- Skip navigation and go to content

- Go to navigation

Rose O’Neill

Born: june 25, 1874 | died: april 6, 1944.

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania and raised in rural Nebraska, Rose O'Neill (1874-1944) taught herself how to draw, achieved success at a young age, gained tremendous wealth from the creation of Kewpie dolls, and contributed to the women's suffrage movement. She created the first comic strip published by a woman in the United States, was married and divorced twice, and hosted events for celebrated authors, artists, and poets of the day, including James Montgomery Flagg , Edwin Arlington Robinson, Khalil Gibran, and Booth Tarkington, before settling down in the Ozarks region of Missouri.

O'Neill was raised in an artistic household where she was encouraged by her father to recite Shakespeare, read classics like Ivanhoe , and attend theater performances. [1] She first achieved artistic success at the age of thirteen when she won a drawing prize from the Omaha World-Herald . The editors were so convinced O'Neill copied the work from another source that they required her to come to the newspaper office and draw illustrations in their presence. [2] She continued to hone her craft during her teenage years and several newspapers in the region published her illustrations. At the age of nineteen, O'Neill moved from Nebraska to New York City where she hoped her illustration career would flourish.

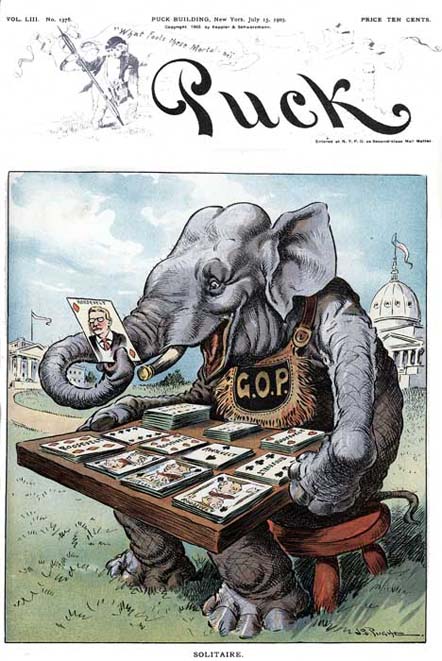

While living in a convent, O'Neill recalled the nuns would accompany her to meet with newspaper and magazine editors. Her work was soon published in the pages of Truth , Life , Harper's Bazaar , Cosmopolitan , Good Housekeeping , and other magazines. A comic strip O'Neill wrote titled "The Old Subscriber Calls" was printed in the September 19, 1896 issue of Truth , which was remarkable in that it was the first published comic strip created by a woman. [3] Her cartoons became so popular that she was asked to join the staff of Puck , where she was the only woman working from 1897 to 1903. [4]

In the same year her first comic strip was published, O'Neill married Gray Latham. Although Latham was from a wealthy Virginia family, his habit of collecting O'Neill's pay from her magazine submissions and spending it without her approval took a toll on their marriage and they divorced in 1901. [5] While her marriage to Latham was nearing its end, O'Neill began receiving affectionately written anonymous letters. The source of the letters was Harry Leon Wilson, an editor at Puck magazine. They were married in 1902. Wilson was a talented author, writing some of his books at O'Neill's Bonniebrook home in the Ozark Mountains of Missouri. According to O'Neill's autobiography, Wilson appears to have suffered from major depression at a time when there was little relief; his melancholy doomed their marriage and they were divorced in 1907. [6]

O'Neill's most popular creation was born in 1909, although similar figures had appeared in her work for several years. The Kewpies, named after Cupid, the Roman god of love, were child-like, winged, Elfish creatures sporting a topknot hairstyle. They were prominently featured in the pages of Good Housekeeping and Woman's Home Companion . The Kewpies were an instant success and the public showed a demand for Kewpie dolls, which O'Neill began producing with a factory in Germany. Over the next several years, O'Neill became a millionaire from the sales of the dolls, allowing her to afford homes in New York, Connecticut, Missouri, and Italy. Meanwhile, O'Neill continued her career in illustration and became the top artist for Jell-O, in addition to creating ad images for several other companies, such as Kelloggs's Corn Flakes and Eastman Kodak.

Beginning in 1915, while living with her sister, Callista, at an apartment in New York's Greenwich Village, O'Neill became involved with the women's suffrage movement. She marched in parades, gave speeches, and illustrated posters for the movement. The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which affirmed women had the right to vote, was passed by the Senate in 1919 and ratified by the states in 1920.

O'Neill admittedly aspired to become a fine artist whose work would be exhibited in museums. She studied in Europe for several years (including under Auguste Rodin ) and created a series of "monster" drawings which depicted dark, surrealistic scenes drawn from mythology and her subconscious mind. These works were exhibited in galleries and museums throughout Western Europe and at the Society of Illustrators in New York, where she became the only female fellow. [7]

Rose O'Neill died in 1944 and was buried at her beloved Bonniebrook home in the Ozarks.

[1] Rose O'Neill and Miriam Formanek-Brunell, The Story of Rose O'Neill: An Autobiography (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1997), 38.

[2] Ibid., 44.

[3] Sarah Buhr, Frolic of the Mind: The Illustrious Life of Rose O'Neill (Springfield, MO: Springfield Art Museum, 2018), 11.

[4] O'Neill and Formanek-Brunell, The Story of Rose O'Neill: An Autobiography , 16.

[5] Ibid., 74.

[6] Ibid., 88.

[7] Buhr, Frolic of the Mind: The Illustrious Life of Rose O'Neill , 35.

Illustrations by Rose O’Neill

Additional Resources

- Stripper’s Guide

- Yesterday’s Papers

Bibliography

Armitage, Shelley. Kewpies and Beyond: The World of Rose O'Neill . Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

Buhr, Sarah. Frolic of the Mind: The Illustrious Life of Rose O'Neill . Springfield, MO: Springfield Art Museum, 2018.

Kowalski, Jesse. Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration . New York: Abbeville Press, 2020.

O'Neill, David. Collecting Rose O'Neill's Kewpies . Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publications, 2003.

O'Neill, Rose. The Kewpie Kutouts . New York: F.A. Stokes, 1914.

O'Neill, Rose. The Kewpies and the Runaway Baby . Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1928.

O'Neill, Rose. The Loves of Edwy . Rockville, MD: Wildside, 1904.

O'Neill, Rose and Miriam Formanek-Brunell. The Story of Rose O'Neill: An Autobiography . Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1997.

RELATED ARTISTS

Related Time Periods

Top of page

Rose O’Neill: Artist, Activist, and Queen of Kewpies

March 24, 2020

Posted by: Heather Thomas

Share this post:

Rose Cecil O’Neill was an iconoclast in every sense of the word. A self-taught bohemian artist, who ascended through a male-dominated field to become a top illustrator and the first to build a merchandising empire from her work, with her invention of the Kewpie doll. As a young woman coming of age in the late 19 th century, Rose redefined what a female artist of the time could achieve both creatively and commercially.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1874, O’Neill relocated with her family by covered wagon to rural Nebraska. She began drawing in childhood and, at age 13, won a newspaper drawing contest in her adopted hometown of Omaha. At just 18, and with no formal art education, had her drawings published in newspapers and magazines throughout the Midwest. Within the year, she moved to New York with hopes of launching a career as an artist.

Settled in Manhattan, O’Neill quickly made a name for herself as a commercial illustrator, publishing in national magazines such as Life , Ladies’ Home Journal and Harper’s Monthly . At 23, she became the first woman artist on staff at the leading humor magazine Puck . She was now earning top dollar for her work, making her one of the highest paid illustrators in New York.

At the same time, O’Neill remained dedicated to her own creativity fulfilling art . As a sculptor and a painter, she exhibited her work in New York and Paris. As a novelist and poet, she published eight novels and several children’s books

O’Neill also was an activist for women’s issues. She marched as a suffragist and illustrated posters, postcards and political cartoons for the cause. She championed dress reform, choosing to be brazenly corset-less underneath loose caftans.

In 1907, O’Neill began developing short illustrated stories featuring cherubic characters, who “did good deeds in a humorous way.” The comic strip “The Kewpies” premiered in Ladies’ Home Journal in 1909 and was an instant hit. The strip’s spectacular popularity inspired her to envision the Kewpie as a doll. Kewpie dolls hit the shelves in 1913 and immediately became a phenomenon—it took factories in six different countries to fill orders . The Kewpie became the first novelty toy distributed worldwide and earned O’Neill a fortune.

Wealthy beyond her dreams, O’Neill retreated to Castle Carabas, a lavish villa in rural Connecticut, where she entertained artists and other exotic visitors. Over time, O’Neill’s generosity and extravagant living depleted her funds. In 1941, she moved into a family home in Missouri to work on her memoirs and died in 1944 , penniless.

For over a century, the Kewpie remained an icon of American popular culture. The vitality and versatility packed into O’Neill’s lifetime ensured that her contribution to American culture would continue to stand the test of time.

Discover more:

- Search Chronicling America * to find newspaper coverage of Rose O’Neill, Kewpies, and more!

- “Hidden Figures of Women’s History,” Library of Congress Magazine , March/April 2018

- View prints of Kewpies and other artwork by Rose O’Neill searching the Library’s Prints & Photographs online catalog .

* The Chronicling America historic newspapers online collection is a product of the National Digital Newspaper Program and jointly sponsored by the Library and the National Endowment for the Humanities .

Comments (6)

I’ve always loved Kewpies, but I never knew about the woman behind the creation. What an amazing and unique woman!

You might add Kewpies and Beyond: The World of Rose O’Neill to your suggested reading list. This is the canonical scholarly text (but readable) on O’Neill providing critical biography and chock full of period illustrations difficult to find otherwise.

Thank you Shelley! I have seen this biography, great read!

My BFF is one of Rose O’Neill’s granddaughters!

I have an original Rose O’Neill drawing was given to me by Robert Haas before his death. It is framed beautifully, I’m looking to sell it.

I forgot to add that Robert Haas was the president of the Kewpie association. For many years, his collection was sold in Kansas City by the Pence auction company. I was gifted an original charcoal drawing that is absolutely beautiful and framed beautifully by Bob house. I donated all of the records to the Rose O’Neill Museum.

See All Comments

Add a Comment Cancel reply

This blog is governed by the general rules of respectful civil discourse. You are fully responsible for everything that you post. The content of all comments is released into the public domain unless clearly stated otherwise. The Library of Congress does not control the content posted. Nevertheless, the Library of Congress may monitor any user-generated content as it chooses and reserves the right to remove content for any reason whatever, without consent. Gratuitous links to sites are viewed as spam and may result in removed comments. We further reserve the right, in our sole discretion, to remove a user's privilege to post content on the Library site. Read our Comment and Posting Policy .

Required fields are indicated with an * asterisk.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Do adults read children's literature?

- When did American literature begin?

- Who are some important authors of American literature?

- What are the periods of American literature?

Rose Cecil O’Neill

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Lemelson-MIT Program - Biography of Rose O'Neill

- Rose Cecil O’Neill - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Rose Cecil O’Neill (born June 25, 1874, Wilkes-Barre , Pennsylvania , U.S.—died April 6, 1944, Springfield , Missouri) was an American illustrator, writer, and businesswoman remembered largely for her creation and highly successful marketing of Kewpie characters and Kewpie dolls .

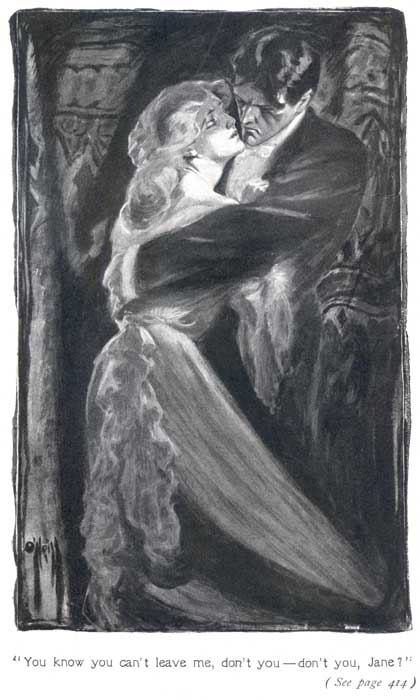

O’Neill grew up in Battle Creek , Michigan, and in Omaha , Nebraska . The attention she earned with a prizewinning drawing for the Omaha World-Herald , created when she was 14, inspired her to sell other drawings to the newspaper and to the Great Divide magazine of Denver, Colorado . In 1893 she moved to New York City , where she sold drawings to Truth , Puck , Cosmopolitan , and other magazines. In 1896 she married Gray Latham (divorced 1901). During the marriage she signed her work “O’Neill Latham.” In 1902 she married the editor of Puck , Harry Leon Wilson (divorced 1907), and she illustrated several of his books. In addition to her illustrations for Good Housekeeping , Life , Collier’s , and other leading magazines, which brought her a substantial income, she wrote the novels The Loves of Edwy (1904) and The Lady in the White Veil (1909).

O’Neill became wealthy and famous through her Kewpies, sentimental little Cupid figures to which the Ladies’ Home Journal , under the editorship of Edward Bok , devoted a full page in December 1909. The Kewpies and their adventures quickly became a national rage, and from drawing them she moved on to marketing a line of Kewpie dolls, patented in 1913. These modernized American Cupids swept the country, and royalties from their sales and from the books Kewpies and Dottie Darling (1913), Kewpies: Their Book, Verse, and Poetry (1913), Kewpie Kutouts (1914), and Kewpies and the Runaway Baby (1928) allowed O’Neill all the leisure she required for painting in her Washington Square studio or in her villa on Capri; to entertain flamboyantly at Carabas Castle, her home in Westport, Connecticut; and to write poetry and extremely Gothic romances. Her serious drawings, exhibited at the Galerie Devambez in Paris in 1921, helped bring about her election to the Société des Beaux Arts. She also dabbled in monumental sculpture. Late in life, having squandered her money, she retired to Bonnie Brook, her family’s homestead in the Ozark hills of Missouri .

Rose O’Neill

Rose O'Neill

Introduction

Rose O’Neill was a self-trained artist who periodically lived in the Missouri Ozarks throughout her adult life. She built a successful career as a magazine and book illustrator and, at a young age, became the best-known and highest-paid female commercial illustrator in the United States. She also wrote novels and poetry. O’Neill earned a fortune and international fame by creating the Kewpie, the most widely known cartoon character until Mickey Mouse.

Early Years

Rose Cecil O’Neill was born on June 25, 1874, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Her parents were William Patrick Henry and Alice Cecilia Asenath Senia Smith O’Neill. She had two sisters—Lee and Callista—and three brothers—Hugh, James, and Clarence. O’Neill’s father was a bookseller of Irish descent who loved literature, art, and theatre. Her mother was a gifted musician, actress, and teacher. As a young girl, O’Neill traveled with her family in a Conestoga wagon to rural Nebraska. There she grew up in a loving family that actively supported each member’s artistic and intellectual interests.

O'Neill Family

Rose’s family members and their life dates are as follows:

- William Patrick (1841–1936)

- Alice Aseneth Cecelia Smith (1850–1937)

- John Hugh (1872–1956)

- Rose Cecil (1874–1944)

- Mary Ilena (Lee) (1877–1967)

- James (1881–1905)

- Callista (1883–1946)

- Edward (1886–1888)

- Clarence Gerald (1889–1961)

James, Callista and Edward probably had more than one given name each. James died at Bonniebrook, as did Meemie and Callista. Most are buried there; O’Neill’s father is in a military cemetery in California, Edward is buried in Nebraska, and Clarence in Nevada, MO.

Rose O’Neill revealed her talents as a writer and artist at a young age. She won a drawing contest for the Omaha World-Herald when she was thirteen. At age nineteen, O’Neill traveled alone to New York City to sell her first novel. She brought with her a portfolio of sixty illustrations and sketches and showed them to various New York magazine editors and publishers. Editors admired her artwork and gave her commissions for illustrations and commercial posters. O’Neill’s career as a professional artist had begun.

By her early twenties, O’Neill was nationally known for her illustrations in popular magazines such as Ladies Home Journal , Good Housekeeping , and Woman’s Home Companion . She also drew hundreds of cartoons for the humorous magazine Puck . During this period of her life O’Neill had two brief marriages, the first to Gray Latham in 1896 and then to Harry Leon Wilson in 1902. She remained single after 1907.

Bonniebrook

While O’Neill worked as an artist in New York City, her family moved from Nebraska to a homestead in Taney County, Missouri. When she visited her family for the first time in Missouri, O’Neill fell in love with the enchanting Ozark mountains, woods, and streams. She named their charming farmstead “Bonniebrook” and returned to it throughout her working career. Near the end of her life, O’Neill retired there.

Bonniebrook was a rambling, three-story, fourteen-room structure completed around 1910 by Rose O’Neill’s father, brothers, and local craftsmen. It stood in a remote and rustic setting on Bear Creek in Taney County until it was destroyed by fire in 1947. In 1993 a replica house was completed by the Bonniebrook Historical Society, and the homestead acreage is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Bonniebrook and the surrounding Ozark woods became a source of artistic inspiration for O’Neill. At Bonniebrook, surrounded by her loving family, Rose O’Neill first dreamed of and created the cute, good-natured characters that would make her world famous.

O’Neill’s Kewpies made their first appearance as character drawings in a women’s magazine in December 1909. Kewpies were fanciful, elf-like babies with a top-knot head, a wide smile, and sidelong eyes. They were both impish and kind and solved all kinds of problems in humorous ways. O’Neill described them as “a sort of little round fairy whose one idea is to teach people to be merry and kind at the same time.” The Kewpies were immediately popular with both children and adults.

In 1913 O’Neill patented a doll based on the Kewpie character. She oversaw the making of the first Kewpie dolls originally produced in Germany. The dolls were sold all over the world along with a vast array of Kewpie merchandise such as tableware, fabrics, and trinkets.

Female Illustrator and Artist

By 1914 O’Neill was the highest-paid female illustrator in America. Her income allowed her to support her family in Missouri and travel extensively in Europe. There she easily made friends with fellow artists and writers and hosted expensive parties. In this lively environment, O’Neill produced her serious art, much of which she labeled her “Sweet Monster” art. Influenced by European artists and her own Irish-American upbringing, O’Neill merged mythic-like figures with animal traits and pushed them into extreme and unusual poses in her paintings and sculptures.

Her fine art exhibits, in both Paris and New York, revealed a much different side to her artistic personality. O’Neill’s strange, intertwining shapes—twirling amid a whirlwind of decorative elements—created a kind of fantastical art that both enthralled and challenged her admirers.

Writer and Suffragist

In addition to her illustrations in magazines, books, and newspapers, Rose O’Neill also wrote children’s books featuring the Kewpies, as well as novels and poetry . O’Neill explored the creative process and the complex relationship between women and men in her novels and poems. Despite her success as an artist and writer, O’Neill could not vote in public elections because she was a woman. O’Neill worked diligently, along with her sister Callista, to support the suffragist movement. She drew posters and cartoons and marched in protest parades. Her efforts helped women gain the right to vote in 1920.

The Master-Mistress

All in the drowse of life I saw a shape, A lovely monster reared up from the restless rock, More secret and more loud than other beasts. It, seeming two in one, With dreadful beauty doomed, Folded itsellf, in chanting like a flood. I said, “Your name, O Master-mistress?” But it, answering not, Folded itself, in chanting like a flood.

O'Neill’s Legacy

O’Neill worked industriously and financially supported her family and many fellow artists throughout her career. In the 1930s, her fortunes dwindled due to her generosity and the financial stress of a worldwide economic depression. Also, after thirty years of popularity, interest in the Kewpie character started to wane. O’Neill’s artwork—and the Kewpies—were no longer in high demand as realistic photographs replaced fanciful illustrations in magazines and newspapers.

In 1937 O’Neill retreated permanently to Missouri to live at Bonniebrook. There she wrote her memoirs with the help of her friend, the Ozark folklorist Vance Randolph. Her autobiography, published many years after her death, reveals her personal philosophy: “Do good deeds in a funny way. The world needs to laugh or at least smile more than it does.” She died on April 6, 1944, at the age of 69. She was buried at Bonniebrook.

References and Resources

For more information about Rose O’Neill’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Rose O’Neill in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri . The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Brashear, Minnie M. “ Missouri Verse and Verse-Writers .” v. 19, no. 1 (October 1924), pp. 64–68.

- “ Missouri Women in History: Rose O’Neill .” v. 62, no. 4 (July 1968), inside back cover.

- “ A Missourian’s Dolls Amused a Generation of American Children .” v. 48, no. 4 (July 1954), pp. 368–370.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- Garside, Frances L. “How Rose O’Neill Made Good.” Kansas City Star . February 18, 1917. p. 3C. [Reel # 20686]

- Martyn, Marguerite. “Creator of Kewpies – Rose O’Neill: Returns to Her Starting Point in Taney County, Mo.: ‘Is There to Stay.’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch . August 29, 1937. Women’s Sunday Magazine, p. 1, 3H. [Reel # 42537]

- Mecher, Louis. “Rose O’Neill Infused Her Kewpies with Spirit of a Rare Personality.” Kansas City Times . April 7, 1944. pp. 1–2C. [Reel # 24088]

- “Rose O’Neill Infused Her Kewpies with Spirit of a Rare Personality.” Kansas City Times . April 7, 1944. [Reel # 24088]

- “Rose O’Neill Is Dead.” Kansas City Star . April 6, 1944. [Reel # 20686]

- “Rose O’Neill Is Put Away by Bonniebrook’s Green Bank.” Springfield Leader and Press . April 7, 1944. p. 1. [Reel # 49067]

- “Rose O’Neill, Poet-Artist of the Ozarks.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch . June 29, 1913. Sunday Supplement, p. 3. [Reel # 41993]

Books Written and Illustrated by Rose O’Neill

- Garda . Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1929. [I On2ga]

- The Goblin Woman . Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1930. [I On2go]

- The Kewpie Kutouts . New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1914. [I J On2kk In Case]

- The Kewpies and Dotty Darling . New York: George H. Doran Co., 1912. [I J On2kd In Case]

- The Kewpies and the Runaway Baby . Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1928. [I J On2kr In Case]

- The Kewpies, Their Book . New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1913. [I J On2kb In Case]

- The Lady in the White Veil . New York: Harper & Brothers, 1909. [I On2la]

- The Loves of Edwy . Boston: Lothrop Publishing Co., 1904. [I On2lo]

- The Master-Mistress: Poems . New York: A. A. Knopf, 1922. [I On2m]

- Scootles and Kewpie Doll Book . Akron: Saalfield Publishing Co., 1936. [I J On2sc In Case Oversize]

- Scootles in Kewpieville . Akron: Saalfield Publishing Co., 1936. [I J On2s In Case Oversize]

- The Story of Rose O’Neill: An Autobiography . Miriam Formanek-Brunell, ed. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997. [REF F508.1 On2on 1997]

Books Illustrated by Rose O’Neill

- Caeser, Irving. Sing a Song of Safety . New York: I. Caesar, 1937. [784.6 C116]

- Fillmore, Parker Hoysted. The Hickory Limb . New York: John Lane Co., 1910. [813 F485]

- Fillmore, Parker Hoysted. A Little Question of Ladies’ Rights . New York: John Lane Co., 1916. [813.5 F485]

- O’Neil, George. Tomorrow’s House, or The Tiny Angel . New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1930. [I Onlt]

- Quinn, Vernon. The Kewpie Primer . New York: F. A. Stokes Co., 1916. [I J On2kp In Case]

- Wilson, Harry Leon. The Lions of the Lord: A Tale of the Old West . Boston: Lothrop Publishing Co., 1903. [289.3 H693]

- Woman’s Home Companion. Better Babies Bureau. Our Baby’s Book . New York: Woman’s Home Companion, 1914. [I On2o]

Books and Articles about Rose O’Neill

- Armitage, Shelley. Kewpies and Beyond: The World of Rose O’Neill . Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1994. [REF F508.1 On2ar]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography . Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 584-586. [REF F508 D561]

- Currie, Stephen. “Rose Cecil O’Neill and Her Kewpies.” American History . February 2005, pp. 24-26, 70-71. [REF Vertical File]

- Dains, Mary K., ed. Show Me Missouri Women: Selected Biographies . Kirksville, MO: Thomas Jefferson University Press, 1989. v. 1, pp. 131-132. [REF F508 Sh82 v.1]

- McCanse, Ralph Alan. Titans and Kewpies: The Life and Art of Rose O’Neill . New York: Vantage Press, 1968. [REF F508.1 On2m]

- Nevins, Mona, and Bob Gibbons. “Sweet Monsters”: The Serious Art of Rose O’Neill and Her 1921 Paris Exhibit . Branson, MO: Bonniebrook Historical Society, 1993. [REF F508.1 On2sw]

- Ruggles, Rowena Godding. The One Rose: Mother of the Immortal Kewpies . 2nd ed. Albany, CA: privately published, 1972. [REF F508.1 On2r 1972]

- Stepenoff, Bonnie. “Rose Cecil O’Neill.” American National Biography . New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. v. 16, pp. 733-734. [REF 920 Am37 v. 16]

Manuscript Collection

- Mrs. Walter Griffen Scrapbooks (C1402) Newspaper and magazine clippings of pictures and articles of Missouri scenes, the Ozarks, and Hannibal. Volume 1 contains information about O’Neill.

- John G. Neihardt Papers (C3716) Folder 54 contains a letter from Rose O’Neill to the poet Neihardt.

- Rose O’Neill Papers (SP0026) The Rose O’Neill Papers consist of the personal correspondence of Rose O’Neill and her family members and friends.

- Lucile Morris Upton Papers (C3869) The personal and professional papers of a Springfield, Missouri, journalist and writer consist of newspaper clippings, correspondence, research notes, manuscripts, pamphlets, photographs, and scrapbooks. The papers are especially strong in the history of Springfield and the Ozarks region, as well as Ozark folklore. Information on Rose O’Neill can be found in folder 144.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Biographical Database of NAWSA Suffragists 1890-1920 The National American Woman Suffrage Association has created an online database of biographical sketches of women involved in the suffrage movement. The website includes a biography of Rose O’Neill.

- Bonniebrook Historical Society This is the Website for the Bonniebrook Historical Society, a society dedicated to providing information about Rose O’Neill, her life in the Missouri Ozarks, and her artistic career.

- Brandywine River Museum Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, is a museum of regional and American art. Illustrations by Rose O’Neill are included in the Brandywine collection of major American illustrators. The museum mounted an exhibit entitled The Art of Rose O’Neill in 1989. It published a catalog by the same name in which a significant essay by Helen Goodman on O’Neill’s work appears.

- The Ozarkiana Collection The Ozarkiana Collection, gathered by Townsend Godsey, a longtime Ozarks researcher and writer, is housed in Lyons Memorial Library at the College of the Ozarks at Point Lookout, Missouri. This special collection contains various pictures and writings of Rose O’Neill that were donated by her to the college before her death.

- ABOUT KEWPIES

About Rose O'Neill

- Official Store

- Kewpie Licensees

- KEWPIE® x ONCH®

- Kewpie® Events

Biography of Rose O’Neill as written by Susan K. Scott, of Bonniebrook Historical Society, for the National Women’s Hall of Fame induction in 2019 of Rose O’Neill.

Biographical Information

Birthplace and Death

June 25, 1874, Rose Cecil O’Neill was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

O’Neill died in Springfield, Missouri on April 6, 1944 and is interred in the Bonniebrook Homestead Cemetery, Walnut Shade, Missouri along with her family.

Marital Status

While married to Gray Latham, O’Neill signed her art O’Neill Latham. After divorcing Latham and marrying Harry Leon Wilson, she stated that she would never again attach someone else’s name to her art. Hence, O’Neill never used her second husband’s last name in her art. That marriage also ended in divorce. No children were born of either union.

Education/training

At an early age, O’Neill sporadically attended Sacred Heart Academy School in Omaha, Nebraska. Her family was living at the poverty level, so she and her siblings attended with free tuition. O’Neill did not graduate from high school and her last grade attended is unknown. The O’Neill family were poor which led to bullying of Rose and her siblings by neighborhood adults and children.

Born with a true artistic gift, O’Neill was originally self-taught in the fields of art and writing. At the age of 13, she won first place in a children’s art contest sponsored by the Omaha World Herald .

In 1893, O’Neill went to live with the Sisters of St. Regis in New York City where the nuns helped her with additional educational training that included French lessons. O’Neill spent much time in the New York City Library where she studied the illustration purchasing habits of many book and magazine publishers. She would then go prepared with her stack of illustrations and met with the art editors of the major publishing houses.

Professional/work history

O’Neill was encouraged by the publishing companies to only use her last name to disguise her gender. Many of those companies were concerned that if their subscribers knew she was a woman artist, they would cancel their subscriptions. O’Neill was only sixteen years old when her first published illustration appeared in Chicago Graphic in July 1890.

O’Neill is recognized as “America’s First Female Cartoonist” with her cartoon strip “The Old Subscriber Calls,” Truth Magazine , September 19, 1896.

In 1897, O’Neill was hired by Puck Magazine as the first woman cartoonist on its all-male staff and she remained the only woman staffer for six more years. Hundreds of her illustrations for Puck depicted women and minorities in strong leadership and intellectual roles. Her mistake was selling her art and the literary editors of Puck added the “funny gag lines.” Rose later admitted that she had lost control of her art with the men editors deciding what the “funny” comments under her illustrations would be.

O’Neill’s cartoons, illustrations, short stories, and poems were purchased by over fifty national magazine publishing companies starting in the early 1890’s and continuing until the late 1930’s. O’Neill’s illustrations appeared on sixty covers of national magazines.

From 1905-1933, O’Neill’s art was used for product advertising for various companies including Edison Phonograph, Rock Island Railroad, Proctor & Gamble, Colgate Palmolive, and Genesee Pure Food Company.

From 1904-1930, O’Neill wrote and illustrated four novels and eight children’s books that were published from 1910-1936. In 1922, O’Neill‘s one hundred-fifty illustrated poems were published in her book, The Master Mistress .

O’Neill’s illustrations appeared in over forty books along with many short stories, written by other authors, from 1898-1940. Some of those were well-known and requested Rose to be the illustrator.

Rose O’Neill created the Kewpie character that appeared in her illustrated stories published by Good Housekeeping, Ladies Home Journal, Delineator, and Woman’s Home Companion during the years 1909-1928. This character was “a good-will ambassador” spreading love, laughter, and philanthropy.

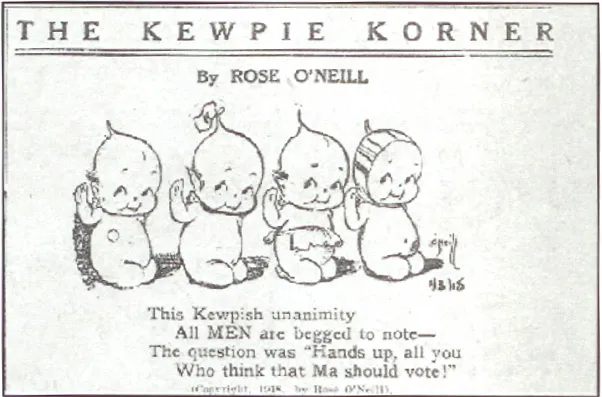

O’Neill Kewpie comics appeared in full page Sunday newspapers across the United States from 1917-1930’s. Her single cell cartoons, Kewpie Korner (1917-1918), appeared in U.S. newspapers. These cartoons dealt with the subjects of suffrage, war bonds, supporting soldiers, and discrimination.

Comic authorities in Nemo 12 (1985) proclaim Rose O’Neill to be “The First Great Female Cartoonist.” Rick Marschall, cartoon critic, discussed O’Neill’s contribution to the world of cartoon art in this issue of Nemo. His comments included, “She was a woman in a man’s world – not only the business world, but in illustration and cartooning. Her work was also a bundle of widely varied styles and themes ranging from cute children’s conceits to steamy romance novels, illustrated by her. But mainly her prominence was due to her overwhelming talent and brilliant artwork.”

Shelley Armitage, Kewpies and Beyond The World of Rose O’Neill (1994), reveals her opinion concerning the impact of O’Neill’s art, “O’Neill’s art centered on the shifting roles of women, ethnic groups, and children, often using a member of one of these groups to undercut the pretentiousness of the polished, urban upper crust, or she treated humorously the in-group exchanges as a kind of private humor, rather than the standard put-down. Her children for example, are often savvy, Dickens-like characters, streetwise and resourceful, to whom the adult world is artificial or absurd-superficial, sentimental, and unrealistic. Class distinctions and implicit value judgments are hence inverted for an audience whose expectations were quite the opposite.”

In 1893, O’Neill’s mother, father, and siblings moved to the remote Missouri Ozarks. Rose visited in 1894 and named the homestead, Bonniebrook. Bonniebrook was the family home. With money from the sale of her art, she built a 14-room mansion at Bonniebrook that was completed in 1909. Over the years, she went back and forth from New York to Bonniebrook.

O’Neill leased two apartments in Washington Square starting in 1914. One was for her where she had a large art studio and the other for her sister, Callista who handled a lot of the business papers for Rose.

In 1921, O’Neill purchased a villa on the Isle of Capri, Italy. O’Neill owned a home in Westport, Connecticut from 1922-1937.

By the year 1937, Rose had lost her other homes and retired full time to Bonniebrook. She always stated, “Bonniebrook is my favorite place on earth. Here I have done my best work.”

Women’s Activism:

As a successful artist, writer, businesswoman, and philanthropist, Rose boldly assisted with the activities of the woman suffrage movements coordinated by the National Woman’s Suffrage Association headquartered in New York City. From 1914-1918, O’Neill was well known as a “suffrage artist” during the suffrage campaigns in the United States. Her art was used for suffrage posters, flyers, and postcards that were circulated throughout the United States. The National Woman Suffrage Association selected women leaders to represent each of the various career fields for a Fourth of July celebration at the City College Stadium. O’Neill carried the “Illustrator” banner to represent women artists in their skit “Woman Suffrage Victory 1917 for New York State.”

O’Neill’s fashion illustrations were first published in Art-in-Dress magazine in the early 1890’s. Years later, the March 1911 Good Housekeeping article featured fashion comments from “The Views of Distinguished Artists” to answer the question, “Are The Fashions Ugly?” O’Neill’s illustrations and article referenced corsets, “When woman runs again on noble, flat feet, and bends like Atalanta stooping for the golden apples, she will be beautiful once more, as of old.”

April 25, 1915, The New York Press article, “Leg Emancipation Women’s New Plea,” announced O’Neill’s participation as a judge on the Polymuriel Prize Fund Committee of New York. The article references her innovative fashion drawing depicting feminine, flowing, silky trousers that were covered with a tunic. O’Neill explained, “It is quite time that a decisive stroke was struck for the freedom of women, not only as regards to the suffrage question, and, of course, I am very keen on that, but on other matters. The first step is to free women from the yoke of modern fashions and modern dress. How can they hope to compete with men when they are boxed up tight in the clothes that are worn today?”

The New York Historical Society Nov 3, 2017-Mar 25, 2018 Hotbed exhibit included some of her participation in the suffrage movement. Her striking suffrage poster, Together for Home and Family, several of her suffrage postcards along with a photo of Rose marching in a suffrage parade and a photo of her in the Washington Square apartment were included in the exhibit.

Women’s International Expositions:

In the 1920’s, O’Neill participated in a series of women’s international business expositions in New York City. O’Neill’s distinctive art, reflecting strong women themes, was used on the covers of several program booklets for these expositions.

Philanthropy

The Actors Fund of America utilized O’Neill’s art on the front cover of their programs for the fundraising events during the years from 1910-1924. O’Neill also joined donors and organizers of the Fund in supporting young actors through financial resources for training and schooling in the performing arts.

O’Neill’s involvement in the “1911 New York Child Welfare Exhibit” comes as no surprise since her art regularly focused on the plight of children in the streets along with those struggling in poverty. Her participation included donations of illustrations for a visual exhibit in the Law and Administration section of this exhibit. The purpose of the exhibit was described, “Let us try to arrange matters so that no child in New York shall miss his rightful chance to grow up through happy, well-balanced childhood into the useful, interesting work of adult life.”

“The Kewpies Health Book” published in 1929 was used by many schools across the U.S. in a national information program about tuberculosis. Large posters from the O’Neill illustrations in this booklet were also distributed by the Atlantic Visiting Nurse and Tuberculosis Assn.

The Artistic Development of the Kewpie Comic Character:

The creation of the Kewpie cartoon character and its symbolic message of good should be studied prior to one dismissing its importance in the art career of O’Neill. How she used the popularity of this world-wide known character, included in her art and stories, to deliver serious messages concerning war, suffrage, discrimination, women’s rights, and the down-trodden should not be considered trivial only because it was later developed into a doll.

Author Shelley Armitage once described Kewpies, “The Kewpies are free-thinking intellectuals who analyze and evaluate the impact of American culture on the rich and poor, native born and immigrant, adult and child. Unrestricted by clothing and other symbols of the culture they criticize, they denounce social conventions responsible for widespread misery.”

The San Francisco Chronicle, November 25, 1917 article promoted the beginning of the Kewpie Korners in the newspaper , “Rose O’Neill is the highest-paid woman artist in the world. This is not so much because of the obvious perfections of her art, as because of the great, clear human note she strikes what time she puts her pen to paper. Just to look at a Kewpie is to smile. To read a Kewpie verse is to play sunshine upon a dark spot. They radiate happiness, do these winsome, mischievous little tads. Rose O’Neill took them, in the first place, right out of her own fine heart and for six years now, a multitude of folks have been the happier because she did it.”

The Kewpies created a worldwide sensation. It is said to be the first such phenomenon that began from magazine stories and verse. Factories in Germany were the first to make an unending list of products that were decorated with O’Neill’s Kewpie art. Those products included dolls, dishes, car hood ornaments, lamps, salt and pepper shakers, figurines, cameras, tea sets, and handkerchiefs.

Honors and Awards Received

A short list of some O’Neill honors, awards, and exclusive art exhibits are as follows:

At thirteen, O’Neill entered a children’s art contest sponsored by the Omaha World Herald . She won first prize in the contest with her mature drawing “Temptation Leading Down into an Abyss.”

O’Neill is believed to be among the first American women to be elected a member of the prestigious Société des Beaux-Arts and thus was invited to exhibit her art in Paris Salons as early as 1906 and 1912.

The 1906 issue of Revue Internationale de Sociologie addressed the importance of O’Neill’s art, “The section for pastels, watercolors and drawings is very bright this year, there’s many notable feminine talents, among which there must be a place apart as Miss Rose Cecil O’Neill outlines a series of sketches of spiritual eloquence, a fun and bold imagination. This young artist, from overseas, owns a decision, and boldness in the pencil that more than one designer may envy.”

In 1911, O’Neill’s art was selected to be exhibited in Rome, Italy and was included in “The Collection of Pictures and Sculpture in the Pavilion of the United States of America” at the Roman Art Exposition.

O’Neill exhibited three works in the 1913 October-November “The Society of Illustrators Fourth Special Exhibition” at the Galleries of the National Arts Club in New York City.

Rose became the first woman elected as a Fellow of the New York Society of Illustrators in 1916. Prior to that date, four women had been named “Associates.”

In 1921, O’Neill displayed one hundred and seven drawings and four sculptures at the Exposition d’Oevres de Rose O’Neill at the Galerie Devembez. This art was not for sale but after insistence from the Luxembourg and the Petit Palais, O’Neill re-drew two pieces of the art and donated them to the museums.

A solo exhibit of over one hundred O’Neill drawings took place at the Wildenstein Galleries in New York City in 1922. This exhibit introduced her serious drawings and “Sweet Monsters” to America. This art was not for sale. Art critic Talbot Hamlin stated, “There has always been a groping around for a synthesis; several American artists have nearly discovered the secret. But never has the perfect synthesis of form as decoration and form as expression been achieved so powerfully and so directly as in the finest work of Rose O’Neill.”

In 1967, the International Rose O’Neill Club was founded to preserve and perpetuate the memory and works of O’Neill, to promote the cultural arts, and to hold an annual celebration in Branson, Missouri. The Club continues to provide scholarships to aid needy talented students in the area of the arts.

1974 The U.S. Post Office honored the 100th anniversary of the birth of O’Neill with a 1974 First Day cover.

In 1975, Bonniebrook Historical Society, Inc. (BHS), a 501(c) (3) non-profit organization, was organized to collect, preserve, and make available for educational and historical purposes artifacts, documents, personal items, and any works or items directly relating to the history and life of Rose O’Neill. BHS maintains the Bonniebrook Homestead property that includes the O’Neill cemetery. The BHS tour home, museum, fine art gallery, gift shop and research library are staffed with volunteers. O’Neill is honored every single day at Bonniebrook!

In 1985, the Society of Illustrators Museum of American Illustration, located in New York, hosted the exposition America’s Great Women Illustrators 1850-1950 which included six pieces of O’Neill art.

The Brandywine River Museum, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania held an exhibit honoring O’Neill’s art in 1989. The Art of Rose O’Neill by Helen Goodman was published as a result of this exhibit.

In 1997, O’Neill was included in the U.S. Post Office in the “Classic American Dolls” set of stamps. The Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame in New York City inducted O’Neill in 1999. O’Neill was honored by the United States Post Office American Illustrators Series of 2001 stamps.

The Westport Connecticut Historical Society “Yesterday’s Toyland” exhibit October 9, 2005-January 15, 2006 included O’Neill information, “Rose O’Neill, a prominent member of our town’s early art colony, and her 1909 brainchild-the Kewpie Doll – are featured in Yesterday’s Toyland. The popularity of her Kewpie was international - one of the greatest successes in the history of doll making.”

The National Women’s History Project honored O’Neill during their 2008 theme, Women’s Art: Women’s Vision .

The Missouri Women’s Council inducted O’Neill into their “Outstanding Women of Missouri Hall of Fame” in June 2011.

In 2012, Drury University, Springfield, Missouri, restored the home where O’Neill died and now utilizes the “Rose O’Neill House” as the office of their Women’s Studies Program and Art Department special exhibits that highlight O’Neill’s accomplishments.

April 14-August 5, 2018, the Springfield Art Museum, Springfield, Missouri hosted the exhibit, Frolic of the Mind: The Illustrious Life of Rose O’Neill . The exhibit traced O’Neill’s work in all media and featured 150 works from public and private collections. The exhibit announcement from the Springfield Art Museum provided an important introduction to the works of O’Neill, “This exhibit takes as it’s underlying theme the unification of all of O’Neill’s creative pursuits and examines how they each were related, one to the other, from her hundreds of illustrations for the major periodicals of the day to her more secretive “Sweet Monster” drawings. Each of these are rooted in the singular mind of Rose O’Neill- a woman who created a life on her own terms with sheer will, determination and creative talent. The ability to pursue all of her interests, in spite of the strict social rules placed upon women at the turn of the century, is perhaps the most fascinating story of them all. Rose O’Neill, the twice-divorced suffragist lived a life unbound, an iconoclast, and a rebel among reformers – yet she was beloved by nearly all who knew her.”

Contact Us Licensing Inquiries Terms and Conditions Privacy Policy Cookie Policy Follow us Winners List

©2023 Kewpie Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

Women Who Shaped History

A Smithsonian magazine special report

The Prolific Illustrator Behind Kewpies Used Her Cartoons for Women’s Rights

Rose O’Neill started a fad and became a leader of a movement

Adina Solomon

:focal(536x587:537x588)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/4a/364a861f-9f2f-43d5-810b-006b2b3ba2d0/kewpies-woman-suffrage-voting-kewpie-korner2.jpg)

In 1914, a crowd gathered at the fairgrounds in Nashville, Tennessee. After enduring a wait in the November chill, people looked to the sky as a plane piloted by famed aviator Katherine Stinson buzzed overhead until finally, it dropped its cargo: parachuting cupid-like dolls gently floating toward the ground, wearing sashes advocating for women’s right to vote. These figurines, known as Kewpie dolls, were the brainchildren of Rose O’Neill, an illustrator who revolutionized the intertwining of marketing and political activism.

O’Neill was born in 1874 and grew up in poverty in Omaha, Nebraska. By the time she turned 8 years old, she was drawing, says Susan Scott, president of the board at the Bonniebrook Historical Society, a non-profit dedicated to educating the public about O’Neill’s life. In 1893, the O’Neills homesteaded near Branson, Missouri, at a site they named Bonniebrook.

She brought her self-taught drawing skills to New York City at 19, staying in a convent so she wasn’t all by herself in the big city, and meeting editors throughout the day at the city’s publishing offices. Much to the likely shock of the mostly men editors, O’Neill took meetings with several nuns in tow.

O’Neill eventually joined the esteemed humor magazine Puck , where she was the only woman on staff and where she drew illustrations supporting gender and racial equality. She earned a reputation as a sought-after illustrator known for fast work, drawing for magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal , Good Housekeeping and Cosmopolitan , which at the time was a literary publication.

“O’Neill didn’t have any one style or method,” Scott says. “She was so versatile. That’s why the publishers loved her. It could be real cutesy and look real cute, or it could be very strong and bold and look like something a man artist would’ve drawn at the time, more masculine art.”

She often worked from Bonniebrook as the New York offices didn’t have bathrooms for women, says Linda Brewster, who has written two books on O’Neill with a third on the way. While in Bonniebrook in 1909, O’Neill would illustrate her most lasting creation: Kewpies. Adapted from the classic “cupids,” O’Neill’s smirking, cherub-like characters with rosy cheeks came about when a Ladies’ Home Journal editor asked her to create “a series of little creatures,” as O’Neill recounted in her autobiography. The editor had seen O’Neill’s drawings of cupids elsewhere and wanted something similar in the magazine.

In her autobiography, O’Neill wrote that the Kewpie is “a benevolent elf who did good deeds in a funny way.” The initial iterations of the Kewpies came with accompanying verses invented by O’Neill. “I thought about the Kewpies so much that I had a dream about them where they were all doing acrobatic pranks on the coverlet of my bed,” she wrote.

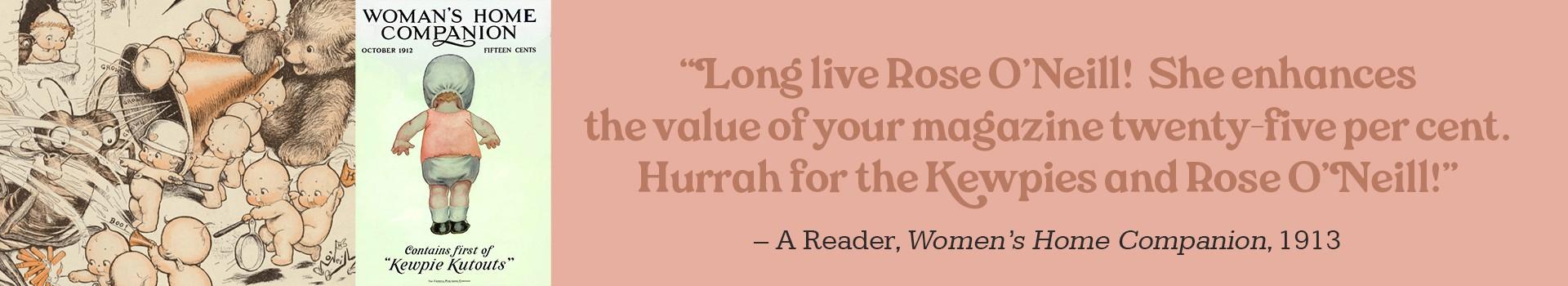

Those Kewpies leapt from her dreams onto the pages of Ladies’ Home Journal ’s Christmas issue that year. Adults and children alike became enamored with the drawings. A reader, echoing a popular sentiment, wrote to Woman’s Home Companion in 1913: “Long live Rose O’Neill! She enhances the value of your magazine twenty-five per cent. Hurrah for the Kewpies and Rose O’Neill!”

Magazines clamored for a chance to publish Kewpie cartoons along with O’Neill’s stories and verses about them. Soon they emblazoned commercial products too, everything from Jell-O ads to candy to clocks. To this day, people use Kewpie Mayonnaise, a prized mayo from Japan.

Several toy factories approached O’Neill about creating a Kewpie doll, and, in 1912, toy distributor George Borgfeldt & Company started producing the dolls, with royalties going to O’Neill, made of bisque porcelain. O’Neill and her sister traveled to Germany to sculpt a few sizes of the toy and show the artists how to paint them. To her surprise, Kewpie dolls became popular – a fad no one could escape – not only in the U.S. but in Australia, Japan and places all over the world.

According to Scott, O’Neill held the trademark and copyrights to Kewpies in the U.S. and leveraged them to make an estimated $1.4 million, the equivalent to more than $35 million today.

Apart from being a significant moneymaker, the Kewpies, as seen in the magazines, were cute characters with a message, often mocking elitist middle-class reformers, supporting racial equality and advocating for the poor. O’Neill also used the cartoons to champion a cause she felt passionately about: the fight for women’s right to vote.

“What was neat was that she was able to use this popular character for suffrage, and it got people’s attention,” Scott says. “Some people would go, ‘How could she use the Kewpie for suffrage? Why is she getting them involved in politics?’ And then other people just really didn’t even notice. They thought, ‘Oh, isn’t that cute? Votes for women. Oh, OK.’”

O’Neill was generous with her fortune. Brewster says she once paid for everyone in Branson to be immunized against smallpox, and she frequently gave money to artists in search of success and fans who wrote her letters.

When she wasn’t spending time at Bonniebrook, O’Neill rented a Greenwich Village apartment, becoming friends with many of New York City’s writers, poets and musicians. Being a part of this counterculture scene allowed O’Neill to participate and march in the city’s active suffrage movement. Suffragists often held banners at marches identifying their professions, so O’Neill hoisted the illustrators’ banner at marches for all to see, says Laura Prieto, professor of history and women’s and gender studies at Simmons College in Boston.

According to Prieto, it was the more-radical suffragists who added public marches to the movement. “If you think about an era in which women were supposed to be domestic creatures in the home, marching through the streets of the city is a pretty radical act,” she adds.

Kewpies played a role in these activities. There was the 1914 rally in Nashville where Kewpie dolls wearing suffrage sashes rained upon the crowd. The next year, a march in New York featured a “children’s van” decorated by O’Neill with Kewpies. Scott has found accounts of a billboard in New York that featured the Kewpies marching for women’s right to vote.

Besides lending a celebrity to the cause, Kewpies helped the suffrage movement combat the stereotype of a feminist as old, ugly and anti-men, Prieto says.

“It was a way to sell a different image of suffrage and who should support it, who already supported it, and that it was something compatible with motherhood and nurturing,” she says.

O’Neill illustrated souvenir programs distributed at marches and postcards and posters, some involving Kewpies, for the National American Woman Suffrage Association. She also contributed a Kewpie to a suffrage exhibit at a New York art gallery.

“That was her putting her creation at the service of the suffrage movement,” Prieto says.

After women won the franchise, O’Neill continued advocating for feminist causes. She showcased her art at the 1925 Exposition of Women’s Arts and Industries, designing the program cover with an illustration titled “Progress.”

Kewpies were a fad with surprising staying power, but they were still a fad. Kewpie knockoffs became more common, and people eventually lost interest in the dolls. O’Neill went on to have exhibitions of fine art illustrations – considered more serious art than Kewpies – in Paris and New York. At one point, she studied sculpture under Auguste Rodin in Paris.

By the end of her life, O’Neill’s famous generosity led her to give away most of her fortune to not only her family but artists, friends and admirers who asked for money. She died penniless in 1944.

But her influence and Kewpie dolls remain. As the 1913 letter written by the reader of Woman's Home Companion stated:

“They are equal to the best sermons, for producing a right condition of health, and good will and your readers object to them, they need a physician’s advice; yet I think there is no medicine better for them than a look at the Kewpies.”

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

- Library of Congress

- Research Guides

- Newspapers & Current Periodicals

Rose O'Neill, The Kewpie Lady: Topics in Chronicling America

Introduction.

- Search Strategies & Selected Articles

Newspapers & Current Periodicals : Ask a Librarian

Have a question? Need assistance? Use our online form to ask a librarian for help.

Chat with a librarian , Monday through Friday, 12-2 pm Eastern Time (except Federal Holidays).

About Chronicling America

Chronicling America is a searchable digital collection of historic newspaper pages through 1963 sponsored jointly by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Library of Congress.

Read more about it!

Follow @ChronAmLOC External and subscribe to email alerts and RSS feeds.

Also, see the Directory of U.S. Newspapers in American Libraries , a searchable index to newspapers published in the United States since 1690, which helps researchers identify what titles exist for a specific place and time, and how to access them.

Rose O'Neill is an iconoclast in every sense of the word. A self-taught bohemian artist, who ascends through a male-dominated field, becoming a top illustrator and the first to build a merchandising empire from her work with her invention of the Kewpie doll. Read more about it!

The information in this guide focuses on primary source materials found in the digitized historic newspapers from the digital collection Chronicling America .

The timeline below highlights important dates related to this topic and a section of this guide provides some suggested search strategies for further research in the collection.

| 1896 | Publishes "The Old Subscriber Calls," in magazine, the first comic strip by a woman. Marries Virginia aristocrat Gray Latham. |

|---|---|

| 1897 | Becomes the only woman on staff at the leading humor magazine . |

| 1901 | Divorces Gray Latham. |

| 1902 | Stops signing her work as a man "O’Neill Latham." Marries Harry Leon Wilson, a writer and editor at . |

| 1904 | Publishes her first semi-autobiographical novel . |

| 1908 | Jell-O becomes her client. |

| 1909 | First Kewpie comic strip debuts in . |

| 1910 | Publishes her first children’s book and Dotty Darling. |

| 1912 | Exhibits artwork at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Paper dolls called "Kewpie Kutouts" begin selling. |

| 1913 | Obtains patent for the Kewpie doll. |

| 1914 | Tells the Press how Kewpies came to her in a dream. Is one the highest paid female illustrators in New York. |

| 1921 | Holds solo exhibit at the Galerie Devambez in Paris. |

| 1922 | Exhibits "Monster" series at the Wildenstein Gallery in New York. |

| 1922 - 1941 | Relocates to her villa "Castle Carabas" in Connecticut, which becomes a sought after artist salon. |

| 1941 | Retreats to a family home in the Ozarks to write memoirs. |

| 1944 | O'Neill dies. |

- Next: Search Strategies & Selected Articles >>

- Last Updated: Dec 28, 2023 10:35 AM

- URL: https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-rose-oneill

- Virtual Exhibitions

- The Civil War

- U.S. Census

When Rose O’Neill’s illustrations appeared in True Magazine on September 19, 1896, she made history by becoming the first female cartoonist to publish a comic strip in America. A self-taught artist, O’Neill (1874-1944) had spent her childhood studying artists and submitting her work to various periodicals around the country. She set out for New York City at the age of nineteen with the intention of becoming a writer. Although she would publish numerous works throughout her career, she quickly impressed publishers with her drawings and was able to start a career as an illustrator.

Paul Thompson, photographer. Rose O’Neill, 1914. Rose O’Neill Collection, PR-369, New-York Historical Society.

Her illustrations appeared in a number of notable periodicals including Harper’s, Life, Cosmopolitan, and a number of ladies’ home journals. Her success led to a full-time position with Puck , the humor magazine known for its political satire and anecdotes. While talented in various forms of art and continuing to freelance, it was the creation of one particular cartoon character that launched O’Neill into fame: the Kewpie Baby.

Woman’s Home Companion (July 1913, p. 27). Object Number: 2018.51.4, New-York Historical Society.

Woman’s Home Companion (December 1913, p. 11). Object Number: 2018.51.5, New-York Historical Society.

Woman’s Home Companion (May 1913). Object Number: 2018.51.3, New-York Historical Society.

The Kewpies made their first appearance in the December 1909 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal and became an instant sensation amongst readers of all ages. While their style was seen in some of O’Neill’s earlier characters, the creation of “Kewpieville” allowed her to write comics that focused on moral values and kindness. The comics were continuously published in Ladies’ Home Journal, Woman’s Home Companion, and Good Housekeeping well into the 1930s. The Kewpie Doll was soon created in 1913, resulting in a wave of toys, advertisements, and household goods portraying the characters. The Kewpies also became an unofficial mascot for the Woman’s Suffrage Movement, thanks to O’Neill’s involvement. Kewpie posters made an appearance with messages supporting the Women’s Right to Vote while several comics featured feminist-themed plots.

One of several posters created during the Woman’s Suffrage Movement that featured the Kewpie babies. Rose O’Neill Collection, PR-369, New-York Historical Society.

O’Neill made $1.4 million from her Kewpie creations, making her the highest-paid and wealthiest cartoonist of her time. All the while she continued to produce works of art that were much more “serious” in nature. Her success as an artist, writer, and cartoonist allowed her to develop a very lavish lifestyle, placing her in the center of the New York art world, but O’Neill eventually faced financial difficulties during the Great Depression. She died from complications of a stroke in 1944. Production of the Kewpie dolls continued through the 20th century. They remain a familiar part of popular culture all over the world.

“Ramming them back into their desks” (undated). Rose O’Neill Collection, PR-369, New-York Historical Society.

Untitled drawing, 1900. Rose O’Neill Collection, PR-369, New-York Historical Society.

Untitled portrait of a woman (undated). Rose O’Neill Collection, PR-369, New-York Historical Society.

Man gazing at a portrait of a woman (undated). Rose O’Neill Collection, PR-369, New-York Historical Society.

[For more, see the Guide to the Rose O’Neill Collection, 1900-1953 (PR 369) .]

This post is by Erin Weinman, Manuscript Reference Librarian.

Keep Reading

Touring New York’s Past: The Sketchbooks of Jane Bannerman

“Home Very Clean and Deserving”: Working-Class Families, Visiting Nurses, and Charitable Aid at the Mott Street School, Part Two

“Home Very Clean and Deserving”: Working-Class Families, Visiting Nurses, and Charitable Aid at the Mott Street School, Part One

The New America: LIFE Magazine's Pitch to a Post-War United States

Champion history.

Sign Up for Our Newsletter

Anthony Meucci. Pierre Toussaint (ca. 1781-1853). ca. 1825. Gift of Miss Georgina Schuyler.

Rose O'Neill

The artistic talents of illustrator, inventor, and suffragist Rose Cecil O’Neill sparked a worldwide craze at the start of the 20th century when she turned one of her best-loved hand-drawn characters into a three-dimensional toy. This toy is none other than the instantly recognizable Kewpie doll. The doll and merchandise bearing its likeness remain collectibles to this day.

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania on June 25, 1874, O’Neill was one of six children born to William and Asenath O’Neill, who moved the family to Battle Creek, Nebraska in 1876. Rose loved to draw as a child, and she got an early professional start when she entered and won an art contest sponsored by the Omaha World Herald at 14 years old. She was invited almost immediately to begin illustrating magazine and newspaper articles. Throughout her teenage years, she worked professionally, illustrating “Arabian Nights” for a magazine called The Great Divide, and she began illustrating a novel she wrote herself, “Callista,” which was the name of one of her siblings.

In 1893, she traveled to New York to see the World’s Fair, where she got her first glimpse of modern art. She thought she might be ready to embark on a career as a novelist, but others encouraged her to continue her education. So, she entered the Convent of the Sisters of St. Regis in New York City. For three years, she refined her drawing technique there and picked up a number of high-profile clients, including Harper’s Weekly, Bazaar, Truth, and Collier’s Weekly.

Meanwhile, her parents and siblings moved once again to a country home in the Ozarks region of Missouri. With her earnings, Rose was able to help build a larger home for the family, which became the O’Neills’ beloved Bonnie Brook homestead.

Rose O’Neill continued working in New York and building on her client base. Over the years, her drawings appeared in the most popular magazines of the era, including Good Housekeeping, Ladies Home Journal, Life, Puck, and many others. She married Gray Lathan in 1896 (whom she divorced in 1901) and began using the signature O’Neill Lathan on her works. At the time, the field was dominated by men, and this was somewhat of a help to her career. She also illustrated a variety of books, written by such authors as Parker Fillmore and Harry Leon Wilson, the literary editor of Puck, to whom she was married from 1902 to 1908.

According to O’Neill, the cherubic-looking characters upon which the Kewpie doll was based came to her in a dream. She began to include these chubby, child-like “elves” in the backgrounds of many of her drawings. When the Ladies Home Journal editor asked her to make a series of illustrations of just these creatures alone, she did so for the publication, which planned to write verses to accompany them so they would have their very own story. Thus the “Kewpies,” which performed good deeds for regular people, took on a life of their own.

The characters and their stories appeared in Woman’s Home Companion and Good Housekeeping, as well as in cartoons and books and later as paper dolls. They became an instant hit among children and adults alike. O’Neill’s book “The Kewpies, Their Book” was released in 1910.

Inevitably, children soon expressed their desires to have an actual Kewpie to hold and play with. O’Neill moved to Europe from 1911 to 1914, and while attending art school in Paris, she began working on plans to mold the Kewpie into a doll. This was a challenge for her with her limited experience in sculpture, but with the help of fellow students and others, she managed to create a statuette that served as a mold. A German factory agreed to manufacture the dolls out of bisque. The dolls hit the international marketplace with incredible success in 1912. O’Neill obtained a patent for the doll in 1913.

The Kewpies were later manufactured in Belgium, France, and the United States after the outbreak of World War II. Meanwhile, merchandising for the dolls exploded, and O’Neill published additional Kewpie books while others created Kewpie dishes, calendars, and other household items. O’Neill is said to have earned at least $1.5 million from the Kewpie franchise, which is equivalent to at least $15 million today. O’Neill lived lavishly with her fortune, purchasing homes in Connecticut, the Isle of Capris, and Greenwich Village, New York. She also continued to illustrate and write novels. Her first novel, “The Loves of Edwy” was published in 1904 when she was just 19 years old. She wrote “Lady in the White Vail” in 1909, a book of poetry, “Master Mistress,” in 1922, “Garda” in 1929, and “The Goblin Woman” in 1930.

She also continued to visit Europe regularly and held her own artwork exhibition in Paris in 1921 at the Galerie Devambez. Stateside, she began to hold salons at her Greenwich Village apartment and became a vocal supporter of women’s right to vote. In addition, she created other characters that became toys, including the Scootles doll in 1925 and the Ho Ho doll in 1940.

She returned to Bonnie Brook in 1937 and lived out the remainder of her years there. O’Neill died on April 6, 1944, shortly after completing her memoirs.

Don't Miss Our Next Newsletter!

101 Rogers Street, Suite 3C, Cambridge, MA 02142 [email protected] » 617-253-3352

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- The Story of Rose O'Neill: An Autobiography

In this Book

- Edited by Miriam Forman-Brunell

- Published by: University of Missouri Press

- View Citation

To most of us, Rose O'Neill is best known as the creator of the Kewpie doll, perhaps the most widely known character in American culture until Mickey Mouse. Prior to O'Neill's success as a doll designer, however, she already had earned a reputation as one of the best-known female commercial illustrators. Her numerous illustrations appeared in America's leading periodicals, including Life, Harper's Bazaar, and Cosmopolitan. While highly successful in the commercial world, Rose O'Neill was also known among intellectuals and artists for her contributions to the fine arts and humanities. In the early 1920s, her more serious works of art were exhibited in galleries in Paris and New York City. In addition, she published a book of poetry and four novels.

Yet, who was Rose Cecil O'Neill? Over the course of the twentieth century, Rose O'Neill has captured the attention of journalists, collectors, fans, and scholars who have disagreed over whether she was a sentimentalist or a cultural critic. Although biographers of Rose O'Neill have drawn heavily on portions of her previously unpublished autobiography, O'Neill's own voice--richly revealed in her well-written manuscript--has remained largely unheard until now.

In these memoirs, O'Neill reveals herself as a woman who preferred art, activism, and adventure to motherhood and marriage. Featuring photographs from the O'Neill family collection, The Story of Rose O'Neill fully reveals the ways in which she pushed at the boundaries of her generation's definitions of gender in an effort to create new liberating forms.

Table of Contents

- Title, Copyright, Dedication

- pp. vii-viii

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Editor's Note

- The Story of Rose O'Neill

- Of Autobiography

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- pp. 113-141

- Chapter Six

- pp. 142-150

- pp. 151-154

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

The Magic of Rose O’Neill at the William H. Hannon Library

This exhibition was on display in fall 2018. This post has been retained for historical purposes. If you are interested in the materials described, please reach out to the Archives and Special Collections Desk.

This post was written by Nina Keen, curator of our Fall 2018 exhibition. Keen is a graduate student in the Department of English at Loyola Marymount University. Read her previous post on this exhibition, Curator Nina Keen on “Sincere and Emotional: Stories of Connection.”

When I was younger, I believed I could fly. Or rather, knew that I could. Each afternoon, standing in the grass of my backyard and gripping my cat-shaped umbrella, I waited and waited to float into the sky. Every day that I remained earthbound, did not prove I couldn’t fly. It just meant it was not the right time yet.

In researching the life and works of Rose O’Neill , I have been brought back to this childlike mindset – where magic is a part of life. Similar to me, O’Neill was fascinated with an aspect of flight herself – wings. As the artist describes in her autobiography, whenever she made a spelling error in a journal entry, O’Neill covered it with detailed and fanciful drawings of wings (68). O’Neill’s attraction to wings was congruent with the rest of her art and fairytale-like biography. Learning about the artist’s life made mine a bit more magical while working as an intern in Archives and Special Collections at the William H. Hannon Library.

Early on into my internship, my supervisor and head of special collections, Cynthia Becht, informed me that the university’s Werner von Boltenstern Collection houses postcards of Rose O’Neill’s famous character, Kewpie. I’d seen Kewpie before on blogging websites like Pinterest, and leapt at the opportunity to search for the popular figure that has been replicated so often. Cynthia further informed me that an original Kewpie postcard was probably within the holiday postcard collection. This intimidated me a bit because our holiday postcard boxes contain hundreds, if not thousands, of postcards. Nevertheless, I set off to discover the authentic Kewpie!

Before I continue, I will define Kewpie (rhymes with Snoopy) for readers who are not familiar with the figure. Kewpie, a caricatured version of Cupid, was initially composed by O’Neill as a corner illustration for love stories in Ladies Home Journal . According to the book, Kewpies and Beyond: The World of Rose O’Neill by Shelley Armitage, the journal’s editor, Edward Bok, asked O’Neill to draw Kewpies as individual characters with individual storylines in comic form after he realized the Kewpies would probably be popular with the public (42). It turned out that Bok was correct, as Kewpie acquired international popularity and accrued quite a fortune for his creator.

O’Neill, in her autobiography, The Story of Rose O’Neill: An Autobiography by Rose O’Neill , wrote that Kewpie was inspired by her experience caring for her beloved younger siblings (135). Though O’Neill has never confirmed this, I have to wonder if the angelic baby character might also have been inspired by the death of the artist’s younger brother, Edward. In her autobiography, she recalls cuddling with the baby’s body after he died and says that she felt “a sweet and curious sensation” at finding a thimble that her sister, Callista, left on Edward’s chest. Apparently, both sisters thought their little brother was beautiful even in death. Though O’Neill admits that this might seem shocking to the average person, her family, she concedes, was “outlandish” (47). Years later, O’Neill claims to have dreamt of Kewpie dancing around her bed, a sweet-looking baby that was “oddly cool” to the touch (O’Neill, 95).

I do not wish to go on at length about O’Neill’s life, as that may take away from the story of Kewpie in the library’s exhibition. But, I will mention a few things – as O’Neill’s life was quite fascinating and broke many standards of conventionality at the time and even of today. Born in 1874, much of O’Neill’s childhood was spent in Bonniebrook, Missouri in a rural home her father built and furnished with antique furniture and classic literature (O’Neill 64). It was there where she grew to have a great appreciation of strong women, exemplified through her mother who was nicknamed Meemie by her children. Rose O’Neill recalls witnessing Meemie hack the way out of the snowfall from a blizzard and save the children from being trapped in the house (O’Neill 20). O’Neill, after being raised among the arts, went on to become a successful female artist – rare at the time – and was the first female illustrator for Puck Magazine (Armitage 30). O’Neill, it might come as no surprise, was very much invested in women’s right to vote and marched and spoke at several suffrage marches (Armitage 46). The Kewpie postcard on display in my exhibition, “Sincere and Emotional: Stories of Connection”, shows Kewpie fighting for women’s suffrage. This postcard was purchased because of my interest in Kewpie and the history of feminism, and is now a part of the William H. Hannon Library’s postcard collection.

While I was discovering these intriguing facts about O’Neill’s life, I set off to find Kewpie. I worried that I would not be able to locate the intriguing character because my eyesight would become bleary after sifting through so many cards. The first day of my search, I ordered in all of the Valentine postcards. I was very optimistic that if a Cupid were anywhere, it would be here. As it turned out, there were many Cupids but not my Kewpie. That night, I dreamt about searching through the postcard boxes and coming up with nothing.