Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

Published on December 6, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on November 20, 2023.

Exploratory research is a methodology approach that investigates research questions that have not previously been studied in depth.

Exploratory research is often qualitative and primary in nature. However, a study with a large sample conducted in an exploratory manner can be quantitative as well. It is also often referred to as interpretive research or a grounded theory approach due to its flexible and open-ended nature.

Table of contents

When to use exploratory research, exploratory research questions, exploratory research data collection, step-by-step example of exploratory research, exploratory vs. explanatory research, advantages and disadvantages of exploratory research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about exploratory research.

Exploratory research is often used when the issue you’re studying is new or when the data collection process is challenging for some reason.

You can use this type of research if you have a general idea or a specific question that you want to study but there is no preexisting knowledge or paradigm with which to study it.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Exploratory research questions are designed to help you understand more about a particular topic of interest. They can help you connect ideas to understand the groundwork of your analysis without adding any preconceived notions or assumptions yet.

Here are some examples:

- What effect does using a digital notebook have on the attention span of middle schoolers?

- What factors influence mental health in undergraduates?

- What outcomes are associated with an authoritative parenting style?

- In what ways does the presence of a non-native accent affect intelligibility?

- How can the use of a grocery delivery service reduce food waste in single-person households?

Collecting information on a previously unexplored topic can be challenging. Exploratory research can help you narrow down your topic and formulate a clear hypothesis and problem statement , as well as giving you the “lay of the land” on your topic.

Data collection using exploratory research is often divided into primary and secondary research methods, with data analysis following the same model.

Primary research

In primary research, your data is collected directly from primary sources : your participants. There is a variety of ways to collect primary data.

Some examples include:

- Survey methodology: Sending a survey out to the student body asking them if they would eat vegan meals

- Focus groups: Compiling groups of 8–10 students and discussing what they think of vegan options for dining hall food

- Interviews: Interviewing students entering and exiting the dining hall, asking if they would eat vegan meals

Secondary research

In secondary research, your data is collected from preexisting primary research, such as experiments or surveys.

Some other examples include:

- Case studies : Health of an all-vegan diet

- Literature reviews : Preexisting research about students’ eating habits and how they have changed over time

- Online polls, surveys, blog posts, or interviews; social media: Have other schools done something similar?

For some subjects, it’s possible to use large- n government data, such as the decennial census or yearly American Community Survey (ACS) open-source data.

How you proceed with your exploratory research design depends on the research method you choose to collect your data. In most cases, you will follow five steps.

We’ll walk you through the steps using the following example.

Therefore, you would like to focus on improving intelligibility instead of reducing the learner’s accent.

Step 1: Identify your problem

The first step in conducting exploratory research is identifying what the problem is and whether this type of research is the right avenue for you to pursue. Remember that exploratory research is most advantageous when you are investigating a previously unexplored problem.

Step 2: Hypothesize a solution

The next step is to come up with a solution to the problem you’re investigating. Formulate a hypothetical statement to guide your research.

Step 3. Design your methodology

Next, conceptualize your data collection and data analysis methods and write them up in a research design.

Step 4: Collect and analyze data

Next, you proceed with collecting and analyzing your data so you can determine whether your preliminary results are in line with your hypothesis.

In most types of research, you should formulate your hypotheses a priori and refrain from changing them due to the increased risk of Type I errors and data integrity issues. However, in exploratory research, you are allowed to change your hypothesis based on your findings, since you are exploring a previously unexplained phenomenon that could have many explanations.

Step 5: Avenues for future research

Decide if you would like to continue studying your topic. If so, it is likely that you will need to change to another type of research. As exploratory research is often qualitative in nature, you may need to conduct quantitative research with a larger sample size to achieve more generalizable results.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

It can be easy to confuse exploratory research with explanatory research. To understand the relationship, it can help to remember that exploratory research lays the groundwork for later explanatory research.

Exploratory research investigates research questions that have not been studied in depth. The preliminary results often lay the groundwork for future analysis.

Explanatory research questions tend to start with “why” or “how”, and the goal is to explain why or how a previously studied phenomenon takes place.

Like any other research design , exploratory studies have their trade-offs: they provide a unique set of benefits but also come with downsides.

- It can be very helpful in narrowing down a challenging or nebulous problem that has not been previously studied.

- It can serve as a great guide for future research, whether your own or another researcher’s. With new and challenging research problems, adding to the body of research in the early stages can be very fulfilling.

- It is very flexible, cost-effective, and open-ended. You are free to proceed however you think is best.

Disadvantages

- It usually lacks conclusive results, and results can be biased or subjective due to a lack of preexisting knowledge on your topic.

- It’s typically not externally valid and generalizable, and it suffers from many of the challenges of qualitative research .

- Since you are not operating within an existing research paradigm, this type of research can be very labor-intensive.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Exploratory research is a methodology approach that explores research questions that have not previously been studied in depth. It is often used when the issue you’re studying is new, or the data collection process is challenging in some way.

Exploratory research aims to explore the main aspects of an under-researched problem, while explanatory research aims to explain the causes and consequences of a well-defined problem.

You can use exploratory research if you have a general idea or a specific question that you want to study but there is no preexisting knowledge or paradigm with which to study it.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, November 20). Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/exploratory-research/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, explanatory research | definition, guide, & examples, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, what is a research design | types, guide & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Methodology

- Open access

- Published: 19 October 2019

Smart literature review: a practical topic modelling approach to exploratory literature review

- Claus Boye Asmussen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2998-2293 1 &

- Charles Møller 1

Journal of Big Data volume 6 , Article number: 93 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

50k Accesses

220 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Manual exploratory literature reviews should be a thing of the past, as technology and development of machine learning methods have matured. The learning curve for using machine learning methods is rapidly declining, enabling new possibilities for all researchers. A framework is presented on how to use topic modelling on a large collection of papers for an exploratory literature review and how that can be used for a full literature review. The aim of the paper is to enable the use of topic modelling for researchers by presenting a step-by-step framework on a case and sharing a code template. The framework consists of three steps; pre-processing, topic modelling, and post-processing, where the topic model Latent Dirichlet Allocation is used. The framework enables huge amounts of papers to be reviewed in a transparent, reliable, faster, and reproducible way.

Introduction

Manual exploratory literature reviews are soon to be outdated. It is a time-consuming process, with limited processing power, resulting in a low number of papers analysed. Researchers, especially junior researchers, often need to find, organise, and understand new and unchartered research areas. As a literature review in the early stages often involves a large number of papers, the options for a researcher is either to limit the amount of papers to review a priori or review the papers by other methods. So far, the handling of large collections of papers has been structured into topics or categories by the use of coding sheets [ 2 , 12 , 22 ], dictionary or supervised learning methods [ 30 ]. The use of coding sheets has especially been used in social science, where trained humans have created impressive data collections, such as the Policy Agendas Project and the Congressional Bills Project in American politics [ 30 ]. These methods, however, have a high upfront cost of time, requiring a prior understanding where papers are grouped by categories based on pre-existing knowledge. In an exploratory phase where a general overview of research directions is needed, many researchers may be dismayed by having to spend a lot of time before seeing any results, potentially wasting efforts that could have been better spent elsewhere. With the advancement of machine learning methods, many of the issues can be dealt with at a low cost of time for the researcher. Some authors argue that when human processing such as coding practice is substituted by computer processing, reliability is increased and cost of time is reduced [ 12 , 23 , 30 ]. Supervised learning and unsupervised learning, are two methods for automatically processing papers [ 30 ]. Supervised learning relies on manually coding a training set of papers before performing an analysis, which entails a high cost of time before a result is achieved. Unsupervised learning methods, such as topic modelling, do not require the researcher to create coding sheets before an analysis, which presents a low cost of time approach for an exploratory review with a large collection of papers. Even though, topic modelling has been used to group large amounts of documents, few applications of topic modelling have been used on research papers, and a researcher is required to have programming skills and statistical knowledge to successfully conduct an exploratory literature review using topic modelling.

This paper presents a framework where topic modelling, a branch of the unsupervised methods, is used to conduct an exploratory literature review and how that can be used for a full literature review. The intention of the paper is to enable the use of topic modelling for researchers by providing a practical approach to topic modelling, where a framework is presented and used on a case step-by-step. The paper is organised as follows. The following section will review the literature in topic modelling and its use in exploratory literature reviews. The framework is presented in “ Method ” section, and the case is presented in “ Framework ” section. “ Discussion ” and “ Conclusion ” sections conclude the paper with a discussion and conclusion.

Topic modelling for exploratory literature review

While there are many ways of conducting an exploratory review, most methods require a high upfront cost of time and having pre-existent knowledge of the domain. Quinn et al. [ 30 ] investigated the costs of different text categorisation methods, a summary of which is presented in Table 1 , where the assumptions and cost of the methods are compared.

What is striking is that all of the methods, except manually reading papers and topic modelling, require pre-existing knowledge of the categories of the papers and have a high pre-analysis cost. Manually reading a large amount of papers will have a high cost of time for the researcher, whereas topic modelling can be automated, substituting the use of the researcher’s time with the use of computer time. This indicates a potentially good fit for the use of topic modelling for exploratory literature reviews.

The use of topic modelling is not new. However, there are remarkably few papers utilising the method for categorising research papers. It has been predominantly been used in the social sciences to identify concepts and subjects within a corpus of documents. An overview of applications of topic modelling is presented in Table 2 , where the type of data, topic modelling method, the use case and size of data are presented.

The papers in Table 2 analyse web content, newspaper articles, books, speeches, and, in one instance, videos, but none of the papers have applied a topic modelling method on a corpus of research papers. However, [ 27 ] address the use of LDA for researchers and argue that there are four parameters a researcher needs to deal with, namely pre-processing of text, selection of model parameters and number of topics to be generated, evaluation of reliability, and evaluation of validity. The uses of topic modelling are to identify themes or topics within a corpus of many documents, or to develop or test topic modelling methods. The motivation for most of the papers is that the use of topic modelling enables the possibility to do an analysis on a large amount of documents, as they would otherwise have not been able to due to the cost of time [ 30 ]. Most of the papers argue that LDA is a state-of-the-art and preferred method for topic modelling, which is why almost all of the papers have chosen the LDA method. The use of topic modelling does not provide a full meaning of the text but provides a good overview of the themes, which could not have been obtained otherwise [ 21 ]. DiMaggio et al. [ 12 ] find a key distinction in the use of topic modelling is that its use is more of utility than accuracy, where the model should simplify the data in an interpretable and valid way to be used for further analysis They note that a subject-matter expert is required to interpret the outcome and that the analysis is formed by the data.

The use of topic modelling presents an opportunity for researchers to add a tool to their tool box for an exploratory and literature review process. Topic modelling has mostly been used on online content and requires a high degree of statistical and technical skill, skills not all researchers possess. To enable more researchers to apply topic modelling for their exploratory literature reviews, a framework will be proposed to lower the requirements for technical and statistical skills of the researcher.

Topic modelling has proven itself as a tool for exploratory analysis of a large number of papers [ 14 , 24 ]. However, it has rarely been applied in the context of an exploratory literature review. The selected topic modelling method, for the framework, is Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), as it is the most used [ 6 , 12 , 17 , 20 , 32 ], state-of-the-art method [ 25 ] and simplest method [ 8 ]. While other topic modelling methods could be considered, the aim of this paper is to enable the use of topic modelling for researchers. For enabling topic modelling for researchers, ease of use and applicability are highly rated, where LDA is easily implemented and understood. Other topic modelling methods could potentially be used in the framework, where reviews of other topic models is presented in [ 1 , 26 ].

The topic modelling method LDA is an unsupervised, probabilistic modelling method which extracts topics from a collection of papers. A topic is defined as a distribution over a fixed vocabulary. LDA analyses the words in each paper and calculates the joint probability distribution between the observed (words in the paper) and the unobserved (the hidden structure of topics). The method uses a ‘Bag of Words’ approach where the semantics and meaning of sentences are not evaluated. Rather, the method evaluates the frequency of words. It is therefore assumed that the most frequent words within a topic will present an aboutness of the topic. As an example, if one of the topics in a paper is LEAN, then it can be assumed that the words LEAN, JIT and Kanban are more frequent, compared to other non-LEAN papers. The result is a number of topics with the most prevalent topics grouped together. A probability for each paper is calculated for each topic, creating a matrix with the size of number of topics multiplied with the number of papers. A detailed description of LDA is found in [ 6 ].

The framework is designed as a step-by-step procedure, where its use is presented in a form of a case where the code used for the analysis is shared, enabling other researchers to easily replicate the framework for their own literature review. The code is based on the open source statistical language R, but any language with the LDA method is suitable for use. The framework can be made fully automated, presenting a low cost of time approach for exploratory literature reviews. An inspiration for the automation of the framework can be found in [ 10 ], who created an online-service, towards processing Business Process Management documents where text-mining approaches such as topic modelling are automated. They find that topic modelling can be automated and argue that the use of a good tool for topic modelling can easily present good results, but the method relies on the ability of people to find the right data, guide the analytical journey and interpret the results.

The aim of the paper is to create a generic framework which can be applied in any context of an exploratory literature review and potentially be used for a full literature review. The method provided in this paper is a framework which is based upon well-known procedures for how to clean and process data, in such a way that the contribution from the framework is not in presenting new ways to process data but in how known methods are combined and used. The framework will be validated by the use of a case in the form of a literature review. The outcome of the method is a list of topics where papers are grouped. If the grouping of papers makes sense and is logical, which can be evaluated by an expert within the research field, then the framework is deemed valid. Compared to other methods, such as supervised learning, the method of measuring validity does not produce an exact degree of validity. However, invalid results will likely be easily identifiable by an expert within the field. As stated by [ 12 ], the use of topic modelling is more for utility than for accuracy.

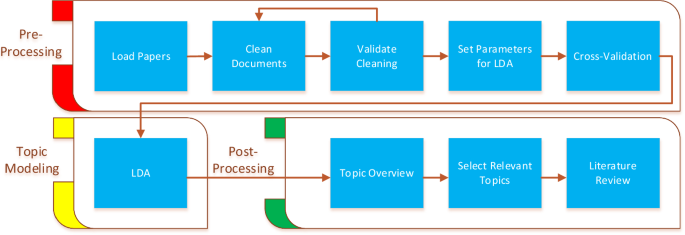

The developed framework is illustrated in Fig. 1 , and the R-code and case output files are located at https://github.com/clausba/Smart-Literature-Review . The smart literature review process consists of the three steps: pre-processing, topic modelling, and post-processing.

Process overview of the smart literature review framework

The pre-processing steps are getting the data and model ready to run, where the topic-modelling step is executing the LDA method. The post-processing steps are translating the outcome of the LDA model to an exploratory review and using that to identify papers to be used for a literature review. It is assumed that the papers for review are downloaded and available, as a library with the pdf files.

Pre-processing

The pre-processing steps consist of loading and preparing the papers for processing, an essential step for a good analytical result. The first step is to load the papers into the R environment. The next step is to clean the papers by removing or altering non-value-adding words. All words are converted to lower case, and punctuation and whitespaces are removed. Special characters, URLs, and emails are removed, as they often do not contribute to identification of topics. Stop words, misread words and other non-semantic contributing words are removed. Examples of stop words are “can”, “use”, and “make”. These words add no value to the aboutness of a topic. The loading of papers into R can in some instances cause words to be misread, which must either be rectified or removed. Further, some websites add a first page with general information, and these contain words that must be removed. This prevents unwanted correlation between papers downloaded from the same source. Words are stemmed to their root form for easier comparison. Lastly, many words only occur in a single paper, and these should be removed to make computations easier, as less frequent words will likely provide little benefit in grouping papers into topics.

The cleansing process is often an iterative process, as it can be difficult to identify all misread and non-value adding-words a priori. Different papers’ corpora contain different words, which means that an identical cleaning process cannot be guaranteed if a new exploratory review is conducted. As an example, different non-value-adding words exist for the medical field compared to sociology or supply chain management (SCM). The cleaning process is finished once the loaded papers mainly contain value-adding words. There is no known way to scientifically evaluate when the cleaning process is finished, which in some instances makes the cleaning process more of an art than science. However, if a researcher is technically inclined methods, provided in the preText R-package can aid in making a better cleaning process [ 11 ].

LDA is an unsupervised method, which means we do not, prior to the model being executed, know the relationship between the papers. A key aspect of LDA is to group papers into a fixed number of topics, which must be given as a parameter when executing LDA. A key process is therefore to estimate the optimal number of topics. To estimate the number of topics, a cross-validation method is used to calculate the perplexity, as used in information theory, and it is a metric used to evaluate language models, where a low score indicates a better generalisation model, as done by [ 7 , 31 , 32 ]. Lowering the perplexity score is identical to maximising the overall probability of papers being in a topic. Next, test and training datasets are created: the LDA algorithm is run on the training set, and the test set is used to validate the results. The criteria for selecting the right number of topics is to find the balance between a useable number of topics and, at the same time, to keep the perplexity as low as possible. The right number of topics can differ greatly, depending on the aim of the analysis. As a rule of thumb, a low number of topics is used for a general overview and a higher number of topics is used for a more detailed view.

The cross-validation step is used to make sure that a result from an analysis is reliable, by running the LDA method several times under different conditions. Most of the parameters set for the cross-validation should have the same value, as in the final topic modelling run. However, due to computational reasons, some parameters can be altered to lower the amount of computation to save time. As with the number of topics, there is no right way to set the parameters, indicating a trial-and-error process. Most of the LDA implementations have default values set, but in this paper’s case the following parameters were changed: burn-in time, number of iterations, seed values, number of folds, and distribution between training and test sets.

- Topic modelling

Once the papers have been cleaned and a decision has been made on the number of topics, the LDA method can be run. The same parameters as used in the cross-validation should be used as a guidance but for more precise results, parameters can be changed such as a higher number of iterations. The number of folds should be removed, as we do not need a test set, as all papers will be used to run the model. The outcome of the model is a list of papers, a list of probabilities for each paper for each topic, and a list of the most frequent words for each topic.

If an update to the analysis is needed, new papers simply have to be loaded and the post-processing and topic modelling steps can be re-run without any alterations to the parameters. Thus, the framework enables an easy path for updating an exploratory review.

Post-processing

The aim of the post-processing steps is to identify and label research topics and topics relevant for use in a literature review. An outcome of the LDA model is a list of topic probabilities for each paper. The list is used to assign a paper to a topic by sorting the list by highest probability for each paper for each topic. By assigning the papers to the topics with the highest probability, all of the topics contain papers that are similar to each other. When all of the papers have been distributed into their selected topics, the topics need to be labelled. The labelling of the topics is found by identifying the main topic of each topic group, as done in [ 17 ]. Naturally, this is a subjective matter, which can provide different labelling of topics depending on the researcher. To lower the risk of wrongly identified topics, a combination of reviewing the most frequent words for each topic and a title review is used. After the topics have been labelled, the exploratory search is finished.

When the exploratory search has finished, the results must be validated. There are three ways to validate the results of an LDA model, namely statistical, semantic, or predictive [ 12 ]. Statistical validation uses statistical methods to test the assumptions of the model. An example is [ 28 ], where a Bayesian approach is used to estimate the fit of papers to topics. Semantic validation is used to compare the results of the LDA method with expert reasoning, where the results must make semantic sense. In other words, does the grouping of papers into a topic make sense, which ideally should be evaluated by an expert. An example is [ 18 ], who utilises hand coding of papers and compare the coding of papers to the outcome of an LDA model. Predictive validation is used if an external incident can be correlated with an event not found in the papers. An example is in politics where external events, such as presidential elections which should have an impact on e.g. press releases or newspaper coverage, can be used to create a predictive model [ 12 , 17 ].

The chosen method for validation in this framework is semantic validation. The reason is that a researcher will often be or have access to an expert who can quickly validate if the grouping of papers into topics makes sense or not. Statistical validation is a good way to validate the results. However, it would require high statistical skills from the researchers, which cannot be assumed. Predictive validation is used in cases where external events can be used to predict the outcome of the model, which is seldom the case in an exploratory literature review.

It should be noted that, in contrast to many other machine learning methods, it is not possible to calculate a specific measure such as the F-measure or RMSE. To be able to calculate such measures, there must exist a correct grouping of papers, which in this instance would often mean comparing the results to manually created coding sheets [ 11 , 19 , 20 , 30 ]. However, it is very rare that coding sheets are available, leaving the semantic validation approach as the preferred validation method. The validation process in the proposed framework is two-fold. Firstly, the title of the individual paper must be reviewed to validate that each paper does indeed belong in its respective topic. As LDA is an unsupervised method, it can be assumed that not all papers will have a perfect fit within each topic, but if the majority of papers are within the theme of the topic, it is evaluated to be a valid result. If the objective of the research is only an exploratory literature review, the validation ends here. However, if a full literature review is conducted, the literature review can be viewed as an extended semantic validation method. By reviewing the papers in detail within the selected topics of research, it can be validated if the vast majority of papers belong together.

Using the results from the exploratory literature review for a full literature review is simple, as all topics from the exploratory literature review will be labelled. To conduct the full literature review, select the relevant topics and conduct the literature review on the selected papers.

To validate the framework, a case will be presented, where the framework is used to conduct a literature review. The literature review is conducted in the intersection of the research fields analytics, SCM, and enterprise information systems [ 3 ]. As the research areas have a rapidly growing interest, it was assumed that the number of papers would be large, and that an exploratory review was needed to identify the research directions within the research fields. The case used broadly defined keywords for searching for papers, ensuring to include as many potentially relevant papers as possible. Six hundred and fifty papers were found, which were heavily reduced by the use of the smart literature review framework to 76 papers, resulting in a successful literature review. The amount of papers is evaluated to be too time-consuming for a manual exploratory review, which provides a good case to test the smart literature review framework. The steps and thoughts behind the use of the framework are presented in this case section.

The first step was to load the 650 papers into the R environment. Next, all words were converted to lowercase and punctuation, whitespaces, email addresses, and URLs were removed. Problematic words were identified, such as words incorrectly read from the papers. Words included in a publisher’s information page were removed, as they add no semantic value to the topic of a paper. English stop words were removed, and all words were stemmed. As a part of an iterative process, several papers were investigated to evaluate the progress of cleaning the papers. The investigations were done by displaying words in a console window and manually evaluating if more cleaning had to be done.

After the cleaning steps, 256,747 unique words remained in the paper corpus. This is a large number of unique words, which for computational reasons is beneficial to reduce. Therefore, all words that did not have a sparsity or likelihood of 99% to be in any paper were removed. The operation lowered the amount of unique words to 14,145, greatly reducing the computational needs. The LDA method will be applied on the basis of the 14,145 unique words for the 650 papers. Several papers were manually reviewed, and it was evaluated that removal of the unique words did not significantly worsen the ability to identify main topics of the paper corpus.

The last step of pre-processing is to identify the optimal number of topics. To approximate the optimal number of topics, two things were considered. The perplexity was calculated for different amounts of topics, and secondly the need for specificity was considered.

At the extremes, choosing one topic would indicate one topic covering all papers, which will provide a very coarse view of the papers. On the other hand, if the number of topics is equal to the number of papers, then a very precise topic description will be achieved, although the topics will lose practical use as the overview of topics will be too complex. Therefore, a low number of topics was preferred as a general overview was required. Identifying what is a low number of topics will differ depending on the corpus of papers, but visualising the perplexity can often provide the necessary aid for the decision.

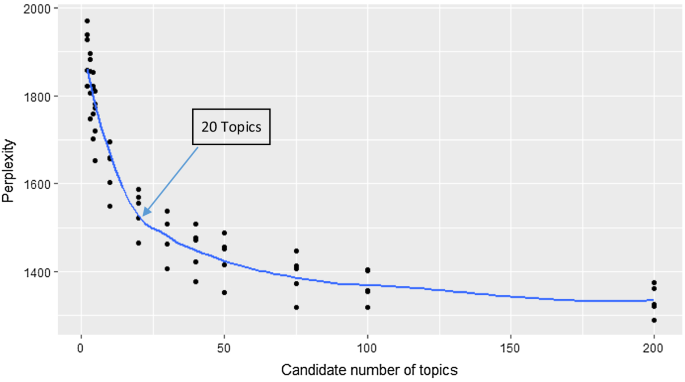

The perplexity was calculated over five folds, where each fold would identify 75% of the papers for training the model and leave out the remaining 25% for testing purposes. Using multiple folds reduces the variability of the model, ensuring higher reliability and reducing the risk of overfitting. For replicability purposes, specific seed values were set. Lastly, the number of topics to evaluate is selected. In this case, the following amounts of topics were selected: 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 75, 100, and 200. The perplexity method in the ‘topicmodels’ R library is used, where the specific parameters can be found in the provided code.

The calculations were done over two runs. However, there is no practical reason for not running the calculations in one run. The first run included all values of number of topics below 100, and the second run calculated the perplexity for 100 and 200 number of topics. The runtimes for the calculations were respectively 9 and 10 h on a standard issue laptop. The combined results are presented in Fig. 2 , and the converged results can be found in the shared repository.

5-Fold cross-validation of topic modelling. Results of cross-validation

The goal in this case is to find the lowest number of topics, which at the same time have a low perplexity. In this case, the slope of the fitted line starts to gradually decline at twenty topics, which is why the selected number of topics is twenty.

Case: topic modelling

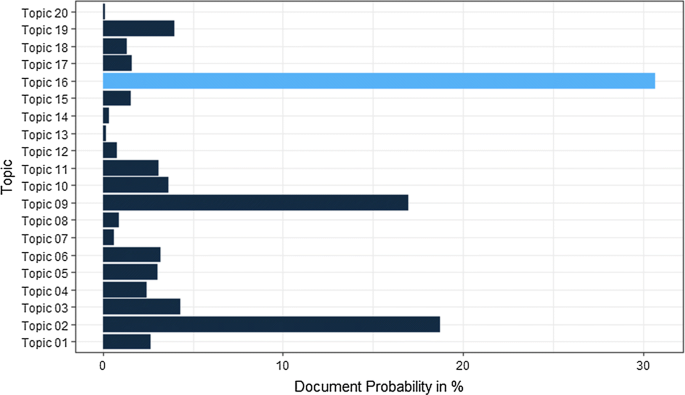

As the number of topics is chosen, the next step is to run the LDA method on the entire set of papers. The full run of 650 papers for 20 topics took 3.5 h to compute on a standard issue laptop. An outcome of the method is a 650 by 20 matrix of topic probabilities. In this case, the papers with the highest probability for each topic were used to allocate the papers. The allocation of papers to topics was done in Microsoft Excel. An example of how a distribution of probabilities is distributed across topics for a specific paper is depicted in Fig. 3 . Some papers have topic probability values close to each other, which could indicate a paper belonging to an intersection between two or more topics. These cases were not considered, and the topic with the highest probability was selected.

Example of probability distribution for one document (Topic 16 selected)

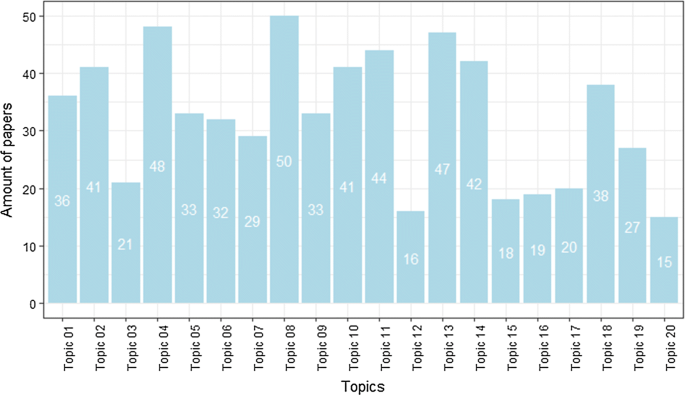

The allocation of papers to topics resulted in the distribution depicted in Fig. 4 . As can be seen, the number of papers varies for each topic, indicating that some research areas have more publications than others do.

Distribution of papers per topic

Next step is to process the findings and find an adequate description of the topics. A combination of reviewing the most frequent words and a title review was used to identify the topic names. Practically, all of the paper titles and the most frequent words for each topic, were transferred to a separate Excel spreadsheet, providing an easy overview of paper titles. An example for topic 17 can be seen in Table 3 . The most frequent words for the papers in topic 17 are “data”, “big” and “analyt”. Many of the paper titles also indicate usage of big data and analytics for application in a business setting. The topic is named “Big Data Analytics”.

The process was repeated for all other topics. The names of the topics are presented in Tables 4 and 5 .

Based on the names of the topics, three topics were selected based on relevancy for the literature review. Topics 5, 13, and 17 were selected, with a total of 99 papers. In this specific case, it was deemed that there might be papers with a sub-topic that is not relevant for the literature review. Therefore, an abstract review was conducted for the 99 papers, creating 10 sub-topics, which are presented in Table 6 .

The sub-topics RFID, Analytical Methods, Performance Management, and Evaluation and Selection of IT Systems were evaluated to not be relevant for the literature review. Seventy-six papers remained, grouped by sub-topics.

The outcome of the case was an overview of the research areas within the paper corpus, represented by the twenty topics and the ten sub-topics. The selected sub-topics were used to conduct a literature review. The validation of the framework consisted of two parts. The first part addressed the question of whether the grouping of papers, evaluated by the title and keywords, makes sense and the second part addressed whether the literature review revealed any misplaced papers. The framework did successfully place the selected papers into groups of papers that resemble each other. There was only one case where a paper was misplaced, namely that a paper about material informatics was placed among the papers in the sub-topic EIS and Analytics. The grouping and selection of papers in the literature review, based on the framework, did make semantic sense and was successfully used for a literature review. The framework has proven its utility in enabling a faster and more comprehensive exploratory literature review, as compared to competing methods. The framework has increased the speed for analysing a large amount of papers, as well as having increased the reliability in comparison with manual reviews as the same result can be obtained by running the analysis once again. The transparency in the framework is higher than in competing methods, as all steps of the framework are recorded in the code and output files.

This paper presents an approach not often found in academia, by using machine learning to explore papers to identify research directions. Even though the framework has its limitations, the results and ease of use leave a promising future for topic-modelling-based exploratory literature reviews.

The main benefit of the framework is that it provides information about a large number of papers, with little effort on the researcher’s part, before time-costly manual work is to be done. It is possible, by the use of the framework, to quickly navigate many different paper corpora and evaluate where the researchers’ time and focus should be spent. This is especially valuable for a junior researcher or a researcher with little prior knowledge of a research field. If default parameters and cleaning settings can be found for the steps in the framework, a fully automatic grouping of papers could be enabled, where very little work has to be done to achieve an overview of research directions. From a literature review perspective, the benefit of using the framework is that the decision to include or exclude papers for a literature review will be postponed to a later stage where more information is provided, resulting in a more informed decision-making process. The framework enables reproducibility, as all of the steps in the exploratory review process can be reproduced, and enables a higher degree of transparency than competing methods do, as the entire review process can, in detail, be evaluated by other researchers.

There is practically no limit of the number of papers the framework is able to process, which could enable new practices for exploratory literature reviews. An example is to use the framework to track the development of a research field, by running the topic modelling script frequently or when new papers are published. This is especially potent if new papers are automatically downloaded, enabling a fully automatic exploratory literature review. For example, if an exploratory review was conducted once, the review could be updated constantly whenever new publications are made, grouping the publications into the related topics. For this, the topic model has to be trained properly for the selected collection of papers, where it can be assumed that minor additions of papers would likely not warrant any changes to the selected parameters of the model. However, as time passes and more papers are processed, the model will learn more about the collection of papers and provide a more accurate and updated result. Having an automated process could also enable a faster and more reliable method to do post-processing of the results, reducing the post-analysis cost identified for topic modelling by [ 30 ], from moderate to low.

The framework is designed to be easily used by other researchers by designing the framework to require less technical knowledge than a normal topic model usage would entail and by sharing the code used in the case work. The framework is designed as a step-by-step approach, which makes the framework more approachable. However, the framework has yet not been used by other researchers, which would provide valuable lessons for evaluating if the learning curve needs to be lowered even further for researchers to successfully use the framework.

There are, however, considerations that must be addressed when using the smart literature review framework. Finding the optimal number of topics can be quite difficult, and the proposed method of cross-validation based on the perplexity presented a good, but not optimal, solution. An indication of why the number of selected topics is not optimal is the fact that it was not possible to identify a unifying topic label for two of the topics. Namely topics 12 and 20, which were both labelled miscellaneous. The current solution to this issue is to evaluate the relevancy of every single paper of the topics that cannot be labelled. However, in future iterations of the framework, a better identification of the number of topics must be developed. This is a notion also recognised by [ 6 ], who requested that researchers should find a way to label and assign papers to a topic other than identifying the most frequent words. An attempt was made by [ 17 ] to generate automatic labelling on press releases, but it is uncertain if the method will work in other instances. Overall, the grouping of papers in the presented case into topics generally made semantic sense, where a topic label could be found for the majority of topics.

A consideration when using the framework is that not all steps have been clearly defined, and, e.g., the cleaning step is more of an art than science. If a researcher has no or little experience in coding or executing analytical models, suboptimal results could occur. [ 11 , 25 , 27 ] find that especially the pre-processing steps can have a great impact on the validity of results, which further emphasises the importance of selecting model parameters. However, it is found that the default parameters and cleaning steps set in the code provided a sufficiently valid and useable result for an exploratory literature analysis. Running the code will not take much of the researcher’s time, as the execution of code is mainly machine time, and verifying the results takes a limited amount of a researcher time.

Due to the semantic validation method used in the framework, it relies on the availability of a domain expert. The domain expert will not only validate if the grouping of papers into topics makes sense, but it is also their responsibility to label the topics [ 12 ]. If a domain expert is not available, it could lead to wrongly labelled topics and a non-valid result.

A key issue with topic modelling is that a paper can be placed in several related topics, depending on the selected seed value. The seed value will change the starting point of the topic modelling, which could result in another grouping of papers. A paper consists of several sub-topics and depending on how the different sub-topics are evaluated, papers can be allocated to different topics. A way to deal with this issue is to investigate papers with topic probabilities close to each other. Potential wrongly assigned papers can be identified and manually moved if deemed necessary. However, this presents a less automatic way of processing the papers, where future research should aim to improve the assignments of papers to topics or create a method to provide an overview of potentially misplaced papers. It should be noted that even though some papers can be misplaced, the framework provides outcome files than can easily be viewed to identify misplaced papers, by a manual review.

As the smart literature review framework heavily relies on topic modelling, improvements to the selected topic model will likely present better results. The results of the LDA method have provided good results, but more accurate results could be achieved if the semantic meaning of the words would be considered. The framework has only been tested on academic papers, but there is no technical reason to not include other types of documents. An example is to use the framework in a business context to analyse meeting minutes notes to analyse the discussion within the different departments in a company. For this to work, the cleaning parameters would likely have to change, and another evaluation method other than a literature review would be applicable. Further, the applicability of the framework has to be assessed on other streams of literature to be certain of its use for exploratory literature reviews at large.

This paper aimed to create a framework to enable researchers to use topic modelling to, do an exploratory literature review, decreasing the need for manually reading papers and, enabling the possibility to analyse a greater, almost unlimited, amount of papers, faster, more transparently and with greater reliability. The framework is based upon the use of the topic model Latent Dirichlet Allocation, which groups related papers into topic groups. The framework provides greater reliability than competing exploratory review methods provide, as the code can be rerun on the same papers, which will provide identical results. The process is highly transparent, as most decisions made by the researcher can be reviewed by other researchers, unlike, e.g., in the creation of coding sheets. The framework consists of three main phases: Pre-processing, Topic Modelling, and Post-Processing. In the pre-processing stage, papers are loaded, cleaned, and cross-validated, where recommendations to parameter settings are provided in the case work, as well as in the accompanied code. The topic modelling step is where the LDA method is executed, using the parameters identified in the pre-processing step. The post-processing step creates outputs from the topic model and addresses how validity can be ensured and how the exploratory literature review can be used for a full literature review. The framework was successfully used in a case with 650 papers, which was processed quickly, with little time investment from the researcher. Less than 2 days was used to process the 650 papers and group them into twenty research areas, with the use of a standard laptop. The results of the case are used in the literature review by [ 3 ].

The framework is seen to be especially relevant for junior researchers, as they often need an overview of different research fields, with little pre-existing knowledge, where the framework can enable researchers to review more papers, more frequently.

For an improved framework, two main areas need to be addressed. Firstly, the proposed framework needs to be applied by other researchers on other research fields to gain knowledge about the practicality and gain ideas for further development of the framework. Secondly, research in how to automatically identity model parameters could greatly improve the usability for the use of topic modelling for non-technical researchers, as the selection of model parameters has a great impact on the result of the framework.

Availability of data and materials

https://github.com/clausba/Smart-Literature-Review (No data).

Abbreviations

- Latent Dirichlet Allocation

supply chain management

Alghamdi R, Alfalqi K. A survey of topic modeling in text mining. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2015;6(1):7. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2015.060121 .

Article Google Scholar

Ansolabehere S, Snowberg EC, Snyder JM. Statistical bias in newspaper reporting on campaign finance. Public Opin Quart. 2003. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.463780 .

Asmussen CB, Møller C. Enabling supply chain analytics for enterprise information systems: a topic modelling literature review. Enterprise Information Syst. 2019. (Submitted To) .

Atteveldt W, Welbers K, Jacobi C, Vliegenthart R. LDA models topics… But what are “topics”? In: Big data in the social sciences workshop. 2015. http://vanatteveldt.com/wp-content/uploads/2014_vanatteveldt_glasgowbigdata_topics.pdf .

Baum D. Recognising speakers from the topics they talk about. Speech Commun. 2012;54(10):1132–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2012.06.003 .

Blei DM. Probabilistic topic models. Commun ACM. 2012;55(4):77–84. https://doi.org/10.1145/2133806.2133826 .

Blei DM, Lafferty JD. A correlated topic model of science. Ann Appl Stat. 2007;1(1):17–35. https://doi.org/10.1214/07-AOAS114 .

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J Mach Learn Res. 2003;3:993–1022. https://doi.org/10.5555/944919.944937 .

Article MATH Google Scholar

Bonilla T, Grimmer J. Elevated threat levels and decreased expectations: how democracy handles terrorist threats. Poetics. 2013;41(6):650–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.06.003 .

Brocke JV, Mueller O, Debortoli S. The power of text-mining in business process management. BPTrends.

Denny MJ, Spirling A. Text preprocessing for unsupervised learning: why it matters, when it misleads, and what to do about it. Polit Anal. 2018;26(2):168–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2017.44 .

DiMaggio P, Nag M, Blei D. Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: application to newspaper coverage of U.S. government arts funding. Poetics. 2013;41(6):570–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.004 .

Elgesem D, Feinerer I, Steskal L. Bloggers’ responses to the Snowden affair: combining automated and manual methods in the analysis of news blogging. Computer Supported Cooperative Work: CSCW. Int J. 2016;25(2–3):167–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-016-9251-z .

Elgesem D, Steskal L, Diakopoulos N. Structure and content of the discourse on climate change in the blogosphere: the big picture. Environ Commun. 2015;9(2):169–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2014.983536 .

Evans MS. A computational approach to qualitative analysis in large textual datasets. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087908 .

Ghosh D, Guha R. What are we “tweeting” about obesity? Mapping tweets with topic modeling and geographic information system. Cartogr Geogr Inform Sci. 2013;40(2):90–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230406.2013.776210 .

Grimmer J. A Bayesian hierarchical topic model for political texts: measuring expressed agendas in senate press releases. Polit Anal. 2010;18(1):1–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpp034 .

Grimmer J, Stewart BM. Text as data: the promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Polit Anal. 2013;21(03):267–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028 .

Guo L, Vargo CJ, Pan Z, Ding W, Ishwar P. Big social data analytics in journalism and mass communication. J Mass Commun Quart. 2016;93(2):332–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016639231 .

Jacobi C, Van Atteveldt W, Welbers K. Quantitative analysis of large amounts of journalistic texts using topic modelling. Digit J. 2016;4(1):89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2015.1093271 .

Jockers ML, Mimno D. Significant themes in 19th-century literature. Poetics. 2013;41(6):750–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.005 .

Jones BD, Baumgartner FR. The politics of attention: how government prioritizes problems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005.

Google Scholar

King G, Lowe W. An automated information extraction tool for international conflict data with performance as good as human coders: a rare events evaluation design. Int Org. 2008;57:617–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818303573064 .

Koltsova O, Koltcov S. Mapping the public agenda with topic modeling: the case of the Russian LiveJournal. Policy Internet. 2013;5(2):207–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/1944-2866.POI331 .

Lancichinetti A, Irmak Sirer M, Wang JX, Acuna D, Körding K, Amaral LA. High-reproducibility and high-accuracy method for automated topic classification. Phys Rev X. 2015;5(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.5.011007 .

Mahmood A. Literature survey on topic modeling. Technical Report, Dept. of CIS, University of Delaware Newark, Delaware. http://www.eecis.udel.edu/~vijay/fall13/snlp/lit-survey/TopicModeling-ASM.pdf . 2009.

Maier D, Waldherr A, Miltner P, Wiedemann G, Niekler A, Keinert A, Adam S. Applying LDA topic modeling in communication research: toward a valid and reliable methodology. Commun Methods Meas. 2018;12(2–3):93–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2018.1430754 .

Mimno D, Blei DM. Bayesian checking for topic models. In: EMLP 11 proceedings of the conference on empirical methods in natural language processing. 2011. p 227–37. https://doi.org/10.5555/2145432.2145459

Parra D, Trattner C, Gómez D, Hurtado M, Wen X, Lin YR. Twitter in academic events: a study of temporal usage, communication, sentimental and topical patterns in 16 Computer Science conferences. Comput Commun. 2016;73:301–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2015.07.001 .

Quinn KM, Monroe BL, Colaresi M, Crespin MH, Radev DR. How to analyze political attention. Am J Polit Sci. 2010;54(1):209–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00427.x .

Xu Z, Raschid L. Probabilistic financial community models with Latent Dirichlet Allocation for financial supply chains. In: DSMM’16 proceedings of the second international workshop on data science for macro-modeling. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1145/2951894.2951900 .

Zhao W, Chen JJ, Perkins R, Liu Z, Ge W, Ding Y, Zou W. A heuristic approach to determine an appropriate number of topics in topic modeling. BMC Bioinform. 2015;16(13):S8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-16-S13-S8 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Materials and Production, Center for Industrial Production, Aalborg University, Fibigerstræde 16, 9220, Aalborg Øst, Denmark

Claus Boye Asmussen & Charles Møller

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CBA wrote the paper, developed the framework and executed the case. CM Supervised the research and developed the framework. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Claus Boye Asmussen .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Asmussen, C.B., Møller, C. Smart literature review: a practical topic modelling approach to exploratory literature review. J Big Data 6 , 93 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0255-7

Download citation

Received : 26 July 2019

Accepted : 02 October 2019

Published : 19 October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0255-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Supply chain management

- Automatic literature review

A systematic exploration of scoping and mapping literature reviews

- Brief Report

- Open access

- Published: 23 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Eirini Christou ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6928-1013 1 ,

- Antigoni Parmaxi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0687-0176 1 &

- Panayiotis Zaphiris ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8112-5099 1

1314 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Systematic literature mapping can help researchers identify gaps in the research and provide a comprehensive overview of the available evidence. Despite the importance and benefits of conducting systematic scoping and mapping reviews, many researchers may not be familiar with the methods and best practices for conducting these types of reviews. This paper aims to address this gap by providing a step-by-step guide to conducting a systematic scoping or mapping review, drawing on examples from different fields. This study adopts a systematic literature review approach aiming to identify and present the steps of conducting scoping and mapping literature reviews and serves as a guide on conducting scoping or mapping systematic literature reviews. A number of 90 studies were included in this study. The findings describe the steps to follow when conducting scoping and mapping reviews and suggest the integration of the card sorting method as part of the process. The proposed steps for undertaking scoping and mapping reviews presented in this manuscript, highlight the importance of following a rigorous approach for conducting scoping or mapping reviews.

Similar content being viewed by others

A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews.

How methodological frameworks are being developed: evidence from a scoping review

Literature Reviews: An Overview of Systematic, Integrated, and Scoping Reviews

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

An essential component of academic research is literature review. A systematic literature review, also known as a systematic review, is a method for locating, assessing, and interpreting all research related to a specific research question, topic, or phenomenon of interest [ 1 ].

Scoping and mapping reviews are variations of systematic literature mapping [ 2 ]. Both mapping and scoping reviews can help researchers to understand the scope and breadth of the literature in a given field, identify gaps in the research, and provide a comprehensive overview of the available evidence. Systematic literature mapping purposely focuses on a narrower but more general academic or policy issue and does not try to synthesize the results of research to address a particular subject. The scoping review is exploratory in nature, whereas the mapping review can be conclusive in describing the available evidence and identifying gaps. Mapping review includes a thorough, systematic search of a wide field. It identifies the body of literature that is currently available on a subject and points out any glaring gaps in the evidence [ 3 ].

1.1 Rationale

Despite the importance and benefits of conducting systematic scoping and mapping reviews, many researchers may not be familiar with the methods and best practices for conducting these types of reviews. This paper aims to address this gap by providing a step-by-step guide to conducting a systematic scoping or mapping review, drawing on examples from different fields.

This study adopts a systematic literature review approach aiming to identify and present the differences and the steps of conducting scoping and mapping literature review. The paper provides practical guidance on how to address common challenges in conducting systematic scoping or mapping reviews, such as dealing with the volume of studies identified, managing the data extraction and synthesis process, and ensuring rigor and reproducibility in the review methodology. The main research questions that guide this study are:

RQ1: What is a systematic scoping review and how is it conducted?

RQ2: What is a systematic mapping review and how is it conducted?

RQ3: What are the main differences between systematic scoping and systematic mapping reviews?

Overall, this paper will be a valuable resource for researchers who are interested in conducting a systematic scoping or mapping review. By providing clear guidance and practical examples, the paper aims to promote best practices in systematic scoping and mapping review methodology. The study is organized as follows: The following section presents the methodology of the study, followed by the results showing the process of the scoping and mapping literature review and presenting some examples. Finally, suggestions on how to plan and perform a quality scoping and mapping review are presented.

2 Methodology

The methodology of this paper was adopted by Xiao and Watson [ 4 ].

2.1 Literature search

The search was conducted in two well-known online databases, Web of Science and EBSCOHost, across various disciplines. The searched terms combined keywords related to the performance of scoping and mapping literature review, such as “systematic literature review”, “methodology”, “map”, “mapping” and “scoping”. The title of each manuscript was used to determine its initial relevance. If the content of the title suggested that it would explain the method of the literature review process, we obtained the full reference, which included the author, year, title, and abstract, for additional analysis.

2.2 Initial search results

The query string used for the database search is the following: systematic literature review AND methodology AND (“map” OR “mapping” OR “scoping”). Abstract search was conducted in both databases for the last 10 years (2013–2022). A search on EBSCOHost revealed 643 results of which 291 were duplicated and automatically removed. After applying the database filters to limit the articles to peer-reviewed academic journal articles written in English, a number of 102 papers were excluded. Additional 109 papers were duplicated and removed manually. After an initial screening of the titles, a total of 13 studies were identified as relevant to the methodology of the scoping and mapping literature review. A search on Web of Science, revealed 888 results of which 9 were duplicate and removed, and 157 were found to be related to the methodology of scoping or mapping literature reviews after the first title screening. Last search was conducted on the 2nd of November 2022. Both sources revealed 161 related studies, excluding 9 duplicates that were removed.

2.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Only studies that provide instructions on how to perform a scoping or mapping review were included in this paper. Reviews of the literature on certain subjects and in languages other than English were excluded. The study is limited to papers published within the last 10 years, aiming to collect recent information for performing scoping or mapping reviews. Inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Table 1 .

2.4 Screening

To further assess the 161 studies’ applicability to the study topic, their abstracts were reviewed. The manuscripts were evaluated independently and in parallel by two researchers. The researchers’ differing opinions were discussed and settled. Then the full-text of a total of 20 studies was acquired for quality evaluation.

2.5 Eligibility and quality evaluation

To further assess the quality and relevance of the studies, the full-text papers were reviewed. Journal articles and books published by prominent publishers were included in the review as they contained high-quality research. Because there is no peer review procedure, the majority of technical reports and online presentations were excluded.

Two researchers worked independently and simultaneously on evaluating eligibility and quality. Any disagreements between them were discussed and resolved. A total of ten (10) studies were excluded after careful review: one study was excluded because it lacked instructions on how the scoping or mapping review methodology was conducted, three studies were excluded because the methodology was not related to scoping or mapping review, while five studies were disregarded because they focused on a particular subject. One of the studies’ full text couldn’t be accessed. This resulted in ten (10) eligible for full-text analysis.

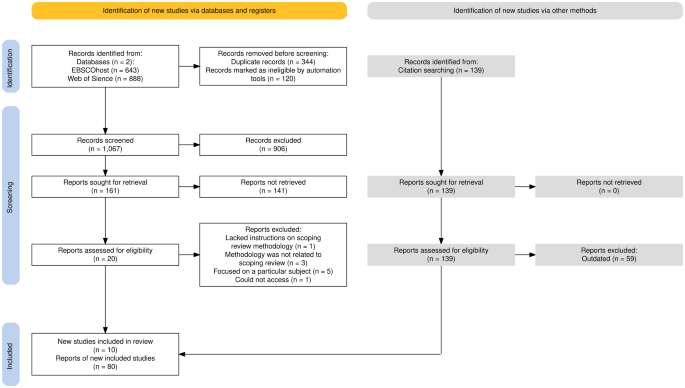

2.6 Iterations

Through backward and forward searching, additional 18 studies were discovered, from which only 10 met the inclusion criteria. The forward and backward search was also used to find manuscripts that applied scoping or mapping literature review methodology. After finding the article that established the scoping or mapping review methodology, articles that had cited the methodology paper to find instances of best practices in different fields were searched. Following consideration of examples’ adherence to the methodology, preference was given to planning-related articles. In total, 90 studies were analyzed in this study, i.e. 10 methodological papers that describe the application of scoping or mapping review, as well as 80 papers that demonstrate the application of the scoping and mapping methodology in different fields, that are used as examples. The PRISMA flow diagram (see Fig. 1 ) depicts the process of the search strategy [ 5 ].

PRISMA flow diagram

2.7 Extraction and analysis of data

Data were extracted in the process of scoping literature reviews, including information with regards to formulating the problem, establishing and validating the review procedure, searching the literature, screening for inclusion, evaluating quality, extracting data, analyzing and synthesizing data, and reporting the findings (Xiao & Watson, 2019). NVivo software was used for all data extraction and coding procedures. Initially, two researchers each took information from articles for cross-checking. The two researchers reached an agreement on what to extract from the publications after reviewing a few articles together. Then the first author classified the data based on the research questions.

In this section we present the findings of our review.

3.1 Defining “Scoping” and “mapping” review

According to [ 2 ], scoping and mapping reviews are variations of systematic literature mapping that focus on narrower but more general academic or policy issues. A scoping review is exploratory in nature, seeking to identify the nature and extent of research on a particular topic, and can be used to identify gaps in the literature. An example of a research question suitable for a scoping review is “What engagement strategies do educators use in classroom settings to facilitate teaching and learning of diverse students in undergraduate nursing programs?“ [ 6 ]. A mapping review, on the other hand, is a thorough and systematic search of a wide field of literature that aims to identify the body of literature currently available on a subject and point out any glaring gaps in the evidence. An example of a research question suitable for a mapping review is “What are the currently available animal models for cystic fibrosis” [ 3 ]. Overall, each type of review has its own specific aims and can be useful for different types of research questions.

3.1.1 Defining scoping review

There is no single definition for scoping reviews in the literature. According to [ 7 ], scoping review is a type of knowledge synthesis that uses a systematic process to map the evidence on a subject and identify key ideas, theories, sources, and knowledge gaps. The goal of a scoping review is to include all relevant information that is available, including ‘grey’ literature, which includes unpublished research findings, therefore including all available literature and evidence, but the reviewers can decide what type of publications they would like to include [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ].

Scoping review process is sometimes used as a preliminary step before a systematic literature review, in cases where the topic or research area in focus has not yet been extensively reviewed or is complicated or heterogeneous in nature and the types of evidence available remain unclear [ 3 ]. For example, while a scoping review might serve as the foundation for a full systematic review, it does not aim to evaluate the quality of the evidence like systematic reviews do [ 8 ]. Moreover, scoping review is also referred to as a “pilot study” [ 12 ], that can be used as a “trial run” of the entire systematic map; it helps to mold the intended approach for the review and inform the protocol development.

Rapid and scoping meta-reviews were also referred as types of scoping reviews. A “rapid review” is a particular kind of scoping review, which aims to provide an answer to a particular query and can shorten the process compared to a full systematic review [ 3 ]. The “scoping meta-review” (SMR) is a scoping evaluation of systematic reviews that offers researchers a flexible framework for field mapping and a way to condense pertinent research activities and findings, similar to a scoping review [ 13 ].

Almost all of the scoping studies identified in the corpus, draw from previews scoping review frameworks, such as the one proposed by [ 14 , 15 ] and the authors’ manual provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute [ 11 , 16 , 17 , 18 ].

3.1.2 Defining mapping review

A mapping review, also referred to as a “systematic map”, is “a high-level review with a broad research question” [ 3 ](p.133). The mapping review includes a thorough, systematic search of a wide field. It identifies the body of literature that is currently available on a subject and points out any gaps in the evidence. The mapping review can be conclusive in describing the available evidence and identifying gaps, whereas the scoping review is exploratory in nature [ 3 ].

The term “mapping” is used to describe the process of synthesizing and representing the literature numerically and thematically in tables, figures, or graphical representations, which can be thought of as the review output. Mapping enables researchers to pinpoint potential areas for further study as well as gaps in the literature [ 19 ].

Systematic mapping uses the same strict procedures as systematic reviews do. However, systematic mapping can be used to address open or closed-framed questions on broad or specific topics, because it is not constrained by the requirement to include fully specified and defined key elements [ 12 ]. Systematic mapping is especially useful for broad, multifaceted questions about an interesting topic that might not be appropriate for systematic review because they involve a variety of interventions, populations, or outcomes, or because they draw on evidence that is not just from primary research [ 12 ].

3.2 Process of conducting mapping and scoping reviews

As noted in the previous sections, mapping reviews and scoping reviews both aim to provide a broad overview of the literature, but the former focuses on the scope of the literature while the latter focuses on the nature and extent of available evidence on a specific research question or topic. In understanding the process for conducting mapping and scoping reviews, we adopted the eight steps proposed by Xiao and Watson [ 4 ] that are common for all types of reviews: (1) Formulate the problem; (2) Establishing and validating the review procedure; (3) Searching the literature; (4) Screening for inclusion; (5) Evaluating quality; (6) Extracting data; (7) Analyzing and synthesizing data; (8) Reporting the findings. The steps are explained in detail below and describe the methodology for both scoping and mapping reviews, distinguishing their differences where applicable. A summary of the review types along with their characteristics and steps as identified from the literature are presented in Table 2 .

3.2.1 Step 1 formulate the problem

The first step for undertaking a mapping or a scoping review is to formulate the problem by setting the research question that should be investigated, taking into account the topic’s scope [ 12 ]. It is important to clearly state the review objectives and specific review questions for the scoping review. The objectives should indicate what the scoping review is trying to achieve [ 10 , 20 ].

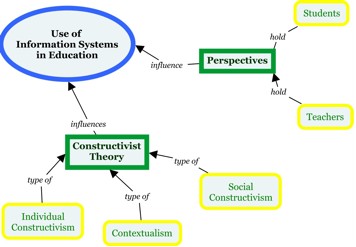

In mapping reviews, it can be helpful to create a conceptual framework or model (visual or textual) to describe what will be explored by the map when determining the mapping review’s scope. It should also be determined whether the topic’s scope is broad, specific, or likely to be supported by a substantial body of evidence [ 12 ].

3.2.1.1 Defining the research question(s)

Prior to beginning their search and paper selection process, the authors should typically define their research question(s) [ 3 ]. There are specific formats that are recommended for structuring the research question(s), as well as the exclusion and inclusion criteria of mapping and scoping reviews [ 21 ] (see Table 3 ).

PCC (Population, Concept, and Context) and PICO format (Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome) are often used in scoping and mapping reviews. It is recommended that research questions for scoping reviews follow the PCC format and include all of its components [ 17 , 18 , 21 ]. Information about the participants (e.g. age), the principal idea or “concept,” and the setting of the review, should all be included in the research question. The context should be made explicit and may take into account geographical or locational considerations, cultural considerations, and particular racial or gender-based concerns [ 10 ].

Researchers use the PCC format in order to determine the eligibility of their research questions, as well as to define their inclusion criteria (e.g [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]). Most scoping reviews have a single main question, but some of them are better served by one or more sub-questions that focus on specific PCC characteristics [ 8 , 18 ].

3.2.2 Step 2. Establishing and validating the review procedure

A protocol is crucial for scoping and mapping reviews because it pre-defines the scoping review’s goals and procedures [ 11 , 17 , 18 , 20 ], it clearly states all methodological decisions since the very beginning [ 2 ], and it also specifies the strategy to be used at each stage of the review process [ 12 ]. Similar to all systematic reviews, scoping reviews start with the creation of an a-priori protocol that includes inclusion and exclusion criteria that are directly related to the review’s objectives and questions [ 7 , 11 , 17 , 18 , 20 ]. In order to decrease study duplication and improve data reporting transparency, the use of formalized, registered protocols is suggested [ 18 , 19 ]. The international prospective register of systematic reviews, known as PROSPERO, states that scoping reviews (and literature reviews) are currently ineligible for registration in the database. While this could change in the future, scoping reviews can currently be registered with the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/ ) or Figshare ( https://figshare.com/ ), and their protocols can be published in select publications, including the JBI Evidence Synthesis [ 18 ].

Scoping and mapping reviews should require at least two reviewers in order to minimize reporting bias, as well as to ensure consistency and clarity [ 3 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. The reviewers should include a plan for the results presentation during the protocol development, such as a draft chart or table that could be improved at the end when the reviewers become more familiar with the information they have included in the review [ 17 , 18 ].

3.2.3 Step 3. Searching the literature