Essay On My School Canteen

- Post category: Essay

- Reading time: 7 mins read

The canteen in my school provides students, teachers and other staff with delicious food and drink in hygienic condition. I know that instead of buying things from roadside sellers, it is safe to eat canteen food. Roadside food can spoil our health. I am lucky to have such a good canteen in my school.

Teachers and other staff members are served by canteen boys in trays. They are served with some light refreshments, tea , coffee , soft drinks, etc. They eat it in their office and staffroom during lunch and short breaks. Even they enjoy canteen food wholehearted.

Many find our school canteen as a great advantage to both pupils and staff. However, a few PTA members do not think so. They think that school encourages students to spend money on eating outside food.

Our Principal Mrs. Karbhari is a truthful and straightforward woman. She always likes to put good new ideas into practice. Last month one of the parents in a PTA meeting suggested that there were good chances of improving the services provided by the school canteen. Since then many positive changes have been brought to the canteen.

The quality of the food has improved. It is served fresh and clean. Food is tastier than ever before. Special utensils are used to store food. The variety of food has increased. Most importantly, it is available at many affordable rates.

My school canteen is run by a staff of people who are well trained and dedicated to preparing food that suits best to the children. On every Thursday, each child gets a free banana from the canteen. Bottles of mineral water are also sold here. Most of the South Indian dishes and dry snacks are available in the canteen. I love to have mendu wada sambhar and plain dosa.

During recess, there is a great rush. However, students show discipline and are well-mannered. Specially appointed students from senior classes help in maintaining discipline in the canteen. There are few benches in the canteen where at least fifty to sixty students can sit at a time to have their lunch. Everything runs smoothly during recess.

Sometimes even teachers and other staff members are seen visiting the school canteen. They sit to have their tea, coffee, or some light snacks. Thus, for me canteen in my school must not be considered as a treat but a need because it fills our empty bellies and helps us in making our minds work during studies.

Set 1: Essay On My School Canteen

I study in Cambridge School which is one of the best schools of Mumbai. It has a stone building. It has all the facilities a good school should have well-furnished classrooms, laboratories, library and playgrounds.

As we enter the school, there is a playground to our left and a small garden to our right. When we enter the building, the principal’s room and the office room are to the left and the staff room to the right side. These are well-furnished. There are thirty-four classrooms. Our laboratories are well-equipped. Our library has books on almost all the subjects. Our librarian is also very nice and helps us choose good books.

Our school, like all schools, has a prescribed uniform. We have to wear white or cream cotton shirts, light blue trousers, black shoes and white socks. Girls have to wear white blouses and light-blue skirts in primary and middle classes and white shirts and light-grey skirts in higher classes. They have to tie their long hair with white ribbons.

In our school special attention is paid to behaviour, cleanliness and punctuality. The most well-behaved, neat and punctual student is awarded a prize at the Annual Day function.

Our principal is a strict disciplinarian. He takes the help of P.T. teachers too. If any student violates the rules, is not in uniform, or makes mischief, gets punished. But he is fair and loving. He tries to find out the reason and guides us.

Our teachers are also quite strict. They teach us with great care, check our notebooks and help us with our problems. But if we are inattentive and don’t work properly, we are punished.

I like my school very much and am proud that I belong to it.

- Essay On The Annual School Sports Day

- Essay On I Am A School Bag

- Essay On My School Peon

- Essay On My School Library

- Essay On My First Day in School

- Essay on My School

- Essay On My Favourite Book Mahabharata

- Essay On Teachers Day

- Essay on My Favourite Teacher

Please Share This Share this content

- Opens in a new window

You Might Also Like

Essay on gambling, essay on family planning, essay on pocket money, essay on my favourite player, essay on a visit to a historical place.

Essay On Horse

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Education Diary

- Advertising

- Privacy Policy

Class Notes NCERT Solutions for CBSE Students

English essay on our School Canteen for students & children

admin September 29, 2017 Essays in English 92,831 Views

Our school canteen is very well equipped. One can buy almost every kind of snack there, like samosas, chips, sandwiches, sweet, cakes etc. They are prepared in very hygienic surroundings by our school cook, and tables to sit on and eat, and ovens to keep the food warm. There is also a soda fountain which is Very popular among the older students.

All the students love to sit in the canteen and discuss the events of the day. The noise level is always very high in the canteen as everyone is shouting to make himself heard. There are notice boards and suggestion boxes which all students are freely. There is also a separate enclosure for teachers. The cook charges very reasonable rates from us.

I think that the school canteen is my favorite place in the school. I always enjoy myself there, and look forward to the recess when I can rush to the canteen with my friends.

- Stumbleupon

Tags Easy English Essays English Essays for 5 Class Students English Essays for 6 Class Students English Essays for 7 Class Students English Essays for 8 Class Students English Essays for CBSE Students English Essays for NCERT Students English Essays in Easy Language Essays for NCERT Syllabus Essays in English Language Popular English Essays for CBSE Students Short English Essays

Related Articles

English Essay on Drug Abuse: Long & Short Essays on Drug Abuse

Eid ul-Adha / Bakrid: 2 Long & Short English Essay for School Children

2 weeks ago

My Father My Hero: 5 Long and Short English Essays For Students

Environment Essay in English For Students and Children

4 weeks ago

English Essay on Bicycle: 500 Words Essay On Bicycle

English Essay on Smoking in 500 words for students

Veer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar: English Essay On Greatest Patriot Ever

Remembering the stupendous patriot and hard-core nationalist Veer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar Whenever a person from …

One comment

Very nice essay on “My neighbours”!

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

A Plus Topper

Improve your Grades

Essay on Our School Canteen | Our School Canteen Essay for Students and Children in English

February 7, 2024 by Prasanna

Essay on Our School Canteen – Given below is a Long and Short Essay on Our School Canteen of competitive exams, kids and students belonging to classes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. The Our School Canteen essay 100, 150, 200, 250, 300 words in English helps the students with their class assignments, comprehension tasks, and even for competitive examinations.

You can also find more Essay Writing articles on events, persons, sports, technology and many more.

Short Essay on Our School Canteen 300 Words for Kids and Students in English

All the corridors of the school should lead to the canteen but unfortunately, it is in a corner of the school. It has a small window through which the canteen incharge supplies us snacks, tea and cold drink. Our principal has allowed a stall of ice cream in the canteen. There are two other counters for books, stationery and beverages. It is mostly the parents who visit the stationery counter. The students go there only under compulsion. Their most favourite spot is the ice cream corner. The students flock round it and buy the ice creams that are available in different flavours.

Their mouths water at the sight of ice cream and they want to break the queue to have it first. The second favourite counter is that of beverages. They wash down their lunches with some cold drink or a cup of tea. They sip it slowly so that it could last for the whole period. As the bottle starts showing its bottom, their speed also decreases. They glup down the last drop with a heavy heart as if it was the end of their friendship with the bottle.

The third counter, to attract a small crowd, is the place where the students get snacks. Toffees and chocolates are in great demand. Some students buy patties, bread-pakoras, slices or cakes. Some teachers also make a beeline for this counter. Everyone is in a hurry. There is a rule of “first come, first serve” but the students do not follow it. They always hand over money to the students who are nearer the counter and ask them to purchase the snacks for them.

As the recess period is over, they leave their disneyland with a heavy heart. The students wend their way to the classrooms. One can see gloom writ large on their faces. They get ready to attend the last few periods. Canteen is indeed the most happening place of the school.

- Picture Dictionary

- English Speech

- English Slogans

- English Letter Writing

- English Essay Writing

- English Textbook Answers

- Types of Certificates

- ICSE Solutions

- Selina ICSE Solutions

- ML Aggarwal Solutions

- HSSLive Plus One

- HSSLive Plus Two

- Kerala SSLC

- Distance Education

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

The Importance of a Well-Equipped Canteen for Students Nourishment

Save to my list

Remove from my list

School Canteen Operators

The Importance of a Well-Equipped Canteen for Students Nourishment. (2016, Apr 30). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/school-canteen-essay

"The Importance of a Well-Equipped Canteen for Students Nourishment." StudyMoose , 30 Apr 2016, https://studymoose.com/school-canteen-essay

StudyMoose. (2016). The Importance of a Well-Equipped Canteen for Students Nourishment . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/school-canteen-essay [Accessed: 29 Jun. 2024]

"The Importance of a Well-Equipped Canteen for Students Nourishment." StudyMoose, Apr 30, 2016. Accessed June 29, 2024. https://studymoose.com/school-canteen-essay

"The Importance of a Well-Equipped Canteen for Students Nourishment," StudyMoose , 30-Apr-2016. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/school-canteen-essay. [Accessed: 29-Jun-2024]

StudyMoose. (2016). The Importance of a Well-Equipped Canteen for Students Nourishment . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/school-canteen-essay [Accessed: 29-Jun-2024]

- Life cannot be constant without adequate nourishment Man Pages: 9 (2586 words)

- Nourishment in Daily Life A nation morning supper called Pages: 2 (490 words)

- Root Issue of Nourishment Squander Pages: 2 (530 words)

- St. Peter's Abbey: Preserving a Kitchen Garden for Daily Nourishment. Pages: 3 (796 words)

- Food Handling Practices in Enrile Vocational High School's Canteen Pages: 16 (4751 words)

- Canteen hygiene in Eastern Visayas State University Pages: 5 (1369 words)

- Satisfaction On Food And Services At The School Canteen Pages: 5 (1257 words)

- Well Done is Better Than Well Said Pages: 3 (691 words)

- Why are Classroom Rules Important for Students' Well-Being Pages: 5 (1261 words)

- How Memes Affect The Psychological Well-being Of College Students Pages: 3 (624 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Public Health Nutrition

- > Volume 26 Issue 11

- > How healthy and affordable are foods and beverages...

Article contents

- Participants:

- Conclusion:

Financial support

Conflict of interest, ethics of human subject participation, supplementary material, how healthy and affordable are foods and beverages sold in school canteens a cross-sectional study comparing menus from victorian primary schools.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 July 2023

- Supplementary materials

Government policy guidance in Victoria, Australia, encourages schools to provide affordable, healthy foods in canteens. This study analysed the healthiness and price of items available in canteens in Victorian primary schools and associations with school characteristics.

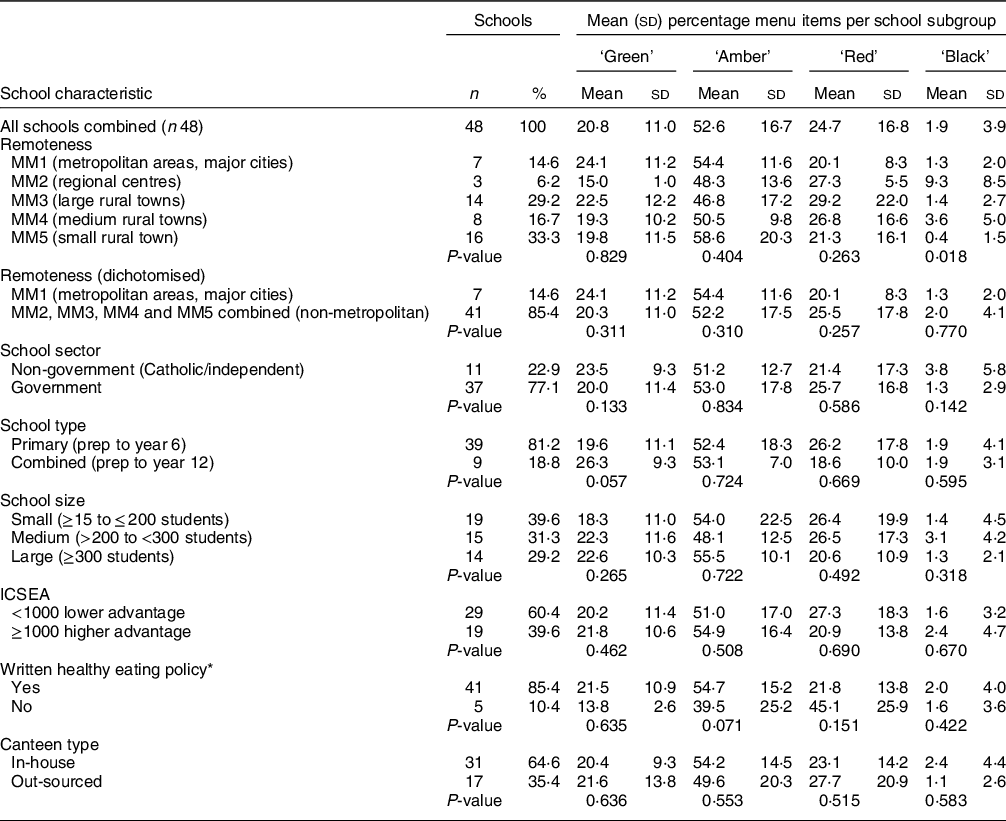

Dietitians classified menu items (main, snack and beverage) using the red, amber and green traffic light system defined in the Victorian government’s School Canteens and Other School Food Services Policy. This system also included a black category for confectionary and high sugar content soft drinks which should not be supplied. Descriptive statistics and regressions were used to analyse differences in the healthiness and price of main meals, snacks and beverages offered, according to school remoteness, sector (government and Catholic/independent) size, and socio-economic position.

State of Victoria, Australia

A convenience sample of canteen menus drawn from three previous obesity prevention studies in forty-eight primary schools between 2016 and 2019.

On average, school canteen menus were 21 % ‘green’ (most healthy – everyday), 53 % ‘amber’ (select carefully), 25 % ‘red’ (occasional) and 2 % ‘black’ (banned) items, demonstrating low adherence with government guidelines. ‘Black’ items were more common in schools in regional population centres. ‘Red’ main meal items were cheaper than ‘green’% (mean difference –$0·48 (95 % CI –0·85, –0·10)) and ‘amber’ –$0·91 (–1·27, –0·57)) main meal items. In about 50 % of schools, the mean price of ‘red’ main meal, beverages and snack items were cheaper than ‘green’ items, or no ‘green’ alternative items were offered.

In this sample of Victorian canteen menus, there was no evidence of associations of healthiness and pricing by school characteristics except for regional centres having the highest proportion of ‘black’ (banned) items compared with all other remoteness categories examined. There was low adherence with state canteen menu guidelines. Many schools offered a high proportion of ‘red’ food options and ‘black’ (banned) options, particularly in regional centres. Unhealthier options were cheaper than healthy options. More needs to be done to bring Victorian primary school canteen menus in line with guidelines.

Schools are an important setting for establishing healthy dietary patterns and reducing risks of chronic disease like childhood overweight and obesity ( Reference Peterson and Fox 1 , Reference Driessen, Cameron and Thornton 2 ) . Unlike the USA, the UK and Japan where food is routinely provided for students at school, in Australia, food is typically prepared at home and taken to school or alternatively purchased from a school-based canteen or ‘lunch order’ system whereby parents can place orders for food which is either prepared by the canteen itself or from an offsite food provision service. Access to canteens and lunch orders is determined individually by the school and can range from access once or twice a week to every day. Historically, school canteens or lunch orders have offered a high proportion of energy-dense and less healthy foods such as pastries, cakes and sugar-sweetened beverages ( Reference Bell and Swinburn 3 , Reference Bell and Swinburn 4 ) , even though it is recognised that school food is important for health messaging and education ( Reference Bell and Swinburn 4 ) . Further, energy consumed from discretionary foods obtained at school, along with frequency of purchasing lunch at school canteens, has been associated with overweight and obesity ( Reference Masse, de Niet-Fitzgerald and Watts 5 , Reference Hardy, Foley and Partridge 6 ) . The system of food provision in Australian schools has meant that health promotion efforts have focused both on parent and caregiver education and on policies designed to influence the availability and affordability of foods and beverages provided by school canteens.

Schools are a key setting for action in Australia’s recent National Obesity Strategy ( 7 ) . However to date, the presence of school nutrition policy has not necessarily translated to a healthy canteen ( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Breheny and Jones 8 ) . Australia’s states and territories, which have responsibility for the education system, have progressively introduced policy guidelines for school food provision since 2005 ( 9 ) . The Victorian state government’s Department of Education and Training first released a food service policy for schools in 2006, with guidelines on the provision of healthy food and drink underpinned by the Australian Dietary Guidelines ( 10 ) . Following this, the School Confectionary Guidelines were instituted in 2009 ( 11 ) , and more recently, in June 2020, the policy name was simplified to ‘Canteens, Healthy Eating and Other Food Services’ policy with no change to policy content ( 12 ) . The policy uses a ‘traffic light’ classification system to guide food provision, with the availability, promotion, competitive pricing, and display of ‘Everyday’ food and drinks (‘green’ classification) encouraged (12) . ‘Green’ menu items should make up the majority (> 50 %) of available items. ‘Select Carefully’ (‘amber’ classification) food and drinks should be restricted and make up less than half of the canteen menu, while ‘Occasionally’ food and drink (‘red’ classification) should not be included on the regular menu (12) . Banned items on the policy include high sugar content drinks and confectionary (‘black’ classification) (12) . It is important to note that these guidelines are not mandated in government or other types of schools (e.g. Catholic/independent), nor formally monitored; however, schools are strongly encouraged to support a whole-school approach to health eating ( 12 ) .

Historically, studies have found poor adherence to school food policy, both Australia-wide ( Reference Haynes, Morley and Dixon 13 , Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) and in Victoria specifically ( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Breheny and Jones 8 , Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 ) . For example, an analysis of 106 school canteens in 2008 and 2009 found that on average only 20 % of items on the menus were ‘green’ ( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Breheny and Jones 8 ) . Furthermore, a recent analysis of healthy v . less healthy menu food options in school canteens revealed that less healthy food options were significantly cheaper ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) , though this study did not include drinks. A national analysis of school canteens Reference Haynes, Morley and Dixon found similar findings (albeit in secondary schools), with healthier items significantly more expensive than less healthy, and almost all schools offering red items contrary to advice provided in region-specific policies and guidelines (13) . Drink choices were dominated by red and amber options ( Reference Haynes, Morley and Dixon 13 ) . A recent cross-sectional study found that 38 % of schools reported that they had a healthy canteen policy, indicating interest from schools to adopt healthy practices ( Reference Alston, Crooks and Strugnell 16 ) . However, the implementation of that policy and whether it translated to healthier canteens was not evaluated ( Reference Alston, Crooks and Strugnell 16 ) .

Diet-related chronic disease is higher in rural Australia compared with urban counterparts, and improving the healthiness of diet is a key priority ( Reference Alston, Jacobs and Allender 17 ) . Furthermore, higher rates of childhood obesity (a key risk factor for chronic diseases) in Victorian regional areas have also been reported (32 % of girls and 29 % boys outside of major cities ( Reference Crooks, Strugnell and Bell 18 ) compared with national average of about 25 % ( 19 ) . Therefore, it is important to explore differences in the healthiness of canteen menus by remoteness. Some previous studies have not analysed healthiness of canteen menus by school characteristics such as level of disadvantage or geographic location ( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Breheny and Jones 8 , Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 , Reference Wyse, Wiggers and Delaney 20 , Reference Clinton-McHarg, Janssen and Delaney 21 ) . Other studies have analysed, with mixed findings. A cross-sectional study in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, revealed an association with schools classified as high socio-economic status having higher canteen usage compared with schools classified as low socio-economic status ( Reference Finch, Sutherland and Harrison 22 ) . A cross-sectional study in NSW revealed no difference in nutrition by school location and level of disadvantage ( Reference Delaney, Sutherland and Wyse 23 ) , while a study in NSW revealed some variations in the availability of healthy foods and pricing and promotional strategies by school characteristics, for example, a higher proportion of schools in high socio-economic areas had healthier menu options ( Reference Yoong, Nathan and Wyse 24 ) . Another national Australian cross-sectional study revealed an increase in proportion of schools selling less healthy snacks cheaper than healthy snacks as level of disadvantage increased ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) . These studies only focused on government schools ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 , Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 , Reference Delaney, Sutherland and Wyse 23 ) , were largely focused on NSW ( Reference Wyse, Wiggers and Delaney 20 , Reference Delaney, Sutherland and Wyse 23 – Reference Delaney, Wyse and Yoong 28 ) and did not include a price analysis on beverages ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 , Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 ) or the presence of a healthy eating policy within the school. Moreover, as food affordability is a major determinant of the healthiness of dietary choices, it is important to determine whether school food environments support healthy choices for those with higher levels of socio-economic disadvantage (who tend to be more price sensitive) ( Reference Zorbas, Palermo and Chung 29 ) . There is a need for studies to more comprehensively assess the factors associated with health-promoting pricing strategies in order to generalise findings more readily to a range of contexts.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to:

1) Analyse the healthiness and price of items offered by Victorian primary school canteens across various school characteristics and levels of remoteness;

2) Examine adherence to Victorian state government guidelines for provision of food and drinks in primary school canteens

Study design and participants

The data used in this study were from cross-sectional analyses of a convenience sample of canteen menus that were collected from primary (elementary) schools participating in three studies: the Whole of Systems Trial of Prevention Strategies for Childhood Obesity (WHO STOPS ( Reference Allender, Millar and Hovmand 30 ) ) in 2017 ( n 16; original study had an overall 69 % school participation rate, of which 30 % schools with menus collected in Autumn/Winter are included in this current analysis); Goulburn Valley Health Behaviours Monitoring Study in 2016 ( n 9; original study had an overall 63 % school participation rate, of which 23 % with menus collected in Autumn/Winter are included in this current analysis) ( Reference Hoare, Crooks and Hayward 31 ) and Healthy Together Victoria and Childhood Obesity Study from 2016 to 2019 ( n 23; original study had an overall 33 % school participation rate, of which 50 % schools with menus collected in Winter/Spring are included in this current analysis) ( Reference Strugnell, Millar and Churchill 32 ) . Methods for the three studies have been previously described in detail ( Reference Allender, Millar and Hovmand 30 – Reference Strugnell, Millar and Churchill 32 ) . For the Goulburn Valley Health Behaviours Monitoring Study and WHO STOPS, all primary schools in the nine local government areas were invited to participate. For the Healthy Together Victoria and Childhood Obesity Study, a strategic random sampling technique with replacement was used to invite three primary schools within twenty-six local government areas spread across metropolitan and regional Victoria. WHO STOPS ( Reference Allender, Millar and Hovmand 30 ) and Healthy Together Victoria and Childhood Obesity Study ( Reference Strugnell, Millar and Churchill 32 ) were both childhood obesity prevention studies, focused on building community capacity to implement intervention strategies most relevant to their community context (i.e. community resources and capacity) to promote healthy eating and physical activity across a diverse range of settings. The Goulburn Valley Health Behaviours Monitoring Study was a census-style observational study aiming to understand rates of overweight/obesity, associations with health behaviours (e.g. diet and physical activity) and health-related quality of life ( Reference Hoare, Crooks and Hayward 31 ) . Upon receiving verbal consent from the school principal to participate in the study, written information packs were mailed to the school and during school visits the school canteen menus were collected (hard copy). The presence or absence of school policies on healthy eating were also collected as dichotomous yes/no as part of the data collection and were completed by the school principals or their nominees. Note that the canteen menus examined in this study were collected from comparison sites without active intervention.

Measures and data management

School characteristics and level of remoteness.

For each school, collected characteristics included remoteness, sector (government or Catholic/independent), type (prep to year 6 (i.e. aged 5–12 years) or combined prep to year 12 (i.e. aged 5–18 years)), size, and socio-economic status. School characteristic data were collected from the publicly available MySchool database ( 33 ) , matched to the year of data collection (e.g. if menu was collected in 2016, then 2016 school characteristics were used).

Remoteness of the school were classified according to the Modified Monash Model ( 34 ) . The Modified Monash Model was developed based on the Australian Statistical Geography Standard and uses population numbers and road distance to classify areas into remoteness categories on a scale of MM1 to MM7, where 1 represents metropolitan locations and 7 represents very remote communities ( 34 ) . Classifications for each school were obtained from the publicly available ‘locator’ database provided by the Australian Department of Health ( 35 ) and using school postcode.

School type was categorised into two groups for the purpose of this study: government schools and Catholic/independent schools. Whilst all Victorian schools regardless of whether they are government, Catholic or independent operate under legislative and regulatory requirements (e.g. Education and Training Reform Act 2006 ( 36 ) and Education and Training Reform Regulations 2017 ( 37 , 38 ) ), Catholic and independent schools are not part of the government system, with their own enrolment, costs, and policies ( 39 ) , and are not required to adhere to this state guideline ( Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 ) . Therefore, the school type was dichotomised to reflect any potential differences type of schools might have in adhering to the state government canteens, health eating and other food services policy ( 12 ) . School size classification was defined as per the Australian Education Act ( 40 ) : small schools (≥ 15–≤ 200 students), medium schools (> 200 to < 300 students) and large schools (≥ 300 students). The Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) ( 41 ) is constructed from student characteristics (parents’ occupation and education level), the location of the school, and the proportion of Indigenous students and is designed to rank schools according to their level of socio-educational advantage. Given the average ICSEA across Australian schools is 1000, ICSEA scores were dichotomised into < 1000 or ≥ 1000, where < 1000 represents schools with lower socio-educational advantage (i.e. higher levels of disadvantage) and ≥ 1000 represents schools with higher socio-educational advantage (i.e. lower levels of disadvantage) ( 41 ) .

Menu assessment

Menu analysis was undertaken by two dietitians (AH and LA). AH undertook 100 % of the assessment with a 10 % subset analysed independently by LA to cross-check and confirm classifications (with 100 % agreement achieved). Each individual menu item was classified as ‘green’, ‘amber’, ‘red’ or ‘black’ based on its nutritional content, using the traffic light system defined in the Victorian government’s school operations policy ‘Canteens, Healthy Eating and Other Food Services’ ( 12 ) . Examples of each classification are provided below but are not exhaustive. Examples of ‘green’ items included chicken and salad sandwich, pumpkin soup, fruit, low-fat yogurt and water. Examples of ‘amber’ items included Vegemite sandwich, ham and cheese sandwich, lasagne, popcorn, and 100 % fruit juice. Examples of ‘red’ items included meat savoury pie, hot chips (fries), salami and cheese sandwich, donut, and fruit drinks (< 100 % fruit juice). Examples of ‘black’ items included chocolate chip biscuits (cookies), confectionary, and chocolate mud cake. Traffic light classification was entered into an excel spreadsheet and exported to STATA version 15 (StataCorp) ( 42 ) for analysis. The menu analysis was undertaken with the assistance of FoodChecker software provided free by the Victorian government’s Healthy Eating Advisory Service (HEAS, supported by the Victorian Division of Nutrition Australia) ( 43 ) which assesses menu items against the Canteens, Healthy Eating and Other Food Services policy using the traffic light classification ( 12 ) . FoodChecker has a comprehensive database of products (branded, pre-made foods and drinks). A list of assumptions made during canteen menu analysis can be found in online supplementary material, Supplemental File 1 . For food items not listed on FoodChecker, a similar item available on the database was used, or if the coding dietitian deemed that no item of close similarity was available, the item was added as a product. To do this, the dietitian located the product’s nutrition information panel online and added it to FoodChecker as a product or receipt (two occasions). Items were also classified into three categories: main, that is, items served as a main meal (e.g. sandwich, wrap, meat pie, herein referred to as main items), snack or beverage.

Food item grouping for pricing analysis

The price of individual menu items was extracted from the canteen menus to enable a detailed price analysis. There were no missing price data. The price analysis was undertaken by MB in STATA version 15 (StataCorp) ( 42 ) . Small hot food items such as party-pies, sausage rolls and dim sims were classified as ‘snacks’ when sold individually, or as a ‘main’ when sold in multiples of 2 or more. Food items which are unlikely to be purchased on their own, for example, sauces or optional additional sandwich toppings, were excluded from the analysis.

‘Black’ items were grouped with ‘red’ items for the purposes of price analysis. Prices of the lowest priced ‘red/black’, ‘amber’ and ‘green’ items in each menu category (main, snack and beverage) were identified. Canteens without ‘red’ items in a menu category were classified as selling their ‘green’ items cheaper in that category ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) . Those canteens without ‘green’ items were classified as selling ‘red’ alternatives cheaper.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests were used to determine differences in the proportion of items available for purchase in each traffic light category by remoteness, sector, type, size and ICSEA with P < 0·05 considered a statistically significant difference. The most common ‘red’ and ‘black’ items was tabulated by ordering the highest proportion of items by each discretionary/banned food category. To examine adherence to Victorian state government guidelines for food and drink provision in primary school canteens, menu items were first tabulated by individual school into the relevant ‘green’, ‘amber’, ‘red’ and ‘black’ categories. Schools were then assessed against the School Canteens and Other School Food Services Policy which states ‘green’ items to represent > 50 % of the menu, ‘amber’ to represent < 50 % of the menu, and ‘red’ items should not be regularly available (e.g. available no more than two occasions per term) and ‘black’ items should not be supplied at any time ( 12 ) .

For the pricing analysis, the prices of the cheapest ‘green’, ‘amber’ and ‘red’ items in each menu category were compared using univariate linear regression to determine the mean (95 % CI) price and price difference between ‘red’ and ‘green’ alternatives. A series of univariate linear regressions were conducted for each menu category to determine the differences in price by traffic light classification. Normality of price residuals was tested using hettest command in Stata. Multi-variable analysis was not utilised to reduce the risk of a type 1 error. Note that the pricing analysis was conducted to compare items with the cheapest menu item, rather than the mean price of the menu item, as per previous methodology and the likelihood that the cheapest menu item would be the most affordable comparison for students ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) . Prices ($) are reported in AUD. P -values < 0·05 were considered significant.

Main items were further examined using exploratory univariate linear regression analysis to test whether price of cheapest main item varied by school characteristics including: size of school (small, medium and large), ICSEA score (ICSEA < 1000; ≥ 1000), school sector (government and non-government (Catholic/independent)), remoteness (MM1 (metropolitan), MM2, MM3, MM4 and MM5 (most remote in this context)) and presence of school healthy eating policy (yes and no). Multivariate linear regressions were used to explore the association between school characteristics and price and traffic light classification of menu items. An interaction term between traffic light classification and school characteristics was included in these models to explore whether the variation in the price for each traffic light category was related to school characteristic level. Due to the presence of exploratory interaction terms, P -values < 0·01 were considered significant to reduce the risk of type I error ( Reference Gibson 44 ) .

Sensitivity analysis

To compare results of this study to the most relevant previous study of school food prices in Australia by Billich et al. ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) , a sensitivity analysis was conducted. The analyses were repeated using collapsed healthiness classifications in which product traffic light classifications were grouped into ‘healthier’ (‘green’) and ‘less healthy’ (‘amber’, ‘red’ and ‘black’) items.

School characteristics

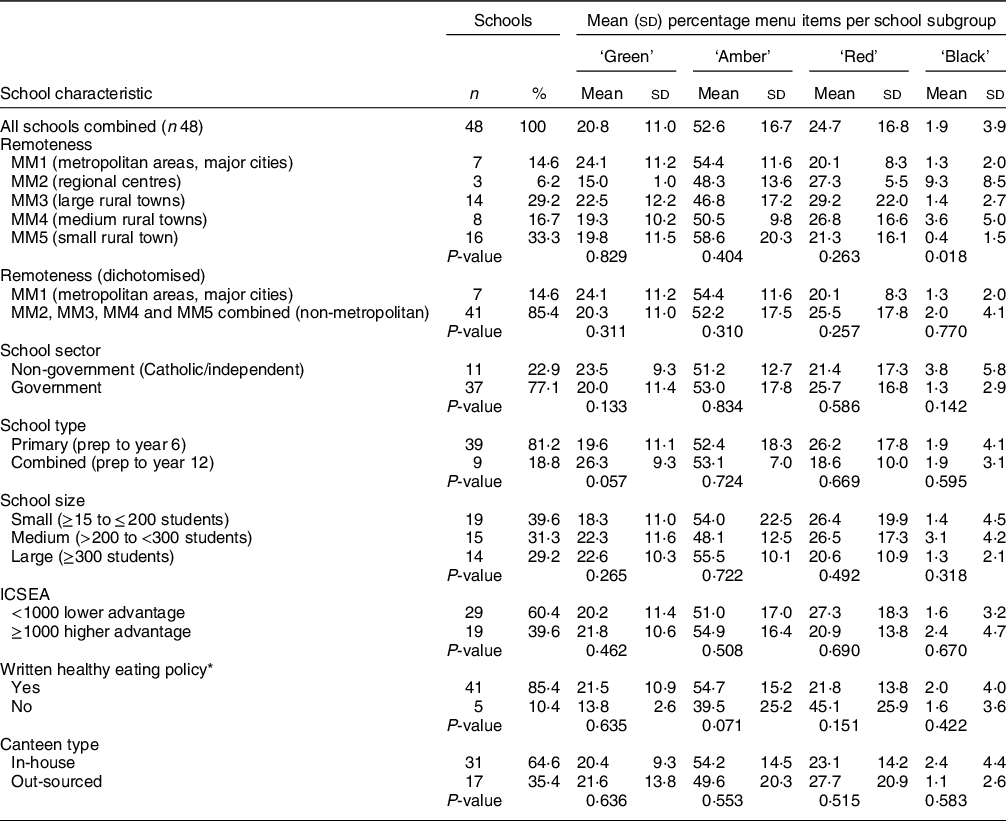

The characteristics of participating schools are presented in Table 1 . Forty-eight schools provided canteen menus offering a total of 1818 individual menu items for sale, an average of thirty-eight items per school. The estimated total enrolments was 16 146 students (prep to year 6), and the majority of schools that provided menus were government (77 %) and prep to year 6 (81 %) schools, with a relatively even representation of small, medium and large schools. The majority of schools were situated in small rural towns (MM5), and none of the schools in this sample were classified as remote or very remote communities (MM6–MM7). Most (60 %) of the schools were in communities with lower than average socio-educational advantage (ICSEA < 1000). Most schools (89 %) reported that they did have a healthy eating policy in place, and the canteen food was prepared on site in two-thirds of schools (65 %) rather than out-sourced to an external provider.

Table 1 School characteristics and proportion (%) of ‘green’, ‘amber’, ‘red’ and ‘black’ menu items ( n 48 canteen menus)

MM, Modified Monash Model; ICSEA, Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage.

* Data missing for two schools; in-house – canteen on school site; out-sourced – external food retail setting provided food. P -value from χ 2 test. MM was used to classify remoteness ( 34 ) ; ICSEA ( 41 ) : lower socio-educational advantage (i.e. higher levels of disadvantage) and higher socio-educational advantage (i.e. lower levels of disadvantage).

Menu analysis

The percentage contribution of each traffic light category to individual school’s menu was calculated (e.g. number of items from green traffic light category/total number of items offered per school) in order to provide a comparison to national guidelines. The mean percentage contribution was then calculated for the overall sample of forty-eight schools. In this sample of forty-eight schools, canteen menus comprised of 21 % ‘green’, 53 % ‘amber’, 25 % ‘red’ and 2 % ‘black’ items (Table 1 ). There were no statistically significant differences in food offerings by ‘green’, ‘amber’, ‘red’ or ‘black’ classification by school sector, school size, ICSEA, presence of a policy or type of school canteen. Whilst the proportion of ‘red’, ‘amber’ and ‘green’ foods offered was similar by remoteness, there was a significant difference in the proportion of ‘black’ items by remoteness ( P = 0·018). Schools classified as ‘regional centres’ (MM2) had the highest proportion of ‘black’ classified items (9·3 % MM2 v . range of 1–4 % for all other remoteness categories).

Healthiness of items within food categories (meal, snack and beverage)

Of the forty-eight canteen menus, all (100 %) offered mains, forty-five (94 %) offered beverages and forty (83 %) offered snacks. The 1818 menu items were classified into three food categories: meal items ( n 1101), snack items ( n 403) and drinks ( n 314). ‘Green’ classified foods made up 16 % of main meal items ( n 177), 22 % of snack items ( n 87) and 45 % of drink items ( n 141). ‘Amber’ classified foods dominated main (66 %, n 725) and snack (42 %, n 168) items. ‘Red’ items made up approximately one-fifth of main (18 %, n 198), one-quarter of snack (28 %, n 113) and one-third of drink (33 %, n 104) items. ‘Black’ items were most frequent in snacks (9 %, n 35). Data not shown.

In addition to examining the overall frequency (n) of green, amber, red and black items, the percentage contribution of each traffic light category for each food category (main meals, snacks and drinks) was calculated for each individual school (e.g. number of snack items from green traffic light category/total number of snack items offered per school). These results were collated to provide a mean percentage contribution representative of all schools included in the study sample.

Examination of food type (main, snack and beverage) by traffic light categories was conducted. When examining main meal items, on average 14 % were ‘green’, 64 % ‘amber’ and 22 % ‘red’. Of the forty schools that offered snack foods, 22 % were green, 39 % were amber, 32 % were red and 8 % were black. For the forty-five schools that offered drinks, 48 % were green, 19 % were amber and 33 % were red (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1 ).

Examination of ‘red’ and ‘black’ items

Overall, 94 % of canteen menus (forty-five) included at least one ‘red’ or ‘black’ item regularly available. One-third of schools (33 %, sixteen schools) included banned (‘black’) items (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2 ).

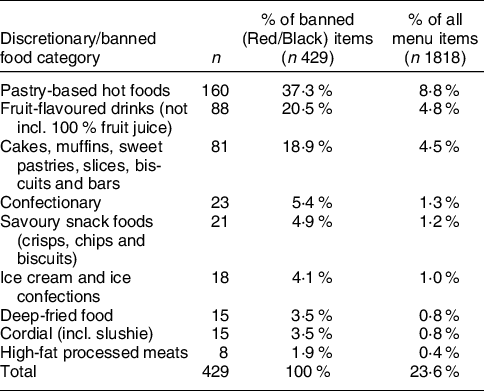

The ten most common food categories were selected for an analysis of the discretionary (‘red’ or ‘black’ classification) foods offered (Table 2 ). Of the 451 red or black menu items offered in the menus examined, 429 (95 %) fell into one of these ten categories. The top three most common discretionary food categories were pastry-based hot foods (37 %, e.g. pie and sausage roll), fruit-flavoured drinks (20·5 %, not including 100 % fruit juice) and cakes, muffins, sweet pastries, slices, biscuits, and bars (18·9 %).

Table 2 Frequency of most common ‘red’ and ‘black’ items ( n 48 canteen menus)

No schools provided soft drink (sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages) for purchase.

Adherence to government canteen guidelines

None of the schools in this sample met the guideline of ‘everyday’ (‘green’) menu items making up the majority (more than 50 %) of the menu. Only three schools (6 %) schools met the ‘occasionally’ ‘red’ item guideline (no ‘red’ items regularly available, no ‘black’ items).

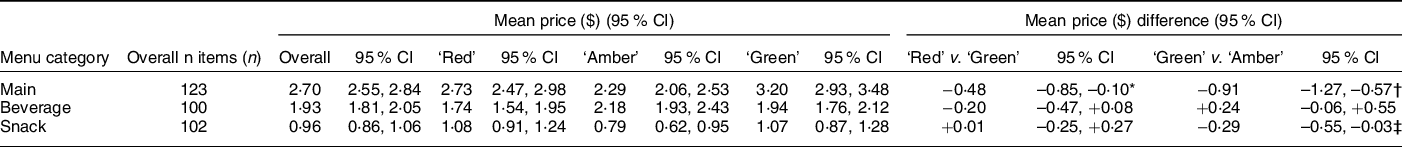

Pricing analysis

Overall, the mean prices of all items sold in each menu category were main $3·82 (95 % CI 3·75, 3·90), beverages $2·16 (2·09, 2·23) and snacks $1·45 (1·39, 1·52) (data not shown). The mean prices of cheapest items per menu category were main $2·70 (2·55, 2·84), beverage $1·93 (1·81, 2·05) and snack $0·96 (0·86, 1·06) (Table 3 ). The lowest priced ‘red’ items were cheaper than the lowest priced ‘green’ items in main, beverage and snack categories (Table 3).

Table 3 Univariate regressions comparing price of cheapest item per food category by traffic light classification ( n 48 canteen menus)

* P = 0·013.

† P < 0·001.

‡ P = 0·031.

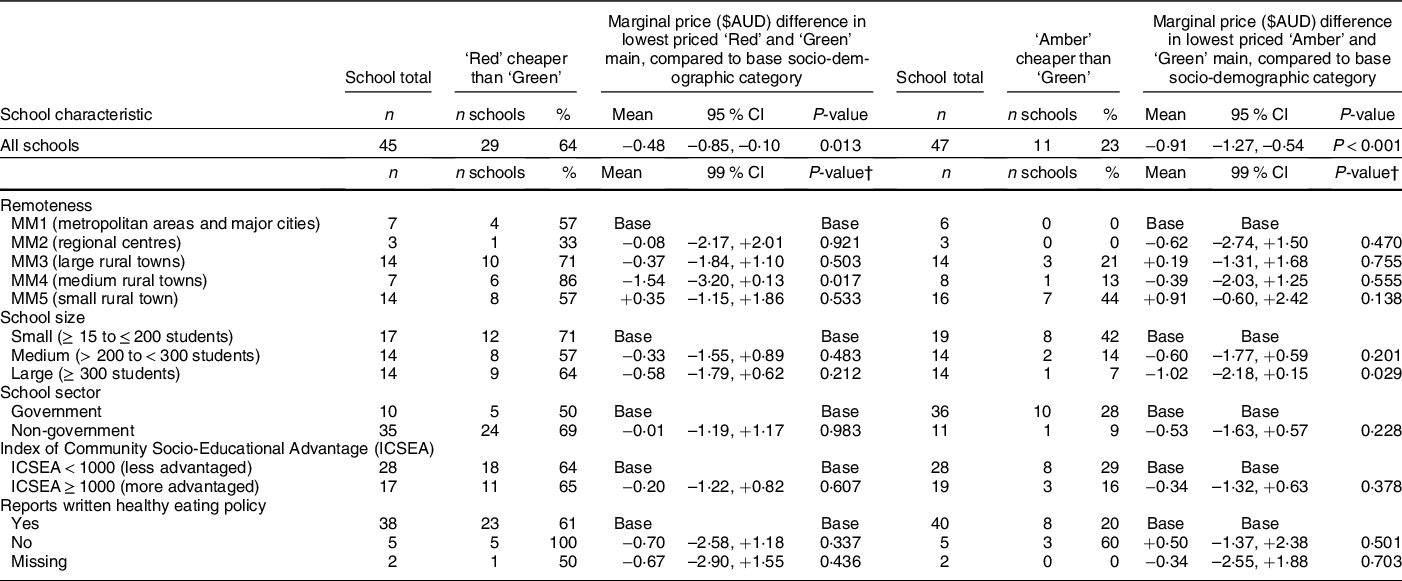

Of the forty-eight schools offering mains, twenty-nine (60 %) schools offered ‘red’ mains cheaper or offered no ‘green’ mains (Table 4). Three (6 %) schools sold ‘amber’ mains only and sixteen (33 %) schools sold the lowest priced ‘green’ main item cheaper (e.g. salad) or offered no ‘red’ main items (data not shown). In all scenarios, ‘red’ item mains were cheaper than the average ‘green’ item main, when looking at lowest cost items. When looking at lowest cost items, ‘red’ mains were cheaper than ‘green’ mains (mean difference –$0·48 (95 % CI –0·85, –0·10)). Similarly, ‘amber’ mains were cheaper than green mains (–$0·91 (–1·27, –0·57)) (Table 3 ).

Of the forty-five schools offering beverages, twenty-two (49 %) schools sold ‘red’ beverages cheaper than ‘green’ or offered no ‘green’ beverages. Twenty-three (51 %) schools sold ‘green’ beverages cheaper than ‘red’ or offered no ‘red’ beverages, when looking at lowest cost items in each category (data not shown). No other differences were found in the mean price of the cheapest items between ‘red’ and ‘green’, or ‘amber’ and ‘green’ beverage items (Table 3).

Of the schools offering snacks, twenty-six (57 %) schools sold ‘red’ snacks cheaper or offered no ‘green’ snacks and four (9 %) schools sold ‘amber’ snacks only. Sixteen (35 %) schools sold ‘green’ snacks cheaper than ‘red’ or offered no ‘red’ snacks, when looking at lowest cost items (data not shown). ‘Green’ snacks were cheaper than the cheapest ‘amber’ snacks (mean difference –$0·29 (–0·55, –0·03) (Table 3). No other differences were found in the price of the cheapest items between ‘red’ and ‘green’, or ‘amber’ and ‘green’ snack items (Table 3).

Analysis of prices by school characteristics

Unadjusted results showed no clear pattern for association of school characteristics with whether ‘red’ main items were priced cheaper than ‘green’ except for the presence of healthy eating policy (Table 4 ). There were no significant differences found in price of cheapest main item by school characteristic (remoteness, school size, school sector, socio-economic advantage or reports written healthy eating policy) (data not shown). No differences were found when adjusting for traffic light classifications or when examined for interactions between school characteristic and traffic light classifications (all P > 0·01).

Table 4 Unadjusted comparison of the mean price difference between the price of the lowest priced ‘red’ or ‘amber’ main item and ‘green’ main item, by school characteristics ( n 45 schools) *

* Only 45/48 schools sold ‘red’ and/or ‘green’ main menu items. Three schools sold only ‘amber’ mains.

† P -value of interaction between school characteristic and traffic light classification, compared to base category.

Results were similar in the sensitivity analysis when comparing prices of ‘less healthy’ to ‘healthier’ items. ‘Less healthy’ items (‘amber’, ‘red’ and ‘black’ combined) were cheaper than the cheapest ‘healthier’ mains (mean difference –$1·07 (95 % CI –1·42, –0·72)) and snacks (–$0·31 (–0·56, –0·05)). No significant associations were found between menu category prices, or traffic light category, and school characteristics. Data not shown.

This study explored canteen menus in a sample of Victorian schools offering canteen services to primary school-aged children. This study has extended previous canteen analyses to Catholic/independent primary schools, analysed both food (main and snack) and beverage offerings, and examined associations not only with school characteristics such as geographic location and level of disadvantage but also the presence of a written school healthy eating policy. None of the menus analysed were fully compliant with Victorian government guidelines. Unhealthy items dominated school menus, with nine in ten schools providing ‘red’ items and one in six providing ‘black’ food items. In half of schools, ‘red’ mains, beverage and snacks were cheaper than ‘green’ items or offered no ‘green’ snacks. In this sample of canteen menus, there were no clear associations of healthiness and pricing by school characteristics except for regional centres having the highest proportion of ‘black’ items compared with all other remoteness categories examined.

Healthiness of items offered

The current study was consistent with previous Australian studies showing that school canteen menus had poor adherence to state government guidelines ( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Breheny and Jones 8 , Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 , Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 ) . Whilst the Victorian state government’s Department of Health provides electronic resources and training opportunities for schools ( 43 ) , it appears there has been little improvement in the healthiness of school canteens since an initial audit was conducted in 2008–2009 ( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Breheny and Jones 8 ) . Similar to the current study findings of 33 % menus containing black items, the 2008–2009 audit reported 37 % of 106 menus audited to contain a banned item (confectionary and high sugar drinks) and none met traffic light recommendations ( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Breheny and Jones 8 ) . In 2012, analysis of fifty-one Victorian school canteen menus found that whilst 3 % of menus consisted of red items, only 16 % were compliant with state guidelines ( Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 ) . Unhealthy food offerings are also common in secondary schools with a recent national study revealing 98·5 % of 244 menus were found to contain one or more ‘red’ items and consequently did not meet canteen guidelines ( Reference Haynes, Morley and Dixon 13 ) .

Since 2008–2009, when an initial audit was conducted ( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Breheny and Jones 8 ) (note a different sample to the current study), there has been little change in the policy and programme environment to support schools to implement healthy canteen changes. Healthy canteen resources already existed ( 9 , 11 , 12 ) , as did a free healthy eating and physical activity programme for Victorian children attending primacy schools called ‘Kids – Go For Your Life’ ( Reference Honisett, Woolcock and Porter 45 , Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Prosser and Carpenter 46 ) . This programme evolved into today’s Achievement Program around 2012 ( 47 ) and still exists today.

One key additional resource developed during this period in 2017 was the free web-based menu planning tool delivered FoodChecker ( 43 ) . Despite the ability to easily check canteen menu items in this online platform, and with free support from HEAS, the healthiness of school canteens did not significantly improve.

Overall, the snacks category had the largest proportion of ‘black’ classified items (7·7 %), particularly in non-government schools (15·4 %). This was not surprising given that canteen guidelines are not mandated in non-government schools in Victoria. The most common red/black food items in this sample of schools included pastry-based hot foods, fruit-flavoured drinks (not including 100 % fruit juice), and cakes, muffins, sweet pastries, slices, biscuits and bars. In order to comply with guidelines and offer more healthy menus for students, canteens and offsite food provision services would need to remove the banned items and replace the ‘red’ ones with healthier alternatives, ideally selected in partnership with students themselves. Many major school suppliers now offer healthier versions of traditionally ‘red’ foods, such as lower fat and lower sodium meat pies, which can be classified as ‘amber’. Resources such as the Victorian Healthy Eating Advisory Service ( 48 ) and the Healthy Kids Association ( 49 ) provided school stakeholders (e.g. school staff, canteen managers and staff, food suppliers) a suite of resources including menu planning and promotion ideas, training and case studies to facilitate identification of healthier options.

Approximately half of schools in this study sold ‘red’ mains, beverage and snacks cheaper or offered no ‘green’ snacks. This study found a similar price difference between ‘less healthy’ and ‘healthy’ mains (–$1·07) as in Billich et al. (–$1·00), who examined 100 primary and 100 secondary school canteen menus across Australia ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) . However, the current study found a smaller price difference between ‘less healthy’ and ‘healthy’ snacks (–$0·31) compared to Billich et al. (–$0·70) ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) . Similarly, a study by Wyse et al in 2013 of NSW primary school canteen menus found that healthier ‘main meals’ were more expensive than less healthy mains; however, less healthy items ‘drinks’, ‘snacks’ and ‘frozen snacks’ were more expensive than healthier alternatives ( Reference Wyse, Wiggers and Delaney 20 ) . Prices could certainly influence unhealthy choices if consumers are presented with cheaper and unhealthier options which save third to a fifth of the price as presented in the current study (i.e. -0·48c cheaper to buy a red compared to green main, and -0·91c cheaper to buy an amber compared to green main). Prices are known to influence choice, and increased prices for healthier food items is a missed opportunity to incentivise their purchase by children and parents ( Reference Wyse, Wiggers and Delaney 20 ) . Making the healthier option the easiest one for children and parents ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) by pricing them accordingly is crucial.

Association with school socio-demographic characteristics

In this sample of Victorian schools, there was no evidence to support associations between healthiness of menu items or pricing and school characteristics, except for regional centres (MM2) having a higher proportion of ‘black’ items. This finding is in contrast to a previous finding in NSW that higher nutritional quality canteen menus were associated with larger school sizes and in areas of high socio-economic advantage ( Reference Yoong, Nathan and Wyse 24 ) , or a higher odds of having red items on the menu if schools were small, non-government, rurally based ( Reference Hills, Nathan and Robinson 50 ) . In addition to state differences, the findings may also differ between the two studies due to varying measures of socio-economic status (socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA) ( Reference Bureau 51 ) v . ICSEA) and remoteness (Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia ( 52 ) v . Modified Monash Model), categorisation of school size, and differing sample size. There is an opportunity to improve the food environment, through healthier canteen menus, and subsequently the child’s diet to reduce long-term health inequities ( 53 ) with mandated and monitored guidelines for all schools.

Implications for public health

This study showed that Victorian canteen menus do not meet healthy guidelines and therefore are not providing environments which encourage healthy diets. Optimising adherence to existing policy in Victoria remains an urgent priority. Government needs to invest in strengthening enforcement of the guidelines to support schools better with healthy food provision (i.e. mandatory guidelines). Adherence of guidelines could be supported by a canteen menu monitoring system (e.g. identify low compliance, increase policy adoption, implementation and impact, and research enablers to compliance) ( Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 , Reference Jilcott, Ammerman and Sommers 54 ) . These opportunities for action, in combination with other strategies, such as nudging – that is, small subtle changes to the physical and social environment to shift student food selection towards healthier options ( 55 , Reference Marcano-Olivier, Horne and Viktor 56 ) , is vital for healthier dietary outcomes in students. Given the large proportion of time children spend at school, the current study findings and recommendations are relevant to all high-income Western countries that have school canteens on site offering food and beverages for purchase.

There has been a recent launch (January 2022) of the Victorian state-wide Vic Kids Eat Well initiative, a movement supported by the Victorian government and delivered by the Cancer Council Victoria and Nutrition Australia ( 57 ) . Vic Kids Eat Well focuses on transforming the food and drink environment for children with schools as a key setting ( 57 ) . In NSW, local-level implementation support has been found to improve adherence to government school nutrition guidelines in the majority of schools, and without having an impact on revenue ( Reference Reilly, Nathan and Wiggers 25 , Reference Wolfenden, Nathan and Janssen 58 ) . Evidence suggests a multi-strategic approach strategies such as a support officer to assist with policy implementation, engagement (principals and parents), co-design and consensus with canteen managers, training, tools, resources, monitoring and feedback to schools, and marketing can improve policy implementation ( Reference Wolfenden, Nathan and Janssen 58 ) . Whilst the strategies of Vic Kids Eat Well are still evolving, the addition of Healthy Kids Advisors to support local implementation along with a multi-strategic approach is optimistic. The current study findings emphasise the need for a focus in regional areas, along with a monitoring system for compliance to guidelines.

The pricing analysis in the current studies reveals opportunities for school food provision, for example, consideration of pricing policies and strategies to subsidise or reduce the cost of healthy menu items ( Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 ) and disincentivising ‘amber’ products by marking them up a higher proportion ( Reference Wyse, Wiggers and Delaney 20 , 59 ) . Raising prices for unhealthier items can then subsidise healthier items and reduce their price ( Reference Haynes, Morley and Dixon 13 ) . There is evidence that pricing the healthiest main meal and snack items as the cheapest may encourage healthier choices ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) . Changes to the demand side, for example, school promotional strategies to increase student led demand for healthier items ( Reference Haynes, Morley and Dixon 13 ) , may make healthier choices easier for primary school children and more cost-effective for canteens ( Reference Haynes, Morley and Dixon 13 ) . Promotional strategies could include being part of a ‘meal deal’, a special price, labelled with an icon (e.g. smiley face), labelled with words to persuade purchasing and consumption such as ‘tasty’, ‘good value’ and ‘smart choice’, highlighted in an engaging way with graphic design features or colour-coded as per green traffic light system or marked as an ‘everyday’ options ( 11 ) . The increased demand for healthier items may allow bulk purchase and preparation of healthier foods and subsequently reduce costs ( 11 ) . Whilst specific to an online canteen ordering system, recent studies in NSW have revealed consumer behaviour interventions which include menu labelling, positioning, promoting, feedback and incentives can improve purchasing behaviours in primary schools ( Reference Wyse, Delaney and Stacey 26 , Reference Delaney, Wyse and Yoong 28 ) , an effect that has been sustained over 18 months ( Reference Wyse, Delaney and Stacey 27 ) . Healthy canteen changes are more likely to be successful when implemented as part of a whole of school approach with engagement from principals, teachers, students, parents and the wider school community ( Reference Billich, Adderley and Ford 14 ) . Future research could investigate current canteen usage to guide future planning and policy-making, in addition to qualitative data collection on the barriers to implementing and maintaining the guidelines of the government school canteen policy.

Strengths and limitations

This study had a large number of predominantly regional and rural primary schools providing menus. This allowed us to analyse 1818 food items offered in schools and assessed this against gold standard measures of remoteness. This is also the first study to examine adherence, price and healthiness of canteen menus across varying levels of remoteness, using the Modified Monash Model ( 34 ) . The novelty of using this model is that classified metropolitan, regional, rural and remote areas according to geographical remoteness and town size into seven categories rather than five using Australian Statistical Geography Standard remoteness structure ( 60 ) . The Modified Monash Model is increasingly being used in studies to examine health-related associations and resource allocation by level of remoteness that considers socio-economic disparities within those areas ( Reference Versace, Skinner and Bourke 61 – Reference Jacobs, Strugnell and Becker 64 ) . A further strength of the current study is that the menu items were assessed by an experienced dietitian and cross-checked by another with 100 % agreement.

The main limitation is the use of a convenience sample – schools were not necessarily representative of Victoria, or geographic regions, or of the characteristics we were interested in such as school type, remoteness or adherence to the guidelines. However, the use of the Modified Monash Model may improve the ability to generalise to other areas ( Reference Versace, Skinner and Bourke 61 ) . A related limitation is that the results may be biased towards schools willing to share their menus with researchers. Schools with less healthy menus may have been more reluctant to share their menus. The canteen menus analysed represent a snapshot in time when they were collected ( n 19 collected in 2016; n 12 in 2017, n 13 in 2018 and n 4 in 2019). Menus and prices may change over time or vary by season ( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Breheny and Jones 8 , Reference Woods, Bressan and Langelaan 15 ) and due to canteen staff turnover and possibility that more offsite retailers/catering provision services are being utilised. This will have an impact on the generalisability of the results beyond the study sample. Future research into how offsite food provision is being utilised by school canteens is required. The cross-sectional study design was descriptive, and longitudinal studies to track adherence over time and using consistent measures of remoteness would be beneficial. The FoodChecker tool ( 43 ) was utilised wherever possible for pre-packaged menu items and for recipe analysis; however, some assumptions were made during menu analysis when exact recipes were not available (see online supplementary material, Supplemental File 1 ). For example, dairy products, unless specified as reduced fat, were assumed to be full-fat. Similarly, sandwiches and rolls were assumed to contain margarine even if not stated on the menu, and fruit juices were classified as sweetened fruit drinks, unless identified as being 100 % natural fruit juice or by brand. Such assumptions, although made by an experienced dietitian, may have impacted the results.

In this sample of forty-eight Victorian school canteen menus, there was no evidence of associations of healthiness and pricing by school characteristics except for regional centres having the highest proportion of ‘black’ (banned) items compared to all other remoteness categories examined. Furthermore, the canteen menus showed low adherence to canteen menu guidelines, with many schools still offering a high proportion of banned items. Unhealthier options were found to be less expensive than healthier options. Current Victorian state-wide canteen policies in Victoria have so far not improved the healthiness of school menus. Mandatory canteen policies need to be implemented and greater investment in establishing monitoring and additional support systems to enable healthy and affordable canteen menu items to be the easy choice for children, canteen managers and food service providers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank and acknowledge the Deakin University data collection team members. The authors thank all school staff for taking time to participate in these studies. The authors would also like to thank our community partners for providing support including Portland District Health, Western Alliance, Southern Grampians and Glenelg Primary Care Partnership, Colac Area Health, Southwest Primary Care Partnership, Portland Hamilton Principal Network of Schools, Colac Corangamite Network of Schools, The Glenelg Shire Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool and District Network of Schools, Western District Health Service, and Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. Note: the opinion and analysis in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent those of the Department of Health and Human Services, the Victorian government, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, or the Victorian Minister for Health.

This study was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Partnership Project titled ‘Whole of Systems Trial of Prevention Strategies for childhood obesity: WHO STOPS Childhood Obesity’ (GNT1114118). This study was further financially supported by Goulburn Valley’s Primary Care Partnership and Western Alliance. During this time, SA was partly supported by funding from an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council/Australian National Heart Foundation Career Development Fellowship (GNT1045836). During this time, LA, MN, CB, PF, HL, CS and SA were researchers within a National Health and Medical Research Council Centre for Research Excellence in Obesity Policy and Food Systems (GNT1041020). MN was supported by NHMRC Ideas grant GNT2002334. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of the NHMRC.

The authors have none to declare

K.A.B. conceptualised the study. With support from K.A.B., A.H. and L.A. conducted the menu coding; A.H. conducted the menu analysis, and M.B. conducted the pricing analysis. A.H. led the writing of the manuscript with support from K.A.B.. M.B., L.A., M.N., C.B., P.F., H.L., C.S. and S.A. contributed to interpretation of findings and writing of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedure involving research study participants were approved by Deakin University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (2014_297 and 2018_381), the Victorian Department of Education and Training (2015_002622 and 2019–003943), the Catholic Archdiocese of Melbourne, Ballarat, and Sandhurst. Informed verbal consent was obtained from all principals of schools participating in this study.

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002300126X

Article updated 19 October 2023.

Table 4 Unadjusted comparison of the mean price difference between the price of the lowest priced ‘red’ or ‘amber’ main item and ‘green’ main item, by school characteristics ( n 45 schools)*

Hill et al. supplementary material

A correction has been issued for this article:

How healthy and affordable are foods and beverages sold in school canteens? A cross-sectional study comparing menus from Victorian primary schools – ERRATUM

Linked content

Please note a correction has been issued for this article.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 26, Issue 11

- Amy Hill (a1) , Miranda Blake (a1) , Laura Veronica Alston (a1) (a2) (a3) , Melanie S Nichols (a1) , Colin Bell (a1) (a4) , Penny Fraser (a1) (a4) , Ha ND Le (a1) , Claudia Strugnell (a1) , Steven Allender (a1) and Kristy A Bolton (a1) (a5)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002300126X

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

Essay on School canteen | School canteen Essay

Essay – school canteen.

School Canteen is a very favourite place of all students. The school canteen doesn’t only provide food to the students but also wonderful memories. The school I have been studying had a very small canteen selling only packaged foods for munching such as chips, cakes, biscuits etc. It was a small space comprising of 3 tables & 9 chairs. During winters the canteen also used to sell soups.

The third food counter had the homely food items meant for lunch, such as roti, Paratha, various types of sabjis, curries, even rice, dal etc was served for the hostel students mainly. The lunch served was made of less oil & spices. The items were tasty as well as full of nutrition. The school canteen always served hot, warm food to the students. The potato staffed Paratha was very tasty & mostly had by the students. The school canteen only served vegetarian food to the students. The third counter had a huge rush during the lunch break. But later on the amount of chair & tables were decreased because of the increased of gossip & chit-chat at the student.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

We have a strong team of experienced teachers who are here to solve all your exam preparation doubts, rs aggarwal class 5 solutions chapter 10, nios class 10 social science chapter 12 solution – agriculture in india, assam scert class 8 history and political science chapter 5 solutions, sikkim scert class 4 english chapter 2a my bustee solution.

Paragraph on School Canteen

Students are often asked to write a paragraph on School Canteen in their schools. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 200-word, and 250-word paragraphs on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

Paragraph on School Canteen in 100 Words

A school canteen is a special place where students eat lunch. It is like a big kitchen with lots of yummy food. Kids can buy sandwiches, fruits, and milk there. There are long tables and benches where friends sit together and share their food. The people who work in the canteen wear hats and gloves to keep the food clean. They smile and serve meals to the kids. After eating, students must throw away trash in bins to keep the canteen neat. The school canteen is not just for eating but also for laughing and talking with friends during the break.

Paragraph on School Canteen in 200 Words

A school canteen is a special place where students go to eat their lunch or grab a quick snack during breaks. Imagine a room filled with the smell of tasty food, where you can hear the sound of friends chatting and laughing. The canteen is like the heart of the school, always busy and full of life. It has a counter where you stand in line to get your food, and behind it, kind people wearing hats and aprons serve you meals. The menu has lots of choices, like sandwiches, fruits, milk, juice, and sometimes even pizza or burgers! There are long tables and benches where everyone sits together. You can share food with your friends, talk about your day, and enjoy a nice break from classes. The canteen is also a place where you learn to make choices about what to eat and to pick healthy foods that give you energy to learn and play. It’s not just about eating; it’s where you learn to wait for your turn, to be polite while asking for your favorite cookie, and to keep your eating area clean for the next person. A school canteen is a fun and important part of your day at school!

Paragraph on School Canteen in 250 Words

A school canteen is a special place where students go to eat and take a break during their busy school day. It’s a lively part of the school where you can see friends sharing food, stories, and laughter. Picture this: rows of tables and chairs where students sit and eat their meals, with the smell of tasty food in the air. The canteen serves different kinds of food, from sandwiches and salads to hot meals and snacks. It’s important that the food is not only delicious but also healthy because good food helps your brain and body grow strong. The people who work there are usually very friendly, always ready to serve you what you would like to eat or answer any questions you might have about the menu. In the canteen, you can also learn about making good food choices and how to manage your pocket money when buying your lunch or a treat. The place is kept clean by staff, and students are expected to help by throwing away their trash after eating, to keep it nice for everyone. Safety is also a big part of the canteen’s rules; hot food is handled with care, and there’s always someone to help if an accident happens. The school canteen is more than just a place to eat; it’s where you can relax with your friends and recharge for the rest of the school day. It’s a cheerful spot that plays an important part in your school life.

That’s it! I hope the paragraphs have helped you.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Students’ food consumption in a school canteen : analysis of what they choose from the canteen gallery and what they discard, by gender and age

2013, The 4th European Conference on Health Education Schools Equity Education and Health

Related Papers

Monica Truninger

Revista de Nutrição

Elisabetta Recine

Objective: To characterize the school cafeterias in the Federal District of Brazil with respect to the promotion of healthy eating in schools. Methods: This is a descriptive, analytical, cross-sectional study, with a representative sample of schools with cafeterias in the Federal District, Brazil (n=202). The data were collected from April to November 2010 by means of on-site interviews and a structured questionnaire. The Pearson's chi-squared and Student's t tests were used. Results: A higher prevalence of outsourcing, and few employees and dieticians were observed. The prevailing foods were baked sausage, cheese, or chicken rolls or pastries. It was also found that 42.2% of the schools influence the menu of the cafeterias, and 58.6% of the representatives believe in the possibility of influencing the students' eating habits. However, 68.0% of the respondents do not believe in the economic feasibility of completely healthful school cafeterias. Approximately 30.0% of the...

Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences

Carla Roggi

Monica Truninger , Ana Horta

Vanda Aparecida Silva

BMC Pediatrics

Laura Terragni

Food Service Technology

Bent Mikkelsen , Vivian Barnekow

Ciencia & saude coletiva

Camile Alvarenga

The study analyzed and compared the types of food sold in the surroundings of 30 private and 26 public elementary schools in the city of Niterói, Rio de Janeiro. Data were collected by audit using a checklist instrument to characterize establishments (formal or informal) and identify the types of food and beverages sold, which were classified by processing level (fresh, processed, and ultraprocessed). Mann-Whitney statistical tests were used to verify the difference in the type of trade outlets d the categories of food sold between schools. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to verify the difference in the amount of food traded between the categories. The amount of ultraprocessed food in the surroundings of public and private schools was statistically higher (p=0.0001) than the other categories. Some culinary preparations had a high rate of energy contribution from ultraprocessed foods (above 15%). There was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.478) in the categories of food...

Nutrición hospitalaria

Rafael Moreno

The prime objective of our work was to study the eating habits at lunchtime of staff and students at a University of "hidden due to confidentiality"of Spain. The second one was to attempt to reduce the energy consumption of cholesterol and fat in the diet of those groups. The study was made between 2010 and 2012 in the main canteen serving food at this university, focusing on food intake at lunch, the main meal of the day, containing between 35 and 40% of the total calories ingested throughout the day. A total of 9530 observations were made, each one corresponding to the nutritional valuation of food eaten (a complete lunch) per person, by students, teachers and service personnel. The study was carried out in 5 intervention stages and a previous non-intervention one to establish the habitual food intake of these groups. In each stage the nutritional information supplied to canteen users was increased to that in the final stage a modification of the price of the menus serve...

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Cadernos de Saúde Pública

Ariene Carmo

Publisher ijmra.us UGC Approved

Health Education

Saoirse Nic Gabhainn

Maria Fontes

Archivos latinoamericanos de nutrición

Dalton Francisco de Andrade

Revista chilena de nutrición

Patrícia Henriques

American Journal of Preventive Medicine

Rebecca Roberts

La Granja: Revista de Ciencias de la Vida

Frontiers in Public Health

Carry M. Renders

Public Health Nutrition

Leila Karhunen

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health

Giada Danesi , Laura Hamilton

Revista espanola de salud publica

Miguel Royo-bordonada

Janaína Braga de Paiva , Ligia Amparo

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health