How to Write an HSC English Creative Writing Piece

Expert reviewed • 22 November 2024 • 8 minute read

Video coming soon!

How to Write a Creative Text

When it comes to writing creatively, there is no real correct way of constructing or writing a piece. This is because creativity and manipulation of form, structure and techniques is encouraged. However, there are aspects that can be included in your writing, to elevate it to a band 6 level.

- It is good to include underlying meanings/lessons in your storyline, that a reader can discover through further analysis

- Will the storyline be linear, or will it include flashbacks? The choice is up to you. A good story can use any structure, or a combination of more than one.

- Characters are generally a great addition to a creative piece. Developing characters throughout a text can give the reader something to relate to, enhancing their engagement.

- Develop a setting where this story is placed - A setting provides the framework in which the piece is created, and as such, ensures the writers ability to manipulate techniques to relate to the storyline.

Some examples of stylistic features that can be used to elevate your text could include:

- Fragmented structures - Fragmented structures in writing refer to a style where sentences are intentionally broken up. This can be used for stylistic effect, to convey confusion and urgency, or to mimic natural speech. Fragmented structures can also help to create a choppy rhythm or to emphasise particular points.

- Anecdotes - An anecdote is a short, interesting, or amusing story about a real incident or person. Anecdotes are commonly used in both conversational and formal storytelling and can serve to illustrate a point, entertain the audience, or create a connection with the reader or listener.

- Poems/Songs - Using poems and songs in the middle of text or between paragraphs can increase the engagement of the reader and elevate the emotional impact of the narrative. However, you must ensure that they are of good quality and fit into your piece. For example, you can have a character singing or humming a song.

- Run-on sentences - A run-on sentence occurs when two or more independent clauses (clauses that could stand alone as separate sentences) are connected improperly without proper punctuation. For example: "I love to write it is my passion" is a run-on sentence because it consists of two independent clauses that are not separated. Run-on sentences can make text difficult to understand and disrupt the flow of writing.

Practice Question 1

The following passage is an introduction to a creative writing piece:

The sun dipped below the horizon, casting a fiery glow across the deserted beach. Waves whispered secrets to the shore, their soft murmurs a haunting lullaby. In the distance, a solitary figure stood, shrouded in twilight’s embrace, staring into the abyss of the endless sea. The air was thick with the scent of salt and mystery, hinting at untold stories waiting to unfold.

Determine any aspects of the text which could be improved, and compare them with suggestions provided below.

- The introduction of a character could be included in the given paragraph. Some details about a solitary figure can give readers a hint about who they are or why they are there, adding a personal element which the reader can connect with.

- More vivid and varied imagery can be used to make the introduction more engaging.

- The sensory details of the passage could be improved, by incorporating more of the five senses to create a richer experience.

NOTE: Always remember to provide a title for the text you have created!

How to Write an HSC English Discursive Writing Piece

Return to Module 3: Module C: The Craft of Writing

FLASH SALE! 20% OFF ALL BOOKS & FLASHCARDS UNTIL 29 NOV! USE CODE: FRI20. SHOP NOW !

Discovery: The Ultimate Guide to Creative Writing

Elyse Popplewell

Friday 4th, March 2016

If you’re a first time reader, then you might not be aware of my free online HSC tutoring for English (including HSC creative writing), and other subjects. Check it out! Also – I have a deal for you. If this post is crazy helpful, then you should share it with your friends on Facebook . Deal? Awesome.

HSC Creative Writing: The Guide.

HSC creative writing can be a pain for some and the time to shine for others. Getting started is the most difficult part. When you have something to work with, it is simply a matter of moulding it to perfection. When you have nothing, you have a seemingly difficult road ahead. After several ATAR Notes members expressed that they need help with HSC creative writing, I wrote this to give you some starting points. Then I edited this, and re-wrote it so that it helps you from the beginning stages until the very last days of editing. Fear no more, HSC creative writing doesn’t have to be the foe that it is in your head! Let’s get started.

Surprise: You’re the composer!

Write about what you know

In the years 2010-2015, not once has Paper 1 specified a form that you have to use. Every year in that time frame they have asked for “imaginative writing” except in 2011 when they asked for a “creative piece” of writing. Most commonly, students write in the short story form. However, students can also write speeches, opinion articles, memoirs, monologues, letters, diary entries, or hybrid medium forms. Think about how you can play to your strengths. Are you the more analytical type and less creative? Consider using that strength in the “imaginative writing” by opting to write a feature article or a speech. If you want to ask questions about your form, then please check out my free online HSC tutoring for English and other subjects.

Tense is a very powerful tool that you can use in your writing to increase intensity or create a tone of detachment, amongst other things. Writing entirely in the present tense is not as easy as it seems, it is very easy to fall into past tense. The present tense creates a sense of immediacy, a sense of urgency. If you’re writing with suspense or about action, consider the present tense.

“We stand here together, linking arms. The car screeches to a stop in front of our unified bodies. The frail man alights from the vehicle and stares into my eyes.”

The past tense is the most common in short stories. The past tense can be reflective, recounting, or perhaps just the most natural tense to write in.

“We stood together, linking arms. The car screeched to a stop in front of us. The frail man alighted from his vehicle and stared into my eyes.”

The future tense is difficult to use for short stories. However, you can really manipulate the future tense to work in your favour if you are writing a creative speech. A combination of tenses will most probably create a seamless link between cause and effect in a speech.

“We will stand together with our arms linked. The man may intimidate us all he likes, but together, when we are unified, we are stronger he will ever be.”

It is also important to point out that using a variety of tenses may work best for your creative. If you are flashing back, the easiest way to do that is to establish the tense firmly.

Giving your setting some texture

You ultimately want your creative writing to take your marker to a new place, a new world, and you want them to feel as though they understand it like they would their own kitchen. The most skilled writers can make places like Hogwarts seem like your literary home. At the Year 12 level, we aren’t all at that level. The best option is to take a setting you know and describe it in every sense – taste, smell, feel, sound and sight.

Choose a place special and known to you. Does your grandmother’s kitchen have those old school two-tone brown tiles? Did you grow up in another country, where the air felt different and the smell of tomatoes reminded you of Sundays? Does your bedroom have patterned fabric hanging from the walls and a bleached patch on the floor from when you spilled nail polish remover? Perhaps your scene is a sporting field – describe the grazed knees, the sliced oranges and the mums on the sideline nursing babies. The more unique yet well described the details are, the more tangible your setting is.

Again, it comes back to: write about what you know.

How much time has elapsed?

You want to consider whether your creative piece is focused on a small slot of ordinary time, or is it covering years in span? Are you flashing back between the past and the present? Some of the most wonderful short stories focus on the minutiae that is unique to ordinary life but is perpetually overlooked or underappreciated. By this I mean, discovering that new isn’t always better may be the product of a character cooking their grandmother’s recipe for brownies (imagine the imagery you could use!). Discovering that humans are all one and the same could come from a story based on one single shift at a grocery store, observing customers. Every day occurrences offer very special and overlooked discoveries.

You could create a creative piece that actually spans the entire life span of someone (is this the life span of someone who lived to 13 years old or someone who lived until 90 years old?). Else, you could create a story that compares the same stage of life of three different individuals in three different eras. Consider how much time you want to cover before embarking on your creative journey.

Show, don’t tell:

The best writers don’t give every little detail wrapped up and packaged, ready to go. As a writer, you need to have respect for your reader in that you believe in their ability to read between the lines at points, or their ability to read a description and visualise it appropriately.

“I was 14 at the time. I was young, vulnerable and naïve. At 14 you have such little life experience, so I didn’t know how to react.”

This is boring because the reader is being fed every detail that they could have synthesised from being told the age alone. To add to the point of the age, you could add an adjective that gives connotations to everything that was written in the sentence, such as “tender age of 14.” That’s a discretionary thing, because it’s not necessary. When you don’t have to use extra words: probably don’t. When you give less information, you intrigue the reader. There is a fine line between withholding too much and giving the reader the appropriate rope for them to pull. The best way to work out if you’re sitting comfortably on the line is to send your creative writing to someone, and have them tell you if there was a gap in the information. How many facts can you convey without telling the reader directly? Your markers are smart people, they can do the work on their end, you just have to feed them the essentials.

Here are some examples of the difference between showing and telling.

Telling: The beach was windy and the weather was hot. Showing: Hot sand bit my ankles as I stood on the shore.

Telling: His uniform was bleakly coloured with a grey lapel. He stood at attention, without any trace of a smile. Showing: The discipline of his emotions was reflected in his prim uniform.

Giving your character/persona depth

If your creative writing involves a character – whether that be a protagonist or the persona delivering your imaginative speech – you need to give them qualities beyond the page. It isn’t enough to describe their hair colour and gender. There needs to be something unique about this character that makes them feel real, alive and possibly relatable. Is it the way that they fiddle with loose threads on their cardigan? Is it the way they comb their hair through their fingers when they are stressed? Do they wear an eye patch? Do they have painted nails, but the pinky nail is always painted a different colour? Do they have an upward infliction when they are excited? Do the other characters change their tone when they are in the presence of this one character? Does this character only speak in high/low modality? Are they a pessimist? Do they wear hand-made ugly brooches?

Of course, it is a combination of many qualities that make a character live beyond the ink on the page. Hopefully my suggestions give you an idea of a quirk your character could have. Alternatively, you could have a character that is so intensely normal that they are a complete contrast to their vibrant setting?

Word Count?

Mine was 1300. I am a very fast writer in exam situations. Length does not necessarily mean quality, of course. A peer of mine wrote 900 words and got the same mark as me. For your first draft, I would aim for a minimum of 700 words. Then, when you create a gauge for how much you can write in an exam in legible handwriting, you can expand. For your half yearly, I definitely recommend against writing a 1300 word creative writing unless you are supremely confident that you can do that, at high quality, in 40 minutes (perhaps your half yearly exam isn’t a full Paper 1 – in which case you need to write to the conditions).

There is no correct word count range. You need to decide how many words you need to effectively and creatively express your ideas about discovery.

Relating to a stimulus

Since 2010, Paper 1 has delivered quotes to be used as the first sentence, general quotes to be featured anywhere in the text and visual images to be incorporated. Every year, there has been a twist on the area of study concept (belonging or discovery) in the question. In the belonging stage, BOSTES did not say “Write a creative piece about belonging. Include the stimulus ******.” Instead, they have said to write an imaginative piece about “belonging and not belonging” or to “Compose a piece of imaginative writing which explores the unexpected impact of discovery.” These little twists always come from the rubric, so there isn’t really any excuse to not be prepared for that!

If the stimulus is a quote such as “She was always so beautiful” there is lenience for tense. Using the quote directly, if required to do that, is the best option. However, if this screws up the tense you are writing in, it is okay to say “she is always so beautiful.” (Side note: This would be a really weird stimulus if it ever occurred.) Futhermore, gender can be substituted, although also undesirable. If the quote is specified to be the very first sentence of your work: there is no lenience. It must be the very first sentence.

As for a visual image, the level of incorporation changes. Depending on the image, you could reference the colours, the facial expressions, the swirly pattern or the salient image. Unfortunately, several stimuli from past papers are “awaiting copyright” online and aren’t available. However, there are a few, and when you have an imaginative piece you should try relate them to these stimuli as preparation.

The techniques:

Don’t forget to include some techniques in there. You study texts all year and you know what makes a text stand out. You know how a metaphor works, so use it. Be creative. Use a motif that flows through your story. If you’re writing a speech, use imperatives to call your reader to action. Use beautiful imagery that intrigues a reader. Use amazing alliteration (see what I did there). Avoid clichés like the plague (again…see what I did) unless you are effectively appropriating it. In HSC creative writing, you need to show that you have studied magnificent wordsmiths, and in turn, you can emulate their manipulation of form and language.

Some quirky prompts:

Click here if you want 50 quirky writing prompts – look for the spoiler in the post!

How do I incorporate Discovery?

If you click here you will be taken to an AOS rubric break down I have done with some particular prompts for HSC creative writing.

Part two: Editing and Beyond!

This next part is useful for your HSC creative writing when you have some words on the page waiting for improvement.

Once you’ve got a creative piece – or at least a plot – you can start working on how you will present this work in the most effective manner. You need to be equipped with knowledge and skill to refine your work on a technical level, in order to enhance the discovery that you will be heavily marked on. By synthesising the works of various genius writers and the experiences of HSC writers, I’ve compiled a list of checks and balances, tips and tricks, spells and potions, that will help you create the best piece of HSC creative writing that you can.

Why should you critique your writing and when?

What seems to be a brilliant piece of HSC creative writing when you’re cramming for exams may not continue to be so brilliant when you’re looking at it again after a solid sleep and in the day light. No doubt what you wrote will have merit, perhaps it will be perfect, but the chances lean towards it having room for improvement. You can have teachers look at your writing, peers, family, and even me here at ATAR Notes. Everyone can give their input and often, an outsider’s opinion is preciously valuable. However, at the end of the day this is your writing and essentially an artistic body that you created from nothing. That’s special. It is something to be proud of, and when you find and edit the faults in your own work, you enhance your writing but also gain skills in editing.

Your work should be critiqued periodically from the first draft until the HSC exams. After each hand-in of your work to your teacher you should receive feedback to take on board. You have your entire year 12 course to work on a killer creative writing piece. What is important is that you are willing to shave away the crusty edges of the cake so that you can present it in the most effective and smooth icing you have to offer. If you are sitting on a creative at about 8/15 marks right now (as of the 29/02/2016), you only have to gain one more mark per month in order to sit on a 15/15 creative. This means that you shouldn’t put your creative to bed for weeks without a second thought. This is the kind of work that benefits from small spontaneous bursts of editing, reading and adjusting. Fresh eyes do wonders to writer’s block, I promise. You will also find that adapting your creative writing to different stimuli is also very effective in highlighting strengths and flaws in the work. This is another call for editing! Sometimes you will need to make big changes, entirely re-arranging the plot, removing characters, changing the tense, etc. Sometimes you will need to make smaller changes like finely grooming the grammar and spelling. It is worth it when you have an HSC creative writing piece that works for you, and is effective in various situations that an exam could give you.

The way punctuation affects things:

I’ll just leave this right here…

Consistency of tense:

Are your sentences a little intense?

It is very exhausting for a responder to read complex and compound sentences one after the other, each full of verbose and unnecessary adjectives. It is such a blessed relief when you reach a simple sentence that you just want to sit and mellow in the beauty of its simplicity. Of course, this is a technique that you can use to your advantage. You won’t need the enormous unnecessary sentences though, I promise. “Jesus wept.” This is the shortest verse in the Bible (found John 11:35) and is probably one of the most potent examples of the power of simplicity. The sentence only involves a proper noun and a past-tense verb. It stands alone to be very powerful. It also stands as a formidable force in among other sentences. Sentence variation is extremely important in engaging a reader through flow.

Of course, writing completely in simple sentences is tedious for you and the reader. Variation is the key in HSC creative writing. This is most crucial in your introduction because there is opportunity to lose your marker before you have even shown what you’re made of! Reading your work out loud is one of the most effective ways to realise which sentences aren’t flowing. If you are running out of breath before you finish a sentence – you need to cut back. Have a look here and read this out loud:

The grand opening:

Writer’s Digest suggested in their online article “5 Wrong Ways to Start a Story” that there are in fact, ways to lose your reader and textual credibility before you even warm up. It is fairly disappointing to a reader to be thrown into drastic action, only to be pulled into consciousness and be told that the text’s persona was in a dream. My HSC English teacher cringed at the thought of us starting or resolving our stories with a dream that defeats everything that happened thus far. It is the ending you throw on when you don’t know how to end it, and it is the beginning you use to fake that you are a thrilling action writer. Exactly what you don’t want to do in HSC creative writing.

Hopefully neither of these apply to you – so when Johnny wakes up to realise “it was all just a dream” you better start hitting the backspace.Students often turn to writing about their own experiences. This is great! However, do not open your story with the alarm clock buzzing, even if that is the most familiar daily occurrence. Writer’s Digest agrees. They say, “the only thing worse than a story opening with a ringing alarm clock is when the character reaches over to turn it off and then exclaims, “I’m late.””So, what constitutes a good opening? If you are transporting a reader to a different landscape or time period than what they are probably used to, you want to give them the passport in the very introduction otherwise the plane to the discovery will leave without them. This is your chance to grab the marker and keep them keen for every coming word. Of course, to invite a reader to an unfamiliar place you need to give them some descriptions. This is the trap of death! Describing the location in every way is tedious and boring. You want to respect the reader and their imagination. Give them a rope, they’ll pull.However, if your story is set in a familiar world, you may need to take a different approach. These are some of my favourite first lines from books (some I have read, some I haven’t). I’m sure you can appreciate why each one is so intriguing.

“Call me Ishmael.” -Herman Melville, Moby Dick.

This works because it is simple, stark, demanding. Most of all, it is intriguing.

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” – George Orwell, 1984.

Usually, bright and sunny go together. Here, bright and cold are paired. What is even more unique? The clocks tick beyond 12. What? Why? How? You will find out if you read on! See how that works?

“It was a pleasure to burn.” Ray Bradbury, Farenheit 451.

This is grimacing, simple, intriguing.

“I write this sitting in the kitchen sink.” -Dodie Smith, I Capture the Castle.

Already I’m wondering why the bloody hell is this person in a kitchen sink? How did they get there? Are they squashed? This kind of unique sentence stands out.

“In case you hadn’t noticed, you have a mental dialogue going on inside your head that never stops. It just keeps going and going. Have you ever wondered why it talks in there? How does it decide what to say and when to say it?” – Michael A Singer, The Untethered Soul: The Journal Beyond Yourself.

This works because it appeals to the reader and makes them question a truth about themselves that they may have never considered before.

“Mr and Mrs Dursley, of number four Pivet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.” JK Rowling, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

Who was questioning that they weren’t perfectly normal? Why are they so defensive and dismissive? I already feel a reaction to the pompous nature of the pair!

Resolving the story well!

There are so many ways to end stories. SO many. What stories have ended in a very efficient way for you? Which stories left you wanting more? Which stories let you down?

Because you are asked to write about discovery in HSC creative writing, you want the ending to be wholesome. This means, you need your marker to know that the ending justifies the discovery. You can’t leave your marker confused about whether or not the discovery had yet occurred because this may jeopardise your marks. If your discovery is an epiphany for the reader, you may want to finish with a stark, stand alone sentence that truly has a resonating effect. If your story is organised in a way that the discovery is transformative of a persona’s opinions, make sure that the ending clearly justifies the transformation that occurred. You could find it most effective to end your story with your main character musing over the happenings of the story.

In the pressure of an exam, it is tempting to cut short on your conclusion to save time. However, you MUST remember that the last taste of your story that your marker has comes from the final words. They simply cannot be compromised!

George Orwell’s wise words:

Looking for a bit of extra help?

We also have a free HSC creative writing marking thread here!

Don’t be shy, post your questions. If you have a question on HSC creative writing or anything else, it is guaranteed that so many other students do too. So when you post it on here, not only does another student benefit from the reply, but they also feel comforted that they weren’t the only one with the question!

Featured Articles

Your Common Study Questions Answered!

Need some advice on how to study? Confused on the best ways to approach certain topics? Here are your common study questions answered. Is it better to handwrite or type notes? B...

What does it actually mean to “study smart”?

When I was in high school, I was often told to “study smart, not hard”. It’s a common high school trope and, to be completely frank, I didn’t know what it m...

The benefit of asking questions in high school

For whatever reason, asking questions through class can actually be pretty tough. Maybe you feel embarrassed about not knowing the answer. Maybe you haven’t yet developed rap...

How to study in high school - the 'dos' and 'don'ts'

As we know, different students study in different ways, and that’s totally fine. This article isn’t prescriptive - we’re not telling you what must be done - but w...

Sponsored by the Victorian Government - Department of Education

Looking for a career where you can make a difference?

With scholarships, incentives, supports and more, there's never been a better time to become a teacher.

- How to Write a Band 6 Creative?

HSC Module B: Band 6 Notes on T.S. Eliot’s Poetry

Full mark band 6 creative writing sample.

- Uncategorized

- creative writing

- creative writing sample

Following on from our blog post on how to write creatives , this is a sample of a creative piece written in response to:

“Write a creative piece capturing a moment of tension. Select a theme from Module A, B or C as the basis of your story.”

The theme chosen was female autonomy from Kate Chopin’s The Awakening (Module C prescribed text).

This creative piece also took inspiration from Cate Kennedy’s Whirlpool .

Summer of 2001

For a moment, the momentum she gained galloping in the blossoming garden jolted, and she deflated like a balloon blown by someone suddenly out of breath. A half-smile, captured by the blinking shutter.

Out spluttered the monochrome snapshot. A bit crumpled. A little too bright.

Two dark brown braids, held by clips and bands and flowers, unruliness constrained. The duplicate of her figure came out in the Polaroid sheltered between a stoic masculine figure, and two younger ones just as unsmiling as their father. The mother stood like a storefront mannequin, the white pallor of her skin unblemished by her lurid maroon blush.

Father told the children that their mother was sick. That’s all. Having nightmares about their grandmother who left mother as a child. “Ran off,” he had said, and his nose twitched violently. “Left a family motherless, wifeless.”

I run, too, the girl had thought excitedly. When she ran, she could see the misty grey of the unyielding lamp-posts, and hear the same grunts and coos of pigeons unable to sing, melodies half-sang, half-dissonant. Why don’t they ever sing? Like the parrots and the cockatoos and lorikeets?

Out spluttered another photograph.

Void of the many distresses as analogous to adulthood, her face brimmed with childlike innocence, untroubled by the silhouettes of her father and brothers.

Spring of 2012

“Can you take a picture for us?”

She was on the other side of the camera, and for a moment she was lost in a transitory evocation of her childhood. The soft blush of the children and the hardened faces of the adults. The forced tightness of their figures. They too looked happy, she supposed, amidst the golden sand and waves that wash the shore.

Away from the flippancy of clinking wine glasses and high-pitched gossip, she felt could almost hear the ticking seconds of each minute, each hour.

She returned the phone to the family.

How still they stood! The unmoving figures on the compact screen. A snapshot of the present that has instantaneously become the past. If only her childhood could extend infinitely to her present, and future, then she would again experience that luscious happiness that seemed to ebb with age. The warm embrace by her mother. The over-protectiveness of her father. How strange it was, to think that she had once avoided both.

But no matter.

She can’t return to the past. All she could do is reminisce about it. It was futile, she knew. The physician had told her so.

“Think about the present!” he had said. “You live too much in the past! Talk to your family! Your husband!”. After a glance at the confounded face, he added, “You grew up with caring brothers, I believe?”.

She nodded.

“Surely,” he elongated the word so that it extended into the unforeseeable future, “they must understand.”

No, they didn’t, she thought. Not after their Marmee left.

She remembered how perfect her family had been, captured undyingly on that monochrome photograph. Her brothers and her, mother and father. Yes, what a perfect family. Oh, how the opened eye of the camera would watch apathetically as they fastened together, to perfection.

It all fell apart five weeks afterwards, as they listened her father’s monotonous voice reading the last remnant of their mother – a note declaring how their perfection had compromised her, been too stifling, just as that Summer’s humidity had been. Wasn’t that what it meant to be a family, she had thought, to let give you to others willingly for the happiness of the entire family?

Absentmindedly, the grown woman picked up a bayberry branch and drew circles upon circles on the siliceous shore. Where it touched, the sand darkened and lightened again as the water rose.

The ultimatum of my life, she proposed to herself, a rebellious dive at sea! Amused by her dramatism, she continued to muse. How simple it would be, washed away and never coming back. Her family now was perfect enough. Big house. Big car. Big parties. Big dreams. But happiness? She thought of the riot of colour and flashing cameras that her husband loved. Oh, how they caused her migraines! And his insistence for her to abandon those childhood passions of hers, strolling amidst sunny afternoons amidst the greenery, only embody their “Marmee” and his “Honey”. How ridiculous!

Her hand halted to a stop.

For a fleeting moment, the continuum of her oblivion terminated, the angular momentum her hand gained by drawing those perfect circles on the shore jolted. She inflated with the sudden realisation of what she had written on the sand.

Short, and incomplete without the usual Jennings that followed it. But her name nonetheless.

Yes, those ephemeral imprints of her name will be washed away by the infinite rise and fall of the tide. But she still watched. So that when the present became the past, she would still have a snapshot in her memory to hold on to.

She knew she could not go, just like her name. Into the ocean and never come back. She could not possibly go like her mother, who when she was eleven, left a family without a mother and husband without a wife. She could not possibly go like her mother, who left a daughter crushed by the milliseconds of perfection that succumbs so soon after the click of a camera.

With a long sigh, she turned back and the sea becoming a reverberating picture of her past. Intangible, yet outrageously glorious…

11th March, 2015

The mother, on her phone, manicured fingernails swiping the screen absentmindedly. Across the room, the father looked concerned at both the inattentiveness of his wife and the sounds of clanking metal emanating from the cameramen.

“We’re ready, Mrs Jennings,” said one of them, “Please get into position for the family photo!”

The opened eye of the camera watched as the family fastened itself together, the rosy-cheeked daughter and son, the unison of the family creating the epitome of perfection. They smiled vibrant smiles, posed jovially at the flashing lights.

But immediately after the click of the shutters, they all fell apart, insubstantial as a wish.

- How our ex-student and current tutor transferred to a Selective School

- HSC Module B: Band 6 Notes on T.S. Eliot's Poetry

- How to Write a Band 6 Discursive?

Related posts

JP English Student Successes: How Colette Scored within the top 10% band for writing in the Selective Exam

James Ruse Graduate’s Tips on How to Write An Engaging Narrative Opening

James Ruse Graduate’s Tips on How to “Show, Not Tell” in Creative Writing

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

- OC Test Preparation

- Selective School Test Preparation

- Maths Acceleration

- English Advanced

- Maths Standard

- Maths Advanced

- Maths Extension 1

- English Standard

- Maths Extension 2

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

- UCAT Exam Preparation

Select a year to see available courses

- English Units 1/2

- Maths Methods Units 1/2

- Biology Units 1/2

- Chemistry Units 1/2

- Physics Units 1/2

- English Units 3/4

- Maths Methods Units 3/4

- Biology Unit 3/4

- Chemistry Unit 3/4

- Physics Unit 3/4

- UCAT Preparation Course

- Matrix Learning Methods

- Matrix Term Courses

- Matrix Holiday Courses

- Matrix+ Online Courses

- Campus overview

- Castle Hill

- Strathfield

- Sydney City

- Year 3 NAPLAN Guide

- OC Test Guide

- Selective Schools Guide

- NSW Primary School Rankings

- NSW High School Rankings

- NSW High Schools Guide

- ATAR & Scaling Guide

- HSC Study Planning Kit

- Student Success Secrets

- Reading List

- Year 6 English

- Year 7 & 8 English

- Year 9 English

- Year 10 English

- Year 11 English Standard

- Year 11 English Advanced

- Year 12 English Standard

Year 12 English Advanced

- HSC English Skills

- How To Write An Essay

- How to Analyse Poetry

- English Techniques Toolkit

- Year 7 Maths

- Year 8 Maths

- Year 9 Maths

- Year 10 Maths

- Year 11 Maths Advanced

- Year 11 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Standard 2

- Year 12 Maths Advanced

- Year 12 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Extension 2

Science guides to help you get ahead

- Year 11 Biology

- Year 11 Chemistry

- Year 11 Physics

- Year 12 Biology

- Year 12 Chemistry

- Year 12 Physics

- Physics Practical Skills

- Periodic Table

- VIC School Rankings

- VCE English Study Guide

- Set Location

Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

How to Write a Craft of Writing Creative in the HSC | The Module C Checklist ✓

Are you stressed about tackling the new Craft of Writing HSC questions? Don't be, we've put our experience with syllabus changes into giving you a Module C exam checklist.

Get free study tips and resources delivered to your inbox.

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

" * " indicates required fields

You might also like

- Natalie’s Hacks: How I Scored An ATAR of 99.95 Without Math

- How to Balance the UCAT And The HSC | 3 Must-Know Preparation Tips

- Journey to a 99.60 ATAR: Josh’s Steps to Tackling Silly Mistakes

- Literary Techniques: Metaphor

- Film Techniques: Lighting

Related courses

Vce english units 3 & 4.

Do you worry about producing a creative piece in an exam? What do you need to do for a Craft of Writing creative, anyway? Matrix has been around for 19 years, and over this time we’ve seen quite a few syllabus changes and helped thousands of students succeed with a new syllabus.

So, in this post, we’re going to share some of that knowledge and show you how to write a Craft of Writing creative for the HSC so you can make sure you ace it.

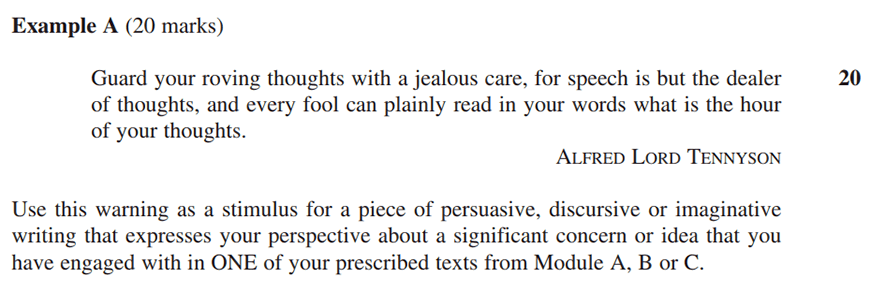

What will a Module C question look like for the HSC?

The new syllabus has brought with it a new Module and types of questions for Paper 2. Gone are the days of memorising a creative and regurgitating it around a stimulus image or phrase as part of Paper 1.

Instead, there are now a variety question types that you can be confronted with as part of Paper 2. Fortunately, the folks at NESA have provided you with a sample HSC English Advanced Paper 2 which showcases the three new types of questions they can choose from.

What sorts of questions might you face? Let’s take a look:

Broad task – Type A Question (1 part)

This question is relatively straightforward and similar to the questions you’ll find in past papers from the old curriculum. You are asked to write a persuasive, discursive, or imaginative piece in response to a quotation from a famous figure.

This is an open-ended question and you have a lot of options at your disposal in how you respond to it. You would be expected to produce one coherent piece: a complete imaginative piece or essay (either persuasive or discursive).

As these questions have led to students memorising responses in the past, NESA may tend away from this style of questions in future HSCs… or they may not.

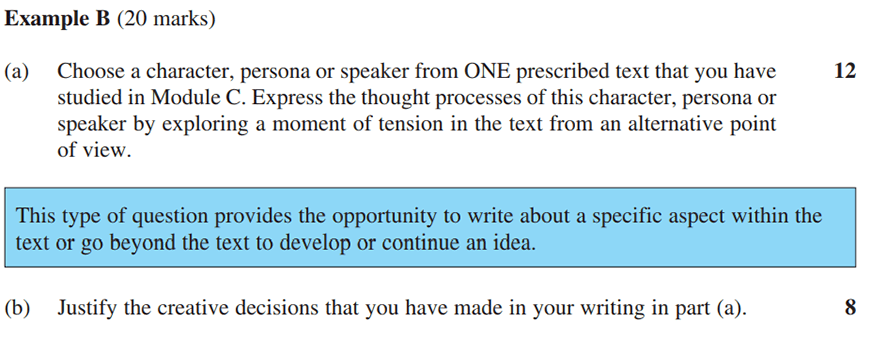

Creative reimagining – Type B Question (2 parts)

This challenging question has two distinct parts:

- A creative reimagining worth 12 marks

- A justification worth 8 marks

The first part (a) requires you to rewrite a pivotal moment from a Module C text from the perspective of a different perspective – a minor character or somebody other than the narrator. This question asks you to “explor[e] a moment of tension ” from the text, but it could equally ask you to explore a moment of affection , fear , or action . This potential for variation makes it impossible to prepare a response in advance.

To do well in this type of task you will need to know your Module C texts well and practise responding to a variety of similar questions.

The second part (b) of this question requires you to write a justification.

NESA defines “justify” as asking students to “[s]upport an argument or conclusion.”

This means that you must explain why you have made your creative decisions. These decisions could include:

- Why you chose to write from a certain perspective (1st, 2nd, 3rd person)

- What led you to choose the character whose perspective you conveyed

- The intent behind using certain literary or rhetorical devices

- Why you structured your response in a particular way

This response will be wholly contingent on what you write for Part A, meaning you can’t prepare a response. The only way to prepare for this sort of question is to write practice responses with a variety of specific instructions.

When writing a justification, you need to be objective and analyse your own writing. You may need to include analysis of your prescribed text to justify your decisions to the marker.

When practising these question types, you should pay attention to the amounts for each section. Clearly, your creative piece is worth more marks and, therefore, more time than the justification. Consider spending 60% of your time on the creative and 40% on the justifcation.

It is quite possible that you could be asked to write about any text from any Module. For example, they might ask you to write about the perspective of a character from a Common Module or Module B text.

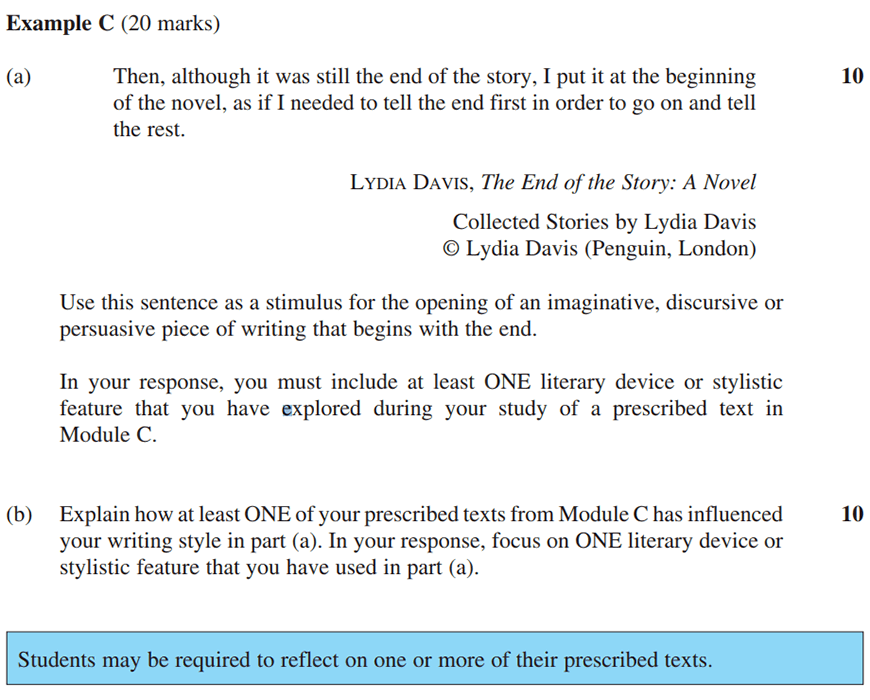

Stylistic response – Type C Question (2 parts)

This question also has two parts:

- A piece of imaginative, discursive, or persuasive piece of writing worth 10 marks

- An explanation of how a text has influenced your response worth 10 marks

The first part (a) requires you to compose the opening of a piece of writing. This opening must begin in medias res – beginning with the end. You must include a stylistic device from a Module C text in your response. You could be asked to discuss a prescribed text from any Module in your response.

The second part (b) requires you to explain your choices from part (a). NESA defines “explain” as asking students to “Relate cause and effect; make the relationships between things evident; provide why and/or how.” This means you need to explain:

- How you have been influenced by the prescribed text. What features of structure, style, tone, or technique did you find inspiring?

- What did you find effective about that composer’s use of a particular literary device (technique, form, or structural feature)?

- How have you tried to employ that in your response to the question?

To do well in this section, you’ll need to provide analysis of the prescribed text and your own. It is important when writing a response to this that you are objective when evaluating the text’s use of a device and your subsequent use.

Unlike the Type C question, you should spend equal time on each of these parts as they are worth equal marks.

As you can see, these Module C questions are very challenging and require you to practise your writing craft rather than memorising a response.

So how do you deal with this in an exam?

Let’s have a look!

The Module C Checklist: How to write a Craft of Writing creative in the HSC

When you’re working under timed conditions, you really want to think about working systematically to ensure that you tick all the right boxes.

Because we’ve been doing this for close to 20 Years, at Matrix we’ve realised that there are some steps students can take to make these tasks easier. So, to help you be systematic in your Module C responses, we’ve put together this Craft of Writing checklist for you to work through.

✓ 1. Read and unpack the question

This sounds like a no brainer, right? Well, it’s actually really important to do. And many students rush and misinterpret the question.

In the past, the worry was that you’d discuss the wrong number of texts, or mix up compare and contrast. Now, with these two part questions, paying exact attention to what the question asks you to do is essential.

So, what do you need to think about when reading and unpacking the question?

You want to know your key terms and their definitions. We’ve got a handy copy of NESA’s glossary of key words, here . You want to know all of these, especially the verbs. Every verb that NESA uses in a question has a very specific meaning.

For example, consider these three verbs:

- Analyse : Identify components and the relationship between them; draw out and relate implications

- Assess : Make a judgement of value, quality, outcomes, results or size

- Evaluate : Make a judgement based on criteria; determine the value of

Analyse , assess , and evaluate might seem synonymous, but they have quite different connotations. Analyse wants you to think about how things work together. Assess wants you to make a subjective judgement about somethings quality or worth. Evaluate wants you to make a judgement, but this time by thinking about things against a criteria or scale.

You want to identify the requirements of the question. This is especially important for two part questions.

Ask yourself, “what is the question asking me to do?” If it is an imaginative task, make sure you write according to what it asking you to do. If you need to rewrite something from a different perspective, don’t compose something unrelated. If you have to utilise a technique or form from a prescribed text, ensure you follow the instructions concerning which Module and technique. Questions that specify a creative re-imagining or the use of a technique will likely also mandate that you write in a specific style or tone or genre.

A good way to make sure you’re paying attention to what the question is asking you is to underline the key words in the question:

(a) Use this sentence as a stimulus for the opening of an imaginative, discursive or persuasive piece of writing that begins with the end .

In your response, you must include at least ONE literary device or stylistic feature that you have explored during your study of a prescribed text in Module C .

(b) Explain how at least ONE of your prescribed texts from Module C has influenced your writing style in part (a) . In your response, focus on ONE literary device or stylistic feature that you have used in part (a) .

In the above question, it would be possible to miss the instruction to “begin with the end” or use a text from a different Module than the one specified.

✓ 2. Plan your response

Once you’ve read the question through a few times and unpacked what is asking you to do, take a breath and think for a minute.

You want to let yourself plan things out, for each part of the response, before you get stuck in. Module C tasks are about you producing quality pieces of writing, not huge amounts of text.

A concise well planned piece that clearly addresses the question is always going to score higher than something rambling and rushed.

You only have 40 minutes to answer the question and its parts. So, how should you plan?

Sketch out the following things in a mind map or as dot-points.

For the imaginative, persuasive, or discursive piece:

- Choose your structure – what perspective will you use,

- If you’re writing a full 20 mark response, sketch out your 2-3 part plot structure or your essay structure

- If you’re responding two a two part question, think about the full plot of your narrative and then decide where you’ll stop

- Note the technique or device you need to employ (eg. Do you need to begin in medias res?)

- Make note of any other requirements you need to consider such as tone or exploring a moment of tension

For the rationale or justification:

- Note down what aspect of the imaginative, persuasive, or discursive response you need to discuss

- Plot out the structure of your response (mini essay, single paragraph, etc)

- Make note which prescribed text you need to cite

- Jot down your example(s) from the prescribed text

Now you have a plan, you can start writing your response.

The first thing you’ll need to do is develop the structure…

✓ 3. Structure

What do we mean by structure?

Structure can relate to the perspective you use in your imaginative piece. That is, is it written from the:

- 1st person : I, me

- 2nd person : You

- 3rd person : He, she, it, they

- Or do you need to use several different perspectives (such as the 2018 HSC Paper 1 creative task )

Structure can also refer to how the piece is put together:

- Will it begin in the middle or end and jump around in time (in medias res)?

- Do you intend it to be linear or does it jump forward in time

- Might it be structured as a monologue

- Will you follow a three act structure or is it intertwining different narrative threads?

If you are writing a discursive or persuasive piece, the considerations for structure will include:

- Paragraph structure – integrated, divided

- Paragraph length – consistent, varied for style and effect

- Use of examples , evidence , and anecdotes

Finally, you’ll need to consider the structure of your rationale or justification:

- Do you need to employ a formal structure – introduction , body , conclusion ?

- Does it need to be written in a formal tone ?

- Will you need to include examples ?

- Do you need to compare your written piece from part (a) with a prescribed text?

As you can see, there are quite a few considerations to bear in mind when thinking about structure. You want to be confident in making these decisions so that you can make them quickly.

Matrix students get practice responding to these types of tasks during the Craft of Writing bootcamps . You should defintely ensure that you practice these tasks under timed conditions.

✓ 4. Choose your technique(s)

If you have a task like Example C above that asks you to “include at least ONE literary device or stylistic feature that you have explored during your study of a prescribed text in Module C,” you’ll need to choose a technique.

You want to think carefully about what technique you’ll use.

For a task like this, it is not enough to just toss in a metaphor or symbol to show you can use them.

Instead, you need to have a specific intent behind your decision AND you need to be able to relate it to the prescribed text you have been inspired by. You’ll need to think about this ahead of time.

As part of your analysis for all of your different Modules, you must take the time to make a list of two or three techniques that you liked from each prescribed text that you study.

For each technique that pick note down:

- An example of how the composer used it

- Why you think it is powerful, effective, or influential

- If possible, a practice example of you using it

Preparing for the HSC and Trial HSC in this way will allow you to plan ahead and not caught out on the day.

✓ 5. Write to purpose and audience

Your instructions for the task will give you information about who you are writing for – your audience – and, in some cases, what the purpose of your piece should be.

But what does this mean, exactly?

NESA defines these terms as:

- Audience : The intended group of readers, listeners or viewers that the writer, designer, filmmaker or speaker is addressing.

- Purpose : The purpose of a text, in very broad terms, is to entertain, to inform or to persuade different audiences in different contexts. Composers use a number of ways to achieve these purposes: persuading through emotive language, analysis or factual recount; entertaining through description, imaginative writing or humour, and so on.

What does this mean for you?

When you write, you need to make a decision about who you’re writing for. This means that if you are writing a persuasive or discursive piece, you should assume that you are writing for an educated audience who are young adults.

If you’re writing an imaginative piece, you want to assume that the audience will be familiar with whatever genre you choose to write in. Or, if you are writing an imaginative recreation, you should assume that the marker is familiar with the prescribed text that you are re-imagining or appropriating.

Matrix English students learn that the purpose of what you write will vary from task to task.

- Imaginative piece : entertain, explore an idea or concern, relate a historical event, etc.

- Discursive piece : explore an idea from different perspectives, but not to persuade the reader

- Persuasive : To convince the reader of a particular point

Each of these tasks will, therefore, require a different approach.

A persuasive response will tend to be a little more formal, a discursive one less formal and even colloquial in places.

An imaginative piece will need to achieve a couple of different purposes at the same time: ie, exploring an idea and entertaining an audience.

The best way to develop confidence writing for purpose and audience is to write practice responses and to seek feedback on them from your peers, teachers, and family. Matrix Craft of Writing Bootcamp students get detailed feedback from their teachers and workshop tutors, as well as peer feedback in class.

✓ 6. Set limits

Rember, you’re not writing a novel. Nor are you writing an essay for publication in an academic journal.

It is quite possible that you won’t even be writing a full response at all. This means that you need to set yourself some limits about how much you will write.

What do we mean by this?

Well, consider the three tasks from the sample paper we looked at earlier. One of them is worth 20 marks for one piece of work, the other 20 have two parts and are worth 12 and 8 marks and 10 and 10 marks respectively. This means that you will need make decisions about how much to produce for each task.

What are some guidelines you can follow? Let’s have a look:

- 20 mark questions : This is is an opportunity for you to write a complete imaginative, persuasive, or discursive response. Whatever you have planned out, you should be able to finish it.

- Do the maths : If one part of a question is worth more marks than the other, then you’re going to need to work on one part more than the other. Try to work on the basis that each mark is worth 2 minutes of your time.If it is a 50/50 split, you’ll spend 20 minutes on each part. If it is 12 and 8 marks, then you’ll spend 24 minutes on one section and 16 on the other.

- Don’t write more than you’re told : Two part questions may well include an instruction about how you should write about. It might be “a moment” from a text or the “opening” of a creative, discursive, or persuasive piece. You won’t get extra marks for writing more than the instructions dictated.

- Only tell part of the story : It’s hard to tell a complete short story in 40 minutes. It’s even harder to do the same in half the time. But you don’t have to. You only need to tell part of the story you’ve developed. Rather than telling the whole three acts that you’ve plotted, just tell one act or even one scene. The ideas is to showcase your craft, rather than tell a complete narrative.

Don’t feel obligated to tell a complete story!

✓ 7. Be concise and clear

Clarity is key!

When you are producing a Module C response it is essential that it is accessible! In addition, you are producing something under strict time conditions, so you won’t have time, or words, to waste.

“But I’m meant to be showing off my literary skills,” you might plead. Well, that doesn’t mean you can be long winded or rambling. Quite the opposite!

An excellent Module C response will always be breviloquent !

Just because you are demonstrating your literary skills, doesn’t mean you should produce unnecessarily long or verbose sentences.

Here are some of the tips for concise writing we share with our students:

- Think before you write! – Don’t write the sentence until you have thought it out first.

- Write for the reader – Ask, yourself what they need to know. Just because you want to write it, doesn’t mean the audience needs to read it.

- Substance over style : Don’t put a sentence or word in for effect (this is called grandiloquence ). A good writer only uses things to convey meaning. Showing that you know big words or can write convoluted sentences, isn’t the same thing as developing meaning through them.

- Don’t be psuedish : Pseuds tend to be obscure in order to demonstrate detailed knowledge of something obscure. You want to be accessible and authoritative. Write about things in a way readers can access and understand.

- Stick to the plan! : Planning allows you to structure things in advance. it may seem like a good idea to go off and chase an interesting idea in the moment, but this can easily make something straightforward and accessible confusing.

- “The road to hell is paved with adverbs!” : We didn’t say that, Stephen King did and he knows a thing or two about successful writing. Adverbs and adjectives often tell rather than showing. King is saying that you want to think about how you can show by using nouns and verbs.

✓ 8. Watch the clock

Finally, exams run to the clock! This makes time management imperative.

When you’re planning, allocate time to each section of paper and each part of a question.

If you are not going to keep to a time limit, you need to make some immediate and important judgements about time!

If you’re running out of time for part of a question worth 10 marks, but have to complete another section worth ten mark., then you should cut to the next section as soon as your time is up.

Your aim is to maximise your marks. Being strict with your time limits is the best way to go about this. Your rationale or justification is going to be an easy to wrap up some marks. So, don’t sacrifice 3 or 4 marks in a rational by chasing 2 extra marks in an imaginative response.

Want to develop your Craft?

The Craft of Writing is a skill developed through practice and feedback. Our Year 12 English Term Course will help you refine your writing skills and learn how to wow your readers.

Start HSC English confidently

Expert teachers, detailed feedback, one-to-one help! Learn from home with Matrix+ Online English courses.

Written by Matrix English Team

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Year 12 English Advanced tutoring at Matrix will help you gain strong reading and writing skills for the HSC.

Learning methods available

Year 12 English tutoring at Matrix will help your child improve their reading and writing skills.

Related articles

2017 HSC Physics Paper Solutions

In this post, we have all the solutions for the 2017 Physics HSC paper!

HSC English Module B Study Guide: Hamlet Part 2 [Free Exemplar Essay]

Read this Band 6 Hamlet essay to clarify your understanding of the Prince of Denmark.

Advanced Mechanics | HSC Physics Study Guide Part 1

Send your Physics marks into orbit with this study guide!

Press Enter to search

A Step-by-Step Guide to Achieving a BAND 6 in Creative Writing

Need to elevate your creative writing? Learn the foolproof formula for writing a full-mark creative response!

a year ago • 6 min read

I think we can all agree creative writing is the hardest and most annoying part of year 12 English. I mean it is so subjective, what's right or wrong?

Well lucky for you, I've been there, a struggling high school student tired of getting bad creative marks. Let me show you how I turned my creative marks around to get a 99+ Atar and how you can too!!

1. READ READ READ!!!

If you keep receiving feedback that says your work is cliché, generic, lacks substance and misuses literary devices the only remedy is reading . There is a reason the syllabus shoves texts down our throats. It's because by understanding the different ways other writers communicate ideas we ourselves become better communicators. By reading outside of your prescribed text you will be exposed to a new set of writing tools your peers wouldn't know about. You can see the recurring writing features well-renowned authors use and most importantly, you can gain worldly inspiration for your own text. Ideally, you want to be reading short stories, discursive and persuasive because that is what the syllabus demands of you.

Some recommendations are;

- Samsa in Love by Murakami

- The Second Bakery Attack by Murakami

- There will come soft rains by Ray Bradbury

- Hills like white elephants by Ernest Hemingway

- The Lottery by Shirely Jackson

Find an author whose writing style you really like and try mimicking their language and syntax in your own work.

2. FIND YOUR PURPOSE

The marking criteria for HSC Module C creative writing to score a Band 6 requires you to:

…consider purpose and audience to carefully shape meaning.

No matter how good your motifs or metaphors are, unless you have a strong and clear message or purpose permeating your writing you will not be able to access band 6 marks. When about to write a short story, discursive or whatever, the first thing I want you to think about is:

What is the message you want to communicate in your writing

When coming up with your purpose/idea don’t overcomplicate it. Pick something simple and personal to you. You want to keep your ideas easily adaptable to different stimuli and something relatable to both yourself and the reader. Some examples are;

- The importance of reading

- The need for belonging and human connections

- The irrational and obsessive nature of love

Think of the texts that you have studied in other modules, What are the ideas and messages being put forward there? You will notice that most of them examine fundamental aspects of human nature and enlighten audiences with a new perspective. That is what you should be doing too!

Let’s say you want to write a story about a child in an immigrant family. If that was the limit of your ‘idea’ you won’t be able to reach a band 6. What is the purpose behind it? Why do you want to explore this experience? A more in-depth idea plan would be "I want to write about a child experiencing alienation within an immigrant family to highlight the importance of culture to a sense of identity and belonging."

3. PLAN YOUR STRUCTURE

Once you have your Band 6 purpose picked out, you now have to figure out how you want to communicate your purpose.

This means picking a writing style (imaginative, persuasive, discursive), developing a main character and conflict, and then selecting the point of view that would explore this character and conflict.

Write in a way that shows an understanding of how the text creates meaning.

There is no right or wrong option here. It is all about how well you understand and can justify your writing decisions (this is important for the reflection). When creating your response you want to be aware of all the features present and how it influences the piece and its meaning.

There are two things that I would recommend to ensure you are on the right track though. For plot structure use the plot pyramid. You will notice all great movies and novels follow this sequence. Why? Because it works every time to engage and compel audiences through the story.

The second thing is to develop dynamic characters. Characters that evolve throughout your story. This doesn't have to be physical, or even a big change. It could be as simple as a haircut or even just a small change in mindset. Essentially you want to show your character to have a change in perspective because that will in turn compel your reader to have that same change. This is easily done if you have carefully thought out your character.

- What is their personal story or background?

- What are their values and beliefs?

- What is the internal conflict they struggle with?

4. WRITE WRITE WRITE

- Use a simple setting (and try to stick to only one scene/setting in your short story you won't have time to delve into more).

- Concentrate on developing one dynamic and 3-dimensional protagonist before you try and introduce other characters. (And only introduce them if they are integral to the storyline. NPC's (or surface-level side characters) do not add value and will only disengage your audience.)

- Show don't tell. For example instead of "I heard footsteps creeping behind me which made me more scared" leave room for the reader's imagination and say "I heard a crunch behind me and my heart turned to sand, rising up into my throat." Instead of "we were really close" say "his smell reminded me of my childhood treehouse."

- Play with word order and vary syntax (punctuation is super important). Many people make the mistake of just using complex sentences, which causes their pieces to feel cluttered and clunky to read. Use short sentences as well to structure tension and emotions.

- The secret of good writing is to simplify and strip every sentence to its cleanest component. Only add the adjectives and descriptions that are integral to your plot line. DON'T GET TOO CAUGHT UP IN FLOWERY LANGUAGE.

5. EDIT AND FEEDBACK

It is highly likely your first draft will not be band 6 material, but that's normal. J.K Rowling took hundreds of drafts to get to the Harry Potter we know and love. And it took me a few drafts before getting a satisfied nod from my English teacher. A Band 6 response will take a series of feedback, edits and rewrites. Show it to your teachers, your friends, and your parents and importantly ask them if they understand the message you are trying to put forward because if they don't the markers reading in a time crunch definitely won't. You don't need expert opinion to make your piece better. You are looking to improve your clarity and communication to everyone .

In addition to this I always find annotating your own writing helps balance and improve the sophistication of literary devices. You should also be reading your piece out loud to help identify syntax and grammatical errors that desperately need to be reworded.

Remember your goal is to use the power of words to communicate a profound idea to the world as engagingly and with as much clarity as possible!!

Want more personalised tips to drastically improve your English mark? A private tutor can make the biggest difference!

Written by KIS Academics Tutor for HSC English, Thao Peli Nghiem Xuan. Thao received an ATAR of 99.55 and is pursuing a Bachelor of Mechanical Engineering at the University Of New South Wales. You can view Thao's profile here and request her as a tutor.

Spread the word

The ultimate 99+ atar 30-day study guide, how to write full mark answers for hsc english short response (with examples), keep reading, how to write a band 6 module b critical study of literature essay, how to respond to short answer questions in vce english language, how to craft a band 6 mod a textual conversations essay, subscribe to our newsletter.

Stay updated with KIS Academics Blog by signing up for our newsletter.

🎉 Awesome! Now check your inbox and click the link to confirm your subscription.

Please enter a valid email address

Oops! There was an error sending the email, please try later

How to Prepare for the HSC Creative Writing Exam

Some people have a natural flair for writing and creative ideas – however, if you’re like most students, completing the HSC creative writing exam in the space of 40 minutes can be a difficult and downright daunting task. Even if you believe don’t have a creative bone in your body, with some careful planning and study you too can ace the HSC creative writing exam – here’s how.

Refer to the syllabus

Just like the rest of your subject exams, a huge factor that determines success in the HSC creative writing section is ensuring you know the syllabus. Refer to the marking criteria to establish what is required of you – especially the study focus you must address (such as belonging or discovery) – and focus on this theme throughout your piece. The stimulus provided should also be a central focus and mentioned throughout your essay – not just haphazardly thrown in at the beginning or end. This way, the markers can clearly see that you have a solid understanding of the concept, as opposed to just memorizing a story word for word.

Know your language techniques

One thing you can learn and practice prior to your HSC creative writing exam that will boost your score greatly is language techniques. It’s best to build up an arsenal of 5-10 techniques that you understand well, and that makes your story more interesting to read. Similes, metaphors, and alliteration – you would have learned all of these and more when analyzing your set texts through the year, so put them to good use! A great one to use is sensory imagery, which makes the reader really feel as though they are in the story and puts to use a rule of any good writing – show, don’t tell.

Develop your characters

The way you develop your character, especially the protagonist in your story, can be a make or break factor for your HSC creative writing piece. It’s not enough to describe their physical appearance or overuse clichés like “troubled teenager” – you need to give them unique qualities that make them both memorable, and relatable in some way.

Write about what you know

The easiest way to succeed in HSC creative writing when you lack confidence in your imaginative ideas is to write about what you already know. Stories are the most organic and authentic when described in accurate detail. The best way to achieve this kind of integrity in your text is to write about an event that you have personally experienced – remembering the vivid aspects of what happened, as well as your emotional response to the situation – and convey this to your marker through your words. Alternatively, you can also write about a topic of interest that you have researched and have a good understanding of.

HSC creative writing focuses on your ability to compose an engaging, grammatically correct and well-structured story that fits in with the area of study and stimulus. Need some help with preparing for the HSC creative writing exam and getting a Band 6? Contact C3 Education and speak to one of our professional HSC tutors today to see how we can help.

Previous Post How to Learn From a Bad School Report and Improve Your Grades

Next post how primary school tutoring can prepare your child for high school, recommended for you.

COPYRIGHT © 2024 C3 EDUCATION GROUP

- – Early Childhood Learning

- – MATHS

- – ENGLISH

- – STEMQUEST

- – CHEMISTRY

- – PHYSICS

- – BIOLOGY

- – ECONOMICS

- English Tutoring

- Maths Tutoring

- Chemistry Tutoring

- Physics Tutoring

- Biology Tutoring

- STEMQuest Tutoring

- Modern + Ancient History

- Legal Studies

- Business Studies

- Economics Tutoring

- ESSAY MARKING

- Online Tutoring

- C3 Childcare Group

- We cover Australia-Wide Curriculum subjects from Pre K to Year 12, and our online tutoring program is delivered to you no matter where you are in Australia.

- Job Opportunities

- Webinar Series

- Find a tutor

- YouTube Channel

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Here's How to Develop A Setting For Your HSC Creative Writing Piece.. Step 4: Develop Your Point of View Which one is better? My journey to the shops was made much less enjoyable by the sweltering heat.I was feeling light-headed and faint.; Your journey to the shops was made much less enjoyable by the sweltering heat which forced you to become light-headed and faint.

HSC Creative writing reflection cheatsheet: with examples!! Completely lost on how to write a reflection for module C HSC? We got you. A step by step guide on how to write the perfect reflection piece, with template structures and exemplars! It really is the ultimate cheatsheet. a year ago • 5 min read

HSC 2021 Module C 'The Craft of Writing' Stimulus. The Module C section in HSC English Adv Paper 2 often varies from year to year. The exam may involve writing both a creative and reflection, or sometimes only a creative piece (worth twenty marks).

How to Write a Creative Text. When it comes to writing creatively, there is no real correct way of constructing or writing a piece. This is because creativity and manipulation of form, structure and techniques is encouraged. However, there are aspects that can be included in your writing, to elevate it to a band 6 level.

HSC Creative Writing: The Guide. HSC creative writing can be a pain for some and the time to shine for others. Getting started is the most difficult part. When you have something to work with, it is simply a matter of moulding it to perfection. When you have nothing, you have a seemingly difficult road ahead.

Following on from our blog post on how to write creatives, this is a sample of a creative piece written in response to: "Write a creative piece capturing a moment of tension. Select a theme from Module A, B or C as the basis of your story." The theme chosen was female autonomy from Kate Chopin's The Awakening (Module C prescribed text).

This challenging question has two distinct parts: A creative reimagining worth 12 marks; A justification worth 8 marks; The first part (a) requires you to rewrite a pivotal moment from a Module C text from the perspective of a different perspective - a minor character or somebody other than the narrator. This question asks you to "explor[e] a moment of tension" from the text, but it ...

This is a question from NESA's HSC English 2019 sample paper. It is asking you to use the quote as a stimulus for a creative writing piece which explores your understanding of a theme presented in one of your prescribed texts throughout the year.. First off the bat, have a look at what the stimulus is telling you.

The marking criteria for HSC Module C creative writing to score a Band 6 requires you to: …consider purpose and audience to carefully shape meaning. ... When creating your response you want to be aware of all the features present and how it influences the piece and its meaning. There are two things that I would recommend to ensure you are on ...

A great one to use is sensory imagery, which makes the reader really feel as though they are in the story and puts to use a rule of any good writing - show, don't tell. Develop your characters. The way you develop your character, especially the protagonist in your story, can be a make or break factor for your HSC creative writing piece.