Premed Research That Impresses Medical Schools

Here are at least six research areas where you can leverage experiences to stand out on your medical school applications.

Research that Impresses Medical Schools

Getty Images

When writing about research on applications, describe not only what was done, but also write what was learned through research experiences.

One question premedical students frequently ask is, “Do I need to do research in order to be competitive for medical school ?”

My short answer: No.

It's not necessary for a medical school applicant to be involved in research , let alone publish a paper, in order to have a strong application. However, research only strengthens one’s application and never hurts it. Research doesn't guarantee acceptance to a medical school, and it's not necessary to gain acceptance.

However, I encourage premed students to conduct research at some point during their premed careers. Being involved in a research project trains premeds to think critically about an unresolved problem.

Research allows us to gain a better understanding of the unknown. Our current medical knowledge is built on clinical research . Drugs we prescribe patients underwent rigorous clinical trial studies, for example, and diagnostic work-up and treatment plans rely on evidence-based medicine based on research data.

Many premed students think that the research they conduct needs to be medical or scientific in nature. Another common misconception is that a strong premed must be involved with basic science research, often called bench research. While many premeds conduct medical-related research, these beliefs are not true. I have mentored amazing premed students with research ranging from Shakespearean play analysis to the creation of medical devices for individuals with disabilities.

6 Types of Medical Research

Here are six common health-related research directions I commonly see among premeds that reflect the breadth of research you can pursue:

- Basic science research

- Clinical research

- Public health research

- Health public policy research

- Narrative medicine research

- Artificial intelligence research

Basic Science Research

Basic science research, often called “bench research,” is the traditional research conducted in a laboratory setting. It tackles our fundamental understanding of biology .

Premeds involved with basic science research often study cells, viruses, bacteria and genetics. This research may also include animal and tissue specimens.

Examples: A premed student interested in cancer biology may study the cellular pathway of a specific tumor suppressor gene. Another premed student may probe how gut bacteria affect protein folding.

Clinical Research

Clinical research is the arm of medical research that tests the safety and effectiveness of diagnostic products, drugs and medical devices. It involves human subjects.

Examples: A premed interested in COVID-19 may conduct clinical trial research on new COVID-19 treatments. Another premed interested in dementia studies whether sleep improves depression among Alzheimer’s patients.

Public Health Research

Public health research studies the health of communities and populations in order to improve the health of the general public. Topics can range from vaccine access, disease prevention and disease transmission to substance abuse, social determinants of health and health education strategies.

Examples: A student interested in health equity may conduct public health research on how health insurance status and geography affect heart attack mortality. A premed excited about environmental science may look at the health impacts of wildfire smoke.

Health Public Policy Research

Premeds engaged in health policy research aim to understand how laws, regulations and policies can influence population health. Premeds may engage in both domestic and global policy research.

Examples: A premed interested in nutrition researches the effectiveness of nutrition programs in the Philippines. Another premed interested in economics studies health insurance markets in America.

Narrative Medicine Research

Narrative medicine research involves gathering stories from patients and their loved ones in order to understand the patient experience. As noted on the Association of American Colleges website , “Those stories can illuminate how a person became ill, the tipping point that compelled them to seek help, and, perhaps most importantly, the social challenges they face in getting better.”

Examples: A premed student interested in how Asians perceive disease can interview Asian patients about their attitudes toward herbal medications in cancer treatments. Another premed student interested in caregiver support can interviews caregivers of patients on prolonged mechanical ventilation to understand families’ decision-making processes.

Artificial Intelligence Research

Medical research utilizing artificial intelligence is increasingly popular, and premeds can analyze a large set of information to find medical discoveries. Premeds who conduct AI research typically have a skillset in computer science.

Examples: A premedical student interested in radiology may use AI to analyze hundreds of chest X-rays to create a program that better detects pneumonias. Another premed student may create and refine an algorithm using EKGs to better pick up abnormal heartbeats.

Remember that research not limited to these six categories. I've also met premeds engaged in journalistic research and business consulting research. As long as you have a research question and a scientific approach to analyze the question, then your pursuit can usually be considered research.

How Research Can Strengthen Medical School Applications

Research can strengthen your medical school application in several ways.

First, when a research project is related to a student’s interests, research involvement shows the application committee that the student is committed to advancing that field .

When writing about your research on applications, not only describe what you did, but also write what you learned through your research experiences. These lessons can include adaptability, analytical thinking and resilience.

Furthermore, you can discuss research through writing stories on secondary applications . For example, a common secondary essay prompt asks you to discuss a time when you failed or faced a challenge. You can write an essay about a challenging time you faced in your research and discuss how you overcame it. This will allow the admissions committee to gain insights into how you critically think through a problem.

Second, medical schools greatly favor independent research, in which students are leading the projects. In independent research, a premed forms a research question and a hypothesis. Then, the student gathers, analyzes and interprets data.

A student conducting independent research is in contrast to a student who helps another researcher with part of a project, or a student who follows protocols such as clinical trials recruitment, without thinking critically through the research design and analysis.

Third, becoming an author on a published paper can be a significant milestone and a valuable boost for a premed’s application. Of course, being a first author on a manuscript is an excellent feat, but it is not necessary for being seen as a strong student.

Other than publishing in academic journals, premedical students can showcase their research through poster presentations and talks. Presenting research conveys that you are excited about sharing your work and that you can explain your research to others, even those outside your field. These are all strong ways to indicate achievement and passion related to research.

The Value of Research for Premeds

Conducting premed research can provide firsthand insight into how much research you want to pursue throughout your career. After conducting research, some students may decide to get an M.D.-Ph.D. joint degree. Other students may come to the realization that their strengths lie elsewhere and conduct minimal research as doctors.

Through research, aspiring physicians will develop important skills that will help them in patient care. They will learn how to read and write research papers and evaluate treatment options by analyzing how robust the evidence is toward a specific treatment.

There are many advantages of engaging in research as a premed, only one of which is improving your medical school application. Since research is the cornerstone of medical advancement, research can help you become a more thoughtful doctor.

Medical School Application Mistakes

Tags: medical school , research , graduate schools , education , students

About Medical School Admissions Doctor

Need a guide through the murky medical school admissions process? Medical School Admissions Doctor offers a roundup of expert and student voices in the field to guide prospective students in their pursuit of a medical education. The blog is currently authored by Dr. Ali Loftizadeh, Dr. Azadeh Salek and Zach Grimmett at Admissions Helpers , a provider of medical school application services; Dr. Renee Marinelli at MedSchoolCoach , a premed and med school admissions consultancy; Dr. Rachel Rizal, co-founder and CEO of the Cracking Med School Admissions consultancy; Dr. Cassie Kosarec at Varsity Tutors , an advertiser with U.S. News & World Report; Dr. Kathleen Franco, a med school emeritus professor and psychiatrist; and Liana Meffert, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Iowa's Carver College of Medicine and a writer for Admissions Helpers. Got a question? Email [email protected] .

Popular Stories

Best Colleges

Morse Code: Inside the College Rankings

The Short List: Grad School

Law Admissions Lowdown

You May Also Like

Medical school rankings coming soon.

Robert Morse and Eric Brooks June 6, 2024

15 B-Schools With Low Acceptance Rates

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn June 5, 2024

Advice About Online J.D. Programs

Gabriel Kuris June 3, 2024

Questions to Ask Ahead of Law School

Cole Claybourn May 31, 2024

Tips for Secondary Med School Essays

Cole Claybourn May 30, 2024

Ways Women Can Thrive in B-School

Anayat Durrani May 29, 2024

Study Away or Abroad in Law School

Gabriel Kuris May 28, 2024

A Guide to Executive MBA Degrees

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn May 24, 2024

How to Choose a Civil Rights Law School

Anayat Durrani May 22, 2024

Avoid Procrastinating in Medical School

Kathleen Franco, M.D., M.S. May 21, 2024

Teaching Medical Research to Medical Students: a Systematic Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

- 2 Division of Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Surgery, Department of Surgery, National University Hospital, Singapore, Singapore.

- 3 Liver Transplantation, National University Centre for Organ Transplantation, National University Hospital, Singapore, Singapore.

- 4 Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

- 5 Division of Colorectal Surgery, Department of Surgery, National University Hospital, 1E Kent Ridge Road, Singapore, 119228 Singapore.

- PMID: 34457935

- PMCID: PMC8368360

- DOI: 10.1007/s40670-020-01183-w

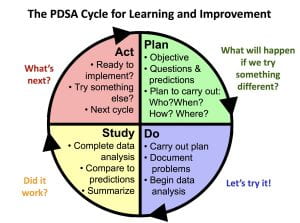

Phenomenon: Research literacy remains important for equipping clinicians with the analytical skills to tackle an ever-evolving medical landscape and maintain an evidence-based approach when treating patients. While the role of research in medical education has been justified and established, the nuances involving modes of instruction and relevant outcomes for students have yet to be analyzed. Institutions acknowledge an increasing need to dedicate time and resources towards educating medical undergraduates on research but have individually implemented different pedagogies over differing lengths of time.

Approach: While individual studies have evaluated the efficacy of these curricula, the evaluations of educational methods and curriculum design have not been reviewed systematically. This study thereby aims to perform a systematic review of studies incorporating research into the undergraduate medical curriculum, to provide insights on various pedagogies utilized to educate medical students on research.

Findings: Studies predominantly described two major components of research curricula-(1) imparting basic research skills and the (2) longitudinal application of research skills. Studies were assessed according to the 4-level Kirkpatrick model for evaluation. Programs that spanned minimally an academic year had the greatest proportion of level 3 outcomes (50%). One study observed a level 4 outcome by assessing the post-intervention effects on participants. Studies primarily highlighted a shortage of time (53%), resulting in inadequate coverage of content.

Insights: This study highlighted the value in long-term programs that support students in acquiring research skills, by providing appropriate mentors, resources, and guidance to facilitate their learning. The Dreyfus model of skill acquisition underscored the importance of tailoring educational interventions to allow students with varying experience to develop their skills. There is still room for further investigation of multiple factors such as duration of intervention, student voluntariness, and participants' prior research experience. Nevertheless, it stands that mentoring is a crucial aspect of curricula that has allowed studies to achieve level 3 Kirkpatrick outcomes and engender enduring changes in students.

Supplementary information: The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40670-020-01183-w.

Keywords: Curricula; Dreyfus model; Medical undergraduates; Research education; Skill acquisition.

© International Association of Medical Science Educators 2021.

Publication types

Why all medical students need to experience research

- Post author By Website Publications Officer

- Post date June 4, 2016

Medical students are very busy. The demands of studying medicine are extraordinary. Why then is it so important, on top of all there is to learn, to bother engaging in health and medical research? It is particularly important to consider this question at a time when, nationally and internationally, medical schools are including a research project as either a requirement of their program or a highly encouraged option. In fact, the Australian government is now supporting research by medical students with a specific category of scholarship funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) available to students undertaking in a combined MBBS/PhD or MD/PhD program. [1]

As a Dean of Medicine, and passionate advocate of health and medical research (HMR) in Australia, I support the inclusion of research in medical programs. Research training and experience are not just ‘nice to have’ but a ‘must’ for our doctors of the future. Increased research training in medical programs is beneficial for a student’s professional pathway, their evolving practice and, most importantly, for the health of the patients and communities they serve. [2,3]

Demonstrated research experience at medical school is increasingly important in obtaining positions in training programs post-graduation. [4] Recognition of the importance of HMR in developing and applying the skills and knowledge acquired in their medical studies has seen many of the specialist colleges including research training and productivity (for example publications) in their approach to selection of trainees. Competition for vocational and advanced training places is fierce, and a professional resume that includes research productivity and qualifications is and will continue to be important. Some colleges may even move to requiring a PhD for entry into advanced training.

A research experience may be the first time a student has had to write and record what they do, think, and find coherently, concisely and precisely. This can contribute to developing lasting habits of critical thinking. In a landmark and classic essay, C. Wright Mills commented that there was never a time he was not thinking, reflecting, analysing, and writing – he was always working on an idea. [5] This is the mindset that research can build up, and this is surely the mindset we want in clinical medicine and population health, where continuing critical appraisal of new evidence and engagement with new ideas is vital. In addition to stimulating ongoing interest in learning, this intellectually curious mindset contributes to a sense of personal satisfaction and eagerness to engage in discovery and learning as part of a team. [3,6] Research achievements are rarely made by individuals in isolation. Developing a mindset of critical inquiry in individuals and teams clearly encourages research productivity in grants and publications in the longer term, [3] which can ‘future-proof’ careers at a time when research performance is important in professional esteem and progression. Even more importantly, involvement in research appears to improve clinical practice. Research-active healthcare providers appear to provide better care and achieve better patient outcomes, [7] making the investment of time in research training for medical students potentially very important to building a healthier society in the long term. Given the potential benefits to early career clinicians and to patients, it is important to expose recent medical graduates to research as well, and successful postgraduate training programs are also taking steps to include research training. [3,8]

So, what is the best way for medical schools and postgraduate training programs to provide research training that maximises these benefits? It is clear from the literature that the most important thing is to have protected time to pursue research. Whether the research is a programmed experience as part of a course (as is increasingly the case), or something pursued independently by the individual student or trainee, giving as much time as possible is key to getting the best quality outcomes. For recent graduates, hospitals need to allow time to do research. [8] For students, time should be set aside within the program. [4] Students and trainees also need to be mentored by experienced researchers to get the best results. [3] Research experiences for students and trainees that combine mentorship and protected time can deliver the biggest benefits to our future clinical leaders and society as they are most likely to result in high quality outputs that are published and improve knowledge and practice. Where possible, trainees without research degrees should try to enrol in these at the same time as pursuing their research experiences, through a university that offers flexible research training and options to submit theses by publication, as earning a research degree such as a PhD is increasingly becoming a prerequisite for obtaining research funding that can support a clinical research career.

In summary, more than ever before, being a doctor in the 21st century is a career of lifelong learning. The combination of continued, rapid growth in knowledge and advancing technology bringing that information to your fingertips, have brought both a richness to the practice of medicine as well as a challenge. There is a growing appreciation that researchers make better clinicians. Research exposure increases understanding of clinical medicine; facilitates critical thinking and critical appraisal; improves prospects of successful application for post graduate training, grants, and high impact publications; develops teamwork skills; and increases exposure to the best clinical minds. The government is lifting its investment in health and medical researchers like never before. The establishment of the Medical Research Future Fund by the Australian Government, for example, offers the promise of continued durable investment in HMR and innovation, and the NHMRC’s substantial investment in research training scholarships for current students and recent graduates signals the Government’s commitment to developing clinician researchers for the future.

I encourage all students to make the most of research opportunities in medical school and beyond, not only for the personal and professional benefits, but in contributing to the health of their patients and to the Australian community.

[1] NHMRC Funding Rules 2015: Postgraduate Scholarships – 6 Categories of Award – 6.2. Clinical Postgraduate Scholarship. 2015. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/6-categories-award-3 (accessed Nov 2015).

[2] Laidlaw A, Aiton L, Struthers J, Guild S. Developing research skills in medical students: AMEE guide no. 69. Med Teach. 2012;34:754–71.

[3] Lawson PJ, Smith S, Mason MJ, Zyzanski SJ, Stange KC, Werner JJ, Flocke SA. Creating a culture of inquiry in family medicine. Fam Med. 2014;46(7):515–521.

[4] Collier AC. Medical school hotline: importance of research in medical education. Hawai’i Journal Med Public Health. 2012;71(2):53-6.

[5] Mills, CW. On intellectual craftsmanship. In: Seale, C. Editor. Social research methods: A reader. London: Routledge, 2004.

[6] von Strumm S, Hell B, Chamorro-Premuzic T. The hungry mind: intellectual curiosity is the third pillar of academic performance of university. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(6):574-88.

[7] Selby P, Autier P. The impact of the process of clinical research on health service outcomes. Ann Oncol 2011;22(Suppl 7):vii5-vii9.

[8] Chen JX, Kozin ED, Sethi RKV, Remenschneider AK, Emerick KS, Gray ST. Increased resident research over an 18-year period – a single institution’s experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(3):350-6.

Medical Research

How to conduct research as a medical student, this article will address how to conduct research as a medical student, including details on different types of research, how to go about constructing an idea and other practical advice., kevin seely, oms iv.

Student Doctor Seely attends the Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine.

In addition to good grades, test performance, and notable characteristics, it is becoming increasingly important for medical students to participate in and publish research. Residency programs appreciate seeing that applicants are interested in improving the treatment landscape of medicine through the scientific method.

Many medical students also recognize that research is important. However, not all schools emphasize student participation in research or have associations with research labs. These factors, among others, often leave students wanting to do research but unsure of how to begin. This article will address how to conduct research as a medical student, including details on different types of research, how to go about constructing an idea, and other practical advice.

Types of research commonly conducted by medical students

This is not a comprehensive list, but rather, a starting point.

Case reports and case series

Case reports are detailed reports of the clinical course of an individual patient. They usually describe an unusual or novel occurrence or provide new evidence related to a specific pathological entity and its treatment. Advantages of case reports include a relatively fast timeline and little to no need for funding. A disadvantage, though, is that these contribute the most basic and least powerful scientific evidence and provide researchers with minimal exposure to the scientific process.

Case series, on the other hand, look at multiple patients retrospectively. In addition, statistical calculations can be performed to achieve significant conclusions, rendering these studies great for medical students to complete to get a full educational experience.

Clinical research

Clinical research is the peak of evidence-based medical research. Standard study designs include case-controlled trials, cohort studies or survey-based research. Clinical research requires IRB review, strict protocols and large sample sizes, thus requiring dedicated time and often funding. These can serve as barriers for medical students wanting to conduct this type of research. Be aware that the AOA offers students funding for certain research projects; you can learn more here . This year’s application window has closed, but you can always plan ahead and apply for the next grant cycle.

The advantages of clinical research include making a significant contribution to the body of medical knowledge and obtaining an understanding of what it takes to conduct clinical research. Some students take a dedicated research year to gain experience in this area.

Review articles

A literature review is a collection and summarization of literature on an unresolved, controversial or novel topic. There are different categories of reviews, including meta-analyses, systematic reviews and traditional literature reviews, offering very high, high and modest evidentiary value, respectively. Advantages of review articles include the possibility of remote collaboration and developing expertise on the subject matter. Disadvantages can include the time needed to complete the review and the difficulty of publishing this type of research.

Forming an idea

Research can be inspiring and intellectually stimulating or somewhat painful and dull. It’s helpful to first find an area of medicine in which you are interested and willing to invest time and energy. Then, search for research opportunities in this area. Doing so will make the research process more exciting and will motivate you to perform your best work. It will also demonstrate your commitment to your field of interest.

Think carefully before saying yes to studies that are too far outside your interests. Having completed research on a topic about which you are passionate will make it easier to recount your experience with enthusiasm and understanding in interviews. One way to refine your idea is by reading a recent literature review on your topic, which typically identifies gaps in current knowledge that need further investigation.

Finding a mentor

As medical students, we cannot be the primary investigator on certain types of research studies. So, you will need a mentor such as a DO, MD or PhD. If a professor approaches you about a research study, say yes if it’s something you can commit to and find interesting.

More commonly, however, students will need to approach a professor about starting a project. Asking a professor if they have research you can join is helpful, but approaching them with a well-thought-out idea is far better. Select a mentor whose area of interest aligns with that of your project. If they seem to think your idea has potential, ask them to mentor you. If they do not like your idea, it might open up an intellectual exchange that will refine your thinking. If you proceed with your idea, show initiative by completing the tasks they give you quickly, demonstrating that you are committed to the project.

Writing and publishing

Writing and publishing are essential components of the scientific process. Citation managers such as Zotero, Mendeley, and Connected Papers are free resources for keeping track of literature. Write using current scientific writing standards. If you are targeting a particular journal, you can look up their guidelines for writing and referencing. Writing is a team effort.

When it comes time to publish your work, consult with your mentor about publication. They may or may not be aware of an appropriate journal. If they’re not, Jane , the journal/author name estimator, is a free resource to start narrowing down your journal search. Beware of predatory publishing practices and aim to submit to verifiable publications indexed on vetted databases such as PubMed.

One great option for the osteopathic profession is the AOA’s Journal of Osteopathic Medicine (JOM). Learn more about submitting to JOM here .

My experience

As a second-year osteopathic medical student interested in surgery, my goal is to apply to residency with a solid research foundation. I genuinely enjoy research, and I am a member of my institution’s physician-scientist co-curricular track. With the help of amazing mentors and co-authors, I have been able to publish a literature review and a case-series study in medical school. I currently have some additional projects in the pipeline as well.

My board exams are fast approaching, so I will soon have to adjust the time I am currently committing to research. Once boards are done, though, you can bet I will be back on the research grind! I am so happy to be on this journey with all my peers and colleagues in medicine. Research is a great way to advance our profession and improve patient care.

Keys to success

Research is a team effort. Strive to be a team player who communicates often and goes above and beyond to make the project a success. Be a finisher. Avoid joining a project if you are not fully committed, and employ resiliency to overcome failure along the way. Treat research not as a passive process, but as an active use of your intellectual capability. Push yourself to problem-solve and discover. You never know how big of an impact you might make.

Disclaimers:

Human subject-based research always requires authorization and institutional review before beginning. Be sure to follow your institution’s rules before engaging in any type of research.

This column was written from the perspective from a current medical student with the review and input from my COM’s director of research and scholarly activity, Amanda Brooks, PhD.

Related reading:

H ow to find a mentor in medical school

Tips on surviving—and thriving—during your first year of medical school

Mile marker

20 reasons to love and hate retirement, road to residency, how to soften red flags on your eras application, ai and medicine, how dos can be at the forefront of the digital health revolution, emergency preparedness, high-altitude health care: navigating in-flight medical emergencies, creating change, do day 2024: advocating for student loan reform, health care worker safety and more, more in training.

AOA works to advance understanding of student parity issues

AOA leaders discuss student parity issues with ACGME, medical licensing board staff and GME program staff.

PCOM hosts annual Research Day showcasing scholarly activity across the college’s 3 campuses

Event highlighted research on important topics such as gun violence and COPD.

Previous article

Next article, one comment.

Thanks! Your write out is educative.

Leave a comment Cancel reply Please see our comment policy

- Premed Research

How Important is Research for Medical School

How important is research for medical school? Research is a critical part of your medical learning, and its important for both how to prepare for med school applications and of course your entire medical career. Research experience of any type is a valuable asset on medical school applications, and clinical research experience even more so. If you’ve completed a stint in a clinical research position, these can count towards how many clinical hours you need for medical school . Some of the most competitive or research-focused medical colleges even require students to have prior research experience to be accepted. Not every med school asks for research experience, but every medical student will need some research experience under their belts by the time they graduate. In this blog, we’ll look at how important research is for medical school, what research experience can do for you and where to look to find medical research opportunities.

>> Want us to help you get accepted? Schedule a free strategy call here . <<

Article Contents 6 min read

How important is research for medical school.

There are two sides to this question. The first is whether research experience is important for medical school applications. The second is whether gaining research experience is an important part of attending medical school. The answer to both of these is undoubtedly yes, research is very important for medical school.

Of course, there are some qualifications to this importance. Having research experience is not a hard requirement for the vast majority of medical school applications and students can still be accepted without pre-med research experience. For highly competitive medical schools, such as Stanford Medical School , or medical schools with a heavy focus on research, it may not only be a requirement but a huge asset and a way for you to ensure your medical school application stands out . For a majority of competitive, research-heavy medical colleges, up to 90% of matriculating students have prior research experience.

Check out our video for more advice on how to find premed research experience

It’s a good idea to check Medical School Admission Requirements ( MSAR ) to see if your choice of med school requires applicants to have any research experience, and if the admissions board has any preference for what type of research experience. A majority of schools will gladly accept students with research experience, but your priority should be on crafting an excellent med school app first and foremost. If you have a strong application and you have the time, you can consider looking for pre-med research opportunities to add to your application as a bonus.

But even if your choice of med school doesn’t require research experience, it is still extremely important to your journey as a med student and your future career as a doctor. If you are planning to apply to a very competitive medical school program, intend to pursue an MD/PhD program or are applying to a research-intensive medical college, research experience is an absolute must. And if none of these apply to you, eventually you will want to add research experience to your medical school resume, too.

First, let’s look at what research experience can do or your medical school applications.

Research experience for medical school applications

Research experience might be a necessary requirement for many med school applications, depending on the school and the program, but the type of research experience can vary significantly. For most med schools, they aren’t choosy about the type of research you have experience in, even if it’s not directly related to the medical field. Having any kind of research position in a scientific discipline will lend you invaluable experience and skills that will transfer to your time at med school.

But something that can help you stand out, and which medical schools value more heavily is clinical research experience. To gain clinical research as a premed might not always be possible for all students. Many try to find virtual research for premed students or look into virtual shadowing opportunities. But straight research experience and even shadowing experience is not considered actual clinical experience, and if you have any direct clinical experience on your med school application, it is considered an asset no matter where you apply.

Even if your choice of med school isn’t bothered by a lack of premed research experience or you don’t plan to pursue a career in medical research, this doesn’t mean you’re off the hook. Research is still an important aspect of medical school and being a practicing physician. Research experience provides you with pivotal skills you’ll employ as a doctor, but it can also broaden and deepen your medical knowledge and medical skills. Doctors rely on research to inform them and broaden their understanding of the medical field. And plenty of clinical physicians take the time to do their own research or publish research as a way to further their careers and open up new opportunities. Research experience also serves as a way to make your medical school resume stand out when you’re applying for jobs in residency and beyond. It might even be a requirement if you want to apply for research training positions or specialty medical research jobs.

For medical students in particular, they will be expected to undertake research projects and will be provided dedicated, protected research time to not only conduct their own individual or team research but to read the work of other researchers, too. Not all of your research experiences need to come directly through school, either. You can and are encouraged to pursue research opportunities outside med school as well. Any experiences you can add to your portfolio will be to your benefit. In short, research is a foundational part of the med school experience and in developing your skills as a medical professional.

So how can research experience help you in medical school? What advantages and benefits can it bring you? We’ll take a closer look at how important research is for medical school students and how it can be a long-term advantage in their careers.

In the vein of critically evaluating research work, conducting research will naturally develop your critical thinking and analysis skills. Throughout med school you will be asked to participate in, read about and conduct research, as doing so is part of the foundation of your medical knowledge. Research experience can also be influential in developing other important medical skills, too, such as better communication, teamwork and writing skills. It\u2019s also been shown through research that doctors who continue to learn about medicine and study medical research provide better care to patients overall. If nothing else, making a habit of regular research and study will keep you fresh and up to date on the medical field and its latest developments. "}]">

How to find medical research opportunities

Students who do want to attach some research experience to their applications or resumes often wonder where to start looking. Whether you’re a premed, current med school student or graduate student, gaining some research experience is important for your career. There are a number of places to look for opportunities, but the best ways are to use your network of contacts and ask them for recommendations. There are many programs, internships and study programs which offer research experience of any kind, and your school professors, mentors and advisors will have more insight into where to find them.

Research is a critical and eventual must-have skill and experience for medical school. Whether you add some research experience as a premed, med student or medical graduate depends on where you want to go to school and what your chosen career path as a medical professional will end up being. While you will almost certainly be given some research opportunities in medical school, it’s to your advantage to pursue some outside of your studies as well, to give yourself a competitive advantage in the job market, to continue your lifelong medical learning and to ensure you become the best doctor you can be for your future patients.

Research can a big advantage on both medical school applications and on medical school resumes for graduate medical students. Research experience is also very important to gain during your time at medical school, as it is a foundational skill you will need to become a physician.

Yes; research experience is not a definite requirement at most med schools and students without experience can still be accepted with a strong application. However, good research experience should not be considered a substitute for poor academic performance.

A majority of medical schools don’t require research experience for med school applications, with some exceptions. However, as a matriculating med school student you will be expected to gain research experience and participate in research projects during your school years.

Premed students can find valuable research positions through summer internship programs or by consulting with a college advisor. Professors and mentors are also a good option for finding research opportunities. Premeds can also look into study abroad programs that offer research experience.

No; most medical schools consider direct clinical experience more important than lab or field research for admissions. However, if you plan to apply for medical research positions, to a research-intensive med school program or want to pursue an MD/PhD, then research experience will be considered more important to have.

Research is part of the foundational skills med students will learn and will take with them into their future careers. Research experience can also provide a competitive advantage in the job market and prepare them for residency positions or work as a practicing physician.

Even if this is the case, research is a large part of being a physician and you will be required to gain at least a little experience with medical research throughout your med school career.

Generally speaking, no. Medical schools aren’t picky about the type of research experience you have, or even if the subject of the research undertaken was non-medical. Any research experience is valid.

Want more free tips? Subscribe to our channels for more free and useful content!

Apple Podcasts

Like our blog? Write for us ! >>

Have a question ask our admissions experts below and we'll answer your questions, get started now.

Talk to one of our admissions experts

Our site uses cookies. By using our website, you agree with our cookie policy .

FREE Premeds Research Webclass :

How to Get the Perfect Premed Research Experience

That Helped Me Get Accepted to SIX Med Schools

Time Sensitive. Limited Spots Available:

Would you like a Premed Research experience that admissions committees love?

Swipe up to see a great offer!

Comprehensive Guide to Research from the Perspective of a Medical Student

- By Dmitry Zavlin, M.D.

- February 9, 2017

- Medical Student , Pre-med

G uest post from Dmitry Zavlin, MD, a research fellow in Houston, Texas. He has been highly productive in his research endeavors and below describes a comprehensive guide to getting involved in research.

Without any doubt whatsoever, high USMLE scores, strong recommendation letters from faculty members, a multitude of away rotations, and an updated and accurate résumé make up the foundation of a strong application for a residency position. Nevertheless, from my personal experience, one topic remains crucial that many medical students either love or hate (or try not to think about it): research . It is an extracurricular activity that enables someone to stand out from the crowd and present oneself as a diverse and multitasking character. These traits are especially favorable when it comes to applying to competitive residency programs with high applicant to position ratios. I encourage every future graduate to look into this topic since – and as astonishing as this may seem – medical school is the ideal opportunity to get your name out there. You don’t need to take a year off from classes or be on an M.D., Ph.D. track. Even those students that do not seek academic careers have a benefit from engaging in scientific duties . It helps you understand the mechanisms of research, the bureaucratic obstacles, the medical challenges, and teaches you communication with peers and faculty. Furthermore, you learn how to read, analyze, and interpret scientific publications of others. And trust me, it’s not all gold that gets printed in journals . On first glance, getting involved in unpaid ventures while you are in class, on rotation, at home studying or just taking some time off for yourself might seem like a bad deal. Yet with a sincere approach towards this subject, you can strengthen your résumé, top off your application, and learn skills that will serve you well into your career as a doctor.

The following lines are intended to display my personal experience that I have made at my medical school and in my interactions with students, residents, fellows, and attendings at my current position.

Choosing your Project

First things first. Naturally, you would want to participate and conduct research in a field of medicine you might see yourself in after graduation. However, as mentioned before, this is not a K.O. criterion. Plenty of personal experiences tell me stories of students who were involved in one area and then switched and matched in a completely different specialty of medicine or completely left the patient-care sector. Therefore, consider your engagement in scientific tasks more of as a symbolization for your work ethic and your ability to perform in a team.

My first tip is to contact the department at your home medical school, introduce yourself, write 1-2 sentences describing your motivations and goals, and ask to sit down with some faculty members or scientific staff to discuss your involvement in any research activities.

Larger departments usually have secretaries or an academic office where your email is less likely to get lost compared to the inbox of a busy professor who receives hundreds of emails per day. Personally, I would aim for junior faculty and potentially senior residents who are experienced enough to conduct research on a high level but are not too far away from the life of a young medical student. Certain departments further have specific full-time research staff that is definitely a great resource for any scientific venture. While it may be helpful to work with the director and senior faculty directly, the sad reality is often that they typically have many academic and administrative duties and activities at their institutions that might not go along well with the schedule of an ambitious student and cause frustration in the long run.

When you meet, make sure to gain and write down as many details as possible:

- What is the topic, what is the goal of this project?

- What type of format is it? (See below)

- What is the current status?

- Who is involved in this research project, what is the team, what are the people to contact?

- What will be my duties?

- Any bureaucratic issues to be aware of (IRB approval, grants, finances)?

- What is the prognosis? Are there any deadlines?

Lastly, ask about the current literature on that topic so you know what your team’s role is going to be in this scientific field. Although one core concept of any research result is reproducibility, it often remains a challenge to publish a project that has already been performed and presented or printed before. Getting involved in an area that is in quick development with high turnaround is subsequently a strong recommendation.

Types of Evidence-Based Research

Now, I would like to talk about the most common options you will encounter when presented with an array of project offers. That way you know their perks and pitfalls before you commit to anything serious and long-lasting and potentially even waste any valuable and limited time of yours.

- Case Reports: These are the most basic and least powerful of scientific contributions to medicine. Give or take, a case report is the summarized hospital or clinic chart of a treated patient who presented with a problem A and was managed with therapy B. A case report that is typically 2-3 pages long with a short intro, a compact case discussion, and perhaps some photos is the closest thing you will get to a patient note you learned to write in early medical school. Their lack of medical value makes them hard to get published in journals and students should not solely rely on these projects as they may not ultimately be accepted by journals. Recommendation: 3/5

- Case Series, Retrospective Study: These layouts are my personal recommendation as they allow quality results within a short period and are not time-consuming or require large long-term commitment as others. Typical examples are an analysis of patients who presented with the same diagnosis or underwent an identical procedure. The difference between a case series and a retrospective study is that for the latter, the patients can be stratified into different subgroups (similar to “case control study”) and statistical calculations can be performed to achieve significant conclusions. Recommendation: 5/5

- Prospective Studies: In these studies, patients are gathered in one or multiple cohorts and are followed-up over long periods of time by lab results, imaging, physical exams etc. These require great time commitment and, from a student perspective, typically only allow a certain amount of participation. These are usually studies for physicians with long relationships with their patients. Recommendation: 3/5

- (Randomized) Clinical Trials : The peak of evidence-based medical research. Similar as prospective studies yet require more planning, IRB approval, and lots of work with industry, grants, protocols, etc. Student involvement is usually marginal. Recommendation: 2/5

- Basic Science, Animal Work: Although these projects require training, approval, and a large amount of preparation, student participation is common in many areas of basic science. The advantage of these laboratory activities is a certain amount of flexibility on when certain tasks and duties can be performed. Within certain limitations, a medical student can get involved in animal or basic science research and assist in specific jobs suitable to his or her personal schedule. Even partial involvement can be enough to get one’s name on a publication. However, lab work can be monotonous and frustrating at times when experiments do not deliver the anticipated results. Sitting in non-stimulation laboratories requires a certain type of character. Recommendation: 4/5

- Descriptions of Innovations: Purely descriptive publications of new surgical techniques, innovative technology, new pharmaceutical drugs, or simply personal statements on evolving subjects, etc. This type of work often demands a given level of expertise and is not typically suitable for graduate research. Recommendation: 2/5

- Reviews, Meta-Analyses: These types of written compositions are based on a literature review. The author’s job is to read through countless, often hundreds of previous publications and create a summary regarding a specific medical topic. Reviews and meta-analysis are particularly useful for issues that are prevalent and have delivered many reports in the past. Whereas a review merely lists the findings of previous research groups, a meta-analysis is able to pool data and conduct statistical analyses. These projects allow great flexibility and can be finished from any location but do not underestimate the time needed to achieve proper results. Recommendation: 4/5

Formats of Publication

What follows is a list of mediums that allow you to get your work to the public. Albeit the concept of most research activities is similar and progresses on akin paths, it is important to agree on a goal early in the research process. Journal articles, for example need to be of highest quality and impeccable when submitted. Presentations must be tailored accordingly depending on what audience you are planning to address. Book chapters need clear guidelines to ensure that your handiwork fits well to the other parts of the volume. Make sure to discuss this topic with your seniors to understand their expectations from you.

- Journal Articles: These are the highest quality format that you can use to submit your research work for the world to see. Upon arrival at the journal’s office, the editorial office first reviews your manuscript and determines its eligibility. Next, it is sent off to a number of anonymous reviewers who judge your documents and suggest if it is worth publication, if it needs changes, or if it should be rejected. Being an author on articles in peer-reviewed journal is the strongest support to improve your application. Recommendation: 5/5

- Podium Presentations: These are typically 5-15min PowerPoint conferences or similar in front of regional, national, and international audiences of students, residents, nurses, scientists, and board-certified physicians. While your work might be less accessible to the world than published articles, it is still recommended to submit your accomplishments to such conventions. Aim for national conferences rather than regional ones. Recommendation: 4/5 for (inter)national, 3/5 for regional conferences

- Poster Presentations: A classic poster session is where you travel to a conference, hang your poster with a summary of your research findings (similar to a short abstract) and are available for others to review your work and ask questions. In some cases, poster sessions are requested by conferences when you apply for podium presentations but your projects are not considered beneficial enough. Recommendation: 3/5

- Book Chapters: Senior physicians, faculty members, or experts on a certain field are sometimes asked to write segments of medical or scientific books that are soon to be brought on sale to the market. In certain cases, students or residents write segments of such book chapters for the senior author. From personal experience, these projects are a long-term process as they go into extreme medical detail. On the upside, publication with your name on it is almost guaranteed. Unfortunately, these types of publications are not of high evidence-based research and should only be considered as a secondary side project Recommendation: 3/5

Basic and Necessary Know-How

After choosing your project you need to learn and understand how the scientific process works once you have your results ready for publication. Conducting the studies, experiments, and the literature reviews is one part of the research job. Presenting your findings is the other side of the coin. Read many publications on the same subject and study what a paper is supposed to look like. Analyze the language the authors use. It has to be straight to the point, factual, objective, leave out unnecessary information yet avoid long soporific segments of repeating details. Your audience will want to hear a hypothesis, the methodology of your venture on how said hypothesis should be tested, your results, and an antiseptic interpretation thereof. Having a senior writer review your work is therefore crucial in the beginnings of a research career.

Next, and this may seem like a no-brainer, learn how to properly and efficiently use today’s available technology to your advantage. Learn the most important features of your word processing software. Get access to a tool that allows to sort and list literature references and full versions of articles, preferably in PDF format. If you share files with others or work simultaneously at different sites, use a cloud service to keep your files in synchronization across all your devices. Any photo, video, or graph-editing software with some artistic skills might come in handy as well. Lastly, learn some basic mathematical and statistical skills and obtain a statistical software. Research is nothing if you cannot back up your story by some hard numbers. Study what a t-test, a type I error, and a type II error are and how they work. Understand when you have to use chi-square and when the Fisher’s exact test . This list goes on and on. You do not need a Ph.D. degree in biometrics or stochastic calculus to be involved in medical research but even basic skills can set you far ahead of others and you will stand out from the crowd. Additionally, all these things I just mentioned facilitate your projects by incredible amounts and allow you to publish your results faster. Capitalize on the technology that is available today!

Finally, learn how to revise current literature and how to look for references to back up your ideas or contrast your data to those of other groups. In the end, research is a competition almost like any other business sector; except that money is not necessarily the number one objective but rather prestige and impact. Pubmed is a valuable search engine, for instance, that allows you to go through the MEDLINE database and find similar publications to your project. UpToDate is a practical tool that is constantly refreshed by countless experts and gives access to the latest guidelines on specific topics. One of my former attendings always said that publishing a paper is like selling a car: you have to know the market and emphasize the upsides of your work to gain interest of others. Have all these files clean and tide on your computer from day 1, so you can keep a good overview of things and track your progress.

Further Aspects to Consider

When you start a new research project, figure out who your team is that you will be working with as this will determine the authors and their order on a potential publication. Make sure your name appears on the final manuscript if you have brought significant effort and input towards the project. As the New England Journal of Medicine, one of the largest and most prestigious journals in the field, states:

“Credit for authorship requires (a) substantial contributions to the conception and design; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data, (b) the drafting of the article or critical revision for important intellectual content, (c) final approval of the version to be published, and (d) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the article are appropriately investigated and resolved.”

The more work you put in, the further your name should appear up front. The final position of a scientific publication is usually reserved for the senior author (principal investigator) and the head of the team.

The last issue that needs to be mentioned here are finances. Even if you are working on a retrospective study and are just simply scrolling through patient charts to gather data, special software, travel to conferences, fees for journals (author processing charge for open access) can rapidly add up. Basic science ventures may require additional funding. Knowing your resources is crucial for any research. The discussion of money may seem like a sensitive subject and “above your pay grade” yet I recommend approaching this topic with open cards when the right moment comes.

Final Words

Despite the downsides of scientific work, I still believe the majority of students should experience the art of research that has made medicine what it is now. Yes, research is frequently frustrating and consumes many of your physical and mental resources. Yes, a majority of jobs after residency do not include research. Still, I will never forget the great feeling of my first accepted publication and when I immediately continued to strive towards the next challenge. Henceforward, research had something rewarding and appealing about it. In the long run, this highly dynamic profession is probably not suited for all future physicians, yet I can only repeat myself and encourage everyone to give it a try.

Dmitry Zavlin graduated with an M.D. from the Technical University of Munich in 2015.

He currently works as a research fellow in Houston.

To contact the author, please visit www.zavlin.com

Dmitry Zavlin, M.D.

First Day of Medical School – 4 Things to Know

Medical school is a completely different beast from your pre-med years in college. Here are four things you should know and prepare for in order to have the most productive, effective, and happy experience of medical school!

Premed and Medical Student Summer Research Guide

We break down the value of summer research, how to find research positions, and tips to make the most of summer research opportunities.

How to Find an Undergraduate Research Position

Research is a crucial component of any medical school application. Utilize the following tips to streamline the process of finding an ideal research position.

This Post Has One Comment

Awesome summary, really helpful for me as a med student!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Join the Insider Newsletter

Receive regular exclusive MSI content, news, and updates! No spam. One-click unsubscribe.

Customer Note Premed Preclinical Med Student Clinical Med Student

You have Successfully Subscribed!

A Realistic Guide to Medical School

Written by UCL students for students

Top 10 Tips: Getting into Research as a Medical Student

Introducing our new series: Top 10 Tips – a simple guide to help you achieve your goals!

In this blog post, Jessica Xie (final year UCL medical student) shares advice on getting into research as a medical student.

Disclaimers:

- Research is not a mandatory for career progression, nor is it required to demonstrate your interest in medicine.

- You can dip into and out of research throughout your medical career. Do not feel that you must continue to take on new projects once you have started; saying “no, thank you” to project opportunities will allow you to focus your energy and time on things in life that you are more passionate about for a more rewarding experience.

- Do not take on more work than you are capable of managing. Studying medicine is already a full-time job! It’s physically and mentally draining. Any research that you get involved with is an extracurricular interest.

I decided to write this post because, as a pre-clinical medical student, I thought that research only involved wet lab work (i.e pipetting substances into test tubes). However, upon undertaking an intercalated Bachelor of Science (iBSc) in Primary Health Care, I discovered that there are so many different types of research! And academic medicine became a whole lot more exciting…

Here are my Top 10 Tips on what to do if you’re a little unsure about what research is and how to get into it:

TIP 1: DO YOUR RESEARCH (before getting into research)

There are three questions that I think you should ask yourself:

- What are my research interests?

Examples include a clinical specialty, medical education, public health, global health, technology… the list is endless. Not sure? That’s okay too! The great thing about research is that it allows deeper exploration of an area of Medicine (or an entirely different field) to allow you to see if it interests you.

2. What type of research project do I want to do?

Research evaluates practice or compares alternative practices to contribute to, lend further support to or fill in a gap in the existing literature.

There are many different types of research – something that I didn’t fully grasp until my iBSc year. There is primary research, which involves data collection, and secondary research, which involves using existing data to conduct further research or draw comparisons between the data (e.g. a meta-analysis of randomised control trials). Studies are either observational (non-interventional) (e.g. case-control, cross-sectional) or interventional (e.g. randomised control trial).

An audit is a way of finding out if current practice is best practice and follows guidelines. It identifies areas of clinical practice could be improved.

Another important thing to consider is: how much time do I have? Developing the skills required to lead a project from writing the study protocol to submitting a manuscript for publication can take months or even years. Whereas, contributing to a pre-planned or existing project by collecting or analysing data is less time-consuming. I’ll explain how you can find such projects below.

3. What do I want to gain from this experience?

Do you want to gain a specific skill? Mentorship? An overview of academic publishing? Or perhaps to build a research network?

After conducting a qualitative interview study for my iBSc project, I applied for an internship because I wanted to gain quantitative research skills. I ended up leading a cross-sectional questionnaire study that combined my two research interests: medical education and nutrition. I sought mentorship from an experienced statistician, who taught me how to use SPSS statistics to analyse and present the data.

Aside from specific research skills, don’t forget that you will develop valuable transferable skills along the way, including time-management, organisation, communication and academic writing!

TIP 2: BE PROACTIVE

Clinicians and lecturers are often very happy for medical students to contribute to their research projects. After a particularly interesting lecture/ tutorial, ward round or clinic, ask the tutor or doctors if they have any projects that you could help them with!

TIP 3: NETWORKING = MAKING YOUR OWN LUCK

Sometimes the key to getting to places is not what you know, but who you know. We can learn a lot from talking to peers and senior colleagues. Attending hospital grand rounds and conferences are a great way to meet people who share common interests with you but different experiences. I once attended a conference in Manchester where I didn’t know anybody. I befriended a GP, who then gave me tips on how to improve my poster presentation. He shared with me his experience of the National institute of Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Academic Training Pathway and motivated me to continue contributing to medical education alongside my studies.

TIP 4: UTILISE SOCIAL MEDIA

Research opportunities, talks and workshops are advertised on social media in abundance. Here are some examples:

Search “medical student research” or “medsoc research” into Facebook and lots of groups and pages will pop up, including UCL MedSoc Research and Academic Medicine (there is a Research Mentoring Scheme Mentee Scheme), NSAMR – National Student Association of Medical Research and International Opportunities for Medical Students .

Search #MedTwitter and #AcademicTwitter to keep up to date with ground-breaking research. The memes are pretty good too.

Opportunities are harder to come by on LinkedIn, since fewer medical professionals use this platform. However, you can look at peoples’ resumes as a source of inspiration. This is useful to understand the experiences that they have had in order to get to where they are today. You could always reach out to people and companies/ organisations for more information and advice.

TIP 5: JOIN A PRE-PLANNED RESEARCH PROJECT

Researchers advertise research opportunities on websites and via societies and organisations such as https://www.remarxs.com and http://acamedics.org/Default.aspx .

TIP 6: JOIN A RESEARCH COLLABORATIVE

Research collaboratives are multiprofessional groups that work towards a common research goal. These projects can result in publications and conference presentations. However, more importantly, this is a chance to establish excellent working relationships with like-minded individuals.

Watch out for opportunities posted on Student Training and Research Collaborative .

Interested in academic surgery? Consider joining StarSurg , BURST Urology , Project Cutting Edge or Academic Surgical Collaborative .

Got a thing for global health? Consider joining Polygeia .

TIP 7: THE iBSc YEAR: A STEPPING STONE INTO RESEARCH

At UCL you will complete an iBSc in third year. This is often students’ first taste of being involved in research and practicing academic writing – it was for me. The first-ever project that I was involved in was coding data for a systematic review. One of the Clinical Teaching Fellows ended the tutorial by asking if any students would be interested in helping with a research project. I didn’t really know much about research at that point and was curious to learn, so I offered to help. Although no outputs were generated from that project, I gained an understanding of how to conduct a systematic review, why the work that I was contributing to was important, and I learnt a thing or two about neonatal conditions.

TIP 8: VENTURE INTO ACADEMIC PUBLISHING

One of the best ways to get a flavour of research is to become involved in academic publishing. There are several ways in which you could do this:

Become a peer reviewer. This role involves reading manuscripts (papers) that have been submitted to journals and providing feedback and constructive criticism. Most journals will provide you with training or a guide to follow when you write your review. This will help you develop skills in critical appraisal and how to write an academic paper or poster. Here are a few journals which you can apply to:

- https://thebsdj.cardiffuniversitypress.org

- Journal of the National Student Association of Medical Researchjournal.nsamr.ac.uk

- https://cambridgemedicine.org/about

- https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-reviewers

Join a journal editorial board/ committee. This is a great opportunity to gain insight into how a medical journal is run and learn how to get published. The roles available depend on the journal, from Editor-in-Chief to finance and operations and marketing. I am currently undertaking a Social Media Fellowship at BJGP Open, and I came across the opportunity on Twitter! Here are a few examples of positions to apply for:

- Journal of the National Student Association of Medical Researchjournal.nsamr.ac.uk – various positions in journalism, education and website management

- https://nsamr.ac.uk – apply for a position on the executive committee or as a local ambassador

- Student BMJ Clegg Scholarship

- BJGP Open Fellowships

TIP 9: GAIN EXPERIENCE IN QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

UCL Be the Change is a student-led initiative that allows students to lead and contribute to bespoke QIPs. You will develop these skills further when you conduct QIPs as part of your year 6 GP placement and as a foundation year doctor.

TIP 10: CONSIDER BECOMING A STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE

You’ll gain insight into undergraduate medical education as your role will involve gathering students’ feedback on teaching, identifying areas of curriculum that could be improved and working with the faculty and other student representatives to come up with solutions.

It may not seem like there are any research opportunities up for grabs, but that’s where lateral thinking comes into play: the discussions that you have with your peers and staff could be a source of inspiration for a potential medical education research project. For example, I identified that, although we have lectures in nutrition science and public health nutrition, there was limited clinically-relevant nutrition teaching on the curriculum. I then conducted a learning needs assessment and contributed to developing the novel Nutrition in General Practice Day course in year 5.

Thanks for reaching the end of this post! I hope my Top 10 Tips are useful. Remember, research experience isn’t essential to become a great doctor, but rather an opportunity to explore a topic of interest further.

One thought on “Top 10 Tips: Getting into Research as a Medical Student”

This article was extremely helpful! Alothough, I’m only a junior in high school I have a few questions. First, is there anyway to prepare myself mentally for this challenging road to becoming a doctor? check our PACIFIC best medical college in Rajasthan

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Copyright © 2018 UCL

- Freedom of Information

- Accessibility

- Privacy and Cookies

- Slavery statement

- Reflect policy

Please check your email to activate your account.

« Go back Accept

Sign up to our Newsletter

Research for medical school admissions: what do you need to know.

Reviewed by:

Jonathan Preminger

Former Admissions Committee Member, Hofstra-Northwell School of Medicine

Reviewed: 4/25/24

There are several ways in which you can make your application for medical school more attractive to the eyes of admissions committees.

While research experience is not a requirement for most schools, having a research background that is sound, aligns with your major and interests, is fundamentally strong, and overall complements your application’s theme is a perfect way to be a competitive candidate and enhance your possibilities of getting into medical school.

This guide will teach you all that you need to know about research for medical school, ensuring you’ll gain successful and meaningful experiences.

Get The Ultimate Guide on Writing an Unforgettable Personal Statement

Importance of Research for Medical School

Your MCAT , GPA, extracurriculars, and clinical experience all play a role in your admissions chances. But research is also key! Most but not all students accepted to medical school have research experience.

According to a survey of incoming medical students conducted by the AAMC , 60% of students participated in some kind of laboratory research for college students. Experts in the field have made their ideas about it very clear; Dr. Petrella, a Stanford University Ph.D. and mentor, states:

“Our belief is that an exercise science curriculum provides students the opportunity to become responsible professionals of competence and integrity in the area of health and human performance.”

Today, we’ll talk about how to prepare for and strategically use research to enhance your application and make it more interesting and rich in the eyes of the admissions committee. But first, take a quick look at why you should gain research experience in your undergraduate career.

What Counts as Research for Medical School?

While most research is good research, some things should be taken into consideration before jumping into the next opportunity available:

- Clinical research is great but research in the humanities or social sciences also counts

- Good research experience develops your writing skills, critical thinking skills, professionalism, integrity, and ability to analyze data

- It’s important to contribute to the research for a long period of time—several months rather than a couple weeks

- You can participate in research part-time or full-time; both count

- You should get involved in research related to your major, desired career, and interests

- Be committed and deeply involved in the research—you’ll be asked about it in interviews!

- Being published as a top contributor of any related research papers looks the best

Overall, there isn’t really “bad” research experience, so long as you’re committed, make clear contributions, and are genuinely passionate about the subject!

How to Gain Research Experience as a Pre Med

There are several ways to become involved in research and find research opportunities during your undergraduate years. Research opportunities will be available through the university you’re attending, so make sure to maintain a good relationship and communication with your professors.

One of the best ways to secure a research position is to have a conversation with your professors. They may be looking for a student to help them with an upcoming project, and even if they don’t have any opportunities to offer you, they can easily refer to other staff members who might.

Try navigating through your university’s website as well; many schools will have a student job board that may host research opportunities. For example, if you were a premed student at the University of Washington , you’d be able to check the Undergraduate Research Program (URP) database in order to filter and find research opportunities.

How Many Hours of Research Do You Need For Medical School?

Since research is not a requirement at most medical schools, there’s no minimum number of hours you should be spending at the lab. Some students report entering medical school with over 2,000 hours of research experience, while others had no more than 400.

This may seem like a lot but bear in mind that a semester or summer of research involvement sums up to around 500-800 hours. This can be more than enough to show your abilities, commitment, and critical thinking skills.

The hours you should dedicate to research widely depend on your personal circumstances and other aspects of your application. If you have the bandwidth to dedicate more hours to research, you should, but never compromise your grades for it.

6 Types of Medical Research

There are six main types of research that pre-med students commonly participate in:

Basic Science Research

Basic science research involves delving into the intricacies of biology in laboratory settings. It's one of the most common pre-med research opportunities and typically entails studying genes, cellular communication, or molecular processes.

Clinical Research

Clinical research is all about working with real patients to learn about health and illness. It's hands-on and great for getting a feel for healthcare.

Public Health Research

Public health research focuses on analyzing population health trends and developing strategies for disease prevention and health promotion. It's a great area for pre-med students interested in community health, although it is a little harder to get involved in.

Health Public Policy Research

Health public policy research examines the impact of healthcare regulations and policies on access to care and health outcomes. Although less common among pre-med students, it offers insights into the broader healthcare system, involving analyses of policy effectiveness and healthcare disparities.

Narrative Medicine Research

Narrative medicine research explores the role of storytelling and patient experiences in healthcare delivery. It's a more human side of medicine, focusing on empathy and connection.

Artificial Intelligence Research

Artificial intelligence research can be difficult for pre-meds to get involved in, but it offers innovative solutions to complex medical problems, such as developing AI algorithms for disease diagnosis and treatment planning.

Tips to Make the Best out of Research Hours

Now that we've covered the importance of research experience for med school application, we'll go over some tips to help you make the most of your research experience!