Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics

- > Volume 53 Issue 3

- > US Consumers’ Online Shopping Behaviors and Intentions...

Article contents

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Implications and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Financial support, conflict of interests, data availability, us consumers’ online shopping behaviors and intentions during and after the covid-19 pandemic.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 31 August 2021

A study of 1,558 US households in June 2020 evaluated utilization of online grocery shopping during the COVID-19 pandemic, influences on utilization, and plans for future online grocery shopping. Nearly 55 percent of respondents shopped online in June 2020; 20 percent were first-timers. Cragg model estimates showed influences on online shopping likelihood and frequency included demographics, employment, and prior online shopping. Illness concerns increased likelihood, while food shortage concerns increased frequency of online shopping. A multinomial probit suggested 58 percent respondents planned to continue online grocery shopping regardless of pandemic conditions.

1. Introduction

1.1. the covid-19 pandemic and policy response.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led many American consumers to rapidly and sometimes dramatically change their food shopping behaviors in response to changes in policy, and personal or public health concerns. In March 2020 as the virus started spreading widely in the United States (US), state and local governments began issuing orders to close restaurants to in-person dining to mitigate the spread of the virus. In response to these conditions, many consumers responded by shifting their food expenditures away from food service (e.g. restaurants and eating establishments) to food retailers (Kowitt and Lambert, Reference Kowitt and Lambert 2020 ). In some cases, consumers stockpiled groceries due to concerns about supply chain disruptions and shortages (Acosta, Reference Acosta 2020 ). Part of this stockpiling may also have been due to averting behaviors, as some consumers preferred to shop in-store less frequently, thus reducing the number of their potential exposures. Some of these increased food expenditures were conducted through online purchases, which showed a significant increase in utilization from the early months of the pandemic through the next stage of the pandemic policy response in April when states started issuing stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders (Redman, Reference Redman 2020 b).

From March 1 to May 31, 2020, 42 states and territories issued stay-at-home orders that covered about 73 percent of US counties (Moreland et al., Reference Moreland, Herlihy, Tynan, Sunshine, McCord, Hilton, Poovey, Werner, Jones, Fulmer, Gundlapalli, Strosnider, Potvien, García, Honeycutt and Baldwin 2020 ). These orders continued the closure of restaurants to in-person dining, while keeping many food retailers open, and asked households to limit their activity outside of their home. The duration of the stay-at-home orders varied from state to state, but they represented a significant disruption to the way households typically acquire food.

As consumers entered into a new phase of pandemic policies marked by the end of stay-at-home orders during the late spring and early summer, questions have arisen as to how consumers will navigate this new environment and which behaviors adopted during the earliest months of the pandemic will endure (Foster and Mundell, Reference Foster and Mundell 2020 ). Even as state policies changed, consumers have continued to encounter some elements of the pandemic including shortages of food at retailers and the concern of contracting the virus while making in-person grocery shopping. Thus, the pandemic likely continued to influence shopper behavior into the summer of 2020. Consumers likely adopted some behaviors, such as online grocery shopping, that they may continue even beyond the end of the pandemic. Therefore, this study not only investigates determinants of online grocery shopping, including delivery and curbside pickup services, in June 2020, but also intentions among online grocery shoppers for future online grocery shopping. The influences on plans for future online shopping are measured, given that the scenarios the pandemic could continue or subside. Hence, the study provides insights into how shoppers may behave with regard to online shopping in the post-pandemic era. The study uses results from an original national US survey administered in July 2020.

This study complements the current literature in two ways. First, we incorporate both previously explored and pandemic-specific variables into our model of current online grocery store use. Prior research has shown that age, income, and the presence of children in the household influence the decision to the utilization of online grocery shopping (Etumnu et al. Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 , Hansen, Reference Hansen 2005 ; Hansen, Reference Hansen 2005 ; Jaller and Pawha, Reference Jaller and Pahwa 2020 ; Melis et al., Reference Melis, Campo, Lamey and Breugelmans 2016 ; Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ). However, it is unclear how the pandemic has influenced the consumer decision-making process. While Ellison et al. ( Reference Ellison, McFadden, Rickard and Wilson 2020 ) documented an increase in online grocery shopping, their primary focus was on changes in purchasing behavior and not the decision to use online grocery shopping. Therefore, we have included pandemic-specific measures to capture how risk perceptions about COVID-19 or food supply chain disruptions influence the choice of online grocery shopping and frequency of online shopping.

Second, we investigate consumers’ anticipated use of online shopping in the future. We consider the possibility that online grocery shopping will persist only during the pandemic, that it will continue regardless of the pandemic, or that it will not be continued in the future. We examine the prevalence of each behavior and then investigate possible determinants of future online grocery shopping using a multinomial logistic regression. Understanding the potential future grocery shopping behavior and its determinants could assist grocers and retailers to reidentify their marketing strategies and enhance online shopping service to better serve online grocery shoppers.

The first section of this paper provides a brief literature overview of studies of online grocery shopping both pre-pandemic and in the pandemic-shaped grocery markets. This literature review helps define hypotheses about how shopper demographics and attitudes may influence online grocery shopping, frequency of online grocery purchases during the pandemic, and plans to continue online grocery shopping. Following the literature review and hypotheses development, the next section presents information about the survey and data collection and model estimations. Results and policy implications are discussed next, along with conclusions.

1.2. Prior Studies of Online Grocery Shopping and Behaviors During the Pandemic

1.2.1. online grocery shopping patterns pre-pandemic.

Several studies have examined the effects of shopper demographics and attitudes on online grocery shopping. Younger shoppers are more likely to use online grocery shopping, perhaps because they are more familiar and comfortable with online shopping in general and related technology (Etumnu et al., Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Farag et al., Reference Farag, Schwanen, Dijst and Faber 2007 b; Hiser, Nayga, and Capps, Reference Hiser, Nayga and Capps 1999 ; Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ). While some studies have found positive influence of female gender on online grocery shopping (Jaller and Pawha, Reference Jaller and Pahwa 2020 ), others have found the opposite (Etumnu et al., Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Farag et al. Reference Farag, Schwanen, Dijst and Faber 2007 b). Prior studies have suggested that presence of younger children has a positive effect on online grocery shopping adoption (Etumnu et al. Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 , Hansen, Reference Hansen 2005 ; Jaller and Pawha, Reference Jaller and Pahwa 2020 , Melis et al., Reference Melis, Campo, Lamey and Breugelmans 2016 ), indicating food shoppers with accompanying children may find in-store trips more time-consuming and challenging than those without children.

Studies have found positive effects of household income (Hansen, Reference Hansen 2005 ) or full-time employment in the household (Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ) on online grocery shopping. Greater likelihood of online grocery shopping has also been associated with higher levels of education (Etumnu et al., Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Hiser, Nayga, and Capps, Reference Hiser, Nayga and Capps 1999 ; Jaller and Pawha, Reference Jaller and Pahwa 2020 ; Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ). Melis et al. ( Reference Melis, Campo, Lamey and Breugelmans 2016 ) found that, if shoppers lived farther from a brick-and-mortar store, they were more likely to spend a larger share of their grocery spending at the online chain. They posited that shoppers would experience relatively higher transportation costs and thus were more inclined to shift more of their purchases to the online store. Findings by Melis et al. ( Reference Melis, Campo, Lamey and Breugelmans 2016 ) might suggest that urban consumers would be less likely to choose online shopping over brick-and-mortar shopping. However, this finding might not hold in more rural areas where there are limited online grocery shopping opportunities. But, with large chains such as WalMart offering online shopping with curbside pickup and Amazon delivery of grocery items even in rural areas, these limitations may be less than in the past (Germain, Reference Germain 2020 ).

Researchers have also investigated the relationship between in-store shopping and online shopping. Farag, Krizek, and Dijst ( Reference Farag, Krizek and Dijst 2007 a) found Dutch online buyers make more shopping trips than non-online buyers and have a shorter duration of shopping trips. Their results were suggestive of a complementary relationship between online buying and in-store shopping. Furthermore, Pozzi ( Reference Pozzi 2013 ) found only limited cannibalization of traditional brick-and-mortar store grocery sales by online sales.

1.2.2. Influences of Attitudes and Pre-Pandemic Lifestyles

Several studies have examined the influence of convenience and perceived risks on online grocery shopping (Campo and Breugelmans Reference Campo and Breugelmans 2015 ; Melis et al. Reference Melis, Campo, Lamey and Breugelmans 2016 ; Ramus and Nielsen, Reference Ramus and Nielsen 2005 ; Rohm and Swaminathan, Reference Rohm and Swaminathan 2004 ; Verhoef and Langerak, Reference Verhoef and Langerak 2001 ). Verhoef and Langerak ( Reference Verhoef and Langerak 2001 ) found that consumers who believed the reduction in the physical efforts of grocery shopping were an important advantage associated with online grocery shopping. Rohm and Swaminathan ( Reference Rohm and Swaminathan 2004 ) found that store-oriented shoppers who derived satisfaction from immediate product possession and contact shopping were much less likely to shop online than were convenience shoppers. Campo and Breugelmans ( Reference Campo and Breugelmans 2015 ) noted that the vast majority of online grocery shoppers were actually multichannel shoppers who visited both online and offline, brick-and-mortar, and grocery stores. Melis et al. ( Reference Melis, Campo, Lamey and Breugelmans 2016 ) found that consumers who had moderate time constraints, indicated by frequency of shopping trips, were more likely to adopt the online channel for grocery retailers. Ramus and Nielsen ( Reference Ramus and Nielsen 2005 ) found that shoppers perceived internet grocery shopping to be convenient, but more likely to result in purchasing poorer quality products that they would either have to accept or return.

A few studies have examined frequency of online grocery shopping. Hansen ( Reference Hansen 2007 ) found that increased utilization of online grocery shopping was associated with the perception of increased physical effort of in-store shopping and decreased perception of the complexity of online shopping, internet grocery risk, and enjoyment of shopping in-store. Hand et al. ( Reference Hand, Dall’Olmo Riley, Rettie, Harris and Singh 2009 ) found that situational factors, for example, birth of a child, health problems, or family circumstances, often were precipitating factors that influenced shoppers to buy groceries online. However, once these precipitating factors were gone, the shoppers tended to return to brick-and-mortar grocery shopping. These results elicit the question of whether those who have initiated or increased their online grocery shopping during the pandemic will plan to continue online shopping or revert to prior brick-and-mortar grocery shopping patterns after the pandemic conditions have eased. Furthermore, some shoppers may plan to continue online grocery shopping only as long as the pandemic conditions prevail. However, this represents an empirical question yet to be answered.

1.2.3. Online and In-Store Shopping During the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the first few months of the pandemic, several changes in food shopping behaviors were found. In a study of Spanish consumers (Laguna et al., Reference Laguna, Fizman, Puerta, Chaya and Tarrega 2020 ), no changes in percentages of where consumers said they mainly purchased their foods (supermarkets, small shops, or online) were found; however, consumers reduced their frequency of shopping trips. While there was not a shift toward online shopping found in their study, the decrease in frequency of shopping suggests averting behaviors. Another study found consumer in the United States and China had changed their food purchase behaviors toward more use of takeout and delivery orders (Dou et al., Reference Dou, Stefanovsi, Galligan, Lindem, Rozin, Chen and Chao 2020 ). In addition, some studies showed that grocery shopping online increased with social distancing measures and concerns about shopping in crowded grocery stores (Ellison et al., Reference Ellison, McFadden, Rickard and Wilson 2020 ; Melo, Reference Melo 2020 ). Melo ( Reference Melo 2020 ) noted during the first few months of the pandemic certain foods were stockpiled by consumers.

Grashius and Skevas ( Reference Grashius and Skevas 2020 ) used a choice experiment to determine how online shopping attributes and COVID-19 conditions might influence preferences for online grocery shopping. They also examined how the spread of COVID-19 may impact consumer preferences. Respondents who were presented with the hypothetical case where COVID-19 was spreading at an increasing rate had the most disutility of shopping in-store. However, where COVID-19 was hypothetically spreading at a decreasing rate, consumer preferences for the home delivery over other methods were not as pronounced. Hence, they postulated that consumer online shopping behavior is motivated at least in part by concerns of shopping inside grocery stores. Their results suggest that when pandemic conditions subside, many online shoppers will choose to return to brick-and-mortar shopping.

The possibility that concerns regarding COVID-19 influence consumer behavior was also investigated by Goolsbee and Syverson ( Reference Goolsbee and Syverson 2020 ) who used cell phone records to track customer visits to 2.25 million businesses across 110 industries during the early months of the pandemic. They found that overall consumer traffic fell by 60 percentage points, but legal restrictions explained only about 7 percentage points of this decline, while individual choices were more explanatory of the decline. They noted, however, that shutdown orders did reallocate consumers from restaurants and bars toward groceries and other food sellers. Hence, during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, a portion of sales gains online may be attributable to both concerns regarding COVID-19 and declines in food-away-from-home purchases.

2. Methodology

2.1. survey and data collection.

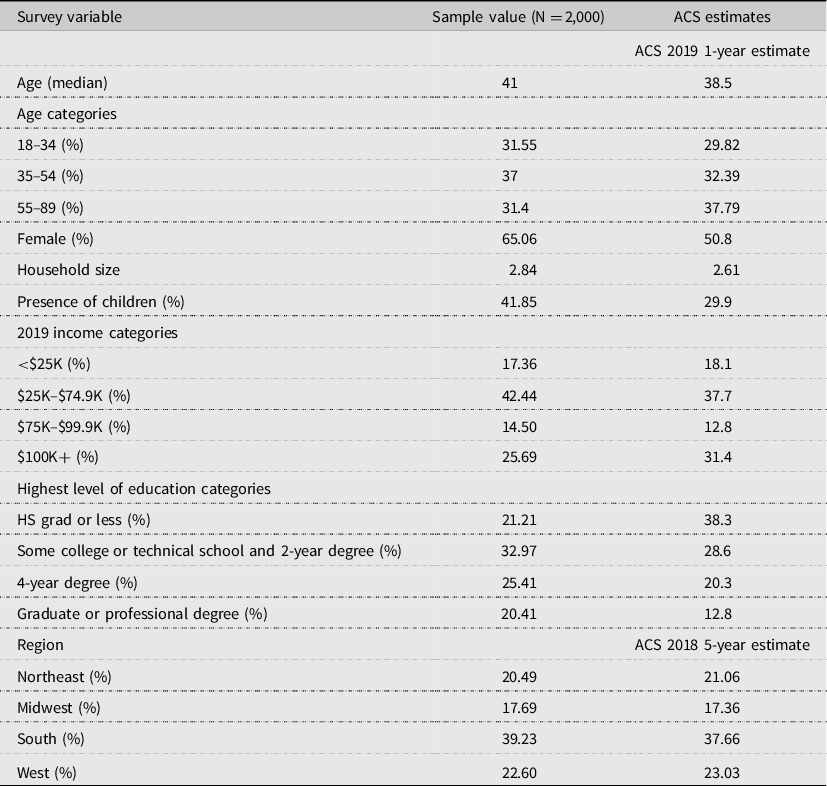

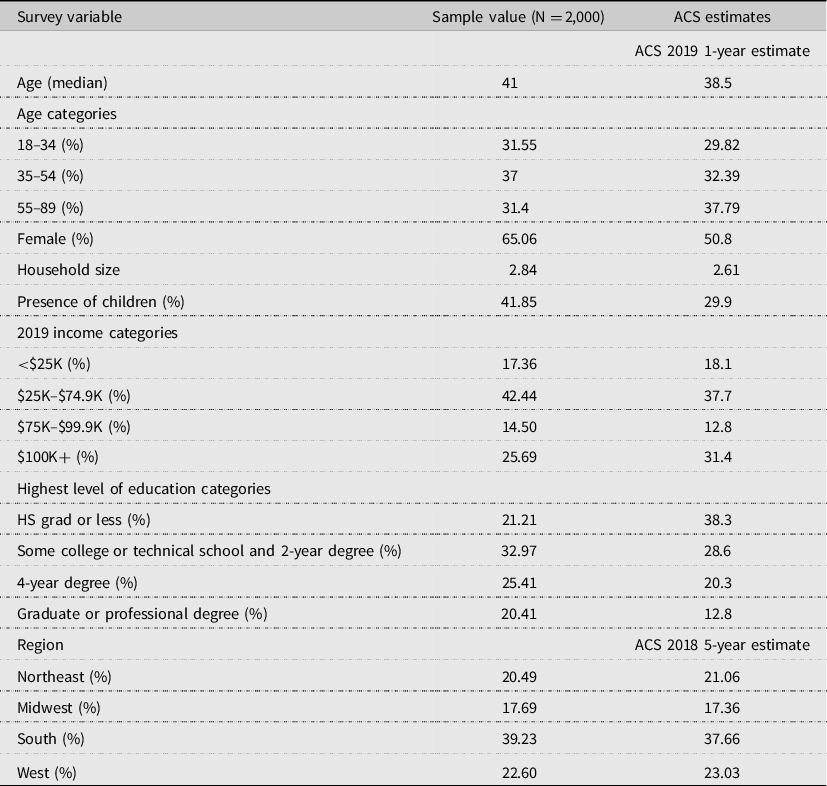

The data for this study were collected via an online survey through the Qualtrics survey platform in July 2020. The survey panel consisted of US primary household food shoppers (person primarily responsible for most of the food shopping in their household) aged 18 years and over, who had lived in the same state since February 1, 2020. Prior to the survey being fielded, a pretest of 50 respondents was conducted and the survey was deemed suitable for broader distribution. The sample panel was drawn by Qualtrics to reflect the distribution of US households according to the American Community Survey (ACS) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 ) based on their 2019 income, age, and geographical region (i.e. Northeast, Midwest, West, and South). Qualtrics solicited responses until a total of 2,000 responses were received from respondents who met the qualifications described above while ensuring the age, income, and regional quotas were met. Table 1 displays sample averages for several demographic and household variables compared with ACS estimates for the US population. As can be seen in Table 1 , the sample respondent is more likely to be female than the US average. This may be attributed to the primary shopper inclusion criteria because a higher percentage of primary food shoppers are female (Schaefer, Reference Schaefer 2019 ). Also, our sample has a higher percentage of college graduates than the US average. The sample average household size was larger than the US average and a higher percentage have children under the age of 18 years compared with the US average.

Table 1. Survey sample demographics compared with US American Community Survey (ACS) estimates

The survey instrument consisted of several sections including methods of acquiring food in June 2020 (online or in-person grocery store, in-person or takeaway from restaurants, and other sources), food expenditures, COVID-19 experiences and attitudes, and other demographic and household questions. Appropriate human subjects’ protocols were followed and institutional review board approvals obtained (UTK-IRB-20-05882-XM).

2.2. Modeling of Grocery Purchases Online During the Pandemic and Post-Pandemic Plans

Two consumer decisions regarding the use of online shopping were examined in this study. The first is whether the consumer used online grocery shop during the month of June 2020 and if so, how frequently. The online grocery shopping question respondents asked how many times in June 2020 they purchased groceries online including curbside pickup, and any delivery service (e.g. supermarket delivery, Amazon, and Instacart). The second decision among these online grocery shoppers is whether they planned to continue purchasing groceries online in the future regardless of the pandemic, only under pandemic conditions, or not at all.

Based on the prior studies, we hypothesized that households that are younger, higher income, have children, and more employed individuals in the household will be more likely to utilize online grocery shopping and plan to utilize it in the future regardless of continuation of the pandemic (Hansen, Reference Hansen 2005 ; Etumnu et al., Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Farag et al., Reference Farag, Schwanen, Dijst and Faber 2007 b; Hiser, Nayga, and Capps, Reference Hiser, Nayga and Capps 1999 ; Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ). Due to mixed findings regarding female gender, the direction of influence of female gender was not hypothesized a priori (Etumnu et al., Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Farag et al., Reference Farag, Schwanen, Dijst and Faber 2007 b; Jaller and Pawha, Reference Jaller and Pahwa 2020 ). While several studies have found complementarity between traditional in-store and online grocery shopping, given that the time frame studied here is the span of a month, the influence of greater number of in-store trips is difficult to hypothesize a priori (Farag, Krizek, and Dijst, Reference Farag, Krizek and Dijst 2007 a; Pozzi, Reference Pozzi 2013 ). However, it is more likely that a greater number of in-store trips is more likely to influence the frequency of online shopping, rather than the choice the shop online at all. In addition, it is likely that prior online shopping will strongly influence both online grocery shopping behaviors in June 2020 and plans for online grocery shopping in the future.

Two concerns precipitated by the pandemic that may influence shopping behavior are concern with contracting COVID-19 and concern with food shortages at retailers due to food supply chain disruptions (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson 2020 ). Either has the potential to increase the use of online shopping as consumers seek to avoid stores or plan food expenditures to avoid shortages or stockpile items of which they may experience a shortage at retailers or grocers. To assess consumers’ perceptions of these two pandemic-related risks, we asked respondents to rank their concern with either becoming ill with COVID-19 or that COVID-19 will cause food shortages, both on a scale from 1 to 9, where 1 indicated no concern and 9 indicated extremely concerned. Footnote 1 If the respondent was moderately concerned or greater, the variable was assigned a value of “1” and “0” otherwise.

2.2.1. Cragg Model of Number of Times Purchased Groceries Online

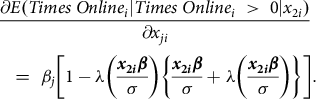

The expected value of the number of times shopper i purchases online groceries conditional on at least one purchase is:

The marginal effect of the jth explanatory variable on the probability of the ith shopper choosing online groceries at least once is

The marginal effect of the jth explanatory variable for the ith individual on the conditional level of Times Online is

The average marginal effects, which are the average of the individual level effects, are estimated using the Delta method (Greene, Reference Greene 2018 ). The craggit module in STATA 16.0 was used to estimate the Cragg model and the marginal effects of evaluated determinants (Burke, Reference Burke 2009 ).

2.2.2. Multinomial Probit Model of Future Online Grocery Shopping Decisions

The survey question regarding plans for future online shopping for groceries includes three possible outcomes ( M = 3), these are a) 3 = Yes, b) 2 = Yes, but only if COVID-19 is a concern, and c) 1 = No. With three outcomes, a multinomial probit model is used to estimate the probability of each future planned online grocery shopping outcome. The probability that the lth option is chosen among M alternatives by the ith consumer is then (Cameron and Trivedi, Reference Cameron and Trivedi 2005 ):

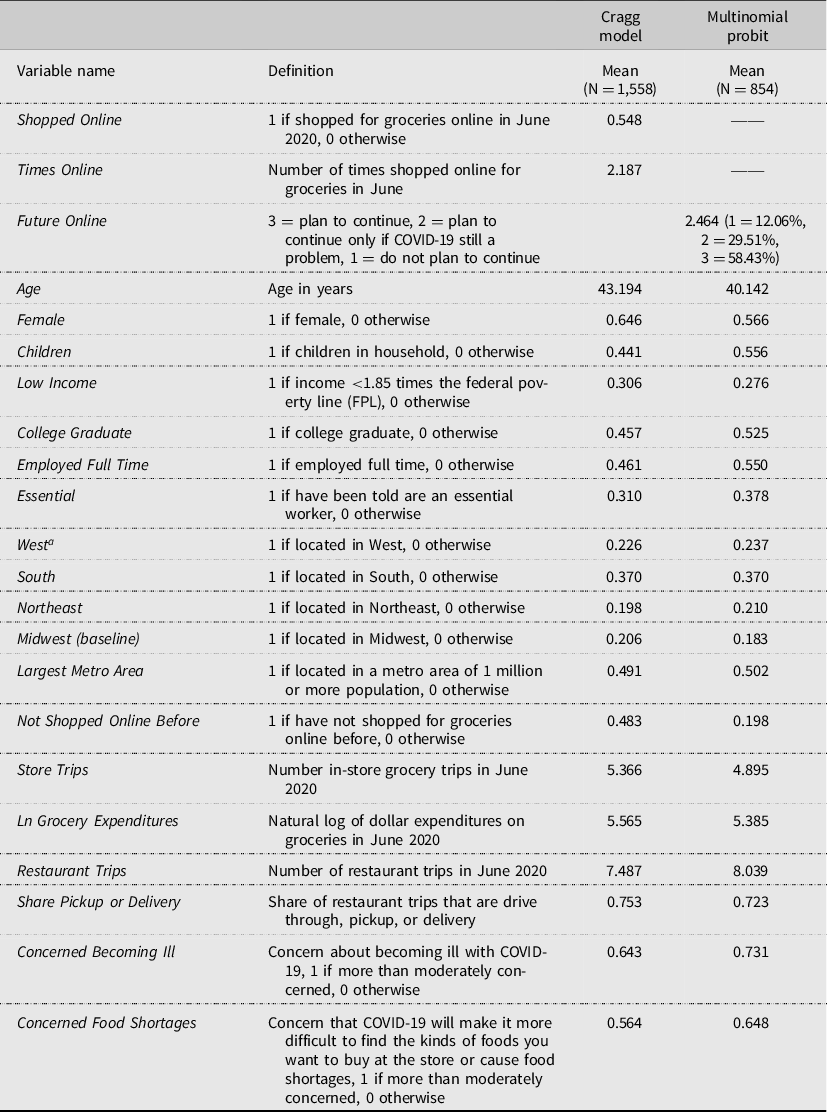

3.1 Summary Demographics of Respondents Used in the Models

Table 2 contains statistics summary for the variables used in the Cragg and multinomial models. These summary measures are for the 1,558 respondents out of the 2,000 who answered all questions needed for the analysis. Notably, about 54.8 percent of the 1,558 respondents shopped for groceries online in June 2020 and overall 48.3 percent indicated they had not shopped for groceries online before the pandemic. Also, among the June 2020 online grocery shoppers surveyed in this study, about 58.4 percent indicated they planned to continue to shop for groceries online regardless of the pandemic ( Future Online = 3). About 29.5 percent said they would continue to shop online for groceries, but only if COVID-19 remained as a problem ( Future Online = 2). Only 12.1 percent indicated they would not shop online for groceries in the future ( Future Online = 1).

Table 2. Names, definitions, and means for variables used in the Cragg model for online grocery shopping and multinomial model of future online grocery shopping plans

a The baseline region is Midwest. States in the West include AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NM, NV, OR, UT, WA, and WY, in the South include AL, AR, DC, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA, and WV, in the Northeast include CT, DE, MA, MD, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, and VT, and in the Midwest include IL, IN, IA, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, and WI.

As shown in Table 2 , similar to the full sample, the responses used in estimating the models were more likely to be female, have children in the household, and be college graduates as compared to the ACS estimates shown in Table 1 . The percentage of respondents residing in each region from Table 2 were similar to ACS regional percentages shown in Table 1 .

3.2. Cragg Model of Number of Times Shopped Online for Groceries in June 2020

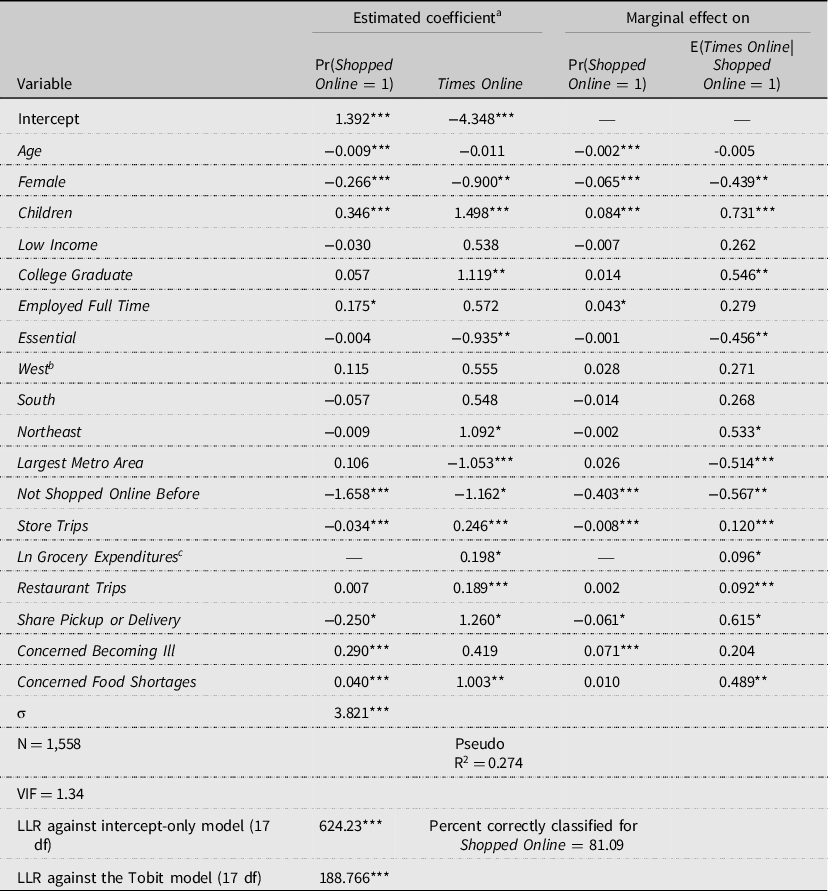

Table 3 contains the results from the Cragg model for online grocery shopping in June 2020. The log-likelihood ratio (LLR) test against an intercept-only model (-2*(LL Intercept Only-LL Model)) indicates that the model with the covariates is significant overall. Additionally, the LLR test comparing the Cragg model to the Tobit model, with a test statistic of 188.766 with 17 degrees of freedom from a chi-square distributed LLR test (-2*(LL Tobit-LL Cragg)), indicates that the model fit is improved by using the Cragg specification. The pseudo R 2 for the model is 0.274, while the percent correctly classified for Shopped Online is over 81 percent. The mean variance inflation factor of 1.34 suggests no statistically problematic multicollinearity found within the covariates.

Table 3. Estimated Cragg model of number of times shopped for groceries online and associated marginal effects (ME)

a ***Significance at α = 0.01, **significance at α = 0.05, and *significance at α = 0.1

b The baseline region is Midwest.

c The marginal effect of Grocery Expenditures is calculated as the ME Ln Groc. Expend./Grocery Expenditures.

The second column of Table 3 includes the estimated coefficients for the choice to use online grocery shopping in June 2020 (the probit portion of the Cragg model for Shopped Online = 1) and the third column contains the coefficients for the frequency of online shopping (the truncated portion of the Cragg model for Times Online ). The associated average marginal effects for the explanatory variables on probability of shopping online and the number of times shopped online for groceries were calculated using the estimated coefficients and equations ( 4 ) and ( 5 ), and shown in the third and fourth columns of Table 3 .

As seen in Table 3 , age ( Age ) negatively influences the likelihood of shopping online for groceries by 0.2 percent for each year, which is consistent with prior research findings (Etumnu et al. Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Farag et al., Reference Farag, Schwanen, Dijst and Faber 2007 b; Hiser, Nayga, and Capps, Reference Hiser, Nayga and Capps 1999 ; Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ). However, age does not significantly influence the number of times shopped online. Consistent with Etumnu et al. ( Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ) and (Farag et al., Reference Farag, Schwanen, Dijst and Faber 2007 b), identifying as female ( Female ) negatively influences the probability of shopping for groceries online by 6.5 percent ( Shopped Online ) and the number of times ( Times Online ) the respondent grocery shopped online by 0.439 times.

Respondents with children in the household ( Children ) are 8.4 percent more likely to have shopped for groceries online in June 2020 and made about 0.731 more trips than households without children. These findings are similar to some previous studies (e.g. Etumnu et al. Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 , Hansen, Reference Hansen 2005 ; Jaller and Pawha, Reference Jaller and Pahwa 2020 , Melis et al., Reference Melis, Campo, Lamey and Breugelmans 2016 ) that suggested that household food shoppers may find it more challenging to shop in-store with accompanying children.

In line with other studies (Etumnu et al., Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Hiser, Nayga, and Capps, Reference Hiser, Nayga and Capps 1999 ; Jaller and Pawha, Reference Jaller and Pahwa 2020 ; Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ), this study found that having a college degree ( College Graduate ) increases the frequency of online grocery shopping 0.546 times among those who used online shopping at least once. However, being a college graduate does not significantly influence the initial decision to shop online.

While full-time employment status ( Employed Full Time ) does not influence the number of times the respondent online grocery shopped, it positively influences the probability that the respondent shopped for groceries online by about 4.4 percent. This finding is consistent with those of Van Droogenbroeck and Hove ( Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ). Identifying as an essential worker ( Essential ) does not significantly influence the probability of online grocery shopping but does decrease the frequency of online shopping by 0.456 trips among those who chose to shop online. For essential workers, the potential convenience of online shopping may not have been outweighed by the convenience and ability to visit their regular store during their commute to or from work. This finding may have implications for retailers as more households return to working in-person in the future and have to re-evaluate the trade-offs of ordering online with the ability to shop at stores along commuting routes.

Poverty status ( Low Income ) does not have the anticipated positive influence on online shopping as suggested by pre-pandemic research (Hansen, Reference Hansen 2005 ). Rather, our study found that Low Income has no significant influence on the choice to shop online, or the frequency of online shopping. Two theories could explain this finding. First, in this study’s definition, both grocery purchases that were delivered or curbside pickup are included. If previous studies did not include curbside pickup, and if lower-income families are more likely to use curbside pickup because it does not incur a delivery fee, then previous studies may have been less likely to detect lower-income households’ use of online grocery shopping. Second, prior to the pandemic lower-income households that participated in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) could not use their benefits to purchase groceries online. The USDA Food and Nutrition Services (USDA-FNS), which manages the SNAP program, began a limited pilot program pre-pandemic to allow SNAP participants to use their benefits to purchase groceries online, and in March 2020 they began expanding the program into additional states (USDA/FNS, 2020 ). While SNAP benefits could be used for online groceries, they should not be used to pay for delivery fees and could be redeemed at a very limited number of retailers. However, Walmart and Amazon were an option in most states. Reports suggest this policy change may have dramatically increased online purchases by SNAP households since the beginning of the pandemic (Day, Reference Day 2020 ). Additionally, several supermarket chains and Walmart began accepting SNAP as a form of payment for curbside pickup during the pandemic and independent of the FNS pilot program (Berthiaume, Reference Berthiaume 2020 ; Redman, Reference Redman 2020 a; WalMart, 2020 ). Jointly, these may have increased the utilization of online grocery shopping among lower-income households.

Lack of experience with online grocery shopping ( Not Shopped Online Before ) has a large effect both on the use and frequency of online grocery shopping in June 2020. Those who had not shopped online for groceries before are about 40 percent less likely to have shopped online for them in June 2020 and among those who did, they used online shopping 0.567 fewer times than those with previous online shopping experience.

In-store shopping trips ( Store Trips ) have mixed effects on online grocery shopping. Each additional grocery trip decreases the probability of shopping online by 0.8 percent but increases the frequency of online grocery shopping by 0.120 times. This latter finding suggests a complementary, rather than substitution, relationship between online and brick-and-mortar shopping trips which is similar to findings by Farag et al. ( Reference Farag, Krizek and Dijst 2007 a) and Pozzi ( Reference Pozzi 2013 ). However, additional research would be needed to substantiate this hypothesis.

Restaurant trips do not influence probability of shopping online; however, among those who shopped online, each additional restaurant trip increases the frequency they shopped online by 0.092 trips. As the share of restaurant trips for pickup or delivery increases, the probability of shopping online decreases by 6.1 percent hinting at possible substitutability between pickup/delivery restaurant trips and online grocery shopping. Yet, among those who shopped online, increasing the share of restaurant trips that were pickup or delivery by a point increases the number of times the respondent shopped online by 0.615. Since increasing the share of restaurant trips that are pickup/delivery increases the frequency of online grocery shopping, after controlling for the influence of total restaurant trips, this result could reflect averting behaviors during the pandemic among online grocery shoppers. Findings regarding the effects of pandemic risk variables discussed below further support this hypothesis.

As might be expected, overall grocery expenditures, as measured by the natural log of June 2020 grocery expenditures ( Ln Grocery Expenditures ) increases the number of times shopped online ( Times Online ). Footnote 3 Using the untransformed values, for each 100 dollars of grocery expenditures in June 2020, the number of times shopped online increases by 0.160.

Compared with respondents from the Midwest , Northeast respondents who shopped for groceries online did so 0.533 times more often. While large metro area was expected to have a positive influence on online shopping, it does not significantly affect probability of buying groceries online and it negatively affects the frequency for those who used online shopping by 0.533 trips. One possible explanation for the negative effect is that perhaps metro shoppers were less likely to say they were spending more on groceries than normal than the suburban or more rural counterparts. As part of debriefing questions, it was asked whether the respondent thought they spent more or less on groceries than usual in June 2020. However, while 40.42 percent of the metro respondents said they spent more on groceries in June 2020 than normal, only 32.40 percent of the non-metro respondents spent more than usual. Another potential explanation is that metro shoppers may be more experienced with and trusting of online grocery services and hence be willing to purchase more per online shopping trip. Given that they were spending more than usual on groceries in June 2020 than their non-metro counterparts, this seems more plausible. However, additional research would be needed to evaluate metro versus non-metro shopper knowledgeability and trust in online shopping for groceries.

Concerns about becoming ill with COVID-19 or possible pandemic-associated food shortages influenced online grocery shopping but in different ways. Being at least moderately concerned about becoming ill with COVID-19 ( Concern Becoming Ill ) increases the probability of online grocery shopping by 7.1 percent but does not significantly influence the number of times shopped online. However, being at least moderately concerned about food shortages ( Concerned Food Shortages ) positively influence frequency of online grocery shopping by 0.489 times. While the exact reasons for this relationship require further study, they do suggest that COVID-19 concerns related to the food system continued to influence consumer behavior even into the summer of 2020. Some possible explanations may include the increased utilization of online grocery shopping to maintain a continuous supply of items that were previously in short supply, or stockpiling goods. However, these are hypotheses that would require future study.

3.3. Reasons for Not Shopping Online for Groceries in June 2020

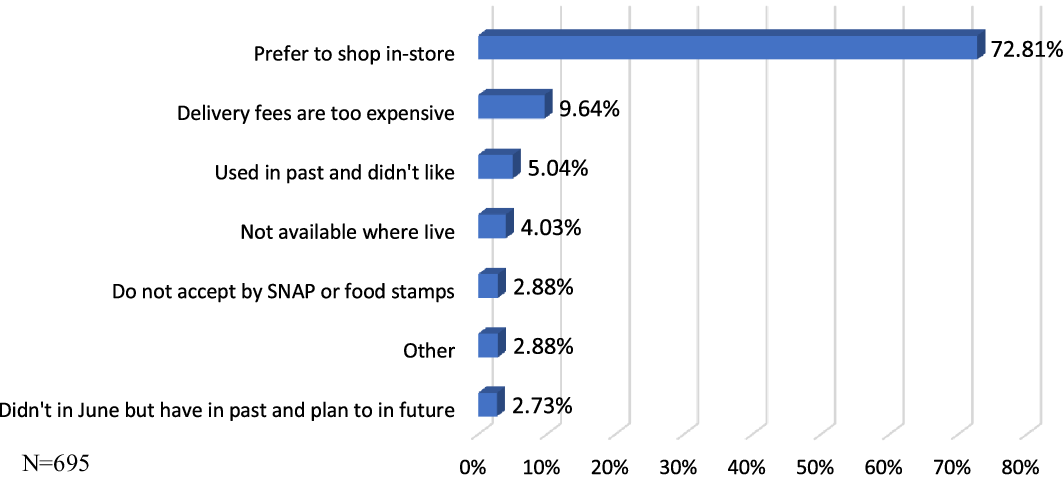

The survey also asked respondents the reasons for not online grocery shopping in June 2020 and the results are reported in Figure 1 . Personal preference for shopping in-store is the dominant reason (˜73%), distantly followed by delivery fees being too expensive at 9.64 percent. Only 5 percent indicated that they did not like the previous experiences in online grocery shopping, while less than 5 percent indicated they did not have the services available where they live, that their SNAP benefits were not accepted, or that they had purchased online before, but just did not do so in June 2020.

Figure 1. Reasons for not shopping for groceries online in June 2020.

3.4. Multinomial Probit Model of Plans for Future Online Grocery Shopping

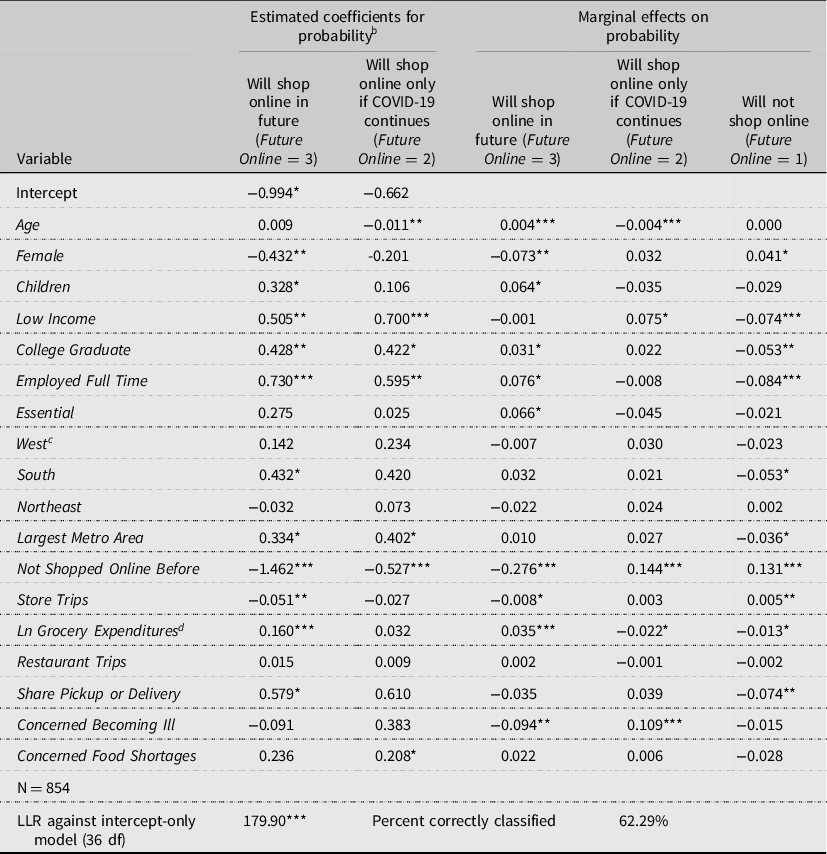

The estimated multinomial probit model of future plans for online grocery shopping ( Future Online ) among households that currently use online grocery is reported in Table 4 . The reference category is Future Online = 1, or no plans to grocery shop online in the future. The associated average marginal effects for the explanatory variables on probability of shopping online and the number of times shopped online for groceries are calculated using the estimated coefficients and equation (7) and are shown in the third to fifth columns of Table 4 . The standard errors associated with the marginal effects were calculated using the Delta method. The model was significant overall as indicated by the LLR test against an intercept-only model. The model correctly classified just under 62.3 percent of the observations regarding future online shopping plans.

Table 4. Estimated multinomial probit model of future online grocery shopping plans ( Future Online ) and associated marginal effects (ME) a

a The baseline category is Future Online = 1 or will not shop online.

b ***Significance at α = 0.01, **significance at α = 0.05, and *significance at α = 0.10.

c The baseline region is Midwest.

d The marginal effect of Grocery Expenditures is calculated as the ME Ln Groc. Expend./Grocery Expenditures .

Several consumer characteristics influenced plans to use online grocery shopping in the futur e, regardless of the pandemic, as indicated by their relationship with the Future Online = 3 outcome in column 3 of Table 4 . The presence of a child ( Children ) increased the probability of respondents stating they would shop online in the future by 6.4 percent, which suggests that respondents with children value the convenience afforded by shopping online that may reduce the number of brick-and-mortar store trips with children even after the pandemic ends (Etumnu et al. Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Hansen, Reference Hansen 2005 ; Jaller and Pawha, Reference Jaller and Pahwa 2020 ; Melis et al., Reference Melis, Campo, Lamey and Breugelmans 2016 ).

College Graduate increased the probability of planning to shop online in the future by 3.1 percent and decreased the probability of not planning to do so by 5.3 percent. This result is similar to findings from prior research about the effects of education on online grocery shopping (Etumnu et al., Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Hiser, Nayga, and Capps, Reference Hiser, Nayga and Capps 1999 ; Jaller and Pawha, Reference Jaller and Pahwa 2020 ; Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ) and suggests that higher educated online grocery shoppers in June 2020 plan to continue to so into the future. In addition, full-time employment increased the probability of planning to use online grocery shopping in the future by 7.6 percent and decreased the probability of saying they would not by 8.4 percent. Full-time workers likely value the convenience afforded by online grocery shopping and plan to continue it into the future which is consistent with prior research findings (Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ).

With each additional year of age ( Age ), the probability of planning to shop online in the future regardless of the pandemic increased by 0.4 percent, while the probability of planning to online shop only if the pandemic persists decreased by 0.4 percent. This finding about the effects of age on future plans is unlike findings from prior research of negative effects of age on online grocery shopping (Etumnu et al. Reference Etumnu, Widmar, Foster and Ortega 2019 ; Farag et al., Reference Farag, Schwanen, Dijst and Faber 2007 b; Hiser, Nayga, and Capps, Reference Hiser, Nayga and Capps 1999 ; Van Droogenbroeck and Hove, Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 2017 ). This finding could reflect that older shoppers who have experienced online grocery shopping may now value the convenience it affords so as to plan to continue it into the future.

Compared with higher-income households, lower-income households ( Low Income ) that shopped online in June 2020 are 7.4 percent less likely to continue shopping online in the future and 7.5 percent more likely to choose to shop online only under pandemic conditions. This finding suggests that compared with higher-income households, lower-income households will be more likely to continue online shopping if pandemic conditions persist. This finding could reflect a perceived trade-off in the minds of lower-income online grocery shoppers during the pandemic, weighing any additional grocery costs incurred by online shopping against concerns about becoming ill shopping in-store if the pandemic persists.

Full-time employment status ( Employed Full Time ) positively influences probability of shopping online for groceries in the future (7.6 percent) and negatively influenced probability of not shopping online in the future (−8.4 percent). Furthermore, essential workers ( Essential ) are 6.6 percent more likely to say they would shop online for groceries in the future regardless of the pandemic. These results echo prior research suggesting a link between busy schedules and the convenience of online shopping (Verhoef and Langerak, Reference Verhoef and Langerak 2001 ).

Results also show that regional location and urbanization of residence influence plans for future online grocery shopping. Compared with those in the Midwest , those in the South are 5.3 percent less likely to say they do not plan to shop online for groceries in the future. Also, compared with those outside metro areas, those in the largest metro areas are 3.6 percent less likely to say they do not plan to shop online for groceries in the future.

Lack of previous online grocery purchasing experience ( Not Shopped Online Before ) decreases the probability of plans to shop in the future by 27.6 percent and increases the likelihood of not shopping online in the future by 13.1 percent. However, lack of experience also positively influences shopping online only if the pandemic continues to be a problem (14.4 percent). As this variable gauges experience with shopping online prior to June 2020, it may suggest that households that adopt online shopping during the later period of the pandemic are primarily concerned with minimizing their exposure to COVID-19 and will be unlikely to continue online grocery shopping behaviors after the pandemic ends. This would concur with the finding by Hand et al. ( Reference Hand, Dall’Olmo Riley, Rettie, Harris and Singh 2009 ) that once situational factors that precipitate use of online shopping are removed, shoppers tend to return back to brick-and-mortar shopping.

More frequent in-store grocery store trips positively influence probability of the respondent indicating they do not plan to shop online for groceries in the future (0.5 percent) and negatively influence probability that they plan to shop online for groceries in the future (−0.8 percent). Restaurant trips do not significantly influence future online shopping plans, but as the share of restaurant trips that were pickup or delivery increases, the probability of not shopping online for groceries in the future decreases by 7.4 percent. These findings could reflect planned averting behaviors, with those currently shopping in-store less and using drive through or pickup dining more, being less likely to say they would not shop online in the future.

The natural log of overall grocery expenditures for June 2020 ( Ln Grocery Expenditures ) positively influences respondents’ intentions for future online grocery shopping. For every $100 spent on groceries, the effect on probability of shopping online in the future is 11.0 percent, shopping online only if the pandemic continues is −4.1 percent, and not planning to shop online in the future is −6.9 percent.

The pandemic concern variables primarily influence planned future online shopping behavior related to the pandemic. Moderate concern with becoming ill with COVID-19 ( Concerned Becoming Ill ) decreases the probability of planning to shop online in the future regardless of pandemic conditions (−9.4 percent) but increases the probability of continuing to shop online only while the pandemic continues (10.9 percent). This result suggests that greater concerns about becoming ill will likely only drive online shopping while the pandemic persists. Although concerns about food shortages ( Concerned Food Shortages ) influenced the frequency of online grocery shopping in June 2020, it has no effect on future plans for online grocery shopping. This suggests that grocery shoppers were responding to supply chain disruptions early in the pandemic but do not see this as likely problematic in the future and plan to adjust their shopping plans accordingly. It is possible that those who are most concerned about food shortages may not see online shopping as a preferred means to stockpile as compared to brick-and-mortar shopping. However, additional research would be needed to investigate this possibility further.

4. Implications and Conclusions

While online grocery shopping had been increasing in popularity prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, the onset of the pandemic accelerated its adoption. With this rapid increase in use of online grocery shopping, developing a better understanding of drivers of its use is of interest not only to the grocery retailing industry but also to policymakers. This study investigated the influence of pandemic-specific drivers, such as concerns about becoming ill and potential food shortages, as well shopper demographics, food shopping behaviors, and grocery expenditure patterns. Furthermore, to understand the potential staying power of online grocery shopping, this study also examined factors influencing online grocery shoppers’ intentions to continue online shopping in the future, under pandemic and non-pandemic conditions.

Many of the household determinants found in pre-pandemic research to increase online grocery shopping were also found in this research to increase online grocery shopping during the pandemic (younger age, full-time employment, college education, and the presence of children). Unexpectedly, low income had no influence on either the use or frequency of using online grocery shopping, whereas in past research it was generally associated with lower utilization of online grocery shopping. While this finding needs to be investigated further in future research, it may suggest that the pandemic has been particularly influential on the choice to grocery shop online among low-income households, who were previously less likely to utilize online grocery shopping. This may be related to the expansion of curbside pickup and the expansion of USDA pilot program allowing SNAP participants to use their benefits to make online grocery purchases (USDA/FNS, 2020 ; Hansen, Reference Hansen 2005 ).

While low income did not influence probability or frequency of online shopping in June 2020, low-income shoppers are more likely to say they would shop online if the pandemic continues, suggesting that lower-income shoppers do not believe the benefits of online shopping will persist beyond the pandemic. These households may be most sensitive to the additional delivery fees or cost associated with online grocery shopping that cannot be paid for with their SNAP benefits (USDA/FNS, 2020 ). This finding is in contrast to the influence of full-time employment and essential worker status which both increase the likelihood of future online shopping regardless of the pandemic. Full-time and essential workers may have less time to shop in-person and value the convenience of online grocery shopping beyond the duration of the pandemic. Given the potential of online grocery shopping to improve access to supermarkets for low-income households, future research should focus on the barriers and benefits of online grocery shopping among lower-income households.

Older populations are another vulnerable population of concern during the pandemic, because they may be more susceptible to serious illness if they contract COVID-19, and thus could benefit from policies and programs to reduce their exposure, such as those encouraging online grocery shopping. However, our results showed that age negatively influenced the probability of shopping for groceries online, perhaps reflecting that older populations are less comfortable with the concept of and technology needed to shop for groceries online. As evidenced by reasons for not shopping online, that majority of those who did not shop online preferred to shop in-store, despite the pandemic. Interestingly, among those who did shop online for groceries, older age had the opposite effects on plans for future grocery shopping. Older age increases the likelihood of continuing to shop online in the future, regardless of the pandemic. These findings suggest that once older shoppers try online shopping, compared with younger shoppers, they are more likely plan to continue it, perhaps due to the convenience, and in some cases, to avoid the physical demands associated with grocery shopping. Thus, developing policies to address barriers to use and increase online grocery shopping among older populations may not only benefit them during the pandemic, but also beyond. For example, some programs might focus on how to access and use online grocery shopping for the more nascent online shopper, while other programs might focus on how to use meal planning with online shopping and online list-making to more efficiently use food budgets and potentially reduce food waste.

Concerns with becoming ill with COVID-19 increased the likelihood of utilizing online grocery shopping in June 2020, while the frequency of online grocery shopping, among those who use online grocery shopping, was driven in part by fears of food shortages. Combined with the finding that increasing total grocery expenditures and in-store trips also increased the frequency of online grocery store shopping, this may suggest stockpiling behaviors among grocery shoppers. However, this behavior was not directly addressed in this study and requires future study for more definitive conclusions. Additional research should likely examine how consumers may be shopping in-store and supplementing with items they cannot find in-store with online purchases and vice versa.

The long-term effects of the pandemic on online grocery shopping will require further analysis, but our research does provide several preliminary insights. Those who had not previously purchased groceries online were 40.3 percent less likely to shop online for groceries in June 2020; however, among online grocery shoppers, new online shoppers were only 27.6 percent less likely to say they would shop online in the future regardless of the pandemic. This latter result suggests that some first-timers will be likely to stay with online shopping regardless of the pandemic. However, among respondents who utilized online grocery shopping in June 2020, about 12 percent indicated they do not plan to continue and 29.5 percent indicated they will continue to shop online only if COVID-19 continues. This foretells that at least some of the increased utilization of online grocery shopping will not persist beyond the pandemic.

Only concerns about becoming ill influence future online shopping intentions, while concerns about food shortages do not. While shoppers may have seen food supply chain disruptions that occurred in the first few months of the pandemic, they may have confidence in the supply chain to resolve disruptions and shortages in the longer term. However, being moderately concerned about becoming ill increased the probability that a respondent would shop online in the future but only if the pandemic persists. This latter finding could suggest that online shoppers who are driven by concerns about becoming ill from COVID-19 may revert to their usual in-store shopping behaviors when the pandemic subsides. Taken together with the finding that those who had not shopped online before were less likely to plan to do so in the future, inexperienced online shoppers who were more driven by pandemic concerns may be less likely to sustain online grocery shopping in the future beyond the pandemic.

This study has several limitations. First, it represents a snapshot of time in June 2020. Hence, some of the variables included in the model of June 2020 online grocery shopping, such as June grocery expenditures, restaurant trips, in-store grocery trips, and share of restaurant trips that were pickup, could represent endogenous decision-making during that month. Additional research including consumer behaviors from multiple time frames could help alleviate this issue. Furthermore, future research should focus on the long-term impacts of the increased utilization of online grocery that began during the pandemic, including how retailers are adapting their online shopping services to meet changing shopper preferences and perhaps improving their services during the pandemic. While out of the scope of this article, future research should examine the availability of online grocery by retailer type to determine if current trends will disproportionately benefit large, chain grocers who may be better able to support online services, while harming smaller, independent grocers. This could have implications for communities that rely on smaller grocers, or for individuals who cannot easily access online services.

Second, we did not ask detailed food shopping questions to investigate how the types of food items purchased may have changed as a result of the pandemic. This could potentially be of importance as some items may be more readily deliverable through online shopping than others. Etumnu and Widmar ( Reference Etumnu and Widmar 2020 ) found certain types of foods were more likely to be ordered online than others among US food shoppers. Additional research should likely examine whether more perishable items, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, are purchased in a brick-and-mortar setting rather than online, particularly in rural areas where delivery services for these types of items may be lacking.

Third, our survey was an online survey, and not an in-person or intercept survey. This could potentially create some sample bias toward those who are more familiar with the internet, and possibly, online shopping. Additional research findings from an in-person or intercept survey in-store could complement the findings from this research.

Conceptualization: K.L.J., J.Y., X.C., and T.Y.; Methodology: K.L.J., J.Y., X.C., and T.Y.; Formal Analysis: K.L.J. and J.Y.; Data Curation: K.L.J. and J.Y.; Writing—Original Draft: K.L.J., J.Y., X.C., and T.Y.; Writing—Review and Editing: K.L.J., J.Y., X.C., and T.Y.

Funding for this study was provided by in part by Ag Research at The University of Tennessee Institute for Agriculture. The findings and views represented in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessary represent those of the institution.

Drs. Jensen, Yenerall, Chen, and Yu declare no competing interests.

Data for this study were collected under UTK IRB Approval UTK IRB-20-05882-XM and were done so with respondents being assured of confidentially. Therefore, individual data may not be released.

1 Taherdoost ( Reference Taherdoost 2019 ) provided an overview of use of differing Likert scales, proposing use of a 7-point Likert scale. However, as noted in Taherdoost’s paper, Preston and Colman ( Reference Preston and Colman 2000 ) and Bendig ( Reference Bendig 1954 ) suggested longer scales (7 point to 9 point) are preferable for capturing respondents’ sentiments, with this benefit appearing to decrease with longer scales, such as 12-point scale (McRae, Reference McRae 1970 ).

3 Ln Grocery Expenditures, Store Trips, Restaurant Trips , and ShrPickup are potentially endogenous decisions to probability of choosing to shop online in June and the number of times shopped online in June 2020. Results were validated by estimating the models without these variables and the estimates appeared to be robust. These models are not presented in the interest of parsimony; however, they are available from the authors upon request.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 53, Issue 3

- Kimberly L. Jensen (a1) , Jackie Yenerall (a1) , Xuqi Chen (a1) and T. Edward Yu (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/aae.2021.15

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

A theoretical model of factors influencing online consumer purchasing behavior through electronic word of mouth data mining and analysis

Roles Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Economics and Management, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, High-tech District, Zhengzhou City, Henan Province, China

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Politics and Public Administration, Soochow University, Gusu District, Suzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China

Roles Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration

Roles Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration

- Qiwei Wang,

- Xiaoya Zhu,

- Manman Wang,

- Fuli Zhou,

- Shuang Cheng

- Published: May 18, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286034

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has impacted and changed consumer behavior because of a prolonged quarantine and lockdown. This study proposed a theoretical framework to explore and define the influencing factors of online consumer purchasing behavior (OCPB) based on electronic word-of-mouth (e-WOM) data mining and analysis. Data pertaining to e-WOM were crawled from smartphone product reviews from the two most popular online shopping platforms in China, Jingdong.com and Taobao.com . Data processing aimed to filter noise and translate unstructured data from complex text reviews into structured data. The machine learning based K-means clustering method was utilized to cluster the influencing factors of OCPB. Comparing the clustering results and Kotler’s five products level, the influencing factors of OCPB were clustered around four categories: perceived emergency context, product, innovation, and function attributes. This study contributes to OCPB research by data mining and analysis that can adequately identify the influencing factors based on e-WOM. The definition and explanation of these categories may have important implications for both OCPB and e-commerce.

Citation: Wang Q, Zhu X, Wang M, Zhou F, Cheng S (2023) A theoretical model of factors influencing online consumer purchasing behavior through electronic word of mouth data mining and analysis. PLoS ONE 18(5): e0286034. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286034

Editor: Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan, Al-Ahliyya Amman University, JORDAN

Received: April 19, 2023; Accepted: May 5, 2023; Published: May 18, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Wang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Henan Province Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (grant number. 2020CZH012), the Henan Key Research and Development and Promotion Special (Soft Science Research) (grant number. 222400410126), the Jiangsu Province Social Science Foundation Youth Project (grant number. 21GLC012) and the Doctor Fund of Zhengzhou University of Light Industry (grant number. 2020BSJJ022, 2019BSJJ017). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

A prolonged quarantine and lockdown imposed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has changed the human lifestyle worldwide. The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted various sectors such as manufacturing, import and export trade, tourism, catering, transportation, entertainment, especially retail and hence the global economy. Consumer behavior has gradually shifted toward contactless services and e-commerce activities owing to the COVID-19 [ 1 ].

Consumers are relying on e-commerce more than ever to protect their health. Recent advances in information technology, digital transformation, and the Internet helped consumers to encounter the COVID-19 to meet the needs of the daily lives, which led to an increase in the importance of e-commerce and changes in consumers’ online purchasing patterns [ 2 ]. When consumers shop online, their behavior is considered non-traditional, and is illustrated by a new trend and current environment. To analyze the influencing factors of online consumer purchasing behavior (OCPB), it is necessary to consider several factors, such as the price and quality of a product, consumers’ preferences, website design, function, security, search, and electronic word-of-mouth (e-WOM) [ 3 ]. As the current website design and payment security have become a user-friendly and guaranteed system compared with a decade ago, some factors are no longer considered as essential. By contrast, greater diversity and complexity have become the main characteristics of the influencing factors. Furthermore, under the traditional sales model, consumers’ purchase decisions were simple, while online consumers have more options in terms of shopping channels and decision choices. Meanwhile, in recent years, consumers’ preferences have gradually shifted from standardized products to customized and personalized. In line with these changes, information technology and data science, such as big data analytics, data mining from e-WOM, and machine learning (ML), adaptively analyze data regarding online consumers’ needs to obtain more accurate data.

Since the concept of big data was proposed in 2008, it has been applied and developed lasting 14 years, emerging as a valuable tool for global e-commerce recently. However, most enterprises have failed to seize the benefits generated from big data. In the context of big data, a huge number of comments were posted regarding e-malls (Amazon, Taobao, etc.) and online social media (blogs, Bulletin Board System, etc.). For instance, Amazon was the first e-commerce company to establish an e-WOM system in 1995, which provided the company with valuable suggestions from online consumers. E-WOM has greater credibility and persuasiveness, compared with traditional word of mouth (WOM), which is limited by various subjective factors. Moreover, e-WOM has the advantage of containing not only structured data (e.g., ratings) but also unstructured data (e.g., the specific content of consumer reviews). However, e-WOM provides product-related information that cannot be directly transformed to a research objective. Thus, an innovative method of big data analytics needs to be utilized to explore the influencing factors of OCPB, which shows the advantage of interdisciplinary applications.

The research problems are to explore the factors influencing OCPB through e-WOM data mining and analysis and explain the most important influencing factors for online consumers that are likely to exist in the future within the context of the COVID-19. The study fulfills the literature gaps on exploring influencing factors of OCPB from the perspective of e-WOM. The study makes a significant contribution to the consumer study because its findings can adequately identify the influencing factors of OCPB. It also provides the theoretical and managerial implications of its findings including how e-commerce platforms can use such data to adapt their platforms and marketing strategies to diverse situations.

The remainder of this is organized as follows. Section 1 presents the introduction. Section 2 discusses the literature review and hypotheses. Section 3 provides the methodology, including data mining and analysis. Section 4 describes the results, including K-means results, performance metrics, hypotheses results, and a theoretical model. Sections 5 and 6 provide discussion and conclusion, respectively.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

2.1 influencing factors of ocpb.

Online shopping has an increasing sales volume each year, which has become huge challenges for offline retailers. Venkatesh et al. [ 4 ] found that culture, demographics, economics, technology, and personal psychology were the main antecedents of online shopping, and the main drivers of online shopping were congruence, impulse buying behavior, value consciousness, risk, local shopping, shopping enjoyment, and browsing enjoyment by a comprehensive model of consumers online purchasing behavior. Within the context of COVID-19, OCPB is positively impacted by attitude toward online shopping [ 5 ]. Melović et al. [ 6 ] focused on millennials’ online shopping behavior and noted that the demographic characteristics, the affirmative characteristics, risks and barriers of online shopping were the key influencing factors. Based on the stimulus-organism-response (SOR) theory model, consumers’ actual impulsive shopping behavior is impacted by arousal and pleasure [ 7 ]. Furthermore, the influencing factors of consumers’ purchase behavior toward green brands are green perceived quality, green perceived value, green perceived risk, information costs saved, and purchase intentions by perceived risk theory [ 8 ]. The positive and negative effects of corporate social responsibility practices on consumers’ pro-social behavior are moderated by consumer-brand social distance, although it also impacts consumer behavior beyond the consumer-brand dyadic relationship [ 9 ]. Green perceived value, functional value, conditional value, social value, and emotional value may impact green energy consumers’ purchase behavior [ 10 ]. Recipients’ behavior and WOM predict distant consumers’ behavior [ 11 ]. Moreover, consumer behavior is significantly impacted by financial rewards, perceived intrusiveness, attitudes toward e-mail advertising, and intentions toward the senders [ 12 ]. Store brand consumer purchase behavior is positively impacted by store image perceptions, store brand price-image, value consciousness, and store brand attitude [ 13 ]. A meta-analysis summarizes the influencing factors of consumer behavior, household size, store brands, store loyalty, innovativeness, familiarity with store brands, brand loyalty to national brands, price consciousness, value consciousness, perceived quality of store brands, perceived value for money of store brands, and search versus experience positively impact consumer behavior, whereas price–quality consciousness, quality consciousness, price of store brands, and the consequences of making a mistake in a purchase negatively impact consumer behavior [ 14 ].

Based on protection motivation theory and theory of planned behavior (TPB), consumers are more likely to use online shopping channels than offline channels during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 15 ]. The TPB is also adapted to explain the influencing factors of consumers’ behavior in different areas. For instance, the attitude, perceived behavioral control, policy information campaigns, and past-purchase experiences significantly impact consumers’ purchase intention, whereas subjective and moral norms show no significant relationship based on the extended TPB [ 16 ]. Although green purchase behavior has different antecedents, only personal norms and value for money have fully significant relationships with green purchase behavior, environmental concern, materialism, creativity, and green practices. Functional value positively influences purchase satisfaction, physical unavailability, materialism, creativity, and green practices, and negatively influences the frequency of green product purchase by extending the TPB [ 17 ]. Meanwhile, Nimri et al. [ 18 ] utilized the TPB in green hotels and showed that knowledge and attitudes, as well as subjective injunctive norms, positively impacted consumers’ purchase intention. Yi [ 19 ] observed that attitude, social norm, and perceived behavioral control positively impacted consumers’ purchase intention based on the TPB. The factors of supportive behaviors for environmental organizations, subjective norms, consumer attitude toward sustainable purchasing, perceived marketplace influence, consumers’ knowledge regarding sustainability-related issues, and environmental concern are the influencing factors of consumers sustainable purchase behavior [ 20 ]. Consumers’ green purchase behavior is impacted by the intention through support of the TPB [ 21 ].

2.2 Influencing factors of emergency context attribute

Consumers exhibited panic purchase behavior during the COVID-19, which might have been caused by psychological factors such as uncertainty, perceptions of severity, perceptions of scarcity, and anxiety [ 22 ]. In the reacting phase, consumers responded to the perceived unexpected threat of the COVID-19 and intended to regain control of lost freedoms; in the coping phase, they addressed this issue by adopting new behaviors and exerting control in other areas, and in the adapting phase, they became less reactive and accommodated their consumption habits to the new normal [ 23 ]. The positive and negative e-WOMs may have significant influence on online consumers’ psychology. Specifically, e-WOM that conveys positive emotions (pride, surprise) tends to have a greater impact on male readers’ perception of the reviewer’s cognitive effort than female readers, whereas e-WOM that conveys negative emotions (anger, fear) has a greater impact on cognitive effort of female readers than male readers [ 24 ]. When online consumers believe their behavioral effect is feasible and positive, while their behavioral decision is related to the behavioral outcome [ 25 ]. Traditionally, there are five stages of consumer behavior that include demand identification, information search, evaluation of selection, purchase, and post-purchase evaluation. In addition, online purchase behavior involved in the various stages can be categorized into: attitude formation, intention, adoption, and continuation. Most of the important factors that influence online purchasing behavior are attitude, motivation, trust, risk, demographics, website, etc. “Internet Adoption” is widely used as a basic framework for studying “online buying adoption”. Psychological and economic structures associated with the IT adoption model can be used as the online consumer’s behavior models for innovative marketers. The adoption of online purchasing behavior is explained by different classic models of attitude behavior [ 26 ]. Consumer behaviors represented by customer trust and customer satisfaction, influence repurchase and positive WOM intentions [ 27 ]. Return policy leniency, cash on delivery, and social commerce constructs were significant facilitators of customer trust [ 28 ]. Meanwhile, seller uncertainty was negatively influenced by return policy leniency, information quality, number of positive comments, seller reputation, and seller popularity [ 29 ]. Social commerce components were a necessity in complementing the quality dimensions of e-service in the environment of e-commerce [ 30 ]. Perceived security, perceived privacy and perceived information quality were all significant facilitators of online customer trust and satisfaction [ 31 ].