Understanding Global Change

Discover why the climate and environment changes, your place in the Earth system, and paths to a resilient future.

Population growth

Population growth is the increase in the number of humans on Earth. For most of human history our population size was relatively stable. But with innovation and industrialization, energy, food , water , and medical care became more available and reliable. Consequently, global human population rapidly increased, and continues to do so, with dramatic impacts on global climate and ecosystems. We will need technological and social innovation to help us support the world’s population as we adapt to and mitigate climate and environmental changes.

World human population growth from 10,000 BC to 2019 AD. Data from: The United Nations

Human population growth impacts the Earth system in a variety of ways, including:

- Increasing the extraction of resources from the environment. These resources include fossil fuels (oil, gas, and coal), minerals, trees , water , and wildlife , especially in the oceans. The process of removing resources, in turn, often releases pollutants and waste that reduce air and water quality , and harm the health of humans and other species.

- Increasing the burning of fossil fuels for energy to generate electricity, and to power transportation (for example, cars and planes) and industrial processes.

- Increase in freshwater use for drinking, agriculture , recreation, and industrial processes. Freshwater is extracted from lakes, rivers, the ground, and man-made reservoirs.

- Increasing ecological impacts on environments. Forests and other habitats are disturbed or destroyed to construct urban areas including the construction of homes, businesses, and roads to accommodate growing populations. Additionally, as populations increase, more land is used for agricultural activities to grow crops and support livestock. This, in turn, can decrease species populations , geographic ranges , biodiversity , and alter interactions among organisms.

- Increasing fishing and hunting , which reduces species populations of the exploited species. Fishing and hunting can also indirectly increase numbers of species that are not fished or hunted if more resources become available for the species that remain in the ecosystem.

- Increasing the transport of invasive species , either intentionally or by accident, as people travel and import and export supplies. Urbanization also creates disturbed environments where invasive species often thrive and outcompete native species. For example, many invasive plant species thrive along strips of land next to roads and highways.

- The transmission of diseases . Humans living in densely populated areas can rapidly spread diseases within and among populations. Additionally, because transportation has become easier and more frequent, diseases can spread quickly to new regions.

Can you think of additional cause and effect relationships between human population growth and other parts of the Earth system?

Visit the burning of fossil fuels , agricultural activities , and urbanization pages to learn more about how processes and phenomena related to the size and distribution of human populations affect global climate and ecosystems.

Investigate

Learn more in these real-world examples, and challenge yourself to construct a model that explains the Earth system relationships.

- The Ecology of Human Populations: Thomas Malthus

- A Pleistocene Puzzle: Extinction in South America

Links to Learn More

- United Nations World Population Maps

- Scientific American: Does Population Growth Impact Climate Change?

This page has been archived and is no longer updated

An Introduction to Population Growth

Why Study Population Growth?

Population ecology is the study of how populations — of plants, animals, and other organisms — change over time and space and interact with their environment. Populations are groups of organisms of the same species living in the same area at the same time. They are described by characteristics that include:

- population size: the number of individuals in the population

- population density: how many individuals are in a particular area

- population growth: how the size of the population is changing over time.

If population growth is just one of many population characteristics, what makes studying it so important?

First, studying how and why populations grow (or shrink!) helps scientists make better predictions about future changes in population sizes and growth rates. This is essential for answering questions in areas such as biodiversity conservation (e.g., the polar bear population is declining, but how quickly, and when will it be so small that the population is at risk for extinction?) and human population growth (e.g., how fast will the human population grow, and what does that mean for climate change, resource use, and biodiversity?).

Studying population growth also helps scientists understand what causes changes in population sizes and growth rates. For example, fisheries scientists know that some salmon populations are declining, but do not necessarily know why. Are salmon populations declining because they have been overfished by humans? Has salmon habitat disappeared? Have ocean temperatures changed causing fewer salmon to survive to maturity? Or, maybe even more likely, is it a combination of these things? If scientists do not understand what is causing the declines, it is much more difficult for them to do anything about it. And remember, learning what is probably not affecting a population can be as informative as learning what is.

Finally, studying population growth gives scientists insight into how organisms interact with each other and with their environments. This is especially meaningful when considering the potential impacts of climate change and other changes in environmental factors (how will populations respond to changing temperatures? To drought? Will one population prosper after another declines?).

Ok, studying population growth is important...where should we start?

Population Growth Basics and the American Bison

The US government, along with private landowners, began attempts to save the American bison from extinction by establishing protected herds in the late 1800's and early 1900's. The herds started small, but with plentiful resources and few predators, they grew quickly. The bison population in northern Yellowstone National Park (YNP) increased from 21 bison in 1902 to 250 in only 13 years (Figure 1, Gates et al . 2010).

The yearly increase in the northern YNP bison population between 1902 and 1915 can be described as exponential growth . A population that grows exponentially adds increasingly more individuals as the population size increases. The original adult bison mate and have calves, those calves grow into adults who have calves, and so on. This generates much faster growth than, say, adding a constant number of individuals to the population each year.

Exponential growth works by leveraging increases in population size, and does not require increases in population growth rates. The northern YNP bison herd grew at a relatively constant rate of 18% per year between 1902 and 1915 (Gates et al . 2010). This meant that the herd only added between 4 and 9 individuals in the first couple of years, but added closer to 50 individuals by 1914 when the population was larger and more individuals were reproducing. Speaking of reproduction, how often a species reproduces can affect how scientists describe population growth (see Figure 2 to learn more).

Figure 2: Bison young are born once a year — how does periodic reproduction affect how we describe population growth? The female bison in the YNP herd all have calves around the same time each year — in spring from April through the beginning of June (Jones et al. 2010) — so the population size does not increase gradually, but jumps up at calving time. This type of periodic reproduction is common in nature, and very different from animals like humans, who have babies throughout the year. When scientists want to describe the growth of populations that reproduce periodically, they use geometric growth. Geometric growth is similar to exponential growth because increases in the size of the population depend on the population size (more individuals having more offspring means faster growth!), but under geometric growth timing is important: geometric growth depends on the number of individuals in the population at the beginning of each breeding season. Exponential growth and geometric growth are similar enough that over longer periods of time, exponential growth can accurately describe changes in populations that reproduce periodically (like bison) as well as those that reproduce more constantly (like humans). Photo courtesy of Guimir via Wikimedia Commons.

The power of exponential growth is worth a closer look. If you started with a single bacterium that could double every hour, exponential growth would give you 281,474,977,000,000 bacteria in just 48 hours! The YNP bison population reached a maximum of 5000 animals in 2005 (Plumb et al . 2009), but if it had continued to grow exponentially as it did between 1902 and 1915 (18% growth rate), there would be over 1.3 billion (1,300,000,000) bison in the YNP herd today. That's more than thirteen times larger than the largest population ever thought to have roamed the entire plains region!

The potential results may seem fantastic, but exponential growth appears regularly in nature. When organisms enter novel habitats and have abundant resources, as is the case for invading agricultural pests, introduced species , or during carefully managed recoveries like the American bison, their populations often experience periods of exponential growth. In the case of introduced specie s or agricultural pests, exponential population growth can lead to dramatic environmental degradation and significant expenditures to control pest species (Figure 3).

After the Boom: Limits to Growing Out of Control

Let's think about the conditions that allowed the bison population to grow between 1902 and 1915. The total number of bison in the YNP herd could have changed because of births, deaths, immigration and emigration (immigration is individuals coming in from outside the population, emigration is individuals leaving to go elsewhere). The population was isolated, so no immigration or emigration occurred, meaning only births and deaths changed the size of the population. Because the population grew, there must have been more births than deaths, right? Right, but that is a simple way of telling a more complicated story. Births exceeded deaths in the northern YNP bison herd between 1902 and 1915, allowing the population to grow, but other factors such as the age structure of the population, characteristics of the species such as lifespan and fecundity , and favorable environmental conditions, determined how much and how fast.

Changes in the factors that once allowed a population to grow can explain why growth slows or even stops. Figure 4 shows periods of growth, as well as periods of decline, in the number of YNP bison between 1901 and 2008. Growth of the northern YNP bison herd has been limited by disease and predation, habitat loss and fragmentation, human intervention, and harsh winters (Gates et al . 2010, Plumb et al . 2009), resulting in a current population that typically falls between 2500 and 5000, well below the 1.3 billion bison that continued exponential growth could have generated.

Factors that enhance or limit population growth can be divided into two categories based on how each factor is affected by the number of individuals occupying a given area — or the population's density . As population size approaches the carrying capacity of the environment, the intensity of density-dependent factors increases. For example, competition for resources, predation, and rates of infection increase with population density and can eventually limit population size. Other factors, like pollution, seasonal weather extremes, and natural disasters — hurricanes, fires, droughts, floods, and volcanic eruptions — affect populations irrespective of their density, and can limit population growth simply by severely reducing the number of individuals in the population.

The idea that uninhibited exponential growth would eventually be limited was formalized in 1838 by mathematician Pierre-Francois Verhulst. While studying how resource availability might affect human population growth, Verhulst published an equation that limits exponential growth as the size of the population increases. Verhulst's equation is commonly referred to as the logistic equation , and was rediscovered and popularized in 1920 when Pearl and Reed used it to predict population growth in the United States. Figure 5 illustrates logistic growth: the population grows exponentially under certain conditions, as the northern YNP bison herd did between 1902 and 1915, but is limited as the population increases toward the carrying capacity of its environment. Check out the article by J. Vandermeer (2010) for a more detailed explanation of the equations that describe exponential and logistic growth.

Logistic growth is commonly observed in nature as well as in the laboratory (Figure 6), but ecologists have observed that the size of many populations fluctuates over time rather than remaining constant as logistic growth predicts. Fluctuating populations generally exhibit a period of population growth followed a period of population decline, followed by another period of population growth, followed by...you get the picture.

Populations can fluctuate because of seasonal or other regular environmental cycles (e.g., daily, lunar cycles), and will also sometimes fluctuate in response to density-dependent population growth factors. For example, Elton (1924) observed that snowshoe hare and lynx populations in Canadian boreal forests fluctuated over time in a fairly regular cycle (Figure 7). More importantly, they fluctuated, one after the other, in a predictable way: when the snowshoe hare population increased, the lynx population tended to rise (plentiful food for the lynx!); when the lynx population increased, the snowshoe hare population tended to fall (lots of predation on the hare!); when the snowshoe hare...(and the cycle continues).

It is also possible for populations to decline to extinction if changing conditions cause death rates to exceed birth rates by a large enough margin or for a long enough period of time. Native species are currently declining at unprecedented rates — one important reason why scientists study population ecology. On the other hand, as seen in the YNP bison population, if new habitats or resources are made available, a population that has been declining or relatively stable over a long period of time can experience a new phase of rapid, long-term growth.

What about Human Population Growth?

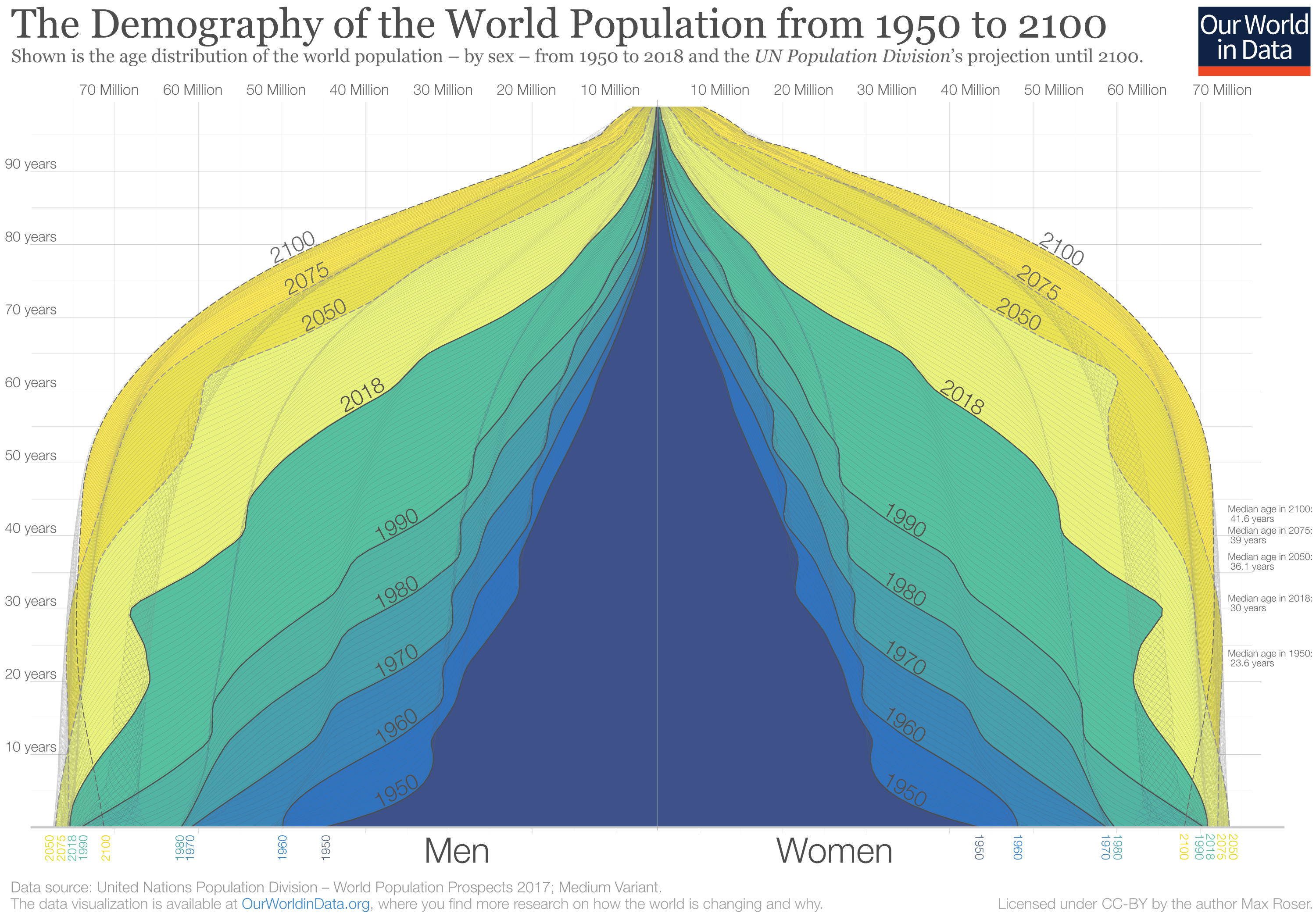

The growth of the global human population shown in Figure 8 appears exponential, but viewing population growth in different geographic regions shows that the human population is not growing the same everywhere. Some countries, particularly those in the developing world, are growing rapidly, but in other countries the human population is growing very slowly, or even contracting (Figure 9). Studying the characteristics of populations experiencing different rates of growth helps provide scientists and demographers with insight into the factors important for predicting future human population growth, but it is a complicated task: in addition to the density dependent and independent factors we discussed for the northern Yellowstone National Park bison and other organisms, human population growth is affected by cultural, economic, and social factors that determine not only how the population grows, but also the potential carrying capacity of the Earth.

biodiversity : The variety of types of organisms, habitats, and ecosystems on Earth or in a particular place.

exponential growth : Continuous increase or decrease in a population in which the rate of change is proportional to the number of individuals at any given time.

age structure : The distribution of individuals among age classes within a population.

lifespan : How long an individual lives, or how long individuals of a given species live on average .

fecundity : The rate at which an individual produces offspring.

density : Referring to a population, the number of individuals per unit area or volume; referring to a substance, the weight per unit volume.

carrying capacity : The number of individuals in a population that the resources of a habitat can support; the asymptote, or plateau, of the logistic and other sigmoid equations for population growth.

logistic equation : The mathematical expression for a particular sigmoid growth curve in which the percentage rate of increase decreases in linear fashion as the population size increases.

native species : A species that occurs in a particular region or ecosystem by natural processes, rather than by accidental or deliberate introduction by humans.

introduced species : A species that originated in a different region that becomes established in a new region, often due to deliberate or accidental release by humans.

demographers : Demography is the study of the age structure and growth rate of populations.

References and Recommended Reading

Dary, D. A. The Buffalo Book: The Full Saga of the American Animal . Chicago, IL: Swallow Press, 1989.

Elton, C. Periodic fluctuations in the numbers of animals: Their causes and effects. British Journal of Experimental Biology 2, 119-163 (1924).

Gates, C. C. et al . eds. American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010 . Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2010.

Hornaday, W. T. The Extermination of the American Bison, With a Sketch of its Discovery and Life History . Annual Report 1887. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1889.

Jones, J. D. et al . Timing of parturition events in Yellowstone bison Bison bison : Implications for bison conservation and brucellosis transmission risk to cattle. Wildlife Biology 16, 333-339 (2010).

Livingston, M., Osteen, C. & Roberts, D. Regulating agricultural imports to keep out foreign pests and disease. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Amber Waves 6, " http://www.ers.usda.gov/AmberWaves/September08/Features/RegulatingAgImports.htm " (2008).

Pearl, R. & Reed, L. J. On the rate of growth of the population of the United States since 1790 and its mathematical representation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 6, 275-288 (1920).

Plumb, G. E. et al . Carrying capacity, migration, and dispersal in Yellowstone bison. Biological Conservation 142, 2377-2387 (2009).

Rohrbaugh, R., Lammertink, M. & Piorkowski, M. Final Report: 2007 - 08 Surveys for Ivory-Billed Woodpecker and Bird Counts in Louisiana . Ithaca, NY: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 2009.

Shaw, J. H. How many bison originally populated western rangelands? Rangelands 17, 148-150 (1995).

Vandermeer, J. How Populations Grow: The Exponential and Logistic Equations. Nature Education Knowledge 1 (2010).

Flag Inappropriate

Email your Friend

- | Lead Editor:

Within this Subject (22)

- Basic (12)

- Intermediate (5)

- Advanced (5)

Other Topic Rooms

- Ecosystem Ecology

- Physiological Ecology

- Population Ecology

- Community Ecology

- Global and Regional Ecology

- Conservation and Restoration

- Animal Behavior

- Teach Ecology

- Earth's Climate: Past, Present, and Future

- Terrestrial Geosystems

- Marine Geosystems

- Scientific Underpinnings

- Paleontology and Primate Evolution

- Human Fossil Record

- The Living Primates

© 2014 Nature Education

- Press Room |

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Notice |

Visual Browse

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- China CDC Wkly

- v.3(28); 2021 Jul 9

Major Trends in Population Growth Around the World

1 United Nations Population Division, New York, USA

Kirill Andreev

Matthew e. dupre.

2 Department of Population Health Sciences & Department of Sociology, Duke University, North Carolina, USA

The world’s population continues to grow, albeit at a slower pace. The decelerating growth is mainly attributable to fertility declines in a growing number of countries. However, there are substantial variations in the future trends of populations across regions and countries, with sub-Saharan African countries being projected to have most of the increase. Population momentum plays an important role in determining the future population growth in many countries and areas where fertility is in a rapid transition. With declines in fertility, the world’s population is unprecedentedly aging, and the numbers of households with smaller sizes are growing. International migration is also on the rise since the beginning of this century. The world’s population is also urbanizing due to increased internal rural to urban migration. Nevertheless, there are uncertainties in future population growth, not only because there are uncertainties in the future trends in fertility, mortality, and migration, but also because there are many other factors that could affect these trajectories. International consensus on climate change and ecosystem protections may trigger population control policies, and the ongoing pandemic is likely to have some impact on mortality, migration, or even fertility.

The future trend of a population is an outcome of the interactive dynamics between its existing age structure and its future trends in fertility, mortality, and migration. An abundance of scientific evidence shows that population growth in a country is connected to socioeconomic growth, environmental protection, health promotion, quality of life, and social stability. Understanding the growth dynamics and future trends of populations around the world is crucial to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other long-term development goals. This article reviews the main features of recent and future trends in population growth for the world, major regions, and selected countries. We mainly rely on the estimates and projections of the 2019 Revision of the World Population Prospects (WPP 2019) produced by the United Nations Population Division ( 1 ) to focus on 201 countries and areas with 90,000 inhabitants or more in mid-2020.

MAJOR TRENDS IN POPULATION GROWTH

Continuing gowth of the world population at a slowing pace.

The world’s population continues to grow, reaching 7.8 billion by mid-2020, rising from 7 billion in 2010, 6 billion in 1998, and 5 billion in 1986. The average annual growth rate was around 1.1% in 2015–2020, which steadily decreased after it peaked at 2.3% in the late 1960s. Among 201 countries and areas, 73 countries had a smaller growth rate in 2010–2020 compared with the previous decade; and out of these 73 countries, more than 60 are developing countries. The slowing pace of the population growth is closely related to declines in fertility. Globally, the total fertility rate was 2.4 births per woman of reproductive age in 2020, decreasing from 2.7 in 2000, 3.7 in 1980, and 5.0 in 1950. In high-income and upper-middle-income countries, the total fertility rate has been below replacement level (2.1 births per woman) for a few decades, which is the level required to ensure the replacement of generations in low-mortality countries. In a few of these countries, total fertility rates have even fallen to extremely low levels, 1.5 births per woman, and even below 1.5 in some countries, for the past several decades.

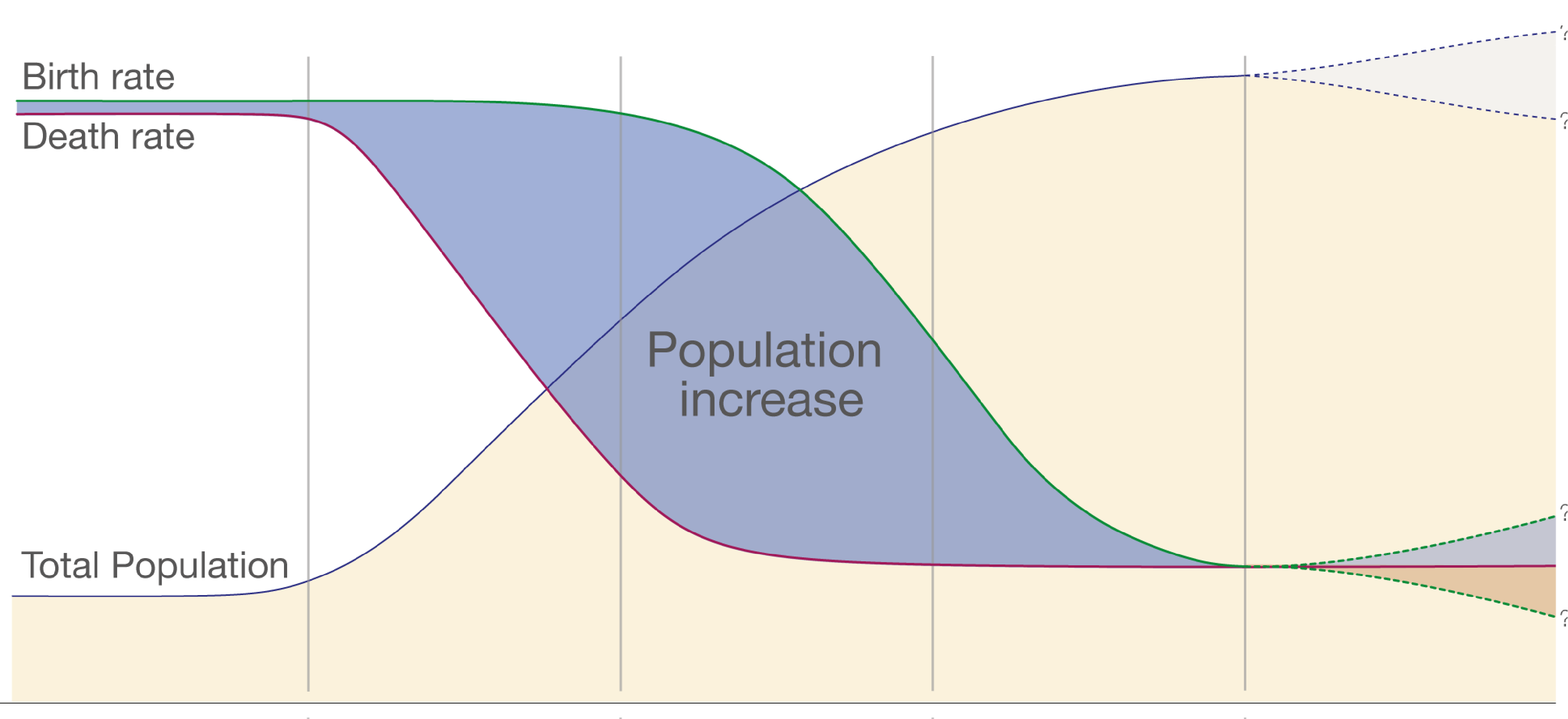

There is a myriad of reasons for the slowing pace of population growth that can be attributed to declining fertility in the context of a demographic transition mainly caused by modernization. In the process of modernization, improved food security, nutrition, and public health, advances in medical technology and socioeconomic development, coupled with improved safe and effective family planning methods and services have largely improved child survival, which has enabled couples to have a desired number of children without having too many births. Improved education, enhanced women’s empowerment, increased financial security in old age, and personal aspirations for more opportunities regarding self-career development and a better life have all reshaped young couples’ views and behaviors about postponements of marriage and childbearing, and the numbers and timing of childbirths ( 2 - 3 ). All of these forces have led to reductions in fertility, and eventually triggered a demographic transition. By 2020, all countries and areas either have completed their demographic transition or are in the middle of the transition.

However, even if fertility levels declined rapidly, the world population would likely continue to grow because of the momentum of population growth — a force that drives future population growth resulting from the existing age structure. Globally, more than two-thirds of the projected increase of 1.9 billion in population from 2020 to 2050 could be attributable to population momentum. In other words, population momentum is projected to produce 1.3 billion more people between 2020 and 2050, or 17% of the total in 2020. The contributions of above-replacement level fertility and declining mortality to the projected increase in 2020–2050 are 317 million (16% of the total increase) and 295 million (15%), respectively. The increases attributable to above-replacement level fertility and mortality are roughly equal to 4% each of the total in 2020.

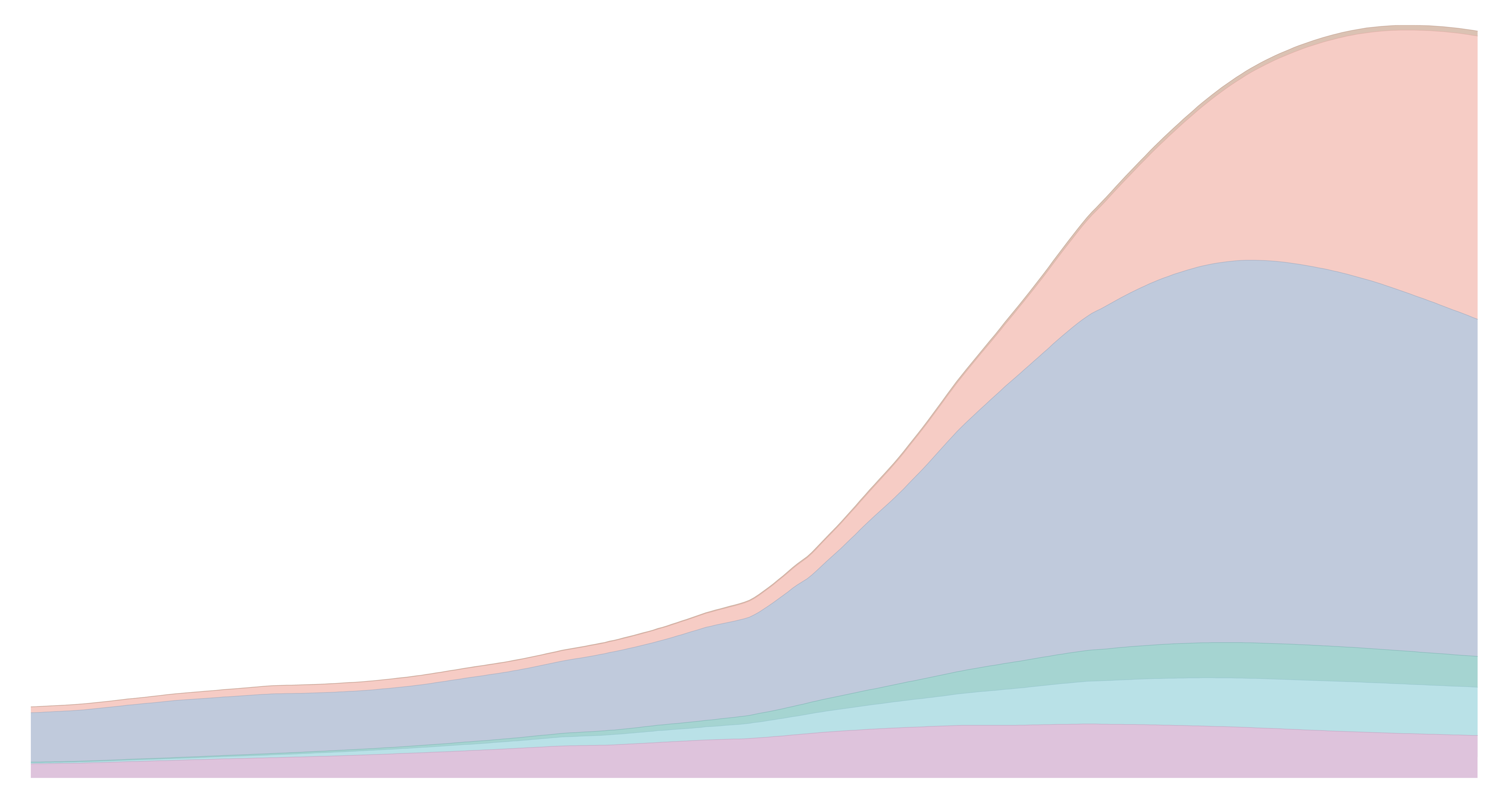

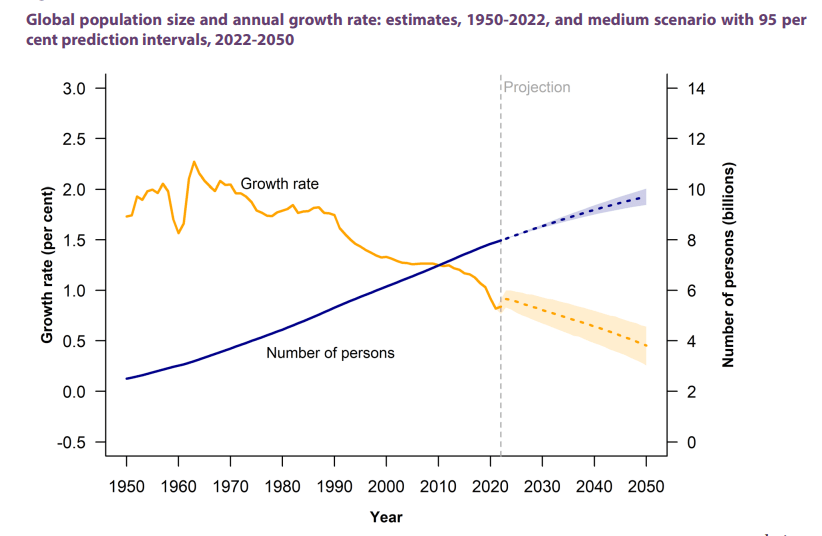

Although the growing trend in the world population is expected to continue throughout this century at a slowing pace, there is uncertainty about future trends, and the uncertainty gets wider with time. For example, the world population is projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 and 10.9 billion by 2100, but their 95% projection intervals could be between 9.4 and 10.1 billion for 2050 and between 9.4 and 12.7 billion for 2100 ( Figure 1 ).

Growth of the world population, 1950–2100.

Note: The solid blue line is an estimate, whereas the dotted blue line is a projection under the medium variant and the shadow is the 95% projection intervals. Source: Drawn from the World Population Prospects 2019 ( 1 ).

Large Variations in Growth Patterns Across Regions and Countries

There are substantial variations in the future trends of populations across regions and countries. Overall, most countries and areas in the world are projected to continue growing in 2020–2050. However, in the second half of the century, more than half of the countries and areas are projected to witness a decline. Among eight SDG regions, sub-Saharan Africa is expected to account for most of the increase in the world’s population throughout the century, and its global share of the population is projected to increase steadily. By contrast, the global shares of the population by other SDG regions are projected to decrease over time. Globally, there are 54 countries which have an annual growth rate twice as fast as the world average rate in 2020–2050, and 41 of these countries, or slightly more than three-fourths, are located in sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed, more than a half of the global additional 2.0 billion people projected increase between 2020 and 2050 are from countries in sub-Saharan Africa (regardless of scenarios), and such a proportion is projected to be about 90% in 2050–2100. Overall, about 23–38 million more people annually from sub-Saharan countries are projected to be added to the world’s total population. As a result, the current total population of sub-Saharan African countries, which was 1.1 billion in 2020 (or similar to the Europe and Northern America combined), is projected to climb to 3.8 billion by 2100 with a 95% projection interval between 3.0 and 4.8 billion. By contrast, the total population of Europe and Northern America combined will maintain its current level by 2100 ( Figure 2 ).

Population growth by Sustainable Development Goals region, 1950–2100.

*: excluding Australia and New Zealand. Note: The solid color lines are estimates, whereas the dotted color lines are projections under the medium variant and the color shadows are the 95% projection intervals. Source: Drawn from the World Population Prospects 2019 ( 1 ).

Although a fast-growing population in some developing countries provides a large young population base, which could be a favorable factor for economic growth when this young population enters the labor force, these countries are facing challenges associated with a large young population, such as low access to education among children (especially among girls), relatively high levels of infant, child, and maternal mortality, and relatively high unmet needs in family planning services. High fertility has also caused young couples to have unwanted pregnancies and births that otherwise could relieve them of childbearing and childrearing obligations for other opportunities of human development ( 2 ).

Another major feature of the world’s future population growth is that the majority of the projected increase in the world’s total population is attributed to a very few populous (or fast growing) countries. For example, under the medium variant of WPP 2019, nine countries (India, United States, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Egypt, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the United Republic of Tanzania) are projected to account for more than half of the increase in global population between 2020 and 2050. Except for the United States, all are developing countries and are low-income or low-middle-income countries. Low education among children, high fertility levels, high maternal mortality, and high unmet needs in family planning services in many of these countries are major obstacles for achieving SDGs ( 4 ).

In contrast to most countries where populations are projected to increase in 2020–2050, populations in some countries are projected to decline. There were 18 countries and areas, mostly in Europe, that had a negative population growth rate in the last 3 decades (1990–2020), and the number of countries and areas with a negative growth rate is projected to reach 46 in the next 3 decades (2020–2050), including several Asian countries. Almost all countries in Latin American and the Caribbean are projected to continue to grow in 2020–2050, but many of them are projected to be on a declining track in 2050–2100.

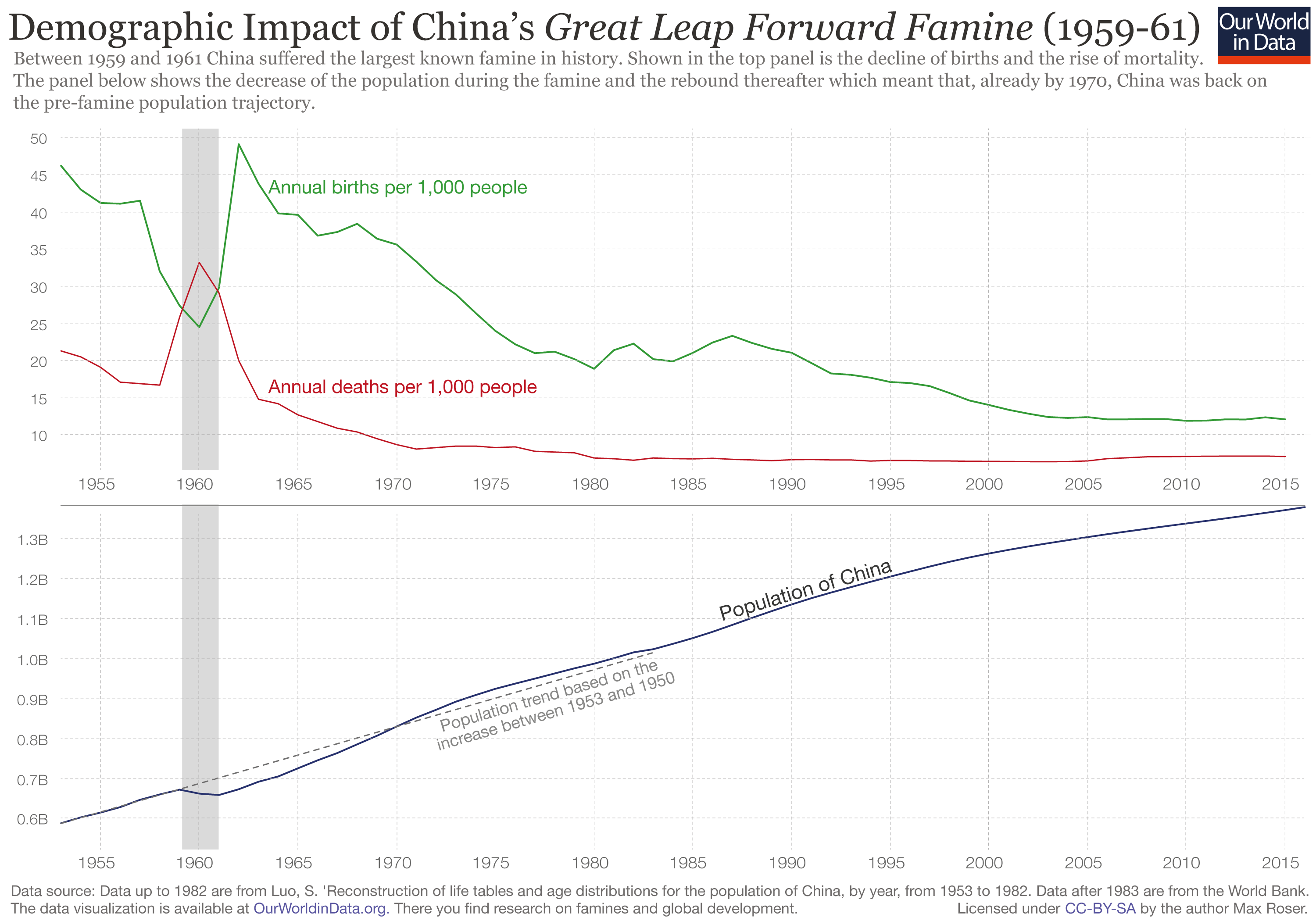

China, the most populated country in the contemporary world, had a total population of 1.43 billion in 2020 and was a major contributor to the world’s population growth over the past several decades. Under the medium variant of WPP 2019 ( Figure 3 ), China is projected to have some loss in its total population, with 1.40 billion by 2050, after peaking at 1.46 billion around 2030. Japan has seen the largest losses in population size since the beginning of this century; however, China is projected to eclipse this and will become the largest country with a decreasing population (of 30 million by 2050). By 2100, China is projected to have a loss of more than a quarter of its current size. For India, the world’s second most populous country in the contemporary world, it is projected to continue to grow and will overtake China as the largest population in 2025–2030, reaching 1.64 billion by 2050. However, India is projected to witness population decline after reaching its peak around 1.65 billion in 2055–2060 due to falling fertility. By 2100, India is projected to reach 1.45 billion and to have the second largest loss in population in 2050–2100 after China, followed by Brazil and Bangladesh, ranking the third and fourth largest losses in population, respectively.

Population growth for selected populous countries, 1950–2100.

Note: The solid color lines are estimates, whereas the dotted color lines are projections under the medium variant and color shadows are the 95% projection intervals. Source: Drawn from the World Population Prospects 2019 ( 1 ).

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that there is uncertainty in the future growth of populations and the uncertainty gets wider in the more distant future. For example, the 95% projected low and high bounds for China could be 1.32 to 1.50 billion by 2050, and 0.82 to 1.33 billion by 2100, respectively. The corresponding figures for India are 1.47 to 1.81 billion by 2050, and 8.87 to 2.18 billion by 2100 ( Figure 3 ).

Contributions of Population Momentum, Fertility, and Mortality to Population Growth

Future population growth depends on population momentum, future fertility, mortality, and migration trends. The population momentum refers to an inherent driving force for population growth resulted from the existing age structure. A young age structure leads to increases in population even if fertility is kept constantly at replacement level, whereas an older age structure could lead slower growth or even decreases in population ( 5 ).

There is a large variation in the contribution of these components to future population growth for individual countries and regions. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, relative to the total population in 2020, the total increase in population due to population momentum between 2020 and 2050 is projected to be equal to 40% of the 2020 total; the increase in population due to higher fertility (above replacement level) is projected to be equal to 53% of the 2020 total. The contributions by mortality and migration are very small. In Europe, both low fertility and population momentum are projected to cause population losses between 2020 and 2050. Although improvements in mortality and increasing migration are projected to offset some of the population losses in this period, the overall trend in population size is projected to decline. In Northern America, the population is expected to continue to grow in 2020–2050 largely fueled by declines in mortality and positive net migration, and, to a lesser extent, by positive population momentum. This growth is expected to be partially dampened by the negative contribution of low fertility.

In Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, the increases in population between 2020 and 2050 due to population momentum and improved mortality are projected to be equal to 5% and 3% of its current total, respectively; whereas low fertility in the regions is projected to bring negative population growth by 5% of its current total. The contribution of migration is negligible. Trends in China are similar to this regional pattern, although the actual levels are somewhat different. In Japan, however, the overall pattern is close to that of Europe rather than that of their geographical region.

In Central and Southern Asia, while fertility is projected to bring zero growth to the future population, population momentum is projected to add one-quarter of its population to the current total. The contributions of mortality and migration in this region are negligible. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the increases in population are driven mostly by population momentum, with an additional (although small) contribution of improved mortality. Fertility is projected to contribute significantly to population decline, about 5% of the current population size.

Unprecedented Challenges of Population Aging in Many Countries

With progress along the demographic transition, coupled with other societal developments, most countries have experienced declining fertility and improved mortality, marked by the elimination/reduction of many fatal infectious diseases that have prolonged life expectancy. Global life expectancy at birth has reached 73 years in 2020, 7 years more than that in 2000, and nearly 30 years more than that in 1950. It has been documented that life expectancy at birth for the best performing countries in history have witnessed an increase of 2.0–2.5 years per decade over the last few centuries ( 4 ). It is now projected that global life expectancy at birth will reach 77 years by 2050 and 82 years by 2100. Life expectancy at birth could even be over 95 years by 2100 in Japan, Republic of Korea, Singapore, and Spain, although it is projected to remain below 80 years in some African countries.

Paralleling the unprecedented rise in life expectancy is the unprecedented growth of population aging ( 6 ). A population is typically considered an aging population if the proportion of its adults aged 65 or older (or old-age proportion) is over 7%. Likewise, it is called an aged, a super-aged, and an ultra-aged population if the old-age proportion is over 14%, 21%, and 28%, respectively ( 7 ). Globally, the proportion of people aged 65 or older reached 9.3% in 2020, rising from 6.9% in 2000, and 5.1% in 1950 ( Table 1 ). The global old-age proportion is projected to reach 15.9% in 2050 and 22.4% in 2100.

| Note: The distributions are calculated among 201 countries and areas. The old-age percentages refer to the proportion shared by the population aged 65 or older out of the total population. | |||||

| Levels | |||||

| <7 | 76.6 | 66.2 | 49.7 | 22.9 | 0.0 |

| 7–14 | 23.4 | 22.4 | 21.4 | 19.4 | 13.4 |

| 14–21 | 0.0 | 11.4 | 23.9 | 20.4 | 15.9 |

| 21–28 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 22.4 | 19.5 |

| ≥28 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 14.9 | 51.2 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| The world | 5.1 | 6.9 | 9.3 | 15.9 | 22.4 |

In some developed countries (or countries with rapid fertility declines), the proportion of older people is much higher. For example, the old-age proportion in Japan, the most aged population in the contemporary world, was 28.4% in 2020, rising from 17.0% in 2000, and 4.9% in 1950. Table 1 shows that by 2050, nearly 58% of the 201 countries are projected to be in an aged society, and nearly 15% of these countries are projected to be in an ultra-aged society; in comparison to the less than 30% of countries in an aged society in 2020 and only one country in an ultra-aged society (Japan). By 2100, nearly 90% of these countries are projected to be an aged society, and more than half are project to be an ultra-aged society.

Population aging has had a profound impact on old-age care, pension and social security systems, housing, savings, labor supplies, social services, and in many other sectors ( 6 ). These challenges are more pressing for developing countries because they are facing these challenges within a much shorter time frame, and long before they become economically well off, to prepare for such rapid population aging (“aging before rich”). With few exceptions (e.g., Japan), most developed countries took 40 to 120 years to transform from an aging population (7%) to an aged population (14%) and took (or will take) 20 to 50 years to transform from an aged society (14%) to a super-aged society (21%). In contrast, most developing countries will take 15–35 years to transform from an aging population to an aged population and 10–30 years to transform from an aged population to a super-aged population. Based on some empirical evidence, and potential trajectories of mortality and fertility, it is projected that the number of years to transform from a super-aged population into an ultra-aged population will be shorter than the number of years transforming from an aged society to a super-aged society for both developed and developing countries. Such an unprecedented growth of older populations in the world has required reforms in pension systems and statutory retirement ages in many countries, especially in more developed countries in order to maintain fiscal sustainability of existing public pension systems ( 8 ).

However, rapid population aging can also open additional windows of opportunity for economic growth — such as a “second economic dividend” when low fertility and prolonged longevity stimulate human capital investments ( 9 ). This is especially the case when population aging is accompanied by better health (i.e., “compression of morbidity”) that has been observed in many older populations ( 10 ). Better health and prolonged longevity could allow labor force participation among older adults to offset downward pressures on economic growth ( 6 ). Research has shown that the benefits of a second dividend are estimated to be larger and more lasting than the first dividend ( 9 ), leaving policymakers an opportunity to optimize transitory economic growth from the first dividend into a sustained one.

Growing Role of International Migration

It is estimated that the number of persons who live outside of their countries of birth reached 281 million in 2020 globally, an increase from 108 million over the amount in 2000 ( 11 ). Although international migration does not have a direct impact on the world’s population growth, and its impact on population growth is usually negligible in most countries compared to other demographic components, it has contributed significantly to the growth of populations in some countries. For example, in the past few decades, international labor migration inflows in several Gulf States have contributed to rapid population growth in these countries. It was estimated that labor immigrants accounted for more than three-fourths of the working-age population in Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, and Qatar in the last couple of decades.

Globally, about two-thirds of international migrants are concentrated in just 20 countries — with the United States as the largest destination country, followed by Germany, Saudi Arabia, the Russian Federation, and the United Kingdom, which all have over 10 million immigrants. On the other hand, about one-third of all global migrants originated in only 10 countries — with India as the largest out-migration country, followed by Mexico, China, and the Russian Federation, which have over 10 million emigrants. Overall, high-income countries host nearly two-thirds of all international migrants, and Europe continues to host the largest number of migrants in the world, followed by Northern America. The number of male international migrants is slightly higher than that of female migrants. Most international migration is for labor or family reasons. However, the number of forcibly displaced migrants due to humanitarian crises in many parts of the world grew rapidly, reaching 34 million in 2020, an increase from 17 million compared with 2000 ( 11 ).

Migration can contribute to sustainable development in both origin and destination countries, which has been widely acknowledged in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration ( 11 ). As most migrants are working-age adults, positive net migration can also offset a shortage of labor supply and population decline, as well as slow down population aging in destination countries. For countries and areas of origin, as migrants are mostly healthy, highly educated, and skilled young adults, a large scale of out-migration may cause possible brain drains and accelerate population aging. However, migrants’ remittances to countries and areas of origin could improve the livelihood and education of population left behind, boost socioeconomic development, and reduce mortality. All these promote sustainable development in origin countries and areas ( 11 ). Nevertheless, as migrants often face many disadvantages — including language barriers, low social integration and isolation, and a low likelihood of being eligible for pensions, healthcare, and/or education compared with those who are native born — how to better protect their rights and remove obstacles that prevent them from discrimination is a key goal for achieving SDGs and leaving no one behind.

An Urbanizing World

Urbanization, usually measured by the percentage urban (i.e., urban population as a percentage of the total population), is the spatial re-distribution of the population of a country or an area, mainly resulting from internal or domestic migration. Given the close relationships among urbanization, socioeconomic development, and the environment, it is crucial to understand the long-term trends in urbanization in addition to the trends in population size and composition. Just like international migration will not change the world’s population, internal or domestic migration within a country will not change the population of that country. However, internal migration, especially rural-to-urban migration can have a huge impact on the total population in both the origin and destination cities of a given country, which is normally a major driving force for rapid urbanization, such as in the case of China ( 12 ).

The world’s population is urbanizing rapidly. The percentage urban was 56% in 2020, rising from 50% in 2007, 43% in 1990, and less than 30% in 1950 ( Table 2 ). It is projected to reach more than 68% in 2050 ( 13 ). There are large variations in urbanization levels and growth rates across regions and countries, with the percentage urban more than 80% in Northern America and, Latin America and the Caribbean, 75% in Europe, and around 40% in sub-Saharan Africa in 2020. From 2000 to 2020, with the exception of a very few countries, all other countries witnessed an increase in urbanization — with nearly 40 countries having an annual growth rate greater at 1.5%; and all countries are projected to continue to urbanize from 2020 to 2050, albeit with different annual growth rates ranging from 0.01% to over 2.0%. Most developing countries are projected to have a much faster growth rate than developed countries. China has been the biggest contributor to global urbanization from 2000 to 2020, thanks to its massive scale of rural-to-urban migration. From 2020 to 2050, China is projected to continue to play a major role in global urbanization, although India will overtake China as the largest contributor. Nigeria is projected to be the third largest contributor to the world’s urbanization growth in the next three decades ( 13 ).

| Note: The distributions are calculated among 201 countries and areas. The percentage urban refers to the proportion shared by the urban population out of the total population. Source: United Nations (2018) ( ). | ||||

| Levels | ||||

| <20 | 38.3 | 7.5 | 4.0 | 0.0 |

| 20–30 | 18.9 | 12.4 | 9.0 | 3.5 |

| 30–50 | 22.4 | 23.4 | 19.9 | 12.9 |

| 50–70 | 13.9 | 27.4 | 28.9 | 24.9 |

| ≥70 | 6.5 | 29.4 | 38.3 | 58.7 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| By selected regions | ||||

| World | 29.6 | 46.7 | 56.2 | 68.4 |

| More developed regions | 54.8 | 74.2 | 79.1 | 86.6 |

| Less developed regions | 17.7 | 40.1 | 51.7 | 65.6 |

| Europe | 51.7 | 71.1 | 74.9 | 83.7 |

| Northern America | 63.9 | 79.1 | 82.6 | 89.0 |

| Australia/New Zealand | 76.2 | 84.5 | 86.3 | 91.0 |

| Latin American and the Caribbean | 41.3 | 75.5 | 81.2 | 87.8 |

| South-Eastern Asia | 15.6 | 37.9 | 50.0 | 66.0 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 11.1 | 31.4 | 41.4 | 58.1 |

Fast Growing Numbers of Households with Decreasing Size

All human beings are connected to others by blood or marriage, and generally live together in families or households. Dynamic changes in household size and composition over time are indeed another form of population growth. Households are often a more relevant unit for analyzing energy-related consumption, human impacts on the environment, and likewise sustainable development because energy-related commodities such as water, food, vehicles, housing, and social services are often purchased and consumed by households, rather than by individuals ( 14 - 15 ). There is ample empirical evidence showing that the average size of households has declined steadily over the past several decades for most countries in the world ( 16 ). For example, in Brazil, the average household size declined from 5.1 persons per household in 1960 to 3.3 persons per household in 2010. The corresponding figures were 3.8 and 3.2 for the United Kingdom, and 3.5 and 2.6 for the United States. The average household size for India also declined from 5.8 persons per household in 1980 to around 4.5 persons per household in 2010. China’s household size decreased from 4.7 in 1981 to 3.2 in 2010, and further down to 2.62 in 2020 ( 17 ).

Such decreases in household size have led to faster growth in the number of households as compared to the growth of the population ( 18 ). The faster growth of households will likely persist in the foreseeable future. Globally, the average household size for all countries was around 4 persons per household in 2010, ranging from 2.1 in Finland and Germany to 8 persons per household in Afghanistan ( 16 ). It was estimated that if the average household size had been 2.5 people globally in 2010, the number of households in the world would be 2.7 billion, 0.8 billion more (or a 41% increase) than the current total of 1.9 billion ( 14 ). In addition to declining fertility, higher divorce rates, more internal and international migration, and the diminishing norms of co-residence have all contributed to the growth of smaller household sizes ( 16 ).

The living arrangements of older adults is an important component of household composition, which have been receiving increasing attention. The living arrangements of older adults are the result of a nexus of personal preferences, needs, available resources, and culture. Coresidence with adult children and/or grandchildren is very common in many countries and areas in Asia, Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean, where coresidence is usually over 40% (and even reaches over 80% in some countries). In contrast, coresidence is relatively low among older adults in Europe and Northern America, where the most common living arrangement of older adults is living with a spouse only or living alone ( 19 ). With the progress of modernization and advances in socioeconomic development, the number of older adults in many developing countries preferring to live with their spouses only and/or live alone is growing in most countries. In China, for instance, the percentage of those living with only a spouse or alone witnessed a steady increase over the last several decades, from 25% in 1982 to 35% in 2010 ( 20 - 21 ). Research has shown that the living arrangement of older adults is linked to various health outcomes and the use of (in)formal services; which implies that the fast growing trend in the numbers of households coupled with its reducing size could have important implications for the planning of long-term care, housing, and social services in the context of rapid population aging.

Overall, the trends in household size and composition and older adult living arrangements are important for sustainable development, especially when such trends are connected with energy-related consumption and old-age care.

The world’s population is projected to continue to grow at a slowing pace during this century. Such a trend of decelerating growth is mainly due to fertility declines in a growing number of countries. However, many sub-Saharan African countries are projected to have much faster growth than countries in other regions of the world — because many sub-Saharan African countries still have high fertility rates and reductions in fertility have been stalling in recent years. In these countries, more effort is needed to prioritize the enhancement and empowerment of women, improve the availability of safe and effective methods of contraception, promote compulsory education among children, and reduce poverty.

Rapid and sustained declines in fertility could result in a large labor force relative to the number of children and older people in some period(s), creating a window of opportunity for socioeconomic growth, commonly known as the “first demographic dividend (population bonus)” ( 9 ). With progress along the demographic transition in a country, the young bulk of the labor force enters the late stages of the labor force. This leads to higher per capita consumption due to this population’s greater resources, and eventually creating another window of opportunity for economic growth in that country, or the “second demographic dividend” ( 9 ). Most developing countries are (or will be) in their first window of opportunity, and many developed countries are (or will be) in their second window of opportunity.

However, it should be emphasized that the demographic dividends are opportunities for economic growth and should not be taken for granted. The duration of each window of opportunity is limited and does not last forever. Instead, the realization of demographic dividends depends on appropriate policies adopted in other related sectors and the country’s ability to implement these policies ( 22 ). Research has shown that female labor force participation, educational attainment of the labor force, the potentiality of the old-age population entering the workforce, people's health and wellbeing, urbanization, investments (especially foreign direct invests), high technology, and international trades are all important factors determining the outcomes of demographic dividends ( 22 ). It is thus important for different countries to formulate socioeconomic policy packages that are consistent with their own population trends and characteristics to reap the maximum benefits of the demographic dividends. For countries in the first (window) stage, promoting quality education, enhancing women’s empowerment, creating more jobs, and attracting more foreign direct investments may be a priority. For aging countries, especially aged and super-aged countries, postponing the retirement age, developing a sound long-term care system, promoting home- and community-based social services, and creating social environments without ageism are effective solutions to ensure that all adults achieve healthy aging and age in the right place. However, it is also worth noting that with prolonged life expectancy and improvements in the health of all people, the threshold of old age will likely increase, which means the size, the length, and the timing of these (window) periods could be prolonged.

Nevertheless, there are uncertainties in future population growth, not only because there are uncertainties in the future trends for the three demographic components (fertility, mortality, and migration), but also because many other factors can affect a population’s future trajectories. For example, the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has impacted almost every nation and profoundly affected every member of a society. By mid-2021, the pandemic has caused more than 3.8 million deaths worldwide — with older people being the hardest hit. The excess deaths across countries range from 5 deaths per million population to more than 1,000 deaths per million population in the past 1.5 years. The lockdown policies implemented in most countries have greatly reduced both internal and international migration; and it may take years to reach pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels. For the pandemic’s impact on fertility, it is too early to draw any reliable conclusions at this point. Some evidence suggests that there is an increase in child marriages and adolescent fertility, yet evidence in some countries shows a decrease in fertility in 2020, the first year of the pandemic. Based on historical evidence, we would expect a relatively high level of fertility in the post-disaster or post-pandemic period ( 23 ). The future trends in population growth of a country are also affected by the birth policies of a country. China recently relaxed its birth policies to allow couples to have up to three children ( 24 ). Given its large share of the world’s population, such a relaxation in its birth policy will not only influence China’s own population growth in the future, but also influence the trajectory of the world’s population.

In analyzing future population growth, it is crucial to consider the trends in the size and composition of households. With trends toward smaller households in the near future, how to transform our consumption behaviors to ensure a responsible and sustainable consumption pattern towards achieving SDG should be a priority ( 16 ). Furthermore, given the global trends in urbanization, policies to manage urban growth are needed to ensure equal access to housing, education, healthcare, decent jobs, and friendly living and working environments — with a focus on the needs of the urban poor and other vulnerable groups — so that the benefits of urbanization can be shared by all.

Climate change and environmental degradation are major global concerns in the contemporary world. There is a consensus that population growth, urbanization, unsustainable consumption patterns are important drivers of emissions that have been a cause of the worsening climate and ecosystem ( 25 ). Rapid population growth is one of the key drivers of growing emissions and one of the determinants of vulnerability to its impact ( 2 ). Consequently, slowing population growth could be key to lessen climate risks facing human beings by reducing global emissions in the long-term and by freeing up resources for adaptation ( 2 ).

In summary, the world’s population is projected to grow throughout the century, albeit at a decreasing rate. Given large variations in population trends across countries, different countries should develop sound policies specific to their own situation to scientifically address the unique challenges related to population growth for achieving SDGs and other long-term socioeconomic development goals.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the United Nations or Duke University.

Conflicts of interest : No conflicts of interest.

Essay on Population Growth for Students and Children

500+ words essay on population growth.

There are currently 7.7 billion people on our planet. India itself has a population of 1.3 billion people. And the population of the world is rising steadily year on year. This increase in the population, i.e. the number of people inhabiting our planet is what we call population growth. In this essay on population growth, we will see the reasons and the effects of this phenomenon on our planet and our societies.

One important feature of population growth is that over the last century it has shown exponential growth. When the pattern of increase is by a fixed quantity, we call this linear growth, for example, 3, 5, 7, 9 and so on. Exponential growth shows an increase by a fixed percentage, for example, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 and so on. This exponential growth is the reason our population has seen such an immense increase over the past century and a half.

Causes of Population Growth

To fully understand the phenomenon, in this essay on population growth we will discuss some of its causes. Understanding the reasons for such exponential growth will help us better understand how to plan for the future. So let us begin with one of the main causes, which is the decline in the mortality rate.

Over the last century, we have made some very significant and notable advancements in medicine, science, and technology. We have invented vaccines, found new treatments and even almost completely eradicated some life-threatening diseases. This means that people now have a much higher life expectancy than their ancestors.

Along with the decrease in mortality rate, these advancements in medicine and science have also boosted the birth rates. We now have ways to help those with infertility and reproductive problems. Hence, birth rates around the world have also seen massive improvements. This coupled with slowing mortality rates has caused overpopulation.

Often the lack of proper education is also stated as the culprit of rampant overpopulation. People around the world need to be made aware of the ill-effects of global overpopulation. Values of family planning and sustainable growth needs to be instilled not only in children but adults also. The lack of this awareness and education is one of the reasons for this growth in population.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Effects of Population Growth

This exponential population growth that our planet has experienced over the last 150 years has had some severe negative effects. The most obvious and common impact is that overpopulation has put a great strain on the natural resources of the earth. As we know, some of the resources available to us come in limited quantities, for example, fossil fuels. When the population explosion happened, these resources are becoming rarer and will one day run out completely.

The increased population had also lead to increased pollution and industrialization . This has adversely affected our natural environment leading to more health problems in the majority of the population. And as the population keeps growing, the poorer countries are running out of food and other resources causing famines and various such disasters.

And as we are currently noticing in India, overpopulation also leads to massive unemployment. Overall the economic and financial condition of densely populated regions deteriorates due to the population explosion.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Population Growth

Explore global and country data on population growth, demography, and how this is changing.

By: Hannah Ritchie , Lucas Rodés-Guirao , Edouard Mathieu , Marcel Gerber , Esteban Ortiz-Ospina , Joe Hasell and Max Roser

Population growth is one of the most important topics we cover at Our World in Data .

For most of human history, the global population was a tiny fraction of what it is today. Over the last few centuries, the human population has gone through an extraordinary change. In 1800, there were one billion people. Today there are more than 8 billion of us.

But after a period of very fast population growth, demographers expect the world population to peak by the end of this century.

On this page, you will find all of our data, charts, and writing on changes in population growth. This includes how populations are distributed worldwide, how this has changed, and what demographers expect for the future.

Key insights on Population Growth

Population cartograms show us where the world’s people are.

Geographical maps show us where the world's landmasses are; not where people are. That means they don't always give us an accurate picture of how global living standards are changing.

One way to understand the distribution of people worldwide is to redraw the world map – not based on the area but according to population.

This is shown here as a population cartogram : a geographical presentation of the world where the size of countries is not drawn according to the distribution of land but by the distribution of people. It’s shown for the year 2018.

As the population size rather than the territory is shown in this map, you can see some significant differences when you compare it to the standard geographical map we’re most familiar with.

Small countries with a high population density increase in size in this cartogram relative to the world maps we are used to – look at Bangladesh, Taiwan, or the Netherlands. Large countries with a small population shrink in size – look for Canada, Mongolia, Australia, or Russia.

You can find more details on this cartogram in our article about it:

The map we need if we want to think about how global living conditions are changing

By showing us where the people in the world are, cartograms help us understand global living conditions better.

What you should know about this data

- This map is based on the United Nation’s 2017 World Population Prospects report. Our interactive charts show population data from the most recent UN revision. This means there may be minor differences between the figures shown on the map and the latest estimates in our other charts.

The world population has increased rapidly over the last few centuries

The speed of global population growth over the last few centuries has been staggering. For most of human history, the world population was well under one million. 1

As recently as 12,000 years ago, there were only 4 million people worldwide.

The chart shows the rapid increase in the global population since 1700.

The one-billion mark wasn’t broken until the early 1800s. It was only a century ago that there were 2 billion people.

Since then, the global population has quadrupled to eight billion.

Around 108 billion people have ever lived on our planet. This means that today’s population size makes up 6.5% of the total number of people ever born. 2

This increase has been the result of advances in living conditions and health that reduced death rates – especially in children – and increases in life expectancy.

See the data in our interactive visualization

- This data comes from a combination of sources, all detailed in our sources article for our long-term population dataset.

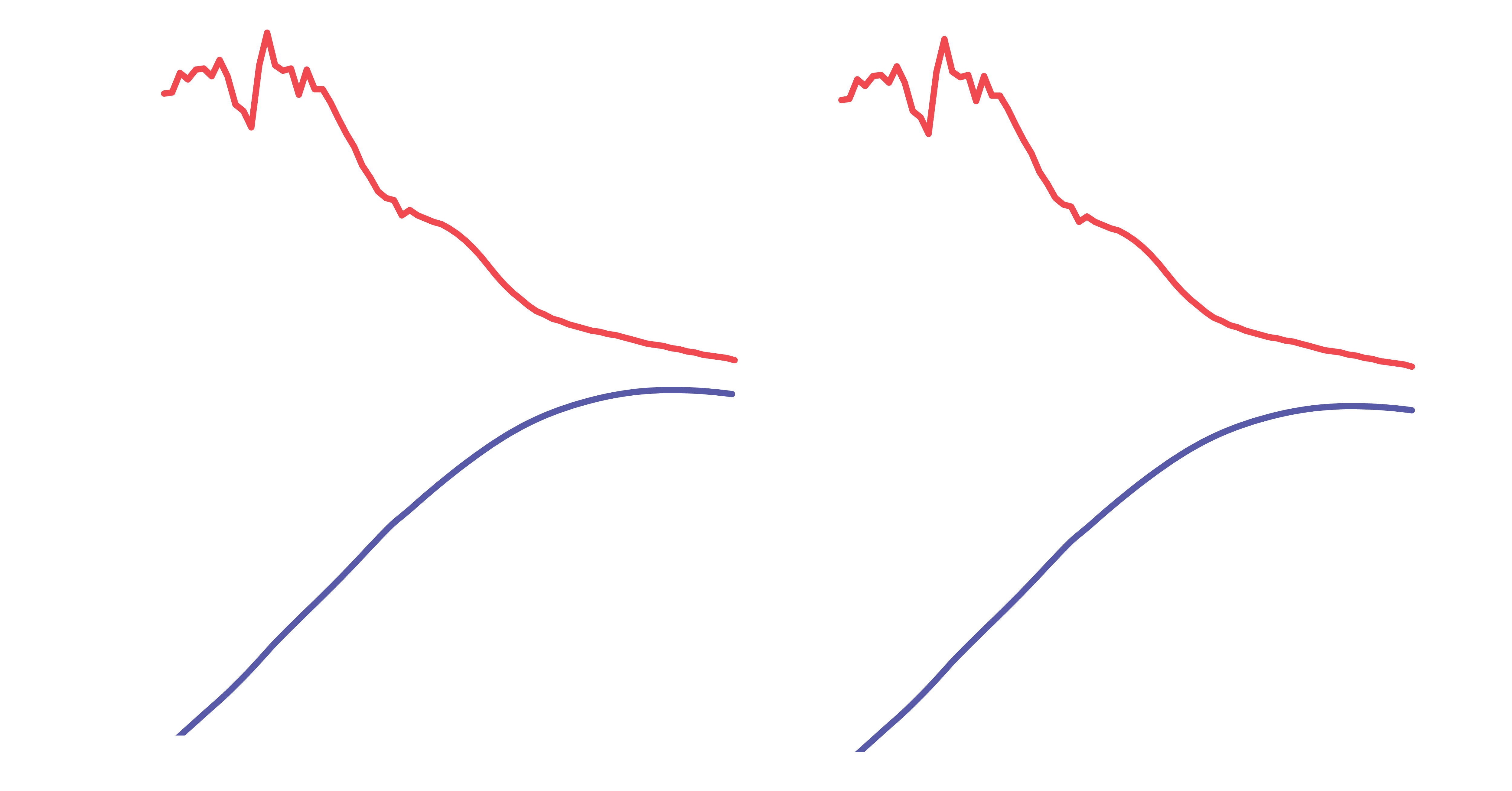

Population growth is no longer exponential – it peaked decades ago

There’s a popular misconception that the global population is growing exponentially. But it’s not.

While the global population is still increasing in absolute numbers, population growth peaked decades ago.

In the chart, we see the global population growth rate per year. This is based on historical UN estimates and its medium projection to 2100.

Global population growth peaked in the 1960s at over 2% per year. Since then, rates have more than halved, falling to less than 1%.

The UN expects rates to continue to fall until the end of the century. In fact, towards the end of the century, it projects negative growth, meaning the global population will shrink instead of grow.

Global population growth, in absolute terms – which is the number of births minus the number of deaths – has also peaked. You can see this in our interactive chart:

Annual population growth

The world has passed "peak child"

Hans Rosling famously coined the term " peak child " for the moment in global demographic history when the number of children stopped increasing.

According to the UN data, the world has passed "peak child", which is defined as the number of children under the age of five.

The chart shows the UN’s historical estimates and projections of the number of children under five.

It estimates that the number of children in the world peaked in 2017. For the coming decades, demographers expect a decades-long plateau before the number will decline more rapidly in the second half of the century.

- These projections are sensitive to the assumptions made about future fertility rates worldwide. Find out more from the UN World Population Division .

- Other sources and scenarios in the UN’s projections suggest that the peak was reached slightly earlier or later. However, most indicate that the world is close to "peak child" and the number of children will not increase in the coming decades.

- The 'ups and downs' in this chart reflect generational effects and 'baby booms' when there are large cohorts of women of reproductive age, and high fertility rates. The timing of these transitions varies across the world.

The UN expects the global population to peak by the end of the century

When will population growth come to an end?

The UN’s historical estimates and latest projections for the global population are shown in the chart.

The UN projects that the global population will peak before the end of the century – in 2086, at just over 10.4 billion people.

- These projections are sensitive to the assumptions made about future fertility and mortality rates worldwide. Find out more from the UN World Population Division .

- Other sources and scenarios in the UN’s projections can produce a slightly earlier or later peak. Most demographers, however, expect that by the end of the century, the global population will have peaked or slowed so much that population growth will be small.

Explore data on Population Growth

Interactive visualization requires JavaScript.

Research & Writing

What would the work look like if each country's area was in proportion to its population?

How has world population growth changed over time?

The world population has increased rapidly in recent centuries. But this is slowing.

Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie

Demographic change

Two centuries of rapid global population growth will come to an end

India's population growth will come to an end: the number of children has already peaked

Hannah Ritchie

More than 8 out of 10 people in the world will live in Asia or Africa by 2100

The global population pyramid: How global demography has changed and what we can expect for the 21st century

Population momentum: If the number of children per woman is falling, why is the population still increasing?

Demographic transition: Why is rapid population growth a temporary phenomenon?

Definitions and sources.

What are the sources for Our World in Data’s population estimates?

Edouard Mathieu and Lucas Rodés-Guirao

The UN has made population projections for more than 50 years – how accurate have they been?

Other articles related to population growth.

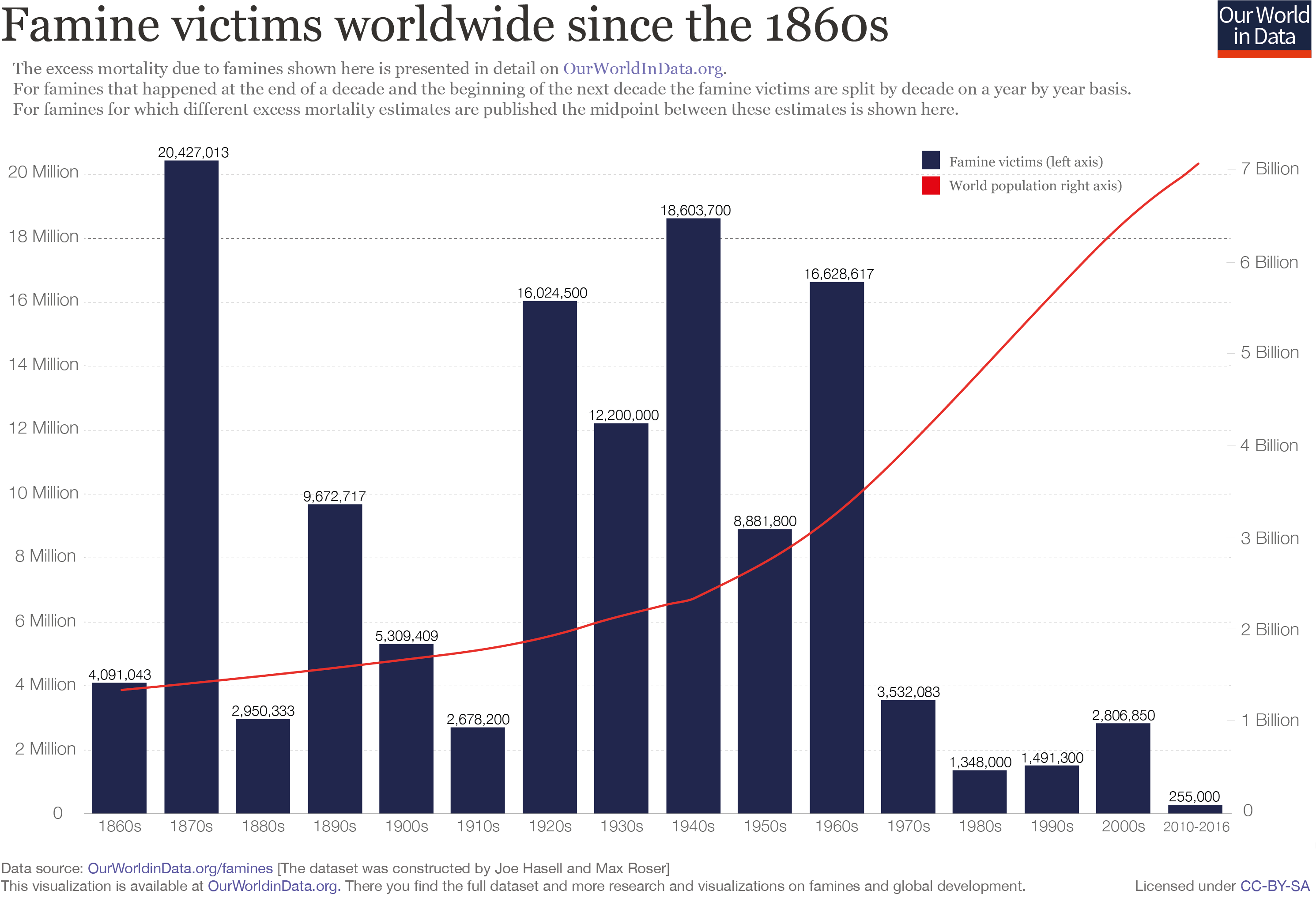

Does population growth lead to hunger and famine?

Do famines curb population growth?

More key articles on population growth, how many people die and how many are born each year.

Hannah Ritchie and Edouard Mathieu

Five key findings from the 2022 UN Population Prospects

Hannah Ritchie and Edouard Mathieu and Lucas Rodés-Guirao

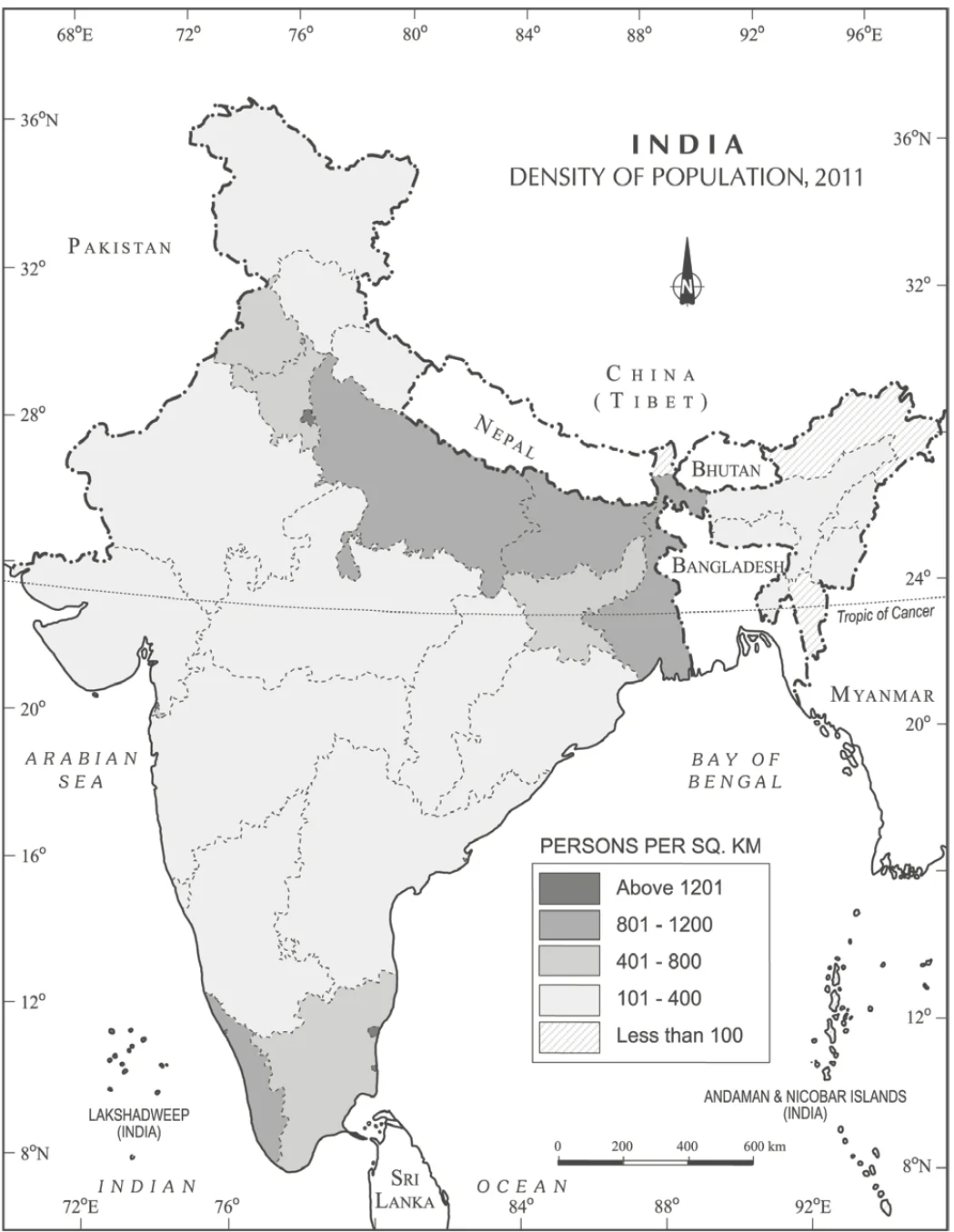

Which countries are most densely populated?

Interactive charts on population growth.

See, for example, Kremer (1993) – Population growth and technological change: one million BC to 1990 . In the Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 108, No. 3, 681-716.

As per 2011 estimates from Carl Haub (2011), “ How Many People Have Ever Lived on Earth? ” Population Reference Bureau.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

Population Growth and the Distribution of Human Populations to Effects on the Environment Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

The world population is growing at a rapid rate. Pundits estimate the world population as over six billion people (Livi-Bacci 8). With such a growth trend, a variety of impacts on resources is evidenced. An uncontrolled growth in human population significantly develops constraints on natural resources and food production (Miller and Scott 5).

There is also a tendency of a large human population exploiting resources and causing an environmental damage. The same negative impact can also be traced in the increased demand on energy. Therefore, exploitation of energy resources causes an energy crisis.

A growing population impact on natural resources focuses on resources such as water, forests and mineral reserves. It is natural that a growing population causes an increased demand on fresh water resources. This has sometimes led to water ownership conflicts. People, communities and countries have engaged on conflicts based on water ownership. This signifies that demand for fresh water is critical to human survival.

The increased demand for water, leads to shortage of water in lakes, dams, wells and rivers. The same impact on natural resources can be traced on deforestation. Demand for land to cultivate, and timber for construction increases with population growth. The use and economic value of minerals increases as the demand from the increasing and available market grows with time. This has seen a lot of mineral reserves depleted by human population over the years.

The survival of humanity has been dependent on energy availability for many years. Industrial civilization has significantly seen increased demand of energy. Although human race has been creative in maintaining the levels and variety of energy resources constant to ensure steady energy supply, there remains a threat of energy availability in the future.

Availability of energy sources like petroleum is not certain in the future considering that oil reserves may soon get depleted. However, the demand for energy has already sparked a need to use non-depleted energy sources like geothermal and wind energy. The current growing population is supported by electricity as an artificial energy source.

A large human population offers enough labor to produce enough food. However, there still remains a large population that cannot afford to feed on a balanced diet. With a large population, poverty becomes a critical issue that contributes to world hunger. The increasing world population has prompted the creation of food production mechanisms such as the genetically modified food products.

Again, distribution of food among the world’s population is dependent on a population’s food demand, economic status and available food production resources. Overpopulation in a region with less food production resources leads to a hunger crisis. It also becomes difficult to distribute food among the people.

An increasing human population puts pressure on the environment. In most cases, negative impacts on the environment are associated with an increasing human population (Livi-Bacci 23). The consumption rates on environmental factors rises due to an increasing demand on natural resources.

Land degradation as a result of increased demand on land for food production and construction also heightens as time progresses. Aspects such as environmental pollution cannot be ignored when population increases. This can be evidenced when industrial civilization by humans leads to disposal of pollutants on the environment. Factors such as global warming have become the current global and environmental threats in recent years. Global warming is predicted to continue in the future if effective measures are not established.

Works Cited

Livi-Bacci, Massimo. A concise history of world population . New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. Print.

Miller Jr, G. Tyler, and Scott E. Spoolman. Living in the Environment . London: CengageBrain. Com, 2011. Print.

- Calcium Is An Essential Mineral For Our Bodies

- Kyanite: Mineral Analysis

- Mineral and Water Function

- Applied Analysis of the Carbon Price Mechanism in Australia

- The 1979 Tangshan Earthquake

- Renewable Energy Co: Engineering Economics and TOP Perspectives of Renewable Energy in Canada

- Marginal Concepts: Advanced Modes of Resource Utilization

- When Human Diet Costs Too Much: Biodiversity as the Ultimate Answer to the Global Problems

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, January 17). Population Growth and the Distribution of Human Populations to Effects on the Environment. https://ivypanda.com/essays/population-growth-and-the-distribution-of-human-populations-to-effects-on-the-environment/

"Population Growth and the Distribution of Human Populations to Effects on the Environment." IvyPanda , 17 Jan. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/population-growth-and-the-distribution-of-human-populations-to-effects-on-the-environment/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Population Growth and the Distribution of Human Populations to Effects on the Environment'. 17 January.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Population Growth and the Distribution of Human Populations to Effects on the Environment." January 17, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/population-growth-and-the-distribution-of-human-populations-to-effects-on-the-environment/.

1. IvyPanda . "Population Growth and the Distribution of Human Populations to Effects on the Environment." January 17, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/population-growth-and-the-distribution-of-human-populations-to-effects-on-the-environment/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Population Growth and the Distribution of Human Populations to Effects on the Environment." January 17, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/population-growth-and-the-distribution-of-human-populations-to-effects-on-the-environment/.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In