How to Take Notes

How to Use Sources Effectively

Most articles in periodicals and some of the book sources you use, especially those from the children’s room at the library, are probably short enough that you can read them from beginning to end in a reasonable amount of time. Others, however, may be too long for you to do that, and some are likely to cover much more than just your topic. Use the table of contents and the index in a longer book to find the parts of the book that contain information on your topic. When you turn to those parts, skim them to make sure they contain information you can use. Feel free to skip parts that don’t relate to your questions, so you can get the information you need as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, methods for note taking.

Don’t—start reading a book and writing down information on a sheet of notebook paper. If you make this mistake, you’ll end up with a lot of disorganized scribbling that may be practically useless when you’re ready to outline your research paper and write a first draft. Some students who tried this had to cut up their notes into tiny strips, spread them out on the floor, and then tape the strips back together in order to put their information in an order that made sense. Other students couldn’t even do that—without going to a photocopier first—because they had written on both sides of the paper. To avoid that kind of trouble, use the tried-and-true method students have been using for years—take notes on index cards.

Taking Notes on Index Cards

As you begin reading your sources, use either 3″ x 5″ or 4″ x 6″ index cards to write down information you might use in your paper. The first thing to remember is: Write only one idea on each card. Even if you write only a few words on one card, don’t write anything about a new idea on that card. Begin a new card instead. Also, keep all your notes for one card only on that card. It’s fine to write on both the front and back of a card, but don’t carry the same note over to a second card. If you have that much to write, you probably have more than one idea.

After you complete a note card, write the source number of the book you used in the upper left corner of the card. Below the source number, write the exact number or numbers of the pages on which you found the information. In the upper right corner, write one or two words that describe the specific subject of the card. These words are like a headline that describes the main information on the card. Be as clear as possible because you will need these headlines later.

After you finish taking notes from a source, write a check mark on your source card as a reminder that you’ve gone through that source thoroughly and written down all the important information you found there. That way, you won’t wonder later whether you should go back and read that source again.

Taking Notes on Your Computer

Another way to take notes is on your computer. In order to use this method, you have to rely completely on sources that you can take home, unless you have a laptop computer that you can take with you to the library.

If you do choose to take notes on your computer, think of each entry on your screen as one in a pack of electronic note cards. Write your notes exactly as if you were using index cards. Be sure to leave space between each note so that they don’t run together and look confusing when you’re ready to use them. You might want to insert a page break between each “note card.”

When deciding whether to use note cards or a computer, remember one thing—high-tech is not always better. Many students find low-tech index cards easier to organize and use than computer notes that have to be moved around by cutting and pasting. In the end, you’re the one who knows best how you work, so the choice is up to you.

How to Take Effective Notes

Knowing the best format for notes is important, but knowing what to write on your cards or on your computer is essential. Strong notes are the backbone of a good research paper.

Not Too Much or Too Little

When researching, you’re likely to find a lot of interesting information that you never knew before. That’s great! You can never learn too much. But for now your goal is to find information you can use in your research paper. Giving in to the temptation to take notes on every detail you find in your research can lead to a huge volume of notes—many of which you won’t use at all. This can become difficult to manage at later stages, so limit yourself to information that really belongs in your paper. If you think a piece of information might be useful but you aren’t sure, ask yourself whether it helps answer one of your research questions.

Writing too much is one pitfall; writing too little is another. Consider this scenario: You’ve been working in the library for a couple of hours, and your hand grows tired from writing. You come to a fairly complicated passage about how to tell if a dog is angry, so you say to yourself, “I don’t have to write all this down. I’ll remember.” But you won’t remember—especially after all the reading and note taking you have been doing. If you find information you know you want to use later on, get it down. If you’re too tired, take a break or take off the rest of the day and return tomorrow when you’re fresh.

To Note or Not to Note: That is the Question

What if you come across an idea or piece of information that you’ve already found in another source? Should you write it down again? You don’t want to end up with a whole stack of cards with the same information on each one. On the other hand, knowing that more than one source agrees on a particular point is helpful. Here’s the solution: Simply add the number of the new source to the note card that already has the same piece of information written on it. Take notes on both sources. In your paper, you may want to come right out and say that sources disagree on this point. You may even want to support one opinion or the other—if you think you have a strong enough argument based on facts from your research.

Paraphrasing—Not Copying

Have you ever heard the word plagiarism? It means copying someone else’s words and claiming them as your own. It’s really a kind of stealing, and there are strict rules against it.

The trouble is many students plagiarize without meaning to do so. The problem starts at the note-taking stage. As a student takes notes, he or she may simply copy the exact words from a source. The student doesn’t put quotation marks around the words to show that they are someone else’s. When it comes time to draft the paper, the student doesn’t even remember that those words were copied from a source, and the words find their way into the draft and then into the final paper. Without intending to do so, that student has plagiarized, or stolen, another person’s words.

The way to avoid plagiarism is to paraphrase, or write down ideas in your own words rather than copy them exactly. Look again at the model note cards in this chapter, and notice that the words in the notes are not the same as the words from the sources. Some of the notes are not even written in complete sentences. Writing in incomplete sentences is one way to make sure you don’t copy—and it saves you time, energy, and space. When you write a draft of your research paper, of course, you will use complete sentences.

How to Organize Your Notes

Once you’ve used all your sources and taken all your notes, what do you have? You have a stack of cards (or if you’ve taken notes on a computer, screen after screen of entries) about a lot of stuff in no particular order. Now you need to organize your notes in order to turn them into the powerful tool that helps you outline and draft your research paper. Following are some ideas on how to do this, so get your thinking skills in gear to start doing the job for your own paper.

Organizing Note Cards

The beauty of using index cards to take notes is that you can move them around until they are in the order you want. You don’t have to go through complicated cutting-and-pasting procedures, as you would on your computer, and you can lay your cards out where you can see them all at once. One word of caution—work on a surface where your cards won’t fall on the floor while you’re organizing them.

Start by sorting all your cards with the same headlines into the same piles, since all of these note cards are about the same basic idea. You don’t have to worry about keeping notes from the same sources together because each card is marked with a number identifying its source.

Next, arrange the piles of cards so that the order the ideas appear in makes sense. Experts have named six basic types of order. One—or a combination of these—may work for you:

- Chronological , or Time, Order covers events in the order in which they happened. This kind of order works best for papers that discuss historical events or tell about a person’s life.

- Spatial Order organizes your information by its place or position. This kind of order can work for papers about geography or about how to design something—a garden, for example.

- Cause and Effect discusses how one event or action leads to another. This kind of organization works well if your paper explains a scientific process or events in history.

- Problem/Solution explains a problem and one or more ways in which it can be solved. You might use this type of organization for a paper about an environmental issue, such as global warming.

- Compare and Contrast discusses similarities and differences between people, things, events, or ideas.

- Order of Importance explains an idea, starting with its most important aspects first and ending with the least important aspects—or the other way around.

After you determine your basic organization, arrange your piles accordingly. You’ll end up with three main piles—one for sounds, one for facial expressions, and one for body language. Go through each pile and put the individual cards in an order that makes sense. Don’t forget that you can move your cards around, trying out different organizations, until you are satisfied that one idea flows logically into another. Use a paper clip or rubber band to hold the piles together, and then stack them in the order you choose. Put a big rubber band around the whole stack so the cards stay in order.

Organizing Notes on Your Computer

If you’ve taken notes on a computer, organize them in much the same way you would organize index cards. The difference is that you use the cut-and-paste functions on your computer rather than moving cards around. The advantage is that you end up with something that’s already typed—something you can eventually turn into an outline without having to copy anything over. The disadvantage is that you may have more trouble moving computer notes around than note cards: You can’t lay your notes out and look at them all at once, and you may get confused when trying to find where information has moved within a long file on your computer screen.

However, be sure to back up your note cards on an external storage system of your choice. In addition, print hard copies as you work. This way, you won’t lose your material if your hard drive crashes or the file develops a glitch.

Developing a Working Bibliography

When you start your research, your instructor may ask you to prepare a working bibliography listing the sources you plan to use. Your working bibliography differs from your Works Cited page in its scope: your working bibliography is much larger. Your Works Cited page will include only those sources you have actually cited in your research paper.

To prepare a working bibliography, arrange your note cards in the order required by your documentation system (such as MLA and APA) and keyboard the entries following the correct form. If you have created your bibliography cards on the computer, you just have to sort them, usually into alphabetical order.

Developing an Annotated Bibliography

Some instructors may ask you to create an annotated bibliography as a middle step between your working bibliography and your Works Cited page. An annotated bibliography is the same as a working bibliography except that it includes comments about the sources. These notes enable your instructor to assess your progress. They also help you evaluate your information more easily. For example, you might note that some sources are difficult to find, hard to read, or especially useful.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Organizing Research: Taking and Keeping Effective Notes

Once you’ve located the right primary and secondary sources, it’s time to glean all the information you can from them. In this chapter, you’ll first get some tips on taking and organizing notes. The second part addresses how to approach the sort of intermediary assignments (such as book reviews) that are often part of a history course.

Honing your own strategy for organizing your primary and secondary research is a pathway to less stress and better paper success. Moreover, if you can find the method that helps you best organize your notes, these methods can be applied to research you do for any of your classes.

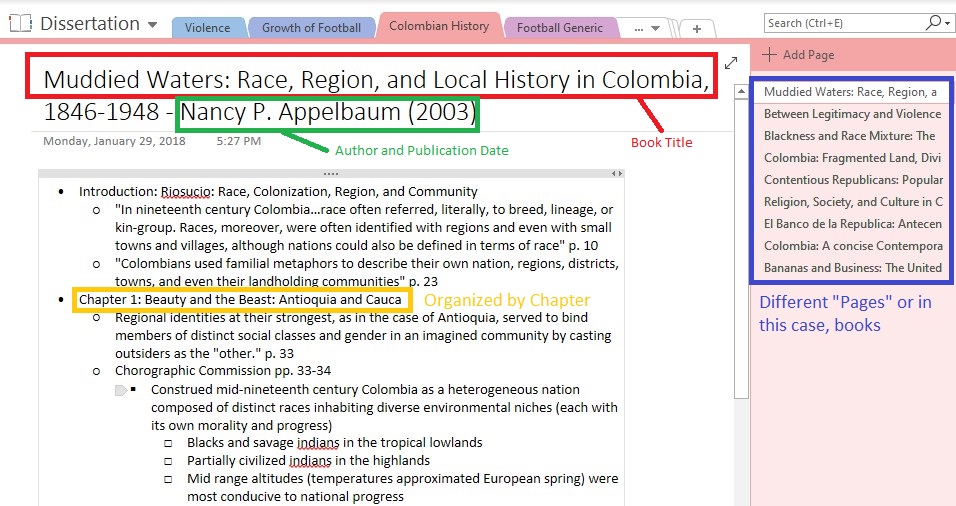

Before the personal computing revolution, most historians labored through archives and primary documents and wrote down their notes on index cards, and then found innovative ways to organize them for their purposes. When doing secondary research, historians often utilized (and many still do) pen and paper for taking notes on secondary sources. With the advent of digital photography and useful note-taking tools like OneNote, some of these older methods have been phased out – though some persist. And, most importantly, once you start using some of the newer techniques below, you may find that you are a little “old school,” and might opt to integrate some of the older techniques with newer technology.

Whether you choose to use a low-tech method of taking and organizing your notes or an app that will help you organize your research, here are a few pointers for good note-taking.

Principles of note-taking

- If you are going low-tech, choose a method that prevents a loss of any notes. Perhaps use one spiral notebook, or an accordion folder, that will keep everything for your project in one space. If you end up taking notes away from your notebook or folder, replace them—or tape them onto blank pages if you are using a notebook—as soon as possible.

- If you are going high-tech, pick one application and stick with it. Using a cloud-based app, including one that you can download to your smart phone, will allow you to keep adding to your notes even if you find yourself with time to take notes unexpectedly.

- When taking notes, whether you’re using 3X5 note cards or using an app described below, write down the author and a shortened title for the publication, along with the page number on EVERY card. We can’t emphasize this point enough; writing down the bibliographic information the first time and repeatedly will save you loads of time later when you are writing your paper and must cite all key information.

- Include keywords or “tags” that capture why you thought to take down this information in a consistent place on each note card (and when using the apps described below). If you are writing a paper about why Martin Luther King, Jr., became a successful Civil Rights movement leader, for example, you may have a few theories as you read his speeches or how those around him described his leadership. Those theories—religious beliefs, choice of lieutenants, understanding of Gandhi—might become the tags you put on each note card.

- Note-taking applications can help organize tags for you, but if you are going low tech, a good idea is to put tags on the left side of a note card, and bibliographic info on the right side.

Organizing research- applications that can help

Using images in research.

- If you are in an archive: make your first picture one that includes the formal collection name, the box number, the folder name and call numbe r and anything else that would help you relocate this information if you or someone else needed to. Do this BEFORE you start taking photos of what is in the folder.

- If you are photographing a book or something you may need to return to the library: take a picture of all the front matter (the title page, the page behind the title with all the publication information, maybe even the table of contents).

Once you have recorded where you find it, resist the urge to rename these photographs. By renaming them, they may be re-ordered and you might forget where you found them. Instead, use tags for your own purposes, and carefully name and date the folder into which the photographs were automatically sorted. There is one free, open-source program, Tropy , which is designed to help organize photos taken in archives, as well as tag, annotate, and organize them. It was developed and is supported by the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. It is free to download, and you can find it here: https://tropy.org/ ; it is not, however, cloud-based, so you should back up your photos. In other cases, if an archive doesn’t allow photography (this is highly unlikely if you’ve made the trip to the archive), you might have a laptop on hand so that you can transcribe crucial documents.

Using note or project-organizing apps

When you have the time to sit down and begin taking notes on your primary sources, you can annotate your photos in Tropy. Alternatively, OneNote, which is cloud-based, can serve as a way to organize your research. OneNote allows you to create separate “Notebooks” for various projects, but this doesn’t preclude you from searching for terms or tags across projects if the need ever arises. Within each project you can start new tabs, say, for each different collection that you have documents from, or you can start new tabs for different themes that you are investigating. Just as in Tropy, as you go through taking notes on your documents you can create your own “tags” and place them wherever you want in the notes.

Another powerful, free tool to help organize research, especially secondary research though not exclusively, is Zotero found @ https://www.zotero.org/ . Once downloaded, you can begin to save sources (and their URL) that you find on the internet to Zotero. You can create main folders for each major project that you have and then subfolders for various themes if you would like. Just like the other software mentioned, you can create notes and tags about each source, and Zotero can also be used to create bibliographies in the precise format that you will be using. Obviously, this function is super useful when doing a long-term, expansive project like a thesis or dissertation.

How History is Made: A Student’s Guide to Reading, Writing, and Thinking in the Discipline Copyright © 2022 by Stephanie Cole; Kimberly Breuer; Scott W. Palmer; and Brandon Blakeslee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Research skills.

- Searching the literature

- Note making for dissertations

- Research Data Management

- Copyright and licenses

- Publishing in journals

- Publishing academic books

- Depositing your thesis

- Research metrics

- Build your online profile

- Finding support

Note making for dissertations: First steps into writing

Note making (as opposed to note taking) is an active practice of recording relevant parts of reading for your research as well as your reflections and critiques of those studies. Note making, therefore, is a pre-writing exercise that helps you to organise your thoughts prior to writing. In this module, we will cover:

- The difference between note taking and note making

- Seven tips for good note making

- Strategies for structuring your notes and asking critical questions

- Different styles of note making

To complete this section, you will need:

- Approximately 20-30 minutes.

- Access to the internet. All the resources used here are available freely.

- Some equipment for jotting down your thoughts, a pen and paper will do, or your phone or another electronic device.

Note taking v note making

When you think about note taking, what comes to mind? Perhaps trying to record everything said in a lecture? Perhaps trying to write down everything included in readings required for a course?

- Note taking is a passive process. When you take notes, you are often trying to record everything that you are reading or listening to. However, you may have noticed that this takes a lot of effort and often results in too many notes to be useful.

- Note making , on the other hand, is an active practice, based on the needs and priorities of your project. Note making is an opportunity for you to ask critical questions of your readings and to synthesise ideas as they pertain to your research questions. Making notes is a pre-writing exercise that develops your academic voice and makes writing significantly easier.

Seven tips for effective note making

Note making is an active process based on the needs of your research. This video contains seven tips to help you make brilliant notes from articles and books to make the most of the time you spend reading and writing.

- Transcript of Seven Tips for Effective Notemaking

Question prompts for strategic note making

You might consider structuring your notes to answer the following questions. Remember that note making is based on your needs, so not all of these questions will apply in all cases. You might try answering these questions using the note making styles discussed in the next section.

- Question prompts for strategic note making

- Background question prompts

- Critical question prompts

- Synthesis question prompts

Answer these six questions to frame your reading and provide context.

- What is the context in which the text was written? What came before it? Are there competing ideas?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the author’s purpose?

- How is the writing organised?

- What are the author’s methods?

- What is the author’s key argument and conclusions?

Answer these six questions to determine your critical perspectivess and develop your academic voice.

- What are the most interesting/compelling ideas (to you) in this study?

- Why do you find them interesting? How do they relate to your study?

- What questions do you have about the study?

- What could it cover better? How could it have defended its research better?

- What are the implications of the study? (Look not just to the conclusions but also to definitions and models)

- Are there any gaps in the study? (Look not just at conclusions but definitions, literature review, methodology)

Answer these five questions to compare aspects of various studies (such as for a literature review.

- What are the similarities and differences in the literature?

- Critically analyse the strengths, limitations, debates and themes that emerg from the literature.

- What would you suggest for future research or practice?

- Where are the gaps in the literature? What is missing? Why?

- What new questions should be asked in this area of study?

Styles of note making

- Linear notes . Great for recording thoughts about your readings. [video]

- Mind mapping : Great for thinking through complex topics. [video]

Further sites that discuss techniques for note making:

- Note-taking techniques

- Common note-taking methods

- Strategies for effective note making

Did you know?

How did you find this Research Skills module

Image Credits: Image #1: David Travis on Unsplash ; Image #2: Charles Deluvio on Unsplash

- << Previous: Searching the literature

- Next: Research Data Management >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 9:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/research-skills

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

Research Paper: A step-by-step guide: 6. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- 1. Getting Started

- 2. Topic Ideas

- 3. Thesis Statement & Outline

- 4. Appropriate Sources

- 5. Search Techniques

- 6. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- 7. Evaluating Sources

- 8. Citations & Plagiarism

- 9. Writing Your Research Paper

Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

How to take notes and document sources.

Note taking is a very important part of the research process. It will help you:

- keep your ideas and sources organized

- effectively use the information you find

- avoid plagiarism

When you find good information to be used in your paper:

- Read the text critically, think how it is related to your argument, and decide how you are going to use it in your paper.

- Select the material that is relevant to your argument.

- Copy the original text for direct quotations or briefly summarize the content in your own words, and make note of how you will use it.

- Copy the citation or publication information of the source.

There are different ways to take notes and organize your research. Check out this video, and try different strategies to find what works best for you.

- << Previous: 5. Search Techniques

- Next: 7. Evaluating Sources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2023 12:12 PM

- URL: https://butte.libguides.com/ResearchPaper

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Now you need to organize your notes in order to turn them into the powerful tool that helps you outline and draft your research paper. Following are some ideas on how to do this, so get your thinking skills in gear to start doing the job for your own paper.

Whether you choose to use a low-tech method of taking and organizing your notes or an app that will help you organize your research, here are a few pointers for good note-taking. Principles of note-taking. Start out how you mean to go on, and guard from the beginning against losing notes.

Note making (as opposed to note taking) is an active practice of recording relevant parts of reading for your research as well as your reflections and critiques of those studies. Note making, therefore, is a pre-writing exercise that helps you to organise your thoughts prior to writing.

• There are a few major ways to take notes (mapping, outlining, 2-column, word-for-word), but this is a personal style choice. Try different ways, but use the one that fits you best, and engages you in the topic. • Pay attention to what each section is about. The Abstract, Discussion, and Conclusion sections usually have the most

How to Take Notes and Document Sources. Note taking is a very important part of the research process. It will help you: keep your ideas and sources organized; effectively use the information you find; avoid plagiarism

In this handout, I explained the importance of notetaking for research papers, provided tips for writing and arranging, and highlighted two common forms of notetaking: the index card method and the notebook method.