The challenge of change: understanding the role of habits in university students’ self-regulated learning

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Louise David ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1973-4568 1 ,

- Felicitas Biwer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4211-7234 1 ,

- Rik Crutzen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3731-6610 2 &

- Anique de Bruin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5178-0287 1

1850 Accesses

23 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Study habits drive a large portion of how university students study. Some of these habits are not effective in fostering academic achievement. To support students in breaking old, ineffective habits and forming new, effective study habits, an in-depth understanding of what students’ study habits look like and how they are both formed and broken is needed. Therefore, in this study, we explored these aspects among first-year university students in six focus group discussions ( N = 29). Using a thematic analysis approach, we clustered the data in five themes: Goals Matter , Balancing Perceived Efficiency and Effectiveness when Studying , Navigating Student Life: from Structured Routines to Self-Regulation Challenges , the Quest for Effective Habits with Trying to Break Free From the Screen as subtheme, and the Motivation Roller Coaster . Findings suggest that students had different study habits depending on their goals. Students had quite accurate metacognitive knowledge about effective learning strategies for long-term learning, but often used other learning strategies they deemed most efficient in reaching their goals. Students indicated intentions to change, but did not prioritize change as their current habits enabled them to pass exams and change was not perceived as adding value. Fluctuations in motivation and transitioning to a self-regulated life hampered students’ intentions to form new and break old habits. Next to insights into factors affecting students’ behavioral change intentions, the findings suggest the importance of aligning assessment methods with life-long learning and supporting students in their long-term academic goal setting to prioritize study habits which target lasting learning to optimally foster their self-regulated learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

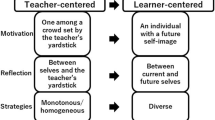

Does changing from a teacher-centered to a learner-centered context promote self-regulated learning: a qualitative study in a Japanese undergraduate setting

Using multiple, contextualized data sources to measure learners’ perceptions of their self-regulated learning

The Science of Habit and Its Implications for Student Learning and Well-being

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In higher education, students are required to plan, monitor, and execute their learning autonomously (Dresel et al., 2015 ; Zimmerman, 1986 ). Therefore, effective self-regulated learning (SRL), facilitated by the use of effective learning strategies, is essential for students’ academic achievement and lifelong learning (e.g., Dunlosky et al., 2013 ). However, many students struggle to use effective learning strategies optimal for long-term learning, such as practice testing, and often rely on passive strategies such as re-reading (Morehead et al., 2016 ; Rea et al., 2022 ). While training programs are successful in increasing students’ knowledge regarding these effective learning strategies, many students struggle to sustainably change their behavior and apply these learning strategies (Biwer et al., 2020a , b ; Foerst et al., 2017 ; Rea et al., 2022 ). This gap between students’ knowledge and behavior is partially due to students’ strong habits of using ineffective study strategies (Blasiman et al., 2017 ; Rea et al., 2022 ). However, so far, this gap between students’ knowledge and behavior and their study habits remained largely unexplored. To explore the gap between students’ knowledge and behavior further, we deem it essential to first gain a thorough understanding of students’ current study habits, how they usually form new, and break old habits.

Using a qualitative approach, we add to the current field of research by targeting an in-depth exploration of students’ study habits, which is currently lacking. Insight into these are essential to tailor educational strategies and training to better align with students' behaviors and needs. Awareness of potential struggles students might encounter when breaking old or forming new habits provides important insights into hurdles students face when attempting to modify their study behavior and how they can be supported in achieving their goals.

Self-regulated learning in higher education

In higher education, learning is happening mostly in teacher-absent environments, which requires students to effectively self-regulate their learning (Dresel et al., 2015 ). However, many students struggle to self-regulate effectively. They monitor and control their learning inaccurately, which has a negative impact on their academic achievement (Hartwig & Dunlosky, 2012 ). One way of fostering self-regulated learning is by helping students to use learning strategies which are optimal for long-term learning (e.g., “desirably difficult” learning strategies, Bjork & Bjork, 2011 ). Examples of desirably difficult learning strategies are practice testing, interleaving items of various categories, and spacing learning sessions over time (Dunlosky et al., 2013 ). A shared commonality of these effective strategies is that they require an active learning process with repeated memory retrieval of information (Bjork & Bjork, 2011 ).

While essential for self-regulated learning, students often avoid desirable difficulties or fail to use them in the long-run, even when being aware of their benefits (Biwer et al., 2020a , b ; Rea et al., 2022 ). One reason for not using effective learning strategies is that students often have strong habits of using surface processing strategies. Instead of using desirable difficulties, students rely on passive learning strategies and mass their study sessions close to the exam instead of spacing the sessions over time (Blasiman et al., 2017 ; Dembo & Seli, 2004 ; Foerst et al., 2017 ). Often students start using these strategies in high school already (Dirkx et al., 2019 ).

Next to struggling to use effective learning strategies, students often face additional regulation issues during their self-study. Learners also need to employ resource management strategies such as effort and motivation management to optimize learning conditions (Dresel et al., 2015 ) by, for example, planning their study sessions or asking for help if necessary. While resource management strategies have been identified as an essential factor for academic performance (Grunschel et al., 2016 ; Waldeyer et al., 2020 ), many students struggle with time management (Basila, 2014 ; Thibodeaux et al., 2017 ) and encounter motivational problems leading to for example procrastination (Grunschel et al., 2016 ).

Metacognition and resource-management strategies are often indicated as important factors in self-regulated learning models (for an overview, see Panadero, 2017 ). However, these factors might not fully explain how students maintain recurring study behaviors over the long term (Fiorella, 2020 ). Instead, habits, which, once formed, are usually not guided by conscious intentions and goals, have been suggested crucial for academic behaviors that need to be repeated consistently over an extended period (Fiorella, 2020 ). Therefore, to foster students’ self-regulated learning, it has been suggested to support students in building new study habits, which, for example, incorporate desirable difficult learning strategies (Fiorella, 2020 ).

Behavioral change and study habits

In the last years, interventions have been developed to enhance students’ knowledge and initial use of effective learning strategies (e.g., Ariel & Karpicke, 2018 ; Biwer et al., 2020b ; Broeren et al., 2021 ). While showing positive effects, the actual transition of this knowledge and application to students’ self-study in the long run remain limited (Dignath & Veenman, 2021 ). The majority of these interventions focus more on increasing students’ knowledge and less on building new habits or changing the actual study behavior consistently potentially explaining the limited application. Habits, however, are an important predictor of behavior in addition to, for example, attitudinal and control beliefs (Verhoeven et al., 2012 ; Verplanken, 2018 ), and are seen as a key factor in behavior maintenance (Rothman et al., 2009 ). To ultimately support students in actually applying effective learning strategies in the long run, it is essential to first understand the factor that drives most behavior: habits (Rothman et al., 2009 ; Verplanken, 2018 ).

Habits are behaviors that reoccur in stable contexts. Once a habit forms, behavior is led by automatic, effortless actions instead of deliberate intentions (Gardner, 2015 ; Lally, et al., 2010 ). According to our conceptualization, study habits can relate to behaviors such as the usual length of a student’s study session, learning strategies used, or study timing and environment. Study habits can play an essential role in harming or helping students to achieve long-term academic goals. Irrespective of whether these habits help or hinder goal achievement, they initiate behavior automatically and effortlessly. Habits usually form when an association between a certain behavior and context is established by consistently repeating a behavior in that context (Gardner, 2015 ; Lally & Gardner, 2013 ). Due to the association, the habitual behavior is automatically and sometimes unconsciously activated (Aarts & Dijksterhuis, 2000 ) while alternative behaviors become less accessible (Danner et al., 2007 ). Often, the effort required to initiate the habitual behavior decreases over time and initiation becomes effortless (Lally et al., 2011 ). Even when intentions change, engagement in habitual behavior commonly persists (Adriaanse & Verhoeven, 2018 ).

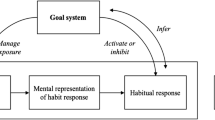

According to the goal–habit interface model (Wood & Rünger, 2016 ), many habits are initiated by goal-directed behavior. Initially, before habit formation, goals drive individuals to repeat a certain action in a specific context. Once a habit is formed, the habitual behavior shifts from goal-dependent to goal-independent behavior. In this case, behaviors are enacted based on context cues and irrespective of goals (Mazar & Wood, 2018 ). Nevertheless, as many individuals are unaware of this habit formation process, they might misattribute their habitual behavior to goals or intentions instead of habits (Loersch & Payne, 2011 ; Mazar & Wood, 2018 ).Wood & Neal ( 2016 ) suggest various essential components for habit-based interventions that target initiation and maintenance of health behavior change. They suggest the importance of habit-forming approaches for fostering repeated engagement in healthy behaviors while also disrupting undesirable behavior by habit-breaking approaches. As main components for habit formation, they suggest frequent repetition of the desirable behavior, creating a re-occurring context and context-cues, and administering rewards randomly (Wood & Neal, 2016 ). To break undesirable habits, context-cue disruption, re-structuring of one’s environment, and monitoring one’s behavior are suggested as efficient (Wood & Neal, 2016 ).

While there has been quite some research showing the beneficial effects of habits in health behavior change (e.g., exercising habit, healthy eating habit), only a few studies have focused on how study habits could improve students’ study behavior (e.g., Galla & Duckworth, 2015 ). Students’ ineffective study habits such as ineffective learning strategy use (Biwer et al., 2020a , b ; Foerst et al., 2017 ; Rea et al., 2022 ), high smartphone use (Chen & Yan, 2016 ; Lepp et al., 2015 ), or poor time management (Basila, 2014 ; Thibodeaux et al., 2017 ) seem to play a role in their study behavior and academic achievement. Breaking these ineffective habits and forming effective study habits instead by, for example, incorporating more desirably difficult learning strategies could help students to optimize their self-regulated learning and academic achievement.

In the present study, we aim to gain a better understanding of the nature of university students’ study habits, how students usually form new habits, and how they (try) to break ineffective habits. We explored this using a qualitative approach via focus group discussions with first- and second-year university students. As our goal was to dive beyond surface-level observations and gain an in-depth understanding of students’ experiences rather than generalizing to a larger population, a qualitative approach seemed most appropriate (Morse, 2008 ). Compared to a quantitative approach, a qualitative approach via focus groups or interviews offers various benefits (for a more general overview of focus group discussions in medical education, see Stalmeijer et al., 2014 ). First, they offer a relatively time- and cost-effective access to students’ thoughts and experiences. Second, by being able to directly engage with students, it is possible to ask students for further elaboration or clarification, which would not be possible using for example questionnaires and therefore ensuring an in-depth understanding. Third, due to the flexibility of this approach and our semi-structured question guide, we were able to capture students’ opinions while limiting imposing pre-existing assumptions about their study habits. Most importantly though, we anticipated that the interactions between students would be essential when discussing study habits and focus group discussions would thus allow a more diverse and multifaceted picture of students’ study habits. While habitual behaviors could be unconscious, we expected that hearing other students’ experiences would facilitate students’ reflections on similar or dissimilar experiences. Insights from our study can help to inform potential future study habit interventions to overcome students’ knowledge-behavior gap.

Research setting

This study was conducted at the Faculty of Health, Medicine, and Life Sciences (FHML) at Maastricht University, which is a public research university in the Netherlands. At Maastricht University (UM), the academic year is divided into six different blocks (i.e., teaching periods), including different thematic courses lasting between 4 and 8 weeks. Courses usually consist of lectures and tutorial sessions and are finalized with an exam. The tutorial sessions are structured according to the problem-based learning (PBL) approach. Within this approach, authentic scenarios are central to learning (Dolmans et al., 2005 ). In small tutorial groups, ranging from 10 to 12 students and one tutor, students are introduced to these scenarios according to a seven-step model (Moust et al., 2005 ). The first five steps, (1) term clarification, (2) problem definition, (3) brainstorming explanations, (4) structuring and analyzing the identified explanations, and (5) formulation of learning goals, take place during the tutorial session. Students then individually study literature to answer their learning goals during (6) self-study. Lastly, during a next tutorial session, students integrate and discuss findings from their self-study in a (7) post-discussion.

Admission to the medical program at UM is a selective procedure, with only limited places available. Students are only eligible if having followed a certain combination of STEM courses during high school. Furthermore, potential candidates have to undergo two selection rounds. In the first selection round, students’ high school transcripts, curriculum vitae, and a written assignment are evaluated. If of sufficient quality, candidates are invited to a second selection round, which is an assessment day at the university, where potential candidates have to fulfill various assignments during which their cognitive and (inter)personal characteristics and skills are assessed. Based on these criteria, students are ranked and selected. Admission to the biomedical program at UM was not selective for the cohort participating in this study. The only eligibility criterion was that students had followed a certain combination of STEM courses during high school and were proficient enough in English.

The majority of first-year FHML students at UM are assigned to a mentor and receive a formal learning strategy training in their first weeks (“Study Smart”; Biwer & De Bruin, 2023 ) to support their self-regulated learning and professional development. The learning strategy training consists of three 90-min small-group training sessions with different goals. In the first session, the main goal is to increase students’ awareness about effective and ineffective learning strategies, why certain strategies work better, and possibly misleading experiences that students might encounter when using (in)effective learning strategies. During the second session, students are asked to try-out different effective learning strategies and think about a concrete plan, how they could incorporate these during their self-regulated learning. During the third session, which is held a few weeks after the previous sessions, students are asked to reflect on their learning strategy use during their self-regulated learning and how they could improve. Throughout the year, students meet with their mentor and write a portfolio reflecting on their competencies related to program content, professional- and study behavior.

Participants

Twenty-nine first- and second-year medicine ( n = 14) and biomedical sciences ( n = 15) bachelor students participated in one of six focus group discussions. Students were on average 20.1 years old (14% male). Students were recruited via multiple channels. The first author contacted the mentor and course coordinators of the respective bachelor programs to share the study information with their students. Additionally, students were recruited via posters and approached after tutorials and lectures. During the recruitment phase, the study goal was advertised as exploration of students’ study methods and habits. We obtained written informed consent from all participants prior to the study. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire inquiring about their age, study program and year, and grade point average (GPA). Students’ GPA ranged from 5.8 to 9, with the mean GPA being 7.4 (on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest). Two students did not indicate their GPA. The faculty’s ethical review board (FHML-REC/2022/049) approved the study. Students received a small monetary reimbursement to compensate for their participation.

Focus groups

Students who completed the demographic questionnaire and indicated their availability were invited to the focus group discussions at university. The focus groups lasted approximately 80 min ( M = 78.4 min, SD = 4.2 min) and were moderated and observed by the first and second author. Based on a semi-structured focus group guide (see supplementary materials), students were asked which study methods they usually used during their self-study, what a typical study day looked like, and about their experiences with forming and breaking habits. The clarity of the questions within the focus group guide was piloted with two students prior to the focus group discussions. Based on their feedback, the wording of the questions was slightly adjusted to improve clarity. The first four focus groups were held at the end of students’ first academic year. Two additional focus groups were held at the beginning of students’ second bachelor year. The focus group guide was adjusted before the second part of data collection as we noticed that students had difficulties reflecting in-depth on their experiences with forming and breaking habits. Therefore, we created three vignettes describing concrete examples of how a habit was broken or formed based on students’ reflections during the first focus groups. Data was collected iteratively and occurred simultaneously with data analysis. In line with Morse ( 2015 ), as soon as we estimated our data to be sufficiently rich to gain a deep understanding of students’ study experiences and their habit-breaking and habit-forming experiences, we determined data saturation and stopped data collection. Data saturation is commonly an interpretive judgment in thematic analysis (for a critical stance regarding the concept “data saturation,” see Braun & Clarke, 2019 ). In our case, we started data analysis by descriptive line-by-line coding of the so far collected transcripts, clustering these codes, and searching for patterns, simultaneously to data collection. Based on the understanding we gained during these first analytic steps, we determined to have collected sufficient data to understand students’ experiences after six focus groups.

Data analysis and coding procedure

All focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Based on the thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ), we analyzed the focus group discussions inductively. Our analysis was data-driven and thus, the theme development did not mirror our question guide nor do the themes fully align with our potential pre-existing assumptions about students’ study habits (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ; Kiger & Varpio, 2020 ). We used pre-existing theories to establish our focus group guide and kept this knowledge as sensitizing concepts during the coding procedure (Bowen, 2006 ). We conducted a semantic analysis of participants’ accounts by interpreting their explicit meanings as recorded and transcribed. After thoroughly listening to the audio recordings and reading the transcripts in-depth multiple times, they were descriptively coded line-by-line using Atlas.ti (version 23.0.7.) by the first author (an extract of our codebook is included in the supplementary materials). Using these descriptive codes, the second author coded 50% of two transcripts without insights into the first coder’s line-by-line coding. The outcomes and coding alignments of these partial transcripts were discussed and definitions of codes were further specified, if necessary. Then, patterns within and across focus groups were discussed within the whole research team based on summaries of the transcripts and clustering of the descriptive codes done by the first and second author. Based on this discussion, the first and second author formulated themes, which were reviewed and refined with the entire research team. Additionally, the formulated themes were checked against the coded data and original transcripts. Throughout the analytic procedure, our research team engaged in regular discussions and asked for feedback from scholars outside of the research team during roundtable sessions and conference presentations to critically examine interpretations and findings. We followed a pragmatist approach in analyzing the data, prioritizing the practical relevance of knowledge instead of attempting to explain “reality” (Cherryholmes, 1992 ). The pragmatist approach offered us the flexibility and adaptability of addressing our research questions as well as generating practical implications from the identified themes while interpreting the data within our specific context.

Reflexivity statement

LD is a PhD student who completed a Bachelor’s degree at Maastricht University and is therefore familiar with the UM system also from a student perspective. FB is an educational psychologist with research interests in self-regulated learning and teacher professionalization and knows the PBL system in their role as mentor and tutor. RC is a cognitive psychologist with research expertise in behavior change and technology. AdB is an educational psychologist with research expertise in self-regulated learning in higher education. RC and AdB know the PBL system in various roles (student, teacher, mentor). We are aware that the findings of this study are co-created by interactions between the authors and participants. We thoroughly discussed each process step with all team members and discussed intermediate findings with educational scientists outside of the team and continuously reflected on the extent to which our individual personal experiences and beliefs shaped the research project.

We clustered students’ experiences into five themes: Goals Matter , Balancing Perceived Efficiency and Effectiveness when Studying , Navigating Student Life: from Structured Routines to Self-Regulation Challenges , the Quest for Effective Habits with Trying to Break Free From the Screen as subtheme, and the Motivation Roller Coaster .

Goals matter

Students mentioned various goals, which influenced their study behavior. Many students had a clear short-term goal of passing the exam in mind. For them, studying during the course served the goal of “collecting all the information” (student studying medicine (MED), focus group (FG) 2) to prepare for tutorial sessions. Studying for the exam served the goal of “actual studying” (student studying biomedical sciences (BMS), FG2), during which information is memorized or learned. Students experienced more pressure when studying for an exam compared to studying during the course. Approximately 1.5 weeks before an exam, students started intense studying. During this period, they dedicated extensive time to studying, often sacrificing a work-life balance and reducing time for activities like exercising, socializing, and hobbies.

Other students indicated having clear long-term academic goals such as receiving a high GPA or wanting to become a good doctor. These clear long-term goals helped them to study consistently, be less exam-oriented, and prioritize their studying also during the course, even if having to sacrifice other activities. Instead of studying solely to pass exams, students explained to be more consistent in their study behavior and tried to understand and learn the content continuously. They mentioned achieving this by planning and spreading their study load throughout the course. For example, one student mentioned:

I don’t study for exams anymore, I study because I want to be a good doctor. And I think that mindset also helped me change. […]. So it’s harder to find time around [studying], but I also prioritise [studying], university is the most important thing for me. If it means I don’t go to a party or I don’t go to the gym, which I also want to do, then that’s just how it is. (Student MED, FG5)

Balancing perceived efficiency and effectiveness when studying

Students generally had quite accurate metacognitive knowledge and were aware that active learning strategies and distributed learning sessions were more effective for long-term learning. Contrastingly, students did not necessarily use those strategies as they experienced that their own study strategies “work” (multiple students in multiple FGs) and were most efficient in reaching their short-term goal to pass the exam or having a strong habit of using them. For example, one student mentioned:

Well, I know it’s not really useful. But I still [summarize] a lot. But I know that it’s […] been proved that it’s not really effective. But I still, I don’t know, it’s just a habit. […] And it works. (Student MED, FG 3)

Students differed in which strategies they deemed to “work” (multiple students in multiple FGs) for themselves. For tutorial preparations, students usually read and summarized the provided sources. For exam preparations, students used various active and passive learning strategies such as re-reading, summarizing, creating mind maps, watching videos, recalling information, testing themselves by using past exams or creating flashcards, and explaining content to others or themselves. The amount of practice testing students used during their self-study depended on the availability of past exam questions in their study program as students experience creating practice questions themselves as too time consuming:

Some of our professors, they made […] really extensive kind of quizzes with lots of questions. And that was really helpful. I wish they did that for everything. (Student BMS, FG6)

To optimize their study efficiency, next to using cognitive learning strategies, students tried various resource management strategies, such as creating a planning for their tasks or studying with friends to stay motivated but often faced challenges in accurately managing their time and effort. Students usually started their study session by creating a planning or to-do list, but it was difficult to accurately know how long a task would take or to “really stick to it” (Student BMS, FG3). Instead of studying until a certain time, students usually studied until the task was finished or they could not focus anymore.

Navigating student life: from structured routines to self-regulation challenges

Students reported basing their study habits on what they had learned during high school, despite university being experienced as different. Next to the content being perceived as more in volume and difficulty, students also mentioned having to adjust to the change of setting. During high school, students often had a structured daily routine. When transitioning to university, they had to adjust to the lack of structure and external control, but also higher flexibility associated with student life. While students appreciated this increased freedom, it also came with the challenge of managing themselves and self-regulating various aspects of life: starting to study, moving to a new city, looking for new hobbies and friends, or managing their household.

When I lived with my parents in high school […], you have like a whole routine. […]. Now you can do things whenever you want to do it. And […] sometimes you have parties on Monday or on Wednesdays. So, it’s on random days. Yeah. And then you’re tired on Tuesdays. So, then you don’t do as much as other days. […] I think, it’s also part of student life. (Student MED, FG2)

Some students solved the lack of structure by actively creating more external structure in their daily life by joining committees, making appointments with others, or creating a clear separation between work and “personal” life. For other students, the lack of external structure seemed to negatively influence their willingness to form habits as they experienced habits as restricting flexibility. Some students appreciated the flexibility that they associated with student life and did not report actively looking for more structure. In search for more structure, students differed in their habit and preference of study location. Some students preferred to study at home to avoid distractions, whereas others preferred to study at university as they found it easier to initiate studying with others around and appreciated a separation between their studying and living space. During courses, students were more flexible in their study setting.

The quest for effective habits

Even though students experienced their current strategies to “work” for the exam, they reported intentions to change their current study behavior. These intentions targeted improving time management, such as following their planning, procrastinating less, cramming less, limiting screen time, and changing their sleeping schedule. They mentioned making study appointments with others, which helped to feel more accountable, and promoted adherence to intended behavior. Students also mentioned wanting to add steps to their current study habits such as completing their study notes or creating flashcards after each tutorial. For example, a student mentioned “I first had to […] talk about this topic, answer the question, then I was allowed, for example, to go to the bathroom” (student BMS, FG4) or working through flashcards when traveling. While students had intentions to change, they mentioned not necessarily prioritizing working on realizing their intentions since their current habits were sufficient to pass their exams but also encountering difficulties when trying to realize them. Students identified various reasons for this, for example, difficulties in creating a feasible planning, following their intention when not being motivated, or falling back into old habits when experiencing a setback. While having good intentions, students perceived change to be effortful, time-consuming, or being insecure about whether a change would actually lead to an improved outcome. For example, one student mentioned:

It’s not enough to have motivation to change that one point. Because it’s what you say, how do you make the change? By doing it daily. […]. That’s, you know, what I’m trying to do. Like be more consistent. […]. I’ll do great for the first couple of days, maybe two weeks, if I was really motivated. But then after I wake up on a bad day, I really don’t feel like it. And it’s this boring topic. I’ll push it back. […]. I’ll do something else. Then time runs out. Then we’re already kind of back in the bad cycle of procrastinating on everything. […] If there’s not the stress of a deadline, then it comes down purely to motivation every day. (Student BMS, FG3)

Trying to break free from the screen

One particularly challenging habit students tried to break was their smartphone habit. Students mentioned turning to their phones or study unrelated websites automatically when lacking focus or procrastinating. This was experienced as distracting and negatively influencing students’ studying. They tended to spend more time on their phone than anticipated, for example, if wanting to briefly check something. To reduce this automatic use, students tried to discontinue their habit by re-structuring their environment so that the distraction would be less accessible or interchanging their phone use with another activity such as reading. Instead of having their phone on the table when studying, they put their phone out of sight, blocked or deleted apps in the morning, or exchanged their phone with a friend’s phone. Even though students used various strategies to reduce the distraction from these devices, students continuously struggled in limiting their screen time.

I am so done with my phone being the hugest distraction in my life at this point, it just annoys the hell out of me. I’m actually breaking a habit right now, it’s called ‘no Instagram anymore’. Yes, it’s very bad, but I am... I’m not going to say I am improving because I am not, but I am trying to improve. (Student BMS, FG6)

The motivation roller coaster

Students described experiencing a fluctuation in motivation throughout a course and academic year, which influenced their study behavior and behavioral change intentions. With their past stressful exam preparation in mind, students reported beginning a new course with many resolutions wanting to improve what went “wrong,” such as aiming to study more consistently or to start exam preparations earlier. Students often managed to realize their resolutions for the first few weeks of a new course. However, after approximately 2 weeks, students lost motivation and started to slack with their studying (e.g., studying less consistently). They experienced less pressure to study, and thus experienced more motivational conflict when initiating studying due to tempting alternative activities, other course obligations, or interferences outside of university. For example, one student, being well aware of the consequences of procrastination, mentioned:

I can relax now and do this fun thing. And then maybe have to do like, a quick version of this assignment late at night. (Student BMS, FG3)

Three weeks prior to the exam, students felt increased pressure when realizing how close the exam and how much work was left. This pressure motivated students to catch up on the coursework and spend more time studying. Often, students focused on getting the studying done (e.g., creating summaries for each case) and cramming the content using methods that previously worked to pass the exam. For example, one student mentioned:

I’m also motivated in the beginning of a new block. […] I have this motivation over me. Like, well, now I’m going to keep up with it. And then sometimes, […] I lose track of the course that we’re in. And I’m behind again. And then I lose it a bit. So, when I get behind, and I’m like, okay, now I just do the minimal. And then two, a week and a half, before the exam, then I get my motivation back. (Student MED, FG2)

This paper outlines the findings of a study exploring university students’ study habits during self-regulated learning. We held focus groups aiming to explore university students’ current study habits, habit formation, and experiences with breaking habits. A thematic analysis of the transcribed data revealed five themes and one subtheme, which offer insights into our research aims regarding how students usually form new habits, and how they (try) to break ineffective habits. Our study offers a detailed exploration of university students’ study habits. Using a qualitative approach, we were able to dive beyond surface-level observations by exploring students’ experiences and factors, which influence these habits, their formation, and the challenges associated with breaking habits in-depth. While our chosen approach allows for a rich and nuanced understanding of the multifaceted nature of students’ study habits, the goal of a qualitative approach is commonly not to generalize findings to a larger population (Morse, 2008 ). The findings of this study are experiences from a specific student population rooted within a specific educational and cultural context. Including a thick description of this context, we try to establish transferability of our findings by indicating how they could apply to other contexts and student populations.

Students’ study habits

Students had different study habits depending on their goals. Students with clear short-term goals of passing the exam focused on collecting information during the course and started intense studying shortly before the exam. Students with long-term academic or career goals planned their study sessions continuously and focused more on learning the study content. Students differed in their preferred study setting when preparing for exams, but usually had a habit and preference of where and how to study. During courses, students were more flexible in their study setting. These findings suggest that long-term academic goal setting helps students to prioritize long-term learning by spreading out study sessions and focusing on learning the study content continuously. Long-term academic goal setting might be more evident for some study programs than for others. In study programs such as medicine, many first-year students have a clear goal of becoming a good doctor with long-term retention of knowledge and skills as important factors to reach that goal. Study programs with more diverse career paths might make it difficult for students to envision clear long-term goals. This lack of long-term goal setting might hamper students’ motivation to ensure more effortful studying in a manner that ensures long-term retention or best possible grades. Previous research indicates that students’ long-term perspectives are related to better self-regulation strategies (Bembenutty & Karabenick, 2004 ; De Bilde et al., 2011 ).

Students tried to be strategic in their learning strategy use by balancing perceived efficiency and effectiveness of the methods in reaching their goals. For tutorial preparations, students usually read and summarized the provided sources. For exam preparations, students combined active and passive learning strategies such as summarizing, watching videos, or explaining content to themselves. Unlike often assumed in the literature (e.g., Morehead et al., 2016 ; Yan et al., 2016 ), students in the current sample had quite accurate metacognitive knowledge. This could be related to the fact that they followed a formal learning strategy training at the beginning of their studies or the PBL system employed at UM, which aims to foster an active learning approach (Dolmans et al., 2005 ). Students might have been aware of effective and ineffective learning strategies and received suggestions on how to incorporate as many active learning approaches as possible within their self-regulated learning. Nevertheless, they used learning strategies, which are not the most effective for long-term learning but ones that they deemed most time-efficient to pass exams. While students were often aware of this discrepancy, assessment forms were an important driver for learning strategy choices. This is in line with prior research indicating that students adapt their learning strategies to examination requirements (Broekkamp & Van Hout-Wolters, 2007 ; Rovers et al., 2018 ). Bachelor students are often assessed using multiple choice questions, which focus on recognizing information instead of retention. They thus use learning strategies to maximize success for that assessment type. In order to nudge students to use learning strategies essential for long-term learning, it is crucial to align assessment by using methods that stimulate long-term learning and prioritize testing understanding instead of recognition (Van der Vleuten et al., 2010 ).

Furthermore, students’ willingness to incorporate active learning strategies such as retrieval practice seemed dependent on the available resources in their study program. In the medicine program, students had access to past exam questions and thus used them during exam preparations. Students in the biomedical sciences program, having no access to previous exam questions, found it difficult and time-consuming to create practice questions themselves and appreciated course coordinators who provided example questions. This suggests that more support from educators, such as providing practice questions or training sessions on formulating practice questions, might further increase students’ use of active learning strategies.

Forming and breaking habits

In line with previous research, students reported basing their study methods on what they had learned during high school (Dirkx et al., 2019 ). They updated these methods if they did not help them to achieve their goals by trying to embed additional steps in pre-existing habits (e.g., if going to bed, then reading notes). This method of specific if–then plans also called implementation intentions (Adriaanse & Verhoeven, 2018 ; Gollwitzer, 1993 ) is commonly suggested to foster habit formation and habit breaking. By pre-selecting a situation and mentally rehearsing the if–then link, individuals are more likely to automatically trigger the desired behavior when encountering the situation. Formulating these if–then plans could create new associations that compete with existing habits. If the new cue-action link is stronger than the habitual pattern, the desired action could potentially override the habitual response. While research across various domains supports the effectiveness of implementation intentions in promoting goal-directed actions (Adriaanse et al., 2011 ; Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006 ), it is unclear whether implementation intentions influence learners’ learning outcomes or metacognition (Hoch et al., 2020 ).

Students reported intentions to change their study behavior. While their intentions targeted mainly improving time management aspects or wanting to add steps to their current study habits, disentangling the extent to which students wanted to realize these intentions was difficult. Additionally, detailed reflections of how students broke past ineffective habits and whether they actually changed their behavior once their habits did not “work” anymore remained scarce, making it difficult to fully target our third research aim. Students did not see change as a priority because their current method “worked” to pass exams. As mentioned above, assessment was an important driver for students’ learning strategy choices but also a key factor in their behavioral change intentions. Students were successful in passing exams and thus did not perceive change as necessity or added benefit. However, they also indicated not knowing how to change, or experiencing change as effortful and time-consuming. The difference between not changing because perceiving change as having no additional value or because not knowing how to has important implications for behavioral change interventions. Students who do not perceive change as beneficial might profit from interventions that highlight the utility value of effective learning strategies (e.g., McDaniel & Einstein, 2020 ) in achieving a sufficient grade to pass a course as efficiently as possible. Students who do not know how to change might profit from interventions that provide them with information on how behavioral change could be achieved. More research is necessary to disentangle the extent to which students are willing to form new and break old habits and if so, how they could be best supported in this.

Another factor influencing students’ intention to change and breaking old habits was their fluctuating motivation throughout the course. Students began a new course with many resolutions wanting to improve what went “wrong” the block before but motivational conflict and their usual context quickly disabled them from realizing their intentions and instead continuing with unwanted behavior. In line with Verplanken and colleagues ( 2018 ), this finding suggests a potential importance of temporal considerations in behavioral change interventions in transition periods. Interventions held at the beginning of a new course might benefit from students’ increased motivation to change.

Additionally, students’ capacity to form new and break old habits seems to be influenced by their transition to a more independent environment. During this transition, they did not solely focus on establishing effective study habits but also had to navigate their flexible schedule during which they encountered other self-regulation challenges. According to the habit discontinuity hypothesis (Verplanken & Wood, 2006 ), major life events or disruptions can serve as catalysts for behavior change, indicating that the transition to university could potentially serve as a great opportunity to break existing habits and form more adaptive ones. As the transitions create a habit discontinuity, people change their habits and adopt new behaviors as old cues and routines that support existing habits are weakened or disrupted (Verplanken et al, 2018 ). As a result, individuals are more receptive to new opportunities to establish new habits or modify existing ones. This suggests that it might be valuable to support students in building effective habits as soon as they start university to make use of the discontinuity of existing habits, or, as mentioned above, at the beginning of a new course later in the semester. Contrastingly, our findings suggest that the new context and flexibility also challenge the formation of new habits, since it is difficult to “piggy-bag” new habits onto existing ones and because the needs for what makes learning effective to pass exams in the new context are not clear yet. Students solved this by actively looking for more structure. More research is necessary to investigate how the transition to university influences students’ capacity to form new habits.

Another factor, which could be important in students’ study habits and breaking and formation hereof, is co-regulation. The latter describes how learners’ cognition, emotions, and motivation during learning are influenced by interaction with others (Bransen et al., 2022 ; Hadwin & Oshige, 2011 ). Students mentioned making study appointments with others, which helped them to feel more accountable for their actions and thus promoted adherence to their intended behavior, suggesting that co-regulation could be an important factor in supporting students to break ineffective habits and form new habits. Furthermore, by observing how peers study, students could learn to model adaptive behavior, enabling them to form habits that incorporate more effective learning strategies. Furthermore, being able to exchange experiences with peers during the habit formation and breaking process, which might be associated with negative emotions such as stress and frustration, could help students to cope and stay motivated during their behavior change journey. However, more research is necessary to investigate how co-regulation could influence students’ study habits.

Strengths and limitations

Our findings highlight the central role of students’ goals in shaping their study habits. Knowing how goals influence study habits offers valuable insights into the importance of tailoring educational strategies to better align with students’ goals and to shed light onto goal-driven behavior in education. Furthermore, the discrepancy between students’ knowledge and behavior when it comes to the limited application of effective learning strategies seems to stem from the low perceived efficiency of these strategies, highlighting a need to increase students’ perceived efficiency of effective learning strategies to close the gap between knowledge and behavior. Furthermore, the identified challenges related to motivation fluctuations within and throughout a course and the transitioning from high school to a self-regulated learning environment in university present original perspectives, which so far remain underexamined in the context of self-regulated learning. Our study offers valuable insights into the dynamic hurdles that students face when attempting to modify their study habits and highlights the importance of aligning assessment methods with life-long learning goals. However, this study has various limitations. First, we conducted convenience sampling. We did not target a specific target population but all first-year biomedical sciences and medicine students were eligible to participate. As the study goal was advertised as an exploration of students’ study methods and habits, it might have been possible that especially students who were more confident in their study methods or habits participated leading to a biased perspective. While we cannot rule this out, students were openly sharing that they engaged in methods that they thought were not the most effective and also mention not currently wanting to change their habits. Furthermore, students’ self-reported GPA ranged from 5.8 to 9, suggesting a mix between low- and high-achieving students. Additionally, the students’ in our sample received a formal learning strategy training in their first weeks to support their self-regulated learning and professional development, which potentially shaped their study behaviors and perspectives and thus outcomes of this study. Next to this, we did not split students from the two different study programs but mixed them within our focus groups. As mentioned above, the structure of the study programs might have shaped the results and further research is necessary to investigate to what extent these findings transfer to other study programs. Second, we held four focus groups at the end of students’ first academic year and two focus groups at the beginning of students’ second academic year. This change in context might have influenced students’ perspectives on their study methods and habits. Future research is necessary to investigate to what extent students’ study methods and habits change throughout their study program. Third, we asked students to reflect on their habitual behavior. As habits are often unconscious, we did not explicitly ask students about their habits but instead asked them to reflect on behavior they usually engaged in. The fact that we did not offer any definition of what counts as a usual behavior might have led to different interpretations hereof. While not the goal of this study, a quantitative research design capturing students’ habitual behavior could give more systematic insights by clearly defining and operationalizing the concepts of “usual behavior” in measurable terms. For example, it could be operationalized as behaviors that participants engage in at least three times a week or behaviors that they have engaged in consistently for the past six months or using the Self-Report Habit Index (SRHI, Verplanken & Orbell, 2003 ).

Overall, this study contributes to the literature by providing a qualitative exploration of university students’ study habits, formation hereof, and difficulties they experience when breaking habits. A thematic analysis of six focus groups indicated that students had different study habits depending on their goals. While showing accurate metacognitive knowledge of what are effective learning strategies, students often used other learning strategies they deemed most efficient in reaching their goals. Students indicated intentions to change but did not prioritize change as their current habits enabled them to pass exams and change was not perceived as adding value. Fluctuations in motivation across courses and transitioning to a self-regulated life hampered students’ intentions to form new and break old habits. The findings give insights into influential factors affecting students’ behavioral change intentions and suggest the importance of aligning assessment methods with life-long learning and supporting students in their long-term academic goal setting to prioritize study habits that target lasting learning to optimally foster students’ self-regulated learning.

Data Availability

Due to the nature of the research, supporting data is not available to ensure privacy of participants.

Aarts, H., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2000). Habits as knowledge structures: Automaticity in goal-directed behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 (1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.53

Article Google Scholar

Adriaanse, M. A., & Verhoeven, A. (2018). Breaking habits using implementation intentions. In B. Verplanken (Ed.), The Psychology of Habit (pp. 169–188). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97529-0_10

Adriaanse, M. A., Vinkers, C. D. W., De Ridder, D. T. D., Hox, J. J., & De Wit, J. B. F. (2011). Do implementation intentions help to eat a healthy diet? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Appetite, 56 (1), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2010.10.012

Ariel, R., & Karpicke, J. D. (2018). Improving self-regulated learning with a retrieval practice intervention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 24 (1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000133

Basila, C. (2014). Good time management and motivation level predict student academic success in college online courses. International Journal of Cyber Behavior Psychology and Learning, 4 (3), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcbpl.2014070104

Bembenutty, H., & Karabenick, S. A. (2004). Inherent association between academic delay of gratification, future time perspective, and self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 16 (1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000012344.34008.5c

Biwer, F., & De Bruin, A. B. H. (2023). Teaching students to ‘Study Smart’ – A training program based on the science of learning. In In their own words: What scholars and teachers want you to know about why and how to apply the science of learning in your academic setting (pp. 411–425). Society for the Teaching of Psychology. https://teachpsych.org/ebooks/itow

Biwer, F., De Bruin, A. B. H., Schreurs, S., & Oude Egbrink, M. G. A. (2020a). Future steps in teaching desirably difficult learning strategies: Reflections from the study smart program. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9 (4), 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2020.07.006

Biwer, F., Egbrink, M. G. A. O., Aalten, P., & De Bruin, A. B. H. (2020b). Fostering effective learning strategies in higher education—A mixed-methods study. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9 (2), 186–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2020.03.004

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning (pp. 56–64). Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society.

Google Scholar

Blasiman, R. N., Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2017). The what, how much, and when of study strategies: Comparing intended versus actual study behaviour. Memory, 25 (6), 784–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2016.1221974

Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5 (3), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500304

Bransen, D., Govaerts, M. J. B., Panadero, E., Sluijsmans, D. M. A., & Driessen, E. W. (2022). Putting self-regulated learning in context: Integrating self-, co-, and socially shared regulation of learning. Medical Education, 56 (1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14566

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health., 13 (2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

Broekkamp, H., & Van Hout-Wolters, B. (2007). The gap between educational research and practice: A literature review, symposium, and questionnaire. Educational Research and Evaluation, 13 (3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610701626127

Broeren, M., Heijltjes, A., Verkoeijen, P., Smeets, G., & Arends, L. (2021). Supporting the self-regulated use of retrieval practice: A higher education classroom experiment. Contemp Educ Psychol, 64 , Article 101939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101939

Chen, Q., & Yan, Z. (2016). Does multitasking with mobile phones affect learning? A review. Computers in Human Behavior, 54 , 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.047

Cherryholmes, C. H. (1992). Notes on pragmatism and scientific realism. Educational Researcher, 21 (6), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X021006013

Danner, U. N., Aarts, H., & De Vries, N. K. (2007). Habit formation and multiple means to goal attainment: Repeated retrieval of target means causes inhibited access to competitors. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33 (10), 1367–1379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207303948

De Bilde, J., Vansteenkiste, M., & Lens, W. (2011). Understanding the association between future time perspective and self-regulated learning through the lens of self-determination theory. Learning and Instruction, 21 (3), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.03.002

Dembo, M. H., & Seli, H. P. (2004). Students’ resistance to change in learning strategies courses. Journal of Developmental Education, 27 (3), 2–11.

Dignath, C., & Veenman, M. V. J. (2021). The role of direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of self-regulated learning—Evidence from classroom observation studies. Educational Psychology Review, 33 (2), 489–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09534-0

Dirkx, K. J. H., Camp, G., Kester, L., & Kirschner, P. A. (2019). Do secondary school students make use of effective study strategies when they study on their own? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33 (5), 952–957. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3584

Dolmans, D. H. J. M., De Grave, W., Wolfhagen, I. H. A. P., & Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2005). Problem-based learning: Future challenges for educational practice and research. Medical Education, 39 (7), 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02205.x

Dresel, M., Schmitz, B., Schober, B., Spiel, C., Ziegler, A., Engelschalk, T., Jöstl, G., Klug, J., Roth, A., Wimmer, B., & Steuer, G. (2015). Competencies for successful self-regulated learning in higher education: Structural model and indications drawn from expert interviews. Studies in Higher Education, 40 (3), 454–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1004236

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14 (1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Fiorella, L. (2020). The science of habit and its implications for student learning and well-being. Educational Psychology Review, 32 (3), 603–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09525-1

Foerst, N. M., Klug, J., Jöstl, G., Spiel, C., & Schober, B. (2017). Knowledge vs. Action: Discrepancies in university students’ knowledge about and self-reported use of self-regulated learning strategies. Frontiers in Psychology , 8, Article 1288. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01288

Galla, B. M., & Duckworth, A. L. (2015). More than resisting temptation: Beneficial habits mediate the relationship between self-control and positive life outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109 (3), 508–525. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000026

Gardner, B. (2015). A review and analysis of the use of ‘habit’ in understanding, predicting and influencing health-related behaviour. Health Psychology Review, 9 (3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2013.876238

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta‐analysis of effects and processes. In M.P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology , Vol. 38, Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 69–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). Goal achievement: The role of intentions. European Review of Social Psychology, 4 (1), 141–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000059

Grunschel, C., Schwinger, M., Steinmayr, R., & Fries, S. (2016). Effects of using motivational regulation strategies on students’ academic procrastination, academic performance, and well-being. Learning and Individual Differences, 49 , 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.06.008

Hadwin, A., & Oshige, M. (2011). Self-regulation, coregulation, and socially shared regulation: Exploring perspectives of social in self-regulated learning theory. Teachers College Record, 113 (2), 240–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811111300204

Hartwig, M. K., & Dunlosky, J. (2012). Study strategies of college students: Are self-testing and scheduling related to achievement? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19 (1), 126–134. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-011-0181-y

Hoch, E., Scheiter, K., & Schüler, A. (2020). Implementation intentions related to self-regulatory processes do not enhance learning in a multimedia environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 11 , Article 46. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00046

Kiger, M. E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher, 42 (8), 846–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1755030

Lally, P., & Gardner, B. (2013). Promoting habit formation. Health Psychology Review, 7 (1), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2011.603640

Lally, P., Van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40 (6), 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Lally, P., Wardle, J., & Gardner, B. (2011). Experiences of habit formation: A qualitative study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 16 (4), 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2011.555774

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2015). The relationship between cell phone use and academic performance in a sample of US college students. SAGE Open, 5 (1), Article 215824401557316. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015573169

Loersch, C., & Payne, B. K. (2011). The situated inference model: An integrative account of the effects of primes on perception, behavior, and motivation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6 (3), 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611406921

Mazar A., Wood W. (2018). Defining habit in psychology. In Verplanken B. (Ed.), The psychology of habit: Theory, mechanisms, change, and context (pp. 13–29). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97529-0_2

McDaniel, M. A., & Einstein, G. O. (2020). Training learning strategies to promote self-regulation and transfer: The knowledge, belief, commitment, and planning framework. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15 (6), 1363–1381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620920723

Morehead, K., Rhodes, M. G., & DeLozier, S. (2016). Instructor and student knowledge of study strategies. Memory, 24 (2), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2014.1001992

Morse, J. M. (2008). “It’s only a qualitative study!” Considering the qualitative foundations of social sciences. Qualitative Health Research, 18 , 147–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307310262

Morse, J. M. (2015). Data Were Saturated. …. Qualitative Health Research, 25 (5), 587–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315576699

Moust, J. H. C., Van Berkel, H. J. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2005). Signs of erosion: Reflections on three decades of problem-based learning at Maastricht University. Higher Education, 50 (4), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6371-z

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology , 8, Article 422. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Rea, S. D., Wang, L., Muenks, K., & Yan, V. X. (2022). Students can (mostly) recognize effective learning, so why do they not do it? Journal of Intelligence, 10 (4), Article 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10040127

Rothman, A. J., Sheeran, P., & Wood, W. (2009). Reflective and automatic processes in the initiation and maintenance of dietary change. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 38 (S1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9118-3

Rovers, S. F. E., Stalmeijer, R. E., Van Merriënboer, J. J. G., Savelberg, H. H. C. M., & De Bruin, A. B. H. (2018). How and why do students use learning strategies? A mixed-methods study on learning strategies and desirable difficulties with effective strategy users. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 , Article 2501. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02501

Stalmeijer, R. E., McNaughton, N., & Van Mook, W. N. K. A. (2014). Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Medical Teacher, 36 (11), 923–939. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.917165

Thibodeaux, J., Deutsch, A., Kitsantas, A., & Winsler, A. (2017). First-year college students’ time use: Relations with self-regulation and GPA. Journal of Advanced Academics, 28 (1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X16676860

Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M., Schuwirth, L. W. T., Scheele, F., Driessen, E. W., & Hodges, B. (2010). The assessment of professional competence: Building blocks for theory development. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 24 (6), 703–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2010.04.001

Verhoeven, A. A. C., Adriaanse, M. A., Evers, C., & De Ridder, D. T. D. (2012). The power of habits: Unhealthy snacking behaviour is primarily predicted by habit strength. British Journal of Health Psychology, 17 (4), 758–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02070.x

Verplanken, B., Roy, D., & Whitmarsh, L. (2018). Cracks in the wall: Habit discontinuities as vehicles for behaviour change. In B. Verplanken (Ed.), The Psychology of Habit (pp. 189–205). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97529-0_11

Verplanken, B. (2018). Introduction. In B. Verplanken (Ed.), The Psychology of Habit (pp. 1–10). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97529-0_1

Verplanken, B., & Orbell, S. (2003). Reflections on past behavior: A self-report index of habit strength. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33 (6), 1313–1330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01951.x

Verplanken, B., & Wood, W. (2006). Interventions to break and create consumer habits. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25 (1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.25.1.90

Waldeyer, J., Fleischer, J., Wirth, J., & Leutner, D. (2020). Validating the resource-management inventory (ReMI): Testing measurement invariance and predicting academic achievement in a sample of first-year university students. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 36 (5), 777–786. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000557

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2016). Healthy through habit: Interventions for initiating & maintaining health behavior change. Behavioral Science & Policy, 2 (1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/237946151600200109

Wood, W., & Rünger, D. (2016). Psychology of habit. Annual Review of Psychology, 67 , 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

Yan, V. X., Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2016). On the difficulty of mending metacognitive illusions: A priori theories, fluency effects, and misattributions of the interleaving benefit. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145 (7), 918–933. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000177

Zimmerman, B. J. (1986). Becoming a self-regulated learner: Which are the key subprocesses? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 11 (4), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(86)90027-5

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank our participants for their time-commitment and sharing their experiences openly. Additionally, we would like to thank the members of the EARLI Emerging Field Group 3 “Monitoring and Regulation of Effort” for the ongoing discussions on the topic of effort monitoring and regulation that contributed to this research.

This work was funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) (VIDI grant number VI.Vidi.195.135) awarded to Anique de Bruin.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Development and Research, School of Health Professions Education (SHE), Maastricht University, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Louise David, Felicitas Biwer & Anique de Bruin

Department of Health Promotion, School of Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Rik Crutzen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study concept and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by LD and FB in close consultation with AdB and RC. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LD. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Louise David .

Ethics declarations

The artificial intelligence tool Chat GPT 3.5 was used to refine the titles of four of the identified (sub-)themes. Based on these suggestions, the titles were adapted. We kept a list of the tools’ original title suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 20 KB)

Supplementary file2 (docx 22 kb), rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

David, L., Biwer, F., Crutzen, R. et al. The challenge of change: understanding the role of habits in university students’ self-regulated learning. High Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01199-w

Download citation

Accepted : 12 February 2024

Published : 10 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01199-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Desirable difficulties

- Self-regulated learning

- Behavioral change

- Higher education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

THE IMPACT OF STUDY HABITS ON THE ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF STUDENTS

Related Papers

ariel ochea

Impact Factor(JCC): 1.7843-This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us ABSTRACT The development of a Country relies mostly on the levels of education among the people. Without education human race would have remained but as another animal race. Education is a process towards development. The term study habit can be as the students' way of study whether systematic, efficient or inefficient. Academic achievement refers to what and how an individual has learnt qualitatively and quantitatively after a period of instruction given. A habit is something that is done on a scheduled, regular, planned basis and that is not relegated to a second place or optional place in one's life. It is simply done, no reservations, no excuses, and no expectations. Study habits keep the learner perfect in getting knowledge and developing attitude towards things necessary for achievement in different field of human endeavour. Students who develop good study habits at school increase the potential to complete their assignments successfully and to learn the material they are studying. They also reduce the possibility of not knowing what is expected and of having to spend time studying at home. Study habits are the ways that your study habits that you have formed during your school years. Study habits can be good ones, or bad ones. Good study habits include being organized, keeping good notes, reading your textbooks, listening in class, and working every day. Bad study habits include skipping class, not doing your work, etc.

The Impact of Good Study Habit on Academic Achievement of Secondary School Students

Awolesi Oluwadamilola

INTRODUCTION The present day educational sector is becoming increasingly dynamic. The determination of every individual is to attain success and this success affects the personal and social dimensions of life. In this regard, academic performance is one of the major factors that influence individual's success in any educational setting. It is any body's guess that good habits and skills will help us to promote efficiency in our tasks. In education, proper study habits and skills requires proficiency as well as optimum learning quality (Dehghani & Soltanalgharaei, 2014). Productive study requires conceptualization and intention. It could include some skills such as note-taking, observation, asking question, listening, thinking and presenting idea with respect to new discoveries. Thus, students are expected to be interested in learning and must be able to apply requisite skills. On the other hand, inefficient study leads to waste of time and learner's energy (Hashemian & Hashemian, 2014). Study habits and skills like other skills can be taught and learnt. The interplay among motivation, habits, attitudes and behaviors has great impact on the academic performance of students. Study habit is buying out a dedicated scheduled and uninterrupted time to apply one's self to the task of learning. Studying is the procedure of getting information from prints that is information stored in written materials (magazines, newspapers, books). It is an organized gaining of intelligence and an interpretation of information and ideologies that calls for memorizing and usage. Studying can be expressed as the utilization of one's intellectual ability to the gaining, comprehending and arrangement of information; doing it over and over again entails some method of formal learning. Habit is a thing that one does often and almost without thinking; especially something that is hard to stop. A person's habit consists of plethora of ways an individual performs specific and general activity. Habit is relative to person or people. Each human being acts in a unique way. This is so because nature made things

Epoh Sedruol