Subject Knowledge >

Performance Tasks: Physical Education

* Evaluated Practicum

Performance Tasks revised 21 Jul 09

Other Portfolio Pages: Introduction - Teaching Philosophy - Subject Knowledge - Instructional Strategies Assessment - Adaptive Instruction - Credentials

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

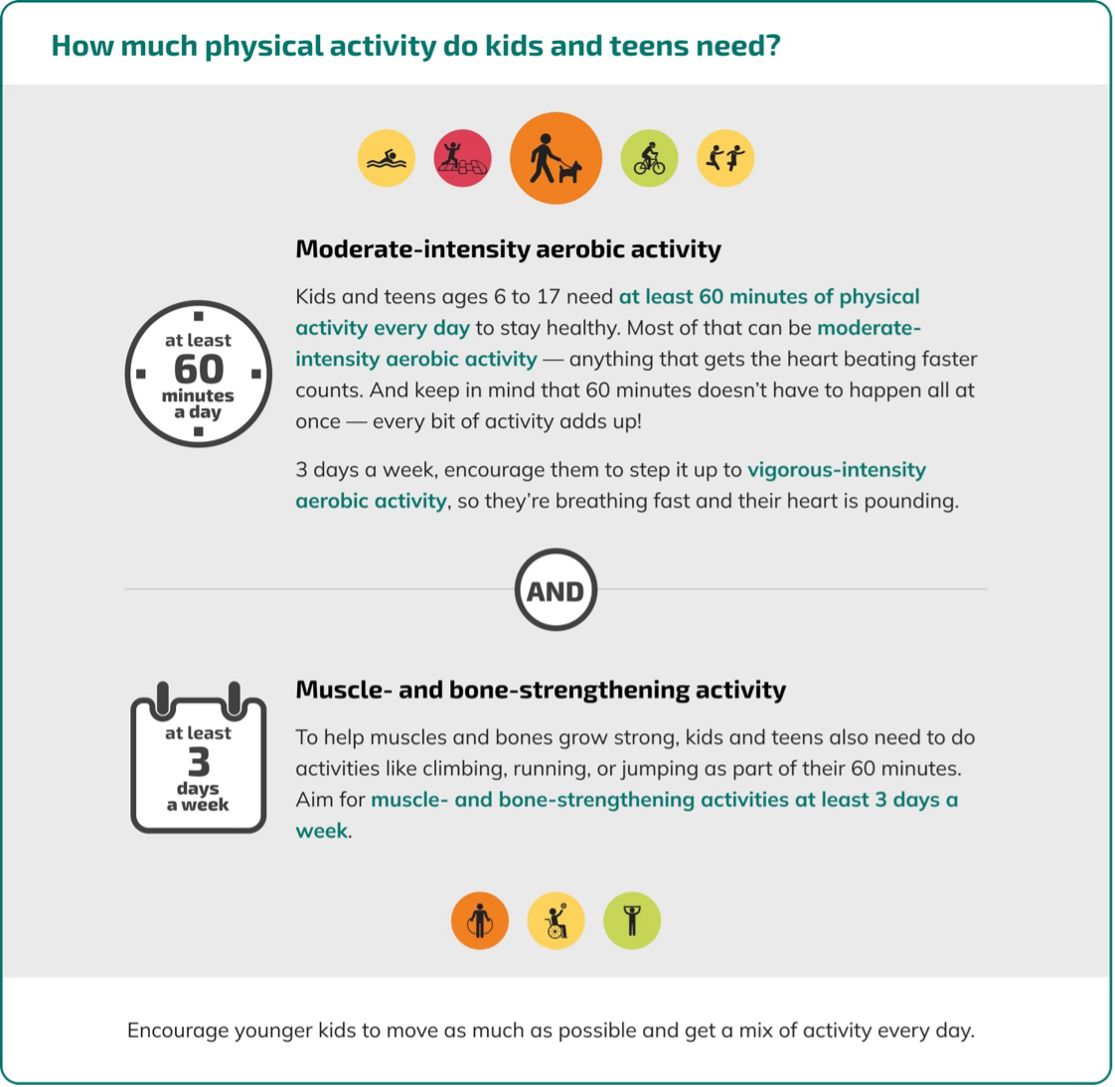

Physical Education

Physical education is the foundation of a Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program. 1, 2 It is an academic subject characterized by a planned, sequential K–12 curriculum (course of study) that is based on the national standards for physical education. 2–4 Physical education provides cognitive content and instruction designed to develop motor skills, knowledge, and behaviors for physical activity and physical fitness. 2–4 Supporting schools to establish physical education daily can provide students with the ability and confidence to be physically active for a lifetime. 2–4

There are many benefits of physical education in schools. When students get physical education, they can 5-7 :

- Increase their level of physical activity.

- Improve their grades and standardized test scores.

- Stay on-task in the classroom.

Increased time spent in physical education does not negatively affect students’ academic achievement.

Strengthen Physical Education in Schools [PDF – 437 KB] —This data brief defines physical education, provides a snapshot of current physical education practices in the United States, and highlights ways to improve physical education through national guidance and practical strategies and resources. This was developed by Springboard to Active Schools in collaboration with CDC.

Secular Changes in Physical Education Attendance Among U.S. High School Students, YRBS 1991–2013

The Secular Changes in Physical Education Attendance Among U.S. High School Students report [PDF – 3 MB] explains the secular changes (long-term trends) in physical education attendance among US high school students over the past two decades. Between 1991 and 2013, US high school students’ participation in school-based physical education classes remained stable, but at a level much lower than the national recommendation of daily physical education. In order to maximize the benefits of physical education, the adoption of policies and programs aimed at increasing participation in physical education among all US students should be prioritized. Download the report for detailed, nationwide findings.

Physical Education Analysis Tool (PECAT)

The Physical Education Curriculum Analysis Tool (PECAT) [PDF – 6 MB] is a self-assessment and planning guide developed by CDC. It is designed to help school districts and schools conduct clear, complete, and consistent analyses of physical education curricula, based upon national physical education standards.

Visit our PECAT page to learn more about how schools can use this tool.

- CDC Monitoring Student Fitness Levels1 [PDF – 1.64 MB]

- CDC Ideas for Parents: Physical Education [PDF – 2 MB]

- SHAPE America: The Essential Components of Physical Education (2015) [PDF – 391 KB]

- SHAPE America: Appropriate Instructional Practice Guidelines for Elementary, Middle School, and High School Physical Education [PDF – 675 KB]

- SHAPE America: National Standards and Grade-Level Outcomes for K–12 Physical Education 2014

- SHAPE America: National Standards for K–12 Physical Education (2013)

- SHAPE America Resources

- Youth Compendium of Physical Activities for Physical Education Teachers (2018) [PDF – 145 KB]

- Social Emotional Learning Policies and Physical Education

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Guide for Developing Comprehensive School Physical Activity Programs . Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School health guidelines to promote healthy eating and physical activity. MMWR . 2011;60(RR05):1–76.

- Institute of Medicine. Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. Retrieved from http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=18314&page=R1 .

- SHAPE America. T he Essential Components of Physical Education . Reston, VA: SHAPE America; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.shapeamerica.org/upload/TheEssentialComponentsOfPhysicalEducation.pdf [PDF – 392 KB].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance . Atlanta, GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health and Academic Achievement. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

- Michael SL, Merlo C, Basch C, et al. Critical connections: health and academics . Journal of School Health . 2015;85(11):740–758.

Healthy Youth

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

What is a Performance Task? (Part 1)

Defined Learning

Performance Task PD with Jay McTighe — Blog

A performance task is any learning activity or assessment that asks students to perform to demonstrate their knowledge, understanding and proficiency. Performance tasks yield a tangible product and/or performance that serve as evidence of learning. Unlike a selected-response item (e.g., multiple-choice or matching) that asks students to select from given alternatives, a performance task presents a situation that calls for learners to apply their learning in context.

Performance tasks are routinely used in certain disciplines, such as visual and performing arts, physical education, and career-technology where performance is the natural focus of instruction. However, such tasks can (and should) be used in every subject area and at all grade levels.

Characteristics of Performance Tasks

While any performance by a learner might be considered a performance task (e.g., tying a shoe or drawing a picture), it is useful to distinguish between the application of specific and discrete skills (e.g., dribbling a basketball) from genuine performance in context (e.g., playing the game of basketball in which dribbling is one of many applied skills). Thus, when I use the term performance tasks, I am referring to more complex and authentic performances.

Here are seven general characteristics of performance tasks:

- Performance tasks call for the application of knowledge and skills, not just recall or recognition.

In other words, the learner must actually use their learning to perform . These tasks typically yield a tangible product (e.g., graphic display, blog post) or performance (e.g., oral presentation, debate) that serve as evidence of their understanding and proficiency.

2. Performance tasks are open-ended and typically do not yield a single, correct answer.

Unlike selected- or brief constructed- response items that seek a “right” answer, performance tasks are open-ended. Thus, there can be different responses to the task that still meet success criteria. These tasks are also open in terms of process; i.e., there is typically not a single way of accomplishing the task.

3. Performance tasks establish novel and authentic contexts for performance.

These tasks present realistic conditions and constraints for students to navigate. For example, a mathematics task would present students with a never-before-seen problem that cannot be solved by simply “plugging in” numbers into a memorized algorithm. In an authentic task, students need to consider goals, audience, obstacles, and options to achieve a successful product or performance. Authentic tasks have a side benefit — they convey purpose and relevance to students, helping learners see a reason for putting forth effort in preparing for them.

4. Performance tasks provide evidence of understanding via transfer.

Understanding is revealed when students can transfer their learning to new and “messy” situations. Note that not all performances require transfer. For example, playing a musical instrument by following the notes or conducting a step-by-step science lab require minimal transfer. In contrast, rich performance tasks are open-ended and call “higher-order thinking” and the thoughtful application of knowledge and skills in context, rather than a scripted or formulaic performance.

5. Performance tasks are multi-faceted.

Unlike traditional test “items” that typically assess a single skill or fact, performance tasks are more complex. They involve multiple steps and thus can be used to assess several standards or outcomes.

6. Performance tasks can integrate two or more subjects as well as 21st century skills.

In the wider world beyond the school, most issues and problems do not present themselves neatly within subject area “silos.” While performance tasks can certainly be content-specific (e.g., mathematics, science, social studies), they also provide a vehicle for integrating two or more subjects and/or weaving in 21st century skills and Habits of Mind. One natural way of integrating subjects is to include a reading, research, and/or communication component (e.g., writing, graphics, oral or technology presentation) to tasks in content areas like social studies, science, health, business, health/physical education. Such tasks encourage students to see meaningful learning as integrated, rather than something that occurs in isolated subjects and segments.

7. Performances on open-ended tasks are evaluated with established criteria and rubrics.

Since these tasks do not yield a single answer, student products and performances should be judged against appropriate criteria aligned to the goals being assessed. Clearly defined and aligned criteria enable defensible, judgment-based evaluation. More detailed scoring rubrics, based on criteria, are used to profile varying levels of understanding and proficiency.

Let’s look at a few examples of performance tasks that reflect these characteristics:

Botanical Design (upper elementary)

Your landscape architectural firm is competing for a grant to redesign a public space in your community and to improve its appearance and utility. The goal of the grant is to create a community area where people can gather to enjoy themselves and the native plants of the region. The grant also aspires to educate people as to the types of trees, shrubs, and flowers that are native to the region. Your team will be responsible for selecting a public place in your area that you can improve for visitors and members of the community. You will have to research the area selected, create a scale drawing of the layout of the area you plan to redesign, propose a new design to include native plants of your region, and prepare educational materials that you will incorporate into the design.

Check out the full performance task from Defined STEM , here: Botanical Design Performance Task . Defined STEM is an online resource where you can find hundreds of K-12 standards-aligned project based performance tasks.

Evaluate the Claim (upper elementary/ middle school)

The Pooper Scooper Kitty Litter Company claims that their litter is 40% more absorbent than other brands. You are a Consumer Advocates researcher who has been asked to evaluate their claim. Develop a plan for conducting the investigation. Your plan should be specific enough so that the lab investigators could follow it to evaluate the claim.

Moving to South America (middle school)

Since they know that you have just completed a unit on South America, your aunt and uncle have asked you to help them decide where they should live when your aunt starts her new job as a consultant to a computer company operating throughout the region. They can choose to live anywhere in the continent.

Your task is to research potential home locations by examining relevant geographic, climatic, political, economic, historic, and cultural considerations. Then, write a letter to your aunt and uncle with your recommendation about a place for them to move. Be sure to explain your decision with reasons and evidence from your research.

Accident Scene Investigation (high school)

You are a law enforcement officer who has been hired by the District Attorney’s Office to set-up an accident scene investigation unit. Your first assignment is to work with a reporter from the local newspaper to develop a series of information pieces to inform the community about the role and benefits of applying forensic science to accident investigations.

Your team will share this information with the public through the various media resources owned and operated by the newspaper.

Check out the full performance task from Defined STEM here: Accident Scene Investigation Performance Task

In sum, performance tasks like these can be used to engage students in meaningful learning. Since rich performance tasks establish authentic contexts that reflect genuine applications of knowledge, students are often motivated and engaged by such “real world” challenges.

When used as assessments, performance tasks enable teachers to gauge student understanding and proficiency with complex processes (e.g., research, problem solving, and writing), not just measure discrete knowledge. They are well suited to integrating subject areas and linking content knowledge with the 21st Century Skills such as critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, communication, and technology use. Moreover, performance-based assessment can also elicit Habits of Mind, such as precision and perseverance.

For a collection of authentic performance tasks and associated rubrics, see Defined STEM : https://www.definedstem.com

For a complete professional development course on performance tasks for your school or district, see Performance Task PD with Jay McTighe : http://www.performancetask.com

For more information about the design and use of performance tasks, see Core Learning: Assessing What Matters Most by Jay McTighe: http://www.schoolimprovement.com

Article originally posted: URL: http://performancetask.com/what-is-a-performance-task | Article Title: What is a Performance Task? | Website Title:PerformanceTask.com | Publication date: 2015–04–12

Written by Defined Learning

More from defined learning and performance task pd with jay mctighe — blog.

Why Should We Use Performance Tasks? (Part 2)

How will we evaluate student performance on tasks? (Part 6)

How Can We Differentiate Performance Tasks? (Part 4)

How Should We Teach Toward Success with Performance Tasks? (Part 7)

Recommended from medium.

How to become a Senior Designer — from an ex-Google, Meta Designer

Growth starts with you, stepping up proactively, building opinions and voicing opinions like an owner, despite your fear and doubt….

Sufyan Maan, M.Eng

ILLUMINATION

What Happens When You Start Reading Every Day

Think before you speak. read before you think. — fran lebowitz.

Medium's Huge List of Publications Accepting Submissions

Karolina Kozmana

Common side effects of not drinking

By rejecting alcohol, you reject something very human, an extra limb that we have collectively grown to deal with reality and with each….

Hazel Paradise

How I Create Passive Income With No Money

Many ways to start a passive income today.

Torsten Walbaum

Towards Data Science

What 10 Years at Uber, Meta and Startups Taught Me About Data Analytics

Advice for data scientists and managers.

10 Seconds That Ended My 20 Year Marriage

It’s august in northern virginia, hot and humid. i still haven’t showered from my morning trail run. i’m wearing my stay-at-home mom….

Text to speech

Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School (2013)

Chapter: 5 approaches to physical education in schools.

Approaches to Physical Education in Schools

Key Messages

• Because it is guaranteed to reach virtually all children, physical education is the only sure opportunity for nearly all school-age children to access health-enhancing physical activities.

• High-quality physical education programs are characterized by (1) instruction by certified physical education teachers, (2) a minimum of 150 minutes per week (30 minutes per day) for children in elementary schools and 225 minutes per week (45 minutes per day) for students in middle and high schools, and (3) tangible standards for student achievement and for high school graduation.

• Students are more physically active on days on which they have physical education.

• Quality physical education has strong support from both parents and child health professional organizations.

• Several models and examples demonstrate that physical education scheduled during the school day is feasible on a daily basis.

• Substantial discrepancies exist in state mandates regarding the time allocated for physical education.

• Nearly half of school administrators (44 percent) reported cutting significant time from physical education and recess to increase time spent in reading and mathematics since passage of the No Child Left Behind Act.

• Standardized national-level data on the provision of and participation, performance, and extent of engagement in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity are insufficient to allow assessment of the current status and trends in physical education in the United States.

• Systematic research is needed on personal, curricular, and policy barriers to successful physical education.

• The long-term impact of physical education has been understudied and should be a research priority to support the development of evidence-based policies.

P hysical education is a formal content area of study in schools that is standards based and encompasses assessment based on standards and benchmarks. It is defined in Chapter 1 as “a planned sequential K-12 standards-based program of curricula and instruction designed to develop motor skills, knowledge, and behaviors of healthy active living, physical fitness, sportsmanship, self-efficacy, and emotional intelligence.” As a school subject, physical education is focused on teaching school-aged children the science and methods of physically active, healthful living (NASPE, 2012). It is an avenue for engaging in developmentally appropriate physical activities designed for children to develop their fitness, gross motor skills, and health (Sallis et al., 2003; Robinson and Goodway, 2009; Robinson, 2011). This chapter (1) provides a perspective on physical education in the context of schooling; (2) elaborates on the importance of physical education to child development; (3) describes the consensus on the characteristics of quality physical education programs; (4) reviews current national, state, and local education policies that affect the quality of physical education; and (5) examines barriers to quality physical education and solutions for overcoming them.

PHYSICAL EDUCATION IN THE CONTEXT OF SCHOOLING

Physical education became a subject matter in schools (in the form of German and Swedish gymnastics) at the beginning of the 19th century (Hackensmith, 1966). Its role in human health was quickly recognized. By the turn of the 20th century, personal hygiene and exercise for bodily health were incorporated in the physical education curriculum as the major learning outcomes for students (Weston, 1962). The exclusive focus on health, however, was criticized by educator Thomas Wood (1913; Wood and Cassidy, 1930) as too narrow and detrimental to the development of the whole child. The education community subsequently adopted Wood’s inclusive approach to physical education whereby fundamental movements and physical skills for games and sports were incorporated as the major instructional content. During the past 15 years, physical education has once again evolved to connect body movement to its consequences (e.g., physical activity and health), teaching children the science of healthful living and skills needed for an active lifestyle (NASPE, 2004).

Sallis and McKenzie (1991) published a landmark paper stating that physical education is education content using a “comprehensive but physically active approach that involves teaching social, cognitive, and physical skills, and achieving other goals through movement” (p. 126). This perspective is also emphasized by Siedentop (2009), who states that physical education is education through the physical. Sallis and McKenzie (1991) stress two main goals of physical education: (1) prepare children and youth for a lifetime of physical activity and (2) engage them in physical activity during physical education. These goals represent the lifelong benefits of health-enhancing physical education that enable children and adolescents to become active adults throughout their lives.

Physical Education as Part of Education

In institutionalized education, the main goal has been developing children’s cognitive capacity in the sense of learning knowledge in academic disciplines. This goal dictates a learning environment in which seated learning behavior is considered appropriate and effective and is rewarded. Physical education as part of education provides the only opportunity for all children to learn about physical movement and engage in physical activity. As noted, its goal and place in institutionalized education have changed from the original focus on teaching hygiene and health to educating children about the many forms and benefits of physical movement, including sports and exercise. With a dramatic expansion of content beyond the original Swedish and German gymnastics programs of the 19th century, physical education has evolved to become a content

area with diverse learning goals that facilitate the holistic development of children (NASPE, 2004).

To understand physical education as a component of the education system, it is important to know that the education system in the United States does not operate with a centralized curriculum. Learning standards are developed by national professional organizations such as the National Association for Sport and Physical Education (NASPE) and/or state education agencies rather than by the federal Department of Education; all curricular decisions are made locally by school districts or individual schools in compliance with state standards. Physical education is influenced by this system, which leads to great diversity in policies and curricula. According to NASPE and the American Heart Association (2010), although most states have begun to mandate physical education for both elementary and secondary schools, the number of states that allow waivers/exemptions from or substitutions for physical education increased from 27 and 18 in 2006 to 32 and 30 in 2010, respectively. These expanded waiver and substitution policies (discussed in greater detail later in the chapter) increase the possibility that students will opt out of physical education for nonmedical reasons.

Curriculum Models

Given that curricula are determined at the local level in the United States, encompassing national standards, state standards, and state-adopted textbooks that meet and are aligned with the standards, physical education is taught in many different forms and structures. Various curriculum models are used in instruction, including movement education, sport education, and fitness education. In terms of engagement in physical activity, two perspectives are apparent. First, programs in which fitness education curricula are adopted are effective at increasing in-class physical activity (Lonsdale et al., 2013). Second, in other curriculum models, physical activity is considered a basis for students’ learning skill or knowledge that the lesson is planned for them to learn. A paucity of nationally representative data is available with which to demonstrate the relationship between the actual level of physical activity in which students are engaged and the curriculum models adopted by their schools.

Movement Education

Movement has been a cornerstone of physical education since the 1800s. Early pioneers (Francois Delsarte, Liselott Diem, Rudolf von Laban) focused on a child’s ability to use his or her body for self-expression (Abels and Bridges, 2010). Exemplary works and curriculum descriptions include those by Laban himself (Laban, 1980) and others (e.g., Logsdon et al.,

1984). Over time, however, the approach shifted from concern with the inner attitude of the mover to a focus on the function and application of each movement (Abels and Bridges, 2010). In the 1960s, the intent of movement education was to apply four movement concepts to the three domains of learning (i.e., cognitive, psychomotor, and affective). The four concepts were body (representing the instrument of the action); space (where the body is moving); effort (the quality with which the movement is executed); and relationships (the connections that occur as the body moves—with objects, people, and the environment; Stevens-Smith, 2004). The importance of movement in physical education is evidenced by its inclusion in the first two NASPE standards for K-12 physical education (NASPE, 2004; see Box 5-7 later in this chapter).

These standards emphasize the need for children to know basic movement concepts and be able to perform basic movement patterns. It is imperative for physical educators to foster motor success and to provide children with a basic skill set that builds their movement repertoire, thus allowing them to engage in various forms of games, sports, and other physical activities (see also Chapter 3 ).

Sport Education

One prevalent physical education model is the sport education curriculum designed by Daryl Siedentop (Siedentop, 1994; Siedentop et al., 2011). The goal of the model is to “educate students to be players in the fullest sense and to help them develop as competent, literate, and enthusiastic sportspersons” (2011, p. 4, emphasis in original). The model entails a unique instructional structure featuring sport seasons that are used as the basis for planning and teaching instructional units. Students are organized into sport organizations (teams) and play multiple roles as team managers, coaches, captains, players, referees, statisticians, public relations staff, and others to mimic a professional sports organization. A unit is planned in terms of a sports season, including preseason activity/practice, regular-season competition, playoffs and/or tournaments, championship competition, and a culminating event (e.g., an awards ceremony or sport festivity). Depending on the developmental level of students, the games are simplified or modified to encourage maximum participation. In competition, students play the roles noted above in addition to the role of players. A sport education unit thus is much longer than a conventional physical education unit. Siedentop and colleagues (2011) recommend 20 lessons per unit, so that all important curricular components of the model can be implemented.

Findings from research on the sport education model have been reviewed twice. Wallhead and O’Sullivan (2005) report that evidence is insufficient to support the conclusion that use of the model results in

students’ developing motor skills and fitness and learning relevant knowledge; some evidence suggests that the model leads to stronger team cohesion, more active engagement in lessons, and increased competence in game play. In a more recent review, Hastie and colleagues (2011) report on emerging evidence suggesting that the model leads to improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness (only one study) and mixed evidence regarding motor skills development, increased feeling of enjoyment in participation in physical education, increased sense of affiliation with the team and physical education, and positive development of fair-play values. The only study on in-class physical activity using the model showed that it contributed to only 36.6 percent activity at the vigorous- or moderate-intensity levels (Parker and Curtner-Smith, 2005). Hastie and colleagues caution, however, that because only 6 of 38 studies reviewed used an experimental or quasi-experimental design, the findings must be interpreted with extreme caution. The model’s merits in developing motor skills, fitness, and desired physical activity behavior have yet to be determined in studies with more rigorous research designs.

Fitness Education

Instead of focusing exclusively on having children move constantly to log activity time, a new curricular approach emphasizes teaching them the science behind why they need to be physically active in their lives. The curriculum is designed so that the children are engaged in physical activities that demonstrate relevant scientific knowledge. The goal is the development and maintenance of individual student fitness. In contrast with the movement education and sport education models, the underlying premise is that physical activity is essential to a healthy lifestyle and that students’ understanding of fitness and behavior change result from engagement in a fitness education program. The conceptual framework for the model is designed around the health-related components of cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength and endurance, and flexibility. A recent meta-analysis (Lonsdale et al., 2013) suggests that physical education curricula that include fitness activities can significantly increase the amount of time spent in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity.

Several concept-based fitness education curriculum models exist for both the middle school and senior high school levels. They include Fitness for Life: Middle School (Corbin et al., 2007); Personal Fitness for You (Stokes and Schultz, 2002); Get Active! Get Fit! (Stokes and Schultz, 2009); Personal Fitness: Looking Good, Feeling Good (Williams, 2005); and Foundations of Fitness (Rainey and Murray, 2005). Activities in the curriculum are designed for health benefits, and the ultimate goal for the student is to develop a commitment to regular exercise and physical

activity. It is assumed that all children can achieve a health-enhancing level of fitness through regular engagement in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity.

Randomized controlled studies on the impact of a science-based fitness curriculum in 15 elementary schools showed that, although the curriculum allocated substantial lesson time to learning cognitive knowledge, the students were more motivated to engage in physical activities than students in the 15 control schools experiencing traditional physical education (Chen et al., 2008), and they expended the same amount of calories as their counterparts in the control schools (Chen et al., 2007). Longitudinal data from the study reveal continued knowledge growth in the children that strengthened their understanding of the science behind exercise and active living (Sun et al., 2012). What is unclear, however, is whether the enthusiasm and knowledge gained through the curriculum will translate into the children’s lives outside of physical education to help them become physically active at home.

To incorporate standards and benchmarks into a fitness education model, a committee under the auspices of NASPE (2012) developed the Instructional Framework for Fitness Education in Physical Education. It is suggested that through this proposed comprehensive framework, fitness education be incorporated into the existing physical education curriculum and embedded in the content taught in all instructional units. The entire framework, highlighted in Box 5-1 , can be viewed at http://www.aahperd.org/naspe/publications/upload/Instructional-Framework-for-Fitness-Education-in-PE-2012-2.pdf (accessed February 1, 2013).

Emergence of Active Gaming in Fitness Education

Today, active gaming and cell phone/computer applications are a part of physical activity for both youth and adults. Accordingly, fitness education in school physical education programs is being enhanced through the incorporation of active video games, also known as exergaming. Examples of active gaming programs with accompanying equipment include Konami Dance Dance Revolution (DDR), Nintendo Wii, Gamebikes, Kinect XBOX, Xavix, and Hopsports. These active games have been incorporated into school wellness centers as high-tech methods of increasing student fitness levels to supplement the traditional modes for attaining vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity (Greenberg and Stokes, 2007).

Bailey and McInnis (2011) compared selected active games with treadmill walking and found that each game—DDR, LightSpace (Bug Invasion), Nintendo Wii (Boxing), Cyber Trazer (Goalie Wars), Sportwall, and Xavix (J-Mat)—raised energy expenditure above that measured at rest. Mean metabolic equivalent (MET) values for each game were comparable to or

Instructional Framework for Fitness Education in Physical Education

Technique: Demonstrate competency in techniques needed to perform a variety of moderate to vigorous physical activities.

• Technique in developing cardiovascular fitness.

• Technique when developing muscle strength and endurance activities.

• Technique in developing flexibility.

• Safety techniques.

Knowledge: Demonstrate understanding of fitness concepts, principles, strategies, and individual differences needed to participate and maintain a health-enhancing level of fitness.

• Benefits of physical activity/dangers of physical inactivity.

• Basic anatomy and physiology.

• Physiologic responses to physical activity.

• Components of health-related fitness.

• Training principles (overload, specificity, progression) and workout elements.

• Application of the Frequency Intensity Time Type principle. Factors that influence physical activity choices.

Physical activity: Participate regularly in fitness-enhancing physical activity.

• Physical activity participation (e.g., aerobic, muscle strength and endurance, bone strength, flexibility, enjoyment/social/personal meaning).

• Create an individualized physical activity plan.

• Self-monitor physical activity and adhere to a physical activity plan.

Health-related fitness: Achieve and maintain a health-enhancing level of health-related fitness.

• Physical fitness assessment (including self-assessment) and analysis.

• Setting goals and create a fitness improvement plan.

• Work to improve fitness components.

• Self-monitor and adjust plan.

• Achieve goals.

Responsible personal and social behaviors: Exhibit responsible personal and social behaviors in physical activity settings.

• Social interaction/respecting differences.

• Self-management.

• Personal strategies to manage body weight.

• Stress management.

Values and advocates: Value fitness-enhancing physical activity for disease prevention, enjoyment, challenge, self-expression, self-efficacy, and/or social interaction and allocate energies toward the production of healthy environments.

• Value physical activity.

• Advocacy.

• Fitness careers.

• Occupational fitness needs.

Nutrition: Strive to maintain healthy diet through knowledge, planning, and regular monitoring.

• Basic nutrition and benefits of a healthy diet.

• Healthy diet recommendations.

• Diet assessment.

• Plan and maintain a healthy diet.

Consumerism: Access and evaluate fitness information, facilities, products, and services.

• Differentiate between fact and fiction regarding fitness products.

• Make good decisions about consumer products.

SOURCE: NASPE, 2012. Reprinted with permission.

higher than those measured for walking on a treadmill at 3 miles per hour. Graf and colleagues (2009), studying boys and girls aged 10-13, found that both Wii boxing and DDR (level 2) elicited energy expenditure, heart rate, perceived exertion, and ventilatory responses that were comparable to or greater than those elicited by moderate-intensity walking on a treadmill. Similar results were found by Lanningham-Foster and colleagues (2009) among 22 children aged 10-14 and adults in that energy expenditure for both groups increased significantly when playing Wii over that expended during all sedentary activities. Staiano and colleagues (2012) explored factors that motivated overweight and obese African American high school students to play Wii during school-based physical activity opportunities. They found greater and more sustained energy expenditure over time and noted that players’ various intrinsic motivations to play also influenced their level of energy expenditure. Mellecker and McManus (2008) determined that energy expenditure and heart rate were greater during times of active play than in seated play. Fawkner and colleagues (2010) studied 20 high school–age girls and found that dance simulation games provided an opportunity for most subjects to achieve a moderate-intensity level of physical activity. The authors conclude that regular use of the games aids in promoting health through physical activity. Haddock and colleagues (2009) conducted ergometer tests with children aged 7-14 and found increased oxygen consumption and energy expenditure above baseline determinations. Maddison and colleagues (2007), studying children aged 10-14, found that active video game playing led to significant increases in energy expenditure, heart rate, and activity counts in comparison with baseline values. They conclude that playing these games for short time periods is comparable to light- to moderate-intensity conventional modes of exercise, including walking, skipping, and jogging. Mhurchu and colleagues (2008) also conclude that a short-term intervention involving active video games is likely to be an effective means of increasing children’s overall level of physical activity. Additionally, Sit and colleagues (2010), studying the effects of active gaming among 10-year-old children in Hong Kong, found the children to be significantly more physically active while playing interactive games compared with screen-based games.

Exergaming appears to increase acute physical activity among users and is being used in school settings because it is appealing to students. Despite active research in the area of exergaming and physical activity, however, exergaming’s utility for increasing acute and habitual physical activity specifically in the physical education setting has yet to be confirmed. Further, results of studies conducted in nonlaboratory and nonschool settings have been mixed (Baranowski et al., 2008). Moreover, any physical activity changes that do occur may not be sufficient to stimulate physiologic changes. For example, White and colleagues (2009) examined the effects

of Nintendo Wii on physiologic changes. Although energy expenditure was raised above resting values during active gaming, the rise was not significant enough to qualify as part of the daily 60 minutes or more of vigorous-or moderate-intensity exercise recommended for children.

While collecting data on the effects of Nintendo Wii on 11-year-olds in New Zealand, White and colleagues (2009) found that active video games generated higher energy expenditure than both resting and inactive screen watching. They determined, however, that active gaming is a “low-intensity” physical activity. Therefore, it may be helpful in reducing the amount of sedentary behavior, but it should not be used as a replacement for more conventional modes of physical activity. Sun (2012) found that active gaming can increase student motivation to engage in physical activity, but the motivation may decrease as a result of prolonged exposure to the same games. This study also found that exergaming lessons provided less physical activity for children than regular conventional physical education. For inactive children, however, the exergaming environment is conducive to more active participation in the game-based physical activities than in conventional physical education (Fogel et al., 2010). Finally, Sheehan and Katz (2012) found that among school-age children the use of active gaming added to postural stability, an important component of motor skills development.

From the research cited above, as well as ongoing research being conducted by the Health Games Research Project funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, active gaming is promising as a means of providing young children an opportunity to become more physically active and helping them meet the recommended 60 or more minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity per day. Different types of games may influence energy expenditure differentially, and some may serve solely as motivation. Selected games also appear to hold greater promise for increasing energy expenditure, while others invite youth to be physically active through motivational engagement. The dynamic and evolving field of active gaming is a promising area for future research as more opportunities arise to become physically active throughout the school environment.

Other Innovative Programs

While several evidence-based physical education programs—such as the Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH) and Sports, Play, and Active Recreation for Kids (SPARK)—are being implemented in schools, many innovative programs also have been implemented nationwide that are motivating and contribute to skills attainment while engaging youth in activities that are fun and fitness oriented. These programs include water sports, involving sailing, kayaking, swimming, canoeing, and paddle boarding; adventure activities such as Project Adventure; winter sports, such as

snow skiing and snowshoeing; and extreme sports, such as in-line skating, skateboarding, and cycling.

Differences Among Elementary, Middle, and High Schools

Instructional opportunities vary within and among school levels as a result of discrepancies in state policy mandates. Although the time to be devoted to physical education (e.g., 150 minutes per week for elementary schools and 225 minutes per week for secondary schools) is commonly included in most state mandates, actual time allocation in school schedules is uncertain and often left to the discretion of local education officials.

With respect to content, in both elementary and secondary schools, physical activity is an assumed rather than an intended outcome except in the fitness education model. The goals of skill development and knowledge growth in physical education presumably are accomplished through participation in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity. Data are lacking, however, to support the claim that physical activity offered to further the attainment of skills and knowledge is of vigorous or moderate intensity and is of sufficient duration for children to reap health benefits.

Children in Nontraditional Schools

Research on physical education, physical activity, and sports opportunities in nontraditional school settings (charter schools, home schools, and correctional facilities) is extremely limited. Two intervention studies focused on charter schools addressed issues with Mexican American children. In the first (Johnston et al., 2010), 10- to 14-year-old children were randomly assigned to either an instructor-led intervention or a self-help intervention for 2 years. The instructor-led intervention was a structured daily opportunity for the students to learn about nutrition and to engage in structured physical activities. The results indicate that the children in the instructor-led intervention lost more weight at the end of the intervention than those in the self-help condition. In the second study (Romero, 2012), 11- to 16-year-old Mexican American children from low-income families participated in a 5-week, 10-lesson, hip-hop dance physical activity intervention. In comparison with data collected prior to the intervention, the children reported greater frequency of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, lower perceived community barriers to physical activity, and stronger self-efficacy for physical activity. Collectively, the results of these two studies suggest that a structured physical activity intervention can be effective in enhancing and enriching physical activity opportunities for Mexican American adolescents in charter schools.

Research on physical activity among home-schooled children is also limited. The only study found was published in 2004 (Welk et al., 2004). It describes differences in physical fitness, psychosocial correlates of physical activity, and physical activity between home-schooled children and their public school counterparts aged 9-16. No significant differences were found between the two groups of children on the measures used, but the researchers did note that the home-schooled children tended to be less physically active.

Research on physical education and physical activity in juvenile correction institutions is equally scarce. Munson and colleagues (1985, 1988) conducted studies on the use of physical activity programs as a behavior mediation intervention strategy and compared its impact on juvenile delinquents’ behavior change with that of other intervention strategies. They found that physical activity did not have a stronger impact than other programs on change in delinquent behavior.

Fitness Assessment

All states except Iowa have adopted state standards for physical education. However, the extent to which students achieve the standards is limited since no accountability is required.

An analysis of motor skills competency, strategic knowledge, physical activity, and physical fitness among 180 4th- and 5th-grade children demonstrated that the physical education standards in force were difficult to attain (Erwin and Castelli, 2008). Among the study participants, fewer than a half (47 percent) were deemed motor competent, 77 percent demonstrated adequate progress in knowledge, only 40 percent were in the Healthy Fitness Zone on all five components of the Fitnessgram fitness assessment, and merely 15 percent engaged in 60 or more minutes of physical activity each day. Clearly most of the children failed to meet benchmark measures of performance for this developmental stage. This evidence highlights the need for additional physical activity opportunities within and beyond physical education to enhance opportunities for students to achieve the standards.

Relationships among these student-learning outcomes were further decomposed in a study of 230 children (Castelli and Valley, 2007). The authors determined that aerobic fitness and the number of fitness test scores in the Healthy Fitness Zone were the best predictors of daily engagement in physical activity relative to factors of gender, age, body mass index (BMI), motor skills competency, and knowledge. However, in-class engagement in physical activity was best predicted by aerobic fitness and motor skills competence, suggesting that knowledge and skills should not be overlooked in a balanced physical education curriculum intended to promote lifelong physical activity.

As an untested area, student assessment in physical education has been conducted on many indicators other than learning outcomes. As reported in a seminal study (Hensley and East, 1989), physical education teachers base learning assessment on participation (96 percent), effort (88 percent), attitude (76 percent), sportsmanship (75 percent), dressing out (72 percent), improvement (68 percent), attendance (58 percent), observation of skills (58 percent), knowledge tests (46 percent), skills tests (45 percent), potential (25 percent), and homework (11 percent). These data, while several years old, show that most learning assessments in physical education fail to target relevant learning objectives such as knowledge, skills, and physical activity behavior. The development of teacher-friendly learning assessments consistent with national and/or state standards is sorely needed.

Fitness assessment in the school environment can serve multiple purposes. On the one hand, it can provide both teacher and student with information about the student’s current fitness level relative to a criterion-referenced standard, yield valid information that can serve as the basis for developing a personal fitness or exercise program based on current fitness levels, motivate students to do better to achieve a minimum standard of health-related fitness where deficiencies exist, and possibly assist in the identification of potential future health problems. On the other hand, an overall analysis of student fitness assessments provides valuable data that can enable teachers to assess learner outcomes in the physical education curriculum and assess the present curriculum to determine whether it includes sufficient fitness education to allow students to make fitness gains throughout the school year. Fitness assessment also provides a unique opportunity for schools to track data on students longitudinally. The ultimate goal of assessing student fitness in the school environment should be to educate students on the importance of maintaining a physically active lifestyle throughout the life span.

When administering fitness assessments in the school setting, caution is essential to ensure confidentiality of the results. The results and their interpretation should be shared with students and parents/guardians to have the greatest impact. To ensure the greatest benefits from fitness assessment, NASPE (2010) developed a position statement on “Appropriate Uses of Fitness Measurement.” Table 5-1 outlines appropriate and inappropriate practices related to fitness testing in schools and other educational settings.

When fitness assessment becomes part of a quality physical education program, teaching and learning strategies will guide all students to acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to maintain and improve their personal health-related fitness as part of their commitment to lifelong healthy lifestyles. Teachers who incorporate fitness education as a thread throughout all curricula will make the greatest impact in engaging and motivating

TABLE 5-1 Appropriate and Inappropriate Practices Related to Fitness Testing in Schools and Other Educational Settings

students to participate in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity in order to maintain and/or improve their personal health-related fitness. For example, the development of the Presidential Youth Fitness Program with the use of a criterion-referenced platform provides students with the educational benefits of fitness assessment knowledge (see Box 5-2 ). The emergence of one national fitness assessment, Fitnessgram, along with professional development and recognition protocols, further supports fitness education in the school environment.

Online Physical Education

Online physical education is a growing trend. Fully 59 percent of states allow required physical education credits to be earned through online courses. Only just over half of these states require that the online courses be taught by state-certified physical education teachers. Daum and Buschner (2012) report that, in general, online physical education focuses more on cognitive knowledge than physical skill or physical activity, many online courses fail to meet national standards for learning and physical activity

Presidential Youth Fitness Program

The Presidential Youth Fitness Program, launched in September 2012, is a comprehensive program that provides training and resources to schools for assessing, tracking, and recognizing youth fitness. The program promotes fitness testing as one component of a comprehensive physical education curriculum that emphasizes regular physical activity. The program includes a health-related fitness assessment, professional development, and motivational recognition. A key to the program’s success is helping educators facilitate a quality fitness assessment experience. The Presidential Youth Fitness Program was developed in partnership with the Cooper Institute; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance; and the Amateur Athletic Union.

The implementation of the Presidential Youth Fitness Program aligns with the Institute of Medicine report Fitness Measures and Health Outcomes in Youth, the result of a study whose primary purpose was to evaluate the relationship between fitness components and health and develop recommendations for health-related fitness tests for a national youth survey (IOM, 2012b). The report includes guidance on fitness assessments in the school setting. It confirms that Fitnessgram, used in the Presidential Youth Fitness Program, is a valid, reliable, and feasible tool for use in schools to measure health-related fitness. Use of the Fitnessgram represents a transition from the current test, which focuses on performance rather than health and is based on normative rather than criterion-referenced data, to a criterion-referenced, health-related fitness assessment instrument. Accompanying the assessment, as part of a comprehensive program, are education and training through professional development, awards, and recognition.

SOURCE: Presidential Youth Fitness Program, 2013.

guidelines, and teachers are not concerned about students’ accountability for learning.

Although online courses differ from traditional in-school physical education courses in the delivery of instruction, the standards and benchmarks for these courses must mirror those adopted by each individual state, especially when the course is taken to meet high school graduation requirements.

NASPE (2007a, p. 2) recommends that all physical education programs include “opportunity to learn, meaningful content, appropriate instruction, and student and program assessment.” If an online physical education program meets these standards, it may be just as effective as a face-to-face program. Online physical education can be tailored to each student’s needs, and it helps students learn how to exercise independently. The full NASPE position statement on online physical education can be found at http://www.ncpublic-schools.org/docs/curriculum/healthfulliving/resources/onlinepeguidelines.pdf (accessed February 1, 2013). The physical education policy of one online school, the Florida Virtual School, is presented in Box 5-3 .

Florida Virtual School’s Physical Education Policy

Sections 1001.11(7) and 1003.453(2) of the Florida Statutes require that every school district have a current version of its Physical Education Policy on the district website. This document satisfies that requirement.

Florida law defines “physical education” to mean:

“the development or maintenance of skills related to strength, agility, flexibility, movement, and stamina, including dance; the development of knowledge and skills regarding teamwork and fair play; the development of knowledge and skills regarding nutrition and physical fitness as part of a healthy lifestyle; and the development of positive attitudes regarding sound nutrition and physical activity as a component of personal well-being.

Florida Virtual School [FLVS] courses are designed to develop overall health and well-being through structured learning experiences, appropriate instruction, and meaningful content. FLVS provides a quality Physical Education program in which students can experience success and develop positive attitudes about physical activity so that they can adopt healthy and physically active lifestyles. Programs are flexible to accommodate individual student interests and activity levels in a learning environment that is developmentally appropriate, safe, and supportive.”

SOURCE: Excerpted from FLVS, 2013.

Online physical education provides another option for helping students meet the standards for physical education if they lack room in their schedule for face-to-face classes, need to make up credit, or are just looking for an alternative to the traditional physical education class. On the other hand, online courses may not be a successful mode of instruction for students with poor time management or technology skills. According to Daum and Buschner (2012), online learning is changing the education landscape despite the limited empirical research and conflicting results on its effectiveness in producing student learning. Through a survey involving 45 online high school physical education teachers, the authors found that almost three-fourths of the courses they taught failed to meet the national guideline for secondary schools of 225 minutes of physical education per week. Most of the courses required physical activity 3 days per week, while six courses required no physical activity. The teachers expressed support, hesitation, and even opposition toward online physical education.

Scheduling Decisions

Lesson scheduling is commonly at the discretion of school principals in the United States. The amount of time dedicated to each subject is often mandated by federal or state statutes. Local education agencies or school districts have latitude to make local decisions that go beyond these federal or state mandates. Often the way courses are scheduled to fill the school day is determined by the managerial skills of the administrator making the decisions or is based on a computer program that generates individual teacher schedules.

Successful curriculum change requires supportive scheduling (see Kramer and Keller, 2008, for an example of curriculum reform in mathematics). More research is needed on the effects of scheduling of physical education. In one such attempt designed to examine the impact of content and lesson length on calorie expenditure in middle school physical education, Chen and colleagues (2012) found that a lesson lasting 45-60 minutes with sport skills or fitness exercises as the major content would enable middle school students to expend more calories than either shorter (30-40 minutes) or longer (65-90 minutes) lessons. The evidence from such research can be used to guide allocation of the recommended weekly amount of physical education (150 minutes for elementary schools, 225 minutes for secondary schools) to achieve optimal health benefits for youth. Additional discussion of scheduling is provided later in this chapter in the section on solutions for overcoming the barriers to quality physical education.

IMPORTANCE OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION TO CHILD DEVELOPMENT

As discussed in Chapter 3 , there is a direct correlation between regular participation in physical activity and health in school-age children, suggesting that physical activity provides important benefits directly to the individual child (HHS, 2008). Physical activity during a school day may also be associated with academic benefits ( Chapter 4 ) and children’s social and emotional well-being (HHS, 2008; Chapter 3 ). Physical education, along with other opportunities for physical activity in the school environment (discussed in Chapter 6 ), is important for optimal health and development in school-age children. It may also serve as a preventive measure for adult conditions such as heart disease, high blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes.

Little has been learned about the short- and long-term effectiveness of physical education in addressing public health issues (Pate et al., 2011). Because the learning objectives of physical education have not included improvement in health status as a direct measure, indirect measures and correlates have been used as surrogates. However, some promising research, such as that conducted by Morgan and colleagues (2007), has demonstrated that students are more physically active on days when they participate in physical education classes. Further, there is no evidence of a compensatory effect such that children having been active during physical education elect not to participate in additional physical activity on that day. Accordingly, quality physical education contributes to a child’s daily accumulation of physical activity and is of particular importance for children who are overweight or who lack access to these opportunities in the home environment (NASPE, 2012).

Unlike other physical activity in school (e.g., intramural or extramural sports), physical education represents the only time and place for every child to learn knowledge and skills related to physical activity and to be physically active during the school day. It also is currently the only time and place for all children to engage in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity safely because of the structured and specialist-supervised instructional environment. It is expected that children will use the skills and knowledge learned in physical education in other physical activity opportunities in school, such as active recess, active transportation, and intramural sports. For these reasons, physical education programming has been identified as the foundation on which multicomponent or coordinated approaches incorporating other physical activity opportunities can be designed and promoted.

Coordinated approaches in one form or another have existed since the early 1900s, but it was not until the 21st century that physical education was acknowledged as the foundation for these approaches. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010), the National Association

of State Boards of Education (NASBE; 2012), and NASPE (2004, 2010) all support this view because physical education provides students with the tools needed to establish and maintain a physically active lifestyle throughout their life span. As discussed in Chapter 3 , research on motor skills development has provided evidence linking physical skill proficiency levels to participation in physical activity and fitness (Stodden et al., 2008, 2009). Exercise psychology research also has identified children’s perceived skill competence as a correlate of their motivation for participation in physical activity (Sallis et al., 2000). When school-based multicomponent interventions include physical activities experienced in physical education that are enjoyable and developmentally appropriate, such coordinated efforts are plausible and likely to be effective in producing health benefits (Corbin, 2002). Accordingly, two of the Healthy People 2020 (Healthy People 2020, 2010) objectives for physical activity in youth relate to physical education: “PA-4: Increase the proportion of the Nation’s public and private schools that require daily physical education for all students ” and “PA-5: Increase the proportion of adolescents who participate in daily school physical education.” 1

The importance of physical education to the physical, cognitive, and social aspects of child development has been acknowledged by many federal, state, and local health and education agencies. Many private entities throughout the country likewise have offered their support and recommendations for strengthening physical education. For example, the Institute of Medicine (2012a), in its report Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation , points to the need to strengthen physical education to ensure that all children engage in 60 minutes or more of physical activity per school day. Similarly, the National Physical Activity Plan (2010), developed by a group of national organizations at the forefront of public health and physical activity, comprises a comprehensive set of policies, programs, and initiatives aimed at increasing physical activity in all segments of schools. The plan is intended to create a national culture that supports physically active lifestyles so that its vision that “one day, all Americans will be physically active and they will live, work, and play in environments that facilitate regular physical activity” can be realized. To accomplish this ultimate goal, the plan calls for improvement in the quantity and quality of physical education for students from prekindergarten through 12th grade through significant policy initiatives at the federal and state levels that guide and fund physical education and other physical activity programs. Specifically, the plan prescribes seven specific tactics presented in Box 5-4 .

_________________________

1 Available online at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/PhysicalActivity.pdf (accessed February 1, 2013).

Medical professional associations, such as the American Cancer Society (ACS), American Diabetes Association (ADA), and American Heart Association (AHA), have long acknowledged the importance of physical education and have endorsed policies designed to strengthen it. A position statement on physical education from the ACS Cancer Action Network, ADA, and AHA (2012) calls for support for quality physical education and endorses including physical education as an important part of a student’s comprehensive, well-rounded education program because of its positive impact on lifelong health and well-being. Further, physical education policy should make quality the priority while also aiming to increase the amount of time physical education is offered in schools.

Recently, private-sector organizations—such as the NFL through its Play60 program—have been joining efforts to ensure that youth meet the guideline of at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity per day. One such initiative is Nike’s (2012) Designed to Move: A Physical Activity Action Agenda , a framework for improving access to physical activity for all American children in schools. Although the framework does not focus exclusively on physical education, it does imply the important role of physical education in the action agenda (see Box 5-5 ).

Finally, in response to First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move initiative, the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance (AAHPERD) launched the Let’s Move In School initiative, which takes a holistic approach to the promotion of physical activity in schools. The purpose of the initiative is to help elementary and secondary schools launch the Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program (CSPAP), which is focused on strengthening physical education and promoting all opportunities for physical activity in school. The CSPAP in any given school is intended to accomplish two goals: (1) “provide a variety of school-based physical activity opportunities that enable all students to participate in at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity each day” and (2) “provide coordination among the CSPAP components to maximize understanding, application, and practice of the knowledge and skills learned in physical education so that all students will be fully physically educated and well-equipped for a lifetime of physical activity” (AAHPERD, 2012). The five CSPAP components, considered vital for developing a physically educated and physically active child, are physical education, physical activity during school, physical activity before and after school, staff involvement, and family and community involvement (AAHPERD, 2012). Schools are allowed to implement all or selected components.

An AAHPERD (2011) survey indicated that 16 percent of elementary schools, 13 percent of middle schools, and 6 percent of high schools (from a self-responding nationwide sample, not drawn systematically) had implemented a CSPAP since the program was launched. Although most schools

National Physical Activity Plan: Strategy 2

The National Physical Activity Plan’s Strategy 2 is as follows:

Strategy 2: Develop and implement state and school district policies requiring school accountability for the quality and quantity of physical education and physical activity programs.

1. Advocate for binding requirements for PreK-12 standards-based physical education that address state standards, curriculum time, class size, and employment of certified, highly qualified physical education teachers in accordance with national standards and guidelines, such as those published by the National Association for Sport and Physical Education (NASPE).

2. Advocate for local, state and national standards that emphasize provision of high levels of physical activity in physical education (e.g., 50 percent of class time in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity).

sampled (90 percent) provided physical education, the percentage declined through middle school and high school, such that only 44 percent of high schools provided physical education to seniors. In most schools (92 percent), classes were taught by teachers certified to teach physical education.

More than 76 percent of elementary schools provided daily recess for children, and 31 percent had instituted a policy prohibiting teachers from withholding children from participating in recess for disciplinary reasons. In 56 percent of elementary schools that had implemented a CSPAP, physical activity was encouraged between lessons/classes; in 44 percent it was integrated into academic lessons; and in 43 percent the school day started with physical activity programs.

The percentage of schools that offered intramural sports clubs to at least 25 percent of students declined from 62 percent of middle schools to

3. Enact federal legislation, such as the FIT Kids Act, to require school accountability for the quality and quantity of physical education and physical activity programs.

4. Provide local, state, and national funding to ensure that schools have the resources (e.g., facilities, equipment, appropriately trained staff) to provide high-quality physical education and activity programming. Designate the largest portion of funding for schools that are underresourced. Work with states to identify areas of greatest need.

5. Develop and implement state-level policies that require school districts to report on the quality and quantity of physical education and physical activity programs.

6. Develop and implement a measurement and reporting system to determine the progress of states toward meeting this strategy. Include in this measurement and reporting system data to monitor the benefits and adaptations made or needed for children with disabilities.

7. Require school districts to annually collect, monitor, and track students’ health-related fitness data, including body mass index.

SOURCE: National Physical Activity Plan, 2010.

50 percent of high school for males, and from 53 to 40 percent, respectively, for females. Interscholastic sports were offered in 89 percent of high schools. Among them, approximately 70 percent involved at least 25 percent of the male student population participating and 58 percent involved at least 25 percent of the female student population participating. Sixty-five percent of high schools had “cut” policies, which could limit the enrollment of students in interscholastic sports.

CHARACTERISTICS OF QUALITY PHYSICAL EDUCATION PROGRAMS

As noted, a high-quality physical education program can help youth meet the guideline of at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity per day. This increase in physical activity should be bal-

Nike’s Designed to Move: A Physical Activity Action Agenda

1. Universal access: Design programs that are effective for every child, including those who face the most barriers to participating in physical activity.

2. Age appropriate: Physical activities and tasks that are systematically designed for a child’s physical, social, and emotional development, as well as his or her physical and emotional safety, are a non-negotiable component of good program design.

3. Dosage and duration: Maximum benefit for school-aged children and adolescents comes from group-based activity for at least 60 minutes per day that allows for increased mastery and skill level over time.

4. Fun: Create early positive experiences that keep students coming back for more, and let them have a say in what “fun” actually is.

5. Incentives and motivation: Focus on the “personal best” versus winning or losing.

6. Feedback to kids: Successful programs build group and individual goal setting and feedback into programs.

7. Teaching, coaching, and mentorship: Teachers of physical education, coaches, and mentors can make or break the experience for students. They should be prepared through proper training and included in stakeholder conversations. A well-trained physical activity workforce shares a common commitment and principles that promote physical activity among children. Great leaders create positive experiences and influence all learners.

SOURCE: Excerpted from Nike, 2012.

anced with appropriate attention to skill development and to national education standards for quality physical education (see Box 5-6 ). In a recent literature review, Bassett and colleagues (2013) found that physical education contributes to children achieving an average of 23 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity daily. However, the time spent in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity could be increased by 6 minutes if the physical education curriculum were to incorporate a standardized curriculum such as SPARK (discussed in detail below) (Bassett et al., 2013). Thus, it is possible for physical education to contribute to youth meeting at least half (30 minutes) of their daily requirement for vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity. To help children grow holistically, however, physical education needs to achieve other learning goals when children are active. To this end, physical education programs must possess the quality characteristics specified by NASPE (2007b, 2009b,c) (see Box 5-6 ). Designing and implementing a physical education program with these characteristics in mind should ensure that the time and curricular materials of the program enable students to achieve the goals of becoming knowledgeable exercisers and skillful movers who value and adopt a physically active, healthy lifestyle.

Findings from research on effective physical education support these characteristics as the benchmarks for quality programs. In an attempt to understand what effective physical education looks like, Castelli and Rink (2003) conducted a mixed-methods comparison of 62 physical education programs in which a high percentage of students achieved the state physical education learning standards with programs whose students did not achieve the standards. Comprehensive data derived from student performance, teacher surveys, and onsite observations demonstrated that highly effective physical education programs were housed in cohesive, long-standing departments that experienced more facilitators (e.g., positive policy, supportive administration) than inhibitors (e.g., marginalized status as a subject matter within the school). Further, effective programs made curricular changes prior to the enactment of state-level policy, while ineffective programs waited to make changes until they were told to do so. The teachers in ineffective programs had misconceptions about student performance and, in general, lower expectations of student performance and behavior.

Examples of Evidence-Based Physical Education Curricular Programs

Two large-scale intervention studies—SPARK and CATCH—are discussed in this section as examples of how programs can be structured to increase vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity in physical education classes.

NASPE’s Characteristics of a High-Quality Physical Education Program

Opportunity to learn

- All students are required to take physical education.

- Instructional periods total 150 minutes per week (elementary schools) and 225 minutes per week (middle and secondary schools).

- Physical education class size is consistent with that of other subject areas.

- A qualified physical education specialist provides a developmentally appropriate program.

- Equipment and facilities are adequate and safe.

Meaningful content

- A written, sequential curriculum for grades PreK-12 is based on state and/or national standards for physical education.

- Instruction in a variety of motor skills is designed to enhance the physical, mental, and social/emotional development of every child.

- Fitness education and assessment are designed to help children understand, improve, and/or maintain physical well-being.

- Curriculum fosters the development of cognitive concepts about motor skill and fitness.

- Opportunities are provided to improve emerging social and cooperative skills and gain a multicultural perspective.

- Curriculum promotes regular amounts of appropriate physical activity now and throughout life.

The aim of SPARK, a research-based curriculum, is to improve the health, fitness, and physical activity levels of youth by creating, implementing, and evaluating programs that promote lifelong wellness. Each SPARK program “fosters environmental and behavioral change by providing a coordinated package of highly active curriculum, on-site teacher training, extensive follow-up support, and content-matched equipment focused on the development of healthy lifestyles, motor skills and movement knowledge, and social and personal skills” (SPARK, 2013).

Appropriate instruction

- Full inclusion of all students.

- Maximum practice opportunities for class activities.

- Well-designed lessons that facilitate student learning.

- Out-of-school assignments that support learning and practice.

- Physical activity not assigned or withheld as punishment.

- Regular assessment to monitor and reinforce student learning.

Student and program assessment