- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The 10 best representations of God in culture

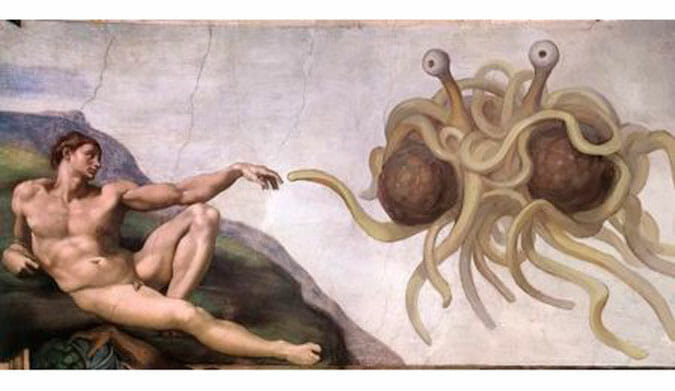

1 | the creation of adam.

Michelangelo (1511)

For its first 1,200 years, Christianity followed the line in John’s gospel that stated, “No one has ever seen God” and avoided portraying him. Relaxation of the rule came when he was shown as first a hand, then a face cloaked in cloud, but the Renaissance knew no such restraint. In one of his frescoed panels for the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam contains the most reproduced full-body image of God of all time. He is a benign, white-haired, bearded figure, clothed in a loose white robe, stretching out his finger to a naked Adam and so – as the Book of Genesis tells in the creation story – breathing life into him.

2 | Alanis Morissette

in Dogma (1999)

Casting women as God retains a strong contemporary kick when some patriarchal branches of Christianity still refuse to ordain females, but having the Canadian singer Alanis Morissette as the Almighty was more than a token gesture in Dogma , Kevin Smith’s irreverent comedy about two fallen angels trying to get back into heaven. Cradle Catholic Morissette, appearing in the wake of the global popularity of her album Jagged Little Pill , had already registered her interest in matters of faith in her song lyrics. Her female God is largely silent (a raven-haired, bewinged Alan Rickman does the talking for her), but she still manages to impose her will and perform the odd miracle.

3 | The Granton Star Cause

Irvine Welsh (1994)

In this lewd short story, part of The Acid House collection, Irvine Welsh – to the horror of many Christians – renders God as a foul-mouthed Edinburgh drunk, worn out by humanity’s insistence on blaming him for everything that goes wrong in their lives. Behind the effing and blinding and earthy setting, however, The Granton Star Cause poses serious questions about free will and the limits of God’s patience. After the success of the 1996 film adaptation of Welsh’s novel Trainspotting , The Acid House was also made into a film. When Channel 4 broadcast it in 1998, Mary Whitehouse attempted to have it banned on the grounds of blasphemy.

4 | The Ancient of Days

William Blake (1794)

The visionary poet, painter and printmaker created his own elaborate mythology, but this image – taken from a phrase in the Book of Daniel and traditionally seen in western Christianity as referring to the creative powers and perfection of God – still registers as a strikingly modern take on the divine more than two centuries later. A watercolour etching , originally for a cover illustration, the circle design with a crouching figure set against a cloud backdrop, retains its power to encapsulate a hard-to-define force that transcends the usual barriers around religion.

5 | Morgan Freeman

in Bruce Almighty (2003)

Having been fixed by Christianity in our collective imagination as an elderly white man, God always makes a bigger splash when portrayed by a black actor. And never more so than with Morgan Freeman ’s portrait in Bruce Almighty and its 2007 sequel Evan Almighty . This is a mellow God, wise enough to grant Jim Carrey’s Bruce Nolan his wish to play God, and then be there when he buckles under the strain of running the world. Freeman’s award-winning role is helped along mightily by him having the sort of voice that lends itself naturally to pronouncing infallibly.

6 | The Good Old Bad Old Days

The devil, it is said, has all the best tunes, but not, for once, in The Good Old Bad Old Days where God manages to hit a few high notes. This musical, written by Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley (the second Mr Joan Collins) in an attempt to repeat their earlier Broadway triumph of Stop the World, I Want to Get Off , had a decent six-month run in the West End. It is built around the conceit of an ageing God, exhausted by the devil’s tricks, singing of his plans to retire, but persuaded to stay on after reliving some of humanity’s happier historical tableaux.

7 | Sir Ralph Richardson

in Time Bandits (1981)

Everyone has their own image of God, some of them more akin to the cruel and vengeful character of the Old Testament narratives, but there is something seductively comforting about Ralph Richardson’s portrait of the Supreme Being in Terry Gilliam’s bizarre fantasy Time Bandits . He is your archetypal, utterly reasonable, besuited English civil servant of mature years, gently but firmly attempting to bring order and logic to a crazy universe.

8 | Brian Glover

in The Mysteries (1977)

God was rarely seen on stage before the modern period, save in the medieval mystery plays, which brought the Bible alive for illiterate folk in often raucous street performances. The opening part of the cycle was usually the creation and gave God got top billing. This tradition was maintained in The Mysteries , Bill Bryden’s award-laden version at the National Theatre in the early 1980s, where God was played by the bald Yorkshireman Brian Glover, putting the building blocks of the world into place from atop a forklift truck – a reference by the adaptor, Tony Harrison, to the habit of different medieval trade guilds taking ownership of each part of the mystery play cycle.

9 | Faust, parts one and two

Goethe (1772-1775)

Though God’s role is little more than a cameo in a work that took 60 years to complete and requires about 20 hours on stage if done in one sitting, it is undeniably a reassuring one. While Faust is busy succumbing to the wiles of the devilish Mephistopheles, God up in heaven, surrounded by angels, remains confident that his erring servant will eventually come good. And in part two – reputedly the harder section to perform – that confidence is eventually borne out, albeit only after this benign God has shown plenty of generosity of spirit and that most underrated of Christian virtues, forgiveness. “Man errs,” Goethe’s God concludes, “till he has ceased to strive.”

10 | Groucho Marx

Skidoo (1968)

In what was his last ever screen role, Groucho Marx plays a bonkers gangster boss called God, with near mystical powers, who is seduced by 60s counterculture, dons Hare Krishna robes and a Hawaiian-style flower necklace, and comes out as a hippy after having his first puff of marijuana. “Mmm, pumpkin,” he mutters as he reaches a spiritual high. Despite its stellar cast, Harry Nilsson soundtrack and Otto Preminger direction, Skidoo was panned on release – Marx labelled it “god-awful” and Preminger’s estate subsequently tried to bury it – but of late this oddball comedy has attracted a “so bad it’s good” cult following.

- The 10 best ...

- Michelangelo

- Morgan Freeman

- Alanis Morissette

- William Blake

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

- Our Ministry

- The Gap We See

- Partner with Us

- Newsletters

- Partner With Us

Visual Spirituality

L et's begin by unpacking what the second commandment actually says. When looking at Exodus 20:4 , we are confronted with two sets of English translations. Older versions, including the King James Version and the RSV, tend to stay close to the words of the Hebrew text. More recent versions, including the NIV and NRSV, focus instead on its intended meaning.

The key difference between these two sets rests on the translation of the Hebrew word pesel , coming from the root word pasal , meaning "to carve wood or stone." This meaning gave rise to the translation "graven image" in the first set of translations. Yet in Scripture, the term is never used for a two-dimensional image, but always for three-dimensional objects carved or chiseled out of wood or stone, with or without a gold or silver covering.

The key point is that the objects were always associated with idolatrous or superstitious practices. That is why almost all new translations have replaced the term "graven image" with "idol." This meaning is supported by the surrounding verses: "You shall have no other gods before me" (v. 3), and "You shall not bow down to them or worship them" (v. 5). Idols could be small and portable, such as the household gods that Rachel stole from her father ( Gen. 31:17-21 ), or large and lifesize, such as the statue Michal used to trick Saul's men into believing David was asleep in his bed ( 1 Sam. 19:13 ). Either way, God's prohibition against idols was both pertinent and necessary. Although the use of idols typified pagan cultures, many of God's people still clung to them.

In light of a better understanding of pesel and the second commandment's wider context, it should be clear that the injunction is not a blanket ban on representational imagery, as some forms of Judaism and Christianity (as well as Islam—witness the furor over the Muhammad cartoons) have suggested, thereby requiring all art to be restricted to abstract patterns and designs. Instead, it is a ban on images used as idols. This explains why God could instruct Moses to include such images as flowers, pomegranates, and winged angels in the design of the tabernacle.

We may also conclude that the second commandment does not forbid portrayals of God. The text is silent on this point. It is sometimes suggested that Deuteronomy 4:15-18 bans any visual representation of God, as it links the fact that the Israelites did not see any form of God when he spoke to them at Horeb with a warning against the creation of idols modeled on anything in creation. Yet this verse does not imply that we can never refer to God in terms of created phenomena.

Free Newsletters

Indeed, Jesus is the ultimate image—in Greek, eikon —of God ( Col. 1:15 ). And God reveals himself to us, whether as Father, Son, or Holy Spirit, by means of images deeply rooted in our creaturely experience: King and Servant, Judge and Comforter, Shepherd and Lamb, Fortress and Counselor, and so on. The sheer diversity of these images reminds us that we are never to confine God to just any one of them.

Since visual images grow out of our lived experience, they can enrich, supplement, and, at times, even correct our abstract and doctrinal conceptions of God. They can tangibly affect the way we relate to him. And there is no reason to assume that such images must be restricted to words. Visual art can play an important role.

In addition to the numerous paintings of Christ—and, more recently, films about him—in the history of Western art, depictions of God such as William Blake's God As an Architect (1794), Vincent van Gogh's The Sower with Setting Sun (1888), and Stanley Spencer's The Resurrection, Cookham (1923-7) all portray different aspects of God which can deepen our understanding of the richness of his being. And, in the same way that our verbal representations of God, including our theological conceptions, should be faithful to the way he has revealed himself in Scripture and in creation, our visual representations must also be faithful, even when imaginative.

As long as we do not treat any of these images as exhaustive representations of God or as objects of spiritual power in themselves, such that we cherish and yearn for them for their own sake, we may receive them with thanksgiving as a gift from the Creator of all creators. Let this be an invitation.

Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin teaches philosophical aesthetics at the Institute for Christian Studies in Toronto.

Copyright © 2006 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Passages mentioned in this article are available on this BibleGateway page .

Other Christianity Today articles on the power of images and worship include:

Reformed Protestants No Longer See Images as Idolatrous | The visual and the word go hand in hand as some pastors see possibility in connecting pictures with worship. (Dec. 6, 2004)

Grave Images | The photos from Abu Ghraib have reopened debate on the power of pictures. (June 21, 2004)

Wholly, Wholly, Wholly | Calvinists and conga drums in Grand Rapids: a report from the seventeenth annual Calvin Symposium on Worship and the Arts. (Feb. 02, 2004)

Image Is Everything | The Taliban's destruction of Buddhist statues is only the latest controversy over the Second Commandment. (April 6, 2001)

Earlier Good Question columns include:

The Gospel of Jesus Christ: An Evangelical Celebration" states that sincere worshipers of other religions will not be saved—does that also refer to Moses and other Old Testament faithful?

Christ commanded us not to judge others, but aren't there times when common sense or prudence requires it?

Why should church buildings get so much of the financial, physical, and social attention that is rightly due to the needs of Christians and others?

Where is heaven, and how will we experience it before the final resurrection?

Can I forgive those who have betrayed me if they are not repentant?

Are all sins weighed equally, or is one more important than another?

Why is the church against euthanasia in instances where people are in terrible pain?

What harm is there in achieving a higher state of consciousness through meditation?

Will we be vegetarians in the new heaven and earth as Adam and Eve were before the Fall?

Why doesn't God cure everyone who prays fervently for healing?

Does God need our help, love, and praise?

Are some people lost "just a little bit" in the same way that others are saved "only as through fire"?

Is Jesus Incarnate Forever?

What does Genesis mean by man being made in the image of God?

What's the difference between Christ's kingdom and paradise?

Is every believer guaranteed at least one spiritual gift?

What role does baptism play in faith and salvation?

How is it that not all prayers for the salvation of others are answered?

If God is in us, shouldn't it be easier to love one another?

What do we gain from a bodily resurrection?

What is the difference between the brain and the soul?

How can I reconcile my belief in the inerrancy of Scripture with comments in Bible translations that state that a particular verse is not 'in better manuscripts'?

Is there a biblical principle behind the punishment of those who break the law?

Is it unscriptural for a Christian to be cremated?

Won't heaven's joy be spoiled by our awareness of unsaved loved ones in hell?

Where exactly do "Oneness" Pentecostals stand in relation to orthodoxy?

Do a man and a woman become married after having sex or after exchanging vows?

How Do You Know That You Have Truly Forgiven Someone?

Who Are We to Judge?

Should We File Lawsuits?

Can We Expect God to Forgive Unbelievers Who 'Don't Know What They're Doing'?

Is the Stock Market Good Stewardship?

Is Satan Omnipresent?

Is Suicide Unforgivable?

Was Slavery God's Will?

A Little Wine for the Soul?

Should We All Speak in Tongues?

Did Jesus Really Descend to Hell?

Take, Eat—But How Often?

Is Christmas Pagan?

Are Christians Required to Tithe?

Have something to add about this? See something we missed? Share your feedback here .

Our digital archives are a work in progress. Let us know if corrections need to be made.

Recent Issues

Annual & Monthly subscriptions available.

- Print & Digital Issues of CT magazine

- Complete access to every article on ChristianityToday.com

- Unlimited access to 65+ years of CT’s online archives

- Member-only special issues

More from this Issue

Read these next.

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Issue Archives

- Member Benefits

- Give a Gift

Special Sections

- News & Reporting

- Español | All Languages

Topics & People

- Theology & Spirituality

- Church Life & Ministry

- Politics & Current Affairs

- Higher Education

- Global Church

- All Topics & People

Help & Info

- Contact Us | FAQ

Unlock This Article for a Friend

To unlock this article for your friends, use any of the social share buttons on our site, or simply copy the link below.

Share This Article with a Friend

To share this article with your friends, use any of the social share buttons on our site, or simply copy the link below.

- Bible Cards

- Login / Register

Visual Theology

Seeing and Understanding the Truth About God

We live in a visual culture. Today, people increasingly rely upon visuals to help them understand new and difficult concepts. As teachers and lovers of sound theology, we have a deep desire to convey the concepts and principles of systematic theology in a fresh, beautiful and informative way. In this book, we’ve have made the deepest truths of the Bible accessible in a way that can be seen and understood by a visual generation.

My mind is blown. Tim Challies and Josh Byers marry rock-ribbed Reformational theology with breathtaking presentations. The effect is something like following John Knox into the Matrix. In this diaphanous world, we encounter no fiction, but very reality itself –God-reality– and we are transformed.

Owen Strachan

Associate professor of Christian theology and Director of the Center on Gospel and Culture at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

About the Book

We live in a visual culture. Today, people increasingly rely upon visuals to help them understand new and difficult concepts. The rise and stunning popularity of the Internet infographic has given us a new way in which to convey data, concepts and ideas.

But the visual portrayal of truth is not a novel idea. Indeed, God himself used visuals to teach truth to his people. The tabernacle of the Old Testament was a visual representation of man’s distance from God and God’s condescension to his people. Each part of the tabernacle was meant to display something of man’s treason against God and God’s kind response. Likewise, the sacraments of the New Testament are visual representations of man’s sin and God’s response. Even the cross was both reality and a visual demonstration.

As teachers and lovers of sound theology, we have a deep desire to convey the concepts and principles of systematic theology in a fresh, beautiful and informative way. In this book, we’ve have made the deepest truths of the Bible accessible in a way that can be seen and understood by a visual generation.

Section 1 – Grow Close to Christ

As Christians, our first and most basic discipline is cultivating and growing into that personal relationship with Jesus as we hear from him, speak to him, and worship him.

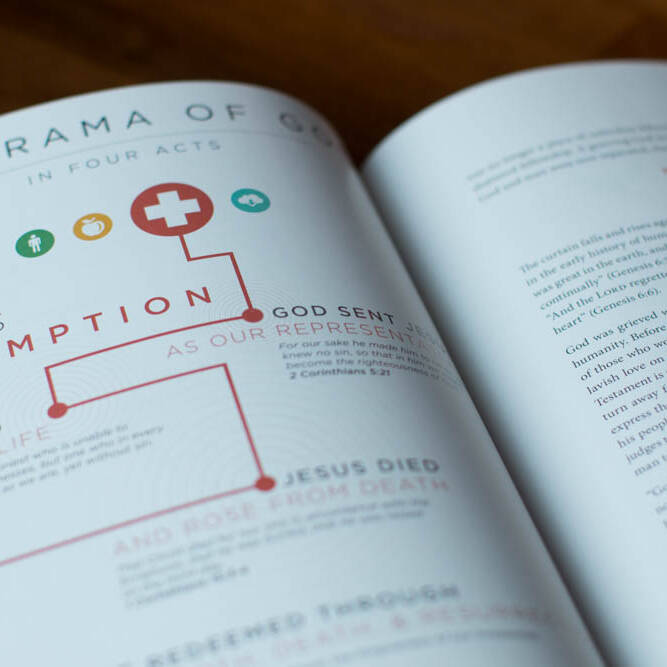

Chapter One: Gospel

Chapter two: identity, chapter three: relationship.

Section 2 – Understand the Work of Christ

There is content to the Christian faith–information and facts we need to understand. We need to grow in our understanding of what God accomplishing in this world, and as we do that , we will want to grow in our knowledge of God himself so we can better understand who he is and what he is like.

Chapter Four: Drama

Chapter five: doctrine.

Section 3 – Become Like Christ

The Bible tells us to be conformed to the image of Christ, to think like him, to speak like him, to behave like him. We do this by putting away old habits, patterns, and passions and by replacing them with new and better habits, and passions.

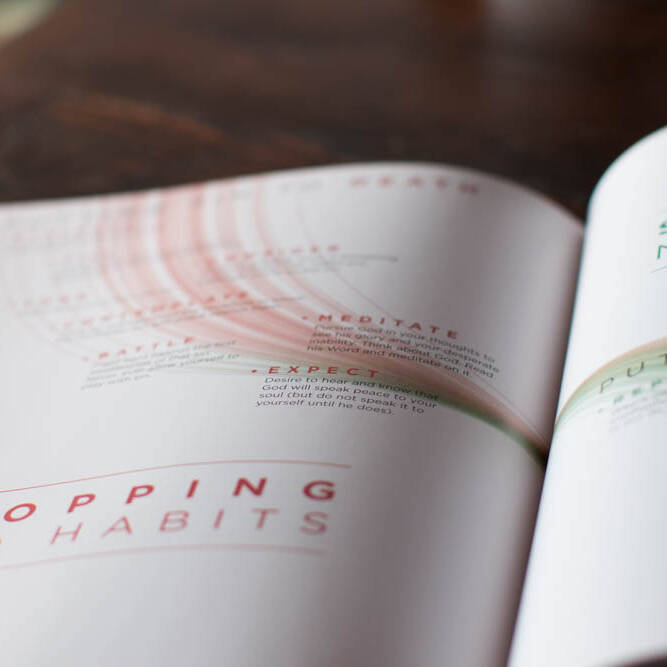

Chapter Six: Putting Off

Chapter seven: putting on.

Section 4 – Live for Christ

We need to learn to live for Christ from the moment we wake up each day to the moment we fall asleep, to live in such a way that we draw attention to him and bring glory to him.

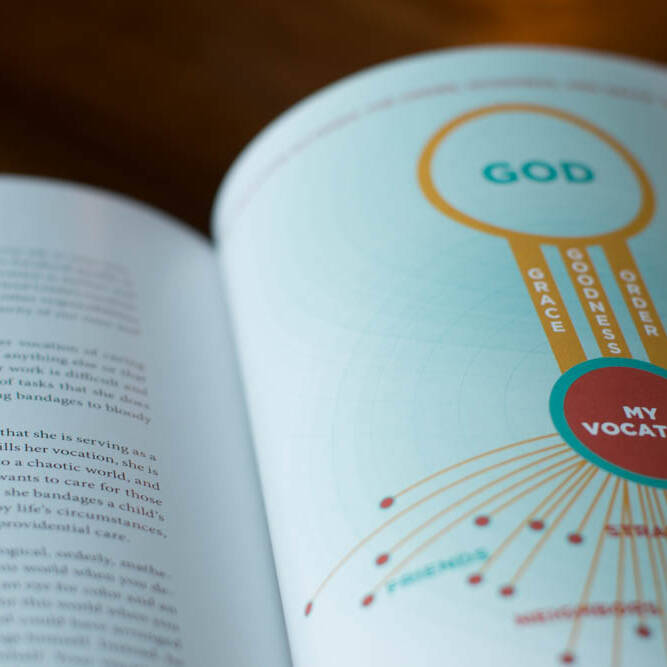

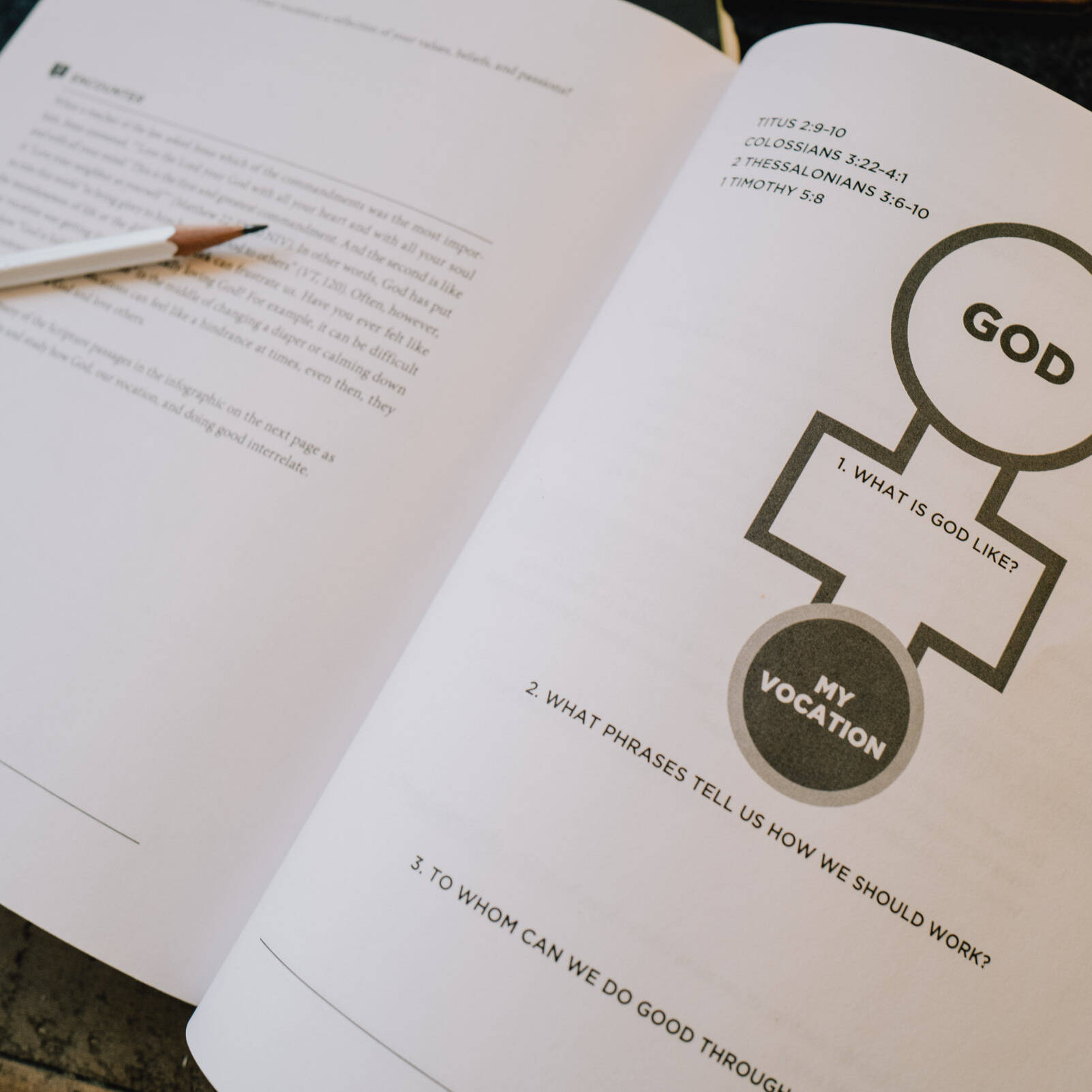

Chapter Eight: Vocation

Chapter nine: relationships, chapter ten: stewardship, teaching resources.

The book A Visual Theology Guide to the Bible was written and designed to be taught in a small group, Sunday school classroom, or homeschool. For that reason, we’ve produced a workbook and presentation slides, and handouts that will help you teach through the book.

Student Workbook

The Visual Theology Study Guide is a ten session study designed to help you grow in godliness by practicing what you learn, and it includes application for both personal and small group study. Each chapter includes key terms, group study discussion questions, and exercises for personal reflection in God’s Word.

Presentation Slides

Teach through Visual Theology the book with the official Visual Theology Presentation Slides!

We took every single graphic in the book and customized it for display in a teaching or preaching presentation. We didn’t just simply resize the graphics either. Every single graphic was re-worked and custom built to display the information best on a presentation slide!

The Concept of the Image in the Old and New Testaments

- First Online: 02 October 2021

Cite this chapter

- Michael Shaw 2

1741 Accesses

1 Citations

It is notoriously difficult to define the term image . Is it an idea, an artifact, an event, or another phenomenon altogether? W.J.T. Mitchell’s influential essay “What Is an Image?” developed a “family tree” of images, including graphic, optical, perceptual, mental, and verbal images (Mitchell, Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1987). James Elkins, building upon this model, has suggested an even more diffuse genealogy of image types (Elkins, The Domain of Images . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999). Sunil Manghani synthesized both approaches and has proposed an “ecology of images”, through which one can examine the full “life” of an image as it resonates within a complex set of contexts, processes, and uses (Manghani, Image Studies: Theory and Practice . London: Routledge, 2012). For the purposes of this analysis, we shall accept this model of an ecology of images, encompassing the graphic, optical, perceptual, mental, and verbal images. The fundamental question, then, is this: How do the Old and New Testaments conceptualize the category of image ? We shall examine the concepts of “graven images”, theophanies (appearances of God), and the “image of God” within the biblical canon, and argue that the conceptualization of image within the Judeo-Christian scriptures contains both a potent iconophobia on one side and iconophilia on the other.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Barrett and Greenway. 2017. “Imago Dei and Animal Domestication: Cognitive-Evolutionary Perspectives on Human Uniqueness and the Imago Dei”. In: Pederson, Daniel and Lilley, Christopher (eds.) Human Origins and the Image of God: Essays in Honour of J. Wentzel van Huyssteen . Grand Rapids: Eerdsmans.

Google Scholar

Barth, Karl. 1958. Church Dogmatics, Vol III: The Doctrine of Creation . Edinburgh: Clark.

Baxandall, Michael. 1988. Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blunt, Anthon. 1999. Art & Architecture in France 1500–1700 , revised ed. London and New Haven.

Cairns, David. 1953. Image of God in Man . London: SCM Press.

Clines, D.J.A. 1968. “The Image of God in Man”. Tyndale Bulletin , 19, no. 93.

Cortez, Marc. 2010. Theological Anthropology: A Guide for the Perplexed . London: T&T Clark.

Dyrness, William A. 1985. “Aesthetics in the Old Testament: Beauty in Context”. JETS , 28 (4): 421-432.

Eliade, Mircea. 1957. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion , translated from French: W.R. Trask. Harvest/HBJ Publishers.

Elkins, James. 1999. The Domain of Images . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Feinberg, Charles Lee. 1972. “The Image of God”. Bibliotheca Sacra , 129: 235–246.

Grenz, Stanley. 2004. “Jesus as Imago Dei: Image-of-God Christology and the Non-linear Linearity of Theology”. JETS , 47 (4): 617–628.

Gruzinski, Serge. 1988. La colonisation de l’imaginaire: Sociétés indigènes et occidentalisation dans le Mexique espagnol, XVIe–XVIIIe siècle . Paris: Gallimard.

Kitchen, Kenneth A. 2003. On the Reliability of the Old Testament . Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Kleinknecht, H. 1967. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament . Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Louth, Andrew. 2013. Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology . London: SPCK.

Manghani, Sunil. 2012. Image Studies: Theory and Practice . London: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Middleton, J. Richard. 2005. The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1 . Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press.

Mitchell, W.J.T. 1987. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Oswalt, John. 1973. “The Golden Calves and the Egyptian Concept of Deity”. Evangelical Quarterly , 45: 13–20.

Pelikan, Jaroslav (ed.). 1958. Luther’s Works . St Louis: Concordia.

Radine, Jason. 2010. The Book of Amos in Emergent Judah . Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Snaith, Norman. 1974–1975. “The Image of God”. Expository Times , no. 86.

Stuart, Douglas. 2006. Exodus: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture . Holman Reference.

von Rad, Gerhard. 1962. Old Testament Theology . 2 vols. New York: Harper & Row.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Christianity in Society, Belfast, UK

Michael Shaw

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Academy of Arts and Culture, Josip Juraj Strossmayer University, Osijek, Croatia

Krešimir Purgar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Shaw, M. (2021). The Concept of the Image in the Old and New Testaments. In: Purgar, K. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Image Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71830-5_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71830-5_2

Published : 02 October 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-71829-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-71830-5

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Conference Media

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Upcoming Events

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

The Visual Discovery of God

More Episodes

During a breakout session at The Gospel Coalition’s 2019 National Conference, Josh Byers and Tim Challies teamed up to deliver a message titled “How Visual Theology Displays the Truth About God.” Never before in history has the world been so acutely aware of the importance of visual communication.

The power of images to shape culture, communication, and education is undeniable, including within the church. Yet imagery has been troublesome at times in church history. In order to help people within our churches become good theologians, we must teach sound doctrine in words, but we also need to engage them visually in order to undergird and communicate truth in ways we might not otherwise clearly accomplish.

The following is an uncorrected transcript generated by a transcription service. Before quoting in print, please check the corresponding audio for accuracy.

Tim Challies: So we’re here to talk about visual theology. And I’m sure you’ve heard that old saying, that a picture is worth a thousand words. And I think of all generations, possibly, our generation knows about the power of images, right? We are such a visual and an increasingly visual generation.

You think about some of the last great communication technologies, many of them were the printing press, or radio, were word based, telegram, word based communication. The more recent innovations, such as television, the internet, have really been visual based innovations. And so we’ve become the YouTube generation, the Netflix generation, the Instagram generation. And just over time you can see it, especially with younger people, more and more are depending upon images to learn. It’s such a powerful way of learning.

And images can be compelling. I think images can be very, very informative yet, the history of the Christian faith tells us they can also be troublesome. They can also be dangerous. We’ve learned, as you study Christian history, study world history, you see that images can be used to really help our work in this world or images can be used to hinder our work in this world. They can be used to tell truth. They can be used to proclaim error.

So what we want to talk about and what’s one of our passions, is talk about how we can bring words and images together to explain truth and to build up Christians. That’s what visual theology is, it’s displaying what’s true, especially displaying what’s true about God.

So, I’ll spend a few minutes talking about the theological angle, then Josh is going to show you some visual stuff on the screen here and then we’ll get on.

So everything I want to say here is premised on this idea that’s, I think really obvious to some people and really novel to other people which is, we are all theologians. I believe R.C. Sproul wrote a book by that title. We’re all theologians. God calls us all to know what is true about him. We’re responsible before God to learn what is true about God. What’s true about God’s character. What’s true about God’s actions. What’s true about the world He’s made. What’s true about ourselves, right? What’s true about the future of this world. God made this world. God made everything in this world and it’s our responsibility to learn it. So in that way, we’re all theologians. We all need to acquire knowledge of God and His ways and His works.

But we don’t just need to learn it, we also need to teach it. So we’re all theologians in the sense that we need to learn truth. We’re all theologians in the sense that we need to apply truth. We’re all theologians in the sense that we need to teach, convey truth, to others.

And again, I say this idea is normal to some people and novel to others because we’re living in this time and in this Christian culture of just woeful theological ignorance, right? So many people just don’t know theology. They don’t know sound doctrine. I’m a writer by trade and day by day I’m trying to release something to the world that will be helpful or encouraging. And I got so much feedback from people and it’s just amazing to me how little some people really know. And that’s fine if they’re new believers. We understand, we all enter the Christian life unknowledgeable, ignorant. We all enter the Christian life phoretical. No new believer can explain the doctrine of the Trinity in a way that’s true and orthodox, right? So we all enter that way.

What concerns me is when people have been Christians for years or decades and they still don’t have any real knowledge of theology. And I find this very, very common and very, very tragic. I found myself thinking recently about that passage in Acts chapter 19 where Paul comes to Ephesus for the first time. Here’s what it says, it says, “It happened that while Apollos was at Corinth, Paul passed through the in land country and came to Ephesus. There he found some disciples and he said to them, ‘Did you receive the Holy Spirit when you believed?’ And they said, ‘No we’ve not even heard that there is a Holy Spirit.”

So, here are these people who were disciples, true disciples of Jesus, but they had no knowledge of the Holy Spirit, right? We don’t really know all the facts of that situation. It’s clearly something unique that happened in that time where you could be a disciple but not indwelled by the Spirit. But we do know this, they were ignorant. Nobody had taught them about the Holy Spirit, that there even was a Holy Spirit.

And I wonder today as if we travel around the world, travel around the church, we would just find vast numbers of people and we might say to them something like, “Tell me about your theology?” And they might say something like, “We don’t even know that there is such a thing as theology.” There’s just so many people who have never really been taught that there is such a category and that that ought to matter to them.

They knows things like Christianity is not a religion it’s a relationship, right? A saying like that and okay, yes, that’s true. We do have a relationship with God. It’s a beautiful thing that by putting our faith in Jesus Christ we’re adopted into the family of God. We enter into this true, living relationship with God. I mean that’s true and that’s amazing. That’s something only the Christian faith offers, but it’s not true that Christianity is not a religion, right? It is a substantial, established, orderly, cohesive body of truth, that’s simply the reality. And so many people have never been taught that. They’ve never been taught theology. They’ve never been told, “You are a theologian.” The only question is are you a good theologian or a bad theologian?

And really I think for a lot of people, even true believers, all they’ve ever been told about theology is that theology is kind of dangerous. That doctrine divides, statements like that. Or they only know theology as this cold, heartless pursuit of cold facts and you take those facts and you use them to body slam other people, right? And yeah, a lot of people do misuse theology in that way.

But they’re never taught that theology is so much more and so much better and so much grander and so much sweeter than that. And so I think about, what’s the cost and the consequence of having genuine believers like they’ve truly come to faith. They’ve truly put their faith in the Lord Jesus Christ and received His salvation, but they’re just not growing in their knowledge of God. They’re not growing in theology. What happens when they don’t embrace their role as theologians? When they don’t try to grow in their understanding of God? When they’re not willing to teach other people how to do theology? How to know theology?

And this is again where I see a lot of this. Something like this happens, a friend comes to them and hands them a book and in that book, the author of the book says, “I am a reformed Presbyterian, Protestant Christian. This book is messages that Jesus has communicated directly to me.” Right? She listens and Jesus speaks his revelation directly to her mind and she writes it down and there’s vast numbers of people who don’t have any kind of concern with this sort of theology.

Why is that? Because people don’t have a sound knowledge of the doctrine of Revelation, the theology of how God reveals himself to humanity. So they see nothing concerning about somebody saying those sorts of things.

Now, for some people that sets alarm bells ringing, for others it does not. I don’t want to say you can’t have theological convictions if that sort of thing is possible. Because I think there are people that can wrap their minds around or go look at scripture and say, “No, I can see where that kind of thing could be possible.” I’m not endorsing it, I’m just saying some people can get to that point theologically. But for a lot of people they just never thought about it.

So somebody comes with something that’s new and novel to the Christian experience. This idea that Jesus speaks to me and I’m giving you messages from Jesus. They don’t have the ability to apply theology to it, to think it through, through the grid of the Bible. So again, you can, some people can get there theologically and at least then we’ve got to grant them, they are acting as theologians.

Or another thing that happens, someone might hand them another book and they open that book and it’s a book about the Trinity. And as they start to read it, they come across a statement like this, “The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit died together on the cross.” Well so many people have no substantial knowledge of the doctrine of the Trinity. And so this doesn’t stand out to them as anything concerning, anything that’s opposed by 2000 years of church history, opposed by the creeds and the confessions of the church. They’ve never developed that substantial knowledge or theology of the person of God and the works of God.

As Christians we need to understand, when we become Christians, we don’t set out into this Christian life on our own, right? We enter into this stream where all these people have gone before and we join them by taking hold of what they’ve already established. We’re not making this up as we go. Yet, my not so subtle references to two different books there. Those books exist and they’ve sold somewhere around 40 million copies between the two of them, which is like 39.9 million more than most authors, successful authors, would sell in their lifetime.

So many Christians have so little knowledge of theology that they’re unequipped to identify what’s novel, what hasn’t been done before and they’re unequipped to identify what’s really dangerous, what’s been full out denied by the history of the church so far. And so when the people don’t have that kind of theology, when they’re not even looking out at the world through a theological mindset, it’s so simple then to lead them astray. So simple to convince them that error is truth. So simple to convince them that this new thing is so much better than what we’ve already got or what God has already given us.

So as people come to a conference like this one, a session like this one, I think we can acknowledge this premise that we’re all theologians and the question we’re grappling with is, will we be good theologians or bad theologians? Will we be equipped or will we be ignorant? Good theology is theology that’s drawn from the Bible in an accurate and orderly and a systematic way that really reflects the mind of God. The alternative is chaotic theology, right, that’s formed from best sellers and memes and Ted Talks and stuff like that, theology that’s always searching but never arriving at a knowledge of the truth.

So we need to keep in mind that theology is not the accumulation of cold facts. That’s not what we’re in the business of as theologians, as Christians who are trying to come to deeper and better theological convictions. We’re not just accumulating cold facts, right? Theology is knowledge of God, knowledge of the ways of God that then works itself out in our thoughts and in our actions and the way we think and the way we live.

When we’ve got great knowledge of God we can think great thoughts of God, right? When we think great thoughts of God we can live great lives for God. And when we live great lives for God we bring great glory to God. We’re not doing it for ourselves. We’re doing it to bring glory to Him. So in that way theology isn’t serving ourselves, right? Arriving at deeper theological convictions isn’t just doing something for ourselves, really, we become theologians so we can better serve other people. It’s what we’re doing in this world, right? We’ve living for the good of others which brings glory to God. And sharp, theological convictions allows us to do more good for others and bring more glory to God. We can’t truly know God, we can’t truly live for God until we know the facts that God gives us about Himself.

So that means, you and I as individuals are responsible to consistently go to the word of God and learn the theology scripture teachers. We can go directly to scripture. We can use the many resources that are available to us through the history of the church written by other Christians and so on. God’s word, as you know from Second Timothy three it teaches us, it reproves us, it corrects us and it trains us in righteousness, that’s theology. That’s theology to fill our minds and to warm our hearts and to direct our hands in this world.

So as individuals, we need to go the word. We need to be theologically informed. As parents, as so many of us are, we’re responsible to instruct our children in sound doctrine. You can think of Timothy, young Timothy who was the protégé of the apostle Paul, whose mother and grandmother were commended by Paul for what they had done in the life of this young man. But as for you, Timothy, continue in what you have learned and have firmly believed, knowing from whom you’ve learned it and how from childhood you’ve been acquainted with the sacred writings which are able to make you wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus.

So here’s this young man, who his mother and his grandmother from a young age had been instructing him in scripture. Instructing him in the sound doctrine that the scripture teaches. He was well taught. So no wonder then, he was able to profess that truth, able to address error. No wonder that a man like that was a pillar of the earlier church. In our lives and our families and then of course in our churches, we need to teach sound doctrine. As pastors, teaching it from the pulpit and members teaching and training one another as we go through this life together. Peers, mentors, everybody, filling themselves with sound doctrine and extending that, reaching that out to others.So as individuals, as families, as churches, students, teachers, we need to be theologians. We need to be training the next generation of theologians.

So how do we do that? And this is where Josh and I have put a lot of thought, a lot of effort into this and we’ve realized that the majority of our efforts in teaching sound doctrine have been in words, right? We explain the truth using words. We preach the truth and we go to classroom settings and do lectures and seminar settings and churches or youth group settings and we teach doctrine using words. And that’s absolutely wonderful and necessary. But we started wondering together, are we missing out? Are we missing out on the opportunity to teach truth visually? Because as a society we see visuals being used to teach a lot of different things.

People are using images like they never have before through computers, through design software, through all sorts of things, through YouTube. We’ve got this ability to teach through images like we never have before. Great opportunities to use images to supplement our words to go along with them, not to replace them. We’re not in the business of getting rid of words and completely replacing them with images. But can we keep speaking those words that are good and true and add to them images that will just engage people’s minds in a different way and give them another way of learning truth? And so I’m going to turn it over to Josh and he’ll tell you about the visual part of visual theology.

Josh Byers: Okay, Trinity right. Can you explain what we’re saying through it? Can anybody get it? Just curious. So real quickly I’ll explain it for you. You’ve got it on you. So, the Father is not the Son. The Son is not the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is not the Father. But the Father is God. The Holy Spirit is God and the Son is God. So, a very simply way to explain the Trinity. That’s the essence of what visual theology is. We could’ve used a clover, but we’re not heretics. So, it’s why we did not do that.

All right so, Tim mentioned something. He mentioned that God reveals Himself to humanity. And we want to be able to teach people visually. So the question is, how do we do that? Now, when he says that God reveals Himself to humanity, how does He do that? What do we know about God? What has He revealed to us?

Now yes, He has revealed Himself through His word. There’s a number of attributes that we know about God through His word. Okay, so here’s just a few of them. We know that He’s merciful. We know that He’s righteous. We know that He has wrath, right? He’s truthful. He’s knowledgeable. He has wisdom as well. There’s one attribute though, that I think is really interesting that pertains to our particular subject here and that’s the attribute of invisibility. The idea that His total essence, all of His being will never be visible to us. Now obviously, the visible risen Christ we can see and we will see someday. But His total being of all that He is will not be visible to us. Yet, what’s interesting is that He created us as visible creatures, where everything to us is visual. So when we ask the question, how do we teach visual theology, one of the things that I think is important for us to get the foundation and to understand that we were created first of all, as visual beings. As God is invisible, He created us as visible.

When you read the first chapter of Genesis, you realize very quickly that this visual communication has been at the heart of all communication since creation. And even in the text there, you have this beautiful account, it doesn’t just list bullet points of this, this, this, this, and this. It’s not a list. You have Moses writing this beautiful poetry about how the world came to be. And the visuals, they’re in that, help us get a picture in our mind.

So in the very beginning of the Bible it says, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty and darkness was over the surface of the deep. And the spirit of God was hovering over the waters.” I love reading that. It almost sounds like a movie trailer. In the beginning was a world that was formless and void, right? It’s just this idea that automatically transports us to the creation account and brings this beautiful, visual picture into our minds. And not only do we have this beautiful description of what creation is, we obviously have creation itself.

The idea that God created us to appreciate beauty is somewhat mind blowing to me. The idea of, what is beauty? How do I even know how to recognize what is beautiful? Obviously there’s some subjectivity there, but for the most part, we can all agree on what is beautiful. And God put that into us. He gave us an endless variety of colors and hues to experience creation in.

And one of the things I love about this is that as we start to think about the idea that God gave us these things starts to point to the fact that He does want to reveal Himself to us. He does want to have a relationship with us.

L. Shannon Jung, he’s a professor at the Saint Paul School of Theology said this, he said, “The beauty of fields of wheat and sunflowers and pecan orchards and gigantic stalks of corn, they’re all more beautiful than they need to be. They manifest the beauty of God and they awaken us to the sensibility of the world. And they call us to an appreciation of all that is.”

So here’s the reality, God could’ve made our world black and white. He could’ve made it formless. He could’ve made it tasteless. He could’ve made it colorless, but He didn’t. He gave these gifts to us to experience. He gave this beauty and this goodness to us and that reveals that we have a very personal God who is interested in interacting with us. This invisible being wants to interact with us as visible beings. He wants us to enjoy Him. He wants us to have a relationship with Him.

But how does an invisible spirit being interact? How does he cultivate relationship with visible beings? How does He reveal Himself? How does He show us who He is? How does He let us respond to Him?

Well, among other things, He uses symbols and visual displays and He’s done it from the very beginning. Think about the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. What was the purpose of that? All right, just this big temptation warning light in the middle of the garden? No, no, no, no. Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil was something that Adam and Eve could look at and every single time they walked by that tree without eating they were able to respond to God and say, “I love you. I trust you. I believe what you said about this tree.” It was an opportunity for them to love God back in this big visual picture.

Adam and Eve’s first clothes, when they did sin they created fig leave clothing for themselves that God rejected. He then gave them other coverings that he accepted. What was the point of that? It was to show them visibly that what you’re trying to do, how you’re trying to fix yourself, doesn’t work. So visually, I’m going to give you better clothes.

And then think about where those clothes came from. They came from the skin of an animal. Now if we read into that, the sacrificial system started right there and then. So what did God do? He killed an animal right in front of them. They’d never experienced death before, but right there in that moment they had a visceral, visual picture of what their sin cost. And what God then did to fix it and to cover it. And it was all very visibly and visual so that they could understand what was going on.

That then leads into the sacrificial system. And you think about the horrible visuals of a sacrifice. The slitting of the animals throat. The blood running out over the altar which was required, why? Because it says in Leviticus that the blood, that the life of the creature is in the blood. And so all these visual pictures, all these ideas that God wants to present to His children.

When they get to Mt. Sinai, God says to Moses, He says, “I want you to draw a line around the mountain and tell the people, ‘If you cross this line, you will die.” He wanted to give them a visual representation of what? The fact that you cannot approach me in an unholy state. If you do, you can’t be with me. You have to be completely separated from me. That’s not all.

God then asked them to wash their clothes and to consecrate them. Why? Because they were dirty and smelly? Probably they were a little smelly, right? But that wasn’t the point. He said, “I want you to understand that when you come before Me, you have to be pure. You have to be clean.” Now, did that fix their sin problem? No. But it gave them again, the visual of what their relationship was to God. It revealed God to them. And then He comes down in thunder and lightning and smoke and these people, it says that they were terrified. They dropped to their knees over this visual display of who God was.

Then you have the tabernacle, where literally every single thing in it is a visual picture of what God is doing and how He’s relating to His people. And this is only a hint in the first two books of the Bible. You can go all the way throughout the rest of the scriptures and what is God doing? He’s presenting symbol after symbol after picture after picture to teach His people. You get to the New Testament, what’s Jesus doing? He’s teaching with parables. He’s telling them stories. He’s giving them word pictures. I am the door. I am the bread. I am the light. I am the vine. I’m the cup.

At the Lord’s supper, it may be the ultimate moment or the penultimate moment right before the cross, of visual theology. And it makes sense because that’s how God created us. We were created to be visual beings. We were created to be drawn to beauty. And so God, an invisible spirit, uses visual illustrations to reveal Himself to us.

Now, like Tim already said, we don’t just go out and throw the Bible away and download Photoshop and call it good, right? That’s not what we’re in the business of doing. We take the word of God very seriously. We just wrote a book on this subject. The visuals have never replaced, nor will they ever replace His word. The scriptures will always be the primary place where we learn who God is and how to cultivate relationship with Him. But they can be so helpful.

So, to first teach visual theology you have to understand the foundation, that we were created to be visual beings. That God has been teaching this way and that it’s a good thing from the very beginning.

Number two, we have to learn to think visually and this is where we’re going to get a little practical. This is why I have you all over here on this side because we’re going to get a little practical here. And I want you to start to understand at least how we think in some ways. And maybe how you can start to think on how to do some of these things. Because it’s not really rocket science. The stuff we do is pretty simple. You can just copy it, that’s kind of what I do a lot of times anyway.

But I want you to start, not really, I want you to start thinking visually. So when I’m creating our graphics, I ask myself basically two questions, right? The first question that I’m asking is, what am I teaching? And the second question is, how can I display it? So we keep it simple.

So first of all, what am I teaching? What is the story that I want to communicate? I always want to break it down as simply as possible. We don’t want to have major ideas competing because if we do that then we lose the biggest advantage that visuals have over test. And that is, speed. We can communicate so many ideas so quickly with a visual.

3M, they’re the company that makes Post-it Notes and all that other kind of fun stuff. They did a study a number of years ago and they found out that when you combine visuals with teaching people understand the concepts 60,000 times faster. All right, there’s all sorts of statistics that we can pull. Facebook says that their posts with graphics get two to three times more engagement.

My daughter just took her driving test. Pray for us. She mastered the visual component of that way before she mastered the verbal part or the written part. Obviously because those things come so much quicker to us.

So in this aspect here, when we’re trying to communicate too many things, too many truths at once, we lose that speed advantage that visuals are giving you. So, you can obviously have a lot of depth of information in it, but there should be one overall thing that you’re trying to communicate. So, in the latest book that we’ve done here, it’s right here. You can pick it up at the bookstore. I got the plug in. And one of the graphics we wanted to create is, I wanted to tell the story, we wanted to show that Jesus is present throughout the entire scripture. That His life is involved and is woven throughout all the scriptures. So that’s the thing that I wanted to teach.

Now the second question is, how do I display it? How can I visually represent this thing that I want to teach? And my philosophy is, I want to do it in a simple and beautiful way. I want to keep it simple so you understand it. I want to do it beautiful so that you want to continue to look at it. So that you want to continue to share it with others.

So if I want to teach that Jesus is the story of the Bible, the Bible is all about Jesus all the way through, how can I show that? Well, one of the things that I thought of is you can connect the prophecies in the Old Testament to the New Testament. So this is what we came up with. Now, on the surface this looks kind of complicated, but really there’s one overall purpose. There’s one overall arching message to this and that is the fact that the life of Jesus is woven all throughout the scriptures. Now like any good infographic, you can go deeper into it. You can see, okay, these ones are talking about His life. These ones are talking about His birth, His ministry, His resurrection. And then you can start to match up the references and just if you’re wondering, it’s really easy. The columns, you have the Old Testament and the the New Testament, the first one on the top from the Old Testament matches with the first one on the top or the first one on the bottom with the New Testament, so on and so forth. So you can match them up real easily. It’s not as complicated as it actually looks.

And then if you look at every seventh letter it unlocks a code on our website, no, I’m just kidding. It will tell you the secret message of the Bible. Now, for the most part what we’ve done, we’ve chosen to communicate primarily through the medium of infographics and there’s obviously a lot of different ways that you can communicate visually. Film, photographs, drama, we’ve chosen infographics primarily because I think it seems to tap into the advantages that both text and graphics have.

So, the power of text is you that can present an idea clearly and with a lot of clarity, right? The power of visual is that you can juxtapose maybe multiple meanings or maybe most important, you can elicit an emotional response that you don’t necessarily get with text. I think infographics actually combine those two things. They can elicit the emotional response. You can get bigger meanings out of it but it also has a lot of clarity to it. So that’s why we choose to use infographics.

Now, I want to explain this a little bit further and we’re going to give you a peak into the process that I use. And the goal here is I want to start to maybe unlock something’s in your mind. I want to inspire you to start thinking how you can create visually. All right? And with infographics, especially there’s a number of categories that they fit in. So that’s how we’re going to do this. I’m going to show you a bunch of different categories and how then our graphics fit into these and then you can hopefully go back and start working on your own. And if you’re taking notes, I’m going to kind of go through this fast. All of this will be on my blog so you don’t need to worry about if you miss something, it’ll be up there. Okay?

So here we go, number one, the first type of graphic that we’re using is called a quantitative graphic. And what this does, it shows relationships between amounts. The one that I want to show you here is a graphic that we did on the story of Gideon. As you’re reading through the book of Judges like I was one day, I came across this story and you have some numbers there. And it said that the armies of Gideon were 300 and the armies of Midian were 130,000 and then you keep on reading.

I stopped for a second like, what does 130,000 look like? When you just see it on the page the number there doesn’t mean a whole lot, but when you start to actually think about what that is, it’s kind of ridiculous. We’re not done because Keynote wouldn’t let me do it any further, so I had to create a whole other slide.

Now, there’s power here but there’s not as actually as much power as if you see it all in one poster. It’s pretty cool when you see it in one poster. But the idea that this is what they were up against. What’s the thing I’m trying to teach here? Is that the glory goes to God and God alone.

So that’s a quantitative. It shows relationships between amounts. Those are really easy to do. Just find relations between amounts in whatever story you’re trying to teach and those are pretty simple.

Statistical, they’re just numbers but we make them look pretty. All right? The book of Numbers, obviously. There’s a lot of fun things in there. One of the very first pages of the new book, we talk about some different statistics that are there and all we’re doing is we’re just putting colors with it and laying them out a little bit to give them more visual appeal.

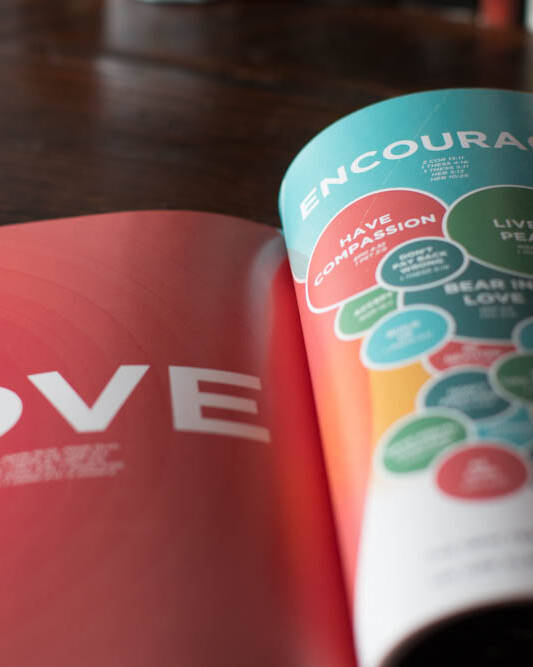

Relational graphics, these are comparing and finding hidden relationships in data. Now in the first book that we did, one of the things we thought we would do is we would try and communicate all the one another’s that are commanded in New Testament. So you should encourage one another, you should greet one another. And so I was trying to figure out a way to display this and I thought there’d be a good relational value of this if we maybe enlarged the circles to see how many times it was mentioned. And I got some interesting information from that.

One of the things you’ll often realize is when you start to compile relational data, is that there are some surprises. And there’s a reason that love is called the greatest commandment. And here’s another power of the infographic is that it can juxtapose as multiple meanings. Not only is love the greatest commandment, but love is responsible for all of those things. You can put all of those things inside of love. So another powerful thing that you get from just the visual aspect of this.

Timeline, this is how subjects change or progress over time. These are pretty easy, right? Kings of Israel, the prophets that go along with them. Doesn’t just have to be dates, though. It could be the genealogy of Jesus there. Whoops, we’ll go back to that. Hold on. That’s another timeline type graphic as well.

Process, our how to. This is just a step by step guide in doing something. So memorizing scripture for example. How do we do that? Well, we just use a simple one, two, three, four, five process.

Comparisons, we can compare and contrast two different subjects or we can show two different sides of a single subject. So, again in the new book, we have a graphic in there called ten rules and this is when we’re trying to explain what the Ten Commandments are and what they do. And the big idea here is that I want you to understand and see that there was a difference between Jesus keeping the law and Israel keeping the law, right? So here we had the fact that Jesus was able to have no other gods, but Israel had many gods before them. So we’re able to compare and contrast the differences between the two.

We have lists. It’s exactly what is sounds like. It’s just a list of information related to a subject. So in this instance we have just a list of miracles. And then we do quantify that a little bit, so we combine two different types of graphics, where we quantify how many are of which, not that that has a lot of meaning behind it but it just kind of shows you what’s interesting there. How many times Jesus did healings as opposed to how many times He, I was surprised at how many times demons that He healed from people as well.

Flow charts, you start with a single point or a question then you branch off depending on the answers given. One of the ones we did with this, we entitled this, how to put sin to death. And who’s the original author behind, do you remember that?

Tim Challies: [inaudible]

Josh Byers: John Owens, yes from John Owens. So we just took John Owens, basically his formula on how to do that and put it into an infographic that, we’ve had this up in our youth room before and I’ve literally seen students just stand there. I don’t know if it’s because they couldn’t read it or if it’s too hard to follow, but they were engaged. They were looking at it and hopefully they’re learning some aspect of how can I put my sin to death. But it’s engaging in that way.

An inside view, so this is when we break down what makes something work or how it’s put together. So you have idea like this where we can actually see what’s inside the tabernacle. The specific distances or sometimes you’ll see exploded pictures of things, right? That’s what these are.

And then lastly we have maps and these are pretty obvious as well, where we can use location or geographic data to display ideas.

So we understand that we are created to respond visually if we want to teach this. We understand that we need to think visually and then lastly we just need to display it. And there’s a lot of flexibility that you actually have when it comes to these things. I think the beauty of when you’re using a visual theology, it’s that obviously, yes, you can teach it, right? You can stand up here and you can teach the one another’s and show that but you can also just display it casually, just put it up on a wall. Just put it up. Just have it. Just give it to somebody. Put it up on Facebook. Put it up on Instagram and just let it be there for people to come and draw them in so that they can see it. They can wander into it under their own time.

So many times I go to churches and I see the things that they have on their walls where it’s like, you’ve got to be kidding me? There was one church I went to and I went into the bathroom and they had this really cool quote. And it sounded really spiritual except that it was from the Book of Mormon. And they didn’t realize it. And so let’s replace these things. Let’s start teaching people. We want to communicate what we actually do value. If we value theology, if we want to teach theology in a deep way, we want to communicate that by putting it on display for all that can see.

Just a few more ways of how I’ve seen it be used. We get so many messages, emails every single week from people that are using this stuff around the world. I got an email from a pastor who was counseling a couple and he was trying to get them to understand the concept of biblical submission and it just wasn’t getting through. Then he showed them this graphic and he wrote and he said it was like a light bulb turned on for them. And they said they understood it and they were able to go through it with them.

We’ve had missionaries contact us. They’ve taken the graphics and they’ve been able to be translated and this a missionary that was in Cambodia that was using them. This is a missionary in the Philippines that’s teaching through our books of the Bible graphic, teaching students how to memorize the books of the Bible. Like I said before, it’s good to put these up in churches. They’re replacing photos like that of dream boat Jesus. He’s pretty isn’t he? This is being recorded. I forgot. Okay.

Well, you know, with scripture, with things that actually engage people. Student ministries, like I said, putting these up in their youth room. Letting their students wander in and engage. And then I’ll end with this. There was a dad who wrote me and he said that he got our attributes of God poster at a conference that we were at. And he brought it home to his seven year old daughter. She put it up in her room. And every week she’s got this play group that she invites friends over to. And when she put this poster up, she told her friends that she invited from around the neighborhood, “Hey, we’re going to spend five minutes out of our play group and we’re going to read over a attribute of God and talk about it.” Like, are you serious? Seven years old? I mean that’s awesome.

Here’s the big idea, God’s word is not going to return void, right? He’s promised us that, so whether we’re speaking it, whether we’re reading it, whether we’re displaying it, there is so much power that’s there and with this generation and with the way that our culture is being formed by the image, we have got to start thinking visually. We’ve got to start thinking, how can we utilize this to teach the greatest story that’s ever been told?

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

Tim Challies is a pastor, noted speaker, author of numerous articles, and a pioneer in the Christian blogosphere. Tens of thousands of people visit Challies.com each day, making it one of the most widely read and recognized Christian blogs in the world. Tim is the author of several books, including Visual Theology , The Next Story , and, most recently, Epic: An Around-the-World Journey through Christian History . He and his family reside near Toronto, Ontario.

Josh Byers is a designer, illustrator, photographer, and co-author of Visual Theology .

Now Trending

1 can i tell an unbeliever ‘jesus died for you’, 2 the faqs: southern baptists debate designation of women in ministry, 3 7 recommendations from my book stack, 4 artemis can’t undermine complementarianism, 5 the 11 beliefs you should know about jehovah’s witnesses when they knock at the door.

8 Edifying Films to Watch This Spring

For discerning audiences looking for an edifying film to watch this spring, either at home or in the multiplex, Brett McCracken shares eight recommendations.

Easter Week in Real Time

Resurrected Saints and Matthew’s Weirdest Passage

I Believe in the Death of Julius Caesar and the Resurrection of Jesus Christ

Does 1 Peter 3:19 Teach That Jesus Preached in Hell?

The Plays C. S. Lewis Read Every Year for Holy Week

How Christians Should Think About IVF-Created Embryos

Latest Episodes

Lessons on evangelism from an unlikely evangelist.

Welcome and Witness: How to Reach Out in a Secular Age

How to Build Gospel Culture: A Q&A Conversation

Examining the Current and Future State of the Global Church

Trevin Wax on Reconstructing Faith

Gaming Alone: Helping the Generation of Young Men Captivated and Isolated by Video Games

Raise your kids to know their true identity.

Faith & Work: How Do I Glorify God Even When My Work Seems Meaningless?

Let’s Talk (Live): Growing in Gratitude

Getting Rid of Your Fear of the Book of Revelation

Looking for Love in All the Wrong Places: A Sermon from Julius Kim

Introducing The Acts 29 Podcast

Religion: Representations of God

- The Life of Mary Ward

- Representations of God

- Religion through the Ages

- Contemporary Issues

- Texts in Society

- Ethical perspectives

How do you paint Christ as fully human and fully God? The National Gallery reveals the visual language of signs and symbols known as iconography .

Duration: 6:14

Sister Wendy shows how to find the story in an artwork.

Duration: 3:59

Video - Trinity explained in 3 minutes (duration 3:55)

Video - a comprehensive explanation by Mr McMillan (Duration: 5:06)

- The Trinity step by step - BBC Bitesize

- The Trinity in simple language - no technical words!

History of the Catholic Church

Great Schism

Renaissance

Reformation

In the year 1054 a major split occurred in Christianity. The churches in Western Europe, under the authority of the pope at Rome, separated from the churches in the Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) Empire, under the authority of the patriarch (bishop) of Constantinople. The churches of the Eastern Empire have come to be known by the collective term Eastern Orthodoxy.

(Source: Britannica article 'Eastern Orthodox Churches' )

Controversy over the use of icons led to the movement called iconoclasm (image breaking). This in turn paved the way for the final split between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches (1054AD, The Great Schism).

Iconoclasts argued that the use of icons by such leaders as Heraclius was a pagan rather than Christian ritual. Religious art, they claimed, should be only of abstract symbols, plants, or animals. They believed that the growing power of the Arabs was due to the Byzantine sin of icon worship.

Opponents to iconoclasm, led by the monks, were called iconophiles. In 726 Emperor Leo III issued the first of many laws against the use of icons. This ushered in the Iconoclastic Controversy, which lasted until 843. In 731, the Roman pope, Gregory III, countered the uprising with a threat to expel the iconoclasts from the Catholic church.

It was Empress Irene who brought the Iconoclastic Controversy to an end by restoring the use of images in the Eastern Orthodox church.

(Find out more: Britannica article )

The word renaissance means “rebirth.” It refers to the rediscovery by scholars (called humanists) of the classical writings—those of the ancient Greeks and Romans. In fact, however, the Renaissance was a period of discovery in many fields—of new scientific laws, new forms of art and literature, new religious and political ideas, and new lands, including America.

(Source: Britannica article 'Renaissance' )

A religious movement known as the Reformation swept through Europe in the 1500s. Its leaders disagreed with the Roman Catholic Church on certain religious issues and criticized the church’s great power and wealth. They broke away from the Catholic church and founded various Protestant churches. Today Protestantism is one of the three major branches of Christianity. As the Reformation spread across Europe, it also inspired movements for political and social change.

(Source: Britannica article ' Reformation ')

Sessions of Vatican II were held in four successive autumns from 1962 to 1965. The most immediate result of Vatican II was the revision of the liturgy, which included changing the language of the liturgy from Latin to the languages of the people. Another prominent outcome was increased openness to other religions and denominations and cooperation with them.

(Source: Britannica article ' Vatican Councils ')

Key verses about the trinity

- 'There is no God but one.' ( 1 Corinthians 8:4 )

- 'The Father and I are one.' ( John 10:30 )

- Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit ( Matthew 28:19 )

- The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with all of you ( 2 Corinthians 13:13 )

- The angel said to her, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God. ( Luke 1:35 )

NOTE - the word 'trinity' is not found in the Bible. It is a technical word to describe the unique nature of God.

- Line by line explanation of the creed

Nicene Creed

We believe in one God, the Father, the Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, and of all that is, seen and unseen.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, one in Being with the Father. Through him all things were made. For us men and for our salvation, he came down from heaven: by the power of the Holy Spirit he was born of the Virgin Mary, and became man. For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate; he suffered, died, and was buried. On the third day he rose again in fulfillment of the Scriptures; he ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom will have no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son. With the Father and the Son he is worshipped and glorified. He has spoken through the Prophets. We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church. We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins. We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

Video - What is the catechism? (Duration 2:55)

- Catechism table of contents (Vatican website)

Quick Links

- << Previous: Passover

- Next: Year 9 >>

- Last Updated: Oct 31, 2023 5:52 PM

- URL: https://libguides.loretotoorak.vic.edu.au/religion

How to go to Heaven

How to get right with god.

What are some popular illustrations of the Holy Trinity?

For Further Study

Related articles, subscribe to the, question of the week.

Get our Question of the Week delivered right to your inbox!

Orthodox Arts Journal

Similar posts.

Sorted in order of similarity:

May 10, 2017 Divine Patterns in Story and Image pt.1

January 5, 2016 The Pictorial Metaphysics of the Icon: Part II

September 28, 2015 The State of Church Singing in America: An Interview with Choirmaster Benedict Sheehan

January 24, 2015 The problem of art in Anglophone Orthodoxy: a review essay

January 5, 2015 On the Gift of Art…Part IV: Challenges After the Clash

Visual Heresy – An Evangelical On The Iconography of God The Father

The Logo of the “Flying Spaghetti Monster Religion” shows Atheism to be the final result of believing God to be a an arbitrary “being” which either “exists” or does not “exist” within the sphere of knowledge.