- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

David Cameron and the Brexit referendum

The road to the chequers plan, the northern ireland backstop plan and the challenge to may’s leadership, ongoing opposition to may’s revised brexit plan, deadline extensions, “indicative votes,” and may’s resignation, boris johnson and the brexit finish line.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Council on Foreign Relations - Brexit and the Commonwealth of Nations

- Table Of Contents

Recent News

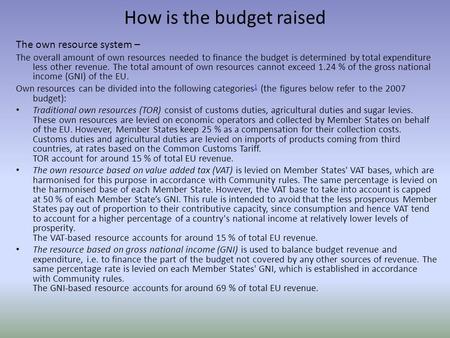

Brexit , the United Kingdom ’s withdrawal from the European Union (EU), which formally occurred on January 31, 2020. The term Brexit is a portmanteau coined as shorthand for British exit . In a referendum held on June 23, 2016, some 52 percent of those British voters who participated opted to leave the EU, setting the stage for the U.K. to become the first country ever to do so. The details of the separation were negotiated for more than two years following the submission of Britain’s formal request to leave in March 2017, and British Prime Minister Theresa May , whose legacy is inextricably bound to Brexit, was forced to resign in July 2019 after she repeatedly failed to win approval from Parliament for the separation agreement that she had negotiated with the EU. Ultimately, Brexit was accomplished under her successor, Boris Johnson .

In 2013, responding to growing Euroskepticism within his Conservative Party , British Prime Minister David Cameron first pledged to conduct a referendum on whether the U.K. should remain in the EU. Even before the surge of immigration in 2015 that resulted from upheaval in the Middle East and Africa, many Britons had become distressed with the influx of migrants from elsewhere in the EU who had arrived through the EU’s open borders. Exploiting this anti-immigrant sentiment , the Nigel Farage -led nationalist United Kingdom Independence Party made big gains in elections largely at the expense of the Conservatives . Euroskeptics in Britain were also alarmed by British financial obligations that had come about as a result of the EU’s response to the euro-zone debt crisis and the bailout of Greece (2009–12). They argued that Britain had relinquished too much of its sovereignty . Moreover, they were fed up with what they saw as excessive EU regulations on consumers, employers, and the environment .

The Labour and Liberal Democratic parties generally favoured remaining within the EU, and there were still many Conservatives, Cameron among them, who remained committed to British membership, provided that a minimum of reforms could be secured from the U.K.’s 27 partners in the EU. Having triumphed in the 2015 U.K. general election , Cameron prepared to make good on his promise to hold a referendum on EU membership before 2017, but first he sought to win concessions from the European Council that would address some of the concerns of those Britons who wanted out of the EU (an undertaking Cameron characterized as “Mission Possible”). In February 2016 EU leaders agreed to comply with a number of Cameron’s requests, including, notably, allowing the U.K. to limit benefits for migrant workers during their first four years in Britain, though this so-called “emergency brake” could be applied only for seven years. Britain also was to be exempt from the EU’s “ever-closer union” commitment, was permitted to maintain the pound sterling as its currency, and was reimbursed for money spent on euro-zone bailouts.

With that agreement in hand, Cameron scheduled the referendum for June 2016 and took the lead in the “remain” campaign, which focused on an organization called Britain Stronger in Europe and argued for the benefits of participation in the EU’s single market. The “leave” effort, which coalesced around the Vote Leave campaign, was headed up by ex-London mayor Boris Johnson , who was widely seen as a challenger for Cameron’s leadership of the Conservative Party. Johnson repeatedly claimed that the EU had “changed out of all recognition” from the common market that Britain had joined in 1973, and Leavers argued that EU membership prevented Britain from negotiating advantageous trade deals. Both sides made gloom-and-doom proclamations regarding the consequences that would result from their opponents’ triumph, and both sides lined up expert testimony and studies supporting their visions. They also racked up celebrity endorsements that ranged from the powerful (U.S. Pres. Barack Obama , German Chancellor Angela Merkel , and International Monetary Fund managing director Christine Lagarde on the remain side and former British foreign minister Lord David Owen and Republican U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump on the leave side) to the glamorous (actors Benedict Cumberbatch and Sir Patrick Stewart backing the remain effort and actor Sir Michael Caine and former cricket star Ian Botham being in the leave ranks).

Opinion polling on the eve of the referendum showed both sides of the Brexit question fairly evenly divided, but, when the votes were tallied, some 52 percent of those who voted had chosen to leave the EU. Cameron resigned in order to allow his successor to conduct the negotiations on the British departure. In announcing his resignation, he said, “I don’t think it would be right for me to try to be the captain that steers our country to its next destination.”

Theresa’s May’s Brexit failure

Although Johnson had appeared to be poised to replace Cameron, as events played out, Home Secretary Theresa May became the new leader of the Conservative Party and prime minister in July 2016. May, who had opposed Brexit, came into office promising to see it to completion, On March 29, 2017, she formally submitted a six-page letter to European Council Pres. Donald Tusk invoking article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty , thus opening a two-year window for negotiations between the U.K. and the EU over the details of separation. In the letter, May pledged to enter the discussions “constructively and respectfully, in a spirit of sincere cooperation.” She also hoped that a “bold and ambitious Free Trade Agreement” would result from the negotiations.

Attempting to secure a mandate for her vision of Brexit, May called a snap election for Parliament for June 2017. Instead of gaining a stronger hand for the Brexit negotiations, however, she saw her Conservative Party lose its governing majority in the House of Commons and become dependent on “confidence and supply” support from Northern Ireland ’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). May’s objective of arriving at a cohesive approach for her government’s Brexit negotiations was further complicated by the wide disagreement that persisted within the Conservative Party both on details related to the British proposal for separation and on the broader issues involved.

Despite forceful opposition by “hard” Brexiters, a consensus on the nuts and bolts of the government’s Brexit plan appeared to emerge from a marathon meeting of the cabinet in July at Chequers , the prime minister’s country retreat. The working document produced by that meeting committed Britain to “ongoing harmonization” with EU rules and called for the creation of a “joint institutional framework” under which agreements between the U.K. and the EU would be handled in the U.K. by British courts and in the EU by EU courts. Although the proposal mandated that Britain would regain control over how many people could enter the country, it also outlined a “mobility framework” that would permit British and EU citizens to apply for work and for study in each other’s territories. May’s “softer” approach, grounded in policies aimed at preserving economic ties with the EU, looked to have won the day, but in short order the government’s apparent harmony was disrupted by the resignations of Britain’s chief Brexit negotiator, David Davis (who complained that May’s plan gave up too much, too easily), and foreign secretary Johnson, who wrote in his letter of resignation that the dream of Brexit was being “suffocated by needless self-doubt.” Confronted with the possibility of a vote of confidence on her leadership of the Conservative Party, May reportedly warned fellow Tories to back her Brexit plan or risk handing power to a Jeremy Corbyn -led Labour government.

In November the leaders of the EU’s other member countries formally agreed to the terms of a withdrawal deal (the Chequers plan) that May claimed “delivered for the British people” and set the United Kingdom “on course for a prosperous future.” Under the plan Britain was to satisfy its long-term financial obligations by paying some $50 billion to the EU. Britain’s departure from the EU was set for March 29, 2019, but, according to the agreement, the U.K. would continue to abide by EU rules and regulations until at least December 2020 while negotiations continued on the details of the long-term relationship between the EU and the U.K.

The agreement, which was scheduled for debate by the House of Commons in December, still faced strong opposition in Parliament, not only from Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Scottish National Party , Plaid Cymru , and the DUP but also from many Conservatives. Meanwhile, a call for a new referendum on Brexit was gaining traction, but May adamantly refused to consider that option, countering that the British people had already expressed their will. The principal stumbling block for many of the agreement’s opponents was the so-called Northern Ireland backstop plan, which sought to preserve the spirit of the Good Friday Agreement by maintaining an open border between Northern Ireland and EU member Ireland after Brexit. The backstop plan called for a legally binding customs arrangement between the EU and Northern Ireland to go into effect should the U.K. and the EU not reach a long-term agreement by December 2020. Opponents of the backstop were concerned that it created the possibility of effectively establishing a customs border down the Irish Sea by setting up regulatory barriers between Northern Ireland and the rest of the U.K.

The issue came to the fore in the first week of December, when the government was forced to publish in full Attorney General Geoffrey Cox’s legal advice for the government on the Brexit agreement. In Cox’s opinion, without agreement between the U.K. and the EU, the terms of the backstop plan could persist “indefinitely,” leaving Britain legally prevented from ending the agreement absent EU approval. This controversial issue loomed large as the House of Commons undertook five days of debate in advance of a vote on the Brexit agreement scheduled for December 11. With a humiliating rejection of the agreement by the House of Commons likely, on December 10 May chose to dramatically interrupt the debate after three days and postpone the vote, promising to pursue new assurances from the EU regarding the backstop. The opposition responded by threatening to hold a vote of confidence and to call for an early election, but a more immediate threat to May’s version of Brexit came when a hard-line Brexit faction within the Conservative Party forced a vote on her leadership. Needing the votes of 159 MPs to survive as leader, May received 200, and, under Conservative Party rules, she could not be challenged as party leader for another year.

The longer it remained unsettled, the more the matter of Brexit became the defining issue of British politics. With opinions on May’s version of Brexit and on Brexit in general crossing ideological lines, both Labour and the Conservatives were roiling with internecine conflict.

In pursuit of greater support in Parliament for her revised Brexit plan, May secured new promises of cooperation on the backstop plan from EU leaders. Agreement was reached on a “joint legally binding instrument” under which Britain could initiate a “formal dispute” with the EU if the EU were to attempt to keep Britain bound to the backstop plan indefinitely. Another “joint statement” committed the U.K. and the EU to arriving at a replacement for the backstop plan by December 2020. Moreover, a “unilateral declaration” by May’s government stressed that there was nothing to prevent the U.K. from abandoning the backstop should negotiations on an alternative arrangement with the EU collapse without the likelihood of resolution. According to Attorney General Cox, the new assurances reduced the risk of the U.K.’s being indefinitely confined by the backstop agreement, but they did not fundamentally change the agreement’s legal status.

On March 12 the House of Commons again rejected May’s plan (391–242), and the next day it voted 312–308 against a no-deal Brexit—that is, leaving the EU without a deal in place. On March 14 May barely survived a vote that would have robbed her of control of Brexit and given it to Parliament. On March 20 she asked the EU to extend the deadline for Britain’s departure to June 30. The EU responded by delaying the Brexit deadline until May 22 but only if Parliament had accepted May’s withdrawal plan by the week of March 24.

In the meantime, on March 23 hundreds of thousands of demonstrators filled the streets of London demanding that another referendum on Brexit be held. On March 25 the House of Commons voted 329–302 to take control of Parliament’s agenda from the government so as to conduct “indicative votes” on alternative proposals to May’s plan. Eight of those proposals were voted upon on March 27. None of them gained majority support, though a plan that sought to create a “permanent and comprehensive U.K.-wide customs union with the EU” came within six votes of success. That same day May announced that she would resign as party leader and prime minister if the House of Commons were to approve her plan. On March 29 Speaker of the House John Bercow invoked a procedural rule that limited that day’s vote to the withdrawal agreement portion of May’s plan (thus excluding the “political declaration” that addressed the U.K. and EU’s long-term relationship). This time the vote was closer than previous votes had been (286 in support and 344 in opposition), but the plan still went down in defeat.

Time was running out. By April 12 the U.K. had to decide whether it would leave the EU without an agreement on that day or request a longer delay that would require it to participate in elections for the European Parliament . May asked the EU to extend the deadline for Brexit until June 30, and on April 11 the European Council granted the U.K. a “flexible extension” until October 31.

After failing to win sufficient support from Conservatives for her Brexit plan, May entered discussions with Labour leaders on a possible compromise, but these efforts also came up empty. May responded by proposing a new version of the plan that included a temporary customs relationship with the EU and a promise to hold a parliamentary vote on whether another referendum on Brexit should be staged. Her cabinet revolted, and on May 24 May announced that she would step down as party leader on June 7 but would remain as caretaker premier until the Conservatives had chosen her successor.

May’s successor as party leader and prime minister, Boris Johnson , promised to remove the U.K. from the EU without an exit agreement if the deal May had negotiated was not altered to his satisfaction; however, he faced broad opposition (even among Conservatives) to his advocacy of a no-deal Brexit. Johnson’s political maneuvering (including proroguing Parliament just weeks before the revised October 31 departure deadline) was strongly countered by legislative measures advanced by those opposed to leaving the EU without an agreement in place. In early September a vote of the House of Commons forced the new prime minister to request a delay of the British withdrawal from the EU until January 31, 2020, despite the fact that on October 22 the House approved, in principle, the agreement that Johnson had negotiated, which replaced the backstop with the so-called Northern Ireland Protocol , a plan to keep Northern Ireland aligned with the EU for at least four years from the end of the transition period.

In search of a mandate for his vision of Brexit, Johnson tried and failed several times to call a snap election. Because the election would fall outside the five-year term stipulated by the Fixed Terms of Parliament Act, Johnson needed opposition support to achieve the approval of two-thirds of the House of Commons required for the election to be held. Finally, after the possibility of no-deal Brexit was blocked, Labour leader Corbyn agreed to allow British voters once again to decide the fate of Brexit. In the election, held on December 12, 2019, the Conservatives recorded their most decisive victory since 1987, adding 48 seats to secure a solid Parliamentary majority of 365 seats and setting the stage for the realization of a Johnson-style Brexit. At 11:00 pm London time on January 31, the United Kingdom formally withdrew from the European Union. The freedom to work and move freely between the U.K. and the EU became a thing of the past.

Although Britain’s formal departure from the EU was completed, final details relating to a new trade deal between the U.K. and the EU remained to be resolved. On December 24, 2020, the December 31 deadline for that resolution was only barely met. The resultant 2,000-page agreement clarified that there would be no limits or taxes on goods sold between U.K. and EU parties; however, an extensive regimen of paperwork for such transactions and transport of goods was put in place.

In June 2022 Johnson sought to jettison part of the trade agreement , introducing legislation in Parliament that would remove checks on goods entering Northern Ireland from elsewhere in the U.K. The Johnson government averred that overly stringent application of the customs rules by the EU was undermining business and threatening peace in Northern Ireland. Unionists had complained that these customs checks were jeopardizing Northern Ireland’s relationship with the rest of the U.K., and the DUP refused to re-enter Northern Ireland’s power-sharing executive until the checks were eliminated. Opponents of Johnson’s action, including May, argued that the move was illegal, and the EU threatened retaliation.

TED is supported by ads and partners 00:00

Brexit: How, When and What?

- global issues

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

What Is Brexit? And How Is It Going?

Almost a year after it took full effect, the consequences of Britain’s split from the European Union are still unfolding. Here is a guide to what it means, how it came about and what the future may hold.

By Benjamin Mueller and Peter Robins

Britain broke from the European Union’s regulatory orbit on Jan. 1, casting off nearly a half-century inside the bloc and embarking on what analysts described as the biggest overnight change in modern commercial relations between countries.

Far from closing the book on Britain’s tumultuous relationship with the rest of Europe, the split, known as Brexit , has opened a new chapter — one that could reshape not only the country’s economy, foreign policy and politics, but even its borders.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson speaks of creating a more agile “Global Britain,” with stronger ties to the United States and other democracies, like Australia, India and South Korea.

But while that plan has hit setbacks , risks from the new dispensation have quickly become evident, including on empty supermarket shelves as the country struggles with a shortage of truck drivers.

And arrangements for the sensitive territory of Northern Ireland have fueled rioting and diplomatic tensions.

Here’s what you need to know:

- Let’s start with the basics.

- Leaving is a big deal economically.

- Brexit’s supporters say their aim is a ‘Global Britain.’

- In Northern Ireland, Brexit is waking old demons.

- Scotland could make its own split.

- Fishing remains a sore point.

- What’s next?

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Brexit?

The referendum, the article 50 negotiating period, brexit negotiations.

- Arguments for and Against

Brexit Economic Response

June 2017 general election.

- Scotland Referendum

Upsides for Some

U.k.-eu trade after brexit, impact on the u.s., who’s next to leave the eu, the bottom line.

- International Markets

Brexit Meaning and Impact: The Truth About the U.K. Leaving the EU

Adam Hayes, Ph.D., CFA, is a financial writer with 15+ years Wall Street experience as a derivatives trader. Besides his extensive derivative trading expertise, Adam is an expert in economics and behavioral finance. Adam received his master's in economics from The New School for Social Research and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in sociology. He is a CFA charterholder as well as holding FINRA Series 7, 55 & 63 licenses. He currently researches and teaches economic sociology and the social studies of finance at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/adam_hayes-5bfc262a46e0fb005118b414.jpg)

Brexit is a portmanteau of the words “British” and “exit” that was coined to refer to the United Kingdom’s decision in a June 23, 2016, referendum to leave the European Union (EU) . Brexit took place at 11 p.m. Greenwich Mean Time on Jan. 31, 2020.

On Dec. 24, 2020, the U.K. and the EU struck a provisional free-trade agreement ensuring the free trade of goods without tariffs or quotas. However, key details of the future relationship remain uncertain, such as trade in services, which make up 80% of the U.K. economy. This prevented a no-deal Brexit, which would have been significantly damaging to the U.K. economy.

A provisional agreement was approved by the U.K. parliament on Jan. 1, 2021. It was approved by the European Parliament on April 28, 2021. While the deal, known as the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) , allowed tariff- and quota-free trade in goods, U.K.-EU trade still faces customs checks. This means that commerce is not as smooth as when the U.K. was a member of the EU.

Key Takeaways

- Brexit refers to the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union (EU).

- Brexit took place on Jan. 31, 2020, following the June 2016 referendum in the country.

- The Leave side received 51.9% of the vote while the Remain side got 48.1%.

- Negotiations took place between the U.K. and the EU from 2017 to 2019 on the terms of a divorce deal.

- There was a transition period following Brexit that expired on Dec. 31, 2020.

Ellen Lindner / Investopedia

The Leave side won the June 2016 referendum with 51.9% of the ballot, or 17.4 million votes, while Remain received 48.1% or 16.1 million votes. Voter turnout was 72.2%. The results were tallied on a U.K.-wide basis, but the overall figures conceal stark regional differences: 53.4% of English voters supported Brexit, compared to just 38% of Scottish voters.

Because England accounts for the vast majority of the U.K.’s population, support there swayed the result in Brexit’s favor. If the vote were conducted only in Wales (where Leave voters also won), Scotland, and Northern Ireland, Brexit would have received less than 45% of the vote.

The result defied expectations and roiled global markets, causing the British pound to fall to its lowest level against the dollar in 30 years.

Former Prime Minister David Cameron, who called the referendum and campaigned for the U.K. to remain in the EU, announced his resignation the following day. He was replaced as leader of the Conservative Party and prime minister by Theresa May in July 2016.

The process of leaving the EU formally began on March 29, 2017, when May triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. The U.K. initially had two years from that date to negotiate a new relationship with the EU.

Following a snap election on June 8, 2017, May remained the country’s leader. However, the Conservatives lost their outright majority in Parliament and agreed on a deal with the Democratic Unionist Party. This later caused May some difficulty getting her Withdrawal Agreement passed in Parliament.

Talks began on June 19, 2017. Questions swirled around the process, partly because Britain’s constitution is unwritten and because no country had left the EU using Article 50 before. A similar move happened, though, when Algeria left the EU’s predecessor after gaining independence from France in 1962, and Greenland, which was a self-governing territory, left Denmark through a special treaty in 1985.

On Nov. 25, 2018, Britain and the EU agreed on a 599-page Withdrawal Agreement, a Brexit deal that touched upon issues such as citizens’ rights, the divorce bill, and the Irish border. Parliament first voted on this agreement on Jan. 15, 2019. Members of Parliament voted 432 to 202 to reject the agreement, the biggest defeat for a government in the House of Commons in recent history.

May stepped down as party leader on June 7, 2019, after failing three times to get the deal she negotiated with the EU approved by the House of Commons. The following month, Boris Johnson, a former mayor of London, foreign minister, and editor of The Spectator , was elected prime minister.

Johnson, a hardline Brexit supporter, campaigned on a platform to leave the EU by the October deadline “do or die” and said he was prepared to leave the EU without a deal. The U.K. and EU negotiators agreed on a new divorce deal on Oct. 17. The main difference from May’s deal was that the Irish backstop clause was replaced with a new arrangement.

Another historic moment occurred in August 2019, when Johnson requested that the queen suspend Parliament from mid-September until Oct. 14, and she approved. This was seen as a ploy to stop members of Parliament from blocking a chaotic exit, and some even called it a coup of sorts. The U.K. Supreme Court’s 11 judges unanimously deemed the move unlawful on Sept. 24 and reversed it.

The negotiating period also led Britain’s political parties to face their own crises. Lawmakers left both the Conservative and Labour parties in protest. There were allegations of antisemitism in the Labour Party, and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was criticized for his handling of the issue. In September, Johnson expelled 21 MPs for voting to delay Brexit.

The U.K. was expected to leave the EU by Oct. 31, 2019, but Parliament voted to force the government to seek an extension to the deadline and delayed a vote on the new deal.

Johnson then called for a general election. In the Dec. 12 election, the third general election in less than five years, Johnson’s Conservative Party won a huge majority of 365 seats in the House of Commons out of 650 seats. It managed this despite receiving only 43.6% of the vote due to its opponents being fractured between multiple parties.

Britain’s lead negotiator in the talks with Brussels was David Davis. He was a Yorkshire member of Parliament (MP) until July 9, 2018, when he resigned. He was replaced by housing minister Dominic Raab as Brexit secretary. Raab resigned in protest over May’s deal on Nov. 15, 2018. He was replaced by health and social care minister Stephen Barclay the following day.

The EU’s chief negotiator was Michel Barnier, a French politician.

Preparatory talks exposed divisions in the two sides’ approaches to the process. The U.K. wanted to negotiate the terms of its withdrawal alongside the terms of its post-Brexit relationship with Europe, while Brussels wanted to make sufficient progress on divorce terms by October 2017, only then moving on to a trade deal. In a concession that both pro- and anti-Brexit commentators took as a sign of weakness, U.K. negotiators accepted the EU’s sequenced approach.

Citizens’ Rights

One of the most politically thorny issues faced by Brexit negotiators was the rights of EU citizens living in the U.K. and U.K. citizens living in the EU.

The Withdrawal Agreement allowed for the free movement of EU and U.K. citizens until the end of the transition or implementation period. Citizens were allowed to keep their residency rights if they continued to work, had sufficient resources, or were related to someone who did. To upgrade their residence status to permanent, they had to apply to the host nation. The rights of these citizens were revocable if Britain left without ratifying a deal.

“EU net migration, while still adding to the population as a whole, has fallen to a level last seen in 2009. We are also now seeing more EU8 citizens—those from Central and Eastern European countries, for example, Poland—leaving the U.K. than arriving,” said Jay Lindop, director of the Centre for International Migration, in a government quarterly report released in February 2019.

Britain’s government fought over the rights of EU citizens to remain in the U.K. after Brexit, publicly airing domestic divisions over migration. Following the referendum and Cameron’s resignation, May’s government concluded that it had the right under the “royal prerogative” to trigger Article 50 and begin the formal withdrawal process on its own.

The U.K. Supreme Court intervened, ruling that Parliament had to authorize the measure, and the House of Lords amended the resulting bill to guarantee the rights of EU-born residents. The House of Commons, which had a Tory majority at the time, struck the amendment down, and the unamended bill became law on March 16, 2017.

Conservative opponents of the amendment argued that unilateral guarantees eroded Britain’s negotiating position, while those in favor of it said EU citizens should not be used as bargaining chips.

Some of the economic concerns included the fact that EU migrants were greater contributors to the economy than their U.K. counterparts. Leave supporters, though, read the data as pointing to foreign competition for scarce jobs in Britain.

Brexit Financial Settlement

The Brexit bill was the financial settlement that the U.K. owed Brussels following its withdrawal.

The Withdrawal Agreement didn’t mention a specific figure, but it was estimated to be up to £32.8 billion, according to Downing Street. The total sum included the financial contribution that the U.K. would make during the transition period because it was an EU member state and owed a contribution toward the EU’s outstanding 2020 budget commitments.

The U.K. also received funding from EU programs during the transition period and a share of its assets at the end of it, which included the capital it paid to the European Investment Bank (EIB) .

A December 2017 agreement resolved this long-standing sticking point that threatened to derail negotiations entirely. Barnier’s team launched the first volley in May 2017 with the release of a document listing the 70-odd entities it would take into account when tabulating the bill. The initial estimate of the bill was €100 billion. Net of certain U.K. assets, the final bill would be €25 billion to €65 billion.”

Davis’ team, meanwhile, refused EU demands to submit the U.K.’s preferred methodology for tallying the bill. In August, he told the BBC he would not commit to a figure by October, the deadline for assessing “sufficient progress” on issues such as the bill.

The following month, he told the House of Commons that Brexit bill negotiations could go on “for the full duration of the negotiation.”

Davis presented this refusal to the House of Lords as a negotiating tactic, but domestic politics probably explained his reticence. Johnson, who campaigned for Brexit, called EU estimates “extortionate” on July 11, 2017, and agreed with a Tory MP that Brussels could “go whistle” if they wanted “a penny.”

In her September 2017 speech in Florence, Italy, however, May said the U.K. would “honor commitments we have made during the period of our membership.” Barnier confirmed to reporters in October 2019 that Britain would pay what was owed.

The Northern Irish Border

The new Withdrawal Agreement replaced the controversial Irish backstop provision with a protocol. According to the revised deal, the entire U.K. left the EU customs union upon Brexit, but Northern Ireland continued following EU regulations and value-added tax (VAT) laws for goods, while the U.K. government collected the VAT on behalf of the EU.

This meant there was a limited customs border in the Irish Sea with checks at major ports. The Northern Ireland assembly can vote on this arrangement up to four years after the end of the transition period.

The backstop emerged as the main reason for the Brexit impasse. It was a guarantee that there was no “hard border” between Northern Ireland and Ireland. It was an insurance policy that kept Britain in the EU customs union with Northern Ireland following EU single-market rules.

The backstop, which was meant to be temporary and was superseded by a subsequent agreement, could only be removed if both Britain and the EU gave their consent.

May was unable to garner enough support for her deal due to it. Euroskeptic MPs wanted her to add legally binding changes, as they feared it would compromise the country’s autonomy and could last indefinitely. EU leaders refused to remove it and ruled out a time limit on granting Britain the power to remove it. On March 11, 2019, the two sides signed a pact in Strasbourg, France, that did not change the Withdrawal Agreement but added “meaningful legal assurances.” But it wasn’t enough to convince hardline Brexiteers.

For decades during the second half of the 20th century, violence between Protestants and Catholics marred Northern Ireland and the border between the U.K. countryside and the Republic of Ireland to the south was militarized. The 1998 Good Friday Agreement turned the border almost invisible, except for speed limit signs, which switch from miles per hour in the north to kilometers per hour in the south.

Negotiators in the U.K. and EU worried about the consequences of reinstating border controls, as Britain had to do in order to end freedom of movement from the EU. Yet leaving the customs union without imposing customs checks at the Northern Irish border or between Northern Ireland and the rest of Britain left the door wide open for smuggling . This significant and unique challenge was one of the reasons soft Brexit advocates cited in favor of staying in the EU’s customs union and perhaps its single market.

The issue was further complicated by the Tories’ choice of the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party as a coalition partner. The party opposed the Good Friday Agreement and, unlike the Conservative leader at the time, campaigned for Brexit.

Under the Good Friday Agreement, the U.K. government was required to oversee Northern Ireland with “rigorous impartiality.” That proved difficult for a government that depended on the cooperation of a party with an overwhelmingly Protestant support base and historical connections to Protestant paramilitary groups.

Arguments for and Against Brexit

Leave voters based their support for Brexit on a variety of factors, including the European debt crisis , immigration, terrorism, and the perceived drag of Brussels’ bureaucracy on the U.K. economy.

Britain was wary of the European Union’s projects, which Leave supporters felt threatened the U.K.’s sovereignty; the country never opted into the European Union’s monetary union, meaning that it used the pound instead of the euro . It also remained outside the Schengen Area, meaning that it did not share open borders with a number of other European nations.

Opponents of Brexit also cited a number of rationales for their position:

- The risk involved in pulling out of the EU’s decision-making process, given that it was the largest destination for U.K. exports

- The economic and societal benefits of the EU’s four freedoms: the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people across borders

A common thread in both arguments was that leaving the EU would destabilize the U.K. economy in the short term and make the country poorer in the long term.

In July 2018, May’s cabinet suffered another shake-up when Boris Johnson resigned as the U.K.’s foreign minister and David Davis resigned as Brexit minister over May’s plans to keep close ties to the EU. Johnson was replaced by Jeremy Hunt, who favored a soft Brexit.

Some state institutions backed the Remain supporters’ economic arguments: Bank of England governor Mark Carney called Brexit “the biggest domestic risk to financial stability” in March 2016, and the following month, the Treasury projected lasting damage to the economy under any of three possible post-Brexit scenarios:

- European Economic Area (EEA) membership

- A negotiated bilateral trade deal

- World Trade Organization (WTO) membership

| The annual impact of leaving the EU on the U.K. after 15 years (difference from being in the EU) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| -3.8% | -6.2% | -7.5% | |

| -3.4% to -4.3% | -4.6% to -7.8% | -5.4% to -9.5% | |

| -£1,100 | -£1,800 | -£2,100 | |

| -£1,000 to -£1,200 | -£1,300 to -£2,200 | -£1,500 to -£2,700 | |

| -£2,600 | -£4,300 | -£5,200 | |

| -£2,400 to -£2,900 | -£3,200 to -£5,400 | -£3,700 to -£6,600 | |

| -£20 billion | -£36 billion | -£45 billion | |

Adapted from “H.M. Treasury analysis: The long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives,” April 2016

Leave supporters discounted such economic projections under the label “Project Fear.” A pro-Brexit outfit associated with the U.K. Independence Party (UKIP), which was founded to oppose EU membership, responded by saying that the Treasury’s “worst-case scenario of £4,300 per household is a bargain-basement price for the restoration of national independence and safe, secure borders.”

Although Leave supporters stressed issues of national pride, safety, and sovereignty, they also mustered economic arguments. For example, Johnson said on the eve of the vote, “EU politicians would be banging down the door for a trade deal ” the day after the vote, in light of their “commercial interests.”

Vote Leave, the official pro-Brexit campaign, topped the “Why Vote Leave” page on its website with the claim that the U.K. could save £350 million per week: “We can spend our money on our priorities like the NHS [National Health Service], schools, and housing.”

In May 2016, the U.K. Statistics Authority, an independent public body, said the figure was gross rather than net, which was “misleading and undermines trust in official statistics.” A mid-June poll by Ipsos MORI, however, found that 47% of the country believed the claim.

The day after the referendum, Nigel Farage, who co-founded UKIP and led it until that November, disavowed the figure and said that he was not closely associated with Vote Leave. May also declined to confirm Vote Leave’s NHS promises since taking office.

Though Britain officially left the EU, 2020 was a transition and implementation period. Trade and customs continued during that time, so there wasn’t much on a day-to-day basis that seemed different to U.K. residents. Even so, the decision to leave the EU had an effect on Britain’s economy.

The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth slowed down to around 1.4% in 2018 from 1.9% in 2016 and 2.7% in 2017 as business investment slumped. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted that the country’s economy would grow at 1.3% in 2019 and 1.4% in 2020. Instead, growth was 1.6% in 2019 but -10.4% in 2020. GDP rebounded, however, touching 8.7% in 2021 before slowing to 4.3% in 2022.

The U.K. unemployment rate hit a 44-year low at 3.9% in the three months leading up to January 2019. Experts attribute this to employers preferring to retain workers instead of investing in new major projects.

While the fall in the value of the pound after the Brexit vote helped exporters, the higher price of imports was passed onto consumers and had a significant impact on the annual inflation rate. Consumer Prices Index (CPI) inflation hit 3.1% in the 12 months leading up to November 2017, a nearly six-year high that well exceeded the Bank of England’s 2% target. Inflation fell in 2018 with the decline in oil and gas prices but soared after the global COVID-19 pandemic, rising 8.7% in the 12 months preceding April 2023.

A July 2017 report by the House of Lords cited evidence that U.K. businesses would have to raise wages to attract native-born workers following Brexit, which was “likely to lead to higher prices for consumers.”

International trade was expected to fall due to Brexit, even with the possibility of a raft of free trade deals. Dr. Monique Ebell, former associate research director at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, forecasted a -22% reduction in total U.K. goods and services trade if EU membership was replaced by a free trade agreement.

Other free trade agreements were not predicted to pick up the slack. In fact, Ebell saw a pact with the BRIICS (Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China, and South Africa) boosting total trade by 2.2% while a pact with the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand was expected to do slightly better, at 2.6%.

“The single market is a very deep and comprehensive trade agreement aimed at reducing non-tariff barriers,” Ebell wrote in January 2017, “while most non-EU [free trade agreements] seem to be quite ineffective at reducing the non-tariff barriers that are important for services trade.”

On April 18, May called for a snap election to be held on June 8, despite previous promises not to hold one until 2020. Polling at the time suggested May would expand on her slim Parliament majority of 330 seats (there are 650 seats in the Commons). Labour gained rapidly in the polls, however, aided by an embarrassing Tory flip-flop on a proposal for estates to fund end-of-life care.

The Conservatives lost their majority, winning 318 seats to Labour’s 262. The Scottish National Party won 35, with other parties taking 35. The resulting hung Parliament cast doubts on May’s mandate to negotiate Brexit and led the leaders of Labour and the Liberal Democrats to call on May to resign.

Speaking in front of the prime minister’s residence at 10 Downing Street, May batted away calls for her to leave her post, saying, “It is clear that only the Conservative and Unionist Party”—the Tories’ official name—“has the legitimacy and ability to provide that certainty by commanding a majority in the House of Commons.” The Conservatives struck a deal with the Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland, which won 10 seats, to form a coalition.

May presented the election as a chance for the Conservatives to solidify their mandate and strengthen their negotiating position with Brussels. But this backfired.

In the wake of the election, many expected the government’s Brexit position to soften, and they were right. May released a Brexit white paper in July 2018 that mentioned an “association agreement” and a free-trade area for goods with the EU. David Davis resigned as Brexit secretary, and Boris Johnson resigned as Foreign Secretary in protest.

But the election also increased the possibility of a no-deal Brexit. The Financial Times predicted that the result made May more vulnerable to pressure from Euroskeptics and her coalition partners. This was evident with the Irish backstop tussle.

With her position weakened, May struggled to unite her party behind her deal and keep control of Brexit.

Scotland’s Independence Referendum

Politicians in Scotland pushed for a second independence referendum in the wake of the Brexit vote, but the results of the June 8, 2017, election cast a pall over their efforts. The Scottish National Party (SNP) lost 21 seats in the Westminster Parliament, and on June 27, 2017, Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said her government at Holyrood would “reset” its timetable on independence to focus on delivering a “soft Brexit.”

Not one Scottish local area voted to leave the EU, according to the U.K.’s Electoral Commission, though Moray came close at 49.9%. The country as a whole rejected the referendum by 62.0% to 38.0%.

But because Scotland only contains 8.4% of the U.K.’s population, its vote to Remain (along with that of Northern Ireland, which accounts for just 2.8% of the U.K.’s population) was vastly outweighed by support for Brexit in England and Wales.

Scotland joined England and Wales to form Great Britain in 1707, and the relationship has been tumultuous at times. The SNP, which was founded in the 1930s, had just six of 650 seats in Westminster in 2010. The following year, however, it formed a majority government in the devolved Scottish Parliament at Holyrood, partly owing to its promise to hold a referendum on Scottish independence.

2014 Scottish Independence Referendum

That referendum, held in 2014, saw the pro-independence side lose with 44.7% of the vote. Turnout was 84.6%. Far from putting the independence issue to rest, though, the vote fired up nationalist support.

The SNP won 56 of 59 Scottish seats at Westminster the following year, overtaking the Liberal Democrats to become the third-largest party in the U.K. overall. Britain’s electoral map suddenly showed a glaring divide between England and Wales, which was dominated by Tory blue with the occasional patch of Labour red, and all-yellow Scotland.

When Britain voted to leave the EU, Scotland fulminated. A combination of rising nationalism and strong support for Europe led almost immediately to calls for a new independence referendum. In 2017, when the Supreme Court ruled that devolved national assemblies such as Scotland’s parliament could not veto Brexit, the demands grew louder.

On March 13 of that year, Sturgeon called for a second referendum to be held in the autumn of 2018 or spring of 2019. Holyrood backed her by a vote of 69 to 59 on March 28, the day before May’s government triggered Article 50.

Sturgeon’s preferred timing was significant since the two-year countdown initiated by Article 50 ended in the spring of 2019 when the politics surrounding Brexit could be particularly volatile.

What Would Independence Look Like?

Scotland’s economic situation also raised questions about its hypothetical future as an independent country. The crash in oil prices dealt a blow to government finances. In May 2014, its government forecasted 2015–2016 tax receipts from North Sea drilling of £3.4 billion to £9 billion but only collected £60 million, less than 1% of the forecasts’ midpoint.

In reality, these figures were hypothetical since Scotland’s finances were not (and are not) fully devolved, but the estimates were based on the country’s geographical share of North Sea drilling, so they illustrated what it might expect as an independent nation.

The debate over what currency an independent Scotland would use was revived. Former SNP leader Alex Salmond, who was Scotland’s First Minister until November 2014, told the Financial Times that the country could abandon the pound and introduce its own currency, allowing it to float freely or pegging it to sterling. He ruled out joining the euro, but others contended that it would be required for Scotland to join the EU. Another possibility would be to use the pound, which would mean forfeiting control over monetary policy .

On the other hand, a weak currency that floats on global markets can be a boon to U.K. producers that export goods. Industries that rely heavily on exports could actually see some benefit.

In 2024, the top 10 exports from the U.K. were (in U.S. dollars):

- Precious metals: $63.5 billion

- Motor vehicle manufacturing: $28.8

- Aircraft, engines, and parts manufacturing: $27.4 billion

- Petroleum refining: $21.4 billion

- Pharmaceuticals preparations manufacturing: $15.4 billion

- Crude petroleum and natural gas extraction: $12.8 billion

- Off-road vehicle manufacturing: $8.9 billion

- Measuring, testing, and navigational equipment manufacturing: $8.4 billion

- Spirit Production: $6.9 billion

- Whiskey production: $5.8 billion

Some sectors were prepared to benefit from the exit. Multinationals listed on the FTSE 100 saw earnings rise as a result of a soft pound. A weak currency was also a boon to the tourism, energy, and service industries.

In May 2016, the State Bank of India, India’s largest commercial bank, suggested that Brexit would benefit India economically. While leaving the eurozone meant that the U.K. no longer had unfettered access to Europe’s single market, it would allow for more focus on trade with India. India would also have more wiggle room if the U.K. were no longer under European trade rules and regulations.

May advocated a “hard Brexit.” By that, she meant that Britain should leave the EU’s single market and customs union and negotiate a trade deal to govern their future relationship. These negotiations would have been conducted during a transition period once a divorce deal was ratified.

The Conservatives’ poor showing in the June 2017 snap election called popular support for a hard Brexit into question. Many in the press speculated that the government could take a softer line. The Brexit White Paper released in July 2018 revealed plans for a softer Brexit. It was too soft for many MPs in her party and too audacious for the EU.

The white paper said the government planned to leave the EU single market and customs union. However, it proposed the creation of a free trade area for goods, which would “avoid the need for customs and regulatory checks at the border and mean that businesses would not need to complete costly customs declarations. And it would enable products to only undergo one set of approvals and authorizations in either market, before being sold in both.” This meant the U.K. would follow EU single-market rules regarding goods.

The white paper acknowledged that a borderless customs arrangement with the EU—one that allowed the U.K. to negotiate free trade agreements with third countries—was “broader in scope than any other that exists between the EU and a third country.”

The government was correct that there was no example of this kind of relationship in Europe. The four broad precedents that existed were the EU’s relationship with Norway, Switzerland, Canada, and WTO members.

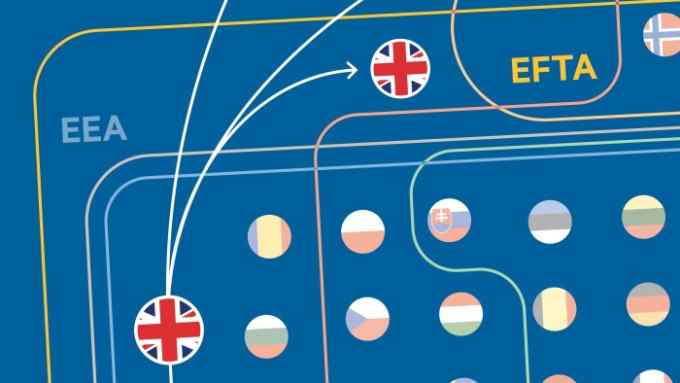

The Norway Model: Join the EEA

The first option was for the U.K. to join Norway, Iceland, and Lichtenstein in the European Economic Area (EEA) , which provides access to the EU’s single market for most goods and services (agriculture and fisheries are excluded). At the same time, the EEA is outside the customs union, so Britain could have entered into trade deals with non-EU countries.

But the arrangement was hardly a win-win. The U.K. would be bound by some EU laws while losing its ability to influence those laws through the country’s European Council and European Parliament voting rights. In September 2017, May called this arrangement an unacceptable “loss of democratic control.”

David Davis expressed interest in the Norway model in response to a question he received at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Washington. “It’s something we’ve thought about, but it’s not at the top of our list,” he said. He was referring specifically to the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which, like the EEA, offers access to the single market but not the customs union.

The EFTA was once a large organization, but most of its members left to join the EU. Today, it comprises Norway, Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Switzerland; all but Switzerland are also members of the EEA.

The Switzerland Model

Switzerland’s relationship with the EU, which is governed by around 20 major bilateral pacts with the bloc, is broadly similar to the EEA arrangement. Along with these three, Switzerland is a member of the European Free Trade Association. Switzerland helped set up the EEA, but its people rejected membership in a 1992 referendum.

The country allows the free movement of people and is a member of the passport-free Schengen Area. It is subject to many single-market rules without having much say in making them.

It is outside the customs union, allowing it to negotiate free trade agreements with third countries; usually, but not always, it has negotiated alongside the EEA countries. Switzerland has access to the single market for goods (with the exception of agriculture) but not services (except insurance). It pays a modest amount into the EU’s budget.

Brexit supporters who wanted to “take back control” wouldn’t have embraced the concessions that the Swiss made on immigration, budget payments, and single-market rules. The EU would probably not have wanted a relationship modeled on the Swiss example, either: Switzerland’s membership in the EFTA but not the EEA, and Schengen but not the EU, is a messy product of the complex history of European integration and—not surprisingly—a referendum.

The Canada Model: A Free Trade Agreement

A third option was to negotiate a free trade agreement with the EU along the lines of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), a pact that the EU finalized but didn’t fully ratify with Canada. The most obvious problem with this approach is that the U.K. had only two years from triggering Article 50 to negotiate such a deal. The EU refused to discuss a future trading relationship until December of that year at the earliest.

To give a sense of how tight that timetable was, CETA negotiations began in 2009 and concluded in 2014. But just over half of the EU’s 28 national parliaments ratified the deal. Even subnational legislatures can stand in the way of a deal; the Walloon regional parliament, which represents fewer than four million mainly French-speaking Belgians, single-handedly blocked CETA for a few days in 2016.

To extend the two-year deadline for leaving the EU, Britain needed unanimous approval from the EU. Several U.K. politicians, including Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, stressed the need for a transitional deal of a few years so that (among other reasons) Britain could negotiate EU and third-country trade deals. But this notion was met with resistance from hardline Brexiteers.

As of 2024, all EU member countries have signed the agreement yet some still need to ratify it, a process that can take two to five years.

Problems With a CETA-Style Agreement

In some ways, comparing Britain’s situation to Canada’s is misleading. Canada already enjoys free trade with the U.S. through the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which was built on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) . This means that a trade deal with the EU was not as crucial as it is for the U.K. Canada’s and Britain’s economies are also very different—CETA does not include financial services, one of Britain’s biggest exports to the EU.

Speaking in Florence, Italy, in September 2017, May said the U.K. and EU “can do so much better” than a CETA-style trade agreement since they were beginning from the “unprecedented position” of sharing a body of rules and regulations. She did not elaborate on what “much better” looked like besides calling on both parties to be “creative as well as practical.”

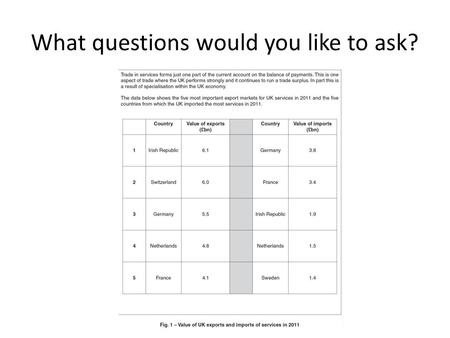

Monique Ebell, formerly of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, stressed that even with an agreement in place, non-tariff barriers were likely to be a significant drag on Britain’s trade with the EU. She expected total U.K. foreign trade—not just flows to and from the EU—under an EU-U.K. trade pact. She reasoned that free trade deals did not generally handle services trade well. Services are a major component of Britain’s international trade; the country enjoys a trade surplus in that segment, which is not the case for goods.

Free trade deals also struggle to rein in non- tariff barriers. Admittedly, Britain and the EU started from a unified regulatory scheme, but divergences would only multiply post-Brexit.

WTO: Go It Alone

If Britain and the EU weren’t able to agree their relationship, they would have had to revert to WTO terms. But this default solution wouldn’t have been straightforward, either. Since Britain was a WTO member through the EU, it would have to split tariff schedules with the bloc and divvy out liabilities arising from ongoing trade disputes.

Trading with the EU on WTO terms was the “no-deal” scenario that the Conservative government presented as an acceptable fallback, though most observers see this as a negotiating tactic. In July 2017, U.K. Secretary of State for International Trade Liam Fox said, “People talk about the WTO as if it would be the end of the world. But they forget that is how they currently trade with the United States, with China, with Japan, with India, with the Gulf, and our trading relationship is strong and healthy.”

But for certain industries, the EU’s external tariff would have hit hard: Britain exports 77% of the cars it manufactures, and 58% of these go to Europe. The EU levies 10% tariffs on imported cars. Monique Ebell of the NIESR estimated that leaving the EU single market would reduce overall U.K. goods and services trade—not just that with the EU—by 22% to 30%.

Nor would the U.K. only be giving up its trade arrangements with the EU; under any of the scenarios above, it would probably have lost the trade agreements that the bloc struck with 63 developing countries, as well as progress in negotiating other deals. Replacing these and adding new ones would have been an uncertain prospect. In a September 2017 interview with Politico, Fox said his trade office, which was formed in July 2016, turned away some developing countries looking to negotiate free trade deals because it lacked the capacity to negotiate.

Fox wanted to roll the terms of existing EU trade deals over into new agreements, but some countries were unwilling to give Britain (66 million people, $2.6 trillion GDP) the same terms as the EU (excluding Britain, around 440 million people, $13.9 trillion GDP).

Companies in the U.S. across a wide variety of sectors have made large investments in the U.K. over many years. The U.S. hires a lot of Brits, making U.S. companies one of the U.K.’s largest job markets. The output of U.S. affiliates in the United Kingdom was $129.3 billion in 2021.

The United Kingdom plays a vital role in corporate America’s global infrastructure, from assets under management (AUM) to international sales and research and development (R&D) advancements.

American companies have viewed Britain as a strategic gateway to other countries in the European Union. Brexit is believed to jeopardize the affiliate earnings and stock prices of many companies strategically aligned with the United Kingdom.

American companies and investors that have exposure to European banks and credit markets may be affected by credit risk. European banks may have to replace $123 billion in securities depending on how the exit unfolds. Furthermore, U.K. debt may not be included in European banks’ emergency cash reserves , creating liquidity problems. European asset-backed securities have been in decline since 2007.

Political wrangling over the EU wasn’t limited to Britain. Even following Britain’s departure, most EU members had strong Euroskeptic movements that, while they struggled to win power at the national level, heavily influenced the tenor of national politics in the years that followed. There is still a chance that such movements could secure referendums on EU membership in a few countries at some point in the future.

In May 2016, global research firm Ipsos released a report showing that a majority of respondents in Italy and France believe their countries should hold a referendum on EU membership.

The fragile Italian banking sector has driven a wedge between the EU and the Italian government, which provided bailout funds to save mom-and-pop bondholders from being “bailed in,” as EU rules stipulate. The government abandoned its 2019 budget when the EU threatened it with sanctions. It lowered its planned budget deficit from 2.5% of GDP to 2.04%.

Matteo Salvini, the far-right head of Italy’s Northern League and the country’s deputy prime minister, called for a referendum on EU membership hours after the Brexit vote, saying, “This vote was a slap in the face for all those who say that Europe is their own business and Italians don’t have to meddle with that.”

The Northern League has an ally in the populist Five Star Movement, whose founder, former comedian Beppe Grillo, called for a referendum on Italy’s membership in the euro—though not the EU. The two parties formed a coalition government in 2018 and made Giuseppe Conte prime minister. Conte ruled out the possibility of “Italexit” in 2018 during the budget standoff.

Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s Euroskeptic National Front, hailed the Brexit vote as a win for nationalism and sovereignty across Europe: “Like a lot of French people, I’m very happy that the U.K. people held on and made the right choice. What we thought was impossible yesterday has now become possible.” She lost the French presidential election to Emmanuel Macron in May 2017, gaining just 33.9% of votes. He won the election again in 2022, beating Le Pen once more.

Macron has warned that the demand for “Frexit” will grow if the EU does not see reforms. According to a 2020–2022 European Social Survey poll, 16% of French citizens want the country to leave the EU, down from 24.3% in a 2016–2017 poll.

When Did Britain Officially Leave the European Union?

Britain officially left the EU on Jan. 31, 2020, at 11 p.m. GMT. The move came after a referendum voted in favor of Brexit on June 23, 2016.

What Were the Reasons Behind Brexit?

There were many reasons why Britain voted to leave the European Union. But some of the main issues behind Brexit included a rise in nationalism, immigration, political autonomy, and the economy. The Leave side garnered almost 52% of the votes, while the Remain side received about 48%.

How Many Countries Are Part of the EU Post-Brexit?

Britain’s departure from the European Union left 27 member states. They are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.

The European Union was established in November 1993 with the Maastricht Treaty. The original members included Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Fifteen other countries would gain membership in the union.

Rising nationalist sentiment, coupled with concerns over the economy and British sovereignty, led the majority of voters in the U.K. to vote to leave the EU. Britain left the union at the end of January 2020 in what is commonly called Brexit. But the move didn’t come without challenges. It required two years of negotiating a deal and a year-long transition period before everything became final.

BBC. “ Brexit: What Is the Transition Period? ”

The New York Times. “ Brexit Trade Deal Gets a Final OK from E.U. Parliament .”

The New York Times. “ Britain Gets a Boost with a Brexit Trade Deal, but Challenges Loom .”

The New York Times. “ E.U. Referendum: After the ‘Brexit’ Vote .”

BBC. “ EU Referendum Results .”

Financial Times. " Pound Tumblers to 30-year Low as Britain Votes Brexit ."

CNN. “ Theresa May Becomes New British Prime Minister .”

Gov.UK. “ Prime Minister’s Letter to Donald Tusk Triggering Article 50 .”

BBC. " Election 2017: The Result in Maps and Charts ."

BBC. " Conservatives Agree Pact With DUP to Support May Government ."

Library of Congress, Research Guides. “ BREXIT: Sources of Information .”

Gov.UK. “ Withdrawal Agreement and Political Declaration .”

U.K. Parliament. “ Government Loses ‘Meaningful Vote’ in the Commons .”

Gov.UK. “ Prime Minister’s Statement in Downing Street: 24 May 2019 .”

U.K. Parliament. “ A No-Deal Brexit: The Johnson Government .”

The Guardian. " Johnson's Suspension of Parliament Unlawful, Supreme Court Rules ."

NPR. " Queen Will Suspend U.K. Parliament at Boris Johnson's Request ."

BBC. " General Election 2019: Tories Probe Candidates Over Anti-Semitism Claims ."

BBC. " Brexit Showdown: Who Were Tory Rebels Who Defied Boris Johnson? "

European Union, via Internet Archive Wayback Machine. “ Brexit .”

BBC. “ U.K. Results: Conservatives Win Majority .”

Gov.UK. “ Agreement on the Withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, as Endorsed by Leaders at a Special Meeting of the European Council on 25 November 2018 ,” Pages 20 and 28 (Pages 22 and 30 of PDF).

U.K. Office for National Statistics. “ Migration Statistics Quarterly Report: February 2019 .”

Centre for Economic Performance. “ Brexit and the Impact of Immigration on the U.K. ”

U.K. Office for Budget Responsibility. “ Fiscal Risks Report ,” Page 166 (Page 172 of PDF).

CNN. " U.K. Says It Won't Pay €100 Billion Brexit Divorce Bill ."

European Commission. “ Essential Principles on Financial Settlement ,” Pages 6–8.

Politico. “ Britain Will Not Commit to Brexit Bill Figure by October, Says David Davis .”

U.K. Parliament, House of Hansard Commons. “ EU Exit Negotiations .”

U.K. Parliament, House of Hansard Commons. “ Oral Answers to Questions .”

Gov.UK. “ PM’s Florence Speech: A New Era of Cooperation and Partnership Between the U.K. and the EU .”

European Commission. “ Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland .”

European Commission. “ Remarks by President Jean-Claude Juncker at Today’s Joint Press Conference with U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May .”

Gov.UK. “ The Belfast Agreement: An Agreement Reached on the Multi-Party Talks at Northern Ireland ,” Page 4 (Page 8 of PDF).

UK Parliament. " The ERM and the Single Currency ."

CNN. " Boris Johnson's Letter of Resignation: 'The Brexit Dream is Dying' ."

U.K. Parliament. “ The Short-Term Effects of Leaving the EU .”

H.M. Government. “ H.M. Treasury Analysis: The Long-Term Economic Impact of EU Membership and the Alternatives ,” Page 6.

H.M. Government. “ H.M. Treasury Analysis: The Long-term Economic Impact of EU Membership and the Alternatives ,” Page 8.

The Guardian. “ George Osborne: Brexit Would Force Income Tax Up by 8p in Pound .”

The Financial Times. “ EU ‘Foolish’ to Erect Trade Barriers Against Britain .”

Vote Leave. “ Why Vote Leave .”

U.K. Statistics Authority, via Internet Archive Wayback Machine. “ UK Statistics Authority Statement on the Use of Official Statistics on Contributions to the European Union .”

Ipsos MORI. “ Ipsos MORI June 2016 Political Monitor ,” Page 6.

ITV. “ Nigel Farage Labels £350m NHS Promise ‘a Mistake’ .”

International Monetary Fund. “ World Economic Outlook, July 2019 .”

U.K. Office for National Statistics. “ Gross Domestic Product: Year on Year Growth: CVM SA % .”

U.K. Office for National Statistics. “ Labour Market Economic Commentary: March 2019 .”

U.K. Office for National Statistics. “ Consumer Price Inflation, U.K.: November 2018 .”

U.K. Office for National Statistics. “ Consumer Price Inflation, U.K.: April 2023 .”

U.K. Parliament. “ Chapter 3: Adapting the U.K. Labour Market .”

Economic and Social Research Council. “ Will New Trade Deals Soften the Blow of Hard Brexit? ”

BBC. “ Election 2017 Results .”

Gov.UK. “ PM Statement: General Election 2017 .”

Gov.UK. “ The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union ,” Page 15 (Page 19 of PDF).

Financial Times. “ How the Election Result Affects Brexit .”

Politico. “ Nicola Sturgeon ‘Resets’ Timetable on Independence Referendum .”

The Electoral Commission. “ Results and Turnout at the EU Referendum .”

The Electoral Commission. “ Report: Scottish Independence Referendum .”

Financial Times. “ Scotland Could Abandon Currency Union with U.K., Says Alex Salmond .”

IBISWorld. “ Biggest Exporting Industries in the U.K. in 2024 .”

Business Today. " Brexit to Offer Better Market Access to India: SBI Chief ."

Gov.UK. “ The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union ,” Page 3 (Page 7 of PDF).

Gov.UK. “ The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union ,” Pages 7 and 11 (Pages 11 and 15 of PDF).

Gov.UK. “ The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union ,” Pages 11–12 (Pages 15–16 of PDF).

Politico. “ David Davis: Norway Model Is One Option for U.K. After Brexit .”

Politico. " Walloon Parliament Rejects CETA Deal ."

Financial Times. " Philip Hammond on Brexit, Austerity and Being 'Deeply Unpopular .'"

Carleton. " CETA Ratification Process ."

Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. " Frequently Asked Questions About CETA, the EU-Canada Economic and Trade Agreement ." Select 'What Are the Next Steps?'

Reuters. “ Brexit on WTO Terms Would Not Be the End of the World: Fox .”

Statista. " Distribution of cars exported from the United Kingdom (UK) in 2022, by main export destinations ."

Gardner. " Car Production in U.K. Hits 9-Year High ."

Politico. “ Liam Fox: Britain Does Not Have Capacity to Strike Trade Deals Now .”

International Trade Administration. “ Market Overview .”

European Securities and Markets Authority. " ESMA TRV Risk Analysis: The EU Securitisation Market - An Overview ," Page 3

OANDA. "' Brexit' Risks Leaving European Banks With $123 Billion to Cover. "

Ipsos. “ Ipsos Brexit Poll: May 2016 ,” Page 8.

European Commission. “ Commission Concludes That an Excessive Deficit Procedure Is No Longer Warranted for Italy at This Stage .”

The Wall Street Journal. “ Who Else Wants to Break Up With the EU ?”

Politico. " Beppe Grillo Sets His Sights on the Euro ."

Quartz. “ ‘This Is a Blow to Europe’: Leaders in the EU React to Brexit .”

The Guardian. “ French Presidential Election May 2017—Full Second Round Results and Analysis .”

NPR. “ French President Emmanuel Macron Beats His Far-Right Rival to Win Reelection .”

The Guardian. “ Support for Leaving EU Has Fallen Significantly Across Bloc Since Brexit .”

European Union. “ Country Profiles .”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/one-child-policy.asp-FINAL-84e37fd934684a748c4784cc6cd04d77.png)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

- Currently reading: Hard or soft Brexit? The six scenarios for Britain

- Video: Brexit — let’s count the ways

- The road to Brexit: Britain’s destiny at stake

- How Brexit will affect sectors of the UK economy

- The UK economy since the Brexit vote — in 4 charts

- How voters’ perceptions of Brexit remain polarised

Hard or soft Brexit? The six scenarios for Britain

- Hard or soft Brexit? The six scenarios for Britain on x (opens in a new window)

- Hard or soft Brexit? The six scenarios for Britain on facebook (opens in a new window)

- Hard or soft Brexit? The six scenarios for Britain on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- Hard or soft Brexit? The six scenarios for Britain on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Chris Giles and Alex Barker

Just a few weeks ago, Britain’s road to Brexit seemed relatively clear.

Britain’s Conservative government had made its choice, with Theresa May, prime minister, announcing that the country would leave both the EU single market and the bloc’s common market, to end the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice and give the UK scope to strike trade deals of its own.

But an election designed to bolster Mrs May’s mandate for Brexit proved a political disaster, eviscerating her authority and majority. Fundamental elements of her exit plan have come under increasing question.

Here the Financial Times outlines the paths available to the UK. It looks at six scenarios, ranging from a highly disruptive exit without agreement to a smoother path that sacrifices control in order to remain enmeshed in the EU’s single market. Each confronts the UK with a choice between political independence, economic performance, and the speed of change.

The default scenario if there is no divorce agreement. The UK would no longer be bound by the EU treaties and there would be nothing to replace the thousands of international agreements that stem from them.

Winners This could be hailed by purists as a “clean” Brexit . A fully sovereign Britain would be able to strike agreements with anyone unencumbered by its complex and evolving relationship with the EU. From this position, Britain could negotiate new relationships with the EU and other countries based on mutual advantage.

Losers Disruption on a scale rarely seen in peacetime affecting almost every business in Britain. The lack of customs facilitation deals would disrupt trade at borders, air traffic would be hit by a lack of regulatory approval to fly to the EU, British lorry drivers would not be licensed to drive their vehicles in the EU. The transportation of nuclear material to Britain would cease. Tariffs on goods would be imposed at tight border controls. Food imports would be a problem.

A hard border in Ireland would spring up overnight. Any areas in which the UK had not legislated for a replacement regulatory agency would be left hanging. The residence of EU citizens in the UK and British citizens in the EU would be left to the mercy of their host country governments. The EU would also lose out because of the disruption to trade and the hole in the bloc’s current budget that would be opened up by a failure to reach a deal.

Timing Could take place in March 2019, as soon as the UK leaves the EU.

FT verdict Philip Hammond, the UK chancellor of the exchequer, says no deal would be a “very, very bad outcome for Britain”. It is worse than that. It is simply not a viable option. There are almost no winners and the UK would be pursued in international courts for money the EU claims it owes. The government’s “no deal is better than a bad deal” bravado has receded; most officials concede this would be a self-inflicted wound of historic proportions.

2. Divorce-only agreement

Less disruptive than a no deal scenario. The UK would strike an Article 50 agreement with the EU on its departure from the bloc, but would leave the future relationship to be negotiated from the outside, with interim trade based on World Trade Organization rules. This is still a very hard Brexit, since there is no agreement to replace EU membership, but the two sides would have come to a mutual understanding rather than a position of conflict.

Winners By hugely increasing trade barriers with the EU, Britain would need to become more self-sufficient. Winners would include domestic suppliers to UK manufacturers who would not face as much competition.

In the longer term, companies oriented towards trade with countries with which the EU has no preferential deal might gain if the UK could strike a worthwhile free-trade deal more quickly. UK companies would have greater scope to lobby for state aid and contracts from the British government, currently outlawed by single market rules.

Losers Companies involved in EU-British trade on both sides of the channel would be hit by tariff and non-tariff barriers as well as the ability of governments to discriminate against them. Tariffs would be up to 10 per cent in the automotive sector, about 22 per cent on agricultural products and up to 59 per cent on specific items such as beef. Customs delays would still be significant at the hard border and behind it as companies would need to fill out rules of origin declarations.

Timing Would take effect in March 2019.

FT verdict Could prove to be one of the most protectionist steps in UK peacetime history. The increase in trade barriers with the UK’s biggest market would make the nation more insular with no guarantee that alternative trade deals would supplant the EU. The freedom to set the UK’s rules would encourage Britain to become an offshore tax haven, such as Bermuda. Meanwhile, it would abruptly lose all its current preferential trade terms with non-EU countries, since they were negotiated by the bloc.

3. Limited tariff-free deal

Britain strikes a limited free-trade agreement with the EU to maintain tariff-free trade in goods. The UK is free to agree deals with other countries, but there would be no guaranteed access to the EU market for the services sector. Customs checks would still add friction to trade with the EU and companies could have to duplicate their production lines, making some goods that satisfied UK regulations and others that met EU rules where these differed with Britain.

Winners Since Britain ran a £95bn goods trade deficit with the EU in 2016, the main winners would be EU manufacturers who could sell to the UK without facing tariffs — the likes of Fiat , BMW and Siemens .