Write an Error-free Research Protocol As Recommended by WHO: 21 Elements You Shouldn’t Miss!

Principal Investigator: Did you draft the research protocol?

Student: Not yet. I have too many questions about it. Why is it important to write a research protocol? Is it similar to research proposal? What should I include in it? How should I structure it? Is there a specific format?

Researchers at an early stage fall short in understanding the purpose and importance of some supplementary documents, let alone how to write them. Let’s better your understanding of writing an acceptance-worthy research protocol.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Protocol?

The research protocol is a document that describes the background, rationale, objective(s), design, methodology, statistical considerations and organization of a clinical trial. It is a document that outlines the clinical research study plan. Furthermore, the research protocol should be designed to provide a satisfactory answer to the research question. The protocol in effect is the cookbook for conducting your study

Why Is Research Protocol Important?

In clinical research, the research protocol is of paramount importance. It forms the basis of a clinical investigation. It ensures the safety of the clinical trial subjects and integrity of the data collected. Serving as a binding document, the research protocol states what you are—and you are not—allowed to study as part of the trial. Furthermore, it is also considered to be the most important document in your application with your Institution’s Review Board (IRB).

It is written with the contributions and inputs from a medical expert, a statistician, pharmacokinetics expert, the clinical research coordinator, and the project manager to ensure all aspects of the study are covered in the final document.

Is Research Protocol Same As Research Proposal?

Often misinterpreted, research protocol is not similar to research proposal. Here are some significant points of difference between a research protocol and a research proposal:

|

|

|

| A is written to persuade the grant committee, university department, instructors, etc. | A research protocol is written to detail a clinical study’s plan to meet specified ethical norms for participating subjects. |

| It is a plan to obtain funding or conduct research. | It is meant to clearly provide an overview of a proposed study to satisfy an organization’s guidelines for protecting the safety of subjects. |

| Research proposals are submitted to funding bodies | Research protocols are submitted to Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) within universities and research centers. |

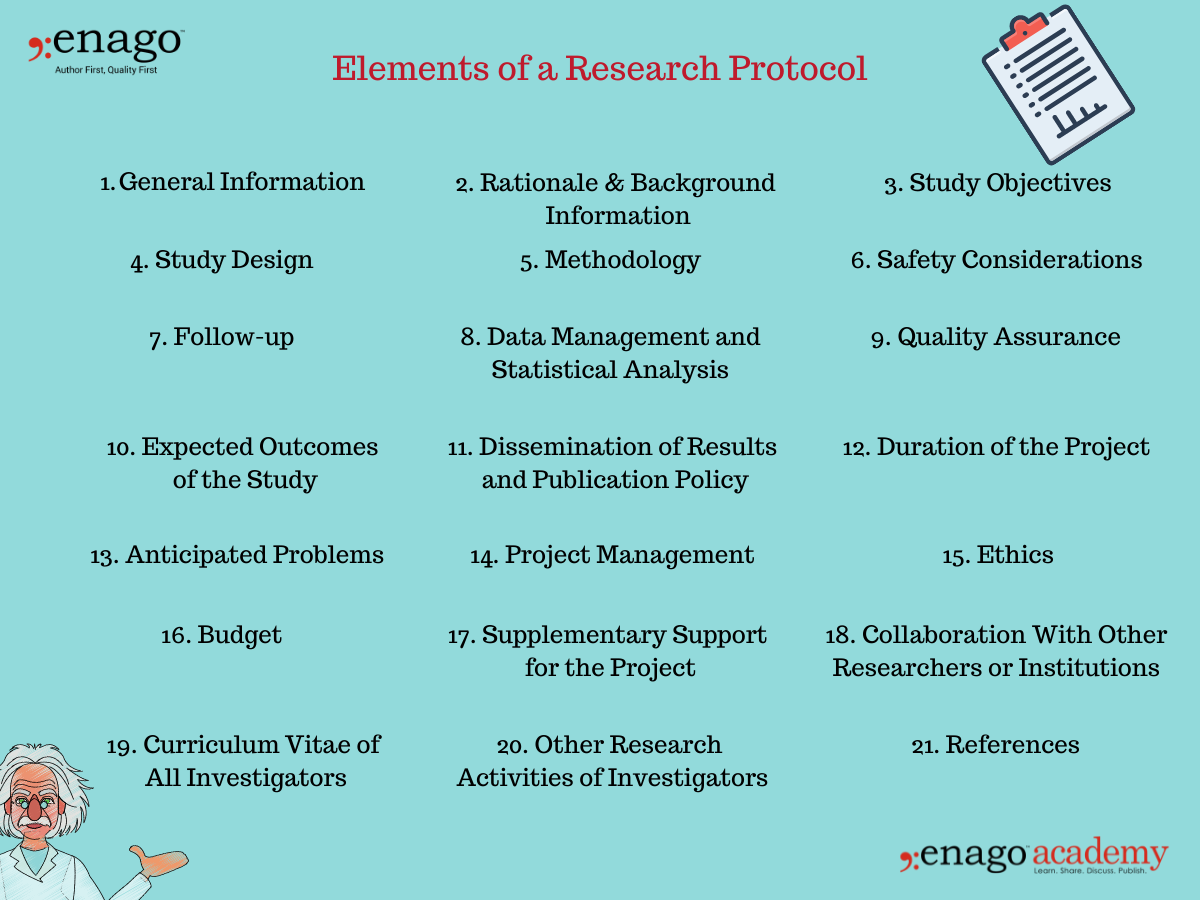

What Are the Elements/Sections of a Research Protocol?

According to Good Clinical Practice guidelines laid by WHO, a research protocol should include the following:

1. General Information

- Protocol title, protocol identifying number (if any), and date.

- Name and address of the funder.

- Name(s) and contact details of the investigator(s) responsible for conducting the research, the research site(s).

- Responsibilities of each investigator.

- Name(s) and address(es) of the clinical laboratory(ies), other medical and/or technical department(s) and/or institutions involved in the research.

2. Rationale & Background Information

- The rationale and background information provides specific reasons for conducting the research in light of pertinent knowledge about the research topic.

- It is a statement that includes the problem that is the basis of the project, the cause of the research problem, and its possible solutions.

- It should be supported with a brief description of the most relevant literatures published on the research topic.

3. Study Objectives

- The study objectives mentioned in the research proposal states what the investigators hope to accomplish. The research is planned based on this section.

- The research proposal objectives should be simple, clear, specific, and stated prior to conducting the research.

- It could be divided into primary and secondary objectives based on their relativity to the research problem and its solution.

4. Study Design

- The study design justifies the scientific integrity and credibility of the research study.

- The study design should include information on the type of study, the research population or the sampling frame, participation criteria (inclusion, exclusion, and withdrawal), and the expected duration of the study.

5. Methodology

- The methodology section is the most critical section of the research protocol.

- It should include detailed information on the interventions to be made, procedures to be used, measurements to be taken, observations to be made, laboratory investigations to be done, etc.

- The methodology should be standardized and clearly defined if multiple sites are engaged in a specified protocol.

6. Safety Considerations

- The safety of participants is a top-tier priority while conducting clinical research .

- Safety aspects of the research should be scrutinized and provided in the research protocol.

7. Follow-up

- The research protocol clearly indicate of what follow up will be provided to the participating subjects.

- It must also include the duration of the follow-up.

8. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

- The research protocol should include information on how the data will be managed, including data handling and coding for computer analysis, monitoring and verification.

- It should clearly outline the statistical methods proposed to be used for the analysis of data.

- For qualitative approaches, specify in detail how the data will be analysed.

9. Quality Assurance

- The research protocol should clearly describe the quality control and quality assurance system.

- These include GCP, follow up by clinical monitors, DSMB, data management, etc.

10. Expected Outcomes of the Study

- This section indicates how the study will contribute to the advancement of current knowledge, how the results will be utilized beyond publications.

- It must mention how the study will affect health care, health systems, or health policies.

11. Dissemination of Results and Publication Policy

- The research protocol should specify not only how the results will be disseminated in the scientific media, but also to the community and/or the participants, the policy makers, etc.

- The publication policy should be clearly discussed as to who will be mentioned as contributors, who will be acknowledged, etc.

12. Duration of the Project

- The protocol should clearly mention the time likely to be taken for completion of each phase of the project.

- Furthermore a detailed timeline for each activity to be undertaken should also be provided.

13. Anticipated Problems

- The investigators may face some difficulties while conducting the clinical research. This section must include all anticipated problems in successfully completing their projects.

- Furthermore, it should also provide possible solutions to deal with these difficulties.

14. Project Management

- This section includes detailed specifications of the role and responsibility of each investigator of the team.

- Everyone involved in the research project must be mentioned here along with the specific duties they have performed in completing the research.

- The research protocol should also describe the ethical considerations relating to the study.

- It should not only be limited to providing ethics approval, but also the issues that are likely to raise ethical concerns.

- Additionally, the ethics section must also describe how the investigator(s) plan to obtain informed consent from the research participants.

- This section should include a detailed commodity-wise and service-wise breakdown of the requested funds.

- It should also include justification of utilization of each listed item.

17. Supplementary Support for the Project

- This section should include information about the received funding and other anticipated funding for the specific project.

18. Collaboration With Other Researchers or Institutions

- Every researcher or institute that has been a part of the research project must be mentioned in detail in this section of the research protocol.

19. Curriculum Vitae of All Investigators

- The CVs of the principal investigator along with all the co-investigators should be attached with the research protocol.

- Ideally, each CV should be limited to one page only, unless a full-length CV is requested.

20. Other Research Activities of Investigators

- A list of all current research projects being conducted by all investigators must be listed here.

21. References

- All relevant references should be mentioned and cited accurately in this section to avoid plagiarism.

How Do You Write a Research Protocol? (Research Protocol Example)

Main Investigator

Number of Involved Centers (for multi-centric studies)

Indicate the reference center

Title of the Study

Protocol ID (acronym)

Keywords (up to 7 specific keywords)

Study Design

Mono-centric/multi-centric

Perspective/retrospective

Controlled/uncontrolled

Open-label/single-blinded or double-blinded

Randomized/non-randomized

n parallel branches/n overlapped branches

Experimental/observational

Endpoints (main primary and secondary endpoints to be listed)

Expected Results

Analyzed Criteria

Main variables/endpoints of the primary analysis

Main variables/endpoints of the secondary analysis

Safety variables

Health Economy (if applicable)

Visits and Examinations

Therapeutic plan and goals

Visits/controls schedule (also with graphics)

Comparison to treatment products (if applicable)

Dose and dosage for the study duration (if applicable)

Formulation and power of the studied drugs (if applicable)

Method of administration of the studied drugs (if applicable)

Informed Consent

Study Population

Short description of the main inclusion, exclusion, and withdrawal criteria

Sample Size

Estimated Duration of the Study

Safety Advisory

Classification Needed

Requested Funds

Additional Features (based on study objectives)

Click Here to Download the Research Protocol Example/Template

Be prepared to conduct your clinical research by writing a detailed research protocol. It is as easy as mentioned in this article. Follow the aforementioned path and write an impactful research protocol. All the best!

Clear as template! Please, I need your help to shape me an authentic PROTOCOL RESEARCH on this theme: Using the competency-based approach to foster EFL post beginner learners’ writing ability: the case of Benin context. I’m about to start studies for a master degree. Please help! Thanks for your collaboration. God bless.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Promoting Research

Graphical Abstracts Vs. Infographics: Best practices for using visual illustrations for increased research impact

Dr. Sarah Chen stared at her computer screen, her eyes staring at her recently published…

- Publishing Research

10 Tips to Prevent Research Papers From Being Retracted

Research paper retractions represent a critical event in the scientific community. When a published article…

- Industry News

Google Releases 2024 Scholar Metrics, Evaluates Impact of Scholarly Articles

Google has released its 2024 Scholar Metrics, assessing scholarly articles from 2019 to 2023. This…

![outline of research protocol What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- AI in Academia

- Career Corner

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer Review Week 2024

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Reasons to Submit

- About Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, contents of a research study protocol, conflict of interest statement, how to write a research study protocol.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Julien Al Shakarchi, How to write a research study protocol, Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies , Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, snab008, https://doi.org/10.1093/jsprm/snab008

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. Many funders such as the NHS Health Research Authority encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will describe how to write a research study protocol.

A study protocol is an essential part of a research project. It describes the study in detail to allow all members of the team to know and adhere to the steps of the methodology. Most funders, such as the NHS Health Research Authority in the United Kingdom, encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology, help with publication of the study and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will explain how to write a research protocol by describing what should be included.

Introduction

The introduction is vital in setting the need for the planned research and the context of the current evidence. It should be supported by a background to the topic with appropriate references to the literature. A thorough review of the available evidence is expected to document the need for the planned research. This should be followed by a brief description of the study and the target population. A clear explanation for the rationale of the project is also expected to describe the research question and justify the need of the study.

Methods and analysis

A suitable study design and methodology should be chosen to reflect the aims of the research. This section should explain the study design: single centre or multicentre, retrospective or prospective, controlled or uncontrolled, randomised or not, and observational or experimental. Efforts should be made to explain why that particular design has been chosen. The studied population should be clearly defined with inclusion and exclusion criteria. These criteria will define the characteristics of the population the study is proposing to investigate and therefore outline the applicability to the reader. The size of the sample should be calculated with a power calculation if possible.

The protocol should describe the screening process about how, when and where patients will be recruited in the process. In the setting of a multicentre study, each participating unit should adhere to the same recruiting model or the differences should be described in the protocol. Informed consent must be obtained prior to any individual participating in the study. The protocol should fully describe the process of gaining informed consent that should include a patient information sheet and assessment of his or her capacity.

The intervention should be described in sufficient detail to allow an external individual or group to replicate the study. The differences in any changes of routine care should be explained. The primary and secondary outcomes should be clearly defined and an explanation of their clinical relevance is recommended. Data collection methods should be described in detail as well as where the data will be kept secured. Analysis of the data should be explained with clear statistical methods. There should also be plans on how any reported adverse events and other unintended effects of trial interventions or trial conduct will be reported, collected and managed.

Ethics and dissemination

A clear explanation of the risk and benefits to the participants should be included as well as addressing any specific ethical considerations. The protocol should clearly state the approvals the research has gained and the minimum expected would be ethical and local research approvals. For multicentre studies, the protocol should also include a statement of how the protocol is in line with requirements to gain approval to conduct the study at each proposed sites.

It is essential to comment on how personal information about potential and enrolled participants will be collected, shared and maintained in order to protect confidentiality. This part of the protocol should also state who owns the data arising from the study and for how long the data will be stored. It should explain that on completion of the study, the data will be analysed and a final study report will be written. We would advise to explain if there are any plans to notify the participants of the outcome of the study, either by provision of the publication or via another form of communication.

The authorship of any publication should have transparent and fair criteria, which should be described in this section of the protocol. By doing so, it will resolve any issues arising at the publication stage.

Funding statement

It is important to explain who are the sponsors and funders of the study. It should clarify the involvement and potential influence of any party. The sponsor is defined as the institution or organisation assuming overall responsibility for the study. Identification of the study sponsor provides transparency and accountability. The protocol should explicitly outline the roles and responsibilities of any funder(s) in study design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing and dissemination of results. Any competing interests of the investigators should also be stated in this section.

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. It should be written in detail and researchers should aim to publish their study protocols as it is encouraged by many funders. The spirit 2013 statement provides a useful checklist on what should be included in a research protocol [ 1 ]. In this paper, we have explained a straightforward approach to writing a research study protocol.

None declared.

Chan A-W , Tetzlaff JM , Gøtzsche PC , Altman DG , Mann H , Berlin J , et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials . BMJ 2013 ; 346 : e7586 .

Google Scholar

- conflict of interest

- national health service (uk)

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| January 2022 | 201 |

| February 2022 | 123 |

| March 2022 | 271 |

| April 2022 | 354 |

| May 2022 | 429 |

| June 2022 | 380 |

| July 2022 | 405 |

| August 2022 | 560 |

| September 2022 | 539 |

| October 2022 | 690 |

| November 2022 | 671 |

| December 2022 | 609 |

| January 2023 | 872 |

| February 2023 | 1,165 |

| March 2023 | 1,277 |

| April 2023 | 1,183 |

| May 2023 | 1,292 |

| June 2023 | 1,117 |

| July 2023 | 1,040 |

| August 2023 | 936 |

| September 2023 | 941 |

| October 2023 | 1,028 |

| November 2023 | 993 |

| December 2023 | 910 |

| January 2024 | 1,251 |

| February 2024 | 1,051 |

| March 2024 | 1,411 |

| April 2024 | 991 |

| May 2024 | 895 |

| June 2024 | 710 |

| July 2024 | 629 |

| August 2024 | 714 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- JSPRM Twitter

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2752-616X

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press and JSCR Publishing Ltd

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

The Research Protocol

- First Online: 17 December 2015

Cite this chapter

- Gilberto Lopes M.D., M.B.A. 2 ,

- Gustavo Werutsky 3 &

- Patricia Moretto M.D., M.Sc. 4

833 Accesses

2 Altmetric

The research protocol is defined as the most important document in clinical research which helps the researchers and the scientists to understand the necessity of the study and the way of execution and completion.

The protocol outlines the rationale for the study, its objective, the methodology used, and how the data will be managed and analyzed. It highlights how ethical issues have been considered, and where appropriate, how gender and minority issues are being addressed.

An additional step, after writing the protocol, particularly in large studies with teams of investigators, is to develop what may be called the operations manual for the study.

The full research protocol development takes usually 4 months, but is variable depending on the complexity of the research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Research (See Clinical Research; Research Ethics)

Introduction to Clinical Research Concepts, Essential Characteristics of Clinical Research, Overview of Clinical Research Study Designs

The beginning – historical aspects of clinical research, clinical research: definitions, “anatomy and physiology,” and the quest for “universal truth”.

Conselho Nacional de Saúde (Brasil). Resolução n o 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Brasília, 2012 [citado 2014 Mar 11]. http://www.conselho.saude.gov.br/web_comissoes/conep/index.html . Assessed November 2014.

IARC cancer statistics. http://globocan.iarc.fr/ . Assessed November 2014. OR http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2014/pdfs/pr224_E.pdf . Assessed Nov 2014.

WHO. Cancer fact sheet. Geneva: WHO; 2014. Accessed Nov 2014.

Google Scholar

IAEA. A silent crisis: cancer treatment in developing countries. Vienna: Division of Public Information, IAEA; 2003.

Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Killen J, Grady C. What makes clinical research in developing countries ethical? The benchmarks of ethical research. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(5):930–7. Epub 2004 Feb 17.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Oncoclinicas do Brasil, Rua Maranhão 569/4, São Paulo, SP, 01240-001, Brazil

Gilberto Lopes M.D., M.B.A.

Latin American Cooperative Oncology Group, 6681, 99A/806 Ipiranga Avenue, Porto Alegre, RS, 90619-900, Brazil

Gustavo Werutsky

Oncology, Caxias do Sul University Foundation, Caxias do Sul General Hospital, Rua Prof. Antônio Vignoli, 255 - Bairro Petrópolis, Caxias do Sul, RS, 95070-561, Brazil

Patricia Moretto M.D., M.Sc.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gilberto Lopes M.D., M.B.A. .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

South African Medical Research Council, Francie van Zyl, Parrow, Cape Town, South Africa

Daniela Cristina Stefan

Barriers to Research in Developing Countries and Possible Steps to Overcome Them

The rise in the number of cancer cases, 14 million new cancer cases globally every year, with the majority of cases occurring in developing countries [ 1 ], has a great impact in those countries and must be addressed. Additionally, treatment options are both limited and expensive, and trial participation is an opportunity for better cancer care.

There are four key components to cancer control and, therefore, areas in need of research: prevention, early detection, diagnosis and treatment, and palliation, as stated by WHO [ 2 ]. In each of these areas, developing countries face major challenges, not only in dealing with the ongoing problems, but also with research opportunities.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) uses the term “developing country” for less-developed regions such as: all regions of Africa, Asia (excluding Japan), Latin America and the Caribbean, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia [ 1 ].

In order to overcome barriers to doing research, and so that the results will have a chance to impact on local problems, some points have to be taken into consideration:

Choose a Relevant Topic to Your Community

Make sure that the many pressing problems in developing countries are being addressed, so local patients are able to see direct benefits. The research question has to be relevant for the population where it is tested. This is an ethics question, as well as a question that will improve accrual.

There is a broad consensus that efforts and scarce resources in developing countries should focus first and foremost on prevention and awareness rising, and secondly on early detection, treatment, and research. However, this should not prevent the progress and improvement of research capabilities in these countries.

Will the Protocol Be Feasible?

If the issue being looked at is technology, it should be noted that most health equipment used in developing nations is manufactured in the first world. Sometimes the equipment does not work on arrival, with lack of parts or trained technicians to fix it or do maintenance. Technical, social, cultural, and economic factors must be considered when looking at new technologies for these countries.

Researchers should also remember that in some countries there is limited access to radiotherapy, so research questions involving concurrent or sequential treatments may not be the best research option.

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) [ 3 ], although the developing world constitutes 85 % of the world’s population, it only has 2200 radiation therapy machines compared with the 4500 in the developed world. Those developing countries that have access to radiotherapy face considerable financial investment constrains and for up to 5 years are required to provide the necessary training, equipment set-up and maintenance, protocols, and quality control. Therefore, even if budget is not a concern for a specific study, creating a Radiotherapy Service for research purposes in a developing country would take a lot of planning, resources, and time.

In order to do the scans as planned in a protocol, radiologists with RECIST knowledge and time to do proper comparative reports are also needed and are not always available. Even with a central review, the delay in getting the images as planned could result in wrong clinical decisions and protocol violations.

The same applies to health workers, where it is sometimes necessary to train locals and adapt to the capabilities of the country. Obviously, if feasible, the improvement in capabilities would be welcome, as in addition to the research they could offer new treatments to patients and open the way for further research.

Funding and Economic Incentives

The challenges are many and substantial such as insufficient political priority and funding among donor agencies and governments of developing countries that have many competing priorities.

However, the local investigator must be familiarized with potential local and international sources: universities, government incentives, international for-profit initiatives, and creative not-for-profit partnerships.

Involvement in research with pharmaceutical companies, which can be lucrative to the institutions where it is done, is an obvious way to start, but usually some capabilities must already be in place to attract this kind of research. A pressing challenge is getting industry partners to invest in the clinical development of drugs that offer limited commercial opportunities. Despite the fact that the cost to approve drugs is lower in developing countries, it is still high and is a problem that universities and public institutions cannot overcome alone.

Intellectual Property

Partnership with industry may be necessary to develop early research in universities, and intellectual property licensing should be viewed as a requirement to attract industry partners. However, researchers must pay attention to patent systems before concluding agreements with pharmaceutical companies (who want a patent system that will protect their investments for as long as possible) and be careful, clearly stating on contracts who has ownership of the data collected, of publications or abstracts arising from study results, and of information obtained based on new data analyses.

Encouragement and Structure

In some developing countries, in addition to other research barriers, such as lack of diagnostic, treatment, and monitoring capacity, there is lack of academic staff (oncology and hematology expertise, specialized cancer nurses, pharmacists), qualified monitors, lack of encouragement to conduct and publish research, as well as lack of a research publishing infrastructure. Training personnel abroad, in other research centers, or in-house training before starting a project may be needed.

Planning and Accrual

Researchers may have problems with proper calculation for accrual, as most cancer registries in low- and middle-income countries have shortcomings and screening programs are largely absent. This can lead to erroneous assumptions regarding the relative frequencies of the varying levels of different cancers based on global trends, which can be misleading. These issues are major challenges for the future, but setting up an institutional cancer registry could be a good start in research planning.

In order to properly choose the study population, the researcher should take into consideration the contrasts in patient’s disease profiles: most cancer patients in developing countries have advanced or incurable cancers at the time their initial presentation, a different profile from that seen in developed countries. The prevalence and incidence can be also markedly different in comparison to developed countries for each disease site.

Developed countries often have relatively high rates of lung, colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer because of the earlier onset of the tobacco epidemic, the earlier exposure to occupational carcinogens, and the Western diet and lifestyle. In contrast, up to a fourth of cancers in developing countries are associated with chronic infections. Liver cancer is often causally associated with infection by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), cervical cancer is associated with infection by certain types of human papillomavirus (HPV), and stomach cancer is associated with Helicobacter pylori infection.

Weak referral systems can also make the accrual slow. This should be anticipated and should encourage creative solutions to strengthen it by the researchers. In some countries there are few cancer services. This can be helpful in the sense that it aggregates most of the cases in a few centers. However, if the health system is a mix of public and private, this dilutes the number of cases, increasing the numbers of institutions necessary for the accrual, and increasing the budget.

Issues During the Trial and for Follow-Up

There is sometimes a lack of awareness of the signs and symptoms of cancer and side effects from treatments, a lack of money to travel to a hospital, which could result in sub-notification of important events or delays in the notification and treatment of important side effects.

As health systems in developing countries are not set up for chronic disease management, chronic diseases such as cancer are often lost to follow-up. Therefore, organizing proper follow-up for patients enrolled in the trials could be a problem.

Need for Palliative Care Research

In some developing countries, there is lack of trained personnel to administer palliative care or pain killers such as morphine. This is particularly startling given that approximately 70 % of the patients seen at these hospitals are at such an advanced stage of cancer upon arrival that they are beyond cure and palliative care and pain management is the only benefit they can still receive. Studies in the palliative setting, which should be relatively easy to accrue, could have a major impact in the quality of life of patients and in the training of local health workers.

Ethics Barriers

The ethics principles in clinical research were established in order to avoid previous abuses/misconducts, such as the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis (TSUS).

Based on the influential codes of ethics and regulations that guide ethical clinical research (Nuremberg Code Footnote 1 ; Declaration of Helsinki 1 , Belmont Report 1 , CIOMS 1 , U.S. Common Rule 1 ), seven main principles have been described as guiding the conduct of ethical research 1 : social and clinical value; scientific validity; fair subject selection; favorable risk-benefit ratio; independent review; informed consent; and respect for potential and enrolled subjects.

The trial should follow the ethics rules from the country where it was originally written and in the other countries where the research will be developed. Some areas of ethics controversy in developing countries are: the standard of care to be used (as the local standard of care could mean no treatment or less than the “worldwide best”) and the quality of informed consent (due to lack of knowledge, language/cultural barriers, high workload, and time constraints). The discussion about valid science, social benefits, and favorable risk:benefit ratio to justify less than the worldwide best care has to take place early on in the protocol design to avoid an unethical and/or unfeasible trial. Efforts should be taken to improve the quality of informed consent, such as researchers training and observance to the GCP.

Not all the population in developing countries is vulnerable, but a great deal of them is at increased risk of exploitation due to poverty, limited healthcare services, illiteracy, cultural and linguistic differences, and limited understanding of the nature of scientific research. To make things worse, regulatory infrastructures, which could minimize this risk, may lack effectiveness or be nonexistent. As suggested by Emanuael et al. [ 4 ], “collaborative partnerships between researchers and sponsors in developed countries and researchers, policy makers, and communities in developing countries help to minimize the possibility of exploitation by ensuring that a developing country determines for itself whether the research is acceptable and responsive to the community’s health problems.”

Lastly, the many differences between developed and developing countries, in addition to the various sociocultural groups existing in a country, must be taken into consideration during the research protocol conception and execution. Specifically, issues to keep private information confidential, to find the person responsible for giving consent, and how best to explain the clinical trial purpose, benefits, risks, and involved procedures could arise due to local peculiarities.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Lopes, G., Werutsky, G., Moretto, P. (2016). The Research Protocol. In: Stefan, D. (eds) Cancer Research and Clinical Trials in Developing Countries. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18443-2_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18443-2_5

Published : 17 December 2015

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-18442-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-18443-2

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Human Subjects Office

Protocol template.

Researchers use study protocols to provide specific details about the study, including background, purpose, study design, safety assessments and analysis plan. If a formal protocol does not exist, the IRB may require the UI investigator to supply one (e.g., an investigator initiated study or a complex study) The UI IRB recommends using an NIH Protocol Outline Template for Phase I, Phase II-III, or Behavioral and Social Science Research (BSSR) Involving Humans. The NIH and FDA provide a Protocol Template tool for creating a Protocol. Information described in the HawkIRB application must be consistent with the corresponding protocol.

Please refer to the UI Operations Manual, UI IRB Standard Operating Procedures & Researcher Guide (Section II Part 1.A, Part 18.A., and Part 19.A.), and The Point for assistance in aligning the protocol with the institutional guidelines.

Phase 1 or non-Clinical Trial : For studies that involves a Phase 1 clinical or therapeutic intervention, see Protocol Outline template .

Phase II-III Clinical Trials : For the FDA/NIH draft protocol template for Phase II through III trials, use the Phase 2 and 3 Clinical Trials that Require FDA-IND or IDE Application .

Behavioral and Social Science Research (BSSR) Involving Humans Protocol Template : Template for behavioral and social science researchers prepare research protocols for human studies measuring a social or behavioral outcome or testing a behavioral or social science-based intervention, use the Behavioral and Social Science Research (BSSR) Involving Humans protocol recommended by NIH.

- Planning a Research Project

- Getting Started

- Study Designs

- Data Management

- Budgets & Funding This link opens in a new window

- Writing Proposals This link opens in a new window

- Ethics Approval

Clinical Resource Guides

Databases and Apps A-Z

Education and Training

Equipment Booking

Keeping up to date

Research Repository

Research Toolkit

What does the library have?

What the library can do for you

- Evidence-Based Practice Guide

- Systematic Review Guide

- Quality Improvement Projects

- Ethics and Law Resource Guide

- Research and Grant Proposals

- Literature Searching Guide

- Grey Literature Guide

- Data Collection & Storage

- Statistics for Research

- Writing, Referencing & Publishing

- Communicating Research Findings

- Research Promotion & Impact

- Templates & examples

- Registration & publication

- Monash Health requirements

What is a study protocol?

A protocol is a detailed plan for a research study, outlining the specifics of how the research will be conducted. It is an essential document that helps to ensure research is conducted in a safe and ethical manner, and that the integrity of the research is preserved throughout the life of the study.

Common elements of a protocol

Melbourne Children's Trials Centre. (2017). Developing, amending and complying with research protocols. https://www.mcri.edu.au/images/research/training-resources/research-process-resources/guideline_developing_research_protocols.pdf

See the Data Management page in this guide for information on creating a data management plan (DMP), plus online tools and templates.

Literature review

Protocols draw on relevant literature at multiple points, e.g. in background information, when providing a rationale for the study, and when discussing known risks and benefits. If you haven't yet completed a literature search, now is the time to do one!

The Library offers training and guidance on conducting literature reviews, including a webinar on literature searching and a Literature Searching Guide .

Library research support

The Library offers various forms of research support depending on the purpose of your research. Our research support includes:

- Research consultations

- Literature search service

- Literature review report service

- Feedback on your literature search strategy

- Co-authorship for systematic reviews and other evidence synthesis projects

Complete this online form to request research support and learn more about each service offered.

Request research support

For an overview of Library research support, click the link below.

Library Research Support Services

Additional resources

- Protocol writing in clinical research (2016) by A. Al-Jundi & S. Sakka

- Write an error-free research protocol as recommended by WHO: 21 elements you shouldn't miss! (2022) by U. Bhosale

- How to Write a Research Protocol: Tips and Tricks (2018) by M. Cameli

- Guidance: Developing a protocol for a clinical research project (n.d.) by the Clinical Research Development Office, RCH

Protocol templates

The Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) provides annotated protocol templates for the following study designs:

- Clinical trial - drug/device intervention

- Clinical trial - intervention is not drug/device

- Observational studies

- Clinical audits / Quality assurance

To access the templates, click the blue button below and scroll down to the section on Clinical Research Development Office (CRDO) resources.

MCRI protocol templates

Qualitative studies

The NHS Health Research Authority offers a protocol template for qualitative research at the bottom of the page linked below.

NHS Qualitative protocol template

Example protocols

- RCT - A clinical investigation evaluating efficacy of a full-thickness placental allograft (Revita) in lumbar microdiscectomy outcomes

- Observational study - Prospective observational long-term safety registry of Multiple Sclerosis patients who have participated in cladribine clinical trials (PREMIERE)

- Systematic review and meta-analysis - Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis on the associations between shift work and sickness absence

Tip: The results of your literature search may include published protocols relevant to your research question.

Journal requirements

Journals that publish study protocols provide guidelines for the content required in protocol manuscripts. It can be helpful to review these guidelines even if you do not intend to publish your protocol in a peer-reviewed journal.

Search for the manuscript guidelines for your preferred journal(s) or review the examples below.

- BMC Nursing

Registering or publishing your protocol

Researchers are encouraged to submit their protocol for publication in a scholarly journal, and/or register their protocol in a relevant database. Many funding agencies also require grant recipients to register or publish their study protocol.

Where to register your protocol

Your study design generally determines where you register your protocol. See the table below for options on where to register your protocol.

| Systematic reviews, rapid reviews, | (Open Science Framework) |

| Clinical trials

| One or more trials registries (ANZTCR) (International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) (Open Science Framework) |

| Observational Studies

| (ANZTCR) (Open Science Framework) |

| Qualitative studies | (ANZTCR) (Open Science Framework) |

Where to publish your protocol

There are two main options:

- E.g. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology , Journal of Allied Health , Journal of Clinical Nursing

- E.g. BMC Trials , JMIR Research Protocols , Contemporary Clinical Trials

Be aware of predatory publishers - Check our our Writing, Referencing & Publishing Guide or our Predatory Publishing A-Z for more information.

Relevant Prompt documents include:

- Research Agreements Procedure

- Publication and dissemination of research findings

- Intellectual Property

- Research Ethics and Governance – Protocol and Investigational Brochure Content, Design, Amendments and Compliance

- Privacy and Confidentiality in Research

- Research Ethics and Governance – Authorship for Research

Visit the Forms Library from Research Support Services for links and more information.

Research - Forms Library

Research agreements

The Research Agreements Procedure provides guidance on which agreement to use in which circumstance and the pathway to follow for seeking review and approval. There are preferred templates for various types of studies, such as collaborative or investigator-initiated studies.

For more information, visit the Research Agreements page from Research Support Services.

Research Agreements page

Protocol amendments

Once your protocol is finalised and ethics approval has been granted, you must notify the Monash Health Research Support Services team regarding protocol amendments .

Monash Health acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the land, the Wurundjeri and Boonwurrung peoples, and we pay our respects to them, their culture and their Elders past, present and future.

We are committed to creating a safe and welcoming environment that embraces all backgrounds, cultures, sexualities, genders and abilities.

- << Previous: Study Designs

- Next: Data Management >>

- Last Updated: Aug 22, 2024 1:16 PM

- URL: https://monashhealth.libguides.com/planning_research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Bras Pneumol

- v.49(6); 2023

- PMC10760430

Crafting a research protocol: a stepwise comprehensive approach

Elaboração de um protocolo de pesquisa: abordagem abrangente passo a passo, ricardo gassmann figueiredo.

1 . Programa de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Coletiva, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana - PPGSC-UEFS - Feira de Santana (BA) Brasil.

2 Methods in Epidemiologic, Clinical, and Operations Research-MECOR-program, American Thoracic Society/Asociación Latinoamericana del Tórax, Montevideo, Uruguay.

Cecilia María Patino

3 Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles (CA) USA.

Juliana Carvalho Ferreira

4 . Divisão de Pneumologia, Instituto do Coração, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo (SP) Brasil.

PRACTICAL SCENARIO

A group of researchers plan to conduct a cross-sectional study to estimate the prevalence of frailty in elderly patients with moderate to severe asthma and to report a measure of association between asthma control and frailty. 1 The research protocol outlines the complex interactions of asthma control in frail patients and motivation to address this research question. Study design, objectives, methods, ethical issues, risks, and impact were also detailed in the protocol.

WHAT IS A RESEARCH PROTOCOL?

A well-structured research protocol guides researchers through the intricate process of conducting rigorous research. A research protocol is designed to be concise and self-contained, and to summarize the core aspects of the study. Self-discipline is vital in this process, as it requires the investigator to structure the central concepts of the study and reveal particular issues that demand attention. 2 The research protocol often serves as the foundation for the development of manual of operating procedures, which includes comprehensive information on the organization and policies of the study, as well as an operational approach to the procedures outlined in the study protocol; therefore, both documents complement each other.

ELEMENTS OF A RESEARCH PROTOCOL

The research protocol framework (outlined in Chart 1 ) usually includes a title, rationale, background information, objectives, methodology, data management, statistical plan, quality control, ethics, budget, developing plan, timeline, references, and appendices, although the sections included vary depending on institutional templates.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Title | Concise, reflecting study main ideas, and attracting reader’s attention |

| Background and rationale | What is the problem? Why is it important? What is known about it? |

| Objectives | Specific, measurable, and established prior to carrying out the study |

| Relevance and study design | Contributions of the study to the field, aligned with rationale and objectives |

| Methods | Participants, exposures/intervention, outcomes, study setting, eligibility criteria, participant timeline, sample size, recruitment, and blinding Detailed script: How will the study be conducted? Why was the described design chosen? |

| Data collection, access, and management | Methods for data storage, security, privacy, and treatment of missing data |

| Statistical plan | Descriptive statistics, hypothesis testing, sample size, and power calculation |

| Quality control | Credibility of the research: instruments, data collection, data acquisition |

| Ethics | Ethical dilemmas, application to ethics research committees, Informed consent form |

| Roles and responsibilities | Affiliations, roles, and responsibilities of protocol contributors |

| Budget | Detailed expenses: personnel, equipment, consumables, logistics |

| Funding | Sources of financial support |

| Dissemination plan | Effective communication of research findings |

| Timeline | Be realistic about project management throughout the research |

| References | Check publishers’ guidelines, consider using reference manager software |

| Appendices | Extensive descriptions of procedures, questionnaires, and informed consent forms |

| Protocol version | Indicator of version and date of the protocol |

The title should be concise, descriptive, and engage readers, effectively reflecting the core of the research. 3 The background section outlines the driving factors and motivation for conducting the research. It should provide a broad context, elucidate the problem, address specific knowledge gaps, and establish the rationale for the study. In our practical example, the authors provided background information about how the multidimensional aspects of frailty are imbricated into proper asthma management in patients with advanced age. This section should align with the objectives, highlighting the potential impact of the study. Research objectives should be clear, measurable, precise, and set before conducting the study. 2 After the statement of the primary objective, secondary aims might be appropriate. The objectives will guide the study design and methodology, directing attention toward the intended research outcomes.

The methods section is a detailed blueprint of the research project and the basis for the manual of operating procedures. It should detail the study design, participant selection (eligibility, sampling, and recruitment), variables, data acquisition, data management (storage, security, privacy, and treatment of missing data), statistical plan, and sample size calculation. The scientific robustness of the study relies on its methodology, ensuring validity and replicability. The statistical plan should clearly outline the analysis methods, software used, and criteria for determining statistical significance. Quality control mechanisms uphold the internal validity of the study. This segment should describe measures to minimize bias and ensure data quality. 2 Steps might include regular data verification, calibration and certification of instruments, as well as research personnel training.

Ethical considerations are paramount in research. This section should document the issues that are likely to raise ethical concerns, including informed consent forms, confidentiality, data protection, and potential ethical dilemmas. 3 Moreover, it should also mention approvals obtained from institutional review boards. The budget section details the financial requirements of the research. It includes costs with personnel, equipment, materials, logistics, consumables, and contingencies. A realistic and well-planned timeline is crucial for successful project management.

Deficiencies in effectively disseminating and transferring research-based knowledge into clinical practice can impair the potential benefits of the research project. Therefore, most health research funding agencies expect commitment from investigators to disseminate the study findings actively. Integrating a dissemination plan in the research protocol will facilitate effective communication of research outcomes to the scientific community and those who can apply the knowledge in real-world situations.

KEY MESSAGES

- A comprehensive research protocol not only provides a roadmap for the implementation of the study but also ensures that the research question is addressed according to high-quality research standards.

- Quality control is essential to improve internal validity of the study.

- A structured approach to conducting research reduces the likelihood of misleading conclusions and biases, ensuring validity and reproducibility of the study.

Protocol Outline

| A. B. C. Appendix A

The IHRIRB’s assessment of your research proposal involves a series of steps: (1) identifying the risks associated with the research, as distinguished from the risks the participants would experience even if not participating in the research; (2) determining that risks will be minimized; (3) identifying the probable benefits to be derived from the research; (4) determining that risks are reasonable in relation to the benefits to the participants, if any, and the importance of the knowledge to be gained; (5) ensuring that potential participants will be provided with an accurate and fair description of the risks or discomforts of the anticipated benefits; and (6) determining the intervals of periodic review. To ensure that the IHRIRB completes their review in a timely manner, your proposal must include the following information, as applicable: ¨ Cover letter with a list of all investigators and a contact person and telephone number ¨ Detailed protocol of study design, sampling, analyses, timelines, evaluation, and community involvement ¨ Informed consent and assent forms ¨ Other attachments, such as a copy of scripts or survey that will be used, materials that will be distributed, etc. If your proposal is missing any required items, review of your proposal will be delayed. SAMPLE PROTOCOL OUTLINE POSTED BELOW.

Your research Protocol should discuss in detail how you plan to carry out the research, how you will analyze the data that you collect, and what you plan to do with the results. The following are points that you should address in your protocol.

¨ Provide relevant research background and explain why this activity is necessary or important. ¨ Describe the potential impact of the proposed research.

¨ Provide a complete description of the study design, sequence, and timing of all study procedures that will be performed. Provide this information for pilot, screening, intervention, and follow-up phases. Include all materials that will be used in the procedure, such as surveys, scripts, questionnaires, etc. Attach flow sheets if they will help the reader understand the procedures. ¨ Describe how study procedures differ from standard care or procedures (e.g., medical, psychological, educational, etc.). ¨ If any deception or withholding of complete information is required, explain why this is necessary and attach a debriefing statement. ¨ Describe where the study will take place ¨ A letter of approval and cooperation from each participating site is needed. For example, if the study will be conducted in the local school system, an approval letter from the School Board and Superintendent are necessary.

¨ Explain how the nature of the research requires or justifies using the participant population. ¨ Provide the approximate number and ages for the control and experimental groups. ¨ Describe the gender and minority representation of the participant population. ¨ Describe the criteria for selection for each participant group. ¨ Describe the exclusion criteria exclusion for each participant group. ¨ Describe the source for participants and attach letters of cooperation from agencies, institutions, or others involved in the recruitment. ¨ Explain who will approach the participants and how the participants will be approached. Explain what steps you will take to avoid coercion and protect privacy. Submit advertisements, flyers, contact letters, and phone contact protocols. ¨ Explain if participants will receive payments, services without charge, or extra course credit. ¨ Explain if participants will be charged for any study procedures.

¨ Describe the nature and amount of risk of injury, stress, discomfort, invasion of privacy, and other side effects from all study procedures, drugs, and devices. Describe the amount of risk the community may be subjected to. ¨ Describe how due care will be used to minimize risks and maximize benefits. ¨ Describe the provisions for a continuing reassessment of the balance between risks and benefits. ¨ Describe the data and safety monitoring committee, if any. ¨ Describe the expected benefits for individual participants, the community, and society.

¨ Describe how adverse effects will be handled. ¨ Discuss if facilities and equipment are adequate to handle possible adverse effects. ¨ Explain who will be financially responsible for treatment of physical injuries resulting from study procedures (e.g., study sponsor, subject, organization compensation plan, etc.).

¨ Explain if data will be anonymous (no possible link to identifiers). ¨ Explain if identifiable data will be coded and if the key to the code will be kept separate from the data. ¨ Explain if any other agency or individual will have access to identifiable data. ¨ Explain how data will be protected (e.g., computer with restricted access, locked file, etc.).

¨ If the consent form is written, submit copies of all consent and assent forms for each participant group. If an oral consent or assent script will be used, submit written scripts for each group. ¨ If you will not use a consent form or script, submit written justification of waiver of consent.

¨ List all non-investigational drugs or other substances that will be used during the research. Include the name, source, dose, and method of administration. ¨ List all investigational drugs or substances to be used in the study. Include the name, source, dose, method of administration, IND number, and phase of testing. (INDs must be registered with the appropriate institutional pharmacy.) Provide a concise summary of drug information prepared by the investigator, including available toxicity data, reports of animal studies, description of studies done in humans, and drug protocol. ¨ List all investigational devices to be used. Provide the name, source, description of purpose, method, and Food and Drug Administration IDE number. If no IDE is available, explain why the device qualifies as a non-significant risk. Attach a copy of the protocol, descriptions of studies in humans and animals, and drawings or photographs of the device.

¨ Describe how materials with potential radiation risk will be used (e.g., X-rays and radioisotopes). ¨ If you will use materials with potential radiation risk, describe the status of annual review by the Radiation Safety Committee. If the annual review has been approved, attach a copy of the approval. ¨ Describe the medical, academic, or other personal records that will be used. ¨ Describe the type of audio-visual recordings, tape recordings, or photographs that will be made. ¨ Explain if the Scientific Instrument Division will test all instruments. If not, describe the safety testing procedures. ¨ Do the PI or sponsor have relevant insurance coverage? If so, state company name and policy number. This excerpt should be read in conjunction with the Guidelines. Appendix C

© 2018 |

Developing a Protocol for Systematic and Scoping Reviews

- Protocol Templates

- Making Your Protocol Available

- Additional Resources

- Related Guides

- Getting Help

What is a Protocol?

In the evidence synthesis process, the first step is determining a research question (Uman, 2011). The next step is deciding which type of review to conduct based on your research question. Before conducting the actual literature review and research, the team must develop a protocol.

The protocol of an evidence synthesis outlines the rationale, hypothesis, and methods researchers are planning to use in conducting their review (Page et. al, 2021). Protocols must be completed before the actual review is conducted, and is then used as a guide for the research team. Outlining the team's steps in the research process is not only essential for collaboration, but in establishing authorship and credibility. In order for your review to be legitimate, you must outline and justify the measures taken to search and review the relevant literature.

Once a protocol is developed, it is uploaded and shared for other researchers to review. This is done to allow for potential replication in research measures.

- Systematic Review

- Scoping Review

What is a Systematic Review?

A systematic review is a form of evidence synthesis where a comprehensive literature review relating to one specific research question is conducted (Newman & Gough, 2020). Literature reviewed includes studies, papers, essays, research, and unpublished studies. The goal is to be as comprehensive as possible and to prevent bias in literature selected. Once all of the literature is reviewed, poorly done studies are filtered and the researcher is able to make recommendations regarding future directions of research applying to the area of focus.

For more information on conducting a systematic review at Duquesne, see our Systematic Review library guide .

What is a Scoping Review?

A scoping review is a form of evidence synthesis where the author's goal is determining the scope of literature surrounding a particular area of interest (Munn et. al, 2018). This is contrary to a systematic review, which aims to gather all of the literature relating to a focused research question (Pham et. al, 2014). Also referred to as mapping, the scoping review's purpose is to amass literature in one area - what is consistent/inconsistent in the literature? What are trends in research being done in this area? What are the gaps? This is useful information to have as it informs future research.

For more information on conducting a scoping review at Duquesne, see our Scoping Review library guide .

What to Include in Your Protocol

Depending on the type of evidence synthesis you aspire to conduct, a protocol may need to follow a template. Potential requirements for these protocols include description of the following elements (Uman, 2011):

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Eligibility

- Keywords used in searches, synonyms

- Types of studies reviewed

- Examples of search terms

- Justification of how studies are being assessed

- Ways of preventing bias

- Next: Protocol Templates >>

- Last Updated: Feb 5, 2024 3:28 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.duq.edu/protocols

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 14, Issue 5

- Use of social network analysis in health research: a scoping review protocol

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Eshleen Grewal 1 ,

- Jenny Godley 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Justine Wheeler 5 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9008-2289 Karen L Tang 1 , 3 , 4

- 1 Department of Medicine , University of Calgary , Calgary , Alberta , Canada

- 2 Department of Sociology , University of Calgary , Calgary , Alberta , Canada

- 3 Department of Community Health Sciences , University of Calgary , Calgary , Alberta , Canada

- 4 O’Brien Institute for Public Health , University of Calgary , Calgary , Alberta , Canada

- 5 Libraries and Cultural Resources , University of Calgary , Calgary , Alberta , Canada

- Correspondence to Dr Karen L Tang; klktang{at}ucalgary.ca

Introduction Social networks can affect health beliefs, behaviours and outcomes through various mechanisms, including social support, social influence and information diffusion. Social network analysis (SNA), an approach which emerged from the relational perspective in social theory, has been increasingly used in health research. This paper outlines the protocol for a scoping review of literature that uses social network analytical tools to examine the effects of social connections on individual non-communicable disease and health outcomes.

Methods and analysis This scoping review will be guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for conducting scoping reviews. A search of the electronic databases, Ovid Medline, PsycINFO, EMBASE and CINAHL, will be conducted in April 2024 using terms related to SNA. Two reviewers will independently assess the titles and abstracts, then the full text, of identified studies to determine whether they meet inclusion criteria. Studies that use SNA as a tool to examine the effects of social networks on individual physical health, mental health, well-being, health behaviours, healthcare utilisation, or health-related engagement, knowledge, or trust will be included. Studies examining communicable disease prevention, transmission or outcomes will be excluded. Two reviewers will extract data from the included studies. Data will be presented in tables and figures, along with a narrative synthesis.

Ethics and dissemination This scoping review will synthesise data from articles published in peer-reviewed journals. The results of this review will map the ways in which SNA has been used in non-communicable disease health research. It will identify areas of health research where SNA has been heavily used and where future systematic reviews may be needed, as well as areas of opportunity where SNA remains a lesser-used method in exploring the relationship between social connections and health outcomes.

- Protocols & guidelines

- Social Interaction

- Social Support

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-078872

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

This is a novel scoping review that fills an important gap—how and where social network analysis (SNA) (as a data collection and analytical tool) has been used in health research has not been systematically documented despite its increasing use in the discipline.

The breadth of the scoping review allows for a comprehensive mapping of the use of SNA to examine social connections and non-communicable disease and health outcomes, without limiting to any one population group or setting.

The use of the Arksey and O’Malley framework as well as the Levac et al recommendations to guide our scoping review will ensure that a rigorous and transparent process is undertaken.

Due to the scope of the review and the large volume of anticipated studies, only published articles in the English language will be included.

Introduction

Social connections are known to influence health. 1 People with many supportive social connections tend to be healthier and live longer than people who have fewer supportive social connections, while social isolation, or the absence of supportive social connections, is associated with the deterioration of physical and psychological health, and even death. 2–5 These associations hold even when accounting for socioeconomic status and health practices. 6 Additionally, having a low quantity of supportive social connections is associated with the development or worsening of medical conditions, such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and cancer, potentially through chronic inflammation and changes to autonomic regulation and immune responses. 7–13 Unsupportive social connections can also have adverse effects on health due to emotional stress, which can then lead to poor health habits, psychological distress and negative physiological responses (eg, increased heart rate and blood pressure), all of which are detrimental to health over time. 14 The health of individuals is therefore connected to the people around them. 15

Social networks can influence health via five pathways. 15 16 First, networks can provide social support, to meet the needs of the individual. Dyadic relationships can provide informational, instrumental (ie, aid and assistance with tangible needs), appraisal (ie, help with decision-making) and/or emotional support; this support can be enhanced or hindered by the overall network structure. 17 In addition to the tangible aid and resources that are provided, social support—either perceived or actual—also has direct effects on mental health, well-being and feelings of self-efficacy. 18–20 Social support may also act as a buffer to stress. 16 19 The second pathway by which social networks influence health, and in particular health behaviours such as alcohol and cigarette use, physical activity, food intake patterns and healthcare utilisation, is through social influence. 16 21 That is, the attitudes and behaviour of individuals are guided and altered in response to other network members. 22 23 Social influence is difficult to disentangle from social selection from an empirical standpoint. That is, similarities in behaviour may be due to influences within a network, or alternatively, they may reflect the known phenomenon where individuals tend to form close connections with others who are like them. 22 24 The third pathway is through the promotion of social engagement and participation. Individuals derive a sense of identity, value and meaning through the roles they play (eg, parental roles, community roles, professional roles, etc) in their networks, and the opportunities for participation in social contexts. 16 The fourth pathway by which networks affect health is through transmission of communicable diseases through person-to-person contact. Finally, social networks overlap, resulting in differential access to resources and opportunities (eg, finances, information and jobs). 15 16 An individual’s structural position can result in differential health outcomes, similar to the inequities that stem from differences in social status. 16

There has been an explosion of literature in the area of social networks and health. In their bibliometric analysis, Chapman et al found that the number of studies that examine social networks and health has sextupled since 2000. 25 Similarly, the value of grants and contracts in this topic area, as awarded by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, has increased 10-fold. 25 A turning point in the field was the HIV epidemic, where there was an urgent need to better understand its spread. 25 The exponential rise in the number of studies since then that examine social networks and health appears to reflect a widespread understanding that an individual’s health cannot be isolated from his or her social networks and context. There is, however, significant heterogeneity in what aspect of, and how, social networks are being studied. For example, many health research studies use proxies for social connectedness such as marital status or living alone status (as these variables tend to be commonly included in health surveys), without considering the quality of those social connections, and without further exploring the broader social network and their characteristics. 16 26 These proxy measures do little to describe the structure, quantity, quality or characteristics of social connections within which individuals are embedded. Another common approach in health research is to focus on social support measures and their effects on health. Individuals are asked about perceived, or received, social support (for example, through questions that ask about the availability of people who provide emotional support, informational support and/or assistance with daily tasks, with either binary or a Likert scale of responses). 27 28 While important, social support measures do not assess the structure of social networks and represent only one of many different mechanisms by which social networks influence health. 17 23

Social network analysis