Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

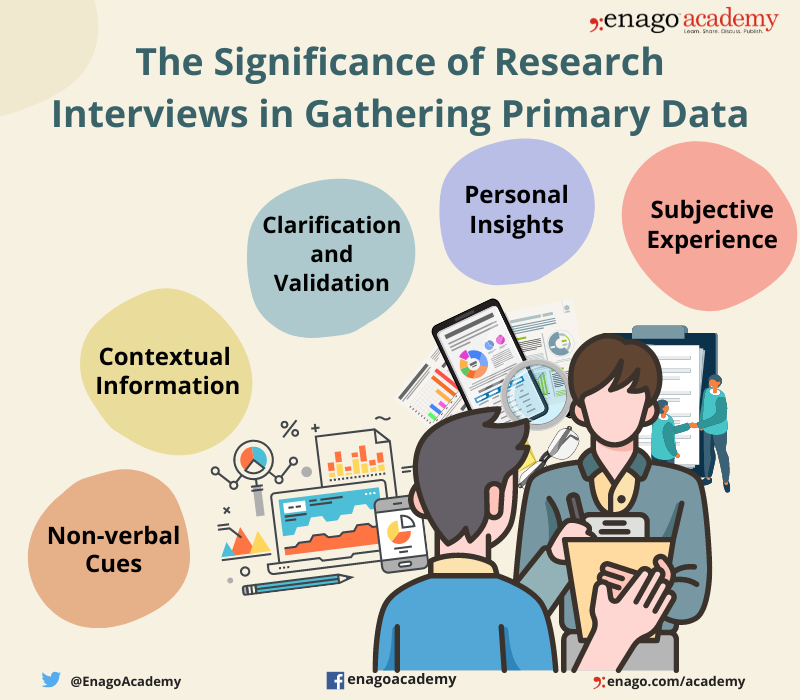

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

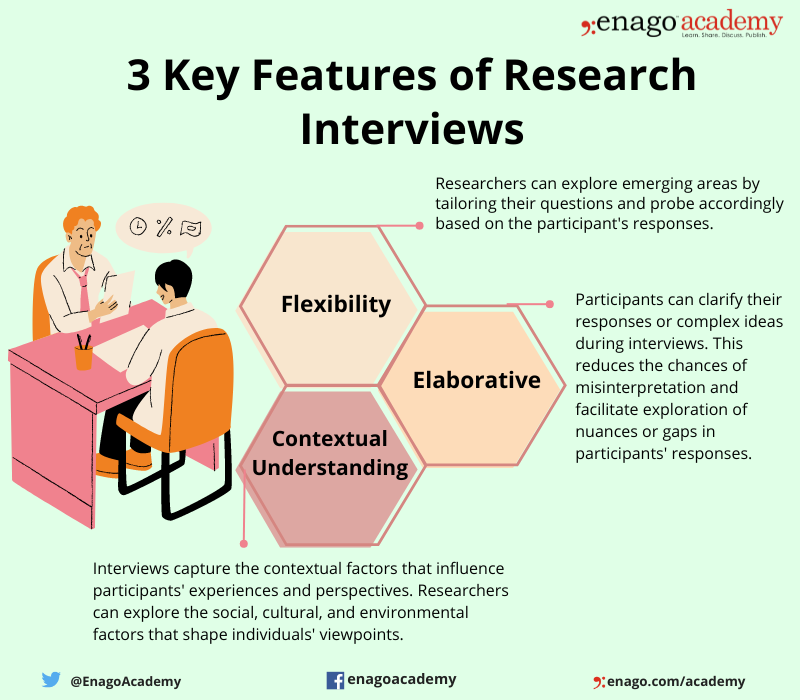

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

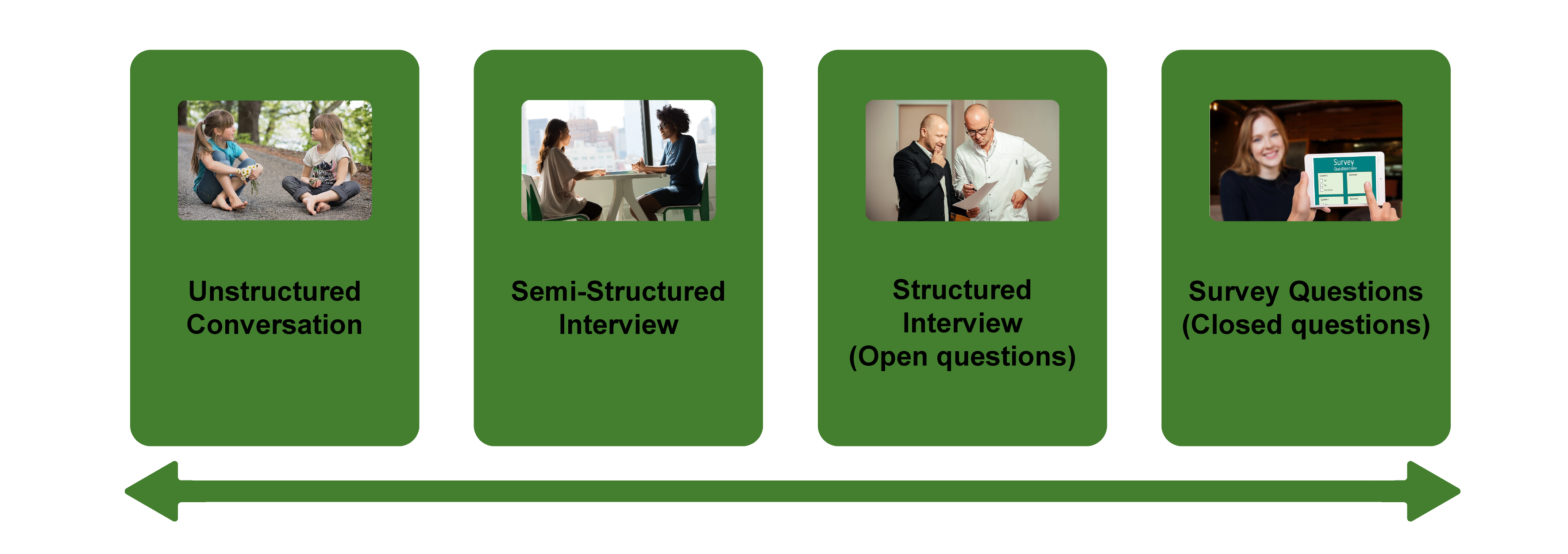

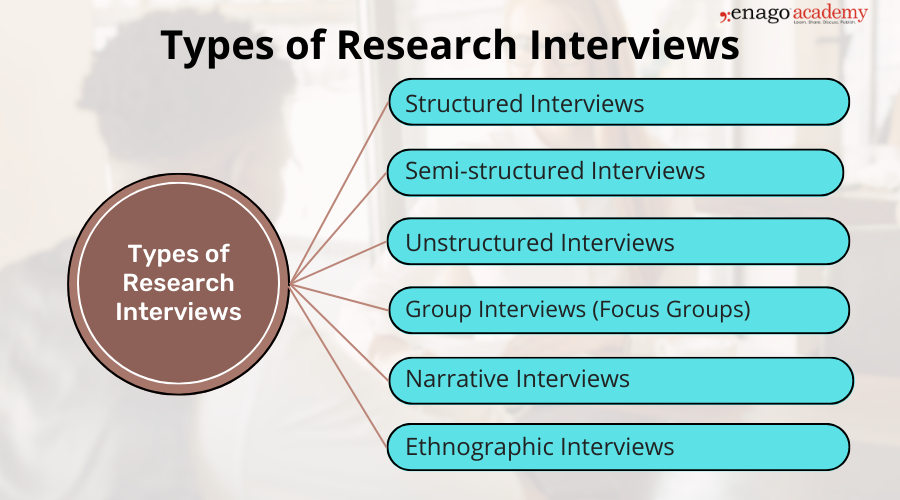

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

The Interview Method In Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Interviews involve a conversation with a purpose, but have some distinct features compared to ordinary conversation, such as being scheduled in advance, having an asymmetry in outcome goals between interviewer and interviewee, and often following a question-answer format.

Interviews are different from questionnaires as they involve social interaction. Unlike questionnaire methods, researchers need training in interviewing (which costs money).

How Do Interviews Work?

Researchers can ask different types of questions, generating different types of data . For example, closed questions provide people with a fixed set of responses, whereas open questions allow people to express what they think in their own words.

The researcher will often record interviews, and the data will be written up as a transcript (a written account of interview questions and answers) which can be analyzed later.

It should be noted that interviews may not be the best method for researching sensitive topics (e.g., truancy in schools, discrimination, etc.) as people may feel more comfortable completing a questionnaire in private.

There are different types of interviews, with a key distinction being the extent of structure. Semi-structured is most common in psychology research. Unstructured interviews have a free-flowing style, while structured interviews involve preset questions asked in a particular order.

Structured Interview

A structured interview is a quantitative research method where the interviewer a set of prepared closed-ended questions in the form of an interview schedule, which he/she reads out exactly as worded.

Interviews schedules have a standardized format, meaning the same questions are asked to each interviewee in the same order (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. An example of an interview schedule

The interviewer will not deviate from the interview schedule (except to clarify the meaning of the question) or probe beyond the answers received. Replies are recorded on a questionnaire, and the order and wording of questions, and sometimes the range of alternative answers, is preset by the researcher.

A structured interview is also known as a formal interview (like a job interview).

- Structured interviews are easy to replicate as a fixed set of closed questions are used, which are easy to quantify – this means it is easy to test for reliability .

- Structured interviews are fairly quick to conduct which means that many interviews can take place within a short amount of time. This means a large sample can be obtained, resulting in the findings being representative and having the ability to be generalized to a large population.

Limitations

- Structured interviews are not flexible. This means new questions cannot be asked impromptu (i.e., during the interview), as an interview schedule must be followed.

- The answers from structured interviews lack detail as only closed questions are asked, which generates quantitative data . This means a researcher won’t know why a person behaves a certain way.

Unstructured Interview

Unstructured interviews do not use any set questions, instead, the interviewer asks open-ended questions based on a specific research topic, and will try to let the interview flow like a natural conversation. The interviewer modifies his or her questions to suit the candidate’s specific experiences.

Unstructured interviews are sometimes referred to as ‘discovery interviews’ and are more like a ‘guided conservation’ than a strictly structured interview. They are sometimes called informal interviews.

Unstructured interviews are most useful in qualitative research to analyze attitudes and values. Though they rarely provide a valid basis for generalization, their main advantage is that they enable the researcher to probe social actors’ subjective points of view.

Interviewer Self-Disclosure

Interviewer self-disclosure involves the interviewer revealing personal information or opinions during the research interview. This may increase rapport but risks changing dynamics away from a focus on facilitating the interviewee’s account.

In unstructured interviews, the informal conversational style may deliberately include elements of interviewer self-disclosure, mirroring ordinary conversation dynamics.

Interviewer self-disclosure risks changing the dynamics away from facilitation of interviewee accounts. It should not be ruled out entirely but requires skillful handling informed by reflection.

- An informal interviewing style with some interviewer self-disclosure may increase rapport and participant openness. However, it also increases the chance of the participant converging opinions with the interviewer.

- Complete interviewer neutrality is unlikely. However, excessive informality and self-disclosure risk the interview becoming more of an ordinary conversation and producing consensus accounts.

- Overly personal disclosures could also be seen as irrelevant and intrusive by participants. They may invite increased intimacy on uncomfortable topics.

- The safest approach seems to be to avoid interviewer self-disclosures in most cases. Where an informal style is used, disclosures require careful judgment and substantial interviewing experience.

- If asked for personal opinions during an interview, the interviewer could highlight the defined roles and defer that discussion until after the interview.

- Unstructured interviews are more flexible as questions can be adapted and changed depending on the respondents’ answers. The interview can deviate from the interview schedule.

- Unstructured interviews generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

- They also have increased validity because it gives the interviewer the opportunity to probe for a deeper understanding, ask for clarification & allow the interviewee to steer the direction of the interview, etc. Interviewers have the chance to clarify any questions of participants during the interview.

- It can be time-consuming to conduct an unstructured interview and analyze the qualitative data (using methods such as thematic analysis).

- Employing and training interviewers is expensive and not as cheap as collecting data via questionnaires . For example, certain skills may be needed by the interviewer. These include the ability to establish rapport and knowing when to probe.

- Interviews inevitably co-construct data through researchers’ agenda-setting and question-framing. Techniques like open questions provide only limited remedies.

Focus Group Interview

Focus group interview is a qualitative approach where a group of respondents are interviewed together, used to gain an in‐depth understanding of social issues.

This type of interview is often referred to as a focus group because the job of the interviewer ( or moderator ) is to bring the group to focus on the issue at hand. Initially, the goal was to reach a consensus among the group, but with the development of techniques for analyzing group qualitative data, there is less emphasis on consensus building.

The method aims to obtain data from a purposely selected group of individuals rather than from a statistically representative sample of a broader population.

The role of the interview moderator is to make sure the group interacts with each other and do not drift off-topic. Ideally, the moderator will be similar to the participants in terms of appearance, have adequate knowledge of the topic being discussed, and exercise mild unobtrusive control over dominant talkers and shy participants.

A researcher must be highly skilled to conduct a focus group interview. For example, the moderator may need certain skills, including the ability to establish rapport and know when to probe.

- Group interviews generate qualitative narrative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondents to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation. Qualitative data also includes observational data, such as body language and facial expressions.

- Group responses are helpful when you want to elicit perspectives on a collective experience, encourage diversity of thought, reduce researcher bias, and gather a wider range of contextualized views.

- They also have increased validity because some participants may feel more comfortable being with others as they are used to talking in groups in real life (i.e., it’s more natural).

- When participants have common experiences, focus groups allow them to build on each other’s comments to provide richer contextual data representing a wider range of views than individual interviews.

- Focus groups are a type of group interview method used in market research and consumer psychology that are cost – effective for gathering the views of consumers .

- The researcher must ensure that they keep all the interviewees” details confidential and respect their privacy. This is difficult when using a group interview. For example, the researcher cannot guarantee that the other people in the group will keep information private.

- Group interviews are less reliable as they use open questions and may deviate from the interview schedule, making them difficult to repeat.

- It is important to note that there are some potential pitfalls of focus groups, such as conformity, social desirability, and oppositional behavior, that can reduce the usefulness of the data collected.

For example, group interviews may sometimes lack validity as participants may lie to impress the other group members. They may conform to peer pressure and give false answers.

To avoid these pitfalls, the interviewer needs to have a good understanding of how people function in groups as well as how to lead the group in a productive discussion.

Semi-Structured Interview

Semi-structured interviews lie between structured and unstructured interviews. The interviewer prepares a set of same questions to be answered by all interviewees. Additional questions might be asked during the interview to clarify or expand certain issues.

In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer has more freedom to digress and probe beyond the answers. The interview guide contains a list of questions and topics that need to be covered during the conversation, usually in a particular order.

Semi-structured interviews are most useful to address the ‘what’, ‘how’, and ‘why’ research questions. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses can be performed on data collected during semi-structured interviews.

- Semi-structured interviews allow respondents to answer more on their terms in an informal setting yet provide uniform information making them ideal for qualitative analysis.

- The flexible nature of semi-structured interviews allows ideas to be introduced and explored during the interview based on the respondents’ answers.

- Semi-structured interviews can provide reliable and comparable qualitative data. Allows the interviewer to probe answers, where the interviewee is asked to clarify or expand on the answers provided.

- The data generated remain fundamentally shaped by the interview context itself. Analysis rarely acknowledges this endemic co-construction.

- They are more time-consuming (to conduct, transcribe, and analyze) than structured interviews.

- The quality of findings is more dependent on the individual skills of the interviewer than in structured interviews. Skill is required to probe effectively while avoiding biasing responses.

The Interviewer Effect

Face-to-face interviews raise methodological problems. These stem from the fact that interviewers are themselves role players, and their perceived status may influence the replies of the respondents.

Because an interview is a social interaction, the interviewer’s appearance or behavior may influence the respondent’s answers. This is a problem as it can bias the results of the study and make them invalid.

For example, the gender, ethnicity, body language, age, and social status of the interview can all create an interviewer effect. If there is a perceived status disparity between the interviewer and the interviewee, the results of interviews have to be interpreted with care. This is pertinent for sensitive topics such as health.

For example, if a researcher was investigating sexism amongst males, would a female interview be preferable to a male? It is possible that if a female interviewer was used, male participants might lie (i.e., pretend they are not sexist) to impress the interviewer, thus creating an interviewer effect.

Flooding interviews with researcher’s agenda

The interactional nature of interviews means the researcher fundamentally shapes the discourse, rather than just neutrally collecting it. This shapes what is talked about and how participants can respond.

- The interviewer’s assumptions, interests, and categories don’t just shape the specific interview questions asked. They also shape the framing, task instructions, recruitment, and ongoing responses/prompts.

- This flooding of the interview interaction with the researcher’s agenda makes it very difficult to separate out what comes from the participant vs. what is aligned with the interviewer’s concerns.

- So the participant’s talk ends up being fundamentally shaped by the interviewer rather than being a more natural reflection of the participant’s own orientations or practices.

- This effect is hard to avoid because interviews inherently involve the researcher setting an agenda. But it does mean the talk extracted may say more about the interview process than the reality it is supposed to reflect.

Interview Design

First, you must choose whether to use a structured or non-structured interview.

Characteristics of Interviewers

Next, you must consider who will be the interviewer, and this will depend on what type of person is being interviewed. There are several variables to consider:

- Gender and age : This can greatly affect respondents’ answers, particularly on personal issues.

- Personal characteristics : Some people are easier to get on with than others. Also, the interviewer’s accent and appearance (e.g., clothing) can affect the rapport between the interviewer and interviewee.

- Language : The interviewer’s language should be appropriate to the vocabulary of the group of people being studied. For example, the researcher must change the questions’ language to match the respondents’ social background” age / educational level / social class/ethnicity, etc.

- Ethnicity : People may have difficulty interviewing people from different ethnic groups.

- Interviewer expertise should match research sensitivity – inexperienced students should avoid interviewing highly vulnerable groups.

Interview Location

The location of a research interview can influence the way in which the interviewer and interviewee relate and may exaggerate a power dynamic in one direction or another. It is usual to offer interviewees a choice of location as part of facilitating their comfort and encouraging participation.

However, the safety of the interviewer is an overriding consideration and, as mentioned, a minimal requirement should be that a responsible person knows where the interviewer has gone and when they are due back.

Remote Interviews

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated remote interviewing for research continuity. However online interview platforms provide increased flexibility even under normal conditions.

They enable access to participant groups across geographical distances without travel costs or arrangements. Online interviews can be efficiently scheduled to align with researcher and interviewee availability.

There are practical considerations in setting up remote interviews. Interviewees require access to internet and an online platform such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams or Skype through which to connect.

Certain modifications help build initial rapport in the remote format. Allowing time at the start of the interview for casual conversation while testing audio/video quality helps participants settle in. Minor delays can disrupt turn-taking flow, so alerting participants to speak slightly slower than usual minimizes accidental interruptions.

Keeping remote interviews under an hour avoids fatigue for stare at a screen. Seeking advanced ethical clearance for verbal consent at the interview start saves participant time. Adapting to the remote context shows care for interviewees and aids rich discussion.

However, it remains important to critically reflect on how removing in-person dynamics may shape the co-created data. Perhaps some nuances of trust and disclosure differ over video.

Vulnerable Groups

The interviewer must ensure that they take special care when interviewing vulnerable groups, such as children. For example, children have a limited attention span, so lengthy interviews should be avoided.

Developing an Interview Schedule

An interview schedule is a list of pre-planned, structured questions that have been prepared, to serve as a guide for interviewers, researchers and investigators in collecting information or data about a specific topic or issue.

- List the key themes or topics that must be covered to address your research questions. This will form the basic content.

- Organize the content logically, such as chronologically following the interviewee’s experiences. Place more sensitive topics later in the interview.

- Develop the list of content into actual questions and prompts. Carefully word each question – keep them open-ended, non-leading, and focused on examples.

- Add prompts to remind you to cover areas of interest.

- Pilot test the interview schedule to check it generates useful data and revise as needed.

- Be prepared to refine the schedule throughout data collection as you learn which questions work better.

- Practice skills like asking follow-up questions to get depth and detail. Stay flexible to depart from the schedule when needed.

- Keep questions brief and clear. Avoid multi-part questions that risk confusing interviewees.

- Listen actively during interviews to determine which pre-planned questions can be skipped based on information the participant has already provided.

The key is balancing preparation with the flexibility to adapt questions based on each interview interaction. With practice, you’ll gain skills to conduct productive interviews that obtain rich qualitative data.

The Power of Silence

Strategic use of silence is a key technique to generate interviewee-led data, but it requires judgment about appropriate timing and duration to maintain mutual understanding.

- Unlike ordinary conversation, the interviewer aims to facilitate the interviewee’s contribution without interrupting. This often means resisting the urge to speak at the end of the interviewee’s turn construction units (TCUs).

- Leaving a silence after a TCU encourages the interviewee to provide more material without being led by the interviewer. However, this simple technique requires confidence, as silence can feel socially awkward.

- Allowing longer silences (e.g. 24 seconds) later in interviews can work well, but early on even short silences may disrupt rapport if they cause misalignment between speakers.

- Silence also allows interviewees time to think before answering. Rushing to re-ask or amend questions can limit responses.

- Blunt backchannels like “mm hm” also avoid interrupting flow. Interruptions, especially to finish an interviewee’s turn, are problematic as they make the ownership of perspectives unclear.

- If interviewers incorrectly complete turns, an upside is it can produce extended interviewee narratives correcting the record. However, silence would have been better to let interviewees shape their own accounts.

Recording & Transcription

Design choices.

Design choices around recording and engaging closely with transcripts influence analytic insights, as well as practical feasibility. Weighing up relevant tradeoffs is key.

- Audio recording is standard, but video better captures contextual details, which is useful for some topics/analysis approaches. Participants may find video invasive for sensitive research.

- Digital formats enable the sharing of anonymized clips. Additional microphones reduce audio issues.

- Doing all transcription is time-consuming. Outsourcing can save researcher effort but needs confidentiality assurances. Always carefully check outsourced transcripts.

- Online platform auto-captioning can facilitate rapid analysis, but accuracy limitations mean full transcripts remain ideal. Software cleans up caption file formatting.

- Verbatim transcripts best capture nuanced meaning, but the level of detail needed depends on the analysis approach. Referring back to recordings is still advisable during analysis.

- Transcripts versus recordings highlight different interaction elements. Transcripts make overt disagreements clearer through the wording itself. Recordings better convey tone affiliativeness.

Transcribing Interviews & Focus Groups

Here are the steps for transcribing interviews:

- Play back audio/video files to develop an overall understanding of the interview

- Format the transcription document:

- Add line numbers

- Separate interviewer questions and interviewee responses

- Use formatting like bold, italics, etc. to highlight key passages

- Provide sentence-level clarity in the interviewee’s responses while preserving their authentic voice and word choices

- Break longer passages into smaller paragraphs to help with coding

- If translating the interview to another language, use qualified translators and back-translate where possible

- Select a notation system to indicate pauses, emphasis, laughter, interruptions, etc., and adapt it as needed for your data

- Insert screenshots, photos, or documents discussed in the interview at the relevant point in the transcript

- Read through multiple times, revising formatting and notations

- Double-check the accuracy of transcription against audio/videos

- De-identify transcript by removing identifying participant details

The goal is to produce a formatted written record of the verbal interview exchange that captures the meaning and highlights important passages ready for the coding process. Careful transcription is the vital first step in analysis.

Coding Transcripts

The goal of transcription and coding is to systematically transform interview responses into a set of codes and themes that capture key concepts, experiences and beliefs expressed by participants. Taking care with transcription and coding procedures enhances the validity of qualitative analysis .

- Read through the transcript multiple times to become immersed in the details

- Identify manifest/obvious codes and latent/underlying meaning codes

- Highlight insightful participant quotes that capture key concepts (in vivo codes)

- Create a codebook to organize and define codes with examples

- Use an iterative cycle of inductive (data-driven) coding and deductive (theory-driven) coding

- Refine codebook with clear definitions and examples as you code more transcripts

- Collaborate with other coders to establish the reliability of codes

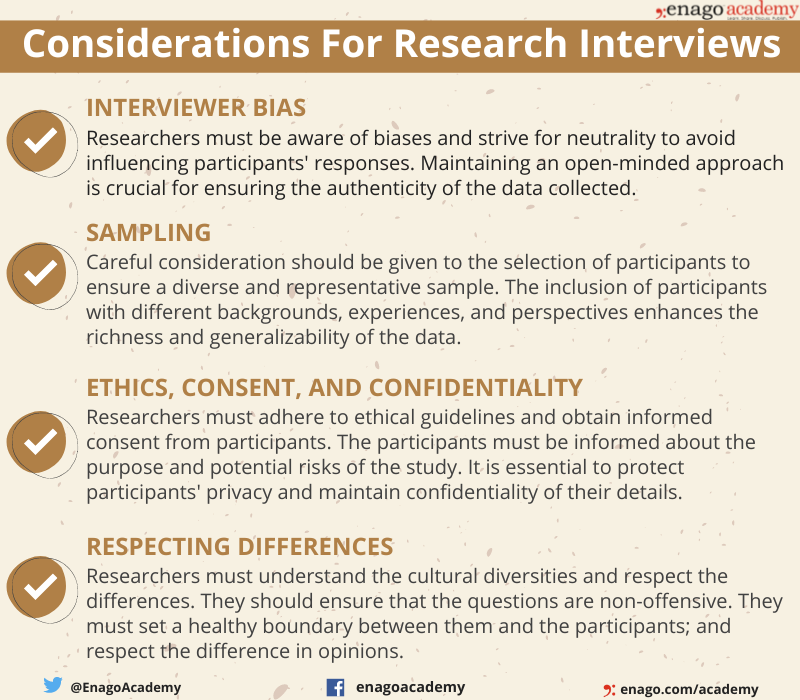

Ethical Issues

Informed consent.

The participant information sheet must give potential interviewees a good idea of what is involved if taking part in the research.

This will include the general topics covered in the interview, where the interview might take place, how long it is expected to last, how it will be recorded, the ways in which participants’ anonymity will be managed, and incentives offered.

It might be considered good practice to consider true informed consent in interview research to require two distinguishable stages:

- Consent to undertake and record the interview and

- Consent to use the material in research after the interview has been conducted and the content known, or even after the interviewee has seen a copy of the transcript and has had a chance to remove sections, if desired.

Power and Vulnerability

- Early feminist views that sensitivity could equalize power differences are likely naive. The interviewer and interviewee inhabit different knowledge spheres and social categories, indicating structural disparities.

- Power fluctuates within interviews. Researchers rely on participation, yet interviewees control openness and can undermine data collection. Assumptions should be avoided.

- Interviews on sensitive topics may feel like quasi-counseling. Interviewers must refrain from dual roles, instead supplying support service details to all participants.

- Interviewees recruited for trauma experiences may reveal more than anticipated. While generating analytic insights, this risks leaving them feeling exposed.

- Ultimately, power balances resist reconciliation. But reflexively analyzing operations of power serves to qualify rather than nullify situtated qualitative accounts.

Some groups, like those with mental health issues, extreme views, or criminal backgrounds, risk being discredited – treated skeptically by researchers.

This creates tensions with qualitative approaches, often having an empathetic ethos seeking to center subjective perspectives. Analysis should balance openness to offered accounts with critically examining stakes and motivations behind them.

Potter, J., & Hepburn, A. (2005). Qualitative interviews in psychology: Problems and possibilities. Qualitative research in Psychology , 2 (4), 281-307.

Houtkoop-Steenstra, H. (2000). Interaction and the standardized survey interview: The living questionnaire . Cambridge University Press

Madill, A. (2011). Interaction in the semi-structured interview: A comparative analysis of the use of and response to indirect complaints. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 8 (4), 333–353.

Maryudi, A., & Fisher, M. (2020). The power in the interview: A practical guide for identifying the critical role of actor interests in environment research. Forest and Society, 4 (1), 142–150

O’Key, V., Hugh-Jones, S., & Madill, A. (2009). Recruiting and engaging with people in deprived locales: Interviewing families about their eating patterns. Social Psychological Review, 11 (20), 30–35.

Puchta, C., & Potter, J. (2004). Focus group practice . Sage.

Schaeffer, N. C. (1991). Conversation with a purpose— Or conversation? Interaction in the standardized interview. In P. P. Biemer, R. M. Groves, L. E. Lyberg, & N. A. Mathiowetz (Eds.), Measurement errors in surveys (pp. 367–391). Wiley.

Silverman, D. (1973). Interview talk: Bringing off a research instrument. Sociology, 7 (1), 31–48.

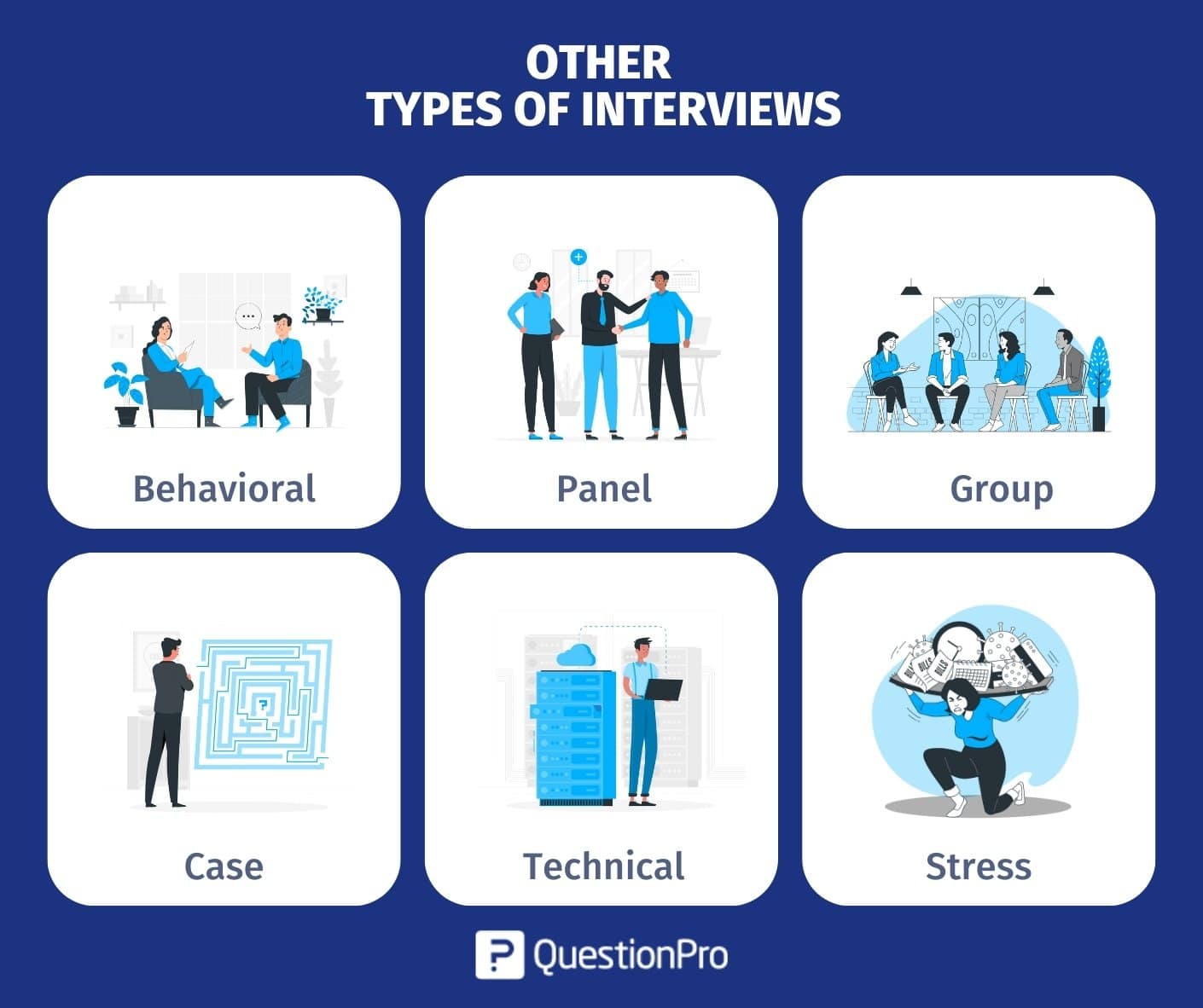

Understanding the Various Types of Interviews in Research

Table of Contents

Have you ever considered the intricacies of a conversation? When it comes to research, particularly in psychology , interviews are not just simple conversations—they are carefully crafted tools designed to extract information, understanding, and insights. But not all interviews are created equal. Each type serves a unique purpose in the quest for knowledge. Let’s delve into the various types of interviews used in research and understand how each paves the way for discoveries within the human psyche.

Informal Conversational Interviews

Imagine a chat over coffee with a friend where the conversation flows naturally, without a rigid structure. This is the essence of an informal conversational interview. Here, the interviewer has no set questions but allows the dialogue to be guided by the interviewee’s responses and the natural course of the conversation. This flexibility can unveil rich, detailed insights, making it ideal for exploratory research.

- Spontaneous Interaction : Questions are developed spontaneously and are highly adaptable to the interviewee’s thoughts and feelings.

- Contextual Richness : The setting and flow can yield deep understanding, as interviewees often feel more comfortable and open.

- Challenges: This type of interview requires skilled interviewers who can guide the conversation effectively without leading it astray.

General Interview Guides

Shifting towards a bit more structure, general interview guides come into play. While still maintaining a conversational quality, this approach involves a prepared set of questions or topics to ensure that certain areas are explored. It strikes a balance between the natural flow of an informal interview and the focused inquiry of a more structured approach.

- Guided Flexibility : The interviewer follows a guide but has the freedom to probe deeper or ask follow-up questions.

- Consistency : Ensures that all areas of interest are covered with each participant, aiding in comparative analysis.

- Preparation: Requires careful planning to construct a guide that’s comprehensive yet flexible.

Standardized Open\-Ended Interviews

When researchers seek to combine the depth of open-ended questions with the comparability of structured interviews, standardized open-ended interviews come into the picture. This format involves a set of open-ended questions asked in the same way and order to every interviewee, allowing for rich, nuanced answers that can still be compared across different participants.

- Consistent Inquiry : The same questions ensure that each interviewee has the same opportunity to provide information.

- Open\-Ended Responses : Participants can express their thoughts freely, offering deeper insight than closed-ended questions.

- Data Analysis : While offering depth, the standardized nature of these interviews facilitates easier analysis and comparison.

Closed Fixed\-Response Interviews

For research that requires quantifiable data, closed fixed-response interviews are the go-to format. These interviews consist of a set of predetermined questions with a limited set of possible answers, much like a multiple-choice test. The rigidity of this structure makes it less suitable for exploratory research but excellent for statistical analysis.

- Quantifiable Data : Responses are easy to categorize and quantify, making them ideal for statistical analysis.

- Comparability : The uniformity of responses allows for straightforward comparison across a large number of interviewees.

- Limited Depth: The predefined responses can restrict the depth of understanding and may not capture the nuances of participants’ experiences.

Telephone Interviews

In today’s digital age , telephone interviews have become increasingly prevalent. They offer a practical and cost-effective alternative to face-to-face interviews, especially when geographical barriers exist. Telephone interviews can follow any of the aforementioned structures but require a particular set of skills given the absence of visual cues and potential for distractions.

- Accessibility : Overcomes geographical limitations and can be more convenient for participants.

- Audio\-Only Dynamics : The interviewer must rely solely on verbal cues, which can be both a limitation and an advantage for skilled interviewers.

- Considerations: The lack of visual interaction can affect rapport and the interviewer’s ability to observe non-verbal cues.

Choosing the Right Interview Type