An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Int AIDS Soc

- v.19(3Suppl 2); 2016

Transgender social inclusion and equality: a pivotal path to development

Vivek divan.

1 United Nations Development Programme Consultant, Delhi, India

Clifton Cortez

2 United Nations Development Programme, HIV, Health, and Development Group, New York, NY, USA

Marina Smelyanskaya

3 United Nations Development Programme Consultant, New York, NY, USA

JoAnne Keatley

4 University of California, San Francisco, Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, San Francisco, CA, USA

Introduction

The rights of trans people are protected by a range of international and regional mechanisms. Yet, punitive national laws, policies and practices targeting transgender people, including complex procedures for changing identification documents, strip transgender people of their rights and limit access to justice. This results in gross violations of human rights on the part of state perpetrators and society at large. Transgender people's experience globally is that of extreme social exclusion that translates into increased vulnerability to HIV, other diseases, including mental health conditions, limited access to education and employment, and loss of opportunities for economic and social advancement. In addition, hatred and aggression towards a group of individuals who do not conform to social norms around gender manifest in frequent episodes of extreme violence towards transgender people. This violence often goes unpunished.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) views its work in the area of HIV through the lens of human rights and advances a range of development solutions such as poverty reduction, improved governance, active citizenship, and access to justice. This work directly relates to advancing the rights of transgender people. This manuscript lays out the various aspects of health, human rights, and development that frame transgender people's issues and outlines best practice solutions from transgender communities and governments around the globe on how to address these complex concerns. The examples provided in the manuscript can help guide UN agencies, governments, and transgender activists in achieving better standards of health, access to justice, and social inclusion for transgender communities everywhere.

Conclusions

The manuscript provides a call to action for countries to urgently address the violations of human rights of transgender people in order to honour international obligations, stem HIV epidemics, promote gender equality, strengthen social and economic development, and put a stop to untrammelled violence.

Those who have traditionally been marginalized by society and who face extreme vulnerability to HIV find that it is their marginalization – social, legal, and economic – which needs to be addressed as the highest priority if a response to HIV is to be meaningful and effective. Trans people's experiences suggest that although HIV is a serious concern for those who acquire it, the suffering it causes is compounded by the routine indignity, inequity, discrimination, and violence that they encounter. Trans people, and particularly trans women, have articulated this often in the context of HIV [ 1 ].

For a reader who is not trans, imagine a world in which the core of your being goes unrecognized – within the family, if and when you step into school, when you seek employment, or when you need social services such as health and housing. You have no way to easily access any of the institutions and services that others take for granted because of this denial of your existence, worsened by the absence of identity documents required to participate in society. Additionally, because of your outward appearance, you may be subject to discrimination, violence, or the fear of it. In such circumstances, how could you possibly partake in social and economic development? How could your dignity and wellbeing – physical, mental, and emotional – be ensured? And how could you access crucial and appropriate information and services for HIV and other health needs?

Trans people experience these realities every day of their lives. Yet, like all other human beings, trans people have fundamental rights – to life, liberty, equality, health, privacy, speech, and expression [ 2 ], but constantly face denial of these fundamental rights because of the rejection of the trans person's right to their gender identity. In these circumstances, there can be no attainment of the goal of universal equitable development as set out in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [ 3 ], and no effort to stem the tide of the HIV epidemic among trans people can succeed if their identity and human rights are denied.

The human rights gap – stigma, discrimination, violence

The ways in which marginalization impacts a trans person's life are interconnected; stigma and transphobia drive isolation, poverty, violence, lack of social and economic support systems, and compromised health outcomes. Each circumstance relates to and often exacerbates the other [ 4 ].

Trans people who express their gender identity from an early age are often rejected by their families [ 5 ]. If not cast out from their homes, they are shunned within households resulting in lack of opportunities for education and with no attempts to ensure attention to their mental and physical health needs. Those who express their gender identities later in life often face rejection by mainstream society and social service institutions, as they go about undoing gender socialization [ 6 ]. Hostile environments that fail to understand trans people's needs threaten their safety and are ill-equipped to offer sensitive health and social services.

Such discriminatory and exclusionary environments fuel social vulnerability over a lifetime; trans people have few opportunities to pursue education, and greater odds of being unemployed, thereby experiencing inordinately high levels of homelessness [ 6 ] and poverty [ 7 ]. Trans students experience resentment, prejudice, and threatening environments in schools [ 8 ], which leads to significant drop-out rates, with few trans people advancing to higher education [ 9 ].

Workplace-related research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans (LGBT) individuals reveals that trans workers are the most marginalized and are excluded from gainful employment, with discrimination occurring at all phases of the employment process, including recruitment, training opportunities, employee benefits, and access to job advancement [ 10 ]. This environment inculcates pessimism and internalized transphobia in trans people, discouraging them from applying for jobs [ 11 ]. These extreme limitations in employment can push trans people towards jobs that have limited potential for growth and development, such as beauticians, entertainers or sex workers [ 12 ]. Unemployment and low-paying or high risk and unstable jobs feed into the cycle of poverty and homelessness. When homeless trans people seek shelter, they are housed as per their sex at birth and not their experienced gender, and are subject to abuse and humiliation by staff and residents [ 13 ]. In these environments, many trans people choose not to take shelter [ 14 ].

Legal systems often entrench this marginalization, feed inequality, and perpetuate violence against trans people. All people are entitled to their basic human rights, and nations are obligated to provide for these under international law, including guarantees of non-discrimination and the right to health [ 2 ]; however, trans people are rarely assured of such protection under these State obligations.

Instead, trans people often live in criminalized contexts – under legislation that punishes so-called unnatural sex, sodomy, buggery, homosexual propaganda, and cross-dressing [ 12 ] – making them subject to extortion, abuse, and violence. Laws that criminalize sex work lead to violence and blackmail from the police, impacting trans women involved in this occupation [ 15 ]. Being criminalized, trans people are discouraged from complaining to the police, or seeking justice when facing violence and abuse, and perpetrators are rarely punished. When picked up for any of the aforementioned alleged crimes or under vague “public nuisance” or “vagrancy” laws, their abuse can continue at the hands of the police [ 16 ] or inmates in criminal justice systems that fail to appropriately respond to trans identities.

The transphobia that surrounds trans people's lives fuels violence against them. Documentation over the last decade reveals the disproportionate extent to which trans people are murdered, and the extreme forms of torture and inhuman treatment they are subject to [ 16 – 18 ]. When such atrocities are perpetrated against trans people, governments turn a blind eye. Trans sex workers are particularly vulnerable to brutal police conduct including rape, sometimes being sexually exploited by those who are meant to be protectors of the law [ 15 ]. In these circumstances, options to file complaints are limited and, when legally available channels do exist, trans complainants are often ignored [ 19 ].

These experiences of severe stigma, marginalization, and violence by families, communities, and State actors lead to immense health risks for trans people, including heightened risk for HIV, mental health disparities, and substance abuse [ 20 , 21 ]. However, most health systems struggle to function outside the traditional female/male binary framework, thereby excluding trans people [ 22 ]. Health personnel are often untrained to provide appropriate services on HIV prevention, care, and treatment or information on sexual and reproductive health to trans people [ 20 , 23 ]. HIV voluntary counselling and testing facilities and antiretroviral therapy (ART) sites intimidate trans people due to prior negative experiences with medical staff [ 21 , 24 , 25 ]. Additionally, when trans women test HIV positive, they are wrongly reported as men who have sex with men [ 4 ]. Consequently, testing rates in trans communities are low [ 26 ], which serves to disguise the serious burden of HIV among trans people and perpetuates the lack of investment in developing trans-sensitive health systems. The economic hardships that trans people face due to their inability to participate in the workforce further complicate access to HIV, mental health, and gender-affirming health services. In short, hostile social and legal environments contribute to health gaps, and public health systems that are unresponsive to the needs of trans people.

In addition, understanding of trans people's concerns around stigma, discrimination, and violence, related as they are to gender identity, is often limited due to their being combined with lesbian, gay, and bisexual sexual orientation issues. However, trans people's human rights concerns, grounded in their gender identity, are inherently different and necessitate their own set of approaches.

Imperatives for trans social inclusion

In order to overcome the human rights barriers trans people confront, certain measures are imperative and should be self-evident, given the standards that States are obliged to provide under international law to all human beings. Paying attention to these is key to effectively addressing the systemic marginalization that trans people experience. Such action can have immeasurable benefits, including the full participation of trans people in human development processes as well as positive health and HIV outcomes. For trans people, the change must begin with the most fundamental element – acknowledgement of their gender identity.

The right to gender recognition

For trans people, their very recognition as human beings requires a guarantee of a composite of entitlements that others take for granted – core rights that recognize their legal personhood. As the Global Commission on HIV and the Law pointed out, “In many countries from Mexico to Malaysia, by law or by practice, transgender persons are denied acknowledgment as legal persons. A basic part of their identity – gender – is unrecognized” [ 19 ]. This recognition of their gender is core to having their inherent dignity respected and, among other rights, their right to health including protection from HIV. When denied, trans people face severe impediments in accessing appropriate health information and care.

Recognizing a trans person's gender requires respecting the right of that person to identify – irrespective of the sex assigned to them at birth – as male, female, or a gender that does not fit within the male–female binary, a “third” gender as it were, as has been expressed by many traditionally existing trans communities such as hijras in India [ 27 ]. This is an essential requirement for trans people to attain full personhood and citizenship. The guarantee of gender recognition in official government-issued documents – passports and other identification cards that are required to open bank accounts, apply to educational institutions, enter into housing or other contracts or for jobs, to vote, travel, or receive health services or state subsidies – provides access to a slew of activities that are otherwise denied while being taken for granted by cisgender people. 1 Such recognition results in fuller civic participation of and by trans people. It is a concrete step in ensuring their social integration, economic advancement, and a formal acceptance of their legal equality. It can immeasurably support their empowerment and act as an acknowledgement of their dignity and human worth, changing the way they are perceived by their families, by society in general, and by police, government actors, and healthcare personnel whom they encounter in daily life. UN treaty bodies have acknowledged this vital right of trans people to be recognized. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has recommended that States “facilitate legal recognition of the preferred gender of transgender persons and establish arrangements to permit relevant identity documents to be reissued reflecting preferred gender and name, without infringements of other human rights” [ 28 ].

Freedom from violence & discrimination

Systemic strategies to reduce the violence against trans people need to occur at multiple levels, including making perpetrators accountable, facilitating legal and policy reform that removes criminality, and general advocacy to sensitize the ill-informed about trans issues and concerns. Strengthening the capacity of trans collectives and organizations to claim their rights can also act as a counter to the impunity of violence. When trans people are provided legal aid and access to judicial processes, accountability can be enforced against perpetrators. Sensitizing the police to make them partners in this work can be crucial. When political will is absent to support such attempts in highly adverse settings, trans organizations and allies can consider using international human rights mechanisms, such as shadow reports made to UN human rights processes like the Universal Periodic Review, to bring focus to issues of anti-trans violence and other human rights violations against trans people.

Providing equal access to housing, education, public facilities and employment opportunities, and developing and implementing anti-discrimination laws and policies that protect trans people in these contexts, including guaranteeing their safety and security, are essential to ensure that trans individuals are treated as equal human beings.

The right to health

For trans people, their right to health can only be assured if services are provided in a non-stigmatizing, non-discriminatory, and informed environment. This requires working to educate the healthcare sector about gender identity and expression, and zero tolerance for conduct that excludes trans people. Derogatory comments, breaches of confidentiality from providers, and denial of services on the basis of gender identity or HIV status are some of the manifestations of prejudice. The right to non-discrimination that is guaranteed to all human beings under international law must be enforced against actions that violate this principle in the healthcare system. Yet, a multi-pronged approach that supports this affirmation of trans equality together with a sensitized workforce that is capable of delivering gender-affirming surgical and HIV health services is necessary.

Building on the commitments made by the UN General Assembly in response to the HIV epidemic [ 29 ], the World Health Organization (WHO) developed good practice recommendations in relation to stigma and discrimination faced by key populations, including trans people [ 30 ]. These recommendations urge countries to introduce rights-based laws and policies and advise that, “Monitoring and oversight are important to ensure that standards are implemented and maintained.” Additionally, mechanisms should be made available “to anonymously report occurrences of stigma and/or discrimination when [trans people] try to obtain health services” [ 30 ].

Fostering stigma-free environments has been successfully demonstrated – where partnerships between trans individuals and community health nurses have improved HIV-related health outcomes [ 31 ], or where clinical sites welcome trans people and conduct thorough and appropriate physical exams, manage hormones with particular attention to ART, and engage trans individuals in HIV education [ 32 ].

Advancing trans human rights and health

For all the challenges faced by trans people in the context of their human rights and health, promising interventions and policy progress have shown that positive change is possible, although this must be implemented at scale to have significant impact. Change has occurred due to the efforts of trans advocates and human rights champions, often in critical alliances with civil society supporters as well as sensitized judiciaries, legislatures, bureaucrats, and health sector functionaries.

Key strides have been made in the context of gender recognition in some parts of the world. In the legislatures, this trend began in 2012 with Argentina passing the Gender Identity and Health Comprehensive Care for Transgender People Act , which provided gender recognition to trans people without psychiatric, medical, or judicial evaluation, and the right to access free and voluntary transitional healthcare [ 33 , 34 ]. In 2015, Malta passed the Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act , which provides a self-determined, speedy, and accessible gender recognition process. The law protects against discrimination in the government and private sectors. It also de-pathologizes gender identity by stating that people “shall not be required to provide proof of a surgical procedure for total or partial genital reassignment, hormonal therapies or any other psychiatric, psychological or medical treatment.” It presumes the capacity of minors to exercise choice in opting for gender reassignment, while recognizing parental participation and the minor's best interests. It stipulates the establishment of a working group on trans healthcare to research international best practices [ 35 ]. Pursuant to its passing the Maltese Ministry of Education working with activists also developed policy guidelines to accommodate trans, gender variant, and intersex children in the educational system [ 36 ]. Other countries, such as the Republic of Ireland and Poland, have also passed gender identity and gender expression laws, albeit of varying substance but intended to recognize the right of trans people to personhood [ 37 , 38 ]. Denmark passed legislation that eliminated the coercive requirement for sterilization or surgery as a prerequisite to change legal gender identity [ 39 ].

Trans activists and allies have also used the judicial process to claim the right to gender recognition. In South Asia, claims to recognition of a gender beyond the male–female binary have been upheld – in 2007, the Supreme Court of Nepal directed the government to recognize a third gender in citizenship documents in order to vest rights that accrue from citizenship to metis [ 40 ]; in Pakistan, the Supreme Court directed the government to provide a third gender option in national identity cards for trans people to be able to vote [ 41 ]; in 2014, the Indian Supreme Court passed a judgement directing the government to officially recognize trans people as a third gender and to formulate special programmes to support their needs [ 42 ]. These developments in law, while hopeful, are too recent to yet discern any resultant trends in improvements in trans peoples’ lives, more broadly.

More localized innovative efforts have also been made by trans organizations to counter violence, stigma, and discrimination. For instance in South Africa, Gender DynamiX, a non-governmental organization worked with the police to change the South African Police Services’ standard operating procedures in 2013. The procedures are intended to ensure the safety, dignity, and respect of trans people who are in conflict with the law, and prescribe several trans-friendly safeguards – the search of trans people as per the sex on their identity documents, irrespective of genital surgery, and detention of trans people in separate facilities with the ability to report abuse, including removal of wigs and other gender-affirming prosthetics. Provision is made for implementation of the procedures through sensitization workshops with the police [ 43 ]. In Australia, the Transgender Anti-Violence Project was started as a collaboration between the Gender Centre in Sydney and the New South Wales Police Force, the City of Sydney and Inner City Legal Centre in 2011. It provides education, referrals, and advocacy in relation to violence based on gender identity, and support for trans people when reporting violence, assistance in organizing legal aid and appearances in court [ 44 ].

Measures have also been taken to tackle discrimination faced by trans people, in recognition of their human rights – in 2015, Japan's Ministry of Education ordered schools to accept trans students according to their preferred gender identity [ 45 ]; in 2014 in Quezon City, the Philippines the municipal council passed the “Gender Fair City” ordinance to ensure non-discrimination of LGBT people in education, the workplace, media depictions, and political life. This law prohibits bullying and requires gender-neutral bathrooms in public spaces and at work [ 46 ]; in Ecuador, Alfil Association worked on making healthcare accessible to trans people, including training and sensitization meetings for health workers and setting up a provincial health clinic for trans people in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, staffed by government physicians who had undergone the training; and Transbantu Zambia set up a small community house providing temporary shelter for trans people, assisting them in difficult times or while undergoing hormone therapy. Similar housing support has been provided by community organizations with limited resources in Jamaica and Indonesia. 2

Towards sustainable development: time for change

Although there are other examples of human rights progress for trans people, much of this change is isolated, non-systemic, and insufficient. Trans people continue to live in extremely hostile contexts. What is required is change and progress at scale. The international community's recent commitment towards Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) presents an opportunity to catalyze and expand positive interventions [ 3 ].

Preventing human rights violations and social exclusion is key to sustainable and equitable development. This is true for trans people as much as other human beings, just as the achievement of all 17 SDGs is of paramount importance to all people, including trans people. Of these SDGs, the underpinning support for trans people's health and human rights is contained in SDG 3 –“Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages,” SDG 10 – “Reduce inequality within and among countries,” and SDG 16 – “Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.”

The SDGs are guided by the UN Charter and grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. They envisage processes that are “people-centered, gender-sensitive, respect human rights and have a particular focus on the poorest, most vulnerable and those furthest behind” and a “just, equitable, tolerant, open and socially inclusive world in which the needs of the most vulnerable are met” [ 3 ]. They reiterate universal respect for human rights and dignity, justice and non-discrimination, and a world of equal opportunity permitting the full realization of human potential for all irrespective of race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, disability, or other status . The relationship between the SDGs and trans people's concerns has been robustly articulated in the context of inclusive development [ 47 ].

UN Member States have unequivocally agreed to this new common agenda for the immediate future. The SDGs demand an unambiguous, farsighted, and inclusive demonstration of political will. Their language clearly reflects the most urgent needs of trans people, for whom freedom from violence and discrimination, the right to health and legal gender recognition are inextricably linked.

Specifically in regard to trans people, the SDGs are a call to immediate action on several fronts: governments need to engage with trans people to understand their concerns, unequivocally support the right of trans people to legal gender recognition, support the documentation of human rights violations against them, provide efficient and accountable processes whereby violations can be safely reported and action taken, guarantee the prevention of such violations, and ensure that the whole gamut of robust health and HIV services are made available to trans people. Only then can trans people begin to imagine a world that respects their core personhood, and a world in which dignity, equality, and wellbeing become realities in their lives.

Acknowledgements and funding

The authors are grateful for the work of courageous trans activists around the world who have overcome tremendous challenges and continue to battle disparities as they bring about positive change. Many encouraging examples cited in this manuscript would be impossible without their contribution. The authors also thank Jack Byrne, an expert on trans health and human rights, whose work on the UNDP Discussion Paper on Transgender Health and Human Rights (2013) served as an inspiration for this piece, and JoAnne Keatley's effort to provide writing, editorial comment, and oversight. UNDP staff and consultants, who contributed time to this manuscript, were supported by UNDP.

1 Cisgender people identify and present in a way that is congruent with their birth-assigned sex. Cisgender males are birth-assigned males who identify and present themselves as male.

2 These illustrations are based on information gathered in the process of developing a tool to operationalize the Consolidated Guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations (WHO, 2014), through interviews with and questionnaires sent to trans activists. See also reference 31.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

The concept for this manuscript was a result of collaborative work between all four authors. VD provided key ideas for content and led the writing for the manuscript. CC provided thought leadership and contributed writing, particularly on the SDGs, while MS provided writing and editorial input, as well as other support. JK advised on content and provided writing and editorial input and guidance. All authors have read and approved the final version.

The University of Chicago Library News

Transgender rights: Progress and setbacks

June is Pride Month for the LGBTQIA+ community. Pride began in June 1970 in the wake of the Stonewall Riots in Greenwich Village the year before. The first Pride Parade in New York City was held on June 28, 1970 and attracted several thousand marchers. Today, millions attend Pride events all over the world.

Already facing an increase in the likelihood of being the victim of hate crimes , recently a record number of new laws were passed that negatively impact transgender individuals. This article will summarize relevant laws at the federal and state levels as well as provide resources to learn more about laws targeting LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Federal Law

In Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia (590 US _____ (2020)), the United States Supreme Court held 6-3 that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act protects gay, lesbian, and transgender employees from discrimination in the workplace. While a landmark decision, the holding did not extend to settings outside of the workplace. You can read about the decision and listen to the oral arguments here . For the filings and related cases, Proquest is a helpful source.

On June 17, 2021, the Biden administration extended Title IX protections to transgender students by requiring that schools receiving federal funds not discriminate on the basis of gender identity. As 31 states have introduced bills banning transgender students from participating in sports that match their gender identity, transgender students now have some recourse in the event of discrimination.

Currently awaiting action by the Senate, H.R.5, the Equality Act , would prohibit discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity in public accommodations and facilities, schools, employment, and other settings. The bill would also prohibit denying access to bathrooms that match an individual’s gender identity. To view legislative history and documents related to H.R.5, check out ProQuest Congressional.

The ACLU maintains a helpful guide to legislation affecting transgender people. Easily navigable by topic, the site contains links to bills (both proposed and enacted) that discriminate against transgender individuals. Congress.gov also contains links to each state’s legislative sites. The National Conference of State Legislatures allows users to track bills across jurisdictions by subject matter.

For example, Montana recently passed SB 280 that only allows for a gender change on a birth certificate if the petitioner can show proof via court order that an individual’s sex was changed through a surgical procedure. As not all individuals who identify as transgender actually undergo surgery, this law keeps some transgender individuals from having their birth certificates reflect their gender identity, causing persecution and confusion.

Arkansas passed HB1570, the SAFE Act, to deny hormones and certain medical procedures to minors. Framed as “protecting children,” the law targets transgender individuals’ desired medical treatments by singling out procedures that only a transgender individual would seek.

Continuing with the same “bathroom bill” debates that have been raging over the past decade, Tennessee allows for individuals who claim to have been forced to share a bathroom with a transgender individual in a school building to sue the school district for psychological harm. As schools are often limited in funding, this may have the effect of a school district’s becoming afraid to accommodate transgender students for fear of being sued.

Want to learn more? Here is a list of other resources.

Diversity and Inclusion at University of Chicago

LGBTQIA Research Guide

Trans@UChicago

Library closed for Juneteenth and Independence Day 2024 holidays

June 2024 D'Angelo Law Library Emerging Technologies Update

Doi service now available from uchicago library, current exhibits.

Scav Hunt at UChicago: Seeking Fun, Finding Tradition Until Aug. 9, 2024

Workshops & Events

Libra (newsletter)

Media Contact

Rachel Rosenberg Director of Communications [email protected]

Cookies in use

Understanding the transgender community.

Transgender people come from all walks of life, and HRC Foundation has estimated that there are more than 2 million of us across the United States. We are parents, siblings, and kids. We are your coworkers, your neighbors, and your friends. We are 7-year-old children and 70-year-old grandparents. We are a diverse community, representing all racial and ethnic backgrounds, as well as all faith traditions.

The word “transgender” – or trans – is an umbrella term for people whose gender identity is different from the sex assigned to us at birth. Although the word “transgender” and our modern definition of it only came into use in the late 20th century, people who would fit under this definition have existed in every culture throughout recorded history.

Alongside the increased visibility of trans celebrities like Laverne Cox, Jazz Jennings or the stars of the hit Netflix series “Pose,” three out of every ten adults in the U.S. personally knows someone who is trans. As trans people become more visible, we aim to increase understanding of our community among our friends, families, and society.

What does it mean to be trans?

The trans community is incredibly diverse. Some trans people identify as trans men or trans women, while others may describe themselves as non-binary, genderqueer, gender non-conforming, agender, bigender or other identities that reflect their personal experience. Some of us take hormones or have surgery as part of our transition, while others may change our pronouns or appearance. Roughly three-quarters of trans youth that responded to an HRC Foundation and University of Connecticut survey identified with terms other than strictly “boy” or “girl.” This suggests that a larger portion of this generation’s youth are identifying somewhere on the broad trans spectrum.

What challenges do trans people face?

While trans people are increasingly visible in both popular culture and in daily life, we still face severe discrimination, stigma and systemic inequality. Some of the specific issues facing the trans community are:

- Lack of legal protection – Trans people face a legal system that often does not protect us from discrimination based on our gender identity. Despite a recent U.S. Supreme Court Decision that makes it clear that trans people are legally protected from discrimination in the workplace, there is still no comprehensive federal non-discrimination law that includes gender identity - which means trans people may still lack recourse if we face discrimination when we’re seeking housing or dining in a restaurant. Moreover, state legislatures across the country are debating – and in some cases passing – legislation specifically designed to prohibit trans people from accessing public bathrooms that correspond with our gender identity, or creating exemptions based on religious beliefs that would allow discrimination against LGBTQ+ people.

- Poverty – Trans people live in poverty at elevated rates, and for trans people of color, these rates are even higher. Around 29% of trans adults live in poverty , as well 39% of Black trans adults, 48% of Latine trans adults and 35% of Alaska Native, Asian, Native Americans and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander trans adults.

- Stigma, Harassment and Discrimination – About half a decade ago, only one-quarter of people in the United States supported trans rights, and support increased to 62% by the year 2019. Despite this progress, the trans community still faces considerable stigma due to more than a century of being characterized as mentally ill, socially deviant and sexually predatory. While these intolerant views have faded in recent years for lesbians and gay men, trans people are often still ridiculed by a society that does not understand us. This stigma plays out in a variety of contexts – from lawmakers who leverage anti-trans stigma to score cheap political points; to family, friends or coworkers who reject trans people upon learning about our trans identities; and to people who harass, bully and commit serious violence against trans people. This includes stigma that prevents them from accessing necessary services for their survival and well-being. Only 30% of women’s shelters are willing to house trans women. While recent legal progress has been made, 27% of trans people have been fired, not hired or denied a promotion due to their trans identity. Too often, harassment has led trans people to avoid exercising their most basic rights to vote. HRC Foundation’s research shows that 49% of trans adults, and 55% of trans adults of color said they were unable to vote in at least one election in their life because of fear of or experiencing discrimination at the polls.

- Violence Against Trans People – Trans people experience violence at rates far greater than the average person. Over a majority ( 54% ) of trans people have experienced some form of intimate partner violence, 47% have been sexually assaulted in their lifetime and nearly one in ten were physically assaulted in between 2014 and 2015. This type of violence can be fatal. At least 27 trans and gender non-conforming people have been violently killed in 2020 thus far, the same number of fatalities observed in 2019.

- Lack of Healthcare Coverage – An HRC Foundation analysis found that 22% of trans people and 32% of trans people of color have no health insurance coverage. More than one-quarter ( 29% ) of trans adults have been refused health care by a doctor or provider because of their gender identity. This sobering data reveals a healthcare system that fails to meet the needs of the trans community.

- Identity Documents – The widespread lack of accurate identity documents among trans people can have an impact on every aspect of their lives, including access to emergency housing or other public services. Without identification, one cannot travel, register for school or access many services that are essential to function in society. Many states do not allow trans people to update their identification documents to match their gender identity. Others require evidence of medical transition – which can be prohibitively expensive and is not something that all trans people want – as well as fees for processing new identity documents, which may make them unaffordable for some members of the trans community.

While advocates continue working to remedy these disparities, change cannot come too soon for trans people. Visibility – especially positive images of trans people in the media and society – continues to make a critical difference for us; but visibility is not enough and can come with real risks to our safety, especially for those of us who are part of other marginalized communities. That is why the Human Rights Campaign is committed to continuing to support and advocate for the trans community, so that the trans Americans who are and will become your friends, neighbors, coworkers and family members have an equal chance to succeed and thrive.

Related Resources

Transgender

HRC’s Brief Guide to Reporting on Transgender Individuals

Transgender, Health & Aging, Workplace

Debunking the Myths: Transgender Health and Well-Being

Bisexual, Allies, Coming Out, Transgender

Glossary of Terms

Love conquers hate., wear your pride this year..

100% of every HRC merchandise purchase fuels the fight for equality.

Choose a Location

- Connecticut

- District of Columbia

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Pennsylvania

- Puerto Rico

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- West Virginia

Leaving Site

You are leaving hrc.org.

By clicking "GO" below, you will be directed to a website operated by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, an independent 501(c)(3) entity.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Americans’ Complex Views on Gender Identity and Transgender Issues

Most favor protecting trans people from discrimination, but fewer support policies related to medical care for gender transitions; many are uneasy with the pace of change on trans issues, table of contents.

- A rising share say a person’s gender is determined by their sex at birth

- Many Americans point to science when asked what has influenced their views on whether gender can differ from sex assigned at birth

- Public sees discrimination against trans people and limited acceptance

- About four-in-ten say society has gone too far in accepting trans people

- Plurality of adults say views on gender identity issues are changing too quickly

- Most say they’re not paying close attention to news about bills related to transgender people

- About six-in-ten would favor requiring that transgender athletes compete on teams that match their sex at birth

- Views on many policies related to transgender issues vary by age, party, and race and ethnicity

- Sizable shares say forms and government documents should include options other than ‘male’ and ‘female’

- About three-in-ten parents of K-12 students say their children have learned about people who are trans or nonbinary at school

- Acknowledgments

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

- Panel recruitment

- Sample design

- Questionnaire development and testing

- Data collection protocol

- Data quality checks

- Dispositions and response rates

- A note about the Asian sample

Pew Research Center conducted this study to better understand Americans’ views about gender identity and people who are transgender or nonbinary. These findings are part of a larger project that includes findings from six focus groups on the experiences and views of transgender and nonbinary adults and estimates of the share of U.S. adults who say their gender is different from the sex they were assigned at birth .

This analysis is based on a survey of 10,188 U.S. adults. The data was collected as a part of a larger survey conducted May 16-22, 2022. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology . See here to read more about the questions used for this report and the report’s methodology .

References to White, Black and Asian adults include only those who are not Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

All references to party affiliation include those who lean toward that party. Republicans include those who identify as Republicans and those who say they lean toward the Republican Party. Democrats include those who identify as Democrats and those who say they lean toward the Democratic Party.

References to college graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor’s degree or more. “Some college” includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a degree.

The terms “transgender” and “trans” are used interchangeably throughout this report to refer to people whose gender is different from the sex they were assigned at birth.

As the United States addresses issues of transgender rights and the broader landscape around gender identity continues to shift, the American public holds a complex set of views around these issues, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

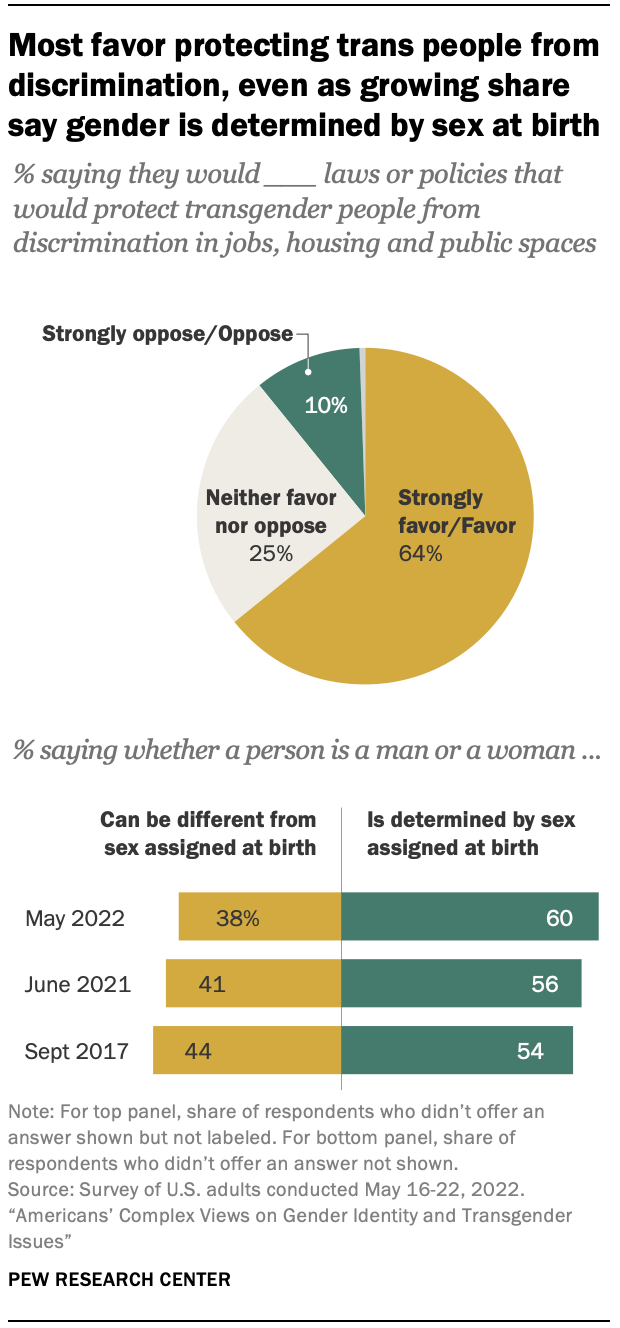

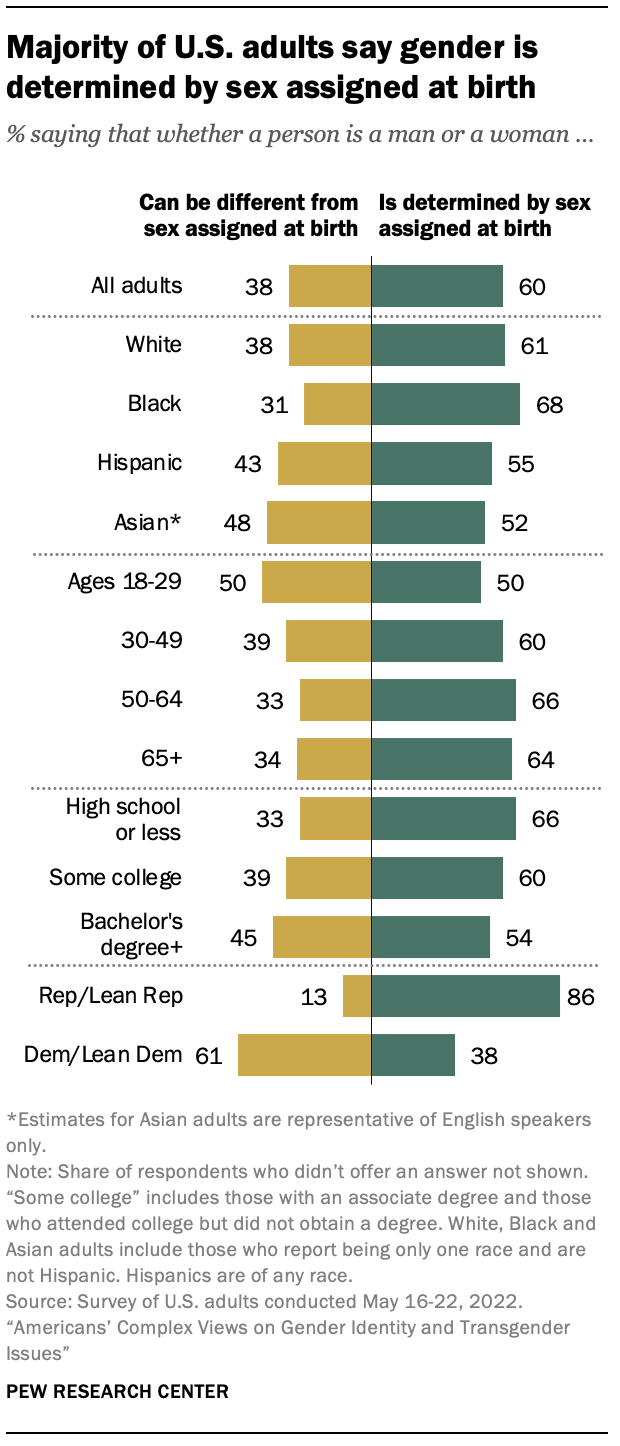

Roughly eight-in-ten U.S. adults say there is at least some discrimination against transgender people in our society, and a majority favor laws that would protect transgender individuals from discrimination in jobs, housing and public spaces. At the same time, 60% say a person’s gender is determined by their sex assigned at birth, up from 56% in 2021 and 54% in 2017.

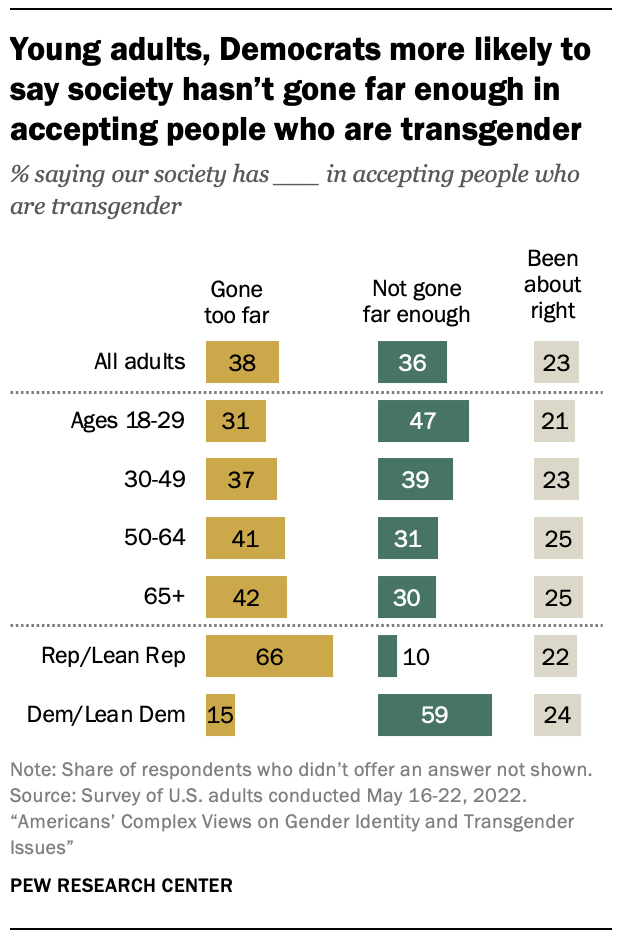

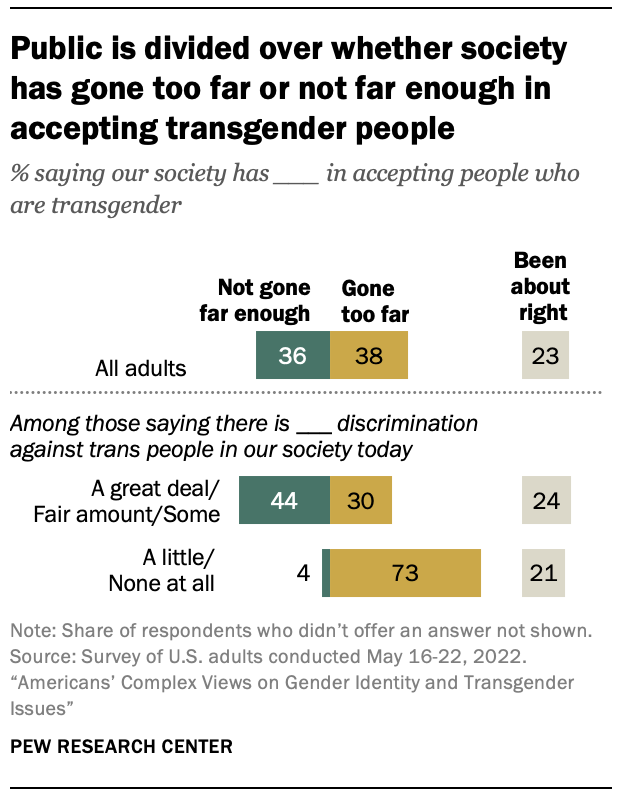

The public is divided over the extent to which our society has accepted people who are transgender: 38% say society has gone too far in accepting them, while a roughly equal share (36%) say society hasn’t gone far enough. About one-in-four say things have been about right. Underscoring the public’s ambivalence around these issues, even among those who see at least some discrimination against trans people, a majority (54%) say society has either gone too far or been about right in terms of acceptance.

The fundamental belief about whether gender can differ from sex assigned at birth is closely aligned with opinions on transgender issues. Americans who say a person’s gender can be different from their sex at birth are more likely than others to see discrimination against trans people and a lack of societal acceptance. They’re also more likely to say that our society hasn’t gone far enough in accepting people who are transgender. But even among those who say a person’s gender is determined by their sex at birth, there is a diversity of viewpoints. Half of this group say they would favor laws that protect trans people from discrimination in certain realms of life. And about one-in-four say forms and online profiles should include options other than “male” or “female” for people who don’t identify as either.

Related: The Experiences, Challenges and Hopes of Transgender and Nonbinary U.S. adults

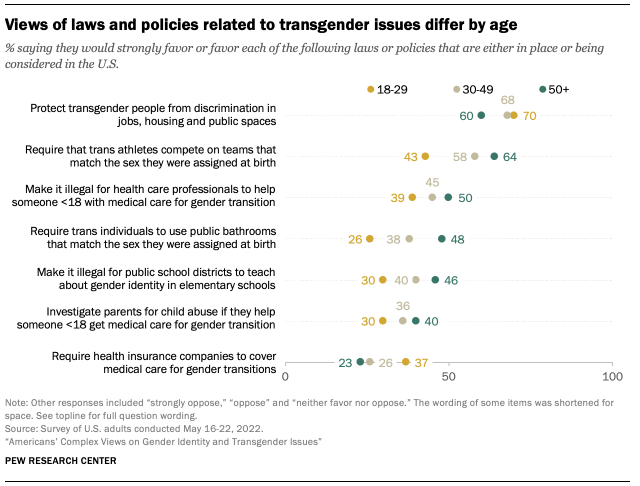

When it comes to issues surrounding gender identity, young adults are at the leading edge of change and acceptance. Half of adults ages 18 to 29 say someone can be a man or a woman even if that differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. This compares with about four-in-ten of those ages 30 to 49 and about a third of those 50 and older. Adults younger than 30 are also more likely than older adults to say society hasn’t gone far enough in accepting people who are transgender (47% vs. 39% of 30- to 49-year-olds and 31% of those 50 and older)

These views differ even more sharply by partisanship. Democrats and those who lean to the Democratic Party are more than four times as likely as Republicans and Republican leaners to say that a person’s gender can be different from the sex they were assigned at birth (61% vs. 13%). Democrats are also much more likely than Republicans to say our society hasn’t gone far enough in accepting people who are transgender (59% vs. 10%). For their part, 66% of Republicans say society has gone too far in accepting people who are transgender.

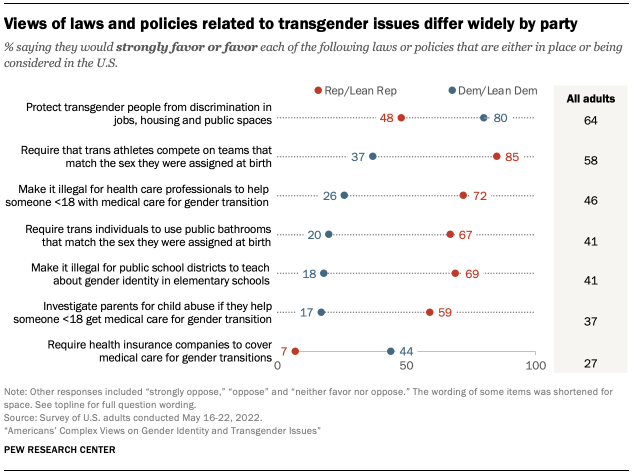

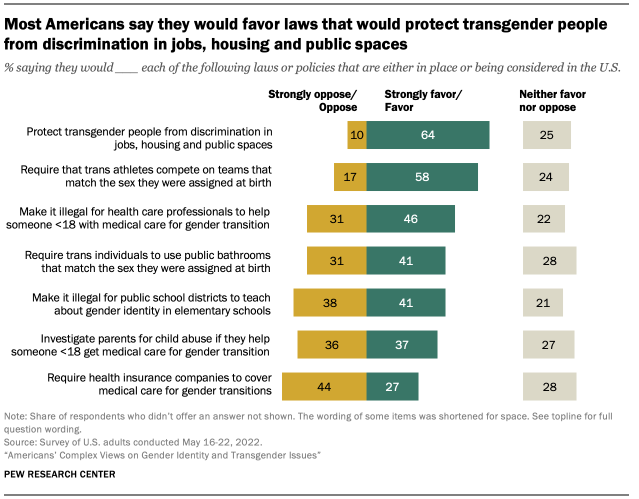

Amid a national conversation over these issues, many states are considering or have put in place laws or policies that would directly affect the lives of transgender and nonbinary people – that is, those who don’t identify as a man or a woman. Some of these laws would limit protections for transgender and nonbinary people; others are aimed at safeguarding them. The survey finds that a majority of U.S. adults (64%) say they would favor laws that would protect transgender individuals from discrimination in jobs, housing and public spaces such as restaurants and stores. But there is also a fair amount of support for specific proposals that would limit how trans people can participate in certain activities and navigate their day-to-day lives.

Roughly six-in-ten adults (58%) favor proposals that would require transgender athletes to compete on teams that match the sex they were assigned at birth (17% oppose this, 24% neither favor nor oppose). 1 And 46% favor making it illegal for health care professionals to provide someone younger than 18 with medical care for a gender transition (31% oppose). The public is more evenly split when it comes to making it illegal for public school districts to teach about gender identity in elementary schools (41% favor and 38% oppose) and investigating parents for child abuse if they help someone younger than 18 get medical care for a gender transition (37% favor and 36% oppose). Across the board, views on these policies are deeply divided by party.

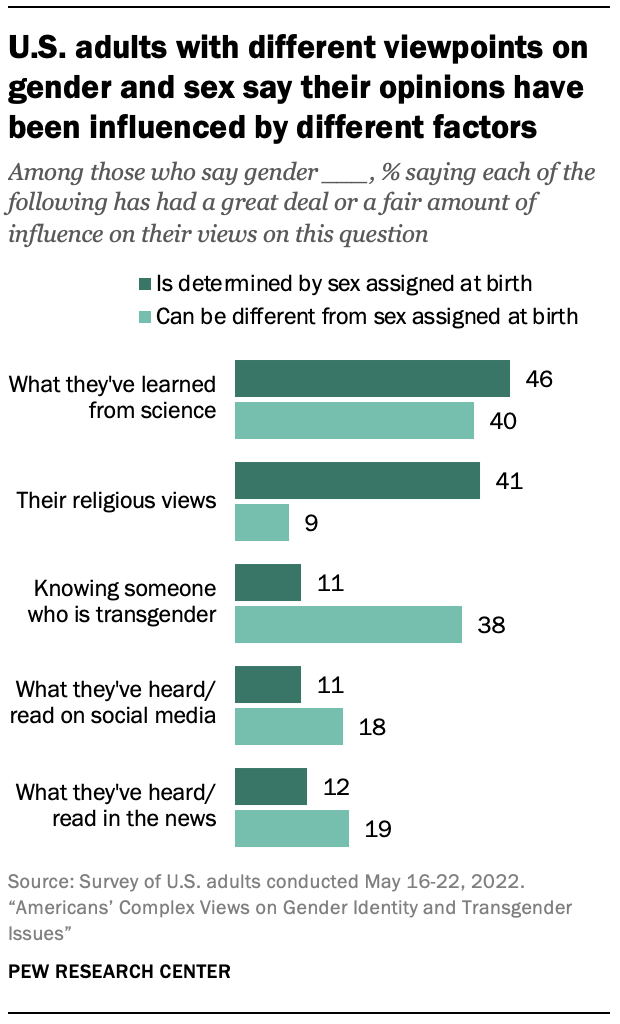

When asked what has influenced their views on gender identity – specifically, whether they believe a person can be a different gender than the sex they were assigned at birth – those who believe gender can be different from sex at birth and those who do not point to different factors. For the former group, the most influential factors shaping their views are what they’ve learned from science (40% say this has influenced their views a great deal or a fair amount) and knowing someone who is transgender (38%). Some 46% of those who say gender is determined by sex at birth also point to what they’ve learned from science, but this group is far more likely than those who say a person’s gender can be different from their sex at birth to say their religious beliefs have had at least a fair amount of influence on their opinion (41% vs. 9%).

The nationally representative survey of 10,188 U.S. adults was conducted May 16-22, 2022. Previously published findings from the survey show that 1.6% of U.S. adults are trans or nonbinary, and the share is higher among adults younger than 30. More than four-in-ten U.S. adults know someone who is trans and 20% know someone who is nonbinary. Among the other key findings in this report:

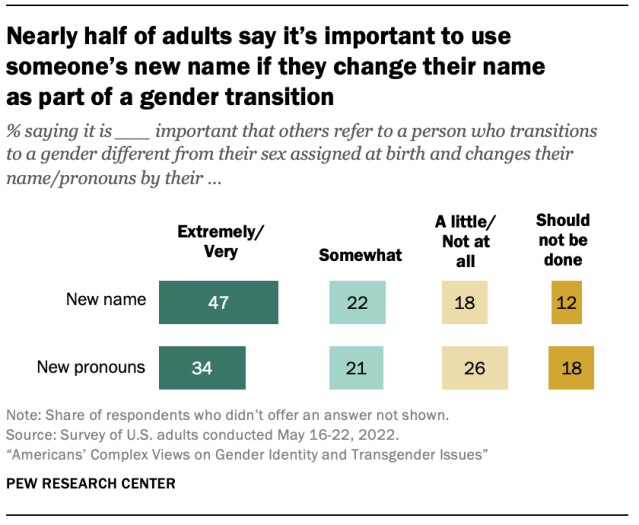

Nearly half of U.S. adults (47%) say it’s extremely or very important to use a person’s new name if they transition to a gender that is different from the sex they were assigned at birth and change their name. A smaller share (34%) say the same about using someone’s new pronouns (such as “he” instead of “she”). A majority of Democrats (64%) – compared with 28% of Republicans – say it’s at least very important to use someone’s new name if they go through a gender transition and change their name. And while 51% of Democrats say it’s extremely or very important to use someone’s new pronouns, just 14% of Republicans say the same.

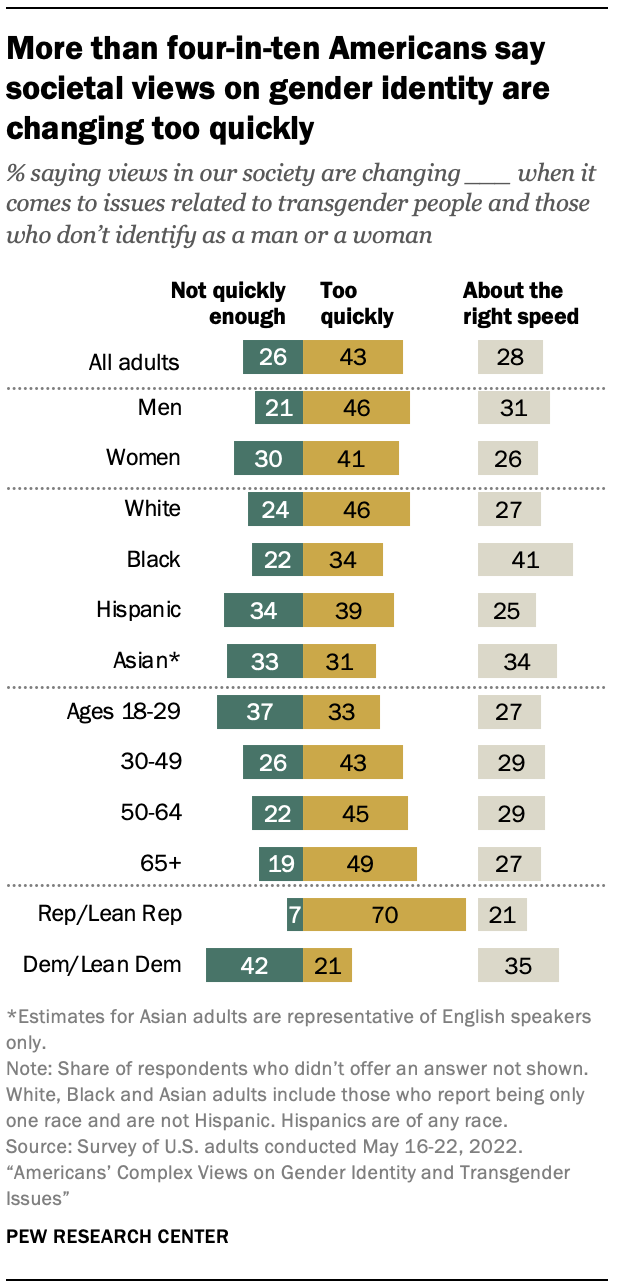

Many Americans express discomfort with the pace of change around issues of gender identity. Some 43% say views on issues related to people who are transgender or nonbinary are changing too quickly, while 26% say things aren’t changing quickly enough and 28% say the pace of change is about right. Adults ages 65 and older are the most likely to say views on these issues are changing too quickly; conversely, those younger than 30 are the most likely to say they’re not changing quickly enough.

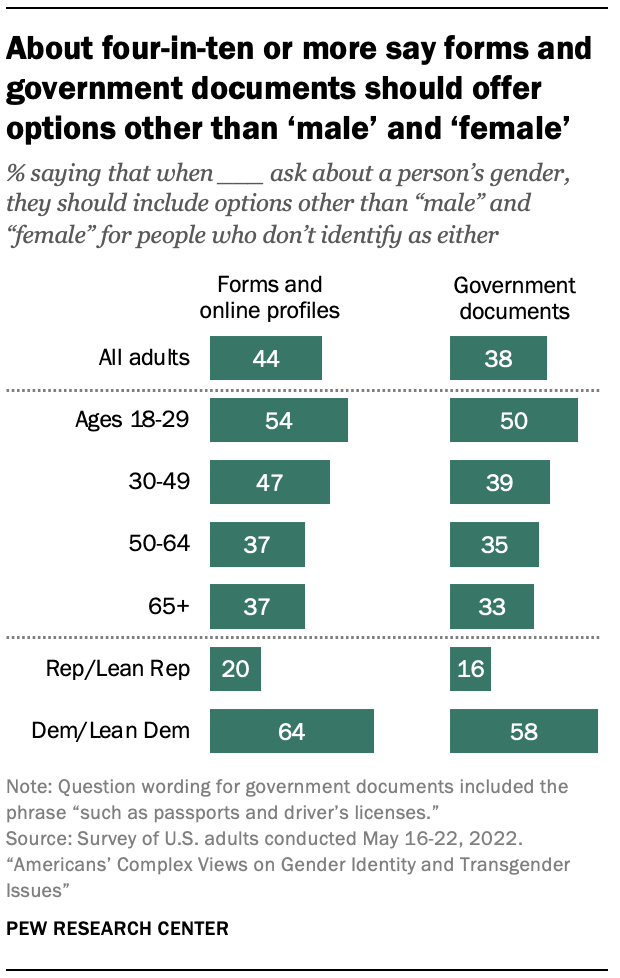

More than four-in-ten (44%) say forms and online profiles that ask about a person’s gender should include options other than “male” and “female” for people who don’t identify as either. Some 38% say the same about government documents such as passports and driver’s licenses. Half of adults younger than 30 say government documents that ask about a person’s gender should provide more than two gender options, compared with about four-in-ten or fewer among those in older age groups. Views differ even more widely by party: While majorities of Democrats say forms and online profiles (64%) and government documents (58%) should offer options other than “male” and “female,” about eight-in-ten Republicans say they should not (79% say this about forms and online profiles and 83% say this about government documents).

Democrats and Republicans who agree that a person’s gender is determined by their sex at birth often have different views on transgender issues. A majority (61%) of Democrats – but just 31% of Republicans – who say a person’s gender is determined by the sex they were assigned at birth say there is at least a fair amount of discrimination against transgender people in our society today. And while 62% of Democrats who say gender is determined by sex at birth say they would favor policies that protect trans individuals against discrimination, fewer than half of their Republican counterparts say the same.

Democrats’ views on some transgender issues vary by age. Among Democrats younger than 30, about seven-in-ten (72%) say someone can be a man or a woman even if that’s different from the sex they were assigned at birth, and 66% say society hasn’t gone far enough in accepting people who are transgender. Smaller majorities of Democrats 30 and older express these views. Age is less of a factor among Republicans. In fact, similar shares of Republicans ages 18 to 29 and those 65 and older say a person’s gender is determined by their sex at birth (88% each) and that society has gone too far in accepting people who are transgender (67% of Republicans younger than 30 and 69% of those 65 and older).

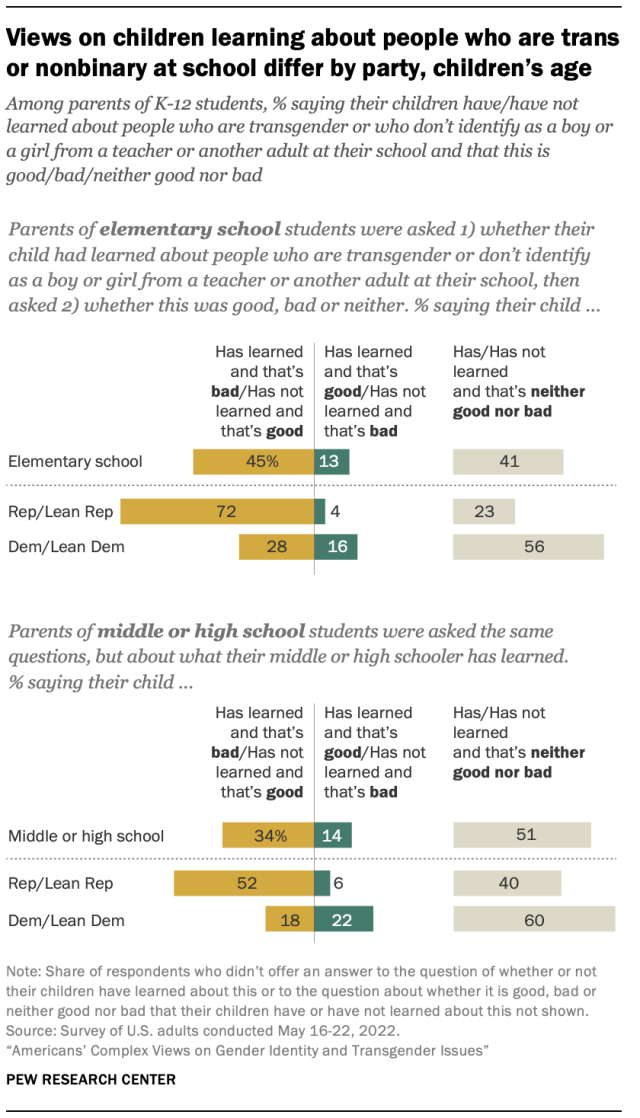

About three-in-ten parents of K-12 students (29%) say at least one of their children has learned about people who are transgender or nonbinary from a teacher or another adult at their school. Similar shares across regions and in urban, suburban and rural areas say their children have learned about this in school, as do similar shares of Republican and Democratic parents. Views on whether it’s good or bad that their children have or haven’t learned about people who are trans or nonbinary at school vary by party and by children’s age. For example, among parents of children in elementary school, 45% say either that their children have learned about this and that’s a bad thing or that they haven’t learned about it and that’s a good thing. A smaller share of parents of middle and high schoolers (34%) say the same. Republican parents are much more likely than Democratic parents to say this, regardless of their child’s age.

Six-in-ten U.S. adults say that whether a person is a man or a woman is determined by their sex assigned at birth. This is up from 56% one year ago and 54% in 2017 . No single demographic group is driving this change, and patterns in who is more likely to say this are similar to what they were in past years.

Today, half or more in all age groups say that gender is determined by sex assigned at birth, but this is a less common view among younger adults. Half of adults younger than 30 say this, lower than the 60% of 30- to 49-year-olds who say the same. Even higher shares of those 50 to 64 (66%) and those 65 and older (64%) say a person’s gender is determined by their sex at birth.

The party gap on this issue remains wide. The vast majority of Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP say gender is determined by sex assigned at birth (86%), compared with 38% of Democrats and Democratic leaners. Most Democrats say that whether a person is a man or a woman can be different from their sex at birth (61% vs. just 13% of Republicans). Liberal Democrats are particularly likely to hold this view – 79% say a person’s gender can be different from sex at birth, compared with 45% of moderate or conservative Democrats. Meanwhile, 92% of conservative Republicans say gender is determined by sex at birth and 74% of moderate or liberal Republicans agree.

Democrats ages 18 to 29 are also substantially more likely than older Democrats to say that someone’s gender can be different from their sex assigned at birth, although majorities of Democrats across age groups share this view. About seven-in-ten Democrats younger than 30 say this (72%), compared with about six-in-ten or fewer in the older age groups. Among Republicans, there is no clear pattern by age. About eight-in-ten or more Republicans across age groups – including 88% each among those ages 18 to 29 and those 65 and older – say a person’s gender is determined by their sex at birth.

The view that a person’s gender is determined by their sex assigned at birth is more common among those with lower levels of educational attainment and those living in rural areas or in the Midwest or South. This view is also more prevalent among men and Black Americans.

A solid majority of those who do not know a transgender person say that whether a person is a man or a woman is determined by sex assigned at birth (68%), while those who do know a trans person are more evenly split. About half say gender is determined by sex assigned at birth (51%), while 48% say gender and sex assigned at birth can be different.

Though Republicans who know a trans person are more likely than Republicans who don’t to say gender can be different from sex assigned at birth, more than eight-in-ten in both groups (83% and 88%, respectively) say gender is determined by sex at birth. Meanwhile, there are large differences between Democrats who do and do not know a transgender person. A majority of Democrats who do know a trans person (72%) say someone can be a man or a woman even if that differs from their sex assigned at birth, while those who don’t know anyone who is transgender are about evenly split (48% say gender is determined by sex assigned at birth while 51% say it can be different).

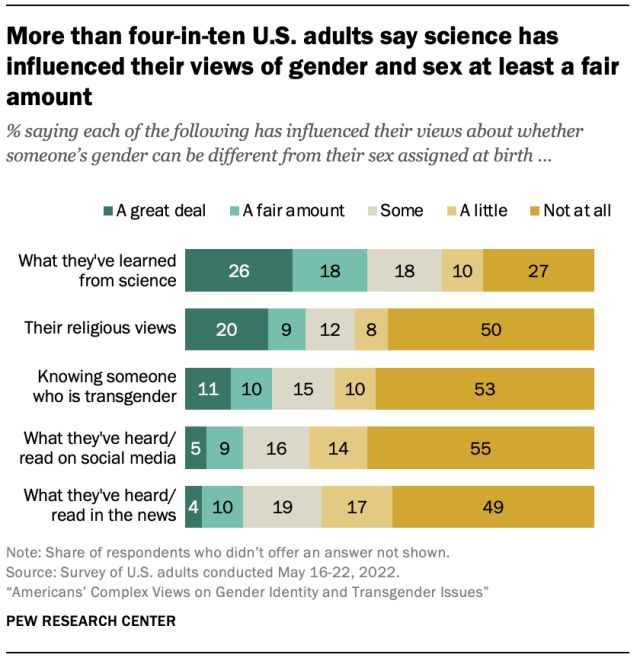

When asked about factors that have influenced their views about whether someone’s gender can be different from the sex they were assigned at birth, 44% say what they’ve learned from science has had a great deal or a fair amount of influence. About three-in-ten (28%) point to their religious views and about two-in-ten (22%) say knowing someone who is transgender has influenced their views at least a fair amount. Smaller shares say what they’ve heard or read in the news (15%) or on social media (14%) has had a great deal or a fair amount of influence on their views.

The factors people point to on this topic differ by whether or not they say gender is determined by sex at birth. Among those who say that whether someone is a man or a woman is determined by the sex they were assigned at birth, 46% say what they’ve learned from science has influenced their views on this at least a fair amount, while 41% say the same about their religious views. About one-in-ten point to what they’ve heard or read in the news (12%), what they’ve heard or read on social media (11%) or knowing someone who’s transgender (11%).

Among those who say someone can be a man or a woman even if that’s different from the sex they were assigned at birth, 40% say their views on this topic have been influenced at least a fair amount by what they’ve learned from science. A similar share say the same about knowing a transgender person (38%). Smaller shares in this group say what they’ve heard or read in the news (19%) or on social media (18%) or their religious views (9%) have had a great deal or a fair amount of influence.

Among those who say gender is determined by sex assigned at birth, adults younger than 30 stand out as being more likely than their older counterparts to say their knowledge of science (60%), what they’ve heard or read on social media (22%) or knowing someone who is trans (17%) influenced this view a great deal or a fair amount. In turn, those ages 65 and older tend to be more likely than younger age groups to cite their religious views (51% in the older group say this has had at least a fair amount of influence).

Republicans who say gender is determined by sex assigned at birth are more likely than Democrats with the same view to say their knowledge of science (52% vs. 40%) and their religious views (45% vs. 34%) have had at least a fair amount of influence, while Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say the news (17% vs. 10%), social media (16% vs. 10%) and knowing someone who is trans (15% vs. 9%) have influenced them – though the shares are still small among both groups.

On the flip side, among those who say someone’s gender can be different from the sex they were assigned at birth, adults younger than 30 are also more likely than older adults to say social media has contributed to this view at least a fair amount (33% vs. 15% or fewer among older age groups). Adults ages 65 and older are more likely than their younger counterparts to say what they’ve learned from science has influenced their view (46% vs. 40% or fewer).

Democrats who say whether someone is a man or a woman can be different from their sex at birth are more likely than Republicans with the same view to say that what they’ve learned from science (43% vs. 26%) and knowing someone who is transgender (40% vs. 26%) has influenced their view a great deal or a fair amount.

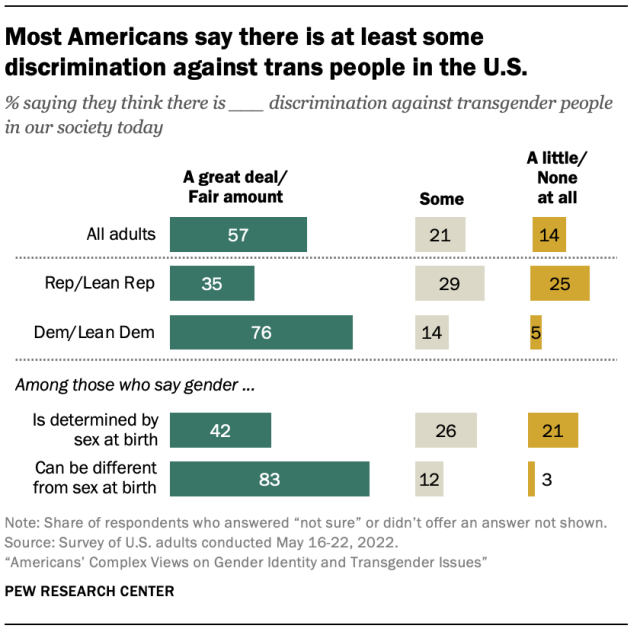

Roughly eight-in-ten Americans say transgender people face at least some discrimination, and relatively few believe our society is extremely or very accepting of people who are trans. These views differ widely by partisanship and by beliefs about whether someone’s gender can differ from the sex they were assigned at birth.

Overall, 57% of adults say there is a great deal or a fair amount of discrimination against transgender people in our society today. An additional 21% say there is some discrimination against trans people, and 14% say there is a little or none at all.

There are modest differences in views on this issue across demographic groups. Women (62%) are more likely than men (52%) to say there is a great deal or a fair amount of discrimination against transgender people, and college graduates (62%) are more likely than those with less education (55%) to say the same.

There is, however, a wide partisan divide in these views: While 76% of Democrats and those who lean to the Democratic Party say there is a great deal or a fair amount of discrimination against trans people, 35% of Republicans and Republican leaners share that assessment. One-in-four Republicans see little or no discrimination against this group, compared with 5% of Democrats.

These views are also linked with underlying opinions about whether a person’s gender can be different from their sex assigned at birth. Among those who say someone can be a man or a woman even if that’s different from the sex they were assigned at birth, 83% say there is a great deal or a fair amount of discrimination against trans people. Even so, some 42% of those who hold the alternative point of view – that gender is determined by sex assigned at birth – also see at least a fair amount of discrimination. Among Democrats who say gender is determined by sex at birth, that share rises to 61%.

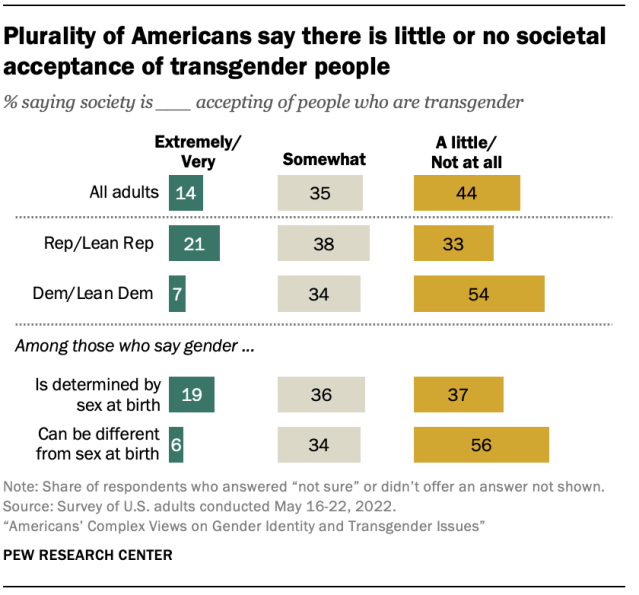

Relatively few adults (14%) say society is extremely or very accepting, while about a third (35%) say it is somewhat accepting. A plurality (44%) says our society is a little or not at all accepting of trans people.

Again, these views are strongly linked with partisanship. Democrats have a much more negative view than Republicans, with 54% of Democrats saying society is a little accepting or not at all accepting of transgender people, compared with a third of Republicans.

And, as with views of discrimination, assessments of societal acceptance are linked to underlying views about how gender is determined. Those who say one’s gender can be different from the sex they were assigned at birth see less acceptance: 56% say society is a little accepting or not accepting at all of people who are transgender. This compares with 37% among those who say gender is determined by sex at birth. Republicans who say gender is determined by sex at birth are more likely than Democrats who say the same to believe that society is at least somewhat accepting of people who are transgender (61% vs. 47%).

While a majority of Americans see at least a fair amount of discrimination against transgender people and relatively few see widespread acceptance, 38% say our society has gone too far in accepting them. Some 36% say society has not gone far enough in accepting people who are trans, and 23% say the level of acceptance has been about right.

These views differ along demographic and partisan lines. Young adults (ages 18 to 29) and those with a bachelor’s degree or more education are among the most likely to say society hasn’t gone far enough in accepting people who are trans. Men, White adults and those without a four-year college degree are among the most likely to say society has gone too far in this regard.

There is a wide partisan divide as well. Roughly six-in-ten Democrats (59%) say society hasn’t gone far enough in accepting people who are transgender, while 15% say it has gone too far (24% say it’s been about right). Republicans’ views are almost the inverse: 10% say society hasn’t gone far enough and 66% say it’s gone too far (22% say it’s been about right).

Even among those who see at least some discrimination against trans people, a majority (54%) say society has either gone too far in accepting trans people or been about right; 44% say society hasn’t gone far enough.

Many say it’s important to use someone’s new name, pronouns when they’ve gone through a gender transition

Nearly half of adults (47%) say it’s extremely or very important that if a person who transitions to a gender that’s different from their sex assigned at birth changes their name, others refer to them by their new name. An additional 22% say this is somewhat important. Three-in-ten say this is a little or not at all important (18%) or that it shouldn’t be done (12%).

Smaller shares say that if a person transitions to a gender that’s different from their sex assigned at birth and starts going by different pronouns (such as “she” instead of “he”), it’s important that others refer to them by their new pronouns. About a third (34%) say this is extremely or very important, and 21% say this is somewhat important. More than four-in-ten say this is a little or not at all important (26%) or it should not be done (18%).

These views differ along many of the same dimensions as other topics asked about. While 80% of those who believe someone’s gender can be different from their sex assigned at birth also say it’s extremely or very important to use a person’s new name when they’ve gone through a gender transition, 27% of those who think gender is determined by one’s sex assigned at birth share this opinion. The pattern is similar when it comes to use of preferred pronouns.

Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say it’s extremely or very important to refer to a person using their new name or pronouns. When it comes to pronouns, a majority of Republicans (55%), compared with only 17% of Democrats, say using someone’s new pronouns when they’ve been through a gender transition is not at all important or should not be done.

There are some demographic differences as well, with women more likely than men and those with a four-year college degree more likely than those with less education to say it’s extremely or very important to use a person’s new name or pronouns when referring to them.

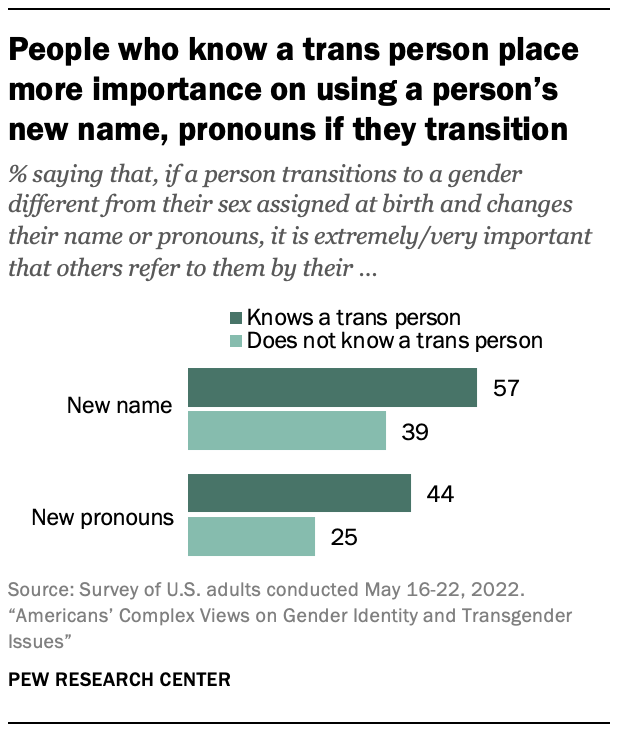

In addition, people who say they know someone who is trans are more likely than those who do not to say this is extremely or very important. Even so, substantial shares of those who don’t know a trans person view this as important. For example, 39% of those who don’t know someone who is transgender say it’s extremely or very important to refer to a person who goes through a gender transition and changes their name by their new name.

Many Americans are not comfortable with the pace of change that’s occurring around issues involving gender identity. Some 43% say views on issues related to people who are transgender and nonbinary are changing too quickly. About one-in-four (26%) say things are not changing quickly enough, and 28% say they are changing at about the right speed.

Women (30%) are more likely than men (21%) to say views on these issues are not changing quickly enough, and adults younger than 30 are more likely than their older counterparts to say the same. Among those ages 18 to 29, 37% say views on these issues are not changing quickly enough; this compares with 26% of those ages 30 to 49, 22% of those ages 50 to 64 and 19% of those 65 and older. At the same time, White adults (46%) are more likely than Black (34%), Hispanic (39%) or Asian (31%) adults to say views are changing too quickly .

Opinions also differ sharply by partisanship. Among Democrats, a plurality (42%) say views on issues involving transgender and nonbinary people are not changing fast enough, and 21% say they are changing too quickly. About a third (35%) say the speed is about right. By contrast, 70% of Republicans say views on these issues are changing too quickly, while only 7% say views aren’t changing fast enough. About one-in-five Republicans (21%) say they’re changing at about the right speed.

Respondents were asked in an open-ended format why they think views are changing too quickly or not quickly enough, when it comes to issues surrounding transgender and nonbinary people. For those who say things are changing too quickly, responses fell into several different categories. Some indicated that new ways of thinking about gender were inconsistent with their religious beliefs. Others expressed concern that the long-term consequences of medical gender transitions are not well-known, or that changing views on gender identity are merely a fad that’s being pushed by the media. Still others said they worry that there’s too much discussion of these issues in schools these days.

For those who say views are not changing quickly enough, some pointed to discrimination and a lack of acceptance of trans and nonbinary people. Others pointed to legislative initiatives in some states aimed at restricting the rights of trans and nonbinary people. Many also said that too many people in our society aren’t open to change when it comes to these issues. 2

In their own words: Why do some people think views on issues related to transgender people and those who don’t identify as a man or a woman are changing too quickly ?

General concerns about the pace of change

“The issue is so new to me I can’t keep up. I don’t know what to think about all of this new information. I’m baffled by so many changes.”

“It takes quite a bit of time for society to accept changes. I have not been aware of this issue for very long. I am relatively conservative and feel that changes need time to be accepted.”

Religious reasons

“People now believe everyone should just forget about their birth identity and just go along with what they think they are. God made us all for a reason and if He intended us to pick our gender then there would be no reason to be born with specific male or female parts .”

“I have a personal religious belief that sex is an essential part of our eternal identity and that identifying as something other than you are … just doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

“I believe GOD created a man and a woman. We have overstepped our bounds in messing with the miracle of life. I side with my creator.”

Concerns about long-term medical consequences

“We do not know the long-term health problems of hormone therapy, especially in young children.”

“More time needs to pass to study mental, physical, emotional ramifications of medications & surgeries, especially when done before puberty and/or adulthood.”

“Accepting gender fluidity, especially for younger children, seems quick. Also, medical treatments related to gender for people under 18 seems to be being accepted without longer term studies.”

It’s a fad/Driven by the media

“I respect people’s views about themselves, and I will refer to them in the way they want to be referred to, but I believe it’s become trendy because it’s being pushed so much in culture, especially for children.”

“News media, social media and entertainment media companies are trying to change, and it seems they have been succeeding in changing public opinion on this issue for many people.”

“It is encouraging kids who are easily influenced to participate in the ‘in’ fad when their brains are not fully developed.”

Concerns about schools

“Elementary school students should not be subjected to instruction on sex identity, any questions the child asks should be referred to a parent.”

“I think that young people are exposed to these issues at too early an age. I believe that it is up to the parents, and I oppose schools that want to include it in the ‘curriculum.’”

“It’s being pushed on society and especially on younger children, confusing them all the more. This is not something that should be taught in schools.”

In their own words: Why do some people think views on issues related to transgender people and those who don’t identify as a man or a woman are changing too slowly ?

Discrimination

“There is far too much discrimination, hate, and violence directed toward people who are brave enough to stand up for who they truly are. We, as a country and as a society, need to respect how people want to identify themselves and be kind toward one another, end of story.”

“Protections for basic rights to self-determination in identity, health care choices, privacy, and consensual relationships should be a bare minimum that our society can provide for everyone – transgender people included . ”

“There’s too much discrimination. People need to quit controlling other people’s private lives. I consider them very brave for having the courage to be who they identify with . ”

“Equal protection has not kept up with trans issues, including trans youth and the right to gender-affirming care.”

Legislative efforts

“Acceptance is not changing quick enough. There remains discrimination and elected officials are passing laws that make it more difficult for transgender individuals in society to live, work and exist.”

“We are going backwards with all the anti-gay & -trans legislation that is being passed.”

“For every step forward, it feels like there are two steps back with reactive conservative laws.”

“These laws are working to restrict the rights of trans and nonbinary people, and also discrimination is still very high which results in elevated rates of suicide, poverty, violence and homelessness especially for people of color.”

“The spate of laws being proposed that would take away the rights of transgender people is evidence that we’re a long way from treating them right.”

Society is not open to change

“Too many people are simply stuck in the binary. We, as a society, need to just accept that someone else’s gender identity is whatever they say it is and it rarely has any bearing on the lives of others.”

“These are people. Who they say they are is all that matters. Society, mostly conservatives, doesn’t understand change in any form. So, they fight it. And they hinder the ability for others to learn about themselves and others, which slows growing as a society to a crawl.”

“It’s an issue that has been in the closet for centuries. It’s time to acknowledge and accept that gender identity is a spectrum and not binary.”

“We are not accepting the changes. We refuse to see what is in front of us. We care too much about not changing the status quo as we know it.”

“Society often views this as a phase or a period of uncertainty in their life. Instead, it’s about a person bringing their gender identity in line with what they have experienced internally all their life.”

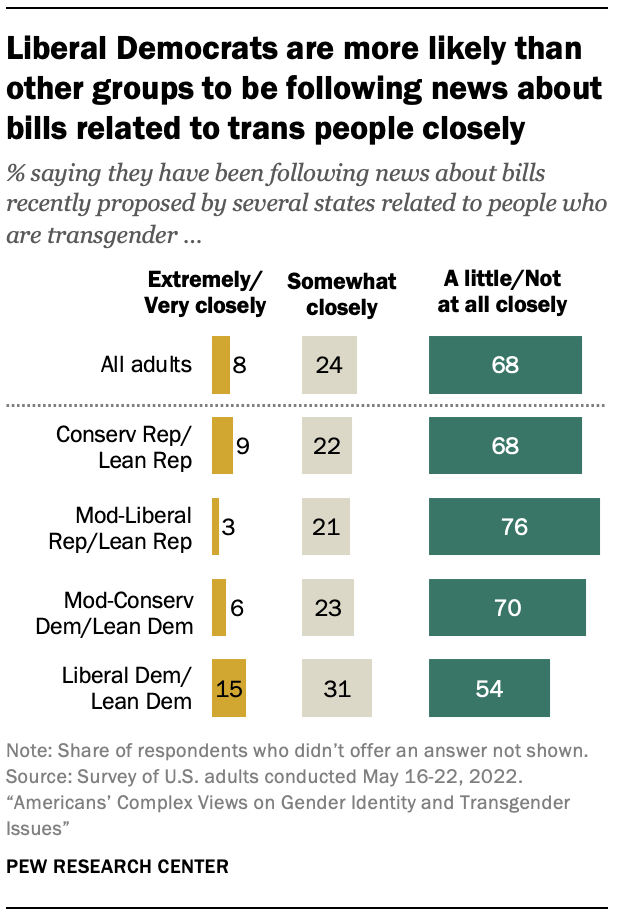

Many states are considering legislation related to people who are transgender, but a relatively small share of U.S. adults (8%) say they’re following news about these bills extremely or very closely. Another 24% say they’re following this somewhat closely, while about two-thirds say they’re following it either a little closely (23%) or not all closely (44%). 3

Only about one-in-ten or less across age, racial and ethnic groups, and across levels of educational attainment, say they are following news about bills related to people who are transgender extremely or very closely. Six-in-ten or more across demographic groups say they’re following news about these bills a little closely or not closely at all.

Liberal Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (46%) are more likely than moderate and conservative Democrats (29%) to say they are following news about state bills related to people who are transgender at least somewhat closely. Conservative Republicans and Republican leaners (31%) are more likely than their moderate and liberal counterparts (24%) – but less likely than liberal Democrats – to be following news about these bills at least somewhat closely. Still, half or more among each of these groups say they have been following news about this a little or not at all closely.

The survey asked respondents how they feel about some current laws and policies that are either in place or being considered across the U.S. related to transgender issues. Only two of seven items are either endorsed or rejected by a majority: 64% say they would favor policies that protect transgender individuals from discrimination in jobs, housing, and public spaces such as restaurants and stores, and 58% say they would favor policies that require that transgender athletes compete on teams that match the sex they were assigned at birth rather than the gender they identify with.

Even though there is not a majority consensus on most of these laws or policies, there are gaps of at least 10 percentage points on three items. Some 46% say they would favor making it illegal for health care professionals to provide someone younger than 18 with medical care for gender transitions, and 41% would favor requiring transgender individuals to use public bathrooms that match the sex they were assigned at birth rather than the gender they identify with; 31% say they would oppose each of these. Meanwhile, more say they would oppose (44%) than say they would favor (27%) requiring health insurance companies to cover medical care for gender transitions.

Views are more divided when it comes to laws and policies that would make it illegal for public school districts to teach about gender identity in elementary schools (41% favor and 38% oppose) or that would investigate parents for child abuse if they helped someone younger than 18 get medical care for a gender transition (37% favor and 36% oppose). Some 21% and 27%, respectively, say they’d neither favor nor oppose these policies.