Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

indigenous canada

8 templates

6 templates

113 templates

first day of school

68 templates

machine learning

5 templates

welcome back to school

124 templates

Introduction of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs)

It seems that you like this template, introduction of genetically modified organisms (gmos) presentation, free google slides theme, powerpoint template, and canva presentation template.

Revolutionary, valuable addition to our food or harmful health risk? Genetically modified organisms (or GMOs for short) are still an unknown quantity for many people. There’s little factual information and lots of conspiracy theories around modified crops and animals, making people cautious to say the least. This Google Slides and PowerPoint template is your chance to compile information, speak about the science, advantages and risks of genetic modification, and give your audience a foundation for building their own opinion. Download and edit this slide deck full of subject-related illustrations and clear visual representations of data!

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 35 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides, Canva, and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the resources used

How can I use the template?

Am I free to use the templates?

How to attribute?

Attribution required If you are a free user, you must attribute Slidesgo by keeping the slide where the credits appear. How to attribute?

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

Register for free and start editing online

Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- HIV and AIDS

- Hypertension

- Mental disorders

- Top 10 causes of death

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Triple Billion

- Data collection tools

- Global Health Observatory

- Insights and visualizations

- COVID excess deaths

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Questions and answers /

Food, genetically modified

These questions and answers have been prepared by WHO in response to questions and concerns from WHO Member State Governments with regard to the nature and safety of genetically modified food.

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) can be defined as organisms (i.e. plants, animals or microorganisms) in which the genetic material (DNA) has been altered in a way that does not occur naturally by mating and/or natural recombination. The technology is often called “modern biotechnology” or “gene technology”, sometimes also “recombinant DNA technology” or “genetic engineering”. It allows selected individual genes to be transferred from one organism into another, also between nonrelated species. Foods produced from or using GM organisms are often referred to as GM foods.

GM foods are developed – and marketed – because there is some perceived advantage either to the producer or consumer of these foods. This is meant to translate into a product with a lower price, greater benefit (in terms of durability or nutritional value) or both. Initially GM seed developers wanted their products to be accepted by producers and have concentrated on innovations that bring direct benefit to farmers (and the food industry generally).

One of the objectives for developing plants based on GM organisms is to improve crop protection. The GM crops currently on the market are mainly aimed at an increased level of crop protection through the introduction of resistance against plant diseases caused by insects or viruses or through increased tolerance towards herbicides.

Resistance against insects is achieved by incorporating into the food plant the gene for toxin production from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). This toxin is currently used as a conventional insecticide in agriculture and is safe for human consumption. GM crops that inherently produce this toxin have been shown to require lower quantities of insecticides in specific situations, e.g. where pest pressure is high. Virus resistance is achieved through the introduction of a gene from certain viruses which cause disease in plants. Virus resistance makes plants less susceptible to diseases caused by such viruses, resulting in higher crop yields.

Herbicide tolerance is achieved through the introduction of a gene from a bacterium conveying resistance to some herbicides. In situations where weed pressure is high, the use of such crops has resulted in a reduction in the quantity of the herbicides used.

Generally consumers consider that conventional foods (that have an established record of safe consumption over the history) are safe. Whenever novel varieties of organisms for food use are developed using the traditional breeding methods that had existed before the introduction of gene technology, some of the characteristics of organisms may be altered, either in a positive or a negative way. National food authorities may be called upon to examine the safety of such conventional foods obtained from novel varieties of organisms, but this is not always the case.

In contrast, most national authorities consider that specific assessments are necessary for GM foods. Specific systems have been set up for the rigorous evaluation of GM organisms and GM foods relative to both human health and the environment. Similar evaluations are generally not performed for conventional foods. Hence there currently exists a significant difference in the evaluation process prior to marketing for these two groups of food.

The WHO Department of Food Safety and Zoonoses aims at assisting national authorities in the identification of foods that should be subject to risk assessment and to recommend appropriate approaches to safety assessment. Should national authorities decide to conduct safety assessment of GM organisms, WHO recommends the use of Codex Alimentarius guidelines (See the answer to Question 11 below).

The safety assessment of GM foods generally focuses on: (a) direct health effects (toxicity), (b) potential to provoke allergic reaction (allergenicity); (c) specific components thought to have nutritional or toxic properties; (d) the stability of the inserted gene; (e) nutritional effects associated with genetic modification; and (f) any unintended effects which could result from the gene insertion.

While theoretical discussions have covered a broad range of aspects, the three main issues debated are the potentials to provoke allergic reaction (allergenicity), gene transfer and outcrossing.

Allergenicity

As a matter of principle, the transfer of genes from commonly allergenic organisms to non-allergic organisms is discouraged unless it can be demonstrated that the protein product of the transferred gene is not allergenic. While foods developed using traditional breeding methods are not generally tested for allergenicity, protocols for the testing of GM foods have been evaluated by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and WHO. No allergic effects have been found relative to GM foods currently on the market.

Gene transfer

Gene transfer from GM foods to cells of the body or to bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract would cause concern if the transferred genetic material adversely affects human health. This would be particularly relevant if antibiotic resistance genes, used as markers when creating GMOs, were to be transferred. Although the probability of transfer is low, the use of gene transfer technology that does not involve antibiotic resistance genes is encouraged.

Outcrossing

The migration of genes from GM plants into conventional crops or related species in the wild (referred to as “outcrossing”), as well as the mixing of crops derived from conventional seeds with GM crops, may have an indirect effect on food safety and food security. Cases have been reported where GM crops approved for animal feed or industrial use were detected at low levels in the products intended for human consumption. Several countries have adopted strategies to reduce mixing, including a clear separation of the fields within which GM crops and conventional crops are grown.

Environmental risk assessments cover both the GMO concerned and the potential receiving environment. The assessment process includes evaluation of the characteristics of the GMO and its effect and stability in the environment, combined with ecological characteristics of the environment in which the introduction will take place. The assessment also includes unintended effects which could result from the insertion of the new gene.

Issues of concern include: the capability of the GMO to escape and potentially introduce the engineered genes into wild populations; the persistence of the gene after the GMO has been harvested; the susceptibility of non-target organisms (e.g. insects which are not pests) to the gene product; the stability of the gene; the reduction in the spectrum of other plants including loss of biodiversity; and increased use of chemicals in agriculture. The environmental safety aspects of GM crops vary considerably according to local conditions.

Different GM organisms include different genes inserted in different ways. This means that individual GM foods and their safety should be assessed on a case-by-case basis and that it is not possible to make general statements on the safety of all GM foods.

GM foods currently available on the international market have passed safety assessments and are not likely to present risks for human health. In addition, no effects on human health have been shown as a result of the consumption of such foods by the general population in the countries where they have been approved. Continuous application of safety assessments based on the Codex Alimentarius principles and, where appropriate, adequate post market monitoring, should form the basis for ensuring the safety of GM foods.

The way governments have regulated GM foods varies. In some countries GM foods are not yet regulated. Countries which have legislation in place focus primarily on assessment of risks for consumer health. Countries which have regulatory provisions for GM foods usually also regulate GMOs in general, taking into account health and environmental risks, as well as control- and trade-related issues (such as potential testing and labelling regimes). In view of the dynamics of the debate on GM foods, legislation is likely to continue to evolve.

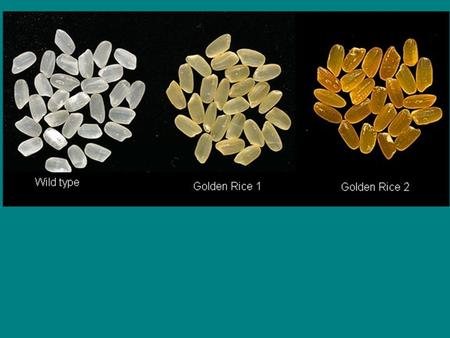

GM crops available on the international market today have been designed using one of three basic traits: resistance to insect damage; resistance to viral infections; and tolerance towards certain herbicides. GM crops with higher nutrient content (e.g. soybeans increased oleic acid) have been also studied recently.

The Codex Alimentarius Commission (Codex) is the joint FAO/WHO intergovernmental body responsible for developing the standards, codes of practice, guidelines and recommendations that constitute the Codex Alimentarius, meaning the international food code. Codex developed principles for the human health risk analysis of GM foods in 2003.

Principles for the risk analysis of foods derived from modern biotechnology

The premise of these principles sets out a premarket assessment, performed on a caseby- case basis and including an evaluation of both direct effects (from the inserted gene) and unintended effects (that may arise as a consequence of insertion of the new gene) Codex also developed three Guidelines:

Guideline for the conduct of food safety assessment of foods derived from recombinant-DNA plants

Guideline for the conduct of food safety assessment of foods produced using recombinant-DNA microorganisms

Guideline for the conduct of food safety assessment of foods derived from recombinant-DNA animals

Codex principles do not have a binding effect on national legislation, but are referred to specifically in the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures of the World Trade Organization (SPS Agreement), and WTO Members are encouraged to harmonize national standards with Codex standards. If trading partners have the same or similar mechanisms for the safety assessment of GM foods, the possibility that one product is approved in one country but rejected in another becomes smaller.

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, an environmental treaty legally binding for its Parties which took effect in 2003, regulates transboundary movements of Living Modified Organisms (LMOs). GM foods are within the scope of the Protocol only if they contain LMOs that are capable of transferring or replicating genetic material. The cornerstone of the Protocol is a requirement that exporters seek consent from importers before the first shipment of LMOs intended for release into the environment.

The GM products that are currently on the international market have all passed safety assessments conducted by national authorities. These different assessments in general follow the same basic principles, including an assessment of environmental and human health risk. The food safety assessment is usually based on Codex documents.

Since the first introduction on the market in the mid-1990s of a major GM food (herbicide-resistant soybeans), there has been concern about such food among politicians, activists and consumers, especially in Europe. Several factors are involved. In the late 1980s – early 1990s, the results of decades of molecular research reached the public domain. Until that time, consumers were generally not very aware of the potential of this research. In the case of food, consumers started to wonder about safety because they perceive that modern biotechnology is leading to the creation of new species.

Consumers frequently ask, “what is in it for me?”. Where medicines are concerned, many consumers more readily accept biotechnology as beneficial for their health (e.g. vaccines, medicines with improved treatment potential or increased safety). In the case of the first GM foods introduced onto the European market, the products were of no apparent direct benefit to consumers (not significantly cheaper, no increased shelflife, no better taste). The potential for GM seeds to result in bigger yields per cultivated area should lead to lower prices. However, public attention has focused on the risk side of the risk-benefit equation, often without distinguishing between potential environmental impacts and public health effects of GMOs.

Consumer confidence in the safety of food supplies in Europe has decreased significantly as a result of a number of food scares that took place in the second half of the 1990s that are unrelated to GM foods. This has also had an impact on discussions about the acceptability of GM foods. Consumers have questioned the validity of risk assessments, both with regard to consumer health and environmental risks, focusing in particular on long-term effects. Other topics debated by consumer organizations have included allergenicity and antimicrobial resistance. Consumer concerns have triggered a discussion on the desirability of labelling GM foods, allowing for an informed choice of consumers.

The release of GMOs into the environment and the marketing of GM foods have resulted in a public debate in many parts of the world. This debate is likely to continue, probably in the broader context of other uses of biotechnology (e.g. in human medicine) and their consequences for human societies. Even though the issues under debate are usually very similar (costs and benefits, safety issues), the outcome of the debate differs from country to country. On issues such as labelling and traceability of GM foods as a way to address consumer preferences, there is no worldwide consensus to date. Despite the lack of consensus on these topics, the Codex Alimentarius Commission has made significant progress and developed Codex texts relevant to labelling of foods derived from modern biotechnology in 2011 to ensure consistency on any approach on labelling implemented by Codex members with already adopted Codex provisions.

Depending on the region of the world, people often have different attitudes to food. In addition to nutritional value, food often has societal and historical connotations, and in some instances may have religious importance. Technological modification of food and food production may evoke a negative response among consumers, especially in the absence of sound risk communication on risk assessment efforts and cost/benefit evaluations.

Yes, intellectual property rights are likely to be an element in the debate on GM foods, with an impact on the rights of farmers. In the FAO/WHO expert consultation in 2003 , WHO and FAO have considered potential problems of the technological divide and the unbalanced distribution of benefits and risks between developed and developing countries and the problem often becomes even more acute through the existence of intellectual property rights and patenting that places an advantage on the strongholds of scientific and technological expertise. Such considerations are likely to also affect the debate on GM foods.

Certain groups are concerned about what they consider to be an undesirable level of control of seed markets by a few chemical companies. Sustainable agriculture and biodiversity benefit most from the use of a rich variety of crops, both in terms of good crop protection practices as well as from the perspective of society at large and the values attached to food. These groups fear that as a result of the interest of the chemical industry in seed markets, the range of varieties used by farmers may be reduced mainly to GM crops. This would impact on the food basket of a society as well as in the long run on crop protection (for example, with the development of resistance against insect pests and tolerance of certain herbicides). The exclusive use of herbicide-tolerant GM crops would also make the farmer dependent on these chemicals. These groups fear a dominant position of the chemical industry in agricultural development, a trend which they do not consider to be sustainable.

Future GM organisms are likely to include plants with improved resistance against plant disease or drought, crops with increased nutrient levels, fish species with enhanced growth characteristics. For non-food use, they may include plants or animals producing pharmaceutically important proteins such as new vaccines.

WHO has been taking an active role in relation to GM foods, primarily for two reasons:

on the grounds that public health could benefit from the potential of biotechnology, for example, from an increase in the nutrient content of foods, decreased allergenicity and more efficient and/or sustainable food production; and

based on the need to examine the potential negative effects on human health of the consumption of food produced through genetic modification in order to protect public health. Modern technologies should be thoroughly evaluated if they are to constitute a true improvement in the way food is produced.

WHO, together with FAO, has convened several expert consultations on the evaluation of GM foods and provided technical advice for the Codex Alimentarius Commission which was fed into the Codex Guidelines on safety assessment of GM foods. WHO will keep paying due attention to the safety of GM foods from the view of public health protection, in close collaboration with FAO and other international bodies.

Food, Genetically modified

- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- Resources for You (Food)

- Agricultural Biotechnology

Science and History of GMOs and Other Food Modification Processes

Feed Your Mind Main Page

en Español (Spanish)

How has genetic engineering changed plant and animal breeding?

Did you know.

Genetic engineering is often used in combination with traditional breeding to produce the genetically engineered plant varieties on the market today.

For thousands of years, humans have been using traditional modification methods like selective breeding and cross-breeding to breed plants and animals with more desirable traits. For example, early farmers developed cross-breeding methods to grow corn with a range of colors, sizes, and uses. Today’s strawberries are a cross between a strawberry species native to North America and a strawberry species native to South America.

Most of the foods we eat today were created through traditional breeding methods. But changing plants and animals through traditional breeding can take a long time, and it is difficult to make very specific changes. After scientists developed genetic engineering in the 1970s, they were able to make similar changes in a more specific way and in a shorter amount of time.

A Timeline of Genetic Modification in Agriculture

A Timeline of Genetic Modification in Modern Agriculture

Circa 8000 BCE: Humans use traditional modification methods like selective breeding and cross-breeding to breed plants and animals with more desirable traits.

1866: Gregor Mendel, an Austrian monk, breeds two different types of peas and identifies the basic process of genetics.

1922: The first hybrid corn is produced and sold commercially.

1940: Plant breeders learn to use radiation or chemicals to randomly change an organism’s DNA.

1953: Building on the discoveries of chemist Rosalind Franklin, scientists James Watson and Francis Crick identify the structure of DNA.

1973: Biochemists Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen develop genetic engineering by inserting DNA from one bacteria into another.

1982: FDA approves the first consumer GMO product developed through genetic engineering: human insulin to treat diabetes.

1986: The federal government establishes the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology. This policy describes how the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) work together to regulate the safety of GMOs.

1992: FDA policy states that foods from GMO plants must meet the same requirements, including the same safety standards, as foods derived from traditionally bred plants.

1994: The first GMO produce created through genetic engineering—a GMO tomato—becomes available for sale after studies evaluated by federal agencies proved it to be as safe as traditionally bred tomatoes.

1990s: The first wave of GMO produce created through genetic engineering becomes available to consumers: summer squash, soybeans, cotton, corn, papayas, tomatoes, potatoes, and canola. Not all are still available for sale.

2003: The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations develop international guidelines and standards to determine the safety of GMO foods.

2005: GMO alfalfa and sugar beets are available for sale in the United States.

2015: FDA approves an application for the first genetic modification in an animal for use as food, a genetically engineered salmon.

2016: Congress passes a law requiring labeling for some foods produced through genetic engineering and uses the term “bioengineered,” which will start to appear on some foods.

2017: GMO apples are available for sale in the U.S.

2019: FDA completes consultation on first food from a genome edited plant.

2020 : GMO pink pineapple is available to U.S. consumers.

2020 : Application for GalSafe pig was approved.

How are GMOs made?

“GMO” (genetically modified organism) has become the common term consumers and popular media use to describe foods that have been created through genetic engineering. Genetic engineering is a process that involves:

- Identifying the genetic information—or “gene”—that gives an organism (plant, animal, or microorganism) a desired trait

- Copying that information from the organism that has the trait

- Inserting that information into the DNA of another organism

- Then growing the new organism

How Are GMOs Made? Fact Sheet

Making a GMO Plant, Step by Step

The following example gives a general idea of the steps it takes to create a GMO plant. This example uses a type of insect-resistant corn called “Bt corn.” Keep in mind that the processes for creating a GMO plant, animal, or microorganism may be different.

To produce a GMO plant, scientists first identify what trait they want that plant to have, such as resistance to drought, herbicides, or insects. Then, they find an organism (plant, animal, or microorganism) that already has that trait within its genes. In this example, scientists wanted to create insect-resistant corn to reduce the need to spray pesticides. They identified a gene in a soil bacterium called Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) , which produces a natural insecticide that has been in use for many years in traditional and organic agriculture.

After scientists find the gene with the desired trait, they copy that gene.

For Bt corn, they copied the gene in Bt that would provide the insect-resistance trait.

Next, scientists use tools to insert the gene into the DNA of the plant. By inserting the Bt gene into the DNA of the corn plant, scientists gave it the insect resistance trait.

This new trait does not change the other existing traits.

In the laboratory, scientists grow the new corn plant to ensure it has adopted the desired trait (insect resistance). If successful, scientists first grow and monitor the new corn plant (now called Bt corn because it contains a gene from Bacillus thuringiensis) in greenhouses and then in small field tests before moving it into larger field tests. GMO plants go through in-depth review and tests before they are ready to be sold to farmers.

The entire process of bringing a GMO plant to the marketplace takes several years.

Learn more about the process for creating genetically engineered microbes and genetically engineered animals .

What are the latest scientific advances in plant and animal breeding?

Scientists are developing new ways to create new varieties of crops and animals using a process called genome editing . These techniques can make changes more quickly and precisely than traditional breeding methods.

There are several genome editing tools, such as CRISPR . Scientists can use these newer genome editing tools to make crops more nutritious, drought tolerant, and resistant to insect pests and diseases.

Learn more about Genome Editing in Agricultural Biotechnology .

How GMOs Are Regulated in the United States

GMO Crops, Animal Food, and Beyond

How GMO Crops Impact Our World

www.fda.gov/feedyourmind

Accept cookies?

We use cook ies to give you the best online experience and to show personalised content and marketing. We use them to improve our website and content as well as to tailor our digital advertising on third-party platforms. You can change your preferences at any time.

Popular search terms:

- British wildlife

- Wildlife Photographer of the Year

- Explore the Museum

- Anthropocene

British Wildlife

Collections

Human evolution

What on Earth?

Farmers of the future face a big challenge: feeding Earth's expanding population while minimising environmental impacts and keeping food affordable. Image: Varga Jozsef Zoltan/ Shutterstock.com .

During Beta testing articles may only be saved for seven days.

Create a list of articles to read later. You will be able to access your list from any article in Discover.

You don't have any saved articles.

The future of eating: how genetically modified food will withstand climate change

Climate change is transforming how we feed ourselves. Floods, droughts and new diseases can have a big impact on the crops we rely on for food, including staples such as wheat, maize and rice.

Future farmers face a big challenge: feeding everyone on Earth while being kind to the planet. Could genetically modified food be the answer?

Discover which foods can be genetically modified, how they can be improved, and whether people should worry about eating them.

What is genetically modified food?

Genetically modified crops are plants which have had their DNA changed by scientists to create desired traits, often by adding just one gene from a close wild relative.

For example, GM crops can be engineered to require less water to grow or to resist diseases or pests. More ambitious projects are underway to engineer crops that make their own fertiliser. This type of technology could be key in making some of our most important food crops more resilient in the face of climate change , and it could decrease the chemicals and energy needed to grow them.

Wheat is the most commonly grown crop across the world by acreage. Image: ESB Professional/ Shutterstock.com .

Wheat is the most commonly grown crop across the world by acreage. It is often used to make bread, pasta and noodles, and also feeds livestock.

Helping to find ways to meet this demand is Prof Matt Clark, a Museum research leader who is studying wheat DNA.

It took over 600 scientists working together to finally sequence the wheat genome in 2018 . This was once thought to difficult to do, as the wheat genome is five times bigger than the human one. By understanding and changing wheat genomes, scientists like Matt will help to protect the crop for future generations. Breeders will be able to select traits which will improve wheat harvests and help to secure food stores for billions of people around the world.

Wheat can be bred to withstand severe weather and disease, both of which could become more common as the world warms.

Wheat strains are also being adapted to produce flour with increased iron levels. The ongoing trial, which is being carried out at the John Innes Centre in Norwich, has shown that the new grain contained double the amount of iron compared to a normal grain. This could help to reduce levels of iron deficiency-related anaemia globally. Anaemia is especially common in girls and young women.

Maize, sometimes referred to as corn in the US and Canada, has seen demand surge globally because it is used to feed animals and to create new fuels. Image: naramit/ Shutterstock.com .

Maize, sometimes referred to as corn in the US and Canada, has seen demand surge globally because it is used to feed animals and to create new fuels.

In 2019, researchers in Delaware, USA, successfully increased corn yields by 10% by changing the gene that controls its growth. This modification has proved successful even in poor conditions: plants were given bigger leaves to improve how they turn sunlight into sugar and boost how efficient they are at using nitrogen in the soil.

Genetic modification can have unexpected positive effects, too. Corn which has been engineered to require fewer pesticides may also be safer for humans and animals to eat. That's because corn damaged by insects contains fumonisins - toxins generated by fungi introduced to the corn by insects - which are thought to cause cancer. There is a link between people who eat lots of corn, such as populations in South Africa, China and Italy, and higher rates of oesophageal cancer.

Rice is the main food source for three billion people. Image: Chaded Panichsri/ Shutterstock.com .

Around 20% of calories consumed across the world come from rice, and it is the main food source for three billion people. Yet the places where rice is most often grown, including areas of India, Bangladesh and China, are constantly at risk of flooding. Rising sea levels and increasingly intense tropical storms mean that this problem is only going to worsen.

One solution to this is scuba rice, which can withstand being soaked in flood water and has been successfully grown in southeast Asia.

Genetic modification can also make rice kinder to nature. Rice paddy fields are a big source of the greenhouse gas methane, but the creation of the SUSIBA2 variety is helping. This rice contains a gene from the barley plant, which can help to reduce methane emissions. A three-year trial showed that this method increased yield by 10% while reducing methane emissions.

The aim of the C4 Rice Project, led by a team from 12 universities across eight countries, is to engineer C4 photosynthesis, meaning to convert the energy from sunlight into rice. C4 photosynthesis is up to 50% more water-efficient than other types of rice and naturally occurs in drought-tolerant or very fast-growing plant species such as bamboo.

The University of Sheffield is one of several institutions working on growing rice with fewer stomata, the tiny openings used for gas exchange. This will result in less water being lost and better performance in exceptionally hot or wet conditions. Results so far show that lower stomatal density means that 60% less water is used. When 4,000 litres of water are needed to grow a kilogram of rice, and rice uses 70% of the agricultural water supply in China, this could be a significant saving.

Dr Haiyan Xiong, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge, is working on a similar strategy. Her PhD and postdoctoral work in China focussed on introducing the drought-resistant gene found in upland rice (which grows in dry and hilly conditions) into lowland rice. Lowland rice tends to be better quality but less hardy, so aims to merge the desirable traits of both crops.

So far, Xiong's team has identified three genes which could help make rice more resistant to drought. Her current work at the University of Cambridge is aimed at changing rice plants so they are better at converting the energy from sunlight into food.

Xiong's upbringing in rural Sichuan drew her to a career researching rice. She witnessed drought conditions first-hand, which led to a dream of 'becoming a scientist who can contribute to improving rice resistance to drought stress'. She says, 'Rice is not only one of the most important food crops in the world - it is also a model plant for studying other cereal crops.'

Around 45% of this soya is crushed to produce oil and meals which are then exported globally. Image: nnattalli/ Shutterstock .com

Soya beans are the Americas' most exported crop, making up 82% of its agricultural exports. Around 45% of this soya is crushed to produce oil and meals which are then exported globally. Among these crops are genetically modified soybeans, which have been spliced with the pigeonpea gene to increase resistance to Asian soybean rust (ASR). ASR is caused by a fungus and is one of the most common crop diseases, only treatable by introducing the fungi-resistant trait of other legumes to increase resistance and improve crop yields.

There is no sure-fire way to make agriculture more sustainable, but GM crops are helping farmers to adapt to the issues presented by climate change. Image: Varga Jozsef Zoltan/ Shutterstock.com.

What are the issues surrounding GM crops?

Some people are wary of GM crops, often due to concerns about the cost of seeds, issues surrounding herbicide resistance and worries about allergens and safety. There are also fears that crossing species could inadvertently introduce allergens such as nuts into the food chain. This fear appears unfounded, as to date no adverse reactions have been found in any approved GM products.

Others worry that modified plants could pollinate wild varieties and cause hybrids to pop up. For this to happen, the GM trait would need to be able to survive in the wild, which is not always the case, and GM crops can be designed to be sterile.

In fact, research has shown that there is nothing that differentiates GM crops from naturally occurring ones in terms of health or safety. GM crops can be a force for good by offering an alternative to spraying pesticides that pollute groundwater and can kill surrounding crops.

Globally, GM crop uptake is divided. In some regions, billions of people have eaten GM crops for decades, whereas the European Union is generally resistant to the use of GM foods, though it does import GM animal feed. Many European countries including France, Germany and Croatia have completely banned GM foods. Others such as Spain, the Czech Republic and Portugal grow GM crops.

The USA is one of the widest growers and adopters of GM foods with 60% of processed foods containing ingredients from engineered soy, corn or canola.

Looking to the future

What does the future of genetically modified crops hold? The Alliance for Science at Cornell University in the USA is currently working on corn which can resist insects and drought for use in Africa. If farmers plant corn which could do this organically, they could save money on fertiliser and pesticides. Funded by charities including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, it should be available to farmers by 2023.

New gene editing tools such as CRISPR can be used to precision-edit genetic material, even to the level of changing a single base of DNA. This has the potential for enormous worldwide benefits. For this reason the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to the discoverers of CRISPR: Profs Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna.

There is no magic fix to climate change and no sure-fire way to make agriculture more sustainable, but GM crops are helping farmers to adapt to the issues presented by climate change. These crops can result in better yields and survive droughts and floods, helping to make sure there is enough food available for an increasing global population while also reducing the carbon footprint of agriculture.

- Sustainability

- Our Broken Planet

- Biodiversity

- Climate change

Related posts

Why you should care about scientists sequencing the wheat genome

Sequencing the wheat genome could help to protect food supplies in the future.

Sugar: a killer crop?

The world's sugar addiction is destroying tropical rainforest.

What is climate change and why does it matter?

What does this term mean and how could it affect you?

Soil degradation: the problems and how to fix them

The world is running out of soil - here's why that's a problem.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice .

Follow us on social media

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Food Sci Technol

- v.50(6); 2013 Dec

Genetically modified foods: safety, risks and public concerns—a review

Defence Food Research Laboratory, Siddarthanagar, Mysore, 570011 India

K. R. Anilakumar

Genetic modification is a special set of gene technology that alters the genetic machinery of such living organisms as animals, plants or microorganisms. Combining genes from different organisms is known as recombinant DNA technology and the resulting organism is said to be ‘Genetically modified (GM)’, ‘Genetically engineered’ or ‘Transgenic’. The principal transgenic crops grown commercially in field are herbicide and insecticide resistant soybeans, corn, cotton and canola. Other crops grown commercially and/or field-tested are sweet potato resistant to a virus that could destroy most of the African harvest, rice with increased iron and vitamins that may alleviate chronic malnutrition in Asian countries and a variety of plants that are able to survive weather extremes. There are bananas that produce human vaccines against infectious diseases such as hepatitis B, fish that mature more quickly, fruit and nut trees that yield years earlier and plants that produce new plastics with unique properties. Technologies for genetically modifying foods offer dramatic promise for meeting some areas of greatest challenge for the 21st century. Like all new technologies, they also pose some risks, both known and unknown. Controversies and public concern surrounding GM foods and crops commonly focus on human and environmental safety, labelling and consumer choice, intellectual property rights, ethics, food security, poverty reduction and environmental conservation. With this new technology on gene manipulation what are the risks of “tampering with Mother Nature”?, what effects will this have on the environment?, what are the health concerns that consumers should be aware of? and is recombinant technology really beneficial? This review will also address some major concerns about the safety, environmental and ecological risks and health hazards involved with GM foods and recombinant technology.

Introduction

Scientists first discovered in 1946 that DNA can be transferred between organisms (Clive 2011 ). It is now known that there are several mechanisms for DNA transfer and that these occur in nature on a large scale, for example, it is a major mechanism for antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria. The first genetically modified (GM) plant was produced in 1983, using an antibiotic-resistant tobacco plant. China was the first country to commercialize a transgenic crop in the early 1990s with the introduction of virus resistant tobacco. In 1994, the transgenic ‘Flavour Saver tomato’ was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for marketing in the USA. The modification allowed the tomato to delay ripening after picking. In 1995, few transgenic crops received marketing approval. This include canola with modified oil composition (Calgene), Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) corn/maize (Ciba-Geigy), cotton resistant to the herbicide bromoxynil (Calgene), Bt cotton (Monsanto), Bt potatoes (Monsanto), soybeans resistant to the herbicide glyphosate (Monsanto), virus-resistant squash (Asgrow) and additional delayed ripening tomatoes (DNAP, Zeneca/Peto, and Monsanto) (Clive 2011 ). A total of 35 approvals had been granted to commercially grow 8 transgenic crops and one flower crop of carnations with 8 different traits in 6 countries plus the EU till 1996 (Clive 1996 ). As of 2011, the USA leads a list of multiple countries in the production of GM crops. Currently, there are a number of food species in which a genetically modified version exists (Johnson 2008 ). Some of the foods that are available in the market include cotton, soybean, canola, potatoes, eggplant, strawberries, corn, tomatoes, lettuce, cantaloupe, carrots etc. GM products which are currently in the pipeline include medicines and vaccines, foods and food ingredients, feeds and fibres. Locating genes for important traits, such as those conferring insect resistance or desired nutrients-is one of the most limiting steps in the process.

Foods derived from GM crops

At present there are several GM crops used as food sources. As of now there are no GM animals approved for use as food, but a GM salmon has been proposed for FDA approval. In instances, the product is directly consumed as food, but in most of the cases, crops that have been genetically modified are sold as commodities, which are further processed into food ingredients.

Fruits and vegetables

Papaya has been developed by genetic engineering which is ring spot virus resistant and thus enhancing the productivity. This was very much in need as in the early 1990s the Hawaii’s papaya industry was facing disaster because of the deadly papaya ring spot virus. Its single-handed savior was a breed engineered to be resistant to the virus. Without it, the state’s papaya industry would have collapsed. Today 80 % of Hawaiian papaya is genetically engineered, and till now no conventional or organic method is available to control ring spot virus.

The NewLeaf™ potato, a GM food developed using naturally-occurring bacteria found in the soil known as Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), was made to provide in-plant protection from the yield-robbing Colorado potato beetle. This was brought to market by Monsanto in the late 1990s, developed for the fast food market. This was forced to withdraw from the market in 2001as the fast food retailers did not pick it up and thereby the food processors ran into export problems. Reports say that currently no transgenic potatoes are marketed for the purpose of human consumption. However, BASF, one of the leading suppliers of plant biotechnology solutions for agriculture requested for the approval for cultivation and marketing as a food and feed for its ‘Fortuna potato’. This GM potato was made resistant to late blight by adding two resistance genes, blb1 and blb2, which was originated from the Mexican wild potato Solanum bulbocastanum . As of 2005, about 13 % of the zucchini grown in the USA is genetically modified to resist three viruses; the zucchini is also grown in Canada (Johnson 2008 ).

Vegetable oil

It is reported that there is no or a significantly small amount of protein or DNA remaining in vegetable oil extracted from the original GM crops in USA. Vegetable oil is sold to consumers as cooking oil, margarine and shortening, and is used in prepared foods. Vegetable oil is made of triglycerides extracted from plants or seeds and then refined, and may be further processed via hydrogenation to turn liquid oils into solids. The refining process removes nearly all non-triglyceride ingredients (Crevel et al. 2000 ). Cooking oil, margarine and shortening may also be made from several crops. A large percentage of Canola produced in USA is GM and is mainly used to produce vegetable oil. Canola oil is the third most widely consumed vegetable oil in the world. The genetic modifications are made for providing resistance to herbicides viz. glyphosate or glufosinate and also for improving the oil composition. After removing oil from canola seed, which is ∼43 %, the meal has been used as high quality animal feed. Canola oil is a key ingredient in many foods and is sold directly to consumers as margarine or cooking oil. The oil has many non-food uses, which includes making lipsticks.

Maize, also called corn in the USA and cornmeal, which is ground and dried maize constitute a staple food in many regions of the world. Grown since 1997 in the USA and Canada, 86 % of the USA maize crop was genetically modified in 2010 (Hamer and Scuse 2010 ) and 32 % of the worldwide maize crop was GM in 2011 (Clive 2011 ). A good amount of the total maize harvested go for livestock feed including the distillers grains. The remaining has been used for ethanol and high fructose corn syrup production, export, and also used for other sweeteners, cornstarch, alcohol, human food or drink. Corn oil is sold directly as cooking oil and to make shortening and margarine, in addition to make vitamin carriers, as a source of lecithin, as an ingredient in prepared foods like mayonnaise, sauces and soups, and also to fry potato chips and French fries. Cottonseed oil is used as a salad and cooking oil, both domestically and industrially. Nearly 93 % of the cotton crop in USA is GM.

The USA imports 10 % of its sugar from other countries, while the remaining 90 % is extracted from domestically grown sugar beet and sugarcane. Out of the domestically grown sugar crops, half of the extracted sugar is derived from sugar beet, and the other half is from sugarcane. After deregulation in 2005, glyphosate-resistant sugar beet was extensively adopted in the USA. In USA 95 % of sugar beet acres were planted with glyphosate-resistant seed (Clive 2011 ). Sugar beets that are herbicide-tolerant have been approved in Australia, Canada, Colombia, EU, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Russian Federation, Singapore and USA. The food products of sugar beets are refined sugar and molasses. Pulp remaining from the refining process is used as animal feed. The sugar produced from GM sugar beets is highly refined and contains no DNA or protein—it is just sucrose, the same as sugar produced from non-GM sugar beets (Joana et al. 2010 ).

Quantification of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in foods

Testing on GMOs in food and feed is routinely done using molecular techniques like DNA microarrays or qPCR. These tests are based on screening genetic elements like p35S, tNos, pat, or bar or event specific markers for the official GMOs like Mon810, Bt11, or GT73. The array based method combines multiplex PCR and array technology to screen samples for different potential GMO combining different approaches viz. screening elements, plant-specific markers, and event-specific markers. The qPCR is used to detect specific GMO events by usage of specific primers for screening elements or event specific markers. Controls are necessary to avoid false positive or false negative results. For example, a test for CaMV is used to avoid a false positive in the event of a virus contaminated sample.

Joana et al. ( 2010 ) reported the extraction and detection of DNA along with a complete industrial soybean oil processing chain to monitor the presence of Roundup Ready (RR) soybean. The amplification of soybean lectin gene by end-point polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was achieved in all the steps of extraction and refining processes. The amplification of RR soybean by PCR assays using event specific primers was also achieved for all the extraction and refining steps. This excluded the intermediate steps of refining viz. neutralization, washing and bleaching possibly due to sample instability. The real-time PCR assays using specific probes confirmed all the results and proved that it is possible to detect and quantify GMOs in the fully refined soybean oil.

Figure 1 gives the overall protocol for the testing of GMOs. This is based on a PCR detection system specific for 35S promoter region originating from cauliflower mosaic virus (Deisingh and Badrie 2005 ). The 35S-PCR technique permits detection of GMO contents of foods and raw materials in the range of 0.01–0.1 %. The development of quantitative detection systems such as quantitative competitive PCR (QC-PCR), real-time PCR and ELISA systems resulted in the advantage of survival of DNA in most manufacturing processes. Otherwise with ELISA, there can be protein denaturing during food processing. Inter-laboratory differences were found to be less with the QC-PCR than with quantitative PCR probably due to insufficient homogenisation of the sample. However, there are disadvantages, the major one being the amount of DNA, which could be amplified, is affected by food processing techniques and can vary up to 5-fold. Thus, results need to be normalised by using plant-specific QC-PCR system. Further, DNA, which cannot be amplified, will affect all quantitative PCR detection systems.

Protocol for the testing of genetically modified foods

In a recent work La Mura et al. ( 2011 ) applied QUIZ (quantization using informative zeros) to estimate the contents of RoundUp Ready™ soya and MON810 in processed food containing one or both GMs. They reported that the quantification of GM in samples can be performed without the need for certified reference materials using QUIZ. Results showed good agreement between derived values and known input of GM material and compare favourably with quantitative real-time PCR. Detection of Roundup Ready soybean by loop-mediated isothermal amplification combined with a lateral-flow dipstick has been reported recently (Xiumin et al. 2012 ).

GM foods-merits and demerits

Before we think of having GM foods it is very important to know about is advantages and disadvantages especially with respect to its safety. These foods are made by inserting genes of other species into their DNA. Though this kind of genetic modification is used both in plants and animals, it is found more commonly in the former than in the latter. Experts are working on developing foods that have the ability to alleviate certain disorders and diseases. Though researchers and the manufacturers make sure that there are various advantages of consuming these foods, a fair bit of the population is entirely against them.

GM foods are useful in controlling the occurrence of certain diseases. By modifying the DNA system of these foods, the properties causing allergies are eliminated successfully. These foods grow faster than the foods that are grown traditionally. Probably because of this, the increased productivity provides the population with more food. Moreover these foods are a boon in places which experience frequent droughts, or where the soil is incompetent for agriculture. At times, genetically engineered food crops can be grown at places with unfavourable climatic conditions too. A normal crop can grow only in specific season or under some favourable climatic conditions. Though the seeds for such foods are quite expensive, their cost of production is reported to be less than that of the traditional crops due to the natural resistance towards pests and insects. This reduces the necessity of exposing GM crops to harmful pesticides and insecticides, making these foods free from chemicals and environment friendly as well. Genetically engineered foods are reported to be high in nutrients and contain more minerals and vitamins than those found in traditionally grown foods. Other than this, these foods are known to taste better. Another reason for people opting for genetically engineered foods is that they have an increased shelf life and hence there is less fear of foods getting spoiled quickly.

The biggest threat caused by GM foods is that they can have harmful effects on the human body. It is believed that consumption of these genetically engineered foods can cause the development of diseases which are immune to antibiotics. Besides, as these foods are new inventions, not much is known about their long term effects on human beings. As the health effects are unknown, many people prefer to stay away from these foods. Manufacturers do not mention on the label that foods are developed by genetic manipulation because they think that this would affect their business, which is not a good practice. Many religious and cultural communities are against such foods because they see it as an unnatural way of producing foods. Many people are also not comfortable with the idea of transferring animal genes into plants and vice versa. Also, this cross-pollination method can cause damage to other organisms that thrive in the environment. Experts are also of the opinion that with the increase of such foods, developing countries would start depending more on industrial countries because it is likely that the food production would be controlled by them in the time to come.

Safety tests on commercial GM crops

The GM tomatoes were produced by inserting kanr genes into a tomato by an ‘antisense’ GM method (IRDC 1998 ). The results show that there were no significant alterations in total protein, vitamins and mineral contents and in toxic glycoalkaloids (Redenbaugh et al. 1992 ). Therefore, the GM and parent tomatoes were deemed to be “substantially equivalent”. In acute toxicity studies with male/female rats, which were tube-fed with homogenized GM tomatoes, toxic effects were reported to be absent. A study with a GM tomato expressing B. thuringiensis toxin CRYIA (b) was underlined by the immunocytochemical demonstration of in vitro binding of Bt toxin to the caecum/colon from humans and rhesus monkeys (Noteborn et al. 1995 ).

Two lines of Chardon LL herbicide-resistant GM maize expressing the gene of phosphinothricin acetyltransferase before and after ensiling showed significant differences in fat and carbohydrate contents compared with non-GM maize and were therefore substantially different come. Toxicity tests were only performed with the maize even though with this the unpredictable effects of the gene transfer or the vector or gene insertion could not be demonstrated or excluded. The design of these experiments was also flawed because of poor digestibility and reduction in feed conversion efficiency of GM corn. One broiler chicken feeding study with rations containing transgenic Event 176 derived Bt corn (Novartis) has been published (Brake and Vlachos 1998 ). However, the results of this trial are more relevant to commercial than academic scientific studies.

GM soybeans

To make soybeans herbicide resistant, the gene of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase from Agrobacterium was used. Safety tests claim the GM variety to be “substantially equivalent” to conventional soybeans (Padgette et al. 1996 ). The same was claimed for GTS (glyphosate-resistant soybeans) sprayed with this herbicide (Taylor et al. 1999 ). However, several significant differences between the GM and control lines were recorded (Padgette et al. 1996 ) and the study showed statistically significant changes in the contents of genistein (isoflavone) with significant importance for health (Lappe et al. 1999 ) and increased content in trypsin inhibitor.

Studies have been conducted on the feeding value (Hammond et al. 1996 ) and possible toxicity (Harrison et al. 1996 ) for rats, broiler chickens, catfish and dairy cows of two GM lines of glyphosate-resistant soybean (GTS). The growth, feed conversion efficiency, catfish fillet composition, broiler breast muscle and fat pad weights and milk production, rumen fermentation and digestibilities in cows were found to be similar for GTS and non-GTS. These studies had the following lacunae: (a) No individual feed intakes, body or organ weights were given and histology studies were qualitative microscopy on the pancreas, (b) The feeding value of the two GTS lines was not substantially equivalent either because the rats/catfish grew significantly better on one of the GTS lines than on the other, (c) The design of study with broiler chicken was not much convincing, (d) Milk production and performance of lactating cows also showed significant differences between cows fed GM and non-GM feeds and (e) Testing of the safety of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase, which renders soybeans glyphosate-resistant (Harrison et al. 1996 ), was irrelevant because in the gavage studies an E. coli recombinant and not the GTS product were used. In a separate study (Teshima et al. 2000 ), it was claimed that rats and mice which were fed 30 % toasted GTS or non-GTS in their diet had no significant differences in nutritional performance, organ weights, histopathology and production of IgE and IgG antibodies.

GM potatoes

There were no improvements in the protein content or amino acid profile of GM potatoes (Hashimoto et al. 1999a ). In a short feeding study to establish the safety of GM potatoes expressing the soybean glycinin gene, rats were daily force-fed with 2 g of GM or control potatoes/kg body weight (Hashimoto et al 1999b ). No differences in growth, feed intake, blood cell count and composition and organ weights between the groups were found. In this study, the intake of potato by animals was reported to be too low (Pusztai 2001 ).

Feeding mice with potatoes transformed with a Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki Cry1 toxin gene or the toxin itself was shown to have caused villus epithelial cell hypertrophy and multinucleation, disrupted microvilli, mitochondrial degeneration, increased numbers of lysosomes and autophagic vacuoles and activation of crypt Paneth cells (Fares and El-Sayed 1998 ). The results showed CryI toxin which was stable in the mouse gut. Growing rats pair-fed on iso -proteinic and iso -caloric balanced diets containing raw or boiled non-GM potatoes and GM potatoes with the snowdrop ( Galanthus nivalis ) bulb lectin (GNA) gene (Ewen and Pusztai 1999 ) showed significant increase in the mucosal thickness of the stomach and the crypt length of the intestines of rats fed GM potatoes. Most of these effects were due to the insertion of the construct used for the transformation or the genetic transformation itself and not to GNA which had been pre-selected as a non-mitotic lectin unable to induce hyperplastic intestinal growth (Pusztai et al. 1990 ) and epithelial T lymphocyte infiltration.

The kind that expresses soybean glycinin gene (40–50 mg glycinin/g protein) was developed (Momma et al. 1999 ) and was claimed to contain 20 % more protein. However, the increased protein content was found probably due to a decrease in moisture rather than true increase in protein.

Several lines of GM cotton plants have been developed using a gene from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki providing increased protection against major lepidopteran pests. The lines were claimed to be “substantially equivalent” to parent lines (Berberich et al. 1996 ) in levels of macronutrients and gossypol. Cyclopropenoid fatty acids and aflatoxin levels were less than those in conventional seeds. However, because of the use of inappropriate statistics it was questionable whether the GM and non-GM lines were equivalent, particularly as environmental stresses could have unpredictable effects on anti-nutrient/toxin levels (Novak and Haslberger 2000 ).

The nutritional value of diets containing GM peas expressing bean alpha-amylase inhibitor when fed to rats for 10 days at two different doses viz. 30 % and 65 % was shown to be similar to that of parent-line peas (Pusztai et al. 1999 ). At the same time in order to establish its safety for humans a more rigorous specific risk assessment will have to be carried out with several GM lines. Nutritional/toxicological testing on laboratory animals should follow the clinical, double-blind, placebo-type tests with human volunteers.

Allergenicity studies

When the gene is from a crop of known allergenicity, it is easy to establish whether the GM food is allergenic using in vitro tests, such as RAST or immunoblotting, with sera from individuals sensitised to the original crop. This was demonstrated in GM soybeans expressing the brasil nut 2S proteins (Nordlee et al. 1996 ) or in GM potatoes expressing cod protein genes (Noteborn et al. 1995 ). It is also relatively easy to assess whether genetic engineering affected the potency of endogenous allergens (Burks and Fuchs 1995 ). Farm workers exposed to B. thuringiensis pesticide were shown to have developed skin sensitization and IgE antibodies to the Bt spore extract. With their sera it may now therefore be possible to test for the allergenic potential of GM crops expressing Bt toxin (Bernstein et al. 1999 ). It is all the more important because Bt toxin Cry1Ac has been shown to be a potent oral/nasal antigen and adjuvant (Vazquez-Padron et al. 2000 ).

The decision-tree type of indirect approach based on factors such as size and stability of the transgenically expressed protein (O’Neil et al. 1998 ) is even more unsound, particularly as its stability to gut proteolysis is assessed by an in vitro (simulated) testing (Metcalf et al. 1996 ) instead of in vivo (human/animal) testing and this is fundamentally wrong. The concept that most allergens are abundant proteins may be misleading because, for example, Gad c 1, the major allergen in codfish, is not a predominant protein (Vazquez-Padron et al. 2000 ). However, when the gene responsible for the allergenicity is known, such as the gene of the alpha-amylase/trypsin inhibitors/allergens in rice, cloning and sequencing opens the way for reducing their level by antisense RNA strategy (Nakamura and Matsuda 1996 ).

It is known that the main concerns about adverse effects of GM foods on health are the transfer of antibiotic resistance, toxicity and allergenicity. There are two issues from an allergic standpoint. These are the transfer of a known allergen that may occur from a crop into a non-allergenic target crop and the creation of a neo-allergen where de novo sensitisation occurs in the population. Patients allergic to Brazil nuts and not to soy bean then showed an IgE mediated response towards GM soy bean. Lack ( 2002 ) argued that it is possible to prevent such occurrences by doing IgE-binding studies and taking into account physico-chemical characteristics of proteins and referring to known allergen databases. The second possible scenario of de novo sensitisation does not easily lend itself to risk assessment. He reports that evidence that the technology used for the production of GM foods poses an allergic threat per se is lacking very much compared to other methodologies widely accepted in the food industry.

Risks and controversy

There are controversies around GM food on several levels, including whether food produced with it is safe, whether it should be labelled and if so how, whether agricultural biotechnology and it is needed to address world hunger now or in the future, and more specifically with respect to intellectual property and market dynamics, environmental effects of GM crops and GM crops’ role in industrial agricultural more generally.

Many problems, viz. the risks of “tampering with Mother Nature”, the health concerns that consumers should be aware of and the benefits of recombinant technology, also arise with pest-resistant and herbicide-resistant plants. The evolution of resistant pests and weeds termed superbugs and super weeds is another problem. Resistance can evolve whenever selective pressure is strong enough. If these cultivars are planted on a commercial scale, there will be strong selective pressure in that habitat, which could cause the evolution of resistant insects in a few years and nullify the effects of the transgenic. Likewise, if spraying of herbicides becomes more regular due to new cultivars, surrounding weeds could develop a resistance to the herbicide tolerant by the crop. This would cause an increase in herbicide dose or change in herbicide, as well as an increase in the amount and types of herbicides on crop plants. Ironically, chemical companies that sell weed killers are a driving force behind this research (Steinbrecher 1996 ).

Another issue is the uncertainty in whether the pest-resistant characteristic of these crops can escape to their weedy relatives causing resistant and increased weeds (Louda 1999 ). It is also possible that if insect-resistant plants cause increased death in one particular pest, it may decrease competition and invite minor pests to become a major problem. In addition, it could cause the pest population to shift to another plant population that was once unthreatened. These effects can branch out much further. A study of Bt crops showed that “beneficial insects, so named because they prey on crop pests, were also exposed to harmful quantities of Bt.” It was stated that it is possible for the effects to reach further up the food web to effect plants and animals consumed by humans (Brian 1999 ). Also, from a toxicological standpoint, further investigation is required to determine if residues from herbicide or pest resistant plants could harm key groups of organisms found in surrounding soil, such as bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and other microorganisms (Allison and Palma 1997 ).

The potential risks accompanied by disease resistant plants deal mostly with viral resistance. It is possible that viral resistance can lead to the formation of new viruses and therefore new diseases. It has been reported that naturally occurring viruses can recombine with viral fragments that are introduced to create transgenic plants, forming new viruses. Additionally, there can be many variations of this newly formed virus (Steinbrecher 1996 ).

Health risks associated with GM foods are concerned with toxins, allergens, or genetic hazards. The mechanisms of food hazards fall into three main categories (Conner and Jacobs 1999 ). They are inserted genes and their expression products, secondary and pleiotropic effects of gene expression and the insertional mutagenesis resulting from gene integration. With regards to the first category, it is not the transferred gene itself that would pose a health risk. It should be the expression of the gene and the affects of the gene product that are considered. New proteins can be synthesized that can produce unpredictable allergenic effects. For example, bean plants that were genetically modified to increase cysteine and methionine content were discarded after the discovery that the expressed protein of the transgene was highly allergenic (Butler and Reichhardt 1999 ). Due attention should be taken for foods engineered with genes from foods that commonly cause allergies, such as milk, eggs, nuts, wheat, legumes, fish, molluscs and crustacean (Maryanski 1997 ). However, since the products of the transgenic are usually previously identified, the amount and effects of the product can be assessed before public consumption. Also, any potential risk, immunological, allergenic, toxic or genetically hazardous, could be recognized and evaluated if health concerns arise. The available allergen data bases with details are shown in Table 1 .

Allergen databases (Kleter and Peijnenburg 2002 )

| Name | Website | Type of allergen | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| AgMoBiol | Food, Pollen | The Agricultural Molecular Biology Laboratory of the Peking University Protein Engg. & Plant Genetic Engg. | |

| Central Science Lab | Proteins | Food and Drug Administration Centre for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Sand Hutton, York, UK | |

| FARRP | Proteins | 658 allergens, The Food Allergy Research & Resource Program, University of Nebraska-Lincoln | |

| NCFST | Gluten | National Centre for Safety & Technology, Illinois Institute of Technology | |

| PROTALL | Plant | Biochemical and clinical data- The PROTALL project, FAIR- CT98-4356, The Institute of Food Research, UK | |

| SDAP | Proteins | Allergenic Proteins (Ivanciuc et al. ) | |

| SwissPort | Proteins | SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva) | |

| WHO/International Union of Immunological Societies | Proteins | Nomenclature (Chapman ) | |

| Allergome | Proteins | Mari and Riccioli ( ) | |

| Internet Symposium on Food Allergens-2002 | – | Food Allergen data collections |

More concern comes with secondary and pleiotropic effects. For example, many transgenes encode an enzyme that alters biochemical pathways. This could cause an increase or decrease in certain biochemicals. Also, the presence of a new enzyme could cause depletion in the enzymatic substrate and subsequent build up of the enzymatic product. In addition, newly expressed enzymes may cause metabolites to diverge from one secondary metabolic pathway to another (Conner and Jacobs 1999 ). These changes in metabolism can lead to an increase in toxin concentrations. Assessing toxins is a more difficult task due to limitations of animal models. Animals have high variation between experimental groups and it is challenging to attain relevant doses of transgenic foods in animals that would provide results comparable to humans (Butler and Reichhardt 1999 ). Consequently, biochemical and regulatory pathways in plants are poorly understood.

Insertional mutagenesis can disrupt or change the expression of existing genes in a host plant. Random insertion can cause inactivation of endogenous genes, producing mutant plants. Moreover, fusion proteins can be made from plant DNA and inserted DNA. Many of these genes create nonsense products or are eliminated in crop selection due to incorrect appearance. However, of most concern is the activation or up regulation of silent or low expressed genes. This is due to the fact that it is possible to activate “genes that encode enzymes in biochemical pathways toward the production of toxic secondary compounds” (Conner and Jacobs 1999 ). This becomes a greater issue when the new protein or toxic compound is expressed in the edible portion of the plant, so that the food is no longer substantially equal to its traditional counterpart.

There is a great deal of unknowns when it comes to the risks of GM foods. One critic declared “foreign proteins that have never been in the human food chain will soon be consumed in large amounts”. It took us many years to realize that DDT might have oestrogenic activities and affect humans, “but we are now being asked to believe that everything is OK with GM foods because we haven’t seen any dead bodies yet” (Butler and Reichhardt 1999 ). As a result of the growing public concerns over GM foods, national governments have been working to regulate production and trade of GM foods.

Reports say that GM crops are grown over 160 million hectares in 29 countries, and imported by countries (including European ones) that don’t grow them. Nearly 300 million Americans, 1350 million Chinese, 280 million Brazilians and millions elsewhere regularly eat GM foods, directly and indirectly. Though Europeans voice major fears about GM foods, they permit GM maize cultivation. It imports GM soy meal and maize as animal feed. Millions of Europeans visit the US and South America and eat GM food.

Around three million Indians have become US citizens, and millions more go to the US for tourism and business and they will be eating GM foods in the USA. Indian activists claim that GM foods are inherently dangerous and must not be cultivated in India. Activists strongly opposed Bt cotton in India, and published reports claiming that the crop had failed in the field. At the same time farmers soon learned from experience that Bt cotton was very profitable, and 30 million rushed to adopt it. In consequence, India’s cotton production doubled and exports zoomed, even while using much less pesticide. Punjab farmers lease land at Rs 30,000 per acre to grow Bt cotton.

Public concerns-global scenario

In the late 1980s, there was a major controversy associated with GM foods even when the GMOs were not in the market. But the industrial applications of gene technology were developed to the production and marketing status. After words, the European Commission harmonized the national regulations across Europe. Concerns from the community side on GMOs in particular about its authorization have taken place since 1990s and the regulatory frame work on the marketing aspects underwent refining. Issues specifically on the use of GMOs for human consumption were introduced in 1997, in the Regulation on Novel Foods Ingredients (258/97/EC of 27 January 1997). This Regulations deals with rules for authorization and labelling of novel foods including food products made from GMOs, recognizing for the first time the consumer’s right to information and labelling as a tool for making an informed choice. The labelling of GM maize varieties and GM soy varieties that did not fall under this Regulation are covered by Regulation (EC 1139/98). Further legislative initiatives concern the traceability and labelling of GMOs and the authorization of GMOs in food and feed.

The initial outcome of the implementation of the first European directive seemed to be a settlement of the conflicts over technologies related to gene applications. By 1996, the second international level controversy over gene technology came up and triggered the arrival of GM soybeans at European harbours (Lassen et al. 2002 ). The GM soy beans by Monsanto to resist the herbicide represented the first large scale marketing of GM foods in Europe. Events such as commercialisation of GM maize and other GM modified commodities focused the public attention on the emerging biosciences, as did other gene technology applications such as animal and human cloning. The public debate on the issues associated with the GM foods resulted in the formation of many non-governmental organizations with explicit interest. At the same time there is a great demand for public participation in the issues about regulation and scientific strategy who expresses acceptance or rejection of GM products through purchase decisions or consumer boycotts (Frewer and Salter 2002 ).