An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Personality development in the context of individual traits and parenting dynamics

Associated data.

Our conceptualization of adult personality and childhood temperament can be closely aligned in that they both reflect endogenous, likely constitutional dispositions. Empirical studies of temperament have focused on measuring systematic differences in emotional reactions, motor responses, and physiological states that we believe may contribute to the underlying biological components of personality. Although this work has provided some insight into the early origins of personality, we still lack a cohesive developmental account of how personality profiles emerge from infancy into adulthood. We believe the moderating impact of context could shed some light on this complex trajectory. We begin this article reviewing how researchers conceptualize personality today, particularly traits that emerge from the Five Factor Theory (FFT) of personality. From the temperament literature, we review variation in temperamental reactivity and regulation as potential underlying forces of personality development. Finally, we integrate parenting as a developmental context, reviewing empirical findings that highlight its important role in moderating continuity and change from temperament to personality traits.

At the core of personality psychology is a focus on variability in human behaviors and attitudes that are stable across context and can arise from within the individual. The belief that people are ultimately individuals who bring unique perspective and contributions to their own development began to flourish in the Western world in the 19th century. This new focus on the individual propelled initiatives within philosophy and psychology to focus on dimensions that differentiate us from one another ( Barenbaum & Winter, 2008 ). Over time, this acknowledgement of individual differences permeated other areas of psychology – raising the notion that variation in individual traits can be systematic and predictive, and not simply random noise to be filtered out. Since personality can influence a host of constructs of interest – motivation, achievement, social behavior, decision-making – attempts to examine individual differences in this domain are evident across the field.

Early on, much of the emerging personality research was mired in a debate centered on quantifying what portion of personality was trait-based in contrast to experience-shaped. However, the current review will not fully wade into this debate—which ironically often pointed to broad theories of development, while not necessarily taking on a developmental approach ( Barenbaum & Winter, 2008 ). Rather, we will focus on how transactions between endogenous and contextual factors shape the personality development. Particularly, we want to highlight early emerging forces, such as temperament, that shape the emergence of personality traits within the context of the parenting environment. In doing so, we review how researchers conceptualize personality today, how temperamental reactivity and regulation may be underlying forces of personality development, and the role of the parenting context in moderating continuity and change from temperament to personality traits. Our understanding of these complex, bi-directional, interactions are outlined and illustrated in a simplified conceptual model (Section 3) that guides our interpretation of the currently available literature.

1. Current conceptualization of personality

The Five Factor Model (FFM) of personality has guided research and theory building for almost three decades ( John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008 ). FFM, also known as the Big Five model, contends that the construct of personality includes Basic Tendencies or traits that are biologically-based, as well as Characteristic Adaptations that result from dynamic interactions between Basic Tendencies and experience. The combination of Basic Tendencies and Characteristic Adaptations , give rise to our observed personality phenotypes and directly impact the individual’s self-concept and objective biography (for a review, see McCrae & Costa, 2008 ). The theory postulates that there are five basic tendencies of personality: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Openness , and Conscientiousness . Briefly explained, Neuroticism reflects emotional instability, and a tendency to display behaviors related to negative emotionality, such as anxiety, tension, and sadness. Extraversion refers to a high desire to approach and engage with the social and material world, and it includes traits of sociability, positive emotionality, and assertiveness. Agreeableness reflects a prosocial orientation and amiability that includes behaviors of altruism and trust, whereas the Openness factor includes dimensions of originality, perceptiveness, and intellect with which individuals experience life. Finally, Conscientiousness refers to a tendency to control impulses in compliance with social order, including task-oriented behaviors such as planning, organizing, as well as following norms or rules ( John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008 ).

In some ways, this conceptualization of personality has been closely aligned with our typical conceptualization of childhood temperament. For example, personality traits have been defined as “endogenous dispositions that follow intrinsic paths of development essentially independent of environmental influences” ( McCrae et al., 2000 , p. 173). The term “endogenous” suggests that these traits are biologically-based and early occurring, much like temperament. In fact, McCrae and colleagues (2000) argued that based on behavioral genetic and heritability studies of personality, we can conclude that personality traits have a large genetic component and that childhood shared environment (e.g., adoptive parents and siblings) has little to no effect on adult personality. Furthermore, they also present cross-cultural analyses of the maturation of personality traits from age 14 to age 50, supporting general declines in Neuroticism and Extraversion , and increases in Conscientiousness with age across five countries. Although these results lend support to the biological and universal aspects of personality traits, we should be careful in making strong inferences. Personality traits are usually assessed at an age when they may have reached a high degree of stability. Thus, these studies may 1) miss potential ways in which context can interact with early expressions of these traits (i.e., temperament) to shape continuity, and 2) miss individual variation or change that cannot be captured at group-level analyses ( Halverson & Deal, 2001 ).

Temperament research typically focuses on the early developmental period, measuring individual differences in behavior and physiology that are expressed in infancy and may lay the foundation for later personality. Indeed, temperament-linked differences are evident as early as four months of age ( Fox, Henderson, Rubin, Calkins & Schmidt, 2001 ; Kagan, 2012 ). By measuring systematic differences in emotional reactions, motor responses, and physiological states (e.g., heart rate variability), we can identify a number of temperament dimensions or temperamental styles that we believe may contribute to the underlying biological components of personality ( Rothbart & Bates, 2012 ). For example, an infant who displays increased limb movement when presented with a toy is rated as highly reactive ( Kagan, 2012 ). If this reactivity is accompanied by smiles and pleasant vocalization, then the infant id also rated as high in positive affect. This pattern of high positive reactivity is linked to the personality trait of Extraversion ( Caspi & Shiner, 2006 ; Slobodskaya & Kozlova, 2016 ), suggesting that this tendency for high approach and engagement of novelty is manifested early in infancy. However, links between temperament and personality traits are rarely strong, suggesting that these biological traits may not follow a path completely independent of environmental influences ( Shiner & Caspi, 2012 ). For example, studies suggest that temperament is influenced by prenatal experiences ( Huizink, 2012 ), and that after birth, early context may continue to influence change and continuity of infant temperament ( van Ijzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2012 ). Furthermore, recent findings from epigenetic research has provided the mechanisms by which experience can robustly influence temperamental traits, such as reactivity and regulation ( Roth, 2012 ).

While previous work in infant temperament has provided some insight into the early origins of personality traits, we still lack a rich or cohesive developmental account of how different adult personality profiles emerge (or evolve) from infancy to adulthood. Despite attempts to link temperament dimensions to adult personality profiles, bridging the gap between early individual differences and adult personality traits has proved to be an intricate endeavor. We believe the moderating impact of context could shed some light on the complex trajectory from infant temperament to adult personality. First, however, we more carefully review our current understanding of temperament and the link to personality.

2. Temperament-linked individual differences and personality

Rothbart and Derryberry (1981) defined temperament as individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation that are constitutional or biologically based. Reactivity, or the arousability of emotion, motor, and physiological systems, is evident in behavioral responses to novel stimuli such as increased vocalization, motoric movement, and affective expression. Furthermore, temperamental reactivity can be positive or negative, depending on the affective valence accompanying the infant’s response. Individual differences at these two emotional extremes are characterized as exuberant and fearful temperaments, respectively. Exuberant infants explore novel spaces and toys and are more likely to respond to a stranger or new social interaction with positive affect ( Fox et al., 2001 ). When in the same situation, fearful infants are more likely to cry, kick, or cling to their mothers, and may also show extreme hypervigilance and negative affect compared to non-fearful children ( Kagan, 2012 ). Temperamental regulation functions to modulate reactivity, such that the behavioral expression of high reactivity may be constrained if effective regulation is also present, or exacerbated if regulation abilities are low.

2.1. Temperamental reactivity

Negative reactivity is associated with a low threshold of arousal in limbic structures, particularly the amygdala and the broader threat response system ( Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1987 ). Greater arousal results in heightened sensitivity to context, such that infants with lower thresholds are more sensitive to novel stimuli and thus more likely to show negative responses characterized by fear, even when presented with ostensibly “neutral” stimuli ( White, Lamm, Helfinstein, & Fox, 2012 ). Such negative reactivity is evident in the later emerging temperament profile of Behavioral Inhibition (BI). BI toddlers show longer latencies to interact or approach, respond with negative affect, and remain in close proximity to their mother when presented with a novel toy or in the presence of a stranger, reflecting a highly vigilant response. Furthermore, these behavioral expressions have been associated with physiological differences also originating in the limbic system, such as higher and more stable heart rate and higher cortisol levels ( Kagan et al., 1987 ). Although we cannot extensively describe physiological differences between negative and positive reactivity infants in the current review, a robust collection of studies have identified temperament-linked differences in electroencephalogram (EEG) alpha power, sympathetic tone and baseline rate in the cardiovascular system, cortisol reactivity, the Event Related Negativity (ERN) waveform, and neural response to both threat and reward (for an in-depth description of methodology and group comparisons see Fox, Henderson, Pérez-Edgar, & White, 2008 ; Kagan & Snidman, 2004 ; McDermott et al., 2009 ; Schwartz et al., 2012 ).

Positive reactivity in infants on the other hand, may be the result of a high threshold of arousal, which likely affords infants the ease and comfort to navigate new social situations because they do not perceive such situations as threatening. Typically, Western personality preferences have led us to embrace the exuberant child, while simultaneously believing that fearfulness is a cause for concern ( Pérez-Edgar & Hastings, 2018 ). Although negative reactivity has more generally been associated with negative outcomes, such as anxiety ( Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009 ; McDermott et al., 2009 ), positive reactivity can also lead to maladaptive outcomes if unregulated (see below). For example, Morales, Pérez-Edgar, and Buss (2016) found that exuberant toddlers who scored low in regulation tasks showed increased attention bias to reward, and their exuberance predicted externalizing behaviors. Externalizing behaviors, in turn, have been associated with traits of low Agreeableness and low Conscientiousness , and can manifest behaviorally in aggression and antisocial behavior ( Miller, Lynam, & Jones, 2008 ).

Early temperamental traits can lead to lasting physiological and cognitive profiles particularly when embedded within a context that reinforces and magnifies their expression ( Rothbart & Bates, 2012 ). In contrast, some environments may actively (even if unconsciously) work to mitigate early traits that do not conform to desired behavioral and emotional patterns ( Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn2007 ). The progression from temperament reactivity to later child outcomes – including emergent personality – through environmental mechanisms that shape continuity may explain why a small percentage of BI infants develop acute social difficulties and clinical anxiety as early as adolescence ( Kagan, 2012 ), while most grow to be healthy, if a bit shy.

2.2.Temperamental regulation

Self-regulation is the modulation (upward or downward) of reactivity through the processes of attention, inhibition, approach and avoidance, functioning as a mechanism for reactive control ( Rothbart, Posner, & Kieras, 2006 ). For instance, an infant with high reactive control may be more likely to disengage from an unpleasant or negative stimulus in the environment (a scary toy) and focus attention elsewhere. Early in infancy, reactive control plays a crucial role in the expression of temperament because it directly modulates behavioral manifestations of reactivity. For example, the infant who is more likely to disengage attention from a negative stimulus will display less vocalization and motoric movement in response.

Temperamental regulation can also incorporate effortful control ( Rothbart, Ellis, Rueda, & Posner, 2003 ). Describing control as “effortful” reflects top-down processes that, unlike automatic reactive processes, are recruited voluntarily. For example, BI children with higher effortful control may more easily recruit strategies to regulate negative feelings in social situations, which can facilitate their social interactions. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is one of the main brain structures involved in effortful control, and along with the Executive Attention Network (EAN) have been extensively studied for their role on regulation abilities (for a review, see Rueda, Posner, & Rothbart, 2005 ; Henderson & Wilson, 2017 ). In summary, individual differences are evident in the way infants react to their environment and regulate environmental input. Thus, the behavioral manifestation of temperament is a product of the interplay between the infant’s motoric and emotional reactivity and the infant’s regulation capacity.

2.3.The contextual role of temperament

The interplay between temperamental reactivity and regulation becomes more nuanced as regulation becomes more effortful or voluntary. Recent evidence suggests that not all regulatory processes affect temperamental reactivity in the same fashion. White and colleagues (2011) examined a large sample of infants from 4-months to preschool age. They found that BI children with poor attention shifting were more likely to follow a developmental path to anxiety compared to BI children who were better at shifting their attention. This evidence, on its own, suggests that more robust regulation may buffer risk trajectories from fearful temperament to Neuroticism and psychopathology. However, White et al. (2011) found a different moderation pattern for inhibitory control, an associated, but distinct, component of self-regulation. Inhibitory control is the ability to stop an automatic or dominant impulse and to activate a subdominant response for the purpose of goal completion. Unlike attention shifting, high, and not poor, inhibitory control was associated with development of anxiety problems in BI children, a finding that has since been replicated (see Henderson & Wilson, 2017 ).

A nuanced understanding of regulation provides some explanation for the variability in developmental trajectories from temperamental reactivity to personality, which will depend in part on which regulatory processes are called upon by individual children. For example, training inhibitory control processes in exuberant children may buffer risk for externalizing problems, and, in the absence of externalizing tendencies, children may develop into more Agreeable and Conscientious adults. However, using the same strategy in behaviorally inhibited children could exacerbate negative reactivity and the risk for internalizing behaviors, which has been associated with adult Neuroticism ( Muris, Meesters, & Blijlevens, 2007 ). Together, these findings emphasize the differential effects of specific self-regulation components, and more importantly, point to the important role of temperament in tethering development to a given adult personality profile over others, and to influencing whether regulation comes to buffer or potentiate risk for psychopathology.

3. Developmental links from temperament to personality

There is now increasing evidence for links between temperament dimensions and the Big Five. The Five Factor Theory of personality helped distinguished between basic tendencies of personality ( Extraversion, Neuroticism, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness , and Openness to Experience ) and later emerging components that are largely driven by life events and personal experience (e.g., Characteristic Adaptations and Self-Concept ). The Big Five, which reflect endogenous characteristics driven by biological systems much like temperament, has proven to be a more suitable construct to assess developmental links between temperament and adult personality ( Shiner & Caspi, 2012 ).

The effort to link temperament to personality has mostly focused on how temperament dimensions of Positive Emotionality , Negative Emotionality , and Effortful Control assessed early in childhood predict differences in personality traits later. Positive Emotionality , given a context that reinforces its stability throughout childhood, likely develops into the broader trait of Extraversion , which includes positive emotions, the motivation to engage in social relationships, and the desire to seek rewarding cues in the environment ( Olino, Klein, Durbin, Hayden, & Buckley, 2005 ; Caspi & Shiner, 2006 ).

Negative Emotionality , in contrast is often linked with manifestations of Neuroticism . For example, De Pauw, Mervielde, and Van Leeuwen (2009) assessed 443 preschoolers on their temperament and personality traits concurrently, and found a large overlap between both constructs, and each positively correlated with internalizing behaviors. Furthermore, Slobodskaya and Kozlova (2016) examined longitudinal links between temperament dimensions assessed within infancy and toddlerhood, and personality traits in childhood. They found that high Negative Emotionality along with low Effortful Control in infancy predicted childhood Neuroticism . In fact, results from their path analysis indicated that Effortful Control in infancy predicts all three of the personality traits assessed in childhood: Extraversion , Conscientiousness , and Neuroticism . Although these results are preliminary given the limited sample size and large variation of time intervals between assessments, they support the contextual role of temperamental regulation in the development of later personality. As previously discussed, Effortful Control is characterized by regulatory abilities that facilitate soothability in infancy, and the ability to inhibit dominant impulses and voluntarily shift attention when necessary to achieve a goal. This dimension has been linked to Conscientiousness , Extraversion , and generally adaptive traits in adult personality ( Halverson et al., 2003 ).

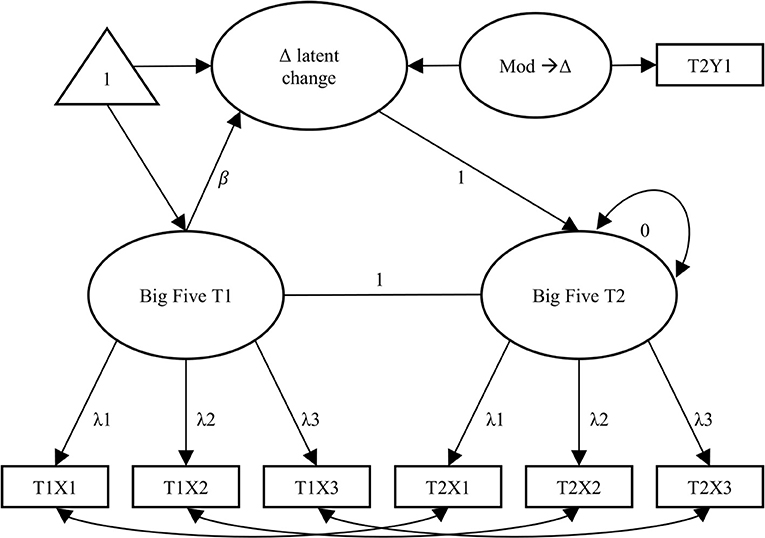

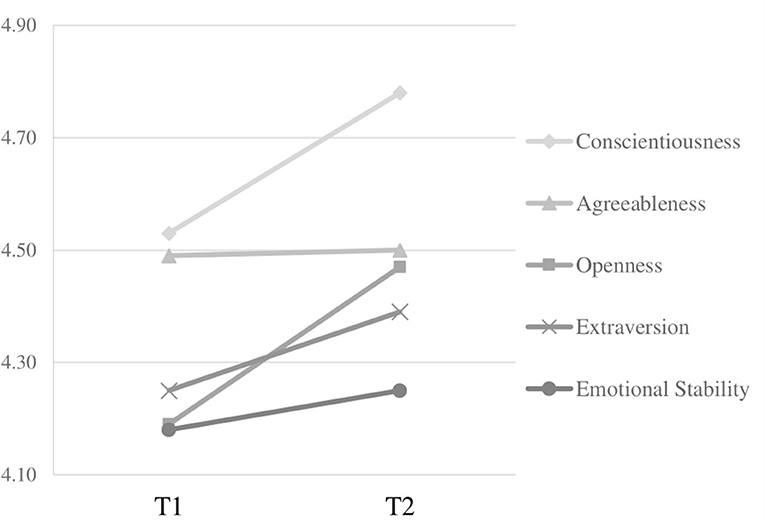

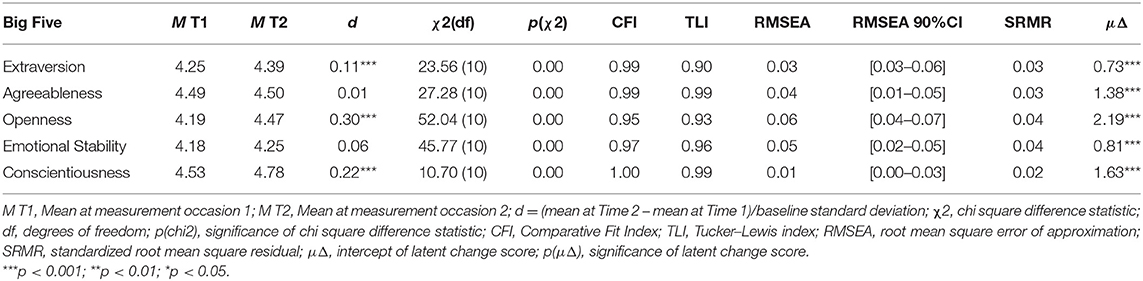

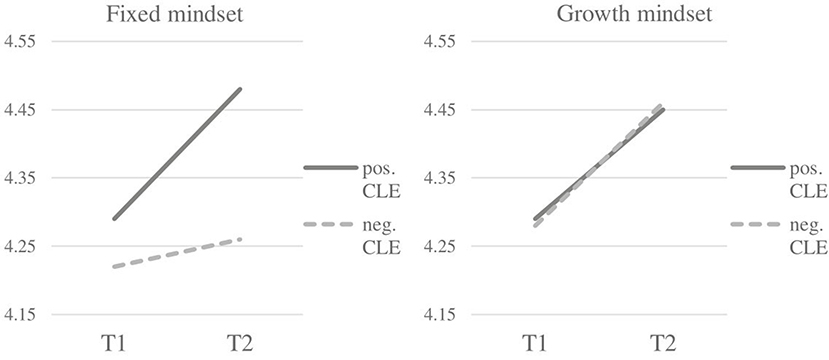

The extant literature supports moderate links between individual differences in infant temperament and later personality traits, while also suggesting that temperament does not predict personality in a deterministic way. What then is the developmental trajectory from infant temperament to childhood and adult personality? We believe the dynamic interaction between temperament-linked individual differences in infancy and early contextual factors leads to emergence of personality traits in childhood, as depicted in the left portion of Figure 1 . As these traits continue to actively and evocatively interact with the environment from infancy throughout childhood and adolescence, they increasingly become more context- and person-specific, resulting in the distinct personality profiles observed in adulthood ( Shiner & Caspi, 2012 ).

Mechanisms of change from temperament to personality Development

For example, “goodness of fit” refers to the extent that a child’s temperament is compatible with the context of development. This term was proposed by Chess and Thomas (1991) to describe the relational or dynamic aspect of temperament. The term “fit” implies a synchrony or transaction between temperament and context, and fit is considered “good” when the environment can meet the demands of a child’s temperament and provides opportunities for growth and sets expectations for regulation that are in accordance with that temperament. Dissonance between temperament and contextual demands would be considered a poor fit, and could potentially lead to maladaptive outcomes. The dynamic interaction between temperament and context may buffer or exacerbate the evolution of temperament traits into personality traits ( Shiner & Caspi, 2012 ).

For instance, a recent study by van der Voort and colleagues (2014) reported the longitudinal buffering effects of maternal sensitivity on children’s inhibited temperament. They followed a sample of 160 adopted infants into the adolescent years, assessing patterns of anxious and depressed behaviors. Although inhibited temperament was a strong predictor of socially reticent behaviors in middle childhood and internalizing problems in adolescence, maternal sensitivity measured at both infancy and middle childhood interacted with inhibited temperament to predict less internalizing problems in adolescence. Sensitivity may allow parents to more readily perceive fearful and vigilant cues in their inhibited infant, and provide more support in those instances in which the infant needs reassurance of safety. Conversely, if parenting behaviors do not fit the infant’s temperamental demands, inhibited and fearful tendencies could be further reinforced throughout childhood.

A good example comes from a series of studies from Kiel and Buss (2010 ; 2011 ; 2012 ; 2013) . Initially, they found that the relation between fearful temperament and protective parenting was stronger when mothers were more accurate in predicting or anticipating their children’s fearful responses ( Kiel & Buss, 2010 ). Presumably, this accurate anticipation increased the likelihood that mothers of fearful children would respond with protection in novel situations, which then perpetuated temperamental fearfulness. In a follow-up study, they maternal accuracy in anticipating fearful responses and protective parenting in toddlerhood was linked to social withdrawal at kindergarten entry ( Kiel & Buss, 2011 ). More recently, they have also shown that it is protective parenting in low-threat , but not high-threat situations that relates to fearful temperament ( Kiel & Buss, 2012 ). This pattern implies that ‘overprotective’ parenting behaviors, even if superficially ‘sensitive’, may potentiate risk from fearful temperament to later internalizing behaviors, anxiety, and high levels of Neuroticism .

In summary, we presume that temperament dimensions and the Big Five personality traits share underlying biological systems that drive their commonalities. When these basic, biological tendencies of adult personality are examined in isolation from the influence of life experience, moderate to strong links with temperament begin to emerge ( McCrae et al., 2000 ; Rothbart, 2011 ; Zentner & Bates, 2008 ). Such links suggest that temperament and personality traits may in essence be the same construct, differentiated only by the developmental point at which they are expressed ( Slobodskaya & Kozlova, 2016 ). Supporting this notion, Shiner and Caspi (2012) argue that personality traits are different from temperament dimensions in that the former include components that are only expressed when individuals develop more advanced cognitive abilities and self-awareness. They explain links between temperament and personality traits in terms of an outward expansion of children’s temperament. Specifically, as children develop and continue to be influenced by experience, life events, and social interactions, the expression of temperament expands beyond individual differences in basic reactivity and emotion, to more nuanced differences in intricate systems such as motivation, goal setting, beliefs, and views of self and others. We build on their cognitive-focused model, and argue that parenting practices form part of those experiences, life events, and social interactions that drive the expansion of temperament. Our developmental model in Figure 1 is in line with Shiner and Caspi’s (2012) view, depicting personality traits as biologically rooted in temperament, and interacting with early context and life experience to shape adult personality.

As previously stated, despite moderate links between temperament and personality traits there remains considerable unexplained variance in adult functional profiles after accounting for temperament and personality traits. At the very least we see moderate environmental influences on personality development even beyond the context of early childhood. We depict extended role of the environment in the center portion of Figure 1 , in agreement with McCrae et al.’s (2000) argument that the environment likely conditions the way in which personality evolves through adulthood.

Taking an even broader perspective, we believe the transactions between the individual and the environment depicted in our model are also dynamically embedded within the larger cultural context of family systems, socio-cultural expectations, and intergenerational processes that may exert important influence on child characteristics and contextual expectations ( Poole, Tang, & Schmidt, in press ). In essence, we suggest that context actively shapes the emergence and expression of personality through dynamic transactions between temperament and environmental factors. These transactions may happen via moderating effects of temperament, as well as bidirectional effects in which temperament elicits or evokes the environmental inputs children encounter, and consequently these environmental inputs gradually shape the expression of temperament (Oppenheimer, Hankin, Jenness, Young, & Smolen, 2013), creating a loop of experience-expectant and experience-dependent transactions. We explore this transactional relationship between child temperament and context using parenting as one example of early environmental influences on personality development.

4. The Parenting Context

Parents have direct genetic influences on children’s temperament and personality ( Scott et al., 2016 ). In addition, passive gene-environment correlations mean that parenting practices, as well as the choices parents make in shaping their child’s environment, are influenced by shared genetic characteristics. In this way, parents have both direct and indirect genetic effects on their child’s developmental outcomes. Thus, as we discuss the contextual influences of parenting on child temperament and personality, it is important to keep in mind that any behavioral influence parents have on their children is also likely to carry a genetic component.

Parents create most of the immediate setting in which infants develop, namely the home and the interpersonal environment, including the face-to-face relationships that take place there. These affordances make parents active agents in children’s social and emotional context, specifically through early parenting style and practices ( Belsky et al., 2007 ). For example, when parents respond to their infant’s cry with soothing and support, they are providing the means for infant emotion regulation. Similarly, in the presence of a stranger or novel situation, a parents’ facial cues (e.g., smile) signal to the infant whether the social context is safe or dangerous. Variations in parenting behavior directly impact the formation of the attachment relationship, and attachment relationships, in turn, influence children’s socioemotional competence and personality over time ( Lewis-Morrarty et al., 2015 ; Stevenson-Hinde, Chicot, Shouldice, & Hinde, 2013 ).

Additionally, parents also shape the infant’s social context beyond the immediate family setting, such as the peer environment. For example, before children gain autonomy, their parents choose what play activities children can engage in (e.g., story time at the library), and the playmates children can interact with. Parents continue to influence their children as they pass though important developmental transitions, such as school entrance, puberty and adolescence. These are periods when children undergo identity exploration and active reorganization of their social world (e.g., romantic relationships), which have relevant theoretical implications for the development of personality ( Reitz, Zimmermann, Hutteman, Specht, & Neyer, 2014 ; Syed, & Seiffge-Krenke, 2013 ).

4.1. Theoretical models of parenting influence

Theorists have proposed several mechanisms through which parenting can shape child outcomes, specifically the development of personality. Bowlby was one of the first to discuss the development of “internal working models” based on the parent-child attachment relationship ( Bowlby, 1980 ). The central tenet of working models is that children internalize representations about “the self” from the dynamic and transactional interactions between them and their caregiver ( Bretherton, 1990 ). Furthermore, children adopt working models of behavior based on the quality of these interactions that they then carry onto other contexts (e.g., school). In essence, parenting quality can influence children’s concept of who they are and how others view them. Additionally, parenting quality can also influence children’s manifestation of personality traits. For example, children who experience harsh punishment and controlling parenting may perceive themselves as unworthy or unlovable, and model intrusive and controlling behaviors that could then lead to low agreeableness or high neuroticism.

Environmental elicitation is a second mechanism theorized to explain relations between the parenting context and personality development. Here, a child’s individual characteristics can elicit specific parenting behaviors ( Shiner & Caspi, 2003 ). For example, a “difficult temperament”, which is a term used to describe infants who are easily irritable, cry often, and are hard to sooth, may elicit frustration in the parent and lead to harsh, controlling parenting or even rejection. The environmental elicitation model can be traced back to an organismic view of development, where changes arise from within the organism (e.g., the child) as the organism actively acts on the world and evokes responses from the environment ( Overton, 2015 ).

A caveat to the environmental elicitation model is that research now suggests a more dynamic approach may be at play, where the elicited environmental responses may be as dependent on environmental characteristics as they are on child characteristics ( Lerner, Rothbaum, Boulos, & Castellino, 2002 ). This is reflected in the bidirectional effects between child and context in Figure 1 . Children’s individual characteristics in tandem with parental individual characteristics can influence the type and quality of parenting response. For example, some studies suggest that parents with higher education levels are more likely to show warmth and support in response to a difficult child, whereas parents with low educational attainment are more likely to respond with harsh control and reciprocal negative affect ( Paulussen-Hoogeboom, Stams, Hermanns, & Peetsma, 2007 ). This approach to environment elicitation can be traced back to Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological framework of development, in which developmental change is theorized to occur through dynamic transactions between organism and immediate environment, and where the individual characteristics of the organism and the characteristics of the environment are equally important in these interactions (for an overview, see Rosa & Tudge, 2013 ).

The working model of behavior and the environmental elicitation model are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and there is empirical evidence suggesting that they may in fact work simultaneously within the framework of parenting and personality development. For example, Van den Akker and colleagues (2014) examined personality development from age 6 to age 20 along with maternal over-reactivity and warmth. The sample included 596 children and their mothers, who reported on their children’s personality traits at five different time points throughout the study, as well as their parenting practices. Van Den Akker and colleagues found that high maternal over-reactivity predicted decreases in Conscientiousness at later time points, and high maternal warmth predicted decreases in emotional stability, which would be reflected in high Neuroticism . This finding echoes the earlier work of Buss and Keil (2011 ; 2012) .

Additionally, the authors also reported that increases in benevolence, which is a characteristic of Agreeableness , predicted later increases in maternal warmth and decreases in over-reactivity. Similarly, high Extraversion in childhood predicted increases in maternal over-reactivity and warmth. Although these results merit replication and further investigation of why specific traits are more reinforced or discouraged by different parenting practices, they nonetheless provide valuable evidence for bidirectional effects between temperament and early context. Additionally, they provide convincing evidence that environmental elicitation and working models of behavior are two mechanisms simultaneously at play, producing dynamic transactions between personality traits and parenting.

4.2. Parenting practices and personality development

The literature has largely focused on specific types of parenting behaviors associated with positive or negative child socioemotional outcomes. Although the aim of this paper is to review the parenting context in interaction with intrinsic child factors, it is worth summarizing briefly the findings that initially emerged when examining the main and direct effects of parenting on child outcomes. Two major dimensions have been used to describe parenting quality: parental warmth or sensitivity and parental control. Parental warmth is a global construct that usually reflects positive parenting behaviors. These behaviors may include measures of sensitivity, support, positive affect, and responsiveness among others ( Behrens, Parker, & Kulkofsky, 2014 ). Warm and responsive parenting has been consistently associated with higher levels of social and emotional competence. For example, Raby, Roisman, Fraley, and Simpson (2015) reported on the socioemotional development of 243 individuals followed from infancy to adulthood. Behavioral expressions of maternal sensitivity were also measured at different time points throughout infancy, as early as three months of age. They found that early maternal sensitivity significantly predicted social competence across childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Furthermore, these effects remained significant after accounting for potential child-context developmental transactions, such as children independently choosing more aspects of their environment as they grow in autonomy. These results not only highlight the important role of parenting on child outcomes but also the general, enduring impact of early context on children’s social development.

Positive parenting practices have also been associated with more specific aspects of social development, such as prosocial behavior. Prosocial behavior encompasses tendencies for sharing, helping, and cooperating for the purpose of benefiting someone other than the self ( Eisenberg, Eggum-Wilkens, & Spinrad, 2015 ), and has been implicated in adolescent and adult Agreeableness ( Habashi, Graziano, & Hoover, 2016 ; Luengo et al., 2014 ). Daniel, Madigan, and Jenkins (2016) assessed parenting warmth in both mothers and fathers in relation to toddlers’ prosocial behavior in a sample of 239 families. They found that both maternal and paternal warmth at 18 months predicted increases in prosocial behavior at 36 and 54 months, which is in line with the enduring effects of sensitivity reported by Raby et al. (2015) . Beyond predicting changes in prosocial behavior, Domitrovich and Bierman (2001) reported that supportive parenting also predicted social competence through associations with low levels of child aggression, and buffered children from the negative effects of peer dislike. Although partially limited by the cross-sectional design, these results and findings previously discussed suggest that warm supportive parenting has lasting positive effects on children’s later ability to navigate their social world. These effects, in turn, impact the form and expression of adult personality.

Multiple forms of parental control have been studied, including measures of parental harsh intrusiveness, dominance, and pressure, in contrast to gentle guidance and scaffolding behaviors that encourage child autonomy ( Grolnick & Pomerantz, 2009 ). Harsh control and intrusive parenting predict poor socioemotional competence ( Parker & Benson, 2004 ; van Aken, Junger, Verhoeven, & Dekovic, 2007 ). In a longitudinal study, Taylor, Eisenberg, Spinrad, and Widaman (2013) assessed children’s effortful control and intrusive parenting at 18, 30, and 42 months. Intrusive parenting was behaviorally coded from a series of mother-child interactions, including a teaching task, a free-play task, and a clean-up task. Taylor and colleagues found that parents’ intrusiveness was negatively related to later assessments of child effortful control, which encompasses regulatory skills such as attention shifting and emotion regulation that are relevant for social interactions. Furthermore, effortful control mediated the association between intrusive parenting and poor ego resiliency, which is a personality characteristic that reflects adaptability and flexibility to changes in the environment, and it is associated with social competence ( Hofer, Eisenberg, & Reiser, 2010 ).

Further highlighting the negative effects of harsh control, Wiggins and colleagues (2015) reported on the developmental trajectories of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in relation to harsh parenting from a large sample of children assessed at ages 3, 5, and 9 years. They found that a trajectory of increasing harsh parenting uniquely predicted a severe trajectory of externalizing symptoms, and was negatively associated with internalizing symptoms. These results suggest that harsh, controlling parenting may lead children to model these behaviors with their peers, causing social conflict and rejection, which may further reinforce the negative behaviors.

Despite significant contributions made in establishing direct links between parenting quality and child outcomes, a great deal of evidence suggests that parenting dimensions do not affect children in the same way ( Slagt et al., 2016 ). In some cases, parenting may only relate to social development through variables that moderate or mediate its effects, such as gender, genetic variability, or personality ( Lianos, 2015 ; Rabinowitz & Drabick, 2017 ).

In fact, Lianos (2015) assessed preadolescents’ personality traits in relation to the parenting style they received, and found that the association between parenting quality and social competence varied by children’s personality. Specifically, high parental rejection was significantly associated with lower social competence only for preadolescents low in Neuroticism , whereas individuals high in Neuroticism were as socially competent as children who did not experience parental rejection. Similarly, high parental overprotection seemed more detrimental for preadolescents low in Agreeableness and Extraversion , as they were significantly less socially competent than children who scored high on these traits, or children who did not experience overprotective parenting. These transactions between emerging personality traits and environmental factors are theoretically depicted in our developmental model ( Figure 1 ), and may also represent an enduring pattern of transactions carried over from infancy. Lianos’ findings also highlight the importance of examining the role of parenting context as a moderator of developmental links between children’s individual characteristics and later outcomes, including the final piece in our model: Personality Profiles . We next review the intersection of individual differences and parenting context in predicting personality development, describing the theoretical models employed so far, synthesizing the current findings, and suggesting areas that warrant further research.

4.3. Temperament reactivity and parenting

Positive reactivity, which is typically reflected by extreme high approach and excitement in the face of novelty, has been largely understudied in relation to parenting behaviors. There is some cross-sectional evidence to suggest that positive reactivity is associated with parental warmth ( Latzman, Elkovitch, & Clark, 2009 ), but such associations cannot clearly distinguish bidirectional effects and could be explained by gene-environment correlations or heritability of parents’ temperament. Longitudinal studies could elucidate the direction of these associations. However, few studies have reported longitudinal assessments between positive reactivity and parenting, especially in infancy.

Lengua and Kovacs (2005) assessed temperament and parenting using both children’s and parents’ report of these variables at two time points. They found that initial positive reactivity predicted higher levels of maternal acceptance, which supports the elicitation model. The authors suggested that the positive characteristics of these children, such as laughter and approach, may be perceived by parents as rewarding and elicit acceptance and warmth. Interestingly, the authors did not find support for the working model of behavior, as initial parental acceptance did not predict changes in positive reactivity.

Even fewer studies have considered the parenting context as a moderator of links between positive reactivity and later socioemotional adjustment, including personality development. Positive reactivity may have a protective effect against negative parenting behaviors, such as maternal rejection, physical punishment, and harsh control ( Lengua, Wolshick, Sandler, & West 2000 ; Lahey et al., 2008 ). For instance, children who are high in approach and positive emotionality may elicit more engagement and positive reactions from adults. In the face of negative parenting, children’s positive reactivity may facilitate deep and positive connections with other adults, who may then serve as an attachment figure that provides some emotional and social guidance for the child ( Werner, 1993 ). This particular area of study could benefit from longitudinal studies assessing positive reactivity and parenting over longer periods, and perhaps earlier in development. Multiple time point data could more directly examine the working model of behavior and the environmental elicitation model simultaneously, assessing whether changes in positive reactivity are only evident after longer time intervals. Additionally, the lack of parenting effects on positive reactivity may be the result of exploring this association later in childhood, as evident bidirectional effects may be more pronounced earlier in development when parents have greater control over the child’s daily experiences.

Negative reactivity has received far more attention than positive reactivity in this literature, perhaps because of its intuitive links to maladaptive outcomes. As previously explained, the global dimension of “difficult temperament” includes characteristics of irritability, high fear, and soothing difficulty, and it has been associated with lower maternal support and responsiveness, and higher parental disapproval and hostility ( Boivin et al., 2005 ; Gauvain, 1995 ). However, a meta-analysis of this relation ( Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al., 2007 ) suggests that results are mixed, and in some cases, may depend on other child characteristics (e.g., gender), and demographic variables (e.g., mother education).

In the case of fearfulness, some findings indicate a positive association with parental warmth and acceptance ( Lengua & Kovacs, 2005 ), whereas others have found longitudinal links to less negative parenting. Lengua (2006) assessed children’s temperamental fear and irritability as well as maternal rejection and discipline practices at three different time points over the course of three years. The sample included 190 children between the ages of 8 and 12, and their mothers. Latent growth modeling revealed that although initial levels of fear were concurrently related to higher levels of maternal rejection and inconsistent discipline, they predicted decreases in these negative parenting dimensions at later time points. Interestingly, initial irritability was also concurrently associated with higher maternal rejection, but it did not uniquely predict changes in rejection. In fact, irritability was associated with higher inconsistent discipline and it also predicted later increases in this dimension.

This interesting pattern of results point to the differential effects of specific temperamental characteristics on parenting, and to the potential for change in temperament given elicited changes in parenting toward higher warmth and less over-reactive control. For example, an infant who is extremely fearful to novelty and high in negative affect may be at risk for early internalizing problems given temperamental stability. However, if such fearful temperament elicits higher maternal warmth and support, coupled with more scaffolding and gentle control, changes in parenting could elicit decreases in fearfulness and negative emotionality, and might decrease the risk of developing adult personality traits of high Neuroticism and low Agreeableness . This is the central developmental pattern we depict in the first and second stages of Figure 1 , with bidirectional effects between child intrinsic characteristics and contextual factors.

This transaction pattern is in line with Differential Susceptibility Theory (DST; Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2011 ). DST postulates that some individual characteristics of an organism (e.g., temperament) may render it more sensitive to contextual influences (e.g., parenting) such that when faced with a negative context, the organism will show a worse outcome. However when embedded in a positive environment, the organism will benefit the most and perform the best. Children who possessed characteristics that increase sensitivity to context then develop “for better or for worse”, because they either thrive in privileged environments or struggle in adverse circumstances. Our theoretical model can encompass DST because we purposefully leave strength and valence of effects unspecified, acknowledging that the strength and direction of contextual influence may be conditioned by child characteristics. The extant literature supports a pattern in which children high in negative reactivity show high socioemotional competence in the context of maternal warmth and autonomy-supporting parenting ( Bradley & Corwyn, 2008 ). However, the other side of the coin has also been reported. Children high in negative reactivity whose parents report harsh control and low warmth show further continuity of negative reactivity and behavioral problems (Engle & McElwain, 2011; Feng, Shaw, & Moilanen, 2011 ), lower social adjustment ( Stright, Gallagher, & Kelley, 2008 ), and higher neurophysiological risk for anxiety ( Brooker & Buss, 2014 ). These overall patterns suggest that children high in reactivity may present with typically positive personality traits, such as Agreeableness or Conscientiousness , or more negative traits, such as Neuroticism , based on their developmental context. However, as noted above, there are limits to both sensitivity and the power of the environment. As such, it is very unlikely that a child sensitive to the environment due to negative reactivity will, even under the best of circumstances, show high levels of Extraversion .

4.4. Temperament regulation and parenting

Studies of temperament regulation usually include behavioral measures of effortful control, which is manifested on attention sustaining, perseverance, and low frustration in the face of difficulty ( Rueda, 2012 ). A large number of studies suggest that maternal warmth and supportive parenting are associated with higher levels of effortful control (for a meta-analysis, see Karreman, Van Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković, 2006 ). A study by Chang and colleagues (2015) investigated relations between effortful control and proactive parenting from age two to five. Initial levels of proactive parenting, characterized by practices of scaffolding and structured play, predicted increases in effortful control at age five. This result remained significant even after accounting for language skills, which is a significant predictor of effortful control.

There is also some empirical support for the eliciting effects of effortful control on parenting. Higher levels of self-regulation have been associated with more maternal support and less rejection ( Kennedy, Rubin, Hastings, & Maisel, 2004 ; Lengua, 2006 ). However, the studies are scarce and some of the results have been moderated by child’s gender or have systematically varied by parent (e.g., father vs. mother; Lifford, Harold, & Thapar, 2009 ). Future studies should further examine the circumstances in which effortful control predicts changes in parenting, especially because a more recent study did not find support for such elicitation effects ( Taylor et al., 2013 ). Overall, both elicitation and shaping effects between parenting and temperament regulation are important to personality development, because early effortful control has been associated with later personality traits of high Conscientiousness and Agreeableness ( Rueda, 2012 ).

Besides exploring bidirectional effects, the literature has narrowed in on the interaction between self-regulation and parenting to predict child outcomes. A consistent pattern of results has emerged in the past 15 years: parenting practices appear especially important for the socioemotional development of children with low effortful control (for a meta-analysis, see Slagt et al., 2016 ). Other studies have replicated this pattern and provided support for unique environmental effects of the parenting context. For instance, Reuben et al. (2004) examined parenting, effortful control, and externalizing behaviors using a longitudinal adoption design in 225 families, including adoptive and birth parents. Adoptive maternal warmth predicted decreases in externalizing behaviors only for children with low effortful control. This study in particular highlights the importance of the parenting context and points to its contextual influence on children’s development independent from any shared genetic variance.

5. Conclusions

Personality has for decades been theorized to originate from temperament. However, we rarely see direct links between temperament and personality, suggesting that biologically determined profiles of temperament are not the only forces at work in shaping developmental trajectories. Instead, the current body of evidence suggests that adult personality develops along pathways influenced by environmental factors, such as the parenting context, that shape the continuity and manifestation of early-appearing biological differences.

Infant temperament probably begins to interact with parenting practices early in development, and these transactions can reinforce or discourage continuity of temperament and personality development. Infants’ behavioral and emotional reactivity elicits an array of parenting responses in order to meet the infant’s needs. Additionally, more recent findings also suggest that the elicited parenting behaviors and practices are dependent on the parent’s individual characteristics, and they can in turn shape the child’s temperamental characteristics. Empirical evidence that parenting can explain changes in temperament and that temperament can elicit changes in parenting is compatible with the “goodness of fit” transactional model proposed by Thomas and Chess (1991) . This model can also account for the moderating effects of infants’ temperament on the association between parenting behaviors and child outcomes. Both the theoretical model and the extant evidence highlight that a match between parenting and temperament, rather than a universal construct of “good parenting”, seems to be relevant in predicting personality development.

A growing literature suggests that parenting interacts with temperament to affect socioemotional development, especially pointing to the possibility that some temperament dimensions may be more vulnerable than others to the detrimental effects of a negative parenting context ( Slagt et al., 2016 ). Although the patterns are not always consistent across developmental periods, specific temperament dimensions, or parenting practices ( Rabinowitz & Drabick, 2017 ), the evidence is nonetheless indisputable that context, in the form of parenting, can moderate the relationship between temperament-linked individual differences and child outcomes. Additionally, the extant findings suggest that the intersection of temperament and parenting should be investigated as a dynamic, transactional relation. If it is to be fully understood, investigators should employ more longitudinal studies where both child temperament and parenting behaviors are observed at multiple time points, and their transactions considered to predict personality development ( Slagt et al., 2016 ). Finally, the complexity of temperament-parenting transactions also implies the possibility of simultaneous child and parent individual characteristics playing a functional role in the personality traits that children later express. Bronfenbrenner emphasized the importance of such simultaneously occurring characteristics:

Proximal processes that affect development vary systematically as a joint function of the characteristics of the developing person and the environment (both immediate and more remote) in which the processes are taking place ( Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1993 , p. 317).

To the extent that we consider personality to be a developmental process, Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory informs our current understanding of how personality develops in context. By his account, individual characteristics of the child and the context will inevitably affect the nature of their transaction, and therefore should be carefully considered in our designs. For example, child gender has occasionally been found to moderate the influence of effortful control on later parenting practices ( Lifford, Harold, & Thapar, 2008 ). This moderation calls for a comprehensive, holistic account of the child in our designs and measurement models, rather than including isolated individual characteristics that may only represent one portion of the child’s experienced “truth”. Similarly, caregiver role, parent psychopathology, education level, and household size are all characteristics of the parenting context that could influence “proximal processes” or parent-child transactions, and thus should be reflected in our studies. In conclusion, when examining personality development, transactions between child and parent over time are crucial, and these complex, dynamic relations can only inform the trajectory to adult personality when multiple individual characteristics of both entities (i.e., organism and context) are carefully considered.

Supplementary Material

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Barenbaum NB, Winter DG. History of modern personality theory and research. In: John OP, Robin RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 3–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Behrens KY, Parker AC, Kulkofsky S. Stability of maternal sensitivity across time and contexts with Q-Sort Measures. Infant and Child Development. 2014; 23 :532–541. doi: 10.1002/icd.1835. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. For better and for worse: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Current directions in Psychological Science. 2007; 16 :300–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boivin M, Perusse D, Dionne G, Saysset V, Zoccolillo M, Tarabulsy GM, Tremblay RE. The genetic-environmental etiology of parents' perceptions and self-assessed behaviours toward their 5-month-old infants in a large twin and singleton sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005; 46 :612–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00375.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Volume3. Loss: Sadness and depression. NewYork: Basic Books; 1980. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Infant temperament, parenting, and externalizing behavior in first grade: a test of the differential susceptibility hypothesis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008; 49 :124–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01829.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bretherton I. Communication patterns, internal working models, and the intergenerational transmission of attachment relationships. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1990; 11 :237–252. doi: 10.1002/1097-0355(199023)11. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Heredity, environment, and the question “how?” A first approximation. In: Plomin R, McClern GG, editors. Nature, Nurture, and Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1993. pp. 313–323. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brooker RJ, Buss KA. Harsh parenting and fearfulness in toddlerhood interact to predict amplitudes of preschool error-related negativity. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2014; 9 :148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2014.03.001. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Caspi A, Shiner RL. Personality development. In: Damon W, Lerner R, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. 6. New York, NY: Wiley; 2006. pp. 300–365. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chang H, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, Wilson MN. Proactive parenting and children’s effortful control: Mediating role of language and indirect intervention effects. Social Development. 2015; 24 :206–223. doi: 10.1111/sode.12069. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chess S, Thomas A. Temperament and the concept of goodness of fit. In: Strelau J, Angleitner A, editors. Explorations in Temperament: Perspectives on Individual Differences. Boston, MA: Springer; 1991. pp. 15–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Pérez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, Fox NA. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009; 48 :928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Daniel E, Madigan S, Jenkins J. Paternal and maternal warmth and the development of prosociality among preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2016; 30 :114–124. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Pauw SS, Mervielde I, Van Leeuwen KG. How are traits related to problem behavior in preschoolers? Similarities and contrasts between temperament and personality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009; 37 :309–325. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9290-0. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Domitrovich CE, Bierman KL. Parenting practices and child social adjustment: Multiple pathways of influence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2001; 47 :235–263. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2001.0010. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edwards A, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Reiser M, Eggum-Wilkens ND, Liew J. Predicting sympathy and prosocial behavior from young children’s dispositional sadness. Social Development. 2015; 24 :76–94. doi: 10.1111/sode.12084. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eisenberg N, Eggum-Wilkens ND, Spinrad TL. The development of prosocial behavior. In: Schroeder DA, Graziano WG, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial behavior. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 114–136. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. Differential susceptibility to the environment: An evolutionary- neurodevelopmental theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2011; 23 :7–28. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000611. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Feng X, Shaw DS, Moilanen KL. Parental negative control moderates the shyness-emotion regulation pathway to school-age internalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011; 39 :425–436. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9469-z. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Pérez-Edgar K, White L. The biology of temperament: An integrative approach. In: Nelson CA, Luciana M, editors. The Handbook of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008. pp. 839–854. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, Schmidt LA. Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001; 72 :1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gauvain M. Child temperament as a mediator of mother-toddler problem solving. Social Development. 1995; 4 :257–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.1995.tb00065.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM. Attachment in the Preschool Years: Theory, Research, and Intervention. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grolnick WS, Pomerantz EM. Issues and challenges in studying parental control: Toward a new conceptualization. Child Development Perspectives. 2009; 3 :165–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00099.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Habashi MM, Graziano WG, Hoover AE. Searching for the prosocial personality: A big five approach to linking personality and prosocial behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2016; 42 :1177–1192. doi: 10.1177/0146167216652859. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Halverson CF, Deal JE. Temperamental change, parenting, and the family context. In: Wachs TD, Kohnstamm GA, editors. Temperament in Context. Mahwah, NI: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 61–79. [ Google Scholar ]

- Halverson CF, Havill VL, Deal J, Baker SR, Victor JB, Pavlopoulos V, Wen L. Personality structure as derived from parental ratings of free descriptions of children: The Inventory of Child Individual Differences. Journal of Personality. 2003; 71 :995–1026. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106005. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Henderson HA, Wilson MJ. Attention Processes Underlying Risk and Resilience in Behaviorally Inhibited Children. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports. 2017; 4 :99–106. doi: 10.1007/s40473-017-0111-z. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofer C, Eisenberg N, Reiser M. The role of socialization, effortful control, and ego resiliency in french adolescents’ social functioning. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010; 20 :555–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00650.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huizink A. Prenatal influences on temperament. In: Zentner M, Shiner RL, editors. Handbook of Temperament. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 297–314. [ Google Scholar ]

- John OP, Naumann LP, Soto CJ. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: John OP, Robin RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 114–158. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller JD, Lynam DR, Jones S. Externalizing behavior through the lens of the five-factor model: A focus on agreeableness and conscientiousness. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2008; 90 :158–164. doi: 10.1080/002238907018452. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kagan J. The biography of behavioral inhibition. In: Zentner M, Shiner RL, editors. Handbook of Temperament. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 69–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Development. 1987; 58 :1459–1473. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kagan J, Snidman N. The Long Shadow of Temperament. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Karreman A, van Tuijl C, van Aken MAG, Deković M. Parenting and self-regulation in preschoolers: A meta-analysis. Infant and Child Development. 2006; 15 :561–579. doi: 10.1002/icd.478. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kennedy AE, Rubin KHD, Hastings P, Maisel B. Longitudinal relations between child vagal tone and parenting behavior: 2 to 4 years. Developmental Psychobiology. 2004; 45 :10–21. doi: 10.1002/dev.20013. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Maternal accuracy and behavior in anticipating children's responses to novelty: Relations to fearful temperament and implications for anxiety development. Social Development. 2010; 19 :304–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00538.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Prospective relations among fearful temperament, protective parenting, and social withdrawal: The role of maternal accuracy in a moderated mediation framework. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011; 39 :953–966. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9516-4. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Associations among context-specific maternal protective behavior, toddlers' fearful temperament, and maternal accuracy and goals. Social Development. 2012; 21 :742–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00645.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Toddler inhibited temperament, maternal cortisol reactivity and embarrassment, and intrusive parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013; 27 :512–517. doi: 10.1037/a0032892. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lahey BB, Hulle CAV, Keenan K, Rathouz PJ, D’Onofrio BM, Rodgers JL, Waldman ID. Temperament and parenting during the first year of life predict future child conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008; 36 :1139–1158. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9247-3. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Latzman RD, Elkovitch N, Clark LA. Predicting parenting practices from maternal and adolescent sons’ personality. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009; 43 :847–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.05.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lengua LJ. Growth in temperament and parenting as predictors of adjustment during children’s transition to adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006; 42 :819–832. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.819. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lengua LJ, Kovacs EA. Bidirectional associations between temperament and parenting and the prediction of adjustment problems in middle childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005a; 26 :21–38. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2004.10.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lengua LJ, Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, West SG. The additive and interactive effects of parenting and temperament in predicting adjustment problems of children of divorce. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000; 29 :232–244. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_9. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lerner RM, Rothbaum F, Boulos S, Castellino DR. Developmental systems perspective on parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting. Vol. 2. Mawah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 315–344. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis-Morrarty E, Degnan KA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Henderson HA, Fox NA. Infant attachment security and early childhood behavioral inhibition interact to predict adolescent social anxiety symptoms. Child Development. 2015; 86 :598–613. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12336. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lianos PG. Parenting and social competence in school: The role of preadolescents’ personality traits. Journal of Adolescence. 2015; 41 :109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lifford KJ, Harold GT, Thapar A. Parent-child relationships and ADHD symptoms: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008; 36 :285–296. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9177-5. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lifford KJ, Harold GT, Thapar A. Parent-child hostility and child ADHD symptoms: a genetically sensitive and longitudinal analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009; 50 :1468–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02107.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luengo Kanacri BP, Pastorelli C, Eisenberg N, Zuffianò A, Castellani V, Caprara GV. Trajectories of prosocial behavior from adolescence to early adulthood: Associations with personality change. Journal of Adolescence. 2014; 37 :701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.013. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. The Five-Factor Theory of personality. In: John OP, Robin RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 159–181. [ Google Scholar ]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT, Jr, Ostendorf F, Angleitner A, Hřebíčková M, Avia MD, Saunders PR. Nature over nurture: Temperament, personality, and life span development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000; 78 :173. 1O.1037//O022-3514.7S.1.173. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McDermott JM, Pérez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry. 2009; 65 :445–448. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.043. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller JD, Lynam DR, Jones S. Externalizing behavior through the lens of the five-factor model: A focus on agreeableness and conscientiousness. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2008; 90 :158–164. doi: 10.1080/00223890701845245. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miskovic V, Schmidt LA. Frontal brain electrical asymmetry and cardiac vagal tone predict biased attention to social threat. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2010; 75 :332–338. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morales S, Pérez-Edgar K, Buss K. Longitudinal relations among exuberance, externalizing behaviors, and attentional bias to reward: the mediating role of effortful control. Developmental Science. 2016; 19 :853–862. doi: 10.1111/desc.12320. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Blijlevens P. Self-reported reactive and regulative temperament in early adolescence: Relations to internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and “Big Three” personality factors. Journal of Adolescence. 2007; 30 :1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.03.003. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Hayden EP, Buckley ME. The structure of extraversion in preschool aged children. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005; 39 :481–492. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Overton WF. Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2015. Processes, Relations, and Relational-Developmental-Systems. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parker JS, Benson MJ. Parent-adolescent relations and adolescent functioning: Self-esteem, substance abuse, and delinquency. Adolescence. 2004; 39 (155):519–30. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paulussen-Hoogeboom MC, Stams GJJM, Hermanns JMA, Peetsma TTD. Child negative emotionality and parenting from infancy to preschool: A meta-analytic review. Developmental Psychology. 2007; 43 (2):438. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.438. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Hastings PD. Emotion development from an experimental and individual differences lens. In: Wixted JT, editor. The Stevens’ Handbook of Experimental Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience. Fourth. Vol. 4. New York: Wiley; 2018. pp. 289–321. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Schmidt LA, Henderson HA, Schulkin J, Fox NA. Salivary cortisol levels and infant temperament shape developmental trajectories in boys at risk for behavioral maladjustment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008; 33 :916–925. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Poole KL, Tang A, Schmidt LA. The temperamentally shy child as the social adult: An exemplar of multifinality. In: Pérez-Edgar K, Fox NA, editors. Behavioral Inhibition: Integrating Theory, Research, and Clinical Perspectives. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; (in press) [ Google Scholar ]

- Rabinowitz JA, Drabick DAG. Do children fare for better and for worse? Associations among child features and parenting with child competence and symptoms. Developmental Review. 2017; 45 :1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2017.03.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Raby KL, Roisman GI, Fraley RC, Simpson JA. The enduring predictive significance of early maternal sensitivity: Social and academic competence through age 32 years. Child Development. 2015; 86 :695–708. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12325. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reitz AK, Zimmermann J, Hutteman R, Specht J, Neyer FJ. How peers make a difference: The role of peer groups and peer relationships in personality development. European Journal of Personality. 2014; 28 :279–288. doi: 10.1002/per.1965. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reuben JD, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D, Leve LD. Warm parenting and effortful control in toddlerhood: independent and interactive predictors of school-age externalizing behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2016; 44 :1083–1096. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0096-6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosa EM, Tudge J. Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Theory of Human Development: Its evolution from ecology to bioecology. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2013; 5 :243–258. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12022. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roth TL. Epigenetics of neurobiology and behavior during development and adulthood. Developmental Psychobiology. 2012; 54 :590–597. doi: 10.1002/dev.20550. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothbart MK. Becoming Who We Are: Temperament and Personality in Development. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Advances in temperament: History, concepts, and measures. In: Zentner M, Shiner RL, editors. Handbook of Temperament. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 3–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothbart MK, Derryberry D. Development of individual differences in temperament. In: Lamb ME, Brown AL, editors. Advances in Developmental Psychology. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 37–86. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothbart MK, Ellis LK, Rosario Rueda M, Posner MI. Developing mechanisms of temperamental effortful control. Journal of Personality. 2003; 71 :1113–1144. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106009. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothbart MK, Posner MI, Kieras J. Temperament, attention, and the development of self-regulation. In: McCartney K, Phillips D, editors. Blackwell Handbook of Early Childhood Development. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2006. pp. 338–357. [ Google Scholar ]