- Philippines

What the Philippines Tells Us About the Broken Promises of Human Rights

A fter winning the presidency in the Philippines in 2016, Rodrigo Duterte has pursued a relentless “ war on drugs ,” employing police forces in a brutal campaign that has often run roughshod over constitutional guarantees of presumption of innocence and other legal due processes. This “war” has resulted in tens of thousands of casualties from deadly police operations or extra-judicial killings, with no end in sight. To date, no person has been held to account for any abuse of authority or human rights violations in these deaths. Impunity—a reality in my country even before Duterte—has reached unprecedented levels.

Later this year, the world will commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Passed by the U.N. General Assembly in 1948, it was heralded then as a standard by which all nations would abide, to serve as a shield against the horrific atrocities that marked two previous world wars. Since its creation, the world has painstakingly constructed an entire edifice of human rights norms, establishing domestic and international protection mechanisms to ensure the fulfillment of the UDHR’s promise. But that promise has been broken around the world.

In 2014, Eric Posner, American law professor at the University of Chicago, wrote “ The Case Against Human Rights ,” an essay critically examining how human rights had fared across the globe, and exposing the great chasm that exists between rhetoric and reality in how states behave. Four years later, Posner’s prophetic warnings still weigh heavily upon countries where human rights are existentially challenged. A recent TIME cover story “ The Rise of the Strongman ” indicated just some of the countries where this is the case, including Russia, Turkey, Hungary and the Philippines.

The appeal of the strongman is not new and has enticed adherents throughout history. Their proposition has always been simple and strangely effective. They pose a false choice, presenting—in a complex society of competing interests—an alternative of greater safety, security, and stability, in exchange for diminished freedoms. This false and even dystopian dichotomy has regained some currency by feeding upon growing public frustration with governments’ inability to make democracy work for all. And that is how strongmen—perceived to be decisive, armed with populist rhetoric in a “post-truth” world, and ready to cut democratic corners—rise to power.

In his book The Future of Freedom , Fareed Zakaria warned of the prospect of illiberal democracy—where populist leaders take advantage of growing public discontent and win elections. Over time they then dismantle—often with popular consent—whatever constitutional guarantees there might be to rights and freedoms, thereby diminishing democratic accountability.

In the Philippines, Duterte’s continued calls to ignore international outrage led the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, to declare, “I am concerned by deepening repression and increasing threats to individuals and groups with independent or dissenting views.” The recent International Criminal Court decision to open a preliminary examination into the Philippine death toll has prompted the embarrassing response from the Philippine government of withdrawing from the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). Duterte has also threatened ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda with arrest, should she pursue activities in the country.

Without a doubt, democracy and human rights are in retreat today, and not only in the Philippines, but across all continents. What can be done to arrest this current period of democratic recession?

We can and we must direct a righteous rage toward this trend, in a manner that is both purposive and strategic. The road ahead will be difficult, but we must persevere, building solidarity to affirm a politics of civility and inclusion, while employing non-violent strategies in our parliaments, our courts, our cyberspaces, and our streets. Let us be emboldened by an unrelenting will to stand up for justice, and an undying faith in humanity’s capacity for good. If we do not struggle, we will not overcome. We must push back.

We need more democracy and not less of it, and we must uphold human rights for there is no battle more important today. Democracy and human rights are important enablers of human development that will create conditions for people to reach their full potential. As long as persons in any part of the world remain deprived of their fundamental rights and freedom, we are all diminished.

If we are unable to ensure the respect, protection, and fulfillment of human rights and fundamental freedoms of all—especially the poorest and the most marginalized—then the universal human rights project will indeed mean nothing.

Gascon is a speaker at the Oslo Freedom Forum 2018.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Your Vote Is Safe

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- The Surprising Health Benefits of Pain

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at [email protected]

Newsletter Sign Up

Email Address

Your browser is outdated, it may not render this page properly, please upgrade .

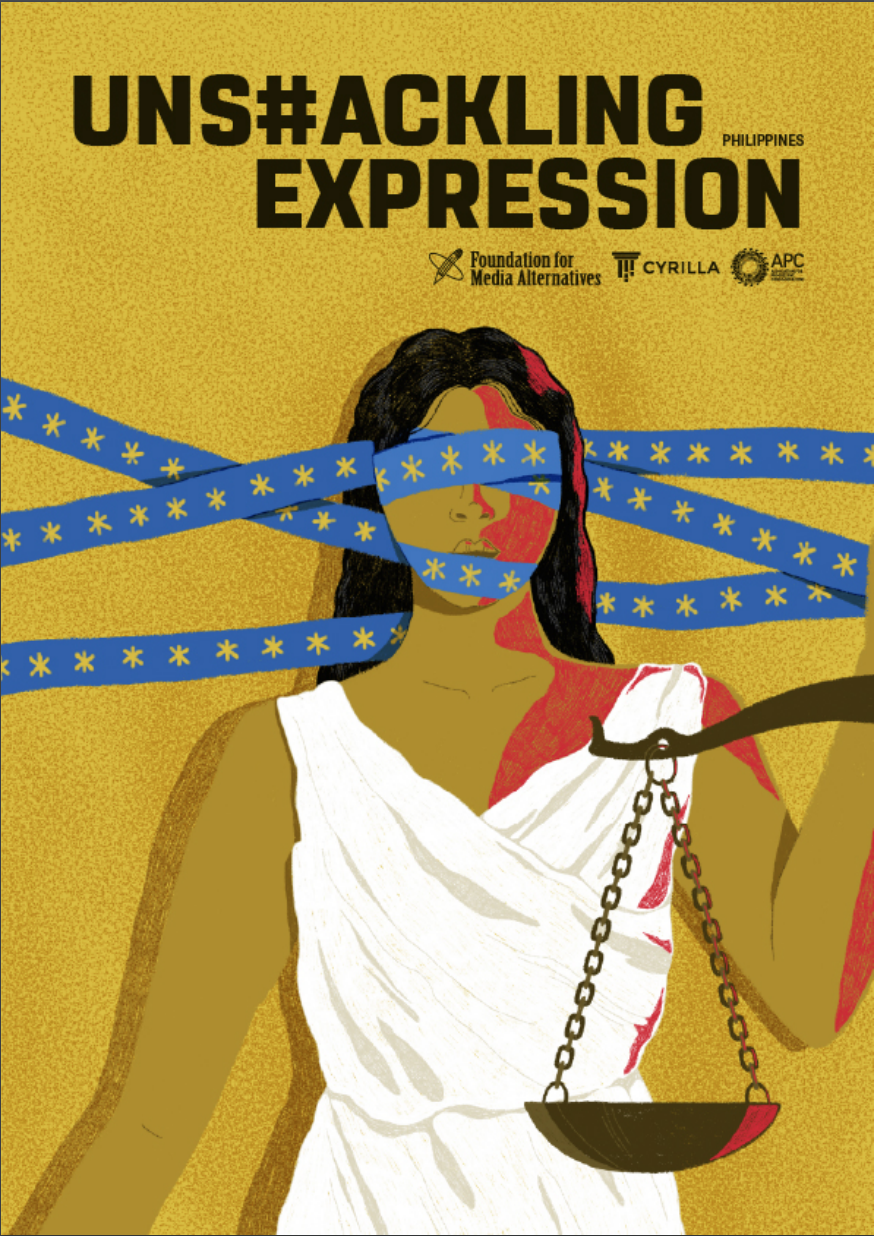

Unshackling Expression: The Philippines Report

October 10, 2020

- Key details

Key Details

The Philippines spends more time in social media than any other country. In the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, it even reported the greatest increase globally of users spending more time in social media. This does not mean that the state of its freedom of expression online is at its healthiest. Various governmental restrictions, limitations, attacks, and even abuses of this freedom exist, keeping the Philippines consistently near the top of “most dangerous countries for journalists” lists. (It’s the fifth worldwide.) The Philippines is only partly free on the 2019 Freedom on the Net Report and dropped three notches from last year.

Globally, social media, which was once thought to level the playing field on civil discussion, now “tilts dangerously toward illiberalism, exposing citizens to an unprecedented crackdown on their fundamental freedoms.” Commenting on attacks from online ‘trolls,’ a former Philippine senator expressed that “we used to say the internet was a marketplace of ideas, [but] now it’s a battlefield.”

In the Philippines, social media is where freedom of expression is usually realized. It is also a crime scene, scoured by law personnel for evidence of utterances which they may find illegal, but may also be valid expressions of discontent and dissent. Considering the current political climate—one dominated by a president often described as ‘authoritarian’ and ‘dictatorial’ and a police and military force that takes his word as law— the line blurs and one is usually mistaken for the other. A pandemic of ‘fake news’—i.e., disinformation, misinformation, and false information—also muddle the waters by which Filipinos navigate their sources of information. As of date, Congress has found a way to criminalize “perpetration” and “spreading” of fake news, which does not bode well for a citizenry that desperately needs digital literacy, in light of a collective susceptibility to believe, on face value, whatever they see online.

Freedom of expression thus grapples not only with restrictions or limitations to speech; in the age of social media and increased internet access, it also forces us to rethink the context and environment that enables and assures its meaningful realization, as will be discussed below.

Read the full report here or below.

Download Publication

Young Writers

The gift of independence, jayce festin, metro manila, philippines first published january 1, 1999, a privilege, a responsibility.

Our independence is a gift to us from our ancestors. Unlike other gifts, the price they paid for it was eternal. People such as José Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Aguinaldo gave their all in a white flame of sacrifice on the altar of their nation. They lived, suffered and died for their noble cause, knowing they might never see the next sunrise. Still, they fought on.

Andres Bonifacio said: “In the fury of your struggle, some of you might die in the midst of battle, but this is an honor that will be a legacy to our race and our progeny.” Together with Jose Rizal and countless others, their words of inspiration fill our minds and hearts like blood clots of revelation from the wounds of humanity. They, like many others, answered the call of our native land—the call of freedom.

We should look back on the glories of the past with profound pride, remembering the sacrifices as we till the fields that have soaked up blood from countless battles, as we idly cruise through cities that stood witnesses to the marks of history and as we look upon the faces of our fellowmen, knowing that it is for them they fought. Lives were lost all throughout the dark moments of history and yet these moments are the ones that have further strengthened our patriotic love for our motherland.

Our independence is tempered by a responsibility. This responsibility calls for all of us to work hand in hand to make sure that the efforts of the heroes behind our liberation will not have been in vain.

Because of our freedom, we are now of a mind to make our own personality as Filipinos. We shoulder the responsibility of creating our own history to add to the golden pages of time.

Some say that the age of heroism is past. But if we observe closely, we will notice that at one time or another, someone, somewhere is bringing new meaning to the name Filipino . We will all stand firm, fighting for God and country. After all, for what greater or nobler cause is there than to fight than the ashes of our fathers and the temples of our gods? An age without a name is equal to one hour of sweet liberty.

The Philippines is no longer an obscure blot on the map. We have passed the test of time as the Centennial Celebration has doubtless proven. The Philippines is enjoying a century of independence, but we must also move out of the past and into the hands of the new generation.

Our country is a work in progress. As citizens of this country, we must do all we can to help. The people are the nation and it is up to us to keep the torch of freedom burning.

(This an inspirational essay for teenagers in the Philippines, my country)

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Philippines has a republic government demonstrated with the freedom gained from determination and bravery. The history of the country told its dark past from the hands of …

In his book The Future of Freedom, Fareed Zakaria warned of the prospect of illiberal democracy—where populist leaders take advantage of growing public discontent and win elections.

In 2020, the Philippines presented a comprehensive account of human rights policies, mechanisms, advocacies and accomplishments, reflecting the Philippine …

The Nobel Peace Prize awarded to journalists Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov has highlighted the state of press freedom in the Philippines and Russia, with the Philippines being considered one of the most dangerous …

Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of …

Hard-won after centuries of colonization, years of occupation and decades of dictatorship, Philippine-style democracy is colourful, occasionally chaotic – and arguably inspiring. Take elections, for example, the cornerstone …

In the Philippines, social media is where freedom of expression is usually realized. It is also a crime scene, scoured by law personnel for evidence of utterances which they may find illegal, but may also be valid expressions of …

Our independence is tempered by a responsibility. This responsibility calls for all of us to work hand in hand to make sure that the efforts of the heroes behind our liberation will …