Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Our Morality: A Defense of Moral Objectivism

After our recent ‘death of morality’ issue, mitchell silver replies to the amoralists..

Philosophers who aspire to describe reality without resort to myth, too often remain in thrall to the myth of absolute neutrality. Myths are not without their proper uses, and belief in absolute neutrality can be a useful, even an indispensable premise in the practices of science, jurisprudence, sports refereeing, and a host of other activities in which we want to discourage corrupting biases. Still, absolute neutrality is a myth, one memorably formulated by Thomas Nagel as ‘the view from nowhere’. There is no ‘view from nowhere’, and any philosophical practice which pretends to occupy that mythical perspective sows confusion.

In this article I will describe and defend my kind of moral viewpoint (not my specific viewpoint). The label I will use for this kind of viewpoint is ‘moral objectivism’, because this creates a stark contrast with ‘moral subjectivism’ and ‘moral relativism’ – the views that no coherent morality is better than any other coherent morality, which along with ‘moral nihilism’ – the denial of any morality – present the most philosophically popular moral perspectives that are not of my kind.

Moral objectivism, as I use the term, is the view that a single set of principles determines the permissibility of any action, and the correctness of any judgment regarding an action’s permissibility . Does this view deserve the label ‘moral objectivism?’ I think it does. Although it doesn’t claim that moral principles exist independent of the people who hold them, or that moral properties such as justice exist independently of moral principles, it forthrightly states that some actions are right and some are wrong, regardless of the judgments others may make about them. In making that claim, I am in conflict with the relativists and nihilists, both of whom assert that moral objectivism is poorly grounded compared to alternative metaethics. (A metaethic is a view about the nature of morality. It is not a particular moral view.) These philosophers maintain that moral objectivism requires that we can only validate an action’s moral status or a judgment’s moral correctness by resorting to some beyond-human authority – some moral reality external to people which serves as the source of whatever set of principles a moral objectivist believes determines moral values and correctness. These relativists and nihilists claim that objectivism needs something like God, but they disbelieve there is anything like God, so they conclude that moral objectivism requires something which does not exist.

I share the relativist/nihilist rejection of any form of supernaturalism. I do not believe in God, or in any other external authority that grounds moral objectivism. Indeed, I do not think morality can be grounded in any external source. Yet I am a moral objectivist, and I think there is a good chance you are too. In what follows I do not defend the content of my moral beliefs, nor make any presumptions about the content of yours. I do, however presume that many of you take the content your moral beliefs as seriously as I do mine. I will seek to persuade you that moral o bjectivism is at least as rational, as well-grounded, and as consistent with reality, as any alternative metaethic. The fundamental error of relativist and nihilist arguments against objectivism is the implicit claim that morality can be judged from nowhere.

Categorical Permissibility Rules: The Form of Morality

The nature of motivation is the province of psychologists, who study it empirically. However, without stirring from our armchairs, we can safely say that people are sometimes motivated by rules that they have accepted, such as ‘move chess bishops only along the diagonals’, or ‘floss daily’. Acceptance of a rule can, in part, constitute motives for actions.

Not only can rules motivate actions, they also influence judgments about the correctness of actions. The rule about chess bishops underlies my judgment that it is incorrect to move a bishop along the horizontal. While there are no precise criteria for whether or not a person has accepted a rule, or for measuring the degree of acceptance, ‘acceptance’ implies that the rule has some motivational force and influence on judgments. It would be nonsensical to say, “Silver accepts the rule forbidding moving bishops horizontally, although he is not in the least inclined to follow the rule, nor does he see anything at all incorrect about moving bishops horizontally.”

Among the rules that can motivate actions and determine judgments are those that classify all possible actions as either permissible or impermissible. I call such rules ‘categorical permissibility rules’ (henceforth, simply ‘permissibility rules’). Common examples of permissibility rules include: it is always impermissible to act in a way that will not increase overall happiness or reduce overall suffering (John Stuart Mill promoted that one); it is always impermissible to treat someone merely as a means (a favorite of Immanuel Kant’s); never do to others that which is hateful to you (the Talmudic version of a commonplace in religious ethics); always obey whatever the priest tells you God has commanded (another commonplace in religious traditions); and, never act against self-interest (Ayn Rand). Less common, but equally possible permissibility rules include: never run for a bus (Mel Brooks); and, never act against Mitchell Silver’s interests (no one, alas). There are an endless number of possible permissibility rules.

If you accept, or stand ready to accept either implicitly or explicitly, a set of permissibility rules as determining the correctness of all possible actions, then you are a moral objectivist. Someone who accepts, say, the permissibility rule ‘everyone should pursue wealth above all else’ and judges all people and actions accordingly, relates to that rule as moral people relate to morality. It has the form of a moral rule, and anyone who accepts it is a moral objectivist, for she accepts a specific permissibility rule. For any objectivist, the content of her permissibility rules constitutes what she takes to be morality. Someone who accepts t he ‘everyone should pursue wealth above all else’ rule thereby takes the pursuit of wealth to be the essence of morality. I do not accept that rule, so I judge it a mistake to believe that it has moral authority. I judge those who accept that rule to be in moral error; but still, they are, like me, moral objectivists.

Of course, you don’t have to know you are an objectivist to be one. Perhaps you simply have never indulged in metaethics, or perhaps you are self-deceived, or lack self-knowledge, and do not realize that you accept a specific set of permissibility rules.

Clearly, many people do accept categorical permissibility rules, including me, maybe you, and very likely your mother. Permissibility rules exist, and anyone who has genuinely accepted a specific set of them must thus judge that morality exists. Moreover, the acceptance of permissibility rules (and thus morality) is a natural phenomenon. There is nothing mysterious or spooky about the rules, their acceptance by people, or about the motivational forces they produce. Accepting a permissibility rule is compatible with all of the following: understanding the scientific explanations of the causes of one’s acceptance; believing that you do not understand all of the implications of the rule you have accepted; believing that you could come to reform or abandon the rule you currently accept; failing sometimes, maybe often, and perhaps always, to act in accordance with the rule; and finally, knowing that others adhere to different permissibility rules.

Explaining Morality

The acceptance of permissibility rules has many causes, as does determination of the specific content of the rules. Among the most notable causes of content are other people’s permissibility rules, and other people’s reactions to yours. It’s easier to live with those who agree with you about the rules of permissible behavior. Moreover, we are influenced by what others, such as our parents, promote as the basic rules. In addition, most of us wish to be seen by others as decent members of society, who abide by commonly-accepted permissibility rules (ie, standards). Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) vividly pointed out that we all want to prosper, and we all represent a threat to each other, therefore, as prudent, self-interested animals, we naturally seek enforceable rules to promote prosperity and reduce the mutual threat. Other philosophers have argued that the most acceptable rules likely to emerge from this human condition will enshrine fairness and equality at their center. The social and life sciences have also weighed in: economists have shown how permissibility rules grease commerce, psychologists how they emerge from our emotions, sociologists how they stabilize communities, and evolutionary biologists how they enhance fitness.

The drive to organize our judgments of actions into a logical structure, the urge to rationalize or justify them, is surely one significant explanation of the existence of permissibility rules. Those who value reason and psychic harmony will likely be attracted to rules that justify their gut feelings. If you feel that bull-fighting is wrong, and you like to have reasons for your feelings, you will be open to a rule that implies bull-fighting is wrong. But the causal chain can also go in the opposite direction. An inclination for rational orderliness may cause your moral feelings to align with your current theoretical commitments. Some who have no pre-theoretical moral dislike of bull-fighting may well come to have a moral dislike of it because a rule they accept brands it as wrong. Many a philosopher has become a vegetarian not out of any sympathy for animals, but from a love of consistency and acceptance of a permissibility rule that forbids causing gratuitous suffering.

Justifying Moral Judgments

An explanation provides an account of what something is or how something came about, and in theory anything can be explained; but an explanation is not a justification: a justification gives an account of why something is right, or why it’s right to believe something. Little Mary’s belief that she will receive a Christmas gift is explained by her belief in Santa, but it is justified by her parents’ reliable generosity. Similarly, the above considerations go a long way to explaining the widespread acceptance of certain kinds of permissibility rules, but none of them justifies any permissibility rule. My charitable acts, such as they are, are explained by my upbringing; but if the acts are justified, it is due to a principle that recommends charity, or at least allows it. Only some things, such as beliefs, statements and actions, are candidates for justification. Explanations too are candidates for justification, for an explanation can be right or wrong. Since explanations can be justified, and justifications can be explained, it is easy to conflate the two. Nevertheless, explanation and justification are separate (albeit overlapping) processes, and by itself no amount of explanation ever justifies anything.

The permissibility rules you accept are for you neither justified nor unjustified: they justify. As the sources of moral justification, permissibility rules are similar to the sources of non-moral justification: no adequate reason can be given for accepting or rejecting the sources that does not beg the question. We can justify beliefs; but we can justify the principles we employ to justify beliefs only with circular reasoning. Likewise, we can justify actions, but we cannot without circularity or indefinite regress justify the principles we employ to justify actions. The justification of principles would require a resort to other justifying principles, which would themselves be unjustified. As Hume taught us, the belief that the future will resemble the past is unjustifiable, but we label those who disbelieve the sun will rise tomorrow ‘irrational’. For most of us, inductive reasoning [reasoning from experience, eg of rising suns] is an essential tool for justifying beliefs. It does a fairly good job of justifying beliefs we feel ought to be justified, in spite of the fact that its implications are not always clear or beyond dispute. Moreover, the principle of induction is compatible with the other principles most of us have in our belief-justifying-tool-kit. Of course there are those who reject the entire tool-kit. We call them ‘mad’, or ‘illogical’. Analogously, we call those who truly reject our central permissibility rules ‘monstrous’ or ‘morally obtuse’. For example, without us having justified the underlying moral principle which rationalizes the judgment, we label ‘immoral’ those who disbelieve that genocide is wrong. This is not simple name-calling, it is categorization according to the epistemological and moral principles we accept.

As long as a set of permissibility rules does not require impossible actions (cure cancer, fly to Mars, eat your cake and have it, never die), or posit non-existing entities (the tooth fairy, the Devil, the eternal incorporeal commander), there are no epistemic or practical reasons for rejecting or it, just as there are none for accepting it. Hume famously, and correctly, said that you cannot derive ‘ought’ from ‘is’. It is equally important to note that you cannot derive ‘ought not to accept oughts’ from ‘is’. The rejection of all permissibility rules has no more justification than the acceptance of a specific permissibility rule. The consequences of accepting or rejecting permissibility rules are another matter entirely; but whatever they are, by themselves consequences cannot constitute a justification. Relativists and nihilists sometimes attempt to justify their anti-objectivism by invoking what they assert are the effects of belief in moral objectivism: arrogance, smugness, intolerance, and widespread suffering. I dispute that those are the dominant effects of all objectivisms: a liberal, sensitive, egalitarian consequentialist (a species of objectivist), ever mindful of the fallibility of her judgments, can humbly try to foresee suffering, and minimize it. However, even granting the relativist/ nihilist assessment of the empirical effects of all and any objectivism, without a permissibility principle requiring avoidance of those effects, the relativist/nihilist has provided no grounds for rejecting objectivism. Railing against objectivism for the harms it causes is like protesting that the Constitution is unconstitutional.

To say that a permissibility rule is unjustified is not to say that it is arbitrary, it’s only to say that it is contingent – that, like the historical and personal facts on which it is based, it might have been other than what it is. No permissibility rule is true of necessity. If I wasn’t who I am, I might well have had other permissibility rules, or none. But the fact that our permissibility rules are expressions of who we are makes them the opposite of arbitrary – not accidental attachments to us, but rather organic elements of us. Although we cannot justify them, we can be proud of them, loyal to them, and pleased with their effects. We can note how well they perform certain functions, and we can be pleased that their acceptance violates no norms of knowledge nor requires belief in metaphysical oddities. Still, these feelings and observations do not justify our rules.

Metaethics and Moral Disagreement

Although it brings all possible actions under a single standard, a permissibility rule can be complex, and its application sensitive to circumstances. A permissibility rule may require that the time, place, effects, and the nature of the people involved be considered when evaluating an action. It may even take into account the acceptance of different permissibility rules by other people. (Indeed, objectivity demands the incorporation of information from as many perspectives as possible.) Information about other peoples’ rules should shape a moral perspective, but it doesn’t undermine its validity. For instance, I know that there are people who categorically accept the rule that one should never mistreat their holy scriptures. I accept no such rule, but my awareness of others’ acceptance of the rule, combined with a rule I do accept, that everyone should show respect for others’ feelings, results in me not mistreating others’ holy scriptures. I do not respect the ‘holy scripture rule’ in itself; but I respect the holders of that rule, and in doing so I must often respect their rule. But this derivative respect for their permissibility rules does not mean I accept their rules to make my moral judgments.

Your metaethics depends on whether you genuinely accept a permissibility rule. If you have genuinely accepted specific permissibility rules, in accordance with that acceptance, then you must judge that there are rules which categorize any action’s permissibility, ie, its morality, and you are a moral objectivist. If in addition you accept the same permissibility rules as I do, we agree about the essential substance of morality. Nonetheless, we may yet disagree about the correct classification of a particular action, or kind of action. These disagreements can stem from disputes about concepts (how shall we define ‘pain’?), facts (does an eighteen-week-old fetus feel pain?), or logic (does ‘we ought not perform abortions’ follow from ‘we ought never inflict pain unnecessarily’?). Common acceptance of specific permissibility rules leaves room for differences of particular judgments.

Your specific permissibility rules constitute what you take to be morality, but they are likely to permit inconsistent courses of action: permission is not the same as direction. For example, a rule that implies you should not eat animals allows that the daily consumption of carrots is moral and that the refusal to ever eat carrots is also moral. Indeed that rule permits you to starve yourself to death. You remain a moral objectivist even if the permissibility rule(s) you accept allow you to do almost anything. S ome permissibility rules allow an infinite number of morally permissible acts. The only requirement for your moral objectivist status is that the rules you accept classify some actions as morally out-of-bounds. And objectivism is not totalitarianism: even if you believe there are some things that no one ought to do, you can believe that there are many ways to lead an overall good life, and many situations that permit different courses of action. Hence a moral objectivist can be an ethical pluralist.

There may be people who share your permissibility rules, but also accept additional permissibility rules you do not accept. Maybe, like you, they think it immoral to eat animals, but unlike you, they also believe it is immoral to eat carrots. What are you to make of these people? You must judge that these people misclassify many actions as immoral. You must judge that they have mistaken what are matters of custom, convention, or personal taste, for matters of moral import. You may well judge that two parties, both of whom take themselves to be in serious moral conflict – one says it is immoral to eat carrots, the other that it is immoral not to eat carrots – are both correct that their preferred course of action is morally permissible, and are both incorrect that the other’s preference is morally forbidden . Their passionate belief that they are in moral disagreement does not mean you must, from your perspective, take them to be in moral disagreement.

Your assessment of other people’s morality depends on which specific permissibility rules you genuinely accept. If you really accept as categorical a rule that permits carrot eating, then you must conclude that others are simply morally incorrect to judge carrot eating immoral. You are not doubting the sincerity of their judgment; but acknowledging their sincerity is not the same as acknowledging their correctness.

Now if your permissibility rules conflict with the rules I accept, we are both objectivists, but we’re in fundamental moral conflict. To remain true to my acceptance of rules that allow but do not demand carrot eating, I must conclude that you are mistaken to think eating carrots is immoral. True to your different permissibility rules, you must judge my moral indifference to carrot consumption morally incorrect. Anyone tempted to take a perspective above the fray will either have permissibility rules from which she can judge which of us is correct (if either), or she has not accepted any permissibility rules. If she has accepted permissibility rules, they will either allow or disallow carrot eating. She is an objectivist, just like us, and can weigh in on our dispute. If she accepts no permissibility rules whatsoever, the very idea of moral permissibility has no claim on her, and she has nothing relevant to offer those of us who do feel the pull of permissibility rules. She is not an objectivist, and both you and I (albeit by virtue of different rules) must conclude that she is without morals. Hardly someone we should ask to arbitrate our moral dispute over carrot eating.

Relativists, Nihilists, Amoralists and Objectivists

If you, dear reader, claim in perfectly good faith not to accept any permissibility rules, then I could in haste judge that you are without morals. But not to worry; I believe that your moral nihilism is probably only a theoretical posture, inconsistent with your actual acceptance of permissibility rules, as reflected in your actual judgments of particular actions. Although your acceptance of permissibility rules implies that you accept that those rules are applicable to all actions and judgments, including your own theoretical judgments , your permissibility rules may allow you (as mine do me) to temporarily pretend that you do not accept them, in order to see what might in theory follow from their non-acceptance. But temporarily playing the amoralist in order to try and imagine how the world looks from that perspective, is not genuine amorality.

The assertion of a robust moral relativism means adopting a perspective from which all permissibility rules are viewed as equally valid. It is important (and often difficult) to keep in mind that moral relativism is not the descriptive claim that people have different and conflicting moral judgments; rather it is the normative claim that no moral judgment is more or less correct than any other. To become a sincere moral relativist one must abandon one’s permissibility rules without embracing other permissibility rules. A relativist could consistently act in accordance with any permissibility rule, but she cannot consistently believe there are any justifications for these actions.

If you sincerely and fully, even if only in theory, accept, say, a rule that it’s immoral to torture people, a rule that it’s immoral not to torture people, and another rule that torture is morally indifferent, then you’ve taken an incoherent theoretical position that’s equivalent to the denial of morality – moral nihilism. The other way to go, the non-acceptance of all permissibility rules, is not the mythical stance of neutrality, it is the particular viewpoint of amorality . It is not the discovery that no rules apply to all possible actions; it is a failure to apply any such rules. It is not an undistorted perspective which reveals morality’s non-existence: it is simply an amoral perspective. This is not how I see things, and I suspect it is not how you see things. I am, and you probably are, a moral objectivist.

Moral objectivism requires only the acceptance of a set of permissibility rules. This involves no metaphysical delusions. Your permissibility rules may be tolerant, liberal, modest, tentative and undogmatic, or the opposite. So long as they’re truly yours, you are a moral objectivist. So are you?

© Mitchell Silver 2011

Mitchell Silver is a Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Massachusetts/Boston and the author of books on secular religious identity and secular understandings of theology. He is currently writing a book on moral objectivism.

This site uses cookies to recognize users and allow us to analyse site usage. By continuing to browse the site with cookies enabled in your browser, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy . X

Moral Objectivism

By michael huemer, 1. what is the issue, 1.1. "objectivism" and "relativism", 1.2. what is 'morality', 1.3. "values are subjective" = "all values are subjective", 1.4. three ways of being non-'objective', 1.5. several relativist theories, 1.6. what the issue is not, 2. the consequences of relativism, 3. arguments for subjectivism, 3.1. cultural variance of moral codes.

[I]t is the mark of an educated man to look for precision in each discipline just so far as the nature of the subject admits; it is evidently equally foolish to accept probable reasoning from a mathematician and to demand from a rhetorician scientific proofs. (2)

3.2. Simplicity

If anything, we should say that the burden of proof is on the moral relativist, for advancing a claim contrary to common sense.

3.3. Where does moral knowledge come from?

3.4. the political argument, 4. several versions of relativism refuted, 4.1. value judgements as universally false, 4.2. moral judgements as expressions of sentiment.

I can return this book to the library. I borrowed this book from the library. This book exists. I have not returned this book to the library. etc.

4.3. "x is good" as synonymous with "I like x"

4.4. "x is good" as a synonym for "x is ordained by my society", 4.5. moral judgements as projection, 4.6. morals as a matter of convention, 4.7. the argument generalized.

For all of these reasons, I conclude that relativism is both pernicious and logically untenable.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.1: Moral Philosophy – Concepts and Distinctions

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 86935

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Before examining some standard theories of morality, it is important to understand basic terms and concepts that belong to the specialized language of ethical studies. The concepts and distinctions presented in this section will be useful for characterizing the major theories of right and wrong we will study in subsequent sections of this unit. The general area of concepts and foundations of ethics explained here is referred to as meta-ethics .

5.1.1 The Language of Ethics

Ethics is about values, what is right and wrong, or better or worse. Ethics makes claims, or judgments, that establish values. Evaluative claims are referred to as normative, or prescriptive, claims . Normative claims tell us, or affirm, what ought to be the case. Prescriptive claims need to be seen in contrast with descriptive claims , which simply tell us, or affirm, what is the case, or at least what is believed to be the case.

For example, this claim is descriptive:, it describes what is the case:

“Low sugar consumption reduces risk of diabetes and heart failure.”

On the other hand, this claim is normative:

“Everyone ought to reduce consumption of sugar.”

This distinction between descriptive and normative (prescriptive) claims applies in everyday discourse in which we all engage. In ethics, however, normative claims have essential significance. A normative claim may, depending upon other considerations, be taken to be a “moral fact.”

Note: Many philosophers agree that the truth of an “is” statement in itself does not infer an “ought” claim. The fact the low sugar consumption leads to better health does not imply, on its own, that everyone should reduce their sugar intake. A good logical argument would require further reasons (premises) to reach the “ought” conclusion/claim. An “ought” claim inferred directly from an “is” statement is referred to as the naturalistic fallacy .

A supplemental resource is available (bottom of page) on the distinction between descriptive and normative claims.

5.1.2 How Are Moral Facts Real?

When we talk about “moral facts” typically we are referring to claims about values, duties, standards for behavior, and other evaluative prescriptions. The following concepts describe the sense in which moral facts are real in terms of:

- the degree of universality, or lack thereof, with which the moral claims are held, and

- the extent to which moral facts stand independently of other considerations.

Moral Objectivism

The view that moral facts exist, in the sense that they hold for everyone, is called moral (or ethical) objectivism. From the viewpoint of objectivism, moral facts do not merely represent the beliefs of the person making the claim, they are facts of the world. Furthermore, such moral facts/claims have no dependencies on other claims nor do they have any other contingencies.

Moral Subjectivism

Moral (or ethical) subjectivism holds that moral facts are not universal, they exist only in the sense that those who hold them believe them to exist. Such moral facts sometimes serve as useful devices to support practical purposes. According to the viewpoint of subjectivism, moral facts (values, duties, and so forth) are entirely dependent on the beliefs of those who hold them.

Moral Absolutism

Moral absolutism is an objectivist view that there is only one true moral system with specific moral rules (or facts) that always apply, can never be disregarded. At least some rules apply universally, transcending time, culture. and personal belief. Actions of a specific sort are always right (or wrong) independently of any further considerations, including their consequences.

Moral Relativism

Moral relativism is the view that there are no universal standards of moral value, that moral facts, values, and beliefs are relative to individuals or societies that hold them. The rightness of an action depends on the attitude taken toward it by the society or culture of the person doing the action.

- Moral relativism as it relates to an individual is a form of ethical subjectivism.

- As it relates to a society or culture, moral relativism is referred to as “cultural relativism” and is also subjectivist in that moral facts depend entirely on the beliefs of those who hold them, they are not universal.

Note that some accounts of meta-ethical concepts do not use both “objectivism” and “absolutism” or use them interchangeably. The important relationship to keep in mind is that both objectivism and absolutism stand in contrast to relativism and subjectivism.

Here are several arguments in support of moral relativism. The “objection” following each one is an argument against moral relativism and in favor of moral objectivism.

- Objection: “Is” does not imply “ought.” Further, the fact that there are diverse cultural values does not necessarily imply that there are no objective values.

- Objection: That we cannot yet justify objective values does not mean that such a foundation could not be developed.

- Objection: This entails that we tolerate oppressive systems that are intolerant themselves. Further, this argument seems to confer objective value on “tolerance” and further still, “tolerance” is not the same as “respect.”

Here are some additional arguments against moral relativism:

- If values for right and wrong are relative to a specific moral standpoint or culture, anything can be justified, even practices that seem objectively unconscionable.

- Ethical relativism would diminish our possibility for making moral judgments of others and other societies. However, we do make moral judgments of others and believe we are justified in making these moral judgments.

- Ethical relativism says that moral values are determined by ‘the group’, but it is difficult to determine who ‘the group’ is. Anyone in the “group” who disagrees is immoral.

- If people were ethical relativists in practice (that is, if everyone was a ethical subjectivist), there would be moral chaos.

A supplemental resource is available (bottom of page) on moral relativism.

Do you think that there are objective moral values? Or do you believe that all moral values are relative to either cultures or individuals? Include your reasons.

Note: Submit your response to the appropriate Assignments folder.

5.1.3 How Do We Know What is Right?

The question at hand is about moral epistemology. How do we know what is right or wrong? What prompts our moral sentiments, our values, our actions? Are our moral assessments made on a purely rational basis, or do they stem from our emotional nature? There are contemporary philosophers who support each position, but we will return to some “old” friends we met in our unit on epistemology, Immanuel Kant and David Hume. They were hardly on the “same page” when it came to how and if we can know anything at all, and it’s hardly surprising that we find them at odds on what motivates moral choices, how we know what is right.

When we met Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) in our study of epistemology, we read passages from his Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysic (1783). In that work, he applied a slightly less intricate and perplexing presentation of topics from his masterwork on metaphysics and epistemology, the Critique of Pure Reason (1781). His next project involved application of his same rigorous reasoning method to moral philosophy. In 1785, Kant published Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals; it introduced concepts that he expanded subsequently in the Critique of Practical Reason (1788). The short excerpts that follow are from Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals.

Recall that Kant’s epistemology required both reason and empirical experience, each in its proper role. Kant believed that human action could be evaluated only by the logical distinctions based in synthetic a priori judgments.

In the following excerpt, Kant explains that a clear understanding of the moral law is not to be found in the empirical world but is a matter of pure reason.

Everyone must admit that if a law is to have moral force, i.e., to be the basis of an obligation, it must carry with it absolute necessity; that, for example, the precept, “Thou shalt not lie,” is not valid for men alone, as if other rational beings had no need to observe it; and so with all the other moral laws properly so called; that, therefore, the basis of obligation must not be sought in the nature of man, or in the circumstances in the world in which he is placed, but a priori simply in the conception of pure reason; and although any other precept which is founded on principles of mere experience may be in certain respects universal, yet in as far as it rests even in the least degree on an empirical basis, perhaps only as to a motive, such a precept, while it may be a practical rule, can never be called a moral law. Thus not only are moral laws with their principles essentially distinguished from every other kind of practical knowledge in which there is anything empirical, but all moral philosophy rests wholly on its pure part.

However, there is some correspondence between the study of natural world and of ethics. Both have an empirical dimension as well as a rational one. When Kant speaks of “anthropology” he refers to the empirical study of human nature.

…there arises the idea of a twofold metaphysic- a metaphysic of nature and a metaphysic of morals. Physics will thus have an empirical and also a rational part. It is the same with Ethics; but here the empirical part might have the special name of practical anthropology, the name morality being appropriated to the rational part.

So, while the nature of moral duty must be sought a priori “in the conception of pure reason,” empirical knowledge of human nature has a supporting role in distinguishing how to apply moral laws and in dealing with “so many inclinations” – the confusing array of emotions, impulses, desires that bombard us and contradict the command of reason. Our emotions (inclinations) are hardly the source of moral knowledge; they interfere with the human capability for practical pure reason.

Thus not only are moral laws with their principles essentially distinguished from every other kind of practical knowledge in which there is anything empirical, but all moral philosophy rests wholly on its pure part.When applied to man, it does not borrow the least thing from the knowledge of man himself (anthropology), but gives laws a priori to him as a rational being. No doubt these laws require a judgment sharpened by experience, in order on the one hand to distinguish in what cases they are applicable, and on the other to procure for them access to the will of the man and effectual influence on conduct; since man is acted on by so many inclinations that, though capable of the idea of a practical pure reason, he is not so easily able to make it effective in concreto in his life.

Kant sees his project on moral law, or “practical reason,” to be a less complicated project than Critique of Pure Reason, his “critical examination of the pure speculative reason, already published.” According to Kant, “moral reasoning can easily be brought to a high degree of correctness and completeness”, whereas speculative reason is “dialectical” – laden with opposing forces. Furthermore, a complete “critique” of practical reason entails “a common principle” that can cover any situation – “for it can ultimately be only one and the same reason which has to be distinguished merely in its application.”

Intending to publish hereafter a metaphysic of morals, I issue in the first instance these fundamental principles. Indeed there is properly no other foundation for it than the critical examination of a pure practical reason; just as that of metaphysics is the critical examination of the pure speculative reason, already published. But in the first place the former is not so absolutely necessary as the latter, because in moral concerns human reason can easily be brought to a high degree of correctness and completeness, even in the commonest understanding, while on the contrary in its theoretic but pure use it is wholly dialectical; and in the second place if the critique of a pure practical Reason is to be complete, it must be possible at the same time to show its identity with the speculative reason in a common principle, for it can ultimately be only one and the same reason which has to be distinguished merely in its application.

In the next section of this unit, we will see where Kant goes with this project and its “common principle” the applies universally. For now, keep in mind that Kant sees moral judgment as a reason-based activity, and that emotions/inclinations diminish our moral judgments. Many philosophers agree that making moral judgments and taking moral actions are rationally contemplated undertakings.

David Hume (1711-1776) , as we learned in our epistemology unit, doubted that the principles of cause and effect and that induction could lead to truth about the natural world. Recall his picture of reason, his version of the distinction between a prior and a posteriori knowledge:

- Relations of ideas are beliefs grounded wholly on associations formed within the mind; they are capable of demonstration because they have no external referent.

- Matters of fact are beliefs that claim to report the nature of existing things; they are always contingent.

In both his Treatise of Human Nature (1739) and An Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals (1751) relations-of-ideas and matters-of-fact figure in his position that human agency and moral obligation are best considered as functions of human passions rather than as the dictates of reason. The excerpts that follow are from the Treatise (Book III, Part I, Sections I and II).

If reason were the source of moral sensibility, then either relations of ideas or matters-of-fact would need to be involved:

As the operations of human understanding divide themselves into two kinds, the comparing of ideas, and the inferring of matter of fact; were virtue discovered by the understanding; it must be an object of one of these operations, nor is there any third operation of the understanding. which can discover it.

Relations of ideas involve precision and certainty (as with geometry or algebra) that arise out of pure conceptual thought and logical operations. A relationship between “vice and virtue” cannot be demonstrated in this way.

There has been an opinion very industriously propagated by certain philosophers, that morality is susceptible of demonstration; and though no one has ever been able to advance a single step in those demonstrations; yet it is taken for granted, that this science may be brought to an equal certainty with geometry or algebra. Upon this supposition vice and virtue must consist in some relations; since it is allowed on all hands, that no matter of fact is capable of being demonstrated….. For as you make the very essence of morality to lie in the relations, and as there is no one of these relations but what is applicable… RESEMBLANCE, CONTRARIETY, DEGREES IN QUALITY, and PROPORTIONS IN QUANTITY AND NUMBER; all these relations belong as properly to matter, as to our actions, passions, and volitions. It is unquestionable, therefore, that morality lies not in any of these relations, nor the sense of it in their discovery.

Hume goes on to explain how moral distinctions do not arise from of matters of fact:

Take any action allowed to be vicious: Willful murder, for instance. Examine it in all lights, and see if you can find that matter of fact, or real existence, which you call vice. In which-ever way you take it, you find only certain passions, motives, volitions and thoughts. There is no other matter of fact in the case. The vice entirely escapes you, as long as you consider the object. You never can find it, till you turn your reflection into your own breast, and find a sentiment of disapprobation, which arises in you, towards this action. Here is a matter of fact; but it is the object of feeling, not of reason. It lies in yourself, not in the object.

And so, Hume concludes that moral distinctions are not derived from reason, rather they come from our feelings, or sentiments.

Thus the course of the argument leads us to conclude, that since vice and virtue are not discoverable merely by reason, or the comparison of ideas, it must be by means of some impression or sentiment they occasion, that we are able to mark the difference betwixt them……Morality, therefore, is more properly felt than judged of”

Hume’s view that our moral judgments and actions arise not from our rational capacities but from our emotional nature and sentiments, is contrary to several of the major normative theories we will explore. However, it is interesting to note that some present-day philosophers regard the domain of emotion as a primary source of moral action, and also that work in neuroscience suggests that Hume may have been on the right track.

Economist Jeremy Rifkin provides an absorbing and fast-moving chalk-talk on human empathy, as demonstrated by neuroscience. (10+ minutes) Note: Cartoon depictions of humans are unclothed RSA Animate . [CC-BY-NC-ND]

Optional Video

Trust, morality – and oxytocin? . [CC-BY-NC-ND] Neuro-economist Paul Zak believe he has identified the “moral molecule” in the brain. (16+ minutes)

An additional supplemental video (bottom of page) explores moral judgments and neuroscience even further.

What do you think about the connection between morality and the neurobiology of our brains? Do you think these findings affect arguments for or against ethical relativism?

Note: Post your response in the appropriate Discussion topic.

5.1.4 Psychological Influences

Various psychological characterizations of human nature have had significant influence on views about morality. We will see in this Ethics unit and the next on Social and Political Philosophy that particular conceptions of human nature may be at the center of theories about moral actions of individuals and about ethical interaction among individuals in social communities.

Egoism is the view that by nature we are selfish, that our actions, even our ostensibly generous ones, are motivated by selfish desire. Ethical egoism is the belief that pursuing ones own happiness is the highest moral value, that moral decisions should be guided by self-interest.

Another view of human nature holds that the primary motivation for all of our actions is pleasure. Hedonism is the view that pleasure is the highest or only good worth seeking, that we should, in fact, seek pleasure.

A different take on human nature is that we have innate capacity for benevolence (empathy) toward other people. (Recall the the mirror neurons in the Jeremy Rifkin video.) Altruism is the view that moral decisions should be guided by consideration for the interests and well-being of other people rather than by self-interest.

5.1.5 The Meaning of “Good”

In Ethics, we refer to what is “good” as a general term of approval, for what is of value, for example, a particular action, a quality, a practice, a way of life. Among the aspects of “good” that philosophers discuss is whether a particular thing is valued because it is good in and of itself, or because it leads to some other “good.”

- An intrinsic good is something that is good in and of itself, not because of something else that may result from it. In ethics, a “value” possesses intrinsic worth. For example, with hedonism, pleasure is the only intrinsic good, or value. In some normative theories, a particular type of action may possess intrinsic worth, or good.

- An instrumental good , on the other hand, is useful for attaining something else that is good. It is instrumental in that it that leads to another good, but it is not good is and of itself. For example, for an egoist, an action such as generosity to others can be seen as an instrumental good if it leads to to self-fulfillment, which is an intrinsic good valued in and of itself by an egoist.

As we look more closely at some major normative theories, the distinction between intrinsic and instrumental good will be among the considerations of interest. Understanding normative theories, also involves these questions:

- How do we determine what the right action is?

- What are the standards that we use to judge if a particular action is good or bad?

The following normative theories will be addressed:

- Deontology (from the Greek for “obligation, or duty”) is concerned rules and motives for actions.

- Utilitarianism, a consequentialist theory, is interested in the good outcomes of actions.

- Virtue Ethics values actions in terms of what a person of good character would do.

Supplemental Resources

Descriptive and Normative Claims

Fundamentals: Normative and Descriptive Claims . This 4-minute video is a quick review with examples, on the differences between descriptive and normative claims.

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP). Moral Relativism . Read section “3. Arguments for Moral Relativism” and section “4. Objections to Moral Relativism.”

Moral Judgment and Neuroscience

The Neuroscience behind Moral Judgments . Alan Alda talks with an MIT neuroscientist about neurological connections with moral judgments. (5+ minutes)

- 5.1 Moral Philosophy - Concepts and Distinctions. Authored by : Kathy Eldred. Provided by : Pima Community College. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Works & Talks

- Newsletter Sign Up

The Objectivist Ethics

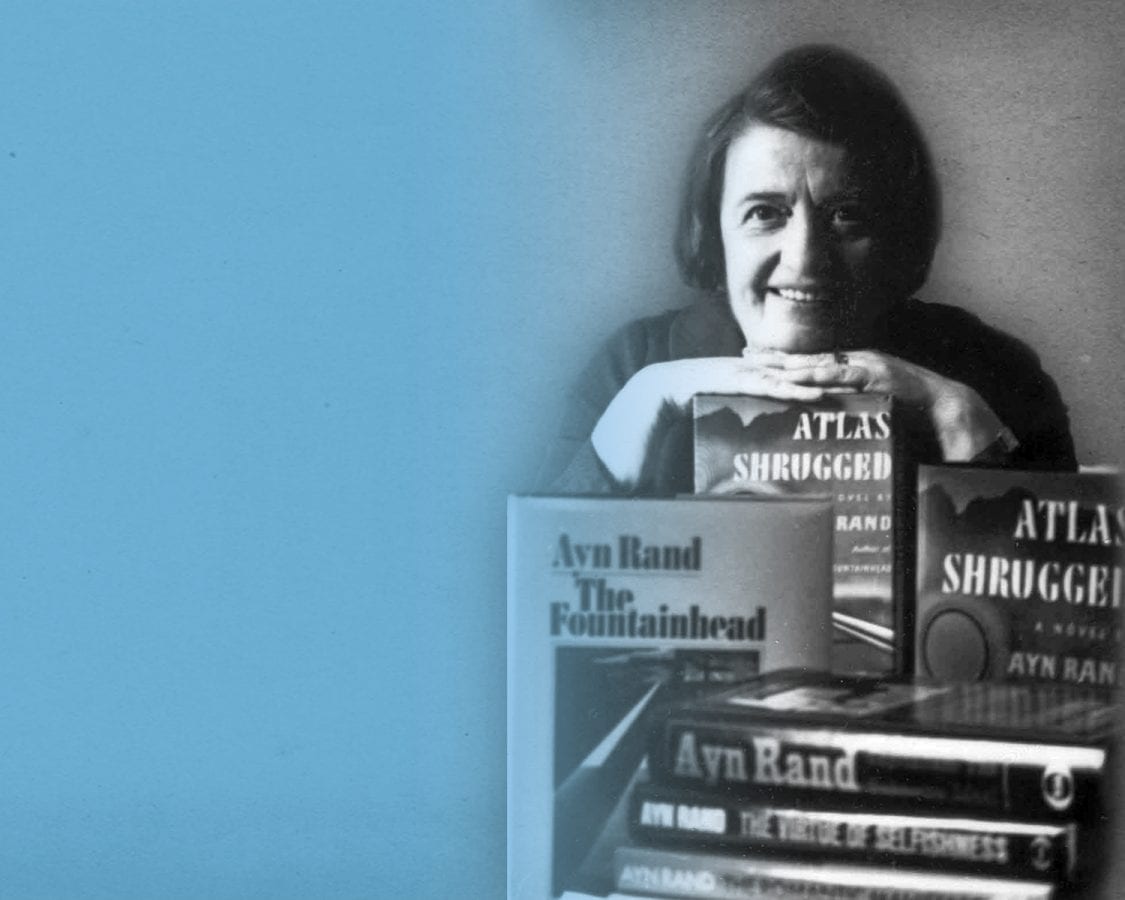

Based on a lecture delivered in February 1961 at the University of Wisconsin, this essay was first published in The Virtue of Selfishness (1964). Rand also delivered a version on radio and, in a separate radio program, answered questions on the subject. The radio address lasts 56 minutes and the Q&A lasts 36 minutes.

Since I am to speak on the Objectivist Ethics, I shall begin by quoting its best representative — John Galt, in Atlas Shrugged :

“Through centuries of scourges and disasters, brought about by your code of morality, you have cried that your code had been broken, that the scourges were punishment for breaking it, that men were too weak and too selfish to spill all the blood it required. You damned man, you damned existence, you damned this earth, but never dared to question your code. . . . You went on crying that your code was noble, but human nature was not good enough to practice it. And no one rose to ask the question: Good? — by what standard?

“You wanted to know John Galt’s identity. I am the man who has asked that question.

“Yes, this is an age of moral crisis. . . . Your moral code has reached its climax, the blind alley at the end of its course. And if you wish to go on living, what you now need is not to return to morality . . . but to discover it.”

What is morality, or ethics? It is a code of values to guide man’s choices and actions — the choices and actions that determine the purpose and the course of his life. Ethics, as a science, deals with discovering and defining such a code.

The first question that has to be answered, as a precondition of any attempt to define, to judge or to accept any specific system of ethics, is: Why does man need a code of values?

Let me stress this. The first question is not: What particular code of values should man accept? The first question is: Does man need values at all — and why?

Is the concept of value , of “good or evil” an arbitrary human invention, unrelated to, underived from and unsupported by any facts of reality — or is it based on a metaphysical fact, on an unalterable condition of man’s existence? (I use the word “metaphysical” to mean: that which pertains to reality, to the nature of things, to existence.) Does an arbitrary human convention, a mere custom, decree that man must guide his actions by a set of principles — or is there a fact of reality that demands it? Is ethics the province of whims : of personal emotions, social edicts and mystic revelations — or is it the province of reason ? Is ethics a subjective luxury — or an objective necessity?

In the sorry record of the history of mankind’s ethics — with a few rare, and unsuccessful, exceptions — moralists have regarded ethics as the province of whims, that is: of the irrational. Some of them did so explicitly, by intention — others implicitly, by default. A “whim” is a desire experienced by a person who does not know and does not care to discover its cause.

No philosopher has given a rational, objectively demonstrable, scientific answer to the question of why man needs a code of values. So long as that question remained unanswered, no rational, scientific, objective code of ethics could be discovered or defined. The greatest of all philosophers, Aristotle, did not regard ethics as an exact science; he based his ethical system on observations of what the noble and wise men of his time chose to do, leaving unanswered the questions of: why they chose to do it and why he evaluated them as noble and wise.

Most philosophers took the existence of ethics for granted, as the given, as a historical fact, and were not concerned with discovering its metaphysical cause or objective validation. Many of them attempted to break the traditional monopoly of mysticism in the field of ethics and, allegedly, to define a rational, scientific, nonreligious morality. But their attempts consisted of trying to justify them on social grounds, merely substituting society for God .

The avowed mystics held the arbitrary, unaccountable “will of God” as the standard of the good and as the validation of their ethics. The neomystics replaced it with “the good of society,” thus collapsing into the circularity of a definition such as “the standard of the good is that which is good for society.” This meant, in logic — and, today, in worldwide practice — that “society” stands above any principles of ethics, since it is the source, standard and criterion of ethics, since “the good” is whatever it wills, whatever it happens to assert as its own welfare and pleasure. This meant that “society” may do anything it pleases, since “the good” is whatever it chooses to do because it chooses to do it. And — since there is no such entity as “society,” since society is only a number of individual men — this meant that some men (the majority or any gang that claims to be its spokesman) are ethically entitled to pursue any whims (or any atrocities) they desire to pursue, while other men are ethically obliged to spend their lives in the service of that gang’s desires.

This could hardly be called rational, yet most philosophers have now decided to declare that reason has failed, that ethics is outside the power of reason, that no rational ethics can ever be defined, and that in the field of ethics — in the choice of his values, of his actions, of his pursuits, of his life’s goals — man must be guided by something other than reason. By what? Faith — instinct — intuition — revelation — feeling — taste — urge — wish — whim . Today, as in the past, most philosophers agree that the ultimate standard of ethics is whim (they call it “arbitrary postulate” or “subjective choice” or “emotional commitment”) — and the battle is only over the question of whose whim: one’s own or society’s or the dictator’s or God’s. Whatever else they may disagree about, today’s moralists agree that ethics is a subjective issue and that the three things barred from its field are: reason — mind — reality.

If you wonder why the world is now collapsing to a lower and ever lower rung of hell, this is the reason.

If you want to save civilization, it is this premise of modern ethics — and of all ethical history — that you must challenge.

To challenge the basic premise of any discipline, one must begin at the beginning. In ethics, one must begin by asking: What are values ? Why does man need them?

“Value” is that which one acts to gain and/or keep. The concept “value” is not a primary; it presupposes an answer to the question: of value to whom and for what ? It presupposes an entity capable of acting to achieve a goal in the face of an alternative. Where no alternative exists, no goals and no values are possible.

I quote from Galt’s speech: “There is only one fundamental alternative in the universe: existence or nonexistence — and it pertains to a single class of entities: to living organisms. The existence of inanimate matter is unconditional, the existence of life is not: it depends on a specific course of action. Matter is indestructible, it changes its forms, but it cannot cease to exist. It is only a living organism that faces a constant alternative: the issue of life or death. Life is a process of self-sustaining and self-generated action. If an organism fails in that action, it dies; its chemical elements remain, but its life goes out of existence. It is only the concept of ‘Life’ that makes the concept of ‘Value’ possible. It is only to a living entity that things can be good or evil.”

To make this point fully clear, try to imagine an immortal, indestructible robot, an entity which moves and acts, but which cannot be affected by anything, which cannot be changed in any respect, which cannot be damaged, injured or destroyed. Such an entity would not be able to have any values; it would have nothing to gain or to lose; it could not regard anything as for or against it, as serving or threatening its welfare, as fulfilling or frustrating its interests. It could have no interests and no goals.

Only a living entity can have goals or can originate them. And it is only a living organism that has the capacity for self-generated, goal-directed action. On the physical level, the functions of all living organisms, from the simplest to the most complex — from the nutritive function in the single cell of an amoeba to the blood circulation in the body of a man — are actions generated by the organism itself and directed to a single goal: the maintenance of the organism’s life . 1 When applied to physical phenomena, such as the automatic functions of an organism, the term “goal-directed” is not to be taken to mean “purposive” (a concept applicable only to the actions of a consciousness) and is not to imply the existence of any teleological principle operating in insentient nature. I use the term “goal-directed,” in this context, to designate the fact that the automatic functions of living organisms are actions whose nature is such that they result in the preservation of an organism’s life.

An organism’s life depends on two factors: the material or fuel which it needs from the outside, from its physical background, and the action of its own body, the action of using that fuel properly . What standard determines what is proper in this context? The standard is the organism’s life, or: that which is required for the organism’s survival.

No choice is open to an organism in this issue: that which is required for its survival is determined by its nature , by the kind of entity it is . Many variations, many forms of adaptation to its background are possible to an organism, including the possibility of existing for a while in a crippled, disabled or diseased condition, but the fundamental alternative of its existence remains the same: if an organism fails in the basic functions required by its nature — if an amoeba’s protoplasm stops assimilating food, or if a man’s heart stops beating — the organism dies. In a fundamental sense, stillness is the antithesis of life. Life can be kept in existence only by a constant process of self-sustaining action. The goal of that action, the ultimate value which, to be kept, must be gained through its every moment, is the organism’s life .

An ultimate value is that final goal or end to which all lesser goals are the means — and it sets the standard by which all lesser goals are evaluated . An organism’s life is its standard of value : that which furthers its life is the good , that which threatens it is the evil .

Without an ultimate goal or end, there can be no lesser goals or means: a series of means going off into an infinite progression toward a nonexistent end is a metaphysical and epistemological impossibility. It is only an ultimate goal, an end in itself , that makes the existence of values possible. Metaphysically, life is the only phenomenon that is an end in itself: a value gained and kept by a constant process of action. Epistemologically, the concept of “value” is genetically dependent upon and derived from the antecedent concept of “life.” To speak of “value” as apart from “life” is worse than a contradiction in terms. “It is only the concept of ‘Life’ that makes the concept of ‘Value’ possible.”

In answer to those philosophers who claim that no relation can be established between ultimate ends or values and the facts of reality, let me stress that the fact that living entities exist and function necessitates the existence of values and of an ultimate value which for any given living entity is its own life. Thus the validation of value judgments is to be achieved by reference to the facts of reality. The fact that a living entity is , determines what it ought to do. So much for the issue of the relation between “ is ” and “ ought .”

Now in what manner does a human being discover the concept of “ value ”? By what means does he first become aware of the issue of “ good or evil ” in its simplest form? By means of the physical sensations of pleasure or pain . Just as sensations are the first step of the development of a human consciousness in the realm of cognition , so they are its first step in the realm of evaluation .

The capacity to experience pleasure or pain is innate in a man’s body; it is part of his nature , part of the kind of entity he is . He has no choice about it, and he has no choice about the standard that determines what will make him experience the physical sensation of pleasure or of pain. What is that standard? His life .

The pleasure-pain mechanism in the body of man — and in the bodies of all the living organisms that possess the faculty of consciousness — serves as an automatic guardian of the organism’s life. The physical sensation of pleasure is a signal indicating that the organism is pursuing the right course of action. The physical sensation of pain is a warning signal of danger, indicating that the organism is pursuing the wrong course of action, that something is impairing the proper function of its body, which requires action to correct it. The best illustration of this can be seen in the rare, freak cases of children who are born without the capacity to experience physical pain; such children do not survive for long; they have no means of discovering what can injure them, no warning signals, and thus a minor cut can develop into a deadly infection, or a major illness can remain undetected until it is too late to fight it.

Consciousness — for those living organisms which possess it — is the basic means of survival.

The simpler organisms, such as plants, can survive by means of their automatic physical functions. The higher organisms, such as animals and man, cannot: their needs are more complex and the range of their actions is wider. The physical functions of their bodies can perform automatically only the task of using fuel, but cannot obtain that fuel. To obtain it, the higher organisms need the faculty of consciousness. A plant can obtain its food from the soil in which it grows. An animal has to hunt for it. Man has to produce it.

A plant has no choice of action; the goals it pursues are automatic and innate, determined by its nature. Nourishment, water, sunlight are the values its nature has set it to seek. Its life is the standard of value directing its actions. There are alternatives in the conditions it encounters in its physical background — such as heat or frost, drought or flood — and there are certain actions which it is able to perform to combat adverse conditions, such as the ability of some plants to grow and crawl from under a rock to reach the sunlight. But whatever the conditions, there is no alternative in a plant’s function: it acts automatically to further its life, it cannot act for its own destruction.

The range of actions required for the survival of the higher organisms is wider: it is proportionate to the range of their consciousness . The lower of the conscious species possess only the faculty of sensation , which is sufficient to direct their actions and provide for their needs. A sensation is produced by the automatic reaction of a sense organ to a stimulus from the outside world; it lasts for the duration of the immediate moment, as long as the stimulus lasts and no longer. Sensations are an automatic response, an automatic form of knowledge, which a consciousness can neither seek nor evade. An organism that possesses only the faculty of sensation is guided by the pleasure-pain mechanism of its body, that is: by an automatic knowledge and an automatic code of values. Its life is the standard of value directing its actions. Within the range of action possible to it, it acts automatically to further its life and cannot act for its own destruction.

The higher organisms possess a much more potent form of consciousness: they possess the faculty of retaining sensations, which is the faculty of perception . A “perception” is a group of sensations automatically retained and integrated by the brain of a living organism, which gives it the ability to be aware, not of single stimuli, but of entities , of things. An animal is guided, not merely by immediate sensations, but by percepts . Its actions are not single, discrete responses to single, separate stimuli, but are directed by an integrated awareness of the perceptual reality confronting it. It is able to grasp the perceptual concretes immediately present and it is able to form automatic perceptual associations, but it can go no further. It is able to learn certain skills to deal with specific situations, such as hunting or hiding, which the parents of the higher animals teach their young. But an animal has no choice in the knowledge and the skills that it acquires; it can only repeat them generation after generation. And an animal has no choice in the standard of value directing its actions: its senses provide it with an automatic code of values, an automatic knowledge of what is good for it or evil, what benefits or endangers its life. An animal has no power to extend its knowledge or to evade it. In situations for which its knowledge is inadequate, it perishes — as, for instance, an animal that stands paralyzed on the track of a railroad in the path of a speeding train. But so long as it lives, an animal acts on its knowledge, with automatic safety and no power of choice: it cannot suspend its own consciousness — it cannot choose not to perceive — it cannot evade its own perceptions — it cannot ignore its own good, it cannot decide to choose the evil and act as its own destroyer.

Man has no automatic code of survival. He has no automatic course of action, no automatic set of values. His senses do not tell him automatically what is good for him or evil, what will benefit his life or endanger it, what goals he should pursue and what means will achieve them, what values his life depends on, what course of action it requires. His own consciousness has to discover the answers to all these questions — but his consciousness will not function automatically . Man, the highest living species on this earth — the being whose consciousness has a limitless capacity for gaining knowledge — man is the only living entity born without any guarantee of remaining conscious at all. Man’s particular distinction from all other living species is the fact that his consciousness is volitional .

Just as the automatic values directing the functions of a plant’s body are sufficient for its survival, but are not sufficient for an animal’s — so the automatic values provided by the sensory-perceptual mechanism of its consciousness are sufficient to guide an animal, but are not sufficient for man. Man’s actions and survival require the guidance of conceptual values derived from conceptual knowledge. But conceptual knowledge cannot be acquired automatically .

A “ concept ” is a mental integration of two or more perceptual concretes, which are isolated by a process of abstraction and united by means of a specific definition. Every word of man’s language, with the exception of proper names, denotes a concept , an abstraction that stands for an unlimited number of concretes of a specific kind. It is by organizing his perceptual material into concepts, and his concepts into wider and still wider concepts that man is able to grasp and retain, to identify and integrate an unlimited amount of knowledge, a knowledge extending beyond the immediate perceptions of any given, immediate moment. Man’s sense organs function automatically; man’s brain integrates his sense data into percepts automatically; but the process of integrating percepts into concepts — the process of abstraction and of concept-formation — is not automatic.

The process of concept-formation does not consist merely of grasping a few simple abstractions, such as “chair,” “table,” “hot,” “cold,” and of learning to speak. It consists of a method of using one’s consciousness, best designated by the term “conceptualizing.” It is not a passive state of registering random impressions. It is an actively sustained process of identifying one’s impressions in conceptual terms, of integrating every event and every observation into a conceptual context, of grasping relationships, differences, similarities in one’s perceptual material and of abstracting them into new concepts, of drawing inferences, of making deductions, of reaching conclusions, of asking new questions and discovering new answers and expanding one’s knowledge into an ever-growing sum. The faculty that directs this process, the faculty that works by means of concepts, is: reason . The process is thinking .

Reason is the faculty that identifies and integrates the material provided by man’s senses. It is a faculty that man has to exercise by choice . Thinking is not an automatic function. In any hour and issue of his life, man is free to think or to evade that effort. Thinking requires a state of full, focused awareness. The act of focusing one’s consciousness is volitional. Man can focus his mind to a full, active, purposefully directed awareness of reality — or he can unfocus it and let himself drift in a semiconscious daze, merely reacting to any chance stimulus of the immediate moment, at the mercy of his undirected sensory-perceptual mechanism and of any random, associational connections it might happen to make.

When man unfocuses his mind, he may be said to be conscious in a subhuman sense of the word, since he experiences sensations and perceptions. But in the sense of the word applicable to man — in the sense of a consciousness which is aware of reality and able to deal with it, a consciousness able to direct the actions and provide for the survival of a human being — an unfocused mind is not conscious.

Psychologically, the choice “to think or not” is the choice “to focus or not.” Existentially, the choice “to focus or not” is the choice “to be conscious or not.” Metaphysically, the choice “to be conscious or not” is the choice of life or death.

Consciousness — for those living organisms which possess it — is the basic means of survival. For man, the basic means of survival is reason . Man cannot survive, as animals do, by the guidance of mere percepts. A sensation of hunger will tell him that he needs food (if he has learned to identify it as “hunger”), but it will not tell him how to obtain his food and it will not tell him what food is good for him or poisonous. He cannot provide for his simplest physical needs without a process of thought. He needs a process of thought to discover how to plant and grow his food or how to make weapons for hunting. His percepts might lead him to a cave, if one is available — but to build the simplest shelter, he needs a process of thought. No percepts and no “instincts” will tell him how to light a fire, how to weave cloth, how to forge tools, how to make a wheel, how to make an airplane, how to perform an appendectomy, how to produce an electric light bulb or an electronic tube or a cyclotron or a box of matches. Yet his life depends on such knowledge — and only a volitional act of his consciousness, a process of thought, can provide it.

But man’s responsibility goes still further: a process of thought is not automatic nor “instinctive” nor involuntary — nor infallible . Man has to initiate it, to sustain it and to bear responsibility for its results. He has to discover how to tell what is true or false and how to correct his own errors; he has to discover how to validate his concepts, his conclusions, his knowledge; he has to discover the rules of thought, the laws of logic , to direct his thinking. Nature gives him no automatic guarantee of the efficacy of his mental effort.

Nothing is given to man on earth except a potential and the material on which to actualize it. The potential is a superlative machine: his consciousness; but it is a machine without a spark plug, a machine of which his own will has to be the spark plug, the self-starter and the driver; he has to discover how to use it and he has to keep it in constant action. The material is the whole of the universe, with no limits set to the knowledge he can acquire and to the enjoyment of life he can achieve. But everything he needs or desires has to be learned, discovered and produced by him — by his own choice, by his own effort, by his own mind.

A being who does not know automatically what is true or false, cannot know automatically what is right or wrong, what is good for him or evil. Yet he needs that knowledge in order to live. He is not exempt from the laws of reality, he is a specific organism of a specific nature that requires specific actions to sustain his life. He cannot achieve his survival by arbitrary means nor by random motions nor by blind urges nor by chance nor by whim. That which his survival requires is set by his nature and is not open to his choice. What is open to his choice is only whether he will discover it or not, whether he will choose the right goals and values or not. He is free to make the wrong choice, but not free to succeed with it. He is free to evade reality, he is free to unfocus his mind and stumble blindly down any road he pleases, but not free to avoid the abyss he refuses to see. Knowledge, for any conscious organism, is the means of survival; to a living consciousness, every “ is ” implies an “ ought .” Man is free to choose not to be conscious, but not free to escape the penalty of unconsciousness: destruction. Man is the only living species that has the power to act as his own destroyer — and that is the way he has acted through most of his history.

What, then, are the right goals for man to pursue? What are the values his survival requires? That is the question to be answered by the science of ethics . And this , ladies and gentlemen, is why man needs a code of ethics.

Now you can assess the meaning of the doctrines which tell you that ethics is the province of the irrational, that reason cannot guide man’s life, that his goals and values should be chosen by vote or by whim — that ethics has nothing to do with reality, with existence, with one’s practical actions and concerns — or that the goal of ethics is beyond the grave, that the dead need ethics, not the living.

Ethics is not a mystic fantasy — nor a social convention — nor a dispensable, subjective luxury, to be switched or discarded in any emergency. Ethics is an objective, metaphysical necessity of man’s survival — not by the grace of the supernatural nor of your neighbors nor of your whims, but by the grace of reality and the nature of life.

I quote from Galt’s speech: “Man has been called a rational being, but rationality is a matter of choice — and the alternative his nature offers him is: rational being or suicidal animal. Man has to be man — by choice; he has to hold his life as a value — by choice; he has to learn to sustain it — by choice; he has to discover the values it requires and practice his virtues — by choice. A code of values accepted by choice is a code of morality.”

The standard of value of the Objectivist ethics — the standard by which one judges what is good or evil — is man’s life , or: that which is required for man’s survival qua man.

Since reason is man’s basic means of survival, that which is proper to the life of a rational being is the good; that which negates, opposes or destroys it is the evil.

Since everything man needs has to be discovered by his own mind and produced by his own effort, the two essentials of the method of survival proper to a rational being are: thinking and productive work.

If some men do not choose to think, but survive by imitating and repeating, like trained animals, the routine of sounds and motions they learned from others, never making an effort to understand their own work, it still remains true that their survival is made possible only by those who did choose to think and to discover the motions they are repeating. The survival of such mental parasites depends on blind chance; their unfocused minds are unable to know whom to imitate, whose motions it is safe to follow. They are the men who march into the abyss, trailing after any destroyer who promises them to assume the responsibility they evade: the responsibility of being conscious.

If some men attempt to survive by means of brute force or fraud, by looting, robbing, cheating or enslaving the men who produce, it still remains true that their survival is made possible only by their victims, only by the men who choose to think and to produce the goods which they, the looters, are seizing. Such looters are parasites incapable of survival, who exist by destroying those who are capable, those who are pursuing a course of action proper to man.