College.

Writing Studio

How to do a close reading of fiction, close reading questions answered.

In an effort to make our handouts more accessible, we have begun converting our PDF handouts to web pages. Download this page as a PDF: See page 2 of How to Do a Close Reading of Fiction Return to Writing Studio Handouts

What is a close reading?

A close reading is a systematic and attentive approach to understanding a text. Often called “unpacking” a text, a close reading helps separate the working parts of a text, explain them, and put them back together into a new understanding of the whole. When writing a critical analysis of literature, implementing this skill enables us to make more precise arguments about the things we read.

What is the point of a close reading?

A close reading helps us to attain our own understanding and interpretation of the text, taking us beyond plot summary.

In paying close attention to what we are reading, we can make an argument about how a small fragment of the text illuminates something about the whole.

What should I avoid in a close reading?

The first mistake we often make in close reading is imposing our own presuppositions on the text. Some of these presuppositions might include the following: assuming that we know more than we actually know about the historical context of the novel (i.e., a certain text by an American author was written before 1800, therefore it is an extended metaphor for the formation of a new nation); automatically assuming that the “point” of the text is to say something about “today’s society.”

Sometimes the greatest obstacle to understanding is the assumption that our own worldview can adequately explain what we are reading. Instead, to develop your own interpretation, first immerse yourself in the world of the text and try to follow its unique logic.

How do I begin a close reading?

Unpacking an entire novel would take a lot of time, probably more time than most of us have to spend on a short analytical paper. However, if we choose a few key scenes, episodes, or conversations within that novel for our close reading, we then have a more manageable portion of text at hand and can make a more sophisticated argument about it.

You might consider choosing: a turning point in the conflict, an illuminating moment of characterization, a subtle shift in the tone within the novel that carries implications for what comes after it, or interesting language or syntax.

How do I proceed after I select a passage? What am I suppose to do with it?

Good question! It is advisable to read the passage twice, maybe even three times, to ensure you do not miss any details that could help you form an argument. While you are reading, look for interesting stylistic patterns, repetitions of themes, or references to other parts of the text. If none of those things are in play, you can still look at the language the author uses and consider how it might compare to or depart from other parts of the novel. (Hint: Check in other parts of the work).

If you are dealing with a descriptive passage of a particular setting, for example, you might think about how the physical space of the story affects the movement of the characters. Are they trapped in a small space that keeps them constantly colliding and conflicting with one another? Are they in the middle of the desert where the openness of the landscape leaves them feeling isolated and alone? Asking these kinds of questions while you read will help you to not only decipher what the text is saying but also to understand it from several different angles. Then, once you are through this stage, you might decide to incorporate some of your own outside knowledge or insights if you feel they are applicable.

Last revised: 07/2009 | Adapted for web delivery: 04/2021

In order to access certain content on this page, you may need to download Adobe Acrobat Reader or an equivalent PDF viewer software.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Close Reading a Text and Avoiding Pitfalls

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.