Comment rédiger un plan d’essai persuasif pour les étudiants

Un essai persuasif vise à persuader les lecteurs d’être d’accord avec le point de vue des auteurs. Ce type d’écriture comprend différentes techniques pour obtenir le résultat souhaité. Une façon essentielle de rédiger un bon essai persuasif est d’utiliser un plan pour rationaliser le flux et les détails de l’essai entier. Toutefois, pour rédiger un plan de rédaction efficace, vous devez en connaître les composantes. C’est pourquoi nous vous fournirons un guide sur la manière de rédiger un bon résumé. En outre, nous avons quelques exemples que vous pouvez utiliser.

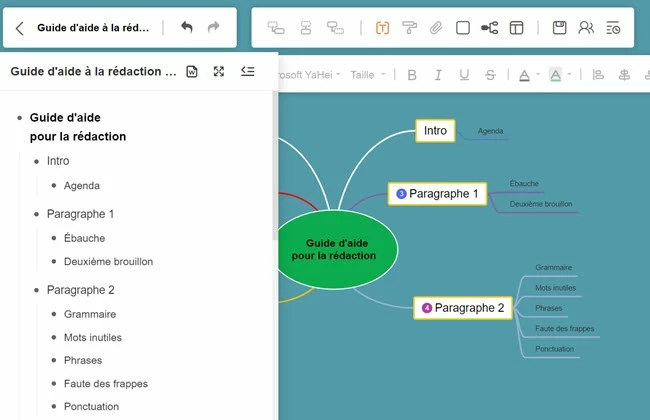

Tutoriel de rédaction d’un essai persuasif

Exemples d’un essai persuasif.

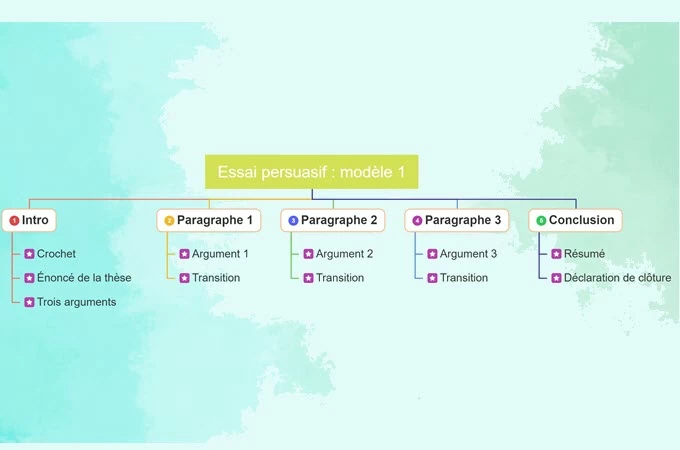

- Essai persuasif : modèle 1

Ce modèle est destiné aux étudiants qui cherchent un moyen de simplifier leur schéma. Il contient toutes les parties essentielles et la structure d’une thèse d’un essai persuasif.

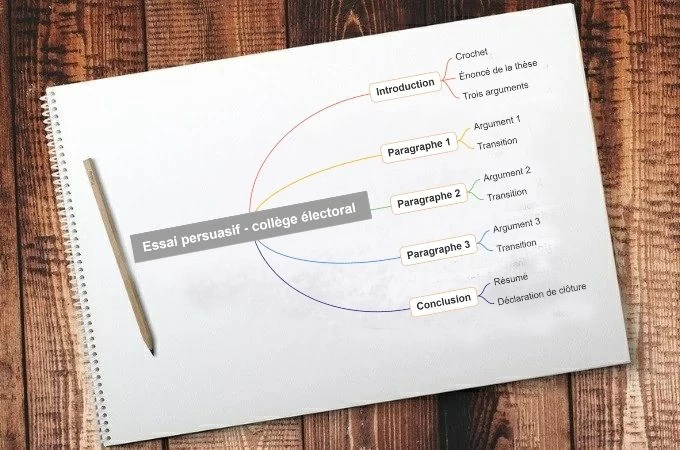

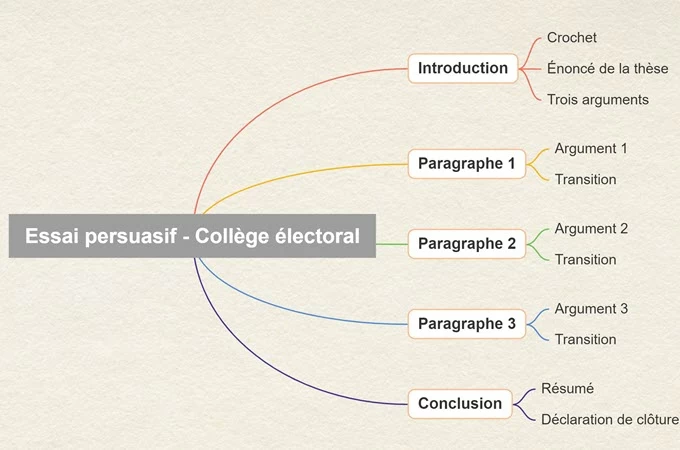

- Essai persuasif : modèle 2

Ce modèle donne un aperçu rapide du processus que doit suivre un collège électoral pour prendre sa décision. De nombreux facteurs doivent être pris en compte, ce qui en fait un outil idéal pour l’élaboration d’un schéma.

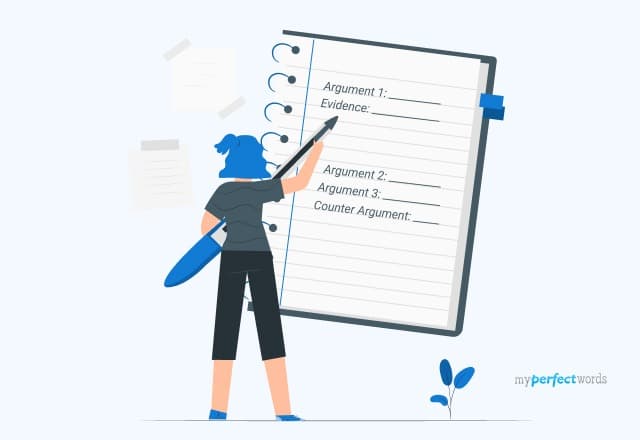

Composantes d’un plan d’un essai persuasif

Partie 1 : Introduction

- Introduction : Il s’agit généralement de votre déclaration d’ouverture. Elle peut contenir votre argumentation mais ne pas être détaillée. Elle est généralement composée de 3 à 5 phrases.

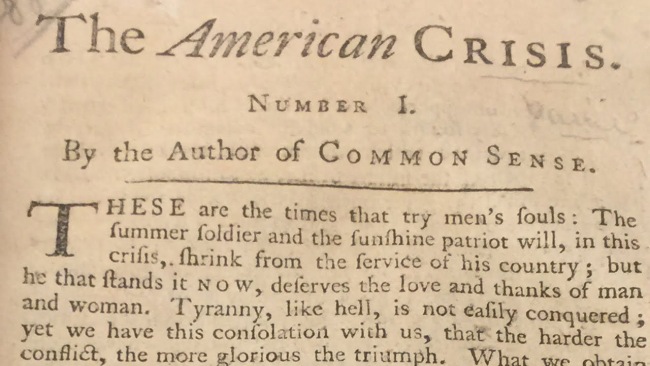

- Accroche : Dans tout argument, il y a toujours une accroche qui attire l’attention des lecteurs. Dans ce cas, le crochet est l’outil qui permettra d’attirer l’attention du lecteur et de piquer ses intérêts. Il peut s’agir d’une citation, d’un exemple ou de n’importe quoi, à condition qu’il soit lié à l’argument principal.

- Argument de thèse : Cette partie montre votre position sur la question. Elle doit contenir votre opinion personnelle et la raison pour laquelle vous l’avez élaborée.

- Trois arguments : Cette partie est celle où vous exposez trois arguments liés au sujet. Ce sera votre outil pour persuader les lecteurs d’être d’accord avec votre point de vue.

Partie 2 : Paragraphe 1

- Argument 1 : Vous devrez écrire un paragraphe sur le premier argument du plan de l’essai de persuasion que vous avez fourni dans la partie précédente. Vous devrez fournir des exemples solides pour prouver votre point de vue. Au moins trois exemples sont nécessaires pour construire un argument solide et un sentiment de crédibilité.

- Transition : Cette partie est nécessaire pour donner une brève introduction à l’argument suivant. Cela permettra aux lecteurs d’avoir une idée générale de ce qui va suivre.

Partie 3 : Paragraphe 2

- Argument 2 : Revenez à la première partie et cherchez le deuxième argument que vous avez écrit. Comme pour la partie précédente, vous devrez écrire un paragraphe à ce sujet, et donner des exemples concrets.

- Transition : Fournissez une déclaration qui montre l’idée suivante qui est liée à l’argument actuel.

Partie 4 – Paragraphe 3

- Argument 3 : Enfin, rédigez un paragraphe sur le dernier argument, et citez également quelques exemples.

- Transition : Conduire à la conclusion

Partie 5 – Conclusion

- Résumé : donnez un aperçu de l’ensemble du plan en reformulant votre déclaration de thèse et les arguments en différents mots.

- Déclaration de clôture : Elle doit être conforme à votre crochet.

Étapes pour rédiger un essai persuasif en ligne

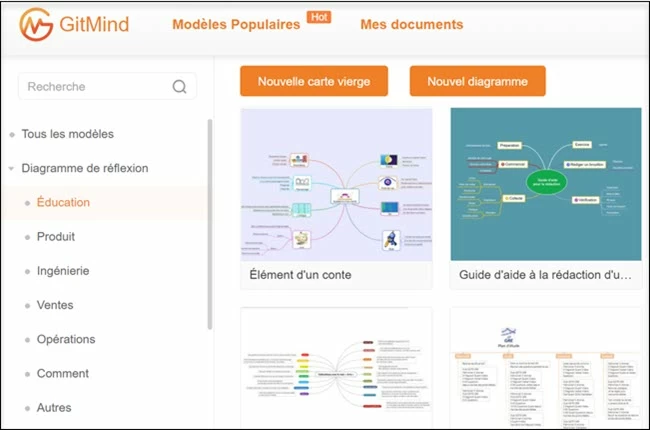

Comme nous le savons tous, il existe de nos jours de nombreuses façons d’écrire un plan de rédaction. Il existe de nombreux outils en ligne qui peuvent facilement vous fournir des modèles prêts à l’emploi. C’est un moyen efficace d’en faire un, car vous n’aurez pas à vous soucier en permanence du format de la dissertation persuasive. Sur ce point, GitMind est un moyen sûr de faire un résumé en quelques minutes. Il est gratuit et contient des tonnes de modèles prêts à l’emploi, ce qui en fait l’un des meilleurs outils actuels. Si vous souhaitez utiliser cet outil, voici les étapes à suivre.

- De là, cliquez sur le bouton « Contour » dans le panneau latéral gauche.

Les essais persuasifs sont l’un des outils d’écriture les plus utilisés au monde. De plus, les auteurs utilisent cette technique dans le monde entier pour prouver un point et persuader leurs lecteurs qu’ils ont raison. C’est pourquoi, pour construire un bon essai, vous devez apprendre à faire un bon plan d’essai persuasif. À cet égard, vous pouvez utiliser des outils en ligne tels que GitMind pour réaliser diverses formes d’aides visuelles comme des schémas et des cartes mentales.

Laissez un commentaire

Commentaire (1).

Ce site Web utilise des cookies qui sont essentiels au fonctionnement du site et à ses fonctions principales. Les autres cookies ne seront placés qu'avec votre consentement. Pour plus de détails, consultez notre Politique des Cookies.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write a Persuasive Essay: Tips and Tricks

Allison Bressmer

Most composition classes you’ll take will teach the art of persuasive writing. That’s a good thing.

Knowing where you stand on issues and knowing how to argue for or against something is a skill that will serve you well both inside and outside of the classroom.

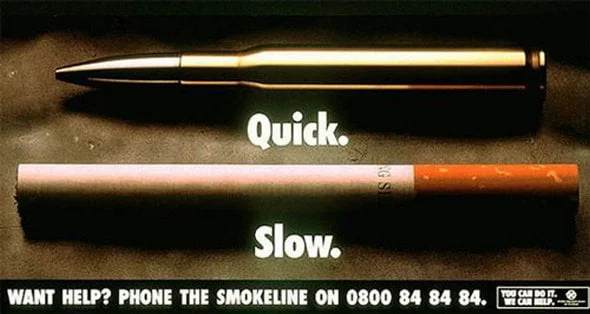

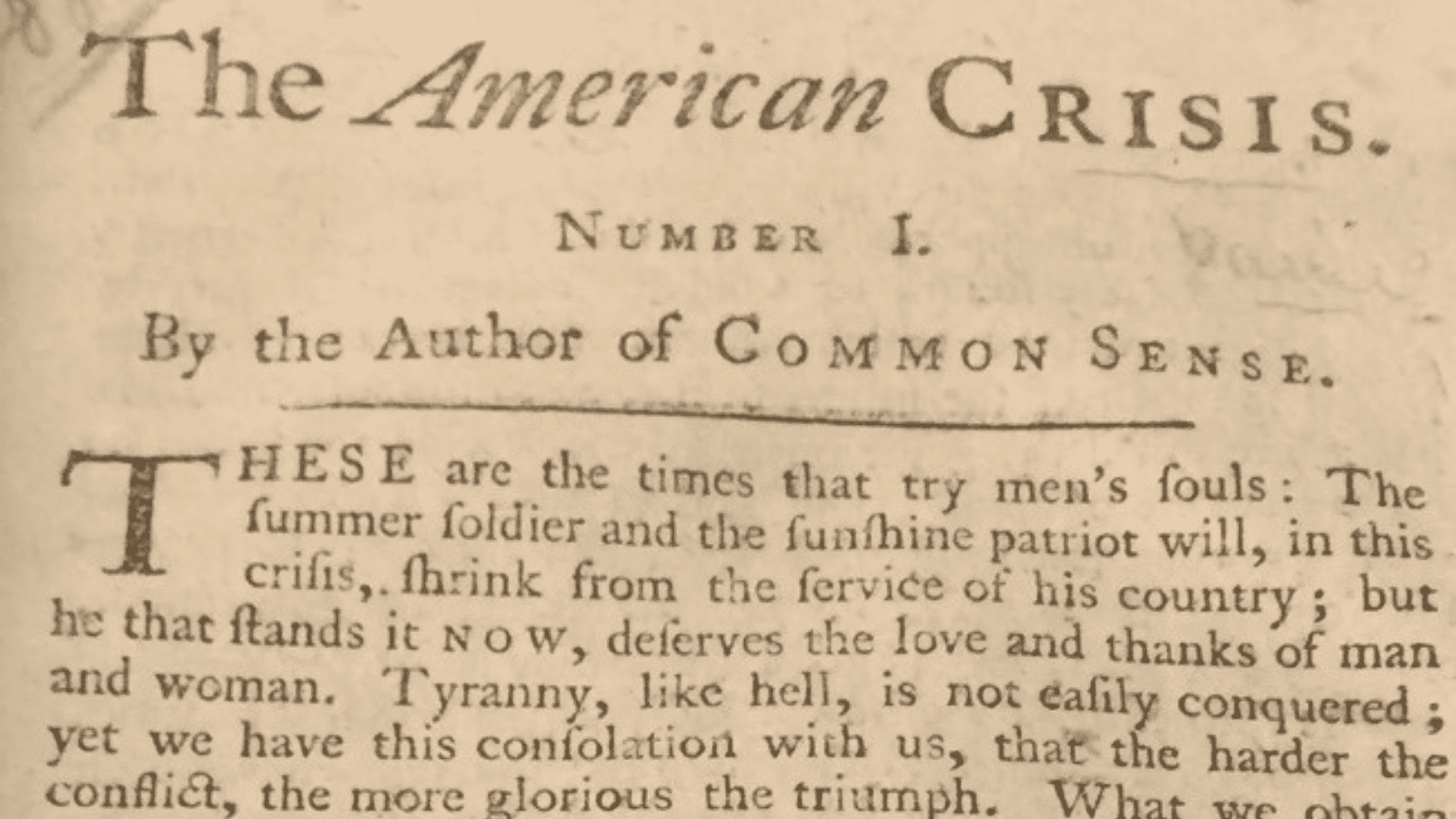

Persuasion is the art of using logic to prompt audiences to change their mind or take action , and is generally seen as accomplishing that goal by appealing to emotions and feelings.

A persuasive essay is one that attempts to get a reader to agree with your perspective.

Ready for some tips on how to produce a well-written, well-rounded, well-structured persuasive essay? Just say yes. I don’t want to have to write another essay to convince you!

How Do I Write a Persuasive Essay?

What are some good topics for a persuasive essay, how do i identify an audience for my persuasive essay, how do you create an effective persuasive essay, how should i edit my persuasive essay.

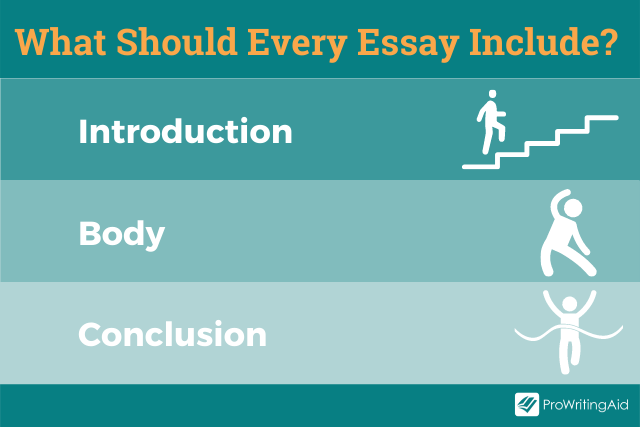

Your persuasive essay needs to have the three components required of any essay: the introduction , body , and conclusion .

That is essay structure. However, there is flexibility in that structure.

There is no rule (unless the assignment has specific rules) for how many paragraphs any of those sections need.

Although the components should be proportional; the body paragraphs will comprise most of your persuasive essay.

How Do I Start a Persuasive Essay?

As with any essay introduction, this paragraph is where you grab your audience’s attention, provide context for the topic of discussion, and present your thesis statement.

TIP 1: Some writers find it easier to write their introductions last. As long as you have your working thesis, this is a perfectly acceptable approach. From that thesis, you can plan your body paragraphs and then go back and write your introduction.

TIP 2: Avoid “announcing” your thesis. Don’t include statements like this:

- “In my essay I will show why extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

- “The purpose of my essay is to argue that extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

Announcements take away from the originality, authority, and sophistication of your writing.

Instead, write a convincing thesis statement that answers the question "so what?" Why is the topic important, what do you think about it, and why do you think that? Be specific.

How Many Paragraphs Should a Persuasive Essay Have?

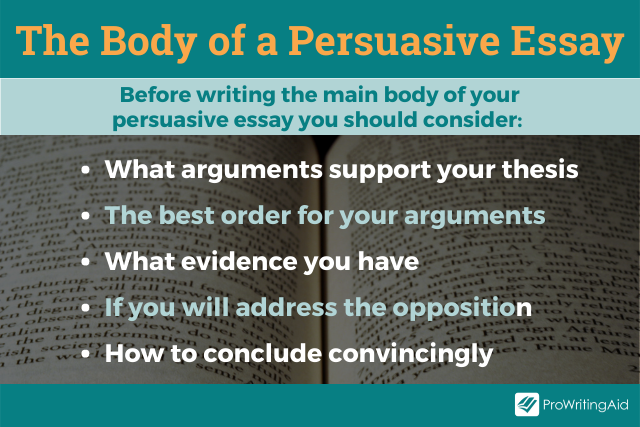

This body of your persuasive essay is the section in which you develop the arguments that support your thesis. Consider these questions as you plan this section of your essay:

- What arguments support your thesis?

- What is the best order for your arguments?

- What evidence do you have?

- Will you address the opposing argument to your own?

- How can you conclude convincingly?

TIP: Brainstorm and do your research before you decide which arguments you’ll focus on in your discussion. Make a list of possibilities and go with the ones that are strongest, that you can discuss with the most confidence, and that help you balance your rhetorical triangle .

What Should I Put in the Conclusion of a Persuasive Essay?

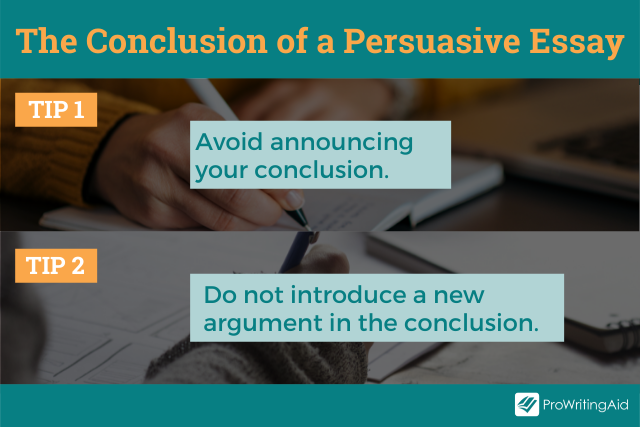

The conclusion is your “mic-drop” moment. Think about how you can leave your audience with a strong final comment.

And while a conclusion often re-emphasizes the main points of a discussion, it shouldn’t simply repeat them.

TIP 1: Be careful not to introduce a new argument in the conclusion—there’s no time to develop it now that you’ve reached the end of your discussion!

TIP 2 : As with your thesis, avoid announcing your conclusion. Don’t start your conclusion with “in conclusion” or “to conclude” or “to end my essay” type statements. Your audience should be able to see that you are bringing the discussion to a close without those overused, less sophisticated signals.

If your instructor has assigned you a topic, then you’ve already got your issue; you’ll just have to determine where you stand on the issue. Where you stand on your topic is your position on that topic.

Your position will ultimately become the thesis of your persuasive essay: the statement the rest of the essay argues for and supports, intending to convince your audience to consider your point of view.

If you have to choose your own topic, use these guidelines to help you make your selection:

- Choose an issue you truly care about

- Choose an issue that is actually debatable

Simple “tastes” (likes and dislikes) can’t really be argued. No matter how many ways someone tries to convince me that milk chocolate rules, I just won’t agree.

It’s dark chocolate or nothing as far as my tastes are concerned.

Similarly, you can’t convince a person to “like” one film more than another in an essay.

You could argue that one movie has superior qualities than another: cinematography, acting, directing, etc. but you can’t convince a person that the film really appeals to them.

Once you’ve selected your issue, determine your position just as you would for an assigned topic. That position will ultimately become your thesis.

Until you’ve finalized your work, consider your thesis a “working thesis.”

This means that your statement represents your position, but you might change its phrasing or structure for that final version.

When you’re writing an essay for a class, it can seem strange to identify an audience—isn’t the audience the instructor?

Your instructor will read and evaluate your essay, and may be part of your greater audience, but you shouldn’t just write for your teacher.

Think about who your intended audience is.

For an argument essay, think of your audience as the people who disagree with you—the people who need convincing.

That population could be quite broad, for example, if you’re arguing a political issue, or narrow, if you’re trying to convince your parents to extend your curfew.

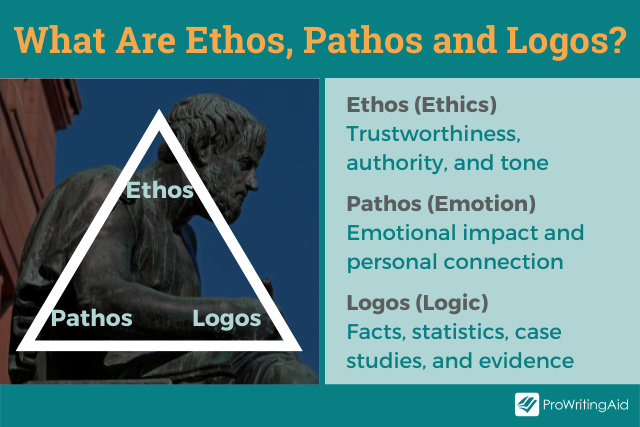

Once you’ve got a sense of your audience, it’s time to consult with Aristotle. Aristotle’s teaching on persuasion has shaped communication since about 330 BC. Apparently, it works.

Aristotle taught that in order to convince an audience of something, the communicator needs to balance the three elements of the rhetorical triangle to achieve the best results.

Those three elements are ethos , logos , and pathos .

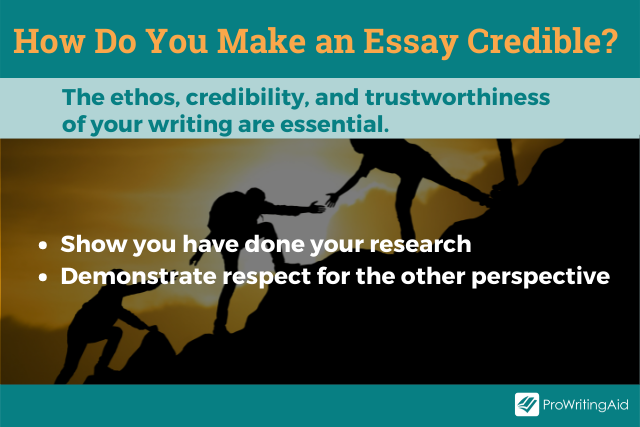

Ethos relates to credibility and trustworthiness. How can you, as the writer, demonstrate your credibility as a source of information to your audience?

How will you show them you are worthy of their trust?

- You show you’ve done your research: you understand the issue, both sides

- You show respect for the opposing side: if you disrespect your audience, they won’t respect you or your ideas

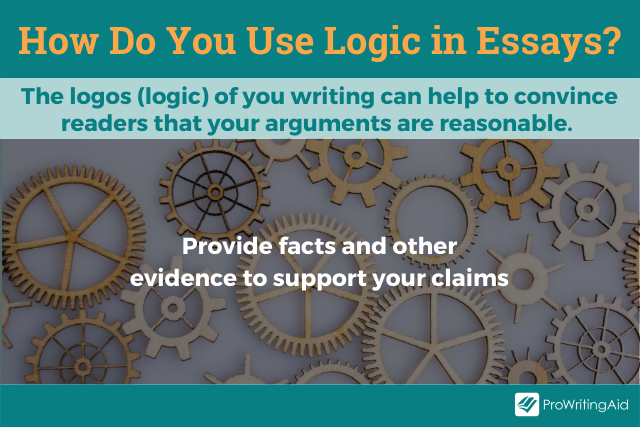

Logos relates to logic. How will you convince your audience that your arguments and ideas are reasonable?

You provide facts or other supporting evidence to support your claims.

That evidence may take the form of studies or expert input or reasonable examples or a combination of all of those things, depending on the specific requirements of your assignment.

Remember: if you use someone else’s ideas or words in your essay, you need to give them credit.

ProWritingAid's Plagiarism Checker checks your work against over a billion web-pages, published works, and academic papers so you can be sure of its originality.

Find out more about ProWritingAid’s Plagiarism checks.

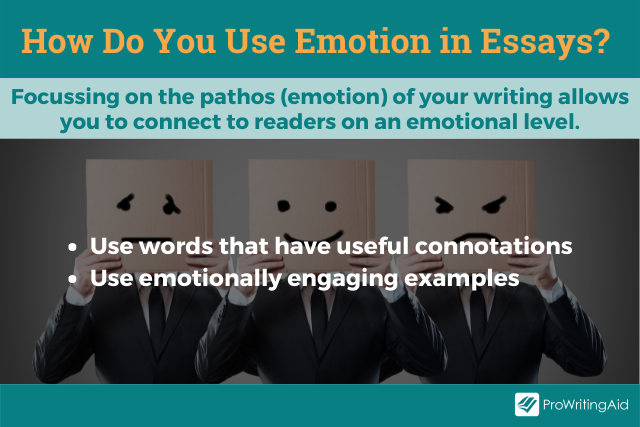

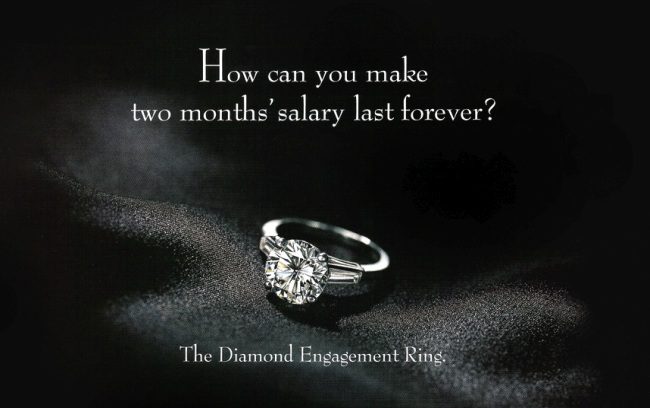

Pathos relates to emotion. Audiences are people and people are emotional beings. We respond to emotional prompts. How will you engage your audience with your arguments on an emotional level?

- You make strategic word choices : words have denotations (dictionary meanings) and also connotations, or emotional values. Use words whose connotations will help prompt the feelings you want your audience to experience.

- You use emotionally engaging examples to support your claims or make a point, prompting your audience to be moved by your discussion.

Be mindful as you lean into elements of the triangle. Too much pathos and your audience might end up feeling manipulated, roll their eyes and move on.

An “all logos” approach will leave your essay dry and without a sense of voice; it will probably bore your audience rather than make them care.

Once you’ve got your essay planned, start writing! Don’t worry about perfection, just get your ideas out of your head and off your list and into a rough essay format.

After you’ve written your draft, evaluate your work. What works and what doesn’t? For help with evaluating and revising your work, check out this ProWritingAid post on manuscript revision .

After you’ve evaluated your draft, revise it. Repeat that process as many times as you need to make your work the best it can be.

When you’re satisfied with the content and structure of the essay, take it through the editing process .

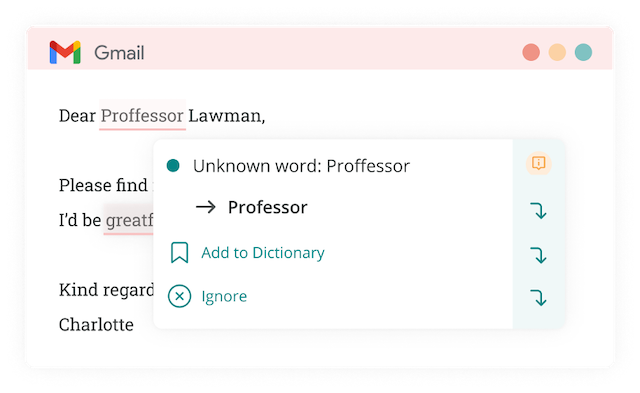

Grammatical or sentence-level errors can distract your audience or even detract from the ethos—the authority—of your work.

You don’t have to edit alone! ProWritingAid’s Realtime Report will find errors and make suggestions for improvements.

You can even use it on emails to your professors:

Try ProWritingAid with a free account.

How Can I Improve My Persuasion Skills?

You can develop your powers of persuasion every day just by observing what’s around you.

- How is that advertisement working to convince you to buy a product?

- How is a political candidate arguing for you to vote for them?

- How do you “argue” with friends about what to do over the weekend, or convince your boss to give you a raise?

- How are your parents working to convince you to follow a certain academic or career path?

As you observe these arguments in action, evaluate them. Why are they effective or why do they fail?

How could an argument be strengthened with more (or less) emphasis on ethos, logos, and pathos?

Every argument is an opportunity to learn! Observe them, evaluate them, and use them to perfect your own powers of persuasion.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Allison Bressmer is a professor of freshman composition and critical reading at a community college and a freelance writer. If she isn’t writing or teaching, you’ll likely find her reading a book or listening to a podcast while happily sipping a semi-sweet iced tea or happy-houring with friends. She lives in New York with her family. Connect at linkedin.com/in/allisonbressmer.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Rédaction persuasive : l’art de convaincre par les mots

- Auteur de l’article Par Anne Beckers

- Date de l’article 12 septembre 2023

Dans un monde fortement digitalisé où chaque mot compte, la rédaction persuasive est la clé pour captiver et guider des internautes toujours plus distraits. Pilier incontournable du copywriting et du marketing, elle les incite à effectuer des achats, à s’abonner, à soutenir des causes ou à changer leurs opinions. Dans cet article, je vous invite à explorer le vaste univers de la persuasion. Au programme :

Définition de la rédaction persuasive

La rédaction persuasive peut être définie comme l’art subtil d’utiliser les mots et les arguments de manière à influencer les opinions, les émotions, et les actions des lecteurs. Son objectif ultime est de guider les individus vers une décision spécifique, que ce soit l’achat d’un produit, l’abonnement à un service, le soutien à une cause, ou tout simplement un changement de point de vue.

Les domaines d’utilisation de l’écriture persuasive

Discrète, mais omniprésente, l’ écriture persuasive forge nos décisions quotidiennes. Elle nous incite à cliquer, regarder, lire, nous abonner, réagir, liker… Pour mieux comprendre son utilisation, découvrez des cas d’application de cette technique rédactionnelle.

Les publicités en ligne

Le marketing digital est le terrain de jeu idéal pour l’écriture persuasive. Des bannières aux pages de destination, en passant par les emails marketing, chaque mot est soigneusement sélectionné pour susciter l’intérêt immédiat du lecteur et stimuler l’action. Les biais cognitifs sont exploités, notamment pour créer une forme d’urgence ou de réciprocité dans le chef du lecteur. C’est ainsi que vous le poussez à agir « maintenant » ou à recevoir une offre gratuite en échange de ses coordonnées de contact.

Les articles de blog

Pourquoi lisez-vous un article de blog jusqu’à la dernière ligne ? C’est grâce à la rédaction persuasive qui capte votre attention dès les premiers mots et la maintient jusqu’à la fin. Pour atteindre ce résultat, les rédacteurs utilisent un arsenal rédactionnel composé de phrases succinctes, de termes simples et de paragraphes aérés. (Nous examinerons en détail les techniques de rédaction persuasive dans les paragraphes suivants.)

Les pages de vente

Sur un site web, les pages de vente jouent un rôle clé : celui de vous informer et de vous persuader d’acheter un produit ou un service. Cet objectif est atteint grâce à la rédaction persuasive qui combine des techniques rédactionnelles, l’appel aux émotions, les biais cognitifs et des arguments factuels. Les pages sont conçues pour susciter une réaction émotionnelle chez le prospect et créer un lien de confiance avec l’entreprise.

Les réseaux sociaux

Certaines publications sociales ont pour objectif de divertir ou d’informer. C’est le cas des posts de votre cousine Jacqueline ou de ceux des créateurs de contenu de votre niche.

Mais lorsque vous suivez le compte d’un influenceur, dont l’objectif est d’inciter à l’achat, le ton est différent. En effet, vous avez probablement remarqué un dénominateur commun aux publications des influenceurs : l’enthousiasme (exacerbé). (Un peu neuneu, pourrait-on dire.)

Ils partagent leurs histoires et détaillent leurs expériences avec un enthousiasme débordant et contagieux pour pousser leurs abonnés à l’achat ou au soutien d’une cause. Et ça marche ! Cette positive attitude digne du monde de Barbie renforce votre niveau de dopamine et votre envie de chasser le produit parfait (sur Insta).

La communication d’entreprise

Lorsque vous communiquez avec des clients, des investisseurs ou des partenaires commerciaux, l’écriture persuasive est également un atout. Grâce à elle, vos demandes de financement et vos propositions commerciales inspirent confiance, suscitent l’engagement et convainquent.

Les plaidoyers et actions de sensibilisation

Les organisations à but non lucratif et les militants s’appuient également sur l’écriture persuasive pour mobiliser l’attention du public envers des problématiques cruciales. Une simple pétition en ligne peut éveiller des émotions fortes et inciter la société à l’action. Les marches pour le climat ayant eu lieu en France en 2018 font suite à de multiples actions « rédactionnelles » : des pétitions avec plusieurs milliers de signatures, des tribunes dans les médias et, bien entendu, le rapport du GIEC d’octobre 2018.

Les lettres de motivation et le CV

Les demandeurs d’emploi peuvent exploiter l’écriture persuasive dans leur CV et leurs lettres de motivation pour démontrer aux employeurs pourquoi leur profil est idéal pour le poste à pourvoir. Grâce à cette technique rédactionnelle, ils valorisent leur expérience et leurs compétences, et transmettent efficacement leur passion et leur enthousiasme pour le métier.

Les campagnes politiques

La rédaction persuasive est un outil de mobilisation puissant lors des campagnes politiques. Les politiciens s’en servent pour persuader les électeurs de leur accorder leur vote. Leurs discours et leurs tracts sont parsemés de messages émotionnels, enthousiastes, passionnés et puissants destinés à influencer l’opinion publique en leur faveur.

Les techniques de rédaction persuasive

Vous avez désormais une meilleure compréhension des nombreuses utilisations de l’écriture persuasive. Il est temps de plonger dans les techniques les plus courantes qui vous permettront de maîtriser rapidement cet art.

Connaître le public cible pour assurer la pertinence du message

La première étape pour écrire de manière persuasive est de bien connaître votre audience. Vous devez comprendre ses besoins, ses désirs, ses préoccupations et ses valeurs. Créez des personas pour représenter différents segments de votre audience. Mieux vous connaissez votre public, plus vous pouvez adapter votre message pour le rendre pertinent et convaincant pour lui.

Conseil : effectuez des recherches approfondies sur l’audience, réalisez des enquêtes, des analyses et même des interviews lorsque cela est possible. Adaptez votre ton, votre style et vos arguments en fonction de ses caractéristiques.

Choisir la tonalité adaptée au destinataire

Votre voix de marque est unique. Elle représente vos valeurs, votre positionnement singulier sur votre marché et plus généralement, votre personnalité. Le ton que vous utilisez doit toutefois être adapté au public cible et au contexte. Par exemple, vous pouvez employer un ton amical pour engager le grand public et adopter un ton professionnel pour vous adresser à une audience plus experte. L’essentiel est de connaître le public ciblé et de créer une connexion émotionnelle en utilisant un ton qui résonne avec lui.

Conseil : adaptez votre ton en fonction du contexte. Par exemple, une lettre de vente peut avoir un ton plus persuasif et enthousiaste, tandis qu’un rapport professionnel peut nécessiter un ton plus formel.

Être direct grâce à la clarté et la concision du message

La clarté et la concision sont essentielles en écriture persuasive. Vous devez rédiger un texte facile à lire, même s’il s’adresse à des experts. Évitez les phrases longues et complexes qui risquent de perdre votre lecteur. Utilisez des phrases courtes et des mots simples pour rendre votre message immédiatement compréhensible. Soyez direct dans votre communication.

Conseil : lors de la révision, identifiez les phrases ou les mots inutiles et supprimez-les. Assurez-vous que votre message est fluide et compréhensible dès la première lecture.

Assurer sa crédibilité avec des arguments solides

L’un des fondements de l’écriture persuasive réside dans la présentation d’arguments solides pour étayer votre point de vue. Les opinions seules ne suffisent pas pour convaincre une audience, il faut un équilibre. Vous devriez donc aussi vous appuyer sur des faits, des statistiques, des études de cas et des exemples concrets pour renforcer la crédibilité de votre message. En effet, plus vos arguments sont étayés, plus leur puissance persuasive est forte.

Conseil : pour ce faire, menez des recherches approfondies afin de collecter des preuves solides qui soutiennent votre position. Organisez vos arguments de manière logique pour construire une argumentation convaincante.

Capturer l’attention de l’internaute avec une introduction inoubliable

Le début de votre texte est d’une importance cruciale pour captiver vos lecteurs. Utilisez des mots percutants, des anecdotes engageantes, des questions provocatrices ou des statistiques surprenantes pour éveiller leur intérêt. Une fois que vous avez réussi à capter leur attention, ils seront bien plus enclins à poursuivre leur lecture.

Conseil : allouez du temps à la création d’une introduction qui se démarque et qui suscite l’intérêt de vos lecteurs. Évitez les débuts monotones ou prévisibles, privilégiez plutôt une entrée en matière qui intrigue et attire l’attention.

Utiliser des mots puissants et des verbes d’action pour susciter l’émotion

En écriture persuasive, le choix des mots joue un rôle déterminant. Il est impératif d’opter pour des termes puissants et évocateurs, capables de déclencher des émotions intenses et de créer des images vives dans l’esprit des lecteurs. Parmi vos meilleurs alliés se trouvent les verbes d’action, car ils incitent littéralement à passer à l’action.

Conseil : pour enrichir votre répertoire, n’hésitez pas à recourir à un dictionnaire des synonymes. Passez ensuite en revue votre texte à la recherche des termes plats pour les remplacer par des mots puissants.

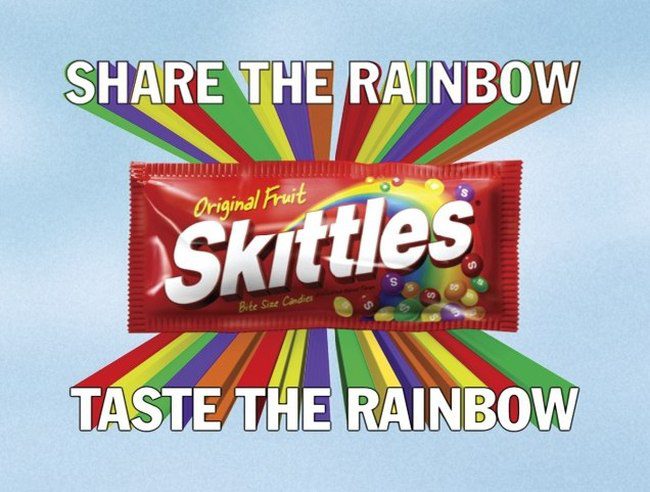

Exploiter la répétition pour renforcer le message

La répétition est une technique persuasive hautement efficace. Elle consiste à réitérer vos arguments principaux ou vos messages clés à plusieurs reprises tout au long de votre texte. Cette approche présente deux avantages essentiels : elle renforce la mémorisation chez les lecteurs et elle les incite davantage à passer à l’action.

Toutefois, il convient d’opérer avec discernement. Trop de répétition, et le message perd en persuasion. Pas assez de répétitions, et le message manque de conviction. Le chiffre trois est le point magique : répéter 3 fois le message clé augmente les réflexions positives et l’approbation de ce message, tout en réduisant les contre-arguments ( Richard Petty et John Cacioppo ).

Conseil : identifiez clairement vos messages clés et veillez à les répéter de manière subtile tout au long de votre texte. Variez les formulations pour éviter toute monotonie et maintenir l’engagement de votre audience.

Structurer le texte pour en faciliter la lecture

La manière dont vous structurez votre texte revêt une importance capitale dans le processus de persuasion. L’intégration de titres et de sous-titres contribue à l’organisation claire et hiérarchisée de votre contenu. Ces éléments servent de repères visuels, mais aussi de guides pour le lecteur tout au long de votre argumentation.

Conseil : avant de commencer à rédiger, planifiez la structure de votre texte en utilisant des titres et des sous-titres descriptifs qui donnent un aperçu clair du contenu de chaque section. Cette approche vous aidera à créer un texte fluide et facile à suivre.

Employer des mots de liaison pour assurer la cohérence du texte

L’emploi de mots de liaison et de connecteurs logiques se révèle essentiel pour créer une lecture fluide et cohérente. Ces mots jouent le rôle de maillons entre les paragraphes. Ils tissent des liens entre les idées, simplifient la compréhension du contenu et maintiennent l’attention du lecteur tout au long de son parcours. Ils assurent ainsi une navigation aisée à travers votre texte.

Conseil : pour garantir une cohérence optimale, intégrez des mots de liaison et des connecteurs logiques tels que « cependant », « toutefois », « en plus », « par conséquent » ou « en résumé » pour guider le lecteur tout au long de votre argumentation.

Fuir les négations

Pour renforcer le pouvoir persuasif d’un écrit, il est judicieux d’ éviter l’utilisation de la négation . En effet, les tournures de phrases négatives se lisent plus difficilement et cassent la fluidité du texte, ce qui peut affaiblir votre message.

Comprendre le public grâce à l’empathie

Pour convaincre une personne, il est important de faire preuve d’empathie à son égard. En vous mettant à la place de votre public, en comprenant ses besoins et ses attentes, vous êtes en mesure d’utiliser cette compréhension pour élaborer un message à la fois humain et authentique. Cela crée une connexion émotionnelle avec votre audience, renforçant ainsi l’impact de votre message persuasif.

Aller droit au but

Finalement, il est impératif de préciser l’action attendue des lecteurs avec la plus grande clarté. Que ce soit l’achat d’un bien, la signature d’une pétition ou une prise de contact avec votre entreprise, vous devez indiquer vos attentes de manière limpide.

Conseil : recourez à des appels à l’action (CTA) clairs. Ces instructions directes aident vos lecteurs à comprendre précisément ce que vous attendez d’eux, tout en rendant leur action plus aisée. La rédaction persuasive se perfectionne par la pratique. En utilisant ces techniques et en les adaptant à vos besoins spécifiques, vous améliorez progressivement cette compétence indispensable à de nombreuses professions. Que vous souhaitiez lever des fonds pour une œuvre de charité, améliorer les ventes d’un produit ou trouver votre prochain emploi, l’écriture persuasive est votre alliée.

Partager cet article :

- Cliquez pour partager sur Facebook(ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

- Cliquez pour partager sur LinkedIn(ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

- Cliquez pour partager sur Twitter(ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

- Cliquez pour partager sur WhatsApp(ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

- Cliquer pour envoyer un lien par e-mail à un ami(ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

- Cliquer pour imprimer(ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

- EXPLORER À propos de wikiHow Tableau de bord communautaire Au hasard Catégories

Connectez-vous

- Parcourez les catégories

- En savoir plus au sujet de wikiHow

- Connexion/Inscription

- Communication et Éducation

Comment écrire un essai persuasif

wikiHow est un wiki, ce qui veut dire que de nombreux articles sont rédigés par plusieurs auteurs(es). Pour créer cet article, 126 personnes, certaines anonymes, ont participé à son édition et à son amélioration au fil du temps. Il y a 14 références citées dans cet article, elles se trouvent au bas de la page. Cet article a été consulté 69 043 fois.

Une dissertation persuasive est un texte qui sert à convaincre le lecteur à propos d'une idée ou d'un point de vue. Une telle dissertation pourrait concerner un thème sur lequel vous avez une opinion bien arrêtée. Une dissertation persuasive et très différente d'un texte argumentatif , car ce dernier est davantage fondé sur la preuve, tandis qu'une dissertation persuasive peut mettre à contribution les opinions ou la sensibilité du lecteur [1] X Source de recherche . Il est préférable de rédiger un texte persuasif pour présenter une argumentation contre la malbouffe à l'école ou pour demander une augmentation de salaire.

Préparer le terrain

- Recherchez des indices pour savoir si vous allez rédiger un texte purement persuasif ou un texte argumentatif. Par exemple, si dans le sujet vous rencontrez des expressions comme « expérience personnelle » ou « observations personnelles », vous pourrez appuyer votre argumentation en utilisant vos propres observations ou votre expérience. [2] X Source de recherche

- Des mots comme « défendre » ou « prétendre » suggèrent qu'il faudrait écrire un texte argumentatif en s'appuyant sur des preuves objectives plus formelles.

- Si vous avez un doute sur le genre de texte à produire, demandez des précisions à votre enseignant.

- Commencez de bonne heure, chaque fois que cela est possible. De cette manière, même si vous rencontrez une situation d'urgence comme une panne d'ordinateur, vous aurez suffisamment de temps pour terminer votre dissertation.

- Le texte doit être clair et bien étayé par des preuves et des avis, s'il y a lieu.

- En tant qu'auteur, vous avez besoin de conserver votre crédibilité en effectuant les recherches nécessaires, en exprimant clairement votre point de vue et en fournissant des arguments valables qui ne déforment pas les faits ou les situations.

- N'oubliez pas que l'objectif de votre travail est de convaincre vos lecteurs d'adopter votre point de vue. [4] X Source de recherche

- Le contexte peut varier. Dans de nombreux cas, vous ferez un devoir de classe qui sera noté.

- Comme les essais argumentatifs, les textes persuasifs emploient des figures de rhétorique pour convaincre les lecteurs. Dans ces textes, il est généralement admis de faire appel à la sensibilité (le pathos), aux faits, à la logique (logos) et à la crédibilité (l'éthos). [5] X Source fiable Read Write Think Aller sur la page de la source

- Pendant la rédaction d'une dissertation persuasive, vous devrez présenter soigneusement des preuves de plusieurs types. Les éléments logiques tels que la présentation de données, de faits et d'autres preuves tangibles sont souvent très utiles pour convaincre les lecteurs.

- Les dissertations persuasives ont généralement des énoncés de thèse très clairs, qui montrent d'avance de quel bord vous êtes. Ceci permet à votre lecteur de savoir exactement l'opinion que vous allez défendre. [6] X Source de recherche

- Par exemple, si vous rédigez un texte contre les déjeuners scolaires malsains, vous choisirez des arguments qui tiennent compte du lectorat à convaincre. Si vous ciblez les administrateurs des écoles, vous pouvez insister sur les liens entre les aliments sains et les bonnes notes en classe. Si vous vous adressez aux parents d'élèves, vous pouvez orienter votre texte vers la santé des enfants et les couts éventuels des soins de santé pour soigner les affections causées par les aliments malsains. Et s'il s'agit de sensibiliser vos camarades, vous feriez probablement appel à vos préférences personnelles.

- Choisissez un thème qui vous passionne. L'impact d'une dissertation persuasive dépend souvent de l'aspect émotionnel. C'est pourquoi il est préférable d'écrire sur un thème à propos duquel vous avez une opinion bien arrêtée. Donc, choisissez une question que vous maitrisez parfaitement et que vous pouvez défendre avec conviction.

- Recherchez un thème profond ou complexe. La pizza peut être l'une de vos passions, mais il est probablement difficile d'écrire une dissertation captivante sur ce sujet. Par contre, vous pourrez rédiger un article intéressant sur un autre sujet qui a une certaine portée, comme la cruauté envers les animaux ou le budget du gouvernement.

- En réfléchissant sur votre dissertation, commencez par examiner des points de vue opposés aux vôtres. Si vous avez des difficultés à trouver des arguments contraires, vous n'aurez probablement pas suffisamment de matière pour produire un texte convaincant. D'autre part, s'il y a trop d'arguments solides contre votre thèse, pensez à en choisir une qui est moins facile à réfuter.

- Veillez à garder un certain équilibre. Dans une dissertation persuasive, vous examinerez les arguments contraires pour convaincre le lecteur d'adopter l'avis que vous défendez. Assurez-vous de choisir un sujet que vous pourrez approfondir. Vous devrez aussi examiner honnêtement l'argumentation contraire. Pour cette raison, il est préférable de ne pas écrire un texte persuasif sur des thèmes tels que la religion, car vous aurez peu de chances de convaincre quelqu'un de changer de religion.

- Délimitez l'étendue de votre sujet. La longueur de votre dissertation est variable. Elle peut s'étendre sur cinq paragraphes ou plusieurs pages, mais, dans les deux cas, vous devez délimiter votre sujet pour pouvoir l'explorer convenablement. Par exemple, si vous tentez de persuader vos lecteurs que la guerre est mauvaise, vous aurez peu de chances de réussir, parce que ce sujet est très vaste. Toutefois, si vous limitez la portée de votre sujet aux frappes de drones dévastatrices, vous serez plus à l'aise pour approfondir vos arguments. [7] X Source de recherche

- Votre énoncé de thèse doit également esquisser la structure de votre dissertation. Évitez de dresser la liste de vos points dans un certain ordre et d'en discuter dans un ordre différent.

- Par exemple, un énoncé de thèse pourrait ressembler à ceci : « Les aliments traités et prêts à la consommation ne sont pas bons pour les étudiants, même si ces aliments coutent moins cher. Il est important que les écoles offrent des repas frais et sains à leurs élèves, malgré le prix plus élevé de ces repas. Des repas sains pris à la cantine d'une école peuvent créer une énorme différence dans la vie des élèves, car le fait de ne pas consommer de tels repas entraine souvent un échec scolaire. »

- Notez que cet énoncé de thèse ne s'appuie pas sur une triple approche. Vous n'avez pas besoin de mentionner chaque point que vous présenterez dans votre thèse, sauf si votre devoir le stipule, mais vous aurez certainement besoin d'indiquer exactement votre point de vue.

- Une carte mentale pourrait vous être utile. Commencez par écrire votre thème central, puis entourez-le. Ensuite, inscrivez vos autres idées dans des petites bulles autour du thème en question. Reliez les bulles pour déceler les tendances et identifier les liens entre les idées. [10] X Source de recherche

- À ce stade, n'essayez pas de formuler complètement vos idées, car le plus important est d'abord d'en trouver.

- Par exemple, si vous défendez la consommation d'une nourriture plus saine à l'école, vous pourrez démontrer que les aliments frais et naturels ont un gout meilleur. Il s'agit d'un avis personnel qui ne nécessite pas de rechercher des arguments pour l'appuyer. Toutefois, si vous voulez soutenir que, par rapport aux aliments transformés, la nourriture fraiche contient plus de vitamines et de nutriments, vous aurez besoin de citer une source fiable à l'appui de votre allégation.

- Si vous pouvez, demandez conseil à votre bibliothécaire ! Les bibliothécaires sont bien qualifiés pour vous guider vers une recherche crédible.

Rédiger l'essai

- Une introduction. Elle sert à accrocher l'attention de votre lectorat. Vous devez y incorporer l'énoncé de votre thèse, c'est-à-dire une déclaration claire concernant la proposition que vous allez défendre pour convaincre le lecteur d'y adhérer.

- Le corps du sujet. Dans un essai à cinq paragraphes, le corps du sujet en contient trois. Dans d'autres essais, vous pouvez avoir autant de paragraphes qu'il faut pour démontrer votre thèse. Indépendamment du nombre de paragraphes du corps du texte, chacun d'eux doit traiter une seule idée principale et l'appuyer par des justificatifs. Ces paragraphes servent aussi à réfuter tous les arguments contraires que vous avez découverts.

- Une conclusion. Votre conclusion est l'endroit où vous emballez le tout. Elle peut faire appel à la sensibilité du lecteur, réitérer l'argument le plus convaincant ou rattacher votre thèse à un contexte plus large. Étant donné que vous cherchez à persuader vos lecteurs à faire quelque chose ou à penser d'une certaine façon, concluez votre texte par un appel à l'action.

- Par exemple, vous pouvez commencer un essai sur la nécessité de rechercher des sources alternatives d'énergie par cette phrase « imaginez un monde dépourvu d'ours polaires ». C'est une déclaration brillante qui présente avec brio un animal que la majorité des lecteurs connaissent et aiment, à savoir l'ours polaire. Ainsi, vous encouragez également le lecteur à continuer sa lecture pour apprendre la raison d'imaginer un tel monde.

- Il se peut que vous n'ayez pas d'accroche. Ne vous arrêtez pas pour autant ! Vous pourrez toujours remettre cette question à plus tard et y revenir une fois que vous avez terminé la rédaction de votre dissertation.

- Placez votre accroche au début de l'introduction. Puis, passez des idées générales vers des idées précises jusqu'à construire votre énoncé de thèse.

- Ne lésinez pas en rédigeant votre énoncé de thèse , car il résume le sujet que vous allez traiter. Habituellement, il s'agit d'une phrase que vous placez vers la fin du paragraphe d'introduction. Par souci d'efficacité, reflétez dans votre énoncé vos arguments les plus convaincants ou l'argument le plus puissant.

- Commencez par rédiger une phrase claire pour exprimer l'idée principale du paragraphe.

- Présentez des preuves claires et précises. Par exemple, ne vous contentez pas d'écrire : « Les dauphins sont des animaux très intelligents. Pratiquement tout le monde est d'accord là-dessus. » Écrivez plutôt : « Les dauphins sont des animaux très intelligents. Plusieurs études ont révélé que ces cétacés ont travaillé en tandem avec les humains pour attraper une proie. Très peu d'espèces animales ont collaboré de cette manière avec les humains. »

- « Le sud du pays, qui détient 80 % de toutes les peines de mort aux États-Unis, a encore le plus haut taux d'homicide volontaire. Ces chiffres infirment la validité de la peine de mort en tant que moyen de dissuasion. »

- « En outre, Les États qui n'appliquent pas la peine de mort enregistrent moins d'homicides. Si la peine de mort est un moyen de dissuasion efficace, pourquoi le taux d'homicide volontaire des États qui n'appliquent pas cette peine n'augmente-t-il pas ? »

- Examinez l'enchainement des paragraphes du corps du sujet. Assurez-vous de montrer la progression de votre argumentation tout le long de votre texte et évitez surtout de disperser vos preuves.

- Fin du premier paragraphe : « Si la peine de mort n'a pas réussi à dissuader les malfaiteurs et que la criminalité a atteint un niveau inégalé, qu'arrive-t-il quand un individu est condamné à tort ? »

- Début du deuxième paragraphe : « Parmi les condamnés à mort, plus de cent détenus condamnés à tort ont été acquittés, certains in extrémis, quelques instants avant l'exécution de la sentence. »

- Voici un exemple : « Les adversaires d'un règlement, qui permet aux élèves d'amener des collations en classe, prétendent qu'une telle pratique perturbe les élèves et diminue leur désir d'apprendre. Cependant, il faut savoir que les lycéens ont un taux de croissance physique incroyable. Leur corps a besoin d'énergie et ils peuvent se fatiguer rapidement, s'ils passent de longues périodes sans nourriture. Autoriser les collations en classe va effectivement augmenter la capacité des élèves à se concentrer en éliminant la distraction causée par la faim. » [15] X Source de recherche

- Vous pouvez même trouver plus efficace de commencer votre paragraphe avec l'argument contraire, puis présenter votre réfutation et votre propre argument. [16] X Source de recherche

- Est-il possible d'appliquer ma thèse dans un contexte plus large ?

- Pourquoi ma thèse ou mon opinion aura-t-elle une signification pour le lecteur ?

- Quelles sont les questions connexes soulevées par ma thèse ?

- Quelle est l'action que le lecteur pourrait entreprendre après la lecture de ma dissertation ?

Parfaire la dissertation

- 1 Attendez une journée ou deux avant de relire votre dissertation. Prenez vos dispositions à l'avance, ensuite revenez à votre travail après un jour ou deux et relisez-le. Après cette période de repos, vous aurez un regard neuf qui vous aidera à repérer vos erreurs. Vous examinerez à ce moment-là les questions et les idées compliquées, qui avaient besoin de temps pour être réglées.

- Avez-vous exprimé clairement votre position dans votre texte ?

- Avez-vous appuyé votre argumentation par des preuves et des exemples appropriés ?

- Avez-vous inclus des informations superflues qui affaiblissent vos paragraphes ? Avez-vous traité une seule idée principale par paragraphe ?

- Avez-vous présenté honnêtement et sans déformation les arguments contraires à votre thèse ? Les avez-vous réfutés d'une manière convaincante ?

- Est-ce que l'enchainement de vos paragraphes est logique ? Est-ce que votre argumentation est progressive ?

- Est-ce que la conclusion reflète l'importance de votre point de vue ? Invite-t-elle le lecteur à agir ou à penser d'une certaine manière ?

- Il sera peut-être utile de demander à un ami de confiance ou à un camarade de classe d'examiner votre dissertation. S'il vous signale une faiblesse dans votre argumentation ou s'il trouve des points obscurs, tenez-en compte pendant votre révision.

- Vous trouverez peut-être utile d'imprimer votre texte et de l'annoter avec un crayon ou un stylo. Lorsque vous écrivez sur l'ordinateur, vos yeux peuvent ne pas voir les erreurs, car vous aurez tendance à ne pas lire ce que vous avez écrit réellement, mais ce que vous pensez avoir écrit. Lorsque vous travaillez sur une copie matérielle, vous serez obligé à faire attention autrement.

- Veillez également à mettre en forme votre dissertation correctement. Par exemple, de nombreux enseignants exigent de laisser une marge d'une certaine largeur et d'employer un certain type de police de caractères.

- Résistez à l'envie d'employer des mots ronflants pour avoir l'air d'un érudit . Utilisez plutôt un vocabulaire précis et clair.

- Lisez d'autres textes persuasifs pour avoir une idée sur le vocabulaire employé.

- Veillez à présenter le côté positif de vos arguments sans changer votre point de vue ou vous contredire.

- N'oubliez pas que vous êtes en train de rédiger un texte persuasif. Vous êtes censé convaincre le lecteur de faire quelque chose, et non de lui présenter vos doléances.

- Donnez de l'importance à chacune de vos phrases. L'ajout de phrases supplémentaires ne vous aidera pas à faire comprendre votre point de vue. Gardez votre texte clair et concis.

- N'utilisez pas des pronoms personnels tels que je ou vous . Ainsi, vous éviterez de donner à votre texte une touche personnelle.

- N'oubliez pas d'analyser les arguments contraires éventuels qui pourraient réfuter ce que vous essayez de démontrer. Vous avez besoin de vous organiser à l'avance pour faire face aux contradictions. Par conséquent, dressez la liste des plus importantes d'entre elles et trouvez les ripostes appropriées.

wikiHows en relation

- ↑ http://www.berkeley.k12.sc.us/webpages/alishaanderson/index.cfm?subpage=98668

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/engagement/2/2/52/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/625/02/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/625/01/

- ↑ http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson56/strategy-definition.pdf

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/writing/writing-resources/persuasive-essays

- ↑ http://www.facstaff.bucknell.edu/awolaver/term1.htm

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/engagement/2/2/53/

- ↑ http://www.time4writing.com/writing-resources/writing-resourcespersuasive-essay/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/685/05/

- ↑ http://www.oradell.k12.nj.us/osnj/STAFF/Faculty and Staff/Mrs. Helene Albrecht/Past Homework/December Homework/Persuasive:Counteragrument Example.pdf

- ↑ http://www.cambridge.org/other_files/downloads/esl/waw/089-110_WritersAtWork_CH04.pdf

À propos de ce wikiHow

Cet article vous a-t-il été utile , articles en relation.

Abonnez-vous à la newsletter gratuite de wikiHow !

Des tutoriels utiles dans votre boitier de réception chaque semaine.

Articles tendance

Vidéos tendance

- À propos de wikiHow

- Contactez nous

- Plan du site

- Termes et conditions

- Politique de confidentialité

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Suivez-nous

Abonnez-vous pour recevoir la

newsletter de wikiHow!

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.7: Tips for Writing Academic Persuasive Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 250473

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The previous chapters in this section offer an overview of what it means to formulate an argument in an academic situation. The purpose of this chapter is to offer more concrete, actionable tips for drafting an academic persuasive essay. Keep in mind that preparing to draft a persuasive essay relies on the strategies for any other thesis-driven essay, covered by the section in this textbook, The Writing Process. The following chapters can be read in concert with this one:

- Critical Reading and other research strategies helps writers identify the exigence (issue) that demands a response, as well as what kinds of research to use.

- Generate Ideas covers prewriting models (such as brainstorming techniques) that allow students to make interesting connections and develop comprehensive thesis statements. These connections and main points will allow a writer to outline their core argument.

- Organizing is important for understanding why an argument essay needs a detailed plan, before the drafting stage. For an argument essay, start with a basic outline that identifies the claim, reasoning, and evidence, but be prepared to develop more detailed outlines that include counterarguments and rebuttals, warrants, additional backing, etc., as needed.

- Drafting introduces students to basic compositional strategies that they must be familiar with before beginning an argument essay. This current chapter offers more details about what kinds of paragraphs to practice in an argument essay, but it assumes the writer is familiar with basic strategies such as coherence and cohesion.

Classical structure of an argument essay

Academic persuasive essays tend to follow what’s known as the “classical” structure, based on techniques that derive from ancient Roman and Medieval rhetoricians. John D. Ramage, et. al outline this structure in Writing Arguments :

This very detailed table can be simplified. Most academic persuasive essays include the following basic elements:

- Introduction that explains why the situation is important and presents your argument (aka the claim or thesis).

- Reasons the thesis is correct or at least reasonable.

- Evidence that supports each reason, often occurring right after the reason the evidence supports.

- Acknowledgement of objections.

- Response to objections.

Keep in mind that the structure above is just a conventional starting point. The previous chapters of this section suggest how different kinds of arguments (Classical/Aristotelian, Toulmin, Rogerian) involve slightly different approaches, and your course, instructor, and specific assignment prompt may include its own specific instructions on how to complete the assignment. There are many different variations. At the same time, however, most academic argumentative/persuasive essays expect you to practice the techniques mentioned below. These tips overlap with the elements of argumentation, covered in that chapter, but they offer more explicit examples for how they might look in paragraph form, beginning with the introduction to your essay.

Persuasive introductions should move from context to thesis

Since one of the main goals of a persuasive essay introduction is to forecast the broader argument, it’s important to keep in mind that the legibility of the argument depends on the ability of the writer to provide sufficient information to the reader. If a basic high school essay moves from general topic to specific argument (the funnel technique), a more sophisticated academic persuasive essay is more likely to move from context to thesis.

The great stylist of clear writing, Joseph W. Williams, suggests that one of the key rhetorical moves a writer can make in a persuasive introduction is to not only provide enough background information (the context), but to frame that information in terms of a problem or issue, what the section on Reading and Writing Rhetorically terms the exigence . The ability to present a clearly defined problem and then the thesis as a solution creates a motivating introduction. The reader is more likely to be gripped by it, because we naturally want to see problems solved.

Consider these two persuasive introductions, both of which end with an argumentative thesis statement:

A. In America we often hold to the belief that our country is steadily progressing. topic This is a place where dreams come true. With enough hard work, we tell ourselves (and our children), we can do anything. I argue that, when progress is more carefully defined, our current period is actually one of decline. claim

B . Two years ago my dad developed Type 2 diabetes, and the doctors explained to him that it was due in large part to his heavy consumption of sugar. For him, the primary form of sugar consumption was soda. hook His experience is echoed by millions of Americans today. According to the most recent research, “Sugary drink portion sizes have risen dramatically over the past forty years, and children and adults are drinking more soft drinks than ever,” while two out of three adults in the United States are now considered either overweight or obese. This statistic correlates with reduced life expectancy by many years. Studies have shown that those who are overweight in this generation will live a lot fewer years than those who are already elderly. And those consumers who don’t become overweight remain at risk for developing Type 2 diabetes (like my dad), known as one of the most serious global health concerns (“Sugary Drinks and Obesity Fact Sheet”). problem In response to this problem, some political journalists, such as Alexandra Le Tellier, argue that sodas should be banned. On the opposite end of the political spectrum, politically conservative journalists such as Ernest Istook argue that absolutely nothing should be done because that would interfere with consumer freedom. debate I suggest something in between: a “soda tax,” which would balance concerns over the public welfare with concerns over consumer freedom. claim

Example B feels richer, more dramatic, and much more targeted not only because it’s longer, but because it’s structured in a “motivating” way. Here’s an outline of that structure:

- Hook: It opens with a brief hook that illustrates an emerging issue. This concrete, personal anecdote grips the reader’s attention.

- Problem: The anecdote is connected with the emerging issue, phrased as a problem that needs to be addressed.

- Debate: The writer briefly alludes to a debate over how to respond to the problem.

- Claim: The introduction ends by hinting at how the writer intends to address the problem, and it’s phrased conversationally, as part of an ongoing dialogue.

Not every persuasive introduction needs all of these elements. Not all introductions will have an obvious problem. Sometimes a “problem,” or the exigence, will be as subtle as an ambiguity in a text that needs to be cleared up (as in literary analysis essays). Other times it will indeed be an obvious problem, such as in a problem-solution argument essay.

In most cases, however, a clear introduction will proceed from context to thesis . The most attention-grabbing and motivating introductions will also include things like hooks and problem-oriented issues.

Here’s a very simple and streamlined template that can serve as rudimentary scaffolding for a persuasive introduction, inspired by the excellent book, They Say / I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing : Definition: Term

In discussions of __________, an emerging issue is _____________________. issue When addressing this issue, some experts suggest ________________. debate In my view, however, _______________________________. claim

Each aspect of the template will need to be developed, but it can serve as training wheels for how to craft a nicely structured context-to-thesis introduction, including things like an issue, debate, and claim. You can try filling in the blanks below, and then export your attempt as a document.

Define key terms, as needed

Much of an academic persuasive essay is dedicated to supporting the claim. A traditional thesis-driven essay has an introduction, body, and conclusion, and the support constitutes much of the body. In a persuasive essay, most of the support is dedicated to reasoning and evidence (more on that below). However, depending on what your claim does, a careful writer may dedicate the beginning (or other parts of the essay body) to defining key terms.

Suppose I wish to construct an argument that enters the debate over euthanasia. When researching the issue, I notice that much of the debate circles around the notion of rights, specifically what a “legal right” actually means. Clearly defining that term will help reduce some of the confusion and clarify my own argument. In Vancouver Island University’s resource “ Defining key terms ,” Ian Johnston offers this example for how to define “legal right” for an academic reader:

Before discussing the notion of a right to die, we need to clarify precisely what the term legal right means. In common language, the term “right” tends often to mean something good, something people ought to have (e.g., a right to a good home, a right to a meaningful job, and so on). In law, however, the term has a much more specific meaning. It refers to something to which people are legally entitled. Thus, a “legal” right also confers a legal obligation on someone or some institution to make sure the right is conferred. For instance, in Canada, children of a certain age have a right to a free public education. This right confers on society the obligation to provide that education, and society cannot refuse without breaking the law. Hence, when we use the term right to die in a legal sense, we are describing something to which a citizen is legally entitled, and we are insisting that someone in society has an obligation to provide the services which will confer that right on anyone who wants it.

As the example above shows, academics often dedicate space to providing nuanced and technical definitions that correct common misconceptions. Johnston’s definition relies on research, but it’s not always necessary to use research to define your terms. Here are some tips for crafting definitions in persuasive essays, from “Defining key terms”:

- Fit the descriptive detail in the definition to the knowledge of the intended audience. The definition of, say, AIDS for a general readership will be different from the definition for a group of doctors (the latter will be much more technical). It often helps to distinguish between common sense or popular definitions and more technical ones.

- Make sure definitions are full and complete; do not rush them unduly. And do not assume that just because the term is quite common that everyone knows just what it means (e.g., alcoholism ). If you are using the term in a very specific sense, then let the reader know what that is. The amount of detail you include in a definition should cover what is essential for the reader to know, in order to follow the argument. By the same token, do not overload the definition, providing too much detail or using far too technical a language for those who will be reading the essay.

- It’s unhelpful to simply quote the google or dictionary.com definition of a word. Dictionaries contain a few or several definitions for important terms, and the correct definition is informed by the context in which it’s being employed. It’s up to the writer to explain that context and how the word is usually understood within it.

- You do not always need to research a definition. Depending on the writing situation and audience, you may be able to develop your own understanding of certain terms.

Use P-E-A-S or M-E-A-L to support your claim

The heart of a persuasive essay is a claim supported by reasoning and evidence. Thus, much of the essay body is often devoted to the supporting reasons, which in turn are proved by evidence. One of the formulas commonly taught in K-12 and even college writing programs is known as PEAS, which overlaps strongly with the MEAL formula introduced by the chapter, “ Basic Integration “:

Point : State the reasoning as a single point: “One reason why a soda tax would be effective is that…” or “One way an individual can control their happiness is by…”

Evidence : After stating the supporting reason, prove that reason with related evidence. There can be more than one piece of evidence. “According to …” or “In the article, ‘…,’ the author shows that …”

Analysis : There a different levels of analysis. At the most basic level, a writer should clearly explain how the evidence proves the point, in their own words: “In other words…,” “What this data shows is that…” Sometimes the “A” part of PEAS becomes simple paraphrasing. Higher-level analysis will use more sophisticated techniques such as Toulmin’s warrants to explore deeper terrain. For more tips on how to discuss and analyze, refer to the previous chapter’s section, “ Analyze and discuss the evidence .”

Summary/So what? : Tie together all of the components (PEA) succinctly, before transitioning to the next idea. If necessary, remind the reader how the evidence and reasoning relates to the broader claim (the thesis argument).

PEAS and MEAL are very similar; in fact they are identical except for how they refer to the first and last part. In theory, it shouldn’t matter which acronym you choose. Both versions are effective because they translate the basic structure of a supporting reason (reasoning and evidence) into paragraph form.

Here’s an example of a PEAS paragraph in an academic persuasive essay that argues for a soda tax:

A soda tax would also provide more revenue for the federal government, thereby reducing its debt. point Despite Ernest Istook’s concerns about eroding American freedom, the United States has long supported the ability of government to leverage taxes in order to both curb unhealthy lifestyles and add revenue. According to Peter Ubel’s “Would the Founding Fathers Approve of a Sugar Tax?”, in 1791 the US government was heavily in debt and needed stable revenue. In response, the federal government taxed what most people viewed as a “sin” at that time: alcohol. This single tax increased government revenue by at least 20% on average, and in some years more than 40% . The effect was that only the people who really wanted alcohol purchased it, and those who could no longer afford it were getting rid of what they already viewed as a bad habit (Ubel). evidence Just as alcohol (and later, cigarettes) was viewed as a superfluous “sin” in the Early Republic, so today do many health experts and an increasing amount of Americans view sugar as extremely unhealthy, even addictive. If our society accepts taxes on other consumer sins as a way to improve government revenue, a tax on sugar is entirely consistent. analysis We could apply this to the soda tax and try to do something like this to help knock out two problems at once: help people lose their addiction towards soda and help reduce our government’s debt. summary/so what?

The paragraph above was written by a student who was taught the PEAS formula. However, we can see versions of this formula in professional writing. Here’s a more sophisticated example of PEAS, this time from a non-academic article. In Nicholas Carr’s extremely popular article, “ Is Google Making Us Stupid? “, he argues that Google is altering how we think. To prove that broader claim, Carr offers a variety of reasons and evidence. Here’s part of his reasoning:

Thanks to the ubiquity of text on the Internet, not to mention the popularity of text-messaging on cell phones, we may well be reading more today than we did in the 1970s or 1980s, when television was our medium of choice. But it’s a different kind of reading, and behind it lies a different kind of thinking—perhaps even a new sense of the self. point “We are not only what we read,” says Maryanne Wolf, a developmental psychologist at Tufts University and the author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain . “We are how we read.” Wolf worries that the style of reading promoted by the Net, a style that puts “efficiency” and “immediacy” above all else, may be weakening our capacity for the kind of deep reading that emerged when an earlier technology, the printing press, made long and complex works of prose commonplace. When we read online, she says, we tend to become “mere decoders of information.” evidence Our ability to interpret text, to make the rich mental connections that form when we read deeply and without distraction, remains largely disengaged. analysis

This excerpt only contains the first three elements, PEA, and the analysis part is very brief (it’s more like paraphrase), but it shows how professional writers often employ some version of the formula. It tends to appear in persuasive texts written by experienced writers because it reinforces writing techniques mentioned elsewhere in this textbook. A block of text structured according to PEA will practice coherence, because opening with a point (P) forecasts the main idea of that section. Embedding the evidence (E) within a topic sentence and follow-up commentary or analysis (A) is part of the “quote sandwich” strategy we cover in the section on “Writing With Sources.”

Use “they say / i say” strategies for Counterarguments and rebuttals

Another element that’s unique to persuasive essays is embedding a counterargument. Sometimes called naysayers or opposing positions, counterarguments are points of view that challenge our own.

Why embed a naysayer?

Recall above how a helpful strategy for beginning a persuasive essay (the introduction) is to briefly mention a debate—what some writing textbooks call “joining the conversation.” Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein’s They Say / I Say explains why engaging other points of view is so crucial:

Not long ago we attended a talk at an academic conference where the speaker’s central claim seemed to be that a certain sociologist—call him Dr. X—had done very good work in a number of areas of the discipline. The speaker proceeded to illustrate his thesis by referring extensively and in great detail to various books and articles by Dr. X and by quoting long pas-sages from them. The speaker was obviously both learned and impassioned, but as we listened to his talk we found ourselves somewhat puzzled: the argument—that Dr. X’s work was very important—was clear enough, but why did the speaker need to make it in the first place? Did anyone dispute it? Were there commentators in the field who had argued against X’s work or challenged its value? Was the speaker’s interpretation of what X had done somehow novel or revolutionary? Since the speaker gave no hint of an answer to any of these questions, we could only wonder why he was going on and on about X. It was only after the speaker finished and took questions from the audience that we got a clue: in response to one questioner, he referred to several critics who had vigorously questioned Dr. X’s ideas and convinced many sociologists that Dr. X’s work was unsound.

When writing for an academic audience, one of the most important moves a writer can make is to demonstrate how their ideas compare to others. It serves as part of the context. Your essay might be offering a highly original solution to a certain problem you’ve researched the entire semester, but the reader will only understand that if existing arguments are presented in your draft. Or, on the other hand, you might be synthesizing or connecting a variety of opinions in order to arrive at a more comprehensive solution. That’s also fine, but the creativity of your synthesis and its unique contribution to existing research will only be known if those other voices are included.

Aristotelian argumentation embeds counterarguments in order to refute them. Rogerian arguments present oppositional stances in order to synthesize and integrate them. No matter what your strategy is, the essay should be conversational.

Notice how Ana Mari Cauce opens her essay on free speech in higher education, “ Messy but Essential “:

Over the past year or two, issues surrounding the exercise of free speech and expression have come to the forefront at colleges around the country. The common narrative about free speech issues that we so often read goes something like this: today’s college students — overprotected and coddled by parents, poorly educated in high school and exposed to primarily left-leaning faculty — have become soft “snowflakes” who are easily offended by mere words and the slightest of insults, unable or unwilling to tolerate opinions that veer away from some politically correct orthodoxy and unable to engage in hard-hitting debate. counterargument

This is false in so many ways, and even insulting when you consider the reality of students’ experiences today. claim

The introduction to her article is essentially a counteragument (which serves as her introductory context) followed by a response. Embedding naysayers like this can appear anywhere in an essay, not just the introduction. Notice, furthermore, how Cauce’s naysayer isn’t gleaned from any research she did. It’s just a general, trendy naysayer, something one might hear nowadays, in the ether. It shows she’s attuned to an ongoing conversation, but it doesn’t require her to cite anything specific. As the previous chapter on using rhetorical appeals in arguments explained, this kind of attunement with an emerging problem (or exigence) is known as the appeal to kairos . A compelling, engaging introduction will demonstrate that the argument “kairotically” addresses a pressing concern.

Below is a brief overview of what counterarguments are and how you might respond to them in your arguments. This section was developed by Robin Jeffrey, in “ Counterargument and Response “:

Common Types of counterarguments

- Could someone disagree with your claim? If so, why? Explain this opposing perspective in your own argument, and then respond to it.

- Could someone draw a different conclusion from any of the facts or examples you present? If so, what is that different conclusion? Explain this different conclusion and then respond to it.

- Could a reader question any of your assumptions or claims? If so, which ones would they question? Explain and then respond.

- Could a reader offer a different explanation of an issue? If so, what might their explanation be? Describe this different explanation, and then respond to it.

- Is there any evidence out there that could weaken your position? If so, what is it? Cite and discuss this evidence and then respond to it.

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, that does not necessarily mean that you have a weak argument. It means, ideally and as long as your argument is logical and valid, that you have a counterargument. Good arguments can and do have counterarguments; it is important to discuss them. But you must also discuss and then respond to those counterarguments.

Responding to counterarguments

You do not need to attempt to do all of these things as a way to respond; instead, choose the response strategy that makes the most sense to you, for the counterargument that you have.

- If you agree with some of the counterargument perspectives, you can concede some of their points. (“I do agree that ….”, “Some of the points made by ____ are valid…..”) You could then challenge the importance/usefulness of those points. “However, this information does not apply to our topic because…”

- If the counterargument perspective is one that contains different evidence than you have in your own argument, you can explain why a reader should not accept the evidence that the counterarguer presents.

- If the counterargument perspective is one that contains a different interpretation of evidence than you have in your own argument, you can explain why a reader should not accept the interpretation of the evidence that that your opponent (counterarguer) presents.

- If the counterargument is an acknowledgement of evidence that threatens to weaken your argument, you must explain why and how that evidence does not, in fact invalidate your claim.

It is important to use transitional phrases in your paper to alert readers when you’re about to present an counterargument. It’s usually best to put this phrase at the beginning of a paragraph such as:

- Researchers have challenged these claims with…

- Critics argue that this view…

- Some readers may point to…

- A perspective that challenges the idea that . . .

Transitional phrases will again be useful to highlight your shift from counterargument to response:

- Indeed, some of those points are valid. However, . . .

- While I agree that . . . , it is more important to consider . . .

- These are all compelling points. Still, other information suggests that . .

- While I understand . . . , I cannot accept the evidence because . . .

Further reading

To read more about the importance of counterarguments in academic writing, read Steven D. Krause’s “ On the Other Hand: The Role of Antithetical Writing in First Year Composition Courses .”

When concluding, address the “so what?” challenge

As Joseph W. Williams mentions in his chapter on concluding persuasive essays in Style ,

a good introduction motivates your readers to keep reading, introduces your key themes, and states your main point … [but] a good conclusion serves a different end: as the last thing your reader reads, it should bring together your point, its significance, and its implications for thinking further about the ideas your explored.

At the very least, a good persuasive conclusion will

- Summarize the main points

- Address the So what? or Now what? challenge.

When summarizing the main points of longer essays, Williams suggests it’s fine to use “metadiscourse,” such as, “I have argued that.” If the essay is short enough, however, such metadiscourses may not be necessary, since the reader will already have those ideas fresh in their mind.

After summarizing your essay’s main points, imagine a friendly reader thinking,

“OK, I’m persuaded and entertained by everything you’ve laid out in your essay. But remind me what’s so important about these ideas? What are the implications? What kind of impact do you expect your ideas to have? Do you expect something to change?”

It’s sometimes appropriate to offer brief action points, based on the implications of your essay. When addressing the “So what?” challenge, however, it’s important to first consider whether your essay is primarily targeted towards changing the way people think or act . Do you expect the audience to do something, based on what you’ve argued in your essay? Or, do you expect the audience to think differently? Traditional academic essays tend to propose changes in how the reader thinks more than acts, but your essay may do both.

Finally, Williams suggests that it’s sometimes appropriate to end a persuasive essay with an anecdote, illustrative fact, or key quote that emphasizes the significance of the argument. We can see a good example of this in Carr’s article, “ Is Google Making Us Stupid? ” Here are the introduction and conclusion, side-by-side: Definition: Term

[Introduction] “Dave, stop. Stop, will you? Stop, Dave. Will you stop, Dave?” So the supercomputer HAL pleads with the implacable astronaut Dave Bowman in a famous and weirdly poignant scene toward the end of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey . Bowman, having nearly been sent to a deep-space death by the malfunctioning machine, is calmly, coldly disconnecting the memory circuits that control its artificial “ brain. “Dave, my mind is going,” HAL says, forlornly. “I can feel it. I can feel it.”

I can feel it, too. Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory. …