Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

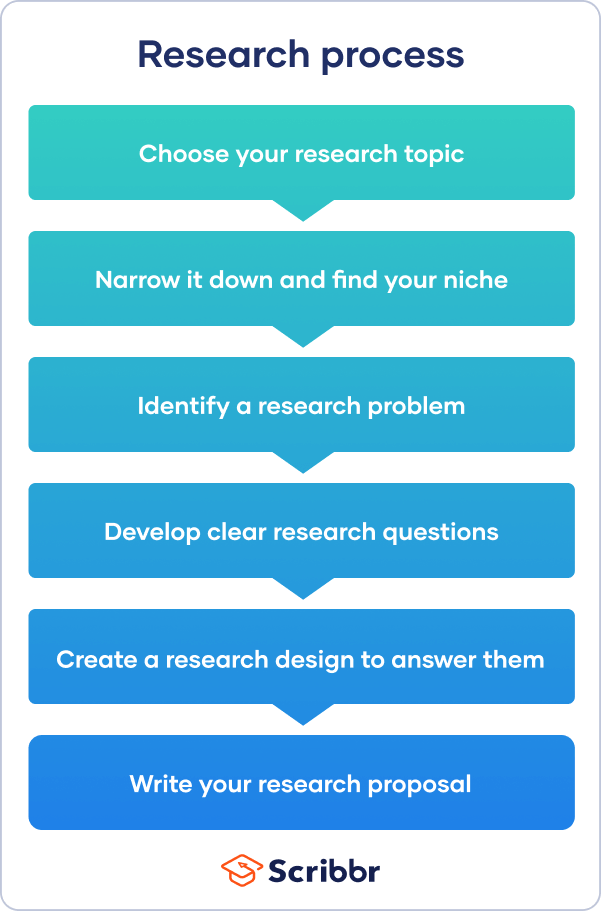

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

| Qualitative approach | Quantitative approach |

|---|---|

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Experimental | |

| Quasi-experimental | |

| Correlational | |

| Descriptive |

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | |

| Phenomenology |

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

| Probability sampling | Non-probability sampling |

|---|---|

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

| Questionnaires | Interviews |

|---|---|

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

| Quantitative observation | |

|---|---|

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

| Field | Examples of data collection methods |

|---|---|

| Media & communication | Collecting a sample of texts (e.g., speeches, articles, or social media posts) for data on cultural norms and narratives |

| Psychology | Using technologies like neuroimaging, eye-tracking, or computer-based tasks to collect data on things like attention, emotional response, or reaction time |

| Education | Using tests or assignments to collect data on knowledge and skills |

| Physical sciences | Using scientific instruments to collect data on things like weight, blood pressure, or chemical composition |

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

| Reliability | Validity |

|---|---|

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

| Approach | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Thematic analysis | |

| Discourse analysis |

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 26 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Introduction

The Creating a Research Space [C.A.R.S.] Model was developed by John Swales based upon his analysis of journal articles representing a variety of discipline-based writing practices. His model attempts to explain and describe the organizational pattern of writing the introduction to scholarly research studies. Following the C.A.R.S. Model can be useful approach because it can help you to: 1) begin the writing process [getting started is often the most difficult task]; 2) understand the way in which an introduction sets the stage for the rest of your paper; and, 3) assess how the introduction fits within the larger scope of your study. The model assumes that writers follow a general organizational pattern in response to two types of challenges [“competitions”] relating to establishing a presence within a particular domain of research: 1) the competition to create a rhetorical space and, 2) the competition to attract readers into that space. The model proposes three actions [Swales calls them “moves”], accompanied by specific steps, that reflect the development of an effective introduction for a research paper. These “moves” and steps can be used as a template for writing the introduction to your own social sciences research papers.

"Introductions." The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Coffin, Caroline and Rupert Wegerif. “How to Write a Standard Research Article.” Inspiring Academic Practice at the University of Exeter; Kayfetz, Janet. "Academic Writing Workshop." University of California, Santa Barbara, Fall 2009; Pennington, Ken. "The Introduction Section: Creating a Research Space CARS Model." Language Centre, Helsinki University of Technology, 2005; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks. 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004.

Creating a Research Space Move 1: Establishing a Territory [the situation] This is generally accomplished in two ways: by demonstrating that a general area of research is important, critical, interesting, problematic, relevant, or otherwise worthy of investigation and by introducing and reviewing key sources of prior research in that area to show where gaps exist or where prior research has been inadequate in addressing the research problem. The steps taken to achieve this would be:

- Step 1 -- Claiming importance of, and/or [writing action = describing the research problem and providing evidence to support why the topic is important to study]

- Step 2 -- Making topic generalizations, and/or [writing action = providing statements about the current state of knowledge, consensus, practice or description of phenomena]

- Step 3 -- Reviewing items of previous research [writing action = synthesize prior research that further supports the need to study the research problem; this is not a literature review but more a reflection of key studies that have touched upon but perhaps not fully addressed the topic]

Move 2: Establishing a Niche [the problem] This action refers to making a clear and cogent argument that your particular piece of research is important and possesses value. This can be done by indicating a specific gap in previous research, by challenging a broadly accepted assumption, by raising a question, a hypothesis, or need, or by extending previous knowledge in some way. The steps taken to achieve this would be:

- Step 1a -- Counter-claiming, or [writing action = introduce an opposing viewpoint or perspective or identify a gap in prior research that you believe has weakened or undermined the prevailing argument]

- Step 1b -- Indicating a gap, or [writing action = develop the research problem around a gap or understudied area of the literature]

- Step 1c -- Question-raising, or [writing action = similar to gap identification, this involves presenting key questions about the consequences of gaps in prior research that will be addressed by your study. For example, one could state, “Despite prior observations of voter behavior in local elections in urban Detroit, it remains unclear why do some single mothers choose to avoid....”]

- Step 1d -- Continuing a tradition [writing action = extend prior research to expand upon or clarify a research problem. This is often signaled with logical connecting terminology, such as, “hence,” “therefore,” “consequently,” “thus” or language that indicates a need. For example, one could state, “Consequently, these factors need to examined in more detail....” or “Evidence suggests an interesting correlation, therefore, it is desirable to survey different respondents....”]

Move 3: Occupying the Niche [the solution] The final "move" is to announce the means by which your study will contribute new knowledge or new understanding in contrast to prior research on the topic. This is also where you describe the remaining organizational structure of the paper. The steps taken to achieve this would be:

- Step 1a -- Outlining purposes, or [writing action = answering the “So What?” question. Explain in clear language the objectives of your study]

- Step 1b -- Announcing present research [writing action = describe the purpose of your study in terms of what the research is going to do or accomplish. In the social sciences, the “So What?” question still needs to addressed]

- Step 2 -- Announcing principle findings [writing action = present a brief, general summary of key findings written, such as, “The findings indicate a need for...,” or “The research suggests four approaches to....”]

- Step 3 -- Indicating article structure [writing action = state how the remainder of your paper is organized]

"Introductions." The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Atai, Mahmood Reza. “Exploring Subdisciplinary Variations and Generic Structure of Applied Linguistics Research Article Introductions Using CARS Model.” The Journal of Applied Linguistics 2 (Fall 2009): 26-51; Chanel, Dana. "Research Article Introductions in Cultural Studies: A Genre Analysis Explorationn of Rhetorical Structure." The Journal of Teaching English for Specific and Academic Purposes 2 (2014): 1-20; Coffin, Caroline and Rupert Wegerif. “How to Write a Standard Research Article.” Inspiring Academic Practice at the University of Exeter; Kayfetz, Janet. "Academic Writing Workshop." University of California, Santa Barbara, Fall 2009; Pennington, Ken. "The Introduction Section: Creating a Research Space CARS Model." Language Centre, Helsinki University of Technology, 2005; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004; Swales, John M. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990; Chapter 5: Beginning Work. In Writing for Peer Reviewed Journals: Strategies for Getting Published . Pat Thomson and Barbara Kamler. (New York: Routledge, 2013), pp. 93-96.

Writing Tip

Swales showed that establishing a research niche [move 2] is often signaled by specific terminology that expresses a contrasting viewpoint, a critical evaluation of gaps in the literature, or a perceived weakness in prior research. The purpose of using these words is to draw a clear distinction between perceived deficiencies in previous studies and the research you are presenting that is intended to help resolve these deficiencies. Below is a table of common words used by authors.

|

|

|

|

|

| albeit although but howbeit however nevertheless notwithstanding unfortunately whereas yet | few handful less little no none not | challenge deter disregard exclude fail hinder ignore lack limit misinterpret neglect obviate omit overlook prevent question restrict | difficult dubious elusive inadequate incomplete inconclusive inefficacious ineffective inefficient questionable scarce uncertain unclear unconvincing unproductive unreliable unsatisfactory |

NOTE: You may prefer not to adopt a negative stance in your writing when placing it within the context of prior research. In such cases, an alternative approach is to utilize a neutral, contrastive statement that expresses a new perspective without giving the appearance of trying to diminish the validity of other people's research. Examples of how to take a more neutral contrasting stance can be achieved in the following ways, with A representing the findings of prior research, B representing your research problem, and X representing one or more variables that have been investigated.

- Prior research has focused primarily on A , rather than on B ...

- Prior research into A can be beneficial but to rectify X , it is important to examine B ...

- These studies have placed an emphasis in the areas of A as opposed to describing B ...

- While prior studies have examined A , it may be preferable to contemplate the impact of B ...

- After consideration of A , it is important to also distinguish B ...

- The study of A has been thorough, but changing circumstances related to X support a need for examining [or revisiting] B ...

- Although research has been devoted to A , less attention has been paid to B ...

- Earlier research offers insights into the need for A , though consideration of B would be particularly helpful to...

In each of these example statements, what follows the ellipsis is the justification for designing a study that approaches the problem in the way that contrasts with prior research but which does not devalue its ongoing contributions to current knowledge and understanding.

Dretske, Fred I. “Contrastive Statements.” The Philosophical Review 81 (October 1972): 411-437; Kayfetz, Janet. "Academic Writing Workshop." University of California, Santa Barbara, Fall 2009; Pennington, Ken. "The Introduction Section: Creating a Research Space CARS Model." Language Centre, Helsinki University of Technology, 2005; Swales, John M. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990

- << Previous: 4. The Introduction

- Next: Background Information >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2024 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- How it works

How to Write a Research Design – Guide with Examples

Published by Alaxendra Bets at August 14th, 2021 , Revised On June 24, 2024

A research design is a structure that combines different components of research. It involves the use of different data collection and data analysis techniques logically to answer the research questions .

It would be best to make some decisions about addressing the research questions adequately before starting the research process, which is achieved with the help of the research design.

Below are the key aspects of the decision-making process:

- Data type required for research

- Research resources

- Participants required for research

- Hypothesis based upon research question(s)

- Data analysis methodologies

- Variables (Independent, dependent, and confounding)

- The location and timescale for conducting the data

- The time period required for research

The research design provides the strategy of investigation for your project. Furthermore, it defines the parameters and criteria to compile the data to evaluate results and conclude.

Your project’s validity depends on the data collection and interpretation techniques. A strong research design reflects a strong dissertation , scientific paper, or research proposal .

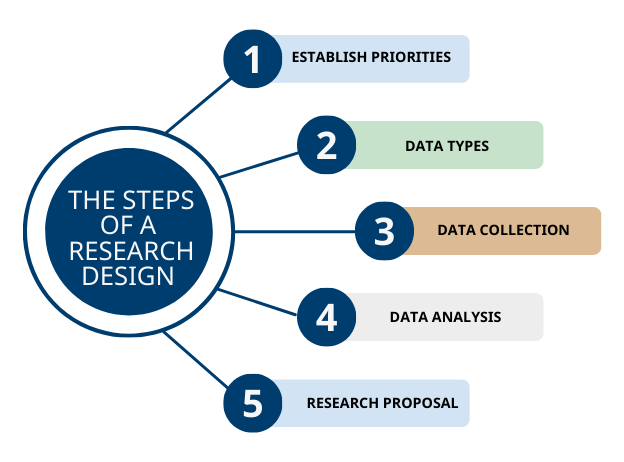

Step 1: Establish Priorities for Research Design

Before conducting any research study, you must address an important question: “how to create a research design.”

The research design depends on the researcher’s priorities and choices because every research has different priorities. For a complex research study involving multiple methods, you may choose to have more than one research design.

Multimethodology or multimethod research includes using more than one data collection method or research in a research study or set of related studies.

If one research design is weak in one area, then another research design can cover that weakness. For instance, a dissertation analyzing different situations or cases will have more than one research design.

For example:

- Experimental research involves experimental investigation and laboratory experience, but it does not accurately investigate the real world.

- Quantitative research is good for the statistical part of the project, but it may not provide an in-depth understanding of the topic .

- Also, correlational research will not provide experimental results because it is a technique that assesses the statistical relationship between two variables.

While scientific considerations are a fundamental aspect of the research design, It is equally important that the researcher think practically before deciding on its structure. Here are some questions that you should think of;

- Do you have enough time to gather data and complete the write-up?

- Will you be able to collect the necessary data by interviewing a specific person or visiting a specific location?

- Do you have in-depth knowledge about the different statistical analysis and data collection techniques to address the research questions or test the hypothesis ?

If you think that the chosen research design cannot answer the research questions properly, you can refine your research questions to gain better insight.

Step 2: Data Type you Need for Research

Decide on the type of data you need for your research. The type of data you need to collect depends on your research questions or research hypothesis. Two types of research data can be used to answer the research questions:

Primary Data Vs. Secondary Data

| The researcher collects the primary data from first-hand sources with the help of different data collection methods such as interviews, experiments, surveys, etc. Primary research data is considered far more authentic and relevant, but it involves additional cost and time. | |

| Research on academic references which themselves incorporate primary data will be regarded as secondary data. There is no need to do a survey or interview with a person directly, and it is time effective. The researcher should focus on the validity and reliability of the source. |

Qualitative Vs. Quantitative Data

| This type of data encircles the researcher’s descriptive experience and shows the relationship between the observation and collected data. It involves interpretation and conceptual understanding of the research. There are many theories involved which can approve or disapprove the mathematical and statistical calculation. For instance, you are searching how to write a research design proposal. It means you require qualitative data about the mentioned topic. | |

| If your research requires statistical and mathematical approaches for measuring the variable and testing your hypothesis, your objective is to compile quantitative data. Many businesses and researchers use this type of data with pre-determined data collection methods and variables for their research design. |

Also, see; Research methods, design, and analysis .

Need help with a thesis chapter?

- Hire an expert from ResearchProspect today!

- Statistical analysis, research methodology, discussion of the results or conclusion – our experts can help you no matter how complex the requirements are.

Step 3: Data Collection Techniques

Once you have selected the type of research to answer your research question, you need to decide where and how to collect the data.

It is time to determine your research method to address the research problem . Research methods involve procedures, techniques, materials, and tools used for the study.

For instance, a dissertation research design includes the different resources and data collection techniques and helps establish your dissertation’s structure .

The following table shows the characteristics of the most popularly employed research methods.

Research Methods

| Methods | What to consider |

|---|---|

| Surveys | The survey planning requires; Selection of responses and how many responses are required for the research? Survey distribution techniques (online, by post, in person, etc.) Techniques to design the question |

| Interviews | Criteria to select the interviewee. Time and location of the interview. Type of interviews; i.e., structured, semi-structured, or unstructured |

| Experiments | Place of the experiment; laboratory or in the field. Measuring of the variables Design of the experiment |

| Secondary Data | Criteria to select the references and source for the data. The reliability of the references. The technique used for compiling the data source. |

Step 4: Procedure of Data Analysis

Use of the correct data and statistical analysis technique is necessary for the validity of your research. Therefore, you need to be certain about the data type that would best address the research problem. Choosing an appropriate analysis method is the final step for the research design. It can be split into two main categories;

Quantitative Data Analysis

The quantitative data analysis technique involves analyzing the numerical data with the help of different applications such as; SPSS, STATA, Excel, origin lab, etc.

This data analysis strategy tests different variables such as spectrum, frequencies, averages, and more. The research question and the hypothesis must be established to identify the variables for testing.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative data analysis of figures, themes, and words allows for flexibility and the researcher’s subjective opinions. This means that the researcher’s primary focus will be interpreting patterns, tendencies, and accounts and understanding the implications and social framework.

You should be clear about your research objectives before starting to analyze the data. For example, you should ask yourself whether you need to explain respondents’ experiences and insights or do you also need to evaluate their responses with reference to a certain social framework.

Step 5: Write your Research Proposal

The research design is an important component of a research proposal because it plans the project’s execution. You can share it with the supervisor, who would evaluate the feasibility and capacity of the results and conclusion .

Read our guidelines to write a research proposal if you have already formulated your research design. The research proposal is written in the future tense because you are writing your proposal before conducting research.

The research methodology or research design, on the other hand, is generally written in the past tense.

How to Write a Research Design – Conclusion

A research design is the plan, structure, strategy of investigation conceived to answer the research question and test the hypothesis. The dissertation research design can be classified based on the type of data and the type of analysis.

Above mentioned five steps are the answer to how to write a research design. So, follow these steps to formulate the perfect research design for your dissertation .

ResearchProspect writers have years of experience creating research designs that align with the dissertation’s aim and objectives. If you are struggling with your dissertation methodology chapter, you might want to look at our dissertation part-writing service.

Our dissertation writers can also help you with the full dissertation paper . No matter how urgent or complex your need may be, ResearchProspect can help. We also offer PhD level research paper writing services.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is research design.

Research design is a systematic plan that guides the research process, outlining the methodology and procedures for collecting and analysing data. It determines the structure of the study, ensuring the research question is answered effectively, reliably, and validly. It serves as the blueprint for the entire research project.

How to write a research design?

To write a research design, define your research question, identify the research method (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed), choose data collection techniques (e.g., surveys, interviews), determine the sample size and sampling method, outline data analysis procedures, and highlight potential limitations and ethical considerations for the study.

How to write the design section of a research paper?

In the design section of a research paper, describe the research methodology chosen and justify its selection. Outline the data collection methods, participants or samples, instruments used, and procedures followed. Detail any experimental controls, if applicable. Ensure clarity and precision to enable replication of the study by other researchers.

How to write a research design in methodology?

To write a research design in methodology, clearly outline the research strategy (e.g., experimental, survey, case study). Describe the sampling technique, participants, and data collection methods. Detail the procedures for data collection and analysis. Justify choices by linking them to research objectives, addressing reliability and validity.

You May Also Like

Struggling to find relevant and up-to-date topics for your dissertation? Here is all you need to know if unsure about how to choose dissertation topic.

Repository of ten perfect research question examples will provide you a better perspective about how to create research questions.

How to write a hypothesis for dissertation,? A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested with the help of experimental or theoretical research.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Blueprints for Academic Research Projects

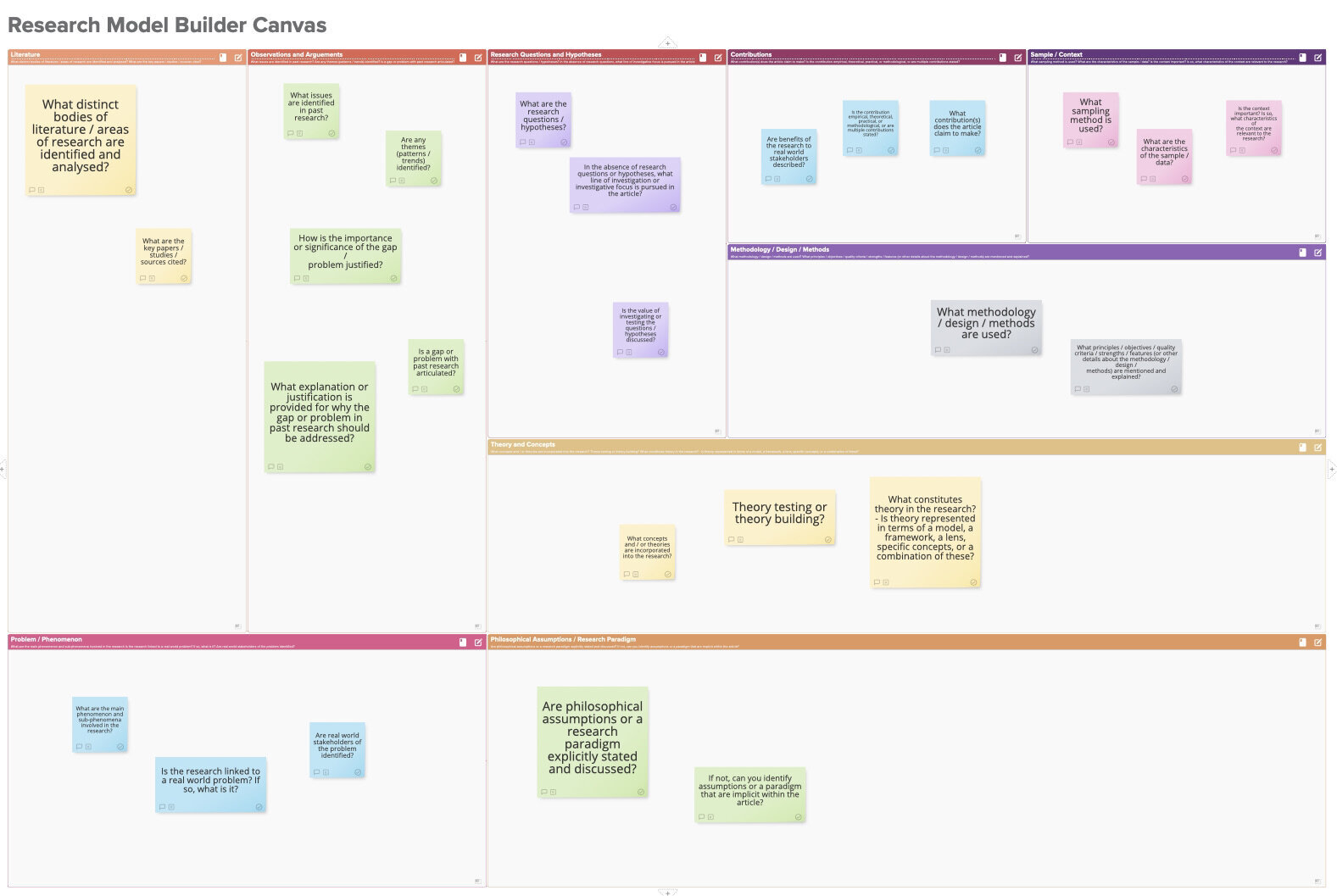

Today's post is written by Dr. Ben Ellway, the founder of www.academic-toolkit.com . Ben completed his Ph.D. at The University of Cambridge and created the Research Design Canvas , a multipurpose tool for learning about academic research and designing a research project.

Based on requests from students for examples of completed research canvases, Ben created the Research Model Builder Canvas .

This canvas modifies the original questions in the nine building blocks to enable students to search for key information in a journal article and then reassemble it on the canvas to form a research model — a single-page visual summary of the journal article which captures how the research was designed and conducted.

Ben’s second book, Building Research Models, explains how to use the Research Model Builder Canvas to become a more confident and competent reader of academic journal articles, while simultaneously building research models to use as blueprints to guide the design of your own project .

Ben has created a template for Stormboard based on this tool and this is his brief guide on how to begin using it.

Starting with a blank page can be daunting

The Research Design Canvas brings together the key building blocks of academic research on a single page and provides targeted questions to help you design your own project. However, starting with a blank page can be a daunting prospect!

Academic research is complex as it involves multiple components, so designing and conducting your own project can be overwhelming, especially if you lack confidence in making decisions or are confused about how the components of a project fit together. It is much easier to start a complex task and long process such as designing a research project when you have an existing research model or ‘blueprint’ to work from.

Starting with a ‘blueprint’ — tailored to your topic area — is much easier

Using the Research Model Builder Canvas, you can transform a journal article in your topic into a research model or blueprint — a single-page visualization of how a project was designed and conducted.

The research model — and equally importantly the process of building it — will improve your understanding of academic research, and will also provide you with a personalized learning resource for your Thesis. You can use the research model as a blueprint to refer to specific decisions and their justification, and how components of research fit together, to help you begin to build your own project.

Obviously, each project is unique so you’ll be using the blueprint as a guide rather than as a ‘cookie cutter’ solution. Seeing the components of a completed research project together on a single page (which you produced from a ten or twenty-page journal article) — is a very powerful learning resource to have on your academic research journey.

Build research models on Stormboard

If you prefer to work digitally rather than with paper and pen, you can use the Research Model Builder Canvas Template in Stormboard.

By using the Stormboard template, you’ll be able to identify key content and points from the journal article and then quickly summarize these on digital sticky notes. You can easily edit the sticky notes to rearrange, delete, or expand upon the ideas and points. You can then refer back to the permanent visual research model you created, share it with fellow students, or discuss it with your supervisors.

What are the building blocks of the research model?

The template has nine building blocks.

The original questions in the building blocks of the research design canvas are modified in the research model builder canvas. They are designed to help you locate the most important points, decisions, and details in a journal article.

A brief introduction to the purpose of each building block is provided below to help you familiarize yourself with the research model you will build.

Phenomenon / Problem

What does the research focus on? What were the main ‘things’ investigated and discussed in the journal article? Did the research involve a real-world problem?

What area (or areas) of past literature are identified and introduced? Which sources are especially important?

Observations & Arguments

What are the most crucial points made by the authors in their analysis of past research? What evidence, issues, and themes are the focus of the literature review? Is a gap in past research identified?

Research Questions / Hypotheses

What are the research questions and/or hypotheses? How are they justified? If none are stated, what line of investigation is pursued?

Theory & Concepts

Does the research involve a theoretical or conceptual component? If so, what are the key concepts / theory? What role do they play in the research?

Methodology / Design / Methods

What methods and data were used? How are the decisions justified?

Sample / Context

What sampling method is used? Is the research context important?

Contributions

What contribution(s) do the authors claim that their research makes? Is the value-add more academically or practically-oriented? Are real-world stakeholders and the implications for them mentioned?

Philosophical Assumptions / Research Paradigm

These are not usually mentioned or discussed in journal articles. Indeed, this building block can be confusing if you are not familiar with research philosophy or are confused by its seemingly abstract focus. If you understand these ideas, can you identify any implicit assumptions or a research paradigm in the article?

Compare two research models to appreciate the diversity of research

The easiest way to increase your appreciation of the different types and ways of conducting academic research is to build multiple research models.

Start by building two models. Compare and contrast them. Which decisions and aspects are similar and which are different? What can you learn from each research model and how can this help you when designing your own research and Thesis?

Building research models will help you to appreciate the diversity in the different types of research conducted in your topic area.

Transforming a ten or twenty-page journal article into a single-page visual summary is a powerful way to learn about how academic research is designed and conducted — and also what a completed research project looks like.

The Stormboard template makes the process of building research models easy, and the ability to save, edit, and share them ensures that you’ll be able to refer back to these blueprints at various stages throughout your research journey and Thesis writing process.

When you get confused, become stuck, or feel overwhelmed by the complexity of academic research, you can fall back on the research models you created to guide you and get you back on track. Good luck!

Are you interested in trying the Research Model Builder Canvas? Sign up for a free trial now!

Keep reading.

A Retrospective meeting (or Retrospective sprint as it is sometimes called) is a step in the Agile model that allows for teams to take an overall look at what they have done over a period of time — a week, a month, etc. — to determine what’s working for them and what’s not.

Get free Save the Cat and 5-act beat board templates with Stormboard! Simplify your writing process with unlimited space, seamless collaboration, and easy recovery of discarded ideas. Perfect for novelists and screenwriters, our templates help you map out your story visually and clearly.

Discover the unspoken challenges faced by developers in agile teams. This blog reveals the core issues beyond common complaints, helping scrum masters improve team dynamics and productivity.

Explore the counterintuitive idea that even well-functioning teams with solid brainstorming sessions can benefit from AI. By playing the role of the devil's advocate, AI can introduce healthy disagreement and challenge the status quo, potentially leading to groundbreaking ideas.

If your Agile team uses the Scrum methodology, you are probably already practicing Daily Standup meetings (or Daily Scrum meetings). These meetings are an essential part of Scrum that should be done to keep the process on track. What is…

Enterprise organizations who have adopted the highly-effective Agile PI Planning strategy, have recently been forced to do their planning sessions remotely…

By definition, the word Agile means the “ability to move with quick, easy grace.” While this is how most of us would define Agile, the term has grown over the years to have a much more diverse, broad meaning — especially in the business world.

In today's evolving work environment, creating agile teams can change the face of team building in the modern workplace. Learn more about how you can manage your agile teams easily - whether you are in office, remote, or hybrid.

Explore the hidden costs of excessive meetings in Agile environments and learn how to streamline your team's workflow for optimal productivity. Discover practical solutions to common complaints and transform your meetings into valuable assets that drive efficiency and collaboration.

Discover the latest advancements in StormAI, the industry's first augmented intelligence collaborator, with exciting updates that enhance its capabilities. Learn about the innovative features and improvements that make StormAI 2.0 a groundbreaking technology for collaborative work.

Discover the contrasting views within the Agile community regarding spilled stories (or spillover) in sprint cycles and delve into strategies adopted by different teams. Gain insights into the pros and cons of each approach to better inform your Agile methodology.

Uncover the pivotal role collaborative platforms play in facilitating a seamless transition towards sustainable energy solutions. From project management to real-time communication, explore how these tools are reshaping the landscape for utility companies amidst the push for renewable energy adoption.

How to Track Your Team’s Workflow Remotely

Archive - 2021 business trends.

Creating Models in Psychological Research

- © 2015

- Olivier Mesly 0

University of Québec in Outaouais, Gatineau, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Complimentary to traditional books on methodology

- Develops flawless models that will support thinking and research endeavors

- Presents effective techniques to perform qualitative and quantitative research

- Includes supplementary material: sn.pub/extras

Part of the book series: SpringerBriefs in Psychology (BRIEFSPSYCHOL)

8548 Accesses

14 Citations

54 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

This concise reference serves as a companion to traditional research texts by focusing on such essentials as model construction, robust methodologies and defending a compelling hypothesis. Designed to wean Master's and doctorate-level students as well as new researchers from their comfort zones, the book challenges readers to engage in multi-method approaches to answering multidisciplinary questions. The result is a step-by-step framework for producing well-organized, credible papers based on rigorous, error-free data.

The text begins with a brief grounding in the intellectual attitude and logical stance that underlie good research and how they relate to steps such as refining a topic, creating workable models and building the right amount of complexity. Accessible examples from psychology and business help readers grasp the fine points of observations, interviewing, simulations, interpreting and finalizing data and presenting results. Fleshed out with figures, tables, key terms, tips, and questions, this book acts as both a friendly lecturer and a multilevel reality check.

Similar content being viewed by others

Structural Equation Modeling: Principles, Processes, and Practices

Addressing the theory crisis in psychology

The Role of Theory in Behavior Analysis: A Response to Unfinished Business , Travis Thompson’s Review of Staddon's New Behaviorism (2 nd edition)

- auto-ethnography

- conducting research

- consolidated model of financial predation

- data percolation

- marketing theory

- methodology

- modeling in social sciences

- multidisciplinary research

- operations management

- qualitative and quantitative methods

- qualitative and quantitative research

- questionnaires

- research topics

- social sciences

Table of contents (10 chapters)

Front matter, general principles.

Olivier Mesly

Bubbles and Arrows

Basic principles, building complexity, more on data percolation, some qualitative techniques, simulation and quantitative techniques, the hypothetico-deductive method, steps to finalizing the research, back matter, authors and affiliations, about the author.

Olivier Mesly obtained a doctorate in marketing after which he completed a post-degree term at HEC Montreal. His area of specialization- the emotional relationship between sellers and buyers- eventually focused on one particular area of interest: the psychology of investors. He has written a number of scientific articles on behavioral finance and his approach has found applications not only is psychology, but also in the legal field and project management. He works closely with a number of psychologists and is involved in many research activities including in virtual reality and f MRI as well as being a member of the LAPS (Laboratory for psychoneuroendocrinological analyses). He recently won the best presentation award at the Psychology outside the Box forum held in Ottawa in 2014.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Creating Models in Psychological Research

Authors : Olivier Mesly

Series Title : SpringerBriefs in Psychology

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15753-5

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science , Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Copyright Information : Author 2015

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-319-15752-8 Published: 31 March 2015

eBook ISBN : 978-3-319-15753-5 Published: 21 March 2015

Series ISSN : 2192-8363

Series E-ISSN : 2192-8371

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XXI, 126

Number of Illustrations : 2 b/w illustrations, 58 illustrations in colour

Topics : Psychological Methods/Evaluation

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How To Make Conceptual Framework (With Examples and Templates)

We all know that a research paper has plenty of concepts involved. However, a great deal of concepts makes your study confusing.

A conceptual framework ensures that the concepts of your study are organized and presented comprehensively. Let this article guide you on how to make the conceptual framework of your study.

Related: How to Write a Concept Paper for Academic Research

Table of Contents

At a glance: free conceptual framework templates.

Too busy to create a conceptual framework from scratch? No problem. We’ve created templates for each conceptual framework so you can start on the right foot. All you need to do is enter the details of the variables. Feel free to modify the design according to your needs. Please read the main article below to learn more about the conceptual framework.

Conceptual Framework Template #1: Independent-Dependent Variable Model

Conceptual framework template #2: input-process-output (ipo) model, conceptual framework template #3: concept map, what is a conceptual framework.

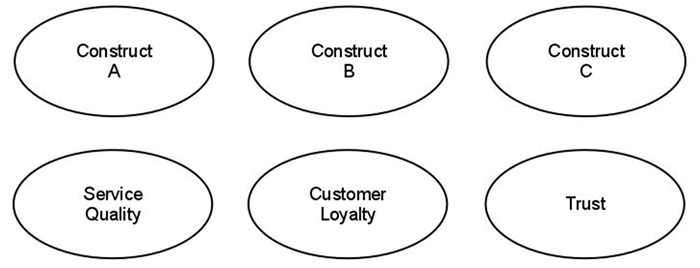

A conceptual framework shows the relationship between the variables of your study. It includes a visual diagram or a model that summarizes the concepts of your study and a narrative explanation of the model presented.

Why Should Research Be Given a Conceptual Framework?

Imagine your study as a long journey with the research result as the destination. You don’t want to get lost in your journey because of the complicated concepts. This is why you need to have a guide. The conceptual framework keeps you on track by presenting and simplifying the relationship between the variables. This is usually done through the use of illustrations that are supported by a written interpretation.

Also, people who will read your research must have a clear guide to the variables in your study and where the research is heading. By looking at the conceptual framework, the readers can get the gist of the research concepts without reading the entire study.

Related: How to Write Significance of the Study (with Examples)

What Is the Difference Between Conceptual Framework and Theoretical Framework?

| You can develop this through the researcher’s specific concept in the study. | Purely based on existing theories. |

| The research problem is backed up by existing knowledge regarding things the researcher wants us to discover about the topic. | The research problem is supported using past relevant theories from existing literature. |

| Based on acceptable and logical findings. | It is established with the help of the research paradigm. |

| It emphasizes the historical background and the structure to fill in the knowledge gap. | A general set of ideas and theories is essential in writing this area. |

| It highlights the fundamental concepts characterizing the study variable. | It emphasizes the historical background and the structure to fill the knowledge gap. |

Both of them show concepts and ideas of your study. The theoretical framework presents the theories, rules, and principles that serve as the basis of the research. Thus, the theoretical framework presents broad concepts related to your study. On the other hand, the conceptual framework shows a specific approach derived from the theoretical framework. It provides particular variables and shows how these variables are related.

Let’s say your research is about the Effects of Social Media on the Political Literacy of College Students. You may include some theories related to political literacy, such as this paper, in your theoretical framework. Based on this paper, political participation and awareness determine political literacy.

For the conceptual framework, you may state that the specific form of political participation and awareness you will use for the study is the engagement of college students on political issues on social media. Then, through a diagram and narrative explanation, you can show that using social media affects the political literacy of college students.

What Are the Different Types of Conceptual Frameworks?

The conceptual framework has different types based on how the research concepts are organized 1 .

1. Taxonomy

In this type of conceptual framework, the phenomena of your study are grouped into categories without presenting the relationship among them. The point of this conceptual framework is to distinguish the categories from one another.

2. Visual Presentation

In this conceptual framework, the relationship between the phenomena and variables of your study is presented. Using this conceptual framework implies that your research provides empirical evidence to prove the relationship between variables. This is the type of conceptual framework that is usually used in research studies.

3. Mathematical Description

In this conceptual framework, the relationship between phenomena and variables of your study is described using mathematical formulas. Also, the extent of the relationship between these variables is presented with specific quantities.

How To Make Conceptual Framework: 4 Steps

1. identify the important variables of your study.

There are two essential variables that you must identify in your study: the independent and the dependent variables.

An independent variable is a variable that you can manipulate. It can affect the dependent variable. Meanwhile, the dependent variable is the resulting variable that you are measuring.

You may refer to your research question to determine your research’s independent and dependent variables.

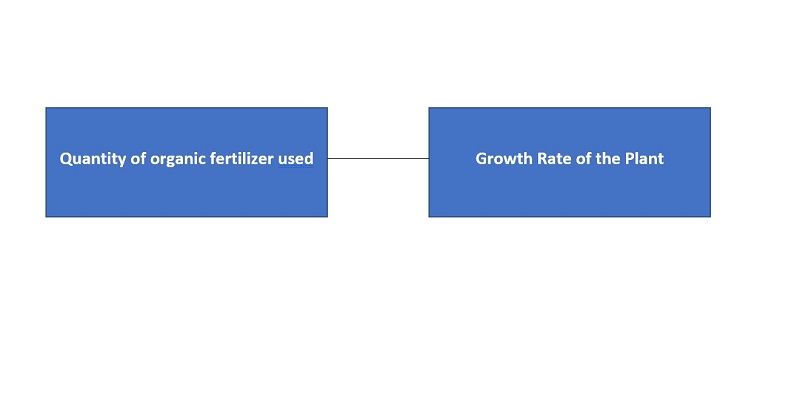

Suppose your research question is: “Is There a Significant Relationship Between the Quantity of Organic Fertilizer Used and the Plant’s Growth Rate?” The independent variable of this study is the quantity of organic fertilizer used, while the dependent variable is the plant’s growth rate.

2. Think About How the Variables Are Related

Usually, the variables of a study have a direct relationship. If a change in one of your variables leads to a corresponding change in another, they might have this kind of relationship.

However, note that having a direct relationship between variables does not mean they already have a cause-and-effect relationship 2 . It takes statistical analysis to prove causation between variables.

Using our example earlier, the quantity of organic fertilizer may directly relate to the plant’s growth rate. However, we are not sure that the quantity of organic fertilizer is the sole reason for the plant’s growth rate changes.

3. Analyze and Determine Other Influencing Variables

Consider analyzing if other variables can affect the relationship between your independent and dependent variables 3 .

4. Create a Visual Diagram or a Model

Now that you’ve identified the variables and their relationship, you may create a visual diagram summarizing them.

Usually, shapes such as rectangles, circles, and arrows are used for the model. You may create a visual diagram or model for your conceptual framework in different ways. The three most common models are the independent-dependent variable model, the input-process-output (IPO) model, and concept maps.

a. Using the Independent-Dependent Variable Model

You may create this model by writing the independent and dependent variables inside rectangles. Then, insert a line segment between them, connecting the rectangles. This line segment indicates the direct relationship between these variables.

Below is a visual diagram based on our example about the relationship between organic fertilizer and a plant’s growth rate.

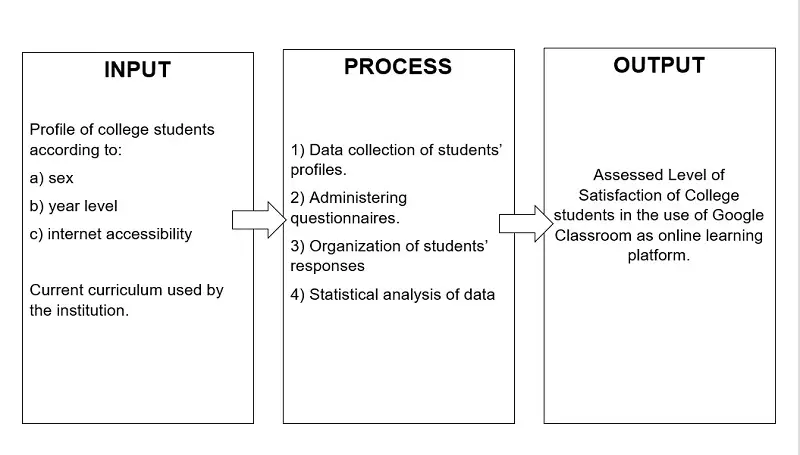

b. Using the Input-Process-Output (IPO) Model

If you want to emphasize your research process, the input-process-output model is the appropriate visual diagram for your conceptual framework.

To create your visual diagram using the IPO model, follow these steps:

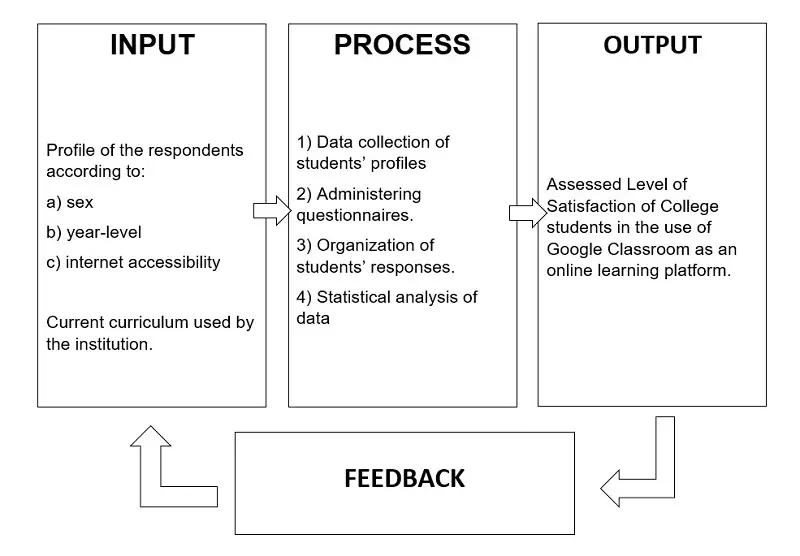

- Determine the inputs of your study . Inputs are the variables you will use to arrive at your research result. Usually, your independent variables are also the inputs of your research. Let’s say your research is about the Level of Satisfaction of College Students Using Google Classroom as an Online Learning Platform. You may include in your inputs the profile of your respondents and the curriculum used in the online learning platform.

- Outline your research process. Using our example above, the research process should be like this: Data collection of student profiles → Administering questionnaires → Tabulation of students’ responses → Statistical data analysis.

- State the research output . Indicate what you are expecting after you conduct the research. In our example above, the research output is the assessed level of satisfaction of college students with the use of Google Classroom as an online learning platform.

- Create the model using the research’s determined input, process, and output.

Presented below is the IPO model for our example above.

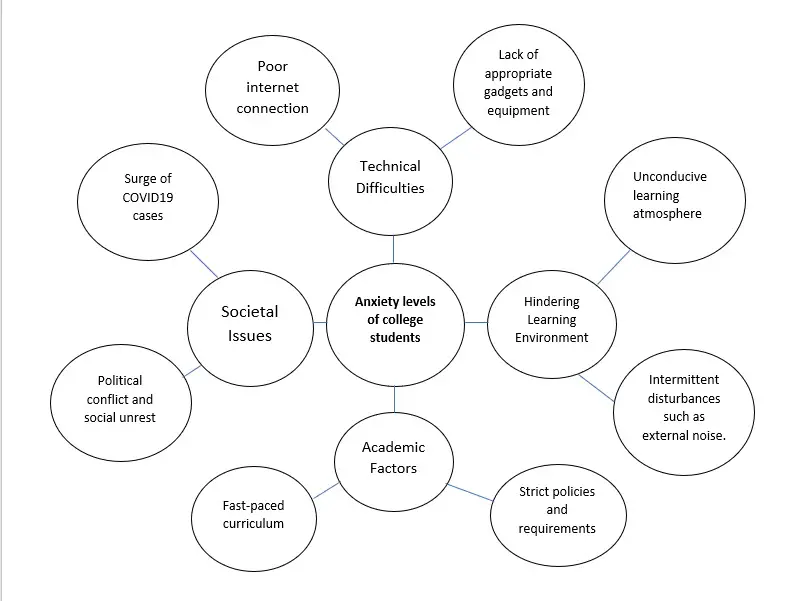

c. Using Concept Maps

If you think the two models presented previously are insufficient to summarize your study’s concepts, you may use a concept map for your visual diagram.

A concept map is a helpful visual diagram if multiple variables affect one another. Let’s say your research is about Coping with the Remote Learning System: Anxiety Levels of College Students. Presented below is the concept map for the research’s conceptual framework:

5. Explain Your Conceptual Framework in Narrative Form

Provide a brief explanation of your conceptual framework. State the essential variables, their relationship, and the research outcome.

Using the same example about the relationship between organic fertilizer and the growth rate of the plant, we can come up with the following explanation to accompany the conceptual framework:

Figure 1 shows the Conceptual Framework of the study. The quantity of the organic fertilizer used is the independent variable, while the plant’s growth is the research’s dependent variable. These two variables are directly related based on the research’s empirical evidence.

Conceptual Framework in Quantitative Research

You can create your conceptual framework by following the steps discussed in the previous section. Note, however, that quantitative research has statistical analysis. Thus, you may use arrows to indicate a cause-and-effect relationship in your model. An arrow implies that your independent variable caused the changes in your dependent variable.

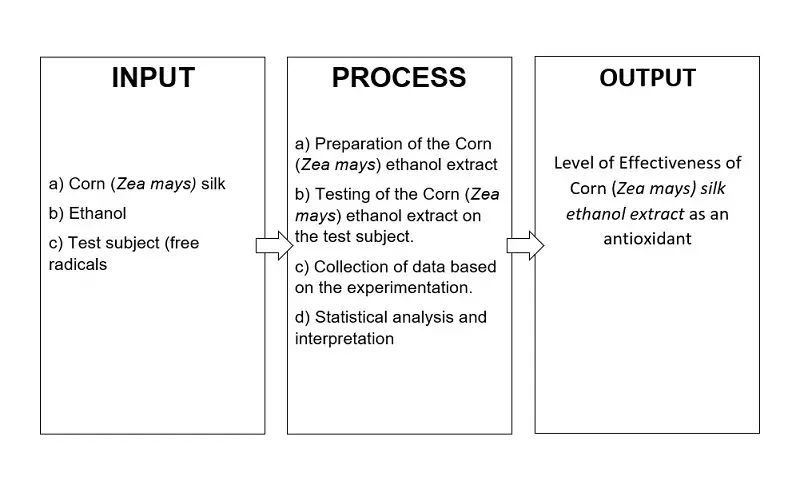

Usually, for quantitative research, the Input-Process-Output model is used as a visual diagram. Here is an example of a conceptual framework in quantitative research:

Research Topic : Level of Effectiveness of Corn (Zea mays) Silk Ethanol Extract as an Antioxidant

Conceptual Framework in Qualitative Research

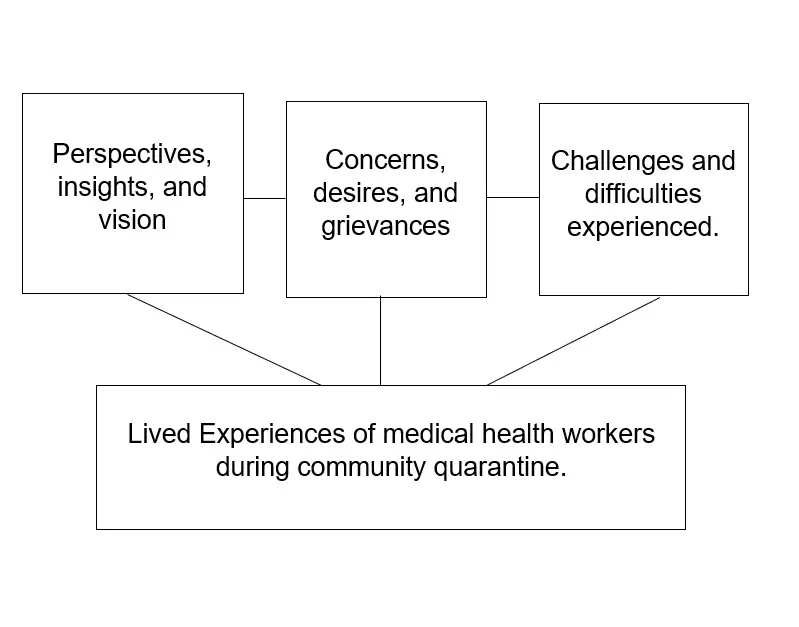

Again, you can follow the same step-by-step guide discussed previously to create a conceptual framework for qualitative research. However, note that you should avoid using one-way arrows as they may indicate causation . Qualitative research cannot prove causation since it uses only descriptive and narrative analysis to relate variables.

Here is an example of a conceptual framework in qualitative research:

Research Topic : Lived Experiences of Medical Health Workers During Community Quarantine

Conceptual Framework Examples

Presented below are some examples of conceptual frameworks.

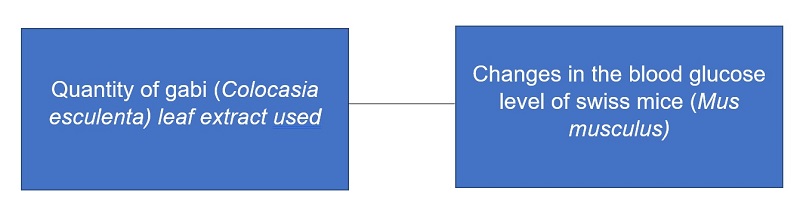

Research Topic : Hypoglycemic Ability of Gabi (Colocasia esculenta) Leaf Extract in the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice (Mus musculus)

Figure 1 presents the Conceptual Framework of the study. The quantity of gabi leaf extract is the independent variable, while the Swiss mice’s blood glucose level is the study’s dependent variable. This study establishes a direct relationship between these variables through empirical evidence and statistical analysis .

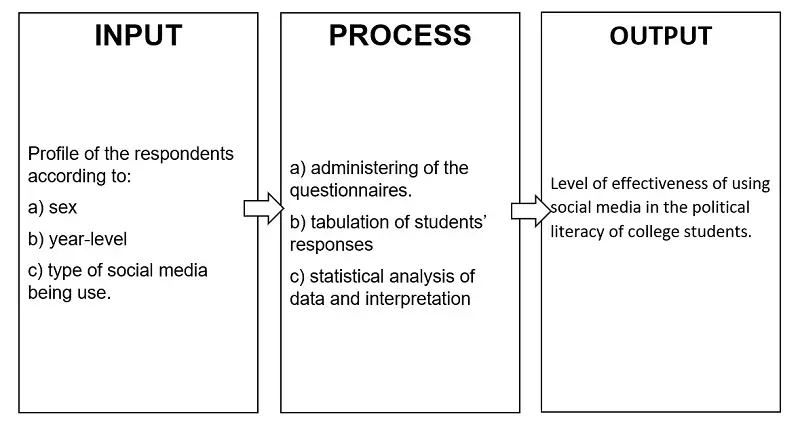

Research Topic : Level of Effectiveness of Using Social Media in the Political Literacy of College Students

Figure 1 shows the Conceptual Framework of the study. The input is the profile of the college students according to sex, year level, and the social media platform being used. The research process includes administering the questionnaires, tabulating students’ responses, and statistical data analysis and interpretation. The output is the effectiveness of using social media in the political literacy of college students.

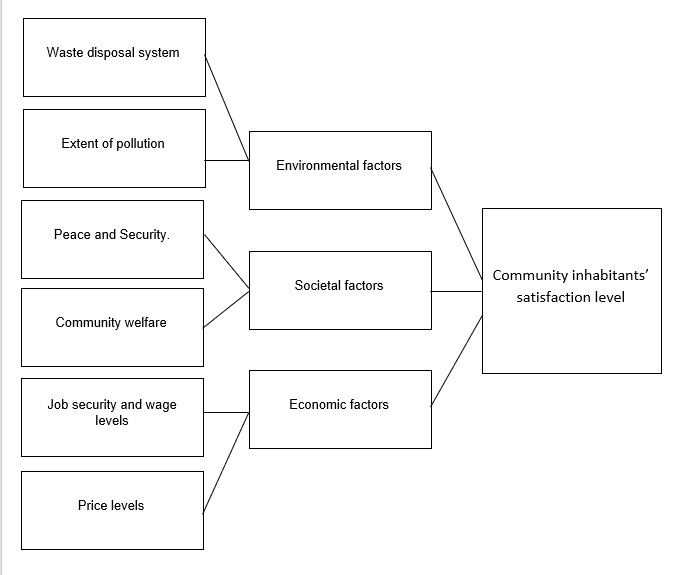

Research Topic: Factors Affecting the Satisfaction Level of Community Inhabitants

Figure 1 presents a visual illustration of the factors that affect the satisfaction level of community inhabitants. As presented, environmental, societal, and economic factors influence the satisfaction level of community inhabitants. Each factor has its indicators which are considered in this study.

Tips and Warnings

- Please keep it simple. Avoid using fancy illustrations or designs when creating your conceptual framework.

- Allot a lot of space for feedback. This is to show that your research variables or methodology might be revised based on the input from the research panel. Below is an example of a conceptual framework with a spot allotted for feedback.

Frequently Asked Questions

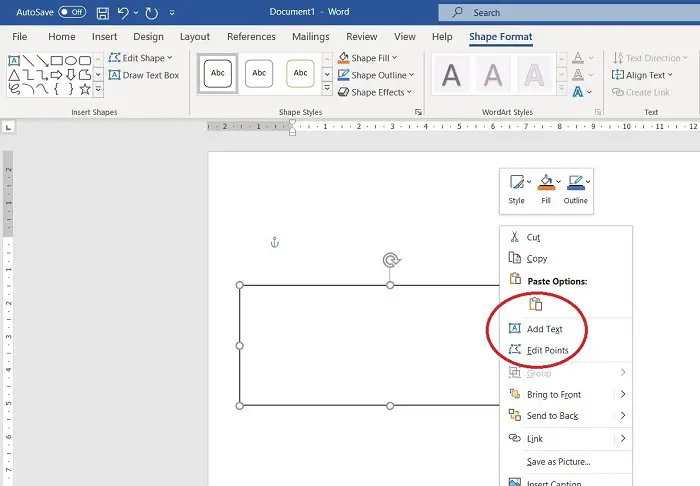

1. how can i create a conceptual framework in microsoft word.

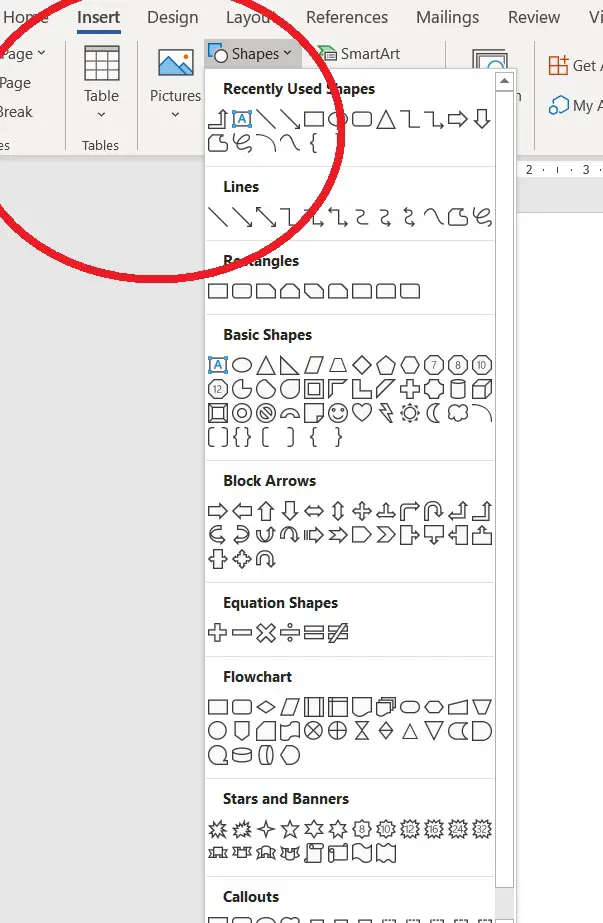

First, click the Insert tab and select Shapes . You’ll see a wide range of shapes to choose from. Usually, rectangles, circles, and arrows are the shapes used for the conceptual framework.

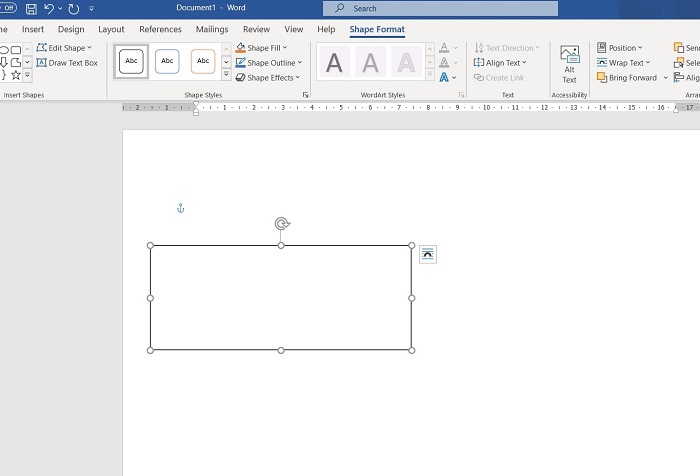

Next, draw your selected shape in the document.

Insert the name of the variable inside the shape. You can do this by pointing your cursor to the shape, right-clicking your mouse, selecting Add Text , and typing in the text.

Repeat the same process for the remaining variables of your study. If you need arrows to connect the different variables, you can insert one by going to the Insert tab, then Shape, and finally, Lines or Block Arrows, depending on your preferred arrow style.

2. How to explain my conceptual framework in defense?

If you have used the Independent-Dependent Variable Model in creating your conceptual framework, start by telling your research’s variables. Afterward, explain the relationship between these variables. Example: “Using statistical/descriptive analysis of the data we have collected, we are going to show how the <state your independent variable> exhibits a significant relationship to <state your dependent variable>.”

On the other hand, if you have used an Input-Process-Output Model, start by explaining the inputs of your research. Then, tell them about your research process. You may refer to the Research Methodology in Chapter 3 to accurately present your research process. Lastly, explain what your research outcome is.

Meanwhile, if you have used a concept map, ensure you understand the idea behind the illustration. Discuss how the concepts are related and highlight the research outcome.

3. In what stage of research is the conceptual framework written?

The research study’s conceptual framework is in Chapter 2, following the Review of Related Literature.

4. What is the difference between a Conceptual Framework and Literature Review?

The Conceptual Framework is a summary of the concepts of your study where the relationship of the variables is presented. On the other hand, Literature Review is a collection of published studies and literature related to your study.

Suppose your research concerns the Hypoglycemic Ability of Gabi (Colocasia esculenta) Leaf Extract on Swiss Mice (Mus musculus). In your conceptual framework, you will create a visual diagram and a narrative explanation presenting the quantity of gabi leaf extract and the mice’s blood glucose level as your research variables. On the other hand, for the literature review, you may include this study and explain how this is related to your research topic.

5. When do I use a two-way arrow for my conceptual framework?

You will use a two-way arrow in your conceptual framework if the variables of your study are interdependent. If variable A affects variable B and variable B also affects variable A, you may use a two-way arrow to show that A and B affect each other.

Suppose your research concerns the Relationship Between Students’ Satisfaction Levels and Online Learning Platforms. Since students’ satisfaction level determines the online learning platform the school uses and vice versa, these variables have a direct relationship. Thus, you may use two-way arrows to indicate that the variables directly affect each other.

- Conceptual Framework – Meaning, Importance and How to Write it. (2020). Retrieved 27 April 2021, from https://afribary.com/knowledge/conceptual-framework/

- Correlation vs Causation. Retrieved 27 April 2021, from https://www.jmp.com/en_ph/statistics-knowledge-portal/what-is-correlation/correlation-vs-causation.html

- Swaen, B., & George, T. (2022, August 22). What is a conceptual framework? Tips & Examples. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/conceptual-framework/

Written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

in Career and Education , Juander How

Jewel Kyle Fabula

Jewel Kyle Fabula is a Bachelor of Science in Economics student at the University of the Philippines Diliman. His passion for learning mathematics developed as he competed in some mathematics competitions during his Junior High School years. He loves cats, playing video games, and listening to music.

Browse all articles written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

How to develop a graphical framework to chart your research

Graphic representations or frameworks can be powerful tools to explain research processes and outcomes. David Waller explains how researchers can develop effective visual models to chart their work

David Waller

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} It’s time: how to get your department off X

Deepfakes are coming for education. be prepared, campus webinar: the evolution of interdisciplinarity, emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn, relieve student boredom by ‘activating’ lectures.

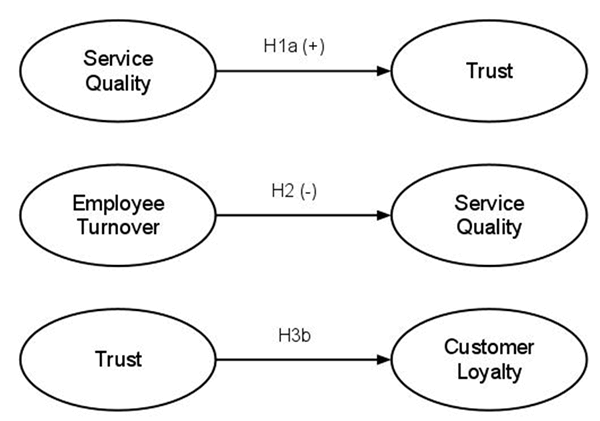

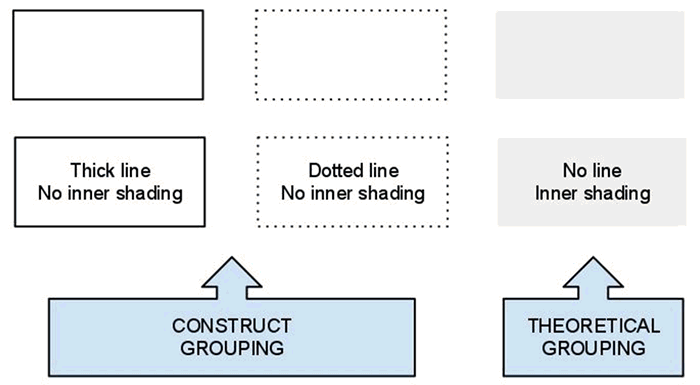

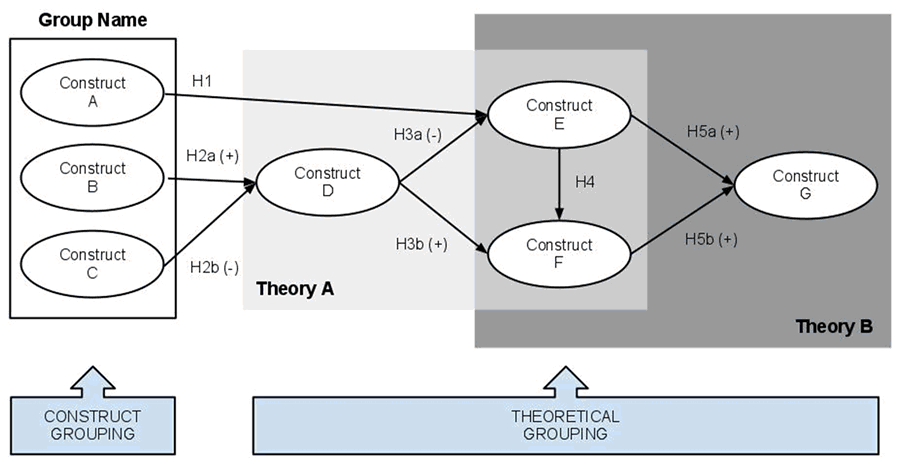

While undertaking a study, researchers can uncover insights, connections and findings that are extremely valuable to anyone likely to read their eventual paper. Thus, it is important for the researcher to clearly present and explain the ideas and potential relationships. One important way of presenting findings and relationships is by developing a graphical conceptual framework.

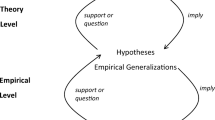

A graphical conceptual framework is a visual model that assists readers by illustrating how concepts, constructs, themes or processes work. It is an image designed to help the viewer understand how various factors interrelate and affect outcomes, such as a chart, graph or map.

These are commonly used in research to show outcomes but also to create, develop, test, support and criticise various ideas and models. The use of a conceptual framework can vary depending on whether it is being used for qualitative or quantitative research.

- Using literature reviews to strengthen research: tips for PhDs and supervisors

- Get your research out there: 7 strategies for high-impact science communication

- Understanding peer review: what it is, how it works and why it is important

There are many forms that a graphical conceptual framework can take, which can depend on the topic, the type of research or findings, and what can best present the story.

Below are examples of frameworks based on qualitative and quantitative research.

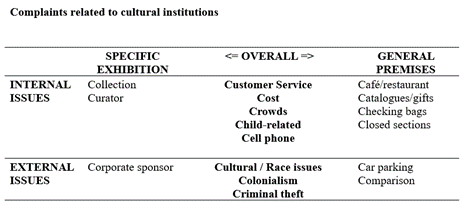

As shown by the table below, in qualitative research the conceptual framework is developed at the end of the study to illustrate the factors or issues presented in the qualitative data. It is designed to assist in theory building and the visual understanding of the exploratory findings. It can also be used to develop a framework in preparation for testing the proposition using quantitative research.

In quantitative research a conceptual framework can be used to synthesise the literature and theoretical concepts at the beginning of the study to present a model that will be tested in the statistical analysis of the research.

| Introduction | Introduction |

| Background/lit review | Background/lit review |

| Methodology |

|

| Findings | Methodology |

| Discussion | Findings |

|

| Discussion |

| Conclusion | Conclusion |

It is important to understand that the role of a conceptual framework differs depending on the type of research that is being undertaken.

So how should you go about creating a conceptual framework? After undertaking some studies where I have developed conceptual frameworks, here is a simple model based on “Six Rs”: Review, Reflect, Relationships, Reflect, Review, and Repeat.

Process for developing conceptual frameworks:

Review: literature/themes/theory.

Reflect: what are the main concepts/issues?

Relationships: what are their relationships?

Reflect: does the diagram represent it sufficiently?

Review: check it with theory, colleagues, stakeholders, etc.

Repeat: review and revise it to see if something better occurs.

This is not an easy process. It is important to begin by reviewing what has been presented in previous studies in the literature or in practice. This provides a solid background to the proposed model as it can show how it relates to accepted theoretical concepts or practical examples, and helps make sure that it is grounded in logical sense.

It can start with pen and paper, but after reviewing you should reflect to consider if the proposed framework takes into account the main concepts and issues, and the potential relationships that have been presented on the topic in previous works.

It may take a few versions before you are happy with the final framework, so it is worth continuing to reflect on the model and review its worth by reassessing it to determine if the model is consistent with the literature and theories. It can also be useful to discuss the idea with colleagues or to present preliminary ideas at a conference or workshop – be open to changes.