Essays About Discrimination: Top 5 Examples and 8 Prompts

You must know how to connect with your readers to write essays about discrimination effectively; read on for our top essay examples, including prompts that will help you write.

Discrimination comes in many forms and still happens to many individuals or groups today. It occurs when there’s a distinction or bias against someone because of their age, race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, or disability.

Discrimination can happen to anyone wherever and whenever they are. Unfortunately, it’s a problem that society is yet to solve entirely. Here are five in-depth examples of this theme’s subcategories to guide you in creating your essays about discrimination.

1. Essay On Discrimination For Students In Easy Words by Prateek

2. personal discrimination experience by naomi nakatani, 3. prejudice and discrimination by william anderson, 4. socioeconomic class discrimination in luca by krystal ibarra, 5. the new way of discrimination by writer bill, 1. my discrimination experience, 2. what can i do to stop discrimination, 3. discrimination in my community, 4. the cost of discrimination, 5. examples of discrimination, 6. discrimination in sports: segregating men and women, 7. how to stop my discrimination against others, 8. what should groups do to fight discrimination.

“In the current education system, the condition of education and its promotion of equality is very important. The education system should be a good place for each and every student. It must be on the basis of equal opportunities for each student in every country. It must be free of discrimination.”

Prateek starts his essay by telling the story of a student having difficulty getting admitted to a college because of high fees. He then poses the question of how the student will be able to get an education when he can’t have the opportunity to do so in the first place. He goes on to discuss UNESCO’s objectives against discrimination.

Further in the essay, the author defines discrimination and cites instances when it happens. Prateek also compares past and present discrimination, ending the piece by saying it should stop and everyone deserves to be treated fairly.

“I thought that there is no discrimination before I actually had discrimination… I think we must treat everyone equally even though people speak different languages or have different colors of skin.”

In her short essay, Nakatani shares the experiences that made her feel discriminated against when she visited the US. She includes a fellow guest saying she and her mother can’t use the shared pool in a hotel they stay in because they are Japanese and getting cheated of her money when she bought from a small shop because she can’t speak English very well.

“Whether intentional or not, prejudice and discrimination ensure the continuance of inequality in the United States. Even subconsciously, we are furthering inequality through our actions and reactions to others… Because these forces are universally present in our daily lives, the way we use them or reject them will determine how they affect us.”

Anderson explains the direct relationship between prejudice and discrimination. He also gives examples of these occurrences in the past (blacks and whites segregation) and modern times (sexism, racism, etc.)

He delves into society’s fault for playing the “blame game” and choosing to ignore each other’s perspectives, leading to stereotypes. He also talks about affirmative action committees that serve to protect minorities.

“Something important to point out is that there is prejudice when it comes to people of lower class or economic standing, there are stereotypes that label them as untrustworthy, lazy, and even dangerous. This thought is fed by the just-world phenomenon, that of low economic status are uneducated, lazy, and are more likely to be substance abusers, and thus get what they deserve.”

Ibarra recounts how she discovered Pixar’s Luca and shares what she thought of the animation, focusing on how the film encapsulates socioeconomic discrimination in its settings. She then discusses the characters and their relationships with the protagonist. Finally, Ibarra notes how the movie alluded to flawed characters, such as having a smaller boat, mismatched or recycled kitchen furniture, and no shoes.

The other cast even taunts Luca, saying he smells and gets his clothes from a dead person. These are typical things marginalized communities experience in real life. At the end of her essay, Ibarra points out how society is dogmatic against the lower class, thinking they are abusers. In Luca, the wealthy antagonist is shown to be violent and lazy.

“Even though the problem of discrimination has calmed down, it still happens… From these past experiences, we can realize that solutions to tough problems come in tough ways.”

The author introduces people who called out discrimination, such as Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Barbara Henry – the only teacher who decided to teach Ruby Bridges, despite her skin color.

He then moves on to mention the variations of present-day discrimination. He uses Donald Trump and the border he wants to build to keep the Hispanics out as an example. Finally, Bill ends the essay by telling the readers those who discriminate against others are bullies who want to get a reaction out of their victims.

Do you get intimidated when you need to write an essay? Don’t be! If writing an essay makes you nervous, do it step by step. To start, write a simple 5 paragraph essay .

Prompts on Essays About Discrimination

Below are writing prompts that can inspire you on what to focus on when writing your discrimination essay:

Have you had to go through an aggressor who disliked you because you’re you? Write an essay about this incident, how it happened, what you felt during the episode, and what you did afterward. You can also include how it affected the way you interact with people. For example, did you try to tone down a part of yourself or change how you speak to avoid conflict?

List ways on how you can participate in lessening incidents of discrimination. Your list can include calling out biases, reporting to proper authorities, or spreading awareness of what discrimination is.

Is there an ongoing prejudice you observe in your school, subdivision, etc.? If other people in your community go through this unjust treatment, you can interview them and incorporate their thoughts on the matter.

Tackle what victims of discrimination have to go through daily. You can also talk about how it affected their life in the long run, such as having low self-esteem that limited their potential and opportunities and being frightened of getting involved with other individuals who may be bigots.

For this prompt, you can choose a subtopic to zero in on, like Workplace Discrimination, Disability Discrimination, and others. Then, add sample situations to demonstrate the unfairness better.

What are your thoughts on the different game rules for men and women? Do you believe these rules are just? Cite news incidents to make your essay more credible. For example, you can mention the incident where the Norwegian women’s beach handball team got fined for wearing tops and shorts instead of bikinis.

Since we learn to discriminate because of the society we grew up in, it’s only normal to be biased unintentionally. When you catch yourself having these partialities, what do you do? How do you train yourself not to discriminate against others?

Focus on an area of discrimination and suggest methods to lessen its instances. To give you an idea, you can concentrate on Workplace Discrimination, starting from its hiring process. You can propose that applicants are chosen based on their skills, so the company can implement a hiring procedure where applicants should go through written tests first before personal interviews.

If you instead want to focus on topics that include people from all walks of life, talk about diversity. Here’s an excellent guide on how to write an essay about diversity .

Maria Caballero is a freelance writer who has been writing since high school. She believes that to be a writer doesn't only refer to excellent syntax and semantics but also knowing how to weave words together to communicate to any reader effectively.

View all posts

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Code Switch

- School Colors

- Perspectives

The Code Switch Podcast

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Hear Something, Say Something: Navigating The World Of Racial Awkwardness

Listen to this week's episode.

We've all been there — having fun relaxing with friends and family, when someone says something a little racially off. Sometimes it's subtle, like the friend who calls Thai food "exotic." Other times it's more overt, like that in-law who's always going on about "the illegals."

In any case, it can be hard to know how to respond. Even the most level-headed among us have faltered trying to navigate the fraught world of racial awkwardness.

So what exactly do you do? We delve into the issue on this week's episode of the Code Switch podcast, featuring writer Nicole Chung and Code Switch's Shereen Marisol Meraji, Gene Demby and Karen Grigsby Bates.

We also asked some folks to write about what runs through their minds during these tense moments, and how they've responded (or not). Their reactions ran the gamut from righteous indignation to total passivity, but in the wake of these uncomfortable comments, everyone seemed to walk away wishing they'd done something else.

Aaron E. Sanchez

It was the first time my dad visited me at college, and he had just dropped me off at my dorm. My suitemate walked in and sneered.

"Was that your dad?" he asked. "He looks sooo Mexican."

Aaron E. Sanchez is a Texas-based writer who focuses on issues of race, politics and popular culture from a Latino perspective. Courtesy of Aaron Sanchez hide caption

He kept laughing about it as he left my room.

I was caught off-guard. Instantly, I grew self-conscious, not because I was ashamed of my father, but because my respectability politics ran deep. My appearance was supposed to be impeccable and my manners unimpeachable to protect against stereotypes and slights. I felt exposed.

To be sure, when my dad walked into restaurants and stores, people almost always spoke to him in Spanish. He didn't mind. The fluidity of his bilingualism rarely failed him. He was unassuming. He wore his working-class past on his frame and in his actions. He enjoyed hard work and appreciated it in others. Yet others mistook him for something altogether different.

People regularly confused his humility for servility. He was mistaken for a landscape worker, a janitor, and once he sat next to a gentleman on a plane who kept referring to him as a "wetback." He was a poor Mexican-American kid who grew up in the Segundo Barrio of El Paso, Texas, for certain. But he was also an Air Force veteran who had served for 20 years. He was an electrical engineer, a proud father, an admirable storyteller, and a pretty decent fisherman.

I didn't respond to my suitemate. To him, my father was a funny caricature, a curio he could pick up, purchase and discard. And as much as it was hidden beneath my elite, liberal arts education, I was a novelty to him too, an even rarer one at that. Instead of a serape, I came wrapped in the trappings of middle-classness, a costume I was trying desperately to wear convincingly.

That night, I realized that no clothing or ill-fitting costume could cover us. Our bodies were incongruous to our surroundings. No matter how comfortable we were in our skins, our presence would make others uncomfortable.

Karen Good Marable

When the Q train pulled into the Cortelyou Road station, it was dark and I was tired. Another nine hours in New York City, working in the madness that is Midtown as a fact-checker at a fashion magazine. All day long, I researched and confirmed information relating to beauty, fashion and celebrity, and, at least once a day, suffered an editor who was openly annoyed that I'd discovered an error. Then, the crush of the rush-hour subway, and a dinner obligation I had to fulfill before heading home to my cat.

Karen Good Marable is a writer living in New York City. Her work has been featured in publications like The Undefeated and The New Yorker. Courtesy of Karen Good Marable hide caption

The train doors opened and I turned the corner to walk up the stairs. Coming down were two girls — free, white and in their 20s . They were dancing as they descended, complete with necks rolling, mouths pursed — a poor affectation of black girls — and rapping as they passed me:

Now I ain't sayin she a golddigger/But she ain't messin' with no broke niggas!

That last part — broke niggas — was actually less rap, more squeals that dissolved into giggles. These white girls were thrilled to say the word publicly — joyously, even — with the permission of Kanye West.

I stopped, turned around and stared at them. I envisioned kicking them both squarely in their backs. God didn't give me telekinetic powers for just this reason. I willed them to turn around and face me, but they did not dare. They bopped on down the stairs and onto the platform, not evening knowing the rest of the rhyme.

Listen: I'm a black woman from the South. I was born in the '70s and raised by parents — both educators — who marched for their civil rights. I never could get used to nigga being bandied about — not by the black kids and certainly not by white folks. I blamed the girls' parents for not taking over where common sense had clearly failed. Hell, even radio didn't play the nigga part.

I especially blamed Kanye West for not only making the damn song, but for having the nerve to make nigga a part of the damn hook.

Life in NYC is full of moments like this, where something happens and you wonder if you should speak up or stay silent (which can also feel like complicity). I am the type who will speak up . Boys (or men) cussing incessantly in my presence? Girls on the train cussing around my 70-year-old mama? C'mon, y'all. Do you see me? Do you hear yourselves? Please. Stop.

But on this day, I just didn't feel like running down the stairs to tap those girls on the shoulder and school them on what they damn well already knew. On this day, I just sighed a great sigh, walked up the stairs, past the turnstiles and into the night.

Robyn Henderson-Espinoza

When I was 5 or 6, my mother asked me a question: "Does anyone ever make fun of you for the color of your skin?"

This surprised me. I was born to a Mexican woman who had married an Anglo man, and I was fairly light-skinned compared to the earth-brown hue of my mother. When she asked me that question, I began to understand that I was different.

Robyn Henderson-Espinoza is a visiting assistant professor of ethics at the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley, Calif. Courtesy of Robyn Henderson-Espinoza hide caption

Following my parents' divorce in the early 1980s, I spent a considerable amount of time with my father and my paternal grandparents. One day in May of 1989, I was sitting at my grandparents' dinner table in West Texas. I was 12. The adults were talking about the need for more laborers on my grandfather's farm, and my dad said this:

"Mexicans are lazy."

He called the undocumented workers he employed on his 40 acres "wetbacks." Again and again, I heard from him that Mexicans always had to be told what to do. He and friends would say this when I was within earshot. I felt uncomfortable. Why would my father say these things about people like me?

But I remained silent.

It haunts me that I didn't speak up. Not then. Not ever. I still hear his words, 10 years since he passed away, and wonder whether he thought I was a lazy Mexican, too. I wish I could have found the courage to tell him that Mexicans are some of the hardest-working people I know; that those brown bodies who worked on his property made his lifestyle possible.

As I grew in experience and understanding, I was able to find language that described what he was doing: stereotyping, undermining, demonizing. I found my voice in the academy and in the movement for black and brown lives.

Still, the silence haunts me.

Channing Kennedy

My 20s were defined in no small part by a friendship with a guy I never met. For years, over email and chat, we shared everything with each other, and we made great jokes. Those jokes — made for each other only — were a foundational part of our relationship and our identities. No matter what happened, we could make each other laugh.

Channing Kennedy is an Oakland-based writer, performer, media producer and racial equity trainer. Courtesy of Channing Kennedy hide caption

It helped, also, that we were slackers with spare time, but eventually we both found callings. I started working in the social justice sector, and he gained recognition in the field of indie comics. I was proud of my new job and approached it seriously, if not gracefully. Before I took the job, I was the type of white dude who'd make casually racist comments in front of people I considered friends. Now, I had laid a new foundation for myself and was ready to undo the harm I'd done pre-wokeness.

And I was proud of him, too, if cautious. The indie comics scene is full of bravely offensive work: the power fantasies of straight white men with grievances against their nonexistent censors, put on defiant display. But he was my friend, and he wouldn't fall for that.

One day he emailed me a rough script to get my feedback. At my desk, on a break from deleting racist, threatening Facebook comments directed at my co-workers, I opened it up for a change of pace.

I got none. His script was a top-tier, irredeemable power fantasy — sex trafficking, disability jokes, gendered violence, every scene's background packed with commentary-devoid, racist caricatures. It also had a pop culture gag on top, to guarantee clicks.

I asked him why he'd written it. He said it felt "important." I suggested he shelve it. He suggested that that would be a form of censorship. And I realized this: My dear friend had created a racist power fantasy about dismembering women, and he considered it bravely offensive.

I could have said that there was nothing brave about catering to the established tastes of other straight white comics dudes. I could have dropped any number of half-understood factoids about structural racism, the finishing move of the recently woke. I could have just said the jokes were weak.

Instead, I became cruel to him, with a dedication I'd previously reserved for myself.

Over months, I redirected every bit of our old creativity. I goaded him into arguments I knew would leave him shaken and unable to work. I positioned myself as a surrogate parent (so I could tell myself I was still a concerned ally) then laughed at him. I got him to escalate. And, privately, I told myself it was me who was under attack, the one with the grievance, and I cried about how my friend was betraying me.

I wanted to erase him (I realized years later) not because his script offended me, but because it made me laugh. It was full of the sense of humor we'd spent years on — not the jokes verbatim, but the pacing, structure, reveals, go-to gags. It had my DNA and it was funny. I thought I had become a monster-slayer, but this comic was a monster with my hands and mouth.

After years as the best of friends and as the bitterest of exes, we finally had a chance to meet in person. We were little more than acquaintances with sunk costs at that point, but we met anyway. Maybe we both wanted forgiveness, or an apology, or to see if we still had some jokes. Instead, I lectured him about electoral politics and race in a bar and never smiled.

- code switch

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- On Views of Race and Inequality, Blacks and Whites Are Worlds Apart

- 5. Personal experiences with discrimination

Table of Contents

- 1. Demographic trends and economic well-being

- 2. Views of race relations

- 3. Discrimination and racial inequality

- 4. Achieving racial equality

- 6. Views of community, family life and personal finances

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

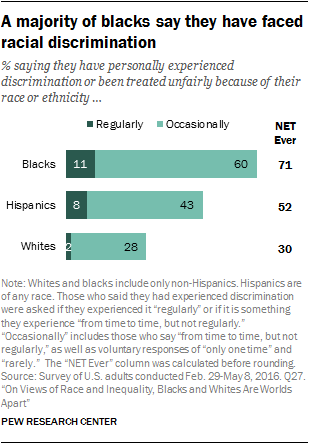

Roughly seven-in-ten black Americans (71%) say they have personally experienced discrimination or been treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity, including 11% who say this is something they experience regularly. Far lower shares of whites (30%) and Hispanics (52%) report experiencing discrimination because of their race or ethnicity.

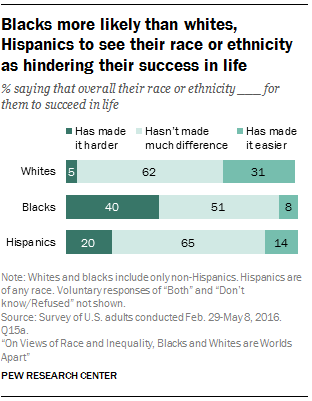

Overall, four-in-ten black Americans say their race or ethnicity has made it harder for them to succeed in life, while about half (51%) say it hasn’t made much difference, and just 8% say it has made it easier for them to succeed. One-in-five Hispanics say their race or ethnicity has made it harder to succeed in life, while just 5% of white adults say the same; 31% of whites say their race or ethnicity has made it easier for them to succeed.

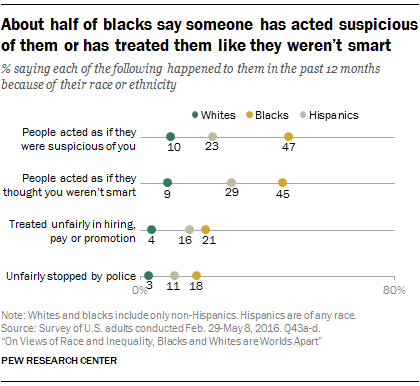

When asked about specific kinds of discrimination that people may face, about half of black adults said that in the past year someone has acted as if they were suspicious of them (47%) or as if they thought they weren’t smart (45%). About two-in-ten blacks say they were treated unfairly in hiring, pay or promotion over the past year (21%) and a similar share (18%) say they have been unfairly stopped by the police over the same period. In each of these cases, blacks are more likely than both whites and Hispanics to say they have experienced these things in the past year.

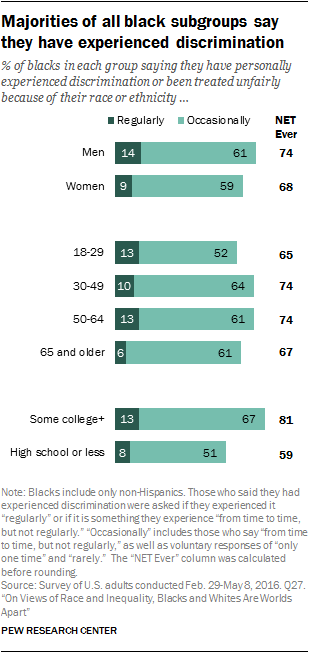

Majorities of all demographic subgroups of blacks have experienced racial discrimination

Large majorities of blacks across all major demographic groups say – at some point in their lifetime – they have experienced discrimination or been treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity, including similar shares of men and women, young and old, and those with higher and lower incomes.

Reports of discrimination are more common among blacks with at least some college education; 81% say they have experienced this at least occasionally, including 13% who say it happens regularly, compared with 59% and 8%, respectively, among blacks with a high school diploma or less.

Among blacks who say they have personally experienced discrimination, equal shares say discrimination built into our laws and institutions is the bigger problem for black people today as say the bigger problem is the prejudice of individual people (44% each). Blacks who say they have never experienced discrimination are more likely to see individual discrimination rather than institutional discrimination as the bigger problem (59% vs. 32%).

Among Hispanics, higher shares of those who are younger than 50 (58% vs. 35% of older Hispanics), have at least some college education (61% vs. 45% with no college experience) and are U.S. born (62% vs. 41% of foreign born) report having ever experienced discrimination.

The share of whites who say they have ever faced discrimination or been treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity is much lower than that of blacks or Hispanics. Still, three-in-ten white adults say they have experienced discrimination.

About half of blacks say someone has treated them with suspicion or like they weren’t smart

When asked about some things people may have experienced because of their race or ethnicity, roughly half 0f black Americans say that, in the past 12 months, someone has acted like they were suspicious of them (47%) or like they didn’t think they were smart (45%). About half as many say they have been treated unfairly by an employer in hiring, pay or promotion (21%) or that they have been unfairly stopped by police (18%) because of their race or ethnicity over the same period.

Whites are far less likely than blacks to say they have had these experiences. In fact, only about one-in-ten whites say that, in the past 12 months, someone has acted like they were suspicious of them (10%) or like they didn’t think they were smart (9%) because of their race or ethnicity, and even fewer say they have been treated unfairly by an employer (4%) or have been unfairly stopped by police (3%).

Among Hispanics, about three-in-ten (29%) say someone has acted like they thought they weren’t smart and about a quarter (23%) say someone has acted as if they were suspicious of them in the past 12 months; 16% of Hispanics say they have been treated unfairly by an employer and 11% say they have been unfairly stopped by police because of their race or ethnicity.

Black men are more likely than black women to say they have been seen as suspicious (52% vs. 44%) and that they have been unfairly stopped by police (22% vs. 15%) in the past 12 months. There is no significant difference in the share of black men and women who say someone has acted as if they thought they weren’t smart and who say they have been treated unfairly by an employer.

Blacks with at least some college education are more likely than those with a high school diploma or less to report having been treated as if they were not smart in the past year because of their race or ethnicity (52% vs. 37%). Blacks with at least some college education are also more likely than blacks with no college experience to say someone has acted like they were suspicious of them (55% vs. 38%).

With the exception of being unfairly stopped by police, perceptions of unfair treatment among blacks don’t differ significantly by family income. One-in-five blacks with annual family incomes under $30,000 or with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 say they have been unfairly stopped by police in the past year, compared with 12% of blacks with incomes of $75,000 or more.

Among Hispanics, those younger than 30 are more likely than those in older age groups to say they have been treated unfairly by an employer or that people have been suspicious of them or have acted as if they didn’t think they were smart because of their race or ethnicity. Nativity is also linked to these types of experiences. U.S.-born Hispanics are more likely than the foreign born to report being treated as if they were unintelligent (35% vs. 24%) or suspicious (32% vs. 14%) and to say they were treated unfairly by an employer in hiring, pay or promotion (20% vs. 12%).

Four-in-ten blacks say their race has made it harder for them to succeed in life

When asked whether their race or ethnicity has affected their ability to succeed in life, 40% of black adults say it has made it harder to succeed, while 51% say it has not made much difference and just 8% say it has made it easier. The share of blacks saying their race or ethnicity has made it harder to succeed is twice the share of Hispanics (20%) and eight times the share of whites (5%) who say this.

For their part, a majority of whites (62%) and Hispanics (65%) say their race or ethnicity hasn’t made a difference in their success. But whites are about twice as likely as Hispanics to say their race or ethnicity has made it easier to succeed in life (31% vs. 14%).

Black Americans younger than 50, as well as those with more education and higher incomes, are particularly likely to say their race or ethnicity has made it harder for them to succeed in life. About four-in-ten (43%) blacks ages 18 to 49 say this, compared with 35% of older blacks.

Among blacks with a bachelor’s degree or more, 55% say their race has been a disadvantage, while 45% of those with some college and 29% of those with a high school diploma or less say the same. Additionally, blacks with family incomes of $75,000 or more are more likely than those with family incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and those with family incomes below $30,000 to say their race has held them back (54% vs. 43% and 32%, respectively).

For Hispanics, the share saying their race or ethnicity has made it harder to succeed is higher among women (24% vs. 15% of men) and among those younger than 50 (23% vs. 11% of older Hispanics). There are no differences by education level or nativity.

Among whites, education, income, age and partisanship linked to views of impact of race

While most whites say their race or ethnicity has neither helped nor hurt their ability to succeed in life, a substantial share (31%) say their race or ethnicity has made things easier, a view that is more common among whites with at least a bachelor’s degree and with higher incomes, as well as among those who are younger than 50 and who identify with the Democratic Party.

About half of white college graduates (47%) say their race or ethnicity has been an advantage for them, compared with 31% of whites with some college education and an even lower share of whites with a high school diploma or less education (17%). Similarly, whites with family incomes of $75,000 or more (42%) are more likely than those with family incomes below $30,000 (23%) to say their race or ethnicity has made things easier for them. And while about four-in-ten (38%) whites who are younger than 50 say their race has been an advantage, 26% of older whites say the same.

White Democrats are also far more likely than white Republicans and independents to say their race or ethnicity has made it easier for them to succeed in life. About half (49%) of white Democrats say this, compared with a third of white independents (33%) and even fewer (17%) white Republicans.

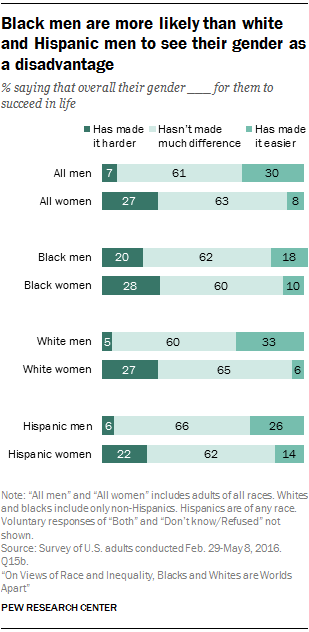

Blacks are more likely than whites to say their gender has made it harder to succeed

In addition to seeing their race as a disadvantage to their lifetime success, blacks are more likely than whites or Hispanics to see their gender as being a disadvantage, a difference that is due in large part to the views of black men, who are more likely than white and Hispanic men to say their gender has made it harder for them to succeed in life.

Among all Americans, women (27%) are more likely to say their gender has been a disadvantage in their lives than men (7%). On the flip side, 30% of men say their gender has made it easier for them to succeed in life, compared with 8% of women. Still, majorities of both men (61%) and women (63%) say their gender hasn’t made much difference in their success.

Across each of the major racial and ethnic groups, women are more likely than men to see their gender as a disadvantage for their success. This gap is particularly pronounced among whites (27% of women vs. 5% of men), and Hispanics (22% vs. 6%). Among blacks, the gap between women and men is much narrower; 28% of black women and 20% of black men say their gender has made it harder for them to succeed. But black men are more likely than black women to say their gender has made things easier for them (18% vs. 10%), as is the case to a greater extent for white men (33% vs. 6% of white women) and Hispanic men (26% vs. 14% of Hispanic women).

By and large, the perceptions women have of how their gender has shaped their chances of success do not differ across race and ethnicities. Black, Hispanic and white women are equally likely to say their gender has made it harder for them to succeed.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Age & Generations

- Black Americans

- Discrimination & Prejudice

- Economic Inequality

- Happiness & Life Satisfaction

- Middle Class

- Personal Finances

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Racial Bias & Discrimination

Teens and Video Games Today

As biden and trump seek reelection, who are the oldest – and youngest – current world leaders, how teens and parents approach screen time, who are you the art and science of measuring identity, u.s. centenarian population is projected to quadruple over the next 30 years, most popular, report materials.

- Interactive How blacks and whites view the state of race in America

- 2016 Racial Attitudes in America survey

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Photo by Kham/Reuters

The last great stigma

Workers with mental illness experience discrimination that would be unthinkable for other health issues. can this change.

by Pernille Yilmam + BIO

It is not difficult to find stories about the burdens and barriers faced by employees or job-seekers with mental illness. For example, it was recently reported that Scotland’s police denied a position to a promising trainee because of her use of antidepressants – in keeping with a rule that officers must be without antidepressant treatment for at least two years. In other cases, people have reported being fired from jobs at a university, a nursing home facility, a radio station, and a state agency following requests for medical leave due to postpartum depression, anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder, respectively. A US government commission maintains a select list of resolved lawsuits against companies that involved claims of mistreatment based on a worker’s mental health condition.

Often, the impact of negative attitudes toward mental illness is less overt than in these examples. More than a decade ago, a university professor named Suzanne published a book in which she openly discussed her life with bipolar disorder. The personal details that she revealed in the book, she told me, became a foundation for discriminatory treatment at her workplace. She said she experienced professional isolation in the hallways and meeting rooms: that colleagues stopped inviting her to collaborate with them, that she was shut down in department meetings and cut off from participating in decision-making committees. She attributes these developments to knowledge of her mental illness.

‘I experienced a very noticeable chill, averted eyes, actually being cut off when speaking in meetings,’ Suzanne recalled. ‘Lots of loaded language, of the “Well, SOME people just need to take their meds” variety, in meetings. This was the stage of my professional career where I started calling myself “the crazy lady in the corner”.’ At one point, when she had to take medical leave to address symptoms associated with her condition, a colleague opined that she was ‘lucky’ to have the option.

I n light of such stories, it’s not surprising that concerns about revealing mental health problems at work are commonplace. It’s estimated that 15 per cent of working-age adults have a mental health condition, and in a 2021 survey in the US, three-quarters of workers reported one or more symptoms of mental illness. One study surveying more than 800 people with major depressive disorder worldwide found that between 30 and 45 per cent reported experiencing discrimination in the workplace, with people in high-income countries reporting it at higher rates. A third of US employees polled by the American Psychiatric Association said they were worried about the consequences at work if they sought help for their mental health condition. In England, 61 per cent of survey respondents who were severely affected by mental illness said that ‘the fear of being stigmatised or discriminated against’ stopped them from applying for jobs and promotions. While there are signs that stigma related to mental illness has decreased over time (at least in some countries), stigma and discrimination continue to pose a problem in many workplaces.

Since the 1990s, a number of laws around the world have prohibited discrimination against employees with physical and mental disabilities. Among these are the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 in the US, the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 in Australia, and Article 13 of the Amsterdam Treaty of 1997 in the European Union. While these laws have done much to advance protections for people with disabilities, their impact on the treatment of people with mental illness – which constitutes a form of disability for many – has clearly had limits.

Mental illness-related discrimination persists as a multilayered problem characterised by fear, misconceptions and underenforced laws. The encouraging news is that scientists have been developing interventions to help reduce stigma and discrimination related to mental illness – approaches that should receive much more attention if advocates, employers and governments want to make workplaces fairer for all.

Job seekers reluctant to mention a mental illness history were more likely to be employed six months later

Discrimination against people with mental illness is often rooted in preconceived notions about what mental illness is and how it affects someone’s ability to work. These negative misconceptions are forms of mental illness stigma . Research has found that stigma is sometimes expressed by employers and colleagues as an issue of trust: eg, a belief that people with mental illness need more supervision, that they lack initiative, or that they are unable to deal with clients directly. Some might believe that people with mental illness are dangerous, or that they should hold only manual, lower-paying jobs. Research also suggests that many employers and coworkers believe people with mental illness should participate in the workforce, but are reluctant to work with them directly – which has been described as a type of ‘not in my backyard’ phenomenon.

Discriminatory behaviours have been investigated as well. In the US, researchers found that fictitious job applications that mentioned an applicant’s hospitalisation for mental illness led to fewer callbacks than applications noting a hospitalisation for a physical injury. Similar results were observed in Norway. In Germany, scientists found that job seekers who were more reluctant to mention their mental illness history in applications and interviews were more likely to be employed six months later. In addition to the potential impact on hiring, some people with mental illness have told researchers they believe they have been refused a promotion due to their condition.

In one revealing study , Matthew Ridley, an economist at Warwick University in the UK, had pairs of strangers collaborate on a virtual task. Before the task, each participant was shown characteristics of the person they had been matched with, which in some cases included mental illness. Ridley then asked if they wanted to be paired with someone else instead. The participants, he found, tended to be willing to give up some of their anticipated financial compensation to avoid working with a person who had significant depression or anxiety symptoms. When asked why, they indicated that they thought people with a mental illness would be less efficient in completing the task, would require more support, and would be less fun to work with. (For their part, among the participants who revealed to Ridley that they had a mental illness, a majority said they would pay to not have that fact revealed to their partner.)

In the end, participants were paired randomly and, when Ridley analysed the results, he found no differences in task success or enjoyment, regardless of whether someone worked with a person who had a mental illness. The findings capture how negative assumptions can come into play – and prove to be inaccurate – even in the context of a temporary collaboration.

T he perpetuation of mental illness stigma and discrimination comes at a cost not only to the affected individual, but also to companies and societies. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that mental illness costs the global economy $1 trillion annually. Among the reasons for these astronomical costs are the higher rates of sick days and unemployment among people with mental illness. The increased absences are partly due to lack of access to treatment; in 2021, it was estimated that only half of all US adults with mental illness had received mental health services in the past year. But a potential aggravating factor is that some employees with mental illness refrain from using their work-associated health insurance for treatment, out of fear that their employer will learn about their condition, resulting in their dismissal, or other forms of discrimination.

The denial of reasonable workplace accommodations could also make a person’s job more difficult and absences more likely. For a person who uses a wheelchair, an accommodation might be a ramp where there are stairs; for a person with a mental health condition, such as an anxiety disorder or ADHD, it could mean having a private office or noise-cancelling headphones to help with concentration problems, or flexibility in one’s work hours in order to attend healthcare appointments or accommodate heightened symptoms. It could also mean requesting leave for a mental health condition – up to 12 weeks in the US, similar to medical leave for physical injuries or for sickness. But some employees might avoid requesting the accommodations they are legally allowed to receive, simply because they suspect that doing so puts their job security and potential for advancement at risk.

The greater amount of absences among people with mental illness can make firings more likely. Losing a job can worsen mental illness, and people often stop applying for new jobs because they anticipate stigma and discrimination.

A list of the top 10 disabilities in US discrimination claims included depression, anxiety disorder and PTSD

Of course, one’s experience of work itself – a major cause of stress for many people – can also contribute to mental illness. One woman I spoke with, whom I’ll call Sara, shared that unsupportive and hostile work environments have made her anxiety even worse than it used to be. She believes that having to take time off work for her mental health led to her sudden termination from her previous job.

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), US employers are legally prohibited from discriminating based on physical or mental disabilities at any point during hiring, firing or professional evaluation. The same is true in Australia, based on the Disability Discrimination Act. Other countries have passed antidiscrimination legislation since then too, including South Africa’s Mental Health Care Act 17 of 2002 and India’s Equality Bill, 2019.

Yet, as we’ve seen, decades after the implementation of the ADA, problems remain. Studies continue to document stigma and discrimination against workers with mental illness. In 2020, a list of the top 10 disabilities in US discrimination claims included depression, anxiety disorder and PTSD. In Australia, a commission concluded back in 2004 that the country’s antidiscrimination legislation had been less effective in helping people with mental illness than those with mobility and sensory disabilities. In the EU, where Article 13 of the Amsterdam Treaty created a binding agreement to illegalise discrimination based on disabilities, researchers and clinical professionals were quick to point out its vagueness and lack of defined scope. An EU-funded consensus paper from 2010 documented the continued problem of discrimination against employees and job-seekers with mental illness.

Reports such as these call into question whether even a major law like the ADA can adequately address discrimination related to employee mental illness. And they should prompt us to reconsider how best to combat the problem. One question we can ask is: what might limit the impact of such laws in curbing discrimination against people with mental illness, compared with discrimination against people with physical disabilities? Let’s consider three potential answers.

F irst, discriminatory behaviour is not always obvious, and sometimes it is not even intentional. Compared with an employee who uses a wheelchair, it might be easier to dismiss a socially anxious person’s need to work from home. Compared with someone who is getting treatment for cancer, it might be easier to question whether an employee newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder will ever return as a valuable employee after their medical leave. Compared with a trauma-induced concussion, it might be easier to wonder whether a hypersensitivity to noise, related to PTSD, is really legitimate. Mental illnesses and their effects on people’s daily lives are often less apparent to others than the effects of a physical disability.

Second, laws like the ADA work only if people open up about their disabilities. The physical disability community has in the past decades led a cultural shift from exclusion and shame toward inclusivity and empowerment. People with physical disabilities have community, speak up and exercise their rights. Although there are ongoing efforts by people with mental illness to raise awareness about their experiences, many individuals stay quiet due to shame about their own condition or fear of how others will respond.

Even employers who want to hire people with mental illness can be subject to misguided beliefs

Lastly, the public stigma against mental illness bleeds into what people are expected to be able to handle and achieve. While physical disability is commonly perceived as a challenge with movement, mental illness is perceived as a challenge with thinking. Physical disabilities are seen as being caused by accidents or other unfortunate circumstances, while mental illnesses are often incorrectly seen as a choice or an inherent character flaw. Other misconceptions are that mental illness generally is untreatable or renders people violent or unable to work. An employer might therefore deem a person with mental illness unable to meet their job responsibilities, even when this assumption is unfounded.

Antidiscrimination laws are important, but they do not eliminate the tolls of stigma and capitalism. Employers want to make money, and a mental illness can be seen as a financial liability. Even employers who say they want to hire people with mental illness can be subject to misguided beliefs. And even when companies do grant accommodations, they might be limited. Sara, who in addition to struggling with anxiety has long had difficulty with focusing in distracting environments, was recently diagnosed with ADHD. Together with her psychiatrist, she submitted a request to her large corporate employer to work from home on two weekdays of her choosing, which would enable her to better focus on computer tasks – something that for her is much more difficult in a distracting open-office environment. She told me that it took six months for the accommodation request to be processed; in the end, she was allowed to work from home only on Mondays.

If people can develop the compassion needed to understand why ramps should be installed for use by employees with wheelchairs, there must be a way to heighten compassion for those who would benefit from, for example, a less distracting work environment. But history suggests it won’t be enough to make discriminatory practices illegal. It will require a change in perceptions.

F or many employees or job candidates with a mental illness, the prospect of workplaces free of stigma and discrimination may seem unattainable. ‘I cannot say anything definite that helps [reduce discrimination],’ Suzanne tells me. ‘If you keep your head down and do your job, then good people will eventually accept that this person is still fulfilling their job.’ There are, however, scientifically supported strategies that could be used in efforts to reduce mental illness stigma – and, consequently, discrimination – in workplaces. To the frustration of many anti-stigma advocates, these strategies have not yet been widely implemented.

One basic stigma-reducing strategy is based on social contact. Research suggests that people who have regularly interacted with someone who has personal experience with mental illness (such as a family member, friend or colleague) are often less likely to stigmatise and discriminate, and may be more likely to engage in empathic conversations about mental illness with employees. A law like the ADA should in theory have facilitated more social contact: if it freed more employees to disclose their mental illness and ask for reasonable accommodations, their coworkers would have learned that someone can have a mental illness and still be smart and productive. But, again, many people still do not disclose their mental illness (for fear of discrimination or other reasons), and coworkers cannot learn from what is not disclosed.

Educating HR professionals about mental illness could help reduce discriminatory practices

Another promising method for improving attitudes and behaviour toward employees with mental illness is psychoeducation. Broadly speaking, psychoeducation, also known as mental health education or mental health literacy, is a method of teaching what mental health is, why people might develop mental illnesses, and how these illnesses can be prevented and treated. It can also include the sharing of actionable strategies for coping with symptoms and crises, both acutely and preventatively. Psychoeducation incorporates components of group therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy, and is frequently used by psychiatrists and therapists in clinical settings. It was originally developed to support patients with severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and their families.

Excitingly, psychoeducation can also be used to help change the way workers with mental illness are perceived. While it has been most studied among patient groups as a method to reduce symptom severity and increase healthy coping strategies, it has been employed in professional settings too. For example, a systematic review of studies indicated that psychoeducational training for managers can improve their ‘knowledge, attitudes and self-reported behaviour in supporting employees experiencing mental health problems’. One study reported that managers who received psychoeducational training felt more confident in talking with employees about mental illness and were more likely to reach out to an employee who had an extended absence due to mental illness or stress. Researchers have also suggested that educating human-resources professionals about mental illness could help reduce discriminatory practices. Recently, the implementation of psychoeducational programmes in six companies within high-stress industries (such as hospitality) was found to reduce ratings of stress among workers and mental illness stigmatisation among workers.

The results from these studies are encouraging. Because psychoeducation can be delivered virtually in group settings and can be led by non-experts who’ve received appropriate training, it is also a cost-effective, scalable method. (Full disclosure: last year, I founded a nonprofit that has started to offer psychoeducational services in schools and other organisations.) But, for now, this approach appears to be rarely deployed in workplaces outside of research studies.

T he psychoeducation programmes in these studies typically take place in weekly, one- to two-hour sessions, lasting from a few weeks to months, and they are most often led by mental health professionals. They tend to focus on teaching people about and facilitating conversations on the causes, types, presentation and treatments of mental illness. The programmes often spend a considerable amount of time debunking common myths about mental health, and provide exercises to enable participants to help themselves or others with a mental illness. These exercises might include cognitive-behavioural tools for ‘fact-checking’ thought patterns, problem-solving skills, daily mood journals, and breathing exercises. A major goal is to challenge ideas about mental illness that underlie stigma and discrimination.

In a 2022 policy brief on mental health at work, the WHO argued for greater efforts to improve mental health literacy and support employees with mental illness. Psychoeducational programmes could be a prime tool for pursuing these goals, a staple for companies that aim to comply with antidiscrimination law and improve employee wellbeing. If psychoeducation helps key stakeholders, such as employers and human-resources professionals, to treat employees and job candidates with greater understanding, that might also lead to fewer sick days, enhanced productivity and more employment among people with mental illness. Perhaps work itself will become a less prominent driver of stress.

Some companies currently provide offerings such as unlimited vacation days, meditation apps or yoga sessions as a way to show support for employees’ wellbeing. But these sorts of benefits likely do little to address stigma or discrimination in workplaces. Moreover, implicit in this strategy is the idea that mental illness is a problem that can and should be addressed by individual employees, without putting broader workplace conventions and beliefs into question.

‘In contrast to my mental illness, my concussion was immediately accommodated’

While a severe version of a state such as psychosis or mania can be devastating for the person experiencing it, most people who have a mental health condition are not dealing with crises from day to day. Yes, someone with mental illness might be more easily distracted, more sensitive to noise or less social, but that doesn’t mean that their symptoms will inevitably hamper their job performance. What does hamper performance is when companies neglect to provide reasonable accommodations, even when studies suggest that the benefits associated with providing such accommodations outweigh the costs.

Wouldn’t most companies be inclined to provide structural and logistical support for an employee who suddenly became paraplegic, or who suffered another disabling physical ailment? One former tech industry employee told me that she saw a marked difference in how her leave-taking was received depending on whether it was mental health-related or not. ‘A while after returning from my mental health leave,’ she says, ‘I got a concussion for which I needed partial leave. The symptoms I had were so similar to my PTSD but, in contrast to my mental illness, my concussion was immediately accommodated with a 90-day medical leave and temporary part-time work schedule without any stigma.’ Sara, too, noticed a stark difference when she needed medical leave and other task-related accommodations to recover from shoulder surgery, as opposed to accommodations related to her mental health.

The evidence of ongoing and unnecessary burdens on workers with mental illness calls for honest consideration of what previous antidiscrimination measures have and have not achieved. Employers and governments have yet to fulfil the promise of landmark antidiscrimination laws for the many millions of people who go to work with mental health conditions. Fortunately, there is hope that evidence-backed approaches such as psychoeducational programmes could – if more widely embraced – provide an effective tool for making workplaces fairer and more supportive.

Stories and literature

Her blazing world

Margaret Cavendish’s boldness and bravery set 17th-century society alight, but is she a feminist poster-girl for our times?

Francesca Peacock

Ecology and environmental sciences

To take care of the Earth, humans must recognise that we are both a part of the animal kingdom and its dominant power

Hugh Desmond

Folk music was never green

Don’t be swayed by the sound of environmental protest: these songs were first sung in the voice of the cutter, not the tree

Richard Smyth

Nations and empires

A United States of Europe

A free and unified Europe was first imagined by Italian radicals in the 19th century. Could we yet see their dream made real?

Fernanda Gallo

On Jewish revenge

What might a people, subjected to unspeakable historical suffering, think about the ethics of vengeance once in power?

Shachar Pinsker

Learning to be happier

In order to help improve my students’ mental health, I offered a course on the science of happiness. It worked – but why?

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: MCAT > Unit 13

- Discrimination questions

Examples of discrimination in society today

- Discrimination individual vs institutional

- Prejudice and discrimination based on race, ethnicity, power, social class, and prestige

- Stereotypes stereotype threat, and self fulfilling prophecy

What is discrimination?

Discrimination in the workplace, minority groups and marginalization, fighting back, attribution:, additional references, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

14 influential essays from Black writers on America's problems with race

- Business leaders are calling for people to reflect on civil rights this Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

- Black literary experts shared their top nonfiction essay and article picks on race.

- The list includes "A Report from Occupied Territory" by James Baldwin.

For many, Martin Luther King Jr. Day is a time of reflection on the life of one of the nation's most prominent civil rights leaders. It's also an important time for people who support racial justice to educate themselves on the experiences of Black people in America.

Business leaders like TIAA CEO Thasunda Duckett Brown and others are encouraging people to reflect on King's life's work, and one way to do that is to read his essays and the work of others dedicated to the same mission he had: racial equity.

Insider asked Black literary and historical experts to share their favorite works of journalism on race by Black authors. Here are the top pieces they recommended everyone read to better understand the quest for Black liberation in America:

An earlier version of this article was published on June 14, 2020.

"Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases" and "The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States" by Ida B. Wells

In 1892, investigative journalist, activist, and NAACP founding member Ida B. Wells began to publish her research on lynching in a pamphlet titled "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases." Three years later, she followed up with more research and detail in "The Red Record."

Shirley Moody-Turner, associate Professor of English and African American Studies at Penn State University recommended everyone read these two texts, saying they hold "many parallels to our own moment."

"In these two pamphlets, Wells exposes the pervasive use of lynching and white mob violence against African American men and women. She discredits the myths used by white mobs to justify the killing of African Americans and exposes Northern and international audiences to the growing racial violence and terror perpetrated against Black people in the South in the years following the Civil War," Moody-Turner told Business Insider.

Read "Southern Horrors" here and "The Red Record" here >>

"On Juneteenth" by Annette Gordon-Reed

In this collection of essays, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Annette Gordon-Reed combines memoir and history to help readers understand the complexities out of which Juneteenth was born. She also argues how racial and ethnic hierarchies remain in society today, said Moody-Turner.

"Gordon-Reed invites readers to see Juneteenth as a time to grapple with the complexities of race and enslavement in the US, to re-think our origin stories about race and slavery's central role in the formation of both Texas and the US, and to consider how, as Gordon-Reed so eloquently puts it, 'echoes of the past remain, leaving their traces in the people and events of the present and future.'"

Purchase "On Juneteenth" here>>

"The Case for Reparations" by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates, best-selling author and national correspondent for The Atlantic, made waves when he published his 2014 article "The Case for Reparations," in which he called for "collective introspection" on reparations for Black Americans subjected to centuries of racism and violence.

"In his now famed essay for The Atlantic, journalist, author, and essayist, Ta-Nehisi Coates traces how slavery, segregation, and discriminatory racial policies underpin ongoing and systemic economic and racial disparities," Moody-Turner said.

"Coates provides deep historical context punctuated by individual and collective stories that compel us to reconsider the case for reparations," she added.

Read it here>>

"The Idea of America" by Nikole Hannah-Jones and the "1619 Project" by The New York Times

In "The Idea of America," Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones traces America's history from 1619 onward, the year slavery began in the US. She explores how the history of slavery is inseparable from the rise of America's democracy in her essay that's part of The New York Times' larger "1619 Project," which is the outlet's ongoing project created in 2019 to re-examine the impact of slavery in the US.

"In her unflinching look at the legacy of slavery and the underside of American democracy and capitalism, Hannah-Jones asks, 'what if America understood, finally, in this 400th year, that we [Black Americans] have never been the problem but the solution,'" said Moody-Turner, who recommended readers read the whole "1619 Project" as well.

Read "The Idea of America" here and the rest of the "1619 Project here>>

"Many Thousands Gone" by James Baldwin

In "Many Thousands Gone," James Arthur Baldwin, American novelist, playwright, essayist, poet, and activist lays out how white America is not ready to fully recognize Black people as people. It's a must read, according to Jimmy Worthy II, assistant professor of English at The University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

"Baldwin's essay reminds us that in America, the very idea of Black persons conjures an amalgamation of specters, fears, threats, anxieties, guilts, and memories that must be extinguished as part of the labor to forget histories deemed too uncomfortable to remember," Worthy said.

"Letter from a Birmingham Jail" by Martin Luther King Jr.

On April 13 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. and other Civil Rights activists were arrested after peaceful protest in Birmingham, Alabama. In jail, King penned an open letter about how people have a moral obligation to break unjust laws rather than waiting patiently for legal change. In his essay, he expresses criticism and disappointment in white moderates and white churches, something that's not often focused on in history textbooks, Worthy said.

"King revises the perception of white racists devoted to a vehement status quo to include white moderates whose theories of inevitable racial equality and silence pertaining to racial injustice prolong discriminatory practices," Worthy said.

"The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action" by Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde, African American writer, feminist, womanist, librarian, and civil rights activist asks readers to not be silent on important issues. This short, rousing read is crucial for everyone according to Thomonique Moore, a 2016 graduate of Howard University, founder of Books&Shit book club, and an incoming Masters' candidate at Columbia University's Teacher's College.

"In this essay, Lorde explains to readers the importance of overcoming our fears and speaking out about the injustices that are plaguing us and the people around us. She challenges us to not live our lives in silence, or we risk never changing the things around us," Moore said. Read it here>>

"The First White President" by Ta-Nehisi Coates

This essay from the award-winning journalist's book " We Were Eight Years in Power ," details how Trump, during his presidency, employed the notion of whiteness and white supremacy to pick apart the legacy of the nation's first Black president, Barack Obama.

Moore said it was crucial reading to understand the current political environment we're in.

"Just Walk on By" by Brent Staples

In this essay, Brent Staples, author and Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial writer for The New York Times, hones in on the experience of racism against Black people in public spaces, especially on the role of white women in contributing to the view that Black men are threatening figures.

For Crystal M. Fleming, associate professor of sociology and Africana Studies at SUNY Stony Brook, his essay is especially relevant right now.

"We see the relevance of his critique in the recent incident in New York City, wherein a white woman named Amy Cooper infamously called the police and lied, claiming that a Black man — Christian Cooper — threatened her life in Central Park. Although the experience that Staples describes took place decades ago, the social dynamics have largely remained the same," Fleming told Insider.

"I Was Pregnant and in Crisis. All the Doctors and Nurses Saw Was an Incompetent Black Woman" by Tressie McMillan Cottom

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an author, associate professor of sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University and a faculty affiliate at Harvard University's Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. In this essay, Cottom shares her gut-wrenching experience of racism within the healthcare system.

Fleming called this piece an "excellent primer on intersectionality" between racism and sexism, calling Cottom one of the most influential sociologists and writers in the US today. Read it here>>

"A Report from Occupied Territory" by James Baldwin

Baldwin's "A Report from Occupied Territory" was originally published in The Nation in 1966. It takes a hard look at violence against Black people in the US, specifically police brutality.

"Baldwin's work remains essential to understanding the depth and breadth of anti-black racism in our society. This essay — which touches on issues of racialized violence, policing and the role of the law in reproducing inequality — is an absolute must-read for anyone who wants to understand just how much has not changed with regard to police violence and anti-Black racism in our country," Fleming told Insider. Read it here>>

"I'm From Philly. 30 Years Later, I'm Still Trying To Make Sense Of The MOVE Bombing" by Gene Demby

On May 13, 1985, a police helicopter dropped a bomb on the MOVE compound in Philadelphia, which housed members of the MOVE, a black liberation group founded in 1972 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Eleven people, including five children, died in the airstrike. In this essay, Gene Demby, co-host and correspondent for NPR's Code Switch team, tries to wrap his head around the shocking instance of police violence against Black people.

"I would argue that the fact that police were authorized to literally bomb Black citizens in their own homes, in their own country, is directly relevant to current conversations about militarized police and the growing movement to defund and abolish policing," Fleming said. Read it here>>

When you buy through our links, Insider may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more .

- Main content

Essay About Racial Discrimination

Racial discrimination has been ranked as one the most pervasive issue in the world around today. Anyone judged by the skin colour, nationality, religion rather than by the content of character can be very dehumanizing experience that can have lasting effects on an individual’s life (Fischer 2008). Racism disturbs both individual and the learning environment in schools. It generates tension that alter cultural understanding and narrow the educational experiences of all students. According to (Berlak 2009) discrimination occurs in any stage of education from preschool through college and can be practiced by teachers or students. Racism occur in various forms such as teasing, name calling, teasing, verbal abuse and bullying. Therefore this literature review, discusses the types, effects and solution to this unstoppable issue in education system.

Types of Racial Discrimination

Racism is frequently thought of as individual demonstrations of inclination. While discrimination is still particularly a reality, concentrating on individual demonstrations of prejudice can darken the substances that make and keep up racial disparity all the more comprehensively. According to De la luz, there are three types of racial discrimination which are individual racism, instituinal racism and systematic racism. To completely address the effects of racism it is essential to address all parts of racial disparity. Individual racism, likewise called personal racism, is the sort of prejudice that a great many people consider when they consider “racism.” Individual prejudice happens when a man’s convictions, states of mind, and activities depend on inclinations, generalizations, or preferences against another race. Institutional racism refers to an establishment settling on decisions that deliberately single out or hurt ethnic minorities. Systematic racism, is maybe the most upsetting and slightest examined type of racism. It systematizes individual, social, and different sorts of prejudice in ceaseless frameworks. Like institutional prejudice, basic racism centre around associations instead of individuals. However, while institutional racism may intentionally attempt to single out a specific gathering, auxiliary bigotry is unbiased all over. This impartiality makes basic prejudice hard to gauge and significantly more hard to end.

Effects of Racial Discrimination

It is believed that racism is one term that describes the whole issue, however it is a complex system that describes many types of biased behaviours and systems (Jonnes 2018).According to the Human Rights Commission (2017), racism as an act that humiliates human behaviour and affects the life of an individual physically, mentally and socially. It takes various forms such as name calling, comments, jokes, verbal abuse, harassment, bullying or commentary in the media that inflames hostility towards certain groups. In serious case, it results in physical abuse and violence. Racial discrimination is a deadly virus that affects all, individual, families, communities and the learning and working environment. Racism can unpleasantly affect the educational outcomes, individual happiness and self-confidence, cultural identity, school and community relations and most commonly is the student’s behaviour and academic achievements (Kohli, 2017). Hence if it is unaddressed than racism can generate tensions within the school communities and these will affect the educational experiences of all students. It can demoralise students self -confidence and can result in students displaying a range of negative behaviours Students who are disaffected with school are less likely to attend school regularly and more likely to drop out of school earlier than other groups of students. The increase rate of the incidence of absenteeism and stress is due to racism been link to diminished morale and lower productivity (Fields 2014),The presence of racism in schools affects the educational outcomes due to lower participation rates, behavioural problems and feelings of alienation. Hence the educational success depends on the regular sustained attendance of each students and the ability to participate in the classroom. With racism in the learning environment, the balance is disrupted and educational outcomes maybe limited as a result (Triaki 2017).

Moreover, racism could be minimised even though it will decade to erase it from our beautiful world. Advancing positive ethnic and racial character decreases sentiments of detachment or prohibition and enhance students capacity to focus in the classroom. Teachers can enable students to create positive opinions about their ethnic and racial personality by presenting them to assorted good examples, and making a sheltered space for them to commend their disparities. A definitive answer for this issue is diminishing understudy introduction to racial separation and enhancing race relations in the U.S. In the interim, there are ways minding and concerned grown-ups can enable understudies to manage the pressure be minimised even though it will take time to prevent it from being practiced in schools. (Collins 2015).Racism has been around everlastingly however it can be diminished, just with a lot of exertion. Education is the key for some muddled issues we look in this world. Education can change the manner in which people think and lead us to a superior world. We can battle racism with education (Hwang 2008). On the off chance that we instruct and show sympathy, at that point there will be less need to discuss how we can stop racism. It will be difficult to stop racism if racist considerations are still with us. It is dependent upon us to get ready for the future by teaching our family and others on the difficulties of racial discrimination. At exactly that point will we overcome racial discrimination in our societies and schools.

Racial discrimination could be described as a weapon that destroys the society and the education system as whole. It affects the students in various ways that hinder their academic achievement and also affects them mentally, physically and socially. It was also stated that racial discrimination can occur at any stage either preschool, high schools or even tertiary institution. Hence there are possible ways where racism could be minimized even though it will take time to be erased. Therefore education is an important tool in everyone’s life since it can change the world and every individual.

Equal Opportunity and Discrimination Essay

The history of humanity contains many examples of injustice, such as slavery, racism, sexism, and others. To build a better world, people have to learn from their mistakes and attempt to avoid them in the future. Social equity became an inseparable feature of modern society’s vision in this context. Consequently, the concept of equal opportunity was developed to address discrimination issues and ensure social equity.

The quality of an individual’s life directly depends on his self-realization, improvement, and personal growth. If this is denied without the explicit justification of particular reasons, it can be considered discrimination. Discrimination is a special attitude toward an individual because of prejudices, preferences, or specific artificial barriers (Mason, 2018). On the contrary, equal opportunity (EO) implies that individuals should be treated equally no matter their age, national origin, disability, sexual orientation, or other associated factors (Mason, 2018). EO can be applied to all aspects of life in society, for example, to employment.

A common situation in the hiring process is that an employer prefers not to hire young female individuals who do not yet have children. A certain logic is behind such preference, although it can hardly be considered fair – an employer does not want to deal with a woman’s possible pregnancy. Maternity leave is a common practice, although employers might not be satisfied with the perspective of having to financially cover an employee’s absence, keeping the job position, and looking for a temporal substitution.

Issued in 1964, Title VII of the civil rights act covers every type of discrimination, including discrimination by sex. According to equal employment opportunity, every employee or job applicant has to be protected against discrimination. Thus, if a female individual feels denied a job opportunity due to the employer’s attitude to her possible pregnancy, she can apply to the Equal employment opportunity commission (EEOC) and ask for an investigation (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission). The law also makes it illegal for the employer to retaliate the discrimination accusation, thus ensuring the individual’s future protection.

EO serves as a shield for individuals against social injustice in the form of discrimination. Protected by federal laws and institutions, such as EEOC, in case of issues in the workplace, EO ensures that people are treated as fair as possible with no regard to their specific unique features. Consequently, people have much more freedom when it comes to self-expression, improvement, and achievement of their personal goals.

Mason, A. (2018). Social justice: The place of equal opportunity. In R. Bellamy & A. Mason (Eds.), Political concepts (pp. 28-40). Manchester University Press.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. (n.d.). U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Web.

- The EEOC’s Role in the Lawsuit

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Title VII of The Civil Rights Act 1964

- Employees' Right of Free Speech on Social Media

- The Miranda Rights, Their Importance and Limitations

- The Griswold v. Connecticut Case Study

- Supreme Court: Originalism and Textualism

- Freedom of the Press and National Security

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, September 29). Equal Opportunity and Discrimination. https://ivypanda.com/essays/equal-opportunity-and-discrimination/

"Equal Opportunity and Discrimination." IvyPanda , 29 Sept. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/equal-opportunity-and-discrimination/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Equal Opportunity and Discrimination'. 29 September.