Effective Research Assignments

Identify learning goals., clarify expectations., "scaffold" the assignment., test the assignment., collaborate with librarians..

- Assignment Ideas

- Studies on Student Research

Acknowledgement

These best practices were adapted from the handout "Tips for Designing Library Research Assignments" developed by Sarah McDaniel, of the Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries. Many thanks to her for permission to reuse this resource.

See Assignment Ideas to explore different possible approaches beyond a traditional research paper.

- What abilities would you like students to develop through the assignment?

- How will the learning goals and their importance be communicated in the assignment?

Your students may not have prior experience with academic research and resources. State (in writing) details like:

- the assignment's purpose,

- the purpose of research and sources for the assignment,

- suggested resources for locating relevant sources,

- expected citation practices,

- terminology that may be unclear (e.g. Define terms like "database," "peer reviewed"),

- assignment length and other parameters, and

- grading/evaluation criteria ( Rubrics are one way to communicate assessment criteria to students. See, for example, AAC&U's VALUE rubric for information literacy .)

Also consider discussing how research is produced and disseminated in your discipline, and how you expect your students to participate in academic discourse in the context of your class.

Breaking a complex research assignment down into a sequence of smaller, more manageable parts:

- models how to approach a research question and how to manage time effectively,

- empowers students to focus on and to master key research and critical thinking skills,

- provides opportunities for feedback, and

- deters plagiarism.

Periodic class discussions about the assignment can also help students

- reflect on the research process and its importance

- encourage questions, and

- help students develop a sense that what they are doing is a transferable process that they can use for other assignments.

By testing an assignment, you may identify practical roadblocks (e.g., too few copies of a book for too many students, a source is no longer available online).

Librarians can help with this process (e.g., suggest research strategies or resources, design customized supporting materials like handouts or course research guides).

Subject librarians can explore with you ways to support students in their research.

- Next: Assignment Ideas >>

- Last Updated: Oct 20, 2022 8:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.rowan.edu/research_assignments

- Utility Menu

fa3d988da6f218669ec27d6b6019a0cd

A publication of the harvard college writing program.

Harvard Guide to Using Sources

- The Honor Code

- Sources and Your Assignment

The first step in any research process is to make sure you read your assignment carefully so that you understand what you are being asked to do. In addition to knowing how many sources you're expected to consult and what types of sources are relevant to your assignment, you should make sure you understand the role that sources should play in your paper.

For example, a common assignment at Harvard will ask you to test a theory by looking at that theory in relation to a text or series of texts. In this type of assignment, one source—i.e., the source that lays out the theory—will play a large role, as will the text or texts you're considering in relation to that theory. You may not be expected to consult any other sources. On the other hand, for an assignment that asks you to stake out a position for yourself in an ongoing debate, you may need to consult a number of sources to figure out the major positions in that debate before you can decide where you stand on the issue. For this type of assignment, you may also rely on sources to help you understand the context of the debate, to find the evidence that you will analyze to figure out where you stand on the issue, and to learn the definitions of relevant terms. Yet another assignment might ask you to formulate your own question on a broad topic and then answer that question. In this case, you will likely use sources in several different ways—as background information that will help you arrive at a question, as evidence and expert commentary that will help you answer that question, and as opposing views that you will take into consideration as you formulate your argument.

- Locating Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- A Source's Role in Your Paper

- Choosing Relevant Parts of a Source

- Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting

- The Nuts & Bolts of Integrating

PDFs for This Section

- Using sources

- Integrating Sources

- Online Library and Citation Tools

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Effective research assignments: home, communicate your expectations.

- Assess the quality of the sources your students cite as part of their overall grades, and explain clearly in your rubric how that evaluation will be made.

- Spell out your expectations regarding sources. Instead of asking for scholarly sources, for example, you could ask your students to "cite at least two peer-reviewed journal articles and two primary sources".

- Explain terminology and provide background regarding scholarly publishing. What’s peer-review? What are some differences between scholarly books and journal articles? When should one consult popular news sources? What’s a primary source?

- Clearly communicate which style manual is required.

- Include a policy on plagiarism in the assignment and discuss the purposes of proper attribution. Discuss examples: does paraphrasing another author’s ideas require a citation?

- Provide examples of topics that are appropriate in scope for the assignment at hand, and provide feedback to individual students as they begin to develop and refine their topics.

Design and test your assignment An effective research assignment targets specific skills, for example, the ability to trace a scholarly argument through the literature or the ability to organize consulted resources into a bibliography.

- Test the assignment yourself. Can you find the kinds of sources required? Are you required to evaluate the sources you find?

- Ask students for feedback on the assignment. Are they having problems finding relevant materials? Do they understand your expectations?

- If the assignment is particularly demanding, consider dividing a single research project into multiple assignments (outline, draft, final draft), each one focusing on a different aspect of the research process.

Ideas for alternative research assignments

- Assign an annotated bibliography in which students identify primary and secondary sources, popular and scholarly publications, and detect and comment on forms of bias.

- Ask for students to document the search tools they use (library catalog, article databases, Google, etc.) for a research paper and to reflect on the kinds of information they find in each.

- Provide a resource list or a single source from which students’ research should begin. Discuss the utility of known sources for identifying keywords, key concepts, and other citations to inform further searching.

- Assign students to prepare a guide for introducing their classmates to the essential literature on a given topic.

- Have students compile a glossary of important terms specific to a given topic in your discipline.

- Require students to edit an anthology of important scholarship on a specific topic and write an introduction explaining the development of the field over time.

Avoid these common mistakes

- Since many scholarly sources are available online, it can be confusing for students when “Internet” or “Web” sources are forbidden. It’s helpful to describe why certain sources (such as Wikipedia) may not be allowed.

- Make sure the resources required by the assignment are available to your students in the library or in library databases. You can also place hard-to-find required sources on course reserve .

- Last Updated: May 4, 2022 10:41 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/effective-research-assignments

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Common Assignments: Journal Entries

Basics of journal entries, related webinar.

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Writing a Successful Response to Another's Post

- Next Page: Read the Prompt Carefully

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Designing Research Assignments: Assignment Ideas

- Student Research Needs

- Assignment Guidelines

- Assignment Ideas

- Scaffolding Research Assignments

- BEAM Method

Assignment Templates

Research diaries offer students an opportunity to reflect on the research process, think about how they will address challenges they encounter, and encourage students to think about and adjust their strategies.

- Research Diary Template

- Research Diary Instructions

Alternative Assignments

There are many different types of assignments that can help your students develop their information literacy and research skills.

The assignments listed below target different skills, and some may be more suitable for certain courses than others.

- << Previous: Assignment Guidelines

- Next: Scaffolding Research Assignments >>

- Last Updated: Jun 9, 2022 12:23 PM

- URL: https://columbiacollege-ca.libguides.com/designing_assignments

- SMU Libraries

- Scholarship & Research

- Teaching & Learning

- Bridwell Library

- Business Library

- DeGolyer Library

- Fondren Library

- Hamon Arts Library

- Underwood Law Library

- Fort Burgwin Library

- Exhibits & Digital Collections

- SMU Scholar

- Special Collections & Archives

- Connect With Us

- Research Guides by Subject

- How Do I . . . ? Guides

- Find Your Librarian

- Writing Support

Research Assignment Design: Overview

- Student Learning Outcomes

- Evaluating Student Work

- Generative AI

Prioritize your learning outcomes

Students can't do it all. Pick what to focus on. For the beginning researcher, research can be a complicated process with many steps to master effectively. Your assignment might want to prioritize some of those over others.

Students experience a greater cognitive load when researching because they lack domain knowledge. You can help students focus their energies by ensuring your assignment matches your priorities.

For example, to prioritize synthesizing arguments, design an assignment around reading and writing with sources, and limit the need for finding sources. To prioritize identifying the scope of research on a topic, require searching for sources.

How do I do this?

- Determine and prioritize learning goals specific to the research process .

- Imagine a student working through the assignment. Are there parts of it that demand a lot of work, but that don't match your priorities? If so, rethink the assignment.

Focus on the research and writing process

Prompts should address both the steps along the way (picking a topic, collecting data, synthesizing sources) and the completed assignment. When instructions focus only on the final product, students will view them as a checklist to complete.

For example, requiring a certain number of sources for a paper directs students' attention to the end product. Students will pick the first sources they find, rather than understanding the process of finding many possible sources, then selecting the best ones.

- Give clear and concise directions, with explanations and examples, about why you want something a certain way.

- Make learning objectives explicit, and provide feedback for each step of the research experience.

- Provide opportunities for students to reflect on their learning.

- Allow students time to explore and reframe as they research.

- Discuss how students will know they've found enough information.

Scaffold learning

Break down and explicitly teach the different aptitudes students need to be successful. Research can overwhelm students, especially those new to the process or discipline.

- Break your assignment down into smaller tasks to ensure that students reach learning objectives successively and successfully.

- Approach this as an opportunity to help students develop research skills. Don't assume students already know how to do research. Learning is iterative, so even if they've had a library research session, a review is useful.

- Recognize the emotional toll of research and give students the time they need to experience the full spectrum of feelings, as part of the instructional design.

- Provide worksheets, handouts, or activities that help students navigate specific aspects of the research process.

- Assist students over common stumbling blocks. What will get them past bottlenecks to learning in your discipline?

Create an authentic learning experience

Make your assignment relevant to real life experiences and skills. Students learn best and successfully transfer what they're learning when they connect with the assignment, feel the excitement of discovery, or solve challenges. Through disciplinary and experiential learning, students develop different perspectives from which to view the world.

- Encourage curiosity. Give students the chance to experience some of the messiness of research, while limiting how far off track they can get through periodic check-ins.

- Show students how to practice reading, research, and writing in your discipline. All these require interrelated, separate skills.

- Address how students can transfer knowledge and skills.

- Consider problem-based learning, have students examine real-world issues.

Need More Help?

Ways librarians can help.

- Discuss your learning objectives and options for assignments with you

- "Test-drive" your assignment to ensure students will be successful

- Identify why students struggle and how to help them

- Ensure appropriate resources are available

- Identify library instructional resources to link in Canvas

- Provide research instruction for your class

- Research Assignment Stipend Support for your collaboration with a librarian on a new assignment.

- How to Write an Effective Assignment Harvard University Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning

See Example Assignments

- Introductory Research Paper Prompt

- Executive Summary Assignment

- Next: Student Learning Outcomes >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 3:15 PM

- URL: https://guides.smu.edu/research_assignments

Advertisement

Effect of Assignment Choice on Student Academic Performance in an Online Class

- Brief Practice

- Published: 26 February 2021

- Volume 14 , pages 1074–1078, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Hannah MacNaul ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6992-9991 1 , 2 ,

- Rachel Garcia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1805-4499 2 ,

- Catia Cividini-Motta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5679-9294 2 &

- Ian Thacker ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2492-2929 1

4513 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Choice of assignment has been shown to increase student engagement, improve academic outcomes, and promote student satisfaction in higher education courses (Hanewicz, Platt, & Arendt, Distance Education , 38 (3), 273–287, 2017 ). However, in previous research, choice resulted in complex procedures and increased response effort for instructors (e.g., Arendt, Trego, & Allred, Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education , 8 (1), 2–17, 2016 ). Using simplified procedures, the current study employed a repeated-measures with an alternating-treatments design to evaluate the effects of assignment choice (flash cards, study guide) on the academic outcomes of 42 graduate students in an online, asynchronous course. Slight differences between conditions were observed, but differences were not statistically significant.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Effect of Choice on Student Performance in Online Graduate Classes

Self-regulated spacing in a massive open online course is related to better learning

Matching Efficiency of Admission Procedures in Online-Education

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As access to the internet increases, more students pursuing higher education are completing online programs. In fact, nearly 50% of master’s-level applied behavior analysis training programs in the United States offer courses in an online format (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2021 ). Given the increase of students in online courses and programs, investigating instructional procedures to support students in meeting learning outcomes has become critical. In learner-centered teaching (LCT; Weimer, 2013 ), instructors aim to motivate students by giving them some control over the learning process, such as choice of assignments and choice of assignment deadlines.

In the academic context, the opportunity to select between two or more concurrently available assignments has been shown to increase student engagement, exam scores, and student satisfaction (e.g., Hanewicz et al., 2017 ). Moreover, various assignment formats—that is, flash cards and study guides—are empirically supported strategies that help students build fluency with material and improve efficiency in studying, respectively (Tincani, 2004 ). In a recent study, Jopp and Cohen ( 2020 ) identified only four studies (Arendt, Trego, & Allred, 2016 ; Cook, 2001 ; Hanewicz, Platt, & Arendt, 2017 ; Rideout, 2017 ) in which students were given a choice of assignments and, in all of these studies, choice was associated with a positive outcome (e.g., increased engagement and exam scores). However, in these studies, the arrangement of procedures in order to offer choice resulted in complex point systems (e.g., Rideout, 2017 ), a large number of assignment choices (e.g., 59 in Arendt et al., 2016 ), or a vast number of different due dates (e.g., Arendt et al., 2016 ). To address these limitations, Jopp and Cohen kept the number of assignments available in the course and their relative weights the same as in the previous iteration of the course; however, for three of the required assignments, students could choose one of the three available assignment options. In their study, assignment choice increased satisfaction with the course but did not increase learning outcomes (i.e., grade) in comparison to a previous semester when the course did not include choice. Nevertheless, students indicated that they did not have a good understanding of all of the different assignment options. Furthermore, in previous studies, students did not experience both the choice and no-choice conditions; thus, individual differences between groups may have moderated outcomes (e.g., Rideout, 2017 ).

As noted previously, choice has had a positive impact on student engagement; however, further research on procedures that can aid in the mastery of academic content while requiring few resources is warranted. This study sought to evaluate the effects of assignment choice on student academic outcomes. To extend this line of research, this study incorporated choice of assignment (i.e., flash cards and study guides) in a simpler manner, ensured that all students experienced all experimental conditions (i.e., using an alternating-treatments design), and exposed students to both assignments prior to the onset of the study.

Participants and Setting

Forty-two graduate students across two cohorts (fall 2019: n = 25; spring 2020: n = 17) who were enrolled in a fully online master’s program participated in the current study. Most students were female ( n = 39), and geographically, students were located around the United States. All students in each section participated in the study and were completing this course in partial fulfillment of the requirements to become a Board Certified Behavior Analyst. The course, which covered functional assessment methods, and instructor were the same across both cohorts. The course was administered via Canvas, a learning management platform previously used by the students in other courses. This was an 8-week asynchronous course wherein students were not required to meet on a certain day and time but had to progress through a module per week, and therefore the entire course, by certain deadlines. Modules were identical in setup, including a module description with learning objectives, a video introduction from the instructor, required readings, prerecorded lectures, a discussion board, and a quiz. Each component of the module was introduced in succession, meaning that completion of one task allowed the student to access the next task in the sequence. Additionally, in six out of eight modules, students completed an interactive practice assignment.

Materials included instructor-designed practice assignments (i.e., flash cards, study guides) developed using the online website GoConqr ( www.goconqr.com ). The flash cards and study guides covered the same subject matter and content areas (e.g., key terms and definitions), and both required approximately 15 min of the instructor’s time to develop. The practice assignments were embedded into Canvas and were presented either concurrently (i.e., choice condition) or in isolation (i.e., no-choice condition).

Dependent Variables

Dependent variables included student academic performance and preference of assignment format. Student academic performance consisted of the average score of all students per module quiz. Quizzes were worth a total of 20 points, and each consisted of scenario-based, multiple-choice, and short-answer questions, which were graded using an instructor-developed rubric. Student preference of assignment format was determined by the proportion of students who selected to complete each of the assignments during choice conditions.

Experimental Design and General Procedures

A repeated-measures with an embedded alternating-treatments design was employed to compare student performance across conditions. To mitigate any foreseen testing or sequence effects, treatment conditions were counterbalanced across cohorts and included choice, no-choice, and no-assignment (i.e., control condition) conditions. Across all conditions, students completed assigned readings, viewed the module lecture, and participated in the discussion board. Then, they either completed a practice assignment and a quiz (e.g., choice and no-choice conditions) or went straight from the discussion board to the quiz (e.g., no-assignment condition). When a practice assignment was available (choice and no-choice conditions), students were instructed to dedicate at least 10 min to the assignment, and they could complete the assignment as many times as desired until they reached a score of 100%. To receive full credit (i.e., 20 points), students were required to submit a screenshot of the score received, which also included the time spent on the assignment; thus, if a screenshot was not submitted and/or showed that students had not spent 10 min on the assignment, the students received zero points.

Exposure Phase

Students received instructions on the completion of each assignment type and completed an example of each assignment. However, these assignments covered content related to the syllabus and course structure. This exposure phase was implemented to give students the opportunity to experience both types of practice assignments prior to allowing them to choose between the two.

Choice Condition

In the choice condition, students had the option to select one assignment to complete, either flash cards or a study guide. The Canvas function Mastery Paths was utilized to present the choice of assignments. First, students selected “true” or “false” in response to a pledge statement (i.e., “I have completed all readings for this module, viewed the lecture, and participated in the discussion board.”). Following submission of a “true” response, students were given a choice between the two practice assignments. Upon the student’s selection of an assignment, the other option was no longer available. The selection of “false” in response to the pledge statement would redirect the student to the start of the module; however, no students selected “false” throughout the course of the study.

No-Choice Condition

In the no-choice condition, an assignment, either flash cards or a study guide, was assigned to the students by the instructor. There was no pledge statement, but all other components remained the same as in the choice condition.

No-Assignment Condition

In the no-assignment (i.e., control) condition, there was no pledge statement or practice assignment available for students to complete and, therefore, no points available. All other components remained the same as in the choice condition.

Procedural Fidelity

To assess procedural fidelity, a research assistant reviewed the Canvas page and recorded whether each student completed all components of each module (i.e., completing assigned readings, viewing lectures, and participating in the discussion board) in the prescribed sequence and prior to accessing the module assignment (choice and no-choice conditions only). In addition, during the choice and no-choice conditions, data were also collected on whether each participant completed only one practice assignment. Procedural fidelity was obtained for 100% of modules across both cohorts, and the average procedural fidelity score was 100%. It is important to note that data from Cohort 1 Module 1 are excluded from the procedural fidelity scores and the average quiz score across conditions because 16 of 25 students completed both the flash card and study guide assignments. Subsequently, procedural modifications were made.

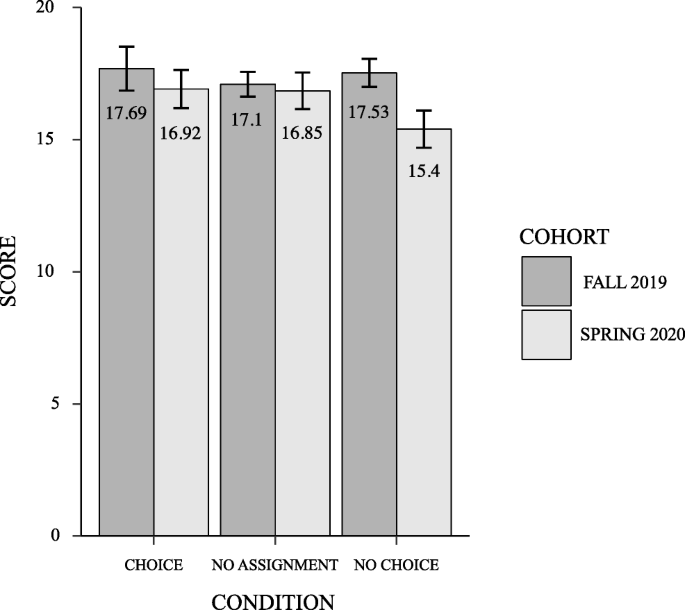

Student average quiz scores were highest in the choice condition for both cohorts, with a mean of 17.29 ( SD = 2.79, n = 99) across cohorts (see Table 1 and Fig. 1 ). Although student performance was slightly higher in the choice condition compared to the no-choice ( M = 16.65, SD = 2.62, n = 123) and no-assignment ( M = 17.00, SD = 1.83, n = 82) conditions, the differences in performance between conditions, as well as relative differences between conditions, were not statistically significant for any pairwise comparison (all p > 16). A one-way analysis of variance revealed no significant differences in mean performance scores between conditions, F (2, 301) = 1.87, p = .157. Indeed, no two conditions revealed statistically significant differences between mean quiz scores when follow-up Benjamini–Hochberg pairwise comparisons were used ( p choice vs. no choice = .17, p choice vs. no assignment = .43, p no choice vs. no assignment = .43). Further, relative gains between conditions also revealed no statistically significant pairwise differences between conditions when comparing normalized gain scores ([ M post − M pre ]/ SD ) between conditions ( p choice vs. no choice = .28, p choice vs. no assignment = .73, p no choice vs. no assignment = .21). Similarly, a comparison between the no-assignment (control) condition and the remaining two conditions using planned contrasts revealed no statistically significant differences in mean performance ( t = .24, p = .810). The quiz scores for each module are presented in Table 1 . For Cohort 2, the no-assignment condition resulted in a higher average quiz score ( M = 16.85, SD = 2.06, n = 34) compared to the no-choice condition ( M = 15.4, SD = 2.58, n = 51).

Average cohort performance across conditions. Note. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals

The frequency of students’ selection between the two practice assignment modalities (e.g., student preference of assignment format) also yielded negligible differences. Across both cohorts, in 51.5% (49 of 101) of opportunities, students chose to complete flash cards, and in 48.5% (52 of 101) of opportunities, students chose to complete the study guide during choice conditions. The difference between these proportions was not statistically significant at conventional levels (χ 2 = .181, p = .67). However, individual data indicate that certain students often chose the same assignment across modules (data are available upon request).

In this study, choice was designed in a simplified manner compared to previous research, thus increasing the feasibility of implementation for instructors. In addition, the influence of individual differences on mean values was minimized by employing an alternating-treatments design. In the current study, providing students with a choice of assignment improved performance only slightly and, ultimately, did not have any negative effects. Furthermore, based on the aggregate data, students did not show a preference for a particular assignment; this is not consistent with the findings of previous research (e.g., Jopp & Cohen, 2020 ) in which a large portion (48%–88% across the three opportunities) of students selected the same assignment. However, as noted previously, some students often chose the same assignment across modules. This may be the case, as previous studies have identified a relationship between students’ approach to learning and their preference for differing assessments (Gijbels & Dochy, 2006 ). It is also likely that the selection of a particular assignment is correlated with the response effort associated with each assignment format, a hypothesis partially supported by Jopp and Cohen ( 2020 ).

Related to response effort, previous studies have noted that a limitation of providing the choice of assignments to students is that it results in the instructor spending more time creating and grading assignments (Arendt et al., 2016 ; Hanewicz et al., 2017 ). The current study avoided this issue by providing students with fewer choices of assignments, an unlimited number of attempts to complete each assignment, and designating grades as either complete or incomplete.

Given the shortage of research evaluating effective instructional practices for online learning environments, the increase in online instruction due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and our inconclusive results regarding the use of choice in higher education learning, additional research in this area is needed. Future studies could evaluate the impact of the type of assignment available and student preference for assignments based on grades, as well as choice, in combination with other instructional practices (e.g., differentiated instruction). In this study, the Mastery Paths function allowed for the choice of assignment, but this function may also benefit students in other ways. For example, students could receive choices of different assignments (e.g., short Assignment 1 or short Assignment 2; long Assignment 3 and short Assignment 1) based on their scores on a pretest quiz. Footnote 1 With this modification in the design of a course, differentiated instruction and choice of assignment could be automatically programmed into the course structure, promoting the involvement of LCT (Weimer, 2013 ); however, additional research is needed.

This study is not without limitations. As previously mentioned, data from Cohort 1’s Module 1 were excluded because students completed both assignments due to a procedural error in setting up the module. This issue was resolved but required the addition of a question (i.e., pledge statement); however, this pledge statement was not present in all conditions. Furthermore, for Cohort 2, the no-assignment condition resulted in higher average quiz scores compared to the no-choice condition (e.g., control condition). This may have been the case because Module 3 (a no-choice condition) for Cohort 2 was in March 2020, at the start of the pandemic. Given that the stay-at-home order may have impacted childcare and job security and added additional stressors for the students, the lower quiz score on this module may be a reflection of the added environmental changes and not directly an effect of the no-choice condition. Additionally, in both cohorts, performance on the end-of-module quizzes improved across the 8 weeks, perhaps because students learned what to expect during the quizzes and to identify the most relevant information from lectures, readings, and practice assignments. Future studies may attempt to replicate these procedures, but with the randomization of entire cohorts experiencing only one condition, followed by a comparison of the performance of each cohort across conditions. To address other limitations of the current study, future studies should assess the acceptability of the conditions (i.e., social validity) and evaluate variables (e.g., preference, response effort) that impact the selection of assignment.

A task analysis describing the steps necessary to use the Mastery Path function in Canvas is available under Supplemental materials .

Arendt, A., Trego, T., & Allred, J. (2016). Students reach beyond expectations with cafeteria style grading. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 8 (1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/jarhe-03-2014-0048 .

Article Google Scholar

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2021). Verified course sequence directory. Association for Behavior Analysis International. Retrieved January 18, 2021 from https://www.abainternational.org/vcs/directory.aspx

Cook, A. (2001). Assessing the use of flexible assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 26 (6), 539–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930120093878 .

Gijbels, D., & Dochy, F. (2006). Students’ assessment preferences and approaches to learning: Can formative assessment make a difference? Educational Studies, 32 (4), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690600850354 .

Hanewicz, C., Platt, A., & Arendt, A. (2017). Creating a learner-centered teaching environment using student choice in assignments. Distance Education, 38 (3), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2017.1369349 .

Jopp, R., & Cohen, J. (2020). Choose your own assessment—Assessment choice for students in online higher education. Teaching in Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1742680 . Advance online publication.

Rideout, C. (2017). Students’ choices and achievement in large undergraduate classes using a novel flexible assessment approach. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 43 (1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1294144 .

Tincani, M. (2004). Improving outcomes for college students with disabilities: Ten strategies for instructors. College Teaching, 52 (4), 128–133. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.52.4.128-133 .

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Wiley.

Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Psychology, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, 78207, USA

Hannah MacNaul & Ian Thacker

Department of Child and Family Studies, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Hannah MacNaul, Rachel Garcia & Catia Cividini-Motta

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hannah MacNaul .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Research Highlights

• The Canvas Mastery Paths function allows instructors to automate choice of assignments into a course, as well as differentiate instruction across students.

• This study extends our understanding of effective teaching strategies in online instruction because results demonstrated that choice of assignments alone did not significantly improve student learning outcomes.

• In this study, choice of assignment was designed in a manner to allow feasibility of implementation by most instructors.

• This article includes step-by-step instructions for how to use the Canvas Mastery Paths function, provided as online Supplementary Material .

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

MacNaul, H., Garcia, R., Cividini-Motta, C. et al. Effect of Assignment Choice on Student Academic Performance in an Online Class. Behav Analysis Practice 14 , 1074–1078 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00566-8

Download citation

Accepted : 10 February 2021

Published : 26 February 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00566-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Online education

- Graduate students

- Academic performance

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- How it works

Academic Assignment Samples and Examples

Are you looking for someone to write your academic assignment for you? This is the right place for you. To showcase the quality of the work that can be expected from ResearchProspect, we have curated a few samples of academic assignments. These examples have been developed by professional writers here. Place your order with us now.

Assignment Sample

Discipline: Sociology

Quality: Approved / Passed

Discipline: Construction

Quality: 1st / 78%

Discipline: Accounting & Finance

Quality: 2:1 / 69%

Undergraduate

Discipline: Bio-Medical

Quality: 1st / 76%

Discipline: Statistics

Quality: 1st / 73%

Discipline: Health and Safety

Quality: 2:1 / 68%

Discipline: Business

Quality: 2:1 / 67%

Discipline: Medicine

Quality: 2:1 / 66%

Discipline: Religion Theology

Quality: 2:1 / 64%

Discipline: Project Management

Quality: 2:1 / 63%

Discipline: Website Development

Discipline: Fire and Construction

Discipline: Environmental Management

Discipline: Early Child Education

Quality: 1st / 72%

Analysis of a Business Environment: Coffee and Cake Ltd (CC Ltd)

Business Strategy

Application of Project Management Using the Agile Approach ….

Project Management

Assessment of British Airways Social Media Posts

Critical annotation, global business environment (reflective report assignment), global marketing strategies, incoterms, ex (exw), free (fob, fca), cost (cpt, cip), delivery …., it systems strategy – the case of oxford university, management and organisation in global environment, marketing plan for “b airlines”, prepare a portfolio review and remedial options and actions …., systematic identification, analysis, and assessment of risk …., the exploratory problem-solving play and growth mindset for …..

Childhood Development

The Marketing Plan- UK Sustainable Energy Limited

Law assignment.

Law Case Study

To Analyse User’s Perception towards the Services Provided by Their…

Assignment Samples

Research Methodology

Discipline: Civil Engineering

Discipline: Health & Manangement

Our Assignment Writing Service Features

Subject specialists.

We have writers specialising in their respective fields to ensure rigorous quality control.

We are reliable as we deliver all your work to you and do not use it in any future work.

We ensure that our work is 100% plagiarism free and authentic and all references are cited.

Thoroughly Researched

We perform thorough research to get accurate content for you with proper citations.

Excellent Customer Service

To resolve your issues and queries, we provide 24/7 customer service

Our prices are kept at a level that is affordable for everyone to ensure maximum help.

Loved by over 100,000 students

Thousands of students have used ResearchProspect academic support services to improve their grades. Why are you waiting?

"I am glad I gave my order to ResearchProspect after seeing their academic assignment sample. Really happy with the results. "

Law Student

"I am grateful to them for doing my academic assignment. Got high grades."

Economics Student

Frequently Ask Questions?

How can these samples help you.

The assignment writing samples we provide help you by showing you versions of the finished item. It’s like having a picture of the cake you’re aiming to make when following a recipe.

Assignments that you undertake are a key part of your academic life; they are the usual way of assessing your knowledge on the subject you’re studying.

There are various types of assignments: essays, annotated bibliographies, stand-alone literature reviews, reflective writing essays, etc. There will be a specific structure to follow for each of these. Before focusing on the structure, it is best to plan your assignment first. Your school will have its own guidelines and instructions, you should align with those. Start by selecting the essential aspects that need to be included in your assignment.

Based on what you understand from the assignment in question, evaluate the critical points that should be made. If the task is research-based, discuss your aims and objectives, research method, and results. For an argumentative essay, you need to construct arguments relevant to the thesis statement.

Your assignment should be constructed according to the outline’s different sections. This is where you might find our samples so helpful; inspect them to understand how to write your assignment.

Adding headings to sections can enhance the clarity of your assignment. They are like signposts telling the reader what’s coming next.

Where structure is concerned, our samples can be of benefit. The basic structure is of three parts: introduction, discussion, and conclusion. It is, however, advisable to follow the structural guidelines from your tutor.

For example, our master’s sample assignment includes lots of headings and sub-headings. Undergraduate assignments are shorter and present a statistical analysis only.

If you are still unsure about how to approach your assignment, we are here to help, and we really can help you. You can start by just asking us a question with no need to commit. Our writers are able to assist by guiding you through every step of your assignment.

Who will write my assignment?

We have a cherry-picked writing team. They’ve been thoroughly tested and checked out to verify their skills and credentials. You can be sure our writers have proved they can write for you.

What if I have an urgent assignment? Do your delivery days include the weekends?

No problem. Christmas, Boxing Day, New Year’s Eve – our only days off. We know you want weekend delivery, so this is what we do.

Explore More Samples

View our professional samples to be certain that we have the portofilio and capabilities to deliver what you need.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

The Reporter

School Assignment and School Effectiveness

A growing number of U.S. households have the opportunity to send their children to public schools outside of traditional neighborhood boundaries. Over the last decade there has been a proliferation of research on the design of centralized choice systems intended to make it easier for children to exercise choice. Millions of students have been assigned to schools using mechanisms either directly or indirectly inspired by academic work.

In recent research with several co-authors, I explore the equity, efficiency, and incentive properties of these choice systems. Aside from these properties, centralized assignment generates valuable data and quasi-experimental variation that can be used for evaluation of various educational practices and policies. I have worked with several researchers to exploit this variation to study productivity differences between schools and school models.

Immediate Acceptance

One of the most common school assignment systems is based on the concept of immediate acceptance : when applicants apply to a school, they are - offered a seat immediately if they qualify. A mechanism based on this principle was in place in Boston until 2005, and hence it is commonly known as the Boston mechanism. 1 A large number of Local Education Authorities in England also employed this mechanism, - called First Preference First.

One issue with this mechanism is that applicants do not have the incentive to rank their desired schools truthfully. That is, ranking a competitive school first may harm a student's chances at lower-ranked schools, creating strategic pressure on the applicant. Should an applicant take a risk at the school she really wants, or instead rank a safe choice first? In work with Tayfun Sönmez, I show that if families do not understand these incentives and rank their choices truthfully, then sophisticated families who understand the rules of the game benefit at the expense of the unsophisticated. 2

The poor incentive properties of immediate acceptance systems led authorities in Chicago to abandon their allocation scheme for the city's elite selective high schools in 2009. Officials in the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) observed that students with higher test scores were denied admission to their second-choice school, even though they had higher scores than students who ranked the school first. After eliciting preferences from more than 14,000 participants, CPS announced a new mechanism and asked participants to re-rank their choices. The new mechanism is a serial dictatorship where the highest-scoring student is assigned to her top choice, the next highest scoring student is assigned to her top choice among remaining schools, and so on. What is particularly surprising about this switch is that the new mechanism also did not have straightforward incentives because it limited the number of choices students could rank. Students could only rank four out of nine possible choices, necessitating strategic calculations on which choices to list and which ones to drop. In the subsequent year, they switched to a system with the same underlying algorithm, but allowed students to rank six schools.

A few years earlier, by an Act of Parliament, authorities in England outlawed First Preference First arrangements citing concerns - that the procedure is unfair to unsophisticated participants. Following this legal ruling, many districts adopted variants of the deferred acceptance algorithm, known in England as Equal Preferences. 3 Using this procedure, first formally studied by David Gale and Lloyd Shapley in 1962, applicants start by applying to their - first choice. Schools tentatively accept their preferred applicants up to capacity and reject the rest. Any rejected student applies to his next most preferred choice, and schools update their set of provisional acceptances by comparing these new proposals to students tentatively held over from the previous round. The algorithm terminates when there are no new proposals from rejected students.

The key idea is that assignments are deferred until there are no new proposals, and only then are they finalized. Unlike the First Preference First system, a student ranking a school second can displace one who ranks it first, if the school prefers that student. The reason it is called Equal Preferences is that when schools receive proposals, they do not discriminate among applicants based on where they were ranked on the applicant's preference form. As in the Chicago case, the Local Education Authorities that adopted Equal Preferences often limited the number of choices students could rank. Table 1 describes some of these transitions. 4

Table 1: School Admission Reforms

Note: Boston refers to the Boston mechanism, FPF refers to First Preference First mechanisms, GS refers to the student-proposing deferred acceptance algorithm of Gale and Shapley, and SD refers to a serial dictatorship.

Sönmez and I develop a way to rank systems based on their propensity toward manipulation. 5 Our approach makes it possible to evaluate whether the new systems are less manipulable than their predecessors. While our criterion is non-consequentialist, it allows for relative comparisons of two systems without ideal incentive properties. As shown in Table 1 it also has important positive content where, with the exception of Seattle in 2009, every example involves the adoption of a less manipulable system according to our measure.

Design of School Lotteries

An important issue in student assignment systems involves resolving situations where two applicants have identical claims for school seats, but there is only one seat left. This can happen, for instance, when two students obtain the same priority at a school because they reside in the school's walk zone, and there are more walk-zone applicants than seats. One might suspect that using separate lotteries at each school would be more fair than a single lottery because under a single lottery, if an applicant has a better lottery number than another applicant, that remains true at each school. However, together with Atila Abdulkadiroğlu and Alvin Roth, I show that a single lottery draw across all schools has better properties than school-specific lottery draws when using deferred acceptance. 6 In the case of New York City where there are 90,000 applicants each year, more than 2,000 additional applicants obtain their first choice with a single lottery draw compared to school-specific draws. 7

Another popular mechanism is based on Gale's top trading cycles (TTC) algorithm. Roughly speaking, this procedure endows students with schools and allows them to trade with one another in an ordered market where trades among top choices occur before trades among lower choices. Suppose Ann wants school 1 as her top choice but has the highest priority at school 2, while Bob wants school 2 as his top choice but has the highest priority at school 1. In the TTC algorithm, Ann and Bob would trade their assignments. In 2012, the OneApp assignment system used in the Recovery School District in New Orleans employed a mechanism based on TTC. 8 In general, there is no preferred way to conduct lotteries for TTC. Together with Jay Sethuraman, I show that in the special case where schools do not have priorities, the allocations produced with a single lottery draw and with school-specific draws are identical. 9

Boston's Choice Plan

Much of the initial work on student assignment was motivated by Boston's iconic school choice system, and it continues to inspire new scientific developments. In Boston and elsewhere, students wish to attend schools close to their home, especially at elementary school entry points. Districts recognize this by prioritizing applicants in the school's walk zone, a geographic area surrounding the school. On the other hand, such policies can increase segregation across schools as students who live near highly desired schools fill up the seats and prevent those from outside the neighborhood from having an opportunity to attend.

To ensure that out-of-neighborhood applicants - have an opportunity to attend a particular school, many choice systems follow Boston's in having a slot-specific priority structure. In Boston, for half of the school seats, applicants with walk-zone priority are ordered ahead of those who do not have walk-zone priority. For the other half, students from the walk zone are treated in the same way as students from outside the zone. This 50-50 split represents a compromise between those in favor of neighborhood schools and those favoring more choice.

When a student is eligible to attend a school both because of walk-zone priority and because of the district-wide assignment rule, the assignment mechanism must deal with another type of indifference. Since students care only about their school assignment, they are indifferent about whether they consume a walk-zone or a non-walk-zone slot. The mechanism's precedence order specifies the order in which slots are depleted. Together with Umut Dur, Scott Kominers, and Sönmez, I - show that student precedence has dramatic consequences for achieving distributional objectives. 10 In Boston, for instance, the precedence rule entirely undermined the intended effect of the 50-50 policy and the outcome was nearly identical to that without walk-zone priority at all. The reason is that applicants first depleted walk-zone slots before non-walk-zone slots. A walk-zone applicant who did not obtain a walk-zone slot competes with the general pool of applicants for non-walk-zone slots, but only after this applicant has been rejected from the walk-zone pool. This rejection induces a form of adverse selection - the applicant is rejected so he must have an unusually bad lottery number - that renders rejected walk-zone applicants not competitive for non-walk-zone slots. As a result, almost no students from the walk zone are assigned to the non-walk-zone slots, undermining the 50-50 compromise.

We develop a framework to study these features of slot-specific priorities and identify counterfactual policies that more faithfully implement policy goals. As a result of our work, Boston - substantially changed its walk-zone policy in 2014.

Boston has also completely redesigned how it determines the set of options students are allowed to rank on their choice menu. Until 2014, residents were restricted to applying to schools in one of three zones of the city and a handful of citywide schools. In 2014, the city adopted a zone-free plan where choice menus are customized based on an applicant's address. The choice menus are designed to ensure that each student is able to apply to - enough of the closest highly rated schools. Peng Shi and I use historical choices expressed in Boston to estimate models of school demand. We use these models to extrapolate the choices applicants would make under these new choice menus. Our results were discussed by school officials and played a significant role in the adoption of the new plan. We plan to update these predictions in a two-part project that will evaluate the performance of structural models of demand forecasting. Because our predictions were made in advance of the policy change, there is no scope for post-analysis bias. 11 We intend to revisit our predictions after applicants have expressed new choices in the spring of 2014, and to use the new data to assess the strengths and weaknesses of counterfactual prediction using discrete choice models of school demand.

Measurement of School Effects

Much of the excitement about school assignment mechanisms comes from the potential to engineer practical solutions that might improve welfare. In my view, an equally important role of common enrollment systems is in producing valuable data that can be used to evaluate the impact of various educational initiatives.

A longstanding question in education has been about the effects of attending charter schools, which are publicly funded schools with enhanced autonomy. When a charter school is over-subscribed, in many jurisdictions students are admitted via lottery. Records on schools' admissions in decentralized and uncoordinated systems tend to be poorly kept and infrequently audited. Together with several co-authors, I collect admissions records from Boston-area charter schools and study the effects of attending an over-subscribed charter school on short-run measures of student achievement. We find large and significant test score gains for charter lottery winners in middle and high school. 12 In subsequent work, I find that charter lottery winners at Boston high schools increase SAT and AP scores, along with evidence of a substantial shift from two- to four-year colleges. 13 In contrast, in work with Joshua Angrist and Christopher Walters, I find more mixed evidence on the performance of charter schools outside of urban areas of Massachusetts. 14

Charters are not assigned centrally in Boston, though they are now beginning to be assigned together with traditional district schools in unified enrollment systems in cities like Denver, Newark, and New Orleans. Alternative schools known as exam schools, which group together the highest-achieving students in the district, are centrally assigned in many cities based on admissions test scores. Together with Abdulkadiroğlu and Angrist, I exploit admissions discontinuities to measure the value of attending schools with high-achieving peers. On a wide range of academic outcomes, we find that marginal applicants who are accepted at exam schools do not score higher on subsequent performance metrics, such as standardized tests, than their near-peers who did not matriculate at exam schools. 15

Another school model I have investigated using lottery-based variation in a centralized match is the small high school. Together with Abdulkadiroğlu and Weiwei Hu, we exploit variation in New York City's high school match to study the effects of attending an over-subscribed small high school, which typically has fewer than 500 students across grades 9 to 12. Unlike charter schools, these schools are run with teachers who are part of the city's collective bargaining agreement. Students are much more disadvantaged than typical New York City high school students. Our results offer some of the first evidence that traditional district schools can produce achievement gains comparable to high-achieving charter schools. 16 Based on surveys, many small high schools have similar characteristics to high-achieving charter schools including high expectations and data-driven instruction. These results highlight the potential for within-district reform strategies to substantially improve student achievement.

1. A. Abdulkadiroğlu and T. Sönmez,-"School Choice: A Mechanism Design Approach," American Economic Review , 93 (2003), pp. 729-47.

2. P. A. Pathak and T. Sönmez,-"Leveling the Playing Field: Sincere and Sophisticated Players in the Boston Mechanism," American Economic Review, 98 (2008), pp. 1636-52.

3. D. Gale and L. Shapley,-"College Admissions and the Stability of Marriage," American Mathematical Monthly , 69 (1962), pp. 9‒15.

4. Table 1 is reproduced from P. A. Pathak and T. Sönmez, "School Admissions Reform in Chicago and England: Comparing Mechanisms by their Vulnerability to Manipulation," NBER Working Paper No. 16783 , February 2011, and American Economic Review , 103 (2013), pp. 80-106. This paper provides further description of the mechanisms referenced in the table.

5. Pathak and Sönmez, 2013, op. cit.

6. A. Abdulkadiroğlu, P. A. Pathak, and A. E. Roth, "Strategy-proofness versus Efficiency in Matching with Indifferences: Redesigning the New York City High School Match," NBER Working Paper No. 14864 , April 2009, and American Economic Review , 99 (2009), pp. 1954-78.

7. See Table 1 in Abdulkadiroğlu, Pathak, and Roth, 2009, op. cit.

8. A. Vanacore, "Centralized Enrollment in Recovery School District Gets Tryout," New Orleans Times-Picayune , April 16, 2012.

9. P. A. Pathak and J. Sethuraman, "Lotteries in Student Assignment: An Equivalence Result," NBER Working Paper No. 16140 , June 2010, and Theoretical Economics , 6 (2011), pp. 1-17.

10. U. M. Dur, S. D. Kominers, P. A. Pathak, and T. Sönmez, "The Demise of Walk Zones in Boston: Priorities vs. Precedence in School Choice," NBER Working Paper No. 18981 , April 2013.

11. P. A. Pathak and P. Shi, "Demand Modeling, Forecasting, and Counterfactuals, Part I," NBER Working Paper No. 19859 , January 2014.

12. A. Abdulkadiroğlu, J.D. Angrist, S.M. Dynarski, T. J. Kane, and P. Pathak, "Accountability and Flexibility in Public Schools: Evidence from Boston's Charters and Pilots," NBER Working Paper No. 15549 , November 2009, and Quarterly Journal of Economics , 126 (2009), pp. 699-748.

13. J. D. Angrist, S. R. Cohodes, S. M. Dynarski, P. A. Pathak, and C. R. Walters, "Stand and Deliver: Effects of Boston's Charter High Schools on College Preparation, Entry, and Choice," NBER Working Paper No. 19275 , July 2013.

14. J. D. Angrist, P. A. Pathak, and C. R. Walters, "Explaining Charter School Effectiveness," NBER Working Paper No. 17332 , August 2011, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics , 5 (2013), pp. 1-27.

15. A. Abdulkadiroğlu, J. D. Angrist, and P. A. Pathak, "The Elite Illusion: Achievement Effects at Boston and New York Exam Schools," NBER Working Paper No. 17264 , July 2011, and Econometrica , 82 (2014), pp. 137-96.

16. A. Abdulkadiroğlu, W. Hu, and P. A. Pathak,-"Small High Schools and Student Achievement: Lottery-Based Evidence from New York City," NBER Working Paper No. 19576 , October 2013.

Researchers

More from nber.

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Students' Achievement and Homework Assignment Strategies

Rubén fernández-alonso.

1 Department of Education Sciences, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain

2 Department of Education, Principality of Asturias Government, Oviedo, Spain

Marcos Álvarez-Díaz

Javier suárez-Álvarez.

3 Department of Psychology, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain

José Muñiz

The optimum time students should spend on homework has been widely researched although the results are far from unanimous. The main objective of this research is to analyze how homework assignment strategies in schools affect students' academic performance and the differences in students' time spent on homework. Participants were a representative sample of Spanish adolescents ( N = 26,543) with a mean age of 14.4 (±0.75), 49.7% girls. A test battery was used to measure academic performance in four subjects: Spanish, Mathematics, Science, and Citizenship. A questionnaire allowed the measurement of the indicators used for the description of homework and control variables. Two three-level hierarchical-linear models (student, school, autonomous community) were produced for each subject being evaluated. The relationship between academic results and homework time is negative at the individual level but positive at school level. An increase in the amount of homework a school assigns is associated with an increase in the differences in student time spent on homework. An optimum amount of homework is proposed which schools should assign to maximize gains in achievement for students overall.

The role of homework in academic achievement is an age-old debate (Walberg et al., 1985 ) that has swung between times when it was thought to be a tool for improving a country's competitiveness and times when it was almost outlawed. So Cooper ( 2001 ) talks about the battle over homework and the debates and rows continue (Walberg et al., 1985 , 1986 ; Barber, 1986 ). It is considered a complicated subject (Corno, 1996 ), mysterious (Trautwein and Köller, 2003 ), a chameleon (Trautwein et al., 2009b ), or Janus-faced (Flunger et al., 2015 ). One must agree with Cooper et al. ( 2006 ) that homework is a practice full of contradictions, where positive and negative effects coincide. As such, depending on our preferences, it is possible to find data which support the argument that homework benefits all students (Cooper, 1989 ), or that it does not matter and should be abolished (Barber, 1986 ). Equally, one might argue a compensatory effect as it favors students with more difficulties (Epstein and Van Voorhis, 2001 ), or on the contrary, that it is a source of inequality as it specifically benefits those better placed on the social ladder (Rømming, 2011 ). Furthermore, this issue has jumped over the school wall and entered the home, contributing to the polemic by becoming a common topic about which it is possible to have an opinion without being well informed, something that Goldstein ( 1960 ) warned of decades ago after reviewing almost 300 pieces of writing on the topic in Education Index and finding that only 6% were empirical studies.

The relationship between homework time and educational outcomes has traditionally been the most researched aspect (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Fan et al., 2017 ), although conclusions have evolved over time. The first experimental studies (Paschal et al., 1984 ) worked from the hypothesis that time spent on homework was a reflection of an individual student's commitment and diligence and as such the relationship between time spent on homework and achievement should be positive. This was roughly the idea at the end of the twentieth century, when more positive effects had been found than negative (Cooper, 1989 ), although it was also known that the relationship was not strictly linear (Cooper and Valentine, 2001 ), and that its strength depended on the student's age- stronger in post-compulsory secondary education than in compulsory education and almost zero in primary education (Cooper et al., 2012 ). With the turn of the century, hierarchical-linear models ran counter to this idea by showing that homework was a multilevel situation and the effect of homework on outcomes depended on classroom factors (e.g., frequency or amount of assigned homework) more than on an individual's attitude (Trautwein and Köller, 2003 ). Research with a multilevel approach indicated that individual variations in time spent had little effect on academic results (Farrow et al., 1999 ; De Jong et al., 2000 ; Dettmers et al., 2010 ; Murillo and Martínez-Garrido, 2013 ; Fernández-Alonso et al., 2014 ; Núñez et al., 2014 ; Servicio de Evaluación Educativa del Principado de Asturias, 2016 ) and that when statistically significant results were found, the effect was negative (Trautwein, 2007 ; Trautwein et al., 2009b ; Lubbers et al., 2010 ; Chang et al., 2014 ). The reasons for this null or negative relationship lie in the fact that those variables which are positively associated with homework time are antagonistic when predicting academic performance. For example, some students may not need to spend much time on homework because they learn quickly and have good cognitive skills and previous knowledge (Trautwein, 2007 ; Dettmers et al., 2010 ), or maybe because they are not very persistent in their work and do not finish homework tasks (Flunger et al., 2015 ). Similarly, students may spend more time on homework because they have difficulties learning and concentrating, low expectations and motivation or because they need more direct help (Trautwein et al., 2006 ), or maybe because they put in a lot of effort and take a lot of care with their work (Flunger et al., 2015 ). Something similar happens with sociological variables such as gender: Girls spend more time on homework (Gershenson and Holt, 2015 ) but, compared to boys, in standardized tests they have better results in reading and worse results in Science and Mathematics (OECD, 2013a ).

On the other hand, thanks to multilevel studies, systematic effects on performance have been found when homework time is considered at the class or school level. De Jong et al. ( 2000 ) found that the number of assigned homework tasks in a year was positively and significantly related to results in mathematics. Equally, the volume or amount of homework (mean homework time for the group) and the frequency of homework assignment have positive effects on achievement. The data suggests that when frequency and volume are considered together, the former has more impact on results than the latter (Trautwein et al., 2002 ; Trautwein, 2007 ). In fact, it has been estimated that in classrooms where homework is always assigned there are gains in mathematics and science of 20% of a standard deviation over those classrooms which sometimes assign homework (Fernández-Alonso et al., 2015 ). Significant results have also been found in research which considered only homework volume at the classroom or school level. Dettmers et al. ( 2009 ) concluded that the school-level effect of homework is positive in the majority of participating countries in PISA 2003, and the OECD ( 2013b ), with data from PISA 2012, confirms that schools in which students have more weekly homework demonstrate better results once certain school and student-background variables are discounted. To put it briefly, homework has a multilevel nature (Trautwein and Köller, 2003 ) in which the variables have different significance and effects according to the level of analysis, in this case a positive effect at class level, and a negative or null effect in most cases at the level of the individual. Furthermore, the fact that the clearest effects are seen at the classroom and school level highlights the role of homework policy in schools and teaching, over and above the time individual students spend on homework.

From this complex context, this current study aims to explore the relationships between the strategies schools use to assign homework and the consequences that has on students' academic performance and on the students' own homework strategies. There are two specific objectives, firstly, to systematically analyze the differential effect of time spent on homework on educational performance, both at school and individual level. We hypothesize a positive effect for homework time at school level, and a negative effect at the individual level. Secondly, the influence of homework quantity assigned by schools on the distribution of time spent by students on homework will be investigated. This will test the previously unexplored hypothesis that an increase in the amount of homework assigned by each school will create an increase in differences, both in time spent on homework by the students, and in academic results. Confirming this hypothesis would mean that an excessive amount of homework assigned by schools would penalize those students who for various reasons (pace of work, gaps in learning, difficulties concentrating, overexertion) need to spend more time completing their homework than their peers. In order to resolve this apparent paradox we will calculate the optimum volume of homework that schools should assign in order to benefit the largest number of students without contributing to an increase in differences, that is, without harming educational equity.

Participants

The population was defined as those students in year 8 of compulsory education in the academic year 2009/10 in Spain. In order to provide a representative sample, a stratified random sampling was carried out from the 19 autonomous regions in Spain. The sample was selected from each stratum according to a two-stage cluster design (OECD, 2009 , 2011 , 2014a ; Ministerio de Educación, 2011 ). In the first stage, the primary units of the sample were the schools, which were selected with a probability proportional to the number of students in the 8th grade. The more 8th grade students in a given school, the higher the likelihood of the school being selected. In the second stage, 35 students were selected from each school through simple, systematic sampling. A detailed, step-by-step description of the sampling procedure may be found in OECD ( 2011 ). The subsequent sample numbered 29,153 students from 933 schools. Some students were excluded due to lack of information (absences on the test day), or for having special educational needs. The baseline sample was finally made up of 26,543 students. The mean student age was 14.4 with a standard deviation of 0.75, rank of age from 13 to 16. Some 66.2% attended a state school; 49.7% were girls; 87.8% were Spanish nationals; 73.5% were in the school year appropriate to their age, the remaining 26.5% were at least 1 year behind in terms of their age.

Test application, marking, and data recording were contracted out via public tendering, and were carried out by qualified personnel unconnected to the schools. The evaluation, was performed on two consecutive days, each day having two 50 min sessions separated by a break. At the end of the second day the students completed a context questionnaire which included questions related to homework. The evaluation was carried out in compliance with current ethical standards in Spain. Families of the students selected to participate in the evaluation were informed about the study by the school administrations, and were able to choose whether those students would participate in the study or not.

Instruments

Tests of academic performance.

The performance test battery consisted of 342 items evaluating four subjects: Spanish (106 items), mathematics (73 items), science (78), and citizenship (85). The items, completed on paper, were in various formats and were subject to binary scoring, except 21 items which were coded on a polytomous scale, between 0 and 2 points (Ministerio de Educación, 2011 ). As a single student is not capable of answering the complete item pool in the time given, the items were distributed across various booklets following a matrix design (Fernández-Alonso and Muñiz, 2011 ). The mean Cronbach α for the booklets ranged from 0.72 (mathematics) to 0.89 (Spanish). Student scores were calculated adjusting the bank of items to Rasch's IRT model using the ConQuest 2.0 program (Wu et al., 2007 ) and were expressed in a scale with mean and standard deviation of 500 and 100 points respectively. The student's scores were divided into five categories, estimated using the plausible values method. In large scale assessments this method is better at recovering the true population parameters (e.g., mean, standard deviation) than estimates of scores using methods of maximum likelihood or expected a-posteriori estimations (Mislevy et al., 1992 ; OECD, 2009 ; von Davier et al., 2009 ).

Homework variables

A questionnaire was made up of a mix of items which allowed the calculation of the indicators used for the description of homework variables. Daily minutes spent on homework was calculated from a multiple choice question with the following options: (a) Generally I don't have homework; (b) 1 h or less; (c) Between 1 and 2 h; (d) Between 2 and 3 h; (e) More than 3 h. The options were recoded as follows: (a) = 0 min.; (b) = 45 min.; (c) = 90 min.; (d) = 150 min.; (e) = 210 min. According to Trautwein and Köller ( 2003 ) the average homework time of the students in a school could be regarded as a good proxy for the amount of homework assigned by the teacher. So the mean of this variable for each school was used as an estimator of Amount or volume of homework assigned .

Control variables