Advertisement

The relationship between reading and listening comprehension: shared and modality-specific components

- Open access

- Published: 05 December 2018

- Volume 32 , pages 1747–1767, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- M. C. Wolf ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5995-9265 1 ,

- M. M. L. Muijselaar 2 , 4 ,

- A. M. Boonstra 3 &

- E. H. de Bree 4

34k Accesses

32 Citations

35 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This study aimed to increase our understanding on the relationship between reading and listening comprehension. Both in comprehension theory and in educational practice, reading and listening comprehension are often seen as interchangeable, overlooking modality-specific aspects of them separately. Three questions were addressed. First, it was examined to what extent reading and listening comprehension comprise modality-specific, distinct skills or an overlapping, domain-general skill in terms of the amount of explained variance in one comprehension type by the opposite comprehension type. Second, general and modality-unique subskills of reading and listening comprehension were sought by assessing the contributions of the foundational skills word reading fluency, vocabulary, memory, attention, and inhibition to both comprehension types. Lastly, the practice of using either listening comprehension or vocabulary as a proxy of general comprehension was investigated. Reading and listening comprehension tasks with the same format were assessed in 85 second and third grade children. Analyses revealed that reading comprehension explained 34% of the variance in listening comprehension, and listening comprehension 40% of reading comprehension. Vocabulary and word reading fluency were found to be shared contributors to both reading and listening comprehension. None of the other cognitive skills contributed significantly to reading or listening comprehension. These results indicate that only part of the comprehension process is indeed domain-general and not influenced by the modality in which the information is provided. Especially vocabulary seems to play a large role in this domain-general part. The findings warrant a more prominent focus of modality-specific aspects of both reading and listening comprehension in research and education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Towards a dynamic, comprehensive conceptualization of dyslexia

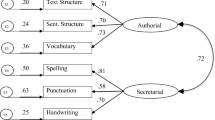

Assessing early writing: a six-factor model to inform assessment and teaching

Word problems in mathematics education: a survey

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The twenty-first century has seen an increasing reliance on obtaining information via the audio-visual channel (Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010 ). This means that relatively speaking, book reading is declining among children and adolescents (Mangen, 2016 ; OECD, 2010 ), whereas consumption of audio(visual) information through, for example, TV and computer, is increasing (Rideout et al., 2010 ). At the same time, reading comprehension is an essential subject in primary education. It is known as an important predictor of children’s school career and lifelong learning (Spörer & Brunstein, 2009 ). Children’s reading comprehension skill levels are monitored through all years of primary education, and, if deemed necessary, additional coursework or interventions are provided. In contrast, listening comprehension has received much less attention in the educational system (Mommers, 2007 ), despite studies showing that there are specific listening comprehension problems, for example in children diagnosed with ADHD (McInnes, Humphries, Hogg-Johnson, & Tannock, 2003 ) or second-language learners (Bingol, Celik, Yildiz, & Mart, 2014 ; Goh, 2000 ). Given the increasing importance of listening comprehension in daily life, the status of listening comprehension in education might need to be reconsidered and insight into the development of the skill is needed. The question arises whether listening and reading comprehension are, conform to how they are treated in the educational practice, the same general comprehension skill albeit with information provided in different modalities, or whether they are different processes with different underlying modality-specific skills. In other words, the relationship between reading and listening comprehension should be examined.

Theories of comprehension generally do not elaborately address the relationship between comprehension types in which the input is provided in different modalities (for a review see McNamara & Magliano, 2009 ). Kintsch and Van Dijk ( 1978 ) proposed the situation model of comprehension. According to this framework, comprehension entails the construction of a situation model, i.e., a mental representation of the situation conveyed by the words of a text. This highly influential comprehension model mentions that comprehension types will differ in some aspects, without specifying these differences. Nevertheless, Kintsch and Van Dijk ( 1978 ) did recognize that the input modality might affect the comprehension process in which a situation model is built. Gernsbacher, Varner, and Faust ( 1990 )’s structure-building model is built upon Kintsch and Van Dijk ( 1978 )’s situation model. Gernsbacher et al. ( 1990 )’s model describes the influence of the input modality on comprehension: the modality of the initial information does not influence the creation of the situation model. Instead, Gernsbacher et al. ( 1990 ) propose “a general comprehension skill that transcends modality”. In other words, comprehension is seen as a domain-general skill that is not tied to the modality of the input. As such, reading and listening comprehension are two versions of the same comprehension skill.

A complication of general comprehension theories is that they are confounded due to practical and methodological issues. A measure of comprehension must always be administered in a specific modality. If an effect of general comprehension is then found, with general comprehension having been measured in the auditory modality, to what extent does this effect then describe general comprehension if not listening comprehension? A striking example of the confounding effect of not taking into account the input modality in a comprehension theory can be found in the simple view of reading (Hoover & Gough, 1990 ). It is theorized that reading comprehension is the product of word decoding skills (measured as word reading fluency or word reading accuracy) and linguistic comprehension, which is general comprehension of language-related information. In practice, however, linguistic comprehension is most often measured as listening comprehension (LARRC, 2017 ). As a consequence, conclusions based on this framework concerning relationship between linguistic comprehension and reading comprehension and decoding only apply to listening comprehension, and not to a general linguistic comprehension process. The influence of modality-specific aspects of listening comprehension are thus not considered within the simple view of reading framework. These confounds in comprehension theories might have resulted in the neglect of modality-specific effects in research on comprehension, as well as the neglect of listening comprehension within education.

Some studies have examined the relationship between reading and listening comprehension directly, and not unintentionally by using listening comprehension as a measure of general linguistic comprehension. Listening comprehension and reading comprehension are highly related (Cain, Oakhill & Bryant 2000 ; Diakidoy, Stylianou, Karefillidou, & Papageorgiou, 2005 ; Protopapas, Simos, Sideridis, & Mouzaki, 2012 ; Tilstra, McMaster, Van Den Broek, Kendeou, & Rapp, 2009 ). Specifically, in opaque languages such as English the influence of listening comprehension as a measure of linguistic comprehension on reading comprehension increases over time, whereas the predictive strength of word reading fluency on reading comprehension decreases (Catts, Adlof, Hogan, & Weismer, 2005 ; Diakidoy et al., 2005 ; Vellutino, Tunmer, Jaccard, & Chen, 2007 ; Verhoeven & van Leeuwe, 2008 ). For transparent languages, such as Dutch, even for beginning readers listening comprehension is a stronger predictor of reading comprehension than decoding, because decoding is already acquired at a younger age (Florit & Cain, 2011 ).

The relation between reading and listening comprehension can vary due to the demands of different task formats and types of texts that have to be comprehended (Diakidoy et al., 2005 ). Diakidoy et al. ( 2005 ) reported a correlation between the two comprehension types of r = .63 when using a comprehension test with exactly the same format for both reading and listening. This correlation was twice as high compared to a study that used very different test formats, for example, a cloze test and a question-and-answer task ( r = .29) (Ouellette & Beers, 2010 ). Although these differences are substantial, Muijselaar et al. ( 2017 ) suggest that the relationship between reading and listening comprehension may be confounded due to task-specific demands only when the format of comprehensions tests differ to a large extent. These large format differences include for example whether a test is timed or not, whether longer paragraphs are used or short paragraphs of one or two sentences or whether only one text and question type is used or multiple different text and question types. Therefore, it is important to use reading and listening comprehension tests with the same format when exploring the relationship between the two comprehension types. The few studies that used the same task format to investigate the relationship between reading and listening comprehension found that the two comprehension types correlate highly, but not perfectly (Diakidoy et al., 2005 ; Vellutino et al., 2007 ), indicating that reading and listening comprehension might overlap to some extent, but are not entirely the same. Some aspects of the reading comprehension and listening comprehension processes might entail an overlapping general comprehension process, but other aspects might be distinctive modality-specific processes.

To understand which parts of the comprehension process are general and which parts are modality-specific, it might be fruitful to investigate the foundational skills of reading and listening comprehension. Some foundational skills could be necessary to create a situation model, regardless of the modality in which the information is presented. However, each comprehension type might also rely on several modality-specific skills that help processing information presented in a specific modality. To illustrate, the foundational skill word reading fluency might be vital for reading comprehension, but not for listening comprehension. Similarly, because listeners cannot ‘relisten’ a passage whereas readers are able to reread a paragraph, attentional and memory skills might be of more importance for listening comprehension than to reading comprehension. As of yet, no studies have investigated shared, domain-general and unique, modality-specific underlying skills of reading and listening comprehension in tandem. Moreover, studies on the underlying skills of reading or listening comprehension have often assessed a combination of foundational skills (skills that form building blocks for more complex abilities, such as memory, attention, vocabulary) and higher-level skills (inference making, comprehension monitoring) as predictors. Because higher-level skills could obscure effects of the foundational skills, a study into the foundational skills contributing to spoken and written comprehension is necessary.

For reading comprehension, it has been shown that word reading fluency and listening comprehension are important predictors (Hoover & Gough, 1990 ). In addition, vocabulary has been found to be a contributor to reading comprehension (Cromley & Azevedo, 2007 ; Swart et al., 2017 ). The relation between vocabulary and reading comprehension is especially strong in poor comprehenders. Their comprehension might depend more on basic vocabulary knowledge compared to those with good comprehension abilities, who already have a more extensive vocabulary (Van den Bosch, Segers, & Verhoeven, 2018 ). Studies that are framed according to the simple view of reading sometimes take vocabulary as a proxy for linguistic comprehension (Muijselaar & De Jong, 2015 ) instead of the more standard proxy listening comprehension (LARRC, 2017 ). This suggests that vocabulary and listening comprehension are equally good measures of the general linguistic comprehension construct in the simple view of reading. Two different patterns of findings have been reported: an additional contribution of vocabulary to reading comprehension after controlling for listening comprehension (Foorman, Herrera, Petscher, Mitchell, & Truckenmiller, 2015 ; Protopapas et al., 2012 ; Tunmer & Chapman, 2012 ) or not (De Jong & Van der Leij, 2002 ). The results of these studies thus question whether measures for vocabulary and listening comprehension can be used interchangeably to operationalize general linguistic comprehension. Therefore, in this study, the role of vocabulary and listening comprehension as contributors to reading comprehension is also examined.

Other foundational skills that have been related to reading comprehension are memory processes, such as short-term memory, working memory and updating. It seems that especially working memory of verbal information contributes to reading comprehension (Carretti, Borella, Cornoldi, & De Beni, 2009 ; Daneman & Merikle, 1996 ; Van den Bosch et al., 2018 ). Especially in good comprehenders working memory seems to be a strong contributor (Van den Bosch et al., 2018 ). Mixed findings have been reported for attention: whereas Cutting and Scarborough ( 2006 ) did not find a contribution of attention as rated by parents, Cain and Bignell ( 2014 ) found that children with attention difficulties as rated by teachers performed more poorly on reading comprehension. Based on previous studies, it can be concluded that the effects of memory and attention measures on reading comprehension are not consistent. Moreover, there are no studies that simultaneously assess the contribution of word reading fluency and vocabulary, as well as the contribution of memory and attentional processes to reading comprehension.

With respect to listening comprehension, vocabulary is known to be one of the most important predictors (Cain & Oakhill, 2014 ; Florit, Roch, & Levorato, 2011 ; Hagtvet, 2003 ; Tompkins, Guo, & Justice, 2013 ). Findings on the role of verbal short-term memory and verbal working memory have either shown that verbal working memory contributes to listening comprehension outcome (Florit, Roch, Altoè, & Levorato, 2009 ; Potocki, Ecalle, & Magnan, 2013 ; Tighe, Spencer, & Schatschneider, 2015 ), or show no clear-cut contribution (Alonzo, Yeomans-Maldonado, Murphy, & Bevens, 2016 ; Kim, 2016 ). Effects of verbal memory seem to decline when children get older (Chrysochoou & Bablekou, 2011 ; Tighe et al., 2015 ). Furthermore, Currie and Cain ( 2015 ) found that effects of verbal short-term and verbal working memory on listening comprehension were fully mediated by vocabulary. Concerning short-term memory, some studies have reported an effect on listening comprehension after controlling for vocabulary (Florit et al., 2009 ), whereas others found no effects of short-term memory on reading comprehension at all (Potocki et al., 2013 ). Additionally, visual memory may be important for listening comprehension if the task not only requires listening, but also provides information through the visual modality (such as television comprehension as in Kendeou, Bohn-Gettler, White, and Van Den Broek ( 2008 )).

Only a few studies have examined the effects of attentional processes or inhibition on listening comprehension. Kim ( 2016 ) reported no effect of attention on listening comprehension after several foundational and higher order skills were taken into account. Inhibition, however, was found to be a direct predictor of listening comprehension (Kim & Phillips, 2014 ). Attention-related measures might have a stronger effect on listening comprehension than on reading comprehension, due to the fleeting nature of the presentation of the information and the fact that comprehenders cannot control the pace of information themselves.

To sum up, the relationship between reading and listening comprehension is not yet fully understood. In this study, the relationship between reading and listening comprehension is explored to investigate whether it is justifiable to view reading and listening comprehension as one general comprehension skill without any modality-specific aspects, as has been done in theory and educational practice. Firstly, the overlap between the two comprehension types is examined to understand how general or modality-specific the reading and listening comprehension processes are. For this aim the explained variance of one comprehension type in the other will be analyzed. Furthermore, shared and unique cognitive contributors of reading and listening comprehension are sought to understand which parts of the comprehension process are domain-general and modality-specific. As such, the contributions of several foundational skills (word reading fluency, vocabulary, verbal short term memory, verbal working memory, visual memory, sustained aural attention, and inhibition) are analyzed. Lastly, the practice within the framework of the simple view of reading of using either listening comprehension or vocabulary as a proxy for general linguistic comprehension is studied. For this reason, it will be analyzed whether listening comprehension and vocabulary contribute uniquely to reading comprehension.

To ensure that the relationship between reading and listening comprehension is not affected by task-specific effects of the different task formats, reading comprehension and listening comprehension tasks with the same testing format are used. Moreover, an ecologically valid audio-visual rather than pure audio listening comprehension task is used. Listening comprehension in audio-only listening comprehension tasks, as used in previous studies, is not entirely similar to listening comprehension in daily life, in which not only audio but also visual information as well is involved. There is evidence that memory and the construction of a situation model are superior for audio-visual compared to audio-only material (Gibbons, Anderson, Smith, Field, & Fischer, 1986 ; Wannagat, Waizenegger, Hauf, & Nieding, 2018 ). Therefore, the present study uses reading and listening comprehension tasks with the same task formats and that are presented in ecologically valid modalities (in this case, the written versus audio- visual rather than audio-only modality).

It is hypothesized that a strong relationship between reading comprehension and listening comprehension is found in our sample, since the relationship seems to be strong in even beginning readers of a transparent language. We expect the overlap to be substantial: that reading comprehension explains a considerable amount of variance in listening comprehension and vice versa, since the comprehension process in which the situation model is created, is theoretically viewed as a general process, with little modality-specific effects. Full overlap is not expected, because it is thought that some aspects of the modality of the input will affect the comprehension process. Regarding reading comprehension, it is expected that especially word reading fluency, vocabulary and memory skills (verbal short-term memory, verbal working memory, and visual memory) will contribute. For listening comprehension, it is hypothesized that vocabulary, memory skills (verbal short-term memory, verbal working memory, and visual memory) and attentional skills are important contributors, but not word reading fluency. Concerning the relationship between vocabulary and listening comprehension, and reading comprehension, it is expected that these skills both contribute uniquely to reading comprehension, which would mean that they should not solely be used as a proxy of general linguistic comprehension.

Participants

In total 85 children with a mean age of 8;7 years ( SD = 8 months) participated (52 girls), including 35 second graders (age: M = 8 years, SD = 6 months; 25 girls) and 50 third graders (age: M = 8;11 years, SD = 6 months; 27 girls). Dutch was the preferred language of 86% of the children. Three children were diagnosed with dyslexia and sixteen children had followed speech therapy.

- Reading comprehension

Reading comprehension was measured with a standardized reading comprehension task (Cito, 2009 , 2014 ) from the LOVS test battery (Leerling-en OnderwijsVolgSysteem [System for the Longitudinal Assessment of School Achievement]) which consists of several standardized tests for first to sixth graders and is regularly used in Dutch education. The test has two parts, each lasting for 40–50 minutes and containing five to nine texts and 20–30 multiple-choice questions. Children were asked to read age-appropriate narrative and expository texts and answer corresponding multiple-choice questions. Two types of questions were present: literal questions, which questioned information literally stated in the texts, and inferential questions requiring children to combine information explicitly stated in the text with information not stated explicitly in the text. The questions had a four-option or true/false multiple-choice format. For the analyses, raw scores were converted to skill scores. In the year the present study was carried out, Cito introduced new skill score scales and formulas in second grade. The second grade skill scores were transformed to the same scale as the third grade skill scores using a formula provided by Cito. The reliability of the task is good (α = .86 in second grade; α = .89 in third grade) (Feenstra, Kamphuis, Kleintjes, & Krom, 2010 ).

- Listening comprehension

Listening comprehension was tested through a standardized listening comprehension task (Cito, 2011 ) also from the LOVS test battery, which is divided in three separate test sessions. Children were required to listen to and watch selected audio-visual fragments and to answer corresponding multiple-choice questions on an answer sheet. In total, five to six age-appropriate narrative and expository fragments were presented. Children were first shown the whole fragment, after which it was segmented in shorter fragments that lasted about 6 minutes each with the four-choice multiple-choice questions in-between. In total the test consisted of 30–32 multiple-choice questions. These questions were presented aurally and visually (on the screen), but were not shown on the child’s answer sheet. The answer options were presented aurally and visually on the answer sheet, but not on the screen. Similar to the reading comprehension test questions were either literal, enquiring information explicitly said in the audio-visual fragments, or inferential, which required children to combine explicit information provided in the fragments with not explicitly presented information. For the analyses, raw scores were converted to skill scores. The reliability of the test was sufficient (Cronbach’s α is .74 in second grade and .77 in third grade) according to the manual (Cito, 2011 ).

Word reading fluency

Word reading fluency was measured with the One-Minute-Task (Brus & Voeten, 1973 ). Children were asked to read aloud as many words as they could in one minute. The task consists of 116 words increasing in difficulty. The final score was calculated by subtracting the number of errors from the number words read. According to the manual, mean parallel-test reliability was high ( r = .90 between form A and B) (Van Den Bos, Spelberg, Scheepsma, & De Vries, 1994 ).

The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) III-NL (Dunn, Dunn, & Schlichting, 2005 ) was used to measure receptive vocabulary. Children were shown four different pictures and were asked to point at the one matching the target word. The PPVT is adaptive to the level vocabulary of the child. Testing and scoring proceeded according to the manual. The final score represents the number of words correctly identified. According to the manual (“PPVT-4 Publication Summary Form,” 2007 ), test–retest reliability was high ( r = .93).

Verbal short-term and verbal working memory

Verbal short-term memory and verbal working memory were measured with the digit span forwards and backwards task from the WISC-III-NL (Wechsler et al., 2002 ). Digit span forwards taps children’s ability to repeat an increasing string of digits read aloud by the test leader. Testing proceeded according to the manual. The final score was the number of correctly repeated digit strings with a maximum score of 16. In the digit span backwards task, children had to repeat increasing strings of digits in reverse order. Testing proceeded according to the manual. The maximum score is 14. Cronbach’s α for the tasks together is .56 according to the manual (Wechsler et al., 2002 ).

Visual memory

The Benton Visual Retention Test (Sivan, 1992 ) was used to measure visual memory. Children were presented with a sheet with a 2D geometrical drawing for 10 seconds. They were asked to reproduce the drawing from memory with pencil and paper. Drawings were presented in ascending order of difficulty. The final score was the number of correct responses minus the number of errors. Inter-rater reliability is high ( r = .95 to .97 according to the manual (Sivan, 1992 )).

Sustained aural attention

A subtest of the NEPSY-II-NL (Zijlstra, Kingma, Swaab, & Brouwer, 2010 ) was used to measure sustained aural attention. In this task, children received a sheet with a red, blue, yellow and black circle and listened to a recording of a string of 180 Dutch words. The words consisted of 30 target words “rood” (red), 34 distraction words (the other colour names: “blauw” (blue), “geel” (yellow) and “zwart” (black)) and filler words (common Dutch mono- and bisyllabic words). The words were presented with a speed of one word per 2 seconds. There was a pause of 2 seconds between each word. Upon hearing the target word “rood” (red), children were required to point at the red circle on the sheet with coloured circles. Scoring proceeded according to the manual. An error was marked when a child did not respond to a target word within 2 seconds, or responded to a distraction or filler word. The final score was the number of errors subtracted from number of correct responses, with a maximum score of 30. Test–retest reliability is r = .42 for children aged 7–8 and r = .62 for children aged 9–10 (Brooks, Sherman, & Strauss, 2009 ). According to the manual, test–retest reliability is .65 (Korkman, Kirk, & Kemp, 2007 ), and construct validity seems to be low (Egberink & Vermeulen, 2009 -2018).

Inhibition was measured using the Stroop task (Golden & Freshwater, 1978 ). For the first sheet, children had to read 100 written colour names as quickly as possible. For the second sheet, with 100 coloured rectangles, children were asked to name the colours as quickly as possible. For the third sheet, containing 100 colour names printed in a non-corresponding colour, children had to name the colours as quickly as possible, thus avoid reading the words. The final score was the time in seconds needed to read the second sheet subtracted from the time needed for the third sheet. Test–retest reliability is r = .67 (Franzen, Tishelman, Sharp, & Friedman, 1987 ).

The tests, except for the reading comprehension task, were part of a larger test battery administered in April and May by five trained test assistants. The reading comprehension test was already administered by the school in February as part of the normal curriculum. The reading comprehension tests consist of two parts, each lasting for 40–50 minutes. The other tests were administered in four 45-minutes lasting testing sessions. Three in-class testing sessions included a part of the listening comprehension test. Each of the three listening comprehension parts had a duration of 30 minutes. The foundational skill tasks were administered in an individual test session. In a fixed order, the tasks for memory, sustained aural attention, inhibition, vocabulary and visual memory were administered. This session took approximately 40 minutes.

Data screening and descriptive statistics

There were no missing data. Five outlier scores were recoded to deviate exactly three standard deviations from the mean. Descriptive statistics of the outcome measures are presented in Table 1 . The data was normally distributed, as skewness and kurtosis were below ± 3 and ± 10 respectively (Kline, 2011 ). Correlations among all variables are displayed in Table 2 . Reading comprehension and listening comprehension were highly correlated. Word reading fluency was highly correlated with reading comprehension and moderately with listening comprehension. The relations of vocabulary with reading and listening comprehension were respectively moderate to high. For all other variables, correlations with comprehension were low to moderate.

Regression analyses

To examine the relationship between reading and listening comprehension, the overlap between the two was analyzed to find out whether comprehension is a general skill, or has modality-specific aspects (Table 3 ). In the regression analyses, grade was first entered as a control variable. Next, the opposite comprehension type was added as a contributor. Both comprehension types contributed significantly to the model. For reading comprehension , listening comprehension explained 40% of the variance. Listening comprehension was a significant contributor to reading comprehension (β = .70). For reading comprehension, the final model explained 41% of the variance. Regarding listening comprehension , reading comprehension explained 34% of the variance in listening comprehension and reading comprehension contributed significantly to listening comprehension (β = .58). The final model explained 51% of the variance in listening comprehension.

The relationship between reading and listening comprehension was furthermore explored by examining the unique (modality-specific) and shared (general) foundational contributors (word reading fluency, vocabulary, verbal short-term memory, verbal working memory, visual memory, sustained aural attention and inhibition) to both comprehension types (Table 4 ). Again, grade was entered as a first step. Then, all foundational skills were added simultaneously. In the hierarchical model for reading comprehension , word reading fluency (β = .56) and vocabulary (β = .48) were significant contributors. Of the variance in reading comprehension, 61% was explained. Regarding listening comprehension , again word reading fluency as a significant contributor (β = .25), as well as vocabulary (β = .50). This model explained 49% of the variance in listening comprehension. None of the other foundational skills contributed significantly to reading nor to listening comprehension.

Lastly the practice within the framework of the simple view of reading of using either listening comprehension or vocabulary as a proxy for general linguistic comprehension was examined by analyzing the unique contributions of word reading fluency, and especially listening comprehension and vocabulary (Table 5 ). First grade was entered in the model. Next, word reading fluency, listening comprehension and vocabulary were added simultaneously. Word reading was found to be a significant contributor (β = .49). More importantly, both listening comprehension (β = .37) and vocabulary (β = .27) were unique contributors to reading comprehension. The model explained 63% of the variance in reading comprehension.

The present study was aimed at understanding the relationship between reading and listening comprehension to investigate whether comprehension is a general skill or whether it has modality-specific aspects. In both theory and the educational practice, comprehension is treated as a general process with little room for modality-specific effects. To evaluate this assumption, three questions were addressed. Firstly, the overlap between the two comprehension types in terms of explained variance of one type in the other was investigated, to understand whether comprehension in these two modalities overlaps and thus is a general skill, or whether they are partly distinct comprehension skills. Secondly, shared and unique foundational cognitive contributors (word reading fluency, vocabulary, verbal short-term memory, verbal working memory, visual memory, sustained aural attention, and inhibition) of reading and listening comprehension were explored to assess which subskills and sub processes of comprehension are in fact general or modality-specific. Thirdly, since it is common practice in studies that use the simple view of reading framework to operationalize general linguistic comprehension with either a listening comprehension task or a vocabulary task, it was studied whether these two skills contribute uniquely to reading comprehension.

About 34 and 40% of the variance in either comprehension type was explained by the other comprehension type. These results imply that the situation model built through comprehension of written and spoken material partly taps a general comprehension process. Moreover, both vocabulary and word reading fluency were found to be shared subskills of both reading and listening comprehension. Thus, during this general comprehension process, the foundational subskill vocabulary seems essential. This might be due to the fact that vocabulary is a key skill for constructing and possessing background knowledge, as well as for inference making. These are components that are required for constructing the situation model: comprehenders need to integrate pieces of information in the text with each other and with their background knowledge (Kintsch & Rawson, 2005 ) in a coherent and cohesive manner (Van den Broek, Risden, & Husebye-Hartmann, 1995 ). Having a vast semantic network helps in using interrelations between different concepts while inferring the meaning of words or the relation between words in a text (Cain & Oakhill, 2014 ; Perfetti, Yang, & Schmalhofer, 2008 ). It seems that the part of the reading and listening comprehension process in which integration takes place and inferences are made through the activation of the vocabulary, is a general comprehension process that transcends modalities.

However, this study also shows that the majority of the variance in a comprehension type cannot be explained by the opposite comprehension type. This part of the reading and listening comprehension process is modality-specific and cannot be subsumed under a general comprehension skill. The findings of this study could not pinpoint as to which processes might be modality-specific, since none of the foundational skills contributed uniquely to either reading or listening comprehension. Correlations revealed indications of an important modality-specific subskill for listening comprehension, as attention measures only correlated significantly with listening comprehension. Due to the fleeting nature of auditory information, attention might be an important subskill of listening comprehension to keep up with the pace of the speaker and process all information conveyed (Kim & Phillips, 2014 ).

Unexpectedly, word reading fluency was found to contribute not only to reading comprehension, but also to listening comprehension. Word reading fluency was a likely candidate for a modality-specific subskill of reading comprehension on the basis of the simple view of reading (Hoover & Gough, 1990 ). Instead, it was found to be a shared contributor to both reading and listening comprehension. The listening comprehension task used in the present study also contained (limited) written information, allowing for strategic reading of the questions and the answers. The information from which the children had to infer the answers was, however, not presented orthographically. Thus, word reading fluency can be seen as a general comprehension skill only whilst comprehending the questions and answers in our task, but not whilst comprehending the information from which the answers had to be derived. Therefore, the finding that word reading fluency is a shared contributor to both reading and listening comprehension will probably not generalize to studies that use pure listening comprehension tasks.

Together, the results of the present study indicate that part of the reading and listening comprehension process taps a general comprehension skill that operates regardless of modality. Vocabulary might aid in understanding the relations between words and clauses, improving integration of the text and aiding in situation model construction. Importantly, conflicting with the status of modality-specific aspects of comprehension in some comprehension theories (Gernsbacher et al., 1990 ; Hoover & Gough, 1990 ) and the educational practice, in this study a distinct part of the reading and listening comprehension process seems to be modality-specific. Similar to Kintsch and Van Dijk ( 1978 ) we cannot yet pinpoint the exact modality-specific aspects of reading and listening comprehension, or the subskills that contribute to these specific processes, since in this study none of the foundational skills contributed uniquely to either reading or listening comprehension. This might be due to the contemporary measures of these skills. In the past decade there has been a growing consensus that measures of executive functions (amongst which memory and attention) lack ecological validity (Burgess et al., 2006 ; Wallisch, Little, Dean, & Dunn, 2017 ). This means that, for example, a test measuring sustained aural attention does not capture sustained aural attention as it occurs during the comprehension process. Thus, memory and attentional skills might still influence reading and listening comprehension, despite not surfacing as contributors on the basis of the tests used in this study. Furthermore, previous studies did find a contribution of attention to reading comprehension, but only when attention was rated by teachers (Cain & Bignell, 2014 ). When rated by parents (Cutting & Scarborough, 2006 ) or measured with a neuropsychological measure, such as in the present study, no such associations are found. One avenue for further research is to use other types of measures in tandem with traditional executive functions tasks to capture executive functions in a more ecologically valid way. For example, teacher ratings of attention might add an extra dimension of information to a child’s attentional skills in the ‘real world’ (Cain & Bignell, 2014 ; Wallisch et al., 2017 ). Additionally, physiological indexes can be used as measures to assess even more basic mechanisms related to executive functions (see for instance Scrimin, Patron, Florit, Palomba, & Mason, 2017 ).

A third approach in studying the relationship between reading and listening comprehension was to examine whether listening comprehension and vocabulary are the same contributors to reading comprehension or whether they contribute separately. Studies into the simple view of reading tend to use either listening comprehension or vocabulary as a proxy of general linguistic comprehension. For example, Protopapas et al. ( 2012 ) previously suggested that vocabulary is a better indicator of the print-independent component of reading comprehension than listening comprehension, since vocabulary measures are often more reliable than measures of listening comprehension. Our study, however, showed that it is not the case that the more reliable vocabulary measure explained all variance in reading comprehension, and that listening comprehension explained none of the variance. Vocabulary measures should thus not be used as a sole proxy for general linguistic comprehension. Likewise, because vocabulary also explained additional variance in reading comprehension over listening comprehension, listening comprehension should neither be used as sole operationalization of general linguistic comprehension. This interpretation is also confirmed by studies in the English language with larger samples using structural equation modeling (Foorman et al., 2015 ; Tunmer & Chapman, 2012 ) in which measures of vocabulary and listening comprehension loaded separately on a latent construct which could be termed ‘general linguistic comprehension’. The present study implies that this latent structure is also present in more transparent languages, such as Dutch. With this latent structure in mind, the findings of presented study support the simple view of reading (Hoover & Gough, 1990 ) in that reading ability is predicted by decoding ability (word reading fluency in the present study) and linguistic comprehension (comprising of listening comprehension and vocabulary).

There are at least five limitations to this study. First, the results of this study might be partly task-specific. Muijselaar et al. ( 2017 ) found that the relationship between reading and listening comprehension can vary when two tests differ largely (for example, when one test is timed where the other is not). We tried to overcome this by using a reading and listening comprehension test with the same task format that comprised multiple text types and question types, consisted of longer paragraphs and was not timed. Thus, the results of this study are generalizable to situations in which similar comprehension tests are administered. Comparing our results to findings obtained with a comprehension task with a different task format, that for example consists of paragraphs of only one or two sentences, or is timed, must be done with great care. Second, related to the previous limitation, generalizing the findings of the present study in Dutch to studies with children speaking a different native language should be done with caution. Especially in orthographic opaque languages (such as English) children learn to read fluently at a later age than children whose native language has a more transparent orthography (such as Dutch) (Ellis et al., 2004 ; Florit & Cain, 2011 ) This could mean that the contribution of reading comprehension to listening comprehension and vice versa could differ in an opaque orthography, as could the contribution of word reading fluency to both comprehension measures. Third, we could only determine concurrent contributors on the basis of these cross-sectional data. A longitudinal and cross-lagged design is needed to allow conclusions about predictors of reading and listening comprehension. A fourth limitation is that our selection of foundational skills was not exhaustive. Future studies should also include grammar, since syntactic knowledge has been found to contribute to both reading comprehension (Goff, Pratt, & Ong, 2005 ; Hagtvet, 2003 ; Van den Bosch et al., 2018 ) as well as listening comprehension (Hagtvet, 2003 ; Kim, 2016 ). Furthermore, since the construct of vocabulary has many distinct aspects (Cain & Oakhill, 2014 ; Swart et al., 2017 ) such as vocabulary breadth, vocabulary depth and semantic relatedness, it would be worthwhile to investigate whether these different measures of vocabulary contribute differently to reading and listening comprehension. Fifth, the effect of grade in the model with reading comprehension was negative. This negative effect is probably due to suppression: in a model with grade as the only predictor of reading comprehension, the effect of grade was positive. The effects of the other variables did not change drastically when removing grade from the regression models reported in Tables 3 and 4 : only inhibition became just significant (from p =.08 to p = .04) but the change in strength was negligible (from β = .14 to β = .17).

Despite these limitation, this study has implications for theory and practice. Theoretically, the results of this study indicate that reading and listening comprehension are not two versions of the same general comprehension skill as proposed by Gernsbacher et al. ( 1990 ). Instead, only a part of the reading and listening comprehension process is a general comprehension process, with vocabulary being an important sub skill, whereas other parts of the comprehension process are modality-specific. Thus, in line with Kintsch and Van Dijk ( 1978 ), the comprehension process will differ due to modality-specific demands. As for now, however, we cannot yet identify these modality-specific processes and subskills. This notion that acknowledges modality effects in comprehension research, is both important and necessary, since the lack of acknowledgement has led to confoundedness and difficulties in the interpretation of results within the framework of the ‘old’ comprehension theories. One example, being addressed in this study, is that of the simple view of reading, in which general linguistic comprehension has been operationalized as listening comprehension, whilst not taking modality effects into account, or vocabulary, a different construct. Based on the results of this study, neither listening comprehension nor vocabulary should be used as sole proxies of general linguistic comprehension in the simple view of reading, but both measures should be used in tandem to operationalize this construct more adequately.

Practically, the interpretation that reading and listening comprehension have both general aspects as well as modality-specific aspects should be considered in education. A child’s listening comprehension aptitude should be monitored alongside reading compression, and if necessary, specific interventions need to be offered to help the child overcome these specific difficulties. For interventions that tackle modality-specific reading and listening comprehension deficits, more research is needed to pinpoint modality-specific comprehension processes and subskills. If a child faces difficulty with both reading and listening comprehension, a vocabulary training might help it to overcome this difficulty with general comprehension. This study calls for a reconsideration of modality-specific aspects of reading and listening comprehension in both research and the educational practice.

Alonzo, C. N., Yeomans-Maldonado, G., Murphy, K. A., & Bevens, B. (2016). Predicting second grade listening comprehension using prekindergarten measures. Topics in Language Disorders, 36 (4), 312–333. https://doi.org/10.1097/tld.0000000000000102 .

Article Google Scholar

Bingol, M. A., Celik, B., Yildiz, N., & Mart, C. T. (2014). Listening comprehension difficulties encountered by students in second language learning class. Journal of Educational and Instructional Studies in the World, 4 (4), 1–6.

Google Scholar

Brooks, B. L., Sherman, E. M. S., & Strauss, E. (2009). NEPSY-II: A developmental neuropsychological assessment, Second Edition. Child Neuropsychology, 16 (1), 80–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297040903146966 .

Brus, B. T., & Voeten, M. (1973). Een-minuuttest, vorm A en B, verantwoording en handleiding [One-minute-test, form A and B, justification and manual] . Nijmegen: Berkhout.

Burgess, P. W., Alderman, N., Forbes, C., Costello, A., Coates, L. M.-A., Dawson, D. R., et al. (2006). The case for the development and use of “ecologically valid” measures of executive function in experimental and clinical neuropsychology. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 12 (2), 194–209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617706060310 .

Cain, K., & Bignell, S. (2014). Reading and listening comprehension and their relation to inattention and hyperactivity. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84 (1), 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12009 .

Cain, K., & Oakhill, J. (2014). Reading comprehension and vocabulary: Is vocabulary more important for some aspects of comprehension? L’Année Psychologique, 114 (4), 647–662. https://doi.org/10.4074/s0003503314004035 .

Cain, K., Oakhill, J., & Bryant, P. (2000). Investigating the causes of reading comprehension failure: The comprehension-age match design. Reading and Writing, 12 (1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008058319399 .

Carretti, B., Borella, E., Cornoldi, C., & De Beni, R. (2009). Role of working memory in explaining the performance of individuals with specific reading comprehension difficulties: A meta-analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 19 (2), 246–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2008.10.002 .

Catts, H. W., Adlof, S. M., Hogan, T. P., & Weismer, S. E. (2005). Are specific language impairment and dyslexia distinct disorders? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48 (6), 1378–1396. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2005/096) .

Chrysochoou, E., & Bablekou, Z. (2011). Phonological loop and central executive contributions to oral comprehension skills of 5.5 to 9.5 years old children. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25 (4), 576–583. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1723 .

Cito. (2009). Handleiding. Cito Volgsysteem 2.0. Primair onderwijs. Begrijpend lezen [Manual. Cito tracking system. Primary education Reading comprehension] . Arnhem: Cito.

Cito. (2011). Handleiding. Cito Volgsysteem. Primair onderwijs. Begrijpend luisteren [Manual. Cito tracking system. Primary education Listening comprehension] . Arnhem: Cito.

Cito. (2014). Handleiding. Cito Volgsysteem 3.0. Primair onderwijs. Begrijpend lezen [Manual. Cito tracking system. Primary education Reading comprehension] . Arnhem: Cito.

Cromley, J. G., & Azevedo, R. (2007). Testing and refining the direct and inferential mediation model of reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99 (2), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.311 .

Currie, N. K., & Cain, K. (2015). Children’s inference generation: The role of vocabulary and working memory. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 137, 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2015.03.005 .

Cutting, L. E., & Scarborough, H. S. (2006). Prediction of reading comprehension: Relative contributions of word recognition, language proficiency, and other cognitive skills can depend on how comprehension is measured. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10 (3), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr1003_5 .

Daneman, M., & Merikle, P. M. (1996). Working memory and language comprehension: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3 (4), 422–433. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03214546 .

De Jong, P. F., & Van der Leij, A. (2002). Effects of phonological abilities and linguistic comprehension on the development of reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 6 (1), 51–77. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532799XSSR0601_03 .

Diakidoy, I.-A. N., Stylianou, P., Karefillidou, C., & Papageorgiou, P. (2005). The relationship between listening and reading comprehension of different types of text at increasing grade levels. Reading Psychology, 26 (1), 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710590910584 .

Dunn, L. M., Dunn, L. M., & Schlichting, J. E. P. T. (2005). Peabody picture vocabulary test-III-NL . Amsterdam: Harcourt Test Publishers.

Egberink, I. J. L., & Vermeulen, C. S. M. (2009–2018). COTAN Documentatie . Amsterdam: BOOM Uitgevers.

Ellis, N. C., Natsume, M., Stavropoulou, K., Hoxhallari, L., Van Daal, V. H. P., Polyzoe, N., et al. (2004). The effects of orthographic depth on learning to read alphabetic, syllabic, and logographic scripts. Reading Research Quarterly, 39 (4), 438–468. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.39.4.5 .

Feenstra, H., Kamphuis, F., Kleintjes, F., & Krom, R. (2010). Wetenschappelijke verantwoording. Begrijpend lezen voor groep 3 tot en met 6 [Scientific justification of reading comprehension tests for Grades 5 to 8] . Arnhem: Cito.

Florit, E., & Cain, K. (2011). The simple view of reading: Is it valid for different types of alphabetic orthographies? Educational Psychology Review, 23 (4), 553–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9175-6 .

Florit, E., Roch, M., Altoè, G., & Levorato, M. C. (2009). Listening comprehension in preschoolers: The role of memory. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27 (4), 935–951. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151008X397189 .

Florit, E., Roch, M., & Levorato, M. C. (2011). Listening text comprehension of explicit and implicit information in preschoolers: The role of cerbal and inferential skills. Discourse Processes, 48 (2), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2010.494244 .

Foorman, B. R., Herrera, S., Petscher, Y., Mitchell, A., & Truckenmiller, A. (2015). The structure of oral language and reading and their relation to comprehension in Kindergarten through Grade 2. Reading and Writing, 28 (5), 655–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9544-5 .

Franzen, M. D., Tishelman, A. C., Sharp, B. H., & Friedman, A. G. (1987). An investigation of the test-retest reliability of the stroop colorword test across two intervals. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 2 (3), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/2.3.265 .

Gernsbacher, M. A., Varner, K. R., & Faust, M. E. (1990). Investigating differences in general comprehension skill. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16 (3), 430–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.16.3.430 .

Gibbons, J., Anderson, D. R., Smith, R., Field, D. E., & Fischer, C. (1986). Young children’s recall and reconstruction of audio and audiovisual narratives. Child Development, 57 (4), 1014–1023. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130375 .

Goff, D. A., Pratt, C., & Ong, B. (2005). The relations between children’s reading comprehension, working memory, language skills and components of reading decoding in a normal sample. Reading and Writing, 18 (7), 583–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-004-7109-0 .

Goh, C. C. M. (2000). A cognitive perspective on language learners’ listening comprehension problems. System, 28 (1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00060-3 .

Golden, C. J., & Freshwater, S. M. (1978). Stroop color and word test . Chicago, IL: Stoelting.

Hagtvet, B. E. (2003). Listening comprehension and reading comprehension in poor decoders: Evidence for the importance of syntactic and semantic skills as well as phonological skills. Reading and Writing, 16 (6), 505–539. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025521722900 .

Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing, 2 (2), 127–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00401799 .

Kendeou, P., Bohn-Gettler, C., White, M. J., & Van Den Broek, P. (2008). Children’s inference generation across different media. Journal of Research in Reading, 31 (3), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2008.00370.x .

Kim, Y.-S. G. (2016). Direct and mediated effects of language and cognitive skills on comprehension of oral narrative texts (listening comprehension) for children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 141, 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2015.08.003 .

Kim, Y.-S. G., & Phillips, B. (2014). Cognitive correlates of listening comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 49 (3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.74 .

Kintsch, W., & Rawson, K. A. (2005). Comprehension. In M. J. Snowling & C. Hulme (Eds.), The science of reading: A handbook . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Kintsch, W., & Van Dijk, T. A. (1978). Toward a model of text comprehension and production. Psychological Review, 85 (5), 363–394. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.85.5.363 .

Kline, R. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Korkman, M., Kirk, U., & Kemp, S. (2007). NEPSY—Second edition (NEPSY-II) . San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment.

LARRC. (2017). Oral language and listening comprehension: Same or different constructs? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60 (5), 1273–1284. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_jslhr-l-16-0039 .

Mangen, A. (2016). The digitization of literary reading. Orbis Litterarum, 71 (3), 240–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/oli.12095 .

McInnes, A., Humphries, T., Hogg-Johnson, S., & Tannock, R. (2003). Listening comprehension and working memory are impaired in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder irrespective of language impairment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31 (4), 427–443. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1023895602957 .

McNamara, D. S., & Magliano, J. (2009). Chapter 9: Toward a comprehensive model of comprehension. In B. H. Ross (Ed.), Psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 51, pp. 297–384). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Chapter Google Scholar

Mommers, F. C. (2007). Goed leesonderwijs: wat er echt toe doet! Journal of the Southwest, 91 (7), 20–22.

Muijselaar, M. M. L., & De Jong, P. F. (2015). The effects of updating ability and knowledge of reading strategies on reading comprehension. Learning and Individual Differences, 43, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.011 .

Muijselaar, M. M. L., Swart, N. M., Steenbeek-Planting, E. G., Droop, M., Verhoeven, L., & de Jong, P. F. (2017). The dimensions of reading comprehension in Dutch children: Is differentiation by text and question type necessary? Journal of Educational Psychology, 109 (1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000120 .

OECD. (2010). PISA 2009 results: What students know and can do: student performance in reading, mathematics and science (Vol. I). Paris: OECD.

Book Google Scholar

Ouellette, G., & Beers, A. (2010). A not-so-simple view of reading: How oral vocabulary and visual-word recognition complicate the story. Reading and Writing, 23 (2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-008-9159-1 .

Perfetti, C., Yang, C.-L., & Schmalhofer, F. (2008). Comprehension skill and word-to-text integration processes. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22 (3), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1419 .

Potocki, A., Ecalle, J., & Magnan, A. (2013). Narrative comprehension skills in 5-year-old children: Correlational analysis and comprehender profiles. The Journal of Educational Research, 106 (1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2012.667013 .

PPVT-4 Publication Summary Form. (2007). Retrieved from www.pearsonassessments.com/pdf/pubsum/ppvt4.pdf .

Protopapas, A., Simos, P. G., Sideridis, G. D., & Mouzaki, A. (2012). The components of the simple view of reading: A confirmatory factor analysis. Reading Psychology, 33 (3), 217–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2010.507626 .

Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8- to 18-year-olds . Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Scrimin, S., Patron, E., Florit, E., Palomba, D., & Mason, L. (2017). The role of cardiac vagal tone and inhibitory control in pre-schoolers’ listening comprehension. Developmental Psychobiology, 59 (8), 970–975. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21576 .

Sivan, A. B. (1992). Benton visual retention test . San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Spörer, N., & Brunstein, J. C. (2009). Fostering the reading comprehension of secondary school students through peer-assisted learning: Effects on strategy knowledge, strategy use, and task performance. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34 (4), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2009.06.004 .

Swart, N. M., Muijselaar, M. M. L., Steenbeek-Planting, E. G., Droop, M., De Jong, P. F., & Verhoeven, L. (2017). Differential lexical predictors of reading comprehension in fourth graders. Reading and Writing, 30 (3), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-016-9686-0 .

Tighe, E. L., Spencer, M., & Schatschneider, C. (2015). Investigating predictors of listening comprehension in third-, seventh-, and tenth-grade students: a dominance analysis approach. Reading Psychology, 36 (8), 700–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2014.963270 .

Tilstra, J., McMaster, K., Van Den Broek, P., Kendeou, P., & Rapp, D. (2009). Simple but complex: Components of the simple view of reading across grade levels. Journal of Research in Reading, 32 (4), 383–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2009.01401.x .

Tompkins, V., Guo, Y., & Justice, L. M. (2013). Inference generation, story comprehension, and language skills in the preschool years. Reading and Writing, 26 (3), 403–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9374-7 .

Tunmer, W. E., & Chapman, J. W. (2012). The simple view of reading redux: Vocabulary knowledge and the independent components hypothesis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45 (5), 453–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219411432685 .

Van Den Bos, K., Spelberg, H., Scheepsma, A., & De Vries, J. (1994). De Klepel. Vorm A en B. Een test voor de leesvaardigheid van pseudowoorden. Verantwoording, handleiding, diagnostiek en behandeling [The Klepel. Form A and B. A test for reading ability of pseudowords. justification, manual, diagnostics and treatment] . Nijmegen: Berkhout.

Van den Bosch, L. J., Segers, E., & Verhoeven, L. (2018). The role of linguistic diversity in the prediction of early reading comprehension: A quantile regression approach. Scientific Studies of Reading . https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2018.1509864 .

Van den Broek, P., Risden, K., & Husebye-Hartmann, E. (1995). The role of readers’ standards for coherence in the generation of inferences during reading Sources of coherence in reading. (pp. 353-373). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Vellutino, F. R., Tunmer, W. E., Jaccard, J. J., & Chen, R. (2007). Components of reading ability: Multivariate evidence for a convergent skills model of reading development. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11 (1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430709336632 .

Verhoeven, L., & van Leeuwe, J. (2008). Prediction of the development of reading comprehension: A longitudinal study. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22 (3), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1414 .

Wallisch, A., Little, L. M., Dean, E., & Dunn, W. (2017). Executive function measures for children: A scoping review of ecological validity. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 38 (1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449217727118 .

Wannagat, W., Waizenegger, G., Hauf, J., & Nieding, G. (2018). Mental representations of the text surface, the text base, and the situation model in auditory and audiovisual texts in 7-, 9-, and 11-year-olds. Discourse Processes, 55 (3), 290–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2016.1237246 .

Wechsler, D., Kort, W., Compaan, E., Bleichrodt, N., Resing, W., Schittekatte, M., et al. (2002). WISC-III-NL, Handleiding [WISC-III-NL Manual] . Amsterdam: Harcourt Test Publishers.

Zijlstra, H., Kingma, A., Swaab, H., & Brouwer, W. (2010). NEPSY-II-NL . Enschede: Ipskamp.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Wundtlaan 1, 6525 XD, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Behavioural Science Institute, Radboud University, Montessorilaan 3, 6500 HE, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

M. M. L. Muijselaar

Department Research & Development, CED-Groep (Center for Educational Services), Dwerggras 30, 3068 PC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

A. M. Boonstra

Department of Child Development and Education, University of Amsterdam, Nieuwe Achtergracht 127, 1018 WS, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

M. M. L. Muijselaar & E. H. de Bree

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to M. C. Wolf .

Additional information

M. C. Wolf: Part of the work for this article was carried while writing a master’s thesis at the University of Amsterdam.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wolf, M.C., Muijselaar, M.M.L., Boonstra, A.M. et al. The relationship between reading and listening comprehension: shared and modality-specific components. Read Writ 32 , 1747–1767 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9924-8

Download citation

Published : 05 December 2018

Issue Date : 15 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9924-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Foundational skills

- Simple view of reading

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Electron Physician

- v.8(3); 2016 Mar

Active listening: The key of successful communication in hospital managers

Vahid kohpeima jahromi.

1 Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Seyed Saeed Tabatabaee

2 Medical Informatics Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Zahra Esmaeili Abdar

3 Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

Mahboobeh Rajabi

4 Health Services Management Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Introduction

One of the important causes of medical errors and unintentional harm to patients is ineffective communication. The important part of this skill, in case it has been forgotten, is listening. The objective of this study was to determine whether managers in hospitals listen actively.

This study was conducted between May and June 2014 among three levels of managers at teaching hospitals in Kerman, Iran. Active Listening skill among hospital managers was measured by self-made Active Listening Skill Scale (ALSS), which consists of the key elements of active listening and has five subscales, i.e., Avoiding Interruption, Maintaining Interest, Postponing Evaluation, Organizing Information, and Showing Interest. The data were analyzed by IBM-SPSS software, version 20, and the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, the chi-squared test, and multiple linear regressions.

The mean score of active listening in hospital managers was 2.32 out of 3.The highest score (2.27) was obtained by the first-level managers, and the top managers got the lowest score (2.16). Hospital mangers were best in showing interest and worst in avoiding interruptions. The area of employment was a significant predictor of avoiding interruption and the managers’ gender was a strong predictor of skill in maintaining interest (p < 0.05). The type of management and education can predict postponing evaluation, and the length of employment can predict showing interest (p < 0.05).

There is a necessity for the development of strategies to create more awareness among the hospital managers concerning their active listening skills.

1. Introduction

Communication is one of the most important skills in life. This skill is not just speaking and writing; we often forget that one of the most important parts of it is listening. Listening is hard work and requires concentration ( 1 ). We do not listen efficiently because of our faulty listening habits. Listening is something more than the physical process of hearing. It is a matter of attitude and also an intellectual and emotional process ( 2 ). According to Hunsaker and Alessandra ( 1 ), when people are listening, they can be placed in one of four general categories, i.e., non-listener, marginal listener, evaluative listener, and active listener. Each category requires a particular depth of concentration and sensitivity from the listener, and trust and effective communication increase as we advance beyond the first type. Active listening (AL) is the highest and most effective level of listening, and it is a special communication skill. It is also a great strategy for having effective communication ( 3 ). It is based on complete attention to what a person is saying, listening carefully while showing interest and not interrupting ( 4 ). Active listening requires listening for the content, intent, and feeling of the speaker. The active listener shows her or his interest verbally with questions and with non-verbal, visual cues signifying that the other person has something important to say ( 5 ). Active listening generally does not occur in hurried communications between two people ( 3 ). This skill included verbal and non-verbal items and as being a good active listener different factors should be considered, such as appropriate body movement and posture showing involvement, facial expressions, eye contact, showing interest in the speaker’s words, minimum verbal encouragement, attentive silence, reflect back feelings and content, and summarizing intellectually the speaker’s words and their purpose ( 6 ). Review of different texts and references showed that we can consider three principal factors for AL, i.e., listening attitude, listening skill, and conversation opportunity. According to these factors, we can consider five subscales for active listening, i.e., avoiding interruption, maintaining interest, postponing evaluation, organizing information, and showing interest ( 7 – 10 ). The role of communication skill, especially listening, is very important for managers, because listening is a critical factor in their effectiveness, and creative managers are good listeners. So, many organizations try to improve this skill in their managers ( 11 , 12 ). Listening requires the managers to understand that their staff and customers are important. Managers listen to their staff’s ideas and have the ability to draw out their best advice. It is certain when leaders allocate time to listen actively, they build trust and commitment in their work and this is different from one-way communication and issuing orders to people ( 13 ). Supervisors with better listening attitudes and skills enhance their communication with subordinates, which could result in the subordinates’ perceiving that they have more support, which causes them to feel better about their work and their supervisor ( 14 ). Therefore, it is obvious that, if managers want to be successful, they should listen to their staff and customers and get their feedback ( 15 ). In management, AL is an important factor of the client-centered therapy developed by C. R. Rodgers ( 16 ). He brought into play AL for improving relationship between managers and workers in the organization. AL can improve interpersonal relationships and perception of confidence and respect, lessen tension, and provide a better environment for joint problem solving and sharing the information in organization ( 17 ). In a guideline in Japan, AL was introduced as an important factor for reducing uneasiness and suffering in workers, and it was used for managing workers' stress through improving communication ( 18 ). Changing interpersonal relationships positively and reducing stress by AL was reported by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) ( 19 ). In healthcare organizations, improving communication among healthcare professional has a major impact on patients’ safety since one of the important causes of medical errors and unintentional harm to patients is ineffective communication ( 20 ). The value of active listening has been generally known, but it has not been studied in depth, especially in healthcare. Although the root of active listening is in each person’s personality, some factors or techniques can facilitate it and make it teachable ( 5 ). So, healthcare organizations can train and retrain their different levels of managers, making them more efficient and compassionate leaders, which will lead to a better work environment for the staff, making the organization more successful. Although calls for action issued by Keshtkaran, Makarem, and Motaghed ( 21 – 23 ) emphasized the need for organizations to conduct research in active listening in Iran, the literature shows that the results of such research has not been used productively in active listening, especially by hospital managers ( 24 ). Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine whether managers in hospitals listen actively. Moreover, since the listening styles between the top, middle, and first-level managers may vary according to their demographic features, we conducted additional analysis on managers' gender, age, education, marital status, positions, and the length of their employment.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. study setting and selection criteria.

This cross-sectional study was conducted between May and June 2014 in four teaching hospitals affiliated with the Kerman University of Medical Sciences in southeast Iran, including Shahid Beheshti, Afzalipor, Shahid Bahonar, and Shafa Hospitals. They had 220 to 460 active beds and 350 to 1000 personnel. The subjects included all 137 managers, consisting of four top managers, 94 middle managers and medical supervisors, and 39 first-level managers. All managers returned the questionnaire and 133 of them (97%) completed all of the questions. We excluded four managers because they didn’t complete the demographic part.

2.2. Data collection and measurement tool

Active Listening skill among hospital managers was measured by self-made Active listening Skill Scale (ALSS) developed based on a literature review ( 7 – 10 ). It consisted of 18 items with a 3-point Likert response option (usually, sometime, and seldom) with the key elements of active listening. It had five subscales, i.e., Avoiding Interruption, Maintaining Interest, Postponing Evaluation, Organizing Information, and Showing Interest.

2.3. Reliability and validity of measurement tool

The validity of the content of the ALSS was explored by 10 organizational behavior and human resources management experts. The internal consistency of the ALSS sub-scales was calculated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated to estimate the sub-scales’ shared variance. The content validity of the ALSS was good and internal consistency was 0.70.

2.4. Data analysis

The data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics (Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, chi-squared test, and Multiple Linear Regression) through IBM-SPSS 20, and the significance level was set to 0.05.

2.5. Ethical consideration

Managers were asked to complete the ALSS questionnaires anonymously. This study was approved and supported by the Kerman University of Medical Sciences. Also it received the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University.

3.1. Demographic and professional characteristics of managers

Most of managers (70%) were female, 86% were married, and their mean age was 39 ± 7.6 (24–57). Of 133 managers, 93 (70%) worked in clinical units, and 40 (30%) worked in administrative units. Most of them (76%) had a license degree and at least 16 years of experience ( Table 1 ).

Demographic and professional characteristics of the managers

3.2. Descriptive analysis of active listening and its subscales

The active listening mean score in hospital managers was 2.32 out of 3 (Min = 1.94, Max = 2.72). Hospital mangers were best in showing interest skill (Mean = 2.4, SD = 0.34) of AL, although they were worst in avoiding interruption skill (Mean = 2.05, SD = 0.37). Among the AL subscales, the highest score was obtained by first-level managers (Mean = 2.27, SD = 0.36), and the top managers got the lowest score (Mean = 2.16, SD = 0. 31) ( Table 2 ).

Comparison of active listening and its subscales between three levels of managers

3.3. Analysis of active listening and demographic characteristics relationships

The area of employment was a significant predictor of avoiding interruption, as health-administrators achieved higher scores than clinical (β = 0.316, p= 0.002). Managers’ gender also influenced their maintaining interest skill, with female managers being better at it (β = −0.256, p= 0.011). Type of management (β = −0.167, p = 0.04) and education (β = −0.195, p = 0.03) were significant predictors of postponing evaluation. So, first-level managers rather than top managers and managers with lower levels of education were more skilled at postponing evaluation. Also for showing interest skill, length of employment (β = 0.42, p = 0.009) was a significant predictor, and increases in the time of employment can make managers better at this skill. The other characteristics of the respondents were the same ( Table 3 ).

Linear Regression analysis for predicting AL Subscale

4. Discussion