An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Lippincott Open Access

Evidence-Based Practice and Nursing Research

Evidence-based practice is now widely recognized as the key to improving healthcare quality and patient outcomes. Although the purposes of nursing research (conducting research to generate new knowledge) and evidence-based nursing practice (utilizing best evidence as basis of nursing practice) seem quite different, an increasing number of research studies have been conducted with the goal of translating evidence effectively into practice. Clearly, evidence from research (effective innovation) must be accompanied by effective implementation, and an enabling context to achieve significant outcomes.

As mentioned by Professor Rita Pickler, “nursing science needs to encompass all manner of research, from discovery to translation, from bench to bedside, from mechanistic to holistic” ( Pickler, 2018 ). I feel that The Journal of Nursing Research must provide an open forum for all kind of research in order to help bridge the gap between research-generated evidence and clinical nursing practice and education.

In this issue, an article by professor Ying-Ju Chang and colleagues at National Cheng Kung University presents an evidence-based practice curriculum for undergraduate nursing students developed using an action research-based model. This “evidence-based practice curriculum” spans all four academic years, integrates coursework and practicums, and sets different learning objectives for students at different grade levels. Also in this issue, Yang et al. apply a revised standard care procedure to increase the ability of critical care nurses to verify the placement of nasogastric tubes. After appraising the evidence, the authors conclude that the aspirate pH test is the most reliable and economical method for verifying nasogastric tube placement at the bedside. They subsequently develop a revised standard care procedure and a checklist for auditing the procedure, conduct education for nurses, and examine the effectiveness of the revised procedure.

I hope that these two studies help us all better appreciate that, in addition to innovation and new breakthrough discoveries, curriculum development and evidence-based quality improvement projects, though may not seem so novel, are also important areas of nursing research. Translating evidence into practice is sound science and merits more research.

Cite this article as: Chien, L. Y. (2019). Evidence-based practice and nursing research. The Journal of Nursing Research, 27 (4), e29. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000346

- Pickler R. H. (2018). Honoring the past, pursuing the future . Nursing Research , 67 ( 1 ), 1–2. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000255 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

A nurses' guide to the hierarchy of research designs and evidence

- Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 33(3):38-43

- 33(3):38-43

- University of New England (Australia)

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- MED SCI MONITOR

- Shanto Barman

- Malcolm Masso

- Stephen Webb

- Tina Bedenik

- NURS EDUC TODAY

- Jessica Immonen

- Stephanie J. Richardson

- Online J Issues Nurs

- Sally Borbasi

- Beth S. Finkelstein

- SHIRLEY A. LLORENS

- JPT Higgins

- S(eds) Green

- Sophia M. Schild

- S Bartholomeyczik

- D O'connor

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Joyner Library

- Laupus Health Sciences Library

- Music Library

- Digital Collections

- Special Collections

- North Carolina Collection

- Teaching Resources

- The ScholarShip Institutional Repository

- Country Doctor Museum

Evidence-Based Practice for Nursing: Evaluating the Evidence

- What is Evidence-Based Practice?

- Asking the Clinical Question

- Finding Evidence

- Evaluating the Evidence

- Articles, Books & Web Resources on EBN

Evaluating Evidence: Questions to Ask When Reading a Research Article or Report

For guidance on the process of reading a research book or an article, look at Paul N. Edward's paper, How to Read a Book (2014) . When reading an article, report, or other summary of a research study, there are two principle questions to keep in mind:

1. Is this relevant to my patient or the problem?

- Once you begin reading an article, you may find that the study population isn't representative of the patient or problem you are treating or addressing. Research abstracts alone do not always make this apparent.

- You may also find that while a study population or problem matches that of your patient, the study did not focus on an aspect of the problem you are interested in. E.g. You may find that a study looks at oral administration of an antibiotic before a surgical procedure, but doesn't address the timing of the administration of the antibiotic.

- The question of relevance is primary when assessing an article--if the article or report is not relevant, then the validity of the article won't matter (Slawson & Shaughnessy, 1997).

2. Is the evidence in this study valid?

- Validity is the extent to which the methods and conclusions of a study accurately reflect or represent the truth. Validity in a research article or report has two parts: 1) Internal validity--i.e. do the results of the study mean what they are presented as meaning? e.g. were bias and/or confounding factors present? ; and 2) External validity--i.e. are the study results generalizable? e.g. can the results be applied outside of the study setting and population(s) ?

- Determining validity can be a complex and nuanced task, but there are a few criteria and questions that can be used to assist in determining research validity. The set of questions, as well as an overview of levels of evidence, are below.

For a checklist that can help you evaluate a research article or report, use our checklist for Critically Evaluating a Research Article

- How to Critically Evaluate a Research Article

How to Read a Paper--Assessing the Value of Medical Research

Evaluating the evidence from medical studies can be a complex process, involving an understanding of study methodologies, reliability and validity, as well as how these apply to specific study types. While this can seem daunting, in a series of articles by Trisha Greenhalgh from BMJ, the author introduces the methods of evaluating the evidence from medical studies, in language that is understandable even for non-experts. Although these articles date from 1997, the methods the author describes remain relevant. Use the links below to access the articles.

- How to read a paper: Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about) Not all published research is worth considering. This provides an outline of how to decide whether or not you should consider a research paper. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997b). How to read a paper. Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7102), 243–246.

- Assessing the methodological quality of published papers This article discusses how to assess the methodological validity of recent research, using five questions that should be addressed before applying recent research findings to your practice. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997a). Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7103), 305–308.

- How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests This article and the next present the basics for assessing the statistical validity of medical research. The two articles are intended for readers who struggle with statistics more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997f). How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7104), 364–366.

- How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician II: "Significant" relations and their pitfalls The second article on evaluating the statistical validity of a research article. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997). Education and debate. how to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: "significant" relations and their pitfalls. BMJ: British Medical Journal (International Edition), 315(7105), 422-425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7105.422

- How to read a paper. Papers that report drug trials more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997d). How to read a paper. Papers that report drug trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7106), 480–483.

- How to read a paper. Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997c). How to read a paper. Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7107), 540–543.

- How to read a paper. Papers that tell you what things cost (economic analyses) more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997e). How to read a paper. Papers that tell you what things cost (economic analyses). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7108), 596–599.

- Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997i). Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7109), 672–675.

- How to read a paper: Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) A set of questions that could be used to analyze the validity of qualitative research more... less... Greenhalgh, T., & Taylor, R. (1997). Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7110), 740–743.

Levels of Evidence

In some journals, you will see a 'level of evidence' assigned to a research article. Levels of evidence are assigned to studies based on the methodological quality of their design, validity, and applicability to patient care. The combination of these attributes gives the level of evidence for a study. Many systems for assigning levels of evidence exist. A frequently used system in medicine is from the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine . In nursing, the system for assigning levels of evidence is often from Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt's 2011 book, Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice . The Levels of Evidence below are adapted from Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt's (2011) model.

Uses of Levels of Evidence : Levels of evidence from one or more studies provide the "grade (or strength) of recommendation" for a particular treatment, test, or practice. Levels of evidence are reported for studies published in some medical and nursing journals. Levels of Evidence are most visible in Practice Guidelines, where the level of evidence is used to indicate how strong a recommendation for a particular practice is. This allows health care professionals to quickly ascertain the weight or importance of the recommendation in any given guideline. In some cases, levels of evidence in guidelines are accompanied by a Strength of Recommendation.

About Levels of Evidence and the Hierarchy of Evidence : While Levels of Evidence correlate roughly with the hierarchy of evidence (discussed elsewhere on this page), levels of evidence don't always match the categories from the Hierarchy of Evidence, reflecting the fact that study design alone doesn't guarantee good evidence. For example, the systematic review or meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are at the top of the evidence pyramid and are typically assigned the highest level of evidence, due to the fact that the study design reduces the probability of bias ( Melnyk , 2011), whereas the weakest level of evidence is the opinion from authorities and/or reports of expert committees. However, a systematic review may report very weak evidence for a particular practice and therefore the level of evidence behind a recommendation may be lower than the position of the study type on the Pyramid/Hierarchy of Evidence.

About Levels of Evidence and Strength of Recommendation : The fact that a study is located lower on the Hierarchy of Evidence does not necessarily mean that the strength of recommendation made from that and other studies is low--if evidence is consistent across studies on a topic and/or very compelling, strong recommendations can be made from evidence found in studies with lower levels of evidence, and study types located at the bottom of the Hierarchy of Evidence. In other words, strong recommendations can be made from lower levels of evidence.

For example: a case series observed in 1961 in which two physicians who noted a high incidence (approximately 20%) of children born with birth defects to mothers taking thalidomide resulted in very strong recommendations against the prescription and eventually, manufacture and marketing of thalidomide. In other words, as a result of the case series, a strong recommendation was made from a study that was in one of the lowest positions on the hierarchy of evidence.

Hierarchy of Evidence for Quantitative Questions

The pyramid below represents the hierarchy of evidence, which illustrates the strength of study types; the higher the study type on the pyramid, the more likely it is that the research is valid. The pyramid is meant to assist researchers in prioritizing studies they have located to answer a clinical or practice question.

For clinical questions, you should try to find articles with the highest quality of evidence. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses are considered the highest quality of evidence for clinical decision-making and should be used above other study types, whenever available, provided the Systematic Review or Meta-Analysis is fairly recent.

As you move up the pyramid, fewer studies are available, because the study designs become increasingly more expensive for researchers to perform. It is important to recognize that high levels of evidence may not exist for your clinical question, due to both costs of the research and the type of question you have. If the highest levels of study design from the evidence pyramid are unavailable for your question, you'll need to move down the pyramid.

While the pyramid of evidence can be helpful, individual studies--no matter the study type--must be assessed to determine the validity.

Hierarchy of Evidence for Qualitative Studies

Qualitative studies are not included in the Hierarchy of Evidence above. Since qualitative studies provide valuable evidence about patients' experiences and values, qualitative studies are important--even critically necessary--for Evidence-Based Nursing. Just like quantitative studies, qualitative studies are not all created equal. The pyramid below shows a hierarchy of evidence for qualitative studies.

Adapted from Daly et al. (2007)

Help with Research Terms & Study Types: Cut through the Jargon!

- CEBM Glossary

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine|Toronto

- Cochrane Collaboration Glossary

- Qualitative Research Terms (NHS Trust)

- << Previous: Finding Evidence

- Next: Articles, Books & Web Resources on EBN >>

- Last Updated: Jan 12, 2024 10:03 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ecu.edu/ebn

- SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

- COVID-19 Library Updates

- Make Appointment

Evidence-Based Nursing Research Guide: Evidence Levels & Types

- Key Resources

- Evidence-Based Nursing Definitions

- Evidence Levels & Types

- PICO Search Strategy

- Systematic Reviews This link opens in a new window

- Books & eBooks

- Background Information

- Organizations

Evidence Pyramid

Depending on their purpose, design, and mode of reporting or dissemination, health-related research studies can be ranked according to the strength of evidence they provide, with the sources of strongest evidence at the top, and the weakest at the bottom:

Secondary Sources: studies of studies

Systematic Review

- Identifies, appraises, and synthesizes all empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria

- Methods section outlines a detailed search strategy used to identify and appraise articles

- May include a meta-analysis, but not required (see Meta-Analysis below)

Meta-Analysis

- A subset of systematic reviews: uses quantitative methods to combine the results of independent studies and synthesize the summaries and conclusions

- Methods section outlines a detailed search strategy used to identify and appraise articles; often surveys clinical trials

- Can be conducted independently, or as a part of a systematic review

- All meta-analyses are systematic reviews, but not all systematic reviews are meta-analyses

Evidence-Based Guideline

- Provides a brief summary of evidence for a general clinical question or condition

- Produced by professional health care organizations, practices, and agencies that systematically gather, appraise, and combine the evidence

- Click on the 'Evidence-Based Care Sheets' link located at the top of the CINAHL screen to find short overviews of evidence-based care recommendations covering 140 or more health care topics.

Meta-Synthesis or Qualitative Synthesis (Systematic Review of Qualitative or Descriptive Studies)

- a systematic review of qualitative or descriptive studies, low strength level

Primary Sources: original studies

Randomized Controlled Trial

- Experiment where individuals are randomly assigned to an experimental or control group to test the value or efficiency of a treatment or intervention

Non-Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial (Quasi-Experimental)

- Involves one or more test treatments, at least one control treatment, specified outcome measures for evaluating the studied intervention, and a bias-free method for assigning patients to the test treatment

Case-Control or Case-Comparison Study (Non-Experimental)

- Individuals with a particular condition or disease (the cases) are selected for comparison with individuals who do not have the condition or disease (the controls)

Cohort Study (Non-Experimental)

- Identifies subsets (cohorts) of a defined population

- Cohorts may or may not be exposed to factors that researchers hypothesize will influence the probability that participants will have a particular disease or other outcome

- Researchers follow cohorts in an attempt to determine distinguishing subgroup characteristics

Further Reading

- Levels of Evidence - EBP Toolkit Winona State University

- Levels of Evidence Northern Virginia Community College

- Types of Evidence University of Missouri - St Louis

- << Previous: Evidence-Based Nursing Definitions

- Next: PICO Search Strategy >>

- Last Updated: May 28, 2024 8:43 AM

- URL: https://libguides.depaul.edu/ebp

- Levels of Evidence

When searching for evidence-based information, one should select the highest level of evidence available. Clinicians must understand the types of evidence and their relative quality in the hierarchy of research evidence. The Levels of Evidence pyramid below represents the relative quality of types of evidence with the least clinically relevant at the bottom and the most clinically relevant at the top .

LEVELS OF EVIDENCE

Image adapted from: Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, &Alhadab, F. (2016). New evidence pyramid. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, (English Ed.) , 21 (4), 125–127. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401

- OpenMD Levels of Evidence An overview of the Levels of Evidence pyramid including study types.

Study Types

Systematic Reviews summarize the results of a systematic literature search on a specific clinical question to develop clinical recommendations. The studies are reviewed, assessed, and the results are summarized according to the predetermined criteria of the review question. They assess the methodology, sample size, and quality of the studies, using the highest quality data available to answer specific clinical questions and develop practice recommendations.

Meta-Analysis takes this process one-step further, reviewing a clinical question for which multiple systematic reviews exist and combining all the results using accepted statistical methodology

Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial - A prospective, analytical, experimental study using primary data generated in the clinical environment. Individuals who are similar at the beginning are randomly allocated to two or more groups (treatment and control) and the outcomes of the groups are compared after sufficient follow-up time.

A study that shows the efficacy of a diagnostic test is called a prospective, blind comparison to a gold standard study. This is a controlled trial that looks at patients with varying degrees of an illness and administers both diagnostic tests -- the test under investigation and the "gold standard" test -- to all of the patients in the study.

Cohort Studies identify a large population who already has a specific exposure or treatment, follows them over time (prospective), and compares outcomes with another group that has not been affected by the exposure or treatment being studied. Cohort studies are observational and not as reliable as randomized controlled studies, since the two groups may differ in ways other than in the variable under study.

Case Control Studies are studies in which patients who already have a specific condition or outcome are compared with people who do not. Researchers look back in time (retrospective) to identify possible exposures. They often rely on medical records and patient recall for data collection. These types of studies are often less reliable than randomized controlled trials and cohort studies because showing a statistical relationship does not mean than one factor necessarily caused the other.

Case Series and Case Reports consist of collections of reports on the treatment of individual patients or a report on a single patient. Because they are reports of cases and use no control groups with which to compare outcomes, they have no statistical validity.

Background Information / Expert Opinion use varied evidence to present information that ranges from expert opinion to providing summaries of well-known information with established evidence. They are good resources to begin understanding a topic, learning definitions, and clinical parameters. However, when answering an EBP question, look for information with statistically significant data from resources higher-up in the pyramid.

Source: Duke University Medical Center Library: Evidence-Based Medicine Resources

Filtered Information vs Unfiltered Information

Filtered Information - Information that has been collected and aggregated by expert analysis and review. The quality of the studies has already been appraised and recommendations for practice may have already been made. Examples include systematic reviews and meta-analyses .

Unfiltered Information - Primary or original research studies. Original research studies that have not yet been synthesized or aggregated such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies and case-control studies, which are often published in peer-reviewed journals. These studies have not undergone additional analysis and review beyond that of the peer review process for each study.

- << Previous: Finding the Evidence

- Next: Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses >>

- Evidence-Based Medicine/Evidence-Based Practice

- Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing

- EBP in Nursing: More Resources

- Question Types

- Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses

- Study Types & Terminology

- Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research

- Critical Appraisal: Evaluating Studies

- Conducting a Systematic Review

- Research Study Design

- Selected Print and Electronic Reference Books for EBP

- Finding a Book on the Shelf by Call Number

- Finding EBP Articles in the Databases

- Selected Evidence Based Practice Journals

- Finding the Full Text of an Article from a Citation

- Intro to Nursing Databases

- Databases for EBP

- Intro to Nursing Resources

- Citation Management Programs

- Sample Annotated Bibliography

- Last Updated: Jun 7, 2024 4:03 PM

- URL: https://libguides.adelphi.edu/evidence-based-practice

Levels of Evidence and Study Design: Levels of Evidence

Levels of evidence.

- Study Design

- Study Design by Question Type

- Rating Systems

This is a general set of levels to aid in critically evaluating evidence. It was adapted from the model presented in the book, Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2019). Some specialties may have adopted a slightly different and/or smaller set of levels.

Evidence from a clinical practice guideline based on systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Is this is not available, then evidence from a systematic review or meta-analysis of random controlled trials.

Evidence from randomized controlled studies with good design.

Evidence from controlled trials that have good design but are not randomized.

Evidence from case-control and cohort studies with good design.

Evidence from systematic reviews of qualitative and descriptive studies.

Evidence from qualitative and descriptive studies.

Evidence from the opinion of authorities and/or the reports of expert committees.

Evidence Pyramid

The pyramid below is a hierarchy of evidence for quantitative studies. It shows the hierarchy of studies by study design; starting with secondary and reappraised studies, then primary studies, and finally reports and opinions, which have no study design. This pyramid is a simplified, amalgamation of information presented in the book chapter “Evidence-based decision making” (Forest et al., 2019) and book Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2019).

Evidence Table for Nursing

Advocate Health - Midwest provides system-wide evidence based practice resources. The Nursing Hub* has an Evidence-Based Quality Improvement (EBQI) Evidence Table , within the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Resource. It also includes information on evidence type, and a literature synthesis table.

*The Nursing Hub requires access to the Advocate Health - Midwest SharePoint platform.

Forrest, J. L., Miller, S. A., Miller, G. W., Elangovan, S., & Newman, M. G. (2019). Evidence-based decision making. In M. G. Newman, H. H. Takei, P. R. Klokkevold, & F. A. Carranza (Eds.), Newman and Carranza's clinical periodontology (13th ed., pp. 1-9.e1). Elsevier.

- Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: A guide to best practice (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Study Design >>

- Last Updated: Dec 29, 2023 2:03 PM

- URL: https://library.aah.org/guides/levelsofevidence

Nursing-Johns Hopkins Evidence-Based Practice Model

Jhebp model for levels of evidence, jhebp levels of evidence overview.

- Levels I, II and III

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) uses a rating system to appraise evidence (usually a research study published as a journal article). The level of evidence corresponds to the research study design. Scientific research is considered to be the strongest form of evidence and recommendations from the strongest form of evidence will most likely lead to the best practices. The strength of evidence can vary from study to study based on the methods used and the quality of reporting by the researchers. You will want to seek the highest level of evidence available on your topic (Dang et al., 2022, p. 130).

The Johns Hopkins EBP model uses 3 ratings for the level of scientific research evidence

- true experimental (level I)

- quasi-experimental (level II)

- nonexperimental (level III)

The level determination is based on the research meeting the study design requirements (Dang et al., 2022, p. 146-7).

You will use the Research Appraisal Tool (Appendix E) along with the Evidence Level and Quality Guide (Appendix D) to analyze and appraise research studies . (Tools linked below.)

N onresearch evidence is covered in Levels IV and V.

- Evidence Level and Quality Guide (Appendix D)

- Research Evidence Appraisal Tool (Appendix E)

Level I Experimental study

randomized controlled trial (RCT)

Systematic review of RCTs, with or without meta-analysis

Level II Quasi-experimental Study

Systematic review of a combination of RCTs and quasi-experimental, or quasi-experimental studies only, with or without meta-analysis.

Level III Non-experimental study

Systematic review of a combination of RCTs, quasi-experimental and non-experimental, or non-experimental studies only, with or without meta-analysis.

Qualitative study or systematic review, with or without meta-analysis

Level IV Opinion of respected authorities and/or nationally recognized expert committees/consensus panels based on scientific evidence.

Clinical practice guidelines

Consensus panels

Level V Based on experiential and non-research evidence.

Literature reviews

Quality improvement, program, or financial evaluation

Case reports

Opinion of nationally recognized expert(s) based on experiential evidence

These flow charts can also help you detemine the level of evidence throigh a series of questions.

Single Quantitative Research Study

Summary/Reviews

These charts are a part of the Research Evidence Appraisal Tool (Appendix E) document.

Dang, D., Dearholt, S., Bissett, K., Ascenzi, J., & Whalen, M. (2022). Johns Hopkins evidence-based practice for nurses and healthcare professionals: Model and guidelines. 4th ed. Sigma Theta Tau International

- << Previous: Start Here

- Next: Levels I, II and III >>

- Last Updated: Feb 8, 2024 1:24 PM

- URL: https://bradley.libguides.com/jhebp

Nursing - Systematic Reviews: Levels of Evidence

- Levels of Evidence

- Meta-Analyses

- Definitions

- Citation Search

- Write & Cite

- Give Feedback

"How would I use the 6S Model while taking care of a patient?" .cls-1{fill:#fff;stroke:#79a13f;stroke-miterlimit:10;stroke-width:5px;}.cls-2{fill:#79a13f;} The 6S Model is designed to work from the top down, starting with Systems - also referred to as computerized decision support systems (CDSSs). DiCenso et al. describes that, “an evidence-based clinical information system integrates and concisely summarizes all relevant and important research evidence about a clinical problem, is updated as new research evidence becomes available, and automatically links (through an electronic medical record) a specific patient’s circumstances to the relevant information” (2009). Systematic reviews lead up to this type of bio-available level of evidence.

What are systematic reviews, polit–beck evidence hierarchy/levels of evidence scale for therapy questions.

"Figure 2.2 [in context of book] shows our eight-level evidence hierarchy for Therapy/intervention questions. This hierarchy ranks sources of evidence with respect the readiness of an intervention to be put to use in practice" (Polit & Beck, 2021, p. 28). Levels are ranked on risk of bias - level one being the least bias, level eight being the most biased. There are several types of levels of evidence scales designed for answering different questions. "An evidence hierarchy for Prognosis questions, for example, is different from the hierarchy for Therapy questions" (p. 29).

Advantages of Levels of Evidence Scales

"Through controls imposed by manipulation, comparison, and randomization, alternative explanations can be discredited. It is because of this strength that meta-analyses of RCTs, which integrate evidence from multiple experiments, are at the pinnacle of the evidence hierarchies for Therapy questions" (p. 188).

"Tip: Traditional evidence hierarchies or level of evidence scales (e.g., Figure 2.2), rank evidence sources almost exclusively based on the risk of internal validity threats" (p. 217).

Systematic reviews can provide researchers with knowledge that prior evidence shows. This can help clarify established efficacy of a treatment without unnecessary and thus unethical research. Greenhalgh (2019) illustrates this citing Dean Fergusson and colleagues (2005) systematic review on a clinical surgical topic (p. 128).

Limits of Levels of Evidence Scales

Regarding the importance of real-world clinical practice settings, and the conflicting tradeoffs between internal and external validity, Polit and Beck (2021) write, "the first (and most prevalent) approach is to emphasize one and sacrifice another. Most often, it is external validity that is sacrificed. For example, external validity is not even considered in ranking evidence in level of evidence scales" (p. 221). ... From an EBP perspective, it is important to remember that drawing inferences about causal relationships relies not only on how high up on the evidence hierarchy a study is (Figure 2.2), but also, for any given level of the hierarchy, how successful the researcher was in managing study validity and balancing competing validity demands" (p. 222).

Polit and Beck note Levin (2014) that an evidence hierarchy "is not meant to provide a quality rating for evidence retrieved in the search for an answer" (p. 6), and as the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine concurs that evidence scales are, 'NOT intended to provide you with a definitive judgment about the quality of the evidence. There will inevitably be cases where "lower-level" evidence...will provide stronger than a "higher level" study (Howick et al., 2011, p.2)'" (p. 30).

Level of evidence (e.g., Figure 2.2) + Quality of evidence = Strength of evidence .

The 6S Model of Levels of Evidence

"The 6S hierarchy does not imply a gradient of evidence in terms of quality , but rather in terms of ease in retrieving relevant evidence to address a clinical question. At all levels, the evidence should be assessed for quality and relevance" (Polit & Beck, 2021, p. 24, Tip box).

The 6S Pyramid proposes a structure of quantitative evidence where articles that include pre-appraised and pre-synthesized studies are located at the top of the hierarchy (McMaster U., n.d.).

It can help to consider the level of evidence that a document represents, for example, a scientific article that summarizes and analyses many similar articles may provide more insight than the conclusion of a single research article. This is not to say that summaries can not be flawed, nor does it suggest that rare case studies should be ignored. The aim of health research is the well-being of all people, therefore it is important to use current evidence in light of patient preferences negotiated with clinical expertise.

Other Gradings in Levels of Evidence

While it is accepted that the strongest evidence is derived from meta-analyses, various evidence grading systems exist. for example: The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice model ranks evidence from level I to level V, as follows (Seben et al., 2010): Level I: Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs); experimental studies; RCTs Level II: Quasi-experimental studies Level III: Non-experimental or qualitative studies Level IV: Opinions of nationally recognized experts based on research evidence or an expert consensus panel Level V: Opinions of individual experts based on non-research evidence (e.g., case studies, literature reviews, organizational experience, and personal experience) The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) evidence level system , updated in 2009, ranks evidence as follows (Armola et al., 2009): Level A: Meta-analysis of multiple controlled studies or meta-synthesis of qualitative studies with results that consistently support a specific action, intervention, or treatment Level B: Well-designed, controlled randomized or non-randomized studies with results that consistently support a specific action, intervention, or treatment Level C: Qualitative, descriptive, or correlational studies, integrative or systematic reviews, or RCTs with inconsistent results Level D: Peer-reviewed professional organizational standards, with clinical studies to support recommendations Level E: Theory-based evidence from expert opinion or multiple case reports Level M: Manufacturers’ recommendations (2017)

EBM Pyramid and EBM Page Generator

Unfiltered are resources that are primary sources describing original research. Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-controlled studies, and case series/reports are considered unfiltered information.

Filtered are resources that are secondary sources which summarize and analyze the available evidence. They evaluate the quality of individual studies and often provide recommendations for practice. Systematic reviews, critically-appraised topics, and critically-appraised individual articles are considered filtered information.

Armola, R. R., Bourgault, A. M., Halm, M. A., Board, R. M., Bucher, L., Harrington, L., ... Medina, J. (2009). AACN levels of evidence. What's new? Critical Care Nurse , 29 (4), 70-73. doi:10.4037/ccn2009969

DiCenso, A., Bayley, L., & Haynes, R. B. (2009). Accessing pre-appraised evidence: Fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. BMJ Evidence-Based Nursing , 12 (4) https://ebn.bmj.com/content/12/4/99.2.short

Fergusson, D., Glass, K. C., Hutton, B., & Shapiro, S. (2005). Randomized controlled trials of Aprotinin in cardiac surgery: Could clinical equipoise have stopped the bleeding?. Clinical Trials , 2 (3), 218-232.

Glover, J., Izzo, D., Odato, K. & Wang, L. (2008). Evidence-based mental health resources . EBM Pyramid and EBM Page Generator. Copyright 2008. All Rights Reserved. Retrieved April 28, 2020 from https://web.archive.org/web/20200219181415/http://www.dartmouth.edu/~biomed/resources.htmld/guides/ebm_psych_resources.html Note. Document removed from host. Old link used with the WayBack Machine of the Internet Archive to retrieve the original webpage on 2/10/21 http://www.dartmouth.edu/~biomed/resources.htmld/guides/ebm_psych_resources.html

Greenhalgh, T. (2019). How to read a paper: The basics of evidence-based medicine and healthcare . (Sixth ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

Haynes, R. B. (2001). Of studies, syntheses, synopses, and systems: The “4S” evolution of services for finding current best evidence. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine , 6 (2), 36-38.

Haynes, R. B. (2006). Of studies, syntheses, synopses, summaries, and systems: the “5S” evolution of information services for evidence-based healthcare decisions. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine , 11 (6), 162-164.

McMaster University (n.d.). 6S Search Pyramid Tool https://www.nccmt.ca/capacity-development/6s-search-pyramid

Polit, D., & Beck, C. (2019). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice . Wolters Kluwer Health.

Schub, E., Walsh, K. & Pravikoff D. (Ed.) (2017). Evidence-based nursing practice: Implementing [Skill Set]. Nursing Reference Center Plus

Seben, S., March, K. S., & Pugh, L. C. (2010). Evidence-based practice: The forum approach. American Nurse Today , 5 (11), 32-34.

- Systematic Review from the Encyclopedia of Nursing Research by Cheryl Holly Systematic reviews provide reliable evidential summaries of past research for the busy practitioner. By pooling results from multiple studies, findings are based on multiple populations, conditions, and circumstances. The pooled results of many small and large studies have more precise, powerful, and convincing conclusions (Holly, Salmond, & Saimbert, 2016) [ references in article ]. This scholarly synthesis of research findings and other evidence forms the foundation for evidence-based practice allowing the practitioner to make up-to-date decisions.

Standards & Guides

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions is the official guide that describes in detail the process of preparing and maintaining Cochrane systematic reviews on the effects of healthcare interventions.

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PRISMA focuses on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials, but can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews of other types of research, particularly evaluations of interventions.

- Systematic Reviews by The Centre for Reviews and Dissemination "The guidance has been written for those with an understanding of health research but who are new to systematic reviews; those with some experience but who want to learn more; and for commissioners. We hope that experienced systematic reviewers will also find this guidance of value; for example when planning a review in an area that is unfamiliar or with an expanded scope. This guidance might also be useful to those who need to evaluate the quality of systematic reviews, including, for example, anyone with responsibility for implementing systematic review findings" (CRD, 2009, p. vi, "Who should use this guide")

- Carrying out systematic literature reviews: An introduction by Alan Davies Systematic reviews provide a synthesis of evidence for a specific topic of interest, summarising the results of multiple studies to aid in clinical decisions and resource allocation. They remain among the best forms of evidence, and reduce the bias inherent in other methods. A solid understanding of the systematic review process can be of benefit to nurses that carry out such reviews, and for those who make decisions based on them. An overview of the main steps involved in carrying out a systematic review is presented, including some of the common tools and frameworks utilised in this area. This should provide a good starting point for those that are considering embarking on such work, and to aid readers of such reviews in their understanding of the main review components, in order to appraise the quality of a review that may be used to inform subsequent clinical decision making (Davies, 2019, Abstract)

- Papers that summarize other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) by Trisha Greenhalgh ... a systematic review is an overview of primary studies that: contains a statement of objectives, sources and methods; has been conducted in a way that is explicit, transparent and reproducible (Figure 9.1) [ Table found in book chapter ]. The most enduring and reliable systematic reviews, notably those undertaken by the Cochrane Collaboration (discussed later in this chapter), are regularly updated to incorporate new evidence (Greenhalgh, 2020, p. 117, Chapter 9).

- A PRISMA assessment of the reporting quality of systematic reviews of nursing published in the Cochrane Library and paper-based journals by Juxia Zhang et al. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) was released as a standard of reporting systematic reviewers (SRs). However, not all SRs adhere completely to this standard. This study aimed to evaluate the reporting quality of SRs published in the Cochrane Library and paper-based journals (Zhang et al., 2019, Abstract).

Cochrane [Username]. (2016, Jan 27). What are systematic reviews? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=egJlW4vkb1Y

Davies, A. (2019). Carrying out systematic literature reviews: An introduction. British Journal of Nursing , 28 (15), 1008–1014. https://doi-org.ezproxy.simmons.edu/10.12968/bjon.2019.28.15.1008

Greenhalgh, T. (2019). Papers that summarize other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses). In How to read a Paper : The basics of evidence-based medicine and healthcare . (Sixth ed., pp. 117-136). Wiley Blackwell.

Holly, C. (2017). Systematic review. In J. Fitzpatrick (Ed.), Encyclopedia of nursing research (4th ed.). Springer Publishing Company. Credo Reference.

Zhang, J., Han, L., Shields, L., Tian, J., & Wang, J. (2019). A PRISMA assessment of the reporting quality of systematic reviews of nursing published in the Cochrane Library and paper-based journals. Medicine , 98 (49), e18099. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000018099

- << Previous: Start

- Next: Meta-Analyses >>

- Last Updated: Nov 3, 2023 1:19 PM

- URL: https://simmons.libguides.com/systematic-reviews

Library Research Guides - University of Wisconsin Ebling Library

Uw-madison libraries research guides.

- Course Guides

- Subject Guides

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Nursing Resources

- Table of Evidence

Nursing Resources : Table of Evidence

- Definitions of

- Professional Organizations

- Nursing Informatics

- Nursing Related Apps

- EBP Resources

- PICO-Clinical Question

- Types of PICO Question (D, T, P, E)

- Secondary & Guidelines

- Bedside--Point of Care

- Pre-processed Evidence

- Measurement Tools, Surveys, Scales

- Types of Studies

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

- Cohort vs Case studies

- Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- Sampling Methods and Statistics

- Systematic Reviews

- Review vs Systematic Review vs ETC...

- Standard, Guideline, Protocol, Policy

- Additional Guidelines Sources

- Peer Reviewed Articles

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- Writing a Research Paper or Poster

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Levels of Evidence (I-VII)

- Reliability

- Validity Threats

- Threats to Validity of Research Designs

- Nursing Theory

- Nursing Models

- PRISMA, RevMan, & GRADEPro

- ORCiD & NIH Submission System

- Understanding Predatory Journals

- Nursing Scope & Standards of Practice, 4th Ed

- Distance Ed & Scholarships

- Assess A Quantitative Study?

- Assess A Qualitative Study?

- Find Health Statistics?

- Choose A Citation Manager?

- Find Instruments, Measurements, and Tools

- Write a CV for a DNP or PhD?

- Find information about graduate programs?

- Learn more about Predatory Journals

- Get writing help?

- Choose a Citation Manager?

- Other questions you may have

- Search the Databases?

- Get Grad School information?

Example of a Table of Evidence

- Evidence table

Assessing the evidence and Building a Table

- EBM-Assessing the Evidence, Critical Appraisal

One of the most important steps in writing a paper is showing the strength and rationale of the evidence you chosen. The following document discusses the reasoning, grading and creation of a "Table of Evidence." While table of evidences can differ, the examples given in this article are a great starting point.

- << Previous: Types of Studies

- Next: Qualitative vs Quantitative >>

- Last Updated: Mar 19, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/nursing

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 20, Issue 3

- Mixed methods research: expanding the evidence base

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Allison Shorten 1 ,

- Joanna Smith 2

- 1 School of Nursing , University of Alabama at Birmingham , USA

- 2 Children's Nursing, School of Healthcare , University of Leeds , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Allison Shorten, School of Nursing, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1720 2nd Ave South, Birmingham, AL, 35294, USA; [email protected]; ashorten{at}uab.edu

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102699

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

‘Mixed methods’ is a research approach whereby researchers collect and analyse both quantitative and qualitative data within the same study. 1 2 Growth of mixed methods research in nursing and healthcare has occurred at a time of internationally increasing complexity in healthcare delivery. Mixed methods research draws on potential strengths of both qualitative and quantitative methods, 3 allowing researchers to explore diverse perspectives and uncover relationships that exist between the intricate layers of our multifaceted research questions. As providers and policy makers strive to ensure quality and safety for patients and families, researchers can use mixed methods to explore contemporary healthcare trends and practices across increasingly diverse practice settings.

What is mixed methods research?

Mixed methods research requires a purposeful mixing of methods in data collection, data analysis and interpretation of the evidence. The key word is ‘mixed’, as an essential step in the mixed methods approach is data linkage, or integration at an appropriate stage in the research process. 4 Purposeful data integration enables researchers to seek a more panoramic view of their research landscape, viewing phenomena from different viewpoints and through diverse research lenses. For example, in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluating a decision aid for women making choices about birth after caesarean, quantitative data were collected to assess knowledge change, levels of decisional conflict, birth choices and outcomes. 5 Qualitative narrative data were collected to gain insight into women’s decision-making experiences and factors that influenced their choices for mode of birth. 5

In contrast, multimethod research uses a single research paradigm, either quantitative or qualitative. Data are collected and analysed using different methods within the same paradigm. 6 7 For example, in a multimethods qualitative study investigating parent–professional shared decision-making regarding diagnosis of suspected shunt malfunction in children, data collection included audio recordings of admission consultations and interviews 1 week post consultation, with interactions analysed using conversational analysis and the framework approach for the interview data. 8

What are the strengths and challenges in using mixed methods?

Selecting the right research method starts with identifying the research question and study aims. A mixed methods design is appropriate for answering research questions that neither quantitative nor qualitative methods could answer alone. 4 9–11 Mixed methods can be used to gain a better understanding of connections or contradictions between qualitative and quantitative data; they can provide opportunities for participants to have a strong voice and share their experiences across the research process, and they can facilitate different avenues of exploration that enrich the evidence and enable questions to be answered more deeply. 11 Mixed methods can facilitate greater scholarly interaction and enrich the experiences of researchers as different perspectives illuminate the issues being studied. 11

The process of mixing methods within one study, however, can add to the complexity of conducting research. It often requires more resources (time and personnel) and additional research training, as multidisciplinary research teams need to become conversant with alternative research paradigms and different approaches to sample selection, data collection, data analysis and data synthesis or integration. 11

What are the different types of mixed methods designs?

Mixed methods research comprises different types of design categories, including explanatory, exploratory, parallel and nested (embedded) designs. 2 Table 1 summarises the characteristics of each design, the process used and models of connecting or integrating data. For each type of research, an example was created to illustrate how each study design might be applied to address similar but different nursing research aims within the same general nursing research area.

- View inline

Types of mixed methods designs*

What should be considered when evaluating mixed methods research?

When reading mixed methods research or writing a proposal using mixed methods to answer a research question, the six questions below are a useful guide 12 :

Does the research question justify the use of mixed methods?

Is the method sequence clearly described, logical in flow and well aligned with study aims?

Is data collection and analysis clearly described and well aligned with study aims?

Does one method dominate the other or are they equally important?

Did the use of one method limit or confound the other method?

When, how and by whom is data integration (mixing) achieved?

For more detail of the evaluation guide, refer to the McMaster University Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. 12 The quality checklist for appraising published mixed methods research could also be used as a design checklist when planning mixed methods studies.

- Elliot AE , et al

- Creswell JW ,

- Plano ClarkV L

- Greene JC ,

- Caracelli VJ ,

- Ivankova NV

- Shorten A ,

- Shorten B ,

- Halcomb E ,

- Cheater F ,

- Bekker H , et al

- Tashakkori A ,

- Creswell JW

- 12. ↵ National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools . Appraising qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies included in mixed studies reviews: the MMAT . Hamilton, ON : BMJ Publishing Group , 2015 . http://www.nccmt.ca/resources/search/232 (accessed May 2017) .

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2024

Assessing nurses’ professional competency: a cross-sectional study in Palestine

- Rasha Abu Zaitoun 1 , 2

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 379 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

89 Accesses

Metrics details

Evaluating nurses’ professional competence is critical for ensuring high-quality patient care. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the nurses’ professional competence level and to identify differences based on demographics in three West Bank hospitals.

A cross-sectional design was used, and a convenient sample of 206 nurses participated in the study. The Nurse Professional Competence (NPC) Scale was used to assess the competency level. The investigator distributed the questionnaire and explained the aim of the research. Consent forms were signed before the data collection.

The average competency level was 79% (SD = 11.5), with 90% being professionally competent nurses. The average “nursing care” competency was 79% (SD = 12.98), and the competency level in providing value-based care was 80% (SD = 13.35). The average competency level in technical and medical care was 78% (SD = 13.45), whereas 79% (SD = 12.85) was the average competence level in “Care Pedagogics” and “Documentation and Administration “. The average competence level in the development and leadership subscale was 78% (SD = 12.22). Nurses who attended three to five workshops had a higher level of Nursing Care Competency, (H = 11.98, p = 0.003), and were more competent in value-based care (H = 9.29, p = 0.01); in pedagogical care and patient education (H = 15.16, P = 0.001); and in providing medical and technical care (H = 12.37, p = 0.002). Nurses attending more than five workshops were more competent in documentation and administration (H = 12.55, p = 0.002), and in development and leadership subscale ( H = 7.96, p = 0.20).

The study revealed that participants lacked development and leadership skills. Engagement in workshops positively impacted the level of competencies among nurses. Notably, those attending more than five workshops exhibited greater competence in documentation, administration, development, and leadership in nursing care.

Implications

This study emphasized the role of continuing education in improving nurses’ competencies and highlighted the need to conduct the study at a wider aspect to involve more hospitals with various affiliations to help structure more sensitive professional development and adopt the competencies as an integral part of staff development.

Peer Review reports

In the contemporary world, scholars prioritize the significance and function of human resources in the progress of nations; furthermore, they assert that an organization’s most critical asset is its human capital [ 1 ]. Nurses play a critical role as the primary and most valuable human resource in healthcare organizations [ 2 ]. With significant advancements in science and technology, cost control measures, and limited time for building therapeutic patient relationships, nurses are increasingly concerned about patient safety and quality of care and are committed to improving and maintaining their competencies [ 3 ].

Contemporary perspectives on professionalism underscore that enhancing the quality of healthcare is a moral and professional obligation of all medical practitioners, especially nurses. Thus, they must exhibit dedication to professional competence, transparency with patients, and improvement of care quality [ 4 ]. Professional competency is crucial in providing nursing care, and it involves adhering to professional standards [ 5 ]. The literature extensively addresses nursing competency in terms of patient safety and the quality of care provided [ 6 ].

The Novice to Expert Theory by Patricia Benner emphasizes the importance of nursing competency. Benner’s theory supports the formation of competent and trained nurses who can address the various problems of modern healthcare by offering a developmental framework, encouraging experiential learning, promoting mentorship, and improving patient safety.

skilled and knowledgeable nurses who provide high-quality care, advance patient safety, and influence good outcomes in healthcare delivery. This study is supported by Benner’s theory that emphasizes the effect of nurses’ competency on patient outcomes [ 7 ] Identifying the level of professional competency could help categorize nurses based on their level of practice and determine the proper approach to move nurses from novice to expert.

Professional competency in nurses is defined as a combination of skills, knowledge, attitudes, values, and abilities that facilitate effective performance in occupational and professional roles [ 8 ]. It involves using knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, communication, emotions, and values and rethinking daily activities to provide services to individuals and society, reflecting sound judgment and habits [ 9 ].

Globally, the professional empowerment and competency of nurses are a focus of human resource management in healthcare systems, and the World Health Organization mandates that member countries report and implement plans to strengthen nurses’ competencies [ 10 ]. Nursing competency leads to improving the quality of care, increasing patient satisfaction, enhancing nursing education, and promoting nursing as a profession [ 11 ]. Patients expect competent behavior from nurses, and following the high prevalence of medical incidents, the public and media have become concerned about clinicians’ competency [ 12 ]. Thus, professionals must demonstrate their clinical competence to perform specific roles [ 13 ]. Neglecting nursing competency can cause problems for organizations, resulting in frustration, job dissatisfaction, and attrition [ 14 ].

Professional skills and competency have an impact on job attitudes, including organizational commitment and professional affiliations [ 15 ]. To achieve the goals of the healthcare system, manpower requires not only expertise, empowerment, and competency but also high levels of organizational attachment and commitment, as well as a willingness to participate in activities beyond their predetermined duties; hence, the levels of attachment and commitment of nurses to their affiliated organizations can affect the promotion of their clinical competency [ 1 ].

Nursing competency is a fundamental skill that is essential for meeting nursing obligations; hence, it is crucial to have a clear understanding of the nursing competency level to establish the basis for nursing education programs, and professional development planning and it is vital to recognize the process of nursing competency development to ensure ongoing professional growth following the acquisition of a nursing license [ 5 ]. The fundamental concept of professional competency in nursing has a direct correlation with enhancing patient care quality and safety [ 1 ].

Currently, in Palestine, there exist various levels of nurses who have graduated from a variety of nursing schools within and outside the country. Consequently, there is a diversity in their practices both at an individual and institutional level, posing a challenge to both evaluating the quality of care delivered and standardizing nursing practices nationwide. One proposed strategy to address these obstacles involves conducting an initial assessment of nurses’ competencies to establish a foundation, followed by devising a standardized professional development scheme informed by the gathered data. Unfortunately, there is a notable absence of studies that have investigated the professional competencies of nurses across different nursing specialties, leading to the absence of a comprehensive national framework for appraising nursing competencies and a lack of a standardized approach for assessing competencies.

Given that nurses are frontline healthcare providers delivering population-based health services and gatekeepers for maintaining patient safety their competency level is critical to ensure their ability to perform their daily duties effectively and efficiently to maintain high-quality care also it is an important objective method to help the nursing administrative to assess their employees level of practices and set suitable improvement plans Therefore, it is essential to measure nurses’ competency and, once measured, to establish a standard against which practice domain and performance can be evaluated. This approach provides a framework for ensuring nurses possess the necessary knowledge and skills to carry out their responsibilities effectively.

The Joint Commission Accreditation requires measuring different types of competencies based on the main patient safety goals such as infection control practices and recommends health institutions align with an organization’s strategies, business objectives, and culture for success [ 16 ]. Most commonly measured competencies verify specific nursing skills and practices and tho, but, there are limited efforts to assess the overall nursing professional competence level.

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt to assess the level of professional competence among nurses. The choice was made to carry out this investigation within a tertiary hospital that holds accreditation from JCI. This decision was based on the premise that nurses in such settings have been immersed in a system of competency-based evaluation, potentially yielding more insightful responses compared to their counterparts in non-JCI-accredited hospitals. Furthermore, JCI-accredited hospitals typically offer ongoing professional development initiatives. The advancement of these programs requires a thorough understanding of the overall professional competence level, which is essential for structuring purposeful developmental activities.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the level of professional competence among nurses in a tertiary hospital in the West Bank using the Nurse Professional Competence (NPC) Scale, which evaluates self-reported professional competence.

Study design and settings

A cross-sectional descriptive-analytic design was used to recruit the targeted participants from academic, private, and Ministry of Health hospitals. The data were collected from April to July 2023.

Research procedure and sample

The sample was convenient to reach nurses in their place of work easily during their working time. The sample size was calculated using a Raosoft calculator ( http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html ) with a confidence level of 95%, a marginal error of 5%, and a response distribution of 50%. The estimated sample size was 286, with an attrition rate of 5%. The sample included registered nurses who provided direct patient care and had at least one year of experience in their current workplace. Head nurses, nurses who worked in the administrative field, nurses on maternal, annual, and unpaid leave, and aid nurses were excluded. Questionnaires that were completed by less than 60% of the participants were excluded from the study according to the recommendation of the original author of the tool [ 17 ]. A total of 206 nurses responded and were actively engaged in the study.

Data were gathered over a single month through the use of a self-reported, paper-based questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered in the English language because the intended participants consisted of nurses who predominantly used English for documentation and communication purposes. The questionnaires were directly distributed to the participants, allowing them to peruse the consent form, research objectives, and ethical considerations while simultaneously being encouraged to submit any inquiries they may have had. The initial page of the instrument included a description of the research aim, a consent form, and the contact information of the author.

Research instrument

The data collection questionnaire consisted of two parts: the first part included demographic and workplace information, and the second part included the short version of the Nurse Professional Competence Scale (NPC), which was utilized to assess self-reported professional competence among nurses [ 18 ]. The Nurse Professional Competence Scale was developed by Jan Nilsson and colleagues [ 17 ] in Sweden based on Swedish national guidelines and the World Health Organization’s European Strategy for Nursing and Midwifery [ 19 ]. The original NPC scale comprises eight competency domains and a total of 88 items grouped into eight competence areas, namely, nursing care, value-based nursing care, medical and technical care, teaching/learning and support, documentation and information technology, legislation in nursing and safety planning, leadership in and development of nursing care, and education. For this study, the short version of the NPC was used [ 17 ]. The reliability and validity of the NPC Scale have been confirmed in previous studies, and the Cronbach’s alpha values of all the domains were > 0.70 [ 18 ]. .

The Nurse Professional Competence Scale has been validated and shown to have good reliability and validity in various studies conducted in the Swedish language version [ 20 ]. Responses are given on a seven-point scale ranging from a very low degree (1) to a very high degree (7), with “either high or low degree” coded as (4) [ 21 ]. The competency levels were classified into four categories based on the average score of the scale and subscales: low level (0–25), rather good level (> 25–50), good level (> 50–75), and very good level (> 75–100) [ 22 ].

For this study, Permission was obtained from the authors to use the instrument and they gave instructions to analyze the scale the instrument was piloted on 10 nurses who were excluded from the study. Some modifications were made based on the results to enhance the readability and readability of the study. The needed completion time was from 10 to 15 min.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 was used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics in terms of percentage, mean and standard deviation were used to describe the demographic and work environment factors. The competency subscale scores were calculated following the formulas recommended by the author of the short version of the NPC. The nursing care competence level was calculated by summing item numbers one through 5 divided by 25 and multiplied by 100. The value-based nursing care competence level was obtained by summing the items ranging from six to ten divided by 35 and multiplied by 100. The medical and technical care competence level was estimated by summing the results of items 11 to 16 divided by 42 and multiplied by 100. The competence level in the care pedagogic was the result of summing the items ranging from 17 to 21 divided by 35 and multiplied by 100. The documentation and administrative competence level was calculated by summing the items ranging from 22 to 29 dividing by 56 and multiplying by 100; finally, the leadership and organization subscale was assessed by summing the items from 30 to 35 dividing by 42, and multiplying by 100 [ 17 ]. Moreover, the data were not normally distributed; thus, the Mann‒Whitney test and the Kruskal‒Wallis test were used to analyze the associations between demographic information and professional competency subscale scores. A p -value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethical considerations

The institutional review board of the Arab American University (AAUP) IRB NO. 2023/A/59. All nurses were given both verbal and written information about the aim and objectives of the study, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were assured that their confidentiality and anonymity would be preserved, that their participation was voluntary, and that they could withdraw at any time without any penalties.

Demographics and work environment factors

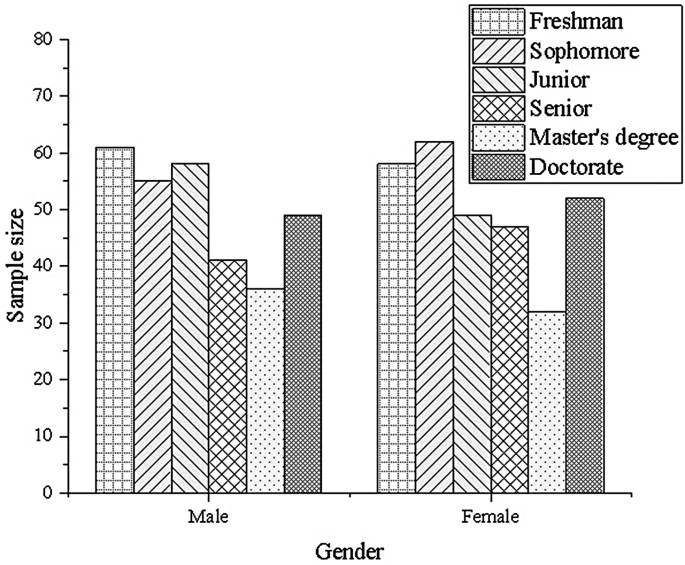

A total of 206 nurses, with a response rate of 72%, participated in this study to assess their professional competence level. The mean age of the participants was 29.5 years, with a minimum of 21 years and a maximum of 45 years. Male nurses represented 52.4% of the participants ( n = 108). The majority held a bachelor’s degree in nursing ( n = 168), and 22 (10.7%) nurses held postgraduate certificates. 57% of the nurses earned a monthly income of 500–1000 JD ( n = 57.8). 94% of the respondents received up to five courses per year. Nearly half ( n = 94) of the participants worked as instructors for nursing students. Among those with less than six years of experience, 97 (47.1%) and 11.7% ( n = 24) had 12 or more years of experience, respectively (Table 1 ).

The professional competence level and subscales

Table 2 showed that the average professional competence level was 79% (SD = 11.5), with a median of 80, a minimum of 45% and a maximum of 100%. A total of 90% of the nurses were professionally competent, while 15 nurses had a competence level of less than 60%. The average “nursing care” competency was 79% (SD = 12.98), with a minimum of 34% and a maximum of 100%. The competency level of providing value-based care was 80% (SD = 13.35), with a minimum of 20% and a maximum of 100%. An average of 78% (SD = 13.45) of the participants were competent at providing technical and medical care, for a minimum of 21%. The nurses also showed an average competence level of 79% (SD = 12.85) in “Care Pedagogics”, with a minimum score of 34% and a maximum of 100%. Similarly, 79% (SD = 12.15) of the participants had an average competence level in “documentation and administration of nursing care”, for a minimum of 39%. Finally, the average competence level of the “Development, leadership and organization of Nursing Care” factor was 78% (SD = 12.22), with a minimum score of 48% and a maximum of 100% (see Table 2 ).

The difference in competency subscale scores among nurses

A significant relationship was found between the number of workshops attended by nurses and their level of competence in all competency areas. In Nursing Care, nurses who attended between three and five in-service education workshops had a higher level of Nursing Care Competency, with a mean rank of 122.39 (H = 11.98, p = 0.003) (see Table 3 ). Table 4 indicated that nurses who attended three to five workshops had a higher level of competency in applying value-based care, with a mean rank = 119.65 (H = 9.29, p = 0.01); in pedagogical care and patient education, with a mean rank of 123.1 (H = 15.16, P = 0.001) (see Table 5 ); and in providing medical and technical care, with a mean rank of 121.88 (H = 12.37, p = 0.002) (see Table 6 ).

Table 7 revealed that nurses who attended more than five workshops were more competent in documenting and administering nursing care, with a mean rank of 130.0 (H = 12.55, p = 0.002), and in developing and leading nursing care (mean rank = 121.7, H = 7.96, p = 0.20) (see Table 8 ). Similarly, Table nine shows that attending three to five workshops was associated with a higher total professional competence level, with a mean rank of 121.05 (H = 12.11, p = 0.002). However, there were no significant differences in the total professional competency level or other professional competency subscale scores among other demographic and work environment factors (see Table 9 ). The reliability of the short version of the questionnaire in this study was excellent, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 97%.

This study aimed to assess the level of professional nursing competency of nurses who work at a tertiary hospital. Using the NPC Scale, the study’s findings shed light on the degree of self-reported professional competence among nurses working in a tertiary hospital in the West Bank. The results could be applied to raise the standard of patient care and healthcare services by pointing out areas that need improvement in the nursing clinical field, education, and training programs. This study contributes to the existing body of knowledge on the level of professional competence among nurses on the West Bank.

A total of 206 nurses participated in the study. Most of the respondents were male. The study showed no significant differences between males and females in terms of their level of professional competence; this was also noted in a study in which gender was not significantly related to professional competence [ 23 ]. In contrast, a study conducted on nurses’ competency in the Saudi Arabian healthcare context showed that male participants demonstrated superior self-reported competency assessment compared to female participants [ 24 ].

On the other hand, this study showed that years of experience do not affect the competency level, in contrast to a Japanese study in which the nursing competence levels are affected by the clinical experience. high competency level among newly hired nurses and junior nurses [ 25 ]. Also, a systematic review in Iran indicated that clinical experience of more than nine years affects the competency level [ 26 ].

The educational level of nurses in this study revealed no discernible relationship with their competence, and this is supported by the study of S-O Kim and Y-J Choi [ 27 ] contradicting the study of Z Nabizadeh-Gharghozar, NM Alavi and NM Ajorpaz [ 28 ] that correlates the educational level with competence level This discrepancy in results underscores the necessity for further exploration to understand the nuanced relationship between education levels and nursing competencies [ 29 ]. While a notable correlation emerged in this study between the number of workshops attended by nurses and their competence levels across all competency domains, a recent study in Japan showed that attending a two-day international outreach seminar provided participants with valuable and current knowledge regarding the competency of nurse educators. They developed a heightened awareness of the shifts in their self-efficacy as educators [ 30 ]. Additionally, Egyptian studies concluded that workshops had a beneficial impact on enhancing the knowledge, collaboration skills, and overall performance of both head and staff nurses [ 31 ].

According to our study, nurses exhibited a very good level of the total professional competency level. This result was supported by a study conducted in Iran which reported that nurses had a very good competency level [ 32 ]. Delving into the assessment of competency sub scores our study excelled in evaluating the competency of providing nursing care and helping patients was very good and the same with the result of a Turkish study that assessed the caring and helping competency level of 243 nurses in a university hospital [ 33 ],. Similarly, participants showed a very good competency level in handling technology and advanced medical machines, which affirms the growing integration of technology in nursing practice [ 34 ]. The “Care Pedagogics” competency underscores the crucial role of nurses in educating and supporting patients and their families, which is consistent with the findings of other related research [ 32 , 35 ] These results emphasize the ongoing need to prioritize clinical proficiency in nursing education and practice [ 17 ].