- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How Disruption Accelerated Digital Supply Chain Transformation

Sponsor content from GEP.

In 2020, when the pandemic erupted, Tesco—a leading British retailer of groceries and general merchandise—was staring at challenges it had never seen.

Having been designated an “essential” retailer, Tesco saw a huge rush to its stores while other outlets were temporarily closed. And as customers chose to buy from the safety of their homes, demand for online shopping grew at an unprecedented rate.

Tesco responded by more than doubling its capacity for online orders, to more than 1.5 million a week. To support this increase, it opened an urban fulfillment center—a small automated warehouse—within each store. The retailer plans to add several more fulfillment centers in the next 12 months to boost its online delivery capabilities.

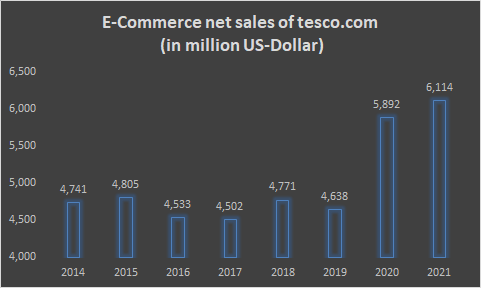

Tesco’s online sales have increased by 77% since the pandemic began. The retailer could have easily missed this growth opportunity and taken a big hit on revenue, but it rose to the challenge by testing several approaches to modernizing its omnichannel retail operation and enhancing its digital sales capabilities.

Tesco, of course, isn’t the only enterprise that responded to the pandemic by pivoting to combat supply-chain disruption. Many enterprises accelerated the digitalization of their customer and supply-chain interactions by as much as three to four years.

It wasn’t only about turning retail space into warehouses to accommodate a broken supply chain. As traditional retail channels weakened, iconic brands, including Nike, added or expanded their online direct-to-consumer sales. Nike’s digital sales grew 79% after its brick-and-mortar stores shuttered in 2020.

A B2B Push from Inside Out

The e-commerce rush wasn’t limited to retailers. Many business-to-business (B2B) sales and interactions pivoted to e-commerce as well.

The pandemic catalyzed digital transformation at many global enterprises. Over 69% of leaders said social and economic disruption were accelerating their digital business initiatives, a 2020 board of directors survey by Gartner revealed. Many said their business changed more in the first few months of the outbreak than it had in the previous decade.

The push for digital has come from the inside out. Technology has helped internal teams rally to support customers and partners during the lockdown, free of the inertia and change-management issues often associated with such programs.

Even with an accelerated pace of digital transformation, enterprises have a long way to go. A recent Harvard Business Review Analytic Services and GEP study showed that more than 72% of companies believed their key supply chain capabilities—supply planning, demand planning , supplier risk management, warehousing and logistics, procurement, and inventory management—to be digitally immature.

The Time for Digital Transformation Is Now

New technologies can provide comprehensive supply-chain visibility with real-time data and intelligence to help companies make timely and effective decisions based on shifting market dynamics.

Artificial intelligence (AI), internet of things (IoT), predictive analytics, and other transformative technologies can help enterprises respond to sudden shifts in demand and supply trends, and plan for such shifts in advance.

Enterprises must prioritize their digital supply-chain investments in three key areas: visibility, planning, and collaboration. They must look at upgrading or replacing their legacy enterprise resource planning (ERP) and supply-chain systems with next-generation cloud-based supply-chain platforms designed to support rapid innovation. Effective supply-chain collaboration , both within and outside the enterprise, is critical for increased agility and resilience. Over 66% of companies in the Harvard Business Review Analytic Services and GEP study said they will be focusing on improving collaboration.

While investing in the right technology is critical for supply-chain transformation, enterprises must also focus on helping their workforce become more digital-savvy. More than 50% of companies plan to invest in training to improve their employees’ skills in using digital tools. The key, however, is to look for technology solutions that have intuitive design and interfaces and don’t have a steep learning curve.

Disruptions like the pandemic are no longer rare and unpredictable “black swan” events. The high threat of natural disasters, political unrest, economic crises, and pandemics will continue, so enterprises must build the capabilities they need to mitigate such disruptions.

Enterprises that had developed strong digital capabilities in advance of the pandemic were better able to cope with the disruption with agility and resilience than those that hadn’t.

Now is the time for enterprises to assess their digital readiness and start investing—or accelerating their investments—in digital supply-chain transformation . A supply-chain digital-maturity assessment can help your organization identify gaps and improvement areas.

To learn how GEP’s comprehensive portfolio of software, strategy, and managed services can help your enterprise build an agile, intelligent, and resilient supply chain, visit gep.com .

Technology and Operations Management

Mba student perspectives.

- Assignments

- Assignment: Digitization Challenge

Tesco: A digital transformation

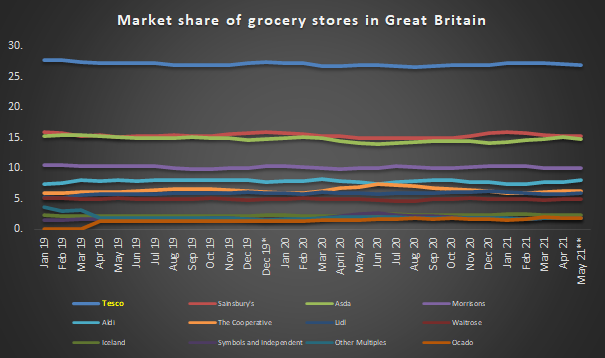

Tesco is the leading grocer in the UK, accounting for 25% of all grocery sales offline and 43% of all grocery sales online [1]. In the last 15 years, Tesco has digitally transformed their customer experience, business model and operating model through investments in a state-of-the-art website with click-and-collect functionality, a digitalized in-store experience and a data-driven customer loyalty platform.

How is Tesco using technology to differentiate their Business and Operating Model?

Tesco has continually been investing in technology to develop an omnichannel customer experience and to maintain a competitive edge in an increasingly digitized UK grocery landscape. Three technological advancements that have created opportunities, as well as some challenges, for Tesco have been:

- Moving from ‘bricks and mortar’ to ‘bricks and clicks’ with the emergence of Tesco Direct, an online grocery platform with ‘click-and-collect’ functionality

In the early 2000s, the UK was prime for online grocery shopping and home delivery due to high technology adoption rates and areas of high population density. In 2000, Tesco was quick to respond to this opportunity, adapting their business model by establishing an online grocery channel, ‘Tesco Direct’ (Exhibit 1) [2]. By 2006, online sales were rapidly growing (CAGR of 23%) and in order to meet fulfilment demands, Tesco augmented their operating model by investing in ‘grocery dotcom centres’ [3], warehouses solely for online order fulfilment purposes equipped with innovative ‘goods to person’ picking technology (Exhibit 2) [4]. In 2011, to offer further convenience to customers and to improve business model profitability through lowering home delivery costs, Tesco led the competitive pack by offering an omnichannel ‘click and collect’ function, whereby customers placed orders online and collected bagged groceries at a collection point of their choice. Despite revenue upside, the shift to a ‘bricks and clicks’ omnichannel offering came with challenges for Tesco’s operating model: heavy investment in development of an online platform, investment in ‘grocery dotcom centres’ (approximately £1.5-3.5M per warehouse) [5], investment in a home delivery labour force and supply chain ordering difficulties due to inaccurate forecasting of online grocery orders given a lack of historical data.

Exhibit 1: Tesco Direct online website [2]

Pathways to Just Digital Future

Exhibit 2: State of the art goods-to-person picking technology [6]

- Implementation of a digitalized in-store experience

To improve the efficiency of Tesco’s operating model, Tesco invested in digital in-store initiatives. ‘Scan as you shop’ handheld devices (Exhibit 3) and self-check-out stations (Exhibit 4) were placed adjacent to the usual employee manned check-out stations to provide customers with the technology to perform the check-out function without involvement from Tesco employees [7]. From a business and operating model perspective, this results in efficiency cost savings as fewer employees are required to perform manual check-out [7]. However, self-checkout has not come without challenges – the lack of employee supervision has led to significant levels of fraud for Tesco (approximately ~£8M per year) [8]. Tesco is combating this thievery through digital receipt technology and specialized cameras at self-checkout stations to alert staff real-time to ‘irregular’ customer scanning activity [8].

Exhibit 3: Scan as you shop handheld device [9]

Exhibit 4: Self Service Checkout [10]

In addition, in-store video cameras, such as the ‘broccoli cam’ (Exhibit 5), detect when fruit and vegetable trays in the fresh foods aisles are depleted, sending instant messages to the shop-floor employees for immediate replenishment [7]. Electronic shelf-edge labels (Exhibit 6) circumvent the need for Tesco employees to change 5-10 million paper labels monthly, freeing up valuable employee time to focus on serving customers [7, 11]. Moreover, electronic shelf-edge labels allow for instantaneous price-changes throughout a given day, allowing Tesco to implement promotional prices at a moment’s notice. Finally, employees are equipped with portable smart badges which, upon scanning an item, provide employees with information on stock levels and further product details, allowing shop floor employees to answer customer queries live [7].

Exhibit 6: Electronic shelf edge labels [7]

- Development of Tesco Clubcard – a sophisticated data-driven customer loyalty scheme

The Tesco Clubcard loyalty scheme tags a unique customer ID to every purchase, resulting in the amalgamation of millions of customer purchasing data points [13]. Tesco leverages big data analytics and algorithms to adapt the supply chain and product offering to purchasing trends, predict future customer purchasing habits and generate personalized online and offline discounts [14]. This has created opportunities for Tesco’s business and operating model as approximately 16.5 million customers subscribe to Clubcard in the UK, driving greater customer lifetime value and loyalty through repeat purchases due to personalized discounts and allowing greater accuracy into forecasting customer demand by region and product category [5]. What additional steps Tesco should consider implementing?

Moving forward, Tesco needs to leverage smartphone technology to digitally innovate the in-store customer experience by equipping customers with knowledge and personalization in-store. For example, the existing Tesco App could be expanded provide a functionality to help customers locate specific items within superstores and to replace the ‘scan as you shop’ handheld devices for a seamless digital experience using digital wallets. This could create an operating model opportunity by further decreasing in-store headcount and costs. Finally, Tesco could overcome the difficulties users face scanning barcodes in self-checkout machines by utilizing innovative Toshiba technology which no longer requires barcodes [15].

[766 words excluding exhibits]

References:

[1] Planet Retail, www1.planetretail.net/, accessed November 2016

[2] Tesco Direct website, http://www.tesco.com/groceries/ , accessed November 2016

[3] ‘Tesco goes into the darkness’, Retail Gazette, http://www.retailgazette.co.uk/blog/2014/01/42030-tesco-goes-into-the-darkness , accessed November 2016 [4] ‘Insight supermarkets dark stores’, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/business/shortcuts/2014/jan/07/inside-supermarkets-dark-stores-online-shopping , accessed November 2016 [5] Tesco annual report, https://www.tescoplc.com/media/264194/annual-report-2016.pdf , accessed November 2016

[6] Tesco ‘goods to person’ picking image, http://www.expo21xx.com/material_handling/13440_st3_conveyor_elevator/default.htm , accessed November 2016~ [7] In-store innovation at Tesco, Tesco PLC presentation by CIO Mike McNamara, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=noa4SmYhjTA , accessed November 2016 [8] ‘Tesco trials digital receipts and self scanner tech that aims to reduce theft; Marketing Week, https://www.marketingweek.com/2016/10/21/tesco-trials-digital-receipts-and-self-scanner-tech-that-aims-to-reduce-theft/ , accessed November 2016 [9] Tesco scan as you shop image, http://www.tesco.com/scan-as-you-shop/i/diagram.png , accessed November 2016

[10] Tesco self-check out image, https://www.engadget.com/2015/07/30/tesco-automated-checkout-voice/ , accessed November 2016

[11] ‘Tesco is back’, Forbes, http://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinomarah/2016/04/14/tesco-is-back/#5839eaca1c64 , accessed November 2016

[13] ‘Clubcard built the Tesco of today but it could be time to ditch it’, The Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/retailandconsumer/10577685/Clubcard-built-the-Tesco-of-today-but-it-could-be-time-to-ditch-it.html , accessed November 2016 [14] ‘Tesco: how one supermarket came to dominate’, BBC News, http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-23988795 , accessed November 2016 [15] ‘New Toshiba supermarket scanner does away with need for bar codes’, Digital Trends, http://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/new-toshiba-supermarket-scanner-does-away-with-need-for-bar-codes/ , accessed November 2016

Student comments on Tesco: A digital transformation

I completely agree with the idea of Tesco using technology to enhance the customer’s experience in the store. I also think that Tesco’s biggest advantage is the vast trove of data it is now collecting on shoppers through its mobile app and loyalty program. There are benefits to both the brand and consumer of Tesco having this data.

On the consumer side, Tesco can use this to enhance the customer experience, as you mentioned above. For example, since Tesco knows what a shopper has purchased, and how frequently, on average, either that shopper or similar shoppers replace a specific item, Tesco could use this to remind shoppers to buy something that they may be running low on. They can also use this to delight shoppers by suggest recipes using things they’ve purchased or offering savings on things they might want to try. They will need to handle this carefully as to not venture into “creepy” territory.

On the brand side, Tesco can unite the data from the POS and mobile device to understand which products a shopper was considering, but did not ultimately purchase. This information is extremely valuable to brands and can help them target shoppers in a way that maximizes their spend.

Thanks for a great post! It’s interesting to see how advanced Tesco is compared to US grocery retailers, especially with its online delivery platform. I think the biggest advantage for Tesco here is the data they have been able to collect with its loyalty program. I agree with Katherine that the next step is creating personalized communication at the customer level to enhance the customer experience and increase traffic in stores. My concern here is Tesco’s ability to retain strong margins. Grocery retailers already face low margins, and I’m curious to know how these investments have impacted its performance.

Wow – this is so interesting. I had no idea that Tesco was doing so much…I especially love the Broccoli cam!

One concern I have is how whether consumers actually value all these additional digital applications. A Harvard Business Review article from 2014 (“Tesco’s Downfall is a Warning to Data-Driven Retailers” [1]) discussed Tesco’s declining performance despite all the investments they had recently made in digital technology and data analysis. They quoted a Telegraph article which said “…judging by correspondence from Telegraph readers and disillusioned shoppers, one of the reasons that consumers are turning to [discounters] Aldi and Lidl is that they feel they are simple and free of gimmicks. Shoppers are questioning whether loyalty cards, such as Clubcard, are more helpful to the supermarket than they are to the shopper.”

As a consumer I would agree…although the products discussed above sound interesting…how much do value do they really provide for myself as a shopper?

[1] https://hbr.org/2014/10/tescos-downfall-is-a-warning-to-data-driven-retailers

Great read CC! It’s amazing to know that a 100-year-old retailer such as Tesco has been investing capital and innovating to stay competitive in the digital age. I loved the simple yet far-reaching functionalities of the innovations you mentioned, especially ‘the broccoli cam’ and the electronic shelf labels.

It is well known that Clubcard was pivotal in establishing Tesco as a dominant player in UK [1] but it might be time to update the way it works. With the advent of smartphones, most consumers have their loyalty programs on their phones, with easy real time access to their benefits and rewards. Customers are also happier

Tesco also has a huge potential in updating its supply chain through digital initiatives. More and more firms are relying on technologies such as Sensors & geolocation, robotics, big data and cloud services to gain supply chain efficiencies and cost savings. [2] Things are clearly working in Tesco’s favor as they enjoy fastest growth in three years as Aldi and Lidl slow [3]. Hope they realize the huge potential that digitization has to offer and keep evolving

[1] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/retailandconsumer/10577685/Clubcard-built-the-Tesco-of-today-but-it-could-be-time-to-ditch-it.html

[2] https://www.atkearney.com/documents/10192/6500433/Digital+Supply+Chains.pdf/a12fffe7-a022-4ab3-a37c-b4fb986088f0

[3] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/11/15/tesco-enjoys-fastest-growth-in-three-years-as-aldi-and-lidl-slow/

Leave a comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Logistics in Tesco: Past, Present and Future

Table of contents:

Logistics in Tesco Past, Present and Future

Introduction, tesco in the past establishing control over distribution, direct to store delivery, centralization, composite distribution, vertical collaboration, the present tesco supply chain today, the changing business, the current network, current initiatives, the future evolution or revolution.

David Smith and Leigh Sparks

The business transformation of Tesco in the last 25 or so years is one of the more remarkable stories in British retailing. From being essentially a comparatively small ‘pile it high, sell it cheap’ downmarket retailer, the company has become one of Europe’s leading retail businesses, with retail operations in countries as far-flung as Ireland, Poland, Malaysia and Japan. In the United Kingdom its loyalty card and its e-commerce operations are generally considered to be world-leading, and its expertise in these fields is much in demand (Humby, Hunt and Phillips, 2003).

Accounts of this transformation by those involved are widely available (Corina, 1971; Powell, 1991; MacLaurin, 1999). Tesco is the focus of much academic, analyst and commentator consideration (for instance Seth and Randall, 1999; Burt and Sparks, 2002, IGD, 2003a). Some aspects of the Tesco operations have been discussed in public by their executives (such as Kelly, 2000; Mason, 1998; Jones, 2001; Jones and Clarke, 2002; Child, 2002). This literature points to the fundamental transformation of the retail business to meet changing consumer demands and global opportunities. Tesco has become dominant in its home market (Burt and Sparks, 2003) and closely watched on the international stage.

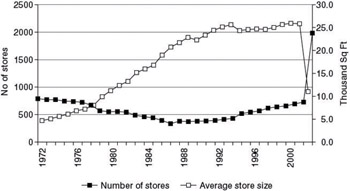

The visible component of this transformation is in the location and format of the retail outlets and in the range of products and services that the company offers in-store and online. Customers are also aware of the change through the constant reinforcement of the corporate brand. Less visible however is the logistics transformation that has underpinned this retail success story. It should be obvious that the supply chain required to deliver to lots of small high-street stores in the 1970s, selling comparatively simple products, was vastly different to the current supply chain in delivery of the breadth of products in a modern Tesco Extra hypermarket, or in the availability required to run Tesco Express convenience stores, or the warehouse worlds and weekly shopping on Tesco.com. This logistics and supply chain transformation has received far less public consideration, although some academic analysis is available (Sparks, 1986; Smith and Sparks, 1993; Smith, 1998; Jones and Clarke, 2002).

This chapter presents a summary of this logistics and supply chain transformation in Tesco. It draws heavily on this public literature, although a series of interviews with managers and directors at different levels in the company has also informed the work. The paper aims to describe, analyse and draw lessons from the logistics journey Tesco has undertaken.

The current retail position of Tesco is far removed from the origins of the company. Tesco made its name by the operation of a ‘pile it high, sell it cheap’ approach to food retailing. Price competitiveness was critical to this and fitted well with the consumer requirements of the time. The company and its store managers were essentially individual entrepreneurs. The growth of the company saw considerable expansion until by the mid-1970s Tesco had 800 stores across England and Wales. This entrepreneurial approach to retailing, epitomized by Sir Jack Cohen, was put under pressure however as competition and consumer requirements changed. Tesco itself had therefore to change.

The emblematic event signifying the beginning of this transformation was Operation Checkout in 1977 (Akehurst, 1984). Dramatically, trading stamps were removed from the business, prices were cut nationally as a grand event and the business received an immediate considerable boost to volume. Stores were re-merchandized as part of Operation Checkout, and consumers began to see a different approach to Tesco retailing. After this initial repositioning event and phase, Tesco began to better under- stand its customers, control its business, and move away from its solely down-market image (Powell, 1991). This retail transformation brought into sharp focus the quality and capability of Tesco supply systems and the relationships with suppliers.

Such concerns have remained critical during the almost irresistible rise of Tesco in the 1980s and 1990s. By moving away from its origins, Tesco changed its business. Initially the focus was on conforming out-of-town superstores, but since the early 1990s a multi-format approach has developed, encompassing hypermarkets, superstores, supermarkets, city centre stores and convenience operations. The Tesco corporate brand has been strongly developed (Burt and Sparks, 2002) and international ambitions have emerged. In all this, the distribution and supply of appropriate products to the stores has been fundamental.

There have been four main phases in the reconfiguration of the distribution strategy and operations. First, there was a period primarily of direct delivery by the supplier to the retail store. Second, there was the move, starting in the late 1970s, to centralized regional distribution centres for ambient goods and the refinement of that process of centralized distribution. Third, a composite distribution strategy developed, starting in 1989. Fourth, the 1990s witnessed the advent of vertical collaboration in the supply chain to achieve better operating efficiency.

Tesco in the mid-1970s operated a direct to store delivery (DSD) process. Suppliers and manufacturers delivered directly to stores, almost as and when they chose. Store managers often operated their own relationships (Powell’s ‘private enterprise’, 1991: 185) which made central control and standardization difficult to achieve. Product volumes and quality were inconsistent. This DSD system fell apart under the pressures of the volume increases of Operation Checkout.

As Powell comments, quoting Sir Ian MacLaurin:

Ultimately our business is about getting our goods to our stores in sufficient quantities to meet our customers’ demands. Without being able to do that efficiently, we aren’t in business, and Checkout stretched our resources to the limit. Eighty per cent of all our supplies were coming direct from manufacturers, and unless we’d sorted out our distribution problems there was a very real danger that we would have become a laughing stock for promoting cuts on lines that we couldn’t even deliver. It was a close-run thing. (Powell, 1991: 184)

Powell continues:

How close is now a matter of legend: outside suppliers having to wait for up to twenty-four hours to deliver at Tesco’s centres; of stock checks being conducted in the open air; of Tesco’s four obsolescent warehouses, and the company’s transport fleet working to around-the-clock, seven-day schedule. And as the problems lived off one another, and as customers waited for the emptied shelves to be refilled, so the tailback lengthened around the stores, delays of five to six hours becoming commonplace. Possibly for the first time in its history, the company recognized that it was as much in the business of distribution as of retailing. (Powell, 1991: 184, emphasis added)

The company began to gain control of the problems through operational ‘fire fighting’, and while problems occurred, melt-down was avoided. It was clear however that changes to distribution would be needed as the new business strategy took hold.

The decision was taken to move away from direct delivery to stores and to implement centralization. The basis of this decision (in 1980) was the realization of the critical nature of range control on the operations. Store managers could no longer be allowed to decide ranges and prices and to operate mini-fiefdoms. If the company was to be transformed as the business strategy proposed, then head office needed control over ranging, pricing and stocking decisions. Concerns over quality of product also suggested a need to relocate the power in the supply chain. Centralization of distribution was the tool to achieve this.

Tesco adopted a centrally controlled and physically centralized distribution service (Kirkwood, 1984a, 1984b) delivering the vast majority of stores’ needs, utilizing common handling systems, with deliveries within a lead time of a maximum of 48 hours (Sparks, 1986). This involved an extension to the existing company distribution facilities and the building of new distribution centres, located more appropriately with the current and future store location profile. Investment in technology, handling systems and working practices allowed faster stock-turn and better lead times. Components of the revised structure were outsourced, allowing comparisons between contractors and Tesco-operated centres, to drive efficiency.

This strategy produced a more rationalized network of distribution centres, linked by computer to stores and head office. The proliferation of back-up stock-holding points and individual operations was reduced.

These centres were the hubs of the network, being larger, handling more stock, more vehicles and requiring a more efficient organization. Centralization produced the necessary control over the business and fitted with the changed retail strategy of the 1980s (larger company super- stores). Figures 6.1 and 6.2 show the changing store profile and the impact of the distribution changes on corporate stock-holding.

From 1984 the percentage of sales via central facilities has increased from under 30 per cent to over 95 per cent in 2002. By 2003, the annual distribution volume had increased to more than 1 billion cases delivered, out of 25 distribution centres, covering 7 million square feet of warehouse area, holding 9.9 days’ stock for stocked products. The scale of the ambient distribution centre increased: for example Thurrock, which opened in 2002, is 500,000 sq ft with a weekly assembly capacity greater than 1 million cases. A similar very large non-food national distribution centre is located in Milton Keynes with automation for selected product lines.

Centralization proceeded on a product line basis. By 1989 Tesco had 42 depots, of which 26 were temperature controlled. While this was a massive reduction from the plethora of small locations in the 1970s, it was still capable of improvement. Fresh foods were basically handled through single temperature, single-product depots. These were small and inefficient and were subject to only tactical operational improvements, allowing for example more frequent store deliveries and a more accurate idea of the cost of product distribution.

While stores received some improvements in the mid-1980s, there remained some disadvantages of the centralized network. For example, each product group had a different ordering system. Individual store volumes were so low that delivery frequency was less than desired and quality suffered. Delivery frequency was maintained, leading to high empty-running costs and increased store receipt costs. It was prohibitively expensive to have on-site Tesco quality control inspection at each location, which meant that the standards of quality desired could not be rigorously controlled at the point of distribution. It was also realized that this network would neither cope with the growth Tesco forecast in the 1990s nor, as importantly, be ready to meet expected high legal standards on temperature control in the chill chain.

The produce depot at Aztec West in Bristol opened in 1986 and represented the best of the centralized network. Tesco could have made further investment in single-product distribution systems, upgraded the depots and transport temperature control and put in new computer systems, but would still have achieved overall a less than optimal use of resources and cost-efficiency. A strategy of composite distribution was planned in the 1980s to take effect in the 1990s. A subsidiary requirement was the importance of ensuring continuity of service during the changeover period.

Composite distribution enables temperature-controlled product (chilled, fresh and frozen) to be distributed through one system of multitemperature warehouses and vehicles. Composite distribution uses specially designed vehicles with temperature-controlled compartments to deliver any combination of these products. It provides daily deliveries of these products at the appropriate temperature so that the products reach the customers at the stores in the peak of freshness. An insulated composite trailer can be sectioned into up to three independently controlled temperature chambers by means of movable bulkheads. The size of each chamber can be varied to match the volume to be transported at each temperature. The composite distribution network in the UK, including Northern Ireland, now has ten centres, replacing the 26 single temperature centres in the ‘centralized’ network. Half these centres are operated by specialist distribution companies, again enabling comparison of performance.

Composite distribution provides a number of benefits. Some derive from the original process of centralization, of which the composite system is an extension. Others are more directly attributable to the nature of composite distribution. First, the move to daily deliveries of composite product groups to all stores in waves provides an opportunity to reduce the levels of stock held at the stores, and indeed to reduce or obviate the need for storage facilities at store level. The result of this is seen at store level in the better use of overall floorspace (more selling space) and in stock terms by a continuous reduction (see Figure 6.2).

The second benefit is the improvement of quality, with a consequent reduction in wastage. Products reach the store in a more desirable condition. Better forecasting systems minimize lost sales due to out-ofstocks. The introduction of sales-based ordering produces more accurate store orders. More rigorous application of code control results in longer shelf life on delivery, which in turn enables a reduction in wastage. This is of crucial importance to shoppers who demand better quality and fresher products. In addition, however, the tight control over the chain enables Tesco to satisfy and exceed the new legislation requirements on food safety.

Third, the introduction of composite delivery provided an added benefit in productivity terms. The economies of scale and enhanced use of equipment provide greater efficiency and an improved distribution service. Composite distribution strategically provides reduced capital costs and operationally reduces costs through for example less congestion at the store. Throughout the system there is an emphasis on maximizing productivity and efficiency of the operations, enabled by tactical involvement in various new technologies.

The introduction of composite delivery was not a simple procedure. Considerable problems were encountered, requiring Tesco to work closely with suppliers and distributors. The move to composites led to the further centralization of more product groups, the reduction of stock holding, faster product movement along the channel, better information sharing, the reduction of order lead times and stronger code control for critical products. Such changes are easy to list but hard to implement and achieve.

There were also issues that existed post-composite. The need to maintain continuity of service to retail stores, which means that the implementation of improvements must be invisible, affects abilities to change. The cost of primary distribution remained within the buyer ’s gross margin and was not identified clearly and separately. This cost had to be substantiated indirectly by talking to suppliers and hauliers. In other words clarity and transparency were not achieved. Finally and most importantly, certain sectors of the supplier base were fragmented and not fully organized for the needs of retail distribution, despite the concomitant development of retail brand products. That fragmentation made the task of securing further permanent improvements difficult. While many suppliers could reorganize their procedures to meet the changed timing demands of composite delivery, some could not.

This composite structure is essentially the backbone of the current network. In order to increase the volume capability of the composites, Tesco implemented a change to its frozen strategy by commissioning a new automated frozen distribution centre at Daventry. This national frozen centre services Tesco stores by delivering through the composite distribution centres. This enabled the composite frozen chambers to be converted to chill chambers, thus releasing extra volume capability to service Tesco business growth.

The discussion of the phases of supply chain reconfiguration thus far has essentially focused on structural change to the distribution network. Implicit in this is some alteration to the linkages with suppliers and distribution specialists, but in many ways this was ancillary to the internal changes. Once the basic network outline was settled, however, attention turned more fundamentally to vertical collaboration in the supply chain. Information sharing, electronic trading and collaborative improvements have become critical.

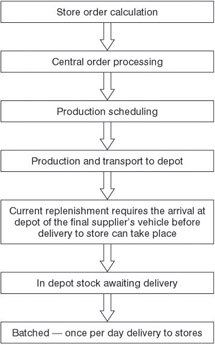

This sharing of information was part of a wider introduction of electronic trading to Tesco. In particular, Tesco built a Tradanet community with suppliers (Edwards and Gray, 1990; INS, 1991). Improvements to scanning in stores and the introduction of sales-based ordering enabled Tesco better to understand and manage ordering and replenishment. Sales-based ordering automatically calculated store replenishment requirements based on item sales, and generated orders for delivery to stores within 24 to 48 hours. This information was used via Tradanet to help suppliers plan ahead both in product and distribution. Delivery notes, invoices and other documentation were also be sent by Tradanet.

In 1997 Tesco gave a commitment to share information with its suppliers. Suppliers could obtain information provided they dedicated resources to focus on Tesco customer wishes and provided appropriate product offerings. This commitment complemented the change in commercial structure to focus on category management and ECR principles. Tesco moved from the traditional single point of contact with suppliers (the buyer and the national account manager) to a more complex interaction in which functions collaborated. A commercially secure data exchange system based on the Internet (Tesco Information Exchange – TIE) was established.

This concern with information provision for collaborative purposes inevitably turned attention on to the practices of primary distribution. The changes to control the supply chain had been concentrated mainly on the distribution centre to the retail store component, but realization began to emerge of opportunities elsewhere.

The purpose of examining primary distribution (manufacturer to distribution centre) was to identify and implement changes that were profitable to the supply chain as a whole. Frequently opportunities occurred through shared user solutions, which are different from the mainly dedicated solutions found in secondary distribution. Primary distribution required some change in approach and style, with Tesco letting go of direct control and allowing appointed hauliers and consolidators greater freedom over the shape of the least-cost, good service solutions.

Once the cost of primary distribution had been calculated, there was business motivation to apply logistics resources to identify opportunities to make improvements in the organization and structure of the inbound flow of goods. The purpose was to reorganize UK, European and worldwide sourcing and distribution networks. Tesco was then able to be proactive in negotiating more competitive distribution rates as a result of the negotiation scale, the command of the sourcing of products and its own expertise in distribution operations. These factors all contributed to enhanced operational efficiency and supply chain profitability. There was a valuable cost contribution that could be made by involving the operators in identifying more efficient ways of organizing primary distribution, and then helping bring those insights to the surface and create solutions that worked for all the segments of the supply chain. It was important in achieving this to work in a cross-functional style, and the primary distribution managers sat in the commercial areas with which they were working. This created a united focus on achieving good results for the business.

The restructuring, information sharing and primary distribution also focused attention on using assets more completely. Tesco’s 3D logistics programme sought to achieve a total supply chain perspective. This inevitably involved considering the flow of goods on shorter time horizons, allowing delivery and distribution to be reconfigured, creating more capacity in existing centres and aligning primary and secondary distribution.

An important part of this alignment relationship development has been the supplier collection programme. Tesco vehicles collect supplier products on their way back to the depot following a store delivery, saving costs and reducing emissions (DETR, 1997). Additionally, suppliers’ vehicles that had delivered to depots or were conveniently in the area were routed to take goods to Tesco retail stores on their way back to their home base. Such collaborations involve three-way partnerships among suppliers, logistics service providers and Tesco.

The overall objective was to create conditions in which the unit cost of distribution reduced year on year, and at the same time, the return on the capital invested in vehicles and centres increased through better coordination and stronger confidence in the information. The result was an important strategic alliance between primary and secondary distribution which examined the peaks and troughs in utilization to find those that were complementary. Alignment of time has been noted above, but other changes also brought full supply chain benefits. One specific opportunity was in the handling and movement of goods, with product increasingly ordered, produced and delivered in merchandise- ready units.

These phases of reconfiguration of the supply chain took Tesco from a position of being at the mercy of suppliers and inconsistent practice to the very leading edge of logistics expertise. Tesco distribution and supply chain was recognized as world class (McKinsey, 1998).

As Jones and Clarke (2002) point out, the process of change outlined above made huge strides towards modernizing Tesco’s supply chain. As a consequence of this, lead times to stores and from suppliers had been cut radically and stock holding reduced enormously (Figure 6.2). Massive progress had been made. However this progress was achieved at a time when Tesco had moved from a standardized, conforming, domestic retailer to one where the retail and supply challenges were multiplying.

These challenges involved internationalization, the development of successful home shopping and operational alterations at store level.

The real process of becoming an international retail operation started in the mid-1990s, when Tesco embarked on a long-term strategy of building a profitable large-scale international business. By 2003, Tesco had successfully established that retail presence in Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Thailand, South Korea, Taiwan and Malaysia. Tesco has recently purchased retail chains in Japan and Turkey. It has become the market leader in five of those international countries, in addition to being number one grocery retailer in the UK. That overseas operation now accounts for almost half the Tesco Group retail space and 20 per cent of retail sales (Tesco plc Annual Report, 2003). The approach is to use local knowledge to tailor the operation and not to spread the business too widely, although other markets remain possible (such as China and the United States – Child, 2002).

One of the lessons in internationalization that Tesco does not have to relearn is the importance of expertise in supply chain logistics. Its UK experiences have provided a solid base for supply chain operations in these international markets. While the extent and the approach vary depending on market circumstances (IGD 2003a), the core processes are being introduced and allowing efficiencies to be gained.

In 1995 Tesco conducted a home shopping pilot scheme at a single store. Customers could use a variety of methods to order, with these orders picked at the store by Tesco staff, and collected or delivered to the customer’s home or drop-off point. This pilot was extended to 10 stores in 1997, and a store-based picking operation was expanded nationally from 1999. By 2003 Tesco.com covered 96 per cent of the UK population geographically and had annual sales of £447 million. A fleet of 1,000 temperature controlled vans was delivering 110,000 orders per week, which is a 65 per cent share of the UK Internet grocery market. A similar approach is now established in the Republic of Ireland and in South Korea, where over 70 per cent of the population has Internet access. Grocery Works, which is a partnership between Tesco.com and Safeway Inc, has established coverage in parts of the western United States.

This store-based model was not the common approach adopted by competitors, and criticism of the approach was ‘vitriolic’ (Child, 2002). Jones (2001) in an interview with John Browett (CEO of Tesco.com) points to three key elements of the decision to use store-picking. First, Tesco realized that warehouse picking schemes could not make money. Second, customers wanted the full range of products, and economics showed Tesco needed the wide range to drive basket size. Third, geographic coverage from warehouses is insufficient. The Tesco.com experiment is now profitable, and has shown to some extent how supply chain systems can add value to the business in new ways. The Internet however places pressure on the accuracy of speed of supply chain systems, forcing even Tesco to look again at the processes (see later).

The retail base of Tesco has also changed domestically from the 1980s. The present-day Tesco is a multi-format retailer with formats ranging from Extra hypermarkets to small Express convenience stores. This variation has been compounded by retail operational changes. Store opening hours have been extended in many locations to encompass 24-hour opening. Service levels and quality thresholds have been enhanced. Non- food has become a much greater proportion of even standard store offers than before. Product ranges, operating times and service standards all combine to pressurize a supply system that was essentially developed for a simpler, more standard situation.

The extension to non-food lines, the growing internationalization of the business (including product sourcing) and the consumer demand for fresh products also come together to internationalize the supply chain. From being heavily domestic in nature, the procurement of products from overseas has become a key feature of the business. This breadth of supply again demands efficiency in the supply chain.

The current Tesco supply chain network is well documented (IGD, 2003b). This report shows that there are 25 distribution depots with a warehouse area of 7.3 million square feet and annual total case volumes of 1.17 billion. Centralized distribution accounts for 95 per cent of the volume. Of these 25 depots, 15 are run in-house by Tesco and the remainder are contracted to Wincanton (five), Exel Logistics (two), Tibbett and Britten (two) and Power Europe (one). National Distribution Centres (four) are combined with Regional Distribution Centres (ambient) (nine, of which four are ‘mega-sites’, three fast-moving sites and two medium-moving sites), Composite Distribution Centres (one) and Temperature Controlled Depots (11, including seven fresh foods, three fresh and frozen and one new frozen site). In additional there are 24 consolidation centres run by a variety of operators which feed into this system. The system operates almost 3,000 vehicles, covering 224 million km per annum. In short, this is an extensive, large-scale network of supply.

The operations of the components of this network have also undergone radical change. Performance is now much more rigorously monitored, mainly through the ‘steering wheel’ approach widespread throughout Tesco. Any distribution centre steering wheel focuses on Operations (safety and efficiency), People (appointment, development, commitment and values), Finance (stock results, operating costs) and the Customer (accuracy, delivery on time). Through such performance measuring at all levels, quality standards are maintained and enhanced.

Jones and Clarke (2002) point out that despite the successes of the reconfiguration of the Tesco supply chain in the 1980s and 1990s noted above, analysis of the chain pointed to a number of areas where benefits could still be achieved. In a much quoted example, a can of cola was followed in the supply chain from a mine (for the metal to make the can) to the store. It was discovered that it took 319 days to go through the entire chain, of which time only 2 hours was spent making and filling the can. This process involved many locations, firms and trips (Jones and Clarke, 2002; Jones, 2002, Jones, 2001). As Jones and Clarke note, ‘even in the best-run value streams there are lots of opportunities for improvement’ (2002: 31).

This can example is one illustration of the first step in a process under- taken by Tesco (Jones and Clarke, 2002). This first step involved the mapping of the traditional value stream. This mapping process demonstrated the stop–start–stop nature of the value stream (Figure 6.3). Second and consequently therefore, value streams that ‘flowed’ were created/designed (Figure 6.4). Third, arising from flow principles, Tesco began to look at synchronization and aspects of lean manufacturing by its suppliers. Finally, Tesco utilized its consumer knowledge from its loyalty card to rethink what products and services should be located where in the value stream (Humby et al , 2003). Jones and Clarke (2002) describe this process as the creation of a ‘customer-driven supply chain’. Others might use the term ‘demand chain’. This process is essentially where Tesco is currently in terms of its supply chain.

Clarke (2002) describes the five big supply chain projects that Tesco is currently engaged in (see also IGD, 2003a) and which derive essentially from the process outlined above:

Continuous Replenishment (CR)

CR was introduced in 1999 and has two key features.First, there is a replacement of batch data processing with a flow system, and second, using the flow system, multiple daily orders are sent to suppliers allowing for multiple deliveries, reducing stockholding through cross-checking and varying availability and quality. This approach has been extended since 1999 (Table 6.1) and has further potential both domestically and internationally.

In-Store Range Management

Based on customer behaviour data and stock-holding capacity analysis at store, Tesco can now produce store-specific planograms and store-specific ranging. The system is designed to improve store presentation as well as stock replenishment and availability. Tesco is able to provide the exact stock requirement for specific shelves in specific stores to its out-replenishment system. This system is being rolled out in 2003/5.

Network Management

Network management attempts to integrate and maintain the network assets and extend the life of the system. Two new sites in 2001 added 18 per cent to the capacity of the system. The frozen element of the composite system has been centralized in a new frozen centre, allowing chill and ambient expansion in the released space. Cross-docking is used at the regional centres for frozen and slow-moving lines. Consolidation centres provide fresh produce for cross-docking. These changes have produced a more integrated network which has made better use of the assets, extended the life of centres and improved performance by selecting the right ‘value stream’ for appropriate products.

Flow-Through

As noted above, flow-through or cross-docking is now more extensive. Product storage is now much reduced and increasingly distribution centres have no racking and do not store product. The importance of cross-docking is set to increase, given the substantial savings delivered from reduced stock holding. A different but nonetheless important aspect of flow-through is the use of merchandisable ready units to allow product to be put on sale in stores without extra handling. Such units (often called ‘dollies’) are increasingly common in fast-moving items, but can be used for many other items as well.

Primary Distribution

Primary distribution and factory gate pricing (FGP) is the area of focus for cost reduction in inbound logistics. Primary distribution is the term Tesco prefer, seeing the process as a ‘strategic change in the way goods flow... (and about) achieving efficient flows and not a pricing process’ (Wild, quoted in Rowat, 2003: 48). However cost reduction is a key driver behind the interest in primary distribution. Essentially, primary distribution is about control (and pricing) of the supply chain from the supplier despatch bay to the goods in bay of the retail distribution centre. It separates out the cost of transportation from the purchase price of the product itself, and by putting it into a separate primary distribution budget, it allows direct control and analysis by Tesco. By March 2003, 30 per cent of all Tesco inbound freight was under such agreements, which amounts to 300 million cases annually or 10,000 deliveries a week from 500 suppliers.

Prior to this initiative, the commercial buyer used to purchase products at a price which included the delivery by the supplier into the retail distribution centre. The gross margin, on which buyers are measured for performance, is the difference between this purchase price and the price charged to the consumer at the retail store. Hence, as can be imagined, removing the transport cost element from that purchase price impacts on the way the gross margin is calculated, and the commercial buyers have to adjust their targets accordingly. It is a major financial development within a retail organization to implement such a change and still retain strict control over the disciplines of making individual buyers accountable for achieving the new level of gross margins during the period of transition. Primary distribution is a strategy that requires the cooperation of the whole of the supply chain including the retail buyers. This Tesco achieved by bringing together cross-functional teams and by the full endorsement of the policy from senior directors including the chief executive.

Naturally the suppliers, and their transport service providers, went through quite major changes to their arrangements for the delivery of their goods to the retail distribution centres, as they implemented this policy planned by the primary distribution team at Tesco. It was now the retailer, not the supplier, that appointed which transport and distribution companies would do this work, at a price negotiated directly between the retailer and the logistic service provider. It is not surprising, therefore, that there was some adverse reaction in the industry, especially from those transport operators that had lost work as a result. As a result the remaining volume from those suppliers and manufacturers, which they still had to deliver to other retailers, was no longer at a volume and delivery pattern that was economical without raising costs. This, they said, was the direct result of the primary distribution decisions made by the retailer to reorganize the consolidation of product delivery.

The case put forward by the retailer was that to maximize competitive advantage, the whole supply chain needed to be aligned with the demand patterns of consumers, and that this must now include primary distribution. It further argued that it saw no justification for other retailers to benefit from the economies of scale derived from the major retailers, which ordered the majority of the volume. Factory gate pricing is a sign of a very mature retail supply chain. It provides both full visibility of the costs and the accountability to organize how the primary network is structured. It requires a high level of co-operation between suppliers and retailers to leverage the benefits of a fully controlled supply chain. The result for Tesco is significant cost savings and thus lower prices for consumers. For those involved with Tesco in this there are major opportunities for the most efficient distributors, and the manufacturers may see their jobs becoming simpler, through changed collection and back- hauling procedures. Tesco’s vision for primary distribution is an in-bound supply chain which is visible, low-cost, efficient and effective.

The current position for Tesco’s supply chain is therefore again one of change. The reconfiguration of the 1980s and 1990s has now been modified by the conceptual and intellectual approaches of the recent years. The ideas of how a supply chain should look, perform and be costed are sweeping through the existing system and those that supply product into it. In the same way that Tesco itself does not stand still, so too the supply system is having to adapt and change.

It is impossible to fully predict the future and to state categorically what the Tesco supply chain will look like in the coming years. Some things are known, however. The processes and procedures described above that have been put in place by Tesco have at least five more years to run. They will change the supply chain but represent the continuing evolutionary influence of developments already known. Likewise, work in the area of environmental aspects of logistics will continue to place pressure on retailers and suppliers to improve their performance. Key performance indicators at government and other levels are becoming more fundamental (for example DETR, 1999; DfT, 2003a, 2003b). Concerns about the environment and about aspects of recycling and reuse will continue to be influential.

Perhaps however the future could be more radical? While the concerns above will undoubtedly be maintained and influence supply systems, the processes put in place may also have more wide-reaching consequences. Tesco is at the beginning of understanding all the issues in primary distribution. Manufacturers likewise are only now getting to grips with some of these issues. Is the scene set therefore for a more fundamental examination of the supply relationships? Jones (2002) puts forward a variety of scenarios for grocery supply chains. All have at their heart a move away from the current system of bigger, centralized and dispersed to a model of faster, simpler and local. Such a system focuses on moving value creation towards consumers and eliminating non-value creation steps in supply. Information systems are simplified so as to avoid order amplification and distribution. The supply chain is thus compressed in space and time, producing and shipping closer to what is needed just in time. As Jones (2002) concludes, ‘We can not predict exactly what forms these developments will take.… Nevertheless there are huge opportunities for improving the performance of the grocery supply chain, for those willing to think the unthinkable.’

This chapter aimed to understand and account for the changes in logistics in food retailing by examining changes in Tesco logistics. The basic premise was that the transformation of retailing that the consumer sees at store level has been supported by a transformation of logistics and supply chain methods and practices. In particular, there has been an increase in the status and professionalism in logistics as the time, costs and implications of the function have been recognized. Professionalism has been enhanced by the transformation of logistics through the application of modern methods and technology. For all retailers, the importance of distribution is now undeniable. As retailers have responded to consumer change, so the need to improve the quality and appropriateness of supply systems has become paramount.

The Tesco study demonstrates many aspects of this transformation. In response to a clear business strategy, logistics and supply chains have been realigned. From a state of decentralization and poor control, the company has moved through centralization and composites which enabled control to be exercised stringently. These in turn have led to new methods and relationships in supply systems, both within Tesco and throughout the supply chain. Logistics does not stand still, and recognition of the need to think clearly about supply pervades the case study. The developments outlined above and the transformation described are not the ultimate solutions. As consumers change their needs, so retailing must and will respond. As retailing responds, companies will modify their operations, not least their logistics, or be placed at a competitive disad- vantage.

Akehurst, G (1984) Checkout: the analysis of oligopolistic behaviour in the UK grocery retail market, Service Industries Journal , 4 (2), pp 198–242

Burt, S L and Sparks, L (2002) Corporate branding, retailing and retail internationalisation, Corporate Reputation Review , 5 (2/3), pp 194–212

Burt, S L and Sparks, L (2003) Power and competition in the UK retail grocery market, British Journal of Management , 14, pp 237–54

Child, P N (2002) Taking Tesco global, McKinsey Quarterly , 3, pp 135–44

Clarke, P (2002) Distribution in Tesco. Presentation for Tesco UK Operations Day 2002 [Online] www.tesco.com/corporateinfo/ (accessed 20 Sep 2002)

Corina, M (1971) Pile It High, Sell It Cheap , Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London

Department of Environment, Transport, and the Regions (DETR) (1997) Good Practice Case Study 364: Energy savings from integrated logistics management, Tesco plc , HMSO, London.

DETR (1999) Energy Consumption Guide 76: Benchmarking vehicle utilisation and energy consumption, measurement of Key Performance Indicators, HMSO, London

Department for Transport (DfT) (2003a) Benchmarking Guide 77: Key Performance Indicators for non-food retail distribution , HMSO, London

DfT (2003b) Benchmarking Guide 78: Key Performance Indicators for the food supply chain , HMSO, London

Edwards, C and Gray, M (1990) Tesco case study, in Electronic Trading , DTI, HMSO, London

Fernie, J (ed) (1990) Retail Distribution Management , Kogan Page, London

Fernie, J (1997) Retail change and retail logistics in the UK: past trends and future prospects, Service Industries Journal , 17 (3), pp 383–96

Humby, C, Hunt, T and Phillips, T (2003) Scoring Points: How Tesco is winning customer loyalty , Kogan Page, London

Institute of Grocery Distribution (IGD) (2003a) The Tesco International Report , IGD, Watford

IGD (2003b) Retail Logistics 2003 , IGD, Watford INS (1991) Tesco: Breaking down the barriers of trade , INS, Sunbury-on-Thames

Jones, D T (2001) Tesco.com: delivering home shopping, ECR Journal , 1 (1), pp 37–43

Jones, D T (2002) Rethinking the grocery supply chain, in State of the Art in Food , ed J-W Grievink, L Josten and C Valk, Elsevier, Rotterdam [Online] www.leanuk.org/articles.htm (accessed 30 Oct 2003)

Jones, D T and Clarke, P (2002) Creating a customer-driven supply chain, ECR Journal , 2 (2), pp 28–37

Kelly, J (2000) Every little helps: an interview with Terry Leahy, CEO, Tesco, Long Range Planning , 33, pp 430–39

Kirkwood, D A (1984a) The supermarket challenge, Focus on PDM , 3 (4), pp 8–12

Kirkwood, D A (1984b) How Tesco manage the distribution function, Retail and Distribution Management , 12 (5), pp 61–65

MacLaurin, I (1999) Tiger by the Tail , Macmillan, London

Mason, T (1998) The best shopping trip? How Tesco keeps the customer satisfied, Journal of the Market Research Society , 40 (1), pp 5–12

McKinsey Global Institute (1998) Driving Productivity and Growth in the UK Economy , McKinsey, London

Powell, D (1991) Counter Revolution: The Tesco story , Grafton Books, London

Reynolds, J (2004) An exercise in successful retailing: the case of Tesco, chapter 26 of Retail Strategy: The view from the bridge , ed J Reynolds and C Cuthbertson, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford

Rowat, C (2003) Factory gate pricing: the debate continues, Focus , Feb, pp 46–48

Seth, A and Randall, G (1999) The Grocers , Kogan Page, London

Smith, D L G (1998) Logistics in Tesco: past, present and future, in Logistics and Retail Management , ed J Fernie and L Sparks, pp 154–83, Kogan Page, London

Smith, D L G and Sparks, L (1993) The transformation of physical distribution in retailing: the example of Tesco plc, International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research , 3 (1), pp 35–64

Sparks, L (1986) The changing structure of distribution in retail companies, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers , 11 (2), pp 147–54

- Retail Logistics: Changes and Challenges

- Relationships in the Supply Chain

- The Internationalization of the Retail Supply Chain

- Market Orientation and Supply Chain Management in the Fashion Industry

- Fashion Logistics and Quick Response

- Temperature-Controlled Supply Chains

- Rethinking Efficient Replenishment in the Grocery Sector

- The Development of E-tail Logistics

- Transforming Technologies: Retail Exchanges and RFID

- Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Systems: Issues in Implementation

show all menu

- Forming Your Kanban Team

- Developing a Kanban Design

- Initial Startup and Common Pitfalls

- Appendix C Two-Bin Kanban Systems

- Appendix G Intra-Cell Kanban

- Domain 1 Installation, Configuration, and Upgrading

- Domain 2 Diagnosing and Troubleshooting

- Domain 3 Preventive Maintenance

- Domain 3 Diagnosing and Troubleshooting

- Domain 4 Networks

- Team change

- Organizational change

- Restructuring

- Mergers and acquisitions

- IT-based process change

- Overview of the Windows Script Host

- Processing Collections of Data

- Using Procedures to Organize Scripts

- Appendix A WSH Administrative Scripting

- Appendix C Whats on the CD-ROM?

- Starting Diagrams by Using Templates

- Adding Decorative Elements to Diagrams

- Laying Out Office Spaces

- Creating Network Diagrams

- Get(LastError)

- Get(ScriptResult)

- LeftWords()

TESCO – British Retailer that redefined Grocery Shopping

The first time I visited a ‘Tesco Extra’ store was at midnight, making an emergency run for next morning’s breakfast. The store seemed to occupy the area of an entire football field in Ashby-De-La-Zouch, UK. Even at an ungodly hour, Tesco was well-lit with visiting customers.

Inside, there were never-ending aisles lined up with groceries, food items, clothing, electronics, and whatnot. It was easy to lose way and lose track of time in the colossal supermarket.

I thought to myself that this would be the only store of its kind in the county, but I was wrong.

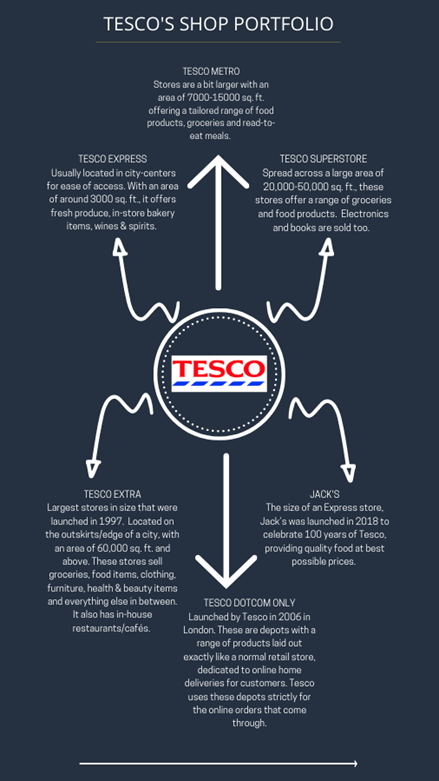

Tesco has 4008 stores across the UK and Republic of Ireland , with 7005+ stores and franchises across the world. In Europe, Tesco has established itself in Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland and Turkey. In Asia it has stores in Thailand, South Korea, Malaysia, Japan and China.

TESCO is much more than a chain of supermarkets selling a million products. It’s a giant conglomerate, spanning across so many verticals. It’s the equivalent of one of the FAANG companies but in the Grocery & Retail sector. It becomes imperative for business enthusiasts like you and me to understand the business model of this retail giant called Tesco.

It’s considered a part of the ‘Big Four’ supermarkets alongside ASDA, Sainsbury’s, and Morrison’s in Europe.

The Birth of Supermarkets in Britain

Founded in 1919 by a war veteran – Jack Cohen , Tesco began as a grocery stall in the East End of London, making a profit of £1 on sales of £4 on day one. Tesco’s first store was launched in 1929, selling dry goods & its own brand of Tesco Tea. A hundred more Tesco stores were opened in the next 10 years.

With 100+ mom-and-pop stores in Britain, Jack wanted to expand his product range. He traveled to the US in 1946 and noticed the self-service system, where customers would select different products on the shop floor and finally checkout at a counter. Jack brought this concept back to Britain, giving birth to Tesco Supermarkets and changing the face of British Shopping. His motto was to “stack ‘em high, and sell ‘em low (cheap).”

Tesco has a wide range of supermarkets depending upon their size, range of products, and location. This also helps regulate their Supply Chain to reduce wastage.

Tesco Business Model is based on various verticals

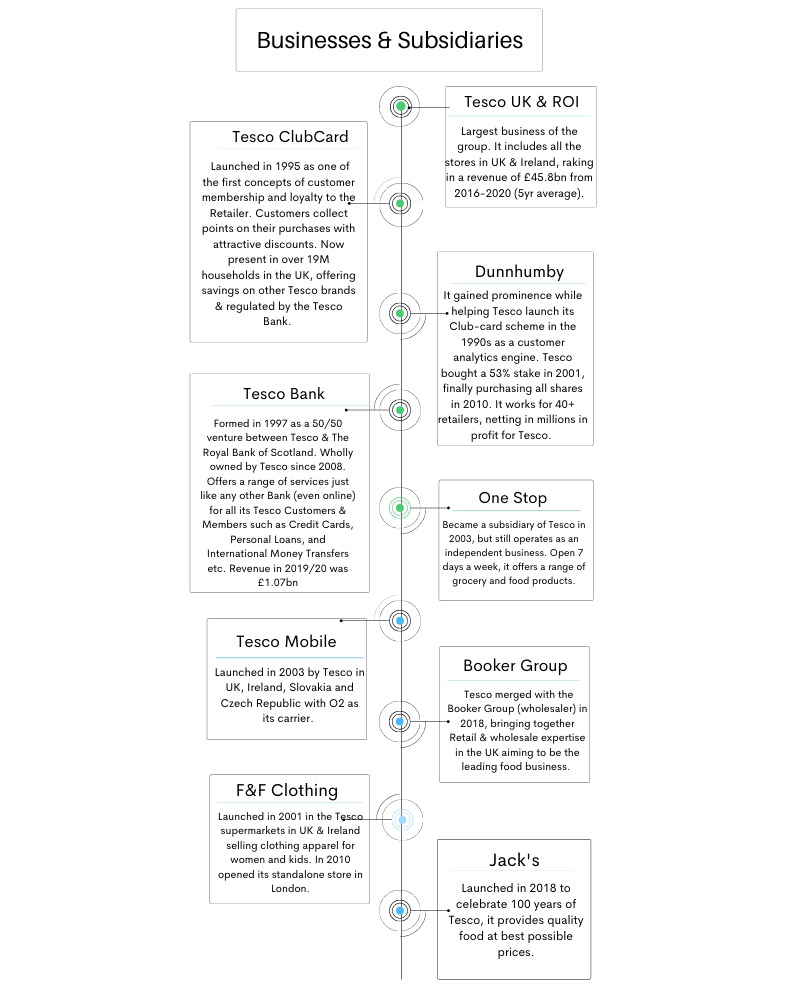

Tesco has deep-rooted its businesses in the European market so well, it’s difficult to miss out on the Tesco hoarding anywhere. Its Businesses and subsidiaries are:

A glimpse into the Complex Supply Chain

A supply chain is one of the critical aspects of the business model of a giant retailer like Tesco. Tesco has its priorities set when it comes to procuring products from different parts of the world:

- Use expertise to offer a better range of products at reasonable prices

- Use economies of scale to buy more for less

- Leverage and maintain relations with global branded suppliers

- Grow the brand

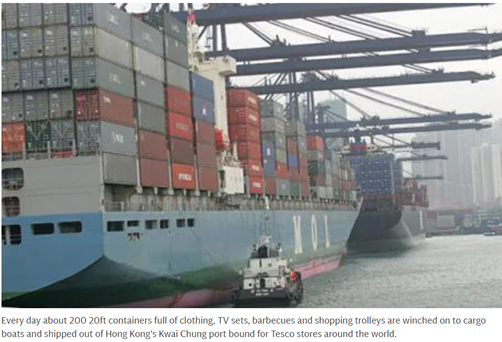

It procures goods from over 44 countries, majorly China. A stock of up to 90,000 different products (30% are food & beverages) is transferred via the global sourcing office located in Hong Kong. Keeping wholesalers out of the loop, Tesco procures directly from suppliers. The conglomerate has developed and maintained long-lasting relations with suppliers’ world over—the main ones being General Mills, Kellogg, Mars, and Princes.

Tesco has set up a separate division to regulate its supply chain, “the machine behind the machine” – Tesco International Sourcing (TIS). It can be compared to the East India Company of the 18 th -19 th Century, catering to only one customer – Tesco.

TIS is connected to over 1000+ suppliers across 1200+ factories . It’s responsible for over 50,000 Tesco product lines in terms of quality control, sourcing, production, designing, timely delivery, and sorting trading/customs documentation.

All activities are coordinated centrally at TIS, with just 533 staff members. These staff members undergo rigorous training to detect & analyze Supplier-violations and conduct Auditing.

Tesco coordinates with TIS on a daily basis to procure products in the following ways:

- The local team uses customer insights to create a Product Brief (new or modified) specified for each region.

- TIS analyzes the product brief and develops a Product Sourcing Plan depending upon – stores that need this product and figuring out minimum transport time and cost, as per the region.

- The Plan is executed, and specific demands are handed out to Suppliers all over the world. Expert TIS Buyers make sure the best deal is made.

- Inbound logistics are consolidated at specific Tesco Depot to receive the product efficiently from Suppliers.

- Local teams then make sure the product is distributed to different Tesco stores from the Depots.

Tesco adding eCommerce to the mainstream business model

Being in the Top 50 retailers globally as of 2021 , Tesco’s annual revenue worldwide in 2020 was £58.09B , a 9.1% decline from 2019 (due to the Pandemic & disposing of its Asia operations , to focus on the core business in Europe).

It shifted from Brick & Mortar to Brick & Click stores. The Click+Collect functionality on its website accounts for 43% of E-grocery sales in the UK. The Click+Collect concept enables customers to place their orders online and collect their orders a few hours later at the nearest Tesco Depot. Tesco created these specialized Depots for online orders only.

Despite shutting down most its mall operations, Tesco survived 2020 through its online retail store Tesco.com , with double the orders. Its E-commerce net sales had shot up by 31% from 2019-2021.

A Global Operations & Technology Center in Bengaluru was also set up in 2004. This center serves as the backbone of distribution operations for Tesco worldwide. Its business functions are- Finance, Property, Distribution Operations, Customers & Product. The employees at this Center are Engineers, Analysts, Designers, and Architects.

Tesco’s Marketing Strategy

Tesco has always believed in acquiring loyal customers and regaining stakeholders’ trust. It aims to reach customers from all financial backgrounds. So it launched 2 of its own sub-brands – Tesco finest for the affluent customers and Tesco Everyday Value for the rest of the crowd.

Tesco also launched the Club Card in 1995 as a Membership card, to maintain customer loyalty and keep them coming back. The Card operates on a point-based system with discounts on products, & other subsidiaries like double data on Tesco Mobile. With 5 Million subscribers in the first year , Tesco finally overtook its competitor – Sainsbury’s to become No.1 in the UK.

The Club-card strategy was used to obtain customer data and observe buying habits. This data was analyzed, allowing Tesco to put the right products on shelves while eliminating unpopular ones. Tesco realized that the Club Card isn’t just a quick fix & temporary promotional tool; it’s a promotion in itself. This made the Tesco Club Card unique and long-lasting.

Tesco also realized that spending Billions on traditional marketing efforts and maintaining a ‘one-size-fits-all’ brand image wouldn’t work. It decided to hyper-target specific customers and to earn their trust. For starters, thousands of head-office staff and senior executives were sent to work in stores – to demonstrate how Tesco values its customer. Customization became key for its new marketing strategy; sending out discounts on birthdays via Emails and campaigning from door-to-door.

Tesco also made a partial shift to Digital Marketing which costs much lesser and has a wider outreach. It created well-tailored profiles on all social media platforms. On Twitter, it has more than 15 accounts, separate for each of its business units. The online customer care account on Twitter is active 24-7.

All supermarkets commonly advertised themselves to have quality products at a reasonable cost; Tesco wanted to differentiate itself as a unique brand. It introduced step-by-step Recipes prepared from ingredients available at any Tesco store, with Chef Jamie Oliver as its Health Ambassador . Tesco Food and its variety of recipes were a massive hit. Later on, the monthly Tesco Magazine as a food & lifestyle magazine was also launched, with 4.65Million readers worldwide.

The beginning of the pandemic in March 2020 left people apprehensive about visiting a physical store to buy groceries. To deal with customers’ concerns, Tesco came up with an instructional advertisement in April ‘20. With crisp instructions similar to that of an in-flight safety video, this ad showed customers how to physically shop and behave at Tesco stores. It was considered to be the most effective advertising and communications campaign of 2020 as per YouGov BrandIndex .

Competition

Tesco’s earliest competitor has been Sainsbury’s since the 70s. The Tesco Club Card strategy in 1995 helped it overtake Sainsbury’s to become the No.1 Retailer in the UK, but not for long. The ‘Big Four’ supermarkets in Europe have been in close competition throughout the years. Tesco has acquired a 28% majority stake in the UK market.

The horse meat and accounting scandals were a real setback for Tesco, letting competitors take over the European market. The newest German entrants – Aldi and Lidl had caught customers’ attention and market share in a short span of time.

With a combined market share of 12%, these German retailers posed a threat to Tesco. So much so that Tesco began the ‘ Aldi Price Match ’ campaign to curb the growth of the German discounter and win back customers. Tesco started price-matching thousands of its products with that of Aldi, offering better quality and branded products at Aldi’s prices.

Tesco has a majority market share in Britain, with Sainsbury’s and ASDA in tow:

Tesco Adding Sustainability to its business model – The Little Helps Plan

It’s a well-known fact that giant conglomerate retailers are one of the major causes of rapid climate change and increasing carbon footprints. Tesco realized its impact on the planet and launched the Little Helps Plan as a core part of business in 2017. This plan serves as a framework to attain long-term sustainability. Its four Pillars – People, Products, Planet, and Places are aligned with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Until now, the Plan has enabled Tesco to:

- Permanently remove 1 Billion pieces of plastic from its packaging

- Redistribute 82% of unsold food, safe for human consumption

- Remove 52Billion unnecessary calories from foods sold

Apart from this, it also aims to increase sales of Plant-Based Meat alternatives by 300% by 2025. At present, it has 350 plant-based meat alternatives on the shelf.

Apart from partnering with various other organizations, Tesco entered a 4-year partnership with World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) to address one of the biggest causes of wildlife loss – the global food system. It aims to eliminate deforestation from products, promote recyclable/compostable packaging and minimize food waste.

Tesco is one of the few successful retailers in the world, with a compelling history. Tesco has overcome numerous issues across its supply chain, faced global criticism, and still stands undeterred in the European market with its rock-solid business model. It has always adapted to its unpredictable consumers and continues to do so while caring for the planet.

The business is healthy. We said we would rebuild the relationship with the brand and consumers; you will see that in every measure of customer satisfaction we do that. The business is healthy, vibrant and there is a lot of optimism of what we can do going forward. CEO Dave Lewis, who took over Tesco in 2014 (during the struggle years) & stepped down in September 2020

-AMAZONPOLLY-ONLYWORDS-START-

Also, check out our most loved stories below

Why did Michelin, a tire company, decide to rate restaurants?

Is ‘Michelin Star’ by the same Michelin that sells tires, yes, it is! But Why? How a tire company evaluations became most coveted in the culinary industry?

Johnnie Walker – The legend that keeps walking!

Johnnie Walker is a 200 years old brand but it is still going strong with its marketing strategies and bold attitude to challenge the conventional norms.

Starbucks prices products on value not cost. Why?

In value-based pricing, products are price based on the perceived value instead of cost. Starbucks has mastered the art of value-based pricing. How?

Nike doesn’t sell shoes. It sells an idea!!

Nike has built one of the most powerful brands in the world through its benefit based marketing strategy. What is this strategy and how Nike has used it?

Domino’s is not a pizza delivery company. What is it then?

How one step towards digital transformation completely changed the brand perception of Domino’s from a pizza delivery company to a technology company?

BlackRock, the story of the world’s largest shadow bank