Prepressure

Prepress, printing, PDF, PostScript, fonts and stuff…

Home » Printing » The history of printing

The history of printing

Printing (graphic communication by multiplied impressions) has a long history behind it. This page describes its evolution. It acts as a summary of a more elaborate description that starts here . You can also click on the title of each century to get more in-depth information. There is a separate section on the history of prepress .

3000 BC and earlier

The Mesopotamians use round cylinder seals for rolling an impress of images onto clay tablets. In other early societies in China and Egypt, small stamps are used to print on cloth.

Second century AD

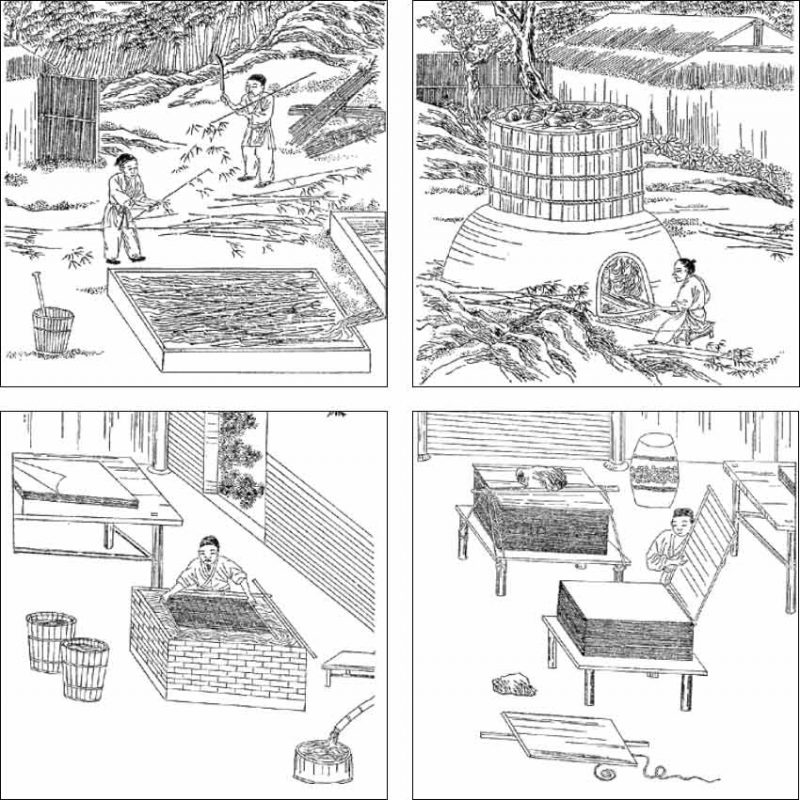

A Chinese eunuch court official named Ts’ai Lun (or Cai Lun) is credited with inventing paper.

Eleventh century

A Chinese man named Pi-Sheng develops type characters from hardened clay, creating the first movable type. The fairly soft material hampers the success of this technology.

Twelfth century

Papermaking reaches Europe.

Thirteenth century

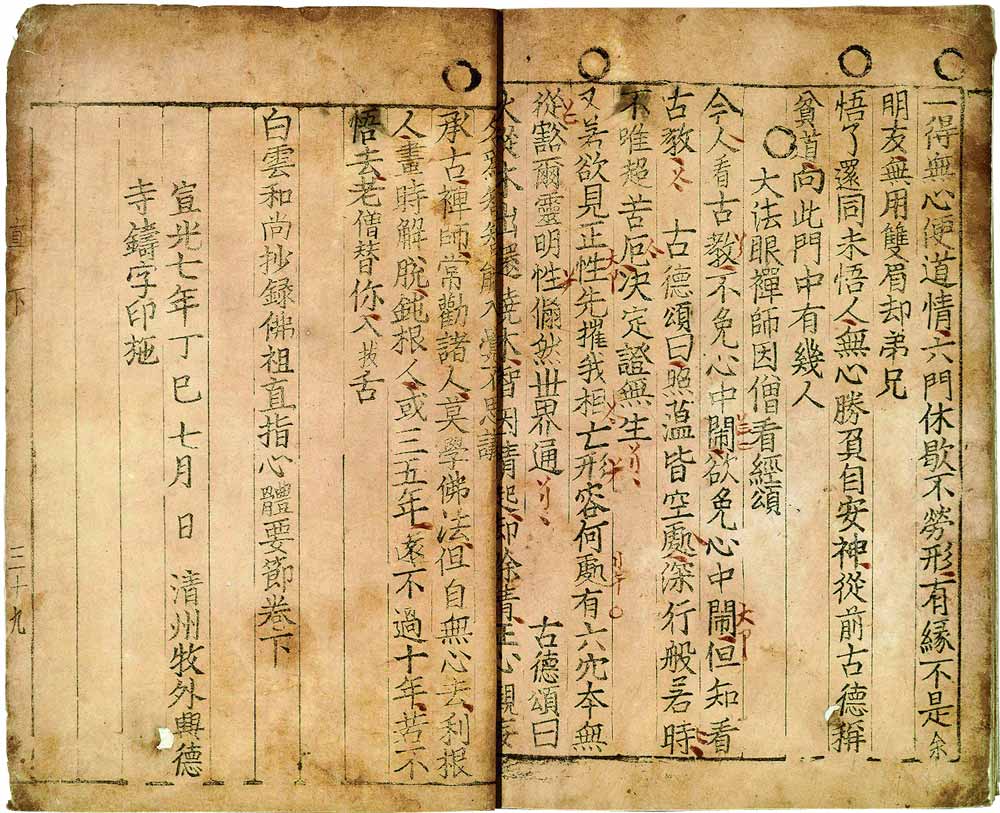

Type characters cast from metal (bronze) are developed in China, Japan and Korea. The oldest known book printed using metal type dates back to the year 1377. It is a Korean Buddhist document, called Selected Teachings of Buddhist Sages and Seon Masters .

Fifteenth century

Even though woodcut had already been in use for centuries in China and Japan, the oldest known European specimen dates from the beginning of the 15th century. Woodcut is a relief printing technique in which text and images are carved into the surface of a block of wood. The printing parts remain level with the surface while the non-printing parts are removed, typically with a knife or chisel. The woodblock is then inked and the substrate pressed against the woodblock. The ink that is used is made of lampblack (soot from oil lamps) mixed with varnish or boiled linseed oil.

Books are still rare since they need to be laboriously handwritten by scribes . The University of Cambridge has one of the largest libraries in Europe – constituting just 122 books.

In 1436 Gutenberg begins work on a printing press. It takes him 4 years to finish his wooden press which uses movable metal type. Among his first publications that get printed on the new device are bibles. The first edition has 40 lines per page. A later 42-line version comes in two volumes.

In 1465 the first drypoint engravings are created by the Housebook Master , a south German artist. Drypoint is a technique in which an image is incised into a (copper) plate with a hard-pointed ‘needle’ of sharp metal or a diamond point.

In their print shop in Venice John and Wendelin of Speier are probably the first printers to use pure roman type , which no longer looks like the handwritten characters that other printers have been trying to imitate until then.

In 1476 William Caxton buys equipment from the Netherlands and establishes the first printing press in England at Westminster. The painting below depicts Caxton showing his printing press to King Edward IV.

That same year copper engravings are for the first time used for illustrations. With engravings, a drawing is made on a copper plate by cutting grooves into it.

By the end of the century, printing has become established in more than 250 cities around Europe. One of the main challenges of the industry is distribution, which leads to the establishment of numerous book fairs. The most important one is the Frankfurt Book Fair .

Sixteenth century

Aldus Manutius is the first printer to come up with smaller, more portable books. He is also the first to use Italic type , designed by Venetian punchcutter Francesco Griffo.

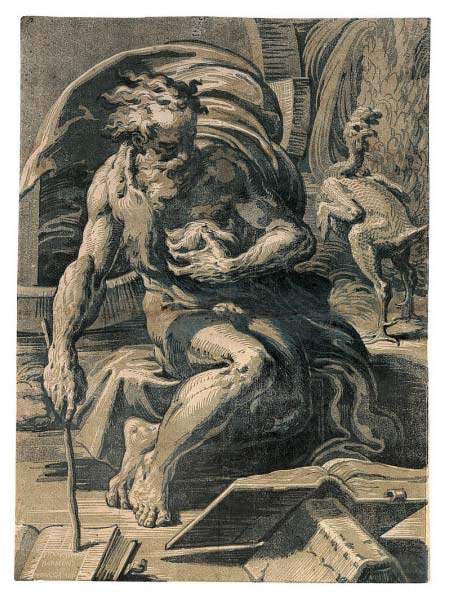

In 1507 Lucas Cranach invents the chiaroscuro woodcut , a technique in which drawings are reproduced using two or more blocks printed in different colors. The Italian Ugo da Carpi is one of the printers to use such woodcuts, for example in Diogenes , the work shown below.

In 1525 the famous painter, wood carver and copper engraver Albrecht Dürer publishes ‘Unterweysung der Messung’ (A Course on the Art of Measurement), a book on the geometry of letters.

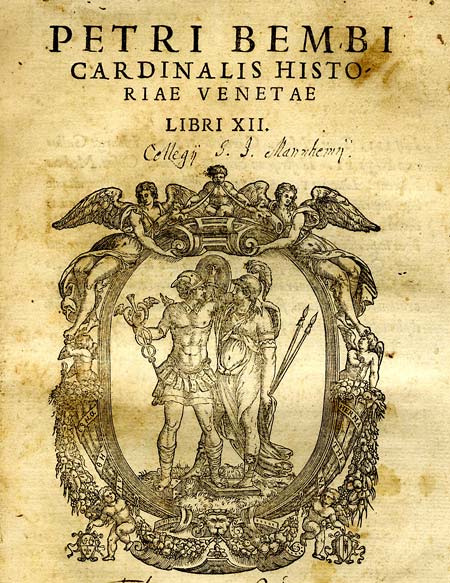

The ‘Historia Veneta’ (1551) is one of the many books of Pietro Bembo , a Venetian scholar, and cardinal who is most famous for his work on the Italian language and poetry. The Bembo typeface is named after him.

Christophe Plantin is one of the most famous printers of this century. In his print shop in Antwerp, he produces fine work ornamented with engravings after Rubens and other artists. Many of his works as well as some of the equipment from the shop can be admired in the Plantin-Moretus Museum .

Plantin is also the first to print a facsimile . A facsimile is a reproduction of an old book, manuscript, map, art print, or another item that is as true to the original source as possible.

Seventeenth century

The word ‘not’ is accidentally left out of Exodus 20:14 in a 1631 reprint of the King James Bible. The Archbishop of Canterbury and King Charles I are not amused when they learn that God commanded Moses “Thou shalt commit adultery”. The printers, Robert Barker and Martin Lucas, are fined and have their printing license revoked. This version of the Bible is referred to as The Wicked Bible and also called the Adulterous Bible or Sinner’s Bible.

In Paris, the Imprimerie Royale du Louvre is established in 1640 at the instigation of Richelieu. The first book that is published is ‘De Imitatione Christi’ ( The Imitation of Christ), a widely read Catholic Christian spiritual book that was first published in Latin around 1418.

In 1642 Ludwig von Siegen invents mezzotint , a technique to reproduce halftones by roughening a copper plate with thousands of little dots made by a metal tool with small teeth, called a ‘rocker’. The tiny pits in the plate hold the ink when the face of the plate is wiped clean.

The first American paper mill is established in 1690.

Eighteenth century

In 1710 the German painter and engraver Jakob Christof Le Blon produces the first engraving in several colors. He uses the mezzotint method to engrave three metal plates. Each plate is inked with a different color, using red, yellow, and blue. Later on, he adds a fourth plate, bearing black lines. This technique helped form the foundation for modern color printing. Le Bon’s work is based on Newton’s theory, published in 1702, which states that all colors in the spectrum are composed of the three primary colors blue, yellow, and red.

William Caslon is an English typographer whose foundry operates in London for over 200 years. His Caslon Roman Old Face is cut between 1716 and 1728. The letters are modeled on Dutch types but they are more delicate and not as monotonous. Caslon’s typefaces remain popular, digital versions are still available today.

The Gentleman’s Magazine is published for the first time in 1731. It is generally considered to be the first general-interest magazine. The publication runs uninterrupted until 1922.

In 1732 Benjamin Franklin establishes his own printing office and becomes the publisher of the Pennsylvania Gazette. Among his publications, Poor Richard’s Almanac becomes the most famous.

Alois Senefelder invents lithography in 1796 and uses it as a low-cost method for printing theatrical works. In a more refined form lithography is still the dominant printing technique today.

Another famous person from this era is Giambattista Bodoni who creates a series of typefaces that carry his name and that are still frequently used today. They are characterized by the sharp contrast between the thick vertical stems and thin horizontal hairlines.

Nineteenth century

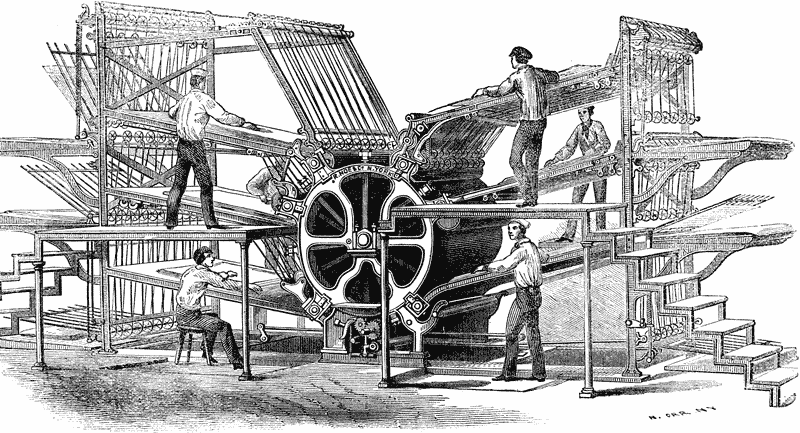

In 1800 Charles Stanhope, the third Earl Stanhope, builds the first press which has an iron frame instead of a wooden one. This Stanhope press is faster, more durable and it can print larger sheets. A few years later another performance improvement is achieved by Friedrich Gottlob Koenig and Andreas Friedrich Bauer who build their first cylinder press. Their company is still in existence today and is known as KBA .

In 1837 Godefroy Engelmann is awarded a patent on chromolithography , a method for printing in color using lithography. Chromolithographs or chromos are mainly used to reproduce paintings. The advertisement below is from the end of the century and shows what can be achieved using this color printing technique. Another popular technique is the photochrom process, which is mainly used to print postcards of landscapes .

The Illustrated London News is the world’s first illustrated weekly newspaper. It costs five pence in 1842. A year later Sir Henry Cole commissions the English painter John Callcott Horsley to do the artwork of (arguably) the first commercial Christmas card . Around 1000 cards are printed and hand-colored. Ten of these are still in existence today.

Around the same time, the American inventor Richard March Hoe builds the first lithographic rotary printing press , a press in which the type is placed on a revolving cylinder instead of a flatbed. This speeds up the printing process considerably.

The Czech painter Karel Klíč invents photogravur e in 1878. This process can be used to faithfully reproduce the detail and continuous tones of photographs.

In typesetting, Ottmar Mergenthaler’s 1886 invention of the Linotype composing machine is a major step forward. With this typesetter, an operator can enter text using a 90-character keyboard. The machine outputs the text as slugs, which are lines of metal type.

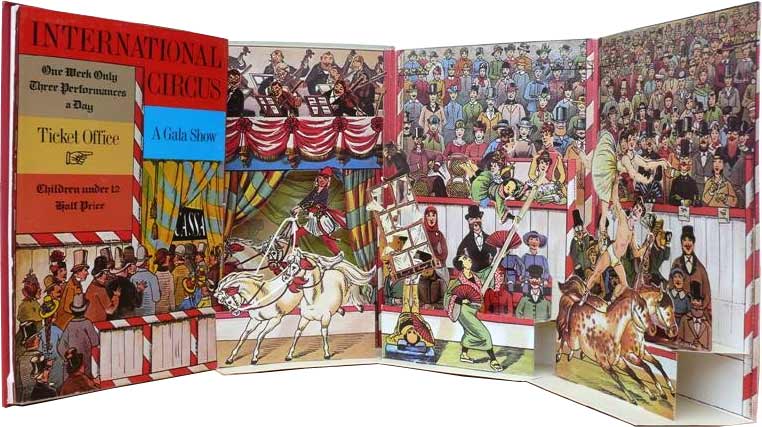

Lothar Meggendorfer’s International Circus is a nice example of the quality that could be achieved in those days. This pop-up book contains six pop-up scenes of circus acts, including acrobats, clowns, and daredevil riders.

In 1890 Bibby, Baron and Sons build the first flexographic press . This type of press uses the relief on a rubber printing plate to hold the image that needs to be printed. Because the ink that is used in that first flexo press smears easily, the device becomes known as Bibby’s Folly .

Twentieth century

In 1903 American printer Ira Washington Rubel is instrumental in producing the first lithographic offset press for paper. In offset presses, a rubber roller transfers the image from a printing plate or stone to the substrate. Such an offset cylinder was already in use for printing on metals, such as tin.

In 1907 the Englishman Samuel Simon is awarded a patent for the process of using silk fabric as a printing screen. Screen printing quickly becomes popular for producing expensive wallpaper and printing on fabrics such as linen and silk. Screen printing had first appeared in China during the Shang Dynasty (960–1279 AD).

A few of the new press manufacturers that appear on the market are Roland (nowadays known as Man Roland) in 1911 and Komori Machine Works in 1923.

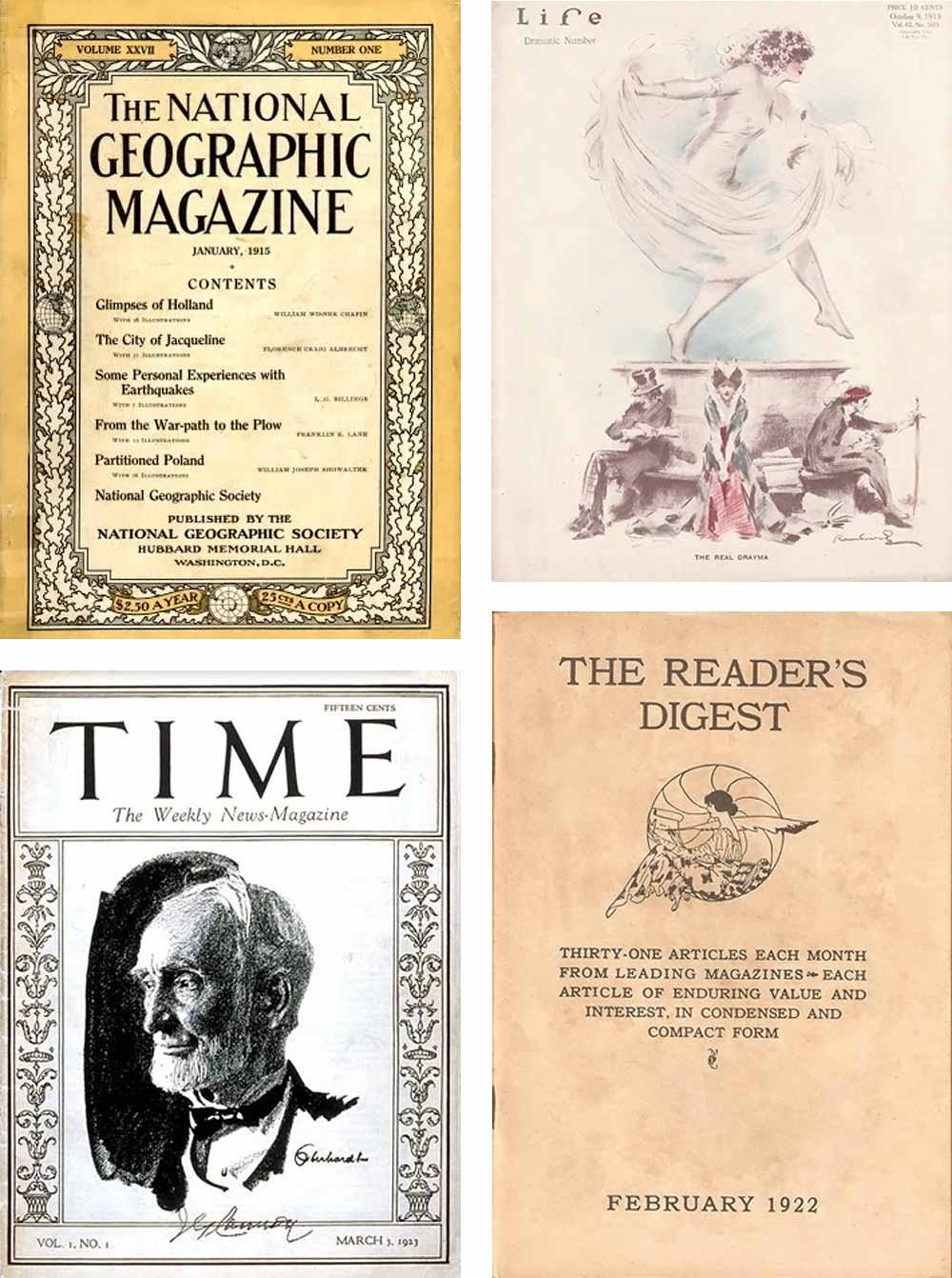

In 1915 Hallmark , founded in 1910, creates its first Christmas card. It is during this same era that magazines such as the National Geographic Magazine (1888), Life (1883, but focussing on photojournalism from 1936), Time (1923), Vogue (1892) and The Reader’s Digest (1920) starting reaching millions of readers.

Press manufacturer Koenig & Bauer launch the four-color Iris printing press in 1923. It can be used for printing banknotes. Over time security printing becomes one of the main focus points of the company.

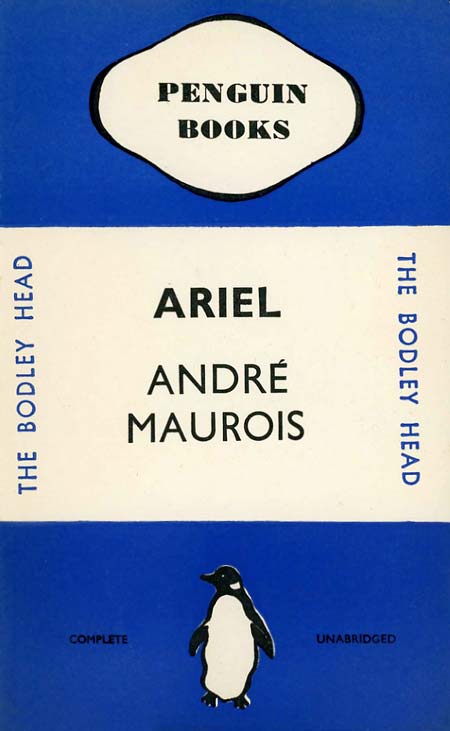

The first commercially successful series of paperback books are published by Penguin Books in the UK in 1935. Earlier in 1931 German publisher Albatross Books had already tried to market a series of lower-priced books with a paper cover and glue binding. Penguin copied many of the concepts of their failed attempt, such as the use of color-coded covers.

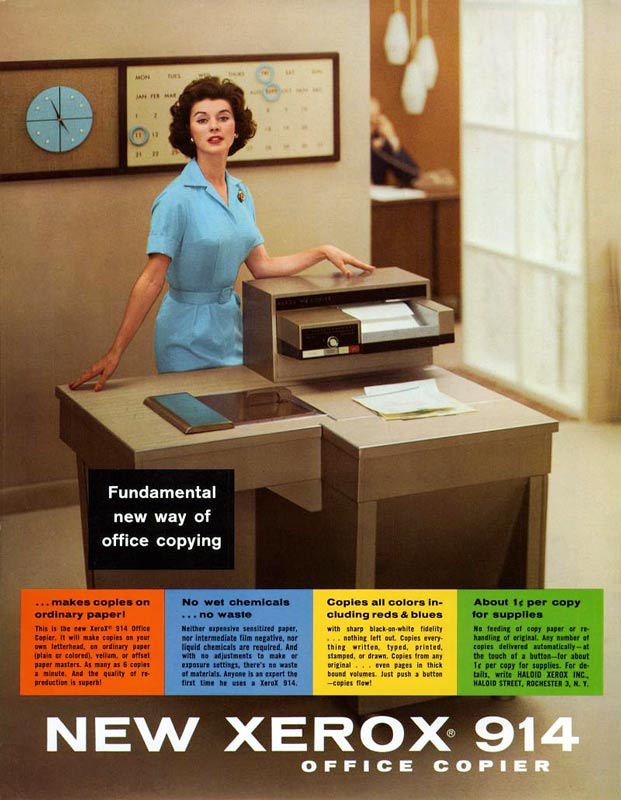

In 1938 Xerography , a dry photocopying technique is invented by Chester Carlson. The first commercial xerographic copier is introduced in 1949 but it is the 1959 Xerox 914 plain paper copier that is the breakthrough.

Japanese machine tool manufacturer Shinohara Machinery Company begins manufacturing flatbed letterpress machines in 1948. A popular press from that time is the Heidelberg Tiegel. The picture below shows it being demonstrated to German finance minister Ludwig Erhard at the first drupa trade show in 1951.

In 1967 the ISBN or International Standard Book Number started. This is a unique numeric identifier for commercial books. That same year Océ enters the office printing market with an electro-photographic process for copying documents using a special chemically-treated type of paper.

New materials like silicone make it possible for manufacturers such as Tampoprint to build more efficient presses for printing on curved surfaces. Pad printing can now be done on an industrial scale.

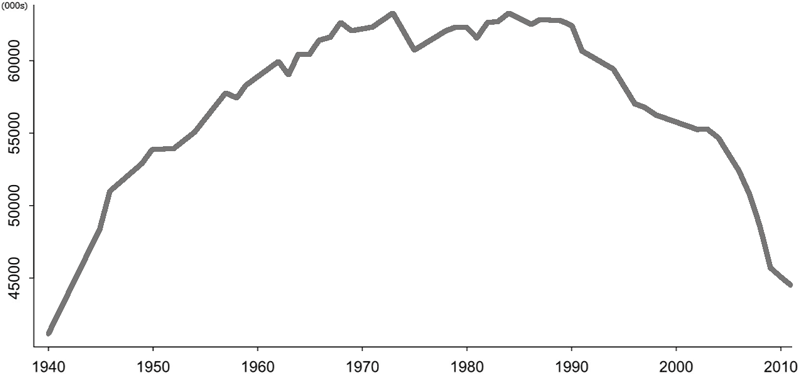

In the USA newspaper circulation reaches its highest level ever in 1973. It will remain fairly steady until a gradual decline sets in during the mid-’80s.

The first laser printers, such as the IBM 3800 and Xerox 9700 , hit the market in 1975. They are prohibitively expensive but useful for applications such as cheque printing.

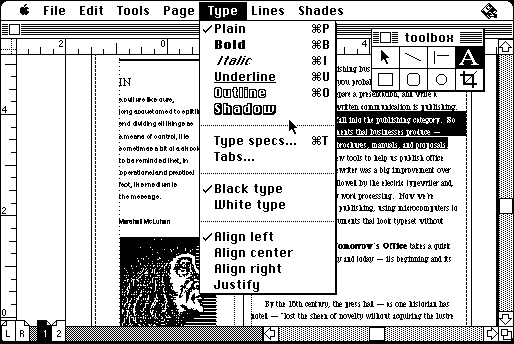

Desktop publishing takes off in 1985. The combination of the Apple Macintosh computer, printers and imagesetters powered by Adobe PostScript and the layout application Aldus PageMaker makes publishing more affordable.

At drupa 1986 MAN Roland Druckmaschinen AG introduces its LITHOMAN commercial web offset printing press. Polar shows off the POLAR Compucut , a system for computer-assisted, external generation of cutting programs with automatic transfer to the cutting machine.

The Xerox Docutech, launched in 1990, combines a 135 page-per-minute black & white xerographic print engine with a scanner and finisher modules. It is arguably the first affordable print-on-demand publishing system.

In 1992 Australia is the first country to use polymer banknotes for general circulation.

Digital printing takes off in 1993 with the introduction of the Indigo E-Print 100 (shown below) and Xeikon DCP-1.

Twenty-first century

Offset presses still evolve incrementally. Two prime examples are the introduction of the KBA Cortina, a waterless web press for newspapers and semi-commercials, in 2000, and that of the giant Goss Sunday 5000, the world’s first 96-page web press, in 2009.

Bigger changes happen in digital printing with machines that evolve as fast as the companies that produce them. Take the NexPress for example. It is initially a joint development from Heidelberg and Kodak, later taken over completely by Kodak.

One of the bigger players in the market is HP, especially after its acquisition of Indigo in 2001. Other big players in the market are Konica Minolta with the Bizhub digital presses and Canon with its Imagepress range. Part of Canon’s growth is through its acquisition of Océ in 2009.

One area of the market that evolves quickly is that of large format inkjet presses for the sign & display market. Inkjet technology also starts making inroads in the packaging industry. At the 2016 edition of drupa the EFI Nozomi C18000, HP PageWide C500, and Durst Rho 130 SPC (shown below) are all presses optimized for printing on corrugated packaging board.

16 thoughts on “ The history of printing ”

Great stuff, I wonder what the future of printing is ?

Very interesting article! Our offset presses are Heidelberg presses and our digital printers are Xerox. Love reading how both companies have been at the forefront of print

One of the most intriguing museums I’ve ever visited was the Shelburne Museum in Shelburne, VT. They have several different buildings with various collections which are all phenomenal. They have one building for Printing and Weaving.

https://shelburnemuseum.org/collection/printing-shop-weaving-shop/

That is very cool I would love to see it in person and not just over google

There’s a whole huge historical area you skip in the 60s, 70s. I used to be a paste-up artist. (Gee, wonder what that was.) I’d think you’d at least include a photo of one of those huge AB Dick presses.

i couldnt find what i needed!!!

…but we have no idea what you needed.

Very interesting article! Our offset presses are Heidelberg presses and our digital printers are Xerox. Love reading how both companies have been at the forefront of print, contributed so much, and been around for so long.

Very thorough article. Thank you

very intriguing to read all about thank you

Can you please share the 3D view of flex printing machine?

Where in the world is one or more museums that showcase the history of printing? Modern digital printing and what goes behind my typing in as we read and clicking it to print are, least understood by me. I guess by most. Ought not the German Museum of Gutenberg in Mainz, filling such a Gap? Naturally only if not already covered elsewhere? Love to get feedback.

You can find a list of printing museums on this page: https://www.aapainfo.org/printing-museums.html

Do you offer a pdf of this timeline?

No, I’ve been thinking about making an e-book version but feel that the pages still need some more work.

Interesting article as I am just researching my family tree and found Gt Gt Grandad was a stereotyper and Gt Grandad was a compositor. They lived and worked around Aldgate, Fleet St and Chancery Lane in London in mid 1800s. No idea where they worked but one was married in St Johns Gate which is the one featured in the May 1759 Gentlemans magazine featured in your article. They lived for a time in Cursitor St London where the Jewish Chronicle is still printed. I’d love to research more but I’m not sure where to go for info. Any help would be great.

Dear R Clarkson. Have you tried United Kingdom’s National Archive at Kew, Surrey, England. Its geneology section is worth a try if you have not done so.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The History of Printing and Printing Processes

The earliest dated printed book known is "Diamond Sutra"

Wang Jie / Wikimedia Commons

- Famous Inventions

- Famous Inventors

- Patents & Trademarks

- Invention Timelines

- Computers & The Internet

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

The earliest dated printed book known is "Diamond Sutra," printed in China in 868 CE. However, it is suspected that book printing may have occurred long before this date.

Back then, printing was limited in the number of editions made and nearly exclusively decorative, used for pictures and designs. The material to be printed was carved into wood, stone, and metal, rolled with ink or paint, and transferred by pressure to parchment or vellum. Books were hand copied mostly by members of religious orders.

In 1452, Johannes Gutenberg --a German blacksmith craftsman, goldsmith, printer, and inventor--printed copies of the Bible on the Gutenberg press, an innovative printing press machine that used movable type. It remained the standard until the 20th century.

A Timeline of Printing

- 618-906: T’ang Dynasty - The first printing is performed in China, using ink on carved wooden blocks; multiple transfers of an image to paper begins.

- 868: "Diamond Sutra" is printed.

- 1241: Koreans print books using movable type.

- 1300: The first use of wooden type in China begins.

- 1309: Europeans first make paper . However, the Chinese and Egyptians had started making paper in previous centuries.

- 1338: The first paper mill opened in France.

- 1390: The first paper mill opened in Germany.

- 1392: Foundries that can produce bronze type are opened in Korea.

- 1423: Block printing is used to print books in Europe.

- 1452: Metal plates are first used in printing in Europe. Johannes Gutenberg begins printing the Bible, which he finishes in 1456.

- 1457: The first color printing is produced by Fust and Schoeffer.

- 1465: Drypoint engravings are invented by Germans.

- 1476: William Caxton begins using a Gutenberg printing press in England.

- 1477: Intaglio is first used for book illustration for Flemish book "Il Monte Sancto di Dio."

- 1495: The first paper mill opened in England.

- 1501: Italic type is first used.

- 1550: Wallpaper is introduced in Europe.

- 1605: The first weekly newspaper is published in Antwerp.

- 1611: The King James Bible is published.

- 1660: Mezzotint--a method of engraving on copper or steel by burnishing or scraping away a uniformly roughened surface--is invented in Germany.

- 1691: The first paper mill is opened in the American colonies.

- 1702: Multicolored engraving is invented by German Jakob Le Blon. The first English-language daily newspaper--The Daily Courant--is published called.

- 1725: Stereotyping is invented by William Ged in Scotland.

- 1800: Iron printing presses are invented.

- 1819: The rotary printing press is invented by David Napier.

- 1829: Embossed printing is invented by Louis Braille.

- 1841: The type-composing machine is invented.

- 1844: Electrotyping is invented.

- 1846: The cylinder press is invented by Richard Hoe; it can print 8,000 sheets per hour.

- 1863: The rotary web-fed letterpress is invented by William Bullock.

- 1865: The web offset press can print on both sides of the paper at once.

- 1886: The linotype composing machine is invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler.

- 1870: Paper is now mass-manufactured from wood pulp.

- 1878: Photogravure printing is invented by Karl Klic.

- 1890: The mimeograph machine is introduced.

- 1891: Printing presses can now print and fold 90,000 four-page papers per hour. Diazotype--in which photographs are printed on fabric--is invented.

- 1892: The four-color rotary press is invented.

- 1904: Offset lithography becomes common, and the first comic book is published.

- 1907: Commercial silk screening is invented.

- 1947: Phototypesetting is made practical.

- 59 B.C.: "Acta Diurna," the first newspaper, is published in Rome.

- 1556: The first monthly newspaper, "Notizie Scritte," is published in Venice.

- 1605: The first printed newspaper published weekly in Antwerp is called "Relation."

- 1631: The first French newspaper, "The Gazette," is published.

- 1645: "Post-och Inrikes Tidningar" is published in Sweden and is still being published today, making it the world's oldest newspaper.

- 1690: The first newspaper is published in America: "Publick Occurrences."

- 1702: The first English-language daily newspaper is published: "The Daily Courant." The "Courant" was first published as a periodical in 1621.

- 1704: Considered the world’s first journalist, Daniel Defoe publishes "The Review."

- 1803: The first newspapers to be published in Australia include "The Sydney Gazette" and "New South Wales Advertiser."

- 1830: The number of newspapers published in the United States is 715.

- 1831: The famous abolitionist newspaper "The Liberator" is first published by William Lloyd Garrison .

- 1833: The "New York Sun" newspaper costs one cent and is the beginning of the penny press .

- 1844: The first newspaper is published in Thailand.

- 1848: The "Brooklyn Freeman" newspaper is first published by Walt Whitman .

- 1850: P.T. Barnum starts running newspaper ads for Jenny Lind, the " Swedish Nightingale " performances in America.

- 1851: The United States Post Office starts offering a cheap newspaper rate.

- 1855: The first newspaper published in Sierra Leone.

- 1856: The first full-page newspaper ad is published in the "New York Ledger." Large type newspaper ads are made popular by photographer Mathew Brady. Machines now mechanically fold newspapers.

- 1860: "The New York Herald" starts the first morgue--a "morgue" in newspaper terms means an archive.

- 1864: William James Carlton of J. Walter Thompson Company begins selling advertising space in newspapers. The J. Walter Thompson Company is the longest-running American advertising agency.

- 1867: The first double column advertising appears for the department store Lord & Taylor.

- 1869: Newspaper circulation numbers are published by George P. Rowell in the first Rowell's American Newspaper Directory.

- 1870: The number of newspapers published in the United States is 5,091.

- 1871: The first newspaper published in Japan is the daily "Yokohama Mainichi Shimbun."

- 1873: The first illustrated daily newspaper, "The Daily Graphic," is published in New York.

- 1877: The first weather report with a map is published in Australia. "The Washington Post" newspaper first publishes, with a circulation of 10,000 and a cost of 3 cents per paper.

- 1879: The benday process--a technique for producing shading, texture or tone in line drawings and photographs by overlaying a fine screen or a pattern of dots, which is named after illustrator and printer Benjamin Day--improves newspapers. The first whole-page newspaper ad is placed by American department store Wanamaker's.

- 1880: The first halftone photograph--Shantytown--is published in a newspaper.

- 1885: Newspapers are delivered daily by train.

- 1887: "The San Francisco Examiner" is published.

- 1893: The Royal Baking Powder Company becomes the biggest newspaper advertiser in the world.

- 1903: The first tabloid-style newspaper, "The Daily Mirror," is published.

- 1931: Newspaper funnies now include Plainclothes Tracy, starring Dick Tracy.

- 1933: A battle develops between the newspaper and radio industries. American newspapers try to force the Associated Press to terminate news service to radio stations.

- 1955: Teletype-setting is used for newspapers.

- 1967: Newspapers use digital production processes and begin using computers for operations.

- 1971: The use of offset presses becomes common.

- 1977: The first public access to archives is offered by Toronto's "Globe and Mail."

- 2007: There are now 1,456 daily newspapers in the United States alone, selling 55 million copies a day.

- 2009: This was the worst year in decades as far as advertising revenues for newspapers. Newspapers begin moving into online versions.

- 2010-present:resent: Digital printing becomes the new norm, as commercial printing and publishing fade slightly due to technology.

- History of Computer Printers

- Here Is a Brief History of Print Journalism in America

- The Early History of Communication

- History's 15 Most Popular Inventors

- The African American Press Timeline: 1827 to 1895

- Key Events in the History of the English Language

- The Colorful History of Comic Books and Newspaper Cartoon Strips

- Biography of Johannes Gutenberg, German Inventor of the Printing Press

- Today in History: Inventions, Patents, and Copyrights

- Biography of Benjamin Franklin, Printer, Inventor, Statesman

- Imposition for Commercial Print Jobs

- The Role Printing Plates Play in the Printing Process

- The History of Photography: Pinholes and Polaroids to Digital Images

- Definition and Examples of Periods: Full Stop

- The Power of the Press: Black American News Publications in the Jim Crow Era

- Robert Sengstacke Abbott: Publisher of "The Chicago Defender"

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

7 Ways the Printing Press Changed the World

By: Dave Roos

Updated: March 27, 2023 | Original: August 28, 2019

Knowledge is power, as the saying goes, and the invention of the mechanical movable type printing press helped disseminate knowledge wider and faster than ever before.

German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg is credited with inventing the printing press around 1436, although he was far from the first to automate the book-printing process. Woodblock printing in China dates back to the 9th century and Korean bookmakers were printing with moveable metal type a century before Gutenberg.

But most historians believe Gutenberg’s adaptation, which employed a screw-type wine press to squeeze down evenly on the inked metal type, was the key to unlocking the modern age. With the newfound ability to inexpensively mass-produce books on every imaginable topic, revolutionary ideas and priceless ancient knowledge were placed in the hands of every literate European, whose numbers doubled every century.

Here are just some of the ways the printing press helped pull Europe out of the Middle Ages and accelerate human progress.

1. A Global News Network Was Launched

Gutenberg didn’t live to see the immense impact of his invention. His greatest accomplishment was the first print run of the Bible in Latin, which took three years to print around 200 copies, a miraculously speedy achievement in the day of hand-copied manuscripts.

But as historian Ada Palmer explains, Gutenberg’s invention wasn’t profitable until there was a distribution network for books. Palmer, a professor of early modern European history at the University of Chicago, compares early printed books like the Gutenberg Bible to how e-books struggled to find a market before Amazon introduced the Kindle.

“Congratulations, you’ve printed 200 copies of the Bible; there are about three people in your town who can read the Bible in Latin,” says Palmer. “What are you going to do with the other 197 copies?”

Gutenberg died penniless, his presses impounded by his creditors. Other German printers fled for greener pastures, eventually arriving in Venice, which was the central shipping hub of the Mediterranean in the late 15th century.

“If you printed 200 copies of a book in Venice, you could sell five to the captain of each ship leaving port,” says Palmer, which created the first mass-distribution mechanism for printed books.

The ships left Venice carrying religious texts and literature, but also breaking news from across the known world. Printers in Venice sold four-page news pamphlets to sailors, and when their ships arrived in distant ports, local printers would copy the pamphlets and hand them off to riders who would race them off to dozens of towns.

Since literacy rates were still very low in the 1490s, locals would gather at the pub to hear a paid reader recite the latest news, which was everything from bawdy scandals to war reports.

“This radically changed the consumption of news,” says Palmer. “It made it normal to go check the news every day.”

2. The Renaissance Kicked Into High Gear

The Italian Renaissance began nearly a century before Gutenberg invented his printing press when 14th-century political leaders in Italian city-states like Rome and Florence set out to revive the Ancient Roman educational system that had produced giants like Caesar, Cicero and Seneca.

One of the chief projects of the early Renaissance was to find long-lost works by figures like Plato and Aristotle and republish them. Wealthy patrons funded expensive expeditions across the Alps in search of isolated monasteries. Italian emissaries spent years in the Ottoman Empire learning enough Ancient Greek and Arabic to translate and copy rare texts into Latin.

The operation to retrieve classic texts was in action long before the printing press, but publishing the texts had been arduously slow and prohibitively expensive for anyone other than the richest of the rich. Palmer says that one hand-copied book in the 14th century cost as much as a house and libraries cost a small fortune. The largest European library in 1300 was the university library of Paris, which had 300 total manuscripts.

By the 1490s, when Venice was the book-printing capital of Europe, a printed copy of a great work by Cicero only cost a month’s salary for a school teacher. The printing press didn’t launch the Renaissance, but it vastly accelerated the rediscovery and sharing of knowledge.

“Suddenly, what had been a project to educate only the few wealthiest elite in this society could now become a project to put a library in every medium-sized town, and a library in the house of every reasonably wealthy merchant family,” says Palmer.

3. Martin Luther Becomes the First Best-Selling Author

There’s a famous quote attributed to German religious reformer Martin Luther that sums up the role of the printing press in the Protestant Reformation: “Printing is the ultimate gift of God and the greatest one.”

Luther wasn’t the first theologian to question the Church, but he was the first to widely publish his message. Other “heretics” saw their movements quickly quashed by Church authorities and the few copies of their writings easily destroyed. But the timing of Luther’s crusade against the selling of indulgences coincided with an explosion of printing presses across Europe.

As the legend goes, Luther nailed his “95 Theses” to the church door in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517. Palmer says that broadsheet copies of Luther’s document were being printed in London as quickly as 17 days later.

Thanks to the printing press and the timely power of his message, Luther became the world’s first best-selling author. Luther’s translation of the New Testament into German sold 5,000 copies in just two weeks. From 1518 to 1525, Luther’s writings accounted for a third of all books sold in Germany and his German Bible went through more than 430 editions.

4. Printing Powers the Scientific Revolution

The English philosopher Francis Bacon, who’s credited with developing the scientific method, wrote in 1620 that the three inventions that forever changed the world were gunpowder , the nautical compass and the printing press.

For millennia, science was a largely solitary pursuit. Great mathematicians and natural philosophers were separated by geography, language and the sloth-like pace of hand-written publishing. Not only were handwritten copies of scientific data expensive and hard to come by, they were also prone to human error.

With the newfound ability to publish and share scientific findings and experimental data with a wide audience, science took great leaps forward in the 16th and 17th centuries. When developing his sun-centric model of the galaxy in the early 1500s, for example, Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus relied not only on his own heavenly observations, but on printed astronomical tables of planetary movements.

When historian Elizabeth Eisenstein wrote her 1980 book about the impact of the printing press, she said that its biggest gift to science wasn’t necessarily the speed at which ideas could spread with printed books, but the accuracy with which the original data were copied. With printed formulas and mathematical tables in hand, scientists could trust the fidelity of existing data and devote more energy to breaking new ground.

5. Fringe Voices Get a Platform

“Whenever a new information technology comes along, and this includes the printing press, among the very first groups to be ‘loud’ in it are the people who were silenced in the earlier system, which means radical voices,” says Palmer.

It takes effort to adopt a new information technology, whether it’s the ham radio, an internet bulletin board, or Instagram. The people most willing to take risks and make the effort to be early adopters are those who had no voice before that technology existed.

“In the print revolution, that meant radical heresies, radical Christian splinter groups, radical egalitarian groups, critics of the government,” says Palmer. “The Protestant Reformation is only one of many symptoms of print enabling these voices to be heard.”

As critical and alternative opinions entered the public discourse, those in power tried to censor it. Before the printing press, censorship was easy. All it required was killing the “heretic” and burning his or her handful of notebooks.

But after the printing press, Palmer says it became nearly impossible to destroy all copies of a dangerous idea. And the more dangerous a book was claimed to be, the more the people wanted to read it. Every time the Church published a list of banned books, the booksellers knew exactly what they should print next.

6. From Public Opinion to Popular Revolution

During the Enlightenment era, philosophers like John Locke , Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau were widely read among an increasingly literate populace. Their elevation of critical reasoning above custom and tradition encouraged people to question religious authority and prize personal liberty.

Increasing democratization of knowledge in the Enlightenment era led to the development of public opinion and its power to topple the ruling elite. Writing in pre-Revolution France, Louis-Sebástien Mercier declared:

“A great and momentous revolution in our ideas has taken place within the last thirty years. Public opinion has now become a preponderant power in Europe, one that cannot be resisted… one may hope that enlightened ideas will bring about the greatest good on Earth and that tyrants of all kinds will tremble before the universal cry that echoes everywhere, awakening Europe from its slumbers.”

“[Printing] is the most beautiful gift from heaven,” continues Mercier. “It soon will change the countenance of the universe… Printing was only born a short while ago, and already everything is heading toward perfection… Tremble, therefore, tyrants of the world! Tremble before the virtuous writer!”

Even the illiterate couldn’t resist the attraction of revolutionary Enlightenment authors, Palmer says. When Thomas Paine published “Common Sense” in 1776 , the literacy rate in the American colonies was around 15 percent, yet there were more copies printed and sold of the revolutionary tract than the entire population of the colonies.

7. Machines ‘Steal Jobs’ From Workers

The Industrial Revolution didn’t get into full swing in Europe until the mid-18th century, but you can make the argument that the printing press introduced the world to the idea of machines “stealing jobs” from workers.

Before Gutenberg’s paradigm-shifting invention, scribes were in high demand. Bookmakers would employ dozens of trained artisans to painstakingly hand-copy and illuminate manuscripts. But by the late 15th century, the printing press had rendered their unique skillset all but obsolete.

On the flip side, the huge demand for printed material spawned the creation of an entirely new industry of printers, brick-and-mortar booksellers and enterprising street peddlers. Among those who got his start as a printer's apprentice was future Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin.

HISTORY Vault: 101 Inventions That Changed the World

Take a closer look at the inventions that have transformed our lives far beyond our homes (the steam engine), our planet (the telescope) and our wildest dreams (the internet).

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Skip to the good stuff!

Printing History

Submissions | Back Issues | Advertising | Editors

Printing History , the semiannual peer-reviewed journal of the American Printing HistoryAssociation (APHA), has been published since 1979. Digital copies of the journal are available on the Gale and EBSCO databases. The journal is available in paper format as a benefit of membership in APHA.

Befitting a publication devoted to these subjects, Printing History is an artifact in its own right that reflects the histories it documents. The journal is beautifully designed, illustrated, and printed and is available only in paper format through membership in APHA.

Accordingly, Printing History is a highly desirable advertising venue that is circulated widely amongst those concerned with the production of printed materials. Consider becoming part of that community of readers, and part of the publication’s legacy, through purchasing advertising space.

Please direct all correspondence and inquiries about Printing History to Josef Beery, Vice President for Publications, at [email protected] .

Printing History follows the guidelines of The Chicago Manual of Style .

Back to top

submitting an article to printing history

The editor welcomes submissions on any aspect of printing history and its related arts; contributors need not be members of APHA. Articles, book reviews, and other journal submissions should be sent to [email protected] .

We are readily prepared to receive submissions that are created in the major word processing programs. Images should, ideally, be submitted as 600 ppi files in the TIF format on CDs or DVDs. In general, we follow the guidelines of The Chicago Manual of Style . Footnotes, rather than endnotes, are the preferred form of documentation. Printing History is indexed in Library Literature and the MLA International Bibliography .

Back issues of Printing History

Back issues of Printing History are indexed in Library Literature and the MLA International Bibliography . Back issues of the new series are searchable in EBSCO and Gale online academic databases. Many back issues of both the original and the new series are available for purchase .

Advertising in Printing History

To place an ad, please contact Josef Beery, Vice President for Publications, at [email protected]. Please supply your advertisement as a high-resolution, press-ready grayscale PDF file in an attachment. (Color advertising is available at an additional charge.)

Original artwork (before making the PDF) should be 1200 ppi for line art and 300 ppi for halftones at the ad’s finished size.

Printing History was founded in 1979; since then it has been edited by Susan Otis Thompson, Anna Lou Ashby, Renee I. Weber, and David Pankow. The first 50 issues of the journal constitute the Original Series —many of which are now on sale .

Printing History New Series began in 2007 under the editorship of William S. Peterson, Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Maryland, former editor of Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, and the author of books about the Kelmscott Press and Daniel Berkeley Updike.

In July 2011, Peterson was succeeded by William T. La Moy, curator of rare books and printed materials at the Special Collections Research Center at Syracuse University Library.

In 2016, La Moy was succeeded by Brooke S. Palmieri, a Ph.D Candidate in History at University College London.

In 2021, George Barnum, then Vice President for Publications, edited NS 29/30

In 2022, Daniel Arbino was the guest editor for NS 31/32.

In 2023, Danelle Moon will be the guest editor for NS 33.

- Back issues of Printing History

- Website Production Notes

- Administrative login

- American Printing History Association

- PO Box 4519

- Grand Central Station

- New York NY 10163-4519

© 2024 American Printing History Association

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Print, the press, and the american revolution.

- Robert G. Parkinson Robert G. Parkinson Binghamton University, SUNY

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.9

- Published online: 03 September 2015

According to David Ramsay, one of the first historians of the American Revolution, “in establishing American independence, the pen and press had merit equal to that of the sword.” Because of the unstable and fragile notions of unity among the thirteen American colonies, print acted as a binding agent that mitigated the chances that the colonies would not support one another when war with Britain broke out in 1775.

Two major types of print dealt with the political process of the American Revolution: pamphlets and newspapers. Pamphlets were one of the most important conveyors of ideas during the imperial crisis. Often written by elites under pseudonyms and published by booksellers, they have long been held by historians as the lifeblood of the American Revolution. There were also three dozen newspaper printers in the American mainland colonies at the start of the Revolution, each producing a four-page issue every week. These weekly papers, or one-sheet broadsides that appeared in American cities even more frequently, were the most important communication avenue to keep colonists informed of events hundreds of miles away. Because of the structure of the newspaper business in the 18th century, the stories that appeared in each paper were “exchanged” from other papers in different cities, creating a uniform effect akin to a modern news wire. The exchange system allowed for the same story to appear across North America, and it provided the Revolutionaries with a method to shore up that fragile sense of unity. It is difficult to imagine American independence—as a popular idea let alone a possible policy decision—without understanding how print worked in colonial America in the mid-18th century.

- Common Sense

- freedom of the press

- Sons of Liberty

According to one of the first historians of the Revolution, “in establishing American independence, the pen and press had merit equal to that of the sword.” 1 Print—whether the trade in books, the number of weekly newspapers, or the mass of pamphlets, broadsides, and other imprints—increased dramatically in the middle of the 18th century, with the general trend of economic prosperity and growing cultural norms about “refinement” and “improvement.” In the 1760s, print became a contested site of imperial reform with the Stamp Act, when Parliament chose texts as the locus of the constitutional debate over the colonies’ place in the empire and their responsibility in sharing tax burdens. The Stamp Act and the colonists’ resistance politicized print—and printers—in new ways. For the remainder of the imperial crisis, print remained at the center of the colonial resistance movement, connecting disparate resistance groups to one another, and providing the most reliable communications network across the Atlantic littoral. Newspapers, pamphlets, and broadsides were, indeed, the lifeblood of American resistance. Because of the unstable and fragile notions of unity among the thirteen mainland American colonies, print acted as a binding agent that mitigated the chances that the colonies would not support one another when war with Britain broke out in 1775.

Two major types of print shaped the political processes of the American Revolution: pamphlets and newspapers. Pamphlets became strategic conveyors of ideas during the imperial crisis. Often written by elites under pseudonyms, they have long been held up by historians as agents of change in and of themselves—that texts like Thomas Paine’s Common Sense or John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania , to name two of the most famous, are often seen as actors themselves, driving the resistance movement forward. There were also three dozen newspapers active on the American mainland at the start of the Revolution, each producing a four-page issue once a week. Although these papers earlier in the 18th century had focused on news from European capitals and courts, with the burgeoning imperial crisis they began to feature news from other colonies. These weekly papers were the most important communication avenue that kept colonists informed of events hundreds of miles away. It is difficult to imagine American independence—as a popular idea let alone a potential policy decision—without understanding how print worked in colonial America in the later decades of the 18th century.

As Bernard Bailyn wrote in the foreword to his 1965 book, Pamphlets of the American Revolution , there were more than four hundred pamphlets published in the colonies on the imperial controversy up through 1776, and nearly four times that number by war’s end in 1783. 2 These pamphlets varied in their theme and approach, including tracts of constitutional theory or history, sermons and orations, correspondence, literary pieces, and political debate. Bailyn originally decided to print seventy-two of these in a significant project that began with fourteen dated 1750–1765. In a two-hundred-page general introduction to what promised to be a multivolume effort, Bailyn developed an interpretation about the content of what was to follow, an analysis that he would deepen a few years later in the seminal Ideological Origins of the American Revolution ( 1967 ).

According to Bailyn, the pamphlets—“booklets consisting of a few printer’s sheets, folded in various ways so as to make various sizes and numbers of pages and sold . . . for a few pence, at most a shilling or two”—were the “most important and characteristic writing of the American Revolution.” 3 They were normally small but quite flexible in size, ranging from ten to fifty pages in length. Because of this flexibility and cheap cost, they were printed everywhere. Bailyn found them especially grouped around three moments during the controversy: the Stamp Act crisis ( 1765–1766 ), the Townshend Duties and Boston Massacre ( 1767–1770 ), and the Boston Tea Party and Parliament’s response in the Coercive Acts ( 1774 ). In them, he argued, were the most creative and powerful arguments that drove the Anglo-American controversy to war and independence. No empty vessels of propaganda or intentional deceit, the political pamphlets clarified the abstract constitutional issues and sharpened American response, according to Bailyn.

The pamphlets channeled and focused colonial resistance by framing dissent via appeals to history and political experience. The pamphleteers often invoked the lessons from the fall of the Roman republic, the political strife of the English Civil War, and the libertarian warnings from those who opposed the administration of Robert Walpole in the early 1700s. They blended the political theories from republicans stretching back to the ancient world with English writers from the 17th and 18th centuries. Together, they instructed the colonial public that political and personal liberty were in jeopardy because British imperial reformers sought to strip them of their natural rights, especially the right to consent to a government that could hear and understand them. Without representation, American colonists were political dependents who lacked any form of redress. Many of the pamphlets assumed a significant amount of knowledge of recent and ancient history, as well as sophisticated understandings of constitutional and legal relationships. The most successful, however, were those who aimed their rhetoric to a larger reading public. Tom Paine’s Common Sense , is, of course, the classic example. Paine eschewed a learned style and posture and instead embraced vernacular language and forwarded arguments drawn from more readily understood sources, especially the Bible.

Pamphlets that supported the Crown appeared within a few months of one another in late 1774 and early 1775 . From the Stamp Act in 1765 until this point, loyalists had dismissed the patriot movement as inconsequential and unpopular, viewing their street protests and constitutional arguments as, apparently, not worth the effort of refutation. Once the First Continental Congress met in September– October 1774 and, especially, after loyalists saw the wide popularity of the Continental Association (the extensive, general boycott that was to be binding in all colonies) passed by that body, they suddenly realized this effort was worthwhile after all. Pamphlets by Samuel Seabury, Thomas Chandler, and Daniel Leonard all appeared during this frenzied moment, trying to halt the wave of patriot support, but it was largely too late. Although the patriots took their efforts seriously—John Adams (writing as “Novanglus”) saw it to engage Leonard (writing as “Massachusettensis”) point-by-point in extended newspaper exchanges—the loyalists had waited too long to present their side to the colonial public.

The key political pamphlets that supported resistance from 1765 to 1776 are: James Otis, Rights of British Colonies Asserted and Proved (Boston, 1764 ); Richard Bland, Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies (Williamsburg, 1766 ); John Dickinson, Letters of a Farmer in Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, 1768 ); James Warren, Oration to Commemorate the Bloody Tragedy of the Fifth of March, 1770 (Boston, 1772 ); Thomas Jefferson, A Summary View of the Rights of British Americans (Williamsburg, 1774 ); Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Philadelphia, 1776 ); and John Adams, Thoughts on Government (Philadelphia, 1776 ).

The key political pamphlets that opposed colonial resistance from 1765 to 1776 are: Samuel Seabury, The Congress Canvassed (New York, 1774 ); Thomas B. Chandler, A Friendly Address to All Reasonable Americans (New York, 1774 ); Daniel Leonard, Origin of the American Contest . . . by Massachusettensis (Boston, 1775 ); Charles Inglis, The Deceiver Unmasked (New York, 1776 ); and James Chalmers, Plain Truth (Philadelphia, 1776 ).

Newspapers and the American Revolution

For much of the 18th century colonial newspaper printers published content that was mostly related to the affairs of government, whether proclamations, laws, orders, or money. This was by necessity; because of weak markets, tight credit, scare supplies, poor transportation, and irregular labor, printers who did not have a connection to government contracts had a near impossible time making ends meet. 4 Most colonial printers lived very precarious economic lives. Their social status was low—they worked hard, and with their hands—but their information largely came from gentlemen. They depended on the circles of gentle folk, but were not welcome in them. 5 The columns of their usually four-page weekly newspaper issues were filled with information from England and Europe before mid-century, usually stories taken from London papers. From their newspapers colonists knew far more about the goings-on at the courts and capitals of Europe than they did about one another. Printers depended on their colleagues in other cities for news: they sent free copies of their papers across the Atlantic for the purposes of the “exchanges”—the clipping of news items from one paper and placing it in your own issue. They also depended on local gentlemen and city officials to come into their shops bearing information of public import, whether a portion of a private letter that they volunteered to be anonymously extracted for public consumption, or documents with bearing on public concern that they ordered sent to the printer for publication. Printers were not seekers but receivers of information in the late 18th century. The “exchanges,” however, acted as a powerful tool for political mobilization. Because they acted in many ways like a modern newswire, carrying the same story almost intact from city to city, the “exchanges” provided a form of simultaneity and shared political experience. The exchange system provided the members of the colonial resistance movement with a method to shore up a very inchoate and unstable sense of intercolonial unity. Crafty patriot writers understood and used the “exchange” system to great advantage to get certain key messages or images that fostered resistance out to a wide continental public to foster support they would have otherwise had difficulty building.

Reliance on government largesse shifted in the 1760s, as political items, stories, and essays about the burgeoning “imperial crisis” appeared more frequently. Starting in the 1760s the number of newspapers rose significantly, doubling between 1763 and 1775 , and then doubling again from 1775 to 1790. 6 Political engagement also led to a shift away from the traditional efforts by newspaper printers earlier in the century to keep their columns open to both sides of debates. After the Stamp Act—whether because of personal political leanings or because they thought it best to suit their market niche—printers began to abandon the ideal of neutrality to embrace or reject colonial resistance of British imperial reform. 7 A few printers, including William Goddard (Providence), William Bradford (Philadelphia), Peter Timothy (Charleston), John Holt (New York City), Benjamin Edes and John Gill (Boston) joined in the “cause” in various ways, either by becoming members of the Sons of Liberty, opening their print shops for political meetings, or publishing a wide array of stories, essays, and items that supported the cause. On the other hand, a few other printers, including James Rivington, Richard Draper, and Robert Wells, made their newspapers available for loyalists to submit essays that criticized patriot resistance efforts.

Anonymity was a key feature of publication in the late 18th century. Authors of essays that either appeared in pamphlet form or were serialized across several weekly issues of newspapers often appeared under a pseudonym to protect all involved parties: the writer, the publisher, and the concept of a “free press.” But with printers taking increasingly polarized political stances—and popular understanding of the role of newspaper printers in the burgeoning “imperial crisis” shifting—the effectiveness of the shield of pseudonyms faltered.

For example, what happened at the end of 1767 between the printers of the Boston Gazette and Boston Chronicle illuminates the increasing political pressure on newspaper publishers, and the suddenness by which a confrontation could now escalate into violence. From its opening issue that year, the Boston Chronicle , published by recent Scot emigrant John Mein and his partner John Fleeming, provoked the city’s opponents of imperial reform. Mein and Fleeming started the Chronicle with an attack on two of the patriots’ favorite British leaders, the Earl of Chatham and the Marquis of Rockingham. Naturally, the Boston radicals who paid close attention to matters of print, that is, Samuel Adams and James Otis, fought back in their dedicated organ, Edes and Gill’s Boston Gazette . Under the cover of a pseudonym, Otis wrote an essay slandering Mein as a Jacobite. Soon an outraged Mein burst into the Gazette office demanding the contributor’s name, but got no satisfaction. Still fuming, a few nights later he caned his Gazette colleague John Gill on a Boston street. 8 Several weeks later, Samuel Adams, writing as “Populus,” described this clubbing not as a private affair between the two printers but instead a “Spaniard-like Attempt” to restrict press freedom. 9

Criminal charges and severe fines did not deter Mein. Nearly two years later, Mein and Fleeming sought to embarrass the Sons of Liberty once again, this time by revealing the caprice and self-interest that they thought really actuated the non-importation boycott the Sons had organized to resist the Townshend Duties. The Chronicle featured fifty-five lists of shipping manifests revealing the names of merchants who broke the non-importation agreement, including many who had actually signed the boycott. In response it was many upset Bostonians who embraced vigilantism this time. Mein and Fleeming had published the lists to suggest the boycott was really an effort to eliminate business competition on the part of merchants sympathetic to the Sons. Now they had to stuff pistols in their pockets to walk the streets of Boston. 10 In October the Boston town meeting condemned Mein as an enemy of his country, and a few days later a large crowd confronted the offending printers on King Street, producing a scuffle that left Mein bruised, Fleeming’s pistol empty, and a few dozen angry Bostonians facing British bayonets. Mein at first took shelter in the guardhouse, but, when Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson did not offer vigorous support, the truculent printer departed for England.

Evidence of a growing polarization and politicization, the clash between the Boston Gazette and Boston Chronicle was also about naming names. Mein wanted the Gazette printers to tell him who called him a Jacobite; his own paper’s revealing of the identities of importers animated the crowd and forced the Chronicle printer into exile. Anonymity was itself a transforming concept during the imperial crisis. Long a key feature of 18th-century print culture, with the republican claims of the patriots, anonymity took on a new significance in print, one that allowed for a broader inclusion of the public, and, by implication, the possibility of greater purchase by the people at large. As a rule, contributors to the newspapers shielded themselves with pseudonyms, often judiciously employed to cast themselves as public defenders (“Populus,” “Salus Populi,” “Rusticus”) or guardians of ancient liberty and virtue (“Mucius Scaevola,” “Cato,” “Nestor,” “Neoptelemus”). As one literary scholar has suggested, by adopting such identities those “guardians” were then not real , individual inhabitants of Boston or Philadelphia, with particular social interests, but universal promoters of republican liberty. 11 Analysts often point to the destruction of the concept of deference—a staple of 18th-century social structure—as a sign of the Revolution’s radicalness. The shift in the understanding of anonymity in print was a key factor in decoupling social status from political authority. That shift helped undermine deference as an organizing concept of American social and political culture.

Printers, then, mediated several fluid and rapidly changing concepts of both their professions and colonial politics before the Revolution. They were the keepers of very important political secrets. They alone knew who had submitted a manuscript for publication; only they could pierce the republican fiction of anonymity. Often, this position was precarious. As political pressure increased in the 1760s and 1770s, the impulse to throw off these veils was occasionally very strong. Printers periodically found themselves or their property in harm’s way if they refused to bow to the will of angry demands that they confess.

John Gill would not be the only one to suffer from this increasing imperative; throughout the Revolution several printers on both sides of the imperial question found themselves or their property at risk. In 1776 , when New York Packet printer Samuel Loudon dared to advertise the publication of a pamphlet that answered Tom Paine’s Common Sense and called the “scheme of Independence ruinous and delusive,” the Mechanics Committee, a radical patriot group created in 1774 out of the Sons of Liberty, summoned the printer to explain his behavior and reveal the author’s identity. 12 Loudon refused to tell the committee the Anglican rector of Trinity Church, Charles Inglis, had written the pamphlet, so six members of the committee went to his shop and, in Loudon’s words, “nailed and sealed up the printed sheets in boxes, except a few which were drying in an empty house, which they locked, and took the key with them.” 13 They warned Loudon to stop publishing the pamphlet, or else his “personal safety might be endangered.” Although he “promised to comply,” this pledge “availed nothing for my security.” Late the next night, forty men returned, broke into his office, grabbed all fifteen hundred copies of Inglis’s pamphlet, “carried them into the commons, and there burned them.” 14

The highly charged content of those publications, whether the weekly newspapers or pamphlets like The Deceiver Unmasked , also fueled partisanship. The imperial crisis witnessed what one scholar has called the advent of the “exposé” in America. 15 As printers increasingly gave space to contributors who claimed they were unmasking corruption or conspiracy, they aided in the disintegration of established concepts of what kept a press “free.” The most impassioned publications of the 1760s–1770s—Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, the chronicle of soldiers’ abuses known as the “Journal of Occurrences,” Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre, and Thomas Hutchinson’s private letters—all centered on revealing or dramatizing the government’s true aims of stripping American colonists of their liberties. There were not two sides to “truth.” Either behind pseudonyms or not, the patriot writers or artists who brought these plots to light claimed they were heroic servants of the people, informants seeking to protect an unwitting public from tyranny’s stealthy advance. This was not a debate. So framed, it was also a difficult position to counter. At the same time, the appearance of each of these “exposés” also represented a choice by the printers themselves. By giving space to the “truth”—and, by extension, to the protection of the people’s rights—they took a side that changed the older values of press freedom forever. A free or open press, they decided, did not have to allow equal space for opposing viewpoints that they characterized as endorsing lies and tyranny.

Print was an essential factor in pushing the colonists toward revolution even if it was not sufficient to cause the Revolution. Benjamin Franklin, it should not surprise, grasped perfectly the power of newspapers. “By the press we can speak to nations,” the printer-turned-politician wrote a friend in 1782. Thanks to newspapers, Franklin concluded, political leaders could not only “strike while the iron is hot” but also stoke fires by “continually striking.” 16 Those bundles of newspapers—dropped off at crossroad inns and subscribers’ rural estates in the countryside, distributed among urban taverns and gathering places in the cities, imported into the army camps—had the potential to be potent tools of revolutionary mobilization. Patriot leaders from the mid-1760s through the Treaty of Paris spent a great deal of time and, more illuminating, moneysupporting all kinds of print: subsidizing printers, aiding in paper supplies, contributing private correspondence to newspapers, ordering the publication of certain documents, treating printing presses as military contraband, sending pamphlets in diplomatic packets, arranging for illustrations for a child’s book of British atrocities. The journals of the proceedings of patriot political authorities at all levels, from local committees of safety, to state legislatures, to the Continental Congress, give evidence that they saw their actions as intertwined with printers. The working men and women attached to American print shops—the riders carrying papers to the countryside, the apprentices and slaves working the press, the journeymen assembling types, for example—were essential to the Revolution too.

A Guide to Newspapers during the American Revolution

On April 19, 1775, there were thirty-seven active newspapers in the colonies. When Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781, there were thirty-five. Of those original thirty-seven papers that printed the news of Lexington and Concord, only twenty made it through the war and very few of those were able to continue publishing a paper each week. This number would ebb and flow. War exacerbated printers’ capacity to secure ready supplies of materials, especially paper. Seventeen prewar prints would expire during the fighting while eighteen new ventures were started but were also discontinued at some point. The mean number for active newspapers between 1775 and 1783 is thirty-five; the approximate number of thirty-five holds up throughout the war’s duration.

In Boston, the engagements at Lexington and Concord instantly upended the city’s newspaper production. Three prints that defended the Ministry closed that month. Patriot papers, including Benjamin Edes and John Gill’s radical Boston Gazette and Isaiah Thomas’s Massachusetts Spy had to suspend publication as they fled to the countryside. On May 3, Thomas continued to print from Worcester, where he would stay throughout the remainder of the war. Edes also brought out the Boston Gazette again from Watertown on June 5. When the British evacuated Boston in March 1776 , the Boston Gazette again took up residence in the city, but the important Edes and Gill partnership had not survived the move out of Boston. John Gill started his own pro-American organ, the Continental Journal , in May. A fifth paper, Powers and Willis’s New England Chronicle became the Independent Chronicle in 1776 . In 1778 Edward Draper and John Folsom started another Boston paper, the Independent Ledger . For much of the war Boston boasted six prints. When one closed, another, like James White and Thomas Adams’s Boston Evening Post (which ran from October 1778 to March 1780 ) opened. Outside Boston, John Mycall published the Essex Journal in Newburyport from 1775 to early 1777 . In all, Massachusetts boasted of six long-lasting and important papers that supported the Revolution, with the Massachusetts Spy , Boston Gazette , and Continental Journal being the most significant.

Newspapers in Connecticut enjoyed the most stability during the war. The same four papers that contained the news of Lexington also reprinted the Treaty of Paris. Since the mid-18th century the powerful Green family dominated the colony’s print business. During the Revolution they operated the Connecticut Gazette in New London (Timothy Green) and the Connecticut Journal in New Haven (Thomas and Samuel Green). Ebenezer Watson and later George Goodwin and Barzillai Hudson ran the Green-founded Connecticut Courant in Hartford. None suffered suspensions or dislocations. The fourth, the Norwich Packet , had begun in 1773 by John Trumbull and two brothers, Alexander and James Robertson. In May 1776 , the Robertsons, who were loyalists from Scotland, went to New York, leaving Trumbull to operate the paper alone, which he did until 1802 .

If Connecticut was the land of steady print habits, the other New England provinces, New Hampshire and Rhode Island, were the opposite. Robert Fowle had published the New Hampshire Gazette in Portsmouth since his uncle had begun the business in 1756 . In 1776 , however, New Hampshire authorities suspected Fowle of counterfeiting and printing items against the “cause.” The Gazette ceased publication on January 9. A few months later Benjamin Dearborn picked up printing in Portsmouth with the Freeman’s Journal which operated until 1778 when Robert’s uncle Daniel took over and changed the name of the print back to the New Hampshire Gazette . The war’s intrusion also hampered the press in Rhode Island. John Carter, one of Franklin’s apprentices, was able to maintain his Whiggish Providence Gazette throughout the war. Solomon Southwick and the Newport Mercury were less lucky. In November 1775 , fearing an impending invasion, Southwick moved his materials out of his Newport office. A year later, when the British did occupy the city, he was forced to bury his press and types for four years. A patriot, Southwick tried to keep active by printing on a borrowed press in Attleborough and Providence in the interim, but the Newport Mercury lay dormant until January 1780 when Henry Barber carried on.

Southwick’s problems were minor compared to the experiences of New York’s printers. At the outbreak of war there were three papers in New York City: John Holt’s New York Journal , Hugh Gaine’s New York Gazette & Weekly Mercury , and James Rivington’s New York Gazetteer . Holt supported the Revolutionaries, Gaine equivocated, and Rivington was popularly known as the leading Tory printer in the colonies. In August 1775 , James Anderson began a second patriot press, the New York Constitutional Gazette , which brought out a paper three times a week. Another pro-American print began in January 1776 with Samuel Loudon beginning production of the New York Packet . These last two papers had little time to get settled because the British invasion in September 1776 changed everything. Anderson closed permanently, Loudon went to Fishkill, New York, Holt took his types to Kingston, New York (also known as Esopus), and Gaine fled for a few weeks to Newark, New Jersey. While Gaine was in New Jersey, the British army, lacking a paper, commissioned Ambrose Serle to start his own “engine.” Gaine, who had been printing a paper in New York since 1752 , decided after a few weeks that the British market would better serve his financial interests, and he returned to the city on November 11, 1776 , to displace Serle’s nascent operation. Gaine’s decision to turn his coat infuriated the Revolutionaries, and his name would be synonymous with deceit and greed for the remainder of the war. Philip Freneau’s stinging poem, “Hugh Gaine’s Life,” which some patriot printers happily published in 1783, typified this anger.

In occupied New York, papers flourished. In addition to Gaine, Rivington, the well-educated son of a prominent London book-seller, returned in 1777 and reestablished his print tri-weekly, the Robertson brothers from Norwich also began a bi-weekly Royal American Gazette that year, and when William Lewis started the New York Mercury in September 1779 , New York had a combination daily newspaper. Meanwhile, the dispersed patriot papers had a more difficult time outside the city. Outside the main avenues of communication, Loudon still managed to maintain publication of the Packet from Fishkill throughout the war. Holt published from Kingston from July to October 1777 when disaster struck again as the British sacked the town. In May 1778 he resurfaced in even more remote Poughkeepsie, New York, where he struggled to maintain his connections with Governor George Clinton and keep the New York Journal in circulation.

The presence of the British army in New York also meant that New Jersey would be an active theater of violence from 1776 onward. In December 1777 , Isaac Collins, a Quaker who was sponsored by Governor William Livingston and partly financed by the state, founded the New Jersey Gazette in Burlington. A few months later he relocated to Trenton, where he would maintain publication until July 1783 . Sheppard Kollock, a former Continental Army lieutenant, started a second newspaper ( New Jersey Journal ) in Chatham, New Jersey in February 1779 because Washington wanted his troops to have a newspaper while they were in winter quarters in nearby Morristown. Since a large number of Kollock’s subscribers were soldiers, this paper contained a high quotient of war news until the end of hostilities. The sponsorship of newspapers in New Jersey by patriot authorities suggests how they thought about the centrality of print to the war effort. The New Jersey state legislature and governor, the Continental Army, and Continental Congress all expended valuable time and money to put sheets of newsprint in the hands of soldiers and civilians in the zone between Philadelphia and occupied Manhattan.

Since the mid-18th century, Benjamin Franklin’s Philadelphia had been the center of colonial print culture. At the war’s outset, there were six English language newspapers being published in Philadelphia. The two oldest prints were the Pennsylvania Gazette and Pennsylvania Journal . David Hall and William Sellers now operated Franklin’s organ, the nearly fifty-year-old Pennsylvania Gazette , while William Bradford—who had branched into coffee houses, marine insurance—still operated the Pennsylvania Journal more than thirty years after its founding. Irish printer John Dunlap had joined them in 1771 with the Pennsylvania Packet , while three more papers, Benjamin Towne’s tri-weekly Pennsylvania Evening Post , Story and David Humphrey’s Pennsylvania Mercury , and John Humphreys Jr.’s Pennsylvania Ledger , began in early 1775 . Bradford and Dunlap were the most active Whigs among their colleagues, Hall and Sellers took a moderate course, John Humphreys tended toward the king, and Towne—like Gaine in New York—fended for himself. Congress spread their printing business around: for example John Dunlap was the first to produce a broadside text of the Declaration of Independence, while Towne had the honor of being the first to insert it in his July 6 issue. Delegates to the Continental Congress who wrote articles and essays sent them to Bradford and Dunlap.