Research to Action

The Global Guide to Research Impact

Social Media

Strategic communication

7 principles for doing meaningful research communications

By Emilie Wilson , Vivienne Benson , Samantha Reddin , Ben O'Donovan-Iland , Annabel Fenton , Sophie Marsden , Roxana-Alina Vaduva and Alice Webb 25/02/2022

At IDS, we believe that evidence-based research plays a vital role in bringing about a more equitable and sustainable world. And to achieve this, we are committed to communicating research beyond academic audiences and journal articles.

However, we are very aware of the responsibility we have in shaping and delivering meaningful research communications. We are tackling complicated and sensitive issues and the communications process and content should reflect that. That is why we have developed 7 guiding principles to underpin our approach to research communications – throughout the lifetime of a project or programme.

1. Enabling

When it comes to engaging stakeholders and audiences in a targeted and meaningful way, the research team have relationships and networks beyond the reach of communications specialists, which need to be used. Researchers and partners share findings and messages at meetings and events, have one-to-one conversations and send direct communications, or engage with social media. These are all key communications tactics. Project support staff are also often heavily involved in engaging stakeholders and organising events. They can be seen as the ‘face’ of the project for partners, as a key point of contact.

Our role as communicators is to enable and facilitate our colleagues, partners, and networks to communicate in a way that fosters these important and individual relationships.

2. Context-specific

Most projects and programmes will set time and resources aside for scoping research questions in different contexts – be this geographical or sectoral. They will also ensure the right partners are on board with relevant local expertise. It is equally important to take this approach for successful research communications and uptake, for example looking at the media and social media landscape, mapping digital inequalities and internet penetration. There can be difficult dynamics to consider in many of the countries and settings in which we conduct our research. This can be a result of aid being increasingly targeted at fragile, violent or conflict-affected settings or the shrinking civic space.

Underpinning our work is a commitment to lead activities and work with partners to understand and remain up to date on ‘context’. This ultimately means that we create communications (often in partnership) that are sensitive to the different contexts and settings we navigate.

3. Targeted and agile

Understanding the ‘who’ is fundamental for reaching and delivering meaningful communications and engagement. Without that knowledge, we would only create general, or worse, irrelevant communications that don’t mean anything to our key stakeholders. We have connected the ‘targeted’ to keeping our communications ‘agile’ as we are committed to communications that are responsive to the times and to the needs of our stakeholders.

By embedding this approach in projects and programmes, research communications has much more impact and relevance to the context.

4. Creative

Creative communications is as simple as it sounds. It’s about keeping an open mind and identifying the approach, format and content for your communications that engages your target audience most effectively. This involves thinking not only about the content you create (i.e., through visual, digital and written) but also the spaces and ways in which you might share and engage.

Being creative in how we communicate leads to greater clarity in our messaging. It also means we are open to new and relevant opportunities that might be outside our usual approach. It also allows for flexibility and scope to bring in partners and key stakeholders into shaping our communications.

5. Data-driven

Data analysis is a key aspect of successfully communicating impact. It provides an accurate understanding of the outcomes of our communications, which helps the team make informed decisions and accurately shape communications throughout the lifetime of the project.

What can happen if you don’t take the time to analyse the impact of communications? The phrase ‘if you throw enough mud at a wall, some of it will stick’ comes to mind. Imagine that your research paper gets great engagement in Uganda – do you understand why it got engagement, who was reading it, and what they did after reading it? If you understand and document that, can you incorporate more of that into your communications approach going forward?

Data collation can range from social media metrics to engagement at an event, to testimonials. Without the proper tools and processes in place to analyse your data, you can lose on valuable opportunities to target content and drive more engagement.

6. Decolonised

When applied to development, a decolonial lens questions the underlying assumptions: that Western progress is aspirational, and that former colonies are ‘behind’ because they fall short in terms of mainstream socioeconomic indicators.

When it comes to communications, the same power hegemonies and assumed moralities influence how we communicate about (and communicate to) marginalised individuals, communities, countries, and regions. We are working towards decolonised communications by continuously questioning our approach, and ourselves: this includes being more conscious about asking who the right people are to do the communications, questioning what we show (vocabulary, images), how we put it together (our suppliers, who’s doing the talking), and who we are targeting (our audience, translation, and accessibility).

7. Accessible

Accessibility in communications is about inclusivity, making sure that everyone can access and understand research. Accessible communications encompass all media types and takes different forms depending on individual or group needs.

Accessible communication materials must be clear and understandable, easy to access and navigate, and respect people’s different needs. It is at the heart of aesthetics and design, and is included for all video, aural, digital, print and web media. People living with disability should, where possible, be involved in the production and delivery of communications materials, such as writing blogs or speaking at events; they should be heard and not spoken for.

We aim to review our accessibility methods on a regular basis to ensure they are working and improving; this includes getting feedback from people living with disabilities.

This article was first published on the IDS Opinions blog .

Contribute Write a blog post, post a job or event, recommend a resource

Partner with Us Are you an institution looking to increase your impact?

Most Recent Posts

- Youth-focused initiatives: Youth and Social Justice Futures Project

- There are many pathways to impact

- Theories of Change: A guide to monitoring and evaluating policy influence

- Lessons for capacity building in developing countries

- Recognising Africa’s evidence actors

Last week's #R2AImpactPractitioners post shared a report, from the Institute for Government, filled with practical strategies to boost the impact of academic research in policy. 🔗🔗Follow the link in our bio to read the full article. #PolicyEngagement #ResearchImpact #EIDM

As part of our new Youth Inclusion and Engagement Space we are profiling some of the initiatives having real impact in this area. First up it's @GAGEprogramme... Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence (GAGE) is a groundbreaking ten-year research initiative led by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). From 2015 to 2025, GAGE is following the lives of 20,000 adolescents across six low- and middle-income countries in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, generating the world’s largest dataset on adolescence. GAGE’s mission is clear: to identify effective strategies that help adolescent boys and girls break free from poverty, with a strong focus on the most vulnerable, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By understanding how gender norms influence young people’s lives, GAGE provides invaluable insights to inform policies and programs at every level. The program has already made significant impacts. GAGE evidence was instrumental in shaping Ethiopia's first National Plan on Adolescent and Sexual Reproductive Health and enhancing UNICEF’s Jordan Hajati Cash for Education program. Beyond policy change, GAGE elevates youth voices through their podcast series, exploring topics like civic engagement, activism, and leadership. In crisis contexts like Gaza, GAGE advocates for the inclusion of adolescents in peace processes, addressing the severe mental health challenges and social isolation faced by young people, particularly girls. GAGE also fosters skill development and research opportunities for youth, encouraging young researchers to publish their work. Impressively, around half of GAGE’s outputs have co-authors from the Global South. 👉 Learn more about GAGE’s impactful work by following the Youth Inclusion link on our Linktree. 🔗🔗

The latest #R2AImpactPractitioners post features an article by Karen Bell and Mark Reed on the Tree of Participation (ToP) model, a groundbreaking framework designed to enhance inclusive decision-making. By identifying 12 key factors and 7 contextual elements, ToP empowers marginalized groups and ensures processes that are inclusive, accountable, and balanced in power dynamics. The model uses a tree metaphor to illustrate its phases: roots (pre-process), branches (process), and leaves (post-process), all interconnected within their context. Discover more by following the #R2Aimpactpractitioners link in our linktree 👉🔗

Research To Action (R2A) is a learning platform for anyone interested in maximising the impact of research and capturing evidence of impact.

The site publishes practical resources on a range of topics including research uptake, communications, policy influence and monitoring and evaluation. It captures the experiences of practitioners and researchers working on these topics and facilitates conversations between this global community through a range of social media platforms.

R2A is produced by a small editorial team, led by CommsConsult . We welcome suggestions for and contributions to the site.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Our contributors

Browse all authors

Friends and partners

- Global Development Network (GDN)

- Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

- International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie)

- On Think Tanks

- Politics & Ideas

- Research for Development (R4D)

- Research Impact

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Can Oncol Nurs J

- v.27(3); Summer 2017

Communicating your research

Several years of Research Reflections have provided instruction and supportive guidance to assist both novice and advanced scholars in conducting and appraising nursing research. From developing a strong research question to critically evaluating the quality of a published study, the ultimate purpose of nursing research is to disseminate findings in order to have an impact on clinical practice. This objective is contained within the notion of knowledge translation (KT). The Canadian Institutes for Health Research ( CIHR, 2016 ) defines KT as “a dynamic and iterative process” consisting of several steps that foster the creation, and subsequent dissemination, of knowledge for the purpose of improving the health of Canadians by strengthening healthcare services. A short list of additional terms imbued with similar purpose and meaning to KT include knowledge exchange, implementation, research utilization, diffusion, and knowledge transfer. Graham and colleagues (2006) suggested that confusion arising from multiple methodologies and theories for disseminating research findings be clarified to ensure that they are not “lost in knowledge translation” (p.13). Indeed, for both novice and experienced researchers an awkward and frustrating disconnect can exist between generated research knowledge and crucial stakeholders it was meant to inform. Unless research results are communicated with others in a way that is effective and meaningful, potentially important and practice-changing knowledge could slip into the obscurity of a file cabinet or rarely-cited manuscript.

Communication is the key to disseminating research results. Communication is commonly defined as a verbal and nonverbal means of exchanging information, but it also embodies the notion of making connections and building relationships. Therefore, learning how to effectively communicate with a variety of audiences about research is an important skill. The most familiar ways in which nurse researchers communicate research results is by publishing in the academic literature and doing conference presentations (both oral sessions and posters). These strategies do allow the sharing of research findings with specific audiences, and probably target higher level stakeholders but, ultimately, may not generate long-lasting results or improvements in clinical practice. In developing a comprehensive communication plan, researchers are being encouraged to not only be creative in how they communicate findings, but to draw on an evolving body of theory as to how knowledge actually gets taken up in practice.

Effective communication consists of both obtaining an intended outcome, as well as evoking a vivid impression. Ponterotto and Grieger (2007) suggested that improved communication of research results is associated with strong research skills, as well as the use of “thick description” in targeted writing. Indeed, acting like a marketing executive, in order to effectively communicate about research findings, the researcher needs to carefully construct a communications plan that incorporates creative means to target a variety of audiences. Variety is not only the spice of life, it also increases the opportunity for knowledge uptake and dissemination, thereby simultaneously raising the likelihood that research findings will find a way into clinical application.

Some inspired and impactful ways that researchers can communicate their research include:

- performative (or interpretive) dance

- curating exhibits at local museums or art galleries

- authoring colloquial books, magazine articles, and newsletter pieces

- hosting open-forum philosopher’s cafés (for example, the CIHR “café scientifique”)

- writing theatre-based performance pieces

- facilitating focus groups and round table discussions

- doing on-site in-services for nursing staff

- developing blogs and project-specific websites

- utilizing social media platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook

- posting mural or graphic poster projects in public spaces or business lobbies

- creating an “explainer video” to post on YouTube or organizational websites

- producing a colourful brochure or flyer highlighting key points and findings

- partnering with other researchers working on similar research questions

- regular, strategic networking with clinicians and other stakeholders.

This is just a sampling of strategies researchers can utilize to capture the attention of target audiences and disseminate findings in a way that is both resourceful and consequential. Each idea can build and strengthen relationships between the researcher, the research findings, and a greater community that may be interested in this knowledge.

While there is no ‘right’ method to communicate knowledge gleaned from research, it is possible to elevate knowledge translation strategies to maximize impact. Ask yourself, ‘what is the ultimate goal for this research?’ Is it to impact clinical practice, describe a phenomenon, or improve health outcomes? Carefully consider who the best audiences might be to understand and respond to the research findings. Is it front-line clinicians? Students? Advanced practice nurses? By naming the group (or groups) that might benefit from the findings and then marrying their community priorities and values with the overarching goals for research dissemination, the researcher can generate innovative and authentic ideas to sharpen and amplify communication strategies.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Knowledge translation at CIHR. 2016. Jul 28, Retrieved from www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html .

- Graham I, Logan J, Harrison M, Straus S, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2006; 26 :13–24. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ponterotto JG, Grieger I. Effectively communicating qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist. 2007; 35 (3):404–430. doi: 10.1177/0011000006287443. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

2 Plan Your Research Communication Strategy

- Published: August 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Researchers should chart a communication strategy to maximize the benefit of their communications to their research and career. They first need to free themselves from the attitude that they should fear communicating to lay audiences because of the inherent imprecision of lay communications. Also, they should overcome the fear of communicating beyond their peers because their peers might judge them harshly. They should have a “do-tell” strategy that they communicate as much as possible about their goals and research advances. Such a strategy ensures that their work will reach audiences that they might not have expected. They should also have a “strategy of synergy,” in which they use such content as news releases to reach multiple audiences beyond the media.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 5 |

| November 2022 | 9 |

| December 2022 | 6 |

| January 2023 | 9 |

| February 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| April 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 3 |

| August 2023 | 8 |

| September 2023 | 9 |

| October 2023 | 4 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 6 |

| April 2024 | 11 |

| May 2024 | 7 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 9 |

| August 2024 | 4 |

| September 2024 | 22 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Getting Published

- Open Research

- Communicating Research

- Life in Research

- For Editors

- For Peer Reviewers

- Research Integrity

How to communicate your research more effectively

Author: guest contributor.

by Angie Voyles Askham, Content Marketing Intern

"Scientists need to excite the public about their work in part because the public is paying for it, and in part because science has very important things to say about some of the biggest problems society faces."

Stephen S. Hall has been reporting and writing about science for decades. For the past ten years, he's also been helping researchers at New York University improve their writing skills through the school's unique Science Communication Workshops . In our interview below, he explains why the public deserves good science communication and offers some tips for how researchers can make their writing clear and engaging.

How would you descr ibe your role as a science journalist?

I’ve always made a distinction between "science writer" and a writer who happens to be interested in science. That may sound like wordplay, but I think it captures what we aspire to do. Even as specialists, science journalists wear several hats: we explain, we report, we investigate, we step back and provide historical context to scientific developments to help people understand what’s new, why something is controversial, who drove a major innovation. And like any writer, we look for interesting, provocative, and deeply reported ways to tell these stories.

I know you from the science communication workshop that’s offered to NYU graduate students. One of the most important things that I got out of the workshop, at least initially, was training myself out of the stuffy academic voice that I think a lot researchers fall into when writing academic papers. Why do you think scientists fall into this particular trap, and how do you help them get out of it?

Scientists are trained—and rightly so—to describe their work in neutral, objective terms, qualifying all observations and openly acknowledging experimental limitations. Those qualities play very well in scientific papers and talks, but are terrible for effective communication to the general public. In our Science Communication workshops at NYU, we typically see that scientists tend to communicate in dense, formal and cautious language; they tell their audiences too much; they mimic the scientific literature’s affinity for passive voice; and they slip into jargon and what I call “jargonish,” defensive language. Over ten years of conducting workshops, we’ve learned to attack these problems on two fronts: pattern recognition (training people to recognize bad writing/speaking habits and fixing them) and psychological "deprogramming" (it’s okay to leave some details and qualifications out!). And a key ingredient to successful communication is understanding your audience; there is no such thing as the "general public," but rather a bunch of different potential audiences, with different needs and different levels of expertise. We try to educate scientists to recognize the exact audience they're trying to reach—what they need to know and, just as important, what they don't need to know.

What are some other common mistakes that you see researchers making when they’re trying to communicate about their work, either with each other or with the public?

We see the same tendencies over and over again: vocabulary (not simply jargon, but common expressions—such as gene “expression”—that are second-hand within a field, but not clear to non-experts); abstract, complicated explanations rather than using everyday language; sentences that are too long; and “optics” (paragraphs that are too long and appear monolithic to readers). We’ve found that workshops are the perfect setting to play out the process of using everyday language to explain something without sacrificing scientific accuracy.

Why is it important for researchers to be better communicators?

Scientists need to learn to tell their own stories, first and foremost, because society needs their expertise, their perspective, their evidence-based problem solving skills for the future. But the lay public, especially in an era where every fact seems up for grabs, needs to be reminded of what the scientific method is: using critical thinking and rigorous analysis of facts to reach evidence-based conclusions. Scientists need to excite the public about their work in part because the public is paying for it, and in part because science has very important things to say about some of the biggest problems society faces—climate change, medical care, advanced technologies like artificial intelligence, among many other issues. As climate scientist Michael Mann said in a celebrated 2014 New York Times OpEd, scientists can no longer stay on the sidelines in these important public debates.

As a science journalist, part of your job is to hunt for interesting stories to tell. How can scientists make their work more accessible to people like you—or to other people outside of their specific area of research—so that their stories are told more widely?

The key word in your question is “stories.” Think like a writer. What’s the story behind your discovery? What were the ups and downs on the way to the finding? Where does this fit into a larger history of science narrative? Was there a funny incident or episode in the work (humor is a great way to draw and sustain public interest)? Was there a conflict or competition that makes the work even more interesting? Is there a compelling historical or contemporary figure involved that will help you humanize the science? It's been our-longstanding belief that scientists have a great intuitive feel for good storytelling (we incorporate narrative training in our workshops), but just don’t think about it when it comes to describing their own work. The other key thing is to explain why your research matters.

One of the ways that many researchers try to share their work is through Twitter, but I noticed that on the NYU website it says you’re a Twitter conscientious objector. Why is that? What effect do you think Twitter has had on science communication and journalism in general?

I actually think Twitter can be a great tool for science communication, and many of my colleagues use it deftly. I tend to gravitate toward stories that everyone is not talking about, so Twitter doesn’t help much in that regard. The larger reason I’m a Twitter “refusenik,” as my colleague Dan Fagin sometimes calls me, is that I think the technology has been widely abused to disseminate misinformation, intimidate enemies, and subvert democratic norms; I don’t use it primarily for those reasons.

Are there any other tips that you can offer researchers who want to be better communicators and just aren’t sure where to start?

One first step might be to see if your institution offers any communication training and to take advantage of those programs; if not, think about how you might establish a program. We’ve posted a few of the things we’ve learned at NYU on our website ; we’ve also established a publishing platform for science communicators at NYU called the Cooper Square Review , which is a good way for scientists to get experience publishing their own work and reaching a larger public.

Stephen S. Hall has been reporting and writing about science for nearly 30 years. In addition to numerous cover stories in the New York Times Magazine, where he also served as a Story Editor and Contributing Writer, his work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, and a number of other outlets. He is also the author of six non-fiction books about contemporary science. In addition to teaching the Science Communication Workshops at NYU, he also teaches for NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and has taught graduate seminars in science writing and explanatory journalism at Columbia University.

Click here to learn how Springer Nature continues to support the needs of Early Career Researchers.

Guest Contributors include Springer Nature staff and authors, industry experts, society partners, and many others. If you are interested in being a Guest Contributor, please contact us via email: [email protected] .

- early career researchers

- research communication

- Open science

- Tools & Services

- Account Development

- Sales and account contacts

- Professional

- Press office

- Locations & Contact

We are a world leading research, educational and professional publisher. Visit our main website for more information.

- © 2024 Springer Nature

- General terms and conditions

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Your Privacy Choices / Manage Cookies

- Accessibility

- Legal notice

- Help us to improve this site, send feedback.

Communication Research

Doing communication research.

Students often believe that researchers are well organized, meticulous, and academic as they pursue their research projects. The reality of research is that much of it is a hit-and-miss endeavor. Albert Einstein provided wonderful insight to the messy nature of research when he said, “If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?” Because a great deal of Communication research is still exploratory, we are continually developing new and more sophisticated methods to better understand how and why we communicate. Think about all of the advances in communication technologies (snapchat, instagram, etc.) and how quickly they come and go. Communication research can barely keep up with the ongoing changes to human communication.

Researching something as complex as human communication can be an exercise in creativity, patience, and failure. Communication research, while relatively new in many respects, should follow several basic principles to be effective. Similar to other types of research, Communication research should be systematic, rational, self-correcting, self-reflexive, and creative to be of use (Babbie; Bronowski; Buddenbaum; Novak; Copi; Peirce; Reichenbach; Smith; Hughes & Hayhoe).

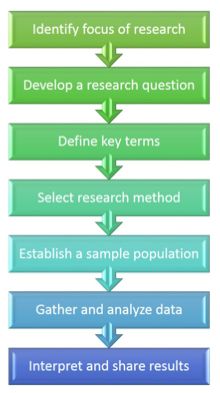

Seven Basic Steps of Research

While research can be messy, there are steps we can follow to avoid some of the pitfalls inherent with any research project. Research doesn’t always work out right, but we do use the following guidelines as a way to keep research focused, as well as detailing our methods so other can replicate them. Let’s look at seven basic steps that help us conduct effective research.

- Identify a focus of research . To conduct research, the first thing you must do is identify what aspect of human communication interests you and make that the focus of inquiry. Most Communication researchers examine things that interest them; such as communication phenomena that they have questions about and want answered. For example, you may be interested in studying conflict between romantic partners. When using a deductive approach to research, one begins by identifying a focus of research and then examining theories and previous research to begin developing and narrowing down a research question.

- Develop a research question(s) . Simply having a focus of study is still too broad to conduct research, and would ultimately end up being an endless process of trial and error. Thus, it is essential to develop very specific research questions. Using our example above, what specific things would you want to know about conflict in romantic relationships? If you simply said you wanted to study conflict in romantic relationships, you would not have a solid focus and would spend a long time conducting your research with no results. However, you could ask, “Do couples use different types of conflict management strategies when they are first dating versus after being in a relationship for a while? It is essential to develop specific questions that guide what you research. It is also important to decide if an answer to your research question already exists somewhere in the plethora of research already conducted. A review of the literature available at your local library may help you decide if others have already asked and answered a similar question. Another convenient resource will be your university’s online database. This database will most likely provide you with resources of previous research through academic journal articles, books, catalogs, and various kinds of other literature and media.

- Define key terms . Using our example, how would you define the terms conflict, romantic relationship, dating, and long-term relationship? While these terms may seem like common sense, you would be surprised how many ways people can interpret the same terms and how particular definitions shape the research. Take the term long-term relationship, for example, what are all of the ways this can be defined? People married for 10 or more years? People living together for five or more years? Those who identify as being monogamous? It is important to consider populations who would be included and excluded from your study based on a particular definition and the resulting generalizability of your findings. Therefore, it is important to identify and set the parameters of what it is you are researching by defining what the key terms mean to you and your research. A research project must be fully operationalized , specifically describing how variables will be observed and measured. This will allow other researchers an opportunity to repeat the process in an attempt to replicate the results. Though more importantly, it will provide additional understanding and credibility to your research.

Communication Research Then

Wilber schramm – the modern father of communication.

Although many aspects of the Communication discipline can be dated to the era of the ancient Greeks, and more specifically to individuals such as Aristotle or Plato, Communication Research really began to develop in the 20th century. James W. Tankard Jr. (1988) states in the article, Wilbur Schramm: Definer of a Field that, “Wilbur Schramm (1907-1987) probably did more to define and establish the field of Communication research and theory than any other person” (p. 1). In 1947 Wilbur Schramm went to the University of Illinois where he founded the first Institute of Communication Research. The Institute’s purpose was, “to apply the methods and disciplines of the social sciences (supported, where necessary, by the fine arts and natural sciences) to the basic problems of press, radio and pictures; to supply verifiable information in those areas of communications where the hunch, the tradition, the theory and thumb have too often ruled; and by so doing to contribute to the better understanding of communications and the maximum use of communications for the public good” (p. 2).

- Select an appropriate research methodology . A methodology is the actual step-by-step process of conducting research. There are various methodologies available for researching communication. Some tend to work better than others for examining particular types of communication phenomena. In our example, would you interview couples, give them a survey, observe them, or conduct some type of experiment? Depending on what you wish to study, you will have to pick a process, or methodology, in order to study it. We’ll discuss examples of methodologies later in this chapter.

- Establish a sample population or data set . It is important to decide who and what you want to study. One criticism of current Communication research is that it often relies on college students enrolled in Communication classes as the sample population. This is an example of convenience sampling. Charles Teddlie and Fen Yu write, “Convenience sampling involves drawing samples that are both easily accessible and willing to participate in a study” (78). One joke in our field is that we know more about college students than anyone else. In all seriousness, it is important that you pick samples that are truly representative of what and who you want to research. If you are concerned about how long-term romantic couples engage in conflict, (remember what we said about definitions) college students may not be the best sample population. Instead, college students might be a good population for examining how romantic couples engage in conflict in the early stages of dating.

- Gather and analyze data . Once you have a research focus, research question(s), key terms, a method, and a sample population, you are ready to gather the actual data that will show you what it is you want to answer in your research question(s). If you have ever filled out a survey in one of your classes, you have helped a researcher gather data to be analyzed in order to answer research questions. The actual “doing” of your methodology will allow you to collect the data you need to know about how romantic couples engage in conflict. For example, one approach to using a survey to collect data is to consider adapting a questionnaire that is already developed. Communication Research Measures II: A Sourcebook is a good resource to find valid instruments for measuring many different aspects of human communication (Rubin et al.).

Communication Research Now

Communicating climate change through creativity.

Communicating climate change has been an increasingly important topic for the past number of years. Today we hear more about the issue in the media than ever. However, “the challenge of climate change communication is thought to require systematic evidence about public attitudes, sophisticated models of behaviour change and the rigorous application of social scientific research” (Buirski). In South Africa, schools, social workers, and psychologist have found ways to change the way young people and children learn about about the issue. Through creatively, “climate change is rendered real through everyday stories, performances, and simple yet authentic ideas through children and school teachers to create a positive social norm” (Buirski). By engaging children’s minds rather than bombarding them with information, we can capture their attention (Buirski).

- Interpret and share results . Simply collecting data does not mean that your research project is complete. Remember, our research leads us to develop and refine theories so we have more sophisticated representations about how our world works. Thus, researchers must interpret the data to see if it tells us anything of significance about how we communicate. If so, we share our research findings to further the body of knowledge we have about human communication. Imagine you completed your study about conflict and romantic couples. Others who are interested in this topic would probably want to see what you discovered in order to help them in their research. Likewise, couples might want to know what you have found in order to help themselves deal with conflict better.

Although these seven steps seem pretty clear on paper, research is rarely that simple. For example, a master’s student conducted research for their Master’s thesis on issues of privacy, ownership and free speech as it relates to using email at work. The last step before obtaining their Master’s degree was to share the results with a committee of professors. The professors began debating the merits of the research findings. Two of the three professors felt that the research had not actually answered the research questions and suggested that the master’s candidate rewrite their two chapters of conclusions. The third professor argued that the author HAD actually answered the research questions, and suggested that an alternative to completely rewriting two chapters would be to rewrite the research questions to more accurately reflect the original intention of the study. This real example demonstrates the reality that, despite trying to account for everything by following the basic steps of research, research is always open to change and modification, even toward the end of the process.

Communication Research and You

Because we have been using the example of conflict between romantic couples, here is an example of communication in action by Thomas Bradbury, Ph.D regarding the study of conflict between romantic partners. What stands out to you? What would you do differently?

Which Conflicts Consume Couples the Most http://www.pbs.org/thisemotionallife/blogs/which-conflicts-consume-couples-most

- Survey of Communication Study. Authored by : Scott T Paynton and Linda K Hahn. Provided by : Humboldt State University. Located at : https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Survey_of_Communication_Study/Preface . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Communicating Research Findings

- First Online: 03 January 2022

Cite this chapter

- Rob Davidson 5 &

- Chandra Makanjee 6

495 Accesses

Research is a scholarship activity and a collective endeavor, and as such, its finding should be disseminated. Research findings, often called research outputs, can be disseminated in many forms including peer-reviewed journal articles (e.g., original research, case reports, and review articles) and conference presentations (oral and poster presentations). There are many other options, such as book chapters, educational materials, reports of teaching practices, curriculum description, videos, media (newspapers/radio/television), and websites. Irrespective of the approach that is chosen as the mode of communicating, all modes of communication entail some basic organizational aspects of dissemination processes that are common. These are to define research project objectives, map potential target audience(s), relay target messages, define mode of communication/engagement, and create a dissemination plan.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Transferability and Communication of Results

True Dissemination of Knowledge Doesn’t Gather Dust on a Library Shelf

Dissemination

Bavdekar, S. B., Vyas, S., & Anand, V. (2017). Creating posters for effective scientific communication. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 65 (8), 82–88.

PubMed Google Scholar

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36 (1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0486

Article Google Scholar

Gopal, A., Redman, M., Cox, D., Foreman, D., Elsey, E., & Fleming, S. (2017). Academic poster design at a national conference: A need for standardised guidance? The Clinical Teacher, 14 (5), 360–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12584

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hoffman, T., Bennett, S., & Del Mar, C. (2017). Evidence-based practice across the health professions, ISBN: 9780729586078 . Elsevier.

Google Scholar

Iny, D. (2012). Four proven strategies for finding a wider audience for your content . Rainmaker Digital. http://www.copyblogger.com/targeted-content-marketing . Accessed January 2021.

Mir, R., Willmott, H., & Greenwood, M. The routledge companion to philosophy in organization studies (pp. 113–124). Routledge.

Myers, M. D. (2013). Qualitative research in business & management (2nd ed.). Sage.

Myers, M. D. (2018). Writing for different audiences. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods (pp. 532–545). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526430212.n31

Chapter Google Scholar

Nikolian, V. C., & Ibrahim, A. M. (2017). What does the future hold for scientific journals? Visual abstracts and other tools for communicating research. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 30 (4), 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604253

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ranse, J., & Hayes, C. (2009). A novice’s guide to preparing and presenting an oral presentation at a scientific conference. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.7.1.151

Rowe, N., & Ilic, D. (2015). Rethinking poster presentations at large-scale scientific meetings—Is it time for the format to evolve? FEBS Journal, 282 , 3661–3668

Richardson, L., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 959–978). Sage.

Tress, G., Tress, B., & Saunders, D. A. (2014). How to write a paper for successful publication in an international peer-reviewed journal. Pacific Conservation Biology, 20 (1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1071/PC140017

Verde Arregoitia, L. D., & González-Suárez, M. (2019). From conference abstract to publication in the conservation science literature. Conservation Biology, 33 (5), 1164–1173. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13296

Wellstead, G., Whitehurst, K., Gundogan, B., & Agha, R. (2017). How to deliver an oral presentation. International Journal of Surgery Oncology, 2 (6), e25. https://doi.org/10.1097/IJ9.0000000000000025

Woolston, C. (2016). Conference presentations: Lead the poster parade. Nature, 536 (7614), 115–117

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Health Science, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia

Rob Davidson

Discipline of Medical Radiation Science, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia

Chandra Makanjee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chandra Makanjee .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Medical Imaging, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Burnaby, BC, Canada

Euclid Seeram

Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Robert Davidson

Brookfield Health Sciences, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Andrew England

Mark F. McEntee

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Davidson, R., Makanjee, C. (2021). Communicating Research Findings. In: Seeram, E., Davidson, R., England, A., McEntee, M.F. (eds) Research for Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79956-4_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79956-4_7

Published : 03 January 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-79955-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-79956-4

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

LOGIN TO YOUR ACCOUNT

Create a new account.

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Request Username

Can't sign in? Forgot your username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Change Password

Your password must have 8 characters or more and contain 3 of the following:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Verify Phone

Your Phone has been verified

- This journal

- This Journal

- sample issues

- publication fees

- latest issues

Considerations for effective science communication

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options.

| Resource | Link |

|---|---|

| and | |

Considerations

1. define what science communication means to you and your research, 2. know—and listen to—your target audience, 3. consider a diverse but coordinated communication portfolio, 4. draft skilled players and build a network, 5. create and seize opportunities, 6. be creative when you communicate, 7. focus on the science in science communication, 8. be an honest broker, 9. understand the science of science communication, 10. think like an entrepreneur, 11. don’t let your colleagues stop you, 12. integrate science communication into your research program, 13. recognize how science communication enhances your science, 14. request science communication funds from grants, 15. strive for bidirectional communication, 16. evaluate, reflect, and be prepared to adapt, acknowledgements, information, published in.

Data Availability Statement

- science engagement

- science outreach

- communication science

- evaluation of science communication

- academic cultures

- professional development

- Integrative Sciences

- Science Communication

Affiliations

Author contributions, competing interests, other metrics, export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

- Karen J. Murchie ,

- Dylan Diomede , and

- Marie-Claire Shanahan

- Natalie M. Sopinka ,

- Laura E. Coristine ,

- Maria C. DeRosa ,

- Chelsea M. Rochman ,

- Brian L. Owens ,

- Steven J. Cooke , and

- Stephen B. Heard

- Jonathan W. Moore ,

- Linda Nowlan ,

- Martin Olszynski ,

- Aerin L. Jacob ,

- Brett Favaro ,

- Lynda Collins ,

- G.L. Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson ,

- Jill Weitz , and

View options

Share options, share the article link.

Copying failed.

Share on social media

Previous article, next article.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals