Systematic Reviews

- Introduction

- Review Process: Step by Step

- 1. Planning a Review

- 2. Defining Your Question & Criteria

- 3. Standards & Protocols

Designing Your Search Strategy

Search strategy checklists, pre-search tips, search strategies: filters & hedges, search terms, search strategies: and/or, phrase searching & truncation.

- 5. Locating Published Research

- 6. Locating Grey Literature

- 7. Managing & Documenting Results

- 8. Selecting & Appraising Studies

- 9. Extracting Data

- 10. Writing a Systematic Review

- Tools & Software

- Guides & Tutorials

- Accessing Resources

- Research Assistance

A well designed search strategy is essential to the success of your systematic review. Your strategy should be specific, unbiased, reproducible and will typically include subject headings along with a range of keywords/phrases for each of your concepts.

Your searches should be designed to capture as many studies as possible that meet your criteria.

Chapter 4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions provides detailed guidance for searching and study selection; see Supplement 3.8 Adapting search strategies across databases / sources for translating your search across databases.

Systematic Reviews: Constructing a Search Strategy and Searching for Evidence from the Joanna Briggs Institute provides step-by-step guidance using PubMed as an example database.

General Steps:

- Locate previous/ relevant searches

- Identify your databases

- Develop your search terms and design search

- Evaluate and modify your search

- Document your search ( PRISMA-S Checklist)

- Translate your search for other databases

- Step by Step Systematic Review Search Checklist from MD Anderson Center Library

- PRESS Peer Review Checklist for Search Strategies

Conduct a preliminary set of scoping searches in various databases to test out your search terms (keywords and subject headings) and locate additional terms for your concepts.

Try building a "gold set" of relevant references to help you identify search terms. Sources for this gold set may include:

- Recommended key papers

- Papers by known authors in the field

- Results of preliminary searches from key databases such

- Reviewing references and "cited by" articles lists for key papers

- Articles that have been published in authoritative journals

Hedges/ Filters

- PubMed Special Queries

Hedges are search strings created by experts to help you retrieve specific types of studies or topics; a hedge will filter your results by adding specific search terms, or specific combinations of search terms, to your search.

Hedges can be good starting points but you may need to modify the search string to fit your research. Resources for hedges:

- University of Texas, School of Public Health (study type)

- McMaster University Health Information Research Unit

- The InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub-Group Search Filter Resource

- Pubmed Search Strategies blog

- PubMed Special Queries Topic-Specific PubMed Queries; includes keyword and search strategy examples.

Example: Health Disparities & Minority Health Search Strategies

| ((ethnic disparities[TIAB] OR ethnic group[TIAB] OR |

refugees[MH] OR | urban populations[TIAB] OR vulnerable population[TIAB] OR vulnerable populations[MH] OR vulnerable populations[TIAB] OR working poor[MH] OR working poor[TIAB] OR bisexuals[TIAB] OR bisexual[TIAB] OR bigender[TIAB] OR disorders of sex development[MH] OR disorders of sex development[TIAB] OR female homosexuality[TIAB] OR gay[TIAB] OR gays[TIAB] OR gender change[TIAB] OR gender confirmation[TIAB] OR gender disorder[TIAB] OR gender disorders[TIAB] OR gender dysphoria[TIAB] OR gender diverse[TIAB] OR gender-diverse[TIAB] OR gender diversity[TIAB] OR gender identity[MH] OR gender identity[TIAB] OR gender minorities[TIAB] OR gender non conforming[TIAB] OR gender non-conforming[TIAB] OR gender orientation[TIAB] OR genderqueer[TIAB] OR gender reassignment[TIAB] OR gender surgery[TIAB] OR GLBT[TIAB] OR GLBTQ[TIAB] OR health services for transgender persons[MH] OR homophile[TIAB] OR homophilia[TIAB] OR homosexual[TIAB] OR homosexuality[MH] OR homosexuality, female[MH] OR homosexuality, male[MH] OR homosexuals[TIAB] OR intersex[TIAB] OR lesbian[TIAB] OR lesbianism[TIAB] OR lesbians[TIAB] ORLGBBTQ[TIAB] OR LGBT[TIAB] OR LGBTI[TIAB] OR LGBTQ[TIAB] OR LGBTQI[TIAB] OR LGBTQIA[TIAB] OR men having sex with men[TIAB] OR men who have sex with men[TIAB] OR men who have sex with other men[TIAB] OR nonheterosexual[TIAB] OR non-heterosexual[TIAB] OR non heterosexuals[TIAB] OR nonheterosexuals[TIAB] OR pansexual[TIAB] OR polysexual[TIAB] OR queer[All Fields] OR same sex [TIAB] OR sexual and gender disorders[MH] OR sexual and gender minorities[MH] OR sex change[TIAB] OR sex reassignment[TIAB] OR sex reassignment procedures[MH] OR sex reassignment surgery[MH] OR sex reassignment surgery[TIAB] OR sexual diversity[TIAB] OR sexual minorities[TIAB] OR sexual minority[TIAB] OR sexual orientation[TIAB] OR transgender*[TIAB] OR transgender persons[MH] OR transsexual*[TIAB] OR transman[TIAB] OR trans men[TIAB] OR transmen[TIAB] OR transsexualism[MH] OR transsexualism[TIAB] OR transwoman[TIAB] OR trans women[TIAB] OR transwomen[TIAB] OR two spirit[TIAB] OR two-spirit[TIAB] OR women who have sex with women[TIAB])) |

- Subject Headings

- Keywords Vs. Subject Headings

- Locating Subject Headings

- Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Keyword & Subject Headings Logic Grid

You can use your PICOTS concepts as preliminary search terms. The important terms in this question:

In adults , is screening for depression and feedback of results to providers more effective than no screening and feedback in improving outcomes of major depression in primary care settings?

...might include:

Major depression

Primary Care

(From Lackey, M. (2013). Systematic reviews: Searching the literature [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://guides.lib.unc.edu/ld.php?content_id=258919 )

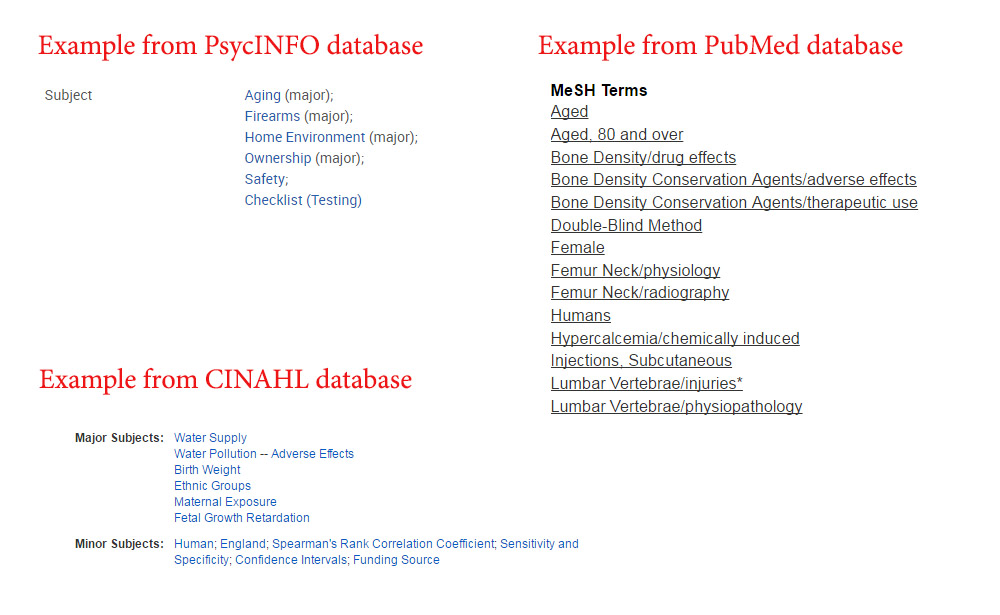

Your search will include both keywords and subject headings. Controlled vocabulary systems, such as the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) , use pre-set terms that are used to tag resources on similar subjects. See boxes below for more information on finding and using subject terms.

Not all databases will have subject heading searching and for those that do, the subject heading categories may differ between databases. This is because databases classify articles using different criteria.

Using the keywords from our example, here are some MeSH terms for:

Adults : Adult (A person having attained full growth or maturity. Adults are of 19 through 44 years of age. For a person between 19 and 24 years of age, YOUNG ADULT is available.)

Screening : Mass Screening (Organized periodic procedures performed on large groups of people for the purpose of detecting disease.)

Major depression : Depressive Disorder, Major (Marked depression appearing in the involution period and characterized by hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, and agitation.)

Here is a LCSH subject term for:

Depression : Depression, mental (Dejection ; Depression, Unipolar ; Depressive disorder ; Depressive psychoses ; Melancholia ; Mental depression ; Unipolar depression)

- Most EBSCO databases have a tool to help you discover subject terms . See Academic Search Complete > Subject Terms and Academic Search Complete > Subject Terms: Thesaurus

- Most ProQuest databases have a tool to help you discover subject terms: See PsycInfo > Thesaurus

- When you find a useful article, look at the article's Subject Headings (or Subject or Subject Terms) , and record them as possible terms to use in a subject term search.

Here is an example of the subject terms listed for a systematic review found in PsycINFO, " Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force " (2016).

MeSH are standardized terms that describe the main concepts of PubMed/MedLine articles. Searching with MeSH can increase the precision of your search by providing a consistent way to retrieve articles that may use different terminology or spelling variations.

Note: new articles will not have MeSH terms; the indexing process may take up to a few weeks for newly ingested articles.

Use the MeSH database to locate and build a search using MeSH.

To search the MeSH database:

- Search for 1 concept at a time.

- If you do not see a relevant MeSH in the results, search again with a synonym or related term.

- Click on the MeSH term to view to the complete record, subheadings, broader and narrower terms.

Build a search from the results list or from the MeSH term record to specify subheadings.

- Select the box next to the MeSH term or subheadings that you wish to search and click Add to Search Builder.

- You may need to switch AND to OR , depending on how you would like to combine terms.

- Repeat the above steps to add additional MeSH terms. When your search is ready, click Search PubMed.

Logic Grid with Keywords and Index Terms or Subject Headings from Systematic Reviews: Constructing a Search Strategy and Searching for Evidence.

Bhuiyan, M. U., Stiboy, E., Hassan, M. Z., Chan, M., Islam, M. S., Haider, N., Jaffe, A., & Homaira, N. (2021). Epidemiology of COVID-19 infection in young children under five years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine , 39 (4), 667–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.078

|

| |

| 1 | ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "2019 nCoV" OR 2019ncov OR "2019-nCoV" OR "2019 novel coronavirus" OR "Novel coronavirus 2019" OR "COVID 19" OR "COVID-19" OR "COVID19" OR "Wuhan coronavirus" OR "Wuhan pneumonia" OR "SARS CoV-2" OR "SARS-Cov-2" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( children OR child* OR infant OR pediatric OR paediatric OR adolescent ) ) |

|

| |

|

| |

| 1 | TS=("2019 nCoV") OR TS=(2019ncov) OR TS=("2019-nCoV") OR TS=("2019 novel coronavirus") OR TS=("Novel coronavirus 2019") OR TS=("COVID 19") OR TS=("COVID-19") OR TS=(COVID19) OR TS=("Wuhan coronavirus") OR TS=("Wuhan pneumonia") OR TS=("SARS CoV-2") OR TS=("SARS-Cov-2") Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years |

| 2 | TS=(infant) OR TS=(child) OR TS=(children) OR TS=(adolescent) OR TS=(paediatric) OR TS=(pediatric) Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years |

| 3 | #2 AND #1 Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| (((((((((((("2019 nCoV"[Title/Abstract] OR "2019ncov"[Title/Abstract]) OR "2019-nCoV"[Title/Abstract]) OR "2019 novel coronavirus"[Title/Abstract]) OR "Novel coronavirus 2019"[Title/Abstract]) OR "COVID 19"[Title/Abstract]) OR "COVID-19"[Title/Abstract]) OR "COVID19"[Title/Abstract]) OR "Wuhan coronavirus"[Title/Abstract]) OR "SARS CoV-2"[Title/Abstract]) OR "SARS-Cov-2"[Title/Abstract]) AND (((((((((((infant[Title/Abstract] OR "infant"[MeSH Terms]) OR child[Title/Abstract]) OR "child"[MeSH Terms]) OR children[Title/Abstract]) OR "child"[MeSH Terms]) OR adolescent[Title/Abstract]) OR "adolescent"[MeSH Terms]) OR paediatric[Title/Abstract]) OR "pediatrics"[MeSH Terms]) OR pediatric[Title/Abstract]) OR "pediatrics"[MeSH Terms])) AND "humans"[MeSH Terms]) AND (((((((((((("2019 nCoV"[Title/Abstract] OR "2019ncov"[Title/Abstract]) OR "2019-nCoV"[Title/Abstract]) OR "2019 novel coronavirus"[Title/Abstract]) OR "Novel coronavirus 2019"[Title/Abstract]) OR "COVID 19"[Title/Abstract]) OR "COVID-19"[Title/Abstract]) OR "COVID19"[Title/Abstract]) OR "Wuhan coronavirus"[Title/Abstract]) OR "SARS CoV-2"[Title/Abstract]) OR "SARS-Cov-2"[Title/Abstract]) AND (((((((((((infant[Title/Abstract] OR "infant"[MeSH Terms]) OR child[Title/Abstract]) OR "child"[MeSH Terms]) OR children[Title/Abstract]) OR "child"[MeSH Terms]) OR adolescent[Title/Abstract]) OR "adolescent"[MeSH Terms]) OR paediatric[Title/Abstract]) OR "pediatrics"[MeSH Terms]) OR pediatric[Title/Abstract]) OR "pediatrics"[MeSH Terms])) AND "humans"[MeSH Terms]) |

- Boolean Logic: AND, OR, NOT

- Phrase Searching " "

- Truncation *

- Proximity Searching

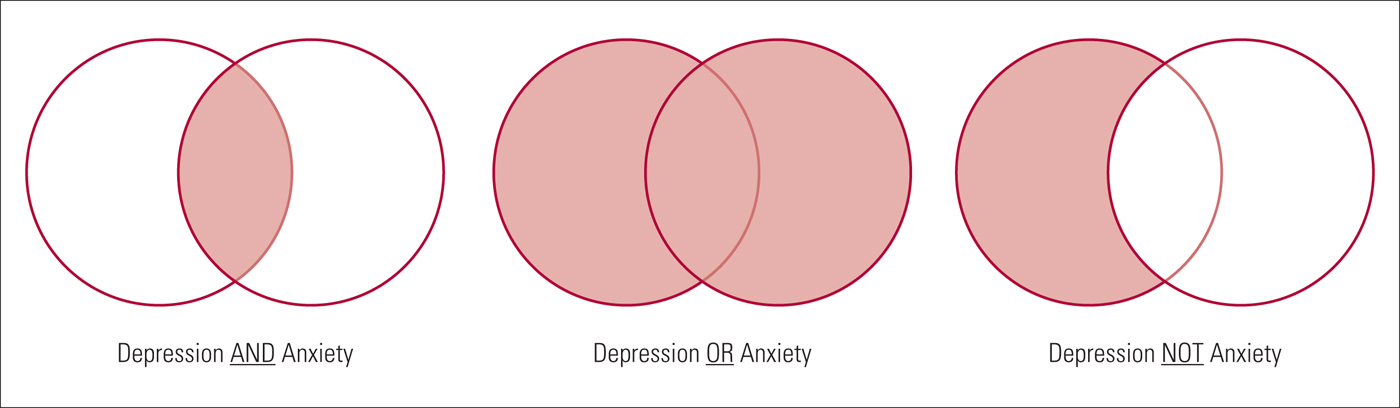

AND, OR, NOT

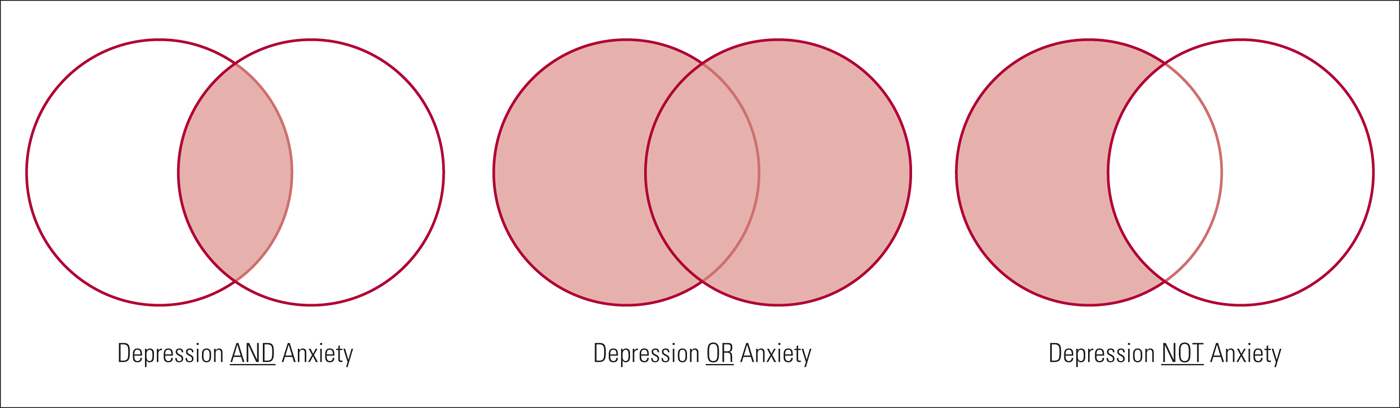

Join together search terms in a logical manner.

AND - narrows searches, used to join dissimilar terms OR - broadens searches, used to join similar terms

NOT - removes results containing specified keywords

#1 "major depression" AND "primary care"

#2 screen* OR feedback

#3 (screen* OR feedback)

AND “major depression”

AND “primary care”

"major depression" NOT suicide

" " To search for specific phrases, enclose them in quotation marks . The database will search for those words together in that order.

“ primary care ”

“ major depression ”

Truncate a word in order to search for different forms of the same word. Many databases use the asterisk * as the truncation symbol.

Add the truncation symbol to the word screen * to search for screen, screens, screening, etc.

You do have to be careful with truncation. If you add the truncation symbol to the word minor* , the database will search for minor, minors, minority, minorities, etc.

Not all databases support proximity searching. You can use these strategies in ProQuest databases such as Sociological Abstracts .

pre/# is used to search for terms in proximity to each other in a specific order; # is replaced with the number of words permitted between the search terms.

Sample Search: parent* pre/2 educational (within 2 words & in order )

- This would retrieve articles with no more than two words between parent* and educational (in this order) e.g. " Parent practices and educational achievement" OR " Parents on Educational Attainment" OR " Parental Values, Educational Attainment" etc.

w/# is used to search for terms in proximity to each other in any order ; # is replaced with the number of words permitted between the search terms.

Sample Search: parent* w/3 educational (within 3 words & in any order )

- This would retrieve articles with no more than three words between parent* and educational (in any order) e.g. "Educational practices of parents" OR "Parents value motivation and education" OR "Educational attainments of Latino parents"

- << Previous: 3. Standards & Protocols

- Next: 5. Locating Published Research >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 4:31 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/systematic-reviews

Last updated 20/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > BJPsych Advances

- > Volume 24 Issue 2

- > How to carry out a literature search for a systematic...

Article contents

- LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- DECLARATION OF INTEREST

Defining the clinical question

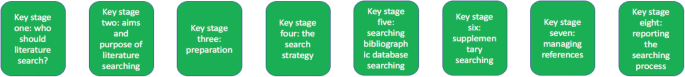

Scoping search, search strategy, sources to search, developing a search strategy, searching electronic databases, supplementary search techniques, obtaining unpublished literature, conclusions, how to carry out a literature search for a systematic review: a practical guide.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2018

Performing an effective literature search to obtain the best available evidence is the basis of any evidence-based discipline, in particular evidence-based medicine. However, with a vast and growing volume of published research available, searching the literature can be challenging. Even when journals are indexed in electronic databases, it can be difficult to identify all relevant studies without an effective search strategy. It is also important to search unpublished literature to reduce publication bias, which occurs from a tendency for authors and journals to preferentially publish statistically significant studies. This article is intended for clinicians and researchers who are approaching the field of evidence synthesis and would like to perform a literature search. It aims to provide advice on how to develop the search protocol and the strategy to identify the most relevant evidence for a given research or clinical question. It will also focus on how to search not only the published but also the unpublished literature using a number of online resources.

• Understand the purpose of conducting a literature search and its integral part of the literature review process

• Become aware of the range of sources that are available, including electronic databases of published data and trial registries to identify unpublished data

• Understand how to develop a search strategy and apply appropriate search terms to interrogate electronic databases or trial registries

A literature search is distinguished from, but integral to, a literature review. Literature reviews are conducted for the purpose of (a) locating information on a topic or identifying gaps in the literature for areas of future study, (b) synthesising conclusions in an area of ambiguity and (c) helping clinicians and researchers inform decision-making and practice guidelines. Literature reviews can be narrative or systematic, with narrative reviews aiming to provide a descriptive overview of selected literature, without undertaking a systematic literature search. By contrast, systematic reviews use explicit and replicable methods in order to retrieve all available literature pertaining to a specific topic to answer a defined question (Higgins Reference Higgins and Green 2011 ). Systematic reviews therefore require a priori strategies to search the literature, with predefined criteria for included and excluded studies that should be reported in full detail in a review protocol.

Performing an effective literature search to obtain the best available evidence is the basis of any evidence-based discipline, in particular evidence-based medicine (Sackett Reference Sackett 1997 ; McKeever Reference McKeever, Nguyen and Peterson 2015 ). However, with a vast and growing volume of published research available, searching the literature can be challenging. Even when journals are indexed in electronic databases, it can be difficult to identify all relevant studies without an effective search strategy (Hopewell Reference Hopewell, Clarke and Lefebvre 2007 ). In addition, unpublished data and ‘grey’ literature (informally published material such as conference abstracts) are now becoming more accessible to the public. It is important to search unpublished literature to reduce publication bias, which occurs because of a tendency for authors and journals to preferentially publish statistically significant studies (Dickersin Reference Dickersin and Min 1993 ). Efforts to locate unpublished and grey literature during the search process can help to reduce bias in the results of systematic reviews (Song Reference Song, Parekh and Hooper 2010 ). A paradigmatic example demonstrating the importance of capturing unpublished data is that of Turner et al ( Reference Turner, Matthews and Linardatos 2008 ), who showed that using only published data in their meta-analysis led to effect sizes for antidepressants that were one-third (32%) larger than effect sizes derived from combining both published and unpublished data. Such differences in findings from published and unpublished data can have real-life implications in clinical decision-making and treatment recommendation. In another relevant publication, Whittington et al ( Reference Whittington, Kendall and Fonagy 2004 ) compared the risks and benefits of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of depression in children. They found that published data suggested favourable risk–benefit profiles for SSRIs in this population, but the addition of unpublished data indicated that risk outweighed treatment benefits. The relative weight of drug efficacy to side-effects can be skewed if there has been a failure to search for, or include, unpublished data.

In this guide for clinicians and researchers on how to perform a literature search we use a working example about efficacy of an intervention for bipolar disorder to demonstrate the search techniques outlined. However, the overarching methods described are purposefully broad to make them accessible to all clinicians and researchers, regardless of their research or clinical question.

The review question will guide not only the search strategy, but also the conclusions that can be drawn from the review, as these will depend on which studies or other forms of evidence are included and excluded from the literature review. A narrow question will produce a narrow and precise search, perhaps resulting in too few studies on which to base a review, or be so focused that the results are not useful in wider clinical settings. Using an overly narrow search also increases the chances of missing important studies. A broad question may produce an imprecise search, with many false-positive search results. These search results may be too heterogeneous to evaluate in one review. Therefore from the outset, choices should be made about the remit of the review, which will in turn affect the search.

A number of frameworks can be used to break the review question into concepts. One such is the PICO (population, intervention, comparator and outcome) framework, developed to answer clinical questions such as the effectiveness of a clinical intervention (Richardson Reference Richardson, Wilson and Nishikawa 1995 ). It is noteworthy that ‘outcome’ concepts of the PICO framework are less often used in a search strategy as they are less well defined in the titles and abstracts of available literature (Higgins Reference Higgins and Green 2011 ). Although PICO is widely used, it is not a suitable framework for identifying key elements of all questions in the medical field, and minor adaptations are necessary to enable the structuring of different questions. Other frameworks exist that may be more appropriate for questions about health policy and management, such as ECLIPSE (expectation, client group, location, impact, professionals, service) (Wildridge Reference Wildridge and Bell 2002 ) or SPICE (setting, perspective, intervention, comparison, evaluation) for service evaluation (Booth Reference Booth 2006 ). A detailed overview of frameworks is provided in Davies ( Reference Davies 2011 ).

Before conducting a comprehensive literature search, a scoping search of the literature using just one or two databases (such as PubMed or MEDLINE) can provide valuable information as to how much literature for a given review question already exists. A scoping search may reveal whether systematic reviews have already been undertaken for a review question. Caution should be taken, however, as systematic reviews that may appear to ask the same question may have differing inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies included in the review. In addition, not all systematic reviews are of the same quality. If the original search strategy is of poor quality methodologically, original data are likely to have been missed and the search should not simply be updated (compare, for example, Naughton et al ( Reference Naughton, Clarke and O'Leary 2014 ) and Caddy et al ( Reference Caddy, Amit and McCloud 2015 ) on ketamine for treatment-resistant depression).

The first step in conducting a literature search should be to develop a search strategy. The search strategy should define how relevant literature will be identified. It should identify sources to be searched (list of databases and trial registries) and keywords used in the literature (list of keywords). The search strategy should be documented as an integral part of the systematic review protocol. Just as the rest of a well-conducted systematic review, the search strategy used needs to be explicit and detailed such that it could reproduced using the same methodology, with exactly the same results, or updated at a later time. This not only improves the reliability and accuracy of the review, but also means that if the review is replicated, the difference in reviewers should have little effect, as they will use an identical search strategy. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement was developed to standardise the reporting of systematic reviews (Moher Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 2009 ). The PRISMA statement consists of a 27-item checklist to assess the quality of each element of a systematic review (items 6, 7 and 8 relate to the quality of literature searching) and also to guide authors when reporting their findings.

There are a number of databases that can be searched for literature, but the identification of relevant sources is dependent on the clinical or research question (different databases have different focuses, from more biology to more social science oriented) and the type of evidence that is sought (i.e. some databases report only randomised controlled trials).

• MEDLINE and Embase are the two main biomedical literature databases. MEDLINE contains more than 22 million references from more than 5600 journals worldwide. In addition, the MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations database holds references before they are published on MEDLINE. Embase has a strong coverage of drug and pharmaceutical research and provides over 30 million references from more than 8500 currently published journals, 2900 of which are not in MEDLINE. These two databases, however, are only available to either individual subscribers or through institutional access such as universities and hospitals. PubMed, developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information of the US National Library of Medicine, provides access to a free version of MEDLINE and is accessible to researchers, clinicians and the public. PubMed comprises medical and biomedical literature indexed in MEDLINE, but provides additional access to life science journals and e-books.

In addition, there are a number of subject- and discipline-specific databases.

• PsycINFO covers a range of psychological, behavioural, social and health sciences research.

• The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) hosts the most comprehensive source of randomised and quasi-randomised controlled trials. Although some of the evidence on this register is also included in Embase and MEDLINE, there are over 150 000 reports indexed from other sources, such as conference proceedings and trial registers, that would otherwise be less accessible (Dickersin Reference Dickersin, Manheimer and Wieland 2002 ).

• The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), British Nursing Index (BNI) and the British Nursing Database (formerly BNI with Full Text) are databases relevant to nursing, but they span literature across medical, allied health, community and health management journals.

• The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) is a database specifically for alternative treatments in medicine.

The examples of specific databases given here are by no means exhaustive, but they are popular and likely to be used for literature searching in medicine, psychiatry and psychology. Website links for these databases are given in Box 1 , along with links to resources not mentioned above. Box 1 also provides a website link to a couple of video tutorials for searching electronic databases. Box 2 shows an example of the search sources chosen for a review of a pharmacological intervention of calcium channel antagonists in bipolar disorder, taken from a recent systematic review (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Saunders and Attenburrow 2016a ).

BOX 1 Website links of search sources to obtain published and unpublished literature

Electronic databases

• MEDLINE/PubMed: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed

• Embase: www.embase.com

• PsycINFO: www.apa.org/psycinfo

• Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL): www.cochranelibrary.com

• Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL): www.cinahl.com

• British Nursing Index: www.bniplus.co.uk

• Allied and Complementary Medicine Database: https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/amed-the-allied-and-complementary-medicine-database

Grey literature databases

• BIOSIS Previews (part of Thomson Reuters Web of Science): https://apps.webofknowledge.com

Trial registries

• ClinicalTrials.gov: www.clinicaltrials.gov

• Drugs@FDA: www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf

• European Medicines Agency (EMA): www.ema.europa.eu

• World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP): www.who.int/ictrp

• GlaxoSmithKline Study Register: www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com

• Eli-Lilly clinical trial results: https://www.lilly.com/clinical-study-report-csr-synopses

Guides to further resources

• King's College London Library Services: http://libguides.kcl.ac.uk/ld.php?content_id=17678464

• Georgetown University Medical Center Dahlgren Memorial Library: https://dml.georgetown.edu/core

• University of Minnesota Biomedical Library: https://hsl.lib.umn.edu/biomed/help/nursing

Tutorial videos

• Searches in electronic databases: http://library.buffalo.edu/hsl/services/instruction/tutorials.html

• Using the Yale MeSH Analyzer tool: http://library.medicine.yale.edu/tutorials/1559

BOX 2 Example of search sources chosen for a review of calcium channel antagonists in bipolar disorder (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Saunders and Attenburrow 2016a )

Electronic databases searched:

• MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations

For a comprehensive search of the literature it has been suggested that two or more electronic databases should be used (Suarez-Almazor Reference Suarez-Almazor, Belseck and Homik 2000 ). Suarez-Almazor and colleagues demonstrated that, in a search for controlled clinical trials (CCTs) for rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis and lower back pain, only 67% of available citations were found by both Embase and MEDLINE. Searching MEDLINE alone would have resulted in 25% of available CCTs being missed and searching Embase alone would have resulted in 15% of CCTs being missed. However, a balance between the sensitivity of a search (an attempt to retrieve all relevant literature in an extensive search) and the specificity of a search (an attempt to retrieve a more manageable number of relevant citations) is optimal. In addition, supplementing electronic database searches with unpublished literature searches (see ‘Obtaining unpublished literature’ below) is likely to reduce publication bias. The capacity of the individuals or review team is likely largely to determine the number of sources searched. In all cases, a clear rationale should be outlined in the review protocol for the sources chosen (the expertise of an information scientist is valuable in this process).

Important methodological considerations (such as study design) may also be included in the search strategy. Dependent on the databases and supplementary sources chosen, filters can be used to search the literature by study design (see ‘Searching electronic databases’). For instance, if the search strategy is confined to one study design term only (e.g. randomised controlled trial, RCT), only the articles labelled in this way will be selected. However, it is possible that in the database some RCTs are not labelled as such, so they will not be picked up by the filtered search. Filters can help reduce the number of references retrieved by the search, but using just one term is not 100% sensitive, especially if only one database is used (i.e. MEDLINE). It is important for systematic reviewers to know how reliable such a strategy can be and treat the results with caution.

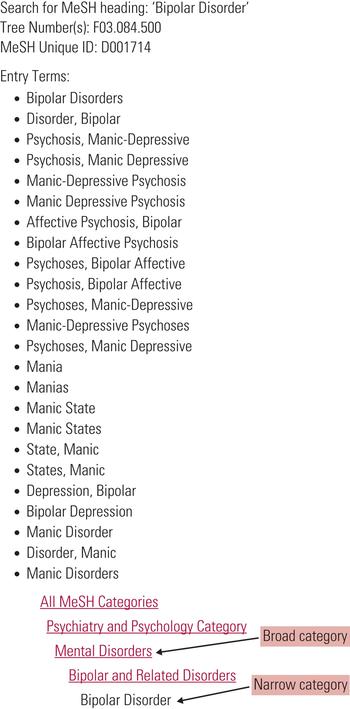

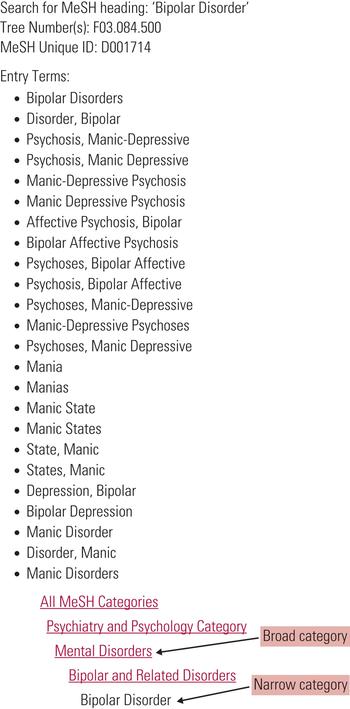

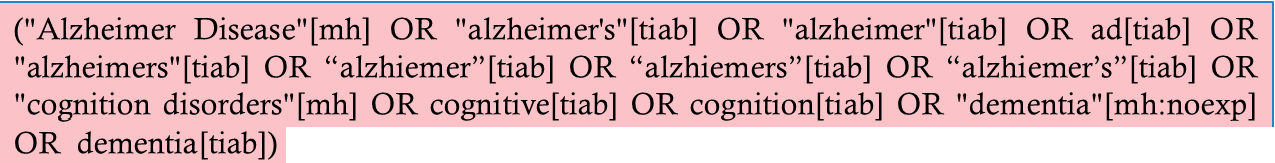

Identifying search terms

Standardised search terms are thesaurus and indexing terms that are used by electronic databases as a convenient way to categorise articles, allowing for efficient searching. Individual database records may be assigned several different standardised search terms that describe the same or similar concepts (e.g. bipolar disorder, bipolar depression, manic–depressive psychosis, mania). This has the advantage that even if the original article did not use the standardised term, when the article is catalogued in a database it is allocated that term (Guaiana Reference Guaiana, Barbui and Cipriani 2010 ). For example, an older paper might refer to ‘manic depression’, but would be categorised under the term ‘bipolar disorder’ when catalogued in MEDLINE. These standardised search terms are called MeSH (medical subject headings) in MEDLINE and PubMed, and Emtree in Embase, and are organised in a hierarchal structure ( Fig. 1 ). In both MEDLINE and Embase an ‘explode’ command enables the database to search for a requested term, as well as specific related terms. Both narrow and broader search terms can be viewed and selected to be included in the search if appropriate to a topic. The Yale MeSH Analyzer tool ( mesh.med.yale.edu ) can be used to help identify potential terms and phrases to include in a search. It is also useful to understand why relevant articles may be missing from an initial search, as it produces a comparison grid of MeSH terms used to index each article (see Box 1 for a tutorial video link).

FIG 1 Search terms and hierarchical structure of MeSH (medical subject heading) in MEDLINE and PubMed.

In addition, MEDLINE also distinguishes between MeSH headings (MH) and publication type (PT) terms. Publication terms are less about the content of an article than about its type, specifying for example a review article, meta-analysis or RCT.

Both MeSH and Emtree have their own peculiarities, with variations in thesaurus and indexing terms. In addition, not all concepts are assigned standardised search terms, and not all databases use this method of indexing the literature. It is advisable to check the guidelines of selected databases before undertaking a search. In the absence of a MeSH heading for a particular term, free-text terms could be used.

Free-text terms are used in natural language and are not part of a database’s controlled vocabulary. Free-text terms can be used in addition to standardised search terms in order to identify as many relevant records as possible (Higgins Reference Higgins and Green 2011 ). Using free-text terms allows the reviewer to search using variations in language or spelling (e.g. hypomani* or mania* or manic* – see truncation and wildcard functions below and Fig. 2 ). A disadvantage of free-text terms is that they are only searched for in the title and abstracts of database records, and not in the full texts, meaning that when a free-text word is used only in the body of an article, it will not be retrieved in the search. Additionally, a number of specific considerations should be taken into account when selecting and using free-text terms:

• synonyms, related terms and alternative phrases (e.g. mood instability, affective instability, mood lability or emotion dysregulation)

• abbreviations or acronyms in medical and scientific research (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging or MRI)

• lay and medical terminology (e.g. high blood pressure or hypertension)

• brand and generic drug names (e.g. Prozac or fluoxetine)

• variants in spelling (e.g. UK English and American English: behaviour or behavior; paediatric or pediatric).

FIG 2 Example of a search strategy about bipolar disorder using MEDLINE (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Saunders and Attenburrow 2016a ). The strategy follows the PICO framework and includes MeSH terms, free-text keywords and a number of other techniques, such as truncation, that have been outlined in this article. Numbers in bold give the number of citations retrieved by each search.

Truncation and wildcard functions can be used in most databases to capture variations in language:

• truncation allows the stem of a word that may have variant endings to be searched: for example, a search for depress* uses truncation to retrieve articles that mention both depression and depressive; truncation symbols may vary by database, but common symbols include: *, ! and #

• wild cards substitute one letter within a word to retrieve alternative spellings: for example, ‘wom?n’ would retrieve the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’.

Combining search terms

Search terms should be combined in the search strategy using Boolean operators. Boolean operators allow standardised search terms and free-text terms to be combined. There are three main Boolean operators – AND, OR and NOT ( Fig. 3 ).

• OR – this operator is used to broaden a search, finding articles that contain at least one of the search terms within a concept. Sets of terms can be created for each concept, for example the population of interest: (bipolar disorder OR bipolar depression). Parentheses are used to build up search terms, with words within parentheses treated as a unit.

• AND – this can be used to join sets of concepts together, narrowing the retrieved literature to articles that contain all concepts, for example the population or condition of interest and the intervention to be evaluated: (bipolar disorder OR bipolar depression) AND calcium channel blockers. However, if at least one term from each set of concepts is not identified from the title or abstract of an article, this article will not be identified by the search strategy. It is worth mentioning here that some databases can run the search also across the full texts. For example, ScienceDirect and most publishing houses allow this kind of search, which is much more comprehensive than abstract or title searches only.

• NOT – this operator, used less often, can focus a search strategy so that it does not retrieve specific literature, for example human studies NOT animal studies. However, in certain cases the NOT operator can be too restrictive, for example if excluding male gender from a population, using ‘NOT male’ would also mean that any articles about both males and females are not obtained by the search.

FIG 3 Example of Boolean operator concepts (the resulting search is the light red shaded area).

The conventions of each database should be checked before undertaking a literature search, as functions and operators may differ slightly between them (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Saunders and Attenburrow 2016b ). This is particularly relevant when using limits and filters. Figure 2 shows an example search strategy incorporating many of the concepts described above. The search strategy is taken from Cipriani et al ( Reference Cipriani, Zhou and Del Giovane 2016a ), but simplified to include only one intervention.

Search filters

A number of filters exist to focus a search, including language, date and study design or study focus filters. Language filters can restrict retrieval of articles to the English language, although if language is not an inclusion criterion it should not be restricted, to avoid language bias. Date filters can be used to restrict the search to literature from a specified period, for example if an intervention was only made available after a certain date. In addition, if good systematic reviews exist that are likely to capture all relevant literature (as advised by an information specialist), date restrictions can be used to search additional literature published after the date of that included in the systematic review. In the same way, date filters can be used to update a literature search since the last time it was conducted. Reviewing the literature should be a timely process (new and potentially relevant evidence is produced constantly) and updating the search is an important step, especially if collecting evidence to inform clinical decision-making, as publications in the field of medicine are increasing at an impressive rate (Barber Reference Barber, Corsi and Furukawa 2016 ). The filters chosen will depend on the research question and nature of evidence that is sought through the literature search and the guidelines of the individual database that is used.

- Google Scholar

Google Scholar allows basic Boolean operators to be used in strings of search terms. However, the search engine does not use standardised search terms that have been tagged as in traditional databases and therefore variations of keywords should always be searched. There are advantages and disadvantages to using a web search engine such as Google Scholar. Google Scholar searches the full text of an article for keywords and also searches a wider range of sources, such as conference proceedings and books, that are not found in traditional databases, making it a good resource to search for grey literature (Haddaway Reference Haddaway, Collins and Coughlin 2015 ). In addition, Google Scholar finds articles cited by other relevant articles produced in the search. However, variable retrieval of content (due to regular updating of Google algorithms and the individual's search history and location) means that search results are not necessarily reproducible and are therefore not in keeping with replicable search methods required by systematic reviews. Google Scholar alone has not been shown to retrieve more literature than other traditional databases discussed in this article and therefore should be used in addition to other sources (Bramer Reference Bramer, Giustini and Kramer 2016 ).

Citation searching

Once the search strategy has identified relevant literature, the reference lists in these sources can be searched. This is called citation searching or backward searching, and it can be used to see where particular research topics led others. This method is particularly useful if the search identifies systematic reviews or meta-analyses of a similar topic.

Conference abstracts

Conference abstracts are considered ‘grey literature’, i.e. literature that is not formally published in journals or books (Alberani Reference Alberani, De Castro Pietrangeli and Mazza 1990 ). Scherer and colleagues found that only 52.6% of all conference abstracts go on to full publication of results, and factors associated with publication were studies that had RCT designs and the reporting of positive or significant results (Scherer Reference Scherer, Langenberg and von Elm 2007 ). Therefore, failure to search relevant grey literature might miss certain data and bias the results of a review. Although conference abstracts are not indexed in most major electronic databases, they are available in databases such as BIOSIS Previews ( Box 1 ). However, as with many unpublished studies, these data did not undergo the peer review process that is often a tool for assessing and possibly improving the quality of the publication.

Searching trial registers and pharmaceutical websites

For reviews of trial interventions, a number of trial registers exist. ClinicalTrials.gov ( clinicaltrials.gov ) provides access to information on public and privately conducted clinical trials in humans. Results for both published and unpublished studies can be found for many trials on the register, in addition to information about studies that are ongoing. Searching each trial register requires a slightly different search strategy, but many of the basic principles described above still apply. Basic searches on ClinicialTrials.gov include searching by condition, specific drugs or interventions and these can be linked using Boolean operators: for example, (bipolar disorder OR manic depressive disorder) AND lithium. As mentioned above, parentheses can be used to build up search terms. More advanced searches allow one to specify further search fields such as the status of studies, study type and age of participants. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) hosts a database providing information about FDA-approved drugs, therapeutic products and devices ( www.fda.gov ). The database (with open access to anyone, not only in the USA) can be searched by the drug name, its active ingredient or its approval application number and, for most drugs approved in the past 20 years or so, a review of clinical trial results (some of which remain unpublished) used as evidence in the approval process is available. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) hosts a similar register for medicines developed for use in the European Union ( www.ema.europa.eu ). An internet search will show that many other national and international trial registers exist that, depending on the review question, may be relevant search sources. The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp ) provides access to a central database bringing a number of these national and international trial registers together. It can be searched in much the same way as ClinicalTrials.gov.

A number of pharmaceutical companies now share data from company-sponsored clinical trials. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) is transparent in the sharing of its data from clinical studies and hosts its own clinical study register ( www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com ). Eli-Lilly provides clinical trial results both on its website ( www.lillytrialguide.com ) and in external registries. However, other pharmaceutical companies, such as Wyeth and Roche, divert users to clinical trial results in external registries. These registries include both published and previously unpublished studies. Searching techniques differ for each company and hand-searching through documents is often required to identify studies.

Communication with authors

Direct communication with authors of published papers could produce both additional data omitted from published studies and other unpublished studies. Contact details are usually available for the corresponding author of each paper. Although high-quality reviews do make efforts to obtain and include unpublished data, this does have potential disadvantages: the data may be incomplete and are likely not to have been peer-reviewed. It is also important to note that, although reviewers should make every effort to find unpublished data in an effort to minimise publication bias, there is still likely to remain a degree of this bias in the studies selected for a systematic review.

Developing a literature search strategy is a key part of the systematic review process, and the conclusions reached in a systematic review will depend on the quality of the evidence retrieved by the literature search. Sources should therefore be selected to minimise the possibility of bias, and supplementary search techniques should be used in addition to electronic database searching to ensure that an extensive review of the literature has been carried out. It is worth reminding that developing a search strategy should be an iterative and flexible process (Higgins Reference Higgins and Green 2011 ), and only by conducting a search oneself will one learn about the vast literature available and how best to capture it.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah Stockton for her help in drafting this article. Andrea Cipriani is supported by the NIHR Oxford cognitive health Clinical Research Facility.

Select the single best option for each question stem

a an explicit and replicable method used to retrieve all available literature pertaining to a specific topic to answer a defined question

b a descriptive overview of selected literature

c an initial impression of a topic which is understood more fully as a research study is conducted

d a method of gathering opinions of all clinicians or researchers in a given field

e a step-by-step process of identifying the earliest published literature through to the latest published literature.

a does not need to be specified in advance of a literature search

b does not need to be reported in a systematic literature review

c defines which sources of literature are to be searched, but not how a search is to be carried out

d defines how relevant literature will be identified and provides a basis for the search strategy

e provides a timeline for searching each electronic database or unpublished literature source.

a the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

d the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

e the British Nursing Index.

a bipolar disorder OR treatment

b bipolar* OR treatment

c bipolar disorder AND treatment

d bipolar disorder NOT treatment

e (bipolar disorder) OR (treatment).

a publication bias

b funding bias

c language bias

d outcome reporting bias

e selection bias.

MCQ answers

1 a 2 d 3 b 4 c 5 a

FIG 2 Example of a search strategy about bipolar disorder using MEDLINE (Cipriani 2016a). The strategy follows the PICO framework and includes MeSH terms, free-text keywords and a number of other techniques, such as truncation, that have been outlined in this article. Numbers in bold give the number of citations retrieved by each search.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 24, Issue 2

- Lauren Z. Atkinson and Andrea Cipriani

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2017.3

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Academic Process

- Systematic Reviews

- Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches

Systematic Reviews: Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches

Created by health science librarians.

- Step 1: Complete Pre-Review Tasks

- Step 2: Develop a Protocol

About Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches

Partner with a librarian, systematic searching process, choose a few databases, search with controlled vocabulary and keywords, acknowledge outdated or offensive terminology, helpful tip - building your search, use nesting, boolean operators, and field tags, build your search, translate to other databases and other searching methods, document the search, updating your review.

- Searching FAQs

- Step 4: Manage Citations

- Step 5: Screen Citations

- Step 6: Assess Quality of Included Studies

- Step 7: Extract Data from Included Studies

- Step 8: Write the Review

Check our FAQ's

Email us

Call (919) 962-0800

Make an appointment with a librarian

Request a systematic or scoping review consultation

Search the FAQs

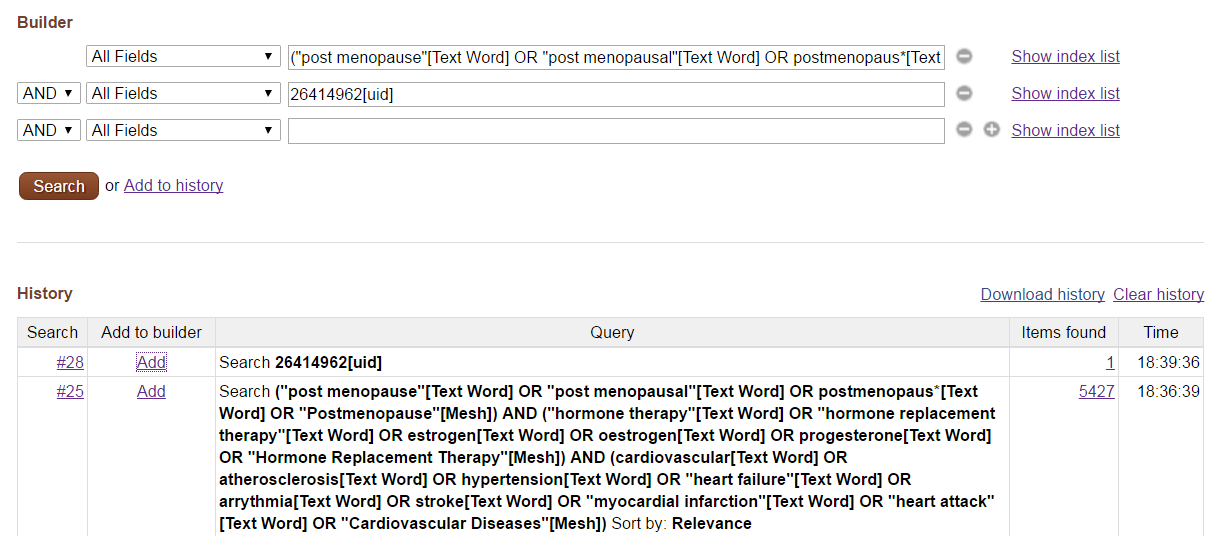

In Step 3, you will design a search strategy to find all of the articles related to your research question. You will:

- Define the main concepts of your topic

- Choose which databases you want to search

- List terms to describe each concept

- Add terms from controlled vocabulary like MeSH

- Use field tags to tell the database where to search for terms

- Combine terms and concepts with Boolean operators AND and OR

- Translate your search strategy to match the format standards for each database

- Save a copy of your search strategy and details about your search

There are many factors to think about when building a strong search strategy for systematic reviews. Librarians are available to provide support with this step of the process.

Click an item below to see how it applies to Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches.

Reporting your review with PRISMA

For PRISMA, there are specific items you will want to report from your search. For this step, review the PRISMA-S checklist.

- PRISMA-S for Searching

- Specify all databases, registers, websites, organizations, reference lists, and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used.

- For information on how to document database searches and other search methods on your PRISMA flow diagram, visit our FAQs "How do I document database searches on my PRISMA flow diagram?" and "How do I document a grey literature search for my PRISMA flow diagram?"

Managing your review with Covidence

For this step of the review, in Covidence you can:

- Document searches in Covidence review settings so all team members can view

- Add keywords from your search to be highlighted in green or red while your team screens articles in your review settings

How a librarian can help with Step 3

When designing and conducting literature searches, a librarian can advise you on :

- How to create a search strategy with Boolean operators, database-specific syntax, subject headings, and appropriate keywords

- How to apply previously published systematic review search strategies to your current search

- How to test your search strategy's performance

- How to translate a search strategy from one database's preferred structure to another

The goal of a systematic retrieve is to find all results that are relevant to your topic. Because systematic review searches can be quite extensive and retrieve large numbers of results, an important aspect of systematic searching is limiting the number of irrelevant results that need to be screened. Librarians are experts trained in literature searching and systematic review methodology. Ask us a question or partner with a librarian to save time and improve the quality of your review. Our comparison chart detailing two tiers of partnership provides more information on how librarians can collaborate with and contribute to systematic review teams.

Search Process

- Use controlled vocabulary, if applicable

- Include synonyms/keyword terms

- Choose databases, websites, and/or registries to search

- Translate to other databases

- Search using other methods (e.g. hand searching)

- Validate and peer review the search

Databases can be multidisciplinary or subject specific. Choose the best databases for your research question. Databases index various journals, so in order to be comprehensive, it is important to search multiple databases when conducting a systematic review. Consider searching databases with more diverse or global coverage (i.e., Global Index Medicus) when appropriate. A list of frequently used databases is provided below. You can access UNC Libraries' full listing of databases on the HSL website (arranged alphabetically or by subject ).

| Database | Scope |

|---|---|

Generally speaking, when literature searching, you are not searching the full-text article. Instead, you are searching certain citation data fields, like title, abstract, keyword, controlled vocabulary terms, and more. When developing a literature search, a good place to start is to identify searchable concepts of the research question, and then expand by adding other terms to describe those concepts. Read below for more information and examples on how to develop a literature search, as well as find tips and tricks for developing more comprehensive searches.

Identify search concepts and terms for each

Start by identifying the main concepts of your research question. If unsure, try using a question framework to help identify the main searchable concepts. PICO is one example of a question framework and is used specifically for clinical questions. If your research question doesn't fit into the PICO model well, view other examples of question frameworks and try another!

View our example in PICO format

Question: for patients 65 years and older, does an influenza vaccine reduce the future risk of pneumonia.

| Element | Example |

|---|---|

|

atient(s) / opulation(s) |

patients 65 years and older |

|

ntervention(s) |

influenza vaccine |

|

omparison(s) |

not applicable |

|

utcome(s) |

pneumonia

|

Controlled Vocabulary

Controlled vocabulary is a set of terminology assigned to citations to describe the content of each reference. Searching with controlled vocabulary can improve the relevancy of search results. Many databases assign controlled vocabulary terms to citations, but their naming schema is often specific to each database. For example, the controlled vocabulary system searchable via PubMed is MeSH, or Medical Subject Headings. More information on searching MeSH can be found on the HSL PubMed Ten Tips Legacy Guide .

Note: Controlled vocabulary may be outdated, and some databases allow users to submit requests to update terminology.

View Controlled Vocabulary for our example PICO

As mentioned above, databases with controlled vocabulary often use their own unique system. A listing of controlled vocabulary systems by database is shown below.

| Database | Controlled Vocabulary | Indicated By | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed (MEDLINE) | Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) | [MeSH] | "Influenza Vaccines"[Mesh] |

| Embase | EMTREE | /exp | 'influenza vaccine'/exp |

| CINAHL | CINAHL Headings | MH or MM | (MH "Influenza Vaccine") |

| PsycINFO | APA Thesaurus | DE | DE "Influenza" |

| Sociological Abstracts | Thesaurus of Sociological Indexing Terms | MAINSUBJECT.EXACT | MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Influenza") |

Keyword Terms

Not all citations are indexed with controlled vocabulary terms, however, so it is important to combine controlled vocabulary searches with keyword, or text word, searches.

Authors often write about the same topic in varied ways and it is important to add these terms to your search in order to capture most of the literature. For example, consider these elements when developing a list of keyword terms for each concept:

- American versus British spelling

- hyphenated terms

- quality of life

- satisfaction

- vaccination

- influenza vaccination

There are several resources to consider when searching for synonyms. Scan the results of preliminary searches to identify additional terms. Look for synonyms, word variations, and other possibilities in Wikipedia, other encyclopedias or dictionaries, and databases. For example, PubChem lists additional drug names and chemical compounds.

Display Controlled Vocabulary and Keywords for our example PICO

| PICO Element | Example | Controlled Vocabulary | Synonyms/Keyword Terms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

atient(s) / opulation(s) |

patients 65 years and older |

"Aged"[Mesh] | elder elders elderly aged aging geriatric geriatrics gerontology gerontological | senior citizen senior citizens older adult older adults older individuals older patients older people older persons advancing age |

|

ntervention(s) |

influenza vaccine |

"Influenza Vaccines"[Mesh] | influenza vaccines flu vaccine flu vaccines influenza virus vaccine influenza virus vaccines ((flu OR influenza) AND (vaccine OR vaccines OR vaccination OR immunization)) | |

|

omparison(s) |

not applicable |

- |

- | |

|

utcome(s) |

pneumonia |

"Pneumonia"[Mesh] | pneumonias pulmonary inflammation | |

Combining controlled vocabulary and text words in PubMed would look like this:

"Influenza Vaccines"[Mesh] OR "influenza vaccine" OR "influenza vaccines" OR "flu vaccine" OR "flu vaccines" OR "flu shot" OR "flu shots" OR "influenza virus vaccine" OR "influenza virus vaccines"

Social and cultural norms have been rapidly changing around the world. This has led to changes in the vocabulary used, such as when describing people or populations. Library and research terminology changes more slowly, and therefore can be considered outdated, unacceptable, or overly clinical for use in conversation or writing.

For our example with people 65 years and older, APA Style Guidelines recommend that researchers use terms like “older adults” and “older persons” and forgo terms like “senior citizens” and “elderly” that connote stereotypes. While these are current recommendations, researchers will recognize that terms like “elderly” have previously been used in the literature. Therefore, removing these terms from the search strategy may result in missed relevant articles.

Research teams need to discuss current and outdated terminology and decide which terms to include in the search to be as comprehensive as possible. The research team or a librarian can search for currently preferred terms in glossaries, dictionaries, published guidelines, and governmental or organizational websites. The University of Michigan Library provides suggested wording to use in the methods section when antiquated, non-standard, exclusionary, or potentially offensive terms are included in the search.

Check the methods sections or supplementary materials of published systematic reviews for search strategies to see what terminology they used. This can help inform your search strategy by using MeSH terms or keywords you may not have thought of. However, be aware that search strategies will differ in their comprehensiveness.

You can also run a preliminary search for your topic, sort the results by Relevance or Best Match, and skim through titles and abstracts to identify terminology from relevant articles that you should include in your search strategy.

Nesting is a term that describes organizing search terms inside parentheses. This is important because, just like their function in math, commands inside a set of parentheses occur first. Parentheses let the database know in which order terms should be combined.

Always combine terms for a single concept inside a parentheses set. For example:

( "Influenza Vaccines"[Mesh] OR "influenza vaccine" OR "influenza vaccines" OR "flu vaccine" OR "flu vaccines" OR "flu shot" OR "flu shots" OR "influenza virus vaccine" OR "influenza virus vaccines" )

Additionally, you may nest a subset of terms for a concept inside a larger parentheses set, as seen below. Pay careful attention to the number of parenthesis sets and ensure they are matched, meaning for every open parentheses you also have a closed one.

( "Influenza Vaccines"[Mesh] OR "influenza vaccine" OR "influenza vaccines" OR "flu vaccine" OR "flu vaccines" OR "flu shot" OR "flu shots" OR "influenza virus vaccine" OR "influenza virus vaccines" OR (( flu OR influenza ) AND ( vaccine OR vaccines OR vaccination OR immunization )))

Boolean operators

Boolean operators are used to combine terms in literature searches. Searches are typically organized using the Boolean operators OR or AND. OR is used to combine search terms for the same concept (i.e., influenza vaccine). AND is used to combine different concepts (i.e., influenza vaccine AND older adults AND pneumonia). An example of how Boolean operators can affect search retrieval is shown below. Using AND to combine the three concepts will only retrieve results where all are present. Using OR to combine the concepts will retrieve results that use all separately or together. It is important to note that, generally speaking, when you are performing a literature search you are only searching the title, abstract, keywords and other citation data. You are not searching the full-text of the articles.

The last major element to consider when building systematic literature searches are field tags. Field tags tell the database exactly where to search. For example, you can use a field tag to tell a database to search for a term in just the title, the title and abstract, and more. Just like with controlled vocabulary, field tag commands are different for every database.

If you do not manually apply field tags to your search, most databases will automatically search in a set of citation data points. Databases may also overwrite your search with algorithms if you do not apply field tags. For systematic review searching, best practice is to apply field tags to each term for reproducibility.

For example:

("Influenza Vaccines"[Mesh] OR "influenza vaccine"[tw] OR "influenza vaccines"[tw] OR "flu vaccine"[tw] OR "flu vaccines"[tw] OR "flu shot"[tw] OR "flu shots"[tw] OR "influenza virus vaccine"[tw] OR "influenza virus vaccines"[tw] OR ((flu[tw] OR influenza[tw]) AND (vaccine[tw] OR vaccines[tw] OR vaccination[tw] OR immunization[tw])))

View field tags for several health databases

| Database | Select Field Tags | Example |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed (MEDLINE) | ||

| Embase | ||

| CINAHL, PsycInfo, & other EBSCO databases | ||

| Sociological Abstracts & other Proquest databases |

For more information about how to use a variety of databases, check out our guides on searching.

- Searching PubMed guide Guide to searching Medline via the PubMed database

- Searching Embase guide Guide to searching Embase via embase.com

- Searching Scopus guide Guide to searching Scopus via scopus.com

- Searching EBSCO Databases guide Guide to searching CINAHL, PsycInfo, Global Health, & other databases via EBSCO

Combining search elements together

Organizational structure of literature searches is very important. Specifically, how terms are grouped (or nested) and combined with Boolean operators will drastically impact search results. These commands tell databases exactly how to combine terms together, and if done incorrectly or inefficiently, search results returned may be too broad or irrelevant.

For example, in PubMed:

(influenza OR flu) AND vaccine is a properly combined search and it produces around 50,000 results.

influenza OR flu AND vaccine is not properly combined. Databases may read it as everything about influenza OR everything about (flu AND vaccine), which would produce more results than needed.

We recommend one or more of the following:

- put all your synonyms together inside a set of parentheses, then put AND between the closing parenthesis of one set and the opening parenthesis of the next set

- use a separate search box for each set of synonyms

- run each set of synonyms as a separate search, and then combine all your searches

- ask a librarian if your search produces too many or too few results

View the proper way to combine MeSH terms and Keywords for our example PICO

Question: for patients 65 years and older, does an influenza vaccine reduce the future risk of pneumonia .

| PICO Element | Example | Controlled Vocabulary (Database-Specific) | Synonyms/Keyword Terms | Sample Search Strategies (Combine Controlled Vocabulary & Keywords) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

atient(s) / opulation(s) |

patients 65 years and older |

"Aged"[Mesh] | elder elders elderly aged aging geriatric geriatrics gerontology gerontological | senior citizen senior citizens older adult older adults older patients advancing age |

(“Aged”[Mesh] OR elder[tiab] OR elders[tiab] OR elderly[tw] OR aged[tw] OR aging[tiab] OR “older adult”[tw] OR “older adults”[tw] OR “older patients”[tw] OR “advancing age”[tiab] OR geriatric[tw] OR geriatrics[tw] OR gerontology[tw] OR gerontological[tw] OR “senior citizen”[tw] OR “senior citizens”[tw]) |

|

ntervention(s) |

influenza vaccine |

"Influenza Vaccines"[Mesh] | influenza vaccines flu vaccine flu vaccines influenza virus vaccine influenza virus vaccines (flu OR influenza) AND (vaccine OR vaccines OR vaccination OR immunization) |

("Influenza Vaccines"[Mesh] OR “influenza vaccines”[tw] OR “flu vaccine”[tw] OR “flu vaccines”[tw] OR “flu shot”[tw] OR “flu shots”[tw] OR “influenza virus vaccine”[tw] OR “influenza virus vaccines”[tw] OR ((flu[tw] OR influenza[tw]) AND (vaccine[tw] OR vaccines[tw] OR vaccination[tw] OR immunization[tw]))) | |

|

omparison(s) |

not applicable |

- |

- |

- | |

|

utcome(s) |

pneumonia |

"Pneumonia"[Mesh] | pneumonias pulmonary inflammation |

("Pneumonia"[Mesh] OR pneumonia[tw] OR pneumonias[tw] OR “pulmonary inflammation”[tw]) | |

Translating search strategies to other databases

Databases often use their own set of terminology and syntax. When searching multiple databases, you need to adjust the search slightly to retrieve comparable results. Our sections on Controlled Vocabulary and Field Tags have information on how to build searches in different databases. Resources to help with this process are listed below.

- Polyglot search A tool to translate a PubMed or Ovid search to other databases

- Search Translation Resources (Cornell) A listing of resources for search translation from Cornell University

- Advanced Searching Techniques (King's College London) A collection of advanced searching techniques from King's College London

Other searching methods

Hand searching.

Literature searches can be supplemented by hand searching. One of the most popular ways this is done with systematic reviews is by searching the reference list and citing articles of studies included in the review. Another method is manually browsing key journals in your field to make sure no relevant articles were missed. Other sources that may be considered for hand searching include: clinical trial registries, white papers and other reports, pharmaceutical or other corporate reports, conference proceedings, theses and dissertations, or professional association guidelines.

Searching grey literature

Grey literature typically refers to literature not published in a traditional manner and often not retrievable through large databases and other popular resources. Grey literature should be searched for inclusion in systematic reviews in order to reduce bias and increase thoroughness. There are several databases specific to grey literature that can be searched.

- Open Grey Grey literature for Europe

- OAIster A union catalog of millions of records representing open access resources from collections worldwide

- Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature (CADTH) From CADTH, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Grey Matters is a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. The MS Word document covers a grey literature checklist, including national and international health technology assessment (HTA) web sites, drug and device regulatory agencies, clinical trial registries, health economics resources, Canadian health prevalence or incidence databases, and drug formulary web sites.

- Duke Medical Center Library: Searching for Grey Literature A good online compilation of resources by the Duke Medical Center Library.

Systematic review quality is highly dependent on the literature search(es) used to identify studies. To follow best practices for reporting search strategies, as well as increase reproducibility and transparency, document various elements of the literature search for your review. To make this process more clear, a statement and checklist for reporting literature searches has been developed and and can be found below.

- PRISMA-S: Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews

- Section 4.5 Cochrane Handbook - Documenting and reporting the search process

At a minimum, document and report certain elements, such as databases searched, including name (i.e., Scopus) and platform (i.e. Elsevier), websites, registries, and grey literature searched. In addition, this also may include citation searching and reaching out to experts in the field. Search strategies used in each database or source should be documented, along with any filters or limits, and dates searched. If a search has been updated or was built upon previous work, that should be noted as well. It is also helpful to document which search terms have been tested and decisions made for term inclusion or exclusion by the team. Last, any peer review process should be stated as well as the total number of records identified from each source and how deduplication was handled.

If you have a librarian on your team who is creating and running the searches, they will handle the search documentation.

You can document search strategies in word processing software you are familiar with like Microsoft Word or Excel, or Google Docs or Sheets. A template, and separate example file, is provided below for convenience.

- Search Strategy Documentation Template

- Search Strategy Documentation Example

*Some databases like PubMed are being continually updated with new technology and algorithms. This means that searches may retrieve different results than when originally run, even with the same filters, date limits, etc.

When you decide to update a systematic review search, there are two ways of identifying new articles:

1. rerun the original search strategy without any changes. .

Rerun the original search strategy without making any changes. Import the results into your citation manager, and remove all articles duplicated from the original set of search results.

2. Rerun the original search strategy and add an entry date filter.

Rerun the original search strategy and add a date filter for when the article was added to the database ( not the publication date). An entry date filter will find any articles added to the results since you last ran the search, unlike a publication date filter, which would only find more recent articles.

Some examples of entry date filters for articles entered since December 31, 2021 are:

- PubMed: AND ("2021/12/31"[EDAT] : "3000"[EDAT])

- Embase: AND [31-12-2021]/sd

- CINAHL: AND EM 20211231-20231231

- PsycInfo: AND RD 20211231-20231231

- Scopus: AND LOAD-DATE AFT 20211231

Your PRISMA flow diagram

For more information about updating the PRISMA flow diagram for your systematic review, see the information on filling out a PRISMA flow diagram for review updates on the Step 8: Write the Review page of the guide.

- << Previous: Step 2: Develop a Protocol

- Next: Step 4: Manage Citations >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 3:24 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/systematic-reviews

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Creating the Search

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

Before You Start

Step 1: structure your concepts, step 2: brainstorm keywords for each concept, step 3: determine appropriate controlled vocabulary terms, step 4: put it all together, step 5: refine your strategy.

- Search Filters and Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing and Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Explicitly state your research question, determine which databases you will search, and determine your inclusion/exclusion criteria for studies that you find. Here is some information on writing a protocol for your systematic review study . You might want to search PROSPERO , a database of protocols, to make sure that no one else is currently working on a review on the same topic. You can also submit your protocol to PROSPERO.

- Break down your research question into smaller concepts in order to make the next few steps manageable.

| Patient or population | |||

| Intervention or indicator | |||

| Comparison or control | |||

| Outcome |

| Post menopausal women | |||

| Hormone replacement therapy | |||

| No therapy | |||

| Cardiovascular disease |

| Post-menopausal women | |||

| Hormone replacement therapy | |||

| Cardiovascular disease |