- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

Design Thinking for Higher Education

To meet the challenges of a new era, universities should redesign their core functions while also creating capacities to reach emerging and underserved markets. Open access to this article is made possible by BYU-Pathway Worldwide & ASU's Center for Organization Research and Design.

- order reprints

- related stories

By Clark G. Gilbert, Michael M. Crow & Derrick Anderson Winter 2018

Higher education has entered into an era of transition. Changing student demographics, rapidly evolving stakeholder demands, and new technologies are requiring universities to reconsider abiding assumptions about geography, time, and quality. We expect that in the coming years, long-standing models of higher education that prefer tradition and stability will be supplemented, if not displaced, by new models that embrace organizational innovation, responsivity, and adaptation.

Design thinking offers important pathways for shaping these important new models. Organizational change can embody deliberate choice that purposefully shapes the object and direction of the change itself. A design perspective suggests that there are architectural choices to be made about what the organization seeks to accomplish and how it is organized to achieve those ends. Many industries, especially higher education, confront challenges from both legacy and emerging markets. Few universities, if any, should be willing to ignore one market in favor of the other, since legacy and emerging markets are both vital and can play important roles in fulfilling higher education’s social mission.

We have found that a dual transformation design strategy has proved especially effective for addressing both legacy and emerging markets. According to this approach, operations acting in parallel—one to develop strategies that optimize the core organization to become more responsive to the new profile of demands it faces, and a second to design and implement disruptive innovations that provide a basis for future growth, agility, and responsivity. 1 We provide here a set of recommendations for how dual transformation can be implemented in higher education.

While we reference many colleges and universities, we focus on how our own institutions, Brigham Young University-Idaho and Arizona State University , have embraced these principles of transformation. These two institutions are important as case studies for their similarities as much as their differences. Brigham Young University-Idaho (BYU-Idaho) is a private religious four-year college established less than two decades ago from the dramatic reorganization of a distinguished residential junior college. Alternatively, Arizona State University (ASU) is a comprehensive public research university born from a regional teachers’ college that now stands out among national universities for its commitment to both access and excellence.

Despite these important historical and structural differences, both universities have adopted design models that facilitate innovation along multiple, seemingly competing trajectories. Both are committed to the success of all students. And both have undergone transformation in their efforts to be continuously responsive to the new spectrum of challenges facing higher education.

Tech Meets the Medieval University

Knowledge is the core of higher education. The roots of modern higher education date back to 11th-century Europe, where the first universities were formed from guilds of student practitioners and expert instructors. In this system, knowledge was accumulated by experts and passed to apprentices, a tradition that to this day informs the self-governing, faculty-centric nature of university design.

Tradition casts a long shadow over higher education. For generations, universities have been able to fulfill their scientific and socioeconomic missions by replicating past success. As a consequence, many of today’s colleges and universities are internally driven by the same structures of power and decision making over resources, the means of production, and sources of authority and legitimacy. Thus, the design logic that has prevailed in higher education can sometimes encourage uniformity and discourages innovation. From the number of books in libraries to the number of hours that students spend in seated lectures to what constitutes a degree, there are widespread pressures to conform.

This rigorous standardization has served higher education well until this point. It helped ensure quality through centuries of upheaval marked by the rapid proliferation of new institutions. However, the modern era demands greater flexibility and innovation. Factors that aim to ensure quality, such as accreditation, must avoid becoming too focused on examining a narrow set of academic processes. An overemphasis on process conformity arguably limits exploration, differentiation, and, in some cases, even system-wide quality.

What’s more, the challenges facing higher education are historically unique. Rapid, ubiquitous, and accelerating technological progress is now part of the human condition. While intergenerational technological progress has been observed since the industrial revolution, the benefits of progress have primarily owed to the wealthy. But we are swiftly approaching the point where the benefits of technological advancement will (or through design choices easily could) reach everyone, even the poor.

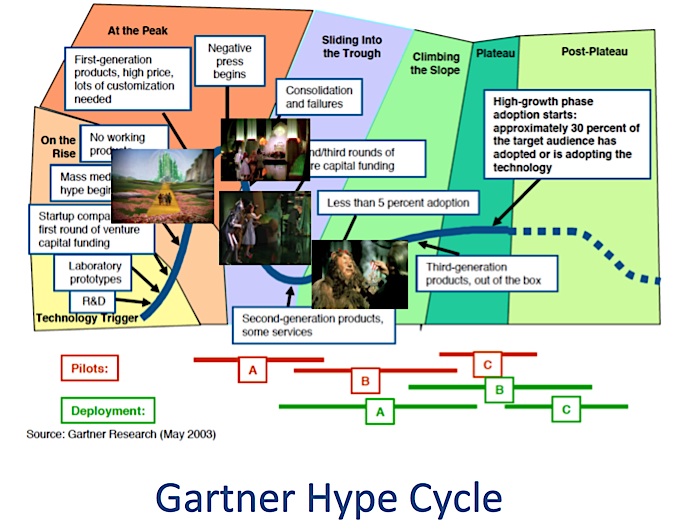

We also know that society’s capacity to absorb new technologies is growing. While telephones took 25 years to be adopted by 10 percent of the American population a century ago, tablet computers achieved that level of market penetration within five years. 2 And while the personal computer reached one quarter of the American population in 16 years, the Internet took only seven. 3

As a consequence of rapid technological progress and the increased capacity to integrate new technologies into already complex social systems, we now have greater access to information and tools to collect, transmit, and process information. In years past, trade skills could be expected to transfer from generation to generation. Today it is estimated that 65 percent of schoolchildren will work in a job or career that doesn’t presently exist. 4 For the first time in human history, how people live and work is fundamentally changing within the duration of a single lifespan or less.

Coupled with widespread technological change are steadily increasing expectations for social mobility. According to a recent report by the Brookings Institution, the global middle class is growing by about 140 million people per year and accounted for approximately 3.2 billion people at the end of 2016. Yet, in the United States, real access to college, measured in terms of student success and completion, remains the province of wealthy families. While college attendance for students in the bottom quartile of family income has increased from 28 to 45 percent since 1970, this figure is dwarfed by the 82 percent of students from families in the top quartile who attend college.

In terms of college graduation, the gap is even more dramatic: 77 percent of US students from the top family income quartile will go on to earn a bachelor’s degree by the age of 24, compared with just 9 percent of students from the bottom quartile. 5 In other words, students from the highest-income families in America are eight times more likely to graduate from college than students from the poorest families. Thus, the capacity of American higher education to contribute to American democracy is inherently limited, arguably by design.

Moving Toward Design Solutions

Taken together, these technological and sociological trends suggest that in maintaining their value to society, many colleges and universities will need to teach new material to new types of students at new, large scales. Doing so will require entirely new design models. However, in the face of rapid social change, the trend among many in higher education has been to reinforce traditional models. Some of this active entrenchment comes from pouring resources into technology that perpetuates the traditional classroom model and fails to harness the unique benefits of online and distance learning. University leaders also choose to invest in amenities and efforts to bolster rankings in order to increase enrollment—at the expense of innovations with long-term, real student impact.

We believe that the problems that beset colleges and universities are the result of failures to lead design-driven adaptation. As a first step in formulating design solutions, we recommend viewing the challenges posed by both legacy and emerging markets as independent ones, and assigning specific responsibility for innovation for each challenge to differentiated functions of the university. While this is only one approach, it offers important opportunities to reinvigorate the core of the academic institution while allowing new organizations to explore and innovate areas that are either ignored or needlessly bound by tradition.

In general terms, the dual transformation framework we advocate encourages organizations to embark on two separate but carefully connected efforts. Transformation A is a redesign of the core organization to improve capacities in teaching and research. Transformation B entails carefully designing a capacity to respond to emerging opportunities or social demands. In the context of higher education, through Transformation A, academic organizations must lower the costs of (or even exit) those offerings that do not sufficiently differentiate them and invest in areas that will reposition core teaching and research in ways that will drive competitive advantage in an ever-changing landscape. 6 Thus, Transformation A is about deliberate choice that every university confronts, where failure to choose is a de facto choice for expensive mediocrity.

Transformation B, by contrast, should be treated as a distinct opportunity focused on entirely new models and separate student markets. Examples of Transformation B innovations include online learning, distance education, and other forms of increased access for students. The higher education sector offers numerous case studies of institutions that have undertaken successful transformations along one or another of these dimensions. A smaller number of cases—including BYU-Idaho and ASU—provide examples of successful transformation along both dimensions.

Transformation A in Differentiated Research

While not all universities are research intensive, those that are can achieve dramatic gains in research productivity by focusing on their core strengths and building up programs in which they have natural advantages. Since 2002, when this paper’s coauthor Michael Crow became its president, Arizona State University has increased research expenditures by a factor of four, constituting the highest growth rate of any university research enterprise in the United States. But even as it has expanded its research investment, it has done so by consistently considering “place.” For 15 years, ASU has strategically increased capacity in fields that are accessible in and relevant to Arizona and the Phoenix metropolitan area, such as water scarcity and resource management, solar and thermal energy technologies, and sustainable urban development; merged programs and departments to create new synergies—for example, fusing geology and astronomy into a School of Earth and Space Exploration; and employed the participation of key industries in sponsored projects such as ASU LightWorks, a multidisciplinary effort pursuing breakthroughs in solar energy and sustainable fuels. 7

As a consequence of executing a carefully designed strategy, the research enterprise at ASU has expanded from approximately $123 million in FY2002 to nearly $520 million in FY2016 with remarkable efficiency. For example, the size of the faculty has remained nearly constant since 2002. According to recent data from the National Science Foundation, ASU now ranks tenth of 724 universities without medical schools in total research expenditures—ahead of California Institute of Technology, Princeton University, and Carnegie Mellon University.

But more than simply expanding research investment, ASU has chosen to differentiate itself from its peers by bringing to its research clarity of purpose through a focus on use-inspired research. Accordingly, for ASU, the notion of “place” is not just geographic; it relates also to seeking a unique thematic position within the broader national innovation system. Other universities have also bene ted from committing themselves to a thematic interpretation of place. For example, Rockefeller University has achieved and maintained its status as a global leader in biomedical research and training while operating pursuant to its motto, “Science for the benefit of humanity.” And Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, has incorporated the cultural and religious priorities of its Latter-Day Saints community to pursue a leadership role in research pertaining to religious freedom, family social science, and poverty alleviation.

In pursuing design strategies for research differentiation, universities assess the promise of a research enterprise relative to their unique institutional assets rather than muddling through a medley of scientific fields where their capacity to maintain the path of academic inquiry becomes fragmented. As a consequence, new lines of inquiry can be discovered, and universities with otherwise limited resources can assume leadership roles in new disciplinary fields.

Transformation A in Teaching and Learning

On the teaching side, many universities have unfortunately responded to rising costs and decreasing state support by increasing selectivity or passing an excessive share of instructional costs to students and their families. Whether through high costs or highly selective admission standards, exclusivity narrows the pool of admitted students to those who are almost certain to succeed. Instead, we think universities should be de ned by who they include and how those institutions improve their students’ chances of success.

Accordingly, Transformation A calls for carefully planned innovations that allow for gains in student outcomes without succumbing to the magnetism of exclusivity. For example, rather than increasing selectivity and turning away students who are less likely (or unlikely) to graduate, the University of California, Riverside (UCR), has made inclusivity a core part of its identity: 57 percent of UCR students are low income (federal Pell Grant eligible) or first-generation students. Notwithstanding the abundance of evidence proving that these students are less likely to succeed, federal data show that 90 percent of UCR students persist after their freshman year and 68 percent of students graduate in six years—26 points higher than the national average.

The reasons for UCR’s success graduating students includes a combination of targeted financial aid for needier students (students with a family income under $80,000 per year pay no tuition); 8 a robust suite of student services, which emphasize peer ties between students through learning communities; and opportunities for undergraduate students to partner in faculty-led research. (More than 50 percent of undergraduates undertake a research experience.) 9 By taking a different tack from competing institutions, UCR has shown that it is possible to maintain robust growth, hold down costs, and drive success for students of all demographics.

BYU-Idaho has also undertaken a major transformation of its teaching enterprise. Created in 2000, BYU-Idaho grew out of Ricks College, a two-year junior college, to become a four-year, bachelor’s-degree-granting institution that primarily focuses on access, student success, and teaching excellence. Designed to “have a unique role and be distinctive from” its sister institutions within the BYU system, BYU-Idaho has managed to grow its enrollment and keep costs low by upending the traditional academic calendar in favor of a three-track, year-round calendar. Applicants to BYU- Idaho are assigned to a cohort that begins in either a fall, winter, or spring term and remain with their cohort through graduation, with each cohort assigned to attend only two of the three terms.

Since the new system was announced in 2000, total annual enrollment on campus has increased from fewer than 15,000 to more than 30,000 students, while the relative cost per student has declined. In other words, because each cohort attends only two of three available semesters each year, one-third of the students are away from campus at any point in time—effectively growing the capacity of the school by 50 percent without adding infrastructure. Rather than taking the downtime that many schools have in the summer, BYU-Idaho operates year-round, always at full capacity. The university keeps the system flexible by allowing students to take online courses at any time, regardless of their cohort calendar, and offering qualified students the option to enroll year-round to accelerate graduation. 10

Not only has its focus on a teaching-oriented faculty and a three-track calendar addressed the affordability and access challenges of higher education, but also it has enabled BYU-Idaho to zero in on student outcomes. Even though the university has a policy of virtual open enrollment and more than 50 percent of its students receive federal financial aid, BYU-Idaho consistently has nearly a 20 percent higher graduation rate than the national average, well above that of its regional peers. 11 Moreover, BYU-Idaho students graduate in the 82nd percentile in the Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA) for critical thinking and writing, while their incoming credentials suggest that they should only achieve the 65th percentile. For BYU-Idaho, the focus on teaching has not only expanded access and reduced cost but also increased quality by concentrating on meaningful student outcomes.

At ASU, teaching is organized according to four Teaching and Learning Realms. Realm 1 pertains to campus-based immersion learning where 3,400 faculty members interact closely with more than 71,000 students. Realm 2 includes fully online delivery of degree programs offered by campus colleges and departments. Realm 3 provides open scale digital immersion learning (sometimes termed massive open online courses or MOOCs), and Realm 4 focuses on “education through exploration,” including virtual field trips, game-based learning, and personalized learning.

Technology-driven enhancements cut across all four Realms, but the focus of Transformation A is Realm 1, where carefully implemented strategies have allowed for dramatic growth in enrollment, especially of disadvantaged populations, along with improvement in retention and graduation rates. For example, ASU’s eAdvisor platform, implemented in 2007, uses assorted data points to help keep students on track for degree completion and automatically implements interventions when a student fails to progress. Other innovations are structural, such as partnerships with community colleges that accommodate the careful preparation of students and seamless transfer pathways. Such innovations have helped ASU increase the number of degrees awarded at its metropolitan campuses from 14,444 in 2007-08 to 18,254 in 2015-16, while also raising its public profile. ASU has received a top-five ranking in best-qualified graduates from The Wall Street Journal in 2010; a top-10 ranking in graduate employability from the Global University Employability Survey in 2016; and a number-one ranking in the United States for innovation in 2016, 2017, and 2018 by U.S. News & World Report .

Transformation B for New Opportunities

While Transformation A innovations focus on the established core functions of universities, Transformation B generates entirely new educational models that could not emerge meaningfully from the traditional academic organization. In higher education, this is often manifested through online programs targeting nontraditional student populations or new technology-driven modes of learning.

Prior to the 1980s, higher education was focused almost exclusively on young learners. But now students who attend four-year institutions and live on campus make up only a portion of all US undergraduates. Of the more than 20 million undergraduates attending college in the United States, more than 40 percent are over the age of 25, and this figure is predicted to increase, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Technological and social changes are also driving the emergence of new student demographics from diverse locations as well as a broader spectrum of socioeconomic backgrounds. Many of these students face barriers such as the need to balance studies with work and family obligations, high educational costs, transportation and logistical difficulties, a lack of access to information about educational opportunities, and a lack of guidance tailored to their unique needs. Many of these barriers also correspond to the ways in which these students learn that are fundamentally different from the experience of traditional campus-bound college students. For example, midcareer students bring to the classroom work experiences that not only are foreign to traditional students but may be the exact experiences that the classroom is preparing them to confront.

Southern New Hampshire University stands out as an example of a forward-thinking institution that reorganized itself around online education to reach the nontraditional student market. Founded in 1932 as the New Hampshire Accounting and Secretarial School, SNHU since 1995 has expanded its reach to nontraditional students worldwide with the founding of an online distance learning program, SNHU Online. Within six years of launch, the program included students from 23 time zones. Today, as a consequence of the success of SNHU Online, the university enrolls about 85,000 students. Most recently, SNHU launched College for America , a subsidiary nonprofit institution that offers nontraditional learners degrees in competency-based tracks, wherein students advance by demonstrating proficiency through applied projects rather than traditional coursework.

SNHU Online was created as a differentiated organization dedicated to serving the unique demands of emerging online markets but carefully connected to the core university for the assurance of quality. This strategy of establishing a separate organization with careful integration with the core university is not unique. Even in major public universities where significant success with online education has occurred, it has often come when leaders have been willing to create distinctive organizations that could focus not only on the new models tied to online learning but also on the distinctive needs of online students.

Pennsylvania State University is one of the largest universities in the United States, and serving nontraditional students from Pennsylvania’s rural population has long been a part of its identity. In 1998, Penn State launched its World Campus , one of the nation’s first online programs, which has since grown to o er 125 degrees, certificates, and minors and now has more than 12,000 students enrolled in all 50 states and more than 50 countries. 12 In 2013, Penn State announced that it would invest $20 million to facilitate the expansion of World Campus, which it plans to grow to 45,000 students by 2023. 13

Like SNHU Online, World Campus exists as a separate unit of the university with carefully designed integrations with other core university units. A key feature of the World Campus that contributes to its business success and 95 percent student-satisfaction rate is the program’s integration with central academic units through revenue sharing. 14 When students enroll in World Campus courses in a given subject, the college that offers the course keeps a portion of the discretionary revenue, providing incentives for academic units to promote and accommodate World Campus growth and ensure that students receive the same level of support as on-campus students. In recent years, the World Campus has played a critical role in growing Penn State’s system-wide enrollment even as population decreases in rural areas and drastic decreases in state funding threaten the viability of its branch campuses. 15

Other universities have taken a more targeted approach to growing specific nontraditional markets. For BYU-Idaho, this began with a focus on reaching students who were not being served by the existing BYU system because they did not feel that they could afford college or because, in some cases, they did not feel that they could succeed. In 2009, the university launched a new program called Pathway to target these students. It provides a one-year preparatory experience to ready students for college.

Rather than teaching traditional general education courses, the program focuses on study skills and self-organization. Instead of the traditional freshman English and math, the program teaches (to similar outcomes) résumé and cover letter writing, and family financial literacy. The students work through the material in interactive, cohort-based online courses and then gather weekly in small groups at local religious centers. While the program started with just 50 students in three pilot locations, today it has grown to reach tens of thousands of students in more than 500 locations around the world.

Similarly, BYU-Idaho’s online degree programs start with certificates and associate degrees, rather than maintaining the almost exclusive focus on bachelor’s degrees at more traditional universities. This has allowed many students to advance more quickly in the workforce and access a more applied curriculum than a traditional campus-centric model of higher education would do. It is important to note that both the Pathway and online degree programs were structured as separate operating entities within BYU-Idaho so they could focus on the distinctive needs of these online students. By helping students build confidence in their early academic efforts, pricing the program at less than $75 a credit hour, and allowing students to access education locally, the Pathway program and the BYU-Idaho online degree programs have grown to more than 35,000 students annually. This combined annual enrollment now exceeds the total annual student enrollment of the residential campus in Rexburg, Idaho. This past February, BYU-Idaho’s governing board elected to create a new institution, BYU-Pathway Worldwide, to focus on serving the needs of these nontraditional students.

Transformation B at ASU cuts across multiple realms of teaching and learning, each pushing further into the frontiers of innovation in higher education. Like BYU-Idaho, ASU’s Transformation B is coordinated primarily through an independent unit dedicated to the cultivation of technology-intensive disruptive ventures. ASU founded this unit as EdPlus . In what is termed Teaching and Learning Realm 2, traditional undergraduate and graduate degrees are offered in online formats. Since its inception in 2009, ASU Online (now operated under the umbrella of EdPlus) has gone from just under 1,000 students in five programs to nearly 26,000 students in more than 100 fully online programs. Through Realm 2, instructional designers connect faculty expertise to the unique learning needs of online degree seekers. This enables ASU to be responsive to nontraditional learners. It can also facilitate rapid, scalable response to very specific opportunities. For example, through an innovative partnership with Starbucks, ASU is on track to provide degrees to 25,000 Starbucks employees (or partners) by 2025. 16

ASU’s Teaching and Learning Realms 3 and 4 venture further into the frontiers of university innovation. ASU’s Global Freshman Academy (GFA) is the chief effort in Realm 3. In partnership with the MIT/Harvard University nonprofit venture edX, GFA is a massive open online course (MOOC) platform. Existing MOOC platforms offer certifications or badges for completed courses, but GFA is the first to offer course credit from an accredited university. GFA is also priced affordably for learners around the world—less than $200 per credit hour—and students pay for course credit only after passing the course and only if they want the optional university credit. Initial enrollment in the first 10 GFA courses exceeded 350,000 students.

ASU’s Realm 4 is dedicated to education through exploration. Similar to the research and development arm of a large company, Realm 4 at ASU aims to understand, integrate, and shape the newest technology-driven approaches to learning. Efforts here involve the development of platforms for game-based learning, adaptive learn- ing, and personalized learning. For example, one Realm 4 project, driven in part by ASU’s Center for Education Through eXploration (ETX), is the “immersive virtual field trip” or iVFT. This project uses digital photo, video, satellite, and map technologies to capture the experiences of eld scientists and share them with learners through interactive tools. It is but one of many potential ways that the uni- versity can expand the number and kinds of students it reaches, and the means by which they can learn.

Higher education in the United States has entered a new era shaped by profound social and economic challenges and historically unique technological acceleration. To confront these challenges, tradition, replication, and standardization are not enough. Design thinking offers an important pathway for transforming universities into adaptive institutions that can carry out the important work of effectively responding to legacy and emerging markets. Although design thinking and strategic thinking are often tightly coupled, no amount of strategy can remedy an organization whose design is incapable of responding to the full spectrum of problems it faces.

University leaders who would risk dual transformation are required to exercise full commitment to multiple, potentially conflicting visions of the future. They undoubtedly confront skepticism, resistance, and inertia, which may sway them from pursuing overdue reforms. We recognize that this marks a tumultuous time in the history of American higher education, but we see it as an opportunity. America’s leaders in higher education must rise to the challenge of creating new, innovative design models for their universities—for the betterment of their institutions, higher education, and society as a whole.

Support SSIR ’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges. Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today .

Read more stories by Clark G. Gilbert , Michael M. Crow & Derrick Anderson .

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

documentary

What is Design Thinking in Education?

In a world where artificial intelligence, exemplified by tools like ChatGPT, is reshaping our world, the human touch of design thinking becomes even more crucial. You might already be familiar with design thinking and curious about how to harness it alongside AI, or perhaps you’re new to this method. Regardless of your experience level, I’m going to share why design thinking is your human advantage in an AI-world. We’ll explore its impact on students and educators, particularly when integrated into the curriculum to design learning experiences that are both innovative and empathetic.

Back in 2017, I spearheaded a two-year research study at Design39 Campus in San Diego, CA, focusing on how educators used design thinking to transcend traditional educational practices. This study was pivotal in understanding how to scale from pockets of innovation to a culture of innovation. It’s rare to see a public school integrate these practices, and I always wondered, “Why is this the exception and not the norm?” How might design thinking when combined with AI tools, complement standards-based curricula by prompting students to tackle real-world challenges. We investigated the methods educators used to learn about design thinking and how they crafted learning experiences at the nexus of knowledge, skills, and mindsets, aiming to foster creative problem-solving in an increasingly AI-integrated world. The results revealed it had nothing to do with the technology. It had to do with people.

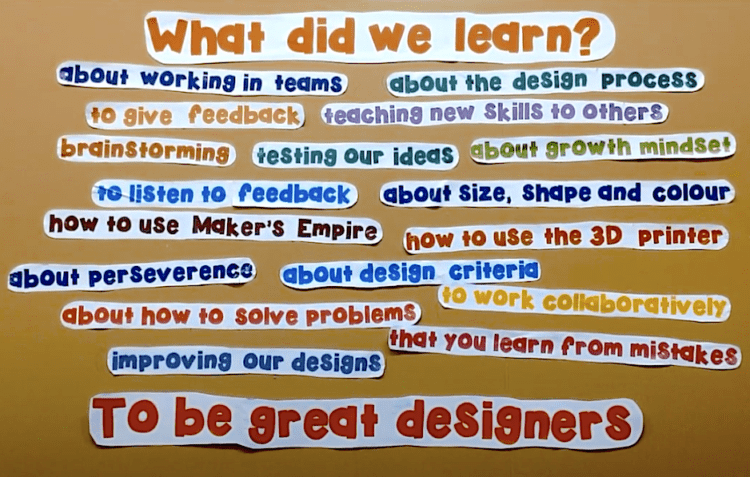

Design thinking is both a method and a mindset.

What makes design thinking unique in comparison to other frameworks such as project based learning, is that in addition to skills there is an emphasis on developing mindsets such as empathy, creative confidence, learning from failure and optimism.

Seeing their students and themselves enhance and develop their skills and mindset of a design thinker demonstrated the value in using design thinking and fueled their motivation to continue. In addition, it strengthened their self-efficacy and helped them embrace, not fear change.

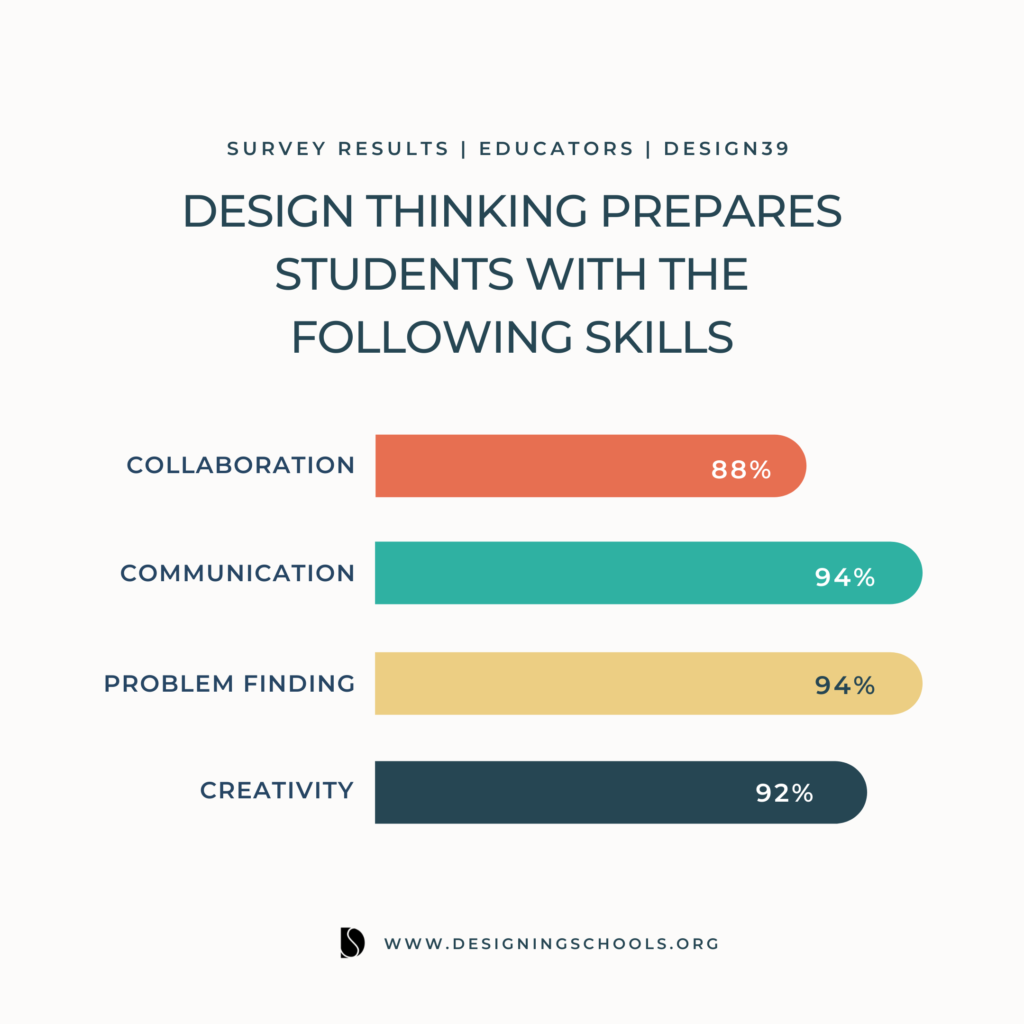

The results indicate strong agreement amongst the educators between developing in demand skills such as creativity, problem finding, collaboration and communication and practicing design thinking.

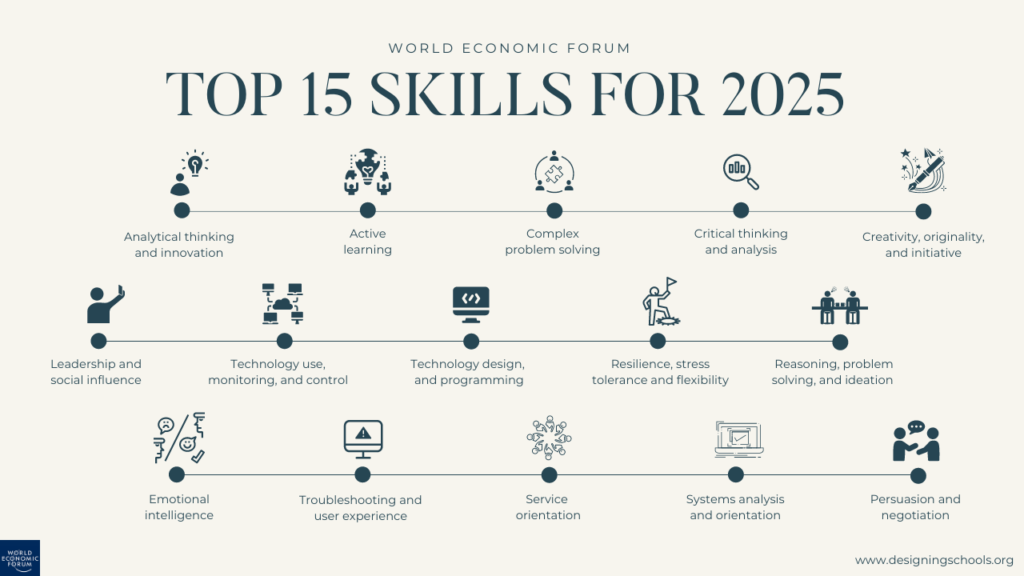

As workplaces determine how to leverage new and emerging technologies in ways that serve humanity, the two critical skills expected will be the ability to solve unstructured problems and to engage in complex communication, two areas that allow workers to augment what machines can do (Levy & Murnane, 2013.)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) call this era, “The Second Machine Age,” characterized by advances in technology, such as the rise of big data, mobility, artificial intelligence, robotics and the internet of things. The World Economic Forum calls this era, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution.”

Regardless of the name we give this era, Schwab warned, as did Brynjolfsson and McAfee, that failure by organizations to prepare and adapt could cause inequality and fragment societies.

That era that we once talked about, is not here.

The rise of generative Ai.

As Erik Brynjolfsson shares, “There is no economic law that says as technology advances, so does equal opportunity.” The World Economic Forum reinforces this by sharing, that while the dynamics of today’s world have the potential to create enormous prosperity, the challenge to societies, particularly businesses, governments and education systems, will be to create access to opportunities that will allow everyone to share in the prosperity.

Schwab, Brynjolfsson and McAfee advocate for schools being able to play a powerful role in shaping a future that is technology-driven and human-centered. Design thinking, a human-centered framework is one method that can provide educators with the skills and mindset to navigate away from the traditional model established during the industrial area. To a learner-centered vision where we design learning experiences at the intersection of knowledge, skills, and mindsets.

The Future of Work

Designing schools for today’s learner is not just about solving a workforce or technology challenge. It’s also about solving a human challenge, where every individual has the access and opportunity to reach their potential.

Despite the changing expectations of the workplace brought forth by this era, today’s education systems largely remain unchanged. Leaving graduates without the knowledge, skills and mindsets to thrive in future workplaces and as citizens. Furthermore, the lack of equity has led to what Paul Attewell calls a growing digital use divide deepening the fragmentation of society.

A decade ago, some of the most in-demand occupations or specialties today did not exist across many industries and countries. Furthermore, 60% of children in kindergarten will live in a world where the possible opportunities do not yet exist (World Economic Forum, 2017).

In Technology, Jobs and the Future of Work, McKinsey states that 60% of all occupations have at least 30% of activities that can be automated. 40% of employers say lack of skills is the main reason for entry level job vacancies. And 60% of new graduates said they were not prepared for the world of work in a knowledge economy, noting gaps in technical and soft skills. Before our experience with ChatGPT I’m reminded of Imaginable by Jane McGonigal where she shares, “Almost everything important that’s ever happened, was unimaginable shortly before it happened.”

With an influx of technology over the past decade, with iPads and Chromebooks, and now the acceleration of AI technology, particularly over the past year, we have to wonder what gaps exist that prevent us from accelerating and scaling the change we want to see in schools.

One reason is that this challenge is complex and overwhelming. This is where design thinking practices are helpful in moving from idea to impact. Design thinking practices provide the structure and scaffolds needed to take a complex idea and simplify it.

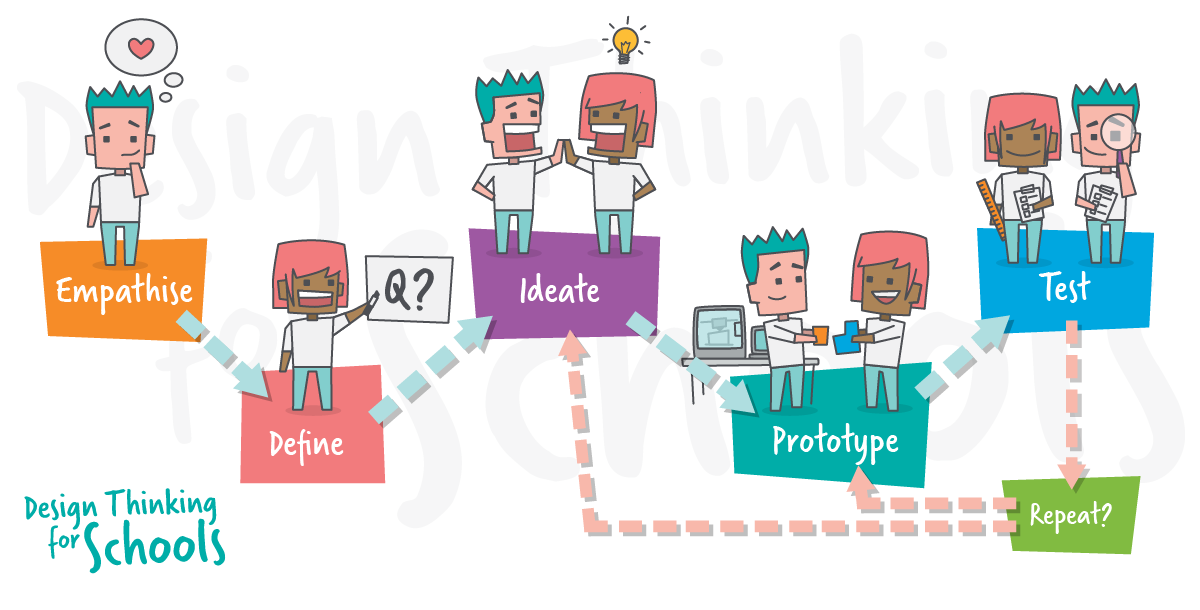

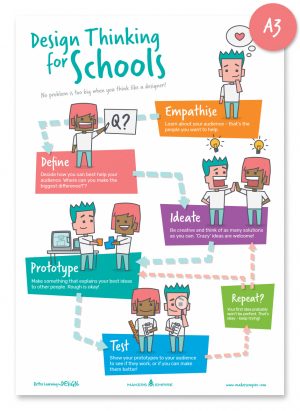

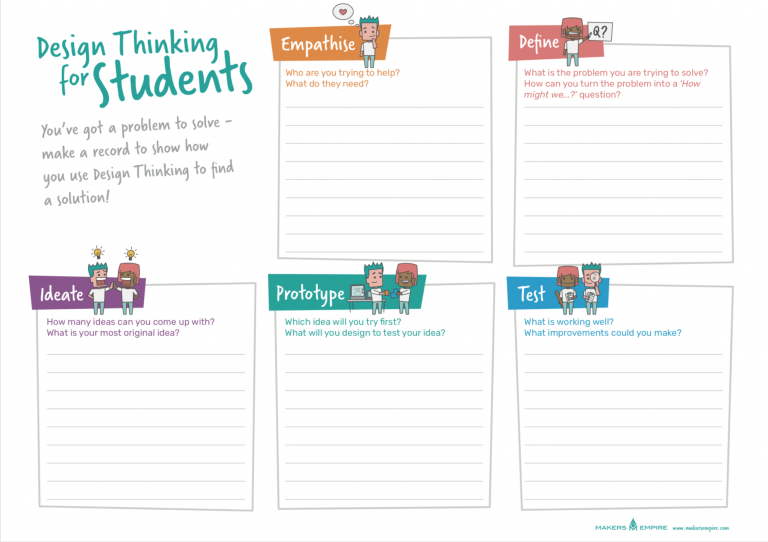

The Design Thinking Process

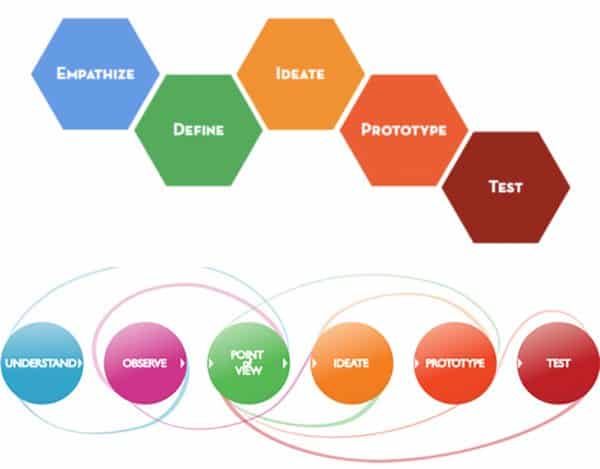

Too often design thinking is seen as a series of hexagons to jump through. Check off one and move onto the next. Design thinking is a non-linear framework that nurtures your mindset toward navigating change.

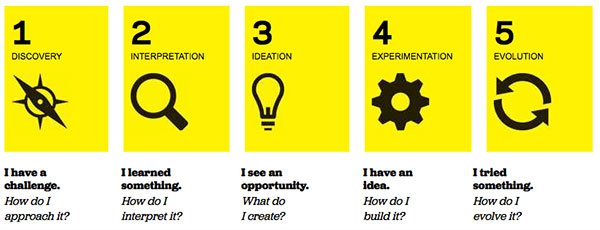

It can be used in three areas:

- Problem finding

- Problem solving

- Opportunity exploration

The design thinking model is nonlinear. Resulting in a back and forth between the stages of inspiration, ideation and implementation, in an effort to continuously improve upon their potential solution (Shively et al., 2018). These stages were expanded by the d.School into empathy, define, ideate, prototype and iterate. In fact, there are many exercises that can be used to apply each area of the process.

Let’s walk through each phase. Then I’ll share examples of how it is being used. I also want to preface this by saying that simply going through these stages is where most people misunderstand design thinking and don’t see the results they hoped for. These phases are here to help you develop an action-oriented mindset. Moving from identifying a problem to designing and then testing a solution to quickly get feedback. Each of these phases have numerous exercises to also help facilitate experiences based on your scenario.

Phase 1: Empathy

When you begin with empathy, what you think is challenged by what you learn. This alone is what makes design thinking so unique and is the first phase. During the empathy stage, you observe, engage and immerse yourself in the experience of those you are designing for. Continuously asking, “why” to understand why things are the way they are.

This phase is where we see the most challenges, yet this phase is the most critical. An empathy map is probably the most common exercise. Yet there are others such as, “Heard, Seen, Respected.” Another challenge in this area is not speaking directly to the user. For example, I’ve sat in many “design thinking” experiences where the group will speculate on behalf of the users. For example, educators speculating about parents, administrators speculating about teachers.

The purpose behind an empathy exercise is that when we begin with empathy, what we think is challenged by what we learn. While you can practice with each other, ultimately you must speak directly to who you are designing for.

Phase 2: Define

During the define stage you unpack the empathy findings and create an actionable problem statement often starting with, “how might we…” This statement not only emphasizes an optimistic outlook, it invites the designer to think about how this can be a collaborative approach.

Phase 3: Ideate

During the ideate phase you generate a series of possibilities for design. The focus here is quantity not quality. As you want to generate as many possibilities to see how they may merge together. As Guy Kawasaki shares, “Don’t worry be crappy.” Feasibility is not important at this step. Rather the key is to not think about what is possible but what can be possible. At the end, one of the ideas, or the merging of many ideas, is chosen to expand upon in the next phase.

This is another phase where we see challenges. It is not enough to simply tell someone to get a piece of paper and then come up with lots of ideas. As adults, this is incredibly challenging and is also a muscle that needs to be developed. In fact, one of my favorite exercises is 1-2-4-all. Another is walking questions, where the prompt begins with “What if…” and then after each person writes something it is handed to the person on their right.

Phase 4: Prototype

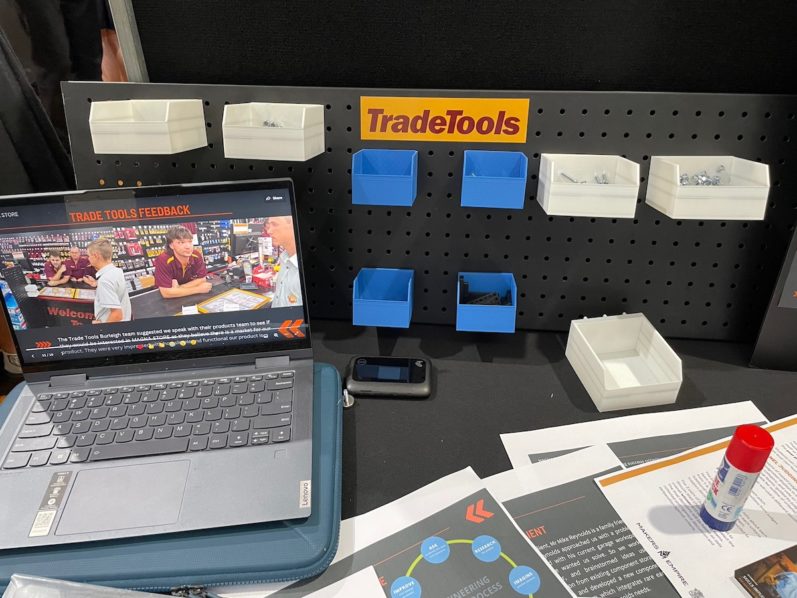

During the prototype phase, ideas that were narrowed down from ideation are created in a tangible form so that they can be tested. During this phase, the designer has an opportunity to test their prototype and gain feedback.

Phase 5: Iteration

By quickly testing the prototype, the user can refine the idea. And have a deeper understanding to go back and ask questions to the group they are designing for. The feedback received from the user allows the designer to engage in a deeper level of empathy to refine the questions asked and the problem being defined. This brings us back to phase 1.

You can find more of these exercises to lead your group through each phase at sessionlab.com .

As schools strive to create student learning experiences that prepare them for their future, design thinking can play a critical role in complementing students’ knowledge with the skills and mindsets to be creative problem solvers.

Examples of Design Thinking in K12

While new approaches tend to be viewed with skepticism, an increasing number of studies are coming forward reflecting the promise of transferability of skills and mindsets from the classroom to real-world problems when utilizing design thinking. As expectations are raised about what student skills and mindsets are needed, the level of support for educators must increase as well to experience success in new strategies and the outcomes they promise.

When student learning experiences include design thinking, their skills continue to be enhanced and developed. This in turn allows them to apply these strategies to be problem finders and problem solvers. Helping them be more comfortable with change and empowering them to solve unstructured problems. And work with new information, gaining knowledge, skills and mindsets that cannot be found in the confines of a textbook.

In “The Second Machine Age,” the authors share:

Technological progress is going to leave behind some people, perhaps even a lot of people, as it races ahead. As we’ll demonstrate, there’s never been a better time to be a worker with special skills or the right education. Because these people can use technology to create and capture value. However, there’s never been a worse time to be a worker with only “ordinary” skills and abilities to offer, because computers, robots, and other digital technologies are acquiring these skills and abilities at an extraordinary rate. The Second Machine Age | Erik Brynjolfsson | Andrew McAffee

Design thinking strengthens the mindsets and skills that today’s world demands with the ability to become creative problem solvers. Through nurturing the skills and mindsets developed through engaging in design thinking, schools can create more equitable use environments for all learners that leverage technology to accelerate creative tasks that can bridge the digital use divide.

Case Study 1: Design Thinking in Grade 6

A recent study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education highlights that through instruction, students transfer design thinking strategies beyond the classroom. And that the biggest benefits were to low-achieving students (Chin et al., 2019).

The study included 200 students from grade 6. The researchers worked with the educators during class time to coach half the group of students on two specific design thinking strategies. And then assigned them a project where they could apply these skills.

The two strategies included seeking out constructive feedback and identifying multiple possible outcomes to a challenge. Each of these strategies were designed to prevent what the researchers called, “early closure”. Identifying the potential solution before examining the problem.

After class the students were presented with different challenges to see how they would approach them. The students who were taught about constructive criticism asked for feedback when presented with the new challenge and were more likely to go back and revise their work.

This area was significant, as a pre-test revealed that low-achieving students were behind their high achieving peers when seeking out feedback, a gap that the researchers say disappeared after classroom instruction, highlighting the need for this to be taught to all students, not just advanced students in electives.

As Attewell shares, “Placing computers in the hands of every student is not a solution because the challenge lies in addressing the “ digital use divide – changing the tasks that students do when provided with computers.”

He further highlights the students who gain the types of skills highlighted by the Future of Jobs Report are white and affluent students. These students are more likely to use technology to develop trending skills with greater levels of adult support. Whereas minority students are more likely to use it for rote learning tasks, with lower levels of adult support.

While design thinking is often found in pockets, presented to students already interested in this area, or the students who are in certain electives, the study led by the Stanford Graduate School of Education demonstrates the advances that can be made when this is offered to all students.

Case Study 2: Design Thinking in Geography

Another study (Caroll et al., 2010) focused on the implementation of a design curriculum during a middle school geography class. And explored how students expressed their understanding of design thinking in classroom activities, how affective elements impacted design thinking in the classroom environment and how design thinking is connected to academic standards and content in the classroom. The students were a diverse group with 60% Latino, 30% African-American, 9% Pacific Islander and 1% White.

The task was for students to use the design process to learn about systems in geography. The study found that students increased their levels of creative confidence. And that design thinking fostered the ability to imagine without boundaries and constraints. A key element to success was that educators needed to see the value of design thinking. And it must be integrated into academic content.

A challenge often associated with design thinking in education is not integrating it into mainstream education as an equitable experience for all learners despite showing that lower achieving students benefit more (Chin et al, 2019).

If students are to experience dynamic learning experiences, then organizations must raise the level of support for educators and give them the time and space to learn and integrate design thinking.

How Educators Use Design Thinking

Educators are facing a number of challenges in their professional practice. Many of the requirements today are tools and methods they did not grow up with. Furthermore, the profession is tasked with designing new methods often within traditional systems that have constraints that may serve as roadblocks to change (Robinson & Aronica, 2016).

A 2018 study by PwC with the Business Higher Education Forum shared that an average of 10% of K-12 teachers feel confident incorporating higher-level technology that affords students the opportunity to use technology to design learning that is active, not passive.

As a result, students do not spend much time in school actively practicing the higher-level trending skills expected by employers. Moreover, the report shows that more than 60% of classroom technology use is passive, while only 32% is active use. While the study suggests that many teachers do not have the skills to engage students in the active use of technology, 79% said they would like to have more professional development for how to leverage technology to design learning that is active.

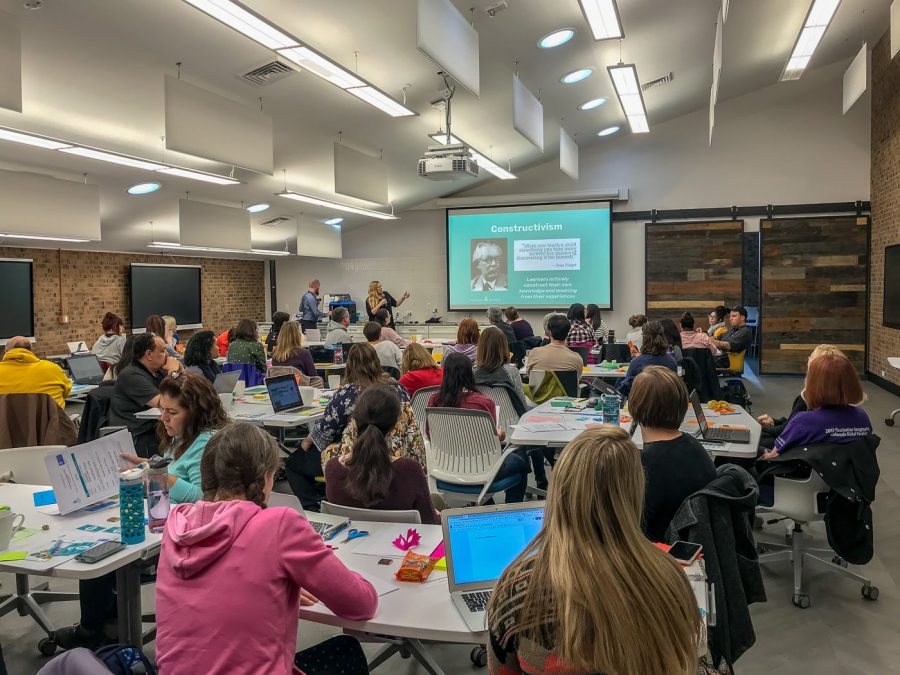

Case Study 3: Design39 Campus

As I shared earlier I led a two-year research study at Design39 Campus. The study examines how it helped teachers evolve their practice. At Design39 teachers are called “Learning Experience Designers” (LEDs). Borko and Putnam (1995) share that how educators think is related to their knowledge. To understand how LEDs are using design thinking to complement the standards-based curriculum, it was important to understand how they acquired and applied this knowledge.

Despite design thinking having its roots outside of education, when asked, “What does design thinking mean to you?” The LEDs identified many commonalities amongst their own work as educators and design thinking. Moreover, they appreciated the alignment of their work with the vocabulary and structure of the design thinking framework.

Over 50% of the LEDs interviewed identified design thinking as providing them with a common vocabulary and structure for what they already do. The LEDs identified educators as inherent design thinkers due to the shared human-centered focus of working with users. In this experience educators design challenges with cyclical learning tasks involving testing, feedback and iteration, and a design mindset to address the wide variety of complex problems within their individual classrooms and across education organizations.

One LED shared:

I just look at it as a process, a process in my mind that we kind of naturally go through as educators, and so with the design thinking process I feel that it is codifying what we do and so we start off always in empathy and empathy is the heart of design thinking and so we are problem solving, who are we problem solving for – people, our learners and so this entire process that we go through of brain dumping it, trying it, getting feedback and coming back to it again so that we can make sure we were really insightful about what the problem really was for the users and we continue around this process to fine tune a potential solution is the design thinking process. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

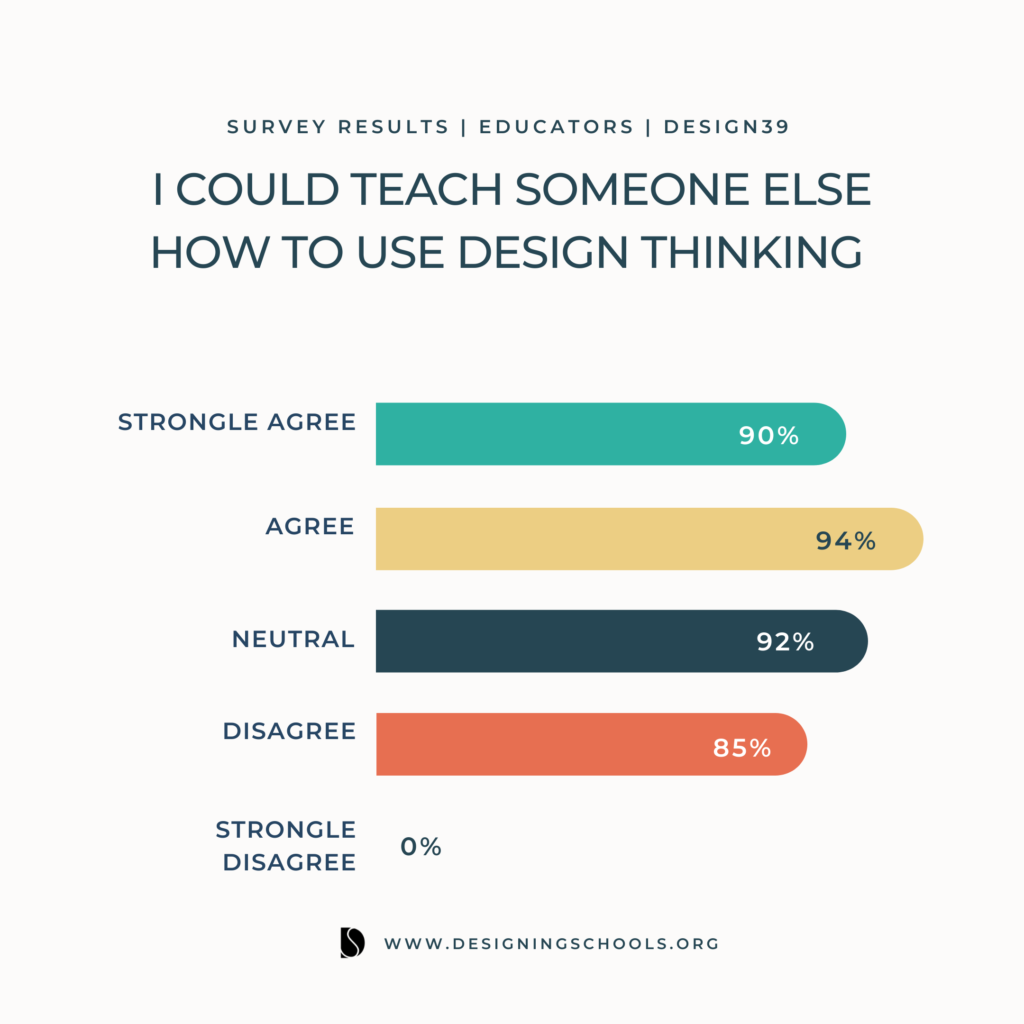

One of the ways mastery of knowledge is demonstrated is by teaching others. To assess their mastery of design thinking in education, learning experience designers were asked to describe their confidence in teaching someone else how to integrate design thinking into their curriculum.

Many LEDs acknowledged that although this is what it often looked like in the first year of the school opening, they have since had the time, space and collaborative opportunities to explore and create deeper integration. This was a point of reference mentioned by 78% of LEDs.

I think a lot of people see design thinking as one science activity, we design think everything from rules to problems that come up in the playground, it’s all through the day, they (the learners) are always looking for problems to solve. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

In another example, four LEDs made a note using the exact same language that “design thinking is not always cardboard and duct tape.” What allows them to design learning that is more meaningful one LED highlighted:

Not every day is about using duct tape and cardboard, sometimes to do the design to solve the problems you have to hunker down and read and research and so some days, design thinking is highlighting and taking notes. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

Another LED elaborated on this idea by sharing that

Design thinking is a way of thinking, not always a product that is created at the end. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

LEDs in all focus groups shared how ultimately design thinking was an opportunity to design lessons that are “ bigger than we are .”

This allowed for the LEDs to design learning experiences. With this, the end result was not to just design a potential solution to a challenge that was identified. Or to simply go from one standard to another, checking off boxes along the way, but that the solution, the work the learners were doing lived beyond the classroom for an authentic audience, where learners are working on real world problems and presenting their solutions to a real world audience.

Almost all of the LEDs shared that to them design thinking was a mindset. It is a process of inquiry that allowed for a more human centered environment where the learner was the focus.

This highlighted a critical shift in the culture at Design39, an element Sarason (2004) discussed in saying no one ever asks:

“Why is school not a place where educators learn as well?”

Bring a Design Thinking Workshop to Your School

We’ve invested in technology. Now it’s time to invest in people. Let’s discuss how design thinking practices can enhance the work you are doing in your school, giving everyone the mindset and skills to navigate change with enthusiasm and optimism. Use this calendar to schedule a time with Sabba to discuss bringing a workshop to your school. Workshops can be delivered both virtually and in-person.

Attewell, P. (2001). The first and second digital divides. Sociology of Education, 74(3), 252-259

Borko, H., & Putnam, R.T. (1995). Expanding a teacher’s knowledge base: A cognitive psychological perspective on professional development. In T. Gusky & M. Huberman (Eds), Professional development in education: New paradigms and practices (pp.35-65). Teachers College Press.

Brown, T & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Science Review, 8 (1), 30-35.

Brynjolfsson, E. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies (1st t ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Carroll, M., Goldman, S., Britos, L., Koh, J., Royalty, A., & Hornstein, M. (2010). Destination, imagination and the fires within: Design thinking in a middle school classroom. International Journal of Art and Design Education, (29)1, 37-53.

Chin, D. B., Doris, Blair, K.P., Wolf, R., & Conlin, L., Cutumisu, M., Pfaffman, J., Schwartz, D.L. (2019). Educating and measuring choice: A test of the transfer of design thinking in problem solving and learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences. 1-44.

Levy, F., & Murnane, R. (2013). Dancing with Robots. NEXT Report.

McKinsey Global Institute (2017). Technology, Jobs and the Future of Work. McKinsey.

PwC (2017). Technology in U.S. Schools: Are we preparing our students for the jobs of tomorrow . Pricewater House Coopers. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/about-us/corporate-responsibility/library/preparing-students-for-technology-jobs.html .

Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2016). Creative schools: the grassroots revolution that’s transforming education. Penguin Books.

Shively, K., Stith, K.M., & Rubenstein, L.D. (2018). Measuring what matters: Assessing creativity, critical thinking, and the design process. Gifted Child Today, 41(3) 149-158.

World Economic Forum. (2018). The future of jobs: Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution . World Economic Forum.

I believe that the future should be designed. Not left to chance. Over the past decade, using design thinking practices I've helped schools and businesses create a culture of innovation where everyone is empowered to move from idea to impact, to address complex challenges and discover opportunities.

stay connected

designing schools

[…] importance of learning experiences at the intersection of developing learning skills and mindsets. Design thinking is one approach that can help you master both. In my experience it’s rare that design thinking […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

« How Education Leaders Use Social Media to Build Trust, Encourage Creativity, and Inspire a Collective Vision

Creative Career Map: How Students Can Navigate the Future of Work with Design Thinking »

Browse By Category

Social Influence

Design Thinking

Join the Community

All of my best and life changing relationships began online. Whether it's a simple tweet, a DM or an email. It always begins and ends with the relationships we create. Each week I'll send the skills and strategies you need to build your human advantage in an AI world straight to your inbox.

As Simon Sinek Says: "Alone is hard. Together is better."

©DesigningSchools. All rights reserved. 2023

Instagram is my creative outlet. It's where you can see stories that take you behind the scenes and where I love having audio chats in my DM.

@designing_schools

- Utility Menu

Design Thinking in Education

Design Thinking is a mindset and approach to learning, collaboration, and problem solving. In practice, the design process is a structured framework for identifying challenges, gathering information, generating potential solutions, refining ideas, and testing solutions. Design Thinking can be flexibly implemented; serving equally well as a framework for a course design or a roadmap for an activity or group project.

Download the HGSE Design Thinking in Education infographic to learn more about what Design Thinking is and why it is powerful in the classroom.

Design Consultation for projects, session, and courses, including active learning and facilitation strategies.

Brainstorming Kits including Post-it notes, Sharpie markers, and stickable chart paper.

Physical Prototyping Cart with dozens of creative, constructivist supplies, including felt, yarn, foil, craft sticks, rubber bands, Play-Doh, Legos, and more.

For more information about TLL resources or to check-out brainstorming or prototyping materials, contact Brandon Pousley .

Other Resources There are dozens of ready-made activities, workbooks, and curricular guides available online. We suggest starting with the following:

Stanford — d.school and the The Bootcamp Bootleg IDEO — ' Design Thinking for Educators ' and the Design ThinkingToolkit Business Innovation Factory — 'Teachers Design for Education' and the TD4Ed Curriculum Research — Design Thinking in Pedagogy — Luka, Ineta (2014). Design Thinking in Pedagogy. Journal of Education Culture and Society, No. 2, 63-74.

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Design Thinking in Education: Perspectives, Opportunities and Challenges

The article discusses design thinking as a process and mindset for collaboratively finding solutions for wicked problems in a variety of educational settings. Through a systematic literature review the article organizes case studies, reports, theoretical reflections, and other scholarly work to enhance our understanding of the purposes, contexts, benefits, limitations, affordances, constraints, effects and outcomes of design thinking in education. Specifically, the review pursues four questions: (1) What are the characteristics of design thinking that make it particularly fruitful for education? (2) How is design thinking applied in different educational settings? (3) What tools, techniques and methods are characteristic for design thinking? (4) What are the limitations or negative effects of design thinking? The goal of the article is to describe the current knowledge base to gain an improved understanding of the role of design thinking in education, to enhance research communication and discussion of best practice approaches and to chart immediate avenues for research and practice.

Aflatoony, L., Wakkary, R., & Neustaedter, C. (2018). Becoming a Design Thinker: Assessing the Learning Process of Students in a Secondary Level Design Thinking Course. International Journal of Art & Design Education , 37 (3), 438–453. 10.1111/jade.12139 Search in Google Scholar

Altringer, B., & Habbal, F. (2015). Embedding Design Thinking in a Multidisciplinary Engineering Curriculum. In VentureWell. Proceedings of Open, the Annual Conference (p. 1). National Collegiate Inventors & Innovators Alliance. Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, N. (2012). Design Thinking: Employing an Effective Multidisciplinary Pedagogical Framework to Foster Creativity and Innovation in Rural and Remote Education. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education , 22 (2), 43–52. Search in Google Scholar

Apel, A., Hull, P., Owczarek, S., & Singer, W. (2018). Transforming the Enrollment Experience Using Design Thinking. College and University , 93 (1), 45–50. Search in Google Scholar

Badwan, B., Bothara, R., Latijnhouwers, M., Smithies, A., & Sandars, J. (2018). The importance of design thinking in medical education. Medical Teacher , 40 (4), 425–426. 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1399203 Search in Google Scholar

Beligatamulla, G., Rieger, J., Franz, J., & Strickfaden, M. (2019). Making Pedagogic Sense of Design Thinking in the Higher Education Context. Open Education Studies , 1 (1), 91–105. 10.1515/edu-2019-0006 Search in Google Scholar

Bosman, L. (2019). From Doing to Thinking: Developing the Entrepreneurial Mindset through Scaffold Assignments and Self-Regulated Learning Reflection. Open Education Studies , 1 (1), 106–121. 10.1515/edu-2019-0007 Search in Google Scholar

Bowler, L. (2014). Creativity through “Maker” Experiences and Design Thinking in the Education of Librarians. Knowledge Quest , 42 (5), 58–61. Search in Google Scholar

Bross, J., Acar, A. E., Schilf, P., & Meinel, C. (2009, August). Spurring Design Thinking through educational weblogging. In Computational Science and Engineering, 2009. CSE’09. International Conference on (Vol. 4, pp. 903–908). IEEE. 10.1109/CSE.2009.207 Search in Google Scholar

Brown, T. (2009). Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation . New York: HarperCollins Publishers. Search in Google Scholar

Brown, T., & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Development Outreach , 12 (1), 29–43. 10.1596/1020-797X_12_1_29 Search in Google Scholar

Brown, A. (2018). Exploring Faces and Places of Makerspaces. AACE Review. Retrieved from March 3, 2019 https://www.aace.org/review/exploring-faces-places-makerspaces/ Search in Google Scholar

Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked problems in design thinking. Design Issues , 8 (2), 5–21. 10.2307/1511637 Search in Google Scholar

Callahan, K. C. (2019). Design Thinking in Curricula. In The International Encyclopedia of Art and Design Education (pp. 1–6). American Cancer Society. 10.1002/9781118978061.ead069 Search in Google Scholar

Camacho, M. (2018). An integrative model of design thinking. In The 21st DMI: Academic Design Management Conference, ‘Next Wave’, London, Ravensbourne, United Kingdom, 1 – 2 August 2018 (p. 627). Search in Google Scholar

Cañas, A. J., Novak, J. D., & González, F. (2004). Using concept maps in qualitative research. In Concept Maps: Theory, Methodology, Technology Proc. of the First Int. Conference on Concept Mapping (pp. 7–15). Search in Google Scholar

Cantoni, L., Marchiori, E., Faré, M., Botturi, L., & Bolchini, D. (2009, October). A systematic methodology to use lego bricks in web communication design. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM international conference on Design of communication (pp. 187–192). ACM. 10.1145/1621995.1622032 Search in Google Scholar

Carroll, M. P. (2014). Shoot for the Moon! the Mentors and the Middle Schoolers Explore the Intersection of Design Thinking and STEM. Journal of Pre-College Engineering Education Research , 4 (1), 14–30. 10.7771/2157-9288.1072 Search in Google Scholar

Carroll, M., Goldman, S., Britos, L., Koh, J., Royalty, A., & Hornstein, M. (2010). Destination, Imagination and the Fires within: Design Thinking in a Middle School Classroom. International Journal of Art & Design Education , 29 (1), 37–53. 10.1111/j.1476-8070.2010.01632.x Search in Google Scholar

Cassim, F. (2013). Hands on, hearts on, minds on: Design thinking within an education context. International Journal of Art & Design Education , 32 (2), 190–202. 10.1111/j.1476-8070.2013.01752.x Search in Google Scholar

Carlgren, L., Rauth, I., & Elmquist, M. (2016). Framing design thinking: The concept in idea and enactment. Creativity and Innovation Management , 25 (1), 38–57. 10.1111/caim.12153 Search in Google Scholar

Cochrane, T., & Munn, J. (2016). EDR and Design Thinking: Enabling Creative Pedagogies. In Proceedings of EdMedia 2016--World Conference on Educational Media and Technology (pp. 315–324). Vancouver, BC, Canada: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Retrieved April 3, 2018 from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/172969/ . Search in Google Scholar

Coleman, M. C. (2016). Design Thinking and the School Library. Knowledge Quest , 44 (5), 62–68. Search in Google Scholar

Cook, K. L., & Bush, S. B. (2018). Design Thinking in Integrated STEAM Learning: Surveying the Landscape and Exploring Exemplars in Elementary Grades. School Science and Mathematics , 118 , 93–103. 10.1111/ssm.12268 Search in Google Scholar

Crossan, M. M., & Apaydin, M. (2010). A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Management Studies, 47 (6), 1154–1191. 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00880.x Search in Google Scholar

Dorst, K. (2011). The core of ‘design thinking’ and its application. Design Studies , 32 (6), 521–532. 10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006 Search in Google Scholar

Douglass, H. (2016). Engineering Encounters: No, David! but Yes, Design! Kindergarten Students Are Introduced to a Design Way of Thinking. Science and Children , 53 (9), 69–75. 10.2505/4/sc16_053_09_69 Search in Google Scholar

Dunne, D., & Martin, R. (2006). Design Thinking and How It Will Change Management Education: An Interview and Discussion. Academy of Management Learning & Education , 5 (4), 512–523. 10.5465/amle.2006.23473212 Search in Google Scholar

Elsbach, K. D., & Stigliani, I. (2018). Design Thinking and Organizational Culture: A Review and Framework for Future Research. Journal of Management , 0149206317744252. 10.1177/0149206317744252 Search in Google Scholar

Eppler, M. J., & Kernbach, S. (2016). Dynagrams: Enhancing design thinking through dynamic diagrams. Design Studies , 47 , 91–117. 10.1016/j.destud.2016.09.001 Search in Google Scholar

Ferguson, R., Barzilai, S., Ben-Zvi, D., Chinn, C. A., Herodotou, C., Hod, Y., Kali, Y., Kukulska-Hulme, A., Kupermintz, H., McAndrew, P., Rienties, B., Sagy, O., Scanlon, E., Sharples, M., Weller, M., & Whitelock, D. (2017). Innovating Pedagogy 2017: Open University Innovation Report 6. Milton Keynes: The Open University, UK. Retrieved April 3, 2018 from https://iet.open.ac.uk/file/innovating-pedagogy-2017.pdf Search in Google Scholar

Ferguson, R., Coughlan, T., Egelandsdal, K., Gaved, M., Herodotou, C., Hillaire, G., ... & Misiejuk, K. (2019). Innovating Pedagogy 2019: Open University Innovation Report 7. Retrieved March 3, 2019 from https://iet.open.ac.uk/file/innovating-pedagogy-2019.pdf Search in Google Scholar

Fabri, M., Andrews, P. C., & Pukki, H. K. (2016). Using design thinking to engage autistic students in participatory design of an online toolkit to help with transition into higher education. Journal of Assistive Technologies , 10 (2), 102–114. 10.1108/JAT-02-2016-0008 Search in Google Scholar

Fouché, J., & Crowley, J. (2017). Kidding around with Design Thinking. Educational Leadership , 75 (2), 65–69. Search in Google Scholar

Fontaine, L. (2014). Learning Design Thinking by Designing Learning Experiences: A Case Study in the Development of Strategic Thinking Skills through the Design of Interactive Museum Exhibitions. Visible Language , 48 (2). Search in Google Scholar

Gallagher, A., & Thordarson, K. (2018). Design Thinking for School Leaders: Five Roles and Mindsets That Ignite Positive Change . ASCD. Search in Google Scholar

Gestwicki, P., & McNely, B. (2012). A case study of a five-step design thinking process in educational museum game design. Proceedings of Meaningful Play . Search in Google Scholar

Glen, R., Suciu, C., Baughn, C. C., & Anson, R. (2015). Teaching design thinking in business schools. The International Journal of Management Education , 13 (2), 182–192. 10.1016/j.ijme.2015.05.001 Search in Google Scholar

Goldman, S., Kabayadondo, Z., Royalty, A., Carroll, M. P., & Roth, B. (2014). Student teams in search of design thinking. In Design Thinking Research (pp. 11–34). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-01303-9_2 Search in Google Scholar

Goldschmidt, G. (2017). Design Thinking: A Method or a Gateway into Design Cognition?. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation , 3 (2), 107–112. 10.1016/j.sheji.2017.10.009 Search in Google Scholar

Gottlieb, M., Wagner, E., Wagner, A., & Chan, T. (2017). Applying design thinking principles to curricular development in medical education. AEM Education and Training , 1 (1), 21–26. 10.1002/aet2.10003 Search in Google Scholar

Gross, K., & Gross, S. (2016). Transformation: Constructivism, design thinking, and elementary STEAM. Art Education , 69 (6), 36–43. 10.1080/00043125.2016.1224869 Search in Google Scholar

Grots, A., & Creuznacher, I. (2016). Design Thinking: Process or Culture? In Design Thinking for Innovation (pp. 183–191). Springer. Search in Google Scholar

Groth, C. (2017). Making sense through hands: Design and craft practice analysed as embodied cognition . Thesis. Search in Google Scholar

Harth, T., & Panke, S. (2018). Design Thinking in Teacher Education: Preparing Engineering Students for Teaching at Vocational Schools. In E-Learn: World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education (pp. 392–407). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Search in Google Scholar

Harth, T. & Panke, S. (2019). Creating Effective Physical Learning Spaces in the Digital Age – Results of a Student-Centered Design Thinking Workshop. In S. Carliner (Ed.), Proceedings of E-Learn: World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education (pp. 284-294). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Search in Google Scholar

Hawryszkiewycz, I., Pradhan, S., & Agarwal, R. (2015). Design thinking as a framework for fostering creativity in management and information systems teaching programs. In Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems . AISEL. Search in Google Scholar

Hernández-Ramírez, R. (2018). On Design Thinking, Bullshit, and Innovation. Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts , 10 (3), 2–45. 10.7559/citarj.v10i3.555 Search in Google Scholar

Hodgkinson, G. (2013). Teaching Design Thinking. In J. Herrington, A. Couros & V. Irvine (Eds.), Proceedings of EdMedia 2013--World Conference on Educational Media and Technology (pp. 1520–1524). Victoria, Canada: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Search in Google Scholar

Holzer, A., Gillet, D., & Lanerrouza, M. (2019). Active Interdisciplinary Learning in a Design Thinking Course: Going to Class for a Reason , 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1109/TALE.2018.8615292 10.1109/TALE.2018.8615292 Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, C. D. (2016). “Making Is Thinking”: The Design Practice of Crafting Strategy. In Design Thinking for Innovation (pp. 131–140). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-26100-3_9 Search in Google Scholar

Jensen, C. N., Seager, T. P., & Cook-Davis, A. (2018). LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® In Multidisciplinary Student Teams. International Journal of Management and Applied Research , 5 (4), 264–280. 10.18646/2056.54.18-020 Search in Google Scholar

Johansson-Sköldberg, U., Woodilla, J., & Çetinkaya, M. (2013). Design thinking: Past, present and possible futures. Creativity and Innovation Management , 22 (2), 121–146. 10.1111/caim.12023 Search in Google Scholar

Jordan, S., & Lande, M. (2016). Additive innovation in design thinking and making. International Journal of Engineering Education , 32 (3), 1438–1444. Search in Google Scholar

Kaptelinin, V., & Nardi, B. (2012). Activity theory in HCI: Fundamentals and Reflections. Synthesis Lectures Human-Centered Informatics , 5 (1), 1–105. 10.2200/S00413ED1V01Y201203HCI013 Search in Google Scholar

Keele, S. (2007). Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. In Technical report, Ver. 2.3 EBSE Technical Report. EBSE. sn. Search in Google Scholar

Kimbell, L. (2011). Rethinking design thinking: Part I. Design and Culture , 3 (3), 285–306. 10.2752/175470811X13071166525216 Search in Google Scholar

Koria, M., Graff, D., & Karjalainen, T.-M. (2011). Learning design thinking: International design business management at Aalto University. Review on Design, Innovation and Strategic Management , 2 (1), 1–21. Search in Google Scholar

Kwek, S. H. (2011). Innovation in the Classroom: Design Thinking for 21st Century Learning. (Master’s thesis). Retrieved March 3, 2019 from http://www.stanford.edu/group/redlab/cgibin/publications_resources.php Search in Google Scholar

Larson, L. (2017). Engaging Families in the Galleries Using Design Thinking. Journal of Museum Education , 42 (4), 376–384. 10.1080/10598650.2017.1379294 Search in Google Scholar

Leeder, T. (2019). Learning to mentor in sports coaching: A design thinking approach. Sport, Education and Society , 24 (2), 208–211. 10.1080/13573322.2018.1563403 Search in Google Scholar

Lee, D., Yoon, J., & Kang, S.-J. (2015). The Suggestion of Design Thinking Process and its Feasibility Study for Fostering Group Creativity of Elementary-Secondary School Students in Science Education. Journal of The Korean Association For Science Education , 35 , 443–453. 10.14697/jkase.2015.35.3.0443 Search in Google Scholar

Levy, Y., & Ellis, T. J. (2006). A systems approach to conduct an effective literature review in support of information systems research. Informing Science: International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 9 (1), 181–212. 10.28945/479 Search in Google Scholar

Leifer, L., & Meinel, C. (2016). Manifesto: Design thinking becomes foundational. In Design Thinking Research (pp. 1–4). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-19641-1_1 Search in Google Scholar

Leverenz, C. S. (2014). Design thinking and the wicked problem of teaching writing. Computers and Composition , 33 , 1–12. 10.1016/j.compcom.2014.07.001 Search in Google Scholar

Liedtka, J. (2015). Perspective: Linking design thinking with innovation outcomes through cognitive bias reduction. Journal of Product Innovation Management , 32 (6), 925–938. 10.1111/jpim.12163 Search in Google Scholar

Lindberg, T., Meinel, C., & Wagner, R. (2011). Design thinking: A fruitful concept for it development? In Design Thinking (pp. 3–18). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Search in Google Scholar

Lor, R. (2017). Design Thinking in Education: A Critical Review of Literature. In International academic conference on social sciences and management / Asian conference on education and psychology. conference proceedings (pp. 37–68). Bangkok, Thailand. Search in Google Scholar

Louridas, P. (1999). Design as bricolage: anthropology meets design thinking. Design Studies , 20 (6), 517–535. 10.1016/S0142-694X(98)00044-1 Search in Google Scholar

MacLeod, S., Dodd, J., & Duncan, T. (2015). New museum design cultures: harnessing the potential of design and ‘design thinking’ in museums. Museum Management and Curatorship , 30 (4), 314–341. 10.1080/09647775.2015.1042513 Search in Google Scholar

Martin, R. (2009). The design of business: Why design thinking is the next competitive advantage . Harvard Business Press. Search in Google Scholar

Matthews, J. H., & Wrigley, C. (2017). Design and design thinking in business and management higher education. Journal of Learning Design , 10 (1), 41–54. 10.5204/jld.v9i3.294 Search in Google Scholar