Aristotelian Virtue Ethics

Aristotelian Virtue Ethics: Key Concepts

- Eudaimonia : Derived from Greek meaning ‘flourishing’, Aristotle used this term to refer to ultimate human goal or the ‘highest good’. It is often translated as ‘happiness’ in a broad sense.

- Virtue (Arete) : The character traits that enable us to function well as humans and thus achieve eudaimonia. Virtues are habits of behaviour that are developed through practice.

- Doctrine of the Mean : Aristotle’s approach to finding the balance between extremes in order to determine virtuous behaviour. Every virtue is a mean between two vices, one of excess and one of deficiency.

- Phronesis (Practical Wisdom) : The intellectual virtue needed to discern how best to act virtuously.

Understanding Aristotelian Virtue Ethics

- Virtue Ethics places focus on the character of the moral agent rather than the act itself (deontology) or the consequences of the act (consequentialism).

- Virtue ethics is agent-centred rather than action-centred. The ethical life is more about the person and their character than the actions they perform.

- Aristotle proposed that human beings have a purpose (telos) which is to achieve eudaimonia.

- Virtues are cultivated through habituation. In other words, by repeatedly performing virtuous actions, we become virtuous.

Criticisms of Aristotelian Virtue Ethics

- One key criticism is that Virtue Ethics is too vague and does not provide clear guidance on what actions should be taken in moral dilemmas.

- There are also issues relating to cultural relativism, as what is seen as a virtue in one culture might not be seen as such in another.

- Some might argue that the idea of a fixed human nature or telos is outdated and does not align with modern understandings of psychology and sociology.

Responses to the Criticisms

- In response to the criticism of vagueness, virtue ethicists argue that ethics requires a nuanced approach that takes into account the specific contexts and characters involved rather than prescribing a ‘one-size-fits-all’ rule.

- To the critique of cultural relativism, virtue ethicists may respond that while specific virtues might vary, the underlying values, such as respect, courage or kindness, can be universally applicable.

- As for the criticism of a fixed human nature, virtue ethicists might argue that while the specifics of human nature may evolve, the basic capacity for rationality and social interaction remains a cornerstone of humanity, which their theory accounts for.

Course Notes for Edexcel students on Virtue Ethics

From the Edexcel specification:

Aristotelian virtue ethics – historical and cultural influences on Virtue Ethics from its beginnings to modern developments of the theory, concepts of eudaemonia and living well, the golden mean, development of virtuous character, virtuous role models, vices, contemporary applications of virtue theories.

Virtue ethics is the theory that the foundation of morality is the development of good character traits or virtues. A person is good if he or she has virtues and lacks vices.

Historically, virtue theory is one of the oldest moral theories in Western philosophy and has its roots in ancient Greek civilisation. The Greek term for virtue is arete , which means ‘excellence’. Greek epic poets and playwrights, like Homer and Sophocles, described the morality of their heroes in terms of their virtues and vices.

Discussion of the virtues became more formal in the writings of Plato (427-347 BCE), who emphasised four particular virtues which later became known as the cardinal virtues : wisdom, courage, temperance and justice .

Like Freud, Plato thought that psychologically we are made up of three distinct parts: one that reasons, one that wills (motivates you to do things), and one that has appetites or desires (e.g. to eat or have sex). The job of our reason is to make sound judgements, and the job of the will is to support reason and make sure that our appetites don’t get out of control.

So we have wisdom when our reason is informed by a sound general knowledge of how to live. We have courage when our will always obeys our reason, regardless of what our appetites have to say. We have temperance when our reason governs our appetites. And we have justice when each part of our psyche does its job properly with reason in control. As these virtues are all closely related to the operations of the psyche, Plato was of the view that you could not have one without the other three. However, as it is possible to argue that terrorists and bank robbers have courage but lack wisdom, this claim can easily be challenged.

And as the details of Plato’s four cardinal virtues were so closely tied up with his view of the human personality, his theory has only had a limited impact. The more developed analysis of virtues was therefore left to his pupil Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE).

Aristotle’s account of virtue is found in his work The Nichomachean Ethics , which he named in honour of his son Nichomachus. There are several aspects to his theory.

First of all, he was deeply interested in the ideas of cause and purpose, and you have already explored his theory of the Four Causes, which surprisingly enough considers how things are caused and how they move towards a purpose. So first of all, he asserts that all human beings have a purpose in life, and that ethics involves attempting to identify that goal.

In ethics, any theory that looks at how we become better people over time, or how we move towards our purpose is called a teleological theory, from the Greek word telos meaning goal or purpose. Virtue ethics is teleological because it argues that we should practice being good, or virtuous people over time. Virtue ethics is therefore not deontological (like Kantian ethics), nor is it concerned exclusively with the consequences of our actions, as utilitarianism and situation ethics are. In other words, it is an agent-centred rather than an act-centred theory, which focuses on the self-development of the individual. It is also sometimes known as aretaic ethics (see above for the definition of arête, which can also mean ‘virtue’). Virtue ethics is not concerned with what we ought to do, but with what kind of person we should try to become.

Aristotle argued that the superior aim of human life is to achieve something called eudaimonia . Eudaimonia is a Greek word that roughly translates as ‘happiness’ or ‘flourishing’ , though what Aristotle has in mind should not be thought of as identical to the feelings sensations of happiness that utilitarians seek to produce through their moral decisions. Instead, our job is to become well-rounded, to develop and express our various potentials fully, including our potential to become moral, so as to achieve an overall state of well-being (which is a better description of what eudaimonia is). Eudaimonia is achieved when we become virtuous, and Aristotle argued that this is a process that we grow towards by practising the cultivation of virtues. It is rather like learning to play a musical instrument: the more you practice, the better you get. So morality in this case becomes a kind of skill that we can get better at over time.

The next step in Aristotle’s ethical theory involves identifying and describing the virtues themselves.

Aristotle believed that the correct way to live, was to follow something called the doctrine of the mean . Aristotle realised that human behaviour is made up of extremes which he called vices of excess and vices of deficiency . Aristotle argued that the best course of action falls between the two and that this is the virtue. For example, if courage is the virtue, then cowardice is the vice of deficiency and foolhardiness or rashness is the vice of excess. So the virtue of courage lies at the mean or middle between these vices. In this way, we can see that virtues are desire-regulating character traits that fall at some mid-point between extremes.

Mark Rowlands on the doctrine of the mean

In his book Everything I Know I Learned from TV: Philosophy for the Unrepentant Couch Potato , the philosopher Mark Rowlands gives a rather amusing account of this concept:

“Many people misunderstand this, and see it as some sort of depressing counsel of moderation: never go to extremes. Don’t do extreme things and don’t feel extreme emotions. Rather, let your actions and emotions fall in the middle range of what it is possible to do or feel. Be neither greatly elated nor greatly dejected. Fall neither violently in love nor out of love. In everything you do, be neither too enthusiastic nor too apathetic.

Neither I, nor you, I suspect, would want such a person as a friend. Such a person is basically on the philosophical equivalent of Prozac. They are average, middle-of-the-road, B-O-R-I-N-G! And they would never get invited to any good parties.

People often misunderstand Aristotle because they fail to distinguish something that Aristotle himself definitely did distinguish: two senses of the mean. On the one hand, there is what he called the mean in relation to the thing , and on the other the mean in relation to us . The mean in relation to the thing would be the mid-point between two extremes. Instead of drinking ten Cosmopolitans or drinking none, you take the middle option – the mean in relation to the thing – and drink five.

If you were looking to Aristotle for support in this policy you can look again. If you had read him properly you would realise that his doctrine of the mean is a doctrine of the mean in relation to us , not in relation to the thing . Understanding this is, however, no easy matter. This is Aristotle’s attempt to explain what he’s on about.

‘It is possible, for example, to feel fear, confidence, desire, anger, pity, and pleasure and pain generally, too much or too little; and both of these are wrong. But to have these feelings at the right times on the right grounds towards the right people for the right motive and in the right way is to feel them to an intermediate, that is to the best, degree; and this is the mark of virtue.’

Not exactly crystal clear, admittedly. But what Aristotle is getting at is that is that what you should feel, and so what you should do, is dependent on the circumstances that you find yourself in. So, your best friend has called you to go Cosmopolitan drinking because her boyfriend has just broken up with her on a Post-it. A pretty harrowing event, or so we’re led to believe. In these circumstances, the doctrine of the mean might legitimately – indeed rationally – call for a record breaking intake of Cosmopolitans. On the other hand, you may be going, not because of any harrowing event in particular, but simply because a window has opened up in your shoe-buying activities, one that you can’t think of any way to fill. The doctrine of the mean, in this case, might call for you to restrict yourself to one or two Cosmos, tops, or even mineral water!

The doctrine of the mean, as Aristotle intends it, calls for us to feel the right things at the right times on the right grounds towards the right people for the right motive and in the right way. Now all we have to do is work out the meaning of: ‘the right things’, ‘the right times’, ‘the right grounds’, ‘the right people’, ‘the right motive’ and ‘the right way’, and we’re laughing. And on these points of, apparently quite somewhat vital detail, Aristotle, like the true philosopher he is, gives us absolutely no help whatsoever. Great philosophers are like that.

For our purposes, what’s important is that to take from Aristotle is the idea that happiness is nor primarily a way of feeling but a way of being. And the specific way of being is living your life in accordance with reason, where reason is identified in terms of the idea of the mean in relation to us. It’s not a matter of having the warm, fuzzy feelings that most people think of as happiness. Rather it is to learn to deal with life in such a way as that we feel the right things, and so do the right things, in the right circumstances. Happiness is not, in essence, a way of feeling, but a way of dealing with the world where feeling and action cannot be separated. And for Aristotle, both are essential components of happiness.”

Aristotle believed that there are two types of virtue: intellectual virtues and moral virtues . The intellectual virtues are learned through instruction i.e. they are taught. The moral virtues are developed through habit . The intellectual virtues are developed in the rational part of the soul and the moral virtues are developed in the irrational part of the soul.

The 12 moral virtues, with their corresponding vices are set out in the table below.

NOTE: it is not necessary to memorise all the intellectual and moral virtues. So don’t feel intimidated by the above list. Just learn a couple of them that are easy to remember and explain with examples.

Of the moral virtues, the most important for Aristotle was self-respect. It involves having a respectful attitude about our self-worth in everything we do. For example, it is not appropriate for a self-respecting person to be cowardly when facing danger, or to be stingy about giving money.

It is also important to note that for Aristotle eudaimonia cannot be achieved in isolation. We can only develop the virtues through participation in society or citizenship, which at the time of Aristotle entailed involving oneself with the polis or city-based community that was typical of the time in which he lived. One reason for this is that in the process, we can encounter role models that exemplify the virtues who we can then seek to imitate. Virtuous friendships were also to be encouraged and celebrated. Our purpose in pursuing eudaimonia is therefore, in a sense, to aim to become a rational, virtuous and essentially sociable person.

Phronesis/ Practical wisdom

In real life situations, it can be difficult to pinpoint the mean between two extreme dispositions. Suppose that, in my quest to succeed at my job, I understand that a lack of ambition might eventually get me fired, but that too much ambition could destroy my home life (because I might become a workaholic). How much devotion should I show at my job?

Aristotle notes that it is difficult to live a virtuous life primarily because of the challenges involved in finding a mean in specific situations. He notes that calculating the mean isn’t simply a matter of working out an average e.g. by using the average number of hours worked by my fellow employees and then sticking to the result of that calculation myself.

Fortunately, there is a solution to the problem. Aristotle explains that an aspect of our ability to reason calculatively is phronesis , or practical wisdom , and this can help us to locate the virtuous mean. There are two aspects to phronesis . First of all, it entails keeping in mind our ultimate goal, to achieve eudaimonia. Secondly, it involves thinking carefully about the best way to attain this purpose.

So as far as cultivating the right kind of ambition in the workplace is concerned, this might mean that I have to figure out matters more specifically in a variety of situations. Appropriateness is the key here. For example, it might not be a good idea to give my immediate boss the impression that I am lazy by turning up late for work too often, nor would it be wise to apply for an internal promotion within the company for which I lack the relevant skills. Similarly, actually avoiding opportunities to impress my superiors through timidity, even though I do want to get on within the company, would not be a good policy. Ultimately though, it is only through experience that I can gain a sense of what is and isn’t appropriate, and trial and error may be needed to more carefully calibrate what my bosses expect from me in the way of ambition.

This is what Aristotle meant by phronesis . It is the wisdom that emerges gradually from this whole process which, if developed in the right way, will mean that the virtues we have cultivated are eventually expressed spontaneously, without any step-by-step rational prompting. For example, once I learn to be a safe driver, my roadway manners and skills become second nature to me, so that I slow down habitually before approaching a stop sign without consciously thinking about it, and know exactly when to pull into a busy stream of traffic, having previously overcome my initial fears and lack of confidence to gauge when to do so without putting other drivers at risk. Ultimately, if I am successful in this enterprise, I might become as morally adept in the sphere of ethics as a Michelin starred chef might be at turning out dishes of the highest calibre, or a jazz musician might be when it comes to improvising a solo on the instrument they play.

Christianity and the virtues

For almost 2,000 years, Greek notions of virtue – and especially Aristotle’s theory in particular – were central to Western conceptions of morality, and moral philosophers consistently emphasised the need to acquire good character traits that guide our actions and therefore make us good people. In the 17 th Century, however, interest in Aristotle’s version of virtue ethics declined. Instead, leading moral philosophers began to argue that virtues were only of secondary importance in explaining our moral obligations. Of greater importance was the need to formulate rational moral rules that could then guide our actions.

Along the way, virtue theory has also impacted on Christianity. The apostle Paul endorsed the virtues of faith , hope and charity , and they were later dubbed the theological virtues . These virtues, because they draw people into the life of God and are expressive of God are not accompanied by a vice of excess to be avoided. On this basis, Aquinas argued that only the theological virtues were truly perfect virtues; all others, such as those celebrated by Aristotle and Plato, were to be understood as ‘virtues in a restricted sense’. They can orient our lives toward what is good, but they cannot help us achieve our true purpose in life, which is no longer eudaimonia but friendship with the Triune God (God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit). The theological virtues are therefore superior to and complete the pagan virtues. Faith, hope and charity are ‘infused’ into human beings through the grace of God and reorder ‘pagan’ virtues such as wisdom, courage, temperance and justice. In other words, Aquinas is claiming that we cannot achieve moral excellence through our own efforts. God’s help is also required.

Modern Virtue Ethics

Elizabeth Anscombe

“Clad in leopard-skin trousers and a leather jacket, she might sit in silence for minutes on end, puffing on a cigar, after one of her students had finished reading out an essay.”

“For a time she sported a monocle, and had a trick of raising her eyebrows and letting it fall on her ample bosom, which somehow made her yet more daunting.”

‘If God does not exist, everything is permitted’ . The Russian novelist Dostoevsky never actually wrote that famous line, though so often is it attributed to him that he may as well have. And it points to a fundamental anxiety of the modern world.

The gradual death of God [in the sense of death of death of belief in God] has been one of the defining features of moral debate in the modern world, at the least in the West. This is because Christianity had previously provided the context within which intellectual, social and moral life was lived in Europe. To begin to unstitch faith, as philosophers from Hume onwards had started to do, seemed to many to unstitch society, and most especially to unstitch morality.

But what exactly is the problem with the death of God? For many thinkers, both believers and non-believers, the death of God poses the problem of how to do ethics if God does not exist.

One particular thinker who gave what many regard as an especially subtle answer to this question, was the Cambridge philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe. The real trouble with the death of God, she argued, was that most people, and moral philosophers in particular, had continued to act as if He were still alive.

Anscombe herself was deeply religious. She had converted to Catholicism as a teenager and she held highly conservative views on issues such as sex, marriage, homosexuality and abortion. But she recognized that much of the world had abandoned attachment to religious belief, apart from in a superficial sense. Yet moral theories, even overtly secular ones, were rooted in concepts that drew their force from a religious view of the world. The consequence, she argued, was moral incoherence.

In 1958 Anscombe published a paper called ‘Modern Moral Philosophy’ which has become one of the most influential of post-war philosophical works. It is the paper to which can be traced much of the modern interest in virtue ethics.

Anscombe made three main points in the paper. First, she argued that all the major British moral philosophers, from nineteenth century utilitarian Henry Sidgwick on, were essentially the same; they were all consequentialists , a term that Anscombe introduced into philosophical discourse in this paper.

Second, the concepts of moral obligation and of moral duty, and the use of the word ‘ought’ in a moral sense, were, Anscombe insisted, harmful and should be jettisoned. They were survivals from an earlier conception of ethics, an ethics rooted in belief in God. In the post-religious world, all moral theories, from Kantianism to Utilitarianism, made use of concepts such as ‘morally ought’ and ‘morally right’ but in a way that is devoid of meaning. In the ancient world the terms ‘should’ or ‘ought’ related to good and bad in the context of making things function better , whether ploughs or humans. The impact of monotheistic religion was to transform morality into a set of laws that had to be obeyed. Laws require a legislator and a police force. God was that legislator, the Church the enforcer. However, the modern world had dethroned God and weakened the institutions of faith. New forms of morality, such as Kantian ethics and Utilitarianism, still viewed morality in terms of rules or laws, but no longer had any figure that could play the role of the legislator or lawmaker. They lacked the proper foundations for the meaningful employment of their moral concepts. Morality, therefore, became incoherent.

And third, Anscombe drew attention to the fact that moral philosophy was in need of an adequate philosophy of psychology. Modern moral philosophies, she suggested, including Kantian ethics and Utilitarianism, are all rooted in shallow concepts of human nature and psychology. Any adequate moral framework had to be anchored by a realistic view of human aims, motivations, passions and capacities.

Anscombe’s paper has generally been understood to have pointed to the need for the development of an alternative theory of morality that does not attempt to retain the obsolete legal structure rooted in religiously-based ethics. A revival of Virtue Ethics was what Anscombe thought was needed to fill the gap, but a more fleshed out Virtue Ethics based on a fuller account of human nature and psychology that would better enable us to understand what ‘flourishing’ actually involves.

Anscombe’s argument about the root causes of moral incoherence and her suggestion that Virtue Ethics might be best place to address and correct this incoherence was later to be taken up by a number of philosophers, the most important of which was Alasdair MacIntyre.

Alasdair MacIntyre

NOTE: The following account is pretty much a cut and paste of a section of Kenan Malik’s The Quest for a Moral Compass: A Global History of Ethics , a superb publication.

Imagine that a series of environmental catastrophes has devastated the world. Blame for the disasters falls upon scientists, leading to widespread anti-science riots. Labs are burnt down, physicists and biologists lynched, books and instruments destroyed. A Know-nothing political movement comes to power, abolishes the teaching of science and imprisons and executes scientists.

Eventually there is an attempt to resurrect science. The trouble is that all that remains of scientific knowledge are a few fragments. People still debate the concept of relativity and the theory of evolution. They learn by rote the surviving portions of the periodic table, and use expressions such as ‘neutrino’, ’mass’ and ‘specific gravity’. Nobody, however, understands the beliefs that led to those theories or expressions, and nobody understands that they don’t understand them. The result is a kind of hollowed out science. On the surface everyone knows some scientific terminology but no one possesses scientific knowledge. So begins Alasdair MacIntyre’s provocative book 1981 book After Virtue .

MacIntyre’s ‘disquieting suggestion’ in After Virtue is that while no calamity of the sort he describes has befallen science, it is exactly what has happed to morality. True, no philosopher has been lynched, no seminar room torched, no riots have erupted in response to the disastrous consequences of Kantianism or Utilitarianism. Nevertheless, MacIntyre insists, moral thought is in the same state as science was in his imaginary future world, a state of ‘grave disorder’, and one in which the very disorder blinds us to the moral chaos that surrounds us. Everyone uses moral terms such as ‘ought’ and ‘should’, but no one truly understands them. Hence we argue endlessly about the justice of wars, the morality of abortion, the nature of freedom, but not only do we not reach agreement, we cannot even agree about what criteria a satisfactory resolution to these disagreements would need to meet. What caused this moral catastrophe? The Enlightenment.

The Age of Enlightenment (or simply ‘the Enlightenment’ or ‘Age of Reason’) was a cultural movement of intellectuals beginning in late 17 th century Western Europe emphasizing reason and individualism rather than tradition. Its purpose was to reform society using reason, to challenge ideas grounded in tradition and faith, and to advance knowledge through the scientific method. It promoted scientific thought, scepticism, and intellectual interchange. This new way of thinking was that rational thought begins with clearly stated principles, uses correct logic to arrive at conclusions, tests the conclusions against evidence, and then revises the principles in the light of the evidence.

The ‘thinkers of the Enlightenment’, MacIntyre observes (and here he has in mind philosophers like Kant, Bentham and Mill), ‘set out to replace what they took to be discredited traditional and superstitious forms of morality by a kind of secular morality that would be entitled to secure the assent of any rational person’, attempting to ‘formulate moral principles to which no adequately reflective rational person could refuse allegiance’. Instead what the Enlightenment ‘bequeathed to its cultural heirs were a mutually antagonistic moral stances [e.g. Kantian ethics versus Utilitarianism], each claiming to have achieved this kind of rational justification, but each also disputing this claim on the part of its rivals’.

The Enlightenment rejected, indeed destroyed, the Aristotelian notion of a virtuous life that had shaped Western thought for nearly two millennia. It rejected, in particular, the notion of the telos – the insistence, not just in Aristotle but in all ancient thinkers and in the monotheistic religions, that human beings, like all objects in the cosmos, exist for a purpose, and that to be good was to act in a way that enabled them to fulfil that purpose.

From Homer to Aristotle to Aquinas, the virtues were seen as excellences of character that enabled people to move towards their goals, and were, indeed, an essential part of achieving that goal.

Post-Enlightenment philosophers rejected all this, imagining humans not as creatures with definite functions that they might fulfil or neglect, but as agents who possessed no true purpose apart from that created by their own will; creatures governed, not by an external telos but solely by the dictates of their inner reason or desires. This shift away from community and tradition towards individualism has, MacIntyre argues, been corrosive of the very idea of morality. By appealing to a telos , Aristotle and Aquinas had been able to distinguish between the way we actually are and the way we should be. Post-Enlightenment philosophers could no longer coherently do so.

As a result they could find no moral anchor, no point of reference against which to adjudicate rival moral claims. And without such a point of reference, moral arguments are interminable and eventually become pointless. The end point in this journey comes with emotivism, the belief, associated most with the philosopher AJ Ayer, that moral statements are meaningless (in the sense that they are devoid of factual content and incapable of being proved true or false) and express merely the speaker’s feelings about the issue.

For an emotivist, to say ‘murder is wrong’ is no more than saying ‘murder, yuck!’ or or, as Ayer put it, to say it ‘in a peculiar tone of horror’, or to write it down ‘with the addition of some special exclamation marks.’ For Ayer, debates about moral issues are therefore little more than the equivalent of two snakes hissing at each other.

Emotivism, for MacIntyre is not simply a description of the theories produced by Ayer and his followers, but of all post-Enlightenment moral theories. Even those moral philosophies, such as Kantianism, that appeal to a rational standard binding on all, are deluding themselves because there is no possibility of such a standard given the Enlightenment view of the sovereignty of the individual moral agent. Post-Enlightenment liberal philosophers, MacIntyre suggests, have come to celebrate individual freedom and the detachment of the individual from their community. MacIntyre sees all this as disastrous.

In plainer language, what MacIntyre is saying is that in the modern world, people have become cut-off and isolated from their immediate communities. They have come to see themselves as free but isolated individuals whose main goal in life is to pursue their own pet projects in life. Other people are simply seen as resources that help or hinder the pursuit of those individual goals. The idea behind this individualism is that you are a sovereign person, with whom no one has the right to interfere (you can probably hear echoes of John Stuart Mill’s philosophy in this sentence). But other people are also weighing you up in exactly the same way. You are also merely a means to their self-fulfilment. And if you stop ticking their boxes, you know what is likely to happen.

And there is another problem. It is your choices that shape you, that allow you to become what you can be. You might, for example, decide to work your way on to the stand-up comedy circuit instead of becoming a lawyer. Or you could decide to go to Drama school instead of studying medicine. But if your choices are to be seen as meaningful, there has to be some independent standard against which to measure them. Unfortunately, MacIntyre seems to be saying, there is no longer any way of making sense of the choices we make that are like this. Our freedom is purchased at the price of subtracting all meaning from the choices we then make.

What is the solution for MacIntyre? How can we recover our moral compass and restore meaning to our lives?

In After Virtue , MacIntyre undertakes a historical study of the virtues in order to try to establish a system of virtue ethics for the modern age that will restore a sense of telos or purpose to our existence and provide moral standards in terms of our character development against which we can measure ourselves. Along the way, MacIntyre notes that the virtues tended to be expressions of specific communities that changed over time. For example, Greek society at the time of Homer regarded physical strength and an ability to be cunning as virtuous, as these attributes were valuable in times of war. But as cities (the polis) developed and life slowly became more civilised, both of these qualities came to be emphasised less and less.

MacIntyre argued that the Athenian virtues of Aristotle were the most complete, which included the following:

- Justice: retributive (getting what you deserve) and distributive (making sure that the goods of society are fairly distributed)

In her revision guide for one of the older A Level courses, Jill Oliphant notes that the three most important virtues that are still relevant today are justice , courage , and honesty . We will only achieve moral excellence through practising these three. They are core virtues that help to prevent organisations and institutions from becoming morally corrupt. It is mainly through institutions that traditions, cultures and morality spread; if these institutions are corrupt, then vices become widespread.

MacIntyre therefore sees a moral society as being one in which people recognise commonly agreed virtues and aspire to meet them. Those virtues improve and clarify themselves over time. Through participation in this communal quest, MacIntyre argues, moral claims become more than merely subjective, yet without being objective in a transcendental, deontological sense. The good moral life therefore consists not just in the goals that I set myself and the goods that I desire. It consists also in the goals and the goods of the community of which I am a part. It is that sense of community that allows me to rise above my own desires and to understand those desires in broader terms.

Buffy is a good example of what MacIntyre seems to be getting at. Although her immediate personal goal in life is to become a cheerleader, her less shallow, more identity-constituting telos in terms of the virtues of justice and courage celebrated within the community of vampire hunters, is to become a Slayer. Contrastingly, the vampires Buffy hunts are more like us: they just choose to do whatever they want, when they want to do it.

Philippa Foot

Foot pointed out that virtues can only be truly virtuous, good and valuable, in terms of both motive and action. Bad motives don’t count. So, for example, a bank robber might exhibit courage in carrying out a robbery but their motive for committing the crime, if it is purely and wantonly criminal, may disqualify their action from counting as virtuous.

Martha Nussbaum

It would seem that MacIntyre interprets virtue ethics in a relativistic way, as do most virtue ethicists. But the American philosopher Martha Nussbaum disagrees. She interprets Aristotle’s virtues as absolutes – she claims that justice, temperance etc. are essential elements of human flourishing across all societies and throughout time. Nussbaum is clear that she regards a relativist approach as incompatible with Aristotle’s virtue theory.

Rosalind Hursthouse

Hursthouse attempts to counters the claim that Aristotelean Virtue ethics does not offer enough specific guidance about how to make moral decisions (see below) and therefore cannot help with resolving moral dilemmas, by arguing that although the theory does not prescribe exactly how one might respond to a given situation, it does at least provide a framework for how one might think about a moral dilemma e.g. in terms of the Golden Mean?

Strengths and Weaknesses of Virtue Ethics (some taken from a variety of sources including previous revision guides)

- Virtues may not be easy to define with precision – they are too vague/ambiguous e.g. is it courageous to stay in a marriage that isn’t working or is it more courageous to seek counselling?

- Are the virtues relative to each culture and time? If so, they are unstable and may reflect the prejudices of a given time and place e.g. the celebration of women as virtuous homemakers prior to the emergence of feminism.

- As there are no rules for action, Virtue Ethics leaves it to ‘practical wisdom’ but does not say enough about what this entails in specific, crisis situations. However, it could be argued that rules do have a role to play in Virtue Ethics and therefore can provide more specific guidance. For example, Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean is a general principle that can steer us in the right direction when it comes to making moral decisions, even though it can be quite flexible and leave us to work out what conforming to the mean might involve in particular situations. Each virtue can also be seen as a standard against which to measure our behaviour and those of others. For example, an impatient motorist who curs off another driver in a moment of road rage can clearly be seen to be lacking in temperance. Finally, it seems to be a rule for both Aristotle and MacIntyre that we must see ourselves as being a part of a community and that we can only cultivate the virtues that contribute to eudaimonia through active citizenship.

- Virtue ethics could praise someone for courageously fighting an unjust war or using courage to rob a bank (a point made by Philippa Foot). So there is the problem of drawing on the right virtues for the wrong reasons and motives.

- But motives are hard to identify because they are hidden. An action may look good on the outside (e.g giving money to charity) but the motives might not be (e.g. someone might give to impress a friend or potential lover). This might make it difficult to assess Foot’s emphasis on matching motives with actions as all we can see are the actions. It also makes it difficult to know who is virtuous and could therefore be used in criticism of Foot.

- What about rights and obligations (duties)? Virtue Ethics could be accused of neglecting these important aspects of ethics. In other words, Virtue Ethics is too agent-centred.

- MacIntyre argues that it is the shared practices of a community which help cultivate virtues. But what if that community is racist? Or fascist? Or supports the Taliban?

- Compassion and empathy might be regarded as virtues but there are people in the world with these qualities who nevertheless end up making some situations worse. A good example of this type of person might be Mother Teresa who was almost certainly helping the poor and dying of overpopulated Calcutta with the best of intentions but whose Catholic faith prevented her from seeing the advantages that the availability of contraception might have in this kind of situation. For this kind of person (someone with a good heart but an empty head), Hursthouse’s emphasis on phronesis may be the only remedy.

- See also the important criticism of Virtue Ethics made by John Doris at the end of this handout.

Specific criticisms of Aristotle

- Must we always condemn those who do not follow Aristotle’s middle path and take things to extremes? And are such people always unfulfilled? For example, many business people thrive on taking risks, as do those who enjoy dangerous sports. Should we criticise this type of person for being reckless if what they are doing contributes to their own sense of eudaimonia? Similarly, introverts might said to be possessed of a vice of deficiency, because of their preference for being alone and not contributing to the polis. But perhaps their introversion can benefit society in other ways. For example, the French philosopher Montaigne (1533 – 1592) retired from public life in 1571 to the Tower of the Chateau, his so-called “citadel”, in the Dordogne, where he almost totally isolated himself from every social and family affair. Locked up in his library, he then produced a series of 107 philosophical essays on an extraordinary range of topics, including topics such as fatherhood, flatulence, cannibalism, cowardice, Socrates and smells, which have been regarded ever since as classics. Famous fans of Montaigne have even been said to have included Shakespeare. But could this body of famous work have been achieved if Montaigne had not retreated from the polis? This is doubtful.

- The connection Aristotle makes between cultivating and perfecting moral skills and happiness can also be questioned. This is because, while some people are obviously going to measure up quite well against Aristotle’s standards of virtue and may, for example, be courageous, sincere, even-tempered, and so on, they may also be unhappy, perhaps because of personal misfortunes over which they had no control. On the other hand, someone may be utterly without virtue and yet be happy. So it seems that there may not be a necessary causal connection between virtue and happiness.

- Aristotle’s idea of virtue ethics relies substantially on the effects role models have on people. Aristotle believes that we learn to be moral (virtuous) by modelling the behaviour of moral people. Through continual modelling we become virtuous out of habit. Of course, people can learn both good and bad habits depending on the role models they have. Aristotle believed that it was therefore the moral duty of every citizen to act as a good role model. However, deciding exactly who is worthy of imitation is fraught with difficulties. For example, Mother Teresa is cited in two A2 textbooks as an example of a virtuous role model, but her opposition to abortion and contraception and the fact that she associated with dictators like ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier in Haiti arguably means that she was lacking in phronesis . Meanwhile, within the Eastern Religious traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism, there have been many modern gurus, teachers of spiritual enlightenment, who have arguably exploited the followers who looked up to them financially, and sometimes even sexually. Famous examples are Osho Rajneesh and Chogyam Trungpa.

- In his most recent book, The Impossibility of Perfection , Slote claims that Aristotle’s ethics requires all the virtues to be had by a particular moral agent in their full perfection ( arête ). But, Slote says, certain virtues cannot be had in perfect measure, since their increase always involves a loss with regard to some opposite thing that we also regard highly as a virtue (he gives the examples ‘tact/frankness’, ‘prudence/adventurousness’, and ‘sexual pleasure/commitment’). He concludes that this shows that such virtues are inevitably ‘dependent’ and only‘partial’, not perfect virtues. Consequently, our idea of what a virtue is has to become more modest and balanced, at least in the particular cases he points out, and presumably in others as well. Slote believes that by showing the necessary imperfections of various virtues, and the impossibility of having them all at once, he can eliminate moral philosophy’s unfortunate tendency to be oriented only to perfectionist standards, and can thus create space for a more balanced, realistic set of virtues.

- Virtue Ethics avoids an overly prescriptive formula what we ought to do It focuses instead on the individual person and their inner strengths and values, along with a balancing emphasis on the importance of the culture, tradition and community within which that individual is embedded.

- Following rules doesn’t always make you a good person – someone who dissents from following the rules could be praised e.g Martin Luther King, anti-war protesters in Nazi Germany.

- This theory motivates people to examine themselves and their motives more carefully and encourages looking to others as virtuous role models and mentors. We can take inspiration from the most virtuous people, the moral heroes of history and without necessarily having to adopt their religious beliefs – e.g. we can aim to show agape or selfless concern for others by following the example of Jesus without necessarily buying into the notion that he was the Son of God. Note that this is a strength also identified by Anscombe – that Virtue Ethics can be made to appeal to everyone, regardless of whether they are religious or not.

- Developing virtues is arguably, a worthwhile, life-long activity.

- Affects our relationships, our work, our families, our values, our emotions. So it is holistic. And unlike Utilitarianism and Kantian ethics, Virtue Ethics might be said to be compatible with the bias we show to friends and family.

- Virtue ethics helps us to become a better person who is more likely to choose right over wrong.

- Virtue Ethics could also be said to emphasise citizenship and participation in the political process/local community and to discourage passivity. For Aristotle, it was only possible to develop virtues through practising them regularly and he thought that the best way to do that was to get involved with your immediate political community, the polis . In other words, just as a chef cannot learn her trade just by reading recipes, so we cannot learn how to be ethical just from reading books about it. We have do things like vote in elections, or join Neighbourhood Watch schemes. In this way we all help each other to cultivate virtue.

A Specific Strength of Aristotle

In recent times, counsellors, psychotherapists and ‘life-coaches’ have come to play an important role in our society, helping their clients to achieve eudaimonia . to flourish and live a better life by overcoming a variety of personal problems and issues. Interestingly, these problems frequently involve Aristotelian vices of deficiency and excess. Someone might, for example, consult with a psychotherapist in order to manage their anger more successfully, or to overcome timidity and shyness. So Aristotelian virtue ethics can provide a philosophical foundation for this kind of therapeutic work, while the therapists themselves can be said to guide their clients by using phronesis, whilst encouraging them to cultivate this quality themselves. MacIntyre may therefore have been premature to condemn the role of the therapist in modern society (in After Virtue , he argues that the therapist only helps to reinforce the shallow individualism of which he is so critical).

John Doris on Virtue Ethics

In his book Lack of Character , Doris argues that for most of us our virtuous character traits are less stable than we imagine and are, instead, remarkably sensitive to minor variations in our immediate environment that we may not even be aware of. How is this known? From famous studies in the territory of social psychology.

For example, Darley and Batson (1973) discovered that passersby in a hurry (theology students of all people!) would ignore and even step over a stricken person in their path, while unhurried passersby stopped to help. Similarly, passersby who found a bit of change (a dime in a phonebox) were shown by Isen and Levin (1972) to be more willing to stop to help a woman who had dropped her papers than passersby who were not similarly fortunate. Situations have also been found to have a potent effect on our willingness to inflict harm on others. For example, it has been demonstrated in many experiments that ordinary people are willing to torture a screaming victim at the polite request of an experimenter (see especially Milgram 1974), or perpetrate all manner of imaginative cruelties while serving as guards in a prison simulation (see Zimbardo et. al. 1973 – the famous Stanford Prison study).

This experimental record therefore suggests that situational factors are often better predictors of behaviour than personality characteristics. To put things crudely, people typically lack character.

Milgram’s research into obedience to authority also poses a challenge to Anscombe’s view. If we have a tendency to obey rather than challenge authority, even to the extent of going along with an experimenter’s request to continue administering dangerous electric shocks to an innocent stranger, then we might be better off subscribing to an ethical theories that oblige us to follow general moral laws (e.g. situation ethics, utilitarianism, natural law), even in the absence of a lawgiver.

It is, perhaps, lack of character that also explains things like the abuse of Iraqi detainees in Abu Ghraib prison, or why someone could be a loving father in the evening and a willing Nazi concentration camp guard during the day.

In summary, attempts to cultivate virtues might therefore be doomed to failure and we would arguably be better off learning more about how our environment tends to shape our moral behaviour.

ON THE OTHER HAND…..

There is also compelling evidence that virtues instilled in early childhood do tend to persist.

For example, the philosopher Theodore Adorno and his colleagues studied the psychology of ‘potential fascists’, people identified as such by their answers to questionnaires about Jews and other topics. The study suggested that such people often have an ‘authoritarian personality’, typified by rigidity of thought and behaviour, an emphasis on power and will rather than imagination and gentleness, superstitious thinking, rigid adherence to conventional values and aggression towards those who violate them. A central feature is a submissive, uncritical attitude towards authority. Those who scored highly on tests for the authoritarian personality tended to report having had a stricter upbringing rather than those who had a low score. The high scorers more often reported having dominant and disciplinarian fathers. Punishment for breaking rules played a big role. Neither emotional warmth nor reasoning about moral principles figured much in their accounts. Their descriptions of their parents were submissive and uncritical, but praise of them seemed conventional rather than showing real warmth.

In other words, when subjected to this kind of childhood, the adult who emerges from this process tends to be both strictly authoritarian themselves, and submissively unquestioning of people they consider to be their superiors. Both of these traits seem like unbalanced, opposing extremes on the Aristotelian scale, and would make someone like this vulnerable to the kind of manipulation that went on in Milgram’s study, and potentially an abusive jailer if that happened to be their assigned role in Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison experiment. What about people who stood up against the Nazis by giving assistance to Jews in World War Two? What makes someone more likely to do something like that even in the face of danger? Again, there is evidence that the roots of this attitude go back to childhood. Samuel and Pearl Oliner studied people who had rescued Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe and compared them with similarly placed people who had not given such help. They found, unsurprisingly, that their rescuers cared more than the others about people outside their families. Less obviously, the rescuers’ upbringing had been different from the others. The parents of the rescuers had set high standards for their children, especially about caring for others, but had not been strict. The emphasis was on reasoning rather than discipline.

So from the Oliner’s study, we learn that the virtues of caring for others and rationality seem to last if they are taught early, which in turn suggests that if the right kind of virtues are instilled in childhood, they stand a greater chance of withstanding the kind of pressures to conform that might be exerted later on. This, in turn, leads to the conclusion that Virtue Ethics may still represent a viable and realistic approach to doing ethics, in spite of Doris’s criticisms.

And finally….

It is well-known that some examiners are quite keen on Virtue Ethics. And the type of question that is set often involves describing and then exploring the relative merits of the ethical theories you have studied in a comparative way, to try to work out which of them, if any, is the best.

This extract from James Fieser’s book Moral Philosophy Through The Ages may therefore provide you with an interesting way of emphasising the importance of Virtue Ethics in moral decision-making, though you would need to spend no more than, say, five minutes and two concluding paragraphs of your essay getting it down on paper in the examination:

“Although we want to view virtue theory as only one of many approaches to morality, we should keep in mind virtue theory’s unique asset.

Imagine that, as a parent, you want to teach your child that it is wrong to become inappropriately enraged. When your child is older, you don’t want him to give in to road rage, beat his wife, or perform any other action that is the consequence of inappropriate anger. Imagine further that you have two teaching methods available. The first method established meticulous rules for what counts as inappropriate anger in virtually every circumstance. It also included rules describing the kinds of punishments that are justified for each type of violation. According to this first teaching method, your child memorizes all these rules so that, for each situation that arises, your child immediately knows the right thing to do. The second method doesn’t involve memorising specific rules but instead focuses on instilling good habits. Using various techniques, such as behaviour modification, you teach your child to avoid inappropriate action and become habituated toward appropriate action. You also give him techniques so he can properly modify his behaviour on his own, without your constant monitoring. All other factors being equal, which of these two methods would work best in preventing inappropriate anger? The habit-instilling method appears to be the winner.Virtue theorists capitalize on the benefits of teaching morality through creating virtuous habits. They argue that the most important thing about studying ethics is its impact on conduct. Aristotle himself said that he wrote the Nichomachean Ethics “not in order to know what virtue is, but in order to become good.” Detailed lists of rules in and of themselves don’t make us better people, but instilling good habits does. In 1993, attorney William J. Bennett edited an anthology entitled The Book of Virtues , which quickly became a best-seller. The work contains classic stories and folktales highlighting ten virtues, including self-discipline, compassion, responsibility, and friendship. Bennett says that the work is meant to assist in the “time-honored task of the moral education of the young.” Among the essential elements of moral training, he notes that “moral education must provide training in good habits. Aristotle wrote that good habits formed at youth make all the difference.”

In our actual lives as we raise our children, we will likely adopt a hybrid approach to teaching morality that involves both teaching rules and instilling good habits. The fact remains, though, that it is a mistake to completely ignore the benefits of virtue theory in moral instruction. Society needs all the help it can get in improving its moral climate. To that end, moral philosophers of all traditions should welcome the contributions of virtue theory.

What you could do here is to use this thought experiment to unfavourably compare Rule Utilitarianism (especially Strong Rule Utilitarianism) or Kantian Ethics with Virtue Ethics. A child brought up to be a Rule Utilitarian might then need to learn too many rules or Kantian maxims when they might be better off learning good habits.

You could then – as Fieser does – conclude that the raising of a child might require a hybrid approach, one that includes teaching some essential rules as well as the cultivation of various virtues.

This will make the examiner happy as you will have given a good reason for upholding Virtue Ethics as a vital moral theory whilst still finding space for utilitarian and Kantian thinking. And this same strategy might also work if you discussing hybrid ethical theories and need to come up with an overall conclusion.

Overview – Applied Ethics

Applied ethics takes the ethical theories we studied previously and applies them to practical moral issues. You may also be asked to apply metaethical theories to these issues.

The syllabus looks at 4 possible ethical applications:

Simulated killing

Eating animals, telling lies.

It’s pretty obvious what stealing is. But to frame it in a philosophical way, people often say that individuals have property rights – i.e. that they have rights over certain things. To steal is to violate these property rights.

Utilitarianism

For act utilitarianism , whether or not it is acceptable to steal something will depend on the situation. There is no moral right to property over and above its utilitarian benefits and so if an act of stealing results in a greater good then it would be morally acceptable to steal.

However, rule utilitarianism could argue that although there may be individual instances where stealing leads to greater happiness, having a rule of “don’t steal” leads to greater happiness overall. John Stuart Mill (the rule utilitarian person) makes a similar argument in his discussion of justice and property rights.

For example, a society that permitted stealing would be one in which no one could trust anyone. Everyone would live in constant fear of being robbed by someone who had convinced himself that stealing from them would lead to greater happiness. This distrust and fear would lead to a less happy society than one in which stealing isn’t allowed, and so a rule utilitarian could argue that we should follow the “don’t steal” rule.

Kant’s deontological ethics

Kant would argue that a maxim/rule that allowed stealing would fail the first test of the categorical imperative because it would lead to a contradiction in conception:

- The categorical imperative says: “act only according to maxims you can will would become a universal law “

- My maxim is: “I want to steal this thing”

- If I will stealing to be a universal law, then anyone could steal whenever they wanted

- But if anyone could steal whenever they wanted, the very concept of personal property wouldn’t exist (because if anyone is entitled to just take my property from me in what sense is it mine?)

- And if there is no such thing as personal property, the very concept of stealing doesn’t make sense (because you can’t steal something from someone if it isn’t theirs to begin with)

- Therefore, willing that “I want to steal this thing” leads to a contradiction in conception

- Therefore, stealing violates the categorical imperative

- Therefore, stealing is wrong

Aristotle’s virtue theory

Aristotle says there are some actions that never fall within the golden mean – and stealing is one of them. According to Aristotle, stealing is an injustice because it deprives a person what is justly and fairly theirs.

Even in extreme cases, such as stealing £1 from a billionaire to buy bread to save a starving child who will otherwise die, Aristotle would still likely say that stealing is wrong.

The reason for this is that Aristotle distinguishes between unjust actions and unjust states of affairs . A starving child may very well be an unjust state of affairs – an unfortunate situation – but that’s just the way the world is sometimes. According to Aristotle, it is much worse to deliberately and freely choose to commit unjust actions – even if you are committing these unjust actions to counteract unjust states of affairs.

- Naturalism: “Stealing is wrong” is true if stealing has the natural property of wrongness (e.g. because it causes sadness, and sadness is a natural property)

- Non-naturalism : “Stealing is wrong” is true if stealing has the non-natural property of wrongness

- Error theory: “Stealing is wrong” is false because the property of wrongness doesn’t exist

- Emotivism: “Stealing is wrong” just means “Boo! Stealing!” and so is not capable of being true or false

- Prescriptivism: “Stealing is wrong” means “Don’t steal!” and so is not capable of being true or false

Simulated killing is about fictional death and murder, such as in video games and films. It’s not about actually killing people (which is more obviously wrong).

This might seem like a non-issue at first – how can just watching or pretending to kill someone be bad? But there are all sorts of moral dimensions you can discuss. For example:

- The difference between watching a killing (e.g. in a film) and playing the role of the killer (e.g. in a video game)

- The effects simulated killing has on a person’s character (e.g. whether exposure to simulated killing makes them more violent)

- Whether simulated killing is wrong in itself (in the UK, for example, video games involving rape and paedophilia are illegal even though they’re just simulations – why not murder too?)

The obvious response of act utilitarianism would be that simulated killing is morally acceptable. After all, the person watching the film or playing the video game gets some enjoyment from the simulated killing, and the person being killed doesn’t actually suffer because it’s only fictional. In this situation, simulated killing results in a net gain of happiness.

But from a wider perspective, there are ways simulated killing could possibly decrease happiness. For example, if exposure to simulated killing makes a person more likely to kill someone for real, then maybe this pain would outweigh the happiness? Maybe simulated killing makes people more violent in general?

There are all sorts of studies on this topic, often with conflicting conclusions. If nothing else, these considerations support the difficult to apply objection to utilitarianism. However, if there was an obvious and irrefutable study that showed simulated killing makes people significantly more likely to murder in real life, then rule utilitarianism could say simulated killing is wrong.

Kant would most likely have no major objection to simulated killing. Murdering people in video games does not lead to a contradiction in conception , or a contradiction in will , or violate the humanity formula . In other words, simulated killing does not go against the categorical imperative .

However, Kant’s remarks on animal cruelty may be relevant here: He argues we have an imperfect duty to develop morally, which means cultivating feelings of compassion towards others. Simulated killing, like being cruel to animals, may weaken these feelings of compassion and so Kant could potentially argue we have a duty not to engage in simulated killing.

A key idea of Aristotle’s ethics is that virtue is a kind of practical wisdom (phronesis). According to Aristotle, being a good person is not just about knowing what the virtues are, it’s about acting on them until the virtues become habits.

So, Aristotle might argue that if someone spends a lot of time playing video games that involve simulated killing then they may develop bad habits (or at least not develop good habits/virtues). For example, repeatedly killing fictional innocent people in a game may make someone increasingly unkind or unjust. On the other hand, Aristotle might argue that killing fictional people is not actually unjust or unkind. After all, they’re not real, and so there’s no real injustice. Doing unjust acts develops the vice of injustice, but simulated killing is technically not an unjust act.

Like with any application of Aristotle’s ethics, you have to consider the context – there are no ‘one size fits all’ rules.

A virtuous person might partake in simulated killing in moderation as a form of entertainment and because they enjoy the competitive challenge of gaming. In that context, simulated killing might not be unvirtuous. But doing nothing with your life except killing people in video games just because you love killing people is almost definitely not virtuous.

- Naturalism: “Simulated killing is wrong” is true if simulated killing has the natural property of wrongness

- Non-naturalism : “Simulated killing is wrong” is true if simulated killing has the non-natural property of wrongness

- Error theory: “Simulated killing is wrong” is false because the property of wrongness doesn’t exist

- Emotivism: “Simulated killing is wrong” just means “Boo! Simulated killing!” and so is not capable of being true or false

- Prescriptivism: “Simulated killing is wrong” means “Don’t do simulated killing!” and so is not capable of being true or false

A conclusion of Bentham’s view that good = happiness is that utilitarian principles must be extended to animals (because animals can feel pleasure and pain just as humans can). Bentham says:

“The question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? Why should the law refuse its protection to any sensitive being?” – An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation

Peter Singer, another utilitarian philosopher, develops this line of thinking further. To privilege human pain and pleasure over animals is speciesist , he says (in a similar way to how privileging men over women, say, is sexist).

There are, however, ways a utilitarianism could potentially justify eating animals.

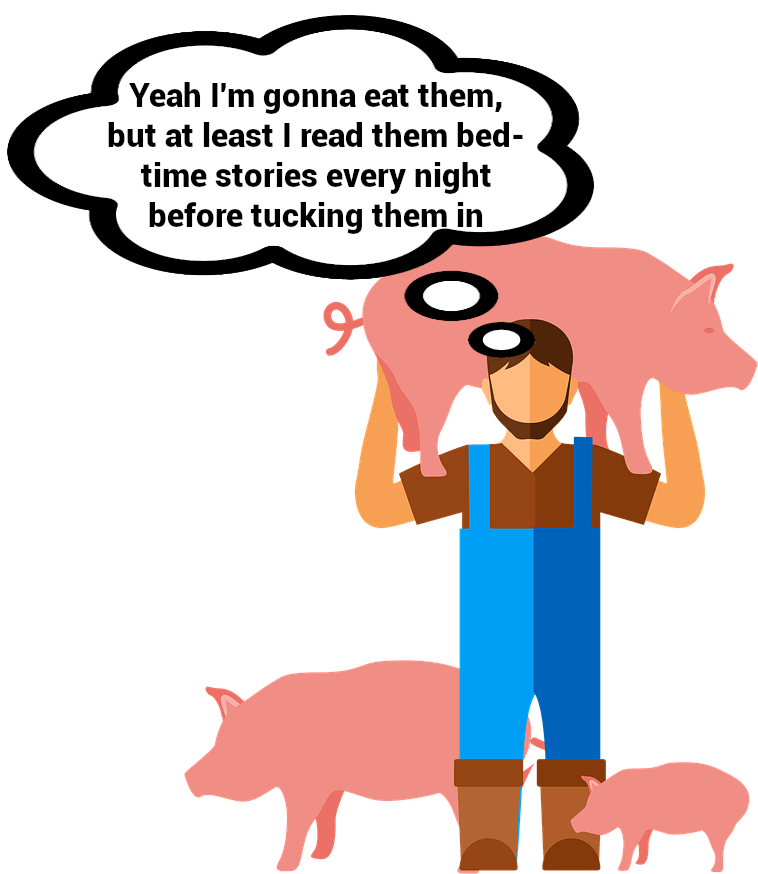

According to utilitarianism, an action is good if it results in maximises pleasure and minimises pain. And you could argue that, if it wasn’t for farming animals for food, many animals would never have existed and so would never have been able to experience pleasure and pain in the first place. So, if the animals farmed for food have an overall happy life and a painless death, then eating animals is morally justifiable because it results in a net increase of pleasure.

An implication of this view is that farming conditions and practices are important. Farming animals in cramped or uncomfortable conditions where they have unhappy lives, say, would be morally wrong according to utilitarianism.

Kant’s categorical imperative is only intended to apply to rational beings. Animals, Kant would say, do not have rational will and so are excluded from the categorical imperative.

Kant would say there is no contradiction in conception and no contradiction in will that results from the maxim “to eat animals”. And the humanity formula only says don’t treat humanity as a means to an end. Humans have a rational will and so are ends in themselves and should be treated as such. But animals, Kant would say, do not have a rational will and so can be treated solely as means. We thus do not have any duties towards animals.

However, Kant does argue that being cruel to animals violates a duty we have towards ourselves – the duty to develop morally:

“violent and cruel treatment of animals is far more intimately opposed to a human being’s duty to himself … and he has a duty to refrain from this; for it dulls his shared feeling of their suffering and so weakens and gradually uproots a natural predisposition that is very serviceable to morality” – Metaphysics of Morals

According to Kant, Moral development involves developing compassion for other human beings but being cruel to animals weakens these feelings. So, even though we don’t have any duties directly towards animals, we do have duties in regards to them . As such, Kant might morally object to cruel farming practices but would not object to eating animals in principle.

Aristotle’s discussion of eudaimonia is concerned with the good life for human beings specifically. Animals, unlike humans, are not capable of reason and so eudaimonia doesn’t apply to them. So, Aristotle would likely not see any issue with eating animals.

But some more recent virtue ethics philosophers take a different approach to this. Cora Diamond, for example, argues that eating animals is wrong – but acknowledges degrees to which different practices around eating animals are good or bad:

“To put it at its simplest by an example, a friend of mine raises his own pigs; they have quite a good life, and he shoots and butchers them with help from a neighbour… This is obviously in some ways very different from picking up one of the several billion chicken- breasts of 1978 America out of your supermarket freezer. So when I speak of eating animals I mean a lot of different cases, and what I say will apply to some more than others.” – Eating Meat and Eating People

So, in summary, virtue ethics might acknowledge this and argue that whether eating animals is acceptable depends on if it is done in the right way and for the right reason. Eating animals might sometimes fall within the golden mean , but not always.

- Naturalism: “Eating animals is wrong” is true if eating animals has the natural property of wrongness (e.g. because wrongness is a natural property such as pain)

- Non-naturalism : “Eating animals is wrong” is true if eating animals has the non-natural property of wrongness

- Error theory: “Eating animals is wrong” is false because the property of wrongness doesn’t exist

- Emotivism: “Eating animals is wrong” just means “Boo! Eating animals!” and so is not capable of being true or false

- Prescriptivism: “Eating animals is wrong” means “Don’t eat animals!” and so is not capable of being true or false

As always, whether or not act utilitarianism would say it’s morally acceptable to lie will depend on the situation. If telling a lie leads to greater happiness, then act utilitarianism would say you should lie. For example, if someone asks you whether they look good and they don’t, the utilitarian thing to do is to lie and say “yes”.

But rule utilitarianism could argue that a rule to “never lie” would lead to greater happiness than a rule that allows everyone to lie. For example, if everyone was an act utilitarian and always lied to increase happiness/reduce pain, then nobody could trust anything anyone said. And the rule utilitarian could argue that such a society – where no one can trust anyone else’s word – would be less happy overall.

The point of telling a lie is to get the other person to believe something false. But if everyone always told lies, then people wouldn’t believe each other.

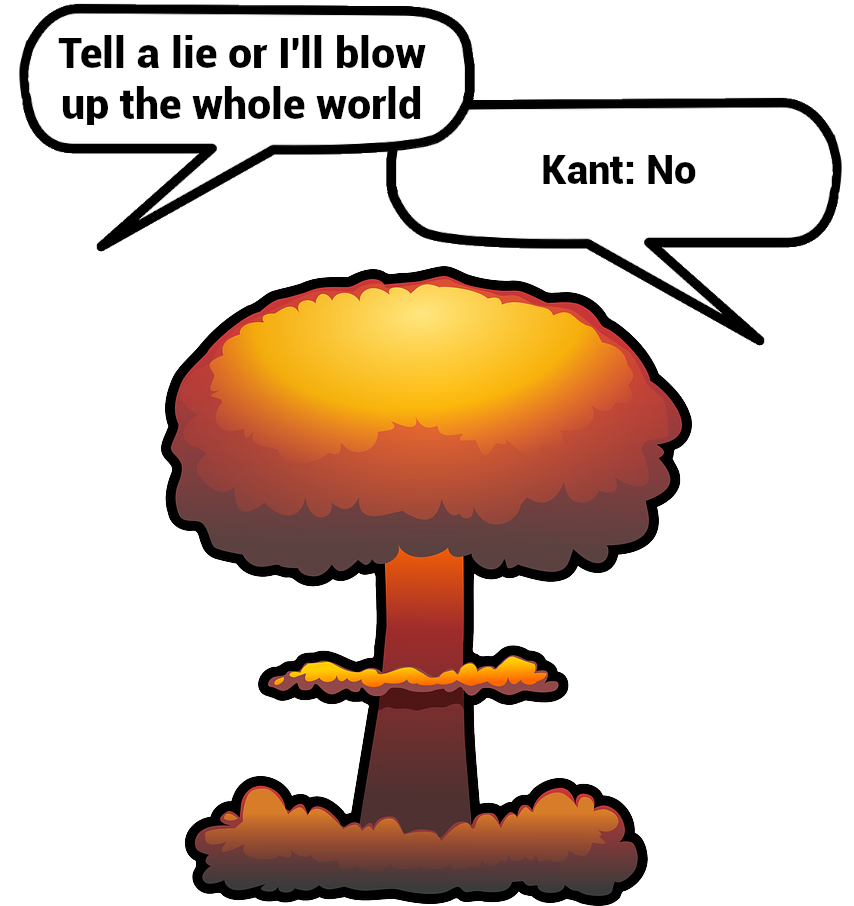

French philosopher Benjamin Constant challenged Kant’s approach of radical honesty by asking whether you should tell a known murderer the location of his victim when asked. Say, for example, a person is escaping an axe-murderer and you let them hide in your house. Shortly after, a crazy looking guy with an axe and blood-stained clothes asks you “where is he?” According to Kant, you should tell the truth: “He’s in here.” Telling the truth in this situation is seemingly the wrong thing to do, though, and so Kant’s ethics cannot be the correct account of moral action.

Kant’s response to this example is to stick to his guns: You should not lie to the murderer even to save a life. One reason for this is that Kant says the moral worth of actions is determined by whether they are done for the sake of duty , not their consequences. Further, in his essay on lying, Kant argues that it is impossible to know the consequences of our actions. But if we choose not to follow our duty and decide to lie, then we can be held responsible for the consequences. So say, for example, you lie and tell the axe murderer that “he’s next door” and, unbeknown to you the victim has sneaked out and really has gone next door, then you do bear some responsibility for the consequences of not following your duty.

In his discussion of the ‘social qualities’ of truth and falsehood, Aristotle says:

“ Falsehood is in itself bad and reprehensible, while the truth is a fine and praiseworthy thing; accordingly, the sincere man, who holds the mean position, is praiseworthy, while both the deceivers are to be censured” – The Nichomachean Ethics, Book IV.VII

Aristotle is talking about lying about oneself: On one side boasting is a vice of excess, and on the other false modesty is a vice of deficiency. Telling the truth – i.e. “the sincere man” – is in the middle (i.e. the golden mean) and so is the virtuous action.

When Aristotle says “falsehood is in itself bad”, he appears to be saying that lying is always wrong. However, Aristotle later describes degrees to which telling lies is bad: Lying to protect your reputation, for example, is not as bad as lying to gain money. Given this, you could potentially argue that there may be situations where it is morally acceptable to lie, such as in the example of saving a life above.

- Naturalism: “Telling lies is wrong” is true if telling lies has the natural property of wrongness

- Non-naturalism : “Telling lies is wrong” is true if telling lies has the non-natural property of wrongness

- Error theory: “Telling lies is wrong” is false because the property of wrongness doesn’t exist

- Emotivism: “Telling lies is wrong” just means “Boo! Telling lies!” and so is not capable of being true or false

- Prescriptivism: “Telling lies is wrong” means “Don’t tell lies!” and so is not capable of being true or false

<<<Metaethics

A Level Philosophy & Religious Studies

Model essay plan for Applied Ethics

AQA Philosophy model essay plan

Note that this is merely one possible way to write an essay on this topic

Points highlighted in light blue are integration points Points highlighted in green are weighting points

I haven’t completely finished this – but it should give you a clear idea about how to approach applied ethics 25 mark questions.

General applied ethics question

General applied ethics questions will focus on one of the applied ethics issues and ask about the morality of it. E.g.:

Is simulated killing wrong? [25] Is it ever morally acceptable to eat animals? [25] Could stealing be morally justified? [25] “Lying is good” – assess this view [25]

Your goal needs to be to pick one or two ethical theories (or meta-ethical if you want a headache). They will have an answer to the question – e.g. Kant will have a view on whether lying is good. You then have to assess the ethical theory in order to assess their answer to the question about the applied ethics issue. E.g. Kant says lying is wrong, but his theory faces issues. If those issues succeed, then Kant’s answer to the question fails. If they do not succeed, then Kant’s answer is the right one that we should conclude is correct.

Virtue ethics

- Virtue ethics is the view that an action is good if it is what a virtuous person would do.

- The goal of human action is eudaimonia which means flourishing or living a good life.

- We achieve this when we act as rational beings, guided by reason.

- Virtues are character traits or dispositions of habit which enable us to achieve our function.

Application of virtue ethics

- Eating animals

- Simulated killing

Criticism of virtue ethics

- The issue of clear guidance

- Aristotle’s flexibility in taking the situation into account comes at the cost of sacrificing the clarity of guidance provided.

- Virtue ethics tells us how to become a good person, but not what to actually do.

- Aristotle claims that this approach is the best possible, because of how messy and complex moral situations can be.

- However, that argument only works against deontological theories. Utilitarianism takes the situation into account like Virtue ethics does, and yet also provides clearer guidance. Bentham provides a method/algorithm for calculating exactly what action we should do.

- Aristotle merely says we should do whatever a virtuous person would do. That guidance is less clear.

- Aristotle explains that through our actions we could cultivate virtues like friendliness & courage, but he doesn’t explain how to calculate which action would actually cultivate the virtues. The lack of clear guidance is in the connection between virtue and actions.

Illustration of the issue’s relevance to the applied ethics issues

- Aristotle tells us the best ethics can do is reduce to being a good person, but other ethical theories show that clearer guidance is actually possible while taking the situation into account.

Utilitarianism

- Outline Utilitarianism (Bentham’s Act Util & hedonic calculus) and

- explain Bentham’s view on the ethical issue

- Criticize Utilitarianism with the issue of calculation.

- Utilitarianism faces its own issues regarding practicality.

- To weigh up how much pleasure/pain an action will produce – surely we need to know the future – which we can’t – nor can we easily measure subjective mental states or do any of this calculation in time-sensitive conditions.

- Defend Util: Mill’s version of Util – Rule utilitarianism –

- weighting point that it is stronger than act because it doesn’t rely on calculating every single moral action that we do.

- Follow the social rule regarding stealing, lying, simulating killing or eating animals which maximises happiness.

- There should be a rule against stealing and lying. There should be a rule that if you want to simulate killing, you have to be psychologically screened first. The rule about eating animals is that so long as they have a happy life, are killed humanely and don’t contribute to climate change, then it is morally acceptable.

Further evaluation of utilitarianism

- Explain Nozick’s experience machine (more crucial argument than the calculation issue – because it attacks the foundational premise of Util). Bentham (and Mill) claim that happiness/pleasure is our ultimate and sole desire – this is the basis of their argument for concluding that goodness is pleasure/happiness, from which they derive the principle of utility – that an action is good if it maximises happiness – hedonic – Utilitarianism.

- However – Nozick points out that if this were true – that pleasure is our ultimate desire – then we would all plug into a machine that created fake but purely pleasurable experiences.

- Nozick claims that many people would not plug into this machine – thus proving Utilitarianism false.

- This means that the judgement Utilitarianism provided on the applied ethics issue [animals, lying, stealing, simulated killing] is also false.

- [note – although Nozick’s argument has no relevance to the applied ethics issues – it does show utilitarianism is false, and thereby indirectly undermines Utilitarianism’s judgement on the applied ethics issue, which answers the question].

Evaluation:

- Nozick’s criticism only works against hedonistic forms of Utilitarianism. Preference Utilitarianism doesn’t try to claim that happiness or pleasure is the ultimate good. It claims that an action is good if it maximises the satisfaction of preferences of all morally relevant individuals.

- In that case, some people might prefer to enter the machine and others might not prefer to. This is no issue for preference Utilitarianism, since in either case people are satisfying their preferences, either for a fake life of pleasure, or a real life of pleasure and suffering.

Specific applied ethics question