- One email, all the Golden State news

- Get the news that matters to all Californians. Start every week informed.

- Newsletters

- Environment

- 2024 Voter Guide

- Digital Democracy

- Daily Newsletter

- Data & Trackers

- California Divide

- CalMatters for Learning

- College Journalism Network

- What’s Working

- Youth Journalism

- Manage donation

- News and Awards

- Sponsorship

- Inside the Newsroom

- CalMatters en Español

Will less homework stress make California students happier?

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

A bill from a member of the Legislature’s happiness committee would require schools to come up with homework policies that consider the mental and physical strain on students.

Lea esta historia en Español

Update: The Assembly education committee on April 24 approved an amended version of the bill that softens some requirements and gives districts until the 2027-28 school year. The full Assembly passed the bill on May 21. Some bills before California’s Legislature don’t come from passionate policy advocates, or from powerful interest groups.

Sometimes, the inspiration comes from a family car ride.

While campaigning two years ago, Assemblymember Pilar Schiavo ’s daughter, then nine, asked from the backseat what her mother could do if she won.

Schiavo answered that she’d be able to make laws. Then, her daughter Sofia asked her if she could make a law banning homework.

“It was a kind of a joke,” the Santa Clarita Valley Democrat said in an interview, “though I’m sure she’d be happy if homework were banned.”

Still, the conversation got Schiavo thinking, she said. And while Assembly Bill 2999 — which faces its first big test on Wednesday — is far from a ban on homework, it would require school districts, county offices of education and charter schools to develop guidelines for K-12 students and would urge schools to be more intentional about “good,” or meaningful homework.

Among other things, the guidelines should consider students’ physical health, how long assignments take and how effective they are. But the bill’s main concern is mental health and when homework adds stress to students’ daily lives.

Homework’s impact on happiness is partly why Schiavo brought up the proposal last month during the first meeting of the Legislature’s select committee on happiness , led by former Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon .

“This feeling of loneliness and disconnection — I know when my kid is not feeling connected,” Schiavo, a member of the happiness committee, told CalMatters. “It’s when she’s alone in her room (doing homework), not playing with her cousin, not having dinner with her family.”

The bill analysis cites a survey of 15,000 California high schoolers from Challenge Success, a nonprofit affiliated with the Stanford Graduate School of Education. It found that 45% said homework was a major source of stress and that 52% considered most assignments to be busywork.

The organization also reported in 2020 that students with higher workloads reported “symptoms of exhaustion and lower rates of sleep,” but that spending more time on homework did not necessarily lead to higher test scores.

Homework’s potential to also widen inequities is why Casey Cuny supports the measure. An English and mythology teacher at Valencia High School and 2024’s California Teacher of the Year , Cuny says language barriers, unreliable home internet, family responsibilities or other outside factors may contribute to a student falling behind on homework.

“I never want a kid’s grade to be low because they have divorced parents and their book was at their dad’s house when they were spending the weekend at mom’s house,” said Cuny, who plans to attend a press conference Wednesday to promote the bill.

In addition, as technology makes it easier for students to cheat — using artificial technology or chat threads to lift answers, for example — Schiavo says that the educators she has spoken to indicate they’re moving towards more in-class assignments.

Cuny agrees that an emphasis on classwork does help to rein in cheating and allows him to give students immediate feedback. “I feel that I should teach them what I need to teach them when I’m with them in the room,” he said.

The bill says the local homework policies should have input from teachers, parents, school counselors, social workers and students; be distributed at the beginning of every school year; and be reevaluated every five years.

The Assembly Committee on Education is expected to hear the bill Wednesday. Schiavo says she has received bipartisan support and so far, no official opposition or support is listed in the bill analysis.

The measure’s provision for parental input may lead to disagreements given the recent culture war disputes between Democratic officials and parental rights groups backed by some Republican lawmakers. Because homework is such a big issue, “I’m sure there will be lively (school) board meetings,” Schiavo said.

Nevertheless, she says she hopes the proposal will overhaul the discussion around homework and mental health. The bill is especially pertinent now that the state is also poised to cut spending on mental health services for children with the passage of Proposition 1 .

Schiavo said the mother of a student with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder told her that the child’s struggle to finish homework has raised issues inside the house, as well as with the school’s principal and teachers.

“And I’m just like, it’s sixth grade!” Schaivo said. “What’s going on?”

Lawmakers want to help California be happy

We want to hear from you

Want to submit a guest commentary or reaction to an article we wrote? You can find our submission guidelines here . Please contact CalMatters with any commentary questions: [email protected]

Lynn La Newsletter Writer

Lynn La is the newsletter writer for CalMatters, focusing on California’s top political, policy and Capitol stories every weekday. She produces and curates WhatMatters, CalMatters’ flagship daily newsletter... More by Lynn La

Too much homework? New CA bill aims to ease the load on students

Having less homework would be beneficial for some students like Kyan Vanderweel, a San Luis Obispo high school student.

With multiple band and orchestra practices a day, on top of taking AP classes, Vanderweel finds it difficult to balance the things he loves to do with what he needs to get done, saying it even affects his mental health.

“AP classes should have homework but only a limited amount but in my opinion, I don’t think English classes apart from reading should have any unnecessary homework,” Vanderweel said.

Vanderweel says his homework and classwork are very repetitive and he feels it's unnecessary to do some of the homework.

“By the end of the day, we already know what we're doing so I feel like it’s a waste of time to an extent,” Vanderweel said.

Other students feel like homework in high school is bearable.

“I think I'm pretty comfortable with how it is right now,” San Luis Obispo High School student Tamiyah Murrieta said.

The "Healthy Homework Act,” introduced by Assemblywoman Pilar Schiavo, would not ban homework altogether but would require local school boards and educational agencies to establish policies that consider impacts on students’ physical and mental health with input from parents, teachers and students.

This is something Tyler Gerbel, a San Luis Obispo high school student, says could impact some students.

“Homework has been shown to stress students out a little bit. I’ve felt that myself when I have so much work to do,” Gerbel said.

Although he thinks his workload is manageable right now, he understands how some might have it harder.

“If something is done to limit the homework it might relieve stress off of students and I feel like mental health is a very important thing for students today,” Gerbel said.

The bill is also tailored to people who might not have access to resources at home like high-speed internet.

The bill would require the adopted policy to be updated at least once every five years.

It is currently making its way through the State Legislature.

Sign up for the Headlines Newsletter and receive up to date information.

Now signed up to receive the headlines newsletter..

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

Will Less Homework Stress Make California Students Happier?

Please try again

Some bills before California’s Legislature don’t come from passionate policy advocates or powerful interest groups.

Sometimes, the inspiration comes from a family car ride.

While campaigning two years ago, Assemblymember Pilar Schiavo ’s daughter, then 9, asked from the backseat what her mother could do if she won.

Schiavo answered that she’d be able to make laws. Then, her daughter Sofia asked if she could make a law banning homework.

“It was a kind of a joke,” the Santa Clarita Valley Democrat said in an interview, “though I’m sure she’d be happy if homework were banned.”

Still, the conversation got Schiavo thinking, she said. And while Assembly Bill 2999 — which faces its first big test on Wednesday — is far from a ban on homework, it would require school districts, county offices of education and charter schools to develop guidelines for K–12 students. It would urge schools to be more intentional about “good” or meaningful homework.

Among other things, the guidelines should consider students’ physical health, how long assignments take, and how effective they are. However, the bill’s main concern is mental health and when homework adds stress to students’ daily lives.

Homework’s impact on happiness is partly why Schiavo brought up the proposal last month during the first meeting of the Legislature’s select committee on happiness , led by former Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon .

“This feeling of loneliness and disconnection — I know when my kid is not feeling connected,” Schiavo, a member of the happiness committee, told CalMatters. “It’s when she’s alone in her room (doing homework), not playing with her cousin, not having dinner with her family.”

The bill analysis cites a survey of 15,000 California high schoolers from Challenge Success, a nonprofit affiliated with the Stanford Graduate School of Education. It found that 45% said homework was a major source of stress and that 52% considered most assignments to be busywork.

The organization also reported in 2020 that students with higher workloads reported “symptoms of exhaustion and lower rates of sleep” but that spending more time on homework did not necessarily lead to higher test scores.

Homework’s potential to also widen inequities is why Casey Cuny supports the measure. Cuny, an English and mythology teacher at Valencia High School and 2024’s California Teacher of the Year , said language barriers, unreliable home internet, family responsibilities or other outside factors may contribute to a student falling behind on homework.

“I never want a kid’s grade to be low because they have divorced parents, and their book was at their dad’s house when they were spending the weekend at mom’s house,” said Cuny, who plans to attend a press conference Wednesday to promote the bill.

In addition, as technology makes it easier for students to cheat — using artificial technology or chat threads to lift answers, for example — Schiavo said that the educators she has spoken to indicate they’re moving towards more in-class assignments.

Cuny agrees that an emphasis on classwork does help to rein in cheating and allows him to give students immediate feedback. “I feel that I should teach them what I need to teach them when I’m with them in the room,” he said.

The bill said the local homework policies should have input from teachers, parents, school counselors, social workers and students; be distributed at the beginning of every school year; and be reevaluated every five years.

The Assembly Committee on Education is expected to hear the bill Wednesday. Schiavo said she has received bipartisan support, and so far, no official opposition or support has been listed in the bill analysis.

But she acknowledges that, if passed, the measure’s provision for parental input may lead to disagreements given the recent culture war disputes between Democratic officials and parental rights groups backed by some Republican lawmakers. “I’m sure there will be lively (school) board meetings,” Schiavo said.

Nevertheless, she hopes the proposal will overhaul the discussion around homework and mental health. The bill is especially pertinent now that the state is also poised to cut spending on mental health services for children with the passage of Proposition 1 .

Schiavo said the mother of a student with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder told her that the child’s struggle to finish homework had raised issues inside the house, as well as with the school’s principal and teachers.

“And I’m just like, it’s sixth grade!” Schaivo said. “What’s going on?”

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.

For the first time, California law will protect students’ right to recess

This is Part Two of a two-part series. Read Part One here.

A new California law is set to protect young students’ right to recess for the first time in state history.

That law, Senate Bill 291 , defines what “recess” really means: free, unstructured time to play and socialize. It also requires that elementary students receive at least 30 minutes every day and makes it illegal for educators to take that time away as punishment.

The law will go into effect next school year. But San Diego Unified and other local districts were not yet ready to talk about their plans to meet these requirements.

These changes come at a critical time for young Californians. The way kids play has quietly transformed over the years, with full schedules of activities replacing the freewheeling lives of older generations. And experts worry about the repercussions on kids’ mental health.

School, and recess in particular, has remained one of the few places where kids still have access to free, unstructured time. Every day, blacktops and playgrounds across the country transform into places where kids invent games and bicker and learn to find resolutions.

But recess has slowly been gnawed away. Over the last 20 years, schools nationwide have been quietly cutting back on recess times in favor of more time in the classroom, reducing it by as much as 60 minutes per week, according to one analytics firm .

It’s difficult to say definitively how much recess has changed in San Diego County. Recess times and bell schedules are decided by individual schools, and districts largely said they don’t keep that information from past years.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, many parents and educators have grown increasingly concerned about play and what it means for kids’ mental health. Now, they hope that California’s new law could change the direction for schools in the nation’s largest state.

“I'm really glad that the law is going to come into effect,” said Ana Cordova, whose 3-year-old son could start Transitional Kindergarten next year. “They're just kids — so they have all their lives to not have recess.”

‘A sea change’

Recess, experts say, is more important than some might think. It is often kids’ main source of time to play freely and without structure — something that is crucial to kids’ development of social skills, creativity and long term mental health. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control recommends that elementary students receive at least 20 minutes of recess per day.

“That interaction is an incredibly important part of child development,” said Rebecca London, a professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

But recess has also been under threat for decades, with critics calling it a waste of school time and contrary to the mission of the education system.

Experts say much of that motivation to cut back recess times stems from a Cold War-era push by the federal government to keep pace with other countries by sharpening public schools’ focus on academic performance.

California districts and other schools across the country started cutting recess away in favor of class time, London says. In some cities, like Atlanta, Baltimore and Chicago, officials eliminated it altogether .

“We are intent on improving academic performance. You don’t do that by having kids hanging on monkey bars,” Atlanta superintendent Benjamin Canada told The New York Times in 1998.

In 2001, the No Child Left Behind Act brought new, sweeping changes. Schools with low academic performance now risked losing federal funding, and could even be shut down. It was, London said, “a sea change.”

“It was not, ‘you get bonuses if you do well,’” she said. “It was, ‘you lose financial support if you don't make this progress.’”

Educators were suddenly under tremendous pressure. They responded by focusing on academics, sending students home with more work and lengthening the school year. Since the law went into effect, at least a fifth of U.S. school districts have also cut back recess time .

In California, London and other researchers tracked these changes in poorer schools. London analyzed a sample of low-income schools from a 2020-2021 state survey. Only half said they gave students more than 20 minutes of recess.

Researchers also found that these changes also fell more on Black and Latino students. An analysis of federal data on students from 1998-1999 found that more than 77% of white students had some recess, but just 41% of Black students and 62% of Latino students had access to that time.

“Recess in school has really just filled the void of the kids being able to exercise that sort of free will,” said Dennis Lim, a San Diego parent. “We need to do whatever we can to make sure they get as much time for that.”

New protections in California

In California, the decline of recess was possible in part because the state had no laws regulating recess. Instead, the state law’s approach was to direct the Department of Education to “encourage” elementary schools to provide recess time.

“The law was effectively silent,” said California state Sen. Josh Newman, D-Fullerton, who chairs the state Senate’s Education Committee.

California wasn’t alone. Just nine other states actually mandate that schools offer recess time every day, and most only offer simple recommendations or don’t address it at all. Districts nationwide also collect very little information on recess time .

Then came the pandemic. Across the state, schools closed down, isolating elementary-aged children from each other. When schools reopened over a year later, London said students were at a loss on how to cooperate or solve conflicts.

“One of the things that we heard from elementary school staff when the kids came back that first year was, ‘they don't even know how to interact with each other anymore,’” she said. “That was a year of development that children didn't get.”

For Newman, that was the turning point.

“We probably needed to explore this question about recess anyway,” he said. “But it seemed like it was really imperative to do it now — and hopefully do it right.

Newman sponsored the law adding new protections for California students’ right to recess. It defines recess as supervised, unstructured play time separate from both lunch and more structured physical education courses. It requires schools to offer 30 minutes of recess time every day and bans educators from taking that time away as punishment.

London, who testified in support of SB 291 before the Education Committee last year, is cautious about celebrating too hard. But she is certainly optimistic.

“It’s a huge change,” she said.

Are school districts ready?

Many San Diego-area schools already meet the requirement of at least 30 minutes of recess. But most district officials wouldn’t give interviews on how they intend to ensure schools follow all parts of the law.

KPBS reached out to four different San Diego-area school districts — San Diego Unified, Chula Vista Elementary School District, South Bay Union and National School District — and most declined to give interviews with top district officials or did not respond to a request for comment.

San Diego Unified, the state’s second-largest school district, did not agree to provide an interview in time for publication. A Chula Vista Elementary School District spokesperson said they did not have enough information on the law to answer any questions. National School District did not respond to a request for comment.

Still, many schools in the San Diego region say they do already meet the new minimum requirements for recess time this year, including South Bay Union School District in Imperial Beach.

Officials there said South Bay Union does collect bell schedules from each school, and that the district planned to review them to make sure that all schools were following the requirements of SB 291 for next year.

“Our K-8 daily schedule already includes 30 minutes of recess, so there will be no change next year,” wrote South Bay Union School District spokesperson Amy Cooper, in an email. “We value the importance of recess time in which students have the opportunity to interact with peers.”

Many parents are optimistic about these changes, including Cordova, whose son Nolan could be in Transitional Kindergarten next year. Nolan was born right after the beginning of the pandemic, and Cordova said he still has a hard time playing with other kids.

“Even still in preschool, when they have recess, he tends to keep to his own,” she said. “The teachers tell us it takes him some time to warm up.”

“And I cry,” Nolan added from the couch nearby.

Still, Cordova hopes that recess in elementary school will give Nolan another chance to keep learning those skills.

“We just want him to keep learning how to get along with different personalities and find his own group of friends,” she said.

New Legislation Would Guarantee Daily Recess for All California Students K-8

Sacramento, Calif.— Senator Josh Newman, Chair of the Senate Committee on Education, introduced his first education bill of the year, SB 291, which will ensure all K-8 pupils in California have access to a minimum standard of recess while prohibiting the withholding of recess as a form of punishment or discipline.

A wide body of research has found that recess serves as a critical outlet and break for students to reset their minds and bodies during otherwise structured school days filled with academic demands. Recess offers students numerous cognitive, social, emotional, and physical benefits and results in students being more attentive and better able to perform school tasks.

“As California finally emerges from the pandemic and its impacts, we are seeing some of the lingering effects on children’s social-emotional development play out in the form of behavioral disruptions which have become increasingly prevalent in classrooms,” said Senator Josh Newman (D-Fullerton). “As schools and students seek to recover from COVID-related educational disruptions, the benefits of the unstructured play and peer-to-peer social interactions offered by recess are more important now than ever.”

Despite the research, the denial of all or part of recess still remains a common practice in schools, employed as punishment for infractions such as failing to finish work, talking out of turn or not following directions. Recess detentions also tend to disproportionately impact students from disadvantaged communities, as well as those with disabilities.

"Recess is the only unstructured time in the school day where students have the opportunity to stretch their social, emotional, and physical development through play, socialization with peers, and interactions with adults. It is essential that all California students have the right to this downtime every day, and that it is not withheld for punishment. Recess is an important opportunity for building a positive school climate and for helping all students to go back to their classrooms after recess feeling restored and ready to learn. I applaud Senator Newman for prioritizing Recess for All and fully support these efforts," said Rebecca London, Associate Professor of Sociology and Faculty Director of Campus + Community at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who has been studying recess in California for more than 15 years.

Unlike other states which have adopted standardized school recess policies, such as Florida, Missouri, New Jersey, Rhode Island and Arizona, California currently has no statewide standardized policy governing the quantity and quality of recess time in its schools. In fact, under existing state law, school districts are actually directed to adopt policies authorizing teachers to restrict a student’s recess time for disciplinary purposes. As a consequence, gaps exist across the state’s school systems with respect to access to daily recess, and the presence of these gaps tends to correlate with other equity and performance deficits across California’s educational systems.

"I am so glad to see Senator Newman prioritizing recess in California schools. Evidence from other states shows that when recess is legislated at the state level, schools are more likely to provide students with the minutes. And providing students with the opportunity to, as my 8-year-old son calls it, ‘get the wiggles out,’ is more important now than ever. There are countless documented benefits to school recess, including increased student physical activity; increased social and emotional development; and improved attention, memory, concentration, and on-task behavior in the classroom, said Hannah R. Thompson, Ph.D., MPH, Assistant Research Professor, UC Berkeley School of Public Health.

Under SB 291, elementary and middle schools in California will be required to provide students with a daily recess period of at least 30 minutes, to be held outdoors, weather permitting. Additionally, SB 291 would prohibit a student from being denied recess as a disciplinary measure, unless their participation would pose an immediate threat to the physical safety of others or their own physical safety.

To schedule an interview with Senator Newman, contact Lizzie Cootsona at 916.651.4029.

State Senator Josh Newman represents the 29th Senate District, which is comprised of portions of Los Angeles County, Orange County, and San Bernardino County. The 29th District includes all or parts of the cities of Anaheim, Brea, Buena Park, Chino Hills, City of Industry, Cypress, Diamond Bar, Fullerton, La Habra, La Palma, Placentia, Rowland Heights, Stanton, Walnut, West Covina and Yorba Linda. Senator Newman is a former United States Army officer, businessperson, and veterans’ advocate, and lives in Fullerton with his wife and daughter.

Back To Top

When homework is busywork

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Rachel Bennett, 12, loves playing soccer, spending time with her grandparents and making jewelry with beads. But since she entered a magnet middle school in the fall -- and began receiving two to four hours of homework a night -- those activities have fallen by the wayside.

“She’s only a kid for so long,” said her father, Alex Bennett, of Silverado Canyon. “There’s been tears and frustration and family arguments. Everyone gets burned out and tired.”

Bennett is part of a vocal movement of parents and educators who contend that homework overload is robbing children of needed sleep and playtime, chipping into family dinners and vacations and overly stressing young minds. The objections have been raised for years but increasingly, school districts are listening. They are banning busywork, setting time limits on homework and barring it on weekends and over vacations.

“Groups of parents are going to schools and saying, ‘Get real. We want our kids to have a life,’ ” said Cathy Vatterott, an associate education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, who has studied the issue.

Trustees in Danville, Calif., eliminated homework on weekends and vacations last year. Palo Alto officials banned it over winter break. Officials in Orange, where Rachel Bennett attends school, are reminding teachers about limits on homework and urging them not to assign it on weekends. A private school in Hollywood has done away with book reports.

“As adults, if every book we ever read, we had to write a report on -- would that encourage our reading or discourage it?” asked Eileen Horowitz, head of school at Temple Israel of Hollywood Day School. “We realized we needed to rethink that.”

Nancy Ortenberg is happy about the change.

“Homework is much more meaningful now,” said Ortenberg, whose daughter Isabelle, 9, was in school before the policy took effect in 2007. Before the change, it was a chore for her daughter, but “now she reads for the pure joy of reading.”

Homework was once hugely controversial. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, social commentators and physicians crusaded against it, convinced it was causing children to become wan, weak and nervous.

In a 1900 article titled “A National Crime at the Feet of American Parents” in the Ladies’ Home Journal, editor Edward Bok wrote, “When are parents going to open their eyes to this fearful evil? Are they as blind as bats, that they do not see what is being wrought by this crowning folly of night study?”

California was at the vanguard of the anti-homework movement. In 1901, the California Legislature banned it for students under 15 and ordered high schools to limit it for older students to 20 recitations a week. The law was taken off the books in 1917.

Homework has fallen in and out of favor ever since, often viewed as a force for good when the nation feels threatened -- after the Soviets launched Sputnik in 1957, for example, and during competition with Japan in the 1980s.

The homework wars have reignited in recent years, with parents around the nation arguing that children are being given too much.

Much of the debate is driven by the belief that today’s students are doing more work at home than their predecessors. But student surveys do not bear that out, said Brian Gill, a senior social scientist with Mathematica Policy Research.

Instead, in today’s increasingly competitive race for college admission, student schedules are increasingly packed with clubs, sports and other activities in addition to homework, Gill said. Students -- and parents -- may just have less time, he said.

Not all object, however.

“Obviously we want to think it’s busywork, but most of the time it’s really helpful,” said Allison Hall, 16, a junior at Villa Park High in the Orange district. Allison, who is taking five Advanced Placement classes, has up to three hours of homework a night; she also is on the cross country, track and mock trial teams and does volunteer work.

But others say there is just too much, especially for younger children. Karen Adnams of Villa Park has four children. She said that heavier course loads make sense for older children but that she doesn’t understand the amount of work given in lower grades.

“I think teachers have lost touch with what a third-grader or a fifth-grader can really do,” she said.

Vatterott, a former principal, said she became interested in the subject a decade ago as a frustrated parent. Her son, who has a learning disability, was upset by assignments he didn’t understand and couldn’t complete in a reasonable time.

She decided to study the effectiveness of homework. That research showed that more time spent on such work was not necessarily better.

Vatterott questioned the quantity and the quality of assignments. If 10 math problems could demonstrate a child’s grasp of a concept, why assign 50, she asked? The solution, she said, was not to do away with homework but to clarify the reasons for assigning it.

Some schools, among them Grant Elementary in Glenrock, Wyo., have gone further. Principal Christine Hendricks had grown concerned that students were spending too much time on busywork and that homework was causing conflicts between parents and children and between teachers and students. So she got rid of it last year except for reading and studying for tests.

“My philosophy, even when I was a teacher, is if you work hard during the day, I don’t like to work at night. Kids are kind of the same way,” she said.

Other districts, including San Ramon Valley Unified in Danville, Calif., have taken a more nuanced approach.

Since San Ramon revised its homework policy last year, the youngest students are given no more than 30 minutes a night; high school students have up to three hours of work. District trustees also decided that aside from reading, no homework should be given to elementary and middle school students on weekends or vacations.

In the Orange Unified School District, trustee John Ortega grew concerned about the workload carried by his middle school daughter. “We would have a swim meet all weekend, and she would be worried about coming home and having to finish homework,” he said. “She was stressed about it.”

After speaking with other parents, Ortega raised the subject publicly in the fall, prompting a series of discussions in the district. It turned out that although the board had set limits on homework, they were not always followed, said Marsha Brown, assistant superintendent of educational services. She said teachers have now been informed about the policy and principals are working to clarify the purpose of homework.

Brown said children’s social growth must be nurtured alongside their academic development. “We don’t want just academic children. We want them involved in sports and music and art and family time and downtime,” she said. “We want well-rounded citizens. I think we will always be struggling with that balance.”

Seema Mehta is a veteran political writer who is covering the 2024 presidential race as well as other state and national contests. She started at the Los Angeles Times in 1998, previously covered multiple presidential, state and local races, and completed a Knight-Wallace fellowship at the University of Michigan in 2019.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Round 3: UC takes striking academic workers to Orange County court in bid to halt walkout

LAUSD fined $8 million for staffing violations. Too many students, not enough teachers

June 7, 2024

State Supreme Court gives UC Berkeley go-ahead to develop People’s Park, capping decades-long battle

June 6, 2024

Three Jewish students sue UCLA, saying protesters blocked access to campus facilities

The Surprising History of Homework Reform

Really, kids, there was a time when lots of grownups thought homework was bad for you.

Homework causes a lot of fights. Between parents and kids, sure. But also, as education scholar Brian Gill and historian Steven Schlossman write, among U.S. educators. For more than a century, they’ve been debating how, and whether, kids should do schoolwork at home .

At the dawn of the twentieth century, homework meant memorizing lists of facts which could then be recited to the teacher the next day. The rising progressive education movement despised that approach. These educators advocated classrooms free from recitation. Instead, they wanted students to learn by doing. To most, homework had no place in this sort of system.

Through the middle of the century, Gill and Schlossman write, this seemed like common sense to most progressives. And they got their way in many schools—at least at the elementary level. Many districts abolished homework for K–6 classes, and almost all of them eliminated it for students below fourth grade.

By the 1950s, many educators roundly condemned drills, like practicing spelling words and arithmetic problems. In 1963, Helen Heffernan, chief of California’s Bureau of Elementary Education, definitively stated that “No teacher aware of recent theories could advocate such meaningless homework assignments as pages of repetitive computation in arithmetic. Such an assignment not only kills time but kills the child’s creative urge to intellectual activity.”

But, the authors note, not all reformers wanted to eliminate homework entirely. Some educators reconfigured the concept, suggesting supplemental reading or having students do projects based in their own interests. One teacher proposed “homework” consisting of after-school “field trips to the woods, factories, museums, libraries, art galleries.” In 1937, Carleton Washburne, an influential educator who was the superintendent of the Winnetka, Illinois, schools, proposed a homework regimen of “cooking and sewing…meal planning…budgeting, home repairs, interior decorating, and family relationships.”

Another reformer explained that “at first homework had as its purpose one thing—to prepare the next day’s lessons. Its purpose now is to prepare the children for fuller living through a new type of creative and recreational homework.”

That idea didn’t necessarily appeal to all educators. But moderation in the use of traditional homework became the norm.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

“Virtually all commentators on homework in the postwar years would have agreed with the sentiment expressed in the NEA Journal in 1952 that ‘it would be absurd to demand homework in the first grade or to denounce it as useless in the eighth grade and in high school,’” Gill and Schlossman write.

That remained more or less true until 1983, when publication of the landmark government report A Nation at Risk helped jump-start a conservative “back to basics” agenda, including an emphasis on drill-style homework. In the decades since, continuing “reforms” like high-stakes testing, the No Child Left Behind Act, and the Common Core standards have kept pressure on schools. Which is why twenty-first-century first graders get spelling words and pages of arithmetic.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

Wild Saints and Holy Fools

Building Classroom Discussions around JSTOR Daily Syllabi

Scaffolding a Research Project with JSTOR

Making Implicit Racism

Recent posts.

- Aurorae and the Green of the Night Sky

- Heritage Bilinguals and the Second-Language Classroom

- IceCube Detector Confirms Deep-Space “Ghost Particle” Phenomenon

- The Uneven Costs of Cross-Country Connectivity

- How Two Rebel Physicists Changed Quantum Theory

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

CA bills on homework, outdoor drinking and more stay alive

Stay up-to-date with free briefings on topics that matter to all Californians. Subscribe to CalMatters today for nonprofit news in your inbox.

Scheduling note: WhatMatters is taking Memorial Day off and will return to your inboxes on Tuesday.

California lawmakers started this week with more than 900 bills to wade through before today’s deadline for measures to pass their first house. They’re nearly done , advancing the vast majority of bills.

I wanted to catch up on some that caught my eye and wrote about earlier this legislative session:

- Homework: The Assembly passed a bill Tuesday to require schools to adopt homework policies that consider students’ stress levels and well being . The proposal was inspired by Assemblymember Pilar Schiavo ’s daughter, and was brought up by the Santa Clarita Valley Democrat during a hearing of the Legislature’s select committee on happiness .

- Daylight saving time: On Thursday, the Senate advanced a proposal originally intended to set standard time year-round and do away with daylight saving time permanently . The bill has been amended to require the state to study the near- and long-term effects of permanent standard time (particularly on energy demands) and submit it to the Legislature by 2027.

- Alcohol outdoors: California cities and counties are one step closer to being able to designate “ entertainment zones .” The Senate passed a proposal Thursday that would allow bars and restaurants to serve alcoholic drinks that people can consume on public streets and sidewalks .

- Teen treatment centers: Also Thursday, a measure to bring greater transparency to the treatment of young adults living in state-run facilities heads to the Assembly after passing the Senate. The bill, backed by media personality Paris Hilton , would expand reporting requirements for these residential therapeutic programs, specifically their use of “seclusion rooms” and restraints.

- U.S. Semiquincentennial: And today the Senate is expected to vote on a bill to establish a commission to help California commemorate the 250th anniversary of the United States’ founding in 2026.

Other bills of note:

- Abortion access: On Thursday, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law the bill passed this week to allow Arizona doctors to temporarily provide abortions to women traveling to California while a ban is in place in their state.

- Voter identification: About a month after the state filed a lawsuit against Huntington Beach over its voter ID mandate, the Senate passed a bill to bar local governments from implementing voter ID requirements . All Republican senators voted against the bill.

- No-pet rental policies: The Assembly passed a bill that would restrict landlords from banning pets from rental properties “without reasonable justification.” Because of amendments made to the bill, landlords could still limit the number of pets and require a deposit to pay for pet-cleaning expenses.

Elsewhere in the Legislature: This week, leaders of the European Union concluded a years-long initiative by passing the Artificial Intelligence Act , regulating its use in 27 nations. But it’s Europe’s close partnership with California that may also help the state emerge as the U.S.’ leader in AI regulation .

As CalMatters tech reporter Khari Johnson explains, because of California’s unique position as a tech-forward state, it must walk a tightrope. The state must craft legislation that prevents harms caused by the technology — such as bills passed this week to oversee the use of generative AI and stop discrimination against marginalized groups — without stifling a significant and growing industry.

- Sen. Tom Umberg , a Santa Ana Democrat and chairperson of the Senate Judiciary Committee: “I strongly believe that we can learn from each other’s work and responsibly regulate AI without harming innovation in this dynamic and quickly-changing environment.”

Find out more in Khari’s story .

CalMatters on TV: This week, we launched a partnership with PBS SoCal for two-minute video stories each weekday. SoCalMatters will air at 5:58 p.m. on PBS SoCal and also be available online at PBS SoCal and CalMatters , plus on KQED’s “California Newsroom.” Reporters will work with producer Robert Meeks on the segments, which will focus on a wide range of topics. The one that aired Thursday focused on financial aid fraud at community colleges , based on this CalMatters story . Read more about this new venture from our engagement team.

Focus on inequality: Each Friday, the California Divide team delivers a newsletter that focuses on the politics and policy of inequality. Read an edition here and subscribe here .

Other Stories You Should Know

Breaking up ticketmaster.

For their stranglehold on the ticketing and live concert industry, Live Nation and subsidiary Ticketmaster have drawn the ire of not only pop musician Taylor Swift , but also the U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland and California Attorney General Rob Bonta.

On Thursday the federal Department of Justice announced it is joining 30 state attorneys general, including Bonta, in an antitrust lawsuit alleging that Live Nation has illegally maintained its monopoly over concerts, ticketing and promotions by locking venues into exclusive contracts, threatening retaliation, limiting artists’ access to the venues Live Nation owns and other practices.

- Bonta , in a statement : “While this illegal conduct benefits Live Nation’s bottom line — it hurts artists, their fans, and our economy. This lawsuit sends a clear message: Here in California, we’re committed to protecting consumers, holding industry accountable, enforcing antitrust laws, and ensuring a fair and competitive market.”

In addition to calls for Live Nation to sell off Ticketmaster, the lawsuit seeks financial compensation for California and ticket buyers who were overcharged by Live Nation, according to Bonta.

In its response, Live Nation said it’s not to blame for rising ticket prices , and said the lawsuit ignores the real causes “from rising production costs, to artist popularity, to 24/7 online ticket scalping.”

The lawsuit’s announcement comes a week after the Assembly appropriations committee held a bill that would have reined in some of Live Nation’s authority over primary ticket sales. Assemblymember Buffy Wicks , the author of the bill and chairperson of the committee, said in an email to CalMatters that if the lawsuit leads to the breakup of Live Nation’s monopoly, it will “benefit consumers and artists alike.”

- Wicks , an Oakland Democrat: “Having spent the past six months trying to tackle this issue at the state level, I’m thrilled to see … from both red and blue states to call for an end to these companies’ anticompetitive policies. It’s a seismic step, at a moment that truly calls for it.”

Sen. Wahab recall falls apart

From CalMatters Capitol reporter Sameea Kamal :

The current recall effort against Sen. Aisha Wahab — provoked by her contentious 2023 caste discrimination bill — won’t move forward , after proponents say they were unable to submit signatures.

The deadline was Thursday to turn in 42,802 valid signatures of voters in the district, which includes parts of Alameda and Santa Clara counties.

But Ritesh Tandon , one of the recall organizers and a congressional candidate in 2020, 2022 and the primary in March, said a line on the forms that were required to submit signatures was missing. He claimed they had collected more than 30,000 signatures by March.

The Secretary of State’s office, which cleared the proponents to start collecting signatures in December , confirmed it was notified of the problem, but said it told the proponents on Feb. 20 that the issue was not enough to invalidate the petition.

Tandon, however, said it was impossible to go back to the petition circulators — he said there were 10,000 — to add their signatures.

The organizers say they’ve learned lessons from the process and will try again to recall the Democratic senator from Fremont, whose first term runs until 2026.

- Wahab , to CalMatters: “It’s disappointing to see that this is their third attempt, based on the fact that I carried a bill about civil rights and they’re not happy with it. It’s disappointing to see the amount of time and energy and money that is going into this effort.”

The recall was originally started last year in response to Wahab’s bill to strengthen protections against caste discrimination in employment and housing. The Legislature passed a version of the bill , which was opposed by groups who alleged the bill unfairly targeted Hindu Californians, but Gov. Newsom vetoed it .

Now, recall organizers say the caste bill is no longer the reason, and instead take issue with Wahab’s work as the new chairperson of the Senate’s Public Safety committee and concerns over crime, including not responding to shooting deaths and vehicle fires in the district, and for introducing a bill that would prohibit asking housing applicants to disclose any criminal history.

And lastly: The price of protesting

College students and faculty members across California joined protests over the Gaza war. A grad students’ union is striking over how they were treated . What were the consequences for other students? Find out from CalMatters’ College Journalism Network . And don’t miss the timeline of all the protests at Cal State and UC campuses.

California Voices

CalMatters columnist Dan Walters: With Newsom’s governorship ending in 2026, the decades-long Delta tunnel project is nearing a decisive moment .

As Oakland pours hundreds of millions of dollars into policing street crime, its enforcement for wage theft is lacking, writes Francisco Antonio Callejas Bonilla , a former maintenance worker at the Radisson Hotel in Oakland.

Don’t miss CalMatters’ first Ideas Festival: It’s in Sacramento on June 5-6, and the full lineup is now available . It includes a broadband summit; sessions on artificial intelligence, climate, elections, homelessness and workforce development; and an exclusive IMAX screening of “Cities of the Future.” Find out more from our engagement team and buy tickets here .

Other things worth your time:

Some stories may require a subscription to read.

Meet the suburban moms helping Arizonans get abortions in CA // Los Angeles Times

Newsom prioritizes electric school buses over preschool for disabled children // EdSource

Private security firm accused of using force against UCLA protesters // Los Angeles Times

UCLA chancellor tells Congress he regrets not removing encampment sooner // EdSource

Alameda County DA sues Farmers Insurance over ‘widespread scheme’ // East Bay Times

PG&E customers face more increases in monthly utility bills // The Mercury News

Second judge finds workers at Tesla Fremont plant were racially harassed // The Mercury News

SF crime victims get help from an amateur sleuth // The San Francisco Standard

SF aquarium CEO resigns amid concerns about spending // San Francisco Chronicle

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

When Homework Was Banned

Published: November 3, 2023

In the early 1900s, Ladies' Home Journal took up a crusade against homework, enlisting doctors and parents who say it damages children's health. In 1901 California passed a law abolishing homework!

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Will Less Homework Stress Make California Students Happier?

A bill from a member of the Legislature’s happiness committee would require schools to come up with homework policies that consider the strain on students.

Mario Ramirez Garcia does homework on April 23, 2021. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters -->

BY LYNN LA, CalMatters

Update: The Assembly education committee on April 24 approved an amended version of the bill that softens some requirements and gives districts until the 2027-28 school year. Some bills before California’s Legislature don’t come from passionate policy advocates, or from powerful interest groups.

Sometimes, the inspiration comes from a family car ride.

While campaigning two years ago, Assemblymember Pilar Schiavo ’s daughter, then nine, asked from the backseat what her mother could do if she won.

Schiavo answered that she’d be able to make laws. Then, her daughter Sofia asked her if she could make a law banning homework.

“It was a kind of a joke,” the Santa Clarita Valley Democrat said in an interview, “though I’m sure she’d be happy if homework were banned.”

Still, the conversation got Schiavo thinking, she said. And while Assembly Bill 2999 — which faces its first big test on Wednesday — is far from a ban on homework, it would require school districts, county offices of education and charter schools to develop guidelines for K-12 students and would urge schools to be more intentional about “good,” or meaningful homework.

Among other things, the guidelines should consider students’ physical health, how long assignments take and how effective they are. But the bill’s main concern is mental health and when homework adds stress to students’ daily lives.

Homework’s impact on happiness is partly why Schiavo brought up the proposal last month during the first meeting of the Legislature’s select committee on happiness , led by former Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon .

“This feeling of loneliness and disconnection — I know when my kid is not feeling connected,” Schiavo, a member of the happiness committee, told CalMatters. “It’s when she’s alone in her room (doing homework), not playing with her cousin, not having dinner with her family.”

'I feel that I should teach them what I need to teach them when I’m with them in the room.' Casey Cuny, California Teacher of the Year

The bill analysis cites a survey of 15,000 California high schoolers from Challenge Success, a nonprofit affiliated with the Stanford Graduate School of Education. It found that 45% said homework was a major source of stress and that 52% considered most assignments to be busywork. The organization also reported in 2020 that students with higher workloads reported “symptoms of exhaustion and lower rates of sleep,” but that spending more time on homework did not necessarily lead to higher test scores.

Homework’s potential to also widen inequities is why Casey Cuny supports the measure. An English and mythology teacher at Valencia High School and 2024’s California Teacher of the Year , Cuny says language barriers, unreliable home internet, family responsibilities or other outside factors may contribute to a student falling behind on homework.

“I never want a kid’s grade to be low because they have divorced parents and their book was at their dad’s house when they were spending the weekend at mom’s house,” said Cuny, who plans to attend a press conference Wednesday to promote the bill.

In addition, as technology makes it easier for students to cheat — using artificial technology or chat threads to lift answers, for example — Schiavo says that the educators she has spoken to indicate they’re moving towards more in-class assignments.

Cuny agrees that an emphasis on classwork does help to rein in cheating and allows him to give students immediate feedback. “I feel that I should teach them what I need to teach them when I’m with them in the room,” he said.

Assemblymember Pilar Schiavo, far left, and other members of the Select Committee on Happiness and Public Policy Outcomes listen to speakers during an informational hearing on at the California Capitol in Sacramento on March 12, 2024. Photo by Fred Greaves for CalMatters

The bill says the local homework policies should have input from teachers, parents, school counselors, social workers and students; be distributed at the beginning of every school year; and be reevaluated every five years.

The Assembly Committee on Education is expected to hear the bill Wednesday. Schiavo says she has received bipartisan support and so far, no official opposition or support is listed in the bill analysis.

The measure’s provision for parental input may lead to disagreements given the recent culture war disputes between Democratic officials and parental rights groups backed by some Republican lawmakers. Because homework is such a big issue, “I’m sure there will be lively (school) board meetings,” Schiavo said.

Nevertheless, she says she hopes the proposal will overhaul the discussion around homework and mental health. The bill is especially pertinent now that the state is also poised to cut spending on mental health services for children with the passage of Proposition 1 .

Schiavo said the mother of a student with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder told her that the child’s struggle to finish homework has raised issues inside the house, as well as with the school’s principal and teachers.

“And I’m just like, it’s sixth grade!” Schaivo said. “What’s going on?”

Articles which extol the virtues of a report or article put out by a local newsroom.

Explainers and guides from our team of journalists, a curated news digest from trusted local newsrooms, and local government announcements and upcoming meetings, delivered every Monday morning to your inbox.

You are subscribed!

And look for our newsletter every Monday morning. See you then!

You're already subscribed

There was a problem with the submitted email address.

We can't subscribe you with the submitted email address. Please try another.

Make your Mondays more interesting and informative.

Homework in America

- 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education

Subscribe to the Brown Center on Education Policy Newsletter

Tom loveless tom loveless former brookings expert @tomloveless99.

March 18, 2014

- 18 min read

Part II of the 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education

Homework! The topic, no, just the word itself, sparks controversy. It has for a long time. In 1900, Edward Bok, editor of the Ladies Home Journal , published an impassioned article, “A National Crime at the Feet of Parents,” accusing homework of destroying American youth. Drawing on the theories of his fellow educational progressive, psychologist G. Stanley Hall (who has since been largely discredited), Bok argued that study at home interfered with children’s natural inclination towards play and free movement, threatened children’s physical and mental health, and usurped the right of parents to decide activities in the home.

The Journal was an influential magazine, especially with parents. An anti-homework campaign burst forth that grew into a national crusade. [i] School districts across the land passed restrictions on homework, culminating in a 1901 statewide prohibition of homework in California for any student under the age of 15. The crusade would remain powerful through 1913, before a world war and other concerns bumped it from the spotlight. Nevertheless, anti-homework sentiment would remain a touchstone of progressive education throughout the twentieth century. As a political force, it would lie dormant for years before bubbling up to mobilize proponents of free play and “the whole child.” Advocates would, if educators did not comply, seek to impose homework restrictions through policy making.

Our own century dawned during a surge of anti-homework sentiment. From 1998 to 2003, Newsweek , TIME , and People , all major national publications at the time, ran cover stories on the evils of homework. TIME ’s 1999 story had the most provocative title, “The Homework Ate My Family: Kids Are Dazed, Parents Are Stressed, Why Piling On Is Hurting Students.” People ’s 2003 article offered a call to arms: “Overbooked: Four Hours of Homework for a Third Grader? Exhausted Kids (and Parents) Fight Back.” Feature stories about students laboring under an onerous homework burden ran in newspapers from coast to coast. Photos of angst ridden children became a journalistic staple.

The 2003 Brown Center Report on American Education included a study investigating the homework controversy. Examining the most reliable empirical evidence at the time, the study concluded that the dramatic claims about homework were unfounded. An overwhelming majority of students, at least two-thirds, depending on age, had an hour or less of homework each night. Surprisingly, even the homework burden of college-bound high school seniors was discovered to be rather light, less than an hour per night or six hours per week. Public opinion polls also contradicted the prevailing story. Parents were not up in arms about homework. Most said their children’s homework load was about right. Parents wanting more homework out-numbered those who wanted less.

Now homework is in the news again. Several popular anti-homework books fill store shelves (whether virtual or brick and mortar). [ii] The documentary Race to Nowhere depicts homework as one aspect of an overwrought, pressure-cooker school system that constantly pushes students to perform and destroys their love of learning. The film’s website claims over 6,000 screenings in more than 30 countries. In 2011, the New York Times ran a front page article about the homework restrictions adopted by schools in Galloway, NJ, describing “a wave of districts across the nation trying to remake homework amid concerns that high stakes testing and competition for college have fueled a nightly grind that is stressing out children and depriving them of play and rest, yet doing little to raise achievement, especially in elementary grades.” In the article, Vicki Abeles, the director of Race to Nowhere , invokes the indictment of homework lodged a century ago, declaring, “The presence of homework is negatively affecting the health of our young people and the quality of family time.” [iii]

A petition for the National PTA to adopt “healthy homework guidelines” on change.org currently has 19,000 signatures. In September 2013, Atlantic featured an article, “My Daughter’s Homework is Killing Me,” by a Manhattan writer who joined his middle school daughter in doing her homework for a week. Most nights the homework took more than three hours to complete.

The Current Study

A decade has passed since the last Brown Center Report study of homework, and it’s time for an update. How much homework do American students have today? Has the homework burden increased, gone down, or remained about the same? What do parents think about the homework load?

A word on why such a study is important. It’s not because the popular press is creating a fiction. The press accounts are built on the testimony of real students and real parents, people who are very unhappy with the amount of homework coming home from school. These unhappy people are real—but they also may be atypical. Their experiences, as dramatic as they are, may not represent the common experience of American households with school-age children. In the analysis below, data are analyzed from surveys that are methodologically designed to produce reliable information about the experiences of all Americans. Some of the surveys have existed long enough to illustrate meaningful trends. The question is whether strong empirical evidence confirms the anecdotes about overworked kids and outraged parents.

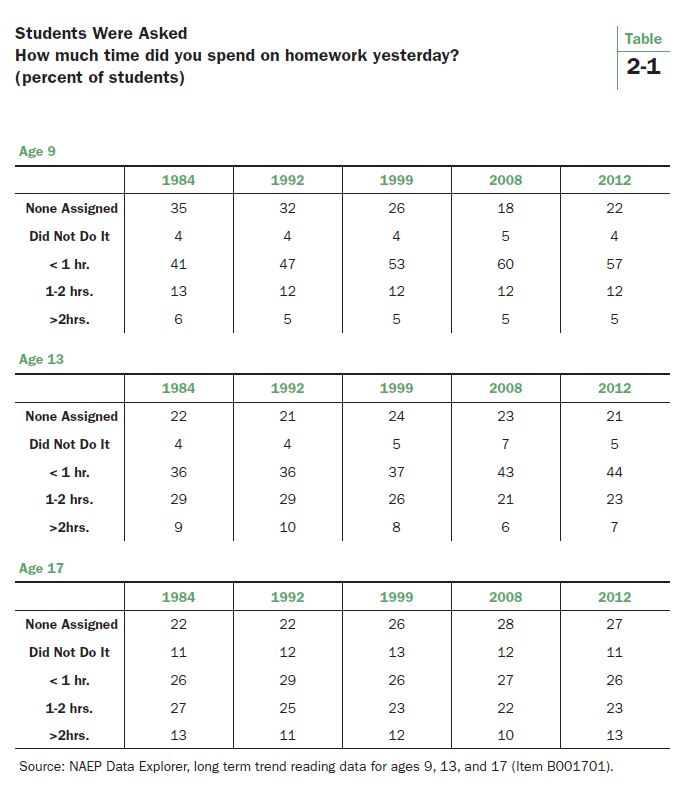

Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) provide a good look at trends in homework for nearly the past three decades. Table 2-1 displays NAEP data from 1984-2012. The data are from the long-term trend NAEP assessment’s student questionnaire, a survey of homework practices featuring both consistently-worded questions and stable response categories. The question asks: “How much time did you spend on homework yesterday?” Responses are shown for NAEP’s three age groups: 9, 13, and 17. [iv]

Today’s youngest students seem to have more homework than in the past. The first three rows of data for age 9 reveal a shift away from students having no homework, declining from 35% in 1984 to 22% in 2012. A slight uptick occurred from the low of 18% in 2008, however, so the trend may be abating. The decline of the “no homework” group is matched by growth in the percentage of students with less than an hour’s worth, from 41% in 1984 to 57% in 2012. The share of students with one to two hours of homework changed very little over the entire 28 years, comprising 12% of students in 2012. The group with the heaviest load, more than two hours of homework, registered at 5% in 2012. It was 6% in 1984.

The amount of homework for 13-year-olds appears to have lightened slightly. Students with one to two hours of homework declined from 29% to 23%. The next category down (in terms of homework load), students with less than an hour, increased from 36% to 44%. One can see, by combining the bottom two rows, that students with an hour or more of homework declined steadily from 1984 to 2008 (falling from 38% to 27%) and then ticked up to 30% in 2012. The proportion of students with the heaviest load, more than two hours, slipped from 9% in 1984 to 7% in 2012 and ranged between 7-10% for the entire period.

For 17-year-olds, the homework burden has not varied much. The percentage of students with no homework has increased from 22% to 27%. Most of that gain occurred in the 1990s. Also note that the percentage of 17-year-olds who had homework but did not do it was 11% in 2012, the highest for the three NAEP age groups. Adding that number in with the students who didn’t have homework in the first place means that more than one-third of seventeen year olds (38%) did no homework on the night in question in 2012. That compares with 33% in 1984. The segment of the 17-year-old population with more than two hours of homework, from which legitimate complaints of being overworked might arise, has been stuck in the 10%-13% range.

The NAEP data point to four main conclusions:

- With one exception, the homework load has remained remarkably stable since 1984.

- The exception is nine-year-olds. They have experienced an increase in homework, primarily because many students who once did not have any now have some. The percentage of nine-year-olds with no homework fell by 13 percentage points, and the percentage with less than an hour grew by 16 percentage points.

- Of the three age groups, 17-year-olds have the most bifurcated distribution of the homework burden. They have the largest percentage of kids with no homework (especially when the homework shirkers are added in) and the largest percentage with more than two hours.

- NAEP data do not support the idea that a large and growing number of students have an onerous amount of homework. For all three age groups, only a small percentage of students report more than two hours of homework. For 1984-2012, the size of the two hours or more groups ranged from 5-6% for age 9, 6-10% for age 13, and 10-13% for age 17.

Note that the item asks students how much time they spent on homework “yesterday.” That phrasing has the benefit of immediacy, asking for an estimate of precise, recent behavior rather than an estimate of general behavior for an extended, unspecified period. But misleading responses could be generated if teachers lighten the homework of NAEP participants on the night before the NAEP test is given. That’s possible. [v] Such skewing would not affect trends if it stayed about the same over time and in the same direction (teachers assigning less homework than usual on the day before NAEP). Put another way, it would affect estimates of the amount of homework at any single point in time but not changes in the amount of homework between two points in time.

A check for possible skewing is to compare the responses above with those to another homework question on the NAEP questionnaire from 1986-2004 but no longer in use. [vi] It asked students, “How much time do you usually spend on homework each day?” Most of the response categories have different boundaries from the “last night” question, making the data incomparable. But the categories asking about no homework are comparable. Responses indicating no homework on the “usual” question in 2004 were: 2% for age 9-year-olds, 5% for 13 year olds, and 12% for 17-year-olds. These figures are much less than the ones reported in Table 2-1 above. The “yesterday” data appear to overstate the proportion of students typically receiving no homework.

The story is different for the “heavy homework load” response categories. The “usual” question reported similar percentages as the “yesterday” question. The categories representing the most amount of homework were “more than one hour” for age 9 and “more than two hours” for ages 13 and 17. In 2004, 12% of 9-year-olds said they had more than one hour of daily homework, while 8% of 13-year-olds and 12% of 17-year-olds said they had more than two hours. For all three age groups, those figures declined from1986 to 2004. The decline for age 17 was quite large, falling from 17% in 1986 to 12% in 2004.

The bottom line: regardless of how the question is posed, NAEP data do not support the view that the homework burden is growing, nor do they support the belief that the proportion of students with a lot of homework has increased in recent years. The proportion of students with no homework is probably under-reported on the long-term trend NAEP. But the upper bound of students with more than two hours of daily homework appears to be about 15%–and that is for students in their final years of high school.

College Freshmen Look Back

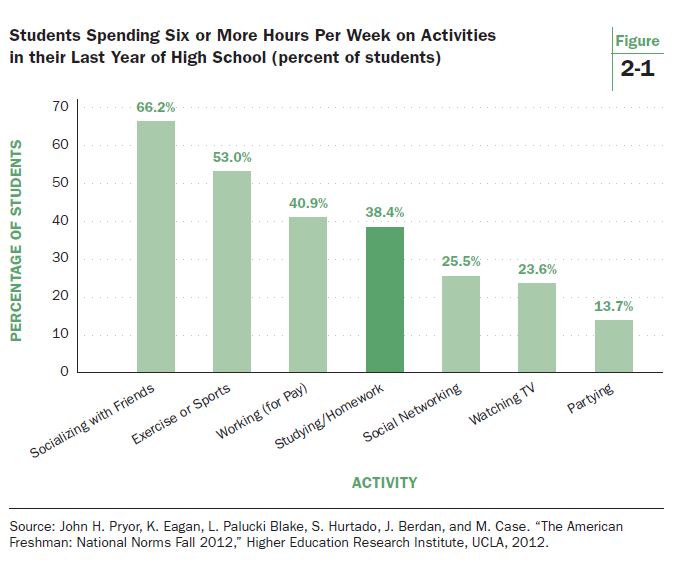

There is another good source of information on high school students’ homework over several decades. The Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA conducts an annual survey of college freshmen that began in 1966. In 1986, the survey started asking a series of questions regarding how students spent time in the final year of high school. Figure 2-1 shows the 2012 percentages for the dominant activities. More than half of college freshmen say they spent at least six hours per week socializing with friends (66.2%) and exercising/sports (53.0%). About 40% devoted that much weekly time to paid employment.

Homework comes in fourth pace. Only 38.4% of students said they spent at least six hours per week studying or doing homework. When these students were high school seniors, it was not an activity central to their out of school lives. That is quite surprising. Think about it. The survey is confined to the nation’s best students, those attending college. Gone are high school dropouts. Also not included are students who go into the military or attain full time employment immediately after high school. And yet only a little more than one-third of the sampled students, devoted more than six hours per week to homework and studying when they were on the verge of attending college.

Another notable finding from the UCLA survey is how the statistic is trending (see Figure 2-2). In 1986, 49.5% reported spending six or more hours per week studying and doing homework. By 2002, the proportion had dropped to 33.4%. In 2012, as noted in Figure 2-1, the statistic had bounced off the historical lows to reach 38.4%. It is slowly rising but still sits sharply below where it was in 1987.

What Do Parents Think?

Met Life has published an annual survey of teachers since 1984. In 1987 and 2007, the survey included questions focusing on homework and expanded to sample both parents and students on the topic. Data are broken out for secondary and elementary parents and for students in grades 3-6 and grades 7-12 (the latter not being an exact match with secondary parents because of K-8 schools).

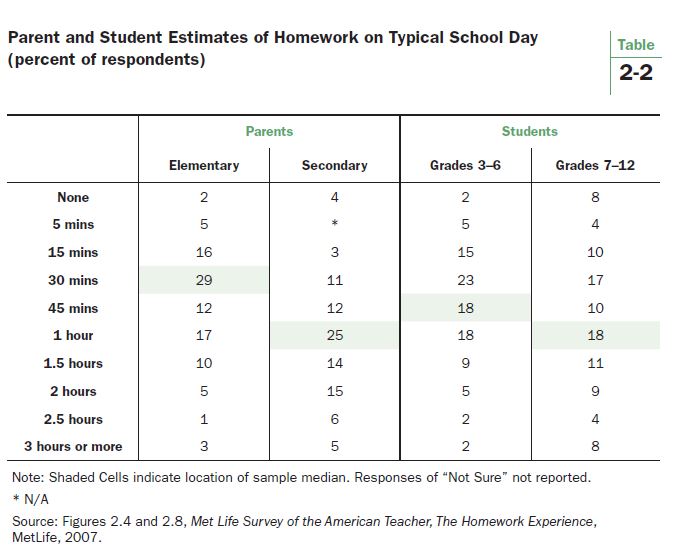

Table 2-2 shows estimates of homework from the 2007 survey. Respondents were asked to estimate the amount of homework on a typical school day (Monday-Friday). The median estimate of each group of respondents is shaded. As displayed in the first column, the median estimate for parents of an elementary student is that their child devotes about 30 minutes to homework on the typical weekday. Slightly more than half (52%) estimate 30 minutes or less; 48% estimate 45 minutes or more. Students in grades 3-6 (third column) give a median estimate that is a bit higher than their parents’ (45 minutes), with almost two-thirds (63%) saying 45 minutes or less is the typical weekday homework load.

One hour of homework is the median estimate for both secondary parents and students in grade 7-12, with 55% of parents reporting an hour or less and about two-thirds (67%) of students reporting the same. As for the prevalence of the heaviest homework loads, 11% of secondary parents say their children spend more than two hours on weekday homework, and 12% is the corresponding figure for students in grades 7-12.

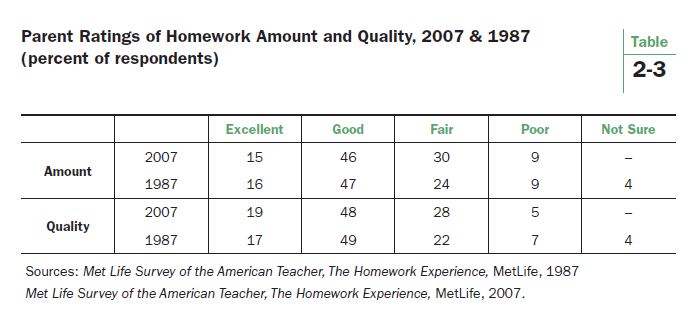

The Met Life surveys in 1987 and 2007 asked parents to evaluate the amount and quality of homework. Table 2-3 displays the results. There was little change over the two decades separating the two surveys. More than 60% of parents rate the amount of homework as good or excellent, and about two-thirds give such high ratings to the quality of the homework their children are receiving. The proportion giving poor ratings to either the quantity or quality of homework did not exceed 10% on either survey.

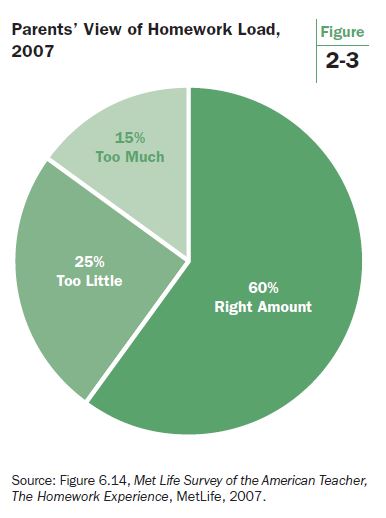

Parental dissatisfaction with homework comes in two forms: those who feel schools give too much homework and those who feel schools do not give enough. The current wave of journalism about unhappy parents is dominated by those who feel schools give too much homework. How big is this group? Not very big (see Figure 2-3). On the Met Life survey, 60% of parents felt schools were giving the right amount of homework, 25% wanted more homework, and only 15% wanted less.

National surveys on homework are infrequent, but the 2006-2007 period had more than one. A poll conducted by Public Agenda in 2006 reported similar numbers as the Met Life survey: 68% of parents describing the homework load as “about right,” 20% saying there is “too little homework,” and 11% saying there is “too much homework.” A 2006 AP-AOL poll found the highest percentage of parents reporting too much homework, 19%. But even in that poll, they were outnumbered by parents believing there is too little homework (23%), and a clear majority (57%) described the load as “about right.” A 2010 local survey of Chicago parents conducted by the Chicago Tribune reported figures similar to those reported above: approximately two-thirds of parents saying their children’s homework load is “about right,” 21% saying it’s not enough, and 12% responding that the homework load is too much.

Summary and Discussion

In recent years, the press has been filled with reports of kids over-burdened with homework and parents rebelling against their children’s oppressive workload. The data assembled above call into question whether that portrait is accurate for the typical American family. Homework typically takes an hour per night. The homework burden of students rarely exceeds two hours a night. The upper limit of students with two or more hours per night is about 15% nationally—and that is for juniors or seniors in high school. For younger children, the upper boundary is about 10% who have such a heavy load. Polls show that parents who want less homework range from 10%-20%, and that they are outnumbered—in every national poll on the homework question—by parents who want more homework, not less. The majority of parents describe their children’s homework burden as about right.

So what’s going on? Where are the homework horror stories coming from?

The Met Life survey of parents is able to give a few hints, mainly because of several questions that extend beyond homework to other aspects of schooling. The belief that homework is burdensome is more likely held by parents with a larger set of complaints and concerns. They are alienated from their child’s school. About two in five parents (19%) don’t believe homework is important. Compared to other parents, these parents are more likely to say too much homework is assigned (39% vs. 9%), that what is assigned is just busywork (57% vs. 36%), and that homework gets in the way of their family spending time together (51% vs. 15%). They are less likely to rate the quality of homework as excellent (3% vs. 23%) or to rate the availability and responsiveness of teachers as excellent (18% vs. 38%). [vii]

They can also convince themselves that their numbers are larger than they really are. Karl Taro Greenfeld, the author of the Atlantic article mentioned above, seems to fit that description. “Every parent I know in New York City comments on how much homework their children have,” Mr. Greenfeld writes. As for those parents who do not share this view? “There is always a clique of parents who are happy with the amount of homework. In fact, they would prefer more . I tend not to get along with that type of parent.” [viii]

Mr. Greenfeld’s daughter attends a selective exam school in Manhattan, known for its rigorous expectations and, yes, heavy homework load. He had also complained about homework in his daughter’s previous school in Brentwood, CA. That school was a charter school. After Mr. Greenfeld emailed several parents expressing his complaints about homework in that school, the school’s vice-principal accused Mr. Greenfeld of cyberbullying. The lesson here is that even schools of choice are not immune from complaints about homework.

The homework horror stories need to be read in a proper perspective. They seem to originate from the very personal discontents of a small group of parents. They do not reflect the experience of the average family with a school-age child. That does not diminish these stories’ power to command the attention of school officials or even the public at large. But it also suggests a limited role for policy making in settling such disputes. Policy is a blunt instrument. Educators, parents, and kids are in the best position to resolve complaints about homework on a case by case basis. Complaints about homework have existed for more than a century, and they show no signs of going away.

Part II Notes:

[i]Brian Gill and Steven Schlossman, “A Sin Against Childhood: Progressive Education and the Crusade to Abolish Homework, 1897-1941,” American Journal of Education , vol. 105, no. 1 (Nov., 1996), 27-66. Also see Brian P. Gill and Steven L. Schlossman, “Villain or Savior? The American Discourse on Homework, 1850-2003,” Theory into Practice , 43, 3 (Summer 2004), pp. 174-181.