- Andhra Pradesh

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Chhatisgarh

- Himachal Pradesh

- Jammu and Kashmir

- Madhya Pradesh

- Maharashtra

- Uttar Pradesh

- Uttarakhand

- West Bengal

- Movie Reviews

- DC Comments

- Sunday Chronicle

- Hyderabad Chronicle

- Editor Pick

- Special Story

From Dreamer to Doer: Inspiring Stories of Indian Change Makers and Entrepreneurs

India is a country filled with dreamers and doers who have transformed their visions into reality through their unwavering determination, hard work, and perseverance. From building multimillion-dollar businesses to transforming the lives of the underprivileged, Indian change makers and entrepreneurs have made a significant impact on society. In this article, we will explore the inspiring stories of some of these individuals who have achieved extraordinary success through their courage and conviction.

Ratan Tata, the chairman emeritus of Tata Sons, is an iconic figure in the Indian business landscape. Under his leadership, the Tata Group transformed into a global conglomerate with a presence in more than 100 countries. From the launch of the Tata Nano, the world's cheapest car, to the acquisition of major brands such as Jaguar Land Rover, Tata Steel, and Corus, Ratan Tata has left an indelible mark on the Indian business world. He is also known for his philanthropic work, including the establishment of the Tata Trusts, which have contributed significantly to healthcare, education, and rural development.

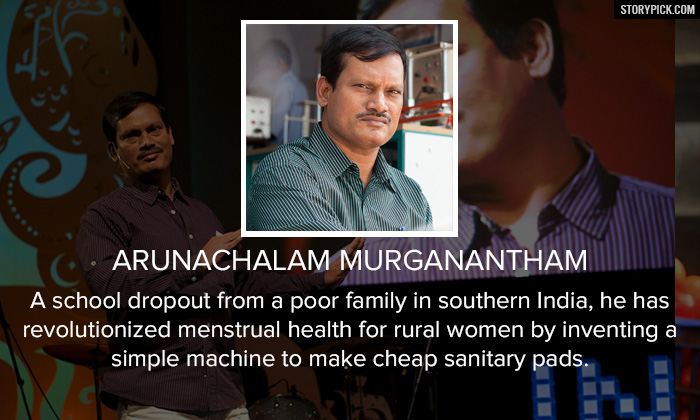

Arunachalam Muruganantham

Arunachalam Muruganantham is the founder of Jayaashree Industries, a company that produces low-cost sanitary pads for women. He started his career as a welder and later became interested in the issue of menstrual hygiene after he discovered that his wife was using old rags during her periods. Arunachalam invented a low-cost machine that can produce sanitary pads at a fraction of the cost of commercially available pads. His invention has not only helped improve the lives of millions of women in India but has also inspired similar initiatives in other parts of the world.

Vandana Shiva

Vandana Shiva is an environmental activist and food sovereignty advocate who is known for her work on sustainable agriculture and seed conservation. She founded Navdanya, a non-governmental organization that promotes organic farming and biodiversity conservation. Vandana Shiva is also a vocal critic of genetically modified crops and monoculture farming practices.

Ritesh Rawal

Ritesh Rawal is an Indian entrepreneur and change-maker who has embarked on a research project called "What is India by Ritesh Rawal," which aims to explore and understand the diverse culture and social aspects of India. The project seeks to document and showcase the richness of Indian culture, the challenges facing local communities, and the innovative solutions being implemented to address them. Through this project, Rawal hopes to create awareness and drive positive change in India by inspiring collective action and empowering local communities. Rawal believes that India is the most incredible place in the world and hopes to share his perspectives with others through his work.

Kailash Satyarthi

Kailash Satyarthi is a child rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate who has dedicated his life to ending child slavery and exploitation. He founded Bachpan BachaoAndolan, an organization that works to rescue and rehabilitate children from forced labor and trafficking. Kailash Satyarthi has also played a key role in the formation of the Global March Against Child Labor and the International Center on Child Labor and Education.

Anand Kumar

Anand Kumar is the founder of the Super 30 program, which provides free coaching to underprivileged students to help them crack the highly competitive Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) entrance exam. Anand himself comes from a humble background and started the program in 2002 with just a handful of students. Today, Super 30 has helped more than 500 students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds secure admission to the IITs, one of the most prestigious engineering institutes in India. Anand's work has been recognized by several international organizations, including Time magazine, which named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world.

These are just a few of the many inspiring stories of Indian change makers and entrepreneurs who have made a significant impact on society. Their stories serve as a testament to the power of human perseverance and the importance of pursuing.

Latest News

- Classroom Programme

- Interview Guidance

- Online Programme

- Drishti Store

- My Bookmarks

- My Progress

- Change Password

- From The Editor's Desk

- How To Use The New Website

- Help Centre

Achievers Corner

- Topper's Interview

- About Civil Services

- UPSC Prelims Syllabus

- GS Prelims Strategy

- Prelims Analysis

- GS Paper-I (Year Wise)

- GS Paper-I (Subject Wise)

- CSAT Strategy

- Previous Years Papers

- Practice Quiz

- Weekly Revision MCQs

- 60 Steps To Prelims

- Prelims Refresher Programme 2020

Mains & Interview

- Mains GS Syllabus

- Mains GS Strategy

- Mains Answer Writing Practice

- Essay Strategy

- Fodder For Essay

- Model Essays

- Drishti Essay Competition

- Ethics Strategy

- Ethics Case Studies

- Ethics Discussion

- Ethics Previous Years Q&As

- Papers By Years

- Papers By Subject

- Be MAINS Ready

- Awake Mains Examination 2020

- Interview Strategy

- Interview Guidance Programme

Current Affairs

- Daily News & Editorial

- Daily CA MCQs

- Sansad TV Discussions

- Monthly CA Consolidation

- Monthly Editorial Consolidation

- Monthly MCQ Consolidation

Drishti Specials

- To The Point

- Important Institutions

- Learning Through Maps

- PRS Capsule

- Summary Of Reports

- Gist Of Economic Survey

Study Material

- NCERT Books

- NIOS Study Material

- IGNOU Study Material

- Yojana & Kurukshetra

- Chhatisgarh

- Uttar Pradesh

- Madhya Pradesh

Test Series

- UPSC Prelims Test Series

- UPSC Mains Test Series

- UPPCS Prelims Test Series

- UPPCS Mains Test Series

- BPSC Prelims Test Series

- RAS/RTS Prelims Test Series

- Daily Editorial Analysis

- YouTube PDF Downloads

- Strategy By Toppers

- Ethics - Definition & Concepts

- Mastering Mains Answer Writing

- Places in News

- UPSC Mock Interview

- PCS Mock Interview

- Interview Insights

- Prelims 2019

- Product Promos

Drishti IAS Blog

- 75 Years of Independence: The Changing Landscape of India

75 Years of Independence: The Changing Landscape of India Blogs Home

- 14 Aug 2022

There is an old saying that India is a new country but an ancient civilization, and this civilization has seen tremendous changes throughout its history.

From being an education hub of the world in ancient times to becoming the IT hub of the world today, the Indian landscape has come a long way. Taking 15 th August 1947 as our frame of reference, we find that there are several fields like Science and Technology, economy, and human development where India has shown remarkable progress. However, some fields like health and education still seem to be taken care of. Let us look at these aspects of Indian development individually.

The Landscape of Science and Technology

When the Britishers left India, they left behind a broken, needy, underdeveloped, and economically unstable country. After independence, India prioritized scientific research in its first five-year plan. It paved the way for prestigious scientific institutes like IITs and IISC. After just three years of independence, the Indian Institute of Technology has established in 1950. These institutions promoted research in India with the aid of foreign institutions. From launching its first satellite Aryabhatta in 1975 to being the first country to reach the orbit of Mars, India has taken confident strides in the field of space research technology, thanks to the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). We can proudly state that India is standing at par with countries like USA and China, same goes with the field of biotechnology also where India is producing vaccines for the entire world. The success of UPI is also a case study for the world with 9.36 billion transactions worth Rs. 10.2 trillion in Q1 of 2022 only.

Economic Landscape

India faced several issues following its independence, including illiteracy, corruption, poverty, gender discrimination, untouchability, regionalism, and communalism. Numerous issues have acted as major roadblocks to India's economic development. When India declared its independence in 1947, its GDP was mere 2.7 lakh crore accounting for 3% of the world GDP. In 1965, the Green Revolution was started in India by M. S. Swaminathan, the father of the Green Revolution. During the Green Revolution, there was a significant increase in the crop area planted with high-yielding wheat and rice types. From 1978–1979, the Green Revolution led to a record grain output of 131 million tonnes. India was then recognized as one of the top agricultural producers in the world. With the construction of linked facilities like factories and hydroelectric power plants, a large number of jobs for industrial workers were also generated in addition to agricultural workers.

Today India is the 5 th largest economy in the world with 147 lakh crore GDP, accounting for 8% of global GDP. In recent years, India has seen a whopping rise of 15,400% in the number of startups, which rose from 471 in 2016 to 72,993 as of June 2022. This phenomenal rise in startups has also produced millions of new jobs in the country.

Infrastructure

The India of today is different from India at the time of freedom. In the 75 years of independence, Indian Infrastructure has improved drastically. The overall length of the Indian road network has grown from 0.399 million km in 1951 to 4.70 million km as of 2015, which makes it the third largest roadway network in the world. Additionally, India's national highway system now spans 1, 37, 625 kilometres in 2021, up from 24,000 km (1947–1969).

After over 70 years of independence, India has risen to become Asia's third-largest electricity generator. It increased its ability to produce energy from 1,362 MW in 1947 to 3, 95, 600 MW. In India, the total amount of power produced increased from 301 billion units in 1992–1993 to 400990.23 MW in 2022. The Indian government has succeeded in lighting up all 18,452 villages by April 28, 2018, as opposed to just 3061 in 1950, when it comes to rural electrification.

The Landscape of Human Development

In 1947 India had a population of 340 million with a literacy rate of just 12%, today it has a population of nearly 1.4 billion and a literacy rate of 74.04%. The average life expectancy has also risen from 32 years to 70 years in 2022.

The Landscape of Education and Health

In 1947, India had a population of 340 million with a literacy rate of just 12%, today it has a population of nearly 1.4 billion and a literacy rate of 74.04%. The average life expectancy has also risen from 32 years to 70 years in 2022. Though India has shown remarkable progress In terms of literacy rate, the quality of higher education is still a cause of major concern. There is not a single Indian University or Institute in the top 100 QS World University Ranking. With the largest youth population in the world, India can achieve wonders if its youth get equipped with proper skills and education. The health, sector is also worrisome. The doctor-to-patient ratio is merely 0.7 doctors per 1000 people as compared to the WHO average of 2.5 doctors per 1000 people. A recent study shows that 65% of medical expenses in India are paid out of pocket by patients and the reason is that they are left with no alternative but to access private healthcare because of poor facilities in public hospitals.

The Political Landscape

Jawaharlal Nehru was appointed as India's first prime minister in 1947, following the end of British rule. He promoted a socialist-economic system for India, including five-year plans and the nationalization of large sectors of the economy like mining, steel, aviation, and other heavy industries. Village common areas were taken, and a massive public works and industrialization drive led to the building of important dams, roads, irrigation canals, thermal and hydroelectric power plants, and many other things. India's population surpassed 500 million in the early 1970s, but the “Green Revolution” significantly increased agricultural productivity, which helped to end the country's long-standing food problem.

From 1991 to 1996, India's economy grew quickly as a result of the policies implemented by the late Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao and his Finance Minister at the time, Dr Manmohan Singh. Poverty had decreased to about 22%, while unemployment has been continuously reducing. Growth in the gross domestic product exceeded 7%.

India's first female Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, held office from 1966 until 1977 for three consecutive terms before serving a fourth term (1980–84). India elected Pratibha Patil as its first female president in 2007.

India's economy has expanded significantly in the twenty-first century. Under the Prime ministership of Narendra Modi (BJP), many significant changes have taken place like the scraping of Section 370, strengthening the Defence systems, creating a startup-friendly environment and much more. To expand infrastructure and manufacturing, the Modi administration launched several programs and campaigns, including “Make in India”, “Digital India”, and the “Swachh Bharat project.”

The Legal Landscape

Before independence, the Privy Council was the highest appellate authority in India. This Council was abolished as the first action following independence. The abolition of the Privy Council Jurisdiction Act was passed by the Indian Constituent Assembly in 1949 to eliminate the Privy Council's authority over appeals from India and to make provisions for outstanding appeals. It was B. R. Ambedkar's sharp legal intellect to draft a constitution for the newly sovereign country. In all executive, legislative, and judicial matters in the nation, the Constitution of India serves as the supreme law. The Indian legal system has developed into a key component of the largest democracy in the world and a pivotal front in the fight to protect constitutional rights for all citizens. Since it was first adopted in 1950, the Indian Constitution has had 105 modifications as of October 2021. The Indian Constitution is divided into 22 parts with 395 articles. Later, through various changes, further articles were added and amendments were made. According to the online repository maintained by the Legislative Department of the Ministry of Law and Justice of India as of July 2022, there are around 839 Central laws. The Indian legal system has a promising and forward-thinking future, and in the twenty-first century, young, first-generation lawyers are entering the field after graduating from the best law schools.

The Landscape of the Defence Sector

The Indian military ranked 4 of 142 out of the countries considered for the annual GFP review. From being defeated by the Chinese army in 1962 to becoming one of the largest defence systems in the world, India has surely learnt from its past errors. One of the reasons the Indian defence system has been able to attain its present reputation is the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO) which was established in 1958. Since its founding, it has created many significant programs and critical technologies, including missile systems, small and big armaments, artillery systems, electronic warfare (EW) systems, tanks, and armoured vehicles. India began working on nuclear energy in the late 1950s and had indigenous nuclear power stations by the 1970s. India had also begun developing nuclear weapons and producing fissile material concurrently, which allowed for the purportedly harmless nuclear explosion in Pokhran in 1971. The Integrated Guided Missile Development Program (IGMDP), under the direction of APJ Abdul Kalam and with the support of the Ordnance Factories, was established in 1983. In 1989, the longer-range Agni was independently designed and tested. Later, India and Russia collaborated to design and produce the Brahmos supersonic cruise missile. India currently leads several other nations in the production of defences. India is one of about a dozen nations that have built and produced their fighter jets, helicopters, submarines, missiles, and aircraft carriers.

Analyzing the different landscapes of India we find that we have come a long way in our journey but still, there is a lot to be done if we want to make India a ‘super power’. A lot will depend on our people’s willingness to change, ensuring the equal participation of women in the workforce, including marginalized communities in our economic growth, and last but not least is having a liberal and progressive and unbiased mindset.

As we are celebrating “Azaadi ka Amrit Mahotsav”, the completion of 75 years of independence can be taken as a new opportunity to build an India of our aspirations and make positive contributions to the changing landscape of India.

Aarifa Nadeem

https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/opinion/how-we-have-done-since-gaining-freedom-from-our-colonial-masters-seven-decades-ago

https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/news/story/qs-world-university-rankings-2023-top-10-universities-globally-and-top-10-in-india-1960806-2022-06-10

https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/national/5-reasons-why-indias-healthcare-system-is-struggling/article34665535.ece

https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/economic-survey-high-out-of-pocket-expenses-for-health-can-lead-to-poverty/article33699314.ece

https://www.mapsofindia.com/my-india/technology/development-in-india-after-independence#:~:text=Infrastructure%20Development,%2C37%2C625%20km%20(2021) .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_India_(1947%E2%80%93present)#: ~:text=India%20became%20a%20sovereign%20democratic,the%2042nd%20Constitution %20Amendment%201976.

http://www.barcouncilofindia.org/about/about-the-legal-profession/history-of-the-legal-profession/

Comments (0)

From Getting Kicked Out Of NSD To Bagging ‘Panchayat’, Durgesh Kumar Talks About His Journey

- Entertainment

Hyderabad Woman Shares How Uber Driver Left Without Payment As She Was Going Through Crisis

- Food For Thought

Forget Congress & BJP, Desis Are Rooting For Cute ‘Sabse Achchhi Party’ That Badly Lost

Israeli Tourists Asked To Visit Indian Beaches After Maldives Ban But Desis Show Reality

10 inspiring indians who are making positive changes in the society.

- 18.6K shares

- Facebook Messenger

Inspiration is what keeps us going. These amazing, brave, dedicated inspiring leaders of India are doing groundbreaking work in the social sector and working for a better tomorrow. They help us believe that there is good in the world. So here I have enlisted 10 such inspiring Indians who have gone against all odds to reach out to people in a way that is entirely different. This post is not really in any particular order because, after all, ranking them seems a little fruitless.

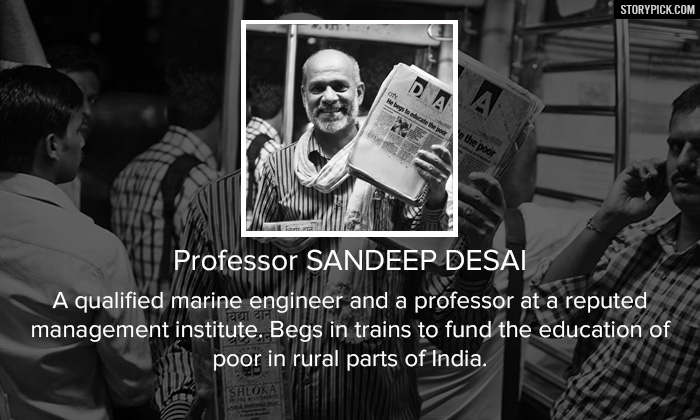

Since 1997, he quit his job and started serving the society and took up other assignments to fund Shloka, a free English-medium school for children from the Goregaon slums in Mumbai. His foundation currently runs 4 English Medium schools which provide free education to the poor. He requests small donations and goes around shouting “Vidyadaan Shreshth Daan” in local trains. This man is one of those faces of the society who break the general belief that one must have their pockets full to do something for the society.

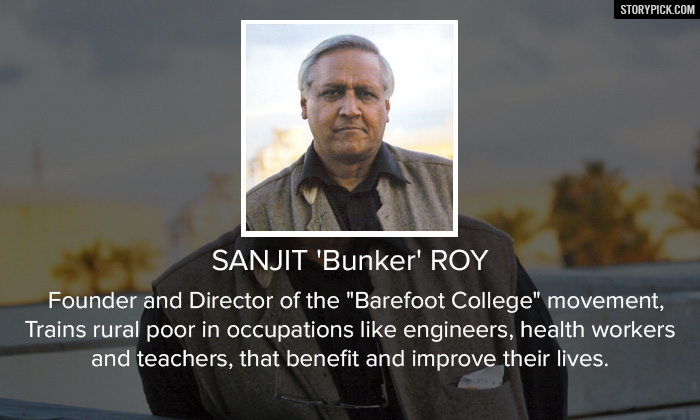

The college gives simple school lessons in reading, writing and accounting to adults and children. It works to impart skills people’s need in their everyday lives. The most sought after students are “drop-outs, cop-outs and wash-outs”. He has helped over 1000 villages in 37 countries to get electrification with solar power . The ‘Barefoot approach’ may be viewed as a ‘concept’, ‘solution’, ‘revolution’, ‘design’ or an ‘inspiration’ but it is really a simple message that can easily be replicated by the poor and for the poor in neglected and underprivileged communities anywhere the world.

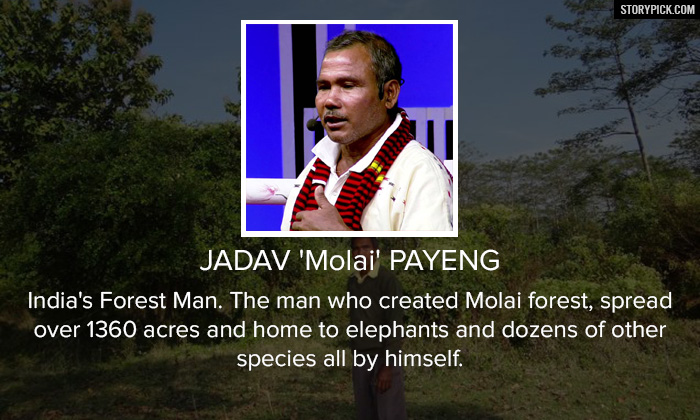

Never underestimate the power of ‘One’ . In 1979, Payeng, then 16, encountered a large number of snakes that had died due to excessive heat after floods washed them onto the tree-less sandbar. That is when he planted around 20 bamboo seedlings on the sandbar. He worked on projects after projects and transformed the area into forest over 30 years. Molai forest, now houses Bengal tigers, Indian rhinoceros, over 100 deer and rabbits besides apes and several varieties of birds, including a large number of vultures.

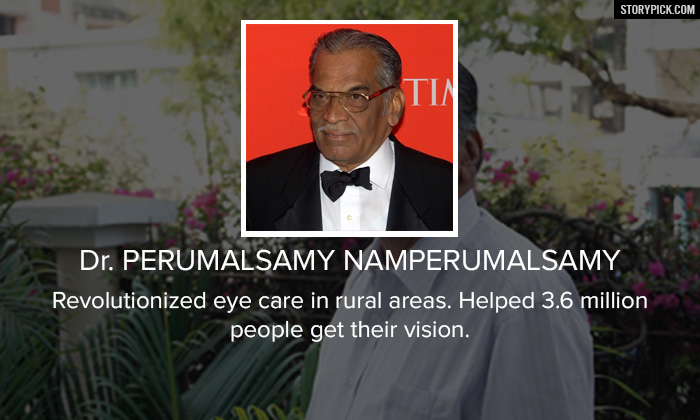

‘All people have a right to sight’. Dr. Perumalsamy Namperumalsamy and his army of cataract fixers at India’s Aravind Eye Care Hospitals have been performing surgeries to give the blind people their eyesight back . The surgery has been around for decades, but the chairman of Aravind — which was founded in 1976 with the goal of bringing assembly-line efficiency to health care — figured out how to replace cataracts safely and quickly and helped 3.6 million people get their vision. Featured in TIME’s Top 100 list.

There are men who squirm at the mention of a woman’s period. Then there’s Muruganantham, who re-engineered a sanitary machine which makes about 120 napkins an hour . Currently more than 1300 machines made by his start-up company are installed across 27 states in India and seven other countries. Receiving the award from the Indian president was not the happiest moment of his life. But his proudest moment came after he installed a machine in a remote village in Uttarakhand, in the foothills of the Himalayas.

This activity consisted of providing free meals for cancer patients and their relatives. Beginning with fifty, the number of beneficiaries soon rose to hundred, two hundred, three hundred. As the numbers of patients increased, so did the number of helping hands. The ‘Jeevan Jyoti’ trust founded by Mr Sawla now runs more than 60 humanitarian projects. For last 27 years, millions of cancer patients and their relatives have found ‘God’, in the form of Harakhchand Sawla.

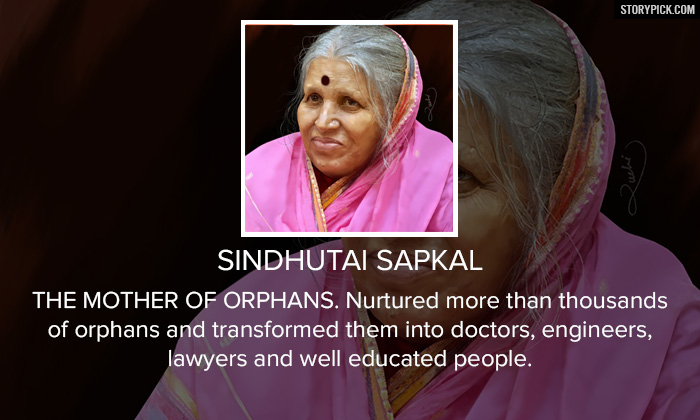

Her life started as being an unwanted child, followed by an abusive husband who abandoned her when she was nine months pregnant. But Sindhutai emerged stronger with every difficulty she faced and became a ‘mother’ to over 1400 homeless children. Currently she has opened 5 shelter homes for the orphans where they are being educated as well as provided all the basic amenities of life . She has proved that a mother can be someone who adopts you and takes proper care of you.

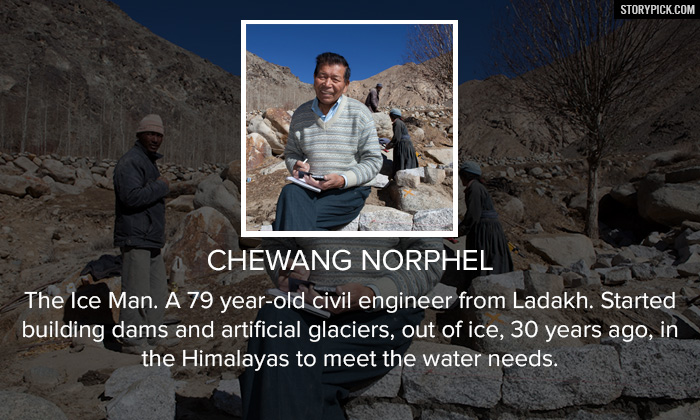

‘The Ice Man’. Sounds like a pretty cool super hero, and he kind of is. You’ll find him in the Himalayas. Back in 1987, Norphel invented artificial glaciers and started constructing massive dams in order to efficiently use the water gathered from melting ice to change the lives of the farmers. 30 years ago, Norphel was laughed at and never taken seriously, but today he stands in front of the camera as a proud citizen, and a real climate hero. He has proved that if man is the one responsible for disturbing nature, he also has the capacity to save it.

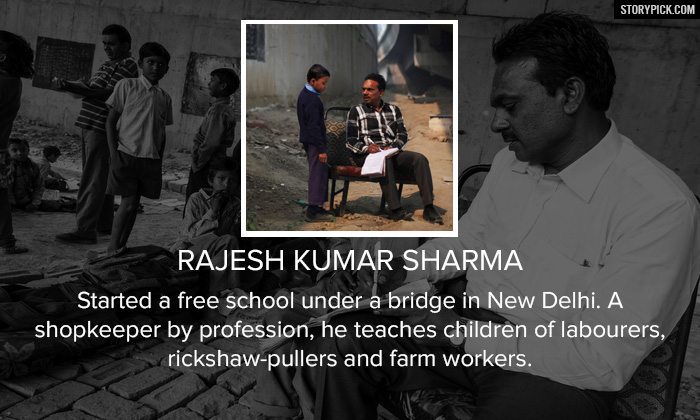

Sharma, a father of three from Aligarh, was forced to drop out of college in his third year due to financial difficulties. When he decided to start the free school, he didn’t want other children to face the same difficulties. So he eventually persuaded local laborers and farmers to allow their children to attend his school instead of working to add to the family income. The children from the neighbouring villages attend class for two hours daily, where they learn math and basic reading and writing skills. He believes, his greatest achievement was changing the attitude of his students’ parents. Most of them now encourage their children to study.

Arputham was born in Kolar Gold Fields, near Bangalore, in the south of India. He moved to Mumbai when he was 18 to work as a carpenter. Having no place to live in, he began sleeping outside people’s houses in Janata Colony, a slum of around 70,000 people. When the inhabitants of the slum were threatened with eviction, he united the community in organizing protests and fighting injustice. Over the years, Arputham has built 30,000 houses in India, and 1,00,000 houses abroad. For his remarkable work, he has been awarded the the Padma Shri. He didn’t win the Nobel Peace Prize but Jockin Sir has dedicated his life to bring peace for slum dwellers.

This may be a small force at present, but if we all stand together , we can wipe out all the social tensions.

I salute these true heroes who have made us all extremely proud.

Fact Source

- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

IMPACT INDIA

Women, prosperity, and social change in india.

Social enterprise, which promises both economic empowerment and social trans-formation, is driving tremendous positive change in the lives of women in India. But it is also at the heart of a growing debate about the past and future of India's social sector.

- order reprints

- related stories

By Isabel Salovaara & Jeremy Wade Feb. 14, 2018

Women first, prosperity for all. This was the theme of the 10th Global Entrepreneurship Summit , hosted late last year in Hyderabad. It was also an unofficial theme for the year itself. Around the world, we witnessed demands by women to address persistent gender inequalities as a prerequisite to social and economic progress.

In 2018, one pressing question is how to convert the momentum generated by movements like #MeToo into lasting impact. A recent five-country study , commissioned by the British Council, on the mutual interdependence of social enterprise initiatives and women’s empowerment movements provides insights into the strategies for—and barriers to—long-term change.

As the study’s North India research partners, we conducted a series of interviews, a survey of social enterprises in India, and focus groups across nine Indian cities to galvanize conversation on the contributions of social enterprise to women’s empowerment and the challenges at hand.

For this study, we defined a social enterprise as an organization with a central social or environmental mission that earns at least 25 percent of its revenue through commercial activity. Such a definition enabled us to make international comparisons between countries with diverse regulatory and legal landscapes in relation to social enterprise. It also provoked questions about the place of social enterprise and other organizational forms within longstanding social and women’s movements in India.

Our research highlighted the multiple meanings behind “women first,” including the significance of women’s leadership and the importance of attending to the needs of women beneficiaries and employees in the social enterprise sector. In this three-part series, we explore the impact of social enterprise—including its ambiguous place among older social organization models—on women in India.

Financial empowerment as a way toward social transformation

There are an estimated two million social enterprises in India, according to a previous British Council report mapping the social enterprise ecosystem . About a third (more than 600,000) focus on empowering women and girls as primary beneficiaries of their social mission.

Among our survey respondents, the most prevalent approaches focus on skill development and job creation. Many of these social enterprises, including women’s clothing producers rangSutra and KhaDigi , operate within the handicrafts sector, the second largest segment of India’s economy after agriculture. Some, like Jaipur Living (formerly Jaipur Rugs), focus on creating sustainable livelihoods for women by combining flexible working hours with connections to global export markets.

But social enterprises span a wide range of emerging industries. Some integrate rural youth, including young women, into India’s thriving business process outsourcing (BPO) industry as call-center employees. Taxi services by and for women, such as Sakha Consulting Wings , train and employ women in the male-dominated field of commercial driving, while also advancing the cause of women’s safety and mobility in urban India. Through Odanadi Trust in Mysore or Sheroes Hangout in Agra, restaurants, cafés, and ice cream parlors provide women who have survived trafficking or abuse with a means of earning money and developing skills.

The prominence of employment and income generation among social enterprise strategies for women’s empowerment in India reflects the unique strengths of the hybrid social enterprise model. Applying market logics to social issues is the sector’s raison d’être .

These strategies also reflect genuine needs of women in India. Many participants in our focus groups argued that financial standing gives women more decision-making power in their families and communities. “Social factors and forces must be combined with economic factors and forces,” says Shalabh Mittal, CEO of the School for Social Entrepreneurs India . Only then, he says, will more conservative interests buy in to the idea of social change. Or, as one participant in Jaipur bluntly put it: “When you earn money, men start respecting you.”

Yet this equation, so appealing in its simplicity, did not go unchallenged. Some participants were skeptical that financial empowerment and market integration, without parallel (and often unprofitable) efforts to change ingrained mindsets, could accomplish all that is needed to put women and girls on equal footing with men. Their caution echoed deeper concerns about the place of social enterprise within the constellation of other models comprising India’s social sector.

Hybrid models in the social sector

At a Kolkata focus group, participants raised a provocative question: Do we really need to distinguish NGOs from social enterprise? As a whole, the group agreed that women’s empowerment should be the key issue, rather than who does it.

This question shed light on a source of tension that ran through many of our conversations during this research. Designating some Indian organizations as social enterprises and some as “just” NGOs (or businesses) could have wider ranging effects on the social sector. Will the popularity of social enterprise further reduce the resources available to traditional nonprofits pursuing critical work in advocacy and other fields less amenable to monetization?

Unlike countries with newly emerging legal forms explicitly designed to enable organizations to pursue both social and commercial objectives , a distinct hybrid legal entity does not yet exist in India. Indian social enterprises must currently incorporate as one of the following: a nonprofit, which cannot legally maintain substantial surpluses from year to year; a private company; or a hybrid structure with separate nonprofit and for-profit entities. These choices have material consequences, since some forms of support (such as government contracts under social programs) are largely reserved for nonprofits, while others (such as impact investment funding) are more accessible to social enterprises with a stronger business orientation.

These two organizational forms also carry historically gendered meanings. India’s nonprofit sector grew out of the voluntary movement, which promoted social progress driven by the unpaid social work of volunteers, says Ranjana Kumari, director of the Centre for Social Research in Delhi. This vision offered limited scope for asset formation and financial gain by social organizations. As Kumari asks sardonically, “What do volunteers eat? Grass?” So-called social work and NGOs became a feminized domain , since women were not usually expected to be the primary providers for their families.

Many hope social enterprise can transform this image of the social sector by making both “doing good and doing well” possible. But as policy develops over time to recognize and support social enterprise in India , the sector must avoid several pitfalls if it is to maximize the hybrid model’s benefits for women. The “social” in social enterprise in itself cannot justify restrictions on financial remuneration for women and the organizations that support them. Social enterprise must be positioned as a partner, not a replacement, for existing players in the women’s empowerment field.

Expanding prosperity

The market-based hybridity of social enterprise remains its distinguishing feature, and economic participation can indeed enable women to influence the direction of social change to create a more just social and economic order. And yet social enterprise offers significant opportunities beyond financial gain—many organizations represented in our study address issues of sanitation, childcare, and women’s representation as decision-makers in their communities. Often, especially in health and education, these organizations empower women and girls alongside men and boys . If putting women first is to bring “prosperity for all,” we must expand the reach of economic empowerment as well as the definition of prosperity.

Support SSIR ’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges. Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today .

Read more stories by Isabel Salovaara & Jeremy Wade .

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation

Indians say it is important to respect all religions, but major religious groups see little in common and want to live separately, table of contents.

- The dimensions of Hindu nationalism in India

- India’s Muslims express pride in being Indian while identifying communal tensions, desiring segregation

- Muslims, Hindus diverge over legacy of Partition

- Religious conversion in India

- Religion very important across India’s religious groups

- Near-universal belief in God, but wide variation in how God is perceived

- Across India’s religious groups, widespread sharing of beliefs, practices, values

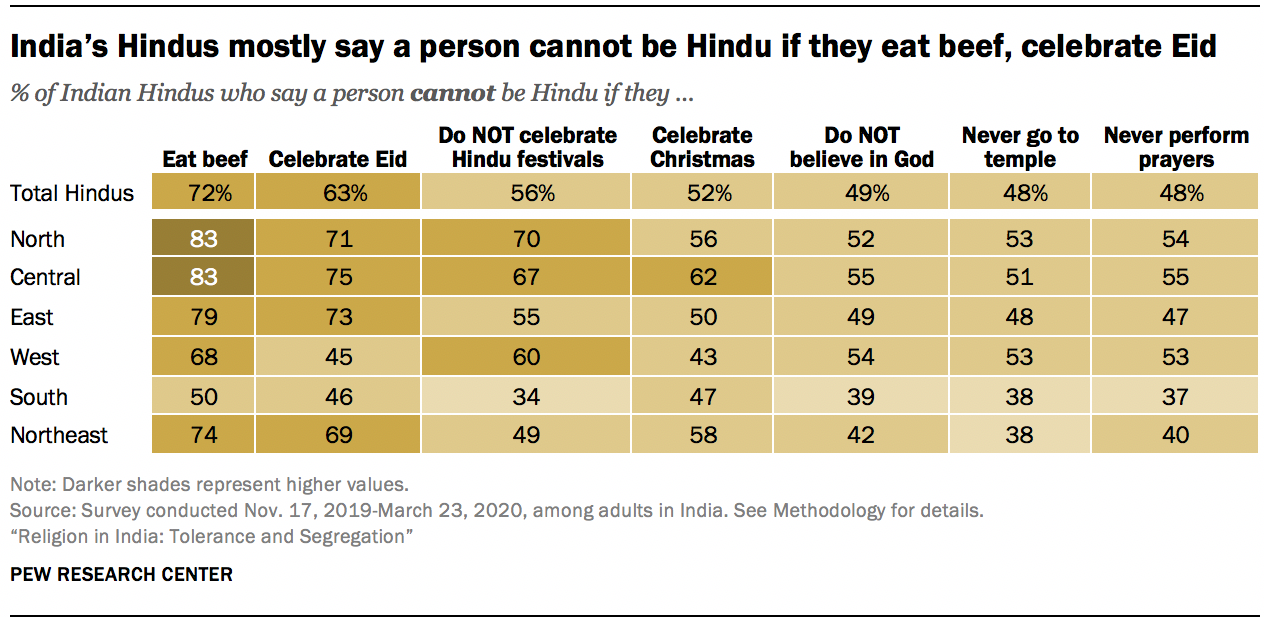

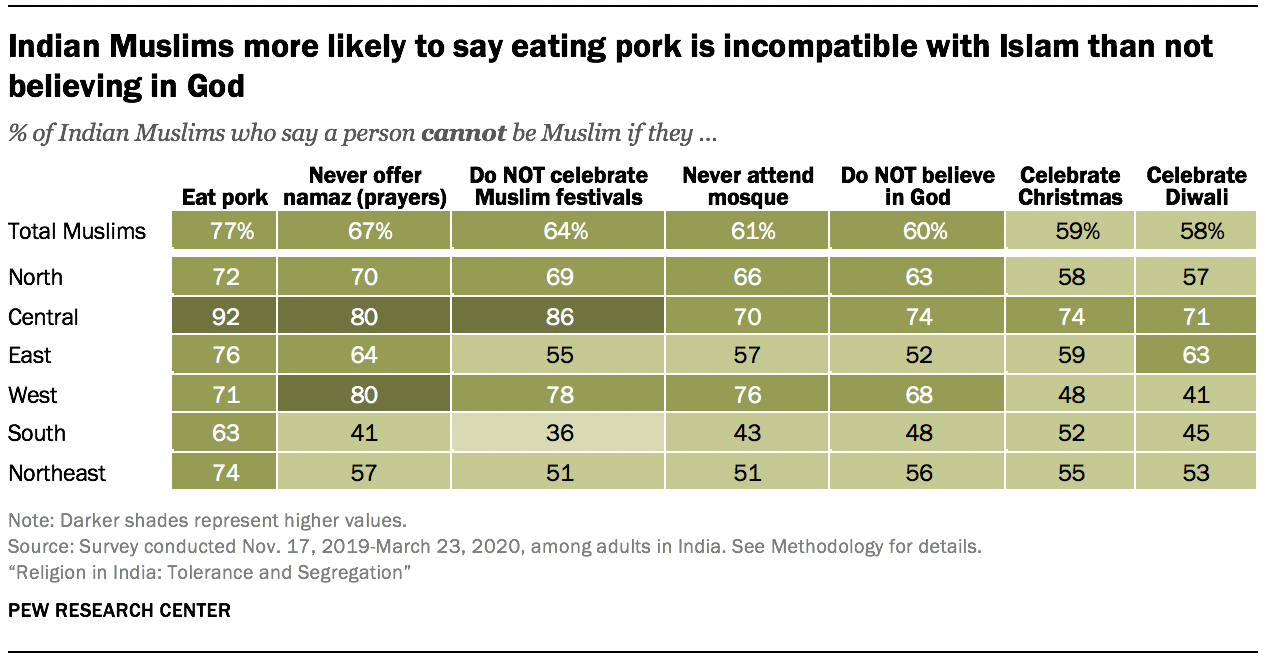

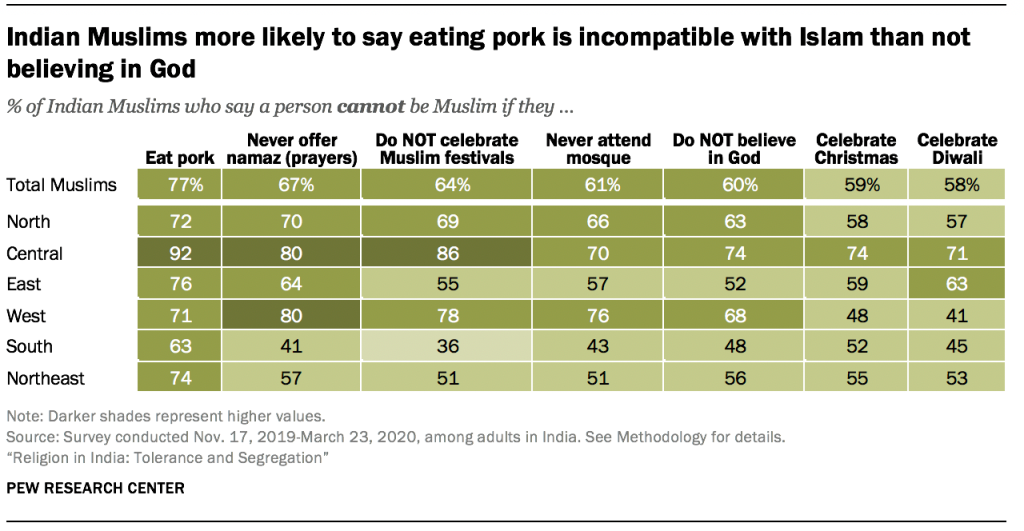

- Religious identity in India: Hindus divided on whether belief in God is required to be a Hindu, but most say eating beef is disqualifying

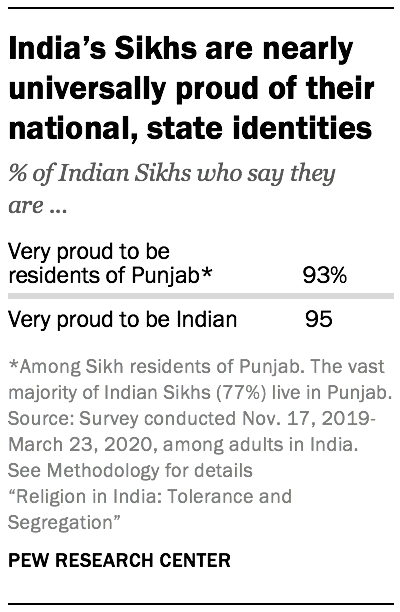

- Sikhs are proud to be Punjabi and Indian

- 1. Religious freedom, discrimination and communal relations

- 2. Diversity and pluralism

- 3. Religious segregation

- 4. Attitudes about caste

- 5. Religious identity

- 6. Nationalism and politics

- 7. Religious practices

- 8. Religion, family and children

- 9. Religious clothing and personal appearance

- 10. Religion and food

- 11. Religious beliefs

- 12. Beliefs about God

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix A: Methodology

- Appendix B: Index of religious segregation

This study is Pew Research Center’s most comprehensive, in-depth exploration of India to date. For this report, we surveyed 29,999 Indian adults (including 22,975 who identify as Hindu, 3,336 who identify as Muslim, 1,782 who identify as Sikh, 1,011 who identify as Christian, 719 who identify as Buddhist, 109 who identify as Jain and 67 who identify as belonging to another religion or as religiously unaffiliated). Interviews for this nationally representative survey were conducted face-to-face under the direction of RTI International from Nov. 17, 2019, to March 23, 2020.

To improve respondent comprehension of survey questions and to ensure all questions were culturally appropriate, Pew Research Center followed a multi-phase questionnaire development process that included expert review, focus groups, cognitive interviews, a pretest and a regional pilot survey before the national survey. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into 16 languages, independently verified by professional linguists with native proficiency in regional dialects.

Respondents were selected using a probability-based sample design that would allow for robust analysis of all major religious groups in India – Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains – as well as all major regional zones. Data was weighted to account for the different probabilities of selection among respondents and to align with demographic benchmarks for the Indian adult population from the 2011 census. The survey is calculated to have covered 98% of Indians ages 18 and older and had an 86% national response rate.

For more information, see the Methodology for this report. The questions used in this analysis can be found here .

More than 70 years after India became free from colonial rule, Indians generally feel their country has lived up to one of its post-independence ideals: a society where followers of many religions can live and practice freely.

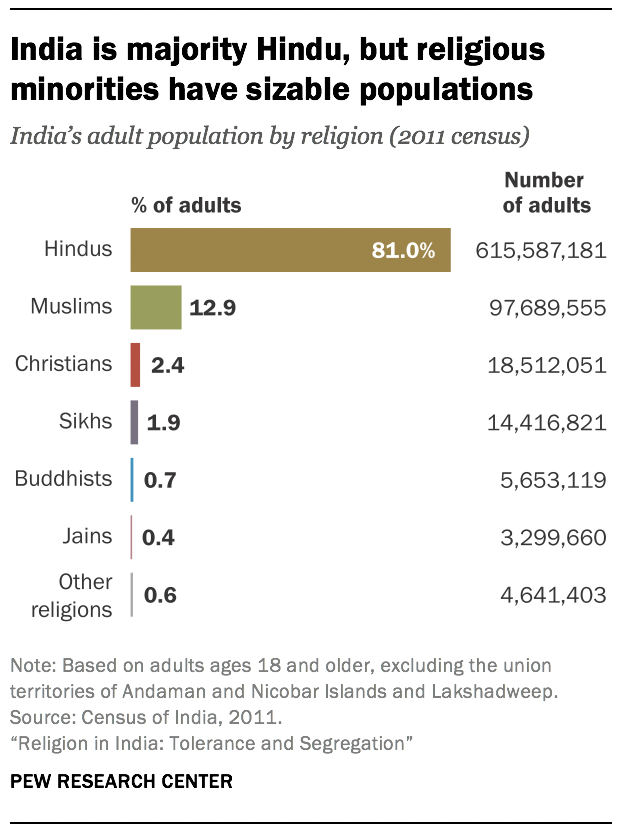

India’s massive population is diverse as well as devout. Not only do most of the world’s Hindus, Jains and Sikhs live in India, but it also is home to one of the world’s largest Muslim populations and to millions of Christians and Buddhists.

A major new Pew Research Center survey of religion across India, based on nearly 30,000 face-to-face interviews of adults conducted in 17 languages between late 2019 and early 2020 (before the COVID-19 pandemic ), finds that Indians of all these religious backgrounds overwhelmingly say they are very free to practice their faiths.

Related India research

This is one in a series of Pew Research Center reports on India based on a survey of 29,999 Indian adults conducted Nov. 17, 2019, to March 23, 2020, as well as demographic data from the Indian Census and other government sources. Other reports can be found here:

- How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society

- Religious Composition of India

- India’s Sex Ratio at Birth Begins To Normalize

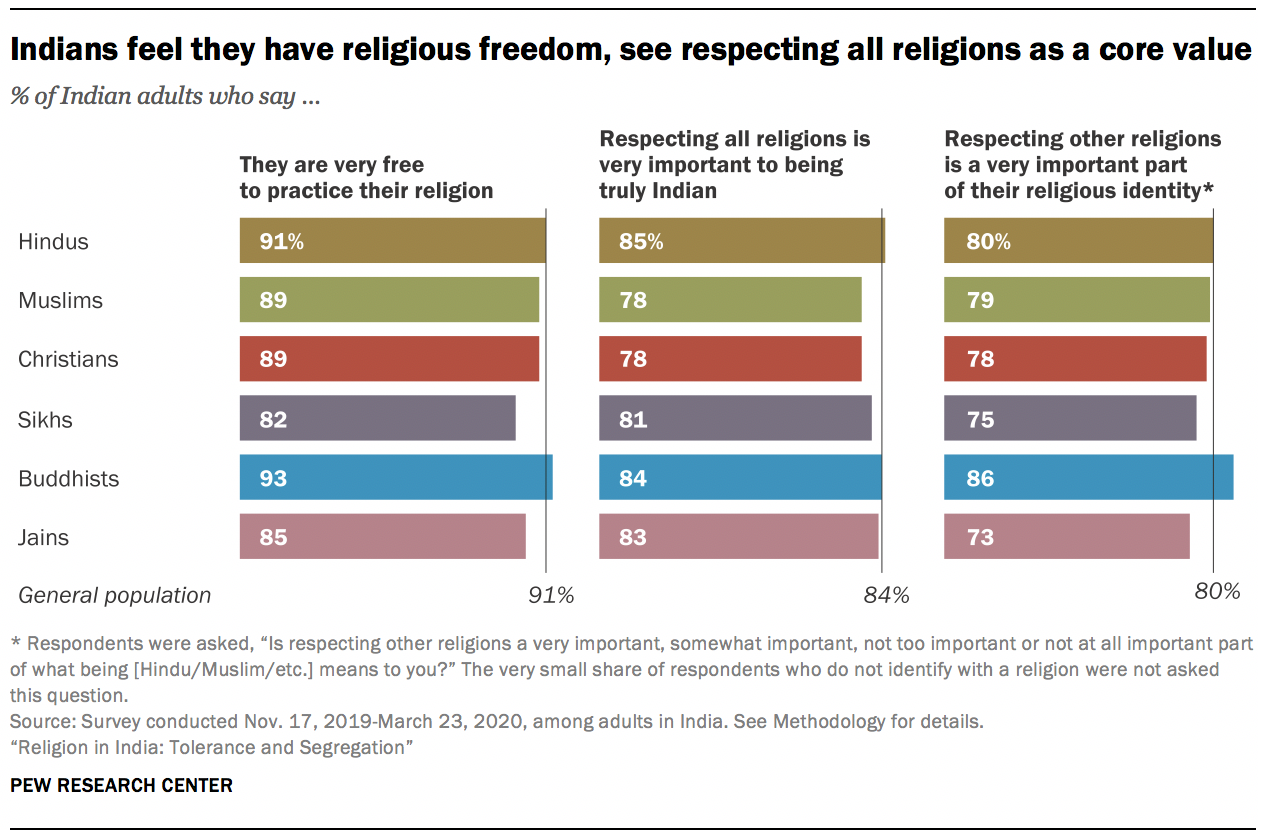

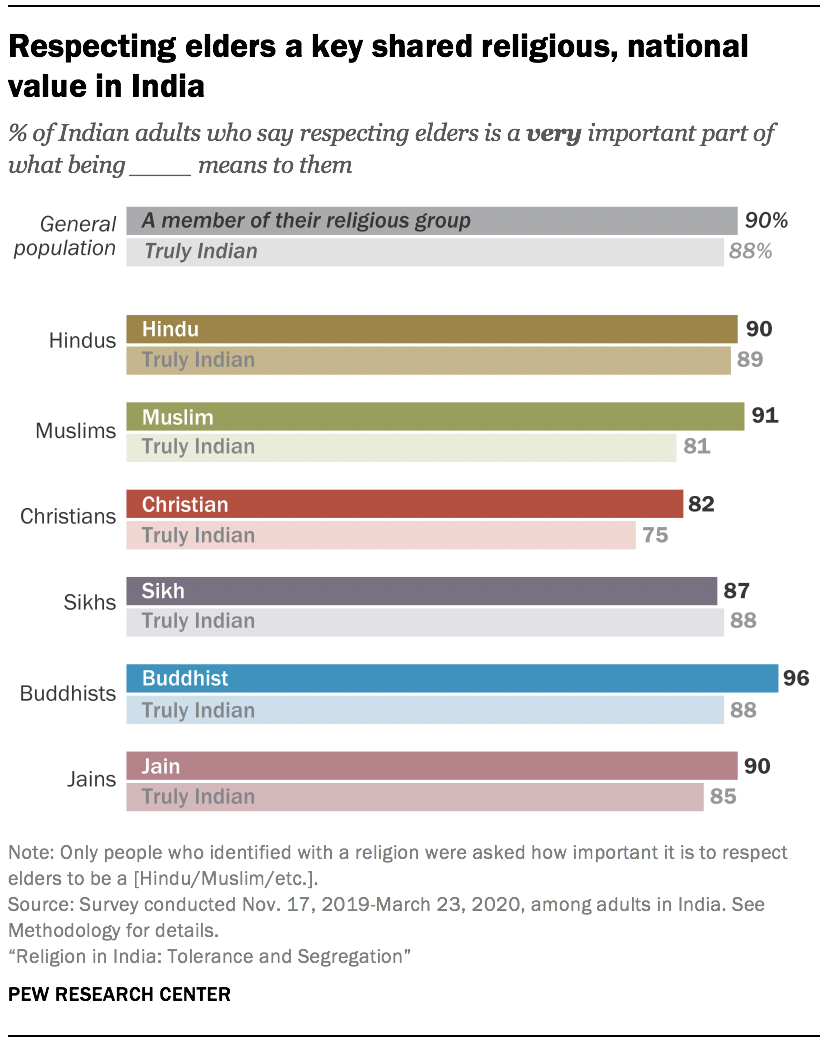

Indians see religious tolerance as a central part of who they are as a nation. Across the major religious groups, most people say it is very important to respect all religions to be “truly Indian.” And tolerance is a religious as well as civic value: Indians are united in the view that respecting other religions is a very important part of what it means to be a member of their own religious community.

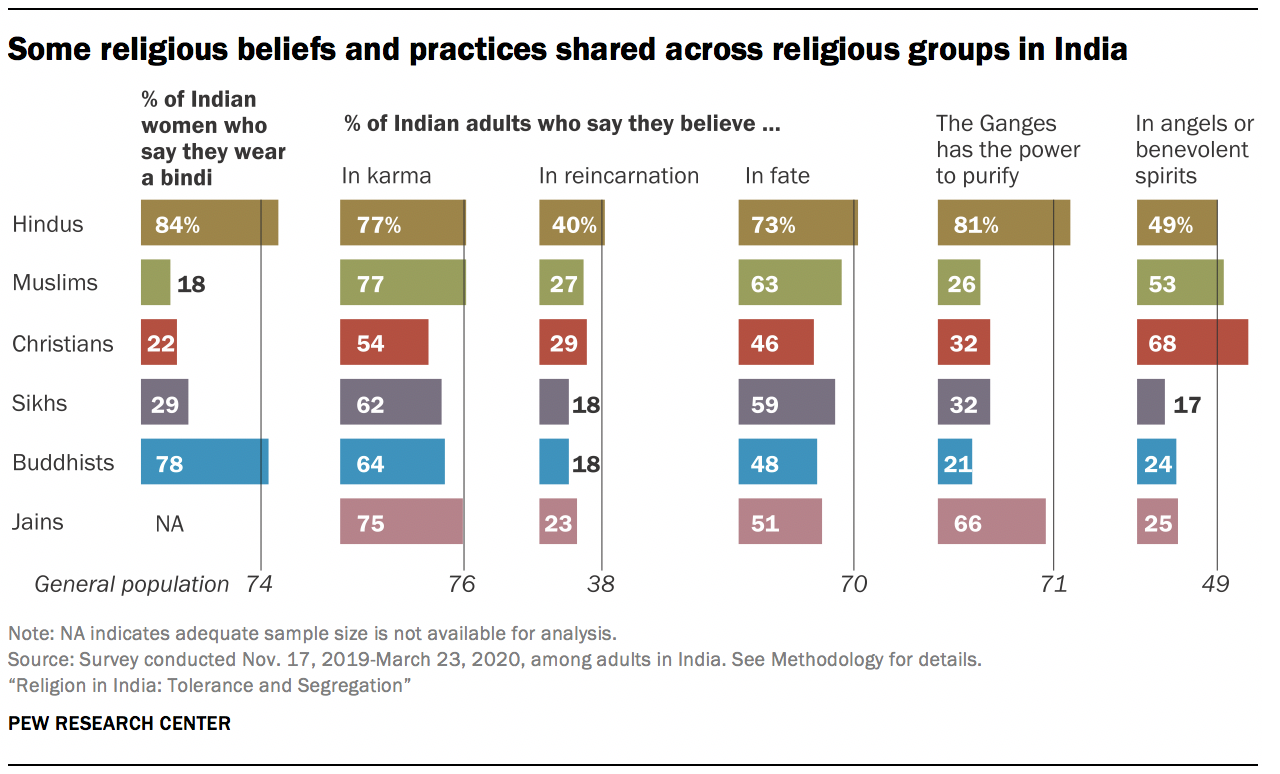

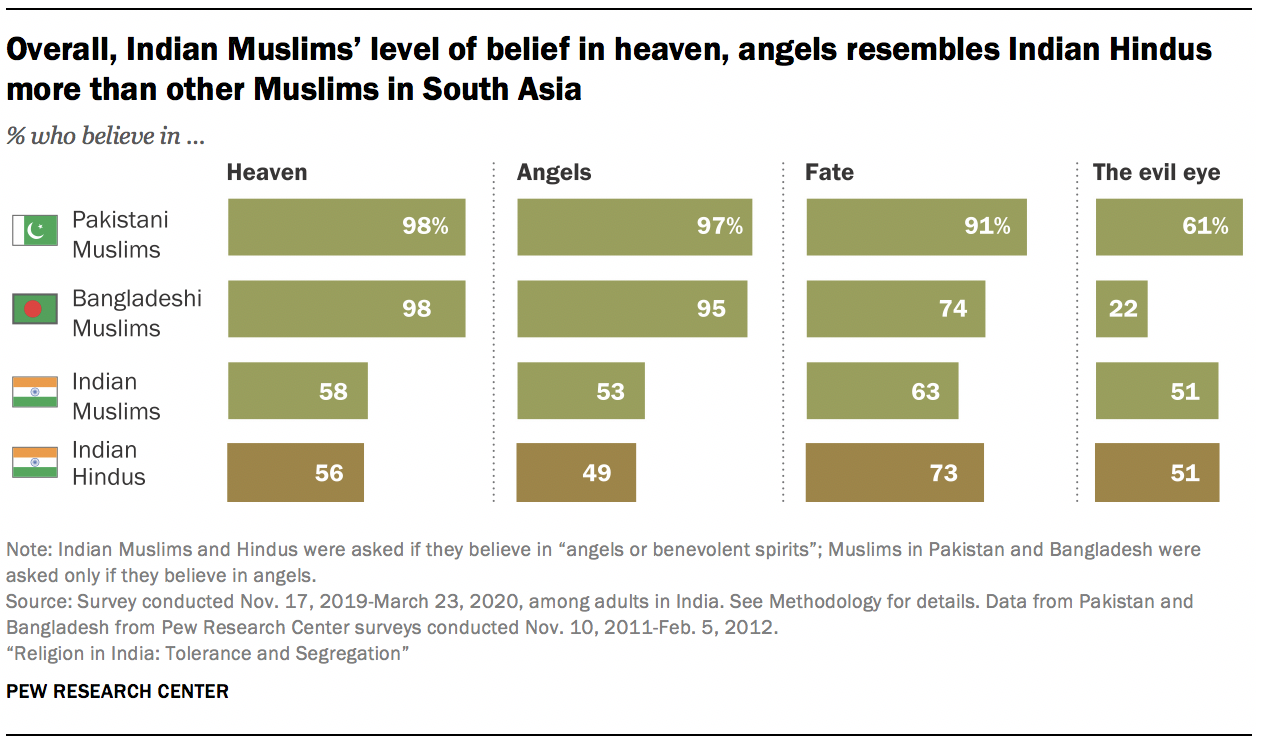

These shared values are accompanied by a number of beliefs that cross religious lines. Not only do a majority of Hindus in India (77%) believe in karma, but an identical percentage of Muslims do, too. A third of Christians in India (32%) – together with 81% of Hindus – say they believe in the purifying power of the Ganges River, a central belief in Hinduism. In Northern India, 12% of Hindus and 10% of Sikhs, along with 37% of Muslims, identity with Sufism, a mystical tradition most closely associated with Islam. And the vast majority of Indians of all major religious backgrounds say that respecting elders is very important to their faith.

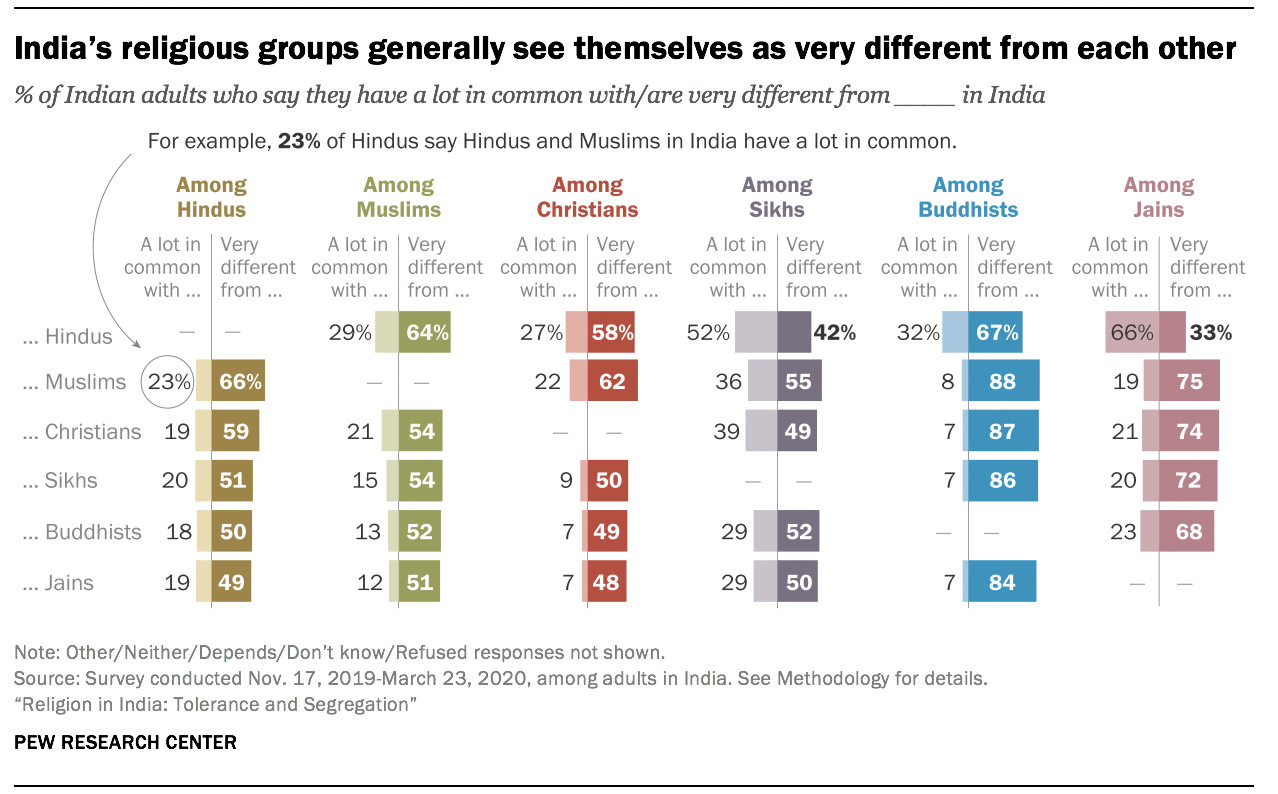

Yet, despite sharing certain values and religious beliefs – as well as living in the same country, under the same constitution – members of India’s major religious communities often don’t feel they have much in common with one another. The majority of Hindus see themselves as very different from Muslims (66%), and most Muslims return the sentiment, saying they are very different from Hindus (64%). There are a few exceptions: Two-thirds of Jains and about half of Sikhs say they have a lot in common with Hindus. But generally, people in India’s major religious communities tend to see themselves as very different from others.

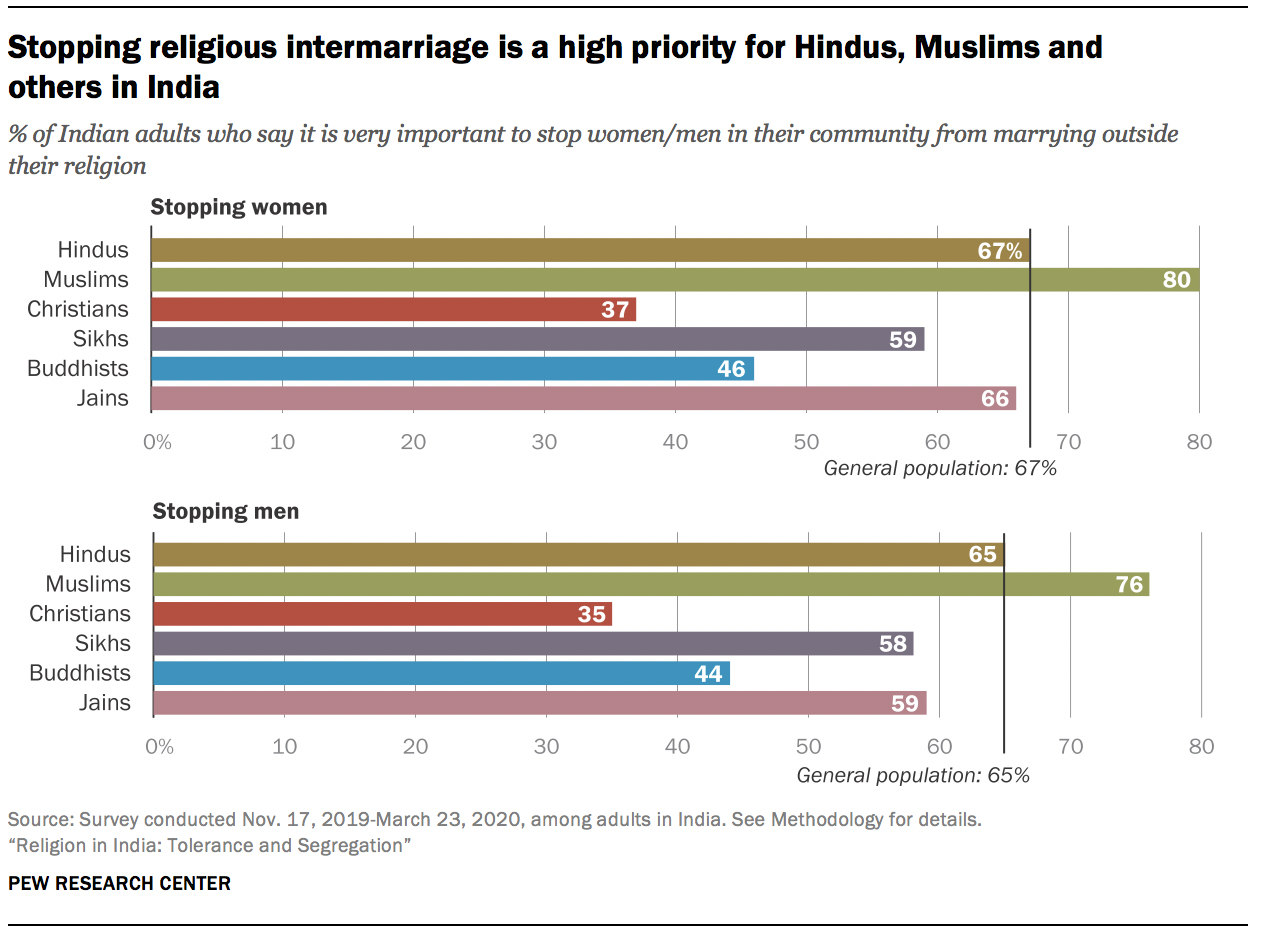

This perception of difference is reflected in traditions and habits that maintain the separation of India’s religious groups. For example, marriages across religious lines – and, relatedly, religious conversions – are exceedingly rare (see Chapter 3 ). Many Indians, across a range of religious groups, say it is very important to stop people in their community from marrying into other religious groups. Roughly two-thirds of Hindus in India want to prevent interreligious marriages of Hindu women (67%) or Hindu men (65%). Even larger shares of Muslims feel similarly: 80% say it is very important to stop Muslim women from marrying outside their religion, and 76% say it is very important to stop Muslim men from doing so.

Moreover, Indians generally stick to their own religious group when it comes to their friends. Hindus overwhelmingly say that most or all of their close friends are also Hindu. Of course, Hindus make up the majority of the population, and as a result of sheer numbers, may be more likely to interact with fellow Hindus than with people of other religions. But even among Sikhs and Jains, who each form a sliver of the national population, a large majority say their friends come mainly or entirely from their small religious community.

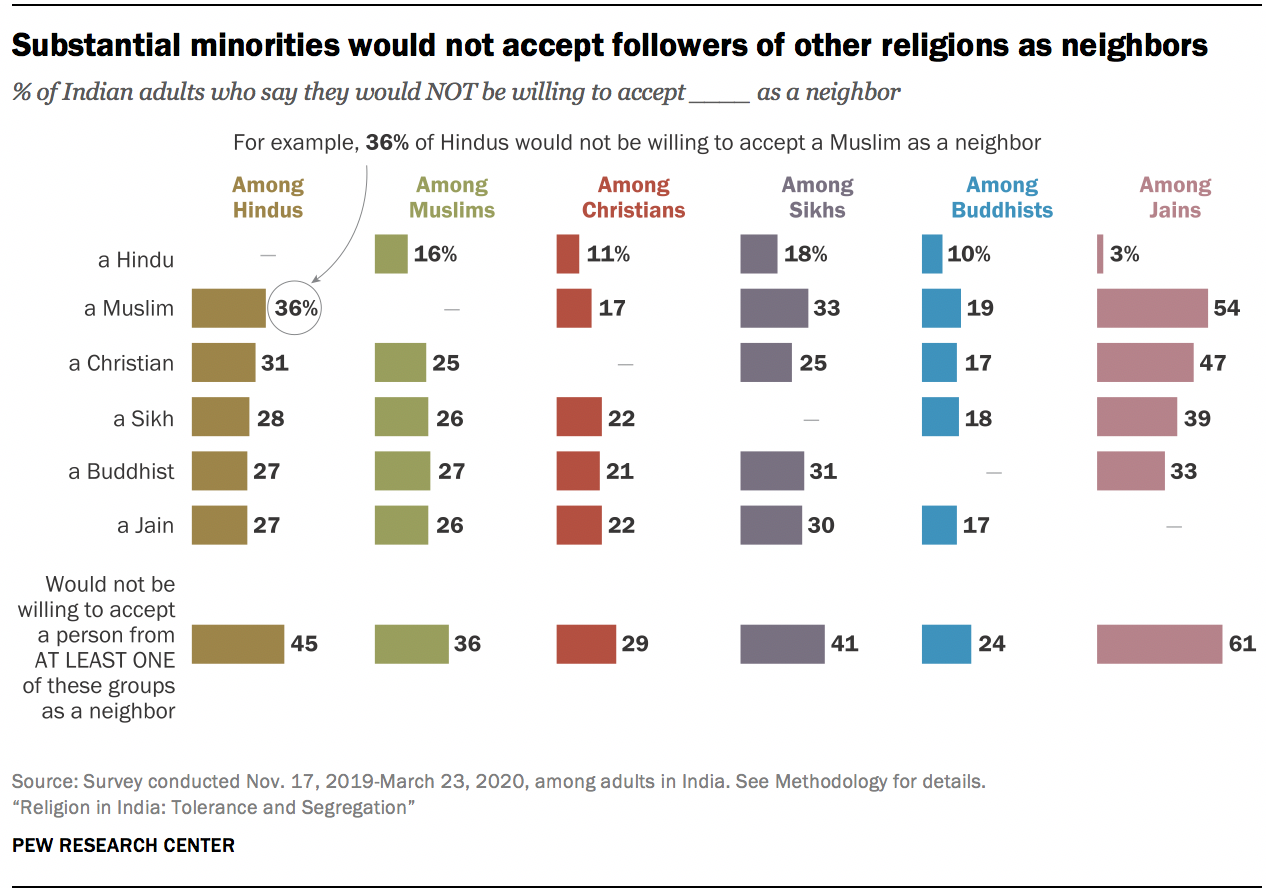

Fewer Indians go so far as to say that their neighborhoods should consist only of people from their own religious group. Still, many would prefer to keep people of certain religions out of their residential areas or villages. For example, many Hindus (45%) say they are fine with having neighbors of all other religions – be they Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist or Jain – but an identical share (45%) say they would not be willing to accept followers of at least one of these groups, including more than one-in-three Hindus (36%) who do not want a Muslim as a neighbor. Among Jains, a majority (61%) say they are unwilling to have neighbors from at least one of these groups, including 54% who would not accept a Muslim neighbor, although nearly all Jains (92%) say they would be willing to accept a Hindu neighbor.

Indians, then, simultaneously express enthusiasm for religious tolerance and a consistent preference for keeping their religious communities in segregated spheres – they live together separately . These two sentiments may seem paradoxical, but for many Indians they are not.

Indeed, many take both positions, saying it is important to be tolerant of others and expressing a desire to limit personal connections across religious lines. Indians who favor a religiously segregated society also overwhelmingly emphasize religious tolerance as a core value. For example, among Hindus who say it is very important to stop the interreligious marriage of Hindu women, 82% also say that respecting other religions is very important to what it means to be Hindu. This figure is nearly identical to the 85% who strongly value religious tolerance among those who are not at all concerned with stopping interreligious marriage.

In other words, Indians’ concept of religious tolerance does not necessarily involve the mixing of religious communities. While people in some countries may aspire to create a “melting pot” of different religious identities, many Indians seem to prefer a country more like a patchwork fabric, with clear lines between groups.

One of these religious fault lines – the relationship between India’s Hindu majority and the country’s smaller religious communities – has particular relevance in public life, especially in recent years under the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the BJP is often described as promoting a Hindu nationalist ideology .

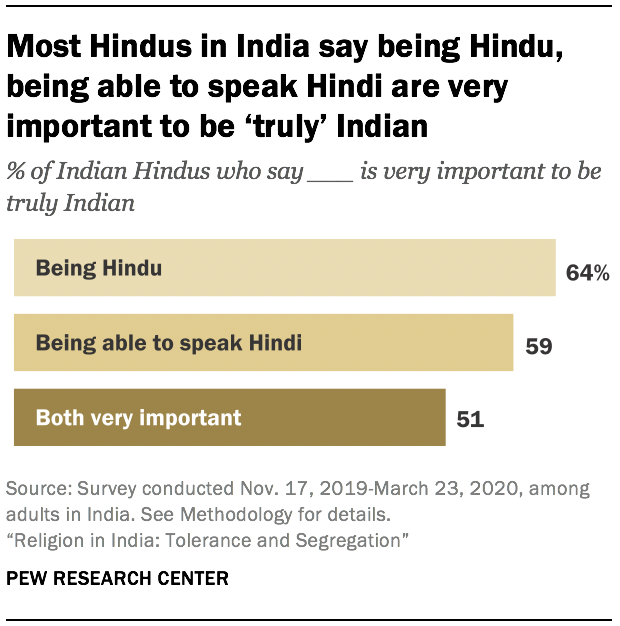

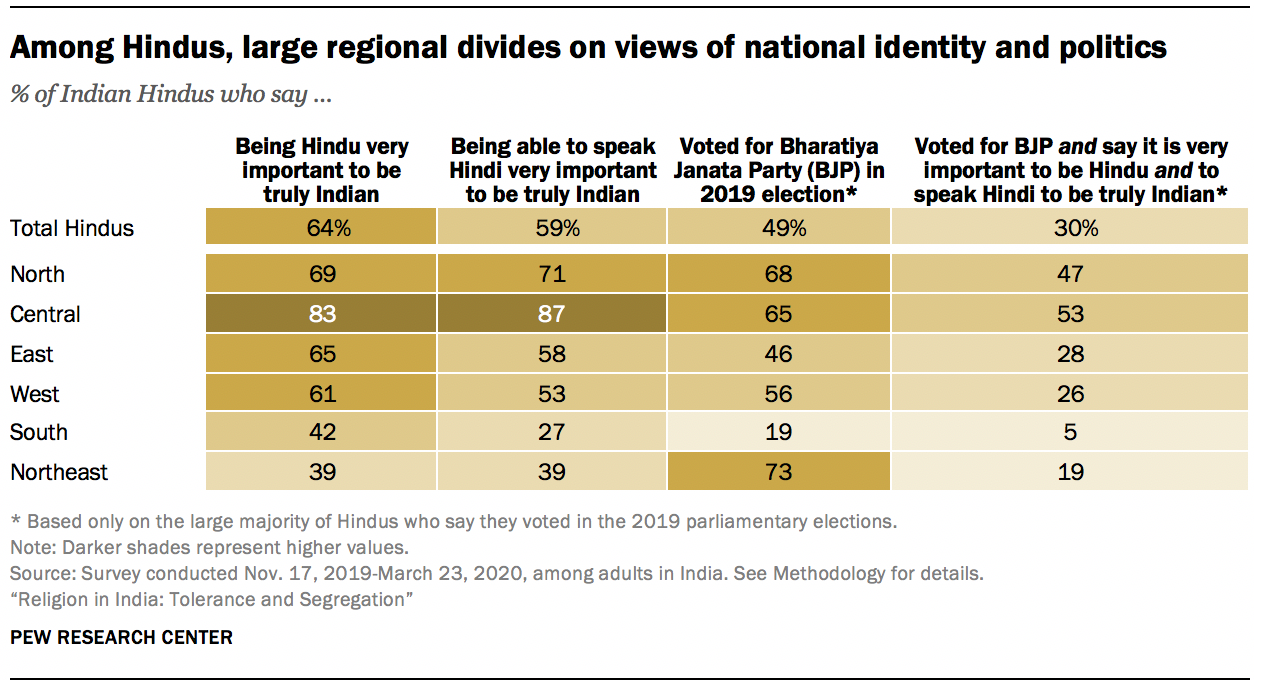

The survey finds that Hindus tend to see their religious identity and Indian national identity as closely intertwined: Nearly two-thirds of Hindus (64%) say it is very important to be Hindu to be “truly” Indian.

Most Hindus (59%) also link Indian identity with being able to speak Hindi – one of dozens of languages that are widely spoken in India. And these two dimensions of national identity – being able to speak Hindi and being a Hindu – are closely connected. Among Hindus who say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian, fully 80% also say it is very important to speak Hindi to be truly Indian.

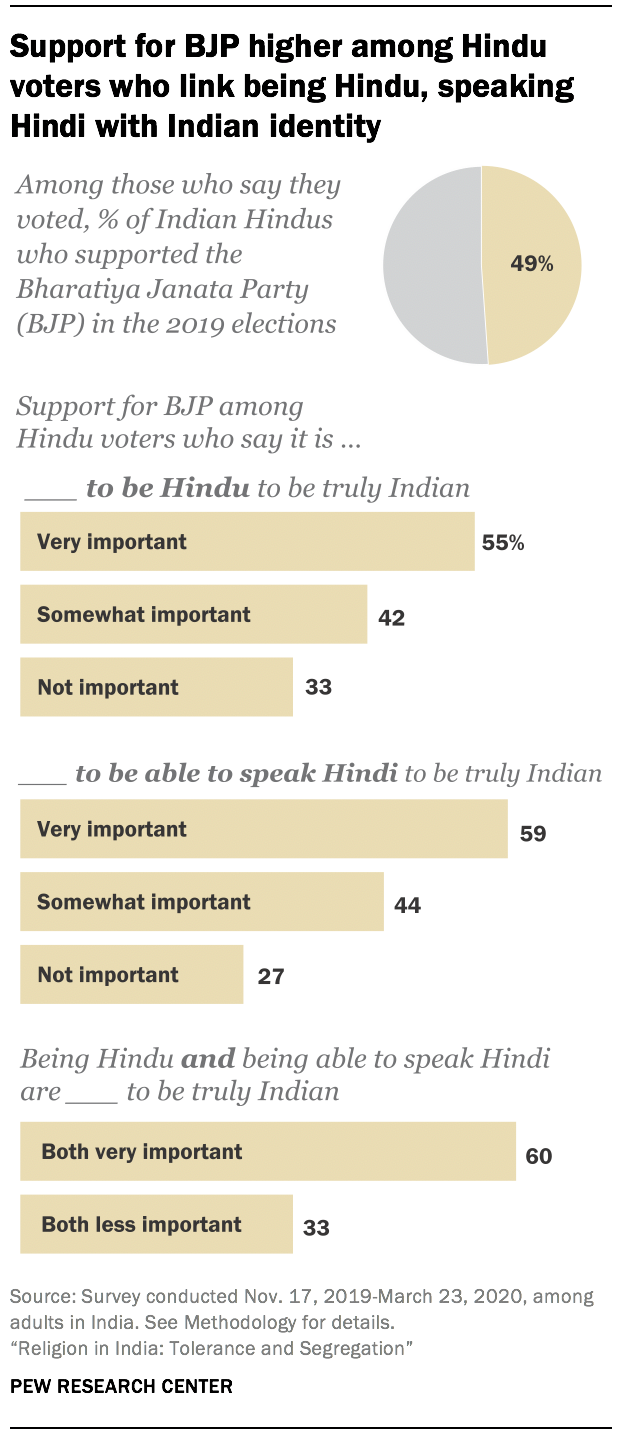

The BJP’s appeal is greater among Hindus who closely associate their religious identity and the Hindi language with being “truly Indian.” In the 2019 national elections, 60% of Hindu voters who think it is very important to be Hindu and to speak Hindi to be truly Indian cast their vote for the BJP, compared with only a third among Hindu voters who feel less strongly about both these aspects of national identity.

Overall, among those who voted in the 2019 elections, three-in-ten Hindus take all three positions: saying it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian; saying the same about speaking Hindi; and casting their ballot for the BJP.

These views are considerably more common among Hindus in the largely Hindi-speaking Northern and Central regions of the country, where roughly half of all Hindu voters fall into this category, compared with just 5% in the South.

Whether Hindus who meet all three of these criteria qualify as “Hindu nationalists” may be debated, but they do express a heightened desire for maintaining clear lines between Hindus and other religious groups when it comes to whom they marry, who their friends are and whom they live among. For example, among Hindu BJP voters who link national identity with both religion and language, 83% say it is very important to stop Hindu women from marrying into another religion, compared with 61% among other Hindu voters.

This group also tends to be more religiously observant: 95% say religion is very important in their lives, and roughly three-quarters say they pray daily (73%). By comparison, among other Hindu voters, a smaller majority (80%) say religion is very important in their lives, and about half (53%) pray daily.

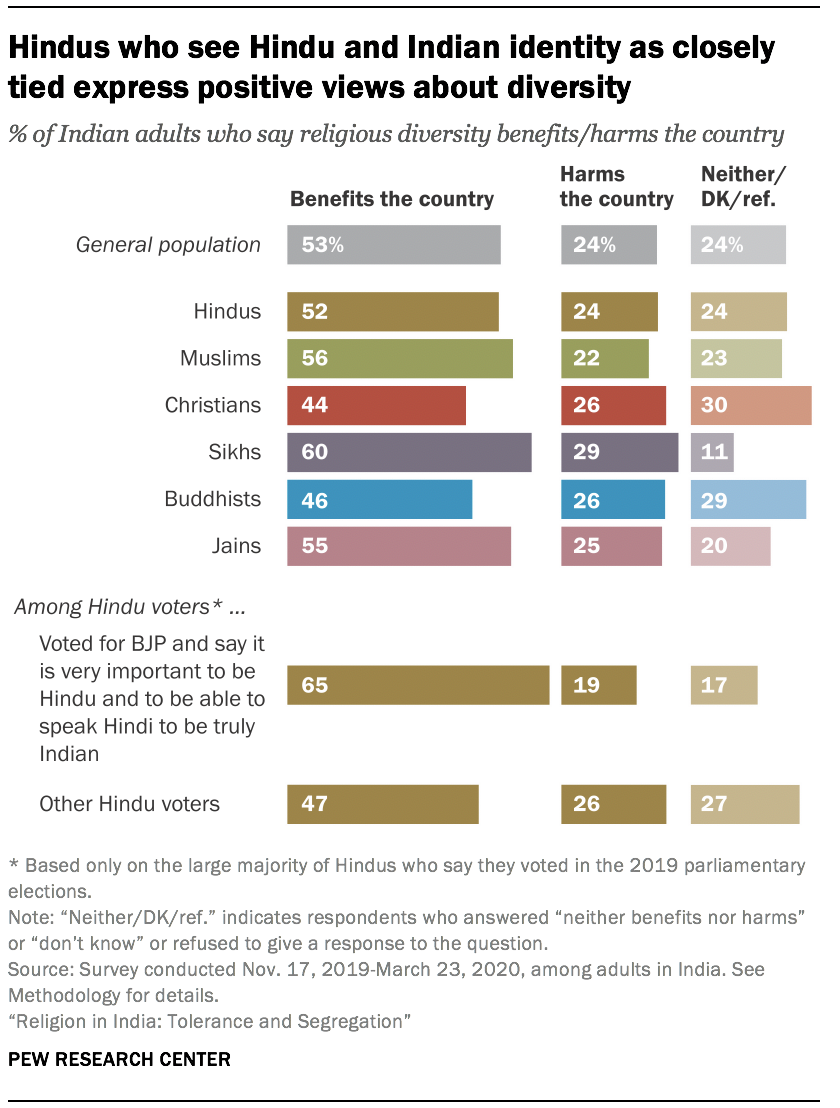

Even though Hindu BJP voters who link national identity with religion and language are more inclined to support a religiously segregated India, they also are more likely than other Hindu voters to express positive opinions about India’s religious diversity. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of this group – Hindus who say that being a Hindu and being able to speak Hindi are very important to be truly Indian and who voted for the BJP in 2019 – say religious diversity benefits India, compared with about half (47%) of other Hindu voters.

This finding suggests that for many Hindus, there is no contradiction between valuing religious diversity (at least in principle) and feeling that Hindus are somehow more authentically Indian than fellow citizens who follow other religions.

Among Indians overall, there is no overwhelming consensus on the benefits of religious diversity. On balance, more Indians see diversity as a benefit than view it as a liability for their country: Roughly half (53%) of Indian adults say India’s religious diversity benefits the country, while about a quarter (24%) see diversity as harmful, with similar figures among both Hindus and Muslims. But 24% of Indians do not take a clear position either way – they say diversity neither benefits nor harms the country, or they decline to answer the question. (See Chapter 2 for a discussion of attitudes toward diversity.)

India’s Muslim community, the second-largest religious group in the country, historically has had a complicated relationship with the Hindu majority. The two communities generally have lived peacefully side by side for centuries, but their shared history also is checkered by civil unrest and violence. Most recently, while the survey was being conducted, demonstrations broke out in parts of New Delhi and elsewhere over the government’s new citizenship law , which creates an expedited path to citizenship for immigrants from some neighboring countries – but not Muslims.

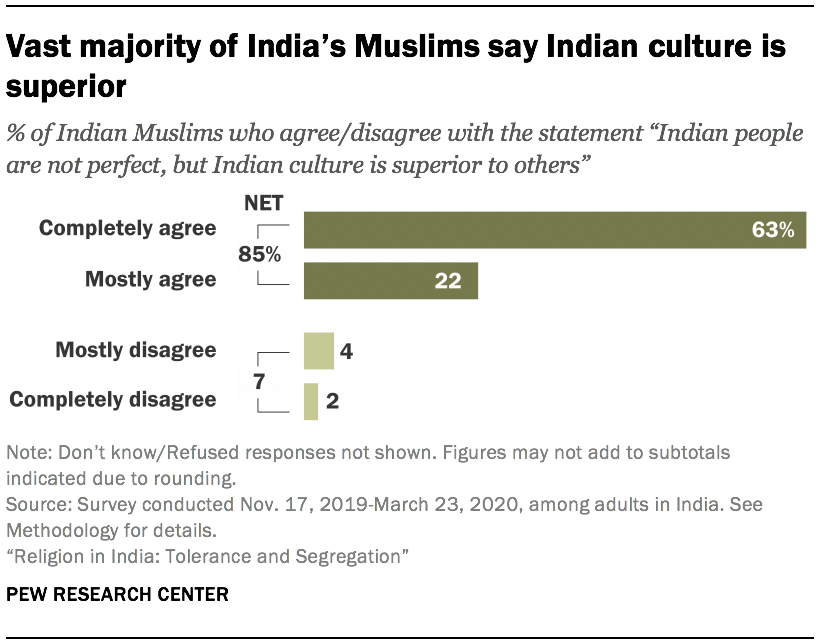

Today, India’s Muslims almost unanimously say they are very proud to be Indian (95%), and they express great enthusiasm for Indian culture: 85% agree with the statement that “Indian people are not perfect, but Indian culture is superior to others.”

Relatively few Muslims say their community faces “a lot” of discrimination in India (24%). In fact, the share of Muslims who see widespread discrimination against their community is similar to the share of Hindus who say Hindus face widespread religious discrimination in India (21%). (See Chapter 1 for a discussion of attitudes on religious discrimination.)

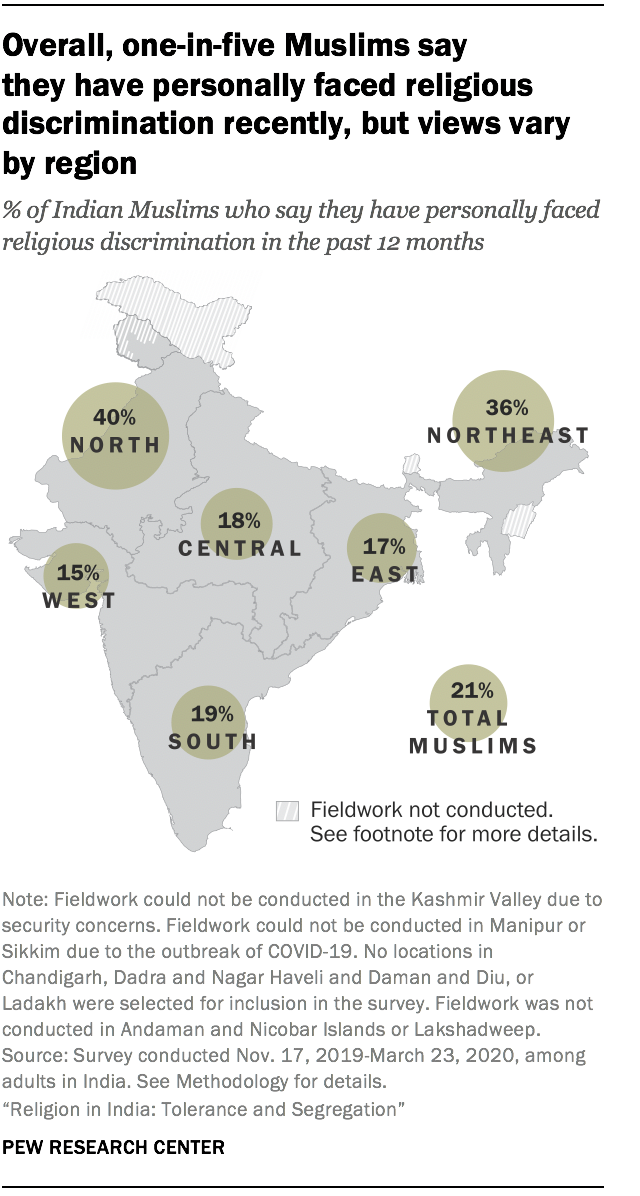

But personal experiences with discrimination among Muslims vary quite a bit regionally. Among Muslims in the North, 40% say they personally have faced religious discrimination in the last 12 months – much higher levels than reported in most other regions.

In addition, most Muslims across the country (65%), along with an identical share of Hindus (65%), see communal violence as a very big national problem. (See Chapter 1 for a discussion of Indians’ attitudes toward national problems.)

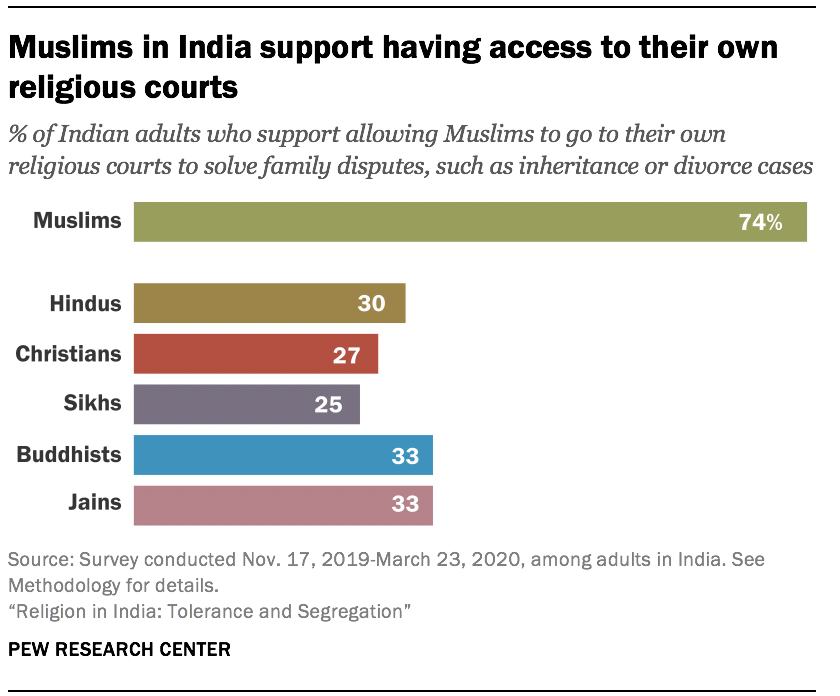

Like Hindus, Muslims prefer to live religiously segregated lives – not just when it comes to marriage and friendships, but also in some elements of public life. In particular, three-quarters of Muslims in India (74%) support having access to the existing system of Islamic courts, which handle family disputes (such as inheritance or divorce cases), in addition to the secular court system.

Muslims’ desire for religious segregation does not preclude tolerance of other groups – again similar to the pattern seen among Hindus. Indeed, a majority of Muslims who favor separate religious courts for their community say religious diversity benefits India (59%), compared with somewhat fewer of those who oppose religious courts for Muslims (50%).

Sidebar: Islamic courts in India

Since 1937, India’s Muslims have had the option of resolving family and inheritance-related cases in officially recognized Islamic courts, known as dar-ul-qaza. These courts are overseen by religious magistrates known as qazi and operate under Shariah principles . For example, while the rules of inheritance for most Indians are governed by the Indian Succession Act of 1925 and the Hindu Succession Act of 1956 (amended in 2005), Islamic inheritance practices differ in some ways, including who can be considered an heir and how much of the deceased person’s property they can inherit. India’s inheritance laws also take into account the differing traditions of other religious communities, such as Hindus and Christians, but their cases are handled in secular courts. Only the Muslim community has the option of having cases tried by a separate system of family courts. The decisions of the religious courts, however, are not legally binding , and the parties involved have the option of taking their case to secular courts if they are not satisfied with the decision of the religious court.

As of 2021, there are roughly 70 dar-ul-qaza in India. Most are in the states of Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh. Goa is the only state that does not recognize rulings by these courts, enforcing its own uniform civil code instead. Dar-ul-qaza are overseen by the All India Muslim Personal Law Board .

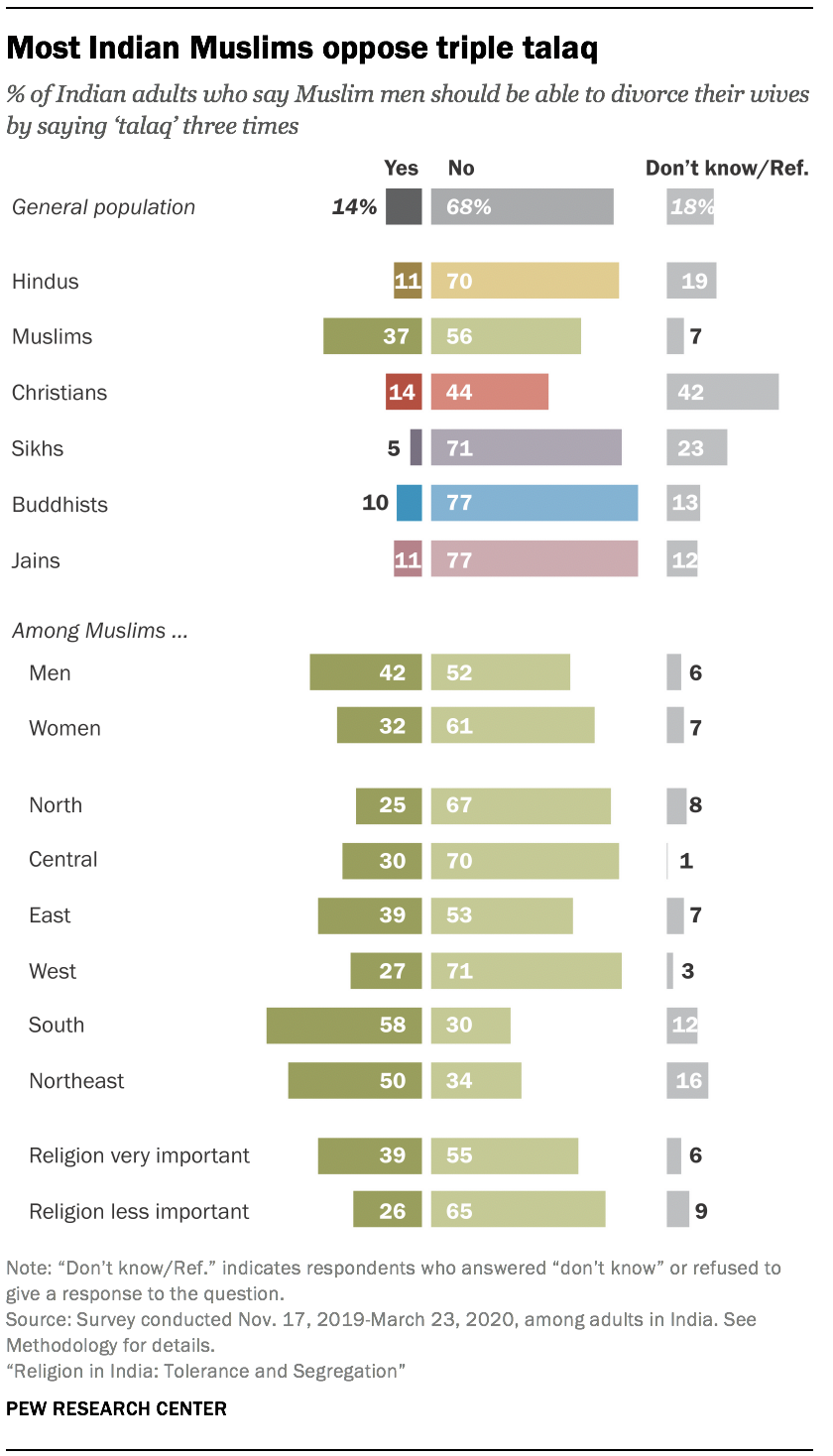

While these courts can grant divorces among Muslims, they are prohibited from approving divorces initiated through the practice known as triple talaq, in which a Muslim man instantly divorces his wife by saying the Arabic/Urdu word “talaq” (meaning “divorce”) three times. This practice was deemed unconstitutional by the Indian Supreme Court in 2017 and formally outlawed by the Lok Sabha, the lower house of India’s Parliament, in 2019. 1

Recent debates have emerged around Islamic courts. Some Indians have expressed concern that the rise of dar-ul-qaza could undermine the Indian judiciary, because a subset of the population is not bound to the same laws as everyone else. Others have argued that the rulings of Islamic courts are particularly unfair to women, although the prohibition of triple talaq may temper some of these criticisms. In its 2019 political manifesto , the BJP proclaimed a desire to create a national Uniform Civil Code, saying it would increase gender equality.

Some Indian commentators have voiced opposition to Islamic courts along with more broadly negative sentiments against Muslims, describing the rising numbers of dar-ul-qaza as the “Talibanization” of India , for example.

On the other hand, Muslim scholars have defended the dar-ul-qaza, saying they expedite justice because family disputes that would otherwise clog India’s courts can be handled separately, allowing the secular courts to focus their attention on other concerns.

Since 2018, the Hindu nationalist party Hindu Mahasabha (which does not hold any seats in Parliament) has tried to set up Hindu religious courts , known as Hindutva courts, aiming to play a role similar to dar-ul-qaza, only for the majority Hindu community. None of these courts have been recognized by the Indian government, and their rulings are not considered legally binding.

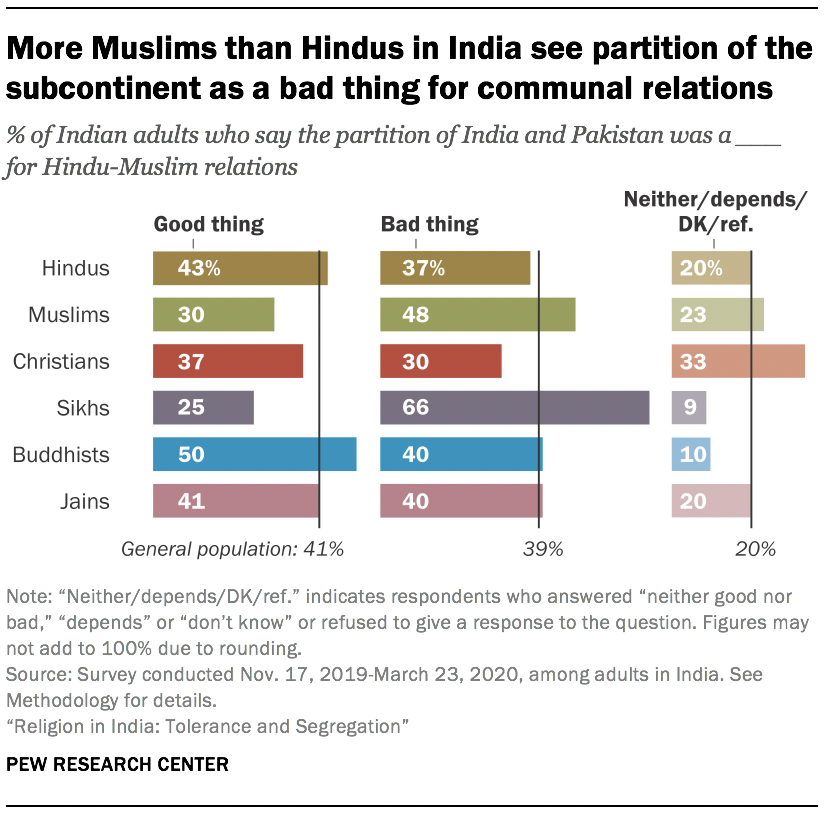

The seminal event in the modern history of Hindu-Muslim relations in the region was the partition of the subcontinent into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan at the end of the British colonial period in 1947. Partition remains one of the largest movements of people across borders in recorded history, and in both countries the carving of new borders was accompanied by violence, rioting and looting .

More than seven decades later, the predominant view among Indian Muslims is that the partition of the subcontinent was “a bad thing” for Hindu-Muslim relations. Nearly half of Muslims say Partition hurt communal relations with Hindus (48%), while fewer say it was a good thing for Hindu-Muslim relations (30%). Among Muslims who prefer more religious segregation – that is, who say they would not accept a person of a different faith as a neighbor – an even higher share (60%) say Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations.

Sikhs, whose homeland of Punjab was split by Partition, are even more likely than Muslims to say Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations: Two-thirds of Sikhs (66%) take this position. And Sikhs ages 60 and older, whose parents most likely lived through Partition, are more inclined than younger Sikhs to say the partition of the country was bad for communal relations (74% vs. 64%).

While Sikhs and Muslims are more likely to say Partition was a bad thing than a good thing, Hindus lean in the opposite direction: 43% of Hindus say Partition was beneficial for Hindu-Muslim relations, while 37% see it as a bad thing.

Context for the survey

Interviews were conducted after the conclusion of the 2019 national parliamentary elections and after the revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status under the Indian Constitution. In December 2019, protests against the country’s new citizenship law broke out in several regions.

Fieldwork could not be conducted in the Kashmir Valley and a few districts elsewhere due to security concerns. These locations include some heavily Muslim areas, which is part of the reason why Muslims make up 11% of the survey’s total sample, while India’s adult population is roughly 13% Muslim, according to the most recent census data that is publicly available, from 2011. In addition, it is possible that in some other parts of the country, interreligious tensions over the new citizenship law may have slightly depressed participation in the survey by potential Muslim respondents.

Nevertheless, the survey’s estimates of religious beliefs, behaviors and attitudes can be reported with a high degree of confidence for India’s total population, because the number of people living in the excluded areas (Manipur, Sikkim, the Kashmir Valley and a few other districts) is not large enough to affect the overall results at the national level. About 98% of India’s total population had a chance of being selected for this survey.

Greater caution is warranted when looking at India’s Muslims separately, as a distinct population. The survey cannot speak to the experiences and views of Kashmiri Muslims. Still, the survey does represent the beliefs, behaviors and attitudes of around 95% of India’s overall Muslim population.

These are among the key findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted face-to-face nationally among 29,999 Indian adults. Local interviewers administered the survey between Nov. 17, 2019, and March 23, 2020, in 17 languages. The survey covered all states and union territories of India, with the exceptions of Manipur and Sikkim, where the rapidly developing COVID-19 situation prevented fieldwork from starting in the spring of 2020, and the remote territories of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep; these areas are home to about a quarter of 1% of the Indian population. The union territory of Jammu and Kashmir was covered by the survey, though no fieldwork was conducted in the Kashmir region itself due to security concerns.

This study, funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, is part of a larger effort by Pew Research Center to understand religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The Center previously has conducted religion-focused surveys across sub-Saharan Africa ; the Middle East-North Africa region and many other countries with large Muslim populations ; Latin America ; Israel ; Central and Eastern Europe ; Western Europe ; and the United States .

The rest of this Overview covers attitudes on five broad topics: caste and discrimination; religious conversion; religious observances and beliefs; how people define their religious identity, including what kind of behavior is considered acceptable to be a Hindu or a Muslim; and the connection between economic development and religious observance.

Caste is another dividing line in Indian society, and not just among Hindus

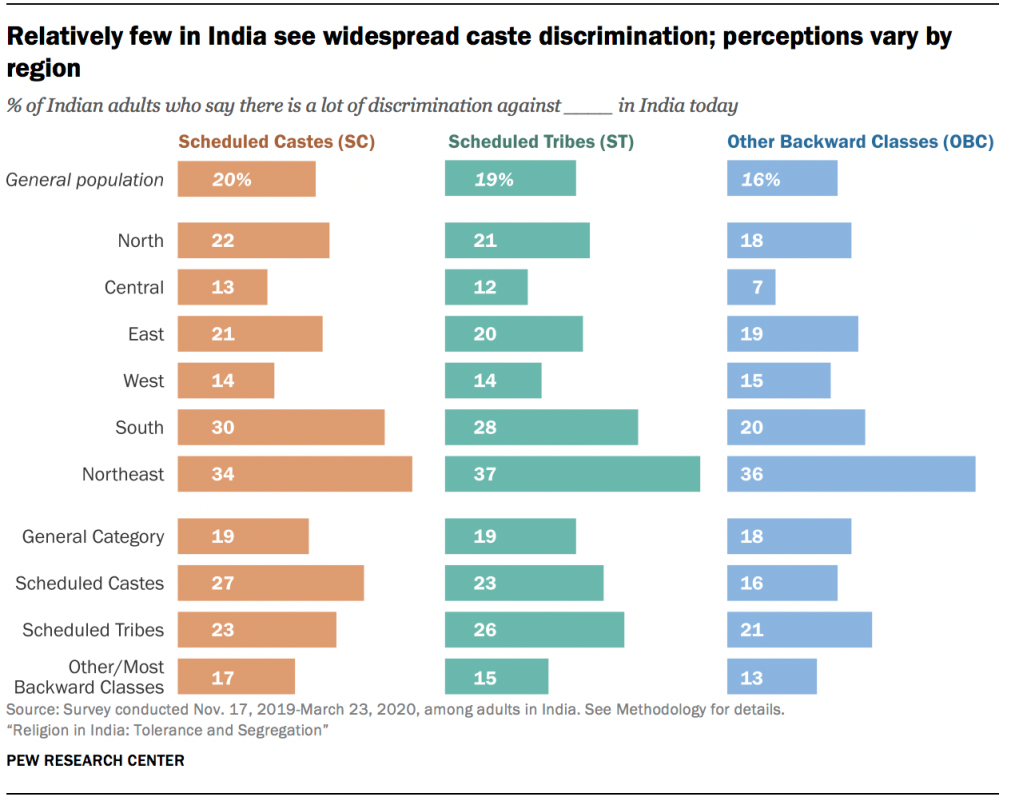

Religion is not the only fault line in Indian society. In some regions of the country, significant shares of people perceive widespread, caste-based discrimination.

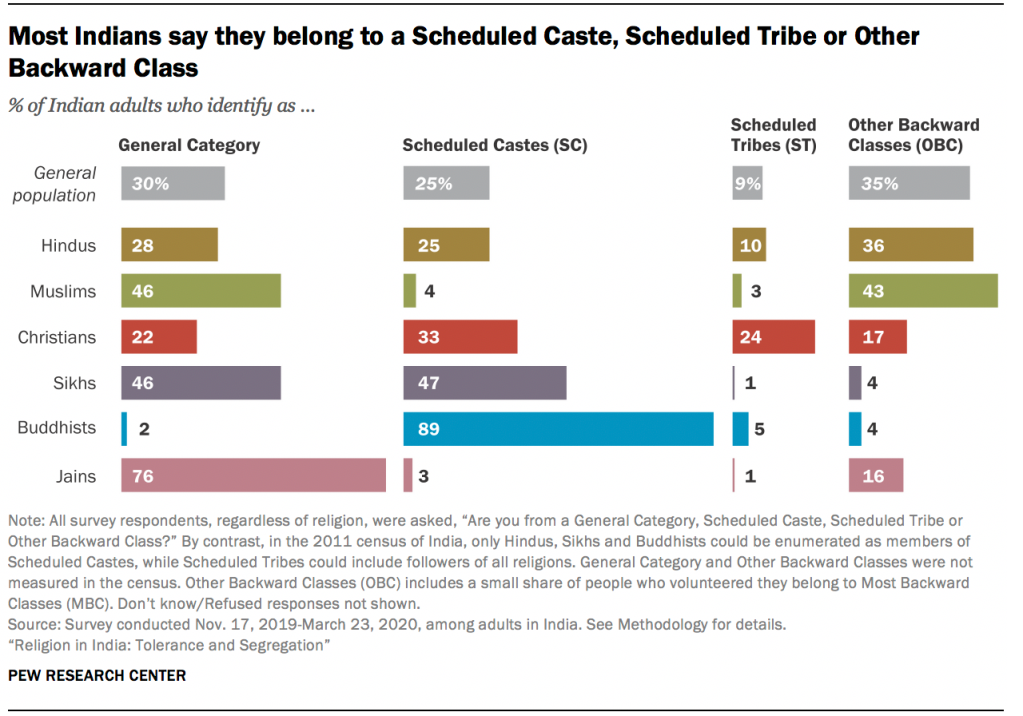

The caste system is an ancient social hierarchy based on occupation and economic status. People are born into a particular caste and tend to keep many aspects of their social life within its boundaries, including whom they marry. Even though the system’s origins are in historical Hindu writings , today Indians nearly universally identify with a caste, regardless of whether they are Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist or Jain.

Overall, the majority of Indian adults say they are a member of a Scheduled Caste (SC) – often referred to as Dalits (25%) – Scheduled Tribe (ST) (9%) or Other Backward Class (OBC) (35%). 2

Buddhists in India nearly universally identify themselves in these categories, including 89% who are Dalits (sometimes referred to by the pejorative term “untouchables”).

Members of SC/ST/OBC groups traditionally formed the lower social and economic rungs of Indian society, and historically they have faced discrimination and unequal economic opportunities . The practice of untouchability in India ostracizes members of many of these communities, especially Dalits, although the Indian Constitution prohibits caste-based discrimination, including untouchability, and in recent decades the government has enacted economic advancement policies like reserved seats in universities and government jobs for Dalits, Scheduled Tribes and OBC communities.

Roughly 30% of Indians do not belong to these protected groups and are classified as “General Category.” This includes higher castes such as Brahmins (4%), traditionally the priestly caste. Indeed, each broad category includes several sub-castes – sometimes hundreds – with their own social and economic hierarchies.

Three-quarters of Jains (76%) identify with General Category castes, as do 46% of both Muslims and Sikhs.

Caste-based discrimination, as well as the government’s efforts to compensate for past discrimination, are politically charged topics in India . But the survey finds that most Indians do not perceive widespread caste-based discrimination. Just one-in-five Indians say there is a lot of discrimination against members of SCs, while 19% say there is a lot of discrimination against STs and somewhat fewer (16%) see high levels of discrimination against OBCs. Members of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are slightly more likely than others to perceive widespread discrimination against their two groups. Still, large majorities of people in these categories do not think they face a lot of discrimination.

These attitudes vary by region, however. Among Southern Indians, for example, 30% see widespread discrimination against Dalits, compared with 13% in the Central part of the country. And among the Dalit community in the South, even more (43%) say their community faces a lot of discrimination, compared with 27% among Southern Indians in the General Category who say the Dalit community faces widespread discrimination in India.

A higher share of Dalits in the South and Northeast than elsewhere in the country say they, personally, have faced discrimination in the last 12 months because of their caste: 30% of Dalits in the South say this, as do 38% in the Northeast.

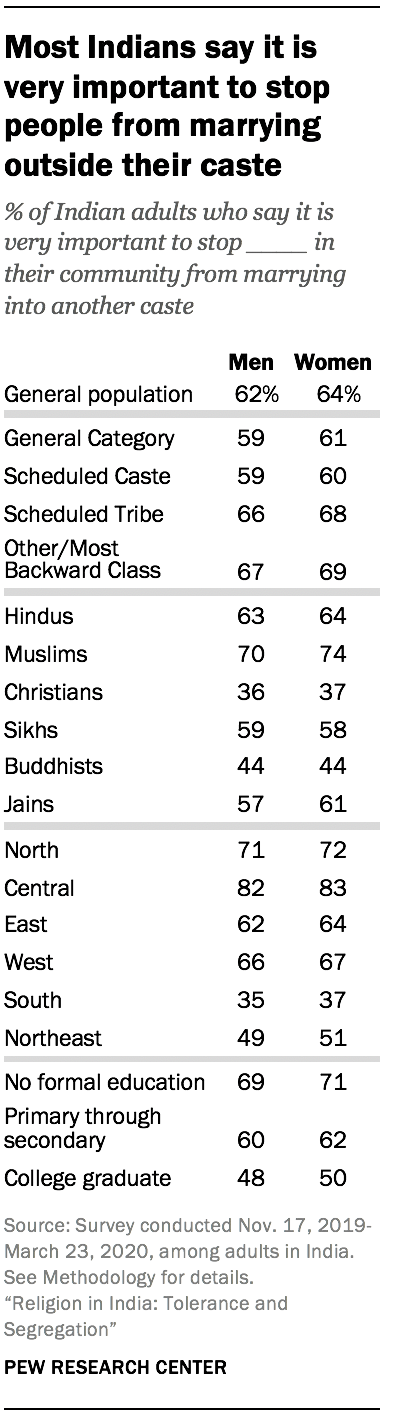

Although caste discrimination may not be perceived as widespread nationally, caste remains a potent factor in Indian society. Most Indians from other castes say they would be willing to have someone belonging to a Scheduled Caste as a neighbor (72%). But a similarly large majority of Indians overall (70%) say that most or all of their close friends share their caste. And Indians tend to object to marriages across caste lines, much as they object to interreligious marriages. 3

Overall, 64% of Indians say it is very important to stop women in their community from marrying into other castes, and about the same share (62%) say it is very important to stop men in their community from marrying into other castes. These figures vary only modestly across members of different castes. For example, nearly identical shares of Dalits and members of General Category castes say stopping inter-caste marriages is very important.

Majorities of Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Jains consider stopping inter-caste marriage of both men and women a high priority. By comparison, fewer Buddhists and Christians say it is very important to stop such marriages – although for majorities of both groups, stopping people from marrying outside their caste is at least “somewhat” important.

People surveyed in India’s South and Northeast see greater caste discrimination in their communities, and they also raise fewer objections to inter-caste marriages than do Indians overall. Meanwhile, college-educated Indians are less likely than those with less education to say stopping inter-caste marriages is a high priority. But, even within the most highly educated group, roughly half say preventing such marriages is very important. (See Chapter 4 for more analysis of Indians’ views on caste.)

In recent years, conversion of people belonging to lower castes (including Dalits) away from Hinduism – a traditionally non-proselytizing religion – to proselytizing religions, especially Christianity, has been a contentious political issue in India. As of early 2021, nine states have enacted laws against proselytism , and some previous surveys have shown that half of Indians support legal bans on religious conversions. 4

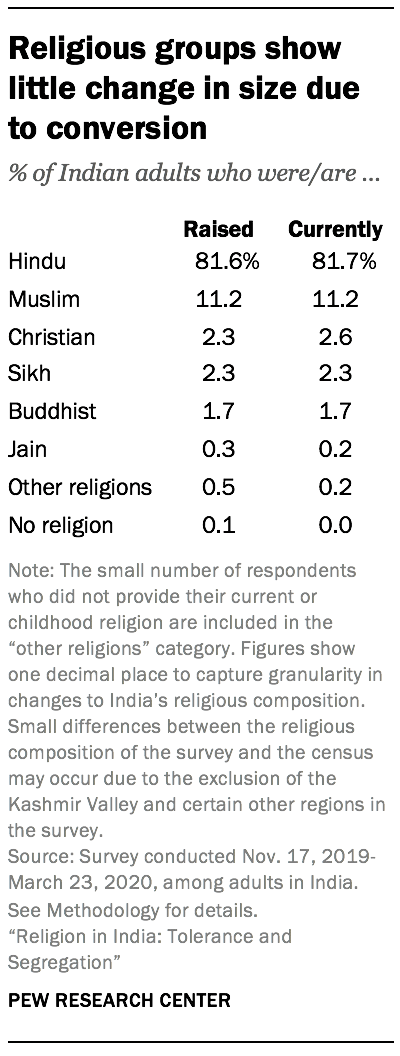

This survey, though, finds that religious switching, or conversion, has a minimal impact on the overall size of India’s religious groups. For example, according to the survey, 82% of Indians say they were raised Hindu, and a nearly identical share say they are currently Hindu, showing no net losses for the group through conversion to other religions. Other groups display similar levels of stability.

Changes in India’s religious landscape over time are largely a result of differences in fertility rates among religious groups, not conversion.

Respondents were asked two separate questions to measure religious switching: “What is your present religion, if any?” and, later in the survey, “In what religion were you raised, if any?” Overall, 98% of respondents give the same answer to both these questions.

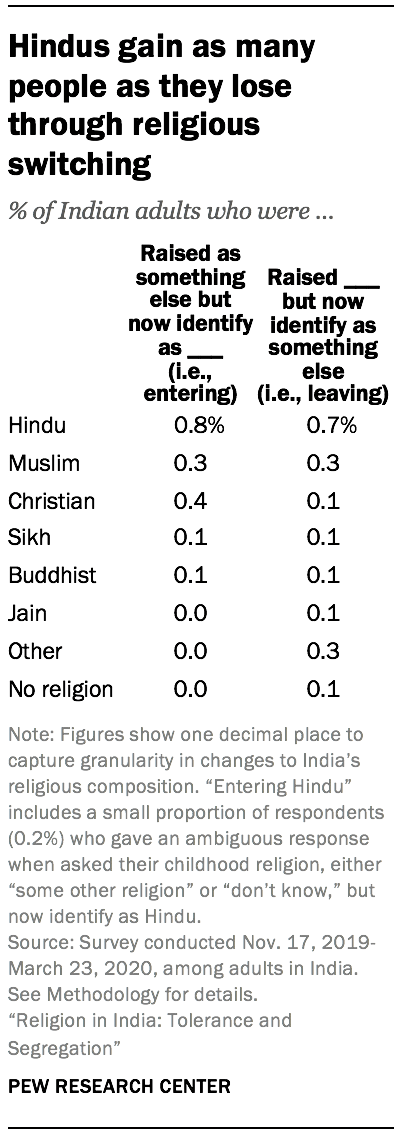

An overall pattern of stability in the share of religious groups is accompanied by little net gain from movement into, or out of, most religious groups. Among Hindus, for instance, any conversion out of the group is matched by conversion into the group: 0.7% of respondents say they were raised Hindu but now identify as something else, and although Hindu texts and traditions do not agree on any formal process for conversion into the religion, roughly the same share (0.8%) say they were not raised Hindu but now identify as Hindu. 5 Most of these new followers of Hinduism are married to Hindus.

Similarly, 0.3% of respondents have left Islam since childhood, matched by an identical share who say they were raised in other religions (or had no childhood religion) and have since become Muslim.

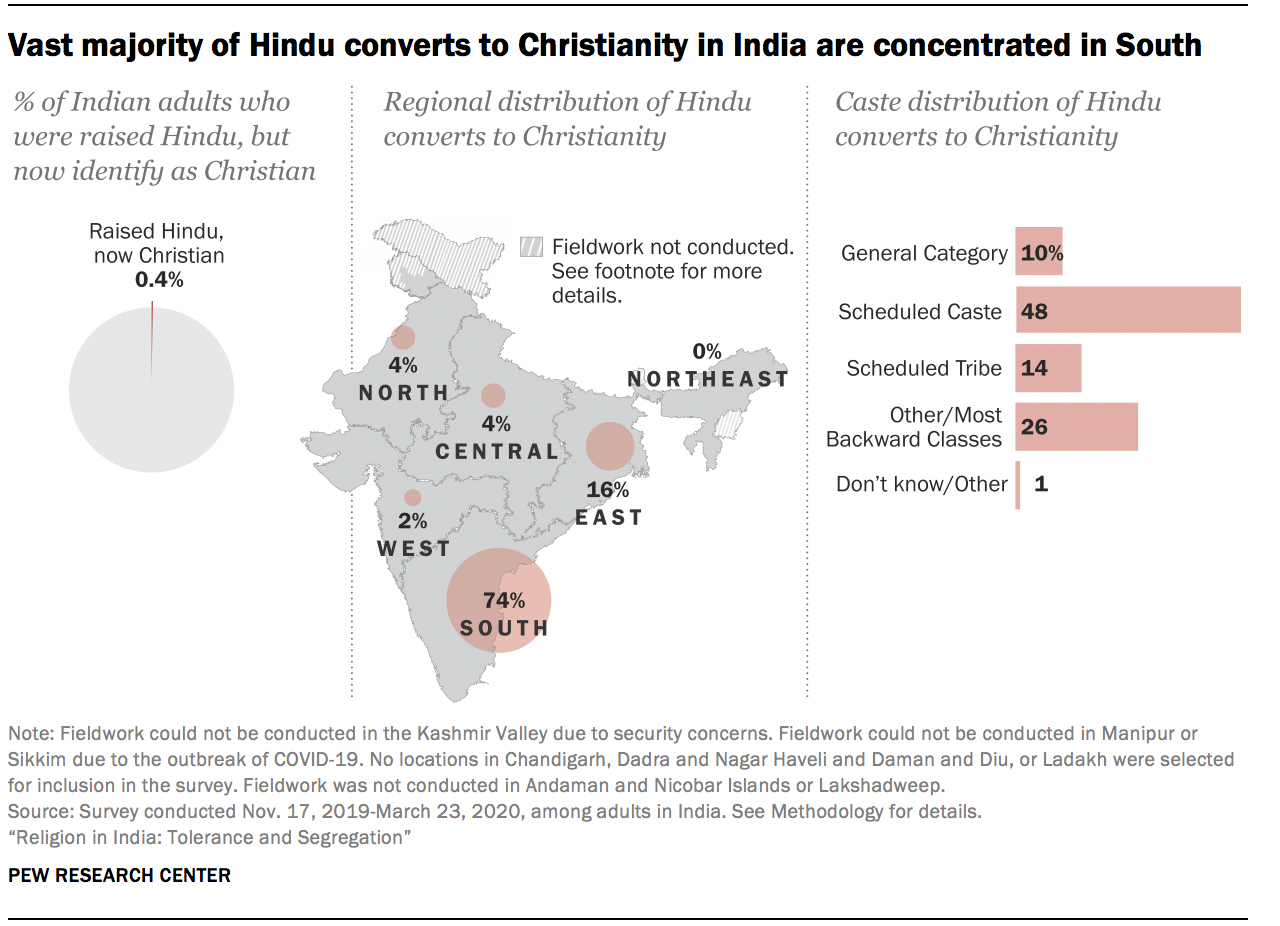

For Christians, however, there are some net gains from conversion: 0.4% of survey respondents are former Hindus who now identify as Christian, while 0.1% are former Christians.

Three-quarters of India’s Hindu converts to Christianity (74%) are concentrated in the Southern part of the country – the region with the largest Christian population. As a result, the Christian population of the South shows a slight increase within the lifetime of survey respondents: 6% of Southern Indians say they were raised Christian, while 7% say they are currently Christian.

Some Christian converts (16%) reside in the East as well (the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal); about two-thirds of all Christians in the East (64%) belong to Scheduled Tribes.

Nationally, the vast majority of former Hindus who are now Christian belong to Scheduled Castes (48%), Scheduled Tribes (14%) or Other Backward Classes (26%). And former Hindus are much more likely than the Indian population overall to say there is a lot of discrimination against lower castes in India. For example, nearly half of converts to Christianity (47%) say there is a lot of discrimination against Scheduled Castes in India, compared with 20% of the overall population who perceive this level of discrimination against Scheduled Castes. Still, relatively few converts say they, personally, have faced discrimination due to their caste in the last 12 months (12%).

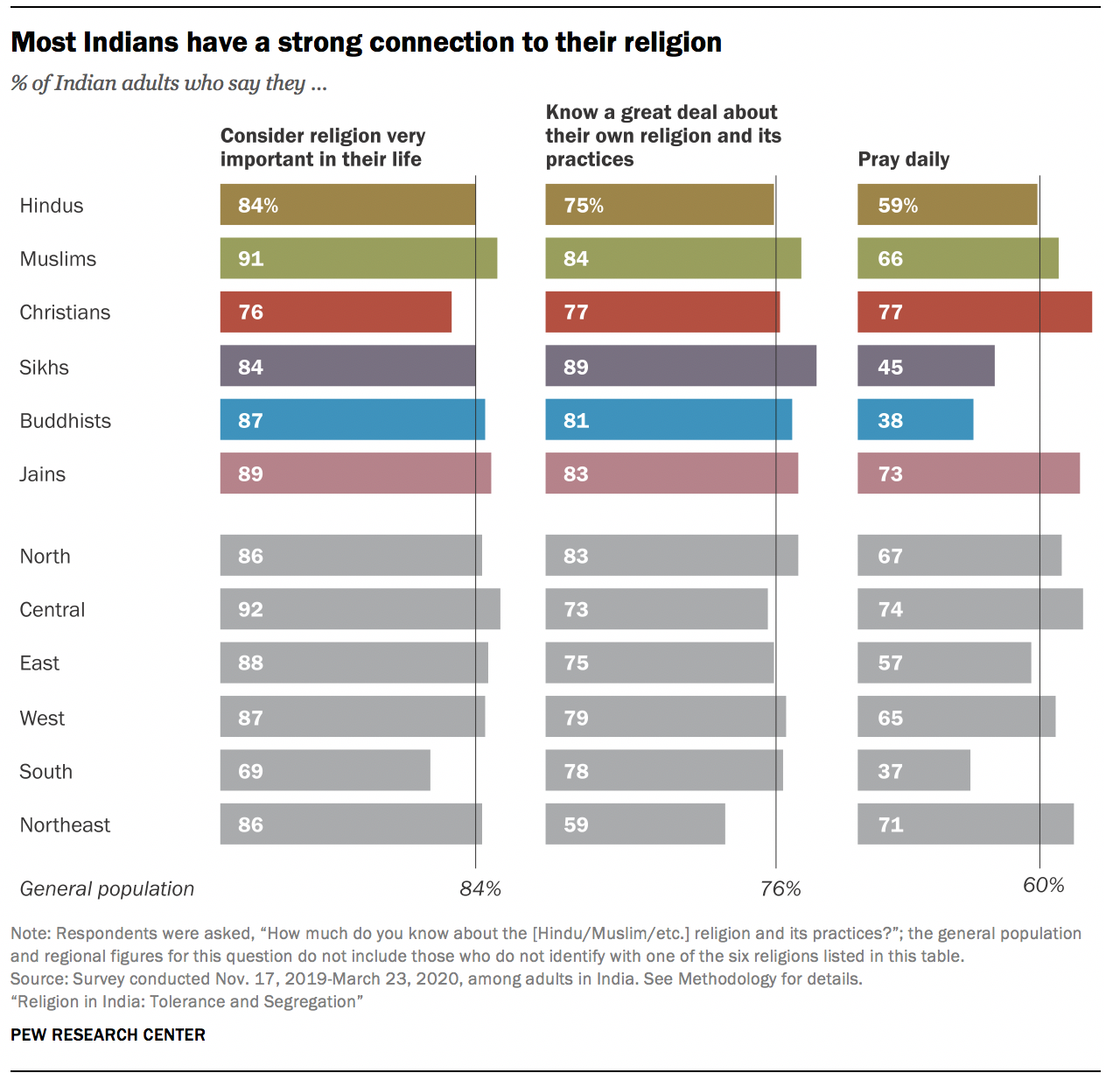

Though their specific practices and beliefs may vary, all of India’s major religious communities are highly observant by standard measures. For instance, the vast majority of Indians, across all major faiths, say that religion is very important in their lives. And at least three-quarters of each major religion’s followers say they know a great deal about their own religion and its practices. For example, 81% of Indian Buddhists claim a great deal of knowledge about the Buddhist religion and its practices.

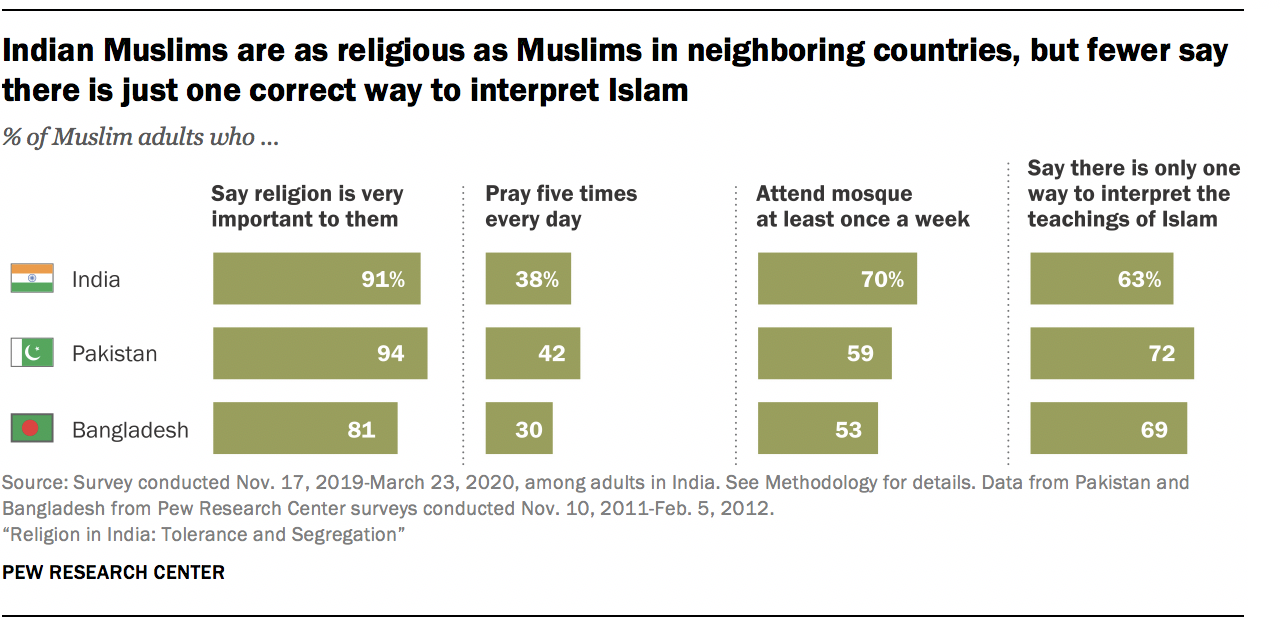

Indian Muslims are slightly more likely than Hindus to consider religion very important in their lives (91% vs. 84%). Muslims also are modestly more likely than Hindus to say they know a great deal about their own religion (84% vs. 75%).

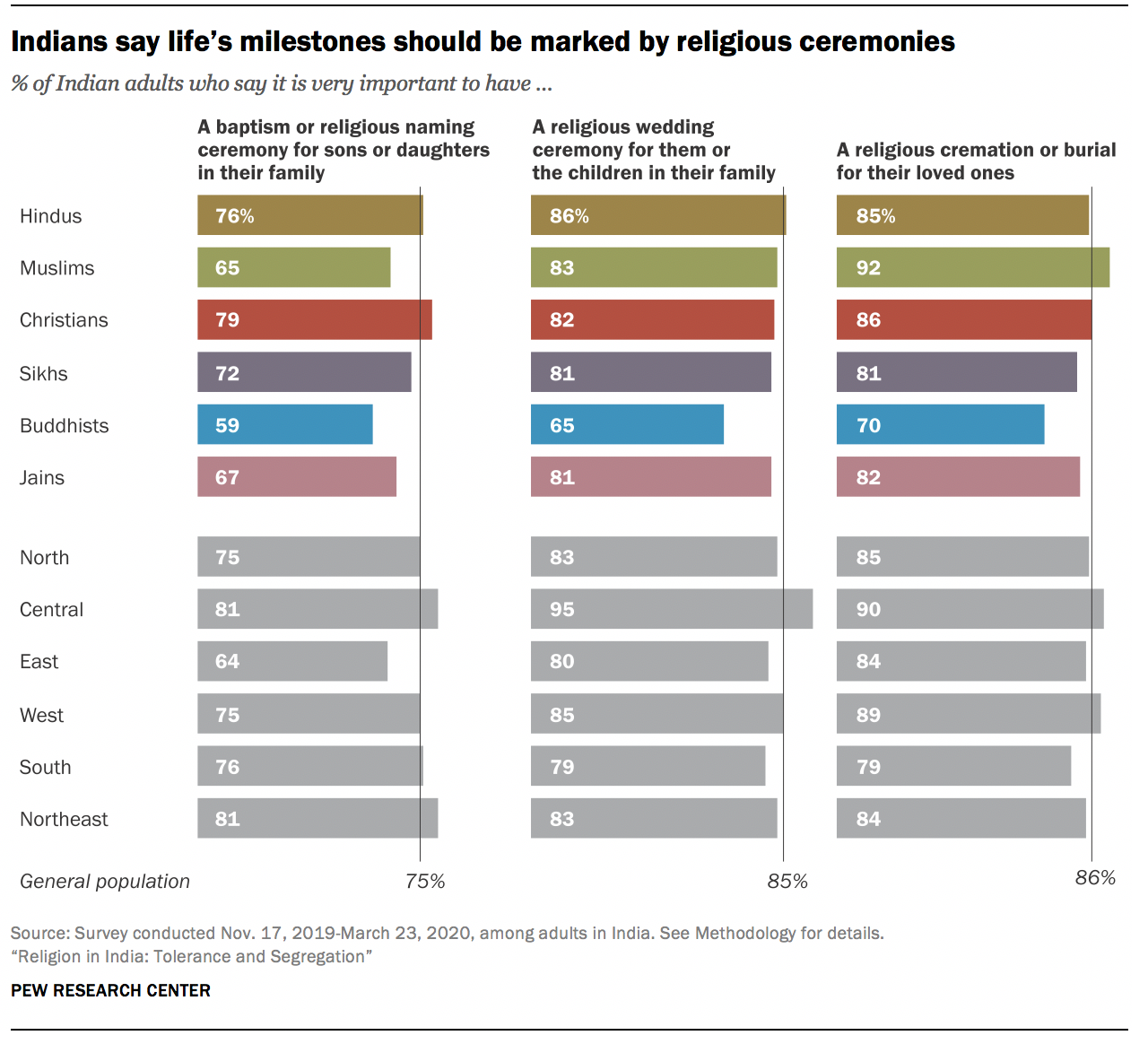

Significant portions of each religious group also pray daily, with Christians among the most likely to do so (77%) – even though Christians are the least likely of the six groups to say religion is very important in their lives (76%). Most Hindus and Jains also pray daily (59% and 73%, respectively) and say they perform puja daily (57% and 81%), either at home or at a temple. 6

Generally, younger and older Indians, those with different educational backgrounds, and men and women are similar in their levels of religious observance. South Indians are the least likely to say religion is very important in their lives (69%), and the South is the only region where fewer than half of people report praying daily (37%). While Hindus, Muslims and Christians in the South are all less likely than their counterparts elsewhere in India to say religion is very important to them, the lower rate of prayer in the South is driven mainly by Hindus: Three-in-ten Southern Hindus report that they pray daily (30%), compared with roughly two-thirds (68%) of Hindus in the rest of the country (see “ People in the South differ from rest of the country in their views of religion, national identity ” below for further discussion of religious differences in Southern India).

The survey also asked about three rites of passage: religious ceremonies for birth (or infancy), marriage and death. Members of all of India’s major religious communities tend to see these rites as highly important. For example, the vast majority of Muslims (92%), Christians (86%) and Hindus (85%) say it is very important to have a religious burial or cremation for their loved ones.

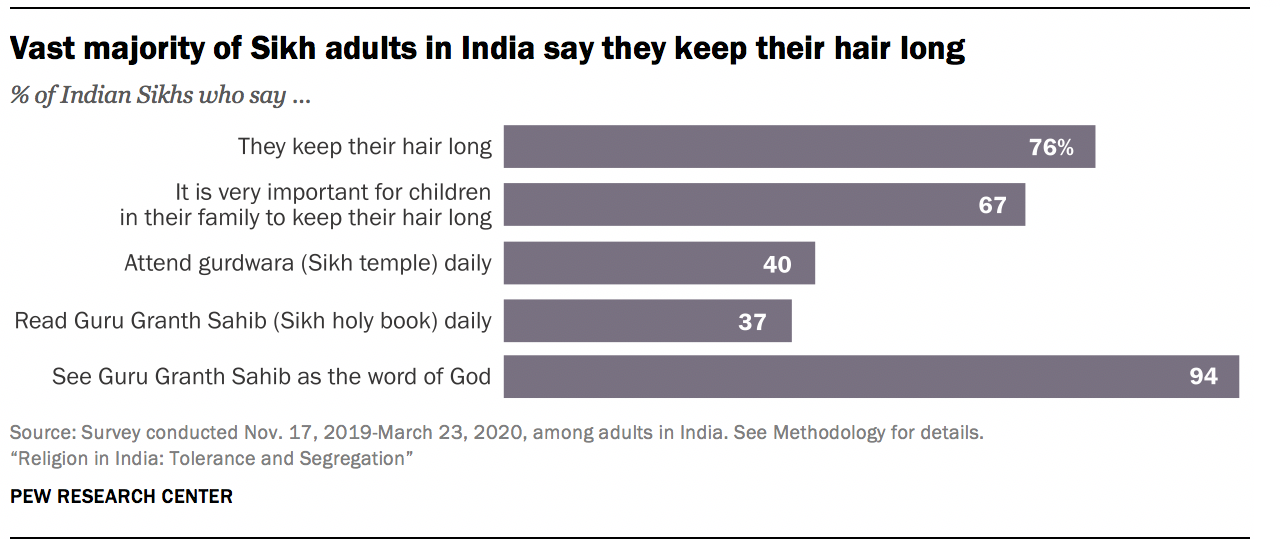

The survey also asked about practices specific to particular religions, such as whether people have received purification by bathing in holy bodies of water, like the Ganges River, a rite closely associated with Hinduism. About two-thirds of Hindus have done this (65%). Most Hindus also have holy basil (the tulsi plant) in their homes, as do most Jains (72% and 62%, respectively). And about three-quarters of Sikhs follow the Sikh practice of keeping their hair long (76%).

For more on religious practices across India’s religious groups, see Chapter 7 .

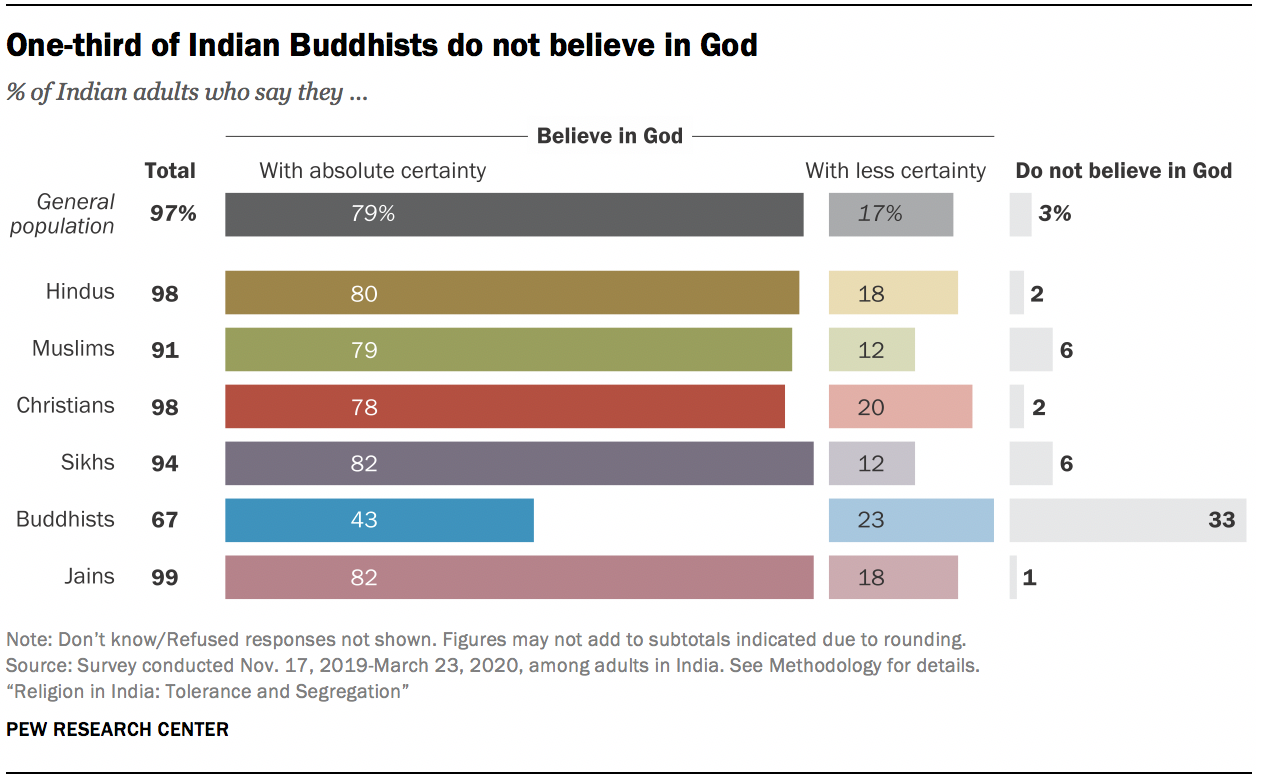

Nearly all Indians say they believe in God (97%), and roughly 80% of people in most religious groups say they are absolutely certain that God exists. The main exception is Buddhists, one-third of whom say they do not believe in God. Still, among Buddhists who do think there is a God, most say they are absolutely certain in this belief.

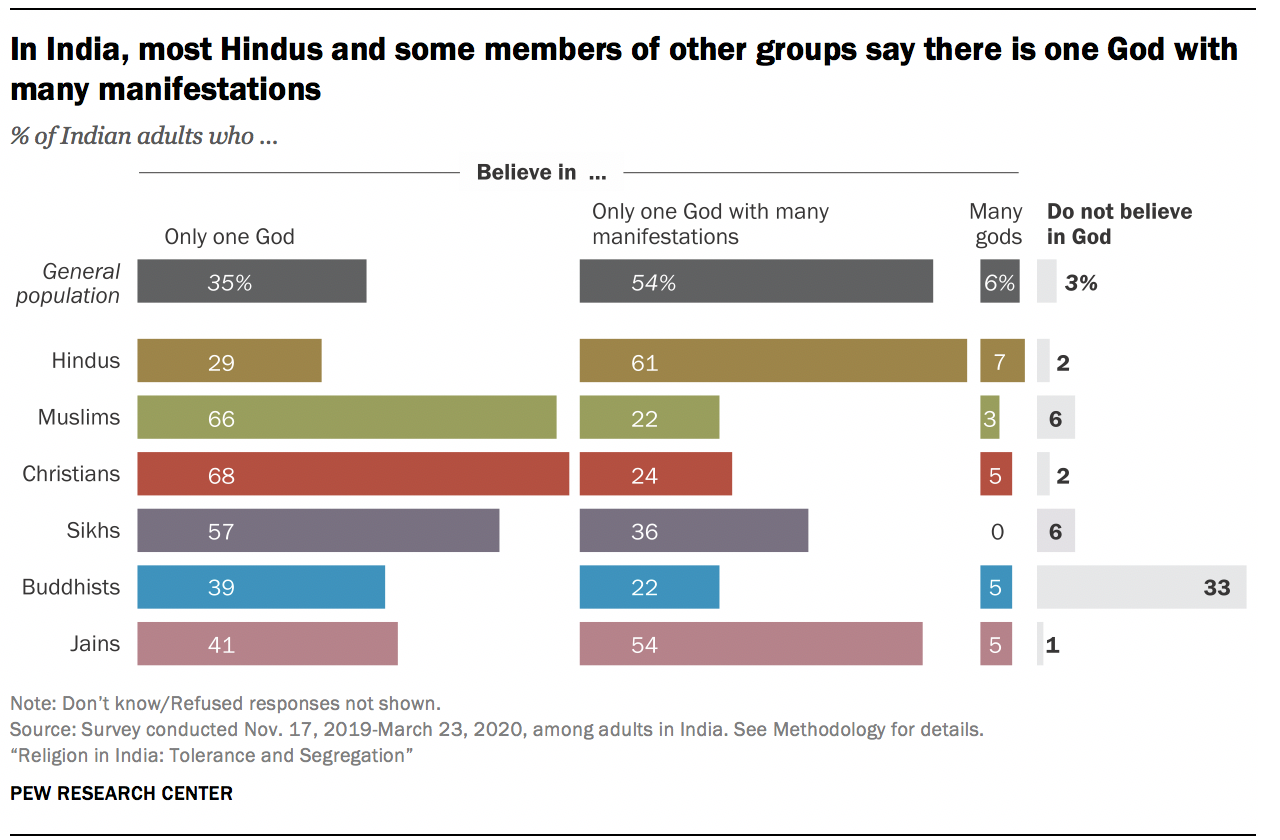

While belief in God is close to universal in India, the survey finds a wide range of views about the type of deity or deities that Indians believe in. The prevailing view is that there is one God “with many manifestations” (54%). But about one-third of the public says simply: “There is only one God” (35%). Far fewer say there are many gods (6%).

Even though Hinduism is sometimes referred to as a polytheistic religion , very few Hindus (7%) take the position that there are multiple gods. Instead, the most common position among Hindus (as well as among Jains) is that there is “only one God with many manifestations” (61% among Hindus and 54% among Jains).

Among Hindus, those who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than other Hindus to believe in one God with many manifestations (63% vs. 50%) and less likely to say there are many gods (6% vs. 12%).

By contrast, majorities of Muslims, Christians and Sikhs say there is only one God. And among Buddhists, the most common response is also a belief in one God. Among all these groups, however, about one-in-five or more say God has many manifestations, a position closer to their Hindu compatriots’ concept of God.

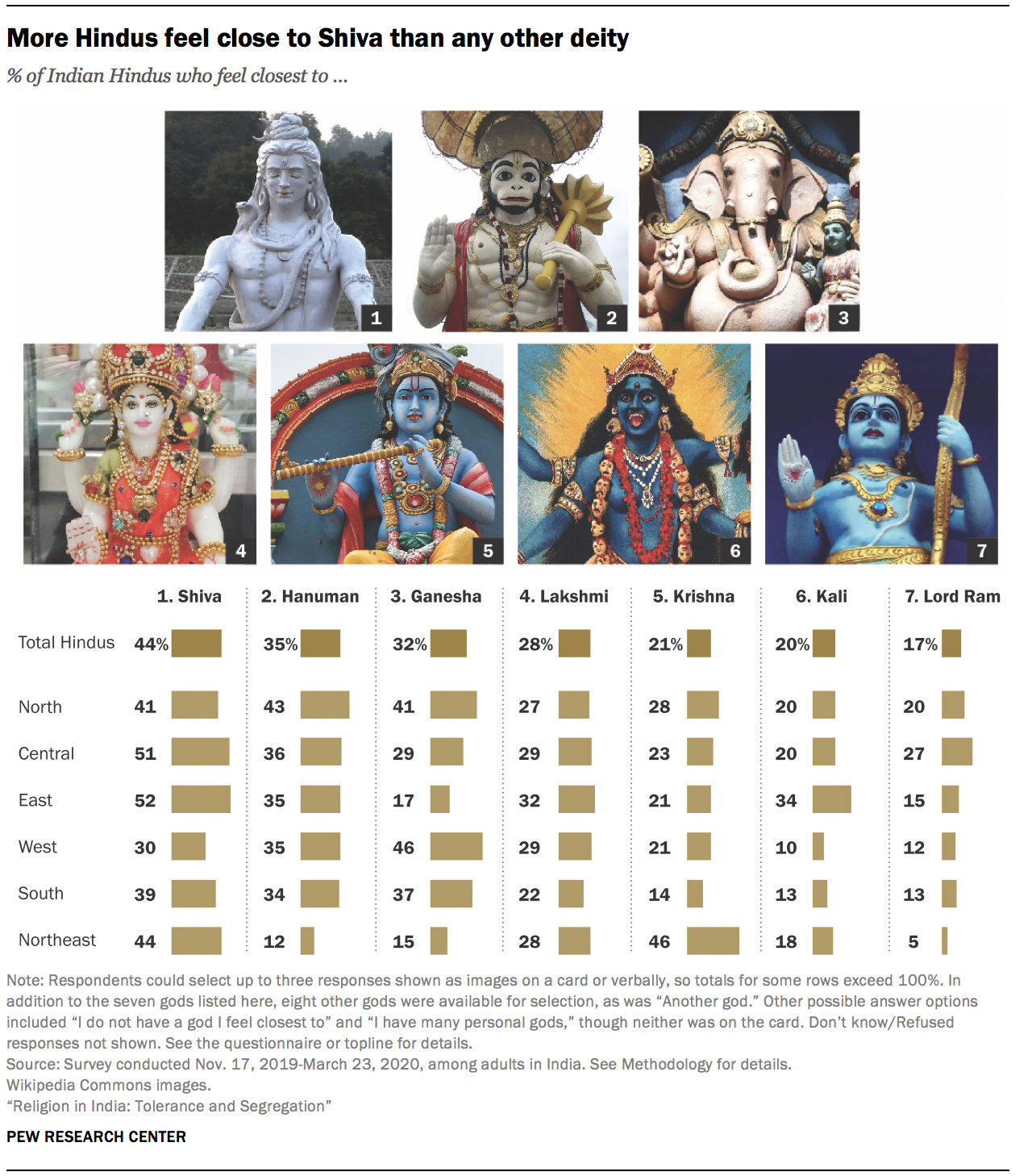

Most Hindus feel close to multiple gods, but Shiva, Hanuman and Ganesha are most popular

Traditionally, many Hindus have a “personal god,” or ishta devata: A particular god or goddess with whom they feel a personal connection. The survey asked all Indian Hindus who say they believe in God which god they feel closest to – showing them 15 images of gods on a card as possible options – and the vast majority of Hindus selected more than one god or indicated that they have many personal gods (84%). 7 This is true not only among Hindus who say they believe in many gods (90%) or in one God with many manifestations (87%), but also among those who say there is only one God (82%).

The god that Hindus most commonly feel close to is Shiva (44%). In addition, about one-third of Hindus feel close to Hanuman or Ganesha (35% and 32%, respectively).

There is great regional variation in how close India’s Hindus feel to some gods. For example, 46% of Hindus in India’s West feel close to Ganesha, but only 15% feel this way in the Northeast. And 46% of Hindus in the Northeast feel close to Krishna, while just 14% in the South say the same.

Feelings of closeness for Lord Ram are especially strong in the Central region (27%), which includes what Hindus claim is his ancient birthplace , Ayodhya. The location in Ayodhya where many Hindus believe Ram was born has been a source of controversy: Hindu mobs demolished a mosque on the site in 1992, claiming that a Hindu temple originally existed there. In 2019, the Indian Supreme Court ruled that the demolished mosque had been built on top of a preexisting non-Islamic structure and that the land should be given to Hindus to build a temple, with another location in the area given to the Muslim community to build a new mosque. (For additional findings on belief in God, see Chapter 12 .)

Sidebar: Despite economic advancement, few signs that importance of religion is declining

A prominent theory in the social sciences hypothesizes that as countries advance economically, their populations tend to become less religious, often leading to wider social change. Known as “secularization theory,” it particularly reflects the experience of Western European countries from the end of World War II to the present.

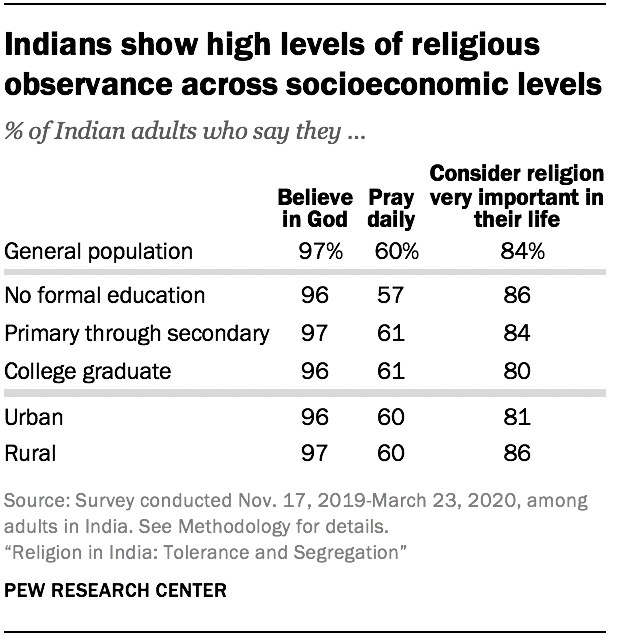

Despite rapid economic growth, India’s population so far shows few, if any, signs of losing its religion. For instance, both the Indian census and the new survey find virtually no growth in the minuscule share of people who claim no religious identity. And religion is prominent in the lives of Indians regardless of their socioeconomic status. Generally, across the country, there is little difference in personal religious observance between urban and rural residents or between those who are college educated versus those who are not. Overwhelming shares among all these groups say that religion is very important in their lives, that they pray regularly and that they believe in God.

Nearly all religious groups show the same patterns. The biggest exception is Christians, among whom those with higher education and those who reside in urban areas show somewhat lower levels of observance. For example, among Christians who have a college degree, 59% say religion is very important in their life, compared with 78% among those who have less education.

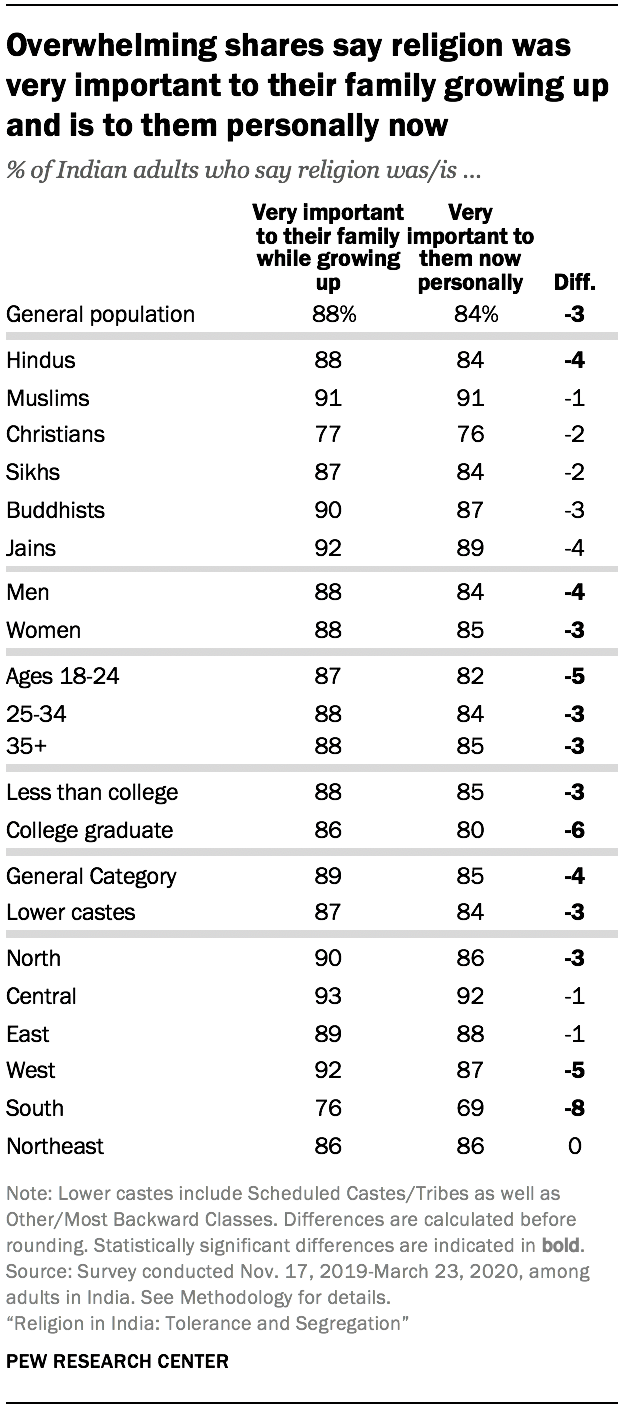

The survey does show a slight decline in the perceived importance of religion during the lifetime of respondents, though the vast majority of Indians indicate that religion remains central to their lives, and this is true among both younger and older adults.

Nearly nine-in-ten Indian adults say religion was very important to their family when they were growing up (88%), while a slightly lower share say religion is very important to them now (84%). The pattern is identical when looking only at India’s majority Hindu population. Among Muslims in India, the same shares say religion was very important to their family growing up and is very important to them now (91% each).

The states of Southern India (Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Puducherry, Tamil Nadu and Telangana) show the biggest downward trend in the perceived importance of religion over respondents’ lifetimes: 76% of Indians who live in the South say religion was very important to their family growing up, compared with 69% who say religion is personally very important to them now. Slight declines in the importance of religion, by this measure, also are seen in the Western part of the country (Goa, Gujarat and Maharashtra) and in the North, although large majorities in all regions of the country say religion is very important in their lives today.

Despite a strong desire for religious segregation, India’s religious groups share patriotic feelings, cultural values and some religious beliefs. For instance, overwhelming shares across India’s religious communities say they are very proud to be Indian, and most agree that Indian culture is superior to others.

Similarly, Indians of different religious backgrounds hold elders in high respect. For instance, nine-in-ten or more Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists and Jains say that respecting elders is very important to what being a member of their religious group means to them (e.g., for Hindus, it’s a very important part of their Hindu identity). Christians and Sikhs also overwhelmingly share this sentiment. And among all people surveyed in all six groups, three-quarters or more say that respecting elders is very important to being truly Indian.

Within all six religious groups, eight-in-ten or more also say that helping the poor and needy is a crucial part of their religious identity.

Beyond cultural parallels, many people mix traditions from multiple religions into their practices: As a result of living side by side for generations, India’s minority groups often engage in practices that are more closely associated with Hindu traditions than their own. For instance, many Muslim, Sikh and Christian women in India say they wear a bindi (a forehead marking, often worn by married women), even though putting on a bindi has Hindu origins.