A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Use the guidelines below to learn about the practice of close reading.

When your teachers or professors ask you to analyze a literary text, they often look for something frequently called close reading. Close reading is deep analysis of how a literary text works; it is both a reading process and something you include in a literary analysis paper, though in a refined form.

Fiction writers and poets build texts out of many central components, including subject, form, and specific word choices. Literary analysis involves examining these components, which allows us to find in small parts of the text clues to help us understand the whole. For example, if an author writes a novel in the form of a personal journal about a character’s daily life, but that journal reads like a series of lab reports, what do we learn about that character? What is the effect of picking a word like “tome” instead of “book”? In effect, you are putting the author’s choices under a microscope.

The process of close reading should produce a lot of questions. It is when you begin to answer these questions that you are ready to participate thoughtfully in class discussion or write a literary analysis paper that makes the most of your close reading work.

Close reading sometimes feels like over-analyzing, but don’t worry. Close reading is a process of finding as much information as you can in order to form as many questions as you can. When it is time to write your paper and formalize your close reading, you will sort through your work to figure out what is most convincing and helpful to the argument you hope to make and, conversely, what seems like a stretch. This guide imagines you are sitting down to read a text for the first time on your way to developing an argument about a text and writing a paper. To give one example of how to do this, we will read the poem “Design” by famous American poet Robert Frost and attend to four major components of literary texts: subject, form, word choice (diction), and theme.

If you want even more information about approaching poems specifically, take a look at our guide: How to Read a Poem .

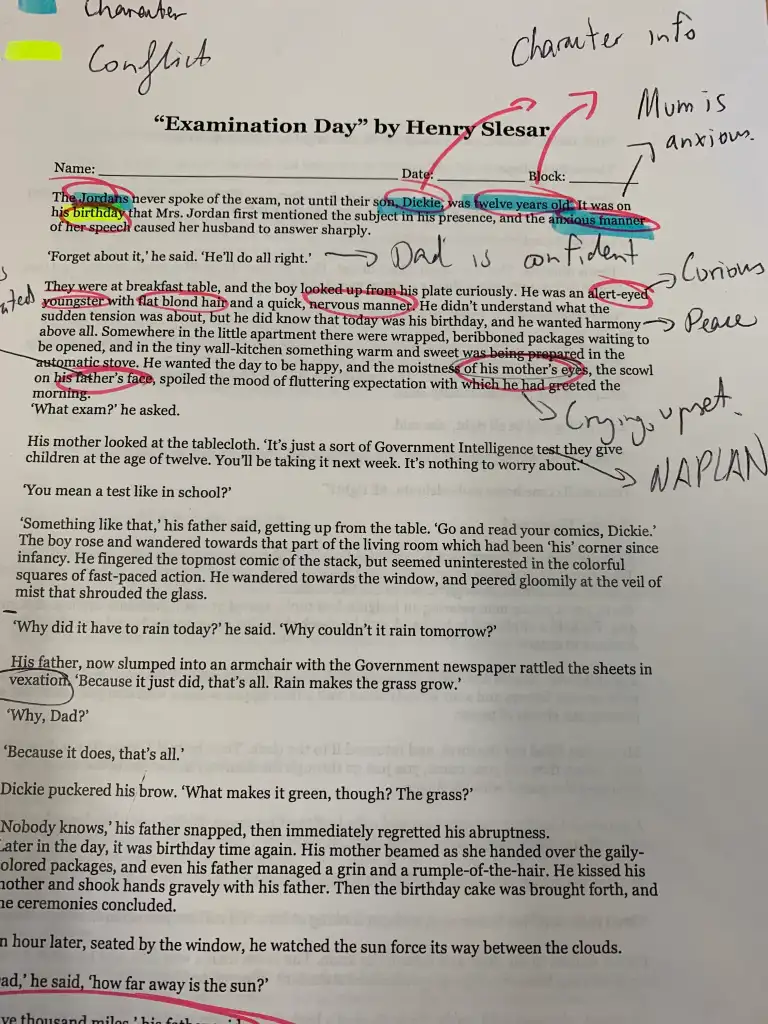

As our guide to reading poetry suggests, have a pencil out when you read a text. Make notes in the margins, underline important words, place question marks where you are confused by something. Of course, if you are reading in a library book, you should keep all your notes on a separate piece of paper. If you are not making marks directly on, in, and beside the text, be sure to note line numbers or even quote portions of the text so you have enough context to remember what you found interesting.

Design I found a dimpled spider, fat and white, On a white heal-all, holding up a moth Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth— Assorted characters of death and blight Mixed ready to begin the morning right, Like the ingredients of a witches’ broth— A snow-drop spider, a flower like a froth, And dead wings carried like a paper kite. What had that flower to do with being white, The wayside blue and innocent heal-all? What brought the kindred spider to that height, Then steered the white moth thither in the night? What but design of darkness to appall?— If design govern in a thing so small.

The subject of a literary text is simply what the text is about. What is its plot? What is its most important topic? What image does it describe? It’s easy to think of novels and stories as having plots, but sometimes it helps to think of poetry as having a kind of plot as well. When you examine the subject of a text, you want to develop some preliminary ideas about the text and make sure you understand its major concerns before you dig deeper.

Observations

In “Design,” the speaker describes a scene: a white spider holding a moth on a white flower. The flower is a heal-all, the blooms of which are usually violet-blue. This heal-all is unusual. The speaker then poses a series of questions, asking why this heal-all is white instead of blue and how the spider and moth found this particular flower. How did this situation arise?

The speaker’s questions seem simple, but they are actually fairly nuanced. We can use them as a guide for our own as we go forward with our close reading.

- Furthering the speaker’s simple “how did this happen,” we might ask, is the scene in this poem a manufactured situation?

- The white moth and white spider each use the atypical white flower as camouflage in search of sanctuary and supper respectively. Did these flora and fauna come together for a purpose?

- Does the speaker have a stance about whether there is a purpose behind the scene? If so, what is it?

- How will other elements of the text relate to the unpleasantness and uncertainty in our first look at the poem’s subject?

After thinking about local questions, we have to zoom out. Ultimately, what is this text about?

Form is how a text is put together. When you look at a text, observe how the author has arranged it. If it is a novel, is it written in the first person? How is the novel divided? If it is a short story, why did the author choose to write short-form fiction instead of a novel or novella? Examining the form of a text can help you develop a starting set of questions in your reading, which then may guide further questions stemming from even closer attention to the specific words the author chooses. A little background research on form and what different forms can mean makes it easier to figure out why and how the author’s choices are important.

Most poems follow rules or principles of form; even free verse poems are marked by the author’s choices in line breaks, rhythm, and rhyme—even if none of these exists, which is a notable choice in itself. Here’s an example of thinking through these elements in “Design.”

In “Design,” Frost chooses an Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet form: fourteen lines in iambic pentameter consisting of an octave (a stanza of eight lines) and a sestet (a stanza of six lines). We will focus on rhyme scheme and stanza structure rather than meter for the purposes of this guide. A typical Italian sonnet has a specific rhyme scheme for the octave:

a b b a a b b a

There’s more variation in the sestet rhymes, but one of the more common schemes is

c d e c d e

Conventionally, the octave introduces a problem or question which the sestet then resolves. The point at which the sonnet goes from the problem/question to the resolution is called the volta, or turn. (Note that we are speaking only in generalities here; there is a great deal of variation.)

Frost uses the usual octave scheme with “-ite”/”-ight” (a) and “oth” (b) sounds: “white,” “moth,” “cloth,” “blight,” “right,” “broth,” “froth,” “kite.” However, his sestet follows an unusual scheme with “-ite”/”-ight” and “all” sounds:

a c a a c c

Now, we have a few questions with which we can start:

- Why use an Italian sonnet?

- Why use an unusual scheme in the sestet?

- What problem/question and resolution (if any) does Frost offer?

- What is the volta in this poem?

- In other words, what is the point?

Italian sonnets have a long tradition; many careful readers recognize the form and know what to expect from his octave, volta, and sestet. Frost seems to do something fairly standard in the octave in presenting a situation; however, the turn Frost makes is not to resolution, but to questions and uncertainty. A white spider sitting on a white flower has killed a white moth.

- How did these elements come together?

- Was the moth’s death random or by design?

- Is one worse than the other?

We can guess right away that Frost’s disruption of the usual purpose of the sestet has something to do with his disruption of its rhyme scheme. Looking even more closely at the text will help us refine our observations and guesses.

Word Choice, or Diction

Looking at the word choice of a text helps us “dig in” ever more deeply. If you are reading something longer, are there certain words that come up again and again? Are there words that stand out? While you are going through this process, it is best for you to assume that every word is important—again, you can decide whether something is really important later.

Even when you read prose, our guide for reading poetry offers good advice: read with a pencil and make notes. Mark the words that stand out, and perhaps write the questions you have in the margins or on a separate piece of paper. If you have ideas that may possibly answer your questions, write those down, too.

Let’s take a look at the first line of “Design”:

I found a dimpled spider, fat and white

The poem starts with something unpleasant: a spider. Then, as we look more closely at the adjectives describing the spider, we may see connotations of something that sounds unhealthy or unnatural. When we imagine spiders, we do not generally picture them dimpled and white; it is an uncommon and decidedly creepy image. There is dissonance between the spider and its descriptors, i.e., what is wrong with this picture? Already we have a question: what is going on with this spider?

We should look for additional clues further on in the text. The next two lines develop the image of the unusual, unpleasant-sounding spider:

On a white heal-all, holding up a moth Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth—

Now we have a white flower (a heal-all, which usually has a violet-blue flower) and a white moth in addition to our white spider. Heal-alls have medicinal properties, as their name suggests, but this one seems to have a genetic mutation—perhaps like the spider? Does the mutation that changes the heal-all’s color also change its beneficial properties—could it be poisonous rather than curative? A white moth doesn’t seem remarkable, but it is “Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth,” or like manmade fabric that is artificially “rigid” rather than smooth and flowing like we imagine satin to be. We might think for a moment of a shroud or the lining of a coffin, but even that is awry, for neither should be stiff with death.

The first three lines of the poem’s octave introduce unpleasant natural images “of death and blight” (as the speaker puts it in line four). The flower and moth disrupt expectations: the heal-all is white instead of “blue and innocent,” and the moth is reduced to “rigid satin cloth” or “dead wings carried like a paper kite.” We might expect a spider to be unpleasant and deadly; the poem’s spider also has an unusual and unhealthy appearance.

- The focus on whiteness in these lines has more to do with death than purity—can we understand that whiteness as being corpse-like rather than virtuous?

Well before the volta, Frost makes a “turn” away from nature as a retreat and haven; instead, he unearths its inherent dangers, making nature menacing. From three lines alone, we have a number of questions:

- Will whiteness play a role in the rest of the poem?

- How does “design”—an arrangement of these circumstances—fit with a scene of death?

- What other juxtapositions might we encounter?

These disruptions and dissonances recollect Frost’s alteration to the standard Italian sonnet form: finding the ways and places in which form and word choice go together will help us begin to unravel some larger concepts the poem itself addresses.

Put simply, themes are major ideas in a text. Many texts, especially longer forms like novels and plays, have multiple themes. That’s good news when you are close reading because it means there are many different ways you can think through the questions you develop.

So far in our reading of “Design,” our questions revolve around disruption: disruption of form, disruption of expectations in the description of certain images. Discovering a concept or idea that links multiple questions or observations you have made is the beginning of a discovery of theme.

What is happening with disruption in “Design”? What point is Frost making? Observations about other elements in the text help you address the idea of disruption in more depth. Here is where we look back at the work we have already done: What is the text about? What is notable about the form, and how does it support or undermine what the words say? Does the specific language of the text highlight, or redirect, certain ideas?

In this example, we are looking to determine what kind(s) of disruption the poem contains or describes. Rather than “disruption,” we want to see what kind of disruption, or whether indeed Frost uses disruptions in form and language to communicate something opposite: design.

Sample Analysis

After you make notes, formulate questions, and set tentative hypotheses, you must analyze the subject of your close reading. Literary analysis is another process of reading (and writing!) that allows you to make a claim about the text. It is also the point at which you turn a critical eye to your earlier questions and observations to find the most compelling points, discarding the ones that are a “stretch.” By “stretch,” we mean that we must discard points that are fascinating but have no clear connection to the text as a whole. (We recommend a separate document for recording the brilliant ideas that don’t quite fit this time around.)

Here follows an excerpt from a brief analysis of “Design” based on the close reading above. This example focuses on some lines in great detail in order to unpack the meaning and significance of the poem’s language. By commenting on the different elements of close reading we have discussed, it takes the results of our close reading to offer one particular way into the text. (In case you were thinking about using this sample as your own, be warned: it has no thesis and it is easily discoverable on the web. Plus it doesn’t have a title.)

Frost’s speaker brews unlikely associations in the first stanza of the poem. The “Assorted characters of death and blight / Mixed ready to begin the morning right” make of the grotesque scene an equally grotesque mockery of a breakfast cereal (4–5). These lines are almost singsong in meter and it is easy to imagine them set to a radio jingle. A pun on “right”/”rite” slides the “characters of death and blight” into their expected concoction: a “witches’ broth” (6). These juxtapositions—a healthy breakfast that is also a potion for dark magic—are borne out when our “fat and white” spider becomes “a snow-drop”—an early spring flower associated with renewal—and the moth as “dead wings carried like a paper kite” (1, 7, 8). Like the mutant heal-all that hosts the moth’s death, the spider becomes a deadly flower; the harmless moth becomes a child’s toy, but as “dead wings,” more like a puppet made of a skull. The volta offers no resolution for our unsettled expectations. Having observed the scene and detailed its elements in all their unpleasantness, the speaker turns to questions rather than answers. How did “The wayside blue and innocent heal-all” end up white and bleached like a bone (10)? How did its “kindred spider” find the white flower, which was its perfect hiding place (11)? Was the moth, then, also searching for camouflage, only to meet its end? Using another question as a disguise, the speaker offers a hypothesis: “What but design of darkness to appall?” (13). This question sounds rhetorical, as though the only reason for such an unlikely combination of flora and fauna is some “design of darkness.” Some force, the speaker suggests, assembled the white spider, flower, and moth to snuff out the moth’s life. Such a design appalls, or horrifies. We might also consider the speaker asking what other force but dark design could use something as simple as appalling in its other sense (making pale or white) to effect death. However, the poem does not close with a question, but with a statement. The speaker’s “If design govern in a thing so small” establishes a condition for the octave’s questions after the fact (14). There is no point in considering the dark design that brought together “assorted characters of death and blight” if such an event is too minor, too physically small to be the work of some force unknown. Ending on an “if” clause has the effect of rendering the poem still more uncertain in its conclusions: not only are we faced with unanswered questions, we are now not even sure those questions are valid in the first place. Behind the speaker and the disturbing scene, we have Frost and his defiance of our expectations for a Petrarchan sonnet. Like whatever designer may have altered the flower and attracted the spider to kill the moth, the poet built his poem “wrong” with a purpose in mind. Design surely governs in a poem, however small; does Frost also have a dark design? Can we compare a scene in nature to a carefully constructed sonnet?

A Note on Organization

Your goal in a paper about literature is to communicate your best and most interesting ideas to your reader. Depending on the type of paper you have been assigned, your ideas may need to be organized in service of a thesis to which everything should link back. It is best to ask your instructor about the expectations for your paper.

Knowing how to organize these papers can be tricky, in part because there is no single right answer—only more and less effective answers. You may decide to organize your paper thematically, or by tackling each idea sequentially; you may choose to order your ideas by their importance to your argument or to the poem. If you are comparing and contrasting two texts, you might work thematically or by addressing first one text and then the other. One way to approach a text may be to start with the beginning of the novel, story, play, or poem, and work your way toward its end. For example, here is the rough structure of the example above: The author of the sample decided to use the poem itself as an organizational guide, at least for this part of the analysis.

- A paragraph about the octave.

- A paragraph about the volta.

- A paragraph about the penultimate line (13).

- A paragraph about the final line (14).

- A paragraph addressing form that suggests a transition to the next section of the paper.

You will have to decide for yourself the best way to communicate your ideas to your reader. Is it easier to follow your points when you write about each part of the text in detail before moving on? Or is your work clearer when you work through each big idea—the significance of whiteness, the effect of an altered sonnet form, and so on—sequentially?

We suggest you write your paper however is easiest for you then move things around during revision if you need to.

Further Reading

If you really want to master the practice of reading and writing about literature, we recommend Sylvan Barnet and William E. Cain’s wonderful book, A Short Guide to Writing about Literature . Barnet and Cain offer not only definitions and descriptions of processes, but examples of explications and analyses, as well as checklists for you, the author of the paper. The Short Guide is certainly not the only available reference for writing about literature, but it is an excellent guide and reminder for new writers and veterans alike.

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

How to Do a Close Reading

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Close Reading Fundamentals

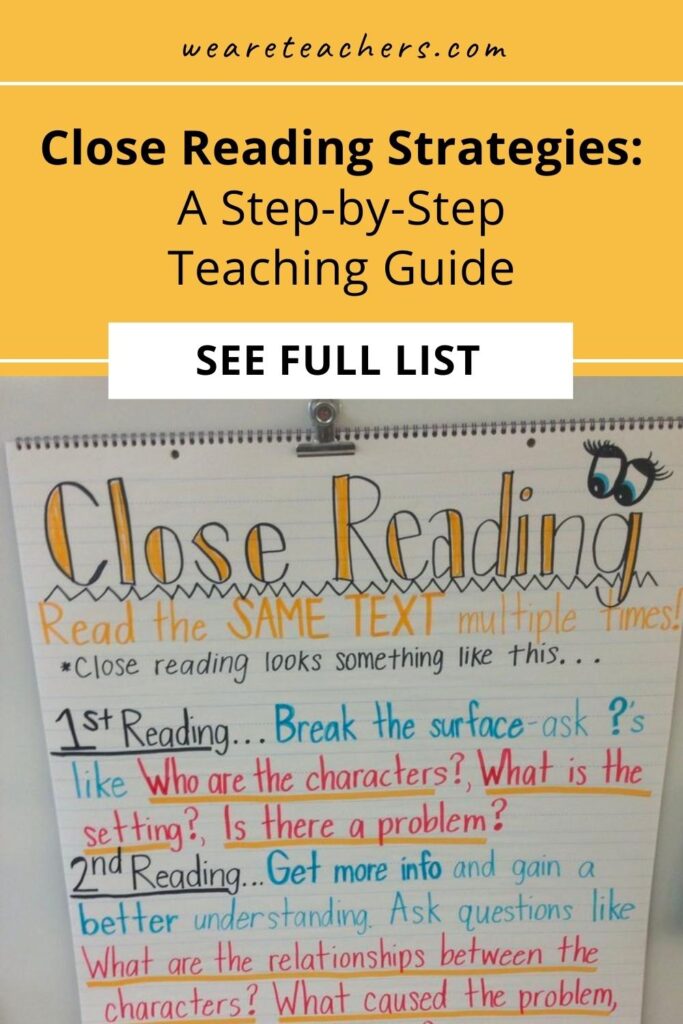

How to choose a passage to close-read, how to approach a close reading, how to annotate a passage, how to improve your close reading, how to practice close reading, how to incorporate close readings into an essay, how to teach close reading, additional resources for advanced students.

Close reading engages with the formal properties of a text—its literary devices, language, structure, and style. Popularized in the mid-twentieth century, this way of reading allows you to interpret a text without outside information such as historical context, author biography, philosophy, or political ideology. It also requires you to put aside your affective (that is, personal and emotional) response to the text, focusing instead on objective study. Why close-read a text? Doing so will increase your understanding of how a piece of writing works, as well as what it means. Perhaps most importantly, close reading can help you develop and support an essay argument. In this guide, you'll learn more about what close reading entails and find strategies for producing precise, creative close readings. We've included a section with resources for teachers, along with a final section with further reading for advanced students.

You might compare close reading to wringing out a wet towel, in which you twist the material repeatedly until you have extracted as much liquid as possible. When you close-read, you'll return to a short passage several times in order to note as many details about its form and content as possible. Use the links below to learn more about close reading's place in literary history and in the classroom.

"Close Reading" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia's relatively short introduction to close reading contains sections on background, examples, and how to teach close reading. You can also click the links on this page to learn more about the literary critics who pioneered the method.

"Close Reading: A Brief Note" (Literariness.org)

This article provides a condensed discussion of what close reading is, how it works, and how it is different from other ways of reading a literary text.

"What Close Reading Actually Means" ( TeachThought )

In this article by an Ed.D., you'll learn what close reading "really means" in the classroom today—a meaning that has shifted significantly from its original place in 20th century literary criticism.

"Close Reading" (Univ. of Washington)

This hand-out from a college writing course defines close reading, suggests why we close-read, and offers tips for close reading successfully, including focusing on language, audience, and scope.

"Glossary Entry on New Criticism" (Poetry Foundation)

If you'd like to read a short introduction to the school of thought that gave rise to close reading, this is the place to go. Poetry Foundation's entry on New Criticism is concise and accessible.

"New Criticism" (Washington State Univ.)

This webpage from a college writing course offers another brief explanation of close reading in relation to New Criticism. It provides some key questions to help you think like a New Critic.

When choosing a passage to close-read, you'll want to look for relatively short bits of text that are rich in detail. The resources below offer more tips and tricks for selecting passages, along with links to pre-selected passages you can print for use at home or in the classroom.

"How to Choose the Perfect Passage for Close Reading" ( We Are Teachers )

This post from a former special education teacher describes six characteristics you might look for when selecting a close reading passage from a novel: beginnings, pivotal plot points, character changes, high-density passages, "Q&A" passages, and "aesthetic" passages.

"Close Reading Passages" (Reading Sage)

Reading Sage provides links to close reading passages you can use as is; alternatively, you could also use them as models for selecting your own passages. The page is divided into sections geared toward elementary, middle school, and early high school students.

"Close Reading" (Univ. of Guelph)

The University of Guelph's guide to close reading contains a short section on how to "Select a Passage." The author suggests that you choose a brief passage.

"Close Reading Advice" (Prezi)

This Prezi was created by an AP English teacher. The opening section on passage selection suggests choosing "thick paragraphs" filled with "figurative language and rich details or description."

Now that you know how to select a passage to analyze, you'll need to familiarize yourself with the textual qualities you should look for when reading. Whether you're approaching a poem, a novel, or a magazine article, details on the level of language (literary devices) and form (formal features) convey meaning. Understanding how a text communicates will help you understand what it is communicating. The links in this section will familiarize you with the tools you need to start a close reading.

Literary Devices

"Literary Devices and Terms" (LitCharts)

LitCharts' dedicated page covers 130+ literary devices. Also known as "rhetorical devices," "figures of speech," or "elements of style," these linguistic constructions are the building blocks of literature. Some of the most common include simile , metaphor , alliteration , and onomatopoeia ; browse the links on LitCharts to learn about many more.

"Rhetorical Device" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia's page on rhetorical devices defines the term in relation to the ancient art of "rhetoric" or persuasive speaking. At the bottom of the page, you'll find links to several online handbooks and lists of rhetorical devices.

"15 Must Know Rhetorical Terms for AP English Literature" ( Albert )

The Albert blog offers this list of 15 rhetorical devices that high school English students should know how to define and spot in a literary text; though geared toward the Advanced Placement exam, its tips are widely applicable.

"The 55 AP Language and Composition Terms You Must Know" (PrepScholar)

This blog post lists 55 terms high school students should learn how to recognize and define for the Advanced Placement exam in English Literature.

Formal Features

In LitCharts' bank of literary devices and terms, you'll also find resources to describe a text's structure and overall character. Some of the most important of these are rhyme , meter , and tone ; browse the page to find more.

"Rhythm" ( Encyclopedia Britannica )

This encyclopedia entry on rhythm and meter offers an in-depth definition of the two most fundamental aspects of poetry.

"How to Analyze Syntax for AP English Literature" ( Albert)

The Albert blog will help you understand what "syntax" is, making a case for why you should pay attention to sentence structure when analyzing a literary text.

"Grammar Basics: Sentence Parts and Sentence Structures" ( ThoughtCo )

This article provides a meticulous overview of the components of a sentence. It's useful if you need to review your parts of speech or if you need to be able to identify things like prepositional phrases.

"Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice" (Wheaton College)

Wheaton College's Writing Center offers this clear, concise discussion of several important formal features. Although it's designed to help essay writers, it will also help you understand and spot these stylistic features in others' work.

Now that you know what rhetorical devices, formal features, and other details to look for, you're ready to find them in a text. For this purpose, it is crucial to annotate (write notes) as you read and re-read. Each time you return to the text, you'll likely notice something new; these observations will form the basis of your close reading. The resources in this section offer some concrete strategies for annotating literary texts.

"How to Annotate a Text" (LitCharts)

Begin by consulting our How to Annotate a Text guide. This collection of links and resources is helpful for short passages (that is, those for close reading) as well as longer works, like whole novels or poems.

"Annotation Guide" (Covington Catholic High School)

This hand-out from a high school teacher will help you understand why we annotate, and how to annotate a text successfully. You might choose to incorporate some of the interpretive notes and symbols suggested here.

"Annotating Literature" (New Canaan Public Schools)

This one-page, introductory resource provides a list of 10 items you should look for when reading a text, including attitude and theme.

"Purposeful Annotation" (Dave Stuart Jr.)

This article from a high school teacher's blog describes the author's top close reading strategy: purposeful annotation. In fact, this teacher more or less equates close reading with annotation.

Looking for ways to improve your close reading? The articles, guides, and videos in this section will expose you to various methods of close reading, as well as practice exercises. No two people read exactly the same way. Whatever your level of expertise, it can be useful to broaden your skill set by testing the techniques suggested by the resources below.

"How to Do a Close Reading" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, part of Harvard's comprehensive "Strategies for Essay Writing Guide," describes three steps to a successful close reading. You will want to return to this resource when incorporating your close reading into an essay.

"A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis" (Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center)

Working through this guide from another college writing center will help you move through the process of close reading a text. You'll find a sample analysis of Robert Frost's "Design" at the end.

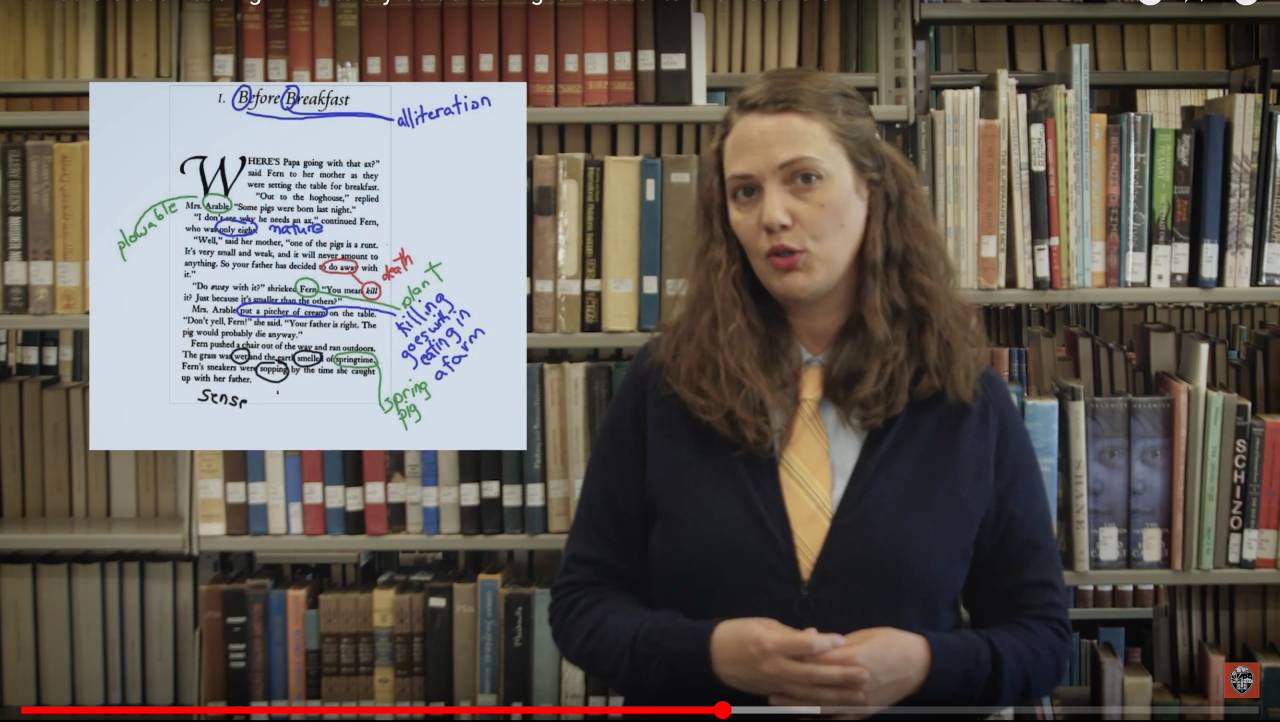

"How to Do a Close Reading of a Text" (YouTube)

This four-minute video from the "Literacy and Math Ideas" channel offers a number of helpful tips for reading a text closely in accordance with Common Core standards.

"Poetry: Close Reading" (Purdue OWL)

Short, dense poems are a natural fit for the close reading approach. This page from the Purdue Online Writing Lab takes you step-by-step through an analysis of Shakespeare's Sonnet 116.

"Steps for Close Reading or Explication de Texte" ( The Literary Link )

This page, which mentions close reading's close relationship to the French formalist method of "explication de texte," shares "12 Steps to Literary Awareness."

You can practice your close reading skills by reading, re-reading and annotating any brief passage of text. The resources below will get you started by offering pre-selected passages and questions to guide your reading. You'll find links to resources that are designed for students of all levels, from elementary school through college.

"Notes on Close Reading" (MIT Open Courseware)

This resource describes steps you can work through when close reading, providing a passage from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein for you to test your skills.

"Close Reading Practice Worksheets" (Gillian Duff's English Resources)

Here, you'll find 10 close reading-centered worksheets you can download and print. The "higher-close-reading-formula" link at the bottom of the page provides a chart with even more steps and strategies for close reading.

"Close Reading Activities" (Education World)

The four activities described on this page are best suited to elementary and middle school students. Under each heading is a link to handouts or detailed descriptions of the activity.

"Close Reading Practice Passages: High School" (Varsity Tutors)

This webpage from Varsity Tutors contains over a dozen links to close reading passages and exercises, including several resources that focus on close-reading satire.

"Benjamin Franklin's Satire of Witch Hunting" (America in Class)

This page contains both a "teacher's guide" and "student version" to interpreting Benjamin Franklin's satire of a witch trial. The thirteen close reading questions on the right side of the page will help you analyze the text thoroughly.

Whether you're writing a research paper or an essay, close reading can help you build an argument. Careful analysis of your primary texts allows you to draw out meanings you want to emphasize, thereby supporting your central claim. The resources in this section introduce you to strategies suited to various common writing assignments.

"How to Write a Research Paper" (LitCharts)

The resources in this guide will help you learn to formulate a thesis, organize evidence, write an outline, and draft a research paper, one of the two most common assignments in which you might incorporate close reading.

"How to Write an Essay" (LitCharts)

In this guide, you'll learn how to plan, draft, and revise an essay, whether for the classroom or as a take-home assignment. Close reading goes hand in hand with the brainstorming and drafting processes for essay writing.

"Guide to the Close Reading Essay" (Univ. of Warwick)

This guide was designed for undergraduates, and assumes prior knowledge of formal features and rhetorical devices one might find in a poem. High schoolers will find it useful after addressing the "elements of a close reading" section above.

"Beginning the Academic Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Harvard's guide discusses the broader category of the "academic essay." Here, the author assumes that your essay's close readings will be accompanied by context and evidence from secondary sources.

A Short Guide to Writing About Literature (Amazon)

Sylvan Barnet and William E. Cain emphasize that writing is a process. In their book, you'll find definitions of important literary terms, examples of successful explications of literary texts, and checklists for essay writers.

Due in part to the Common Core's emphasis on close reading skills, resources for teaching students how to close-read abound. Here, you'll find a wealth of information on how and why we teach students to close-read texts. The first section includes links to activities, exercises, and complete lesson plans. The second section offers background material on the method, along with strategies for implementing close reading in the classroom.

Lesson Plans and Activities

"Four Lessons for Introducing the Fundamental Steps of Close Reading" (Corwin)

Here, Corwin has made the second chapter of Nancy Akhavan's The Nonfiction Now Lesson Bank, Grades 4 – 8 available online. You'll find four sample lessons to use in the elementary or middle school classroom

"Sonic Patterns: Exploring Poetic Techniques Through Close Reading" ( ReadWriteThink )

This lesson plan for high school students includes material for five 50-minute sessions on sonic patterns (including consonance, assonance, and alliteration). The literary text at hand is Robert Hayden's "Those Winter Sundays."

"Close Reading of a Short Text: Complete Lesson" (McGraw Hill via YouTube)

This eight-minute video describes a complete lesson in which a teacher models close reading of a short text and offers guiding questions.

"Close Reading Model Lessons" (Achieve the Core)

These three model lessons on close reading will help you determine what makes a text "appropriately complex" for the grade level you teach.

Close Reading Bundle (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This top-rated bundle of close reading resources was designed for the middle school classroom. It contains over 150 pages of worksheets, complete lesson plans, and literacy center ideas.

"10 Intriguing Photos to Teach Close Reading and Visual Thinking Skills" ( The New York Times )

The New York Times' s Learning Network has gathered 10 photos from the "What's Going on in This Picture" series that teachers can use to help students develop analytical and visual thinking skills.

"The Close Reading Essay" (Brandeis Univ.)

Brandeis University's writing program offers this detailed set of guidelines and goals you might use when assigning a close reading essay.

Close Reading Resources (Varsity Tutors)

Varsity Tutors has compiled a list of over twenty links to lesson plans, strategies, and activities for teaching elementary, middle school, and high school students to close read.

Background Material and Teaching Strategies

Falling in Love with Close Reading (Amazon)

Christopher Lehman and Kate Roberts aim to show how close reading can be "rigorous, meaningful, and joyous." It offers a three-step "close reading ritual" and engaging lesson plans.

Notice & Note: Strategies for Close Reading (Amazon)

Kylene Beers (a former Senior Reading Researcher at Yale) and Robert E. Probst (a Professor Emeritus of English Education) introduce six "signposts" readers can use to detect significant moments in a work of literature.

"How to Do a Close Reading" (YouTube)

TeachLikeThis offers this four-minute video on teaching students to close-read by looking at a text's language, narrative, syntax, and context.

"Strategy Guide: Close Reading of a Literary Text" ( ReadWriteThink )

This guide for middle school and high school teachers will help you choose texts that are appropriately complex for the grade level you teach, and offers strategies for planning engaging lessons.

"Close Reading Steps for Success" (Appletastic Learning)

Shelly Rees, a teacher with over 20 years of experience, introduces six helpful steps you can use to help your students engage with challenging reading passages. The article is geared toward elementary and middle school teachers.

"4 Steps to Boost Students' Close Reading Skills" ( Amplify )

Doug Fisher, a professor of educational leadership, suggests using these four steps to help students at any grade level learn how to close read.

Like most tools of literary analysis, close reading has a complex history. It's not necessary to understand the theoretical underpinnings of close reading in order to use this tool. For advanced high school students and college students who ask "why close-read," though, the resources below will serve as useful starting points for discussion.

"Discipline and Parse: The Politics of Close Reading" ( Los Angeles Review of Books )

This book review by a well-known English professor at Columbia provides an engaging, anecdotal introduction to close reading's place in literary history. Robbins points to some of the method's shortcomings, but also elegantly defends it.

"Intentional Fallacy" ( Encyclopedia Britannica )

The literary critics who developed close reading cautioned against judging a text based on the author's intention. This encyclopedia entry offers an expanded definition of this way of reading, called the "intentional fallacy."

"Seven Types of Ambiguity" (Wikipedia)

This Wikipedia article will introduce you to William Empson's Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), one of the foundational texts of New Criticism, the school of thought that theorized close reading.

"What is Distant Reading" ( The New York Times)

This article makes it clear that "close reading" isn't the only way to analyze literary texts. It offers a brief introduction to the "distant reading" method of computational criticism pioneered by Franco Moretti in recent years.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1941 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,925 quotes across 1941 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

BibGuru Blog

Be more productive in school

- Citation Styles

How to do a close reading essay [Updated 2023]

Close reading refers to the process of interpreting a literary work’s meaning by analyzing both its form and content. In this post, we provide you with strategies for close reading that you can apply to your next assignment or analysis.

What is a close reading?

Close reading involves paying attention to a literary work’s language, style, and overall meaning. It includes looking for patterns, repetitions, oddities, and other significant features of a text. Your goal should be to reveal subtleties and complexities beyond an initial reading.

The primary difference between simply reading a work and doing a close reading is that, in the latter, you approach the text as a kind of detective.

When you’re doing a close reading, a literary work becomes a puzzle. And, as a reader, your job is to pull all the pieces together—both what the text says and how it says it.

How do you do a close reading?

Typically, a close reading focuses on a small passage or section of a literary work. Although you should always consider how the selection you’re analyzing fits into the work as a whole, it’s generally not necessary to include lengthy summaries or overviews in a close reading.

There are several aspects of the text to consider in a close reading:

- Literal Content: Even though a close reading should go beyond an analysis of a text’s literal content, every reading should start there. You need to have a firm grasp of the foundational content of a passage before you can analyze it closely. Use the common journalistic questions (Who? What? When? Where? Why?) to establish the basics like plot, character, and setting.

- Tone: What is the tone of the passage you’re examining? How does the tone influence the entire passage? Is it serious, comic, ironic, or something else?

- Characterization: What do you learn about specific characters from the passage? Who is the narrator or speaker? Watch out for language that reveals the motives and feelings of particular characters.

- Structure: What kind of structure does the work utilize? If it’s a poem, is it written in free or blank verse? If you’re working with a novel, does the structure deviate from certain conventions, like straightforward plot or realism? Does the form contribute to the overall meaning?

- Figurative Language: Examine the passage carefully for similes, metaphors, and other types of figurative language. Are there repetitions of certain figures or patterns of opposition? Do certain words or phrases stand in for larger issues?

- Diction: Diction means word choice. You should look up any words that you don’t know in a dictionary and pay attention to the meanings and etymology of words. Never assume that you know a word’s meaning at first glance. Why might the author choose certain words over others?

- Style and Sound: Pay attention to the work’s style. Does the text utilize parallelism? Are there any instances of alliteration or other types of poetic sound? How do these stylistic features contribute to the passage’s overall meaning?

- Context: Consider how the passage you’re reading fits into the work as a whole. Also, does the text refer to historical or cultural information from the world outside of the text? Does the text reference other literary works?

Once you’ve considered the above features of the passage, reflect on its relationship to the work’s larger themes, ideas, and actions. In the end, a close reading allows you to expand your understanding of a text.

Close reading example

Let’s take a look at how this technique works by examining two stanzas from Lorine Niedecker’s poem, “ I rose from marsh mud ”:

I rose from marsh mud, algae, equisetum, willows, sweet green, noisy birds and frogs to see her wed in the rich rich silence of the church, the little white slave-girl in her diamond fronds.

First, we need to consider the stanzas’ literal content. In this case, the poem is about attending a wedding. Next, we should take note of the poem’s form: four-line stanzas, written in free verse.

From there, we need to look more closely at individual words and phrases. For instance, the first stanza discusses how the speaker “rose from marsh mud” and then lists items like “algae, equisetum, willows” and “sweet green,” all of which are plants. Could the speaker have been gardening before attending the wedding?

Now, juxtapose the first stanza with the second: the speaker leaves the natural world of mud and greenness for the “rich/ rich silence of the church.” Note the repetition of the word, “rich,” and how the poem goes on to describe the “little white slave-girl/ in her diamond fronds,” the necessarily “rich” jewelry that the bride wears at her wedding.

Niedecker’s description of the diamond jewelry as “fronds” refers back to the natural world of plants that the speaker left behind. Note also the similarities in sound between the “frogs” of the first stanza and the “fronds” of the second.

We might conclude from a comparison of the two stanzas that, while the “marsh mud” might be full of “noisy/ birds and frogs,” it’s a far better place to be than the “rich/rich silence of the church.”

Ultimately, even a short close reading of Niedecker’s poem reveals layers of meaning that enhance our understanding of the work’s overall message.

How to write a close reading essay

Getting started.

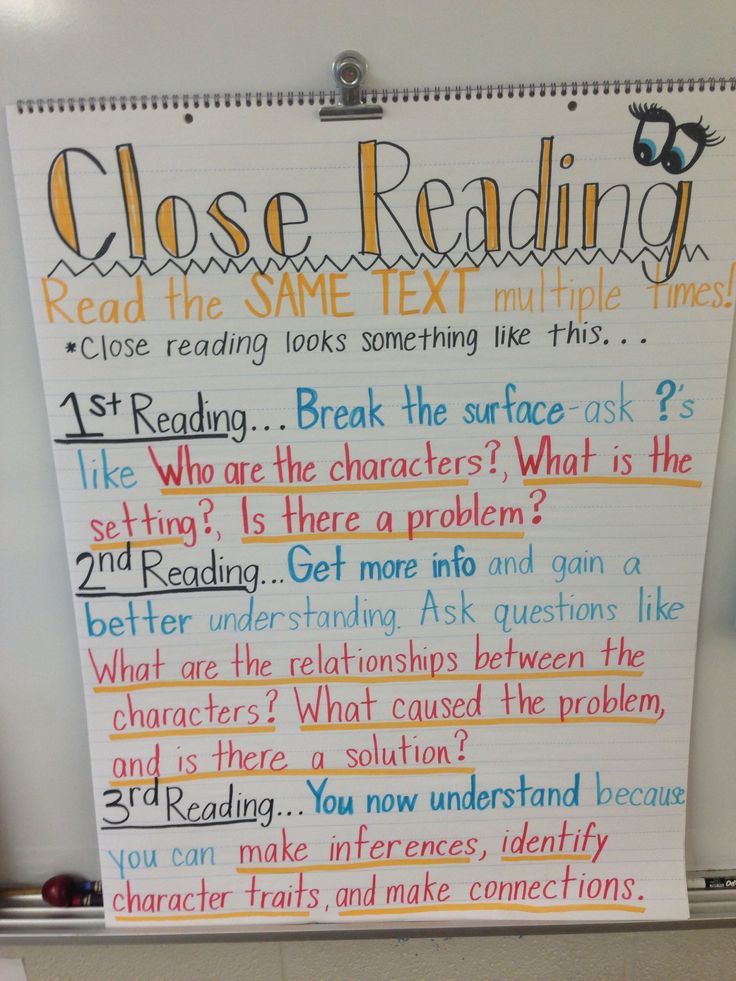

Before you can write your close reading essay, you need to read the text that you plan to examine at least twice (but often more than that). Follow the above guidelines to break down your close reading into multiple parts.

Once you’ve read the text closely and made notes, you can then create a short outline for your essay. Determine how you want to approach to structure of your essay and keep in mind any specific requirements that your instructor may have for the assignment.

Structure and organization

Some close reading essays will simply analyze the text’s form and content without making a specific argument about the text. Other times, your instructor might want you to use a close reading to support an argument. In these cases, you’ll need to include a thesis statement in the introduction to your close reading essay.

You’ll organize your essay using the standard essay format. This includes an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Most of your close reading will be in the body paragraphs.

Formatting and length

The formatting of your close reading essay will depend on what type of citation style that your assignment requires. If you’re writing a close reading for a composition or literature class , you’ll most likely use MLA or Chicago style.

The length of your essay will vary depending on your assignment guidelines and the length and complexity of the text that you’re analyzing. If your close reading is part of a longer paper, then it may only take up a few paragraphs.

Citations and bibliography

Since you will be quoting directly from the text in your close reading essay, you will need to have in-text, parenthetical citations for each quote. You will also need to include a full bibliographic reference for the text you’re analyzing in a bibliography or works cited page.

To save time, use a credible citation generator like BibGuru to create your in-text and bibliographic citations. You can also use our citation guides on MLA and Chicago to determine what you need to include in your citations.

Frequently Asked Questions about how to do a close reading

A successful close reading pays attention to both the form and content of a literary work. This includes: literal content, tone, characterization, structure, figurative language, diction, sound, style, and context.

A close reading essay is a paper that analyzes a text or a portion of a text. It considers both the form and content of the text. The specific format of your close reading essay will depend on your assignment guidelines.

Skimming and close reading are opposite approaches. Skimming involves scanning a text superficially in order to glean the most important points, while close reading means analyzing the details of a text’s language, style, and overall form.

You might begin a close reading by providing some context about the passage’s significance to the work as a whole. You could also briefly summarize the literal content of the section that you’re examining.

The length of your essay will vary depending on your assignment guidelines and the length and complexity of the text that you’re analyzing.

Make your life easier with our productivity and writing resources.

For students and teachers.

- Have your assignments done by seasoned writers. 24/7

- Contact us:

- +1 (213) 221-0069

- [email protected]

How to Write a Close Reading Essay: Full Guide with Examples

writing Close Reading Essay

There is no doubt that close-reading essays are on the rise these days. And for a good reason — it is a powerful technique that can help you make your mark as a student and showcase your understanding of the text.

In this type of writing, readers will read the literary text carefully and interpret it from various points of view. Read on.

Also Read: Does Turnitin Check Other Students’ Papers to Check Similarity

What is a Close Reading Essay?

A close-reading essay is an in-depth analysis of a literary work. It can be used to support a thesis statement or as a research paper.

A close-reading essay focuses on the tiny themes inherent in a literary passage, story, or poem.

The focus of this type of essay is on critical thinking and analysis. The author will look at the small details that make up the overall meaning of a text.

The author will also consider how these tiny themes relate to each other and how they are presented within the text.

The key areas where a close reading essay focuses include:

- Motivation and setting – This includes why the author wrote the piece and their purpose when they chose to write it. You can explore this through character analysis as well as themes that are common across multiple works.

- Characters: While characters may or may not have any significance in an overall plot, they can make up many of the elements discussed in this essay. For example, if you were analyzing Hamlet, then you would want to look at how Hamlet’s character affects his motivation for suicide (which is directly related to his madness) and how it relates to his relationship with Ophelia.

Also Read: How to Answer “to what Extent” Question in Research & Examples

How to Write a Close Reading Essay -Step-By-Step Guide

1. read the selected text at least three additional times.

Analyze the text using your critical thinking skills. What are the author’s main points and purposes? How does the author develop these points? What evidence does he or she use to support these points? How do other writers in the field of the study compare with this author’s views?

Compare and contrast this author’s point of view with other writers in your field of study. What is their purpose in writing? What evidence do they use to support their positions?

How do they compare with this writer’s views?

2. Underline Portions of the Text that you Find Significant or Odd

The purpose of this section is to give the reader a sense of the author’s tone and approach to the subject.

A close-reading essay should be read at least twice, preferably three times. Underline or highlight any portions of the text that you find odd or significant.

Ask yourself: What does this mean? How does this affect my view of the work? What questions do I have now that I didn’t have before?

Take notes on what you think might be important. You may want to write down your questions and observations as they occur to you while reading your essay. Make sure they are hierarchical so they can easily guide your next step in writing about them.

3. State the Conclusions for the Paper

A close-reading essay analyzes a text and the author’s meaning. The key to this type of essay is the ability to conclude a text. It requires the student to think critically about what he/she has read and how it relates to other texts.

The most important aspect of writing a close-reading essay is being able to conclude after reading through a piece of work and analyzing it. The reader should always be able to answer questions like:

- What does this author mean?

- How can I apply this message to my life?

- Is this message relevant in today’s society?

4. Write your Introduction

The purpose of your paper is usually stated in the introduction somewhere (it might be buried in an abstract).

In other words, it’s not enough just to tell readers what they need to know; they also need some motivation to read further if they don’t know why they should read.

5. Write your Body Paragraphs.

A body paragraph is the bulk of your essay. It’s the place where you flesh out your ideas and connect them to the overall topic.

It’s easy to get bogged down in the details when writing a close-reading essay, so it’s important to stay focused on the big picture of what you’re trying to say. Here are some tips for developing your body paragraphs:

- Start with a thesis statement: Make sure that each paragraph starts with an idea or question that relates to the main point of your thesis statement. For example, suppose you’re writing about how human beings have been impacted by technology in society; then, in your first paragraph. In that case, you might want to talk about how computers are changing our lives and what this means for us as individuals and as a culture.

- Link ideas together: Be sure that each paragraph is directly related to the previous one (or else your readers will lose track). Use transition words like “however,” “however,” “in contrast,” and “on the other hand,” or even simply add supporting details from different sources throughout each paragraph.

6. Write your Conclusion

When writing conclusion to your close reading essay, you’ll make a few points about why you think the book is worth reading. You should focus on whether or not the author has succeeded in his or her main objective and whether or not it’s an interesting book.

You should also consider how the author has achieved these goals. Did they succeed because of their writing style? Or did they use an effective structure? Did they make some unique observations that you hadn’t thought of before?

Do you have any specific questions about what was done well in the book? If so, ask them now so that you don’t forget to ask them when it’s time for your argumentative essay!

Also Read: How to Write an Enduring Issues Essay: Guide with Topics and examples

7. Close Reading Essay Examples

Below are three close-reading essay examples on the topic of “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald. The first example is from a student named Brandon:

The main character, Jay Gatsby, is one of the most interesting characters in literature that I have ever read about.

He was a millionaire who married into a family of lower-class people and became friends with their daughter Daisy Buchanan, who had recently graduated from college and moved to New York City, where she met his son Nick Carraway.

Jay Gatsby was so fascinating to me because he had a lot of passion for life; he never gave up on what he wanted, even though he had nothing to back it up.

When I read this book, I learned that some people don’t care about what happens to them or what other people think about them; they just do their own thing and don’t let anything stand in their way of achieving their goals in life (Gatsby).

When I read this book, I also learned about love and hate because there were many different sides to each character’s personality throughout the book (Gatsby).

In conclusion, “The Great Gatsby” is an interesting book.

Example Two

The main character in the novel, Adam Bede, is a strong-willed country boy who looks down upon city folk. He has no interest in being educated and feels that he would rather work on a farm than attend school.

He does not seem to have any particular talent or skill that would make him stand out. However, it is not until he meets the wealthy Miss Lavendar that he can express his talents through writing poetry and music.

The first time Adam meets Miss Lavendar, she sits at a piano playing a piece by Mozart. Adam has never heard music like this before. It is so beautiful that he immediately falls in love with her. The two become friends and eventually marry each other.

However, when Adam becomes famous for his poems about Miss Lavendar, she begins to feel threatened by her new husband’s success. She leaves him for another man named Mr. Thornton. He has money and power but no talent for writing poetry or music like Adam.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams

The play tells the story of a family during the Great Depression in Mississippi. Brick Pollitt has just returned home from World War I where he has been injured in battle and subsequently discharged with a disability pension.

His wife Maggie is expecting their first child, while his son Paul lives in New Orleans where he works as a pianist for a white man named Big Daddy Pollitt who owns a brothel in which Paul performs sexually explicit acts for the patrons at Big Daddy’s establishment called “The Brick House.”

With over 10 years in academia and academic assistance, Alicia Smart is the epitome of excellence in the writing industry. She is our chief editor and in charge of the writing department at Grade Bees.

Related posts

Titles for Essay about Yourself

Good Titles for Essays about yourself: 31 Personal Essay Topics

How to Write a Diagnostic Essay

How to Write a Diagnostic Essay: Meaning and Topics Example

How Scantron Detects Cheating

Scantron Cheating: How it Detects Cheating and Tricks Students Use

- EXPLORE Random Article

How to Write a Close Reading Essay

Last Updated: May 2, 2023 References

This article was co-authored by Bryce Warwick, JD . Bryce Warwick is currently the President of Warwick Strategies, an organization based in the San Francisco Bay Area offering premium, personalized private tutoring for the GMAT, LSAT and GRE. Bryce has a JD from the George Washington University Law School. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been viewed 8,908 times.

With a close-reading essay, you get to take a deep dive into a short passage from a larger text to study how the language, themes, and style create meaning. Writing one of these essays requires you to read the text slowly multiple times while paying attention to both what is being said and how the author is saying it. It’s a great way to hone your reading and analytical skills, and you’ll be surprised at how it can deepen your understanding of a particular book or text.

Reading and Analyzing the Passage

- Think of “close reading" as an opportunity to look underneath the surface. While you may understand a text’s main themes from a single read-through, any given text usually contains multiple complexities in language, character development, and hidden themes that only become clear through close observation.

Tip: Look up words that you aren’t familiar with. Sometimes you might figure out what something means by using context clues, but when in doubt, look it up.

- Alliteration

- Personification

- Onomatopoeia

- What themes are present in the text? Is the passage about, for example, love, or the triumph of good over evil, a character's coming-of-age, or a commentary on social issues?

- What imagery is being used? Which of the 5 senses does the passage involve?

- What is the author’s writing style? Is it descriptive, persuasive, or technical?

- What is the tone of the passage? What emotions do you feel as you read?

- What is the author trying to say? Are they successful?

Tip: Try reading the text out loud. Sometimes hearing the words rather than just seeing them can make a difference in how you understand the language.

- Word choice

- Punctuation

Drafting a Thesis and Outline

- Close-reading essays can get very detailed, and it often is helpful to come back to the “main thing.” This summary can help you focus your thesis in one direction so your essay doesn’t become too broad.

- For example, you could write something like, “The author uses repetition and word choice to create an emotional connection between the reader and the protagonist. This sample from the book exemplifies how the author uses vivid language and atypical syntax throughout the entire text to help put the reader inside of the protagonist’s mind.”

- For example, you may quote a sentence from the passage that uses atypical punctuation to emphasize how the author’s writing style creates a certain cadence.

- Or you may use the repetition of a color or word or theme to explain how the author continually reinforces the overall message.

- There are a lot of different ways to outline an essay. You could use a bullet-pointed list to organize the things you want to write about, or you could plan out, paragraph by paragraph, what you want to say.

- Many people cannot write fast because they do not spend enough time planning what they want to state.

- When you take a couple of extra minutes to plan an essay, it's a lot easier to write because you know how the points should flow together.

- It is also obvious to a reader whether you plan and write the essay or make it up as you write it.

Writing the Essay

- The last thing you want is to write an essay and later on realize that you were required to include an outside source or that your paper was 5 pages longer than it needed to be.

- Some people find it easier to write their introduction once the body of the essay is done.

- The introduction can be a good place to give historical, social, or geographical context.

- Make sure to reference why the proof you’re giving is relevant. It should directly tie back to the main theme of your essay.

- Evidence can be a direct quote from the passage, a summary of that information, or a reference from a secondary source.

- The conclusion isn’t the place to add in new evidence or arguments. Those should all be in the actual body of the essay.

- An impactful close-reading essay will weave together examples, interpretation, and commentary.

- Try reading your essay out loud. You may notice awkward phrases, incorrect grammar, or stilted language that you didn’t before.

Expert Q&A

- Sites like Typely, Grammarly, and ProofreadingTool offer free feedback and edits. Keep in mind that you’ll need to review proposed changes because they may not all be correct for your particular essay. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

Expert Interview

Thanks for reading our article! If you’d like to learn more about completing school assignments, check out our in-depth interview with Bryce Warwick, JD .

- ↑ https://guides.lib.uoguelph.ca/c.php?g=130967&p=4938496

- ↑ https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/how-do-close-reading#

- ↑ https://blogs.umass.edu/honors291g-cdg/how-to-write-a-close-reading-essay/

- ↑ https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/introduction/

- ↑ https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/paragraph-structure/

- ↑ https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/conclusion/

- ↑ https://www.scribbr.com/category/academic-essay/

About this article

Did this article help you?

- About wikiHow

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

"What is Close Reading?" || Definition and Strategies

"what is close reading": a literary guide for english students and teachers.

View the full series: The Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- Oregon State Admissions Info

What is Close Reading? Transcript (English and Spanish Subtitles Available in Video, Click HERE for Spanish Transcript)

By Clare Braun , Oregon State University Senior Lecturer in English

24 October 2022

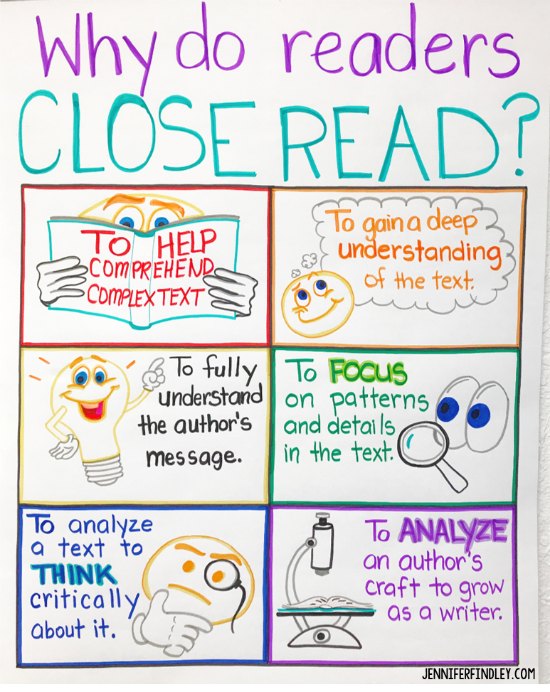

You may have encountered the term “close reading” in high school or university settings. It’s been thrown around a lot in recent years thanks to its inclusion in the Common Core Standards for K12 education in the United States. But the practice of close reading has been around a lot longer than the Common Core, and at this point the term has been used in so many different contexts that its meaning has gotten a little muddled.

So how does the Common Core’s use of “close reading” compare to a literary scholar’s use of the term?

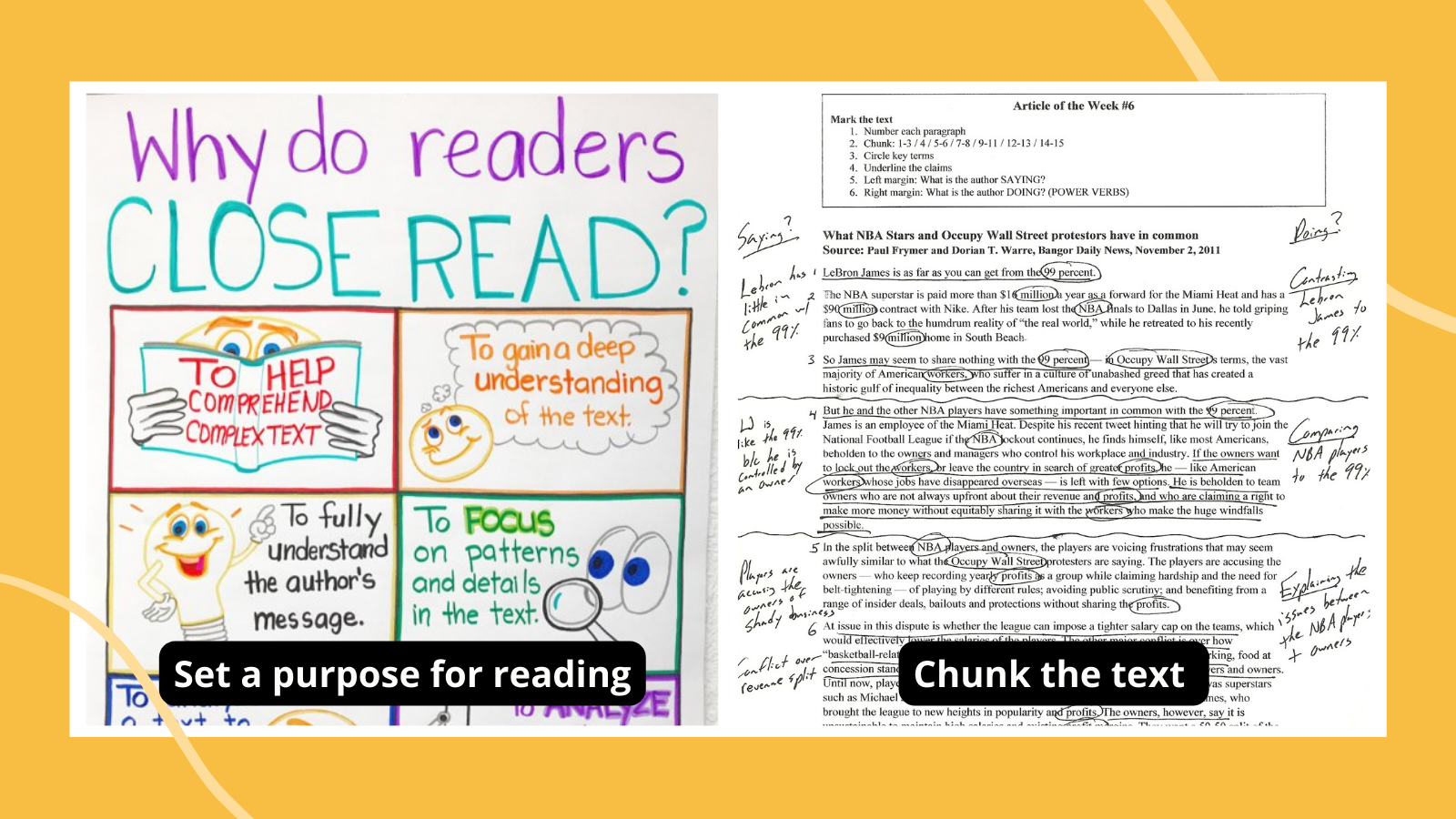

The Common Core Standard mentions citing “specific textual evidence” to “support conclusions drawn from the text,” and this could function as a very basic definition of “close reading” in the way that scholars conceive of the term.

close_reading_common_core.jpg

For scholars, “close reading” is a mode of analysis—one of many possible modes, many of which can be used in conjunction with one another—that moves a reader beyond comprehension of the text to interpretation of the text.

A lot of the time we use close reading to uncover and explore a text’s underlying ideologies—or the ideas embedded in the text’s point of view, ideas that aren’t givens (like the laws of physics) but that are culturally or socially constructed, and usually ideas that aren’t universal even within a given culture or society.

We use close reading to make new knowledge out of our interactions with a text, which is why your instructors in high school and college might ask you to use close reading to write an essay, since the United States higher education system values the production of new knowledge.

So what does it look like to “do” close reading?

When you close read a text, you’re looking at both what the text says (its content), and how the text says what it says—through imagery , figurative language , motif , and so on. You might have noticed that the Oregon State Guide to Literary Terms includes videos on imagery, figurative language, motif, and so on—most of the videos in this series employ close reading!

close_reading_literary_device_examples.jpg

But how do you look at what the text says and how it says what it says?

I like to think of close reading as a process with two major steps, plus a bonus step if you’re using the process to write a paper.

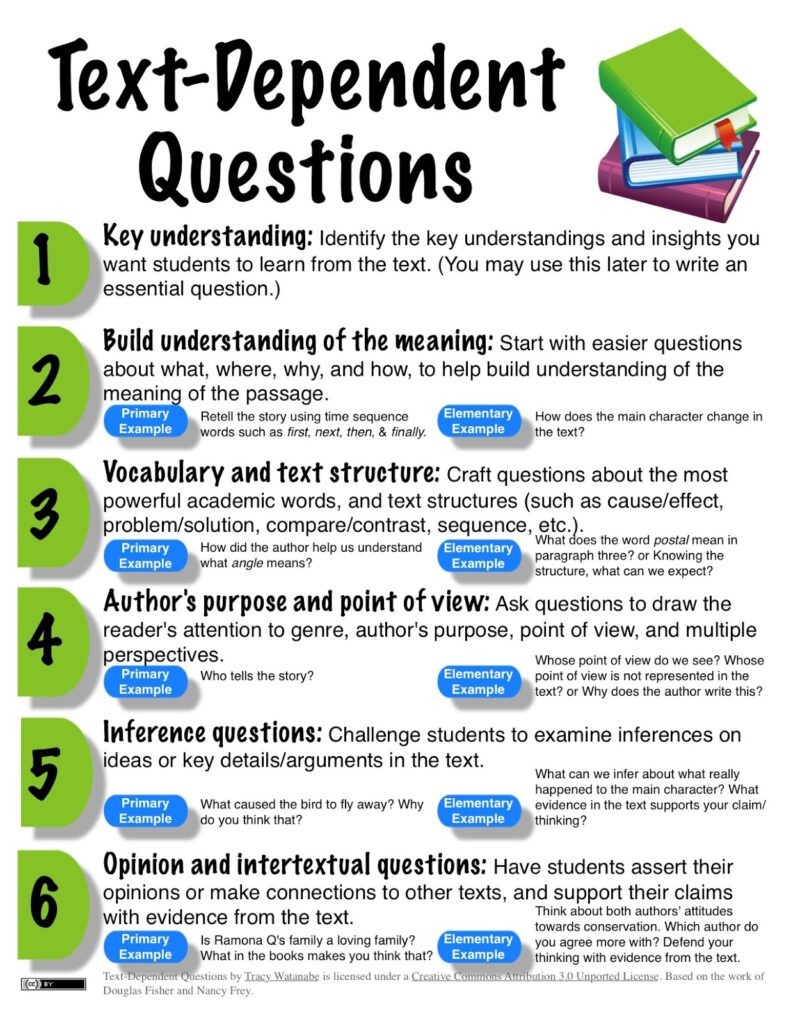

The first step is to read and observe. These observations would include the “specific textual evidence” the Common Core Standards mention—concrete things you can point to in the text. Direct observations are pretty much the defining element that makes close reading close reading.

Usually, you read the text multiple times to make note of as many observations as possible. And speaking of making notes, close reading usually involves some form of notetaking, which might be annotating in the margins or collecting observations in a notebook or computer file.

close_reading_annotation_example.jpg

The second step is to interpret what you notice. Look for patterns in your observations, and look for places where those patterns break. Look for places in the text that snagged your attention, even if at first you don’t know why. What implicit ideas are embedded in these patterns and anomalies? What is significant about your observations, and what conclusions can you draw from them?

These questions are pretty broad, but you can ask yourself more specific questions based on the particular text you’re analyzing and on the general direction of your observations.

One thing I want to clarify is that steps one and two of this process aren’t necessarily sequential, as in, “I have completed my observations and I will now interpret them.” It’s more likely that you’ll interpret as you observe, and continue to observe as you interpret.

close_reading_strategy_example.jpg

If you’re using close reading to write a paper, the third bonus step is to corral your observations and interpretations into a cohesive argument. This may involve cutting out the observations and interpretations that aren’t relevant, and going back to the text for additional observations you can interpret for the argument you’re developing.

So, what isn’t close reading? It’s not focused just on what happened in the text—the content; that’s summary. It doesn’t speculate on the effect of the text on the reader, which is not something you can directly observe in the text. It typically doesn’t require secondary sources, though you can use close reading with other forms of analysis that do rely on secondary sources. It’s not the discovery of the one “right” answer of what a text means, because there are many ways to observe and interpret a text. But it's also not a free-for-all where any reading of a text is correct because everything is interpretation anyway.

Close reading isn’t the only way to usefully and productively engage with a text. But it is often a useful mode of analysis because it is so grounded in the text, digging deeply into its layers of meaning.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Braun, Clare. "What is Close Reading?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 24 Oct. 2022, Oregon State University, liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-close-reading-definition-and-strategies. Accessed [insert date].

View the Full Series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

- Writing Worksheets and Other Writing Resources

- Thesis, Analysis, & Structure

Close Reading!

About the slc.

- Our Mission and Core Values

Close reading is an important tool for writing an essay and doesn't have to be as overwhelming as it sounds. Here are some tips to make it easy and effective.

When do I close read?

Obviously, it's impractical to close read an entire book. Unless your material is fairly short, close read the parts which address an aspect of your essay or assignment. Doing so will help you understand the subtleties in the passage that will help you add analysis to your paper. If you are reading through a book, article, etc. for the first time, you should take small notes as you read instead of a close analysis. This can include noting important passages, passages you don't understand, and passages which might be helpful for a future assignment. Some people like to summarize chapters or pages, so that they don't have to reread material later. This type of quick close reading helps you to understand the material better. It takes a lot less time than it sounds like it does!

How do I close read?

Once you have found a quote to close read, look for what the author's message is , and how she/he gets that message across to readers (you) . The first step is to make sure you understand what is going on: if you have questions, get them answered because the wrong idea here can alter your whole close reading. Next, find:

Themes : repeating ideas discussed in the passage, such as individuality, friendship, etc.

Symbols : one noun standing for another person, place, concept, etc.

Audience : who is the speaker addressing? It can be character(s) in the novel as well as a group of people whom the author wants to read her book.

Tone : the emotional perspective the speaker gives to the passage, always an adjective. Often, the diction and syntax can help you find the tone. Examples are confused, overwhelmed, formal, etc.

Syntax : the sentence structure. The length, level, etc. can change the tone and give you some important clues into the message of the quote.

Diction : the words the author chose. Different words have small differences in meaning, and can bring to mind different settings and atmospheres--this is called connotation.

Speaker : who is actually talking to you in this passage, the narrator. How does the speaker's position, background, etc. affect what she says?

All of these terms will not necessarily be in your quote. Also, they are by no means the only things you can look for while close reading, but they are a good start. These different devices are used by the author to address the two important aspects of close reading underlined above. Look for how a device is used and ask yourself why it is used this way and how it connects to the author's message or what it does for the quote as a whole.

"Our house stood within a few rods of the Chesapeake Bay, whose broad bosom was ever white with sails from every quarter of the habitable globe. Those beautiful vessels, robed in purest white, so delightful to the eye of freemen, were to me so many shrouded ghosts, to terrify and torment me with thoughts of my wretched condition. I have often, in the deep stillness of a summer's Sabbath, stood all alone upon the lofty banks of the noble bay, and traced, with saddened heart and tearful eye, the countless number of sails moving off to the mighty ocean. The sight of these always affected me powerfully. My thoughts would compel utterance; and there, with no audience but the Almighty, I would pour out my soul's complaint, in my rude way, with an apostrophe to the moving multitude of ships. . . ."

--from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass , by Frederick Douglass, p.71. Downloaded August 18, 2011, from Forgotten Books .

Questions for Close Reading

1. Again, summarize the speaker's literal meaning and any themes you see.

2. Imagery, pictures painted by the speaker's words, plays a big role in this passage. What aspects of the imagery are symbols, and what do they stand for? How do the symbols further the themes you found?

3. Who is the speaker, and who is the audience? Can you find different perspectives mentioned here? Why would the speaker include this? How do diction and syntax, or any other aspects of the excerpt that you notice, create the perspectives?

Grace Patil

Student Learning Center, University of California, Berkeley

©2007 UC Regents

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

- Utility Menu

ef0807c43085bac34d8a275e3ff004ed

Classicswrites, a guide to research and writing in the field of classics.

- Harvard Classics

- HarvardWrites

Close Reading

Close reading as analysis.

Close reading is the technique of carefully analyzing a passage’s language, content, structure, and patterns in order to understand what a passage means, what it suggests, and how it connects to the larger work. A close reading delves into what a passage means beyond a superficial level, then links what that passage suggests outward to its broader context. One goal of close reading is to help readers to see facets of the text that they may not have noticed before. To this end, close reading entails “reading out of” a text rather than “reading into” it. Let the text lead, and listen to it.

The goal of close reading is to notice, describe, and interpret details of the text that are already there, rather than to impose your own point of view. As a general rule of thumb, every claim you make should be directly supported by evidence in the text. As the name suggests this technique is best applied to a specific passage or passages rather than a longer piece, almost like a case study.

Use close reading to learn:

- what the passage says

- what the passage implies

- how the passage connects to its context

Why Close Reading?