- About the South Centre

- Member Countries

- Board and Council

- The Executive Director

- Secretariat

- Work Program 2020-22

- Work Program 2023-25

- Semester Reports

- Quarterly Reports

- Annual Reports

- Work Opportunities

- Global Economic Crises & Conditions

- Macroeconomic & Financial Policies

- International Tax Cooperation

- Development Policies

- Sustainable Development

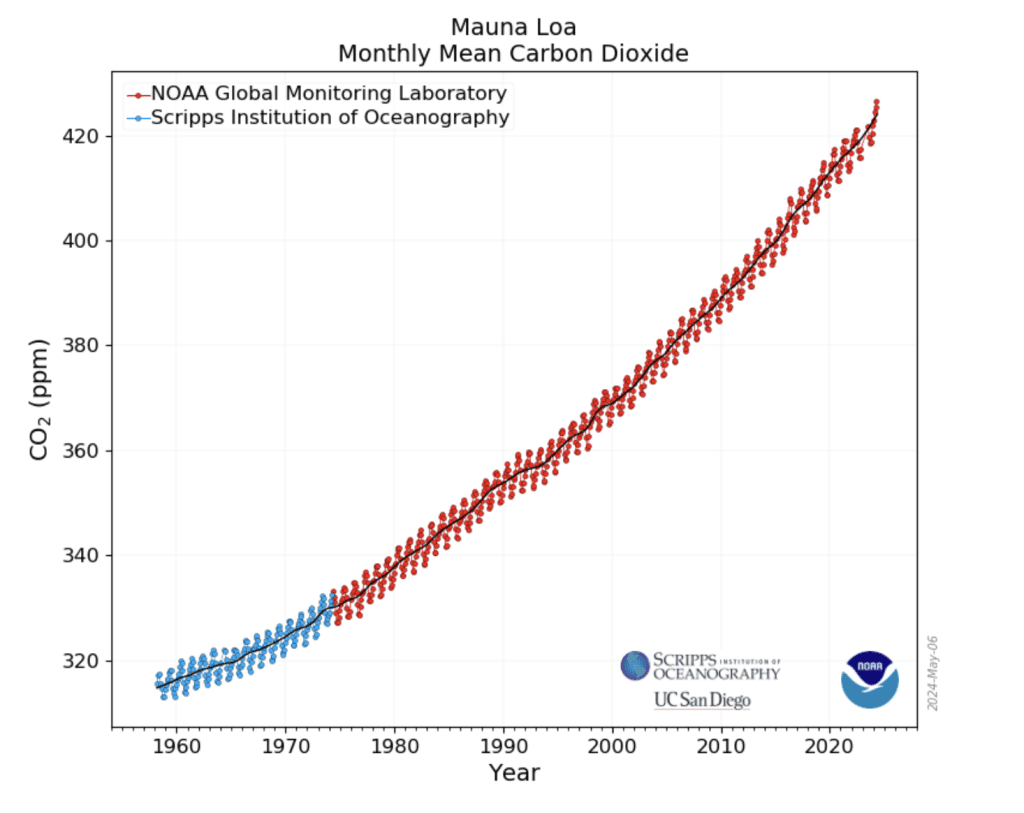

- Climate Change

- Other Environment Issues

- United Nations System

- Bretton Woods Institutions

- South-South Cooperation

- Intellectual Property

- Technology Transfer

- Access to Medicines

- Genetic Resources & TK

- Regional Trade Agreements

- Investment Agreements

- Other Trade & Investment Issues

- Food Security

- Human Rights

- Labour & Migration

- Publications Catalogues

- Research Papers

- Policy Briefs

- Previous SouthViews

- South Centre News on AMR

- Other Publications

- The South Centre Monthly

- Beijing+25 Update Series

- Analytical Notes

- South Bulletins

- Publications Archive

- Publications Guidelines

- The South Centre Events

- External Events

- Past Events Documentation Archive

- Statements and Press Releases

- News from the South Centre

- The South Centre in the Media

- News Archive

- YouTube Channel

Recent releases

- Paper: CLs - Remedy Against Excessive Pricing of Medicines

- Brief: MC13 Decision on WPEC

- Brief: UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation

- SouthViews: Interconnected Threats to Global Sustainability: Deforestation, TK & Biopiracy

Publications and Pages

- WHO Pandemic Treaty & IHR

- Repository of Copyright L&E

Main events

- Side Event During the WIPO Diplomatic Conference on Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge, 15 May 2024, Geneva

- Academic Dialogue: The Political Economy of Pharmaceutical Patent Examination—Argentina in Comparative Perspective, 8 May 2024, Geneva

E-mail List Subscription

Training and other tools offered by the south centre on ip and health, south centre tax initiative, research paper 55, november 2014.

Patent Protection for Plants: Legal Options for Developing Countries

The paper examines, first, the exclusion of patent protection for plants, including plant varieties, biological materials, and essentially biological processes for the production of plants. The legal implications of the right – recognized under the TRIPS Agreement – to exclude plants from patent protection are briefly discussed, as well as how the exclusion allowed by article 27.3(b) of said Agreement has been implemented at the national level and, particularly, whether it can be extended to parts and components of plants.

Second, the paper describes the obligation to grant patents on plants imposed under several free trade agreements (FTAs) entered into between the USA and developing countries. Third, it analyses possible limitations to the scope of patents relating to plants. Fourth, possible exceptions to the exclusive rights normally granted by a patent are examined, including the question of whether introducing specific provisions on plant materials is compatible with the non-discrimination clause of article 27.3(b) of the TRIPS Agreement. Fifth, the paper briefly considers how to address the overlapping of plant variety protection (PVP) and patent protection and the issue of infringement and permanent injunctions. Finally, some conclusions and recommendations are made.

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Generative Artificial Intelligence: Trends and Prospects

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

55 Page Essay & Research Paper Examples

What does a 55 page essay look like? Find the answer below!

55 page essays are 13700 to 13750 words long (double-spaced 12 pt). They contain 137 to 183 paragraphs. A paper of such a length is rarely an essay. You’ll more likely be assigned a 55 page research paper or term paper at the graduate level.

How long does it take to write a 55 page essay? Such a long piece should be properly planned. If you need to perform research and add references, you’ll need at least 55 hours. Trying to complete such a serious task in one day is not a good idea.

If you’re searching for 55 page paper examples, look at the collection below. Get inspired to write your own piece with the samples we’ve prepared!

55-page Essay Examples: 25 Samples

Improved work environment for employees working at a production plant.

- Subjects: Business Management

- Words: 15428

Internationalization Process in China

- Subjects: Economics Globalization

- Words: 18058

Apple and Brand-Customer Relationship

- Subjects: Business Marketing

- Words: 14240

Real Estate Text Marketing in China

- Subjects: Economics Housing

- Words: 16003

Mergers: Cisco Systems Incorporation and Bay Networks

- Subjects: Business Company Analysis

- Words: 19381

Chronic Kidney Disease: Body Mass Index and Haemoglobin

- Subjects: Gastroenterology Health & Medicine

- Words: 14651

“The War of the Worlds” a Novel by Herbert Wells

- Subjects: British Literature Literature

- Words: 15302

The Management of Police and Development of Law

- Subjects: Politics & Government Public Policies

- Words: 15158

Office Politics in a Multi-Cultural Setting

- Subjects: Business Corporate Culture

- Words: 15144

Strategies for Non-Profit Organisations

- Subjects: Business Strategic Management

- Words: 15174

Tourism Satisfaction and Loyalty: From UK to Shanghai

- Subjects: Effects of Tourism Tourism

- Words: 15090

Agricultural Policies in the EU vs. the US

- Subjects: Agriculture Sciences

- Words: 14960

Energy and Water Projects in the Middle East and North Africa

- Subjects: Economic Development Economics

- Words: 15234

Corporate Governance Practice: Nike in Vietnam

- Subjects: Business Corporate Governance

- Words: 11113

Tourists’ Attitude to Technology in China’s Heritage Tourism

- Subjects: Tourism Tourist Attractions

- Words: 15096

After-Sales Services and Innovative Approaches

- Words: 12584

Real Estate Situation in Manhattan and American Crisis

- Subjects: Big Economic Issues Economics

- Words: 14946

Innovations in Mobile Communication Devices

- Subjects: Phones Tech & Engineering

- Words: 14365

Diagnosing the Renal Artery Stenosis in Children

- Subjects: Health & Medicine Pediatrics

- Words: 15055

Marketing Communications: Expanding Apple’s Loyal Customer Base

- Subjects: Business Marketing Communication

- Words: 15159

Car Brands as Perceived in the UK and Worldwide

- Subjects: Business Industry

- Words: 14935

The Effect of Sleep Quality and IQ on Memory

- Subjects: Cognition and Perception Psychology

- Words: 12777

Oversight and the Expansion of the Five Eyes

- Subjects: Homeland Security Law

- Words: 15155

New Enterprise Start-up Plan: On-Demand Courier Service to Deliver Medicine

- Subjects: Business Entrepreneurship

- Words: 15616

Factors Leading Veterans to Homelessness

- Subjects: Society's Imperfections Sociology

- Words: 15009

Writing a Research Paper

This page lists some of the stages involved in writing a library-based research paper.

Although this list suggests that there is a simple, linear process to writing such a paper, the actual process of writing a research paper is often a messy and recursive one, so please use this outline as a flexible guide.

Discovering, Narrowing, and Focusing a Researchable Topic

- Try to find a topic that truly interests you

- Try writing your way to a topic

- Talk with your course instructor and classmates about your topic

- Pose your topic as a question to be answered or a problem to be solved

Finding, Selecting, and Reading Sources

You will need to look at the following types of sources:

- library catalog, periodical indexes, bibliographies, suggestions from your instructor

- primary vs. secondary sources

- journals, books, other documents

Grouping, Sequencing, and Documenting Information

The following systems will help keep you organized:

- a system for noting sources on bibliography cards

- a system for organizing material according to its relative importance

- a system for taking notes

Writing an Outline and a Prospectus for Yourself

Consider the following questions:

- What is the topic?

- Why is it significant?

- What background material is relevant?

- What is my thesis or purpose statement?

- What organizational plan will best support my purpose?

Writing the Introduction

In the introduction you will need to do the following things:

- present relevant background or contextual material

- define terms or concepts when necessary

- explain the focus of the paper and your specific purpose

- reveal your plan of organization

Writing the Body

- Use your outline and prospectus as flexible guides

- Build your essay around points you want to make (i.e., don’t let your sources organize your paper)

- Integrate your sources into your discussion

- Summarize, analyze, explain, and evaluate published work rather than merely reporting it

- Move up and down the “ladder of abstraction” from generalization to varying levels of detail back to generalization

Writing the Conclusion

- If the argument or point of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize the argument for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the end of your paper to add your points up, to explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction.

- Perhaps suggest what about this topic needs further research.

Revising the Final Draft

- Check overall organization : logical flow of introduction, coherence and depth of discussion in body, effectiveness of conclusion.

- Paragraph level concerns : topic sentences, sequence of ideas within paragraphs, use of details to support generalizations, summary sentences where necessary, use of transitions within and between paragraphs.

- Sentence level concerns: sentence structure, word choices, punctuation, spelling.

- Documentation: consistent use of one system, citation of all material not considered common knowledge, appropriate use of endnotes or footnotes, accuracy of list of works cited.

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

Home / Guides / Writing Guides / Paper Types / How to Write a Research Paper

How to Write a Research Paper

Research papers are a requirement for most college courses, so knowing how to write a research paper is important. These in-depth pieces of academic writing can seem pretty daunting, but there’s no need to panic. When broken down into its key components, writing your paper should be a manageable and, dare we say it, enjoyable task.

We’re going to look at the required elements of a paper in detail, and you might also find this webpage to be a useful reference .

Guide Overview

- What is a research paper?

- How to start a research paper

- Get clear instructions

- Brainstorm ideas

- Choose a topic

- Outline your outline

- Make friends with your librarian

- Find quality sources

- Understand your topic

- A detailed outline

- Keep it factual

- Finalize your thesis statement

- Think about format

- Cite, cite and cite

- The editing process

- Final checks

What is a Research Paper?

A research paper is more than just an extra long essay or encyclopedic regurgitation of facts and figures. The aim of this task is to combine in-depth study of a particular topic with critical thinking and evaluation by the student—that’s you!

There are two main types of research paper: argumentative and analytical.

Argumentative — takes a stance on a particular topic right from the start, with the aim of persuading the reader of the validity of the argument. These are best suited to topics that are debatable or controversial.

Analytical — takes no firm stance on a topic initially. Instead it asks a question and should come to an answer through the evaluation of source material. As its name suggests, the aim is to analyze the source material and offer a fresh perspective on the results.

If you wish to further your understanding, you can learn more here .

A required word count (think thousands!) can make writing that paper seem like an insurmountable task. Don’t worry! Our step-by-step guide will help you write that killer paper with confidence.

How to Start a Research Paper

Don’t rush ahead. Taking care during the planning and preparation stage will save time and hassle later.

Get Clear Instructions

Your lecturer or professor is your biggest ally—after all, they want you to do well. Make sure you get clear guidance from them on both the required format and preferred topics. In some cases, your tutor will assign a topic, or give you a set list to choose from. Often, however, you’ll be expected to select a suitable topic for yourself.

Having a research paper example to look at can also be useful for first-timers, so ask your tutor to supply you with one.

Brainstorm Ideas

Brainstorming research paper ideas is the first step to selecting a topic—and there are various methods you can use to brainstorm, including clustering (also known as mind mapping). Think about the research paper topics that interest you, and identify topics you have a strong opinion on.

Choose a Topic

Once you have a list of potential research paper topics, narrow them down by considering your academic strengths and ‘gaps in the market,’ e.g., don’t choose a common topic that’s been written about many times before. While you want your topic to be fresh and interesting, you also need to ensure there’s enough material available for you to work with. Similarly, while you shouldn’t go for easy research paper topics just for the sake of giving yourself less work, you do need to choose a topic that you feel confident you can do justice to.

Outline Your Outline

It might not be possible to form a full research paper outline until you’ve done some information gathering, but you can think about your overall aim; basically what you want to show and how you’re going to show it. Now’s also a good time to consider your thesis statement, although this might change as you delve into your source material deeper.

Researching the Research

Now it’s time to knuckle down and dig out all the information that’s relevant to your topic. Here are some tips.

Make Friends With Your Librarian

While lots of information gathering can be carried out online from anywhere, there’s still a place for old-fashioned study sessions in the library. A good librarian can help you to locate sources quickly and easily, and might even make suggestions that you hadn’t thought of. They’re great at helping you study and research, but probably can’t save you the best desk by the window.

Find Quality Sources

Not all sources are created equal, so make sure that you’re referring to reputable, reliable information. Examples of sources could include books, magazine articles, scholarly articles, reputable websites, databases and journals. Keywords relating to your topic can help you in your search.

As you search, you should begin to compile a list of references. This will make it much easier later when you are ready to build your paper’s bibliography. Keeping clear notes detailing any sources that you use will help you to avoid accidentally plagiarizing someone else’s work or ideas.

Understand Your Topic

Simply regurgitating facts and figures won’t make for an interesting paper. It’s essential that you fully understand your topic so you can come across as an authority on the subject and present your own ideas on it. You should read around your topic as widely as you can, before narrowing your area of interest for your paper, and critically analyzing your findings.

A Detailed Outline

Once you’ve got a firm grip on your subject and the source material available to you, formulate a detailed outline, including your thesis statement and how you are going to support it. The structure of your paper will depend on the subject type—ask a tutor for a research paper outline example if you’re unsure.

Get Writing!

If you’ve fully understood your topic and gathered quality source materials, bringing it all together should actually be the easy part!

Keep it Factual

There’s no place for sloppy writing in this kind of academic task, so keep your language simple and clear, and your points critical and succinct. The creative part is finding innovative angles and new insights on the topic to make your paper interesting.

Don’t forget about our verb , preposition , and adverb pages. You may find useful information to help with your writing!

Finalize Your Thesis Statement

You should now be in a position to finalize your thesis statement, showing clearly what your paper will show, answer or prove. This should usually be a one or two sentence statement; however, it’s the core idea of your paper, and every insight that you include should be relevant to it. Remember, a thesis statement is not merely a summary of your findings. It should present an argument or perspective that the rest of your paper aims to support.

Think About Format

The required style of your research paper format will usually depend on your subject area. For example, APA format is normally used for social science subjects, while MLA style is most commonly used for liberal arts and humanities. Still, there are thousands of more styles . Your tutor should be able to give you clear guidance on how to format your paper, how to structure it, and what elements it should include. Make sure that you follow their instruction. If possible, ask to see a sample research paper in the required format.

Cite, Cite and Cite

As all research paper topics invariably involve referring to other people’s work, it’s vital that you know how to properly cite your sources to avoid unintentional plagiarism. Whether you’re paraphrasing (putting someone else’s ideas into your own words) or directly quoting, the original source needs to be referenced. What style of citation formatting you use will depend on the requirements of your instructor, with common styles including APA and MLA format , which consist of in-text citations (short citations within the text, enclosed with parentheses) and a reference/works cited list.

The Editing Process

It’s likely that your paper will go through several drafts before you arrive at the very best version. The editing process is your chance to fix any weak points in your paper before submission. You might find that it needs a better balance of both primary and secondary sources (click through to find more info on the difference), that an adjective could use tweaking, or that you’ve included sources that aren’t relevant or credible. You might even feel that you need to be clearer in your argument, more thorough in your critical analysis, or more balanced in your evaluation.

From a stylistic point of view, you want to ensure that your writing is clear, simple and concise, with no long, rambling sentences or paragraphs. Keeping within the required word count parameters is also important, and another thing to keep in mind is the inclusion of gender-neutral language, to avoid the reinforcement of tired stereotypes.

Don’t forget about our other pages! If you are looking for help with other grammar-related topics, check out our noun , pronoun , and conjunction pages.

Final Checks

Once you’re happy with the depth and balance of the arguments and points presented, you can turn your attention to the finer details, such as formatting, spelling, punctuation, grammar and ensuring that your citations are all present and correct. The EasyBib Plus plagiarism checker is a handy tool for making sure that your sources are all cited. An EasyBib Plus subscription also comes with access to citation tools that can help you create citations in your choice of format.

Also, double-check your deadline date and the submissions guidelines to avoid any last-minute issues. Take a peek at our other grammar pages while you’re at it. We’ve included numerous links on this page, but we also have an interjection page and determiner page.

So you’ve done your final checks and handed in your paper according to the submissions guidelines and preferably before deadline day. Congratulations! If your schedule permits, now would be a great time to take a break from your studies. Maybe plan a fun activity with friends or just take the opportunity to rest and relax. A well-earned break from the books will ensure that you return to class refreshed and ready for your next stage of learning—and the next research paper requirement your tutor sets!

EasyBib Writing Resources

Writing a paper.

- Academic Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- College Admissions Essay

- Expository Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Research Paper

- Thesis Statement

- Writing a Conclusion

- Writing an Introduction

- Writing an Outline

- Writing a Summary

EasyBib Plus Features

- Citation Generator

- Essay Checker

- Expert Check Proofreader

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tools

Plagiarism Checker

- Spell Checker

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Grammar and Plagiarism Checkers

Grammar Basics

Plagiarism Basics

Writing Basics

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Trending Articles

- Effects of Semaglutide on Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Perkovic V, et al. N Engl J Med. 2024. PMID: 38785209

- Access to and quality of elective care: a prospective cohort study using hernia surgery as a tracer condition in 83 countries. NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Global Surgery. Lancet Glob Health. 2024. PMID: 38797188

- A modern way to teach and practice manual therapy. Kerry R, et al. Chiropr Man Therap. 2024. PMID: 38773515 Free PMC article. Review.

- Oncogenic fatty acid oxidation senses circadian disruption in sleep-deficiency-enhanced tumorigenesis. Peng F, et al. Cell Metab. 2024. PMID: 38772364

- Distinct roles of TREM2 in central nervous system cancers and peripheral cancers. Zhong J, et al. Cancer Cell. 2024. PMID: 38788719

Latest Literature

- Am J Clin Nutr (2)

- Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2)

- Gastroenterology (2)

- J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1)

- J Exp Med (1)

- Methods Mol Biol (1)

- Pediatrics (4)

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review

Jiaqi xiong.

a Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON

Orly Lipsitz

c Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario

Flora Nasri

Leanna m.w. lui, hartej gill, david chen-li, michelle iacobucci.

e Department of Psychological Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

f Institute for Health Innovation and Technology (iHealthtech), National University of Singapore, Singapore

Amna Majeed

Roger s. mcintyre.

b Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

d Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, ON

Associated Data

As a major virus outbreak in the 21st century, the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to unprecedented hazards to mental health globally. While psychological support is being provided to patients and healthcare workers, the general public's mental health requires significant attention as well. This systematic review aims to synthesize extant literature that reports on the effects of COVID-19 on psychological outcomes of the general population and its associated risk factors.

A systematic search was conducted on PubMed, Embase, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus from inception to 17 May 2020 following the PRISMA guidelines. A manual search on Google Scholar was performed to identify additional relevant studies. Articles were selected based on the predetermined eligibility criteria.

Results: Relatively high rates of symptoms of anxiety (6.33% to 50.9%), depression (14.6% to 48.3%), post-traumatic stress disorder (7% to 53.8%), psychological distress (34.43% to 38%), and stress (8.1% to 81.9%) are reported in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in China, Spain, Italy, Iran, the US, Turkey, Nepal, and Denmark. Risk factors associated with distress measures include female gender, younger age group (≤40 years), presence of chronic/psychiatric illnesses, unemployment, student status, and frequent exposure to social media/news concerning COVID-19.

Limitations

A significant degree of heterogeneity was noted across studies.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic is associated with highly significant levels of psychological distress that, in many cases, would meet the threshold for clinical relevance. Mitigating the hazardous effects of COVID-19 on mental health is an international public health priority.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a cluster of atypical cases of pneumonia was reported in Wuhan, China, which was later designated as Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 Feb 2020 ( Anand et al., 2020 ). The causative virus, SARS-CoV-2, was identified as a novel strain of coronaviruses that shares 79% genetic similarity with SARS-CoV from the 2003 SARS outbreak ( Anand et al., 2020 ). On 11 Mar 2020, the WHO declared the outbreak a global pandemic ( Anand et al., 2020 ).

The rapidly evolving situation has drastically altered people's lives, as well as multiple aspects of the global, public, and private economy. Declines in tourism, aviation, agriculture, and the finance industry owing to the COVID-19 outbreak are reported as massive reductions in both supply and demand aspects of the economy were mandated by governments internationally ( Nicola et al., 2020 ). The uncertainties and fears associated with the virus outbreak, along with mass lockdowns and economic recession are predicted to lead to increases in suicide as well as mental disorders associated with suicide. For example, McIntyre and Lee (2020b) have reported a projected increase in suicide from 418 to 2114 in Canadian suicide cases associated with joblessness. The foregoing result (i.e., rising trajectory of suicide) was also reported in the USA, Pakistan, India, France, Germany, and Italy ( Mamun and Ullah, 2020 ; Thakur and Jain, 2020 ). Separate lines of research have also reported an increase in psychological distress in the general population, persons with pre-existing mental disorders, as well as in healthcare workers ( Hao et al., 2020 ; Tan et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020b ). Taken together, there is an urgent call for more attention given to public mental health and policies to assist people through this challenging time.

The objective of this systematic review is to summarize extant literature that reported on the prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other forms of psychological distress in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. An additional objective was to identify factors that are associated with psychological distress.

Methods and results were formated based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines ( Moher et al., 2010 ).

2.1. Search strategy

A systematic search following the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram ( Fig. 1 ) was conducted on PubMed, Medline, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science from inception to 17 May 2020. A manual search on Google Scholar was performed to identify additional relevant studies. The search terms that were used were: (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 OR 2019nCoV OR HCoV-19) AND (Mental health OR Psychological health OR Depression OR Anxiety OR PTSD OR PTSS OR Post-traumatic stress disorder OR Post-traumatic stress symptoms) AND (General population OR general public OR Public OR community). An example of search procedure was included as a supplementary file.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study selection flow diagram. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.2. Study selection and eligibility criteria

Titles and abstracts of each publication were screened for relevance. Full-text articles were accessed for eligibility after the initial screening. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: 1) followed cross-sectional study design; 2) assessed the mental health status of the general population/public during the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated risk factors; 3) utilized standardized and validated scales for measurement. Studies were excluded if they: 1) were not written in English or Chinese; 2) focused on particular subgroups of the population (e.g., healthcare workers, college students, or pregnant women); 3) were not peer-reviewed; 4) did not have full-text availability.

2.3. Data extraction

A data extraction form was used to include relevant data: (1) Lead author and year of publication, (2) Country/region of the population studied, (3) Study design, (4) Sample size, (5) Sample characteristics, (6) Assessment tools, (7) Prevalence of symptoms of depression/anxiety/ PTSD/psychological distress/stress, (8) Associated risk factors.

2.4 Quality appraisal

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) adapted for cross-sectional studies was used for study quality appraisal, which was modified accordingly from the scale used in Epstein et al. (2018) . The scale consists of three dimensions: Selection, Comparability, and Outcome. There are seven categories in total, which assess the representativeness of the sample, sample size justification, comparability between respondents and non-respondents, ascertainments of exposure, comparability based on study design or analysis, assessment of the outcome, and appropriateness of statistical analysis. A list of specific questions was attached as a supplementary file. A total of nine stars can be awarded if the study meets certain criteria, with a maximum of four stars assigned for the selection dimension, a maximum of two stars assigned for the comparability dimension, and a maximum of three stars assigned for the outcome dimension.

3.1. Search results

In total, 648 publications were identified. Of those, 264 were removed after initial screening due to duplication. 343 articles were excluded based on the screening of titles and abstracts. 41 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. There were 12 articles excluded for studying specific subgroups of the population, five articles excluded for not having a standardized/ appropriate measure, three articles excluded for being review papers, and two articles excluded for being duplicates. Following the full-text screening, 19 studies met the inclusion criteria.

3.2. Study characteristics

Study characteristics and primary study findings are summarized in Table 1 . The sample size of the 19 studies ranged from 263 to 52,730 participants, with a total of 93,569 participants. A majority of study participants were over 18 years old. Female participants ( n = 60,006) made up 64.1% of the total sample. All studies followed a cross-sectional study design. The 19 studies were conducted in eight different countries, including China ( n = 10), Spain ( n = 2), Italy ( n = 2), Iran ( n = 1), the US ( n = 1), Turkey ( n = 1), Nepal ( n = 1), and Denmark ( n = 1). The primary outcomes chosen in the included studies varied across studies. Twelve studies included measures of depressive symptoms while eleven studies included measures of anxiety. Symptoms of PTSD/psychological impact of events were evaluated in four studies while three studies assessed psychological distress. It was additionally observed that four studies contained general measures of stress. Three studies did not explicitly report the overall prevalence rates of symptoms; notwithstanding the associated risk factors were identified and discussed.

Summary of study sample characteristics, study design, assessment tools used, prevalence rates and associated risk factors.

3.3. Quality appraisal

The result of the study quality appraisal is presented in Table 2 . The overall quality of the included studies is moderate, with total stars awarded varying from four to eight. There were two studies with four stars, two studies with five stars, seven studies with six stars, seven studies with seven stars, and one study with eight stars.

Results of study quality appraisal of the included studies.

3.4. Measurement tools

A variety of scales were used in the studies ( n = 19) for assessing different adverse psychological outcomes. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Patient Health Questionnaire-9/2 (PHQ-9/2), Self-rating Depression Scales (SDS), The World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) were used for measuring depressive symptoms. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7/2-item (GAD-7/2), and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) were used to evaluate symptoms of anxiety. The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale- 21 items (DASS-21) was used for the evaluation of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used for assessing anxiety and depressive symptoms. Psychological distress was measured by The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (CPDI) and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6/10). Symptoms of PTSD were assessed by The Impact of Event Scale-(Revised) (IES(-R)), PTSD Checklist (PCL-(C)-2/5). Chinese Perceived Stress Scale (CPSS-10) was used in one study to evaluate symptoms of stress.

3.5. Symptoms of depression and associated risk factors

Symptoms of depression were assessed in 12 out of the 19 studies ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and S.B. Özdin, 2020 ; Sønderskov et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ; Wang et al., 2020b ). The prevalence of depressive symptoms ranged from 14.6% to 48.3%. Although the reported rates are higher than previously estimated one-year prevalence (3.6% and 7.2%) of depression among the population prior to the pandemic ( Huang et al., 2019 ; Lim et al., 2018 ), it is important to note that presence of depressive symptoms does not reflect a clinical diagnosis of depression.

Many risk factors were identified to be associated with symptoms of depression amongst the COVID-19 pandemic. Females were reported as are generally more likely to develop depressive symptoms when compared to their male counterparts ( Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Sønderskov et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ). Participants from the younger age group (≤40 years) presented with more depressive symptoms ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ;). Student status was also found to be a significant risk factor for developing more depressive symptoms as compared to other occupational statuses (i.e. employment or retirement) ( González et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ). Four studies also identified lower education levels as an associated factor with greater depressive symptoms ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ). A single study by Wang et al., 2020b reported that people with higher education and professional jobs exhibited more depressive symptoms in comparison to less educated individuals and those in service or enterprise industries.

Other predictive factors for symptoms of depression included living in urban areas, poor self-rated health, high loneliness, being divorced/widowed, being single, lower household income, quarantine status, worry about being infected, property damage, unemployment, not having a child, a past history of mental stress or medical problems, having an acquaintance infected with COVID-19, perceived risks of unemployment, exposure to COVID-19 related news, higher perceived vulnerability, lower self-efficacy to protect themselves, the presence of chronic diseases, and the presence of specific physical symptoms ( Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and Özdin, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ).

3.6. Symptoms of anxiety and associated risk factors

Anxiety symptoms were assessed in 11 out of the 19 studies, with a noticeable variation in the prevalence of anxiety symptoms ranging from 6.33% to 50.9% ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and Özdin, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ; Wang et al., 2020b ).

Anxiety is often comorbid with depression ( Choi et al., 2020 ). Some predictive factors for depressive symptoms also apply to symptoms of anxiety, including a younger age group (≤40 years), lower education levels, poor self-rated health, high loneliness, female gender, divorced/widowed status, quarantine status, worry about being infected, property damage, history of mental health issue/medical problems, presence of chronic illness, living in urban areas, and the presence of specific physical symptoms ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ; Wang et al., 2020b ).

Additionally, social media exposure or frequent exposure to news/information concerning COVID-19 was positively associated with symptoms of anxiety ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ). With respect to marital status, one study reported that married participants had higher levels of anxiety when compared to unmarried participants ( Gao et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, Lei et al. (2020) found that divorced/widowed participants developed more anxiety symptoms than single or married individuals. A prolonged period of quarantine was also correlated with higher risks of anxiety symptoms. Intuitively, contact history with COVID-positive patients or objects may lead to more anxiety symptoms, which is noted in one study ( Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ).

3.7. Symptoms of PTSD/ psychological distress/stress and associated risk factors

With respect to PTSD symptoms, similar prevalence rates were reported by Zhang and Ma (2020) and N. Liu et al. (2020) at 7.6% and 7%, respectively. Despite using the same measurement scale as Zhang and Ma (2020) (i.e., IES), Wang et al. (2020a) noted a remarkably different result, with 53.8% of the participants reporting moderate-to-severe psychological impact. González et al. ( González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ) noted 15.8% of participants with PTSD symptoms. Three out of the four studies that measured the traumatic effects of COVID-19 reported that the female gender was more susceptible to develop symptoms of PTSD. In contrast, the research conducted by Zhang and Ma (2020) found no significant difference in IES scores between females and males. Other risk factors included loneliness, individuals currently residing in Wuhan or those who have been to Wuhan in the past several weeks (the hardest-hit city in China), individuals with higher susceptibility to the virus, poor sleep quality, student status, poor self-rated health, and the presence of specific physical symptoms. Besides sex, Zhang and Ma (2020) found that age, BMI, and education levels are also not correlated with IES-scores.

Non-specific psychological distress was also assessed in three studies. One study reported a prevalence rate of symptoms of psychological distress at 38% ( Moccia et al., 2020 ), while another study from Qiu et al. (2020) reported a prevalence of 34.43%. The study from Wang et al. (2020) did not explicitly state the prevalence rates, but the associated risk factors for higher psychological distress symptoms were reported (i.e., younger age groups and female gender are more likely to develop psychological distress) ( Qiu et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). Other predictive factors included being migrant workers, profound regional severity of the outbreak, unmarried status, the history of visiting Wuhan in the past month, higher self-perceived impacts of the epidemic ( Qiu et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). Interestingly, researchers have identified personality traits to be predictive of psychological distresses. For example, persons with negative coping styles, cyclothymic, depressive, and anxious temperaments exhibit greater susceptibility to psychological outcomes ( Wang et al., 2020 ; Moccia et al., 2020 ).

The intensity of overall stress was evaluated and reported in four studies. The prevalence of overall stress was variably reported between 8.1% to over 81.9% ( Wang et al., 2020a ; Samadarshi et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ). Females and the younger age group are often associated with higher stress levels as compared to males and the elderly. Other predictive factors of higher stress levels include student status, a higher number of lockdown days, unemployment, having to go out to work, having an acquaintance infected with the virus, presence of chronic illnesses, poor self-rated health, and presence of specific physical symptoms ( Wang et al., 2020a ; Samadarshi et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ).

3.8. A separate analysis of negative psychological outcomes

Out of the nineteen included studies, five studies appeared to be more representative of the general population based on the results of study quality appraisal ( Table 1 ). A separate analysis was conducted for a more generalizable conclusion. According to the results of these studies, the rates of negative psychological outcomes were moderate but higher than usual, with anxiety symptoms ranging from 6.33% to 18.7%, depressive symptoms ranging from 14.6% to 32.8%, stress symptoms being 27.2%, and symptoms of PTSD being approximately 7% ( Lei et al., 2020 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020b ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). In these studies, female gender, younger age group (≤40 years), and student population were repetitively reported to exhibit more adverse psychiatric symptoms.

3.9. Protective factors against symptoms of mental disorders

In addition to associated risk factors, a few studies also identified factors that protect individuals against symptoms of psychological illnesses during the pandemic. Timely dissemination of updated and accurate COVID-19 related health information from authorities was found to be associated with lower levels of anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms in the general public ( Wang et al., 2020a ). Additionally, actively carrying out precautionary measures that lower the risk of infection, such as frequent handwashing, mask-wearing, and less contact with people also predicted lower psychological distress levels during the pandemic ( Wang et al., 2020a ). Some personality traits were shown to correlate with positive psychological outcomes. Individuals with positive coping styles, secure and avoidant attachment styles usually presented fewer symptoms of anxiety and stress ( Wang et al., 2020 ; Moccia et al., 2020 ). ( Zhang et al. 2020 ) also found that participants with more social support and time to rest during the pandemic exhibited lower stress levels.

4. Discussion

Our review explored the mental health status of the general population and its predictive factors amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Generally, there is a higher prevalence of symptoms of adverse psychiatric outcomes among the public when compared to the prevalence before the pandemic ( Huang et al., 2019 ; Lim et al., 2018 ). Variations in prevalence rates across studies were noticed, which could have resulted from various measurement scales, differential reporting patterns, and possibly international/cultural differences. For example, some studies reported any participants with scores above the cut-off point (mild-to-severe symptoms), while others only included participants with moderate-to-severe symptoms ( Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ). Regional differences existed with respect to the general public's psychological health during a massive disease outbreak due to varying degrees of outbreak severity, national economy, government preparedness, availability of medical supplies/ facilities, and proper dissemination of COVID-related information. Additionally, the stage of the outbreak in each region also affected the psychological responses of the public. Symptoms of adverse psychological outcomes were more commonly seen at the beginning of the outbreak when individuals were challenged by mandatory quarantine, unexpected unemployment, and uncertainty associated with the outbreak ( Ho et al., 2020 ). When evaluating the psychological impacts incurred by the coronavirus outbreak, the duration of psychiatric symptoms should also be taken into consideration since acute psychological responses to stressful or traumatic events are sometimes protective and of evolutionary importance ( Yaribeygi et al., 2017 ; Brosschot et al., 2016 ; Gilbert, 2006 ). Being anxious and stressed about the outbreak mobilizes people and forces them to implement preventative measures to protect themselves. Follow-up studies after the pandemic may be needed to assess the long-term psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.1. Populations with greater susceptibility

Several predictive factors were identified from the studies. For example, females tended to be more vulnerable to develop the symptoms of various forms of mental disorders during the pandemic, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and stress, as reported in our included studies ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ). Greater psychological distress arose in women partially because they represent a higher percentage of the workforce that may be negatively affected by COVID-19, such as retail, service industry, and healthcare. In addition to the disproportionate effects that disruption in the employment sector has had on women, several lines of research also indicate that women exhibit differential neurobiological responses when exposed to stressors, perhaps providing the basis for the overall higher rate of select mental disorders in women ( Goel et al., 2014 ; Eid et al., 2019 ).

Individuals under 40 years old also exhibited more adverse psychological symptoms during the pandemic ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ). This finding may in part be due to their caregiving role in families (i.e., especially women), who provide financial and emotional support to children or the elderly. Job loss and unpredictability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic among this age group could be particularly stressful. Also, a large proportion of individuals under 40 years old consists of students who may also experience more emotional distress due to school closures, cancelation of social events, lower study efficiency with remote online courses, and postponements of exams ( Cao et al., 2020 ). This is consistent with our findings that student status was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms and PTSD symptoms during the COVID-19 outbreak ( Lei et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 , Wang et al., 2020a ; Samadarshi et al., 2020 ).

People with chronic diseases and a history of medical/ psychiatric illnesses showed more symptoms of anxiety and stress ( Mazza et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and Özdin, 2020 ). The anxiety and distress of chronic disease sufferers towards the coronavirus infection partly stem from their compromised immunity caused by pre-existing conditions, which renders them susceptible to the infection and a higher risk of mortality, such as those with systemic lupus erythematosus ( Sawalha et al., 2020 ). Several reports also suggested that a substantially higher death rate was noted in patients with diabetes, hypertension and other coronary heart diseases, yet the exact causes remain unknown ( Guo et al., 2020 ; Emami et al., 2020 ), leaving those with these common chronic conditions in fear and uncertainty. Additionally, another practical aspect of concern for patients with pre-existing conditions would be postponement and inaccessibility to medical services and treatment as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, as a rapidly growing number of COVID-19 patients were utilizing hospital and medical resources, primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of other diseases may have unintentionally been affected. Individuals with a history of mental disorders or current diagnoses of psychiatric illnesses are also generally more sensitive to external stressors, such as social isolation associated with the pandemic ( Ho et al., 2020 ).

4.2. COVID-19 related psychological stressors

Several studies identified frequent exposure to social media/news relating to COVID-19 as a cause of anxiety and stress symptoms ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ). Frequent social media use exposes oneself to potential fake news/reports/disinformation and the possibility for amplified anxiety. With the unpredictable situation and a lot of unknowns about the novel coronavirus, misinformation and fake news are being easily spread via social media platforms ( Erku et al., 2020 ), creating unnecessary fears and anxiety. Sadness and anxious feelings could also arise when constantly seeing members of the community suffering from the pandemic via social media platforms or news reports ( Li et al., 2020 ).

Reports also suggested that poor economic status, lower education level, and unemployment are significant risk factors for developing symptoms of mental disorders, especially depressive symptoms during the pandemic period ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ;). The coronavirus outbreak has led to strictly imposed stay-home-order and a decrease in demands for services and goods ( Nicola et al., 2020 ), which has adversely influenced local businesses and industries worldwide. Surges in unemployment rates were noted in many countries ( Statistics Canada, 2020 ; Statista, 2020 ). A decrease in quality of life and uncertainty as a result of financial hardship can put individuals into greater risks for developing adverse psychological symptoms ( Ng et al., 2013 ).

4.3. Efforts to reduce symptoms of mental disorders

4.3.1. policymaking.

The associated risk and protective factors shed light on policy enactment in an attempt to relieve the psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general public. Firstly, more attention and assistance should be prioritized to the aforementioned vulnerable groups of the population, such as the female gender, people from age group ≤40, college students, and those suffering from chronic/psychiatric illnesses. Secondly, governments must ensure the proper and timely dissemination of COVID-19 related information. For example, validation of news/reports concerning the pandemic is essential to prevent panic from rumours and false information. Information about preventative measures should also be continuously updated by health authorities to reassure those who are afraid of being infected ( Tran, et al., 2020a ). Thirdly, easily accessible mental health services are critical during the period of prolonged quarantine, especially for those who are in urgent need of psychological support and individuals who reside in rural areas ( Tran et al., 2020b ). Since in-person health services are limited and delayed as a result of COVID-19 pandemic, remote mental health services can be delivered in the form of online consultation and hotlines ( Liu et al., 2020 ; Pisciotta et al., 2019 ). Last but not least, monetary support (e.g. beneficial funds, wage subsidy) and new employment opportunities could be provided to people who are experiencing financial hardship or loss of jobs owing to the pandemic. Government intervention in the form of financial provisions, housing support, access to psychiatric first aid, and encouragement at the individual level of healthy lifestyle behavior has been shown effective in alleviating suicide cases associated with economic recession ( McIntyre and Lee, 2020a ). For instance, declines in suicide incidence were observed to be associated with government expenses in Japan during the 2008 economic depression ( McIntyre and Lee, 2020a ).

4.3.2. Individual efforts

Individuals can also take initiatives to relieve their symptoms of psychological distress. For instance, exercising regularly and maintaining a healthy diet pattern have been demonstrated to effectively ease and prevent symptoms of depression or stress ( Carek et al., 2011 ; Molendijk et al., 2018 ; Lassale et al., 2019 ). With respect to pandemic-induced symptoms of anxiety, it is also recommended to distract oneself from checking COVID-19 related news to avoid potential false reports and contagious negativity. It is also essential to obtain COVID-19 related information from authorized news agencies and organizations and to seek medical advice only from properly trained healthcare professionals. Keeping in touch with friends and family by phone calls or video calls during quarantine can ease the distress from social isolation ( Hwang et al., 2020 ).

4.4. Strengths

Our paper is the first systematic review that examines and summarizes existing literature with relevance to the psychological health of the general population during the COVID-19 outbreak and highlights important associated risk factors to provide suggestions for addressing the mental health crisis amid the global pandemic.

4.5. Limitations

Certain limitations apply to this review. Firstly, the description of the study findings was qualitative and narrative. A more objective systematic review could not be conducted to examine the prevalence of each psychological outcome due to a high heterogeneity across studies in the assessment tools used and primary outcomes measured. Secondly, all included studies followed a cross-sectional study design and, as such, causal inferences could not be made. Additionally, all studies were conducted via online questionnaires independently by the study participants, which raises two concerns: 1] Individual responses in self-assessment vary in objectivity when supervision from a professional psychiatrist/ interviewer is absent, 2] People with poor internet accessibility were likely not included in the study, creating a selection bias in the population studied. Another concern is the over-representation of females in most studies. Selection bias and over-representation of particular groups indicate that most studies may not be representative of the true population. Importantly, studies in inclusion were conducted in a limited number of countries. Thus generalizations of mental health among the general population at a global level should be made cautiously.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review examined the psychological status of the general public during the COVID-19 pandemic and stressed the associated risk factors. A high prevalence of adverse psychiatric symptoms was reported in most studies. The COVID-19 pandemic represents an unprecedented threat to mental health in high, middle, and low-income countries. In addition to flattening the curve of viral transmission, priority needs to be given to the prevention of mental disorders (e.g. major depressive disorder, PTSD, as well as suicide). A combination of government policy that integrates viral risk mitigation with provisions to alleviate hazards to mental health is urgently needed.

Authorship contribution statement

JX contributed to the overall design, article selection , review, and manuscript preparation. LL and JX contributed to study quality appraisal. All other authors contributed to review, editing, and submission.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgements.

RSM has received research grant support from the Stanley Medical Research Institute and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases/National Natural Science Foundation of China and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Shire, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, and Minerva.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 .

Appendix. Supplementary materials

- Ahmed M.Z., Ahmed O., Zhou A., Sang H., Liu S., Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020; 51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anand K.B., Karade S., Sen S., Gupta R.M. SARS-CoV-2: camazotz's curse. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2020; 76 :136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.04.008. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brosschot J.F., Verkuil B., Thayer J.F. The default response to uncertainty and the importance of perceived safety in anxiety and stress: an evolution-theoretical perspective. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016; 41 :22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.04.012. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cao W., Fang Z., Hou G., Han M., Xu X., Dong J., Zheng J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 287 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carek P.J., Laibstain S.E., Carek S.M. Exercise for the treatment of depression and anxiety. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011; 41 (1):15–28. doi: 10.2190/PM.41.1.c. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi K.W., Kim Y., Jeon H.J. Comorbid Anxiety and Depression: clinical and Conceptual Consideration and Transdiagnostic Treatment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020; 1191 :219–235. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_14. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eid R.S., Gobinath A.R., Galea L.A.M. Sex differences in depression: insights from clinical and preclinical studies. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019; 176 :86–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.01.006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Emami A., Javanmardi F., Pirbonyeh N., Akbari A. Prevalence of Underlying Diseases in Hospitalized Patients. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020; 8 (1):e35. doi: 10.22037/aaem.v8i1.600.g748. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Epstein S., Roberts E., Sedgwick R., Finning K., Ford T., Dutta R., Downs J. Poor school attendance and exclusion: a systematic review protocol on educational risk factors for self-harm and suicidal behaviours. BMJ Open. 2018; 8 (12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023953. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Erku D.A., Belachew S.W., Abrha S., Sinnollareddy M., Thoma J., Steadman K.J., Tesfaye W.H. When fear and misinformation go viral: pharmacists' role in deterring medication misinformation during the 'infodemic' surrounding COVID-19. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.032. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gao J., Zheng P., Jia Y., Chen H., Mao Y., Chen S., Wang Y., Fu H., Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15 (4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilbert P. Evolution and depression: issues and implications. Psycho. Med. 2006; 36 (3):287–297. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006112. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goel N., Workman J.L., Lee T.F., Innala L., Viau V. Sex differences in the HPA axis. Compr. Physiol. 2014; 4 (3):1121‐1155. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130054. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- González-Sanguino C., Ausín B., Castellanos M.A., Saiz J., López-Gómez A., Ugidos C., Muñoz M. Mental Health Consequences during the Initial Stage of the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guo W., Li M., Dong Y., Zhou H., Zhang Z., Tian C., Qin R., Wang H., Shen Y., Du K., Zhao L., Fan H., Luo S., Hu D. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hao F., Tan W., Jiang L., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., Hu Y., Luo X., Jiang X., McIntyre R.S., Tran B., Sun J., Zhang Z., Ho R., Ho C., Tam W. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]