Stress Management Techniques

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Stress arises when individuals perceive a discrepancy between a situation’s physical or psychological demands and the resources of their biological, psychological, or social systems (Sarafino, 2012).

There are many ways of coping with stress. Their effectiveness depends on the type of stressor, the particular individual, and the circumstances.

For example, if you think about the way your friends deal with stressors like exams, you will see a range of different coping responses. Some people will pace around or tell you how worried they are, and others will revise or pester their teachers for clues.

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) suggested there are two types of coping responses emotion focused and problem focused :

Emotion-focused Coping

Emotion-focused coping is stress management that attempts to reduce negative emotional responses associated with stress.

Negative emotions such as embarrassment, fear, anxiety, depression, excitement, and frustration are reduced or removed by the individual through various methods of coping.

Emotion-focused techniques might be the only realistic option when the source of stress is outside the person’s control.

Drug therapy can be seen as emotion-focused coping as it focuses on the arousal caused by stress, not the problem. Other emotion-focused coping techniques include:

- Distraction, e.g., keeping yourself busy to take your mind off the issue.

- Emotional disclosure. This involves expressing strong emotions by talking or writing about negative events which precipitated those emotions (Pennebaker, 1995)

- This is an important part of psychotherapy .

- Praying for guidance and strength.

- Meditation, e.g., mindfulness.

- Eating more, e.g., comfort food.

- Drinking alcohol.

- Using drugs.

- Journaling, e.g., writing a gratitude diary (Cheng, Tsui, & Lam, 2015).

- Cognitive reappraisal. This is a form of cognitive change that involves construing a potentially emotion-eliciting situation in a way that changes its emotional impact (Lazarus & Alfert, 1964).

- Suppressing (stopping/inhibiting) negative thoughts or emotions. Suppressing emotions over an extended period of time compromises immune competence and lead to poor physical health (Petrie, K. J., Booth, R. J., & Pennebaker, 1988).

Critical Evaluation

A meta-analysis revealed that emotion-focused strategies are often less effective than using problem-focused methods in relation to health outcomes(Penley, Tomaka, & Weibe, 2012).

In general, people who used emotion-focused strategies such as eating, drinking, and taking drugs reported poorer health outcomes.

Such strategies are ineffective as they ignore the root cause of the stress. The type of stressor and whether the impact was on physical or psychological health explained the strategies between coping strategies and health outcomes.

In addition, Epping-Jordan et al. (1994) found that patients with cancer who used avoidance strategies, e.g., denying they were very ill, deteriorated more quickly than those who faced up to their problems. The same pattern exists in relation to dental health and financial problems.

Emotion-focused coping does not provide a long-term solution and may have negative side effects as it delays the person dealing with the problem. However, they can be a good choice if the source of stress is outside the person’s control (e.g., a dental procedure).

Gender differences have also been reported: women tend to use more emotion-focused strategies than men (Billings & Moos, 1981).

Problem-focused Coping

Problem-focused coping targets the causes of stress in practical ways, which tackles the problem or stressful situation that is causing stress, consequently directly reducing the stress.

Problem-focused strategies aim to remove or reduce the cause of the stressor, including:

- Problem-solving.

- Time-management.

- Obtaining instrumental social support.

In general problem-focused coping is best, as it removes the stressor and deals with the root cause of the problem, providing a long-term solution.

Problem-focused strategies are successful in dealing with stressors such as discrimination (Pascoe & Richman, 2009), HIV infections (Moskowitz, Hult, Bussolari, & Acree, 2009), and diabetes (Duangdao & Roesch, 2008).

However, it is not always possible to use problem-focused strategies. For example, when someone dies, problem-focused strategies may not be very helpful for the bereaved. Dealing with the feeling of loss requires emotion-focused coping.

The problem-focused approach will not work in any situation where it is beyond the individual’s control to remove the source of stress. They work best when the person can control the source of stress (e.g., exams, work-based stressors, etc.).

It is not a productive method for all individuals. For example, not all people are able to take control of a situation or perceive a situation as controllable.

For example, optimistic people who tend to have positive expectations of the future are more likely to use problem-focused strategies. In contrast, pessimistic individuals are more inclined to use emotion-focused strategies (Nes & Segerstrom, 2006).

Billings, A. G., & Moos, R. H. (1981). The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. Journal of behavioral Medicine , 4, 139-157.

Cheng, S. T., Tsui, P. K., & Lam, J. H. (2015). Improving mental health in health care practitioners: Randomized controlled trial of a gratitude intervention. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 83(1) , 177.

Duangdao, K. M., & Roesch, S. C. (2008). Coping with diabetes in adulthood: a meta-analysis. Journal of behavioral Medicine, 31(4) , 291-300.

Epping-Jordan, J. A., Compas, B. E., & Howell, D. C. (1994). Predictors of cancer progression in young adult men and women: Avoidance, intrusive thoughts, and psychological symptoms. Health Psychology , 13: 539-547.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American psychologist , 46(8), 819.

Lazarus, R. S., & Alfert, E. (1964). Short-circuiting of threat by experimentally altering cognitive appraisal. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 69(2) , 195.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress,appraisal, and coping . New York: Springer.

Moskowitz, J. T., Hult, J. R., Bussolari, C., & Acree, M. (2009). What works in coping with HIV? A meta-analysis with implications for coping with serious illness. Psychological Bulletin, 135(1) , 121.

Nes, L. S., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2006). Dispositional optimism and coping: A meta-analytic review. Personality and social psychology review, 10(3) , 235-251.

Pascoe, E. A., & Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 135(4) , 531.

Penley, J. A., Tomaka, J., & Wiebe, J. S. (2002). The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Journal of behavioral medicine, 25(6) , 551-603.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1995). Emotion, disclosure, & health. American Psychological Association .

Petrie, K. J., Booth, R. J., & Pennebaker, J. W. (1998). The immunological effects of thought suppression. Journal of personality and social psychology, 75(5) , 1264.

Sarafino, E. P. (2012). Health Psychology: Biopsychosocial Interactions. 7th Ed . Asia: Wiley.

Related Articles

What Is Masking?

Neurodiversity , Emotions

Managing Emotional Dysregulation In ADHD

ADHD Emotional Dysregulation: When Emotions Become Too Much

Emotions , Self-Care

IQ vs EQ: Why Emotional Intelligence Matters More Than You Think

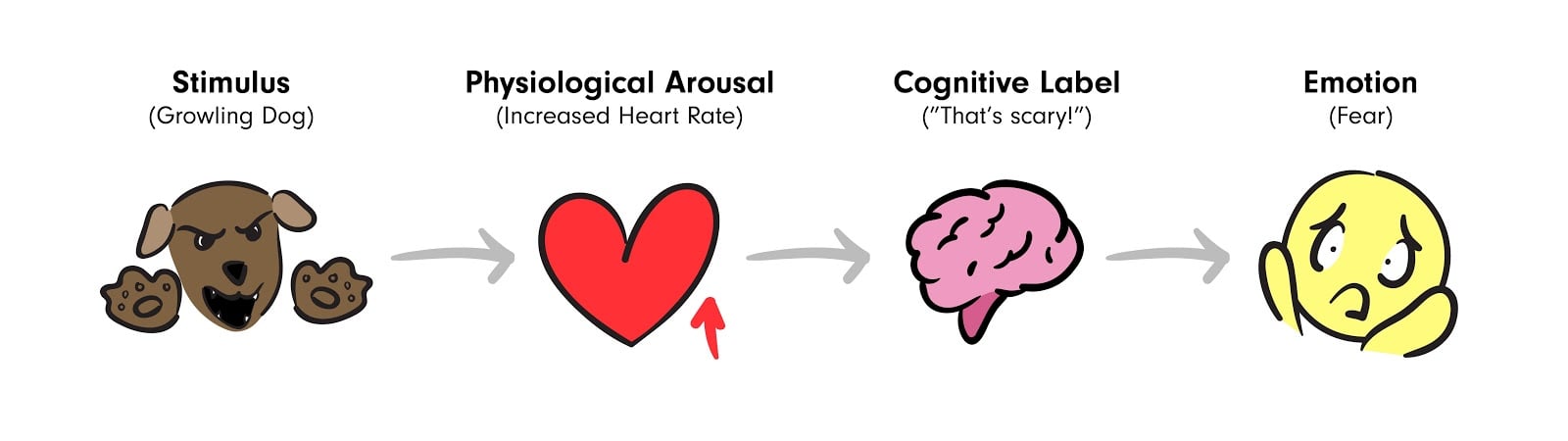

Schachter-Singer Two-Factor Theory of Emotion

Emotions , Personality

The Dark Side of Emotional Intelligence

Stress Management 101: How to Cope Better and Find Relief

Unless you plan to lock yourself in a room for the rest of your life, it’s impossible to exist without at least some level of stress every day, even while you’re on vacation.

“When you feel stress, hormones — such as adrenaline — are released that can improve alertness and performance in the moment,” says Margie Sieka, PhD , a counselor based in Glen Ellyn, Illinois. This response can help your body become more alert, focus better, and even work harder.

RELATED: How Stress Affects Your Body, From Your Brain to Your Digestive System

Stress becomes a problem when it becomes chronic; when instead of coping with the thing that’s stressing you out, you let all those challenging thoughts and feelings percolate. “That’s when it starts to take a toll on your emotional and physical health,” says Jennifer Haden Haythe, MD , a cardiologist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City.

Your move? Be proactive about stress management so that your stress response doesn’t outweigh the stressor you’re facing. You’ll have a set of tried-and-true techniques for dealing with whatever shows up to find relief from your stress.

How to Set Yourself Up to Deal With Stress

Regular self-care practices and behavior modifications can help keep stress from overwhelming you — and scale your stress response in proportion to the stressor.

“It’s important to understand that when it comes to stress and its impact on health , you may want to think about trying longer-term strategies and changes in lifestyle,” says Michelle Dossett, MD, PhD, MPH , an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

A healthy lifestyle — eating well, getting high-quality sleep, staying hydrated, and exercising regularly — can buffer you against the wear and tear of stress, says Holly Schiff, PsyD , a clinical psychologist with Jewish Family Services of Greenwich in Connecticut. These steps don’t eliminate the challenge, but they will ensure your strongest, calmest, most rational self shows up to meet whatever obstacle you’re facing.

RELATED: The Ultimate Expert-Approved Diet Plan for a Happier, Less-Stressed You

If, for example, you got a good night’s sleep, you spent an hour doing a workout you love after waking up, and you ate a satisfying breakfast, a midmorning crisis at the office is likely going to feel a little less hair-raising than if you were feeling sleep deprived, hungry because you skipped breakfast, and burned out because you haven’t made it to your favorite Pilates instructor’s class in so long.

As far as exercise goes, just make sure it’s something you enjoy. “Exercise doesn’t have to be intense, and you don’t have to join a gym,” Dr. Haythe says. “I tell my patients to buy a pair of sneakers and start walking for 15 to 20 minutes a day.”

RELATED: Why Exercise and Sleep Are Your Ultimate Defense Against Stress

How to Get Relief When You’re Going Through a Stressful Time

Some stressors get resolved relatively quickly and go away (a travel delay, a deadline at work, a toddler’s temper tantrum, to name a few). Other stressors are ones you have to cope with for long stretches of time, such as going through a divorce or breakup, managing a difficult health diagnosis, or looking for a new job. It could even be something exciting — say if you’re preparing for an upcoming move or planning a wedding.

“ Anything that puts high demands on you can be stressful — even positive things,” Dr. Schiff says. On these occasions, sticking to your usual routines can be helpful.

“There is some reassurance in knowing what’s going to happen and when, not to mention that routines promote positive physical and mental health,” Schiff says. “When faced with events that are scary and largely out of our control, it’s important to realize what you can control.”

It’s also important to acknowledge the extra stress you’re feeling and perhaps take your stress management up a notch.

It’s also a good idea to lean on your social circle in times like these. “Spending time with family or friends who make you feel good, or finding a community with whom you share interests or spiritual beliefs, reduces stress,” says Alka Gupta, MD , the chief medical officer at Bluerock Care in Washington, DC.

Establishing a mindfulness practice may help. “Meditation is an important tool that can support us during those [stressful periods],” says Kelley Green Johnson , a mindfulness coach based in Brooklyn, New York. “Grounding ourselves through our breath can bring calmness and peace to our mind, instead of letting the outside world take control of our emotions and feelings.”

“Learning to stay in the present moment breaks the train of everyday thought that can stress you out,” Dr. Dossett says. “Whether you’re meditating, doing yoga, or taking a walk, if you pay attention to your body and your breath, you can’t be worrying about something else.”

Do keep in mind: Your stress management tools should serve you and not add to the stress. “It should feel natural and enjoyable and should fit into your routine relatively easily,” Dr. Gupta says. That means you should choose stress management practices that are affordable and convenient and that fit into your schedule.

How to Better Cope With Stress in the Moment

Pay attention to these signs. “It is important to recognize the physiological signs of stress and address these symptoms in the moment to alleviate the potential harmful effects,” Dr. Sieka says.

The goal of stress management here is to acknowledge the feeling and then dial down those physiological changes and approach the challenge rationally with your mind (unless you truly do need to flee a fire or fight a bear), explains Melissa Dowd , a therapy lead at PlushCare, a virtual health platform.

If your reaction to stress (increased blood pressure, heightened alertness, and so on) sticks around even after the trigger is gone (you catch the train, the presentation goes just fine), short-term stress can become chronic, Dowd says.

“Stress that is not handled well and continues without relief can lead to chronic stress and contribute to physical concerns, such as headaches, gastrointestinal issues, and high blood pressure, and mental health problems, such as irritability, depression, anxiety, and substance use,” Sieka says.

Dowd says some people are more prone to chronic stress. “This can be due to genetics, life experiences, and unhealthy coping mechanisms,” she says.

It’s good to have a few tricks up your sleeve that can help you de-escalate stressful situations quickly, such as squeezing a stress ball, cueing up a mindfulness app, and doing deep-breathing exercises.

The point of these in-the-moment quick fixes is that they help turn off the body’s fight-or-flight stress response, so that you can more calmly cope with the challenge at hand and so that stress doesn’t become chronic, Dowd says.

If you find yourself frequently feeling that fight-or-flight response, or it’s difficult to manage, consider seeking help from a mental health provider (or asking your doctor if you don’t have a mental health provider).

RELATED: How to Bust Stress in 5 Minutes or Less

Everyday Health follows strict sourcing guidelines to ensure the accuracy of its content, outlined in our editorial policy . We use only trustworthy sources, including peer-reviewed studies, board-certified medical experts, patients with lived experience, and information from top institutions.

- Stress. Cleveland Clinic .

- U.S. Medical Students Who Engage in Self-Care Report Less Stress and Higher Quality of Life. BMC Medical Education .

- Regular Exercise Is Associated With Emotional Resilience to Acute Stress in Healthy Adults. Frontiers in Physiology .

- Stress Relievers: Tips to Tame Stress. Mayo Clinic .

- Center for Mindfulness: FAQs. UMass Memorial Health .

- 5 Ways to Reduce Stress Right Now. Queensland Health .

- Understanding the Stress Response. Harvard Health Publishing .

- Stress. Cleveland Clinic . January 28, 2021.

- Stress Relievers: Tips to Tame Stress. Mayo Clinic . March 18, 2021.

- Hoge EA, Bui E, Palitz SA, et al. The Effect of Mindfulness Meditation Training on Biological Acute Stress Responses in Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Psychiatry Research . April 2018.

- 5 Ways to Reduce Stress Right Now. Queensland Health . March 12, 2018.

- Understanding the Stress Response. Harvard Health Publishing . July 6, 2020.

- Ayala EE, Winseman JS, Johnsen RD, Mason HRC. U.S. Medical Students Who Engage in Self-Care Report Less Stress and Higher Quality of Life. BMC Medical Education . August 6, 2018.

- Childs E, de Wit H. Regular Exercise Is Associated With Emotional Resilience to Acute Stress in Healthy Adults. Frontiers in Physiology . May 1, 2014.

- Menschner C, Maul A. Key Ingredients for Successful Trauma-Informed Care Implementation. Center for Health Care Strategies . April 2016.

How to Deal With Anxiety: 5 Coping Skills and Worksheets

Recognizing that you are experiencing anxiety is the first healthy step toward learning how to manage and cope with your feelings.

Symptoms of anxiety and stress include:

- Your heart is pounding for no good reason.

- Your mind is noisy, flitting from one thought to the next.

- You feel exhausted.

In this post, we will look at different ways to tackle anxiety, including:

- Cognitive strategies

- Physical strategies

- Emotional support strategies

All these strategies are accessible, easy to implement, and flexible. Some methods are more appropriate for children, others for adults, and can be easily used at home or work. You can try each strategy to see which works best for you.

Before we take a look at how we can tackle anxiety, we thought you might like to download these three Resilience Exercises for free . These engaging, science-based exercises will help you effectively deal with difficult circumstances and give you the tools to improve the resilience of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

10 simple ways to deal with anxiety, coping techniques and strategies, 5 worksheets and handouts, useful activities and exercises, anxiety coping for teens and students: 3 games, assessing coping skills: two tests.

- 4 Tips for Coping With Social Anxiety

2 PositivePsychology.com Tools

A take-home message.

It’s important to note that these coping strategies are not passive and won’t happen by themselves, without your attention and care.

Think of it like going to the gym; to improve your strength and endurance, you need to work out regularly. But to work out regularly, you need to make the time and monitor how you feel. If you’re feeling tired, you might complete an easier exercise session that day, but you can work harder when you feel mentally strong . Use this same approach when dealing with anxiety.

Strategies to cope with anxiety

When we feel stressed out or anxious, it’s very easy to let our other needs slide to the wayside. In the book, Coping with Anxiety: Ten Simple Ways to Relieve Anxiety, Fear and Worry , authors Bourne and Garano (2016) provide the following 10 strategies, some of which echo the bottom tiers of Maslow’s (1954) hierarchy of needs.

- Relax your body and muscles, and control your breathing. You can do this through exercises such as yoga, guided meditation, mindful meditation , and breathing exercises .

- Use visualizations, music, and meditation to relax and ease your mind.

- Change your thinking so that you consider other alternatives and solutions to the situation that is causing anxiety.

- Consider facing what you are afraid of so that you can learn to recognize that your concerns are fleeting and see that your imagined outcome is not guaranteed.

- Get regular exercise so that you can sharpen your mind, learn to push through pain and exhaustion, get stronger, and have fun.

- Eat mindfully and maintain a healthy, moderate diet.

- Make time for yourself to recharge. This includes getting a good night’s sleep.

- Simplify your life so that you can adapt to stressful situations and avoid unnecessary (and avoidable) causes of stress.

- Do not go down the rabbit hole of worry. If you are aware that you are starting to worry, find a way to stop it.

- Finally, develop a set of strategies to use when you’re feeling anxious at a particular time so that you can cope with it in the moment (e.g., calling your friend immediately, doing some physical exercise, doing a breathing exercise, etc.).

Only familial needs are considered part of the adaptive coping strategies for dealing with anxiety, which are discussed below. However, ensuring that your basic needs are fulfilled will help you feel better prepared to handle anxiety and stress. For example, physical exercise can help with anxiety (Jayakody, Gunadasa, & Hosker, 2014).

List of adaptive coping strategies

Coping strategies are methods for addressing the impact of upsetting, anxiety-provoking, or stressful events (Cooper, Katona, Orrell, & Livingston, 2008). Coping strategies can be further classified into similar clusters of strategy, for example:

- Emotional or emotion-focused strategies (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), also referred to as emotional support and acceptance-based strategies (Li, Cooper, Bradley, Shulman & Livingston, 2012)

- Problem-focused strategies or solution-focused strategies (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984)

- Dysfunctional strategies (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989)

In a meta-analysis of coping strategies used by carers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Li et al. (2012) found that:

- Dysfunctional coping strategies did not affect anxiety development.

- Emotional support strategies and acceptance-based strategies were associated with lower anxiety.

- Surprisingly, solution-based strategies were associated with more anxiety, but this relationship is based on only one study and should be interpreted with caution.

Anxiety and depression often occur together. In the same meta-analysis, Li et al. (2012) found that dysfunctional coping strategies predicted the development of depression. In contrast, emotional-support strategies and solution-based strategies had a protective nature and were not associated with the development of depression.

Now that we understand the relationship between dysfunctional coping and depression, let’s take a look at useful coping strategies.

Emotion-focused strategies (including acceptance-based strategies)

These strategies aim to change and deal with how we feel when confronted with a stressor.

Examples include:

- Turning to other people for emotional support and talking about your feelings.

- Looking for ways that you have changed as a person in a good way.

- Changing your viewpoint about the stressor by looking for positive things that have come from it.

- Turning to prayer or other activities (e.g., meditation) for added support and finding comfort in your religion or life philosophy.

Solution-focused strategies

These types of strategies aim to change the reason for the source of the stress.

- Active coping strategies, such as trying to take action to change the situation.

- ‘Planful’ problem solving, such as concerted efforts to make necessary changes or designing a ‘plan of action’ to address the situation.

- Logical analysis, which refers to identifying multiple ways to change the situation and other solutions or changes if the first solution falls through.

- Active behavioral changes, which refers to making a plan and following it through. The proposed plan must be accompanied by behavior; for example, taking the time to implement the solution.

Dysfunctional strategies

Dysfunctional strategies are ineffective strategies that are less likely to help. You should not engage in these strategies. Examples of dysfunctional strategies include:

- Denial or denying the existence of the event or the way you feel

- Accepting responsibility by criticizing yourself

- Avoidance, such as avoiding other people

- Emotional discharge, such as venting your emotions

5 Anxiety coping strategies you can use right now – MedCircle

At PositivePsychology.com, there are various worksheets and handouts that help cope with anxiety. Here is a list of the most helpful ones.

Breathing exercise sheets

These two breathing exercises will help teach you how to practice mindful breathing. Mindful breathing can be beneficial when you need to take a break and gather your thoughts. These exercises can be easily implemented in a parked car, home, bath, or any other environment. Keep this exercise as one of your go-to’s for when you need to cope with anxiety immediately.

- Breath Awareness

- Anchor Breathing

Cognitive strategy exercise sheets

These exercises are great to use when trying to change your thinking about a particular event that makes you feel stressed out.

An effective coping strategy is to consider alternatives to the stressful event and to reframe it as positive. Often the anxiety we feel about a particular event is unfounded and linked to only one outcome; there may be many positive outcomes possible.

The What If? Bias worksheet is a good starting point to help you change how you think about the particular stressful event causing you anxiety.

The next two worksheets are very similar, but the second sheet is more in-depth than the first. Both will help you consider solutions to the current thing that is causing you anxiety. Forming a plan, listing the obstacles, and possible solutions are effective strategies for coping with anxiety.

In the Coping: Stressors and Resources worksheet, you need to list what you think is causing you anxiety and then consider the coping resources you have to tackle the problem.

To help you foresee possible challenges, you also need to consider the potential obstacles that you might encounter and how to overcome those obstacles. This worksheet can also be easily written up in a journal so that you don’t need to print it out multiple times.

The Decatastrophizing Worksheet can be useful when you feel incredibly anxious about a specific event.

Physical exercises

First, make time to exercise regularly. Find an exercise that you enjoy. It can be strenuous (e.g., running or cycling) or less strenuous (e.g., walking, hiking, or yoga), performed alone or with someone else.

Having a physical activity like this in your toolbox of coping strategies will better buttress you against the effects of anxiety. It can also give you opportunities to recharge, spend time with other people, and be outside in nature.

Other physical exercises that are good to practice include mindful meditation and breathing exercises. Research shows that mindfulness is a useful strategy for dealing with anxiety, which you can read more about in the article 7 Great Benefits of Mindfulness in Positive Psychology . Breathing exercises can also help center you and make you feel calm. You don’t need to wait until you feel anxious to practice these exercises.

Cognitive exercises

There are many cognitive strategies for coping with anxiety. First, practice reframing negative situations as positive events. For example, if you locked yourself outside your house, consider what you could learn and how you could prevent this in the future. Maybe you learned that you were able to handle the unexpected worry very well or that you were able to call your neighbor to help you.

Secondly, take the time to foresee the event cognitively. Consider alternative outcomes other than the worst-case scenario you’re worried about. Think about what can make you feel better and ensure you are prepared for other possible hiccups.

For example, if you are anxious about an upcoming work trip:

- Make a list of all possible outcomes (positive and negative).

- Consider what you need to do to feel less anxious (e.g., arrange a babysitter or make a list of things to pack).

- Consider possible obstacles that might occur and solutions to overcome them (e.g., the babysitter needs a list of emergency phone numbers; pack your bag the night before).

Finally, delegate responsibilities and lean on other people for emotional support. You do not live in a vacuum, and you can turn to your friends and family for support. List your friends and family who you feel comfortable talking to, and let them know if you feel anxious.

If your anxiety is linked to your workload or responsibilities, then delegate these to other people. If your anxiety is very severe, consider seeing a professional.

Download 3 Free Resilience Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients to recover from personal challenges and turn setbacks into opportunities for growth.

Download 3 Free Resilience Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Here is a list of useful exercises and worksheets that can help children and teenagers cope with anxiety.

The first worksheet, Meditation Grounding Scripts for Children , details a meditation exercise for older and younger children. With regular practice, children will learn how to practice meditation. Initially, this exercise would work better if an adult (e.g., a parent or teacher) goes through the steps and guides the child.

The second worksheet, Noodle Caboodle , teaches children muscle relaxation techniques. This worksheet needs a parent or a teacher to guide the child through the exercises. With time, children can learn to use these techniques without guidance, and it is very powerful when used with the meditation worksheet above.

Cognitive and emotional exercises

The worksheet Inside and Outside helps children articulate the way they feel and how they can change their thinking (e.g., reframing an event or thoughts for positive outcomes). This exercise is currently more suitable for younger children, but it could be easily adapted to suit older children.

Some of the exercises described previously are also appropriate for teenagers and young adults.

Brief COPE (and COPE)

The original COPE inventory contains 15 scales (Carver et al., 1989); the Brief COPE is a much shorter version (Carver, 1997). It consists of only 28 items that measure 14 scales.

The respondent must indicate how often they have engaged in that particular activity for each item or question. The responses are made on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 to 3, with 0 meaning ‘I haven’t been doing this at all,’ and 3 meaning ‘I’ve been doing this a lot.’ You can read more about the brief COPE scale in our article dedicated to Coping Scales .

Ways of Coping questionnaire

Richard Lazarus was the first researcher to focus on coping strategies for anxiety and, together with Susan Folkman (1980), created the original Ways of Coping Questions. The questionnaire has gone through multiple revisions since then (in 1985 and 1988). The 1985 version is freely available and has been validated with two different samples (middle-aged adults and college-aged students).

In total, the questionnaire contains 66 questions, each describing a specific behavior, thought, or method that could be used for coping. Respondents must indicate the degree that they engage in each behavior, on a scale from ‘Not used’ to ‘Used a great deal’ (0 to 4).

The questions measure eight different categories of coping strategies, and scores of each category are calculated by summing the responses (from 0 to 4) for the different questions that comprise that category.

4 Tips for Coping with Social Anxiety

Social anxiety is a particular type of anxiety linked to social events and the fear of being judged or scrutinized by other people (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some researchers and clinicians believe that social anxiety is linked to how we feel and think about a particular event, rather than the nature of the event itself (Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 2005).

Different types of social anxiety treatments have been proposed, including cognitive behavioral therapy, medications, and exposure therapy (Rodebaugh, Holaway, & Heimberg, 2004).

Many of the techniques already described are also appropriate for social anxiety; for example:

- Consider the positive outcomes of a social setting that you feel anxious about; for example, you will see your friends, enjoy a new restaurant, or learn a new skill.

- Consider other possible outcomes, positive and negative, and think about how you will overcome them. For example, if you believe that you will forget what to say in a presentation, make speaker notes, practice your presentation, or consider topics you are looking forward to talking about with your colleagues.

- Set up a support system. Go to the social event with a friend, tell a friend about the social event, and arrange that you text them before and afterward.

- If you need a short break to calm your emotions, go to a private space such as a bathroom and practice breathing exercises.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

PositivePsychology.com offers additional tools for coping with anxiety that may interest you.

The Reverse The Rabbit Hole worksheet is easily implemented and can be used as a long- or short-term solution. In this exercise, the client is asked to challenge their “What If?” thinking by coming up with equally plausible positive outcomes for anxiety-inducing scenarios.

With regular practice, the client learns how to challenge maladaptive thinking with a more positive and realistic mindset.

With the Coping Skills Inventory , clients can learn about six different coping skills: Thought Challenging, Releasing Emotions, Practicing Self-Love, Distracting, Tapping Into Your Best Self , and Grounding . The client is provided with a two-column table; alongside an outline of each skill, they are asked to list some ways that they feel they could apply these skills when facing a challenging or difficult situation.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others overcome adversity, this collection contains 17 validated resilience tools for practitioners . Use them to help others recover from personal challenges and turn setbacks into opportunities for growth.

There are many tools you can use with anxiety therapy . Some of these are solution-based strategies; others are emotional-based strategies.

Regardless, it is essential to put other measures in place that are not directly related to solving immediate feelings of anxiety. For example, engaging in regular exercise will help you get regular and good-quality sleep, motivate you to eat healthily, and ensure you make time for yourself.

As you learn to recognize how anxiety manifests in your body, mind, and life, the measures you put in place to help you deal with anxiety will also get better.

Dealing with anxiety is not a panacea; you will not suddenly be free of anxiety. But you will become stronger and better at coping with it. So be kind to yourself, and try not to judge yourself when you feel like you’re not doing as well. You are doing the best that you can with what you have.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Resilience Exercises for free .

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) . American Psychiatric Pub.

- Beck, A. T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. L. (2005). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective . Basic Books.

- Bourne, E. J., & Garano, L. (2016). Coping with anxiety: Ten simple ways to relieve anxiety, fear, and worry . New Harbinger Publications.

- Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol is too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine , 4 (1), 92.

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 56 (2), 267.

- Cooper, C., Katona, C., Orrell, M., & Livingston, G. (2008). Coping strategies, anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: A Journal of the Psychiatry of Late-Life and Allied Sciences , 23 (9), 929–936.

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980) An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 21 , 219–239.

- Jayakody, K., Gunadasa, S., & Hosker, C. (2014). Exercise for anxiety disorders: Systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine , 48 (3), 187–196.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping . Springer.

- Li, R., Cooper, C., Bradley, J., Shulman, A., & Livingston, G. (2012). Coping strategies and psychological morbidity in family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders , 139 (1), 1–11.

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personalit y. New York, NY: Harper.

- Rodebaugh, T. L., Holaway, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (2004). The treatment of social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Revie w, 24 (7), 883–908.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Dear Doctor Nortje, Thank you very much for your articles and work, especially this one on dealing with anxiety. I am a former member of a very destructive religious cult and suffer from much anxiety and depression at times. Materials like the ones you work on are an immense help. Please pray for us and keep up your much needed great work. I’m a survivor by helpers like you. Thank you and may God bless you. Sincerely, Thomas

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Vicarious Trauma: The Silent Impact on Therapists

Vicarious trauma refers to the impact of repetitive encounters with indirect trauma while working as a helping professional. Most clients who attend psychotherapy will share [...]

CPTSD: Understanding Complex Trauma & Its Recovery

As we face the worrying increase of environmental events, pandemics, and wars across the globe, the topic of trauma is extremely relevant across various contexts. [...]

9 Childhood Trauma Tests & Questionnaires

Childhood trauma is a difficult topic to navigate. We don’t like to think, or talk, about children being hurt. But if we’re working with clients [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (53)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (22)

- Positive Education (48)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (45)

- Resilience & Coping (39)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Resilience Exercises Pack

Problem-Focused Coping: 10 Examples and Definition

Chris Drew (PhD)

Learn about our Editorial Process

Problem-focused coping refers to stress management strategies to deal with stress that involves directly confronting the source of stress to eliminate or decrease its impact.

This can involve developing a more constructive way of interpreting life events, formulating an action plan to build stress management skills, or modifying personal habits.

For example, a person who has a problem-focused coping orientation might write down their key obstacle and develop a list of actionable milestones for overcoming the problem.

Problem-Focused Coping Definition

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) make a distinction between problem-focused and emotion-focused coping :

“a distinction that we believe is of overriding importance, namely, between coping that is directed at managing or altering the problem causing the distress and coping that is directed at regulating emotional response to the problem” (p. 150).

Schoenmakers et al. (2015) defined problem-focused coping as:

“…all the active efforts to manage stressful situations and alter a troubled person-environment relationship to modify or eliminate the sources of stress via individual behavior” (p. 154).

Because stress is so damaging, every year since 2007, the American Psychological Association has commissioned an annual Stress in America survey.

And every year, the survey reveals that a majority of Americans have anxiety regarding numerous dimensions of life, including: concerns about the government, civil liberties , economic conditions, crime and violence, and the nation’s future.

Problem-Focused Coping Examples

- Identifying Sources of Stress: The first step to solving a problem is to know what it is. Therefore, making a list of specific events that create stress will allow a person to take the next step and devise a solution.

- Studying to Reduce Test Anxiety: Committing to studying at least 90-minutes a day during the week prior to an upcoming exam will reduce test anxiety by becoming better prepared.

- Changing Careers: When a person realizes that their job is a major source of stress, they may decide on a career change. Sometimes this can be accomplished right away, or may require returning to school.

- Changing Social Circles: Spending time with people that are negative can create a lot of stress. So, changing the people in our circle of friends can eliminate a lot of stress from constantly being around so much negativity.

- Hiring a Public Speaking Coach: Hiring a professional public speaking coach can help a person develop several techniques to improve one’s articulation and persuasiveness, ultimately leading to a more engaging presentation.

- Changing Unhealthy Eating Habits: Food can have a tremendous impact on how we feel. Consuming healthy food makes the body feel good, which then helps reduce stress.

- Not Working on the Weekends: Feeling stressed and anxious 7 days a week is very destructive. Making a firm rule to now work on Saturday and Sundays will give you a break from the stress of work and keep your mind fresh and ready to go on Monday.

- Time Management: Managing time more efficiently improves productivity. Making a to-do list and prioritizing each task will allow a person to get more done in less time.

- Going Back to School: Being passed over for promotion year after year can be difficult to endure. Improving one’s educational background can help a person become more qualified for advancement.

- Learning to Say No: If a major source of stress is due to overwhelming job demands, then an effective strategy to reducing that stress is learning to say no when asked to do extra work.

Case Studies of Problem-Focused Coping

1. setting boundaries.

Boundaries are rules that define the acceptable and unacceptable behaviors of the people in your life. Setting boundaries is a type of problem-focused self-care that lets others know how you expect to be treated. They can exist in one’s personal or professional relationships.

The first step to setting boundaries is to recognize that you have a right to be treated respectfully and fairly by others.

Second, as Erin Eatough, Ph.D. from BetterUp explains, “spend some time reflecting on the area of your life where you’re looking to set the boundary.” It’s better to start small, but focused on those areas that are important to you.”

Next, communicate your boundaries in a polite, but firm manner. This can be a little tricky.

Letting someone know they have over-stepped and made you feel uncomfortable can create quite the awkward moment.

However, Dr. Abigall Brenner from Psychology Today makes a valid point: “Most people will respect your boundaries when you explain what they are and will expect that you will do the same for them; it’s a two-way street.”

This is one reason it is best to set boundaries early in the relationship.

Finally, remember that setting boundaries is an ongoing exercise. People will come and go into your life, so become comfortable with the idea of setting boundaries. Learn to appreciate how it will help you have better relationships with those around you.

2. Coping Strategies and Loneliness

Being lonely is a common experience among older adults in many Western countries. For example, according to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine ( NASEM ), approximately 30% of adults over 45 in the U. S. feel lonely.

To examine how coping strategies might alleviate loneliness, Schoenmakers et al. (2015) conducted face-to-face interviews with over 1,000 adults 61 – 99 years old that had participated in the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA).

Loneliness was measured and each participant was presented with 4 vignettes that described a person that was feeling lonely.

Participants were asked to indicate yes or no to six coping strategies, such as “Go to places or club meetings to meet people” (problem-focused), or “Keep in mind that other people are lonely as well, or even more lonely” (emotion-focused).

The results indicated that “persistently lonely older adults less frequently considered improving relationships and more frequently considered lowering expectations than their peers who had not experienced loneliness previously” (p. 159).

That is, they did not endorse problem-focused strategies, but did endorse emotion-focused strategies.

The researchers explain that “ongoing loneliness makes people abandon to look at options to improve relationships that are costly in time and energy. But because they still want to do something to alleviate their loneliness, they endorse lowering expectations” (p. 159).

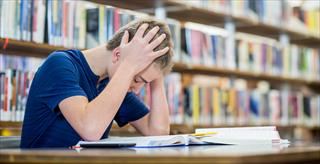

3. Coping Strategies of College Students

Stress among college students comes from a variety of sources. Of course, demanding courses and exams are prevalent. In addition, coping with the transition from secondary school to young adulthood involves being independent, handling finances, and adjusting to a new social environment .

Coping strategies include talking to family and friends, leisure activities , and exercising, as well as less constructive activities such as alcohol consumption (Pierceall & Keim, 2007).

Broughman et al. (2009) surveyed 166 college students attending a liberal arts university in Southern California.

The survey included a coping inventory and measure of stress.

“Although college women reported the overall use of emotion-focused coping for stress, college men reported using emotion-focused coping for a greater number of specific stressors. For both women and men college students, problem-focused coping was used less than emotion-focused coping” (p. 93).

4.Marital Satisfaction of Families with Children with Disabilities

Having children creates both stress and joy in marital relations. While many might assume that having a child with a disability would lead to more stress, research over the last 4 decades has produced inconsistent findings ( Stoneman & Gavidia-Payne, 2006).

Stoneman and Gavidia-Payne (2006) surveyed 67 married couples with children with disabilities.

The survey included a measure of marital adjustment, occurrence of psychosocial stressors , and problem-focused coping strategies.

There were several interesting findings:

- “18.6% of the mothers and 22.9% of the fathers in the sample could be classified as maritally discordant” (p. 6). This is similar to percentages found in the general population.

- “Mothers reported significantly more daily hassles than did fathers” (p. 6).

- “Problem-focused coping did not differ by parent gender” (p. 6).

- “Marital adjustment for mothers was higher when mothers’ hassles/stressors were fewer and when fathers used more problem-focused coping strategies” (p. 7).

- “Fathers reported higher marital adjustment when they had fewer hassles and when they utilized more problem-focused coping strategies” (p. 7).

The researchers explain this pattern through a historical cultural lens :

“Women are more positive about their marriages when their husbands have strong problem-focused coping skills; husbands, on the other hand, do not place relevance on their wives problem-focused coping skills as they assess their marital adjustment” (p. 9).

5. Transactional Model of Stress and Coping

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping was originally proposed by Lazarus and Folkman (1984). The model identifies a process that begins with the perception and interpretation of a life event, and concludes with a reappraisal of the individual’s coping strategy.

Lazarus and Folkman contend that not all stressors will be perceived. If perceived, then the stressor must be interpreted. This interpretation occurs during Primary Appraisal . If the event is perceived as positive or irrelevant, then no stress will occur.

However, if the event is interpreted as dangerous, then a Secondary Appraisal will occur. The individual assesses if they have sufficient resources to overcome the stressor or not. If the answer is yes, then everything is fine.

If the answer is no, then a coping strategy is activated, which will either be problem-focused or emotion-focused.

After the coping strategy has been implemented, a Reappraisal of the situation will ensue and the process may be started all over again.

Problem-focused coping is when an individual engages in behavior to resolve a stressful situation. This can involve changing one’s situation, building skills, or other actions that are directly focused on addressing the root cause of the problem.

Research has shown that college students, married couples with and without children with disabilities, and the elderly experiencing loneliness, will engage in a combination of problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies.

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping identifies the steps that individuals engage when encountering stressful life events.

Because stress is so prevalent in modern life, and is linked to major health conditions, it is a good idea to incorporate both problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies in one’s daily routine.

Brougham, R. R., Zail, C. M., Mendoza, C. M., & Miller, J. R. (2009). Stress, sex differences, and coping strategies among college students. Current Psychology, 28 , 85-97. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-009-9047-0

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25663 .

Pierceall, E. A., & Keim, M. C. (2007). Stress and coping strategies among community college students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 31 (9), 703-712. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920600866579

Schoenmakers, E., van Tilburg, T., & Fokkema, T. (2015). Problem-focused and emotion-focused coping options and loneliness: How are they related? European Journal of Ageing, 12 , 153-161. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10433-015-0336-1

Stoneman, Z., & Gavidia-Payne, S. (2006). Marital adjustment in families of young children with disabilities: Associations with daily hassles and problem-focused coping. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 111 (1), 1-14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[1:MAIFOY]2.0.CO;2

Appendix: Image Description

The image with alt text “graphical representation of the transactional model of stress” depicts a flow chart starting with “life event”. The next step is “perceptual process (event perceived/not perceived)”. If an event is perceived, we move on to the “primary appraisal (interpretation of perceived event)” step. Three options are presented: positive event, dangerous event, and irrelevant event. If it is perceived as a dangerous event, we move onto “secondary appraisal (analysis of available resources)”. Two options are presented: insufficient resources and sufficient resources. If insufficient resources are identified, we move onto the “stress coping strategy” step. The two options are problem-fcused and emotion-focused. The final step is reappraisal, where we apprause is the stragey was successful or failed. This flow chart is based on Lazarus and Folkman (1984).

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Cooperative Play Examples

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Cooperative Play Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Student Support Services

- Subject Guides

Essential Study Skills

- Introduction to Time Management

- Getting Things Done

- Creating a Weekly Schedule

- Creating a Semester Plan

- Planning an Assignment

- Creating a Task List

- Putting it all together

- Additional Resources

- Coping With Stress

- Changing Your Perception of Stress

- Problem Solving To Manage Stress

- Reading with Purpose

- Taking Notes in Class

- Deciding What To Study

- Knowing How to Study

- Memorizing and Understanding Concepts

- Taking Tests & Exams

- Creating and Preparing For a Presentation

- Presentation Anxiety

- Delivering Presentations

- Exploring Career Options

- Identifying Areas of Interest

- Knowing Yourself

- Exploring the Labour Market

- Researching College Programs

- Setting Goals

- Tackling Problems

- Bouncing Back

- Sleep Matters

- Sleep Habits

- Sleep Strategies

- Meeting with Your Group

- Agreeing on Expectations

- Dealing With Problems

- Study in Groups

What is a problem?

A problem is when you are experiencing a particular difficulty but have not found any solution. Problems can be practical or emotional. Often these two types of problems can combine and seem difficult to solve. This module will explain strategies to help solve practical problems.

How To Solve Practical Problems

- Video Transcript - How to Solve Practical Problems

Problem solving involves strategies that can help you cope with problems in a productive way. Use the 5 step outline below to help you solve a challenge you are currently dealing with.

- Identify your problem and what you would like to be different.

- Brainstorm all the ways that you could solve the problem.

- T hink about your choices and decide which ones are possible, reasonable, and doable.

Follow through with the choices that are achievable.

- Evaluate your results. Did your actions solve the problem? If your actions have not helped your situation, try acting on one of the other options that you brainstormed.

- << Previous: Changing Your Perception of Stress

- Next: Additional Resources >>

- Last Updated: Jun 10, 2024 2:06 PM

- URL: https://algonquincollege.libguides.com/studyskills

10 Tips to Manage Your Worrying

Almost 1 in 10 people find uncontrollable worrying a distressing affliction..

Posted June 25, 2012 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Do you find that you’re continually fighting with your worries? Do they distress you because you feel controlled by them or that if you don’t worry then something bad might happen? Do your worries pour into your head when you wake up at night? Finally, when you’ve started worrying, do you find it almost impossible to stop?

You are not alone! Almost 1 in 10 people find uncontrollable worrying a distressing affliction that feels as though it has become an inseparable part of their personalities and character. Chronic worrying is often driven by a need to worry to “make sure things will all be OK.” It will affect your mood; it can also have detrimental effects on your relationships, work productivity , and social life .

I’ll talk in later blog posts about some of the causes of chronic worrying. In the meantime, here are 10 tips with useful links that you can try out to help you manage your worrying.

1. Problem-solve, don’t worry : Worrying is normally a very inefficient attempt to problem-solve. So when you worry, try to turn this into useful problem solving by considering what you need to do now to deal with the problem. You might want to have a look at this website which provides a useful guide to developing your practical problem-solving skills.

2. Don’t waste time on “What if..?” questions : Don’t waste time thinking up situations that "might" happen, but in reality are quite unlikely to happen – that is just a misuse of good brain time. Try to spot when you start asking yourself “What if…?” type questions. The vast majority of the scenarios you create using this approach are never likely to happen – so why waste time thinking about them? Have a look at how to handle “What if…?” worrying here .

3. Don’t kid yourself that worry is always helpful : Don’t be fooled into thinking that your worry will always be helpful. If you are a persistent worrier you’ve probably come to use worrying simply to kid yourself that you’re doing something about a problem. This is not an alternative to tackling the problem in practical ways. This journal article will give you some insight into how chronic worriers come to believe that all worrying is useful – when it’s not.

4. Learn to accept uncertainty : Uncertainty is a fact of life, so try to accept that you will always have to live with and tolerate some uncertainty. Unexpected things happen, and accepting this in the longer term will make your life easier and reduce your anxieties. Here’s some useful advice about how to begin accepting and dealing with uncertainty.

5. Always try to lift your mood: Negative moods fuel worrying. Negative moods include anxiety , sadness, anger , guilt , shame , and even physical states such as tiredness and pain. If you must worry, try not to do so when in negative moods because your worrying will be more difficult to control and more difficult to stop. If you find yourself worrying in a negative mood, immediately try to do something to lift your mood. Some examples of how to do this are provided here and here .

6. Don’t try to suppress unwanted worries : When you do start to worry – don’t try and fight or control those thoughts. It is helpful to notice them rather than try to suppress them, because actively trying to suppress thoughts simply makes them bounce back even more! So acknowledge those worrisome thoughts but then move on to doing something more useful.

7. Manage the times when you worry : Become a “smart” worrier. If you find that worrying can be useful but that it just gets out of control, then try to manage your worry by setting aside specific times of day to engage in worrying (e.g. an hour when you’ve finished work). But also take the time to soothe yourself when this period is over, just to get yourself back into balance. This book may be able to help you find ways to soothe yourself after worrying.

8. Change “What if…?” worries to “How can I…?” worries : To be able to manage your worries, you need to understand exactly what they are. Try keeping a worry diary for a week or so. Write down each worry when it occurs – just a sentence to describe it will do. Then later, try and see how many of your worries are “What if…?” type questions. As we mentioned earlier, “What if..?” worries are not helpful. You can try to turn these worries into “How can I…? worries, which is more likely to lead you on to practical solutions (e.g. you could turn a “What if I forget what to say in my interview?” worry into “How can I prepare myself to remember what I need to say in my interview”). You can also go back to tip #2 and use some of the strategies there for handling “What if…?” worries.

9. How not to lose sleep by worrying : Very often your worries may stop you sleeping . You may find yourself running through every possible problem that could arise and trying to think up solutions. All this will do is keep you awake longer, and you’ll end up feeling tired (and probably anxious) the next day. One solution to worries that keep you awake at night is to keep a pen and paper next to the bed. When you wake up worrying, simply write a list of things you need to do tomorrow (including dealing with the worry). You’ll probably find that once the worry has been transferred to that piece of paper, there is now no longer any need to keep it in your head as well. It can be dealt with tomorrow.

10. Stay in the moment : Spending most of your time worrying about things that might happen in the future means that you’ll spend less time enjoying the present and staying in the moment. Acknowledge the worries that enter your head, but don’t engage them. Try to refocus on what you are doing in that moment – watching a TV program, reading a good book, playing with your children. Try some of these tips for disengaging with your worries and staying in the moment.

Follow me on Twitter .

Graham C. L. Davey, Ph.D., is an expert in anxiety and a professor of psychology at the University of Sussex.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

5 Emotion-Focused Coping Techniques for Stress Relief

Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Elizabeth-Scott-MS-660-695e2294b1844efda01d7a29da7b64c7.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Cognitive Distortions

Positive thinking.

Stress management techniques can fall into two categories: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Basically speaking, problem-focused (or solution-focused) coping strategies aim to eliminate sources of stress or work with the stressors themselves.

Meanwhile, emotion-focused coping techniques aid you in becoming less emotionally reactive to the stressors you face. They alter the way you experience these situations so they impact you differently.

Emotion-focused coping focuses on regulating negative emotional reactions to stress such as anxiety, fear, sadness, and anger. This type of coping may be useful when a stressor is something that you cannot change.

Many people think mainly of solution-focused coping strategies as the best way to manage stress. Cutting out the things that seem to cause us stress means we don't need to learn how to alter our responses to any stressors—there will be none left in our lives!

However, it's not entirely possible to cut all stress out of our lives. Some factors in our jobs, our relationships, or our lifestyles are simply prone to creating challenges. In fact, it wouldn't be entirely healthy to eliminate all stressors even if we could; a certain amount of stress is healthy .

Benefits of Emotion-Focused Coping

This is part of why emotion-focused coping can be quite valuable—shifting how we experience potential stressors in our lives can reduce their negative impact. Some key benefits of emotion-focused coping include:

- You don't have to wait to find relief : With emotion-focused coping, we don't need to wait for our lives to change or work on changing the inevitable. We can simply find ways to accept what we face right now, and not let it bother us.

- It reduces chronic stress : This can cut down on chronic stress , as it gives the body a chance to recover from what might otherwise be too-high levels of stress.

- It can improve decision-making : It allows us to think more clearly and access solutions that may not be available if we are feeling overwhelmed. Because stressed people do not always make the most effective decisions, emotion-focused coping can be a strategy to get into a better frame of mind before working on problem-focused techniques.

Emotion-focused coping can help with both emotions and solutions. And the two types of coping strategies work well together in this way. While problem-focused strategies need to fit well with the specific stressors they are addressing, emotion-focused coping techniques work well with most stressors and need only fit the individual needs of the person using them.

Finding the right emotion-focused coping strategies for your lifestyle and personality can provide you with a vital tool for overall stress relief and can enable you to achieve greater physical and emotional health.

Meditation is an ancient practice that involves focusing attention and increasing awareness. It can have a number of psychological benefits , and research has shown that even brief meditation sessions can help improve emotional processing.

Meditation can help you to separate yourself from your thoughts as you react to stress. This allows you to stand back and choose a response rather than react out of panic or fear.

Meditation also allows you to relax your body, which can reverse your stress response as well. Those who practice meditation tend to be less reactive to stress, too, so meditation is well worth the effort it takes to practice.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares some techniques that can help you relax.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Journaling allows you to manage emotions in several ways. It can provide an emotional outlet for stressful feelings. It also can enable you to brainstorm solutions to problems you face.

Journaling also helps you to cultivate more positive feelings, which can help you to feel less stressed. It also brings other benefits for wellness and stress management , making it a great emotion-focused coping technique.

Research has found that positive-affect journaling, a type of expressive writing that involves using journaling prompts to elicit positive feelings, has a beneficial effect on emotion-focused self-regulation.

Cognitive reframing is a strategy that can be used to change how people experience events. For example, rather than thinking of something as stressful, reframing can help you shift your perspective and see it differently.

In order to reframe stressful thinking, you should:

- Notice your thoughts : Being more aware of your thinking can help you become more aware of how your thought patterns influence your emotions.

- Challenge your thoughts : Instead of accepting negative thoughts as facts, actively challenge them. Are they true? Are there other ways of looking at the problem?

- Replace negative thoughts : Once you've challenged your thoughts, actively replace them with something more positive and helpful.

This technique allows you to shift the way you see a problem, which can actually make the difference between whether or not you feel stressed by facing it.

Reframing techniques aren't about "tricking yourself out of being stressed," or pretending your stressors don't exist; reframing is more about seeing solutions, benefits, and new perspectives.

Cognitive distortions are irrational thinking patterns that can increase stress, lead to poor decisions, and lead to negative thinking. For example, emotional reasoning is a type of cognitive distortion that causes people to draw conclusions based on feelings instead of facts. This can cause people to act irrationally and make it more difficult to solve problems.

Recognizing the way the mind alters what you see, including what you tell yourself about what you are experiencing, and the ways in which you may unknowingly contribute to your own problems, can allow us to change these patterns.

Become aware of common cognitive distortions, and you'll be able to catch yourself when you do this, and will be able to recognize and understand when others may be doing it as well.

Being an optimist involves specific ways of perceiving problems—ways that maximize your power in a situation, and keep you in touch with your options. Both of these things can reduce your experience of stress, and help you to feel empowered in situations that might otherwise overwhelm you.

Positive thinking can have a number of benefits, including acting as a buffer against life's stresses. When you see things in a more positive light, you are better able to make decisions without responding from a place of fear or anxiety.

One study found that actively replacing thoughts with more positive ones could reduce pathological worry in people with generalized anxiety disorder. Researchers have also found that focusing on positive emotions can reduce symptom severity in people who have emotional problems.

A Word From Verywell

Not all problems can be solved. You can't change someone else's behavior and you can't undo a health diagnosis. But, you can change how you feel about the problem. Experiment with different emotion-focused coping strategies to discover which ones reduce your distress and help you feel better.

Amnie AG. Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education . SAGE Open Med . 2018;6:2050312118782545. doi:10.1177/2050312118782545

Kristofferzon ML, Engström M, Nilsson A. Coping mediates the relationship between sense of coherence and mental quality of life in patients with chronic illness: a cross-sectional study . Qual Life Res . 2018 Jul;27(7):1855-1863. doi:10.1007/s11136-018-1845-0

Juth V, Dickerson SS, Zoccola PM, Lam S. Understanding the utility of emotional approach coping: evidence from a laboratory stressor and daily life . Anxiety Stress Coping . 2015;28(1):50-70. doi:10.1080/10615806.2014.921912

Wu R, Liu LL, Zhu H, Su WJ, Cao ZY, Zhong SY, Liu XH, Jiang CL. Brief mindfulness meditation improves emotion processing . Front Neurosci . 2019;13:1074. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.01074

Smyth JM, Johnson JA, Auer BJ, Lehman E, Talamo G, Sciamanna CN. Online positive affect journaling in the improvement of mental distress and well-being in general medical patients with elevated anxiety symptoms: a preliminary randomized controlled trial . JMIR Ment Health . 2018;5(4):e11290. doi:10.2196/11290

Clark DA. Cognitive restructuring . In: Hofmann SG, Dozois D, eds. The Wiley Handbook for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, First Edition . John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781118528563.wbcbt02

Rnic K, Dozois DJ, Martin RA. Cognitive distortions, humor styles, and depression . Eur J Psychol . 2016;12(3):348-62. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v12i3.1118

Eagleson C, Hayes S, Mathews A, Perman G, Hirsch CR. The power of positive thinking: Pathological worry is reduced by thought replacement in Generalized Anxiety Disorder . Behav Res Ther . 2016;78:13-8. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.017

Sewart AR, Zbozinek TD, Hammen C, Zinbarg RE, Mineka S, Craske MG. Positive affect as a buffer between chronic stress and symptom severity of emotional disorders . Clin Psychol Sci. 2019;7(5):914-927. doi:10.1177/2167702619834576

By Elizabeth Scott, PhD Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

Stress is a normal reaction to everyday pressures, but can become unhealthy when it upsets your day-to-day functioning. Stress involves changes affecting nearly every system of the body, influencing how people feel and behave.

By causing mind–body changes, stress contributes directly to psychological and physiological disorder and disease and affects mental and physical health, reducing quality of life.

Adapted from the APA Dictionary of Psychology

Stress in America

Stress in America 2023: A nation recovering from collective trauma

The COVID-19 pandemic, global conflicts, racism and racial injustice, inflation, and climate-related disasters are all weighing on the collective consciousness of Americans

Coping with stress

Stress effects on the body

What’s the difference between stress and anxiety?

Healthy ways to handle life’s stressors

How to help children and teens manage their stress

Coping with stress at work

How to cope with traumatic stress

Discrimination: What it is and how to cope

Los distintos tipos de estrés

Treating Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Ethnic and Racial Groups

The Thriving Therapist

Perfectionism in Childhood and Adolescence

Leading Beyond Crisis

Magination Press children’s books

How to Handle STRESS for Middle School Success

A Perfectionist's Guide to Not Being Perfect

What to Do When Mistakes Make You Quake, RE

Journal special issues

Cardiovascular Behavioral Medicine

Secondary Traumatic Stress, Compassion Fatigue, and Vicarious Trauma

The Role of Affect and Emotion to Cope With Stressful Situations

Parent/Guardian Targeted Interventions in Pediatric Psychology

Developing Resilience in Response to Stress and Trauma

Addressing employee burnout: Are you solving the right problem?