Timeless Fashion Hub

- Baroque and Rococo

- 21st Century Trends

- Fashion Conservation

- Fashion Publications

The Legacy of Baroque and Rococo Fashion: Influence on Modern Designers

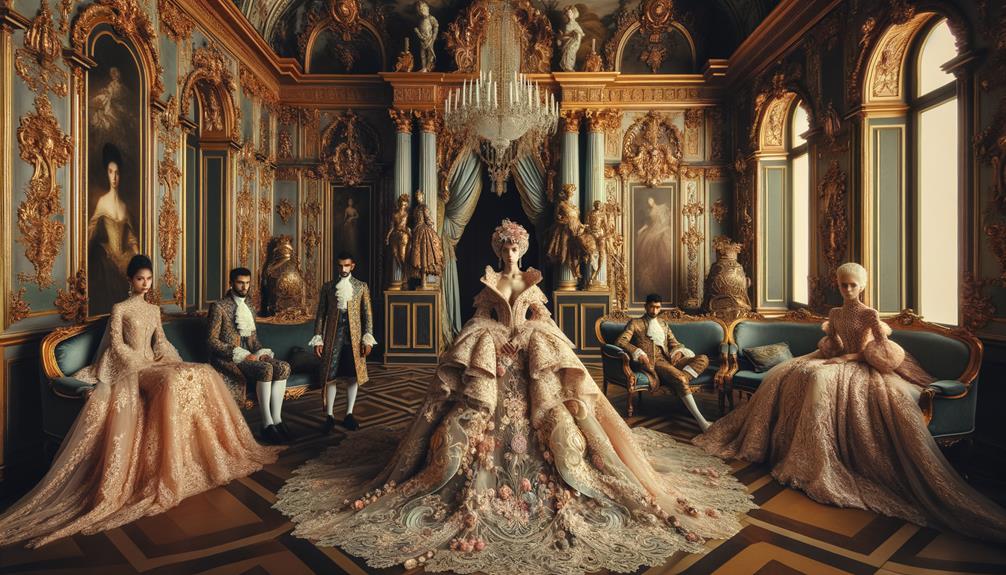

Over 300 years later, the lavish aesthetics of Baroque and Rococo fashion continue to captivate today's designers. Around 15% of modern runway collections draw inspiration from these historic eras, with designers incorporating their intricate patterns and opulent embellishments .

The dramatic silhouettes and luxurious fabrics of the 17th and 18th centuries find new life in contemporary high fashion. It's fascinating to see how these old-world styles are reinterpreted to resonate with modern tastes. From the swirling, ornate details to the grand, voluminous shapes, these historic influences remain a constant source of inspiration for today's fashion innovators.

What is it about the Baroque and Rococo aesthetic that continues to allure designers and delight audiences? Exploring this enduring legacy provides insight into how the past can shape the present and future of fashion.

Origins of Baroque Fashion

In the early 17th century, fashion underwent a dramatic transformation , heavily influenced by the Catholic Church and European royalty . The Baroque style was defined by its grandeur and excess, evident in the elaborate brocade fabrics , intricate embroidery, and layers of lace adorning the garments. It wasn't just about clothing; it was a display of wealth, power, and authority.

King Louis XIV of France played a crucial role in shaping Baroque fashion. His influence ensured that fashion was not merely functional but a statement of political prestige . The opulent, highly decorative styles included towering wigs and exaggerated, sculptural silhouettes. Men's fashion featured doublets, breeches, and codpieces, while women embraced corsets, hooped skirts, and ornate headdresses.

Baroque fashion's focus on the ornamental and the dramatic set it apart. It wasn't just about what was worn but how it was worn. Each piece was an affirmation to the era's love for the grandiose. This period laid the groundwork for the more whimsical Rococo style, but it remains a testament to a time when fashion was a vehicle for opulence and authority .

Evolution to Rococo Style

The Rococo style emerged in the 1730s, bringing a lighter, more whimsical touch to fashion. This was a stark contrast to the grandeur of the preceding Baroque period . The opulent formality of Baroque elements gave way to delicate tones and playful spontaneity. French Rococo fashion became a canvas for this transformation, where men's attire retained the structured French suit but embraced longer, flared-out overcoats.

Women's Rococo fashion evolved extensively. The silhouette for women became looser, shedding the rigid constraints of previous decades. The robe à la française epitomized this shift, cinching the front waist while allowing the back to flow freely. This style, alongside the robe volante , offered a blend of elegance and ease that was unprecedented.

Madame de Pompadour, King Louis XV 's mistress, became an icon of Rococo fashion. Her extravagant hairstyles and opulent clothing choices set trends that rippled through society. Under her influence, fashion became a reflection of wealth and pleasure , yet it also signaled the excesses that would later contribute to societal upheaval.

The evolution to Rococo style was not just a change in aesthetics but a cultural shift , echoing the desires for innovation and individual expression that still resonate today.

Key Elements of Baroque

When I think about Baroque fashion , I'm struck by the intricate textile patterns, lavish decorations , and dramatic silhouettes . These elements weren't just about style – they were a way for the wealthy to showcase their power and affluence. It's fascinating how these grandiose features continue to inspire modern designers today. The Baroque style remains a captivating influence on contemporary fashion, blending opulence and innovation in a way that continues to capture the imagination.

Ornate Textile Patterns

Baroque fashion dazzles with its intricate floral and scrolling motifs , revealing a love for luxury . During the Baroque period , textile designs became increasingly complex , embracing an ornate and decorative style that captivated the wealthy aristocrats of the time. These highly decorated fabrics, such as brocade, damask, and velvet, featured rich floral patterns and naturalistic themes, often woven with metallic threads.

The Rococo era continued this trend, but with a lighter, more playful look. Yet the essence remained: a celebration of extravagance and grandeur. Today's fashion designers have not ignored this legacy. Instead, they've reinterpreted these historical elements, drawing inspiration from the Baroque period's lavish textile designs to create contemporary pieces that speak to modern aesthetic sensibilities.

In the fashion industry, this influence is seen in collections that emphasize detailed embroidery and complex patterns, a nod to the past's opulent artistry. The intricate designs serve as a bridge between eras, showcasing how historical motifs can innovate and infuse modern fashion with a sense of depth and richness. It's a testament to the enduring appeal of ornate and decorative styles, proving that true elegance is everlasting.

Lavish Embellishments

During the Baroque period, fashion was characterized by lavish ornamentation . Intricate embroidery , delicate lace , and ornate trimmings transformed garments into true works of art , mirroring the era's artistic and architectural styles. Baroque fashion featured heavily brocaded fabrics with shimmering metallic threads that dazzled under candlelight.

Jewel-encrusted accessories and towering wigs were not merely decorative, but symbols of wealth and status. These embellishments reflected a society that reveled in excess. Tailored coats and voluminous skirts were adorned with feathers, creating dramatic silhouettes that captivated the eye. The structured corset further accentuated the era's commitment to grandiose proportions.

The succeeding Rococo style continued this tradition with a more lighthearted touch, yet the essence of Baroque's lavish ornamentation remained influential. Today, modern designers draw inspiration from these historical elements, integrating them into contemporary fashion. The meticulous detailing and opulence are not relics, but enduring sources of inspiration. Baroque and Rococo's legacy lives on, evident in the jewel-studded gowns and feathered accessories seen on today's runways.

Dramatic Silhouettes

Few eras in fashion embraced dramatic silhouettes quite like the Baroque era . Baroque fashion was all about exaggerated shapes , with structured bodices , puffed sleeves, and voluminous skirts . These elements combined to create a striking, almost sculptural female form. Luxurious fabrics like silk, velvet, and lace were often embellished with intricate embroidery and jewels, adding to the opulence.

The hooped skirts and high-collared, boned bodices were key in achieving these dramatic fashion statements. They didn't just shape the body; they transformed it into something grandiose and theatrical. Menswear wasn't left out either. Stiff, structured pieces like the codpiece, doublet, and cloak conveyed a distinct sense of power and authority.

The influence of these dramatic silhouettes is still evident today, particularly in high fashion and couture collections. Modern designers often draw on the exaggerated shapes and luxurious materials of Baroque fashion to create pieces that are both nostalgic and innovative. The essence of the Baroque era continues to captivate and inspire, even centuries later.

Rococo Aesthetics and Themes

In the early 18th century, Rococo art embraced a world of delicate pastels, intricate details, and playful elegance. This style emerged as a reaction against the formal Baroque period, bringing a lightness that permeated Rococo art, fashion, and architecture.

Pastel colors filled canvases and salons, creating spaces of whimsy and charm. Rococo artists like Fragonard and Boucher captured the leisurely lives of the aristocracy in their intimate, often erotic scenes.

The Rococo aesthetic evoked emotions of:

Rococo fashion mirrored these artistic tendencies, with opulent fabrics, elaborate embroidery, and an emphasis on curves and asymmetry. This style spread across Europe, influencing everything from furniture to the decorative arts.

Though the Rococo period's pursuit of luxury and indulgence produced beautiful works, it also hinted at the societal divides that would eventually lead to the French Revolution.

Observing the Rococo era, it's clear how the aesthetics of this time wove together themes of beauty, pleasure, and transience. The legacy of Rococo's playful elegance continues to inspire, offering a reminder of art's power to shape and reflect society.

Modern Designers Inspired

When I look at the latest fashion collections, I'm struck by the resurgence of intricate detailing and luxurious fabrics. Designers like Giambattista Valli and Tom Ford draw heavily from the Baroque and Rococo eras , echoing the opulence and grandeur of 18th-century style. Their work evokes the extravagance of that bygone era, captivating fashion enthusiasts with its lavish aesthetic.

Ornate Detailing Revival

Lavish embroidery and brocade have made a striking comeback in contemporary fashion collections, echoing the opulence of Baroque and Rococo eras . Designers like Alexander McQueen and Valentino have embraced ornate detailing , bringing intricate embroidery and gilded brocade to the forefront of their designs. This revival isn't just about aesthetics; it's a nod to the past reimagined for today's avant-garde audience.

Marchesa and Zuhair Murad often create opulent silhouettes and voluminous gowns, adorned with decorative trimmings and ruffles . These pieces captivate with their grandeur, reminiscent of 18th-century extravagance . The richness of their creations is undeniable, each piece a tribute to the era's influence.

Dolce & Gabbana and Christian Dior infuse their collections with jewel-toned colors and elaborate headpieces , a clear homage to Rococo's gilded splendor . The dramatic flair of these elements speaks to modern innovation while honoring historical aesthetics.

Chanel and Elie Saab's use of pastel palettes and floral motifs adds a delicate, whimsical touch, highlighting the enduring charm of Rococo details. Meanwhile, Miuccia Prada and Simone Rocha reinterpret asymmetry and sculptural silhouettes, blending Baroque pearls with a contemporary twist. This blend of old and new breathes life into fashion's ever-evolving narrative.

Luxurious Fabric Choices

Modern fashion designers have a renewed fascination with luxurious fabrics like silk, satin, and velvet. These textiles were once associated with the extravagance of French royal courts under Louis XIV and XV, and they continue to define contemporary styles, blending the past with modern creativity.

Today's designs often feature soft pastel hues and intricate lace embellishments, evoking the delicate artistry of 18th-century fashion. Lace, a signature fabric of the era, adds a delicate touch to modern garments. Designers also incorporate gold and silver threads, reminiscent of the shimmering metallic accents that once adorned the gowns of French aristocracy.

Embroidery and floral motifs reflect the natural, organic elements celebrated in Rococo aesthetics. The elaborate, ornamental designs of the past inspire the detailed patterns and embroidery that adorn contemporary collections. This revival of luxurious fabric choices not only pays homage to historical fashion but also pushes the boundaries of modern style, creating a dialogue between the elegance of the past and the innovation of the present.

Contemporary Fashion Trends

Contemporary fashion trends are a captivating blend of old and new. Drawing inspiration from the lavish Baroque and Rococo eras, today's designers seamlessly merge ornate details with a modern sensibility. In women's fashion, the influences of Marie Antoinette and the Rococo period are undeniable. Renowned labels like Versace, Dolce & Gabbana , and Valentino have revived the maximalist fashion ethos, emphasizing opulence through bold prints, gilded fabrics , and intricate embroidery.

While fashion has evolved, the desire for extravagance remains. Modern collections feature ornate accessories reminiscent of 18th-century aristocracy, from lavish brooches to elaborate necklaces. The Rococo's pastel palette and theatrical silhouettes are evident on runways, where contemporary gowns often mirror the grandeur of the past.

Celebrities and influencers have embraced this resurgence, turning heads with dramatic gowns and towering hairstyles that evoke the spirit of Marie Antoinette. Their choices highlight the enduring allure of Baroque and Rococo aesthetics, which have become a vibrant part of today's fashion narrative.

This fascination extends beyond clothing, as designers in the world of interior design also incorporate Baroque and Rococo-inspired elements, such as curlicue patterns and opulent textiles. The blend of old-world charm with modern flair continues to captivate audiences, proving that the legacy of these eras is not merely a relic but a living, evolving part of the fashion landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the rococo style continue to influence modern art, design, and architecture?.

The Rococo style's playful themes and opulent aesthetics continue to influence modern art, design, and architecture. Its impact is evident in high-end products, lavish interiors, and the visual language seen across various media today. The Rococo's whimsical and extravagant qualities resonate with contemporary tastes, shaping the look and feel of luxury brands, upscale home decor, and the vivid imagery prevalent in today's visual landscape.

How Did Rococo Influence Fashion?

Rococo's playful elegance has left an indelible mark on fashion. The pastel hues, delicate fabrics, and intricate details from this artistic movement continue to influence contemporary designs, giving our clothes a sense of luxurious whimsy.

Today's fashion trends often reflect the lighthearted spirit of Rococo. Designers draw inspiration from the era's ornate embellishments and soft, romantic color palettes, creating garments that feel both sophisticated and charmingly expressive.

The Rococo style's emphasis on opulence and fantasy has resonated with modern consumers seeking to infuse their wardrobes with a touch of dreamlike allure. Designers skillfully incorporate Rococo-inspired motifs, textures, and silhouettes, allowing fashion enthusiasts to channel the period's elegant playfulness.

As fashions evolve, the enduring impact of Rococo remains evident, with its timeless aesthetic continuing to captivate and inspire the industry.

What Is the Legacy of Rococo Art Style?

Rococo's lasting impact can be seen in contemporary design's fascination with intricate details, pastel hues, and luxurious finishes. This playful yet elegant style continues to inspire modern creatives, who blend its artistic flair with fresh perspectives. The rococo aesthetic has become a touchstone, allowing designers to honor the past while pushing the boundaries of innovation. Its whimsical and extravagant nature has left an indelible mark on the world of art and design, proving that sometimes, a little playfulness can go a long way.

What Is the Significance of Baroque and Rococo?

The Baroque and Rococo eras have had a lasting impact on fashion and design. Even today, over half of high-end fashion collections draw inspiration from these historic periods. Their opulent and whimsical aesthetics continue to shape innovative design, blending the past with contemporary sensibilities.

The Baroque period, known for its grandiose and ornate style, has left an indelible mark on the world of fashion. From the elaborate embroidery and rich fabrics to the dramatic silhouettes, designers constantly revisit this era for creative inspiration. Similarly, the Rococo style, with its playful curves, pastel colors, and delicate ornamentation, has been a recurring influence in modern haute couture.

These historic design movements have stood the test of time, transcending their eras to infuse a sense of timeless elegance and extravagance into contemporary fashion. Designers skillfully reinterpret the visual language of Baroque and Rococo, seamlessly integrating it with modern sensibilities to create pieces that captivate and inspire.

Baroque and Rococo fashion's legacy is like a rich tapestry , where threads of the past and present intertwine. Modern designers don't just copy – they dance with history, blending opulence and contemporary flair . This interplay creates collections that are timeless yet current . It's clear that in fashion, old masterpieces can inspire new art, bridging centuries with each stitch and flourish.

Designers today take inspiration from the grandeur of Baroque and Rococo styles , but they reinterpret these influences to suit modern sensibilities. The result is a captivating fusion of the old and the new, where the lavish ornamentation of the past meets sleek, streamlined silhouettes. This symbiosis allows fashion to evolve while still respecting its roots.

The enduring impact of Baroque and Rococo aesthetics is a testament to their timeless allure. Designers continue to find new ways to incorporate these historic styles, ensuring that the essence of past eras lives on in contemporary creations. Fashion, like art, is a continuum – a tapestry that weaves together the threads of the past, present, and future.

Related Posts

Baroque Fashion Opulence

Rococo Fashion Elegance

Get the newsletter.

Don’t miss out! Sign up for our newsletter and receive any new articles we write or learn about new fashion rabbit holes that we go down.

Copyright @ 2024 Timeless Fashion Hub. All Right Reserved.

Quick links.

- Fashion History

- Modern Fashion Evolution

- Special Topics in Fashion

- Resources and Engagement

Contact Information

- 3550 Kingsway, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- [email protected]