The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing

- How Nurses Use Critical Thinking

- How to Improve Critical Thinking

- Common Mistakes

Some experts describe a person’s ability to question belief systems, test previously held assumptions, and recognize ambiguity as evidence of critical thinking. Others identify specific skills that demonstrate critical thinking, such as the ability to identify problems and biases, infer and draw conclusions, and determine the relevance of information to a situation.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN, has been a critical care nurse for 10 years in neurological trauma nursing and cardiovascular and surgical intensive care. He defines critical thinking as “necessary for problem-solving and decision-making by healthcare providers. It is a process where people use a logical process to gather information and take purposeful action based on their evaluation.”

“This cognitive process is vital for excellent patient outcomes because it requires that nurses make clinical decisions utilizing a variety of different lenses, such as fairness, ethics, and evidence-based practice,” he says.

How Do Nurses Use Critical Thinking?

Successful nurses think beyond their assigned tasks to deliver excellent care for their patients. For example, a nurse might be tasked with changing a wound dressing, delivering medications, and monitoring vital signs during a shift. However, it requires critical thinking skills to understand how a difference in the wound may affect blood pressure and temperature and when those changes may require immediate medical intervention.

Nurses care for many patients during their shifts. Strong critical thinking skills are crucial when juggling various tasks so patient safety and care are not compromised.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN, is a nurse educator with a clinical background in surgical-trauma adult critical care, where critical thinking and action were essential to the safety of her patients. She talks about examples of critical thinking in a healthcare environment, saying:

“Nurses must also critically think to determine which patient to see first, which medications to pass first, and the order in which to organize their day caring for patients. Patient conditions and environments are continually in flux, therefore nurses must constantly be evaluating and re-evaluating information they gather (assess) to keep their patients safe.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created hospital care situations where critical thinking was essential. It was expected of the nurses on the general floor and in intensive care units. Crystal Slaughter is an advanced practice nurse in the intensive care unit (ICU) and a nurse educator. She observed critical thinking throughout the pandemic as she watched intensive care nurses test the boundaries of previously held beliefs and master providing excellent care while preserving resources.

“Nurses are at the patient’s bedside and are often the first ones to detect issues. Then, the nurse needs to gather the appropriate subjective and objective data from the patient in order to frame a concise problem statement or question for the physician or advanced practice provider,” she explains.

Top 5 Ways Nurses Can Improve Critical Thinking Skills

We asked our experts for the top five strategies nurses can use to purposefully improve their critical thinking skills.

Case-Based Approach

Slaughter is a fan of the case-based approach to learning critical thinking skills.

In much the same way a detective would approach a mystery, she mentors her students to ask questions about the situation that help determine the information they have and the information they need. “What is going on? What information am I missing? Can I get that information? What does that information mean for the patient? How quickly do I need to act?”

Consider forming a group and working with a mentor who can guide you through case studies. This provides you with a learner-centered environment in which you can analyze data to reach conclusions and develop communication, analytical, and collaborative skills with your colleagues.

Practice Self-Reflection

Rhoads is an advocate for self-reflection. “Nurses should reflect upon what went well or did not go well in their workday and identify areas of improvement or situations in which they should have reached out for help.” Self-reflection is a form of personal analysis to observe and evaluate situations and how you responded.

This gives you the opportunity to discover mistakes you may have made and to establish new behavior patterns that may help you make better decisions. You likely already do this. For example, after a disagreement or contentious meeting, you may go over the conversation in your head and think about ways you could have responded.

It’s important to go through the decisions you made during your day and determine if you should have gotten more information before acting or if you could have asked better questions.

During self-reflection, you may try thinking about the problem in reverse. This may not give you an immediate answer, but can help you see the situation with fresh eyes and a new perspective. How would the outcome of the day be different if you planned the dressing change in reverse with the assumption you would find a wound infection? How does this information change your plan for the next dressing change?

Develop a Questioning Mind

McGowan has learned that “critical thinking is a self-driven process. It isn’t something that can simply be taught. Rather, it is something that you practice and cultivate with experience. To develop critical thinking skills, you have to be curious and inquisitive.”

To gain critical thinking skills, you must undergo a purposeful process of learning strategies and using them consistently so they become a habit. One of those strategies is developing a questioning mind. Meaningful questions lead to useful answers and are at the core of critical thinking .

However, learning to ask insightful questions is a skill you must develop. Faced with staff and nursing shortages , declining patient conditions, and a rising number of tasks to be completed, it may be difficult to do more than finish the task in front of you. Yet, questions drive active learning and train your brain to see the world differently and take nothing for granted.

It is easier to practice questioning in a non-stressful, quiet environment until it becomes a habit. Then, in the moment when your patient’s care depends on your ability to ask the right questions, you can be ready to rise to the occasion.

Practice Self-Awareness in the Moment

Critical thinking in nursing requires self-awareness and being present in the moment. During a hectic shift, it is easy to lose focus as you struggle to finish every task needed for your patients. Passing medication, changing dressings, and hanging intravenous lines all while trying to assess your patient’s mental and emotional status can affect your focus and how you manage stress as a nurse .

Staying present helps you to be proactive in your thinking and anticipate what might happen, such as bringing extra lubricant for a catheterization or extra gloves for a dressing change.

By staying present, you are also better able to practice active listening. This raises your assessment skills and gives you more information as a basis for your interventions and decisions.

Use a Process

As you are developing critical thinking skills, it can be helpful to use a process. For example:

- Ask questions.

- Gather information.

- Implement a strategy.

- Evaluate the results.

- Consider another point of view.

These are the fundamental steps of the nursing process (assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate). The last step will help you overcome one of the common problems of critical thinking in nursing — personal bias.

Common Critical Thinking Pitfalls in Nursing

Your brain uses a set of processes to make inferences about what’s happening around you. In some cases, your unreliable biases can lead you down the wrong path. McGowan places personal biases at the top of his list of common pitfalls to critical thinking in nursing.

“We all form biases based on our own experiences. However, nurses have to learn to separate their own biases from each patient encounter to avoid making false assumptions that may interfere with their care,” he says. Successful critical thinkers accept they have personal biases and learn to look out for them. Awareness of your biases is the first step to understanding if your personal bias is contributing to the wrong decision.

New nurses may be overwhelmed by the transition from academics to clinical practice, leading to a task-oriented mindset and a common new nurse mistake ; this conflicts with critical thinking skills.

“Consider a patient whose blood pressure is low but who also needs to take a blood pressure medication at a scheduled time. A task-oriented nurse may provide the medication without regard for the patient’s blood pressure because medication administration is a task that must be completed,” Slaughter says. “A nurse employing critical thinking skills would address the low blood pressure, review the patient’s blood pressure history and trends, and potentially call the physician to discuss whether medication should be withheld.”

Fear and pride may also stand in the way of developing critical thinking skills. Your belief system and worldview provide comfort and guidance, but this can impede your judgment when you are faced with an individual whose belief system or cultural practices are not the same as yours. Fear or pride may prevent you from pursuing a line of questioning that would benefit the patient. Nurses with strong critical thinking skills exhibit:

- Learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of other nurses

- Look forward to integrating changes that improve patient care

- Treat each patient interaction as a part of a whole

- Evaluate new events based on past knowledge and adjust decision-making as needed

- Solve problems with their colleagues

- Are self-confident

- Acknowledge biases and seek to ensure these do not impact patient care

An Essential Skill for All Nurses

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

By using the strategies in this guide during your daily life and in your nursing role, you can intentionally improve your critical thinking abilities and be rewarded with better patient outcomes and potential career advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Critical Thinking in Nursing

How are critical thinking skills utilized in nursing practice.

Nursing practice utilizes critical thinking skills to provide the best care for patients. Often, the patient’s cause of pain or health issue is not immediately clear. Nursing professionals need to use their knowledge to determine what might be causing distress, collect vital information, and make quick decisions on how best to handle the situation.

How does nursing school develop critical thinking skills?

Nursing school gives students the knowledge professional nurses use to make important healthcare decisions for their patients. Students learn about diseases, anatomy, and physiology, and how to improve the patient’s overall well-being. Learners also participate in supervised clinical experiences, where they practice using their critical thinking skills to make decisions in professional settings.

Do only nurse managers use critical thinking?

Nurse managers certainly use critical thinking skills in their daily duties. But when working in a health setting, anyone giving care to patients uses their critical thinking skills. Everyone — including licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced nurse practitioners —needs to flex their critical thinking skills to make potentially life-saving decisions.

Meet Our Contributors

Crystal Slaughter is a core faculty member in Walden University’s RN-to-BSN program. She has worked as an advanced practice registered nurse with an intensivist/pulmonary service to provide care to hospitalized ICU patients and in inpatient palliative care. Slaughter’s clinical interests lie in nursing education and evidence-based practice initiatives to promote improving patient care.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads is a nurse educator and freelance author and editor. She earned a BSN from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing and an MS in nursing education from Northern Illinois University. Rhoads earned a Ph.D. in education with a concentration in nursing education from Capella University where she researched the moderation effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship of stress and GPA in military veteran nursing students. Her clinical background includes surgical-trauma adult critical care, interventional radiology procedures, and conscious sedation in adult and pediatric populations.

Nicholas McGowan is a critical care nurse with 10 years of experience in cardiovascular, surgical intensive care, and neurological trauma nursing. McGowan also has a background in education, leadership, and public speaking. He is an online learner who builds on his foundation of critical care nursing, which he uses directly at the bedside where he still practices. In addition, McGowan hosts an online course at Critical Care Academy where he helps nurses achieve critical care (CCRN) certification.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples, Importance, & How to Improve)

Successful nursing requires learning several skills used to communicate with patients, families, and healthcare teams. One of the most essential skills nurses must develop is the ability to demonstrate critical thinking. If you are a nurse, perhaps you have asked if there is a way to know how to improve critical thinking in nursing? As you read this article, you will learn what critical thinking in nursing is and why it is important. You will also find 18 simple tips to improve critical thinking in nursing and sample scenarios about how to apply critical thinking in your nursing career.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

4 reasons why critical thinking is so important in nursing, 1. critical thinking skills will help you anticipate and understand changes in your patient’s condition., 2. with strong critical thinking skills, you can make decisions about patient care that is most favorable for the patient and intended outcomes., 3. strong critical thinking skills in nursing can contribute to innovative improvements and professional development., 4. critical thinking skills in nursing contribute to rational decision-making, which improves patient outcomes., what are the 8 important attributes of excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. the ability to interpret information:, 2. independent thought:, 3. impartiality:, 4. intuition:, 5. problem solving:, 6. flexibility:, 7. perseverance:, 8. integrity:, examples of poor critical thinking vs excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. scenario: patient/caregiver interactions, poor critical thinking:, excellent critical thinking:, 2. scenario: improving patient care quality, 3. scenario: interdisciplinary collaboration, 4. scenario: precepting nursing students and other nurses, how to improve critical thinking in nursing, 1. demonstrate open-mindedness., 2. practice self-awareness., 3. avoid judgment., 4. eliminate personal biases., 5. do not be afraid to ask questions., 6. find an experienced mentor., 7. join professional nursing organizations., 8. establish a routine of self-reflection., 9. utilize the chain of command., 10. determine the significance of data and decide if it is sufficient for decision-making., 11. volunteer for leadership positions or opportunities., 12. use previous facts and experiences to help develop stronger critical thinking skills in nursing., 13. establish priorities., 14. trust your knowledge and be confident in your abilities., 15. be curious about everything., 16. practice fair-mindedness., 17. learn the value of intellectual humility., 18. never stop learning., 4 consequences of poor critical thinking in nursing, 1. the most significant risk associated with poor critical thinking in nursing is inadequate patient care., 2. failure to recognize changes in patient status:, 3. lack of effective critical thinking in nursing can impact the cost of healthcare., 4. lack of critical thinking skills in nursing can cause a breakdown in communication within the interdisciplinary team., useful resources to improve critical thinking in nursing, youtube videos, my final thoughts, frequently asked questions answered by our expert, 1. will lack of critical thinking impact my nursing career, 2. usually, how long does it take for a nurse to improve their critical thinking skills, 3. do all types of nurses require excellent critical thinking skills, 4. how can i assess my critical thinking skills in nursing.

• Ask relevant questions • Justify opinions • Address and evaluate multiple points of view • Explain assumptions and reasons related to your choice of patient care options

5. Can I Be a Nurse If I Cannot Think Critically?

- [email protected]

How to Develop Critical Thinking in Nursing

Article 22 Nov 2024 50

How to Develop Critical Thinking in Nursing: A Complete Guide

Nursing is a profession where quick and accurate decisions can save lives. As a nurse, you're not just following protocols—you're solving problems, managing complex situations, and ensuring your patients receive the best possible care. This requires critical thinking, which allows you to assess situations, analyze information, and act confidently based on evidence and reasoning.

This guide will provide practical strategies, relatable examples, and research-backed insights to help you develop critical thinking in nursing. Whether a student or an experienced professional, you'll find actionable advice to enhance your skills and improve your nursing practice.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing involves analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating information to make sound decisions. It also involves understanding and interpreting clinical data to determine the best action.

For instance, a nurse may notice a subtle increase in a patient's heart rate and blood pressure. While these signs may not immediately appear dangerous, critical thinking allows the nurse to question why this is happening and investigate further, potentially identifying a life-threatening condition before it worsens.

Frameworks for Critical Thinking in Nursing

Critical thinking in nursing isn't just about intuition or experience—it's about having a structured approach to decision-making. Established frameworks provide nurses with reliable methods to process information, analyze situations, and act confidently. Let's explore two widely recognized frameworks that play a vital role in developing critical thinking skills in nursing.

1. Tanner's Clinical Judgment Model

Tanner's Clinical Judgment Model is a comprehensive framework that guides nurses through four key phases: noticing, interpreting, responding, and reflecting.

Nurses begin by observing and gathering data. For instance, noticing a patient's subtle changes, like pallor or restlessness, might indicate underlying issues.

This involves analyzing the gathered information to identify the cause. A nurse might interpret restlessness as a sign of low oxygen saturation or anxiety.

Based on interpretation, the nurse takes appropriate action, such as administering oxygen or calming the patient.

After the action, reflection allows the nurse to evaluate their decision and learn from the outcome, refining future judgment.

This iterative process ensures that nurses solve immediate problems and build on their experiences for long-term growth.

2. Bloom's Taxonomy

Bloom's Taxonomy encourages nurses to develop higher-order thinking skills, such as analyzing, evaluating, and creating, rather than simply memorizing information.

Breaking down complex patient symptoms into manageable parts to understand the root cause.

Judging the effectiveness of a treatment plan or intervention.

Developing new approaches to patient care based on evidence and clinical expertise.

For example, a nurse using Bloom's Taxonomy might evaluate the success of a wound care protocol and create an improved version tailored to a specific patient's needs.

3. Why Frameworks Matter

By applying these frameworks, nurses can systematically approach patient care with a balance of logic, creativity, and evidence-based practices. They ensure that patient outcomes are consistent, decisions are well-thought-out, and care quality is optimized. Frameworks like Tanner's Model and Bloom's Taxonomy aren't just theoretical—they're practical tools that empower nurses to handle real-world challenges with clarity and precision.

Whether you're a nursing student or a seasoned professional, integrating these frameworks into your practice will enhance your critical thinking and elevate the standard of care you provide.

Case Study

A nurse notices a patient with mild confusion and restlessness. Instead of attributing it to anxiety, they perform a quick blood sugar test and discover the patient is hypoglycemic. Immediate intervention prevents further complications.

A nurse observes a patient attempting to leave bed unassisted during a night shift. Acting on their intuition, they implement fall prevention measures, averting potential injuries.

Why is Critical Thinking Important in Nursing?

1. improves patient outcomes.

Critical thinking is the backbone of safe and effective patient care. It enables nurses to spot early warning signs, implement timely interventions, and avoid preventable complications. According to the Journal of Nursing Education , critical thinking reduces medical errors by up to 30%.

For example, a nurse in a post-surgery ward might notice a patient complaining of chest pain and shortness of breath. Instead of dismissing it as anxiety, they investigate further and identify early signs of a pulmonary embolism.

2. Enhances Clinical Decision-Making

Nurses often work in unpredictable environments, requiring them to make split-second decisions. Critical thinking allows them to assess situations logically and choose the best action.

For Example, In a pediatric ICU, a nurse uses clinical reasoning to adjust medication dosages based on a child's weight and response to treatment, ensuring the best possible outcome.

1. Practice Reflective Thinking

Reflective thinking involves examining one's actions and identifying areas for improvement. This helps one learn from experience and refine one's approach.

For example, after a shift, a nurse might reflect on a challenging patient interaction and consider how they could have communicated more effectively.

How to Get Started

Keep a journal to document daily experiences.

Ask yourself questions like, "What went well?" and "What could I do differently next time?"

2. Engage in Simulation-Based Training

Simulations provide a safe environment to practice decision-making in realistic scenarios. They help nurses develop problem-solving skills without risking patient safety.

Studies show that simulation training increases nursing students' critical thinking scores by 15% ( PubMed ).

A nurse in training participates in a simulation where they must manage a patient experiencing cardiac arrest. The exercise teaches them to prioritize tasks, delegate responsibilities, and remain calm under pressure.

3. Evidence-Based Practice

Evidence-based practice (EBP) involves using the latest research to guide clinical decisions. It encourages nurses to question traditional methods and adopt strategies that are proven to work.

For Example, a nurse uses updated guidelines for managing pressure ulcers, resulting in faster patient recovery.

Steps to Implement EBP

Stay updated with current research.

Attend workshops and seminars.

Collaborate with colleagues to discuss best practices.

3. Ask "Why" Questions

Socratic questioning helps nurses investigate situations more deeply and avoid making assumptions by asking "why," they explore all possible causes and solutions.

Instead of accepting a high fever as a side effect of medication, a nurse questions if it could indicate an underlying infection.

Practice Tip

During patient rounds, make it a habit to ask:

Why is this symptom occurring?

What else could explain this condition?

Challenges in Developing Critical Thinking Skills

1. common barriers.

Time Constraints : Fast-paced environments leave little room for reflection.

Over-Reliance on Protocols : Following checklists can sometimes hinder creative problem-solving.

Limited Resources : Nurses in rural areas may need more access to training and mentorship.

2. Overcoming Challenges

Peer Mentoring : Pairing with experienced nurses can provide guidance and boost confidence.

Technology Integration : Use mobile apps and e-learning platforms for on-the-go skill development.

Structured Reflection Time : Dedicate a few minutes after each shift for self-assessment.

Key Takeaways

Critical thinking is essential for providing safe, effective, and patient-centered care.

Strategies like reflective thinking, simulation training, evidence-based practice, and Socratic questioning can help nurses improve this skill.

Overcoming barriers requires creativity, mentorship, and a commitment to lifelong learning.

Developing critical thinking in nursing is a continuous journey that requires dedication, curiosity, and practice. Implementing the strategies discussed in this guide can enhance your decision-making abilities, improve patient care, and grow you as a healthcare professional. Remember, every decision you make as a nurse can change lives, so think critically, act confidently, and strive for excellence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is critical thinking in nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing analyzes information, assesses patient conditions, and makes informed decisions to provide the best possible care. It involves evaluating data, questioning assumptions, and applying evidence-based practices to ensure patient safety and improve outcomes.

2. How can I improve my critical thinking skills as a nurse?

You can improve your critical thinking skills by:

Practicing reflective thinking through journaling or post-shift assessments.

Engaging in simulation-based training to handle complex scenarios.

Using evidence-based practices to make informed decisions.

Asking "why" questions to explore multiple solutions to problems.

3. Why is critical thinking necessary for nurses?

Critical thinking is crucial because it:

It helps prevent medical errors.

Enhances decision-making in high-pressure situations.

Improves patient care by identifying early warning signs and implementing appropriate interventions.

4. What are some real-life examples of critical thinking in nursing?

Examples include:

Recognizing early signs of sepsis and taking preventive measures.

A quick blood sugar test identifies and addresses a patient's hypoglycemia.

Implementing fall prevention protocols for a patient showing signs of instability.

5. How do educators teach critical thinking to nursing students?

Educators teach critical thinking by:

Using case-based discussions to analyze real-world scenarios.

Encouraging role-playing exercises to simulate ethical dilemmas and clinical situations.

Promoting reflective journaling and group discussions to foster self-assessment and learning from experiences.

Top 10 Critical Thinking Skills to Develop for Success

How to develop critical thinking skills in 7 steps: practical guide, how to develop critical thinking as a student, the importance of communication skills in academic success, how to create a personalized study schedule for academic success, bridging the gap: the journey from scientific theory to practical innovation, social learning theory in organisational behaviour: key applications, manage stress during exam season: learn practical tips for students, connection between physical activity and academic success, student success: 10 proven strategies for academic excellence, 25 key reasons to study history: knowledge & critical skills, albert bandura’s social cognitive theory in education, top 10 essential time management tips for students, top 10 benefits of a good study environment, 10 tips to create a good study environment at home, 20 essential questions to ask before choosing your college, k to 12 program: benefits, challenges, and global perspectives, how do i prepare for the exam: top study tips and strategies.

The university of tulsa Online Blog

Trending topics in the tu online community

Why Critical Thinking Skills in Nursing Are Essential

Working in health care requires quick thinking and confident decision-making to care for patients. While nurses use a broad range of technical skills to provide quality care, an essential skill that’s easy to overlook is critical thinking. Nursing professionals should explore the benefits of critical thinking skills in nursing, how to apply them, and the ways that advanced education can sharpen their ability to make precise decisions.

Critical Thinking Skills: A Definition

Critical thinking is the process of evaluating facts, interpreting information, and analyzing situations to make informed decisions in various situations. Finding the correct answer to a complex problem isn’t easy. When situations don’t have clear answers and many factors to consider, critical thinking can help individuals move forward and make decisions.

Critical thinking competencies can be applied to a wide range of workplaces and personal situations. In nursing, critical thinking skills can help deliver effective care, handle a patient crisis, and assess the efficacy of treatment plans.

The Importance of Critical Thinking Skills in Nursing

The fast-paced nursing environment requires prompt, data-driven decisions. Nurses use critical thinking daily, reviewing information and making decisions to promote quality care for patients. The following benefits of critical thinking highlight the importance of this skill in nursing careers:

Improves decision-making speed. A critical thinking mindset can help nurses make timely, effective decisions in difficult situations. A systematic method to evaluate decisions and move forward is a powerful tool for nurses.

Refines communication. Improving professional communication allows for factual, efficient, and empathetic conversations with patients and other health care professionals.

Promotes open-mindedness. It’s easy to overlook certain opinions or viewpoints in a high-pressure situation. Thankfully, critical thinking promotes open-mindedness in exploring solutions.

Combats bias. A critical look at different behaviors, contexts, and viewpoints can be helpful for identifying and addressing bias. Nurses must actively seek out ways to confront and remove bias in the workplace.

Critical Thinking in the Nursing Process

There are many ways to apply critical thinking skills to nursing situations. The nursing process is a five-step process to assist nurses in applying critical thinking skills to their daily duties. Experienced nurses and professionals considering a career change to nursing should review the steps as part of their critical thinking process.

Step 1: Assessment

Assessing a patient means far more than taking their vital signs. It also includes collecting sociocultural and psychological data. Lifestyle factors and experiences can affect the treatment process and approach, so skilled nurses review these areas before moving toward the next step, diagnosis.

For example, if a patient reports dizziness or shortness of breath, a nurse should not only check the patient’s temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate but also ask about their family history and recent events.

Step 2: Diagnosis

During the second step, a nurse’s assessment and critical thinking skills produce a clinical judgment. Nurses need to carefully consider all the factors included in the first step. When necessary, consult with other health care professionals before reaching a diagnosis or communicating that diagnosis with the patient.

Discussing a patient’s assessment with other health care professionals requires critical thinking, as the information provided about vital signs, recent events, and family history are key components of this step.

Step 3: Planning

A nurse may be responsible for setting goals and planning a treatment plan for patients. The third step can include setting measurable, achievable goals. Nurses also coordinate care with other health care professionals.

Goals can be simple or complex, depending on the assessment and diagnosis. For example, one patient’s goals may include eating three meals a day, while another’s may include having multiple medications, specialist visits, and physical therapy activities as part of their treatment plan.

Step 4: Implementation

Critical thinking is needed to implement the nursing process, finding ways to carry out the plan with empathy. It’s also important for nurses to document care throughout the fourth step of the process.

For example, nurses should review patient history and consider symptoms before administering medication. Nursing professionals should also think critically about which patients to see first and how to prioritize patients who may need critical attention.

Step 5: Evaluation

Nurses need to continue to evaluate and review the patient’s condition using critical thinking. Evaluation allows nursing professionals to review patient conditions, recommend care plan modification, and consider overall patient status.

For example, identifying whether patients may be ready for a care plan modification or another change in care requires critical thinking and a clear, focused evaluation of multiple patient factors.

How to Foster Critical Thinking Through Nursing Education

Critical thinking is integral to success in the health care field. Thankfully, many ways are available for nurses to improve their critical thinking skills. Below are training, mentoring, and education options for fostering critical thinking.

On-the-Job Training

Because critical thinking is so critical to the daily duties of nurses, experience in the field can improve their ability to evaluate situations and make data-driven decisions. Working firsthand with patients and alongside skilled professionals is a powerful way to see and apply critical thinking in real-world scenarios.

Mentoring Opportunities

Nurses should seek mentorship opportunities for personalized, side-by-side instruction and inspiration from fellow professionals. Mentorships can be either formal or informal opportunities to learn from skilled nurses and health care professionals to promote critical thinking.

Further Education

Many continuing education opportunities are available for nurses. Professionals looking to improve their critical thinking skills should consider enrolling in a course that promotes reflection, evaluation, and analytical thinking.

Review Critical Thinking Skills With The University of Tulsa

Expand your critical thinking skills in nursing by enrolling in a program to earn a degree in the field. The University of Tulsa offers an accelerated online RN to Bachelor of Science in Nursing (RN to BSN) program for students to earn their BSN in as little as 12 months. Take 30 credits of online courses to expand your medical knowledge, general education, and critical thinking abilities. Review the features of this online opportunity to see if it’s the right decision for your career.

Recommended Readings:

The Benefits of Nurse Mentoring

Hospice Nurse: Job Description and Salary

Work-From-Home Safety Checklist: Securing Your Virtual Workspace

American Nurses Association, The Nursing Process

American Nurses Association, What Are the Qualities of a Good Nurse?

Forbes , “The Power of Critical Thinking: Enhancing Decision-Making and Problem-Solving”

Indeed, “Critical Thinking in Nursing (Definition and Vital Tips)”

Indeed, “Critical Thinking Skills in Nursing: Definition and Improvement Tips”

Indeed, “15 Essential Nursing Skills to Include on Your Resume”

StatPearls, “Nursing Process”

Recent Articles

Clinic vs. Hospital Nursing: Which One Should You Choose?

University of Tulsa

Sep 26, 2024

Nursing Manager: Salary and Job Description

What Is Health Promotion in Nursing Practice?

Learn more about the benefits of receiving your degree from the university of tulsa.

- Online Program Tuition

- AGACNP Certificate Online

- Online MSN Program

- Accelerated Online BSN

- RN to BSN Program

- RN to MSN Program

- MS in Cyber Security

- Meet the Team

- Nursing Student Practicum Requirements

- Disclosures for Professional Nursing Licensure

- On Campus Programs

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (Explained W/ Examples)

Last updated on August 23rd, 2023

Critical thinking is a foundational skill applicable across various domains, including education, problem-solving, decision-making, and professional fields such as science, business, healthcare, and more.

It plays a crucial role in promoting logical and rational thinking, fostering informed decision-making, and enabling individuals to navigate complex and rapidly changing environments.

In this article, we will look at what is critical thinking in nursing practice, its importance, and how it enables nurses to excel in their roles while also positively impacting patient outcomes.

What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is a cognitive process that involves analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

It’s a mental activity that goes beyond simple memorization or acceptance of information at face value.

Critical thinking involves careful, reflective, and logical thinking to understand complex problems, consider various perspectives, and arrive at well-reasoned conclusions or solutions.

Key aspects of critical thinking include:

- Analysis: Critical thinking begins with the thorough examination of information, ideas, or situations. It involves breaking down complex concepts into smaller parts to better understand their components and relationships.

- Evaluation: Critical thinkers assess the quality and reliability of information or arguments. They weigh evidence, identify strengths and weaknesses, and determine the credibility of sources.

- Synthesis: Critical thinking involves combining different pieces of information or ideas to create a new understanding or perspective. This involves connecting the dots between various sources and integrating them into a coherent whole.

- Inference: Critical thinkers draw logical and well-supported conclusions based on the information and evidence available. They use reasoning to make educated guesses about situations where complete information might be lacking.

- Problem-Solving: Critical thinking is essential in solving complex problems. It allows individuals to identify and define problems, generate potential solutions, evaluate the pros and cons of each solution, and choose the most appropriate course of action.

- Creativity: Critical thinking involves thinking outside the box and considering alternative viewpoints or approaches. It encourages the exploration of new ideas and solutions beyond conventional thinking.

- Reflection: Critical thinkers engage in self-assessment and reflection on their thought processes. They consider their own biases, assumptions, and potential errors in reasoning, aiming to improve their thinking skills over time.

- Open-Mindedness: Critical thinkers approach ideas and information with an open mind, willing to consider different viewpoints and perspectives even if they challenge their own beliefs.

- Effective Communication: Critical thinkers can articulate their thoughts and reasoning clearly and persuasively to others. They can express complex ideas in a coherent and understandable manner.

- Continuous Learning: Critical thinking encourages a commitment to ongoing learning and intellectual growth. It involves seeking out new knowledge, refining thinking skills, and staying receptive to new information.

Definition of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an intellectual process of analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing is a vital cognitive skill that involves analyzing, evaluating, and making reasoned decisions about patient care.

It’s an essential aspect of a nurse’s professional practice as it enables them to provide safe and effective care to patients.

Critical thinking involves a careful and deliberate thought process to gather and assess information, consider alternative solutions, and make informed decisions based on evidence and sound judgment.

This skill helps nurses to:

- Assess Information: Critical thinking allows nurses to thoroughly assess patient information, including medical history, symptoms, and test results. By analyzing this data, nurses can identify patterns, discrepancies, and potential issues that may require further investigation.

- Diagnose: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data and collaboratively work with other healthcare professionals to formulate accurate nursing diagnoses. This is crucial for developing appropriate care plans that address the unique needs of each patient.

- Plan and Implement Care: Once a nursing diagnosis is established, critical thinking helps nurses develop effective care plans. They consider various interventions and treatment options, considering the patient’s preferences, medical history, and evidence-based practices.

- Evaluate Outcomes: After implementing interventions, critical thinking enables nurses to evaluate the outcomes of their actions. If the desired outcomes are not achieved, nurses can adapt their approach and make necessary changes to the care plan.

- Prioritize Care: In busy healthcare environments, nurses often face situations where they must prioritize patient care. Critical thinking helps them determine which patients require immediate attention and which interventions are most essential.

- Communicate Effectively: Critical thinking skills allow nurses to communicate clearly and confidently with patients, their families, and other members of the healthcare team. They can explain complex medical information and treatment plans in a way that is easily understood by all parties involved.

- Identify Problems: Nurses use critical thinking to identify potential complications or problems in a patient’s condition. This early recognition can lead to timely interventions and prevent further deterioration.

- Collaborate: Healthcare is a collaborative effort involving various professionals. Critical thinking enables nurses to actively participate in interdisciplinary discussions, share their insights, and contribute to holistic patient care.

- Ethical Decision-Making: Critical thinking helps nurses navigate ethical dilemmas that can arise in patient care. They can analyze different perspectives, consider ethical principles, and make morally sound decisions.

- Continual Learning: Critical thinking encourages nurses to seek out new knowledge, stay up-to-date with the latest research and medical advancements, and incorporate evidence-based practices into their care.

In summary, critical thinking is an integral skill for nurses, allowing them to provide high-quality, patient-centered care by analyzing information, making informed decisions, and adapting their approaches as needed.

It’s a dynamic process that enhances clinical reasoning , problem-solving, and overall patient outcomes.

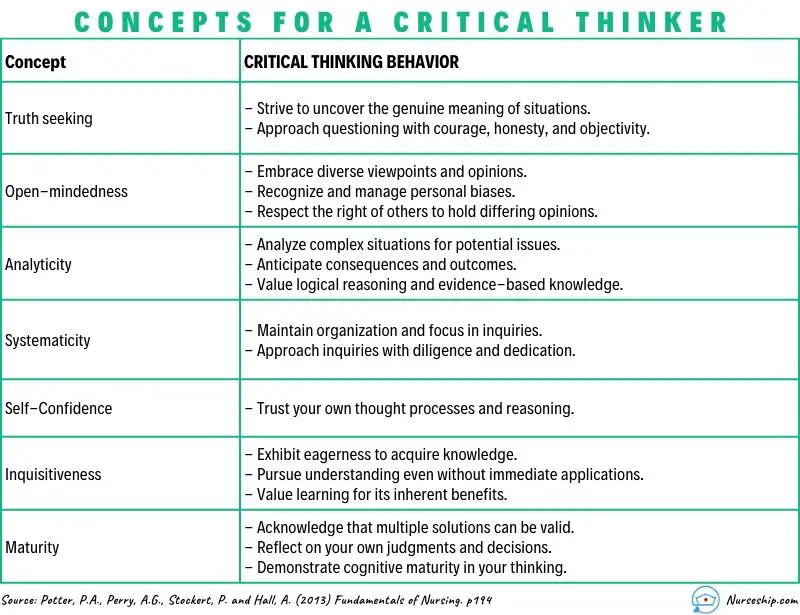

What are the Levels of Critical Thinking in Nursing?

The development of critical thinking in nursing practice involves progressing through three levels: basic, complex, and commitment.

The Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor model outlines this progression.

1. Basic Critical Thinking:

At this level, learners trust experts for solutions. Thinking is based on rules and principles. For instance, nursing students may strictly follow a procedure manual without personalization, as they lack experience. Answers are seen as right or wrong, and the opinions of experts are accepted.

2. Complex Critical Thinking:

Learners start to analyze choices independently and think creatively. They recognize conflicting solutions and weigh benefits and risks. Thinking becomes innovative, with a willingness to consider various approaches in complex situations.

3. Commitment:

At this level, individuals anticipate decision points without external help and take responsibility for their choices. They choose actions or beliefs based on available alternatives, considering consequences and accountability.

As nurses gain knowledge and experience, their critical thinking evolves from relying on experts to independent analysis and decision-making, ultimately leading to committed and accountable choices in patient care.

Why Critical Thinking is Important in Nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing for several crucial reasons:

Patient Safety:

Nursing decisions directly impact patient well-being. Critical thinking helps nurses identify potential risks, make informed choices, and prevent errors.

Clinical Judgment:

Nursing decisions often involve evaluating information from various sources, such as patient history, lab results, and medical literature.

Critical thinking assists nurses in critically appraising this information, distinguishing credible sources, and making rational judgments that align with evidence-based practices.

Enhances Decision-Making:

In nursing, critical thinking allows nurses to gather relevant patient information, assess it objectively, and weigh different options based on evidence and analysis.

This process empowers them to make informed decisions about patient care, treatment plans, and interventions, ultimately leading to better outcomes.

Promotes Problem-Solving:

Nurses encounter complex patient issues that require effective problem-solving.

Critical thinking equips them to break down problems into manageable parts, analyze root causes, and explore creative solutions that consider the unique needs of each patient.

Drives Creativity:

Nursing care is not always straightforward. Critical thinking encourages nurses to think creatively and explore innovative approaches to challenges, especially when standard protocols might not suffice for unique patient situations.

Fosters Effective Communication:

Communication is central to nursing. Critical thinking enables nurses to clearly express their thoughts, provide logical explanations for their decisions, and engage in meaningful dialogues with patients, families, and other healthcare professionals.

Aids Learning:

Nursing is a field of continuous learning. Critical thinking encourages nurses to engage in ongoing self-directed education, seeking out new knowledge, embracing new techniques, and staying current with the latest research and developments.

Improves Relationships:

Open-mindedness and empathy are essential in nursing relationships.

Critical thinking encourages nurses to consider diverse viewpoints, understand patients’ perspectives, and communicate compassionately, leading to stronger therapeutic relationships.

Empowers Independence:

Nursing often requires autonomous decision-making. Critical thinking empowers nurses to analyze situations independently, make judgments without undue influence, and take responsibility for their actions.

Facilitates Adaptability:

Healthcare environments are ever-changing. Critical thinking equips nurses with the ability to quickly assess new information, adjust care plans, and navigate unexpected situations while maintaining patient safety and well-being.

Strengthens Critical Analysis:

In the era of vast information, nurses must discern reliable data from misinformation.

Critical thinking helps them scrutinize sources, question assumptions, and make well-founded choices based on credible information.

How to Apply Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples)

Here are some examples of how nurses can apply critical thinking.

Assess Patient Data:

Critical Thinking Action: Carefully review patient history, symptoms, and test results.

Example: A nurse notices a change in a diabetic patient’s blood sugar levels. Instead of just administering insulin, the nurse considers recent dietary changes, activity levels, and possible medication interactions before adjusting the treatment plan.

Diagnose Patient Needs:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze patient data to identify potential nursing diagnoses.

Example: After reviewing a patient’s lab results, vital signs, and observations, a nurse identifies “ Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity ” due to the patient’s limited mobility.

Plan and Implement Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Develop a care plan based on patient needs and evidence-based practices.

Example: For a patient at risk of falls, the nurse plans interventions such as hourly rounding, non-slip footwear, and bed alarms to ensure patient safety.

Evaluate Interventions:

Critical Thinking Action: Assess the effectiveness of interventions and modify the care plan as needed.

Example: After administering pain medication, the nurse evaluates its impact on the patient’s comfort level and considers adjusting the dosage or trying an alternative pain management approach.

Prioritize Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Determine the order of interventions based on patient acuity and needs.

Example: In a busy emergency department, the nurse triages patients by considering the severity of their conditions, ensuring that critical cases receive immediate attention.

Collaborate with the Healthcare Team:

Critical Thinking Action: Participate in interdisciplinary discussions and share insights.

Example: During rounds, a nurse provides input on a patient’s response to treatment, which prompts the team to adjust the care plan for better outcomes.

Ethical Decision-Making:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze ethical dilemmas and make morally sound choices.

Example: When a terminally ill patient expresses a desire to stop treatment, the nurse engages in ethical discussions, respecting the patient’s autonomy and ensuring proper end-of-life care.

Patient Education:

Critical Thinking Action: Tailor patient education to individual needs and comprehension levels.

Example: A nurse uses visual aids and simplified language to explain medication administration to a patient with limited literacy skills.

Adapt to Changes:

Critical Thinking Action: Quickly adjust care plans when patient conditions change.

Example: During post-operative recovery, a nurse notices signs of infection and promptly informs the healthcare team to initiate appropriate treatment adjustments.

Critical Analysis of Information:

Critical Thinking Action: Evaluate information sources for reliability and relevance.

Example: When presented with conflicting research studies, a nurse critically examines the methodologies and sample sizes to determine which study is more credible.

Making Sense of Critical Thinking Skills

What is the purpose of critical thinking in nursing.

The purpose of critical thinking in nursing is to enable nurses to effectively analyze, interpret, and evaluate patient information, make informed clinical judgments, develop appropriate care plans, prioritize interventions, and adapt their approaches as needed, thereby ensuring safe, evidence-based, and patient-centered care.

Why critical thinking is important in nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing because it promotes safe decision-making, accurate clinical judgment, problem-solving, evidence-based practice, holistic patient care, ethical reasoning, collaboration, and adapting to dynamic healthcare environments.

Critical thinking skill also enhances patient safety, improves outcomes, and supports nurses’ professional growth.

How is critical thinking used in the nursing process?

Critical thinking is integral to the nursing process as it guides nurses through the systematic approach of assessing, diagnosing, planning, implementing, and evaluating patient care. It involves:

- Assessment: Critical thinking enables nurses to gather and interpret patient data accurately, recognizing relevant patterns and cues.

- Diagnosis: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data, identify nursing diagnoses, and differentiate actual issues from potential complications.

- Planning: Critical thinking helps nurses develop tailored care plans, selecting appropriate interventions based on patient needs and evidence.

- Implementation: Nurses make informed decisions during interventions, considering patient responses and adjusting plans as needed.

- Evaluation: Critical thinking supports the assessment of patient outcomes, determining the effectiveness of intervention, and adapting care accordingly.

Throughout the nursing process , critical thinking ensures comprehensive, patient-centered care and fosters continuous improvement in clinical judgment and decision-making.

What is an example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice?

An example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice could be:

A nurse is caring for a patient with a complex medical history who is experiencing a new set of symptoms. The nurse carefully reviews the patient’s history, recent test results, and medication list.

While discussing the case with the healthcare team, the nurse realizes that the current treatment plan might not be addressing all aspects of the patient’s condition.

Instead of simply following the established protocol, the nurse independently considers alternative approaches based on their assessment.

The nurse proposes a modification to the treatment plan, citing the rationale and evidence supporting the change.

This demonstrates independent thinking by critically evaluating the situation, challenging assumptions, and advocating for a more personalized and effective patient care approach.

How to use Costa’s level of questioning for critical thinking in nursing?

Costa’s levels of questioning can be applied in nursing to facilitate critical thinking and stimulate a deeper understanding of patient situations. The levels of questioning are as follows:

- 15 Attitudes of Critical Thinking in Nursing (Explained W/ Examples)

- Nursing Concept Map (FREE Template)

- Clinical Reasoning In Nursing (Explained W/ Example)

- 8 Stages Of The Clinical Reasoning Cycle

- How To Improve Critical Thinking Skills In Nursing? 24 Strategies With Examples

- What is the “5 Whys” Technique?

- What Are Socratic Questions?

Critical thinking in nursing is the foundation that underpins safe, effective, and patient-centered care.

Critical thinking skills empower nurses to navigate the complexities of their profession while consistently providing high-quality care to diverse patient populations.

Reading Recommendation

Potter, P.A., Perry, A.G., Stockert, P. and Hall, A. (2013) Fundamentals of Nursing

Comments are closed.

Medical & Legal Disclaimer

All the contents on this site are for entertainment, informational, educational, and example purposes ONLY. These contents are not intended to be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or practice guidelines. However, we aim to publish precise and current information. By using any content on this website, you agree never to hold us legally liable for damages, harm, loss, or misinformation. Read the privacy policy and terms and conditions.

Privacy Policy

Terms & Conditions

© 2024 nurseship.com. All rights reserved.

- Visit Nurse.com on Facebook

- Visit Nurse.com on YouTube

- Visit Nurse.com on Instagram

- Visit Nurse.com on LinkedIn

Nurse.com by Relias . © Relias LLC 2024. All Rights Reserved.

Account Management

Log in to manage your policy, generate a certificate of insurance (COI), make a payment, and more.

Log in to your account to update your information or manage your policy.

Download a Certificate of Insurance (COI) to provide to your employer.

Make a Payment

Make a one-time payment, set up autopay, or update your payment information.

Submit a notice of an incident or claim in just minutes.

Topics on this page:

Why Critical Thinking in Nursing Is Important

8 examples of critical thinking in nursing, improving the quality of patient care, the importance of critical thinking in nursing.

Jul 24, 2024

While not every decision is an immediate life-and-death situation, there are hundreds of decisions nurses must make every day that impact patient care in ways small and large.

“Being able to assess situations and make decisions can lead to life-or-death situations,” said nurse anesthetist Aisha Allen . “Critical thinking is a crucial and essential skill for nurses.”

The National League for Nursing Accreditation Commission (NLNAC) defines critical thinking in nursing this way: “the deliberate nonlinear process of collecting, interpreting, analyzing, drawing conclusions about, presenting, and evaluating information that is both factually and belief-based. This is demonstrated in nursing by clinical judgment, which includes ethical, diagnostic, and therapeutic dimensions and research.”

An eight-year study by Johns Hopkins reports that 10% of deaths in the U.S. are due to medical error — the third-highest cause of death in the country.

“Diagnostic errors, medical mistakes, and the absence of safety nets could result in someone’s death,” wrote Dr. Martin Makary , professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Everyone makes mistakes — even doctors. Nurses applying critical thinking skills can help reduce errors.

“Question everything,” said pediatric nurse practitioner Ersilia Pompilio RN, MSN, PNP . “Especially doctor’s orders.” Nurses often spend more time with patients than doctors and may notice slight changes in conditions that may not be obvious. Resolving these observations with treatment plans can help lead to better care.

Key Nursing Critical Thinking Skills

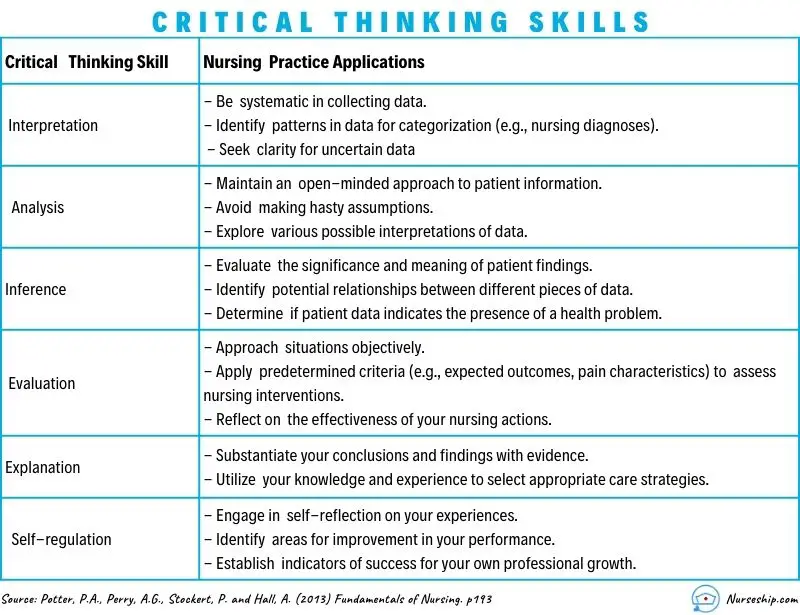

Some of the most important critical thinking skills nurses use daily include interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation.

- Interpretation: Understanding the meaning of information or events.

- Analysis: Investigating a course of action based on objective and subjective data.

- Evaluation: Assessing the value of information and its credibility.

- Inference: Making logical deductions about the impact of care decisions.

- Explanation: Translating complicated and often complex medical information to patients and families in a way they can understand to make decisions about patient care.

- Self-Regulation: Avoiding the impact of unconscious bias with cognitive awareness.

These skills are used in conjunction with clinical reasoning. Based on training and experience, nurses use these skills and then have to make decisions affecting care.

It’s the ultimate test of a nurse’s ability to gather reliable data and solve complex problems. However, critical thinking goes beyond just solving problems. Critical thinking incorporates questioning and critiquing solutions to find the most effective one. For example, treating immediate symptoms may temporarily solve a problem, but determining the underlying cause of the symptoms is the key to effective long-term health.

Here are some real-life examples of how nurses apply critical thinking on the job every day, as told by nurses themselves.

Example #1: Patient Assessments

“Doing a thorough assessment on your patient can help you detect that something is wrong, even if you’re not quite sure what it is,” said Shantay Carter , registered nurse and co-founder of Women of Integrity . “When you notice the change, you have to use your critical thinking skills to decide what’s the next step. Critical thinking allows you to provide the best and safest care possible.”

Example #2: First Line of Defense

Often, nurses are the first line of defense for patients.

“One example would be a patient that had an accelerated heart rate,” said nurse educator and adult critical care nurse Dr. Jenna Liphart Rhoads . “As a nurse, it was my job to investigate the cause of the heart rate and implement nursing actions to help decrease the heart rate prior to calling the primary care provider.”

Nurses with poor critical thinking skills may fail to detect a patient in stress or deteriorating condition. This can result in what’s called a “ failure to rescue ,” or FTR, which can lead to adverse conditions following a complication that leads to mortality.

Example #3: Patient Interactions

Nurses are the ones taking initial reports or discussing care with patients.

“We maintain relationships with patients between office visits,” said registered nurse, care coordinator, and ambulatory case manager Amelia Roberts . “So, when there is a concern, we are the first name that comes to mind (and get the call).”

“Several times, a parent called after the child had a high temperature, and the call came in after hours,” Roberts said. “Doing a nursing assessment over the phone is a special skill, yet based on the information gathered related to the child’s behavior (and) fluid intake, there were several recommendations I could make.”

Deciding whether it was OK to wait until the morning, page the primary care doctor, or go to the emergency room to be evaluated takes critical thinking.

Example #4: Using Detective Skills

Nurses have to use acute listening skills to discern what patients are really telling them (or not telling them) and whether they are getting the whole story.

“I once had a 5-year-old patient who came in for asthma exacerbation on repeated occasions into my clinic,” said Pompilio. “The mother swore she was giving her child all her medications, but the asthma just kept getting worse.”

Pompilio asked the parent to keep a medication diary.

“It turned out that after a day or so of medication and alleviation in some symptoms, the mother thought the child was getting better and stopped all medications,” she said.

Example #5: Prioritizing

“Critical thinking is present in almost all aspects of nursing, even those that are not in direct action with the patient,” said Rhoads. “During report, nurses decide which patient to see first based on the information gathered, and from there they must prioritize their actions when in a patient’s room. Nurses must be able to scrutinize which medications can be taken together, and which modality would be best to help a patient move from the bed to the chair.”

A critical thinking skill in prioritization is cognitive stacking. Cognitive stacking helps create smooth workflow management to set priorities and help nurses manage their time. It helps establish routines for care while leaving room within schedules for the unplanned events that will inevitably occur. Even experienced nurses can struggle with juggling today’s significant workload, prioritizing responsibilities, and delegating appropriately.

Example #6: Medication & Care Coordination

Another aspect that often falls to nurses is care coordination. A nurse may be the first to notice that a patient is having an issue with medications.

“Based on a report of illness in a patient who has autoimmune challenges, we might recommend that a dose of medicine that interferes with immune response be held until we communicate with their specialty provider,” said Roberts.

Nurses applying critical skills can also help ease treatment concerns for patients.

“We might recommend a patient who gets infusions come in earlier in the day to get routine labs drawn before the infusion to minimize needle sticks and trauma,” Robert said.

Example #7: Critical Decisions

During the middle of an operation, the anesthesia breathing machine Allen was using malfunctioned.

“I had to critically think about whether or not I could fix this machine or abandon that mode of delivering nursing anesthesia care safely,” she said. “I chose to disconnect my patient from the malfunctioning machine and retrieve tools and medications to resume medication administration so that the surgery could go on.”

Nurses are also called on to do rapid assessments of patient conditions and make split-second decisions in the operating room.

“When blood pressure drops, it is my responsibility to decide which medication and how much medication will fix the issue,” Allen said. “I must work alongside the surgeons and the operating room team to determine the best plan of care for that patient’s surgery.”

“On some days, it seems like you are in the movie ‘The Matrix,’” said Pompilio. “There’s lots of chaos happening around you. Your patient might be decompensating. You have to literally stop time and take yourself out of the situation and make a decision.”

Example #8: Fast & Flexible Decisions

Allen said she thinks electronics are great, but she can remember a time when technology failed her.

“The hospital monitor that gives us vitals stopped correlating with real-time values,” she said. “So I had to rely on basic nursing skills to make sure my patient was safe. (Pulse check, visual assessments, etc.)”

In such cases, there may not be enough time to think through every possible outcome. Critical thinking combined with experience gives nurses the ability to think quickly and make the right decisions.

Nurses who think critically are in a position to significantly increase the quality of patient care and avoid adverse outcomes.

“Critical thinking allows you to ensure patient safety,” said Carter. “It’s essential to being a good nurse.”

Nurses must be able to recognize a change in a patient’s condition, conduct independent interventions, anticipate patients and provider needs, and prioritize. Such actions require critical thinking ability and advanced problem-solving skills.

“Nurses are the eyes and ears for patients, and critical thinking allows us to be their advocates,” said Allen.

Image courtesy of iStock.com/ davidf

Last updated on Jul 24, 2024. Originally published on Aug 25, 2021.

- Career Growth

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Berxi™ or Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance Company. This article (subject to change without notice) is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute professional advice. Click here to read our full disclaimer

The product descriptions provided here are only brief summaries and may be changed without notice. The full coverage terms and details, including limitations and exclusions, are contained in the insurance policy. If you have questions about coverage available under our plans, please review the policy or contact us at 833-242-3794 or [email protected] . “20% savings” is based on industry pricing averages.

Berxi™ is a part of Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance ( BHSI ). Insurance products are distributed through Berkshire Hathaway Global Insurance Services, California License # 0K09397. BHSI is part of Berkshire Hathaway’s National Indemnity group of insurance companies, consisting of National Indemnity and its affiliates, which hold financial strength ratings of A++ from AM Best and AA+ from Standard & Poor’s. The rating scales can be found at www.ambest.com and www.standardandpoors.com , respectively.

No warranty, guarantee, or representation, either expressed or implied, is made as to the correctness, accuracy, completeness, adequacy, or sufficiency of any representation or information. Any opinions expressed herein are subject to change without notice.

The information on this web site is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment, and does not purport to establish a standard of care under any circumstances. All content, including text, graphics, images and information, contained on or available through this web site is for general information purposes only based upon the information available at the time of presentation, and does not constitute medical, legal, regulatory, compliance, financial, professional, or any other advice.

BHSI makes no representation and assumes no responsibility or liability for the accuracy of information contained on or available through this web site, and such information is subject to change without notice. You are encouraged to consider and confirm any information obtained from or through this web site with other sources, and review all information regarding any medical condition or treatment with your physician or medical care provider. NEVER DISREGARD PROFESSIONAL MEDICAL ADVICE OR DELAY SEEKING MEDICAL TREATMENT BECAUSE OF SOMETHING THAT YOU HAVE READ ON OR ACCESSED THROUGH THIS WEB SITE.

BHSI is not a medical organization, and does not recommend, endorse or make any representation about the efficacy, appropriateness or suitability of any specific tests, products, procedures, treatments, services, opinions, health care providers or other information contained on or available through this web site. BHSI IS NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR, AND EXPRESSLY DISCLAIMS ALL LIABILITY FOR, ANY ADVICE, COURSE OF TREATMENT, DIAGNOSIS OR ANY OTHER SERVICES OR PRODUCTS THAT YOU OBTAIN AFTER REVIEWING THIS WEB SITE.

Want Berxi articles delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for our monthly newsletter below!

" * " indicates required fields

How we use your email address Berxi will not sell or rent your email address to third parties unless otherwise notified. Other than where necessary to administer your insurance policy or where required by law, Berxi will not disclose your email address to third parties. Your email address is required to identify you for access to the Berxi website. You may also receive newsletters, product updates, and communications about quotes and policies.

Paul Dughi is a contributing writer for Berxi, as well as a journalist and freelance writer. He has held executive management positions in the media industry for the past 25 years.

Related Articles

Breaking Bad News to Patients: A Nurse’s Guide to SPIKES

Michael Walton Oct 17, 2024

Delegation in Nursing: Steps, Skills, & Solutions for Creating Balance at Work

Kristy Snyder Jul 24, 2024

The 7 Most Common Nursing Mistakes (And What You Can Do If You Make One)

Paul Dughi Aug 28, 2024

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

Critical thinking skills in nursing drive the nurse's decision-making ability. It impacts every aspect of patient care. Here are four reasons why nurses must develop critical thinking skills.

1. What is critical thinking in nursing? Critical thinking in nursing analyzes information, assesses patient conditions, and makes informed decisions to provide the best possible care. It involves evaluating data, questioning assumptions, and applying evidence-based practices to ensure patient safety and improve outcomes. 2.

In nursing, critical thinking skills can help deliver effective care, handle a patient crisis, and assess the efficacy of treatment plans. The fast-paced nursing environment requires prompt, data-driven decisions. Nurses use critical thinking daily, reviewing information and making decisions to promote quality care for patients.

Use your critical-thinking skills to interpret and understand the importance of test results and the patient’s clinical presentation, including their vital signs. Then prioritize interventions and anticipate potential complications.

Critical thinking in nursing is a vital cognitive skill that involves analyzing, evaluating, and making reasoned decisions about patient care. It’s an essential aspect of a nurse’s professional practice as it enables them to provide safe and effective care to patients.

Critical thinking equips nurses with problem-solving skills to handle these situations effectively. Whether it’s addressing a sudden change in a patient's condition or managing multiple patients with diverse needs, critical thinking helps nurses prioritize tasks and make informed decisions quickly.

Some of the most important critical thinking skills nurses use daily include interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation. Interpretation: Understanding the meaning of information or events. Analysis: Investigating a course of action based on objective and subjective data.

The growing body of research, patient acuity, and complexity of care demand higher-order thinking skills. Critical thinking involves the application of knowledge and experience to identify patient problems and to direct clinical judgments and actions that result in positive patient outcomes.

Mastering a set of core skills can help nurses navigate the complexities of their daily responsibilities. Whether it's communicating effectively with patients, thinking critically in high-pressure situations, or managing time efficiently, these skills lay the foundation for success in nursing.