Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.3 Research Design in Sociology

Learning objective.

- List the major advantages and disadvantages of surveys, experiments, and observational studies.

We now turn to the major methods that sociologists use to gather the information they analyze in their research. Table 2.2 “Major Sociological Research Methods” summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of each method.

Table 2.2 Major Sociological Research Methods

Types of Sociological Research

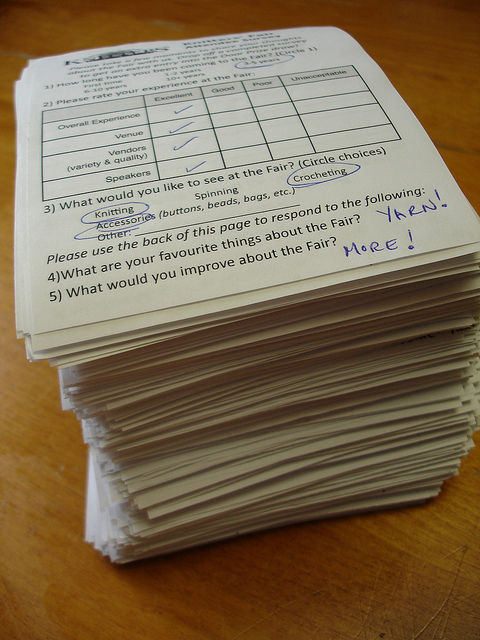

The survey is the most common method by which sociologists gather their data. The Gallup Poll is perhaps the best-known example of a survey and, like all surveys, gathers its data with the help of a questionnaire that is given to a group of respondents. The Gallup Poll is an example of a survey conducted by a private organization, but it typically includes only a small range of variables. It thus provides a good starting point for research but usually does not include enough variables for a full-fledged sociological study. Sociologists often do their own surveys, as does the government and many organizations in addition to Gallup.

The survey is the most common research design in sociological research. Respondents either fill out questionnaires themselves or provide verbal answers to interviewers asking them the questions.

The Bees – Surveys to compile – CC BY-NC 2.0.

The General Social Survey, described earlier, is an example of a face-to-face survey, in which interviewers meet with respondents to ask them questions. This type of survey can yield a lot of information, because interviewers typically will spend at least an hour asking their questions, and a high response rate (the percentage of all people in the sample who agree to be interviewed), which is important to be able to generalize the survey’s results to the entire population. On the downside, this type of survey can be very expensive and time-consuming to conduct.

Because of these drawbacks, sociologists and other researchers have turned to telephone surveys. Most Gallup Polls are conducted over the telephone. Computers do random-digit dialing, which results in a random sample of all telephone numbers being selected. Although the response rate and the number of questions asked are both lower than in face-to-face surveys (people can just hang up the phone at the outset or let their answering machine take the call), the ease and low expense of telephone surveys are making them increasingly popular.

Mailed surveys, done by mailing questionnaires to respondents, are still used, but not as often as before. Compared with face-to-face surveys, mailed questionnaires are less expensive and time consuming but have lower response rates, because many people simply throw out the questionnaire along with other junk mail.

Whereas mailed surveys are becoming less popular, surveys done over the Internet are becoming more popular, as they can reach many people at very low expense. A major problem with Web surveys is that their results cannot necessarily be generalized to the entire population, because not everyone has access to the Internet.

Experiments

Experiments are the primary form of research in the natural and physical sciences, but in the social sciences they are for the most part found only in psychology. Some sociologists still use experiments, however, and they remain a powerful tool of social research.

The major advantage of experiments is that the researcher can be fairly sure of a cause-and-effect relationship because of the way the experiment is set up. Although many different experimental designs exist, the typical experiment consists of an experimental group and a control group , with subjects randomly assigned to either group. The researcher makes a change to the experimental group that is not made to the control group. If the two groups differ later in some variable, then it is safe to say that the condition to which the experimental group was subjected was responsible for the difference that resulted.

Experiments are very common in the natural and physical sciences and in sociology. A major advantage of experiments is that they are very useful for establishing cause-and-effect-relationships.

biologycorner – Science Experiment – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Most experiments take place in the laboratory, which for psychologists may be a room with a one-way mirror, but some experiments occur in “the field,” or in a natural setting. In Minneapolis, Minnesota, in the early 1980s, sociologists were involved in a much-discussed field experiment sponsored by the federal government. The researchers wanted to see whether arresting men for domestic violence made it less likely that they would commit such violence again. To test this hypothesis, the researchers had police do one of the following after arriving at the scene of a domestic dispute: they either arrested the suspect, separated him from his wife or partner for several hours, or warned him to stop but did not arrest or separate him. The researchers then determined the percentage of men in each group who committed repeated domestic violence during the next 6 months and found that those who were arrested had the lowest rate of recidivism, or repeat offending (Sherman & Berk, 1984). This finding led many jurisdictions across the United States to adopt a policy of mandatory arrest for domestic violence suspects. However, replications of the Minneapolis experiment in other cities found that arrest sometimes reduced recidivism for domestic violence but also sometimes increased it, depending on which city was being studied and on certain characteristics of the suspects, including whether they were employed at the time of their arrest (Sherman, 1992).

As the Minneapolis study suggests, perhaps the most important problem with experiments is that their results are not generalizable beyond the specific subjects studied. The subjects in most psychology experiments, for example, are college students, who are not typical of average Americans: they are younger, more educated, and more likely to be middle class. Despite this problem, experiments in psychology and other social sciences have given us very valuable insights into the sources of attitudes and behavior.

Observational Studies and Intensive Interviewing

Observational research, also called field research, is a staple of sociology. Sociologists have long gone into the field to observe people and social settings, and the result has been many rich descriptions and analyses of behavior in juvenile gangs, bars, urban street corners, and even whole communities.

Observational studies consist of both participant observation and nonparticipant observation . Their names describe how they differ. In participant observation, the researcher is part of the group that she or he is studying. The researcher thus spends time with the group and might even live with them for a while. Several classical sociological studies of this type exist, many of them involving people in urban neighborhoods (Liebow, 1967, 1993; Whyte, 1943). Participant researchers must try not to let their presence influence the attitudes or behavior of the people they are observing. In nonparticipant observation, the researcher observes a group of people but does not otherwise interact with them. If you went to your local shopping mall to observe, say, whether people walking with children looked happier than people without children, you would be engaging in nonparticipant observation.

A related type of research design is intensive interviewing . Here a researcher does not necessarily observe a group of people in their natural setting but rather sits down with them individually and interviews them at great length, often for one or two hours or even longer. The researcher typically records the interview and later transcribes it for analysis. The advantages and disadvantages of intensive interviewing are similar to those for observational studies: intensive interviewing provides much information about the subjects being interviewed, but the results of such interviewing cannot necessarily be generalized beyond the subjects.

A classic example of field research is Kai T. Erikson’s Everything in Its Path (1976), a study of the loss of community bonds in the aftermath of a flood in a West Virginia mining community, Buffalo Creek. The flood occurred when an artificial dam composed of mine waste gave way after days of torrential rain. The local mining company had allowed the dam to build up in violation of federal law. When it broke, 132 million gallons of water broke through and destroyed several thousand homes in seconds while killing 125 people. Some 2,500 other people were rendered instantly homeless. Erikson was called in by the lawyers representing the survivors to document the sociological effects of their loss of community, and the book he wrote remains a moving account of how the destruction of the Buffalo Creek way of life profoundly affected the daily lives of its residents.

Intensive interviewing can yield in-depth information about the subjects who are interviewed, but the results of this research design cannot necessarily be generalized beyond these subjects.

Fellowship of the Rich – Interview – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Similar to experiments, observational studies cannot automatically be generalized to other settings or members of the population. But in many ways they provide a richer account of people’s lives than surveys do, and they remain an important method of sociological research.

Existing Data

Sometimes sociologists do not gather their own data but instead analyze existing data that someone else has gathered. The U.S. Census Bureau, for example, gathers data on all kinds of areas relevant to the lives of Americans, and many sociologists analyze census data on such topics as poverty, employment, and illness. Sociologists interested in crime and the legal system may analyze data from court records, while medical sociologists often analyze data from patient records at hospitals. Analysis of existing data such as these is called secondary data analysis . Its advantage to sociologists is that someone else has already spent the time and money to gather the data. A disadvantage is that the data set being analyzed may not contain data on all the variables in which a sociologist may be interested or may contain data on variables that are not measured in ways the sociologist might prefer.

Nonprofit organizations often analyze existing data, usually gathered by government agencies, to get a better understanding of the social issue with which an organization is most concerned. They then use their analysis to help devise effective social policies and strategies for dealing with the issue. The “Learning From Other Societies” box discusses a nonprofit organization in Canada that analyzes existing data for this purpose.

Learning From Other Societies

Social Research and Social Policy in Canada

In several nations beyond the United States, nonprofit organizations often use social science research, including sociological research, to develop and evaluate various social reform strategies and social policies. Canada is one of these nations. Information on Canadian social research organizations can be found at http://www.canadiansocialresearch.net/index.htm .

The Canadian Research Institute for Social Policy (CRISP) at the University of New Brunswick is one of these organizations. According to its Web site ( http://www.unb.ca/crisp/index.php ), CRISP is “dedicated to conducting policy research aimed at improving the education and care of Canadian children and youth…and supporting low-income countries in their efforts to build research capacity in child development.” To do this, CRISP analyzes data from large data sets, such as the Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth, and it also evaluates policy efforts at the local, national, and international levels.

A major concern of CRISP has been developmental problems in low-income children and teens. These problems are the focus of a CRISP project called Raising and Leveling the Bar: A Collaborative Research Initiative on Children’s Learning, Behavioral, and Health Outcomes. This project at the time of this writing involved a team of five senior researchers and almost two dozen younger scholars. CRISP notes that Canada may have the most complete data on child development in the world but that much more research with these data needs to be performed to help inform public policy in the area of child development. CRISP’s project aims to use these data to help achieve the following goals, as listed on its Web site: (a) safeguard the healthy development of infants, (b) strengthen early childhood education, (c) improve schools and local communities, (d) reduce socioeconomic segregation and the effects of poverty, and (e) create a family enabling society ( http://www.unb.ca/crisp/rlb.html ). This project has written many policy briefs, journal articles, and popular press articles to educate varied audiences about what the data on children’s development suggest for child policy in Canada.

Key Takeaways

- The major types of sociological research include surveys, experiments, observational studies, and the use of existing data.

- Surveys are very common and allow for the gathering of much information on respondents that is relatively superficial. The results of surveys that use random samples can be generalized to the population that the sample represents.

- Observational studies are also very common and enable in-depth knowledge of a small group of people. Because the samples of these studies are not random, the results cannot necessarily be generalized to a population.

- Experiments are much less common in sociology than in psychology. When field experiments are conducted in sociology, they can yield valuable information because of their experimental design.

For Your Review

- Write a brief essay in which you outline the various kinds of surveys and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each type.

- Suppose you wanted to study whether gender affects happiness. Write a brief essay that describes how you would do this either with a survey or with an observational study.

Erikson, K. T. (1976). Everything in its path: Destruction of community in the Buffalo Creek flood . New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Liebow, E. (1967). Tally’s corner . Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Liebow, E. (1993). Tell them who I am: The lives of homeless women . New York, NY: Free Press.

Sherman, L W. (1992). Policing domestic violence: Experiments and dilemmas . New York, NY: Free Press.

Sherman, L. W., & Berk, R. A. (1984). The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. American Sociological Review, 49 , 261–272.

Whyte, W. F. (1943). Street corner society: The social structure of an Italian slum . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

2. Sociological Research

Research methods, learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Differentiate between four kinds of research methods: surveys, field research, experiments, and secondary data analysis

- Understand why different topics are better suited to different research approaches

Sociologists examine the world, see a problem or interesting pattern, and set out to study it. They use research methods to design a study—perhaps a detailed, systematic, scientific method for conducting research and obtaining data, or perhaps an ethnographic study utilizing an interpretive framework. Planning the research design is a key step in any sociological study.

When entering a particular social environment, a researcher must be careful. There are times to remain anonymous and times to be overt. There are times to conduct interviews and times to simply observe. Some participants need to be thoroughly informed; others should not know they are being observed. A researcher wouldn’t stroll into a crime-ridden neighborhood at midnight, calling out, “Any gang members around?” And if a researcher walked into a coffee shop and told the employees they would be observed as part of a study on work efficiency, the self-conscious, intimidated baristas might not behave naturally. This is called the Hawthorne effect —where people change their behavior because they know they are being watched as part of a study. The Hawthorne effect is unavoidable in some research. In many cases, sociologists have to make the purpose of the study known. Subjects must be aware that they are being observed, and a certain amount of artificiality may result (Sonnenfeld 1985).

Making sociologists’ presence invisible is not always realistic for other reasons. That option is not available to a researcher studying prison behaviors, early education, or the Ku Klux Klan. Researchers can’t just stroll into prisons, kindergarten classrooms, or Klan meetings and unobtrusively observe behaviors. In situations like these, other methods are needed. All studies shape the research design, while research design simultaneously shapes the study. Researchers choose methods that best suit their study topics and that fit with their overall approaches to research.

In planning studies’ designs, sociologists generally choose from four widely used methods of social investigation: survey, field research, experiment, and secondary data analysis , or use of existing sources. Every research method comes with plusses and minuses, and the topic of study strongly influences which method or methods are put to use.

As a research method, a survey collects data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire. The survey is one of the most widely used scientific research methods. The standard survey format allows individuals a level of anonymity in which they can express personal ideas.

Questionnaires are a common research method; the U.S. Census is a well-known example. (Photo courtesy of Kathryn Decker/flickr)

At some point, most people in the United States respond to some type of survey. The U.S. Census is an excellent example of a large-scale survey intended to gather sociological data. Not all surveys are considered sociological research, however, and many surveys people commonly encounter focus on identifying marketing needs and strategies rather than testing a hypothesis or contributing to social science knowledge. Questions such as, “How many hot dogs do you eat in a month?” or “Were the staff helpful?” are not usually designed as scientific research. Often, polls on television do not reflect a general population, but are merely answers from a specific show’s audience. Polls conducted by programs such as American Idol or So You Think You Can Dance represent the opinions of fans but are not particularly scientific. A good contrast to these are the Nielsen Ratings, which determine the popularity of television programming through scientific market research.

American Idol uses a real-time survey system—with numbers—that allows members in the audience to vote on contestants. (Photo courtesy of Sam Howzit/flickr)

Sociologists conduct surveys under controlled conditions for specific purposes. Surveys gather different types of information from people. While surveys are not great at capturing the ways people really behave in social situations, they are a great method for discovering how people feel and think—or at least how they say they feel and think. Surveys can track preferences for presidential candidates or reported individual behaviors (such as sleeping, driving, or texting habits) or factual information such as employment status, income, and education levels.

A survey targets a specific population , people who are the focus of a study, such as college athletes, international students, or teenagers living with type 1 (juvenile-onset) diabetes. Most researchers choose to survey a small sector of the population, or a sample: that is, a manageable number of subjects who represent a larger population. The success of a study depends on how well a population is represented by the sample. In a random sample , every person in a population has the same chance of being chosen for the study. According to the laws of probability, random samples represent the population as a whole. For instance, a Gallup Poll, if conducted as a nationwide random sampling, should be able to provide an accurate estimate of public opinion whether it contacts 2,000 or 10,000 people.

After selecting subjects, the researcher develops a specific plan to ask questions and record responses. It is important to inform subjects of the nature and purpose of the study up front. If they agree to participate, researchers thank subjects and offer them a chance to see the results of the study if they are interested. The researcher presents the subjects with an instrument, which is a means of gathering the information. A common instrument is a questionnaire, in which subjects answer a series of questions. For some topics, the researcher might ask yes-or-no or multiple-choice questions, allowing subjects to choose possible responses to each question. This kind of quantitative data —research collected in numerical form that can be counted—are easy to tabulate. Just count up the number of “yes” and “no” responses or correct answers, and chart them into percentages.

Questionnaires can also ask more complex questions with more complex answers—beyond “yes,” “no,” or the option next to a checkbox. In those cases, the answers are subjective and vary from person to person. How do plan to use your college education? Why do you follow Jimmy Buffett around the country and attend every concert? Those types of questions require short essay responses, and participants willing to take the time to write those answers will convey personal information about religious beliefs, political views, and morals. Some topics that reflect internal thought are impossible to observe directly and are difficult to discuss honestly in a public forum. People are more likely to share honest answers if they can respond to questions anonymously. This type of information is qualitative data —results that are subjective and often based on what is seen in a natural setting. Qualitative information is harder to organize and tabulate. The researcher will end up with a wide range of responses, some of which may be surprising. The benefit of written opinions, though, is the wealth of material that they provide.

An interview is a one-on-one conversation between the researcher and the subject, and it is a way of conducting surveys on a topic. Interviews are similar to the short-answer questions on surveys in that the researcher asks subjects a series of questions. However, participants are free to respond as they wish, without being limited by predetermined choices. In the back-and-forth conversation of an interview, a researcher can ask for clarification, spend more time on a subtopic, or ask additional questions. In an interview, a subject will ideally feel free to open up and answer questions that are often complex. There are no right or wrong answers. The subject might not even know how to answer the questions honestly.

Questions such as, “How did society’s view of alcohol consumption influence your decision whether or not to take your first sip of alcohol?” or “Did you feel that the divorce of your parents would put a social stigma on your family?” involve so many factors that the answers are difficult to categorize. A researcher needs to avoid steering or prompting the subject to respond in a specific way; otherwise, the results will prove to be unreliable. And, obviously, a sociological interview is not an interrogation. The researcher will benefit from gaining a subject’s trust, from empathizing or commiserating with a subject, and from listening without judgment.

Field Research

The work of sociology rarely happens in limited, confined spaces. Sociologists seldom study subjects in their own offices or laboratories. Rather, sociologists go out into the world. They meet subjects where they live, work, and play. Field research refers to gathering primary data from a natural environment without doing a lab experiment or a survey. It is a research method suited to an interpretive framework rather than to the scientific method. To conduct field research, the sociologist must be willing to step into new environments and observe, participate, or experience those worlds. In field work, the sociologists, rather than the subjects, are the ones out of their element.

The researcher interacts with or observes a person or people and gathers data along the way. The key point in field research is that it takes place in the subject’s natural environment, whether it’s a coffee shop or tribal village, a homeless shelter or the DMV, a hospital, airport, mall, or beach resort.

Sociological researchers travel across countries and cultures to interact with and observe subjects in their natural environments. (Photo courtesy of IMLS Digital Collections and Content/flickr and Olympic National Park)

While field research often begins in a specific setting , the study’s purpose is to observe specific behaviors in that setting. Field work is optimal for observing how people behave. It is less useful, however, for understanding why they behave that way. You can’t really narrow down cause and effect when there are so many variables floating around in a natural environment.

Much of the data gathered in field research are based not on cause and effect but on correlation . And while field research looks for correlation, its small sample size does not allow for establishing a causal relationship between two variables.

Parrotheads as Sociological Subjects

Business suits for the day job are replaced by leis and T-shirts for a Jimmy Buffett concert. (Photo courtesy of Sam Howzitt/flickr)

Some sociologists study small groups of people who share an identity in one aspect of their lives. Almost everyone belongs to a group of like-minded people who share an interest or hobby. Scientologists, folk dancers, or members of Mensa (an organization for people with exceptionally high IQs) express a specific part of their identity through their affiliation with a group. Those groups are often of great interest to sociologists.

Jimmy Buffett, an American musician who built a career from his single top-10 song “Margaritaville,” has a following of devoted groupies called Parrotheads. Some of them have taken fandom to the extreme, making Parrothead culture a lifestyle. In 2005, Parrotheads and their subculture caught the attention of researchers John Mihelich and John Papineau. The two saw the way Jimmy Buffett fans collectively created an artificial reality. They wanted to know how fan groups shape culture.

What Mihelich and Papineau found was that Parrotheads, for the most part, do not seek to challenge or even change society, as many sub-groups do. In fact, most Parrotheads live successfully within society, holding upper-level jobs in the corporate world. What they seek is escape from the stress of daily life.

At Jimmy Buffett concerts, Parrotheads engage in a form of role play. They paint their faces and dress for the tropics in grass skirts, Hawaiian leis, and Parrot hats. These fans don’t generally play the part of Parrotheads outside of these concerts; you are not likely to see a lone Parrothead in a bank or library. In that sense, Parrothead culture is less about individualism and more about conformity. Being a Parrothead means sharing a specific identity. Parrotheads feel connected to each other: it’s a group identity, not an individual one.

In their study, Mihelich and Papineau quote from a recent book by sociologist Richard Butsch, who writes, “un-self-conscious acts, if done by many people together, can produce change, even though the change may be unintended” (2000). Many Parrothead fan groups have performed good works in the name of Jimmy Buffett culture, donating to charities and volunteering their services.

However, the authors suggest that what really drives Parrothead culture is commercialism. Jimmy Buffett’s popularity was dying out in the 1980s until being reinvigorated after he signed a sponsorship deal with a beer company. These days, his concert tours alone generate nearly $30 million a year. Buffett made a lucrative career for himself by partnering with product companies and marketing Margaritaville in the form of T-shirts, restaurants, casinos, and an expansive line of products. Some fans accuse Buffett of selling out, while others admire his financial success. Buffett makes no secret of his commercial exploitations; from the stage, he’s been known to tell his fans, “Just remember, I am spending your money foolishly.”

Mihelich and Papineau gathered much of their information online. Referring to their study as a “Web ethnography,” they collected extensive narrative material from fans who joined Parrothead clubs and posted their experiences on websites. “We do not claim to have conducted a complete ethnography of Parrothead fans, or even of the Parrothead Web activity,” state the authors, “but we focused on particular aspects of Parrothead practice as revealed through Web research” (2005). Fan narratives gave them insight into how individuals identify with Buffett’s world and how fans used popular music to cultivate personal and collective meaning.

In conducting studies about pockets of culture, most sociologists seek to discover a universal appeal. Mihelich and Papineau stated, “Although Parrotheads are a relative minority of the contemporary US population, an in-depth look at their practice and conditions illuminate [sic] cultural practices and conditions many of us experience and participate in” (2005).

Here, we will look at three types of field research: participant observation, ethnography, and the case study.

Participant Observation

In 2000, a comic writer named Rodney Rothman wanted an insider’s view of white-collar work. He slipped into the sterile, high-rise offices of a New York “dot com” agency. Every day for two weeks, he pretended to work there. His main purpose was simply to see whether anyone would notice him or challenge his presence. No one did. The receptionist greeted him. The employees smiled and said good morning. Rothman was accepted as part of the team. He even went so far as to claim a desk, inform the receptionist of his whereabouts, and attend a meeting. He published an article about his experience in The New Yorker called “My Fake Job” (2000). Later, he was discredited for allegedly fabricating some details of the story and The New Yorker issued an apology. However, Rothman’s entertaining article still offered fascinating descriptions of the inside workings of a “dot com” company and exemplified the lengths to which a sociologist will go to uncover material.

Rothman had conducted a form of study called participant observation , in which researchers join people and participate in a group’s routine activities for the purpose of observing them within that context. This method lets researchers experience a specific aspect of social life. A researcher might go to great lengths to get a firsthand look into a trend, institution, or behavior. Researchers temporarily put themselves into roles and record their observations. A researcher might work as a waitress in a diner, live as a homeless person for several weeks, or ride along with police officers as they patrol their regular beat. Often, these researchers try to blend in seamlessly with the population they study, and they may not disclose their true identity or purpose if they feel it would compromise the results of their research.

Is she a working waitress or a sociologist conducting a study using participant observation? (Photo courtesy of zoetnet/flickr)

At the beginning of a field study, researchers might have a question: “What really goes on in the kitchen of the most popular diner on campus?” or “What is it like to be homeless?” Participant observation is a useful method if the researcher wants to explore a certain environment from the inside.

Field researchers simply want to observe and learn. In such a setting, the researcher will be alert and open minded to whatever happens, recording all observations accurately. Soon, as patterns emerge, questions will become more specific, observations will lead to hypotheses, and hypotheses will guide the researcher in shaping data into results.

In a study of small towns in the United States conducted by sociological researchers John S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd, the team altered their purpose as they gathered data. They initially planned to focus their study on the role of religion in U.S. towns. As they gathered observations, they realized that the effect of industrialization and urbanization was the more relevant topic of this social group. The Lynds did not change their methods, but they revised their purpose. This shaped the structure of Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture , their published results (Lynd and Lynd 1959).

The Lynds were upfront about their mission. The townspeople of Muncie, Indiana, knew why the researchers were in their midst. But some sociologists prefer not to alert people to their presence. The main advantage of covert participant observation is that it allows the researcher access to authentic, natural behaviors of a group’s members. The challenge, however, is gaining access to a setting without disrupting the pattern of others’ behavior. Becoming an inside member of a group, organization, or subculture takes time and effort. Researchers must pretend to be something they are not. The process could involve role playing, making contacts, networking, or applying for a job.

Once inside a group, some researchers spend months or even years pretending to be one of the people they are observing. However, as observers, they cannot get too involved. They must keep their purpose in mind and apply the sociological perspective. That way, they illuminate social patterns that are often unrecognized. Because information gathered during participant observation is mostly qualitative, rather than quantitative, the end results are often descriptive or interpretive. The researcher might present findings in an article or book and describe what he or she witnessed and experienced.

This type of research is what journalist Barbara Ehrenreich conducted for her book Nickel and Dimed . One day over lunch with her editor, as the story goes, Ehrenreich mentioned an idea. How can people exist on minimum-wage work? How do low-income workers get by? she wondered. Someone should do a study. To her surprise, her editor responded, Why don’t you do it?

That’s how Ehrenreich found herself joining the ranks of the working class. For several months, she left her comfortable home and lived and worked among people who lacked, for the most part, higher education and marketable job skills. Undercover, she applied for and worked minimum wage jobs as a waitress, a cleaning woman, a nursing home aide, and a retail chain employee. During her participant observation, she used only her income from those jobs to pay for food, clothing, transportation, and shelter.

She discovered the obvious, that it’s almost impossible to get by on minimum wage work. She also experienced and observed attitudes many middle and upper-class people never think about. She witnessed firsthand the treatment of working class employees. She saw the extreme measures people take to make ends meet and to survive. She described fellow employees who held two or three jobs, worked seven days a week, lived in cars, could not pay to treat chronic health conditions, got randomly fired, submitted to drug tests, and moved in and out of homeless shelters. She brought aspects of that life to light, describing difficult working conditions and the poor treatment that low-wage workers suffer.

Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America , the book she wrote upon her return to her real life as a well-paid writer, has been widely read and used in many college classrooms.

Field research happens in real locations. What type of environment do work spaces foster? What would a sociologist discover after blending in? (Photo courtesy of drewzhrodague/flickr)

Ethnography

Ethnography is the extended observation of the social perspective and cultural values of an entire social setting. Ethnographies involve objective observation of an entire community.

The heart of an ethnographic study focuses on how subjects view their own social standing and how they understand themselves in relation to a community. An ethnographic study might observe, for example, a small U.S. fishing town, an Inuit community, a village in Thailand, a Buddhist monastery, a private boarding school, or an amusement park. These places all have borders. People live, work, study, or vacation within those borders. People are there for a certain reason and therefore behave in certain ways and respect certain cultural norms. An ethnographer would commit to spending a determined amount of time studying every aspect of the chosen place, taking in as much as possible.

A sociologist studying a tribe in the Amazon might watch the way villagers go about their daily lives and then write a paper about it. To observe a spiritual retreat center, an ethnographer might sign up for a retreat and attend as a guest for an extended stay, observe and record data, and collate the material into results.

Institutional Ethnography

Institutional ethnography is an extension of basic ethnographic research principles that focuses intentionally on everyday concrete social relationships. Developed by Canadian sociologist Dorothy E. Smith, institutional ethnography is often considered a feminist-inspired approach to social analysis and primarily considers women’s experiences within male-dominated societies and power structures. Smith’s work is seen to challenge sociology’s exclusion of women, both academically and in the study of women’s lives (Fenstermaker, n.d.).

Historically, social science research tended to objectify women and ignore their experiences except as viewed from the male perspective. Modern feminists note that describing women, and other marginalized groups, as subordinates helps those in authority maintain their own dominant positions (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, n.d.). Smith’s three major works explored what she called “the conceptual practices of power” (1990; cited in Fensternmaker, n.d.) and are still considered seminal works in feminist theory and ethnography.

The Making of Middletown: A Study in Modern U.S. Culture

In 1924, a young married couple named Robert and Helen Lynd undertook an unprecedented ethnography: to apply sociological methods to the study of one U.S. city in order to discover what “ordinary” people in the United States did and believed. Choosing Muncie, Indiana (population about 30,000), as their subject, they moved to the small town and lived there for eighteen months.

Ethnographers had been examining other cultures for decades—groups considered minority or outsider—like gangs, immigrants, and the poor. But no one had studied the so-called average American.

Recording interviews and using surveys to gather data, the Lynds did not sugarcoat or idealize U.S. life (PBS). They objectively stated what they observed. Researching existing sources, they compared Muncie in 1890 to the Muncie they observed in 1924. Most Muncie adults, they found, had grown up on farms but now lived in homes inside the city. From that discovery, the Lynds focused their study on the impact of industrialization and urbanization.

They observed that Muncie was divided into business class and working class groups. They defined business class as dealing with abstract concepts and symbols, while working class people used tools to create concrete objects. The two classes led different lives with different goals and hopes. However, the Lynds observed, mass production offered both classes the same amenities. Like wealthy families, the working class was now able to own radios, cars, washing machines, telephones, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators. This was an emerging material new reality of the 1920s.

As the Lynds worked, they divided their manuscript into six sections: Getting a Living, Making a Home, Training the Young, Using Leisure, Engaging in Religious Practices, and Engaging in Community Activities. Each chapter included subsections such as “The Long Arm of the Job” and “Why Do They Work So Hard?” in the “Getting a Living” chapter.

When the study was completed, the Lynds encountered a big problem. The Rockefeller Foundation, which had commissioned the book, claimed it was useless and refused to publish it. The Lynds asked if they could seek a publisher themselves.

Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture was not only published in 1929 but also became an instant bestseller, a status unheard of for a sociological study. The book sold out six printings in its first year of publication, and has never gone out of print (PBS).

Nothing like it had ever been done before. Middletown was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times . Readers in the 1920s and 1930s identified with the citizens of Muncie, Indiana, but they were equally fascinated by the sociological methods and the use of scientific data to define ordinary people in the United States. The book was proof that social data was important—and interesting—to the U.S. public.

A classroom in Muncie, Indiana, in 1917, five years before John and Helen Lynd began researching this “typical” U.S. community. (Photo courtesy of Don O’Brien/flickr)

Sometimes a researcher wants to study one specific person or event. A case study is an in-depth analysis of a single event, situation, or individual. To conduct a case study, a researcher examines existing sources like documents and archival records, conducts interviews, engages in direct observation and even participant observation, if possible.

Researchers might use this method to study a single case of, for example, a foster child, drug lord, cancer patient, criminal, or rape victim. However, a major criticism of the case study as a method is that a developed study of a single case, while offering depth on a topic, does not provide enough evidence to form a generalized conclusion. In other words, it is difficult to make universal claims based on just one person, since one person does not verify a pattern. This is why most sociologists do not use case studies as a primary research method.

However, case studies are useful when the single case is unique. In these instances, a single case study can add tremendous knowledge to a certain discipline. For example, a feral child, also called “wild child,” is one who grows up isolated from human beings. Feral children grow up without social contact and language, which are elements crucial to a “civilized” child’s development. These children mimic the behaviors and movements of animals, and often invent their own language. There are only about one hundred cases of “feral children” in the world.

As you may imagine, a feral child is a subject of great interest to researchers. Feral children provide unique information about child development because they have grown up outside of the parameters of “normal” child development. And since there are very few feral children, the case study is the most appropriate method for researchers to use in studying the subject.

At age three, a Ukranian girl named Oxana Malaya suffered severe parental neglect. She lived in a shed with dogs, and she ate raw meat and scraps. Five years later, a neighbor called authorities and reported seeing a girl who ran on all fours, barking. Officials brought Oxana into society, where she was cared for and taught some human behaviors, but she never became fully socialized. She has been designated as unable to support herself and now lives in a mental institution (Grice 2011). Case studies like this offer a way for sociologists to collect data that may not be collectable by any other method.

Experiments

You’ve probably tested personal social theories. “If I study at night and review in the morning, I’ll improve my retention skills.” Or, “If I stop drinking soda, I’ll feel better.” Cause and effect. If this, then that. When you test the theory, your results either prove or disprove your hypothesis.

One way researchers test social theories is by conducting an experiment , meaning they investigate relationships to test a hypothesis—a scientific approach.

There are two main types of experiments: lab-based experiments and natural or field experiments. In a lab setting, the research can be controlled so that perhaps more data can be recorded in a certain amount of time. In a natural or field-based experiment, the generation of data cannot be controlled but the information might be considered more accurate since it was collected without interference or intervention by the researcher.

As a research method, either type of sociological experiment is useful for testing if-then statements: if a particular thing happens, then another particular thing will result. To set up a lab-based experiment, sociologists create artificial situations that allow them to manipulate variables.

Classically, the sociologist selects a set of people with similar characteristics, such as age, class, race, or education. Those people are divided into two groups. One is the experimental group and the other is the control group. The experimental group is exposed to the independent variable(s) and the control group is not. To test the benefits of tutoring, for example, the sociologist might expose the experimental group of students to tutoring but not the control group. Then both groups would be tested for differences in performance to see if tutoring had an effect on the experimental group of students. As you can imagine, in a case like this, the researcher would not want to jeopardize the accomplishments of either group of students, so the setting would be somewhat artificial. The test would not be for a grade reflected on their permanent record, for example.

An Experiment in Action

Sociologist Frances Heussenstamm conducted an experiment to explore the correlation between traffic stops and race-based bumper stickers. This issue of racial profiling remains a hot-button topic today. (Photo courtesy of dwightsghost/flickr)

A real-life example will help illustrate the experiment process. In 1971, Frances Heussenstamm, a sociology professor at California State University at Los Angeles, had a theory about police prejudice. To test her theory she conducted an experiment. She chose fifteen students from three ethnic backgrounds: black, white, and Hispanic. She chose students who routinely drove to and from campus along Los Angeles freeway routes, and who’d had perfect driving records for longer than a year. Those were her independent variables—students, good driving records, same commute route.

Next, she placed a Black Panther bumper sticker on each car. That sticker, a representation of a social value, was the independent variable. In the 1970s, the Black Panthers were a revolutionary group actively fighting racism. Heussenstamm asked the students to follow their normal driving patterns. She wanted to see whether seeming support of the Black Panthers would change how these good drivers were treated by the police patrolling the highways.

The first arrest, for an incorrect lane change, was made two hours after the experiment began. One participant was pulled over three times in three days. He quit the study. After seventeen days, the fifteen drivers had collected a total of thirty-three traffic citations. The experiment was halted. The funding to pay traffic fines had run out, and so had the enthusiasm of the participants (Heussenstamm 1971).

Secondary Data Analysis

While sociologists often engage in original research studies, they also contribute knowledge to the discipline through secondary data analysis. Secondary data don’t result from firsthand research collected from primary sources, but are the already completed work of other researchers. Sociologists might study works written by historians, economists, teachers, or early sociologists. They might search through periodicals, newspapers, or magazines from any period in history.

Using available information not only saves time and money but can also add depth to a study. Sociologists often interpret findings in a new way, a way that was not part of an author’s original purpose or intention. To study how women were encouraged to act and behave in the 1960s, for example, a researcher might watch movies, televisions shows, and situation comedies from that period. Or to research changes in behavior and attitudes due to the emergence of television in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a sociologist would rely on new interpretations of secondary data. Decades from now, researchers will most likely conduct similar studies on the advent of mobile phones, the Internet, or Facebook.

Social scientists also learn by analyzing the research of a variety of agencies. Governmental departments and global groups, like the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics or the World Health Organization, publish studies with findings that are useful to sociologists. A public statistic like the foreclosure rate might be useful for studying the effects of the 2008 recession; a racial demographic profile might be compared with data on education funding to examine the resources accessible by different groups.

One of the advantages of secondary data is that it is nonreactive research (or unobtrusive research), meaning that it does not include direct contact with subjects and will not alter or influence people’s behaviors. Unlike studies requiring direct contact with people, using previously published data doesn’t require entering a population and the investment and risks inherent in that research process.

Using available data does have its challenges. Public records are not always easy to access. A researcher will need to do some legwork to track them down and gain access to records. To guide the search through a vast library of materials and avoid wasting time reading unrelated sources, sociologists employ content analysis , applying a systematic approach to record and value information gleaned from secondary data as they relate to the study at hand.

But, in some cases, there is no way to verify the accuracy of existing data. It is easy to count how many drunk drivers, for example, are pulled over by the police. But how many are not? While it’s possible to discover the percentage of teenage students who drop out of high school, it might be more challenging to determine the number who return to school or get their GED later.

Another problem arises when data are unavailable in the exact form needed or do not include the precise angle the researcher seeks. For example, the average salaries paid to professors at a public school is public record. But the separate figures don’t necessarily reveal how long it took each professor to reach the salary range, what their educational backgrounds are, or how long they’ve been teaching.

When conducting content analysis, it is important to consider the date of publication of an existing source and to take into account attitudes and common cultural ideals that may have influenced the research. For example, Robert S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd gathered research for their book Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture in the 1920s. Attitudes and cultural norms were vastly different then than they are now. Beliefs about gender roles, race, education, and work have changed significantly since then. At the time, the study’s purpose was to reveal the truth about small U.S. communities. Today, it is an illustration of 1920s’ attitudes and values.

Sociological research is a fairly complex process. As you can see, a lot goes into even a simple research design. There are many steps and much to consider when collecting data on human behavior, as well as in interpreting and analyzing data in order to form conclusive results. Sociologists use scientific methods for good reason. The scientific method provides a system of organization that helps researchers plan and conduct the study while ensuring that data and results are reliable, valid, and objective.

The many methods available to researchers—including experiments, surveys, field studies, and secondary data analysis—all come with advantages and disadvantages. The strength of a study can depend on the choice and implementation of the appropriate method of gathering research. Depending on the topic, a study might use a single method or a combination of methods. It is important to plan a research design before undertaking a study. The information gathered may in itself be surprising, and the study design should provide a solid framework in which to analyze predicted and unpredicted data.

https://www.openassessments.org/assessments/1106

Short Answer Questions

- What type of data do surveys gather? For what topics would surveys be the best research method? What drawbacks might you expect to encounter when using a survey? To explore further, ask a research question and write a hypothesis. Then create a survey of about six questions relevant to the topic. Provide a rationale for each question. Now define your population and create a plan for recruiting a random sample and administering the survey.

- Imagine you are about to do field research in a specific place for a set time. Instead of thinking about the topic of study itself, consider how you, as the researcher, will have to prepare for the study. What personal, social, and physical sacrifices will you have to make? How will you manage your personal effects? What organizational equipment and systems will you need to collect the data?

- Create a brief research design about a topic in which you are passionately interested. Now write a letter to a philanthropic or grant organization requesting funding for your study. How can you describe the project in a convincing yet realistic and objective way? Explain how the results of your study will be a relevant contribution to the body of sociological work already in existence.

Further Research

For information on current real-world sociology experiments, visit: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/Sociology-Experiments

Butsch, Richard. 2000. The Making of American Audiences: From Stage to Television, 1750–1990 . Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Caplow, Theodore, Louis Hicks, and Ben Wattenberg. 2000. “The First Measured Century: Middletown.” The First Measured Century . PBS. Retrieved February 23, 2012 ( http://www.pbs.org/fmc/index.htm ).

Durkheim, Émile. 1966 [1897]. Suicide . New York: Free Press.

Fenstermaker, Sarah. n.d. “Dorothy E. Smith Award Statement” American Sociological Association . Retrieved October 19, 2014 ( http://www.asanet.org/about/awards/duboiscareer/smith.cfm ).

Franke, Richard, and James Kaul. 1978. “The Hawthorne Experiments: First Statistical Interpretation.” American Sociological Review 43(5):632–643.

Grice, Elizabeth. “Cry of an Enfant Sauvage.” The Telegraph . Retrieved July 20, 2011 ( http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/3653890/Cry-of-an-enfant-sauvage.html ).

Heussenstamm, Frances K. 1971. “Bumper Stickers and Cops” Trans-action: Social Science and Modern Society 4:32–33.

Igo, Sarah E. 2008. The Averaged American: Surveys, Citizens, and the Making of a Mass Public . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lynd, Robert S., and Helen Merrell Lynd. 1959. Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture . San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Javanovich.

Lynd, Staughton. 2005. “Making Middleton.” Indiana Magazine of History 101(3):226–238.

Mihelich, John, and John Papineau. Aug 2005. “Parrotheads in Margaritaville: Fan Practice, Oppositional Culture, and Embedded Cultural Resistance in Buffett Fandom.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 17(2):175–202.

Pew Research Center. 2014. “Ebola Worries Rise, But Most Are ‘Fairly’ Confident in Government, Hospitals to Deal with Disease: Broad Support for U.S. Efforts to Deal with Ebola in West Africa.” Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, October 21. Retrieved October 25, 2014 ( http://www.people-press.org/2014/10/21/ebola-worries-rise-but-most-are-fairly-confident-in-government-hospitals-to-deal-with-disease/ ).

Rothman, Rodney. 2000. “My Fake Job.” Pp. 120 in The New Yorker , November 27.

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. n.d. “Institutional Ethnography.” Retrieved October 19, 2014 ( http://web.uvic.ca/~mariecam/kgSite/institutionalEthnography.html ).

Sonnenfeld, Jeffery A. 1985. “Shedding Light on the Hawthorne Studies.” Journal of Occupational Behavior 6:125.

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Sociology 2e. Authored by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d/Introduction_to_Sociology_2e . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

Research Methods in Sociology – An Introduction

Table of Contents

Last Updated on May 4, 2023 by Karl Thompson

An introduction to research methods in Sociology covering quantitative, qualitative, primary and secondary data and defining the basic types of research method including social surveys, experiments, interviews, participant observation, ethnography and longitudinal studies.

Why do social research?

The simple answer is that without it, our knowledge of the social world is limited to our immediate and limited life-experiences. Without some kind of systematic research, we cannot know the answer to even basic questions such as how many people live in the United Kingdom, let alone the answers to more complex questions about why working class children get worse results at school or why the crime rate has been falling every year since 1995.

So the most basic reason for doing social research is to describe the social world around us: To find out what people think and feel about social issues and how these thoughts and feelings vary across social groups and regions. Without research, you simply do not know with any degree of certainty, what is going on in the world.

However, most research has the aim of going beyond mere description. Sociologists typically limit themselves to a specific research topic and conduct research in order to achieve a research aim or sometimes to answer a specific question.

Subjective and Objective Knowledge in Social Research

Research in Sociology is usually carefully planned, and conducted using well established procedures to ensure that knowledge is objective – where the information gathered reflects what is really ‘out there’ in the social, world rather than ‘subjective’ – where it only reflects the narrow opinions of the researchers. The careful, systematic and rigorous use of research methods is what makes sociological knowledge ‘objective’ rather than ‘subjective’.

Subjective knowledge – is knowledge based purely on the opinions of the individual, reflecting their values and biases, their point of view

Objective knowledge – is knowledge which is free of the biases, opinions and values of the researcher, it reflects what is really ‘out there’ in the social world.

While most Sociologists believe that we should strive to make our data collection as objective as possible, there are some Sociologists (known as Phenomenologists) who argue that it is not actually possible to collect data which is purely objective – The researcher’s opinions always get in the way of what data is collected and filtered for publication.

Sources and types of data

In social research, it is usual to distinguish between primary and secondary data and qualitative and quantitative data

Quantitative data refers to information that appears in numerical form, or in the form of statistics.

Qualitative data refers to information that appears in written, visual or audio form, such as transcripts of interviews, newspapers and web sites. (It is possible to analyse qualitative data and display features of it numerically!)

Secondary data is data that has been collected by previous researchers or organisations such as the government. Quantitative sources of secondary data include official government statistics and qualitative sources are very numerous including government reports, newspapers, personal documents such as diaries as well as the staggering amount of audio-visual content available online.

Primary data is data collected first hand by the researcher herself. If a sociologist is conducting her own unique sociological research, she will normally have specific research questions she wants answered and thus tailor her research methods to get the data she wants. The main methods sociologists use to generate primary data include social surveys (normally using questionnaire), interviews, experiments and observations.

Four main primary research methods

For the purposes of A-level sociology there are four major primary research methods

- social surveys (typically questionnaires)

- experiments

- participant observation

I have also included in this section longitudinal studies and ethnographies/ case studies.

Social Surveys

Social Surveys – are typically structured questionnaires designed to collect information from large numbers of people in standardised form.

Social Surveys are written in advance by the researcher and tend to to be pre-coded and have a limited number of closed-questions and they tend to focus on relatively simple topics. A good example is the UK National Census. Social Surveys can be administered (carried out) in a number of different ways – they might be self-completion (completed by the respondents themselves) or they might take the form of a structured interview on the high street, as is the case with some market research.

Experiments

Experiments – aim to measure as precisely as possible the effect which one variable has on another, aiming to establish cause and effect relationships between variables.

Experiments typically start off with a hypothesis – a theory or explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation, and will typically take the form of a testable statement about the effect which one or more independent variables will have on the dependent variable. A good experiment will be designed in such a way that objective cause and effect relationships can be established, so that the original hypothesis can verified, or rejected and modified.

There are two types of experiment – laboratory and field experiments – A laboratory experiment takes place in a controlled environment, such as a laboratory, whereas a field experiment takes place in a real-life setting such as a classroom, the work place or even the high street.

Interviews – A method of gathering information by asking questions orally, either face to face or by telephone.

Structured Interviews are basically social surveys which are read out by the researcher – they use pre-set, standardised, typically closed questions. The aim of structured interviews is to produce quantitative data.

Unstructured Interviews , also known as informal interviews, are more like a guided conversation, and typically involve the researcher asking open-questions which generate qualitative data. The researcher will start with a general research topic in and ask questions in response to the various and differentiated responses the respondents give. Unstructured Interviews are thus a flexible, respondent-led research method.

Semi-Structured Interviews consist of an interview schedule which typically consists of a number of open-ended questions which allow the respondent to give in-depth answers. For example, the researcher might have 10 questions (hence structured) they will ask all respondents, but ask further differentiated (unstructured) questions based on the responses given.

Participant Observation

Participant Observation – involves the researcher joining a group of people, taking an active part in their day to day lives as a member of that group and making in-depth recordings of what she sees.

Participant Observation may be overt , in which case the respondents know that researcher is conducing sociological research, or covert (undercover) where the respondents are deceived into thinking the researcher is ‘one of them’ do not know the researcher is conducting research.

Ethnographies and Case Studies

Ethnographies are an in-depth study of the way of life of a group of people in their natural setting. They are typically very in-depth and long-term and aim for a full (or ‘thick’), multi-layred account of the culture of a group of people. Participant Observation is typically the main method used, but researchers will use all other methods available to get even richer data – such as interviews and analysis of any documents associated with that culture.

Case Studies involves researching a single case or example of something using multiple methods – for example researching one school or factory. An ethnography is simply a very in-depth case study.

Longitudinal Studies

Longitudinal Studies are studies of a sample of people in which information is collected from the same people at intervals over a long period of time. For example, a researcher might start off in 2015 by getting a sample of 1000 people to fill in a questionnaire, and then go back to the same people in 2020, and again in 2025 to collect further information.

Secondary Research Methods

The main type of secondary quantitative data which students of A-level sociology need to know about are official statistics, which are data collected by government agencies, usually on a regular basis and include crime statistics, the Census and quantitative schools data such as exam results.

Secondary qualitative data is data which already exists in written or audiovisual form and include news media, the entire qualitative content of the internent (so blogs and social media data), and more old-school data sources such as diaries, autobiographies and letters.

Sociologists sometimes distinguish between private and public documents, which is a starting point to understanding the enormous variety of data out there!

Secondary data can be a challenge to get your head around because there are so many different types, all with subtly different advantages and disadvantages, and so this particular sub-topic is more likely to demand you to apply your knowledge (rather than just wrote learn) compared to other research methods!

Related Posts

Factors Effecting the Choice of Research Method

Positivism and Interpretivism – A Very Brief Overview

my main research methods page contains links to all of my posts on research methods.

Theory and Methods A Level Sociology Revision Bundle

If you like this sort of thing, then you might like my Theory and Methods Revision Bundle – specifically designed to get students through the theory and methods sections of A level sociology papers 1 and 3.

Contents include:

- 74 pages of revision notes

- 15 mind maps on various topics within theory and methods

- Five theory and methods essays

- ‘How to write methods in context essays’.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

15 thoughts on “Research Methods in Sociology – An Introduction”

- Pingback: CRITICISM OF SOCIOLOGY - Social Vibes

Thanks for the feedback, I do go through and refine as and when I can. Although for the sake of A-level sociology the distinction between research design and research methods would be lost on something like 95% of the students I taught – most just aren’t that interested – hence why I just stick with simple terminology like ‘methods’. Those that take this on to degree level, that’s where those sorts of distinctions start to matter, but point taken, I could be tighter in many places!

You’re all over the place here. You’re confusing research designs and research methods. A survey for example is research design and can be done by different methods. You talk about ‘structured questionnaires’. What, then, would an unstructured questionnaire look like? Can you find an example? You need to put more work in. This will confuse students.

- Pingback: research methods of sociology - infose.xyz

Hey cheers!

Very Helpful!!

Glad to hear it, you’re welcome!

Very useful, got valuable insights…..

good insights and precise

very, very helpful

It’s tooo much amazing… I m feeling so much happy….

- Pingback: Factors Affecting Choice of Research Methods | ReviseSociology

- Pingback: Factors Effecting Choice of Research Methods | ReviseSociology

- Pingback: Research Methods in Sociology – An Introduction | Urban speeches

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

1,695 solutions. Terms in this set (14) Advantages of interviews. Researcher gets to speak to the respondents face-to-face which reduces problem of non-response. Can be conducted by phone- less expensive and issues of interviewer bias. Produce qualitative data which is more detailed and in-depth.

The advantages and disadvantages of social surveys in social research – detailed class notes covering the theoretical, practical and ethical strengths and limitations of social surveys. Generally, surveys are preferred by positivists and good for simple topics, but not so good for more complex topics which require a ‘human touch’.

List the major advantages and disadvantages of surveys, experiments, and observational studies. We now turn to the major methods that sociologists use to gather the information they analyze in their research.

Theoretical Factors. Theoretical strengths of social surveys. Detachment, Objectivity and Validity. Positivists favour questionnaires because they are a detached and objective (unbiased) method, where the sociologist’s personal involvement with respondents is kept to a minimum. Hypothesis Testing.

The many methods available to researchers—including experiments, surveys, field studies, and secondary data analysis—all come with advantages and disadvantages. The strength of a study can depend on the choice and implementation of the appropriate method of gathering research.

As a case in point, the teaching of research methods at AS encourages students to think in fairly basic, clear-cut, terms about the “advantages” and “disadvantages” of various research methods – such as, in this instance, overt participant observation. Using Venkatesh’s “Gang Leader for a Day” (2009)

By the end of this section, you will be able to: Differentiate between four kinds of research methods: surveys, field research, experiments, and secondary data analysis. Understand why different topics are better suited to different research approaches. Sociologists examine the world, see a problem or interesting pattern, and set out to study it.

The many methods available to researchers—including experiments, surveys, field studies, and secondary data analysis—all come with advantages and disadvantages. The strength of a study can depend on the choice and implementation of the appropriate method of gathering research.

Existing Data. LEARNING OBJECTIVE. List the major advantages and disadvantages of surveys, experiments, and observational studies. We now turn to the major methods that sociologists use to gather the information they analyze in their research.

An introduction to research methods in Sociology covering quantitative, qualitative, primary and secondary data and defining the basic types of research method including social surveys, experiments, interviews, participant observation, ethnography and longitudinal studies.