- Senior Fellows

- Research Fellows

- Submission Guidelines

- Media Inquiries

- Commentary & Analysis

Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- October 2021 War Studies Conference

- November 2020 War Studies Conference

- November 2018 War Studies Conference

- March 2018 War Studies Conference

- November 2016 War Studies Conference

- Class of 1974 MWI Podcast

- Urban Warfare Project Podcast

- Social Science of War

- Urban Warfare Project

- Project 6633

- Shield Notes

- Rethinking Civ-Mil

- Book Reviews

Select Page

The American Way of War in the Twenty-First Century: Three Inherent Challenges

Shmuel Shmuel | 06.30.20

The reality of American military power has long been that the United States must project its forces into the enemy’s territory. This brings with it a host of challenges, some inflicted by the adversary and others that are self-inflicted (such as lack of strategic lift or production capacity ). In any future war, the US military will likely play an “away game,” and an adversary will probably not allow the United States to leisurely amass personnel and equipment on its borders, but will actively try to prevent it. As a result, the US military will suffer from an inherent asymmetry and have immense costs imposed on it, at least in the initial phases of the war. This challenge lies at the heart of what is colloquially called the “anti-access/area denial” family of military concepts.

To solve the challenges associated with this inherent asymmetry, a range of ideas have emerged— Multi-Domain Operations from the US Army, distributed lethality from the US Navy, Joint All-Domain Command and Control from the US Air Force, “mosaic warfare” from DARPA, and various “sweeping changes” from the Marine Corps .

A review of the commonalities between these concepts, however, reveals inherent challenges in them—and as such, at the heart of American military thought.

So Say We All

The first item in common between virtually all American concepts is the perception of the threat and threat actors. Even if there are some disagreements on the margins about the details, the threat is perceived as a global or regional military power, employing a long-range, layered, defensive complex, that protects long-range “strategic” offensive capabilities. The specific offensive and defensive assets may vary according to the unique environment the adversary will operate in. But despite the different details of assessments of, for example, Russia and China, the basic idea of both powers is similar. They both aim to protect land-based strike assets that will be used to strike American military capabilities, seeking to complicate the American arrival to the area of interest and operations inside it once US forces have arrived.

Second, there is also a general agreement about ways to survive this threat. Because the US military assesses the adversarial anti-access/area denial system as essentially a long-range strike complex, the ability to find targets and relay their locations back to strike assets in real time (called a “kill chain”) is essential to the adversary. Disrupting that chain can drive a stake through the heart of the entire strike complex.

The third area of consensus is the solution to the challenge. The adversary presents a system that is assumed to be both lethal and resilient. The overlapping fields of fire, reaching hundreds of kilometers from the adversary’s territory, are presented sometimes as impenetrable bubbles . The solution is to avoid detection, penetrate those bubbles, and eliminate the adversary’s strike assets themselves and their supporting command, control, and intelligence infrastructure. In a way, the American answer to the adversary’s intelligence-strike complex is the creation of a competing intelligence-strike complex, which will be able to direct distributed forces and strike assets, to operate inside the adversary’s anti-access/area denial bubbles and dismantle them from the inside. Herein lie three main challenges.

Inside Out or Outside In

In many, if not all, future conflict scenarios the US military expects to start the war numerically inferior , and quite likely surprised . The United States can try to compensate for this disadvantage with technological superiority, although that advantage is eroding . And in any case, quantity has a quality all its own. It is thus fairly safe to assume that a significant portion of American forces will have to fight their way into the area of operations, while the residual forward-positioned forces, possibly cut off from reachback support, will fight a defensive battle, or even a retrograde, against numerically superior forces.

The forces coming in will have to punch their way through the adversary’s defensive complex, possibly partially blind to what is going on inside those perimeters. Since the range of current defensive capabilities is longer than that of many American strike assets, the US military will have to use standoff munitions and small numbers of penetrating platforms. This approach is fighting “from the outside in.”

However, in the various concepts mentioned above, it is generally agreed that the best way to disintegrate the adversary’s defensive bubbles is by maneuvering inside them, obtaining real-time intelligence about defensive and offensive assets, and attacking them rapidly. This is fighting “from the inside out,” mostly with short-range weapons by what the Marine Corps calls “stand-in forces.” Since the United States will probably not have sufficient forces to perform large-scale operations with these forces in the initial phase of the war, there is a constant tension between the goal of achieving a sufficient stand-in presence to have an impact and the rather safe assumption that the war might start while the US is mostly in a standoff position. This is a gap that neither the Army’s concept nor the Marine Corps’ planning guidance elaborates on how to bridge. Both, as well as the National Defense Strategy, mention forward-positioned forces, but it is understood that those will never be enough. The answer that is presented is heavily investing in standoff fires capabilities and penetrating platform , so as to create a lethal intelligence-strike complex, or what amounts to a reverse anti-access/area denial system .

The Away Team’s Challenge

The assumption is that these reverse anti-access/area denial capabilities might be able to bring enough high explosives to enough targets to either punch a hole in opposing defenses or cause the adversary, somehow, to surrender. This assumption, however, ignores the key asymmetry between American forces and their adversaries. The Americans, as mentioned above, have to play an away game. That means they have to bring their forces and their supplies from the United States, or other remote locations, to wherever they are fighting. Despite attempts to somehow avoid the “iron mountain” of supplies, there is no way of hoping away physics. Vehicles require fuel, people require food, and munitions require replenishment. Eventually, prepositioned supplies and forces will run out, and the American war effort will require aerial and naval assets both for fighting as well as for transportation—assets that are, by definition, lucrative targets.

The adversary, on the other hand, is fighting on or from land—and critically, on or close to the adversary’s own territory. That enables the use of land platforms both for transport and for fighting. Land platforms are smaller, cheaper, simpler to produce, and far more numerous than their air and naval equivalents. Also, the land domain, with its mountains, valleys, and trees, is easier to hide in than the empty air and open seas. Furthermore, the land domain allows a defender dig in, and thus protect essential supplies, platforms, and nodes of command and control. Thus, China can fire tens of multi-million-dollar missiles at a nuclear aircraft carrier. Once this carrier is hit, it might take years to replace and will subtract substantial portion of American strike capabilities for a duration of time, especially at the outset of the war. On the other hand, mainland China has hundreds of thousands of targets. Very few of them are as strategic as an aircraft carrier. Those that China deems strategically vital are probably well dug in and thus physically hard to destroy and many of the rest are cheaper and more replaceable than even the munitions fired at them.

Even assuming away the friction of war, the United States might not have enough munitions to strike so many targets—and smart munitions, even the simple ones, require more resources to develop and produce. That means the US military can’t win a salvo war. However, its adversaries can.

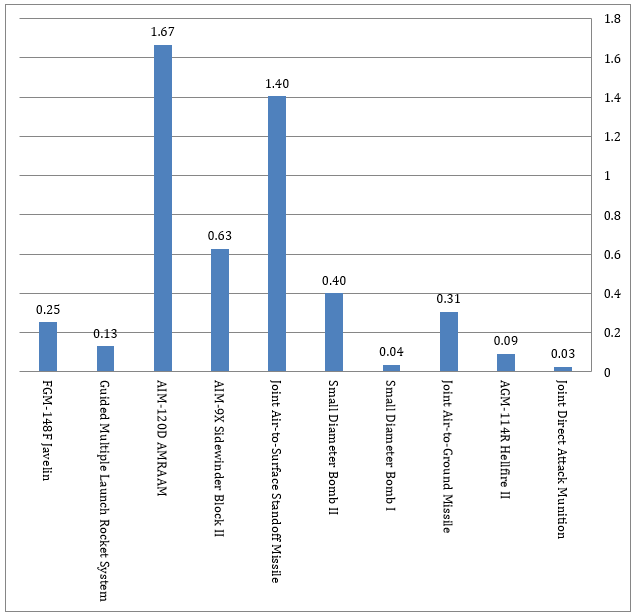

Average costs of ammunition per item, FY 2017–2019 (in millions of US$)

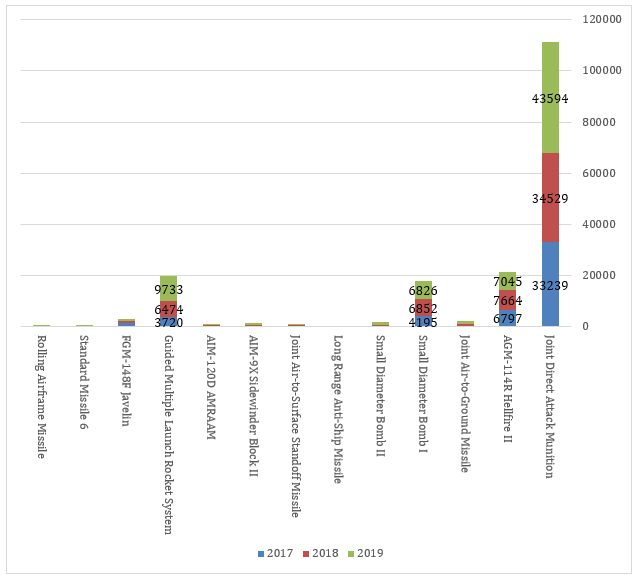

Numbers of munitions purchased, FY 2017–2019 (see next figure for further detail)

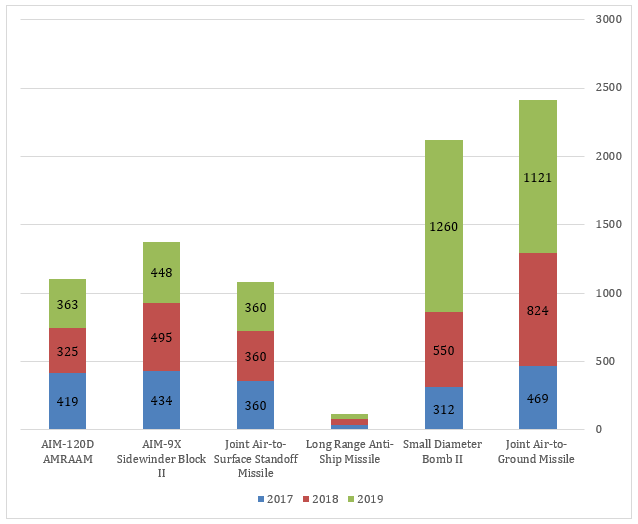

Numbers of munitions purchased, FY 2017–2019

War is More than Striking Targets

This leads to another, larger, asymmetry between the United States and its adversaries. A look at current wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, as well as past wars such as Vietnam and World War II demonstrates how incredibly resilient a nation-state can be. History gives the lie to “effects-based operations” concepts that assume an enemy can be brought to its knees with a few targeted strikes on key nodes in its system. A nation-state with many millions of people can withstand years of war and hundreds of thousands of casualties and keep fighting.

However, the so-called revolution in military affairs that captured many defense thinkers’ minds in the late twentieth century did change something significant in military forces—or at least in Western military forces. It made them harder to replace. If in the past a national economy could be mobilized to produce hundreds of thousands of planes, tanks, and ships, today mobilization is far harder , and weapons are far costlier and take longer to produce.

A Western military could, theoretically, be broken by attrition—at least long enough for its adversary to establish facts on the ground. This is the other side’s concept of victory. The goal is to deny an adversary’s will or ability to fight on at least one (or more) levels of war. A concept of victory is unique to the opponent and is a function of its unique nature, environment, and circumstances. There are two important items to note about a concept of victory: one, it can be hard to imitate that of an adversary; and two, a concept of victory that is relevant against a certain foe might not be transferable to a different adversary.

A New Way of War, Inspired by the Past

The United States is not the first power to face this challenge. Before the age of American hegemony, it was Great Britain who ruled interests the sun never set on. The British faced the reality of not having a foothold on the continent where it considered its core interests to lie since the fall of the Pale of Calais. Britain had to compete globally with France, as well as on the European level with regional, smaller powers such as Austria, Russia, Spain and later, Prussia. At the height of its success, the Great Britain had a very distinct way of managing its interests. To execute its wars, Britain had replaceable European partners who conducted most of the warfighting on land. Meanwhile, Britain itself funded these wars, supported European partners with strategic lift, and secured the seas—while advancing British interests throughout the world under the cover of the war in Europe. While supporting its European partners, Britain simultaneously conducted its own global fight against its main rival, France.

The key to Britain’s power was not domination of the entire spectrum of conflict in all domains, but rather its economic might, backed by superiority in a single (naval) domain and its diplomatic ability to always find competent partners—at least militarily. Also, Britain chose to conduct limited wars. The goal, after the Hundred Years’ War, wasn’t taking over the thrones or changing the regimes or religions of any other European power, but rather to balance power in Europe and take control of colonies and other economic interests outside of Europe. Thus, war could always end with negotiations, without dire defeats and complete victories.

In a way, this represents a model. The United States doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel. It just needs to rediscover it.

The ways to overcome the gaps in American military thinking mentioned above are twofold—tactical and strategic.

On the tactical level, the only way for the United States to overcome the standoff/stand-in gap is to use forces that are already inside the area of operations. These forces can never be entirely, or even mostly, American. They should overwhelmingly belong to host nations that border the powers the US military might fight against. The United States is fortunate to have a network of rich nations as allies. These nations could sustain vast militaries, at an affordable price, especially if their forces are organized for defense and operations close to their borders.

For that matter, the United States has little use of mid-sized nations that pay a premium for expeditionary , high-tech capabilities. It should encourage its allies to build forces that can withstand war in their area instead . Meanwhile, the United States should play a mostly supporting role, in the global theater—at least in the beginning of the war. It should help fund and regenerate forces , secure the global commons that support its allies’ wartime economies, and employ strategic enablers such as airpower, strategic intelligence collection, and, of course, the ultimate guarantee of the nuclear umbrella. When the United States fights outside its adversaries’ backyards, those adversaries will be forced to use expeditionary capabilities and pay the same premium Americans pay for their capabilities, but with far smaller budgets to sustain it. Thus, the concept of victory for the United States should be for partners to achieve tactical victory while the US military pursues operational victory—ultimately achieving strategic victory.

But this tactical solution will be for naught if the United States does not match it with another reform on the strategic level—abandoning the concept of total wars. The short era of fighting a great power, or even a medium power, to submission has passed. There is little chance that any combination of European countries can conquer Moscow or totally defeat China—at least without nuclear weapons. The time between the Napoleonic Wars and World War II was unique, in that societies were small and rural enough to subdue, yet large, young, rich, and productive enough to support large-scale mobilization, absorb casualties, and pursue conquests. Even assuming some kind of land maneuver in Russia or China is possible, there is the added factor of global urbanization. A modern megacity is a military nut no one knows how to crack. If the battle for Mosul is any indication, there is no military large enough to take over a single mid-sized city in China, let alone the entire state. Bombing it to submission, will probably not do either.

So what is left is to fight on the periphery —on islands, waterways, and bases far from the mainland or motherland, and often for interests far from them, as well. Incidentally, these are also interests that can later be negotiated over, as opposed to the survival of the nation or the regime.

These two suggestions are a continuation, in a way, of British military thought at the height of the island nation’s global power—fighting limited wars with partners. It seems that the world is slowly reverting to its pre-modern form—a big and fragile Russia, a strong China, and wealth that is flowing on the world’s commons, with no power willing or able to annihilate the other. In this world, concepts developed for an era of unipolar supremacy will not do.

Shmuel Shmuel is the director of the Institute for Military Studies at the Israel Defense Forces’ Dado Center for Interdisciplinary Military Studies . Follow him on Twitter @Samdavaham .

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or those of the IDF or the Dado Center.

Image credit: Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Kaila V. Peters, US Navy

Maybe the most provocative and insightful sentence I've read on this subject in a long time:

"The time between the Napoleonic Wars and World War II was unique, in that societies were small and rural enough to subdue, yet large, young, rich, and productive enough to support large-scale mobilization, absorb casualties, and pursue conquests."

If true — and I certainly think it might be — this should cause the Army to rethink its approach to large-scale combat within the context of great power war.

Great article my friend! Will you be willing to give lecture about that?

A very good article. We are living in a digital information age, thus we need to reinvent the way we fight future wars by redefining their nature.

This may seem nuanced, but its an important point. "As a result, the US military will suffer from an inherent asymmetry and have immense costs imposed on it, at least in the initial phases of the war."

– Wars do not lend themselves to flawed notions of structuring such as "phases" – even against an inferior enemy; for individual operations within the overall campaigning effort – phases may be appropriate.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The articles and other content which appear on the Modern War Institute website are unofficial expressions of opinion. The views expressed are those of the authors, and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

The Modern War Institute does not screen articles to fit a particular editorial agenda, nor endorse or advocate material that is published. Rather, the Modern War Institute provides a forum for professionals to share opinions and cultivate ideas. Comments will be moderated before posting to ensure logical, professional, and courteous application to article content.

Most Popular Posts

- Defending the City: An Overview of Defensive Tactics from the Modern History of Urban Warfare

- The Five Reasons Wars Happen

- Understanding the Counterdrone Fight: Insights from Combat in Iraq and Syria

Announcements

- Join Us Friday, April 26 for a Livestream of the 2024 Hagel Lecture, Featuring Secretary Chuck Hagel and Secretary Jeh Johnson

- Announcing the Modern War Institute’s 2023–24 Senior and Research Fellows

- Essay Contest Call for Submissions: Solving the Military Recruiting Crisis

- Call for Applications: MWI’s 2023–24 Research Fellows Program

- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Scott Atlas

- Thomas Sargent

- Stephen Kotkin

- Michael McConnell

- Morris P. Fiorina

- John F. Cogan

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- National Security, Technology & Law

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Pacific Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press.

The American Way of War

William Shawcross, the British journalist, historian, and human rights advocate—once a fierce critic of the Nixon-Kissinger years, now a defender of the West’s struggle against radical Islam—has written the best book yet on the dilemmas Western governments face in dealing with Islamic terrorists. 1

Shawcross focuses on three general topics: the Bush-Cheney anti-terrorism protocols that emerged after 9/11 and their relationship with past Western efforts at punishing war criminals at Nuremberg; the poorly thought out and ultimately cancelled decision to try Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in a federal civilian court in Manhattan; and the strange somersault of President Obama, who has now embraced or expanded almost every measure that Senator and candidate Obama alleged was either anti-constitutional, counter-productive, or near barbarous.

Shawcross reminds us that Nuremberg, while not perfect jurisprudence, was good enough to punish Nazi war criminals in a legal, sober, and judicious fashion—without resorting to summary executions or referring high officers of the Third Reich to civilian courts in Britain and the United States. His father, Attorney General Hartley Shawcross, was the leading British prosecutor at Nuremberg and later led the prosecutions of various Soviet spies—an experience that the younger Shawcross alludes to frequently to good effect in his book. We have, then, both ample precedent and confidence that military tribunals can be used to try war criminals and terrorists.

And what is the alternative? Shawcross walks us through the proposed trial of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed—championed by a Democratic administration, with Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, which, at the time, enjoyed broad public support. Yet the immediate objections to the KSM trial from across the political spectrum—does the architect of 9/11 deserve Miranda rights and a state-supported legal team?—forced liberal Attorney General Eric Holder to back down, given the many contradictions in trying a terrorist as if he were an American felon.

In understated fashion, Shawcross finishes by systematically reviewing the strange about-face of President Obama on the anti-terrorism policies that he inherited. Candidate Obama, to much acclaim and with great effect in damaging public support for the Bush-Cheney protocols, proclaimed Guantanamo, renditions, tribunals, preventative detention, wiretaps, and intercepts to be amoral and superfluous—only to embrace them all as president. Shawcross is not surprised: any executive responsible for the security of his citizens—as opposed to a rhetorician making campaign talking points—would appreciate that these protocols were useful and legal. In the present confusing times, we have reached an Orwellian point when waterboarding three confessed mass-murdering terrorists was between 2003-2008 deemed a war crime, while blowing apart over 2,000 suspected terrorists by drone assassination since 2009 is apparently not.

We have ample precedent that military tribunals can be used to try war criminals and terrorists.

Shawcross writes carefully, without bluster and exaggeration, and the effect is a damning indictment of much of the popular rhetoric of the decade after 9/11 that insisted we had no legal or moral right to deal with al Qaeda kingpins as we had in the past with other such terrorists and criminals.

Eliot Cohen—author of a valuable study of supreme command and an advisor in Condoleezza Rice’s state department in the latter months of the Bush administration—raises the question: where did the American way of war derive from? 2

Cohen, however, believes the U.S. way of fighting is more complex, incorporating all sorts of non-conventional elements. To make that point, he reviews warfare of the eighteenth-century along the northeastern seaboard of the American continent—that rugged two-hundred-mile corridor of mountains, forests, and lakes from Albany to Montreal dubbed the “Great Warpath.” His investigations reveal two less appreciated sources for the way Americans currently fight.

One was the birth of a unique, and less remarked upon strain of raiding, ambushing, subversion, living off the land, ad hoc alliance building with indigenous peoples, long-range reconnaissance, and patrolling behind enemy lines. The other was a sort of military populism: non-traditional tactics, by which early colonialists survived against the superior numbers of the French, Indians, Canadians—and later their erstwhile British allies—were not strictly mandated from on high by officers steeped in formal strategy and tactics. Most of the ways of defeating savage enemies arose from the ground up among observant Vermont militiamen, New England farmers-turned-fighters, and local community defense forces. They formed the “middle” stratum of the military that not only was in the best position to adapt to new challenges, but was also able to convince both subordinates and superiors how to follow its new military paradigm. In short, it soon became very American for men in the field to draw new tactics up on the fly to fit an ever-changing war—and not to worry much about who had figured out what worked best.

How did so many Americans, with so few resources, fight so well against the better supplied French and British troops?

Whether one accepts his larger thesis, Cohen has offered a fine narrative of the little known French and Indian War, when pre-revolutionary Americans learned to fight in ways that would bring real dividends in the looming Revolutionary War, and then again during the Civil War, whether in the career of Nathan Bedford Forrest or William Tecumseh Sherman.

War, of course, is predicated on weapons. None have killed more human beings—not poison gas, not the atomic bomb, not incendiary napalm, not land mines—than the Soviet-designed AK-47 assault rifle ( Avtomat Kalashnikova—1947 ) . Three recent books review how this lethal weapon emerged; why it became a signature weapon of third-world revolutionaries; and how the so-called Soviet bloc was able to produce an assault rifle often more reliable and easier to use than any contemporary European or American competitor. 3

The most informative account is C. J. Chivers’s scholarly The Gun . Chivers is skeptical of many of the claims by Mikhail Kalashnikov surrounding the birth of AK-47, and offers a fair account of the acrimonious rivalry between the M16 and AK-47. The rivalry reflects the Soviet preferences for reliability, durability, simplicity, and economy versus the American insistence on accuracy and craftsmanship.

Chivers argues that few inventions of the twentieth-century have done so much to kill so many through “war, terror, atrocity, and crime.” AK-47s, he notes, are often the favored weapons of drug cartels, teenaged killers in Africa, terrorists, and insurgents. After offering a clear-headed analysis of the AK-47—focusing on its simple design, easy fabrication, and near indestructability—he surprisingly offers the emotional hope that eventually the seasons, aging, and wear and tear will finally rid the world of this nearly indestructible menace—and with it, the bestowing into the hands of untrained near-children the world over the power to kill indiscriminately and en masse. To this hope, one might rejoin that the fault is not in our stars, but in our selves.

Larry Kahaner’s book AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War is an engaging story of the contemporary AK-47 as a cultural phenomenon. He too reminds us that many of the terrorist movements and insurgencies in Asia, Latin America, and especially Africa would have been impossible without the widespread dispersion of the AK-47, the ideal weapon for impoverished, poorly trained mercenaries. In the revolutionary mind, communism had produced a people’s gun that was every bit the match for capitalism’s more elite weapon, in the real conditions of contemporary war.

Kahaner points out that the acrimonious controversy between the AK-47 and the M16 resurfaced again forty years after the Vietnam War during the post-Saddam Hussein insurgency, when improved versions of both assault rifles collided in the streets of urban Iraq. And the verdict was again ambiguous at best. U.S. troops who still used the M16 or its subsequent improved models, largely preferred their own weapons; but they developed a grudging respect for the insurgents’ “bullet hoses,” which shot streams of deadly large-caliber bullets at close ranges and seemed impervious to the sand and heat of the Iraqi landscape. The break-up of the Soviet Union, and the dumping of vast arsenals of AK-47s by post-Warsaw-Pact states, together with the near parity that such a simple, cheap AK-47 offered to far more expensive and intricate American weapons, ensured that millions would have access to deadly assault weapons in a way unknown even during the Cold War.

No weapon has killed more human beings than the Soviet-designed AK-47 assault rifle.

Then there is the book by Mikhail Kalashnikov himself, the creator of the AK-47. Now a nonagenarian, Kalashnikov in 2009 won the title, Hero of the Russian Federation, the country’s highest honor. With the help of his daughter Elena Joly, Kalashnikov wrote an autobiography, first published in French in 2003 and now available in English. Kalashnikov fought during the worst months of the German invasion of Russia; in 1941, in a failed counter-offensive, he was almost killed when his Red Army tank regiment was cut off and overwhelmed.

During a long subsequent illness and recovery, Kalashnikov’s innate gun-making talents were noticed. And so, despite his lack of formal design training, he was soon promoted to work with a team of Soviet engineers, quickly emerged as a senior designer, and was mostly responsible for the creation of the AK-47. The most fascinating chapters in Kalashnikov’s story are about the nightmare of life in Stalin’s Soviet Union, in which any achievement, commercial or intellectual, earned envy, which could translate into charges of being a counter-revolutionary, would-be elite—an accusation with often deadly repercussions.

As Chivers and Kahaner also point out, and as is discernible in Kalashnikov’s memoir, his relationship with his own deadly invention over the last two-thirds of a century has proved ambiguous. Kalashnikov is proud of his promotion to the rank of lieutenant general in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, and under Communist rule he was twice honored as a Hero of Socialist Labor. Yet even as Kalashnikov details the horrors of Stalinist Russia that resulted in his own family’s brutal exile, he concludes, “I consider Stalin as one of the great national leaders of the twentieth century, and as a great army leader.” He also seems both to deny culpability for the carnage that the AK-47 wrought, and yet laments that unlike the case of the M16’s creator Eugene Stoner, Kalashnikov did not receive commensurate multimillion-dollar royalties from his design.

One theme of these five diverse books is a sort of appreciation of the American way of war. Shawcross’s work is a paean to well-intentioned American officials, in the face of easy criticism, finding a good balance between security and justice, when both were thought to be impossible in our postmodern world of global terrorism. Cohen is impressed that so many Americans, with so few resources, fought well against better supplied French, and, later, British troops—and suggests that such a frontier-like, pragmatic spirit still infuses a diverse and innovative U.S. military. The authors of the AK-47 books, whether intended or not, paint a rather dark picture of the Soviet state, the post-war Communist world, and the nature of how rogue states and arms dealers developed and dispersed arms often to deadly clients that were the enemies of civilization.

1 William Shawcross, Justice and the Enemy: Nuremberg, 9/11, and the Trial of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (Public Affairs, January 10, 2012).

2 Eliot A. Cohen, Conquered into Liberty: Two Centuries of Battles along the Great Warpath that Made the American Way of War (Free Press, 2011). (Hanson wrote an essay-length review of this book for National Review .)

3 C. J. Chivers, The Gun (Simon & Schuster, 2010); Larry Kahaner, AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War (Wile, 2006); Mikhail Kalashnikov, with Elena Joy, The Gun that Changed the World (Polity, 2007). Hanson wrote a comparative review of these three books for the New Atlantis .

View the discussion thread.

Join the Hoover Institution’s community of supporters in ideas advancing freedom.

- Recent Articles

- Journal Authors

- El Centro Main

- El Centro Reading List

- El Centro Links

- El Centro Fellows

- About El Centro

- Publish Your Work

- Editorial Policy

- Mission, Etc.

- Rights & Permissions

- Contact Info

- Support SWJ

- Join The Team

- Mad Science

- Front Page News

- Recent News Roundup

- News by Category

- Urban Operations Posts

- Recent Urban Operations Posts

- Urban Operations by Category

- Tribal Engagement

- For Advertisers

Lost in Translation: The American Way of War

A nation that makes a great distinction between its scholars and its warriors will have its laws made by cowards and its wars fought by fools. – Thucydides [1]

Strategists and military historians have written prolifically on the topic of an American way of war. With U.S. troops leaving Iraq and with U.S. involvement in Afghanistan winding down, it is perhaps time to examine again the American way of war in order to evaluate its application for future conflicts. Historian Russell Weigley first attempted to define the American approach to conflict in 1973. Many writers have wrestled with this concept since, outlining the numerous characteristics of the American methodology, addressing the distinction between a way of war and a way of battle, and illustrating the advantages and disadvantages of these characteristics in major conflicts and small wars. Within the historiography, authors have also tried to define the characteristics of the strategic American way of war, which includes advancing American national interests through various means, and how our culture and preparation for war actually shape the American strategy.

Taking the differing perspectives in the American way of war historiography into account, one notes there is no authoritative listing of characteristics that define an American way of war; however, extrapolating the commonalities, what emerges is a tactical way of battle and a strategic way of war. The tactical way of battle has an adaptive U.S. military using an aggressive style of force as to overwhelm and destroy enough of the enemy’s forces to acquire a decisive and quick victory with minimal casualties. The seemingly irresistible forces of well-trained professionals use speed, maneuver, flexibility, and surprise. This method of battle is highly dependent on technology and firepower, and has large-scale logistical requirements.

From a strategic standpoint, the American way of war seeks swift military victory, independent of strategic policy success; the desired political and military outcomes do not always align. When analyzed, this style of warfare reveals the American under-appreciation for historical lessons and cultural differences often leads to a disconnect between the peace and the military activity that preceded it. The strategic way of war also includes alternative national strategies such as deterrence and a war of limited aims. Given this model, it appears that there is not a singular American way of war. Rather, the American way of war is twofold: one is a tactical “way of battle” involving a style of warfare where distinct American attributes define the use of force; the other is a strategic “way of war,” attuned to the whims of a four year political system, a process not always conducive to turning tactical victories into strategic success.

Military historians and strategists have endeavored to define the American way of war, or rather define the characteristics of a tactical American way of battle. Weigley in The American Way of War, the pioneering work published in 1973, first described an American way of war, arguing it consisted of a unique American methodology: one of attrition and annihilation. [2] He contends that from the colonial era to the Civil War, while America developed as a new country, its military forces were relatively weak, so it engaged in wars of attrition. An example is George Washington using the interior of the Continent to draw in the British, away from their fleets and resupplies during the War of Independence. From the Civil War through Vietnam, as America developed politically, economically, and militarily, its robust military capabilities allowed a transition from a strategy of attrition to one supporting a strategy of what Weigley calls annihilation . The strategy of annihilation relied on the creation of large masses of forces employing mass, concentration and firepower to use overwhelming power to destroy the enemy. This overthrow of the enemy in costly battles was the surest way to victory and the essential elements of Weigley’s tenets of attrition and annihilation remain as the main legacies and preferences of the American way of war. Weigley misuses the examples of John Pershing wearing down the German Army in 1918 and the U.S. Army’s landing in France to defeat the Germans in 1944-45 in his explanation of annihilation. Weigley confused the term of annihilation with what was actually, attrition, the eventual wearing down of the enemy.

The analysis of an American way of war post-2001 includes many historians, like Brian Linn and John Lynn, questioning the original consensus of an American way of war (made up of Weigley’s annihilation and attrition), and describing more applicable characteristics of a tactical way of battle that better relate to the small wars in American military history. In his book The Echo of Battle: The Army’s Way of War, Linn states that “appreciating a national way of war requires going beyond the narrative of operations, beyond debates on the merits of attrition or annihilation, firepower or mobility, military genius or collective professional ability.” [3] Linn has several objections to Weigley’s classic work, pointing out the infrequency of annihilation and attrition during the eight decades between the end of the Civil War and the middle of World War II. Linn states American soldiers were forced to adapt, improvise, and overcome constraints to practice a way of war better suited to their specific circumstances, which included counterinsurgencies and peace-building and rarely included the characteristics of annihilation or attrition. [4] Linn denies the existence of both an American and Western way of war, stating the American way is more an adaptive way of battle with army officers blending “operational considerations, national strategy, and military theory as they conceived them at the time.” [5]

In terms of a distinct American discourse on war, John Lynn brings up the prevalence of “three related tendencies: 1) abhorrence of U.S. casualties, 2) confidence in military technology to minimize U.S. losses, and 3) concern with exit strategies.” [6] This assertion correctly describes several tendencies in the American way of war. British strategist Colin Gray, similarly to Lynn, includes the same three characteristics in his conceptualization of an American way of warfare. In total, Gray puts forth 13 features that characterize the enduring traditional, and cultural, American military conduct in warfare. [7] Gray’s characteristics show the U.S. military is an institution best prepared for combat against a symmetrical, regular enemy rather than an asymmetrical enemy. The U.S. method of fighting and victory in World War II is preferable to the U.S. method of counterinsurgency in Afghanistan. The apolitical and astrategic characteristics of Gray’s American way of battle emphasize the goal of tactical victory, autonomous from strategic policy and with very little regard to the peace that follows. The quick U.S. tactical victory in Iraq, for example, did not lead to peace and stability in the country directly after.

Strategist H.H. Gaffney argues that a distinctive American way of war emerged in the post-Cold War period. Gaffney analyzed U.S. engagement in nine main cases of combat or near-combat operations, from Panama in 1989 to Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, in order to discern what characteristics made up an American way of war. [8] Gaffney describes the American way of war as “characterized by deliberate, sometimes agonizing, decision-making, careful planning, assembly and movement of overwhelming forces, the use of a combination of air and ground forces, joint and combined, applied with precision, especially by professional, well-trained military personnel.” [9] Historian and editorialist Max Boot similarly describes a “new” American way of war, one that relies on speed, maneuver, flexibility, and surprise, seeking a quick victory with minimal casualties on both sides by being heavily reliant on precision firepower, Special Forces, and psychological operations. [10] Boot uses the recent invasion of Iraq to display the successful use of this new American way of war, which led to the U.S. ambitiously occupying all of Iraq in the matter of weeks with minimal casualties and minimal cost. Both Gaffney and Boot’s characteristics are more complex than Weigley’s original annihilation and attrition tenets. They also describe characteristics that contribute to the tactical win, as these characteristics have at its core the quick resolution of a conflict and the quick return of U.S. forces back to their home bases, which does nothing for ensuring the political objectives of the nation.

When evaluating these various characteristics, the question arises whether or not these characteristics belong to an American way of war or an American way of battle. A way of war would imply a political, economic, social, and military approach to the U.S. view of war, rather than merely a battle focus. Retired army officer and current director of research at the U.S. Army War College, Antulio Echevarria in Toward an American Way of War denies an American way of war, but instead states what we have is an American way of battle. [11] Echevarria believes that until the American way of war develops the capability to make the leap from victory on the battlefield to strategic success, it will remain merely a way of battle. Gaffney also formulates an American way of battle whose characteristics do not tie-in to grand strategy, since these characteristics are simply tactical and do not encompass foreign policy. [12] This leads to the need, in limited war as much as in conventional war, for an all-inclusive approach to achieve military tactical victories, with the hope that these victories, in and of themselves, will help define strategic objectives and translate into something resembling policy success.

The characteristics of the American tactical way of battle are advantages in large-scale, force on force conflicts. The goal of bringing an enemy’s forces to battle in order to crush them in a decisive engagement is a military ideal that generals have sought for centuries, one that has rarely been obtainable. American culture, whether it is through movies, books, games, or folklore, values courage in open battle and bringing an enemy out into the open in order to defeat him. The question is what drives the American conduct towards this big decisive battle. In the books Western Way of War and Carnage and Culture , historian and political essayist Victor Davis Hanson asserts that the Western way of war is one of decisive battles. The classical Greeks invented the idea of representative Western politics as well as the fundamental form of Western warfare, the decisive infantry battle, which was the focus of Greek hoplite armies. [13] Crucial differences, such as discipline, cohesion based on community association, and superior equipment, often ensured Greek victory despite being outnumbered by the enemy. [14] The classical training of America’s Founding Fathers included an imbuement of these ideals of Greek consensual government and by association, the Greek form of fighting. This influence of Greek government and Greek style of fighting led to the American penchant for the big decisive battle. Both consensual government and decisive battle sought the same goal: clear, instant resolution to a dispute. Achieving a clear tactical goal through instant resolution minimizes time and lives lost; because volunteer professional soldiers are expensive to raise, train, and are difficult to replace. A short decisive war for total victory is the preferable American way.

Despite what seems to be the desire for fighting the big, decisive battle, “small wars” are just as much a part of how Americans fight as is conventional war. David Kilcullen argues that since 1816, 83 percent of conflicts fall under “civil wars or insurgencies.” [15] Boot brings up U.S. involvement in small wars, such as the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the Philippine Insurrection in 1899, Bosnia in 1992 and Kosovo in 1999, actually outnumbered U.S. participation in major conflicts. Boot contends these small wars were fought not to attain a decisive victory, but to inflict punishment, ensure protection, achieve pacification, and even to benefit from profiteering. [16] The U.S. involved itself in so many small wars, that the U.S. Marine Corps published the Small Wars Manual in 1940, giving the purposes of small wars as restoring normal government or giving the people a better government than they had before, establishing peace and order, instilling in the people the sanctity of life and property and advantages of civilization and liberty, and whenever possible, making the indigenous agencies responsible for these matters. [17] U.S. involvement in small wars, for the reasons just outlined, had as much or more to do with an American way of war and rise to world power than Weigley's big conventional wars of annihilation.

If one part of the American way of war is the tactical “way of battle,” made up of an aggressive style of force as to overwhelm and destroy enemy forces to acquire a decisive and quick victory with minimal casualties, the other is a strategic “way of war” attuned to the whims of a four year political system and not necessarily able to turn tactical victories into strategic success. In the American polity, the national security strategy tends to chronologically last as long as the four-year presidential cycle (eight years at most), with a President needing to show resolution in order to get reelected. President Obama’s 2010 National Security Strategy has four enduring national interests: Security, the security of the United States, its citizens, and U.S. allies and partners; Prosperity, a strong, innovative, and growing U.S. economy in an open international economic system that promotes opportunity and prosperity; Values, respect for universal values at home and around the world; and International Order, an international order advanced by U.S. leadership that promotes peace, security, and opportunity through stronger cooperation to meet global challenges. [18] The strategic American way of war includes advancing these enduring national interests through various means, whether through all out military intervention, deterrence, limited war, or simply political negotiation. The key remains turning military intervention authorized by the President into quick, tactical military success that, in turn, translates into policy success during the short presidential term .

Looking at the national interests in the National Security Strategy more closely gives us the reasons for U.S. intervention. In terms of security, the U.S. is only one of a handful of countries that can conduct offensive type of operations in not only neighboring, but also in far-off countries. The ability to do this allows the U.S. to strike preemptively, before any fighting occurs on U.S. soil. This policy characteristic of the American way of war is, in fact, a defensive model that seeks to anticipate and strike any threat before it reaches the U.S. [19] In terms of economic prosperity, the National Security Strategy states that American involvement is not necessarily for the exploitation of a local resource, but instead for minimizing disruption to global markets and for the free flow of global resources; economic benefit coming from opening foreign markets to American products and services as well as increasing domestic demand abroad. [20] In terms of values, the American way of war strategically promulgates the advantages of American democratic ideals with American leadership committing itself to the fight to spread democracy and capitalism, which inherently means committing forces to fight against differing ideologies, from Communism during the Cold War to Islamic extremism in Afghanistan.

In terms of achieving national interests, the American way of war includes several different strategic tools beyond military intervention in the big, decisive battle and small wars. It includes diplomacy, deterrence, strategic positioning, embargoes, international coalitions and economic pressure. [21] There is a strong interdependence between military tactics, operations, and strategy, so much so that what soldiers do tactically has a strategic effect, which in turn has political consequences. Civil affairs operations and foreign military training are examples of tactical operations with strategic implications. These missions are, in fact, the military’s version of diplomatic “soft power” and act as a form of diplomatic deterrence. [22] Despite these extra diplomatic tools, the American concept of war rarely extends beyond the winning of battles and campaigns to the work of turning military victory into strategic success. During the post-Vietnam self-examination, U.S. strategists recognized winning campaigns did not equate to winning wars, which meant accomplishing one’s strategic objective. One of the most noted examples of this is the Tet Offensive of 1968. The North Vietnamese and their associated forces adopted a conventional strategy, which the Americans defeated through decentralized military operations. Although the offensive was a tactical defeat for the Communist forces, the scope and ferocity of the campaign discredited President Johnson’s characterization of progress in Vietnam throughout the closing months of 1967. The offensive became a strategic victory for the Communist forces with President Johnson’s announcement that he would not run for re-election and with the next President, Nixon, focusing on an exit strategy from Vietnam. [23] One of Clausewitz’s maxims states “War is not merely an act of policy but a true political instrument, a continuation of political intercourse, carried on with other means…The political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it, and means can never be considered in isolation from their purpose.” [24] This consistent disconnect between policy and on-the-ground operations must change so that the American way of war can integrate the use of the military into a consistent and unambiguous national strategy, one that will let American politics capitalize on tactical victories.

The interpretation of current conflicts through discourse is another factor that shapes the strategic American way of war. Lynn relates the warfare of a particular era to its own unique cultural dialogue, “the complex of assumptions, perceptions, expectations, and values” that the particular society holds about war and warriors. [25] He argues that discourse does not remain the same over time because of changing circumstances and evolving cultural norms. Thus the role of culture shapes combat and the interpretation of that combat just as preparation for war shapes the strategic American way of war. The U.S. democratic culture and emphasis on free speech allows its many competing interest groups to join in on the intellectual debate during preparation for war. This peacetime intellectual discussion by the intelligentsia and pundits in the media, reflections on wartime service by the military, and the given American attitude toward war combine to shape the strategic American way of war. This discourse also includes the U.S. military regularly and methodically conducting after action reviews in order to study military history to not repeat mistakes, to improve theory, and change or shape needed doctrine. [26] Though advantageous to a certain extent, competing interest groups and differing ideologies in our pluralist democracy inhibit coherent strategy making, but one idea remains constant, if Americans must take up arms for a cause, they demand a quick and decisive victory.

Thus, the American way of war is twofold: a tactical “way of battle” involving an aggressive style of warfare to overwhelm and destroy enemy forces to acquire a decisive and quick victory with minimal casualties, and a strategic “way of war” where the desired political and military outcomes do not necessarily align. Weigley first attempted to define the American approach to conflict through the characteristics of attrition and annihilation. Subsequent historians have either enumerated as many as 13 characteristics to define the American way of battle or on the other hand denied the existence of it. The characteristics of a way of battle show an institution with a preference for combat against a symmetrical, regular enemy rather than an asymmetrical enemy, despite our history of small wars, counterinsurgencies, and nation building. In terms of achieving our national interests, the strategic American way of war includes several tools beyond military intervention to pursue our enduring national interests of security, prosperity, values, and international order, to include discourse, which is one of the elements that shape our way of war. There will continue to be a need for a holistic approach to capitalize on military tactical victories in order to achieve these national interests and for a President to declare policy success.

Defining the American approach to conflict and knowing its strengths and weaknesses will allow the U.S. to be more effective in future fights. Current American popular perception of what is occurring in Iraq and Afghanistan is that American forces are conducting High Intensity Conflict (HIC), the idea of World War II style fighting where American forces win battles, declare victory, and then leave. Not only is this inaccurate for our times, but also for many of the small wars American forces have conducted in the last 150 years. These small wars might have had a HIC component to it, but it was short and quickly followed by counterinsurgency, stability operations, and/or nation-building. Future fights will continue to include a mixture of conventional HIC operations, counterinsurgency fights, and stabilization efforts.

If there are two things that the strategic American way of war must address immediately, it is the consistency in the application of military intervention and having a standard of selectivity. Former Secretary of State Kissinger argues for the need for criteria, as indiscriminate involvement would drain a crusading America and isolationism would mean giving up security to the decisions of others. “Not every evil can be controlled by America,” he wrote, “even less by America alone. But some monsters need to be, if not slain, at least resisted.” [27] Strategically applying military intervention and selectively involving ourselves in future situations in pursuit of our national interests will do the most to unify our disparate American tactical way of battle and strategic way of war.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boot, Max. Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (New York, NY: Basic Book, 2002).

Clausewitz, Carl von. On War , Michael Howard and Peter Paret trans. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976).

Hanson, Victor Davis. Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power (New York, NY: Doubleday, 2001).

Hanson, Victor Davis. The Western Way of War (New York, NY: Suffolk, 1989).

Kilcullen, David. Counterinsurgency (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy , (New York, NY: Simon & Shuster, 1994).

Linn, Brian. The Echo of Battle: The Army’s Way of War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007).

Lynn, John A. Battle: A History of Combat and Culture (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2003).

Nye, Joseph Jr. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York, NY: PublicAffairs, 2004).

Various. “Part I – An American Way of War.” In Rethinking the Principles of War , Edited by Anthony D. McIvor, 13-140. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2005.

Weigley, Russell F. The American Way of War: A History of United States Military Strategy and Policy (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1977).

Journal Articles

Boot, Max. “The New American Way of War.” Foreign Affairs , (July/August 2003).

Echevarria II, Antulio J. “An American Way of War or Way of Battle?” (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2004).

Gaffney, H.H. “The Amercan Way of War through 2020” (Alexandria, VA: Center for Strategic Studies, CNA Corporation, 2006).

Gray, Colin S. “Irregular Enemies and the Essence of Strategy: Can the American Way of War Adapt?” (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2006).

Linn, Brian M. “‘The American Way of War’ Revisited,” The Journal of Military History , Vol. 66, No.2 (April 2002).

Electronic and Web-based Sources

The U.S. Army’s After Action Reviews: Seizing the Chance to Learn. Excerpt from: David A. Garvin, “Learning in Action, A Guide to Putting the Learning Organization to Work” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000), 106-116. http://www.wildfirelessons.net/documents/Garvin_AAR_Excerpt.pdf (accessed Nov 9, 2011).

Huntington, Samuel P. The Problem of Intervention, A Conversation with Samuel P. Huntington, (Institute of International Studies, UC Berkeley, 1985) http://globetrotter.berkeley.edu/conversations/Huntington/huntington-con3.html (accessed Nov 9, 2011).

National Security Strategy (White House, May 2010) http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/national_security_strategy.pdf (accessed Nov 9, 2011).

Thucydides Quote http://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/957.Thucydides (accessed Nov 9, 2011).

Willbanks, James H. “Winning the Battle, Losing the War,” New York Times , March 5, 2008 http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/05/opinion/05willbanks.html (accessed Nov 9, 2011).

[1] Thucydides Quote http://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/957.Thucydides (accessed Nov 9, 2011).

[2] Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War: A History of United States Military Strategy and Policy (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1977), xxii

[3] Brian M. Linn, The Echo of Battle: The Army’s Way of War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 3.

[4] Brian M. Linn, “‘The American Way of War’ Revisited,” The Journal of Military History , Vol. 66, No.2 (April 2002), 503.

[5] Ibid, 530.

[6] John A. Lynn, Battle: A History of Combat and Culture (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2003), 321.

[7] Colin S. Gray, “Irregular Enemies and the Essence of Strategy: Can the American Way of War Adapt?” (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2006), 30.

The 13 characteristics and their definitions are: Apolitical, the U.S. military wages war for the goal of victory with very little regard to the peace that follows; Astrategic, war is an autonomous activity with no connection to strategic policy; Ahistorical, as a new nation Americans are not culturally attuned to lessons nor insights from history; Problem-Solving/Optimistic, we believe there is a solution, whether through foreign policy or use of the military, to even unsolvable dilemmas; Culturally Ignorant, Americans lack cultural empathy and do not understand the beliefs, habits, and behaviors of other cultures; Technologically Dependent, the U.S. depends exceedingly on technological advances and mechanical solutions; Firepower Focused, sending mass firepower despite the circumstance is preferable to sending vulnerable soldiers; Large-Scale, the U.S. is not materially minimalistic, but rather equips, mobilizes, and wages war reflecting its wealth; Aggressive/Offensive, the preferred style of operation is an aggressive offensive style due to geopolitics, culture, and material wealth; Profoundly Regular, the U.S. is an institution best prepared for combat against a symmetrical, regular enemy; Impatient, the American approach to warfare is that it must be decisive and concluded as rapidly as possible; Logistically Excellent, the U.S. has a large logistical footprint which means able logisticians, but also means a lot of guarding and isolation of American troops; and lastly Highly Sensitive to Casualties, Americans are very averse to a high rate of military casualties.

[8] H.H. Gaffney, “The American Way of War through 2020” (Alexandria, VA: Center for Strategic Studies, CNA Corporation, 2006), 3. The nine operations are: Panama in 1989, Desert Shield/Desert Storm in 1990/91, Somalia in late 1992, Haiti in 1994, the Deliberate Force air strikes in Bosnia in 1996, the Desert Fox strikes on Iraq in 1998, Kosovo in 1999, Afghanistan beginning in October 2001, and Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003.

[9] Gaffney, “The American Way of War through 2020” 1.

[10] Max Boot, “The New American Way of War.” (New York, NY: Foreign Affairs, July/August 2003).

[11] Antulio J. Echevarria II, “An American Way of War or Way of Battle?” (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2004).

[12] Gaffney, “The American Way of War through 2020” 18.

[13] Victor Davis Hanson, The Western Way of War (New York, NY: Suffolk, 1989), 223-225.

[14] Victor Davis Hanson, Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power (New York, NY: Doubleday, 2001), 3. “Such unique Hellenic characteristics of battle – a sense of personal freedom, superior discipline, matchless weapons, egalitarian camaraderie, individual initiative, constant tactical adaptation and flexibility, preference for shock battle of heavy infantry – were themselves the murderous dividends of Hellenic culture at large. The peculiar way Greeks killed grew out of consensual government, equality among the middling classes, civilian audit of military affairs, and politics apart from religion, freedom and individualism, and rationalism.”

[15] David Kilcullen, Counterinsurgency (Oxford, 2010) ix-x.

[16] Max Boot, Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (New York, NY: Basic Book, 2002), xvi.

[17] United States Marine Corps, Small Wars Manual (New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing, 2009), 32 (first published: Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1940).

[18] National Security Strategy, (White House, May 2010) http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/national_security_strategy.pdf (accessed Nov 9, 2011).

[19] The Israelis also have a similar strategy integrated into their operational paradigm.

[20] Ibid, 32.

[21] Ibid, these various methods are discussed throughout Section III, Advancing Our Interests, 17.

[22] Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York, NY: PublicAffairs, 2004).

[23] James H. Willbanks, “Winning the Battle, Losing the War,” New York Times , March 5, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/05/opinion/05willbanks.html (accessed Nov 9, 2011).

[24] Carl von Clausewitz, On War , Michael Howard and Peter Paret trans. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 87.

[25] Lynn, Battle: A History of Combat and Culture , xx.

[26] The U.S. Army’s After Action Reviews: Seizing the Chance to Learn. Excerpt from: David A. Garvin, “Learning in Action, A Guide to Putting the Learning Organization to Work” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000), 106-116. http://www.wildfirelessons.net/documents/Garvin_AAR_Excerpt.pdf (accessed Nov 9, 2011).

[27] Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy , (New York, NY: Simon & Shuster, 1994), 833.

About the Author(s)

Lieutenant Colonel Rose Lopez Keravuori is a US Army Reserve Military Intelligence officer serving as a Battalion Commander at Ft Meade, MD. She was commissioned in the US Army from the United States Military Academy in 1997, and earned a Masters in Diplomatic Studies from the University of Oxford in 2014. She is the CEO and Founder of ROSE Women, LLC a business targeting human trafficking and focused on empowering women through USAID and Dept. of State contracts. She enjoys reading and studying military history as a hobby.

The study of this topic…

The study of this topic requires the analysis of various sources, therefore it arises the need for a correct translation. For this I use the https://www.translate.com/ It is a trusted resource in the market for professional manual translations, software localization and advanced language services. Trusted by leading enterprises and companies around the world, the company helps clients succeed in international markets with quality tools and talented people.

This article provides an interesting view of a topic that has garnered significant interest since the publication of Weigley’s The American Way of War. The author demonstrates that the majority of the work on the topic of an American way of war falls into two broad categories. The first category describes a “strategic way of war” and the second a “tactical way of battle.” The title of this article accurately articulates the erroneous categorizing of all these works under the single heading of “a way of war”. Colin Gray in War, Peace, and International Relations highlights an important difference between the term “war” and “warfare”. War, he argues, “is a legal concept, a social institution, and is a compound idea that embraces the total relationships between belligerents.” In contrast, he defines warfare as “the actual conduct of war in its military dimension.” He claims the two concepts are vitally different and “often the two are simply conflated.” According to Gray, the conduct of War is not about fighting. The fighting is important, “but it can only be a tool, a means to a political end.” Confusing the term warfare with waging war highlights the difficultly that some states have in leveraging military victory to achieve strategic success. Military victory alone, even when it supports the strategic objectives, is not enough to achieve strategic success. In such cases, lack of success is not a military failure but a strategic failure. Russian military theorist Aleksandr A. Svechin recognized that “no amount of operational proficiency could overcome strategic miscalculation regarding the nature of the war embarked upon.” Svechin believed that the conduct of strategy was not in the province of a military commander but of “integral military leadership” which combined the political, military, and economic leadership under a chief of state. Thus discussing “a way of war” utilizing only examples of the military dimensions of a conflict confuses the terms war and warfare as well as the responsibilities of all the national actors that are involved in the conduct of war.

I had much the same reaction to this article, especially with respect to point #3 above. But the central issue comes forward in Hubba Bubba's point #6: what is the role of doctrine, and are we even knowledgeable enough about the doctrine - and its antecedents - to apply it in the context of "lessons learned", or have a debate on what doctrine recommends. When NTC went in, the one favor that the OC teams did TRADOC was to take what was presented in the "How to Fight" manuals seriously. Very quickly, theyu discovered that there was a range in which the doctrine worked, and if you went outside that range, bad things happened. So the net effect was to reinforce doctrine and challenge it at the same time. The truth is that we both need the soldiers and we need the doctrine. The crack at Jomini is symptomatic of the problem - at least Jomini tried to distill what he had experienced of war into something theoretically useful, something that could be demonstrated as true or false in the light of continued experience. Archtypes and metaphors have exactly this virtue, that they enable the communication of experience across time and culture. How else can we profit from studying the past - even our own past experiences ? Yes, it is common sense to opine that a program of social change imposed from outside requires a long term commitment of resources and a determination not to give up. Even so, one should not imagine that an abandoned project will leave no marks. Building roads in Afghanistan is one of the more concrete and irreversible tokens of America's presence there. Why not accept this for what it really is ?

I might be a little harsh in this critique, but this article looked to me like something reincarnated from an Intermediate Level Education (ILE) paper that simply summarizes the reading requirements from any given course on strategy. Here are some thoughts after chewing on this one this morning… 1. In framing problems, to include understanding whether there is some American "way of war" in a strategic, tactical (or operational- left out entirely by the author) sense, one starts with describing or making sense of the problem. Subsequently, they move to an analysis phase, where they apply critical and creative thinking, and lastly they hope to achieve synthesis. This article is firmly rooted in the "description" phase which ultimately reads like consolidated cliff notes on several prominent authors on American military culture, strategy, and tactics. I tried to find the thesis for this one, and just could not nail it down. I was left asking, "so what?" 2. The article alleges that the strategic way of war for America rests in being "attuned to the whims of a four year political system." I do not think the author clearly identifies this theory, backs it up, or links it to the supporting documents and organizing logic. Was this the thesis? I agree that our political masters swap out on a general 4-8 year cycle, but most military conflicts span several democratic elections, and do not seem to change too radically. Johnson already wanted out of Vietnam before the Tet Offensive- Nixon’s election campaign was no different a strategy than many others during time of war; one of the cited authors (Linn) also wrote a good book on the Philippines War. He mentioned the fierce race between McKinley and Bryan; indeed this was a counterinsurgency “small war” as well and Bryan attempted to do what any rival politician does- argue for another solution for American “victory.” Bryan lost anyway, but one might generalize the entire Cold War period as a continuous “strategy” of sorts that espoused the concept from the Kegan Telegram/NSC-68 phase of “containment” and evolved along several harmonious threads forward along multiple presidencies. Détente, and Reagan’s revival after Carter (I will cede that the Carter Administration was indeed a strategic blunder of enormous proportions) all followed a basically unified strategy that supported long-term American goals.

3. The author jumps from tactical to strategic theory in a way that makes me ponder why she never addresses the operational level of war? One should not attempt to suggest “perhaps it is time to examine again the American way of war in order to evaluate its application for future conflicts” if one is going to ignore the major linking concept between tactical and strategic planning/execution! Now, if the author contends that unusual position that there is no “operational level”- she could state that in her introduction to frame her organizing logic a bit tighter.

4. “In terms of values, the American way of war strategically promulgates the advantages of American democratic ideals with American leadership committing itself to the fight to spread democracy and capitalism, which inherently means committing forces to fight against differing ideologies, from Communism during the Cold War to Islamic extremism in Afghanistan.” - Really? Should we consider the term “Banana Republic” in the context of our 20th century foreign policy actions in South America? How many democratic nations did we collapse or inhibit out of our overarching fear of Communism, or the lobbying interests of capitalist venture that might lose their profit through nationalization efforts? We like to claim that we spread democracy, except many times we enforce dictators, be they African, South American, or Middle Eastern and help us with other more important foreign policy ventures.