Diathesis–Stress Model

Oliver Sussman

Neuroscience Researcher

Harvard University Undergraduate

Oliver Sussman is an undergraduate at Harvard University studying neuroscience within the interdisciplinary Mind, Brain, and Behavior program.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

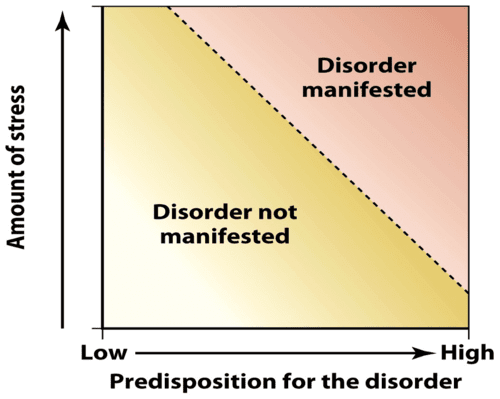

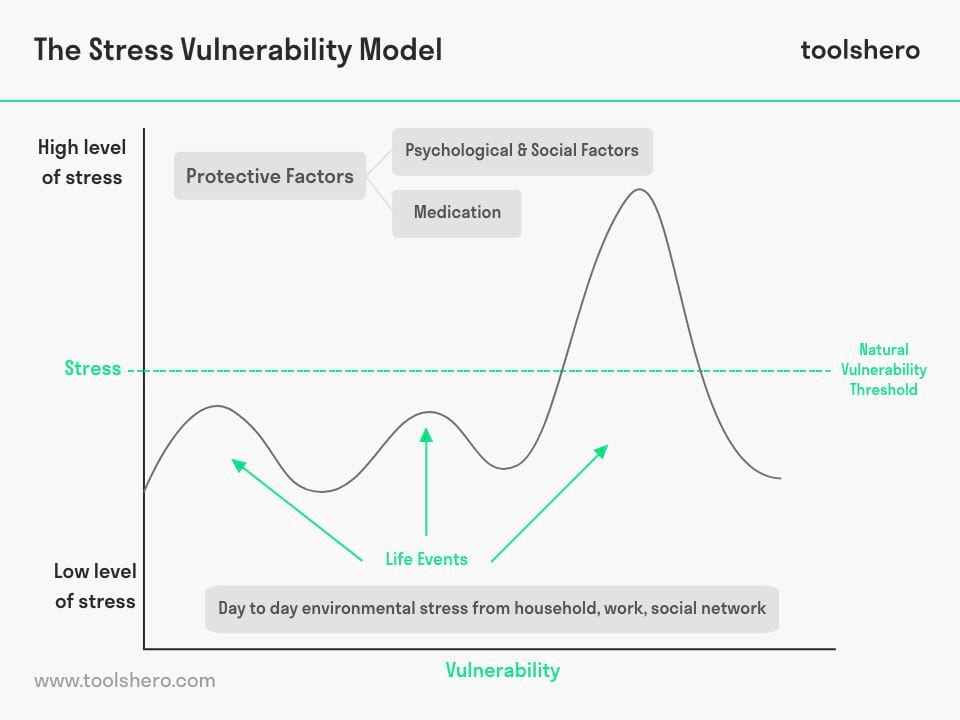

The Diathesis-Stress Model suggests that psychological disorders arise from the interaction of an underlying vulnerability (diathesis) and external stressors. An individual may have a predisposition to a disorder, but it’s the combination of this vulnerability and adverse life events that triggers its manifestation.

What is Diathesis?

The term “diathesis” comes from the Greek word for disposition (“diathesis”). In the context of the diathesis-stress model, this disposition is a factor that makes it more likely that an individual will develop a disorder following a stressful life event.

A diathesis can be a biological factor, like abnormal variations in one or more genes. But other sorts of factors, even if not genetically hard-wired, can also be considered diatheses so long as they form early on and are stable across a person’s life.

For example, traumatic early life experiences, such as the loss of a parent, can act as longstanding predispositions to a psychological disorder. In addition, personality traits like high neuroticism are sometimes also referred to as diatheses.

Finally, diatheses can be situational factors — like living in a low-income household or having a parent with mental illness (Theodore, 2020).

Some of these factors might matter more for some psychological disorders compared to others (for example, a particular genetic variation might increase one’s risk of developing depression but not schizophrenia).

It’s important to note that not all diatheses are created equal. For example, some genetic variations only slightly increase an individual’s risk of a mental disorder, while others increase one’s risk substantially.

As a result, in the diathesis-stress model, different diatheses give rise to different responses to stress.

To conceptualize this, consider the “cup analogy.” Imagine several cups filled with different amounts of marbles; when water is poured into those cups, the cups with more marbles will overflow more easily.

Diatheses are like marbles, and stress is like water: the greater the diathesis, the less stress is needed to cause “overflow” (i.e., give rise to mental illness) (Theodore, 2020).

Diathesis-Stress Model

The diathesis-stress model is a concept in psychiatry and psychopathology that offers a theory of how psychological disorders emerge.

It intervenes in the debate about “ nature vs. nurture ” in psychopathology — whether disorders are predominantly caused by innate biological factors (“nature”) or by social and situational factors (“nurture”) — by providing an account of how both might coincide in giving rise to a disorder.

According to the diathesis-stress model, the emergence of a psychological disorder requires first the existence of a diathesis, or an innate predisposition to that disorder in an individual, and second, stress, or a set of challenging life circumstances that trigger the disorder’s development.

Furthermore, individuals with greater innate predispositions to a disorder may require less stress to trigger that disorder, and vice versa.

In this way, the diathesis-stress model explains how psychological disorders might be related to both nature and nurture and how those two components might interact with one another (Broerman, 2017).

The diathesis-stress model is a modern development of a longstanding debate about the causes of mental illness. This debate began as early as ancient Greece and Rome when theories included imbalances in bodily fluids and interactions with the devil.

Later, this evolved into the “nature vs. nurture” debate. By the late 20th century, it became clear that nature interacted with nurture to produce disorder, and the diathesis-stress model came to the forefront (Theodore, 2020).

The model has been useful in explaining why some individuals with biological dispositions to mental illness do not develop a disorder and why some individuals living through stressful life circumstances nonetheless remain psychologically healthy.

It has also opened the door to research into protective factors: positive elements that counteract the effects of diathesis and stress to prevent the onset of a disorder.

Finally, it has proven particularly useful in the context of specific disorders, such as schizophrenia and depression.

Diathesis and Stress Interactions

According to the diathesis-stress model, diatheses interact with stress to bring about mental illness. In this context, “stress” is an umbrella term encompassing any life event that disrupts an individual’s psychological equilibrium — their normal, healthy regulation of thoughts and emotions.

In the diathesis-stress model, these challenging life events are thought to interact with individuals’ innate dispositions to bring psychological disorders to the surface.

Stress comes in many different forms. It may be a single traumatic event, like the death of a close relative or friend. But stress can also be an ongoing, sustained challenge in one’s life, like a chronic illness or an abusive relationship.

It can even be more mundane, the sorts of things we usually mean when we talk about “stress” — like anxiety from work or school (Theodore, 2020).

These events or situations can profoundly impact individual psychology and interact with diatheses to foment mental illness.

The role of stress in the diathesis-stress model is nuanced. For one, some life circumstances may constitute both a diathesis and stress. For instance, a child with a parent who suffers from mental illness may be genetically predisposed to that illness and may also undergo stress as a result of her parent’s condition (Theodore, 2020).

Second, the timing of stress within an individual’s lifespan may be important; certain disorders are thought to have “windows of vulnerability” during which they are more likely to be brought about by stressful life events (Lokuge, 2011)

Moreover, positive life circumstances, called protective factors, may counteract stress, which decrease the likelihood that a disorder will emerge in response to stress.

Finally, different stresses are thought to play different roles across mental disorders — in other words, a particular form of stressful life event may play an especially pronounced role in depression, or schizophrenia, etc. These last two points will be explored in the sections below.

Protective Factors

Just as negative elements in one’s life make the onset of a psychological disorder more likely, there can also be positive elements that make the onset of a disorder less likely. These positive elements are called protective factors.

Protective factors help explain why some people who have both significant diatheses and stresses nonetheless remain psychologically healthy — in these cases, protective factors prevent a disorder from coming to the surface (Theodore, 2020).

Protective factors can be conditions, meaning beneficial life circumstances that protect against mental illness. They can also be attributes: traits or behaviors of an individual that make them more resilient against psychological disorders (“Protective Factors”).

Conditions that act as protective factors include strong parental and social support and assistance from psychotherapists or counselors. Attributes that act as protective factors include social and emotional competence and the use of healthy coping strategies and stress management techniques (Theodore, 2020).

By itself, the diathesis-stress model does not necessarily include protective factors in its assessment of the causes of psychological disorders.

As a result, the model has been updated in recent years to accommodate protective factors. This updated model is sometimes called the stress-vulnerability-protective factors model (Theodore, 2020).

The diathesis-stress model has proven useful in illuminating the causes of specific psychological disorders. One area where the model has had considerable success is schizophrenia, a disease with both genetic and environmental causes.

Schizophrenia

While schizophrenia has a strong genetic component, some individuals with genetic susceptibilities to the disorder nonetheless remain healthy.

As a result, the view currently held by many psychiatrists is that schizophrenia requires a genetic predisposition in combination with stress later on in life, which then triggers the emergence of the disorder.

Some researchers have also put forth a neural diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia, in which they attempt to explain how brain changes resulting from diatheses and stresses give rise to the disorder (Jones and Fernyhough, 2007).

Thus, the diathesis-stress model does well to explain the origins of schizophrenia and has even been supported by evidence from neuroscience.

The diathesis-stress model has also been used to explain the origins of depression. Similarly to schizophrenia, genetic risk factors for depression have been identified, but not all people with those risk factors go on to develop the disorder.

According to the diathesis-stress model of depression, stressful life events interact with genetic predispositions to bring about depressive symptoms.

This model of depression has been validated by research — a study found there to be an interaction effect between genetic risk factors for depression and scores on an inventory of stressful life events in predicting depressive symptoms (Colodro-Conde et al., 2018).

The model has also proven useful in explaining suicidal behavior. Early models of suicidal behavior tended to focus exclusively on stress, which failed to account for why some individuals exposed to extreme stress nonetheless refrain from engaging in suicidal behavior.

Since suicidal behavior likely also relies on an interaction between genetic and early childhood dispositions with stress later in life, researchers have suggested that efforts to treat and prevent suicidal behavior should utilize a diathesis-stress model (van Heeringen, 2012).

Different psychological disorders have different causes. Some may rely more strongly on hard-wired predispositions, while others may respond more to stressful events later in life.

Nevertheless, the diathesis-stress model has been shown to have wide applicability across many areas of psychiatry.

It offers a powerful explanation of how nature and nurture might come together to give rise to mental illness, a much-needed advancement over earlier theories that took one or the other to be completely determinative.

Broerman, R. (2017). Diathesis-Stress Model. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (pp. 1–3). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_891-1

Colodro-Conde, L., Couvy-Duchesne, B., Zhu, G., Coventry, W. L., Byrne, E. M., Gordon, S., Wright, M. J., Montgomery, G. W., Madden, P. a. F., Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Ripke, S., Eaves, L. J., Heath, A. C., Wray, N. R., Medland, S. E., & Martin, N. G. (2018). A direct test of the diathesis-stress model for depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 23(7), 1590–1596. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.130

DIATHESIS | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com. (n.d.). Lexico Dictionaries | English. Retrieved February 23, 2022, from https://www.lexico.com/definition/diathesis

Jones, S. R., & Fernyhough, C. (2007). A new look at the neural diathesis–stress model of schizophrenia: The primacy of social-evaluative and uncontrollable situations. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 33(5), 1171–1177. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbl058

Lokuge, S., Frey, B. N., Foster, J. A., Soares, C. N., & Steiner, M. (2011). Depression in women: Windows of vulnerability and new insights into the link between estrogen and serotonin. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(11), e1563-1569. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.11com07089

Protective Factors to Promote Well-Being and Prevent Child Abuse & Neglect—Child Welfare Information Gateway. (n.d.). Retrieved February 23, 2022, from https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/promoting/protectfactors/

Theodore. (2020, April). Diathesis-Stress Model (Definition + Examples). Retrieved from https://practicalpie.com/diathesis-stress-model/.

van Heeringen, K. (2012). Stress–Diathesis Model of Suicidal Behavior. In Y. Dwivedi (Ed.), The Neurobiological Basis of Suicide. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK107203/

Walker, E. F., & Diforio, D. (1997). Schizophrenia: a neural diathesis-stress model . Psychological review, 104(4), 667.

Related Articles

Clinical Psychology

A Study Of Social Anxiety And Perceived Social Support

Psychological Impact Of Health Misinformation: A Systematic Review

Sleep Loss and Emotion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Family History Of Autism And ADHD Vary With Recruitment Approach And SES

Measuring And Validating Autistic Burnout

A Systematic Review of Grief and Depression in Adults

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is the Diathesis-Stress Model?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Fizkes / Getty Images

- How It Works

How to Manage Your Stress

The diathesis-stress model is a theory suggesting that mental disorders and medical conditions are caused by a combination of an inherent predisposition and and the person's experience of stress . Also known as the vulnerability-stress model , it is a framework for understanding how existing vulnerabilities and environmental stresses interact to influence mental health conditions.

While the term sounds unwieldy and complex, the phenomenon it explains is relatively easy to understand.

Diathesis and Stress

- Diathesis refers to a predisposition or vulnerability to developing a mental disorder. This can be due to genetic factors , early life experiences, or other biological susceptibilities.

- Stress refers to the environmental factors that trigger the onset of mental illness or exacerbate existing conditions. These can include significant life events, trauma , and daily stressors.

This article discusses the diathesis-stress model, how it explains the onset of different mental health conditions, and how you can use this information to better moderate the stress in your life.

History of the Diathesis Stress Model

The model can trace its origins to the 1950s, although roots of this theory date to much earlier. Paul Meehl, in the 1960s, applied this approach to explain the origins of schizophrenia . Since then, it has also been utilized to understand the development of depression. According to researchers who use this viewpoint, people with a predisposition for depression are more likely to develop the condition when exposed to stress.

This theory was later expanded to include other mental health conditions, including anxiety and eating disorders.

The diathesis-stress model is one of the most widely accepted theories for explaining the etiology of mental disorders.

How the Diathesis Stress Model Works

Everyone has vulnerabilities due to genes, genetic abnormalities, or the complex interaction of various genes. But just because these predispositions exist does not mean that an individual will develop a particular condition.

In many cases, a disorder will only emerge when stress-related pressures trigger the underlying diathesis. This exposure to stress can trigger the mental disorder's onset or worsen existing symptoms.

However, it is essential to note that not everyone with a predisposition will develop a mental disorder, just as not everyone who experiences stress is destined to experience mental illness. The diathesis-stress model is one way to explain why some people are more vulnerable to mental illness than others. It also explains why some people may develop a mental disorder after exposure to stressful life events while others do not.

The heritability of mental illness ranges from around 40% for depression to about 80% for schizophrenia.

However, it is essential to remember that in most cases, no single gene is responsible for causing a mental disorder. Instead, it is often the result of many genes or other biological factors interacting with environmental variables that determine overall risk.

Types of Conditions Linked to Diathesis and Stress

The diathesis-stress model has been utilized to explain the etiology of many different types of mental health conditions, including:

Anxiety Disorders

While the exact causes of anxiety disorders are unknown, genetic vulnerabilities and exposure to stressful life events can play a role. Anxiety disorders tend to run in families, and having an inherited predisposition means that traumatic experiences are more likely to trigger anxiety. Genetics can also impact how people manage stress.

A combination of factors is believed to contribute to the onset of depression , including genetics, a family history of depression, and exposure to stressful life events.

Schizophrenia

Experts suggest that schizophrenia is caused by a combination of genetics and stressful events. For example, around 25% of individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (aka DiGeorge Syndrome) develop schizophrenia, indicating a significant genetic component. Not everyone with this genetic variation experiences schizophrenia, suggesting that environmental factors also play a part.

Eating Disorders

Genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors are believed to contribute to the development of eating disorders. For many people, stressful life events that leave them feeling a loss of control can lead people with inherent vulnerability to extreme behaviors to control weight and food intake.

Uses for the Diathesis Stress Model

The diathesis-stress model has been used to help improve research, diagnosis, and treatment of mental disorders. Some uses for this model include:

- Understanding the causes of mental illness : Where other models of mental illness focus primarily on nature or nurture , the diathesis-stress model suggests that mental disorders are best understood as resulting from biological and environmental influences.

- Reducing the stress that contributes to mental disorders : Because of the emphasis on the role stress plays in causing mental illness, this model encourages the use of stress reduction strategies to help limit disease risk. While genetic and other biological factors cannot be controlled, stress is a modifiable risk factor that people can address through lifestyle changes. This may include stress-relief techniques, such as relaxation and mindfulness .

- Exploring the interactions of biological and environmental influences : The diathesis-stress model is also helpful in understanding the complex interaction of biological and environmental factors in developing mental disorders. It can help guide research to identify the causes of mental illness, ultimately leading to the development of more effective treatments.

- Understanding the impact of genetics and environment : This model helps explain why some people are more likely to develop mental health conditions following stressful events and why others are not.

Impact of the Diathesis-Stress Model

The diathesis-stress model has influenced how researchers investigate mental health conditions. It has helped shift the focus of research from nature vs. nurture debates to a more nuanced understanding of how biological and environmental factors contribute to mental illness.

The diathesis-stress model has also helped change how mental disorders are treated. The model suggests that treatment should reduce stress and address the underlying diathesis to the degree possible. This has led to the use of new therapies, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction , that might mitigate these risks.

The diathesis-stress model is a widely accepted theory with important implications for research and treatment. The model has helped to improve our understanding of mental disorders and develop more effective treatments.

While avoiding all sources of stress is impossible, limiting your stress and developing strong stress management skills may help limit your health risks. Some things you can do include:

- Identify your sources of stress

- Explore ways to avoid or minimize your stress

- Develop healthy coping mechanisms

- Try stress relief techniques such as deep breathing , progressive muscle relaxation , and guided meditation

- Exercise regularly

- Write in a gratitude journal

Making lifestyle changes and developing healthy coping mechanisms can help reduce stress and protect your mental health.

Protective Factors

Stress and genetic factors contribute to increased vulnerability, but protective factors can counteract some of the effects of stress. Some protective factors that can affect the interaction of diathesis and stress include secure attachments , positive relationships, stress management skills, and emotional competence.

Certain traits and characteristics can also make people more resilient to stress. For example, the big five personality traits of extroversion and conscientiousness have been linked to increased resilience.

The diathesis-stress model is a widely accepted theory with important implications for research and treatment. The model suggests that a mental disorder develops when an individual has a vulnerability or predisposition combined with exposure to stressful life events. This exposure can trigger the mental disorder's onset or worsen existing symptoms. The diathesis-stress model has helped to improve our understanding of mental disorders and led to the development of more effective treatments.

Broerman R. Diathesis-stress model . In: Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford TK, eds. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences . Springer International Publishing; 2018:1-3. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_891-1

Kendler KS. A prehistory of the diathesis-stress model: predisposing and exciting causes of insanity in the 19th century . AJP . 2020;177(7):576-588. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19111213

Pettersson E, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, et al. Genetic influences on eight psychiatric disorders based on family data of 4 408 646 full and half-siblings, and genetic data of 333 748 cases and controls . Psychol Med . 2019;49(07):1166-1173. doi:10.1017/S0033291718002039

Daviu N, Bruchas MR, Moghaddam B, Sandi C, Beyeler A. Neurobiological links between stress and anxiety . Neurobiol Stress . 2019 Aug 13;11:100191. doi:10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100191

Generation Scotland, Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Arnau-Soler A, et al. A validation of the diathesis-stress model for depression in Generation Scotland . Transl Psychiatry . 2019;9(1):25. doi:10.1038/s41398-018-0356-7

Cleynen I, Engchuan W, Hestand MS, et al. Genetic contributors to risk of schizophrenia in the presence of a 22q11.2 deletion . Mol Psychiatry . 2021;26(8):4496-4510. doi:10.1038/s41380-020-0654-3

Stice E. Interactive and mediational etiologic models of eating disorder onset: evidence from prospective studies . Annu Rev Clin Psychol . 2016;12(1):359-381. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093317)

Childs E, de Wit H. Regular exercise is associated with emotional resilience to acute stress in healthy adults . Front Physiol . 2014;5:161. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00161

Sharma S, Mustanski B, Dick D, Bolland J, Kertes DA. Protective factors buffer life stress and behavioral health outcomes among high-risk youth . J Abnorm Child Psychol . 2019 Aug;47(8):1289-1301. doi:10.1007/s10802-019-00515-8

de la Fuente J, González-Torres MC, Artuch-Garde R, Vera-Martínez MM, Martínez-Vicente JM, Peralta-S’anchez FJ. Resilience as a buffering variable between the big five components and factors and symptoms of academic stress at university . Front Psychiatry . 2021;12:600240. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.600240

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Diathesis-Stress Model (Definition + Examples)

At the center of many theories in social psychology is the nature/nurture debate. Do we develop a certain personality and make certain choices because it’s in our nature? Or do our experiences alone shape who we become and how we look at the world? I want to look at one particular model that considers both factors. It’s called the Diathesis Stress Model (the Stress-Vulnerability Model.) This takes genetics and personal experiences into account when assessing a person’s likelihood of developing mental disorders.

What Is the Diathesis-Stress Model?

The diathesis-stress model is a theory about how stress and genetics play into the manifestation of different mental disorders and conditions. High stress and high predisposition significantly increase your risk of developing said disorders. But even high stress and low predisposition can increase your risk.

History of the Diathesis Stress Model

Mental disorders are not always easy to identify. It’s not easy to pinpoint a moment when a person becomes depressed. And the causes attributed to mental illnesses have caused some pretty dramatic treatments over time.

In Ancient Rome, for example, Hippocrates connected depression to an excess of “black bile” in the kidney or spleen. A physician named Asclepiades argued against these terms, saying that emotions of grief or hurt caused depression. Asclepiades was pretty close, but his theories soon were thrown out. For centuries after the Ancient Romans, mental disorders were connected to interactions with the devil. Some patients with mental disorders were burned at the stake.

Fast-forward to 1977. At this point, psychologists and doctors believed that more natural factors played into the development of mental disorders. Could it be genes? Could it be emotions? Maybe trauma from childhood, as Freud theorized? What if a combination could explain a disorder like schizophrenia?

How Does the Diathesis-Stress Model Explain Schizophrenia?

Joseph Zubin, a Lithuanian-American psychologist who specialized in the study of schizophrenia, believed that relapses could be predicted using a model. On one axis was diathesis, or vulnerability. On the other axis was stress. The combination of low vulnerability and stress could keep a person from relapsing or showing symptoms.

Zubin’s model, the Diathesis-Stress model, has since been adapted and applied to a range of mental disorders and conditions, including addiction and depression . Let’s go over what these factors mean and how they can help anyone to keep themselves in check.

The Diathesis-Stress Model Cup Analogy

The first part of this model is diathesis. Regarding the diathesis-stress model, “diathesis” is often used interchangeably with “vulnerability.” If someone is more vulnerable to a mental disorder, it might not take a lot of stress for symptoms to start appearing.

Think of this like a cup. In this analogy, diathesis is the marbles in the cup. Stress is water. A cup that is ¼ full of marbles will need quite a bit of water before it starts to spill over. If the cup is ¾ full of marbles, it won’t take that much water. This is how diathesis and stress work.

So what causes diathesis? A few factors may come into play here:

- Genes or biology

- Cognitive factors, such as perception, memory, problem-solving skills, and decision-making abilities

- Trauma or environmental stressors early in life

- Situational factors (living with a parent with mental illness, living in a low-income household, etc.)

Not all of these things are “ natural ” because they are genetic. But these factors tend to stay very present in a person’s life. If a person could move from a low-income household into a more affluent situation, they may be less vulnerable to certain conditions. Moving these “marbles” out of a person’s cup takes a lot. It might be impossible.

Now let’s talk about stress or the “water” in the analogy I used earlier. When stress is piled onto a person’s life, they are more likely to be “triggered” and display symptoms of a mental disorder. Stressors may be things that are generally considered stressful:

- Death in the family

- A global pandemic

Chronic illnesses or ongoing stressors may not be a one-time event but may continue to “fill your cup.” Stressors don’t have to be traumatic or life-altering, either. The stress of graduating high school, studying for exams, or buying a home may also “fill your cup.”

At some point, too much stress can fill anyone’s cup. You do not have to be predisposed to a specific mental disorder to develop one. You do not have to have a family of addicts to become addicted to alcohol or drugs.

It’s important to note that diathesis can cause stress or vice versa. Growing up with the knowledge that a parent has bipolar disorder can be very stressful. That early stress may remain in the body, making a person more vulnerable. Without addressing the issue or seeking treatment, this process can continue to cause more and more stress and vulnerability.

Protective Factors

But what about someone who is predisposed to a specific mental disorder, has a lot of stress, but still manages to go about life without showing any major symptoms?

These people are probably shielded from certain “protective factors.”

In the past 20 years, the diathesis-stress model has been adapted to include these protective factors. You may hear this version of the “stress-vulnerability-protective factors model.” Stressors and diathesis are still present in this model.

Protective factors make stressors easier to handle. These factors may include:

- A positive relationship with parents or children

- A support group

- Help from a counselor or therapist

- Self-awareness or emotional intelligence

- Understanding of stress management techniques

- A good grasp of healthy coping mechanisms or emotional regulation

Example of the Diathesis-Stress Model

An addict, for example, may be predisposed to an addiction and face stress in their marriage and career. With the help of an AA or NA group, they may be able to face those stressors and overcome them without relapsing.

What Does This Mean?

The Diathesis-Stress Model can be used to assess anyone’s risk. But if you take away one lesson about this model, it’s that stress is dangerous. Stress can be hard to avoid, like during a global pandemic or a tragedy out of your control. But if you notice that more stress is coming into your life, assessing what protective factors are present is especially important. Do you have positive relationships that can help you through a stressful time? Do your diet and daily routine contribute to stress or protect you from it? The more protective factors in your life, the more confident you can be in your health and minimize risks.

How to Reduce Stress and Protect Your Mental Health

Stress can feel inevitable. In some ways, it is. Everyone goes through tough times or worries about the future. But you do not have to let that stress control your life. Take action to reduce your stress and create a healthier environment for you and the people around you.

Where Does Stress Come From?

The feeling of being stressed - sweaty palms, a tight chest, etc. - is often the result of hormones entering your bloodstream. When the brain encounters something stressful, it tells the body to release cortisol, adrenaline, and other "stress" hormones. Hormones are chemical messengers. Hormones like cortisol or adrenaline send a specific message throughout the body: we are in danger.

Your brain doesn't have to be in danger to release these hormones. You might be in front of a grizzly bear or think about your crush rejecting you. The response from the brain is the same. Knowing this, you can manage stress in one of two ways: prevent situations from feeling as dire as being in front of a grizzly bear or calm your body down when the hormones start to flow through the bloodstream.

Preventing Stress

Consider your diet and exercise.

Diet and exercise significantly influence the production and release of stress hormones. Consider this: 95% of serotonin, a key neurotransmitter, is produced in the gut. Serotonin plays a crucial role in regulating mood, anxiety, and happiness. It also impacts other functions like sleep, appetite, and digestion.

This fact underscores how closely our physical and mental health are connected. By taking care of your body through proper nutrition and physical activity, you also support your mental well-being, creating a beneficial cycle where treating your body rightfully positively affects your mind and vice versa.

Getting eight hours of sleep won't just help you grow big and strong. Sleep is part of the body's circadian rhythm. This 24-hour cycle helps the body wake up and fall asleep through the release of - you guessed it - hormones. The body releases cortisol in the morning as you get up. Improper sleep schedules mess with the body's intended cortisol production. This can lead to a myriad of health issues , including increased appetite and high blood pressure. Getting proper sleep is one of the best things you can do for your physical and mental health.

Setting Boundaries

Stress often comes from feeling overwhelmed . There are only 24 hours in a day. (And hopefully, you are spending around eight hours sleeping.) It is okay to say "no" to responsibilities, obligations, projects, or even vacations that feel like "too much." The easiest way to handle a stressful schedule is to lighten it!

Handling Stress

Take some time to write down how you are feeling. Journaling allows you to process your emotions using different parts of your brain. You might gain a new perspective on your situation and what solutions you can implement as you write. You do not have to spend a lot of time journaling each day. Sit down for five minutes, write about your day, and see where your words take you.

Practice Mindful Meditation

Stress can become a nasty cycle. You experience stress, so you indulge in unhealthy habits to reduce stress, and then you stress about your unhealthy habits, and you become stressed again. Break that cycle by sitting down, closing your eyes, and meditating. Mindfulness meditation doesn't require you to take a vow of silence or chant mantras for hours a day. You can be mindful by pausing and being aware of your thoughts. As you become aware of your thoughts, you may find that you are working yourself up over something silly - certainly nothing to put you in danger. Sit, breathe deeply, and remind your body that you are not in danger. You may find that your jaw unclenches, your palms start sweating, and your tense muscles loosen!

Reach Out To Your Support Groups

Belonging is listed as one of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. Humans feel the desire to be part of a group that supports them. Humans also want to support other humans! Contact friends if you feel stressed, overwhelmed, or out of control. Reach out to your family. Reach out to a support group of people going through similar things. Meetups for people going through grief, who have family members who are struggling with addiction, or who are addicts themselves can help you. Don't let your stress turn into something more severe. Get help and take care of yourself.

Related posts:

- Hypophyseal Portal System

- Sleep Stages (Light, Deep, REM)

- The 10 Personality Disorders (Clusters A, B, C)

- Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal Axis (HPA)

- What Endocrine Functions take place in the Brain?

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 18 January 2019

A validation of the diathesis-stress model for depression in Generation Scotland

- Aleix Arnau-Soler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9768-0513 1 ,

- Mark J. Adams ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3599-6018 2 ,

- Toni-Kim Clarke 2 ,

- Donald J. MacIntyre ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6963-1335 2 ,

- Keith Milburn 3 ,

- Lauren Navrady ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5625-7962 2 ,

- Generation Scotland, ,

- Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium ,

- Caroline Hayward ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9405-9550 4 ,

- Andrew McIntosh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0198-4588 2 , 5 &

- Pippa A. Thomson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4208-5271 1 , 5

Translational Psychiatry volume 9 , Article number: 25 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

33 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Depression has well-established influences from genetic and environmental risk factors. This has led to the diathesis-stress theory, which assumes a multiplicative gene-by-environment interaction (GxE) effect on risk. Recently, Colodro-Conde et al . empirically tested this theory, using the polygenic risk score for major depressive disorder (PRS, genes) and stressful life events (SLE, environment) effects on depressive symptoms, identifying significant GxE effects with an additive contribution to liability. We have tested the diathesis-stress theory on an independent sample of 4919 individuals. We identified nominally significant positive GxE effects in the full cohort ( R 2 = 0.08%, p = 0.049) and in women ( R 2 = 0.19%, p = 0.017), but not in men ( R 2 = 0.15%, p = 0.07). GxE effects were nominally significant, but only in women, when SLE were split into those in which the respondent plays an active or passive role ( R 2 = 0.15%, p = 0.038; R 2 = 0.16%, p = 0.033, respectively). High PRS increased the risk of depression in participants reporting high numbers of SLE ( p = 2.86 × 10 −4 ). However, in those participants who reported no recent SLE, a higher PRS appeared to increase the risk of depressive symptoms in men ( β = 0.082, p = 0.016) but had a protective effect in women ( β = −0.061, p = 0.037). This difference was nominally significant ( p = 0.017). Our study reinforces the evidence of additional risk in the aetiology of depression due to GxE effects. However, larger sample sizes are required to robustly validate these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Stress-related exposures amplify the effects of genetic susceptibility on depression and anxiety

Patterns of stressful life events and polygenic scores for five mental disorders and neuroticism among adults with depression

Multiple dimensions of stress vs. genetic effects on depression

Introduction.

Stressful life events (SLE) have been consistently recognized as a determinant of depressive symptoms, with many studies reporting significant associations between SLE and major depressive disorder (MDD) 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 . Some studies suggest that severe adversity is present before the onset of illness in over 50% of individuals with depression 8 and may characterize a subtype of cases 9 . However, some individuals facing severe stress never present symptoms of depression 10 . This has led to a suggestion that the interaction between stress and an individual’s vulnerability, or diathesis , is a key element in the development of depressive symptoms. Such vulnerability can be conceived as a set of biological factors that predispose to illness. Several diathesis-stress models have been successfully applied across many psychopathologies 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 .

The diathesis-stress model proposes that a latent diathesis may be activated by stress before psychopathological symptoms manifest. Some levels of diathesis to illness are present in everybody, with a threshold over which symptoms will appear. Exceeding such a threshold depends on the interaction between diathesis and the degree of adversity faced in SLE, which increases the liability to depression beyond the combined additive effects of the diathesis and stress alone 11 . Genetic risk factors can, therefore, be conceived as a genetic diathesis . Thus, this genetically driven effect produced by the diathesis-stress interaction can be seen as a gene-by-environment interaction (GxE).

MDD is characterized by a highly polygenic architecture, composed of common variants with small effect and/or rare variants 16 . Therefore, interactions in depression are also expected to be highly polygenic. In recent years, with the increasing success of genome-wide association studies, GxE studies in depression have shifted towards hypothesis-free genome-wide and polygenic approaches that capture liability to depression using genetic data 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 . Recent advances in genomics and the massive effort from national institutions to collect genetic, clinical and environmental data on large population-based samples now provide an opportunity to empirically test the diathesis-stress model for depression. The construction of polygenic risk scores (PRS) offers a novel paradigm to quantify genetic diathesis into a single genetic measure, allowing us to study GxE effects with more predictive power than any single variant 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 . PRS are genetic indicators of the aggregated number of risk alleles carried by an individual weighted by their allelic effect estimated from genome-wide association studies. This polygenic approach to assessing the diathesis-stress model for depression has been tested using either childhood trauma 17 , 19 , 24 or adult SLE 18 , 23 , 24 as measures of environmental adversity.

Recently, Colodro-Conde et al. 23 provided a direct test of the diathesis-stress model for recent SLE and depressive symptoms. In this study, Colodro-Conde et al. used PRS weighted by the most recent genome-wide meta-analysis conducted by the Psychiatric Genetics Consortium (PGC; N = 159,601), and measures of three environmental exposures: lack of social support, “personal” SLE, and “network” SLE. Colodro-Conde et al. reported a significant additive risk on liability to depression due to a GxE effect in individuals who combine a high genetic predisposition to MDD and a high number of reported “personal” SLE, mainly driven by effects in women. A significant effect of interaction was not detected in males. They found no significant interaction between the genetic diathesis and “network” SLE or social support. They concluded that the effect of stress on risk of depression was dependent on an individual’s diathesis , thus supporting the diathesis-stress theory. In addition, they suggested possible sex-specific differences in the aetiology of depression. However, Colodro-Conde et al. findings have not, to our knowledge, been independently validated.

In the present study, we aim to test the diathesis-stress model in an independent sample of 4919 unrelated white British participants from a further longitudinal follow-up from Generation Scotland, and assess the differences between women and men, using self-reported depressive symptoms and recent SLE.

Materials and methods

Sample description.

Generation Scotland is a family-based population cohort recruited throughout Scotland by a cross-disciplinary collaboration of Scottish medical schools and the National Health Service (NHS) between 2006 and 2011 29 . At baseline, blood and salivary DNA samples from Generation Scotland participants were collected, stored and genotyped at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Edinburgh. Genome-wide genotype data were generated using the Illumina HumanOmniExpressExome-8 v1.0 DNA Analysis BeadChip (San Diego, CA, USA) and Infinium chemistry 30 . The procedures and further details for DNA extraction and genotyping have been extensively described elsewhere 31 , 32 . In 2014, 21,525 participants from Generation Scotland eligible for re-contact were sent self-reported questionnaires as part of a further longitudinal assessment funded by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award “STratifying Resilience and Depression Longitudinally” (STRADL) 33 to collect new and updated mental health questionnaires including psychiatric symptoms and SLE measures. 9618 re-contacted participants from Generation Scotland agreed to provide new measures to the mental health follow-up 33 (44.7% response rate). Duplicate samples, those showing sex discrepancies with phenotypic data, or that had more than 2% missing genotype data, were removed from the sample, as were samples identified as population outliers in principal component analysis (mainly non-Caucasians and Italian ancestry subgroups). In addition, individuals with diagnoses of bipolar disorder, or with missing SLE data, were excluded from the analyses. SNPs with more than 2% of genotypes missing, Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium test p < 1 × 10 −6 , or a minor allele frequency lower than 1%, were excluded. Individuals were then filtered by degree of relatedness (pi-hat < 0.05) using PLINK v1.9 34 , maximizing retention of those participants reporting higher numbers of SLE (see phenotype assessment below). After quality control, the final dataset comprised 4919 unrelated individuals of European ancestry and 560 351 SNPs (mean age at questionnaire: 57.2, s.d. = 12.2, range 22–95; women : n = 2990–60.8%, mean age 56.1, s.d. = 12.4; men : n = 1 929–39.2%, mean age 58.7, s.d. = 11.8). Further details on the recruitment procedure and Generation Scotland profile are described in detail elsewhere 29 , 31 , 35 , 36 , 37 . All participants provided written consent. All components of Generation Scotland and STRADL obtained ethical approval from the Tayside Committee on Medical Research Ethics on behalf of the National Health Service (reference 05/s1401/89). Generation Scotland data is available to researchers on application to the Generation Scotland Access Committee ([email protected]).

Phenotype assessment

Participant self-reported current depressive symptoms through the 28-item scaled version of The General Health Questionnaire 38 , 39 . The General Health Questionnaire is a reliable and validated psychometric screening tool to detect common psychiatric and non-psychotic conditions (General Health Questionnaire Cronbach alpha coefficient: 0.82–0.86) 40 . This consists of 28 items designed to identify whether an individual’s current mental state has changed over the last 2 weeks from their typical state. The questionnaire captures core symptoms of depression through subscales for severe depression, emotional (e.g., anxiety and social dysfunction) and somatic symptoms linked to depression. These subscales are highly correlated 41 and suggest an overall general factor of depression 42 . Participants rated the 28 items on a four-point Likert scale from 0 to 3 to assess its degree or severity 40 (e.g., Have you recently felt that life is entirely hopeless? “Not at all”, “No more than usual”, “Rather more than usual”, “Much more than usual”), resulting on an 84-point scale depression score. The Likert scale, which provides a wider and smoother distribution 40 , may be more sensitive to detect changes in mental status in those participants with chronic conditions or chronic stress who may feel their current symptoms as “usual” 43 , and to detect psychopathology changes as response to stress. The final depression score was log transformed to reduce the effect of positive skew and provide a better approximation to a normal distribution. In addition, participants completed the Composite International Diagnostic Interview–Short Form, which diagnoses lifetime history of MDD according to DSM-IV criteria 44 . The depression score predicted lifetime history of MDD (odd ratio = 1.91, 95% confidence intervals 1.80–2.02, p = 1.55 × 10 −102 , N = 8994), with a 3.8-fold increased odds of having a lifetime history of MDD between participants in the top and bottom deciles, thus supporting the usefulness of the depression score in understanding MDD. To improve interpretation, we scaled the depression score to a mean of 0 when required (Fig. 3 ).

Data from a self-reported questionnaire based on the List of Threating Experiences 45 was used to construct a measure of common SLE over the previous 6 months. The List of Threatening Experiences is a reliable psychometric device to measure psychological “stress” 46 , 47 . It consists of a 12-item questionnaire to assess SLE with considerable long-term contextual effects (e.g., Over last 6 months, did you have a serious problem with a close friend, neighbor or relatives? ). A final score reflecting the total number of SLE (TSLE) ranging from 0 to 12 was constructed by summing the “yes” responses. Additionally, TSLE was split into two categories based on those items measuring SLE in which the individual may play and active role exposure to SLE, and therefore in which the SLE is influenced by genetic factors and thus subject to be “dependent” on an individual’s own behavior or symptoms (DSLE; 6 items, e.g., a serious problem with a close friend, neighbor or relatives may be subject to a respondent’s own behavior), or SLE that are not influenced by genetic factors, likely to be “independent” on a participant’s own behavior (ISLE; 5 items, e.g., a serious illness, injury or assault happening to a close relative is potentially independent of a respondent’s own behavior) 45 , 48 . The item “ Did you/your wife or partner give birth?” was excluded from this categorization. In addition, SLE reported were categorized to investigate the diathesis effect at different levels of exposure, including a group to test the diathesis effect when SLE is not reported. Three levels of SLE reported were defined (0 SLE = “none”, 1 or 2 SLE = “low”, and 3 or more SLE = “high”) to retain a large enough sample size for each group to allow meaningful statistical comparison.

Polygenic profiling and statistical analysis

Polygenic risk scores (PRS) were generated by PRSice 49 , whose functionality relies mostly on PLINK v1.9 34 , and were calculated using the genotype data of Generation Scotland participants (i.e., target sample) and summary statistics for MDD from the PGC-MDD2 GWAS release (July 2016, discovery sample) used by Colodro-Conde et al. 23 , with the added contribution from QIMR cohort and the exclusion of Generation Scotland participants, resulting in summary statistics for MDD derived from a sample of 50,455 cases and 105,411 controls.

Briefly, PRSice removed strand-ambiguous SNPs and clump-based pruned ( r 2 = 0.1, within a 10 Mb window) our target sample to obtain the most significant independent SNPs in approximate linkage equilibrium. Independent risk alleles were then weighted by the allelic effect sizes estimated in the independent discovery sample and aggregated into PRS. PRS were generated for eight p thresholds ( p thresholds: < 5 × 10 −8 , < 1 × 10 −5 , < 0.001, < 0.01, < 0.05, < 0.1, < 0.5, < = 1) determined by the discovery sample and standardized (See Supplementary Table 1 for summary of PRS).

A genetic relationship matrix (GRM) was calculated for each dataset (i.e., full cohort , women , and men ) using GCTA 1.26.0 50 . Mixed linear models using the GRM were used to estimate the variance in depression score explained by PRS, SLEs and their interaction; and stratified by sex. Twenty principal components were calculated for the datasets.

The mixed linear model used to assess the effects of PRS is as follows:

Mixed linear models used to assess the effect of the stressors are as follows:

Following Colodro-Conde et al. 23 , covariates (i.e., age, age 2 , sex, age-by-sex and age 2 -by-sex interactions, and 20 principal components) were regressed from PRS (PRS’) and SLE scores (i.e., TSLE’, DSLE’ and ISLE’; SLEs’) before fitting models in GCTA to guard against confounding influences on the PRS-by-SLEs interactions 51 . PRS’ and SLEs’ were standardized to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. The Mixed linear models (i.e., the diathesis-stress model) used to assess GxE effects are as follows:

\(\begin{array}{lcc}{\mathrm{Depression}} = \beta _0 + \beta _1{\mathrm{PRS}}^\prime + \beta _2{\mathrm{TSLE}}^\prime \\+\, \beta _3{\mathrm{PRS}}^\prime x{\mathrm{TSLE}}^\prime + {\mathrm{GRM}} + {\mathrm{Covariates}}\end{array}\)

Covariates fitted in the models above were age, age 2 , sex, age-by-sex, age 2 -by-sex, and 20 principal components. Sex and its interactions (age-by-sex and age 2 -by-sex) were omitted from the covariates when stratifying by sex. All parameters from the models were estimated using GCTA and the significance of the effect ( β ) from fixed effects assessed using a Wald test. The significance of main effects (PRS and SLEs) allowed for nominally testing the significance of interactions at p -threshold = 0.05. To account for multiple testing correction, a Bonferroni’s adjustment correcting for 8 PRS and 3 measures of SLE tested (24 tests) was used to establish a robust threshold for significance at p = 2.08 × 10 −3 .

The PRS effect on depression score at different levels of exposure was further examined for the detected nominally significant interactions by categorizing participants on three groups based on the number of SLE reported (i.e., “none”, “low” or “high”). Using linear regression, we applied a least squares approach to assess PRS’ effects on the depression score in each SLE category. Further conservative Bonferroni correction to adjust for the 3 SLE categories tested established a threshold for significance of p = 6.94 × 10 −4 .

Differences on the estimated size of GxE effect between women and men were assessed by comparing a z -score to the standard normal distribution (α = 0.05, one-tailed). Z -scores were derived from GxE estimates ( β ) and standard errors (SE) detected in women and men as follows:

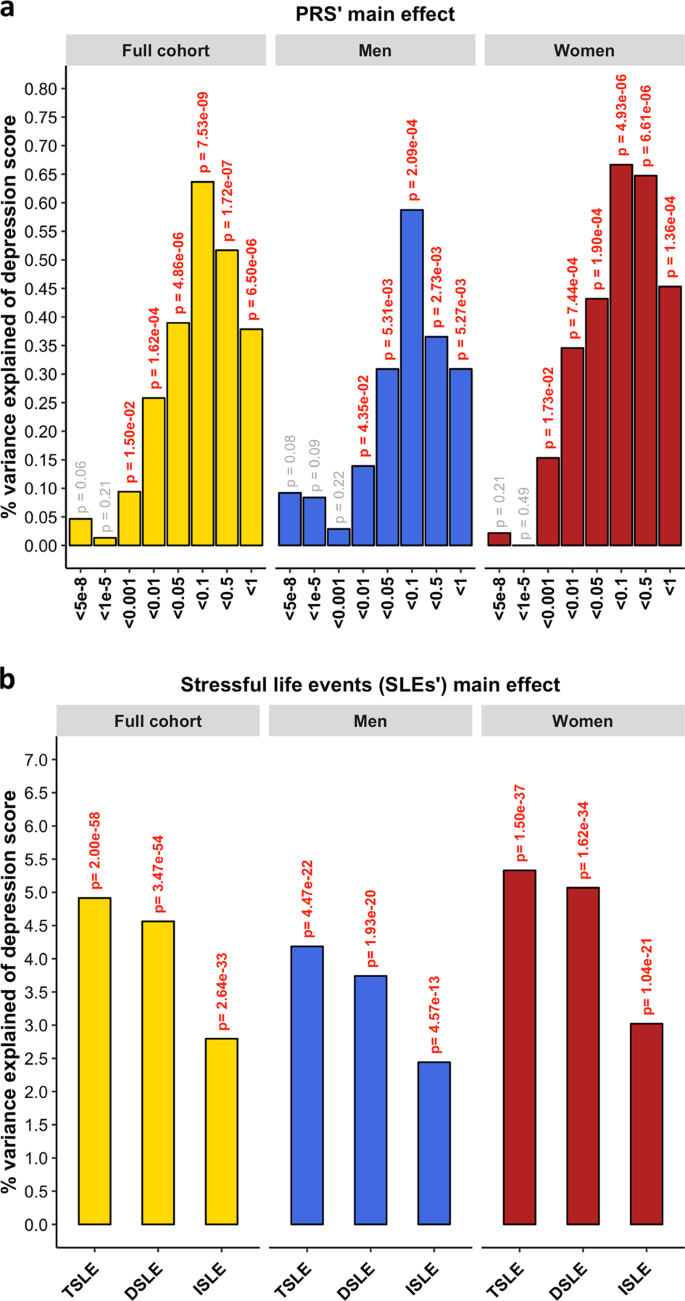

PRS for MDD significantly predicted the depression score across the whole sample ( β = 0.080, s.e. = 0.014, p = 7.53 × 10 −9 ) explaining 0.64% of the variance at its best p- threshold ( p- threshold = 0.1; Fig. 1a ). Stratifying by sex, PRS significantly predicted the depression score in both sexes, explaining 0.59% in men and 0.67% in women ( men : p- threshold = 0.1, β = 0.077, s.e. = 0.022, p = 2.09 × 10 −4 ; women : p- threshold = 0.1, β = 0.082, s.e. = 0.018, p = 4.93 × 10 −6 ; Fig. 1a ). Self-reported SLE over the last 6 months (TSLE, mean = 1.3 SLE, s.d. = 1.5) also significantly predicted depression score for the whole sample and stratified by sex ( full cohort : variance explained = 4.91%, β = 0.222, s.e. = 0.014, p = 9.98 × 10 −59 ; men : 4.19%, β = 0.205, s.e. = 0.021, p = 2.23 × 10 −22 ; women : 5.33%, β = 0.231, s.e. = 0.018, p = 7.48 × 10 −38 ; Fig. 1b ). Overall, significant additive contributions from genetics and SLE to depression score were detected in all participants and across sexes. There was no significant difference in the direct effect of TSLE between women and men ( p = 0.17). However, the variance in depression score explained by the TSLE appeared to be lower than the variance explained by the measure of personal SLE (PSLE) used in Colodro-Conde et al. 23 (12.9%). This may, in part, be explained by different contributions of dependent and independent SLE items screened in Colodro-Conde et al. compared to our study. Although questions about dependent SLE (DSLE, mean = 0.4 SLE) represented over 28% of the TSLE-items reported in our study, the main effect of DSLE explained approximately 93% of the amount of variance explained by TSLE ( full cohort : variance explained = 4.56%, β = 0.212, s.e. = 0.014, p = 1.73 × 10 −54 ; men : 3.74%, β = 0.193, s.e. = 0.021, p = 9.66 × 10 −21 ; women : 5.07%, β = 0.225, s.e. = 0.018, p = 8.09 × 10 −35 ; Fig. 1b ). Independent SLE (ISLE, mean = 0.85 SLE), which represented over 69% of TSLE-items, explained approximately 57% of the amount of variance explained by TSLE ( full cohort : variance explained = 2.80%, β = 0.167, s.e. = 0.014, p = 1.32 × 10 −33 ; men : 2.44%, β = 0.156, s.e. = 0.022, p = 2.88 × 10 −13 ; women : 3.02%, β = 0.174, s.e. = 0.018, p = 5.20 × 10 −22 ; Fig. 1b ). To explore the contribution from each measure, we combined DSLE and ISLE together in a single model. DSLE explained 3.34% of the variance in depression score compared to 1.45% of the variance being explained by ISLE, suggesting that DSLE have a greater effect on liability to depressive symptoms than ISLE.

a Association between polygenic risk scores (PRS) and depression score (main effects, one-sided tests). PRS were generated at 8 p -threshold levels using summary statistics from the Psychiatric Genetic Consortium MDD GWAS (released July 2016) with the exclusion of Generation Scotland participants. The depression score was derived from The General Health Questionnaire. The Y -axis represents the % of variance of depression score explained by PRS main effects. The full cohort (yellow) was split into men (blue) and women (red). In Colodro-Conde et al. PRS for MDD significantly explained up to 0.46% of depression score in their sample (~0.39% in women and ~0.70% in men). b Association between reported number of SLE and depression score (main effect, one-sided tests, results expressed in % of variance in depression score explained). SLE were self-reported through a brief life-events questionnaire based on the List of Threatening Experiences and categorized into: total number of SLE reported (TSLE), “dependent” SLE (DSLE) or “independent” SLE (ISLE). The full cohort (yellow) was split into men (blue) and women (red). In Colodro-Conde et al. “personal” SLE significantly explained up to 12.9% of depression score variance in their sample (~11.5% in women and ~16% in men) 23

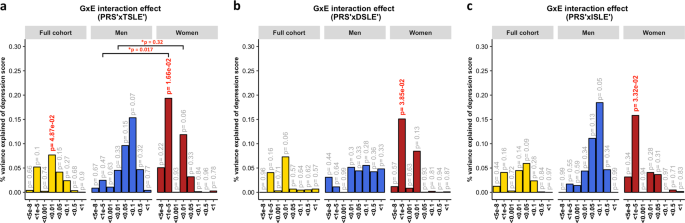

A diathesis-stress model for depression was tested to assess GxE effects. We detected significant, albeit weak, GxE effects on depression score (Fig. 2 ). The PRS interaction with TSLE was nominally significant in the full cohort ( β = 0.028, s.e. = 0.014, R 2 = 0.08%, p = 0.049) and slightly stronger in women ( β = 0.044, s.e. = 0.018, R 2 = 0.19%, p = 0.017; Fig. 2a ), compared to men in which the effect was not significant ( β = 0.039, s.e. = 0.022, R 2 = 0.15%, p = 0.07). However, these results did not survive correction for multiple testing ( p > 2.08 × 10 -3 ).

The plots show the percentage of depression score explained by the interaction term (two-sided tests) fitted in linear mixed models to empirically test the diathesis-stress model. Red numbers show significant interactions p -values. *Shows the significance of the difference in variance explained between sexes. The full cohort (yellow) was split into men (blue) and women (red). PRS were generated at 8 p -threshold levels using summary statistics from the Psychiatric Genetic Consortium MDD GWAS (released July 2016) with the exclusion of Generation Scotland participants. The interaction effect was tested with the number of: ( a ) SLE (TSLE), ( b ) “dependent” SLE (DSLE) and c ) “independent” SLE (ISLE). In Colodro-Conde et al., the variance of depression score explained in their sample by GxE was 0.12% ( p = 7 × 10 −3 ). GxE were also significant in women ( p = 2 × 10 -3 ) explaining up to 0.25% of depression score variation, but not in men ( p = 0.059; R 2 = 0.17%; negative/protective effect on depression score)

The best-fit threshold was much lower in women ( p- threshold = 1 × 10 −5 ) compared to the full sample ( p -threshold = 0.01). The size of the GxE effects across sexes at p- threshold = 1 × 10 −5 were significantly different (GxE*sex p = 0.017), but not at the best p-threshold in the full cohort ( p -threshold = 0.01, GxE*sex p = 0.32; Fig. 2a ). In women, GxE effect with DSLE predicted depression score ( p- threshold = 1 × 10 −5 ; β = 0.039, s.e. = 0.019, R 2 = 0.15%, p = 0.038; Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a ), as did the GxE effect with ISLE ( p- threshold = 1 × 10 −5 ; β = 0.040, s.e. = 0.019, R 2 = 0.16%, p = 0.033; Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2b ). No significant interaction was detected in men (best-fit p- threshold = 0.1) with either TSLE ( β = 0.039, s.e. = 0.022, R 2 = 0.15%, p = 0.072; Fig. 2a ), DSLE ( β = 0.024, s.e. = 0.022, R 2 = 0.06%, p = 0.28; Fig. 2b ) or ISLE ( β = 0.043, s.e. = 0.022, R 2 = 0.18%, p = 0.055; Fig. 2c ).

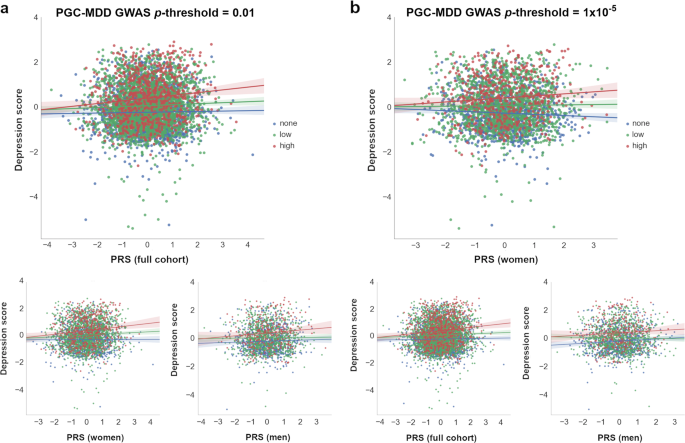

To examine these results further and investigate the diathesis effect at different levels of stress, nominally significant GxE were plotted between PRS and categories of SLE (i.e, “none”, “low”, and “high” SLE reported; Fig. 3 ). Examining the interaction found in the full cohort (PRS at PGC-MDD GWAS p- threshold = 0.01), we detected a significant direct diathesis effect on the risk of depressive symptoms in those participants reporting SLE, with a higher risk when greater numbers of SLE were reported (“low” number of SLE reported: PRS’ β = 0.043, s.e. = 0.021, p = 0.039; “high” number of SLE reported: PRS’ β = 0.142, s.e. = 0.039, p = 2.86 × 10 −4 ; see Table 1 and Fig. 3a ). Whereas, in participants who reported no SLE over the preceding 6 months, the risk of depressive symptoms was the same regardless of their diathesis risk (“none” SLE reported: PRS’ β = 0.021, s.e. = 0.022, p = 0.339). Stratifying these results by sex, we found the same pattern as in the full cohort in women (“none”: p = 0.687; “low”: p = 0.023; “high”: p = 2 × 10 -3 ), but not in men (“none”: p = 0.307; “low”: p = 728; “high”: p = 0.053; see Table 1 and Fig. 3a ). However, the lack of a significant diathesis effect in men may be due to their lower sample size and its corresponding reduced power.

Interactions with PRS at which nominally significant GxE effects were detected in ( a ) full cohort ( p- threshold = 0.01) and ( b ) in women ( p- threshold = 1 × 10 –5 ) are shown. At bottom, the remaining samples (i.e., full cohort , women or men ) at same p- threshold are shown for comparison. The X-axis represents the direct effect of PRS (standard deviation from the mean) based on ( a ) p -threshold = 0.01 and ( b ) p -threshold = 1 × 10 –5 , using the total number of SLE reported by each participant (dot) as environmental exposures at three SLE levels represented by colors. Blue: 0 SLE, “no stress”, n = 1 833/1 041/792; green: 1 or 2 SLE, “low stress”, n = 2 311/1 459/852; red: 3 or more SLE, “high stress”, n = 775/490/285; in the full cohort, women and men, respectively. Y -axis reflects the depression score standardized to mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Lines represent the increment in risk of depression at a certain degree of “stress” dependent on a genetic predisposition ( = diathesis )

Examining the interaction with PRS at PGC-MDD GWAS p- threshold = 1 × 10 −5 , with which a significant interaction was detected in women, we detected a significant diathesis effect on depression score only when stratifying by sex in those participants who did not reported SLE over the last 6 months (see Table 1 ). The diathesis effect was positive in men (PRS’ β = 0.082, s.e. = 0.034, p = 0.016, R 2 = 0.7%; Fig. 3b ), consistent with the contribution of risk alleles. Conversely, the diathesis effect was negative in women (PRS’ β = -0.061, s.e. = 0.029, p = 0.037, R 2 = 0.4%; Fig. 3b ), suggesting a protective effect of increasing PRS in those women reporting no SLE, and consistent with the contribution of alleles to individual sensitivity to both positive and negative environmental effects (i.e., “plasticity alleles” rather than “risk alleles”) 52 , 53 . This PRS accounted for the effect of just 34 SNPs, and the size of its GxE across sexes were significantly different (GxE*sex p = 0.017; Fig. 2a ), supporting possible differences in the underlying stress-response mechanisms between women and men.

The findings reported in this study support those from Colodro-Conde et al. 23 , in an independent sample of similar sample size and study design, and also supports possible sex-specific differences in the effect of genetic risk of MDD in response to SLE.

Both Colodro-Conde et al. and our study suggest that individuals with an inherent genetic predisposition to MDD, reporting high number of recent SLE, are at additional risk of depressive symptoms due to GxE effects, thus validating the diathesis-stress theory. We identified nominally significant GxE effects in liability to depression at the population level ( p = 0.049) and in women ( p = 0.017), but not in men ( p = 0.072). However, these interactions did not survive multiple testing correction ( p > 2.08 × 10 −3 ) and the power of both studies to draw robust conclusions remains limited 54 . With increased power these studies could determine more accurately both the presence and magnitude of a GxE effect in depression. To better understand the effect of PRS at different levels of exposure to stress, we examined the nominally significant interactions detected in the full sample by categorizing participants on three groups based on the number of SLE reported (i.e., “none”, “low” or “high”). We detected a significant diathesis effect on risk of depression only in those participants reporting SLE, but not in those participants that reported no SLE over the preceding 6 months. Furthermore, the diathesis effect was stronger on those participants reporting a “high” number of SLE ( β = 0.142, p = 2.86 × 10 −4 ) compared to those participants reporting a “low” number of SLE ( β = 0.043, p = 0.039). The former effect was significant and survived a conservative Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple testing ( p < 6.94 × 10 −4 ). This finding corroborates the diathesis-stress model for depression and supports the results of Colodro-Conde et al. in an independent sample.

To investigate the relative contribution of the GxE to the variance of depression, we examined in the full cohort the total variance of depression score explained by the PRS main effect and the significant GxE effect jointly. Together, they explained 0.34% of the variance, of which 0.07% of the variance of the depression score was attributed to the GxE effect ( p- threshold = 0.01; PRS p = 1.19 × 10 −4 , GxE p = 0.049; both derived from the full diathesis-model with TSLE). This is lower than the proportion of variance attributed to common SNPs (8.9%) in the full PGC-MDD analysis 16 . As Colodro-Conde et al . noted, this result aligns with estimates from experimental organisms suggesting that around 20% of the heritability may be typically attributed to the effects of GxE 55 , although it is inconsistent with twin studies of the majority of human traits with the potential exception of depression 56 .

Consistent with PRS predicting “personal” SLE in Colodro-Conde et al., PRS for MDD predicted SLE in our study (see Supplementary Fig. 1 ), although not at the p- threshold at which significant GxE effects were detected. Genetic factors predisposing to MDD may contribute to individuals exposing themselves to, or showing an increased reporting of, SLE via behavioral or personality traits 57 , 58 . Such genetic mediation of the association between depression and SLE would disclose a gene-environment correlation (i.e., genetic effects on the probability of undergoing a SLE) that hinders interpretion of our findings as pure GxE effects 59 , 60 . To address this limitation and assess this aspect, following Colodro-Conde et al., we split the 12-items TSLE measure into SLE that are either potentially “dependent” of a participant’s own behavior (DSLE; therefore, potentially driven by genetic factors) or not (“independent” SLE; ISLE) 45 , 48 . DSLE are reported to be more heritable and have stronger associations with MDD than ISLE 48 , 61 57 . In our sample, DSLE is significantly heritable ( h 2 SNP = 0.131, s.e. = 0.071, p = 0.029), supporting a genetic mediation of the association, whereas ISLE is not significantly heritable ( h 2 SNP = 0.000, s.e. = 0.072, p = 0.5) 62 . Nominally significant GxE effects were seen in women for both DSLE and ISLE, suggesting that both GxE and gene-environment correlation co-occur. Colodro-Conde et al. did not identify significant GxE using independent SLE as the exposure.

Between-sex differences in stress response could help to explain previous differences seen between sexes in depression such as those in associated risk (i.e., approximately 1.5–2-fold higher in women), symptoms reported and/or coping strategies (e.g., whereas women tend to cope through verbal and emotional strategies, men tend to cope by doing sport and consuming alcohol) 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 . This also aligns with an increased risk associated with a lack of social support seen in women compared to men 23 . Furthermore, although we do not know whether participants experienced recent events with positive effects, we saw a protective effect in those women who did not experienced recent SLE ( p = 0.037), suggesting that some genetic variants associated with MDD may operate as “plasticity alleles” and not just as “risk alleles” 52 , 53 . This effect was neutralized in the full cohort due to an opposite effect in men ( p = 0.016), but it is supported by previous protective effects reported when using a serotoninergic multilocus profile score and absence of SLE in young women 68 . These findings would be consistent with a differential-susceptibility model of depression 69 , 70 , also suggested by the interaction effects seen between the serotonin transporter linked promoter region gene (5-HTTLPR) locus and family support and liability to adolescent depression in boys 71 . However, our results and the examples given are only nominally significant and will require replication in larger samples. Robust identification of sex-specific differences in genetic stress-response could improve personalized treatments and therapies such as better coping strategies.

There are notable differences between our study and Colodro-Conde et al. to consider before accepting our findings as a replication of their results. First, differences in PRS profiling may have affected replication power. We used the same equivalent PGC-MDD2 GWAS as discovery sample. However, whereas Colodro-Conde et al. generated PRS in their target sample containing over 9.5 M imputed SNP, in this study we generated PRS in a target sample of over 560 K genotyped SNPs (see Supplementary table 1 for comparison). This potentially results in a less informative PRS in our study, with less predictive power, although the variance explained by our PRS was slightly larger (0.64% vs. 0.46%). The size of the discovery sample is key to constructing an accurate predictive PRS, but to exploit the greatest number of the available variants may be an asset 54 . Secondly, different screening tools were used to measure both current depressive symptoms and recent environmental stressors across the two studies. Both studies transformed their data, using item response theory or by log-transformation, to improve the data distribution. However, neither study used depression scores that were normally distributed. The scale of the instruments used and their corresponding parameterization when testing for an interaction could have a direct effect on the size and significance of their interaction; 55 , 72 so findings from GxE must be taken with caution. Furthermore, although both screening methods have been validated and applied to detect depressive symptoms, different questions may cover and emphasize different features of the illness, which may result in different results. The same applies to the measurement of environmental stressors in the two studies. Both covering of a longer time-period and upweighting by “dependent” SLE items may explain the increased explanatory power of “personal” SLE (12.9%) in Colodro-Conde et al. to predict depression score compared to our “total” SLE measure (4.91%). Finally, the unmeasured aspects of the exposure to SLE or its impact may also contribute to the lack of a stronger replication and positive findings.

In conclusion, despite differences in the measures used across studies, we saw concordance and similar patterns between our results and those of Colodro-Conde et al. 23 Our findings, therefore, add validity to the diathesis-stress theory for depression. Empirically demonstrating the diathesis-stress theory for depression would validate recent 20 , 21 , 22 and future studies using a genome-wide approach to identify genetic mechanisms and interactive pathways involved in GxE underpinning the causative effect of “stress” in the development of depressive symptoms and in mental illness in general. This study adds to our understanding of gene-by-environment interactions, although larger samples will be required to confirm differences in diathesis-stress effects between women and men.

Hammen, C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev. Clin. Psychol. 1 , 293–319 (2005).

Article Google Scholar

Kessler, R. C. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev. Psychol. 48 , 191–214 (1997).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kendler, K. S., Karkowski, L. M. & Prescott, C. A. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 156 , 837–841 (1999).

Paykel, E. S. Life events and affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 108 , 61–66 (2003).

Stroud, C. B., Davila, J. & Moyer, A. The relationship between stress and depression in first onsets versus recurrences: a meta-analytic review. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 117 , 206–213 (2008).

Ensel, W. M., Peek, M. K., Lin, N. & Lai, G. Stress in the life course: a life history approach. J. Aging Health 8 , 389–416 (1996).

Kendler, K. S., Karkowski, L. M. & Prescott, C. A. Stressful life events and major depression: risk period, long-term contextual threat, and diagnostic specificity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 186 , 661–669 (1998).

Mazure, C. M. Life stressors as risk factors in depression. Clin. Psychol. 5 , 291–313 (1998).

Google Scholar

Lichtenberg, P. & Belmaker, R. H. Subtyping major depressive disorder. Psychother. Psychosom. 79 , 131–135 (2010).

Elisei, S., Sciarma, T., Verdolini, N. & Anastasi, S. Resilience and depressive disorders. Psychiatr. Danub. 25 (Suppl 2), S263–S267 (2013).

PubMed Google Scholar

Monroe, S. M. & Simons, A. D. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychol. Bull. 110 , 406–425 (1991).

Vogel, F. Schizophrenia genesis: the origins of madness. Am. J. Human. Genet. 48 , 1218–1218 (1991).

Mann, J. J., Waternaux, C., Haas, G. L. & Malone, K. M. Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 156 , 181–189 (1999).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Riemann, D. et al. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep. Med Rev. 14 , 19–31 (2010).

Bolt, M. A., Helming, L. M. & Tintle, N. L. The associations between self-reported exposure to the chernobyl nuclear disaster zone and mental health disorders in Ukraine. Front. Psychiatry 9 , 32 (2018).

Wray, N. R. & Sullivan, P. F. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nature Genetics 50 , 668–681 (2018).

Peyrot, W. J. et al. Effect of polygenic risk scores on depression in childhood trauma. Br. J. Psychiatry 205 , 113–119 (2014).

Musliner, K. L. et al. Polygenic risk, stressful life events and depressive symptoms in older adults: a polygenic score analysis. Psychol. Med. 45 , 1709–1720 (2015).

Peyrot, W. J. et al. Does childhood trauma moderate polygenic risk for depression? A Meta-analysis of 5765 Subjects From the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biol. Psychiatry 84 , 138–147 (2018).

Dunn, E. C. et al. Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) and Genome-Wide by Environment Interaction Study (GWEIS) of Depressive Symptoms in African American and Hispanic/Latina Women. Depress. Anxiety 33 , 265–280 (2016).

Otowa, T. et al. The first pilot genome-wide gene-environment study of depression in the Japanese Population. PLoS One 11 , e0160823 (2016).

Ikeda, M. et al. Genome-wide environment interaction between depressive state and stressful life events. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77 , e29–e30 (2016).

Colodro-Conde, L. et al. A direct test of the diathesis-stress model for depression. Mol. Psychiatry 23 , 1590–1596 (2018).