146+ Informative Speech Examples, Samples, Outlines, and Topics: Get Inspired

May 2, 2024

May 2, 2024 | Blog

Have you ever wondered what makes a speech truly informative and engaging? In exploring informative speech examples, we’ll dissect the elements that make a speech impactful and provide insights on crafting your compelling narrative. Whether you’re gearing up for a class presentation or simply curious about effective communication, we’ve got you covered.

What exactly is an informative speech, you ask? Well, think of it as a chance to share knowledge with your audience, like being a friendly guide on a journey of information. Unlike persuasive speeches aiming to sway opinions, informative speeches focus on presenting facts, ideas, or explanations.

So, let’s delve into this world of words, where you’ll discover the nuances of different speech types, from brief and concept speeches to autobiographical gems.

Ready to dive in? Let’s roll!

Table of Contents

What Are Informative Speeches

Imagine you’re sharing cool facts with your friends. That’s an informative speech! It’s a type of speech where you deliver fascinating details to your audience.

But wait, isn’t that the same as an explanatory speech? Not quite!

While an explanatory speech clarifies, an informative one educates. So, think of yourself as a friendly guide, not a textbook.

Your mission? Present relevant information, explain concepts, and make sure your audience leaves enlightened. No convincing is informative and needed; just sharing knowledge like a pro!

Ready to inform? Let’s roll!

Effective Informative Speaking Vs. Persuasive Speaking

Let’s talk about the difference between effective informativeand persuasive speaking. Imagine you’re presenting a persuasive speech – you’re on a mission to convince your audience to see things your way. It’s like being a smooth talker, aiming to sway opinions.

Conversely, informative peaking is like a friendly guide, sharing facts without pushing a particular viewpoint. So, how do you think you could spot the variance?

In persuasive speeches, your closing statement is like the grand finale, the big persuasion moment. In informative speeches, it’s more about leaving your audience with a clear understanding.

Remember, it’s not about convincing; it’s about enlightening. So, when choosing a topic, ask yourself, “Am I trying to persuade or inform?” That’s the key to crafting a speech that hits the right notes for your audience.

How do you write a good informative speech?

Let’s dive into the art of crafting a stellar informative speech. Have you ever wondered what makes public speaking a task and an opportunity to share knowledge? Here’s your guide:

- Start with a Clear Purpose: Ask yourself, “What’s my goal here? Am I educating, explaining, or demonstrating?” Knowing your purpose helps shape your entire speech.

- Know Your Audience: Who are you talking to? I think it’s important that you understand your audience’s knowledge level. Are they familiar with the topic, or is it new territory?

- Choose a Relevant Topic: Pick something your audience can connect with. Remember, it’s about them understanding, not you impressing.

- Research Like a Pro: Dive into your topic like a detective. Gather facts, examples, and anecdotes. The more well-researched your speech, the more credible you become.

- Craft a Clear Structure: Organize your speech logically. Start with an introduction, followed by main points, and end with a memorable conclusion. Think of it as a journey with a roadmap.

- Engage with Your Audience: Connect with nonverbal cues – eye contact and gestures. Imagine you’re having a conversation, not delivering a monologue.

- Keep It Simple: Explain complex concepts in simple terms. Avoid jargon that might confuse your audience.

- Be Passionate: Even if your topic seems dry, let your enthusiasm shine through. Your passion is contagious!

For students juggling academic responsibilities with speech preparation, platforms like MyAssignmentHelp.com can be a lifesaver. Whether you need assistance with “ write my paper ” services or expert guidance on your speech, they offer comprehensive support to help you excel.

How To Start An Informative Speech Examples

Have you ever wondered how to kick off an informative speech and grab your audience’s attention? Let’s break it down:

- Hook Your Audience: To start an informative speech, begin with a captivating fact, a relatable story, or a surprising statistic. Think of it as reeling in your audience, making them eager to hear more.

- Establish a Friendly Tone: In your introduction for an informative speech, set a welcoming atmosphere. Imagine you’re chatting with friends, creating a connection from the get-go.

- Declare Your Purpose: Could you explain why you’re there? Are you going to educate the audience on a fascinating topic or perhaps deliver an informative speech to clarify a concept?

- Please look over the Journey: Outline the main points you’ll cover. It’s like giving your audience a roadmap for the upcoming adventure. Could you let them know what to expect? Connect with nonverbal cues – eye contact and gestures

- Engage Your Audience: Interact with your audience members. Ask questions and share relatable experiences – make them part of the conversation. After all, an informative speech is a two-way street.

What does a good informative speech look like?

So, you’re curious about what a good informative speech looks like? Fantastic! Let’s paint a picture together:

- Clear Introduction: A great informative speech kicks off with a bang. Imagine it like a friendly invitation – you want your audience excited to join you on this learning journey. Ask a thought-provoking question or share an intriguing fact to grab their attention.

- Defined Purpose: Right out of the gate, your audience should know what type of speech they’re in for. Are you here to educate, explain, or show something cool? Make it crystal clear.

- Organized Structure: Picture your speech like a well-arranged book. Start with a captivating introduction, smoothly move through your main points, and wrap it up with a memorable conclusion. Think of it as a roadmap guiding your audience through the information.

- Engaging Content: Sprinkle your speech with relatable examples, anecdotes, or even a touch of humor. Keep your audience on their toes – you want them to remember your words.

- Visual Aids: If you’re explaining a process or showing statistics, use visuals. A picture is worth a thousand words.

- Connect with Your Audience: It’s about delivering information and connecting. Imagine you’re having a friendly chat, not delivering a lecture. Engage with your audience through eye contact and a conversational tone.

- Avoid Overloading with Information: While you want to be informative, avoid overwhelming your audience with a data dump. Pick the juiciest, most relevant information to keep them interested.

- Memorable Conclusion: Wrap things up with a bow. Summing up your main points and leaving your audience with a clear understanding. It’s like leaving a lasting impression after a great conversation.

What are examples of informative writing?

The following is an informative speaking excerpt on smoking:

It is general knowledge that smoking is bad for your health. Yet, the number of smokers globally increases each year. In 2018, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 1.1 billion people in the world use tobacco. That number might rise to 1.6 billion by 2025.

Tobacco kills, which smokers ignore until they get cancer or another terminal disease. It results in 6 million deaths per year. That means that there is one tobacco-related death every six seconds.

That said, a lack of information about the effects of smoking is a significant contributor to this pandemic. A survey conducted in China revealed that only 38% of tobacco smokers knew the habit could lead to heart disease, and only as few as 27% were aware smoking could cause a stroke.

Ignorance is no defense. So, today, I will present the adverse effects of tobacco and back them up with facts and real-world statistics.

The following is another informative speaking excerpt on global warming:

A global warming search on Google brings back 65 million results pages. The subject has drawn a lot of attention due to adverse climate change . In a speech presented at the UN Summit in 2019, Barrack Obama said that we must solve climate change swiftly and boldly or risk leaving future generations to an irreversible catastrophe.

A YouTube Influencer, Prince EA, addressed this issue by saying that our descendants will know it as the Amazon Desert instead of the Amazon Rainforest if we are not careful. Imagining the Amazon as a dessert should give you chills, and it seems so farfetched, but it could be a reality if global warming is not addressed.

But what exactly is global warming? What causes it? And what can we do to stop it? In this short but informative speech, I will answer these questions effectively.

Examples of Informative Speeches in Literature or Popular Culture:

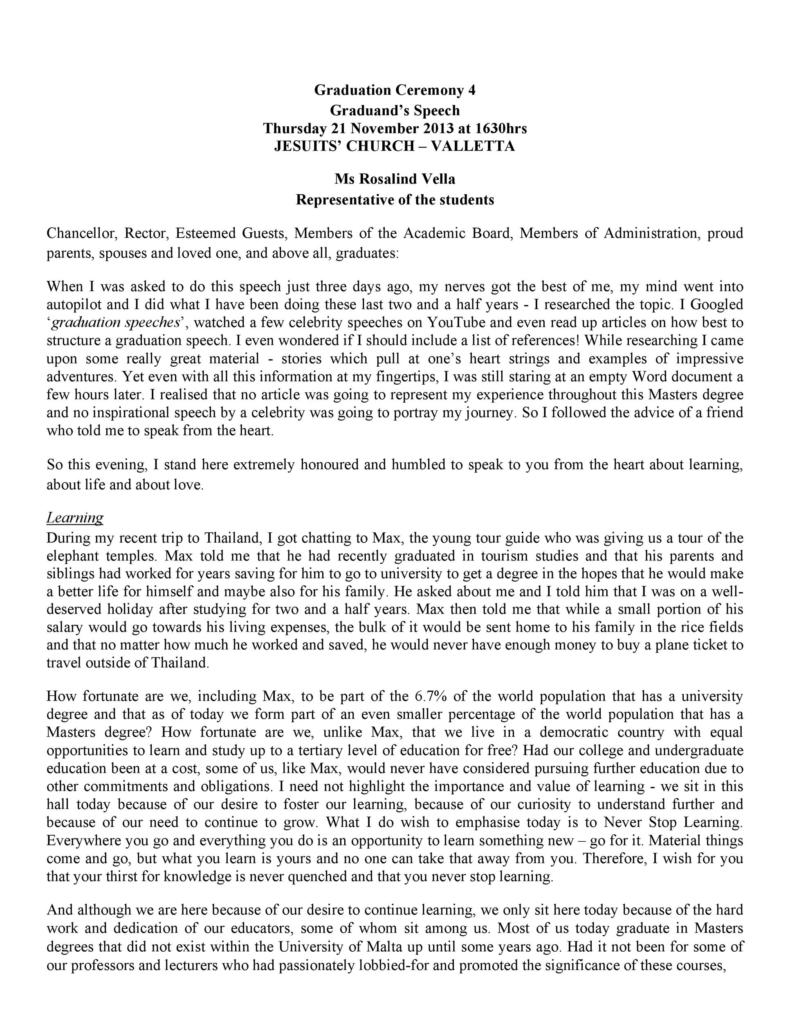

Excerpt from Marie Curie’s speech on the discovery of radium:

I could tell you many things about radium and radioactivity, and it would take a long time. But as we can not do that, I shall only give you a short account of my early work about radium. Radium is no longer a baby; it is more than twenty years old, but the discovery conditions were somewhat peculiar, so remembering and explaining them is always of interest. We must go back to the year 1897. Professor Curie and I worked then in the School of Physics and Chemistry laboratory, where Professor Curie held his lectures. I was engaged in some work on uranium rays which had been discovered two years before by Professor Becquerel.***I spent some time studying the way of making good measurements of the uranium rays, and then I wanted to know if there were other elements, giving out rays of the same kind. So I took up work about all known elements and their compounds and found that uranium compounds and all thorium compounds are active, but other elements were not found active, nor were their compounds. As for the uranium and thorium compounds, I found that they were active in proportion to their uranium or thorium content.

The impassioned political speech by President George W. Bush’s address to the nation as the US attacked Iraq begins as an informative speech:

At this hour, American and coalition forces are in the early stages of military operations to disarm Iraq, free its people, and defend the world from grave danger.

On my orders, coalition forces began striking selected targets of military importance to undermine Saddam Hussein’s ability to wage war. These are the opening stages of a broad and concerted campaign.

More than 35 countries are giving crucial support, from using naval and air bases to help with intelligence and logistics to deploying combat units. Every nation in this coalition has chosen to bear the duty and share the honor of serving in our common defense.

Informative Speech Examples

- Example Of A Speech

- Example Of A Written Speech

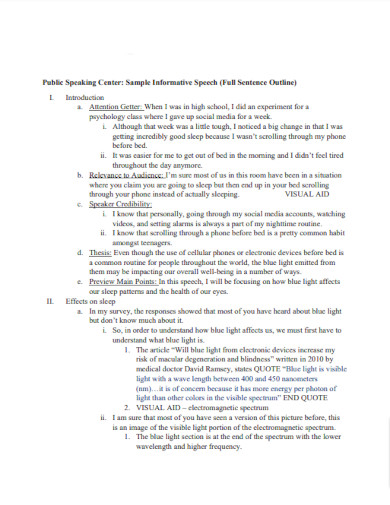

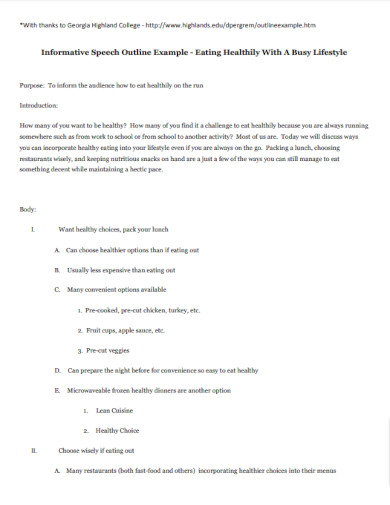

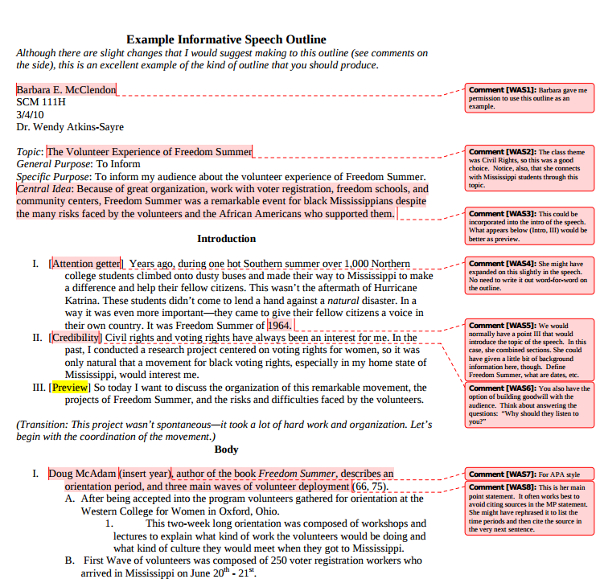

- Example Of An Outline For An Informative Speech

- Example Of Informative Outline – The Importance of Regular Physical Exercise

- Example Of Informative Presentation on The Fascinating World of Honeybees

- Example Of Informative Speech Introduction

- Example Of Informative Speech Outline

- Example Of Informative Speech Topics

- Example Of Introduction In Informative Speech

- Example Of Short Speech

- Example Of Speech Format

- Example Of Thesis Statement For Informative Speech

- Example Outline For Informative Speech

- Example Speeches For Students

- Example Topic Of Informative Speech

- Examples For Informative Speech

- Examples Of A How To Speech

- Examples Of A Informative Speech

- Examples Of An Informative Speech

- Examples Of An Informative Speech Outline

- Examples Of Informative Presentations

- Examples Of Informative Speech Outlines

- Examples Of Informative Speech Thesis Statements

- Examples Of Introduction Speeches

- Examples Of Introductory Speeches

- Examples Of Preview Statements

- Examples Of Speech Outlines

- Examples Of Speeches

- Examples Speech Writing

- Explanatory Speech Examples on the Power of Sleep

- Expository Speech Example

- An Example Of An Informative Speech

- Brief Speech Example

- Concept Speech Examples

- Description Speech Example

- Example For A Speech

- Example For Informative Speech

- Example In Speech

- Expository/Informative Speech Examples

- Inform Speech Examples

- Informal Speech Examples

- Informative Example

- Informative Presentation Examples

- Informative Presentation Outline Example

- Informative Speaking Examples

- Informative Speech Conclusion Example

- Informative Speech Examples About Life

- Informative Speech Examples For Students

- Informative Speech Intro Examples

- Informative Speech Introduction Example

- Informative Speech Introduction Examples

- Informative Speech Thesis Examples

- Informative Speech Thesis Statement Examples

- Informative Speech Topic Examples

- Informative Speech Topics Examples

- Informative Topic Examples

- Introduction In Speech Example

- Introduction Informative Speech Examples

- Introduction Speech Example

- Introduction Speech Examples For Students

- Introduction To Informative Speech Examples

- Outline Example For Informative Speech

- Outline Of Informative Speech Example

- Personal Speech Examples

- Preview Statement Examples

- Short Speech Examples

- Short Speech Examples For Students

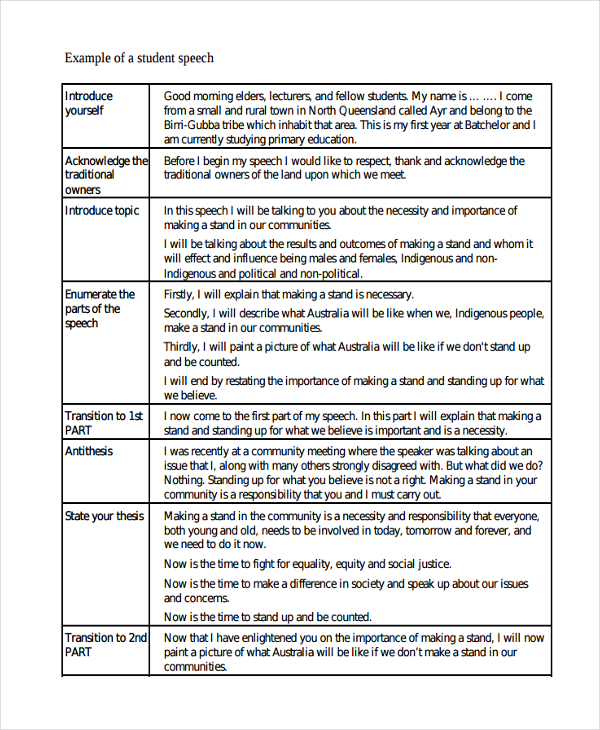

- Speech Examples For Students

- Speech Examples Informative

- Speech Informative Example

- Speech Introduction Examples

- Speech Of Explanation Examples

- Speech Script Example

- Speech Story Example

- Speech To Inform Examples

- Speech Writing Example

- Speech Writing Examples

- Thesis Examples For Informative Speech

- Thesis Examples For Speeches

- Thesis For Informative Speech Examples

- Written Speech Examples

- Informative Speech Worksheet Example

- Literature Informative Speech

- Short Informative Speech Examples

- Short Informative Speech on Smoking

- Literature Informative Speech Examples

- Informative Business Speech on New Product or Business Launch

- Business Informative Speech Examples

- Free Informative Speech

Informative Speech Samples

- Sample How To Speech

- Sample Informative Speech Outline

- Sample Of An Informative Speech

- Sample Of Informative Speech

- Sample Of Informative Speech Outline

- Sample Of Speech Introduction

- Sample Of Speech To Inform

- Sample Short Speech

- Sample Speech Outline Informative

- Sample Speech To Inform

- a sample of a speech

- best speech sample

- expository speech samples

- famous informative speeches

- great informative speeches

- intro of a speech sample

- personal experience speech samples

- short sample speech

- speech about informative

- speech samples for students

- Sample Informative Speech

- Student Informative Speech

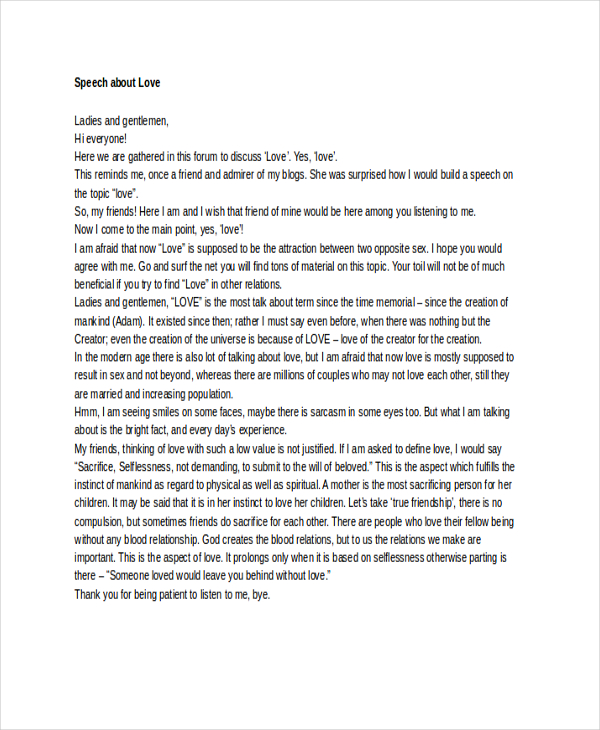

- Informative Speech about Love

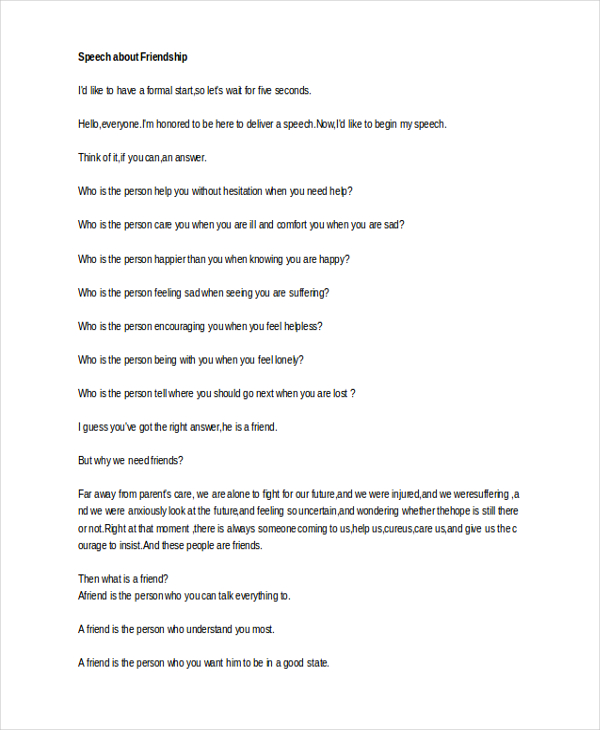

- Informative Speech about Friendship

- Example Informative Speech Outline

How To Write An Informative Speech Outline

- Start with a Clear Purpose: Before diving into the details, ask yourself, “What’s the goal here?” Is it to convince the audience of a particular viewpoint or inform them about a topic?

- Pick Your Main Points: Could you identify the key ideas you want to convey? Imagine telling a friend about your favorite movie – what would you highlight?

- Organize Your Thoughts: Arrange your main points logically. Think of it as creating a roadmap for your audience. You want them to follow along easily.

- Add Supporting Details: Each main point needs backup dancers! Sprinkle in facts, examples, or anecdotes. This isn’t a demonstrative speech , but adding a story here and there keeps it engaging.

- Create a Memorable Introduction: Your introduction is like the trailer for a movie. It should grab attention and hint at what’s coming. Consider posing a question or sharing a surprising fact.

- Conclude Strong: Summing up your main points and leave a lasting impression. A good conclusion for an informative speech should tell your audience, “Wow, I learned something valuable!”

- Practice Your Timing: A well-prepared speaker keeps an eye on the clock. Ensure your speech runs smoothly or cut smoothly, not run too long or cut too short.

- Be Open to Adjustments: Sometimes, the best ideas appear during practice. Be flexible and tweak your outline if needed. For tutoring, check out Spark on how to create an informative speech outline.

Informative Speech Outline Examples

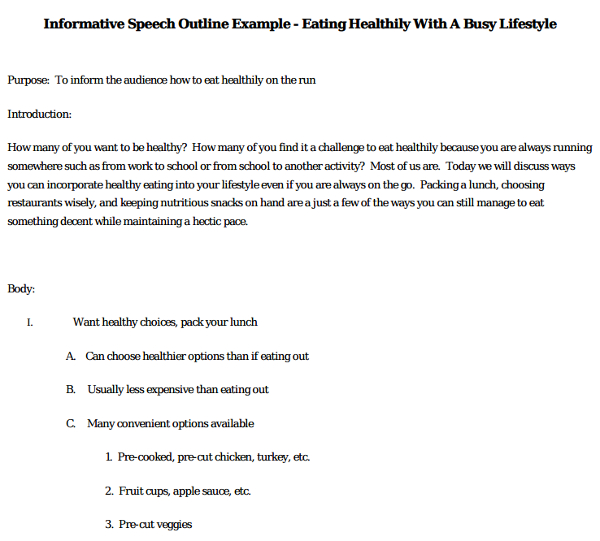

- Example Of An Informative Speech Outline

- Autobiographical Speech Outline

- Informative Outline Example

- Informative Outline Examples

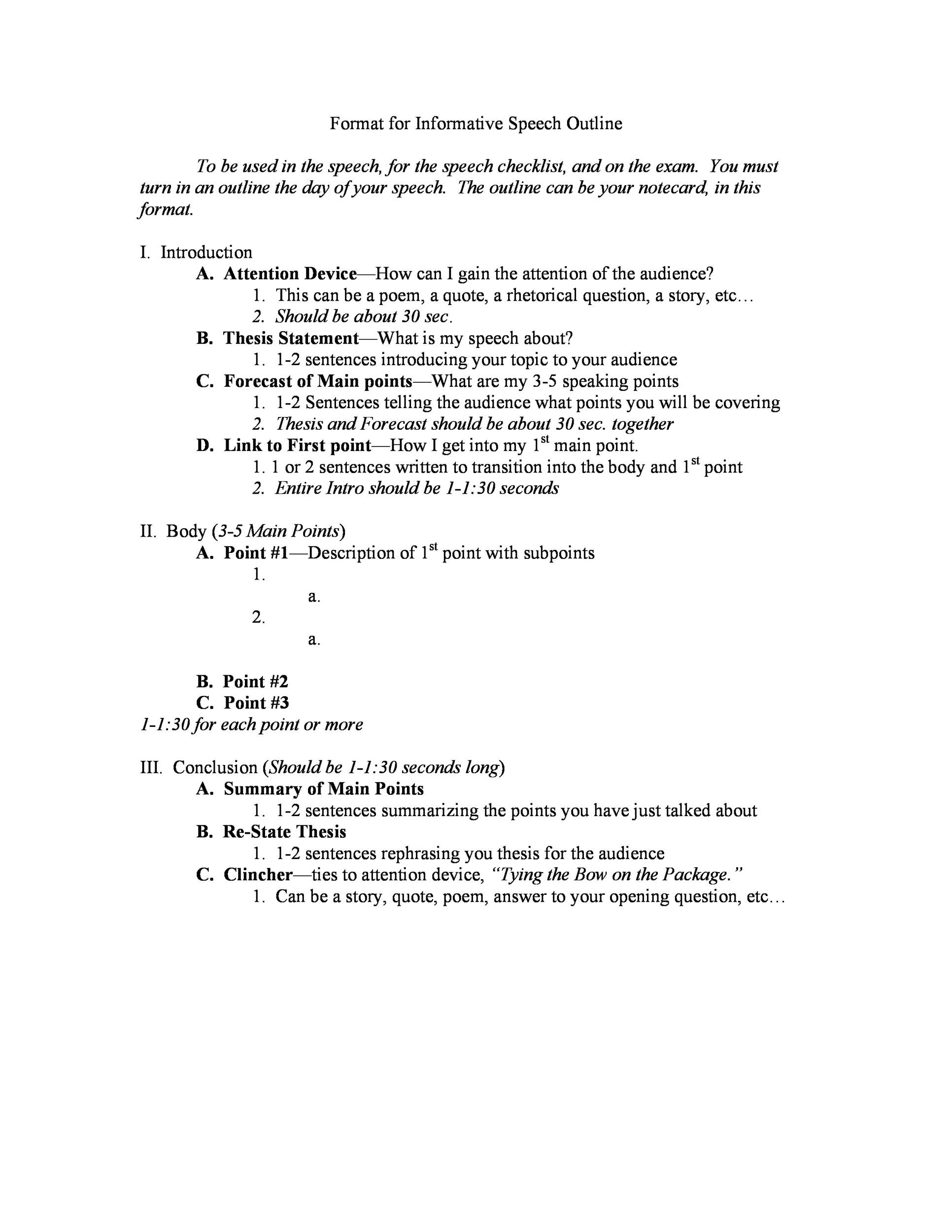

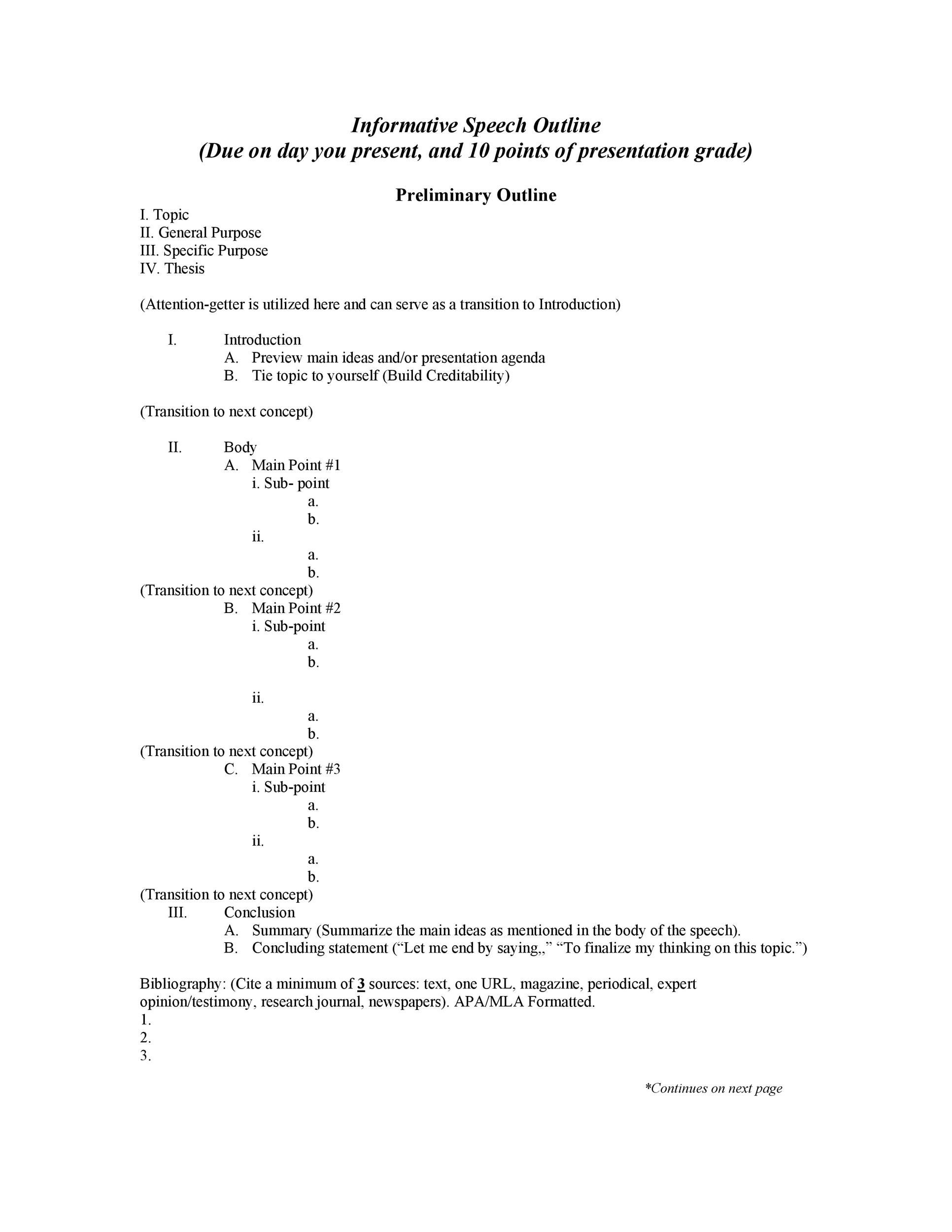

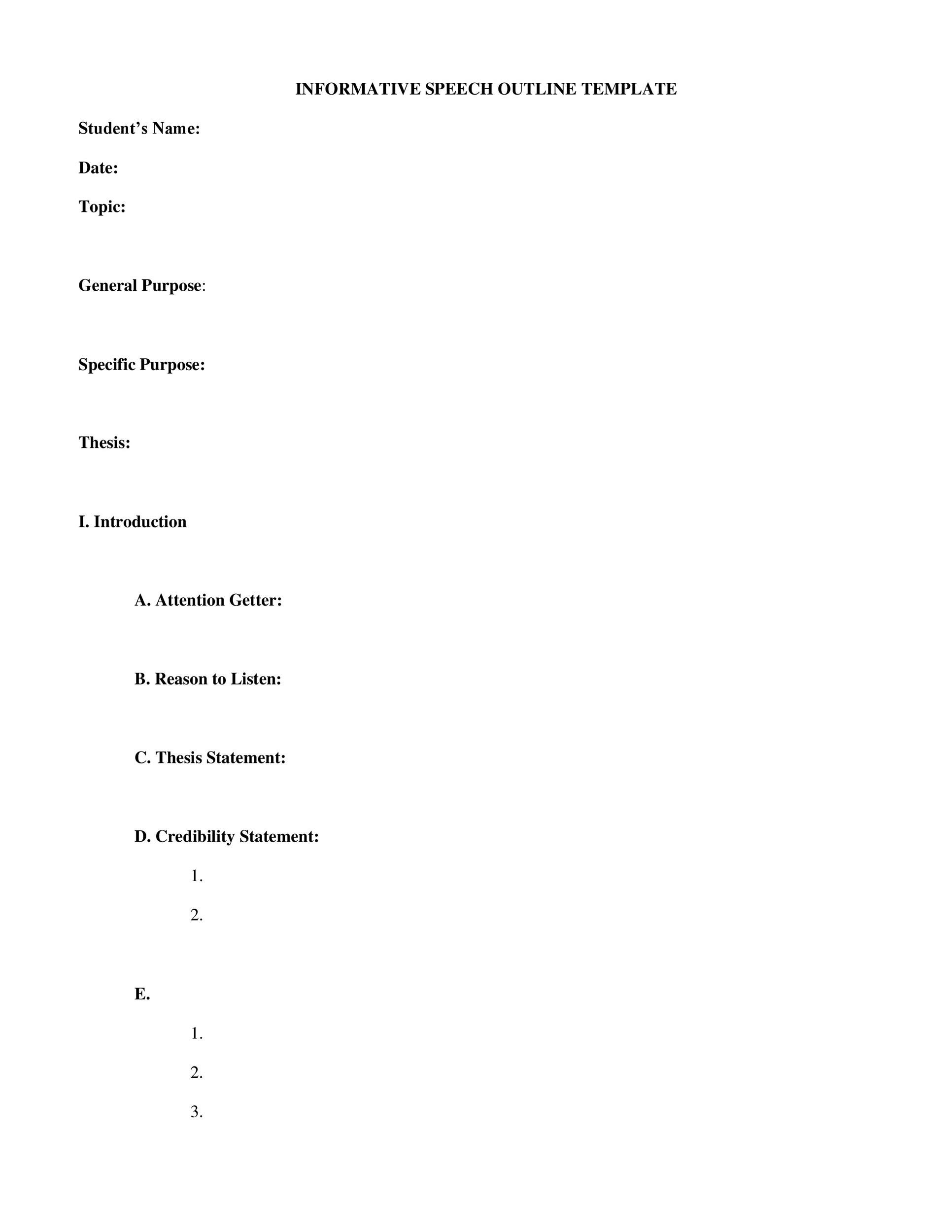

- Informative Speech Outline Format Example

- Informative Speech Outline Samples

- Informative Speech Outline Topics

- Informative Speech Template Outline

Informative Speech Format Examples

10+ informative speech examples & samples in pdf, alliteration examples in literature , informative speeches about concepts, informative speeches about objects, list of informative speech topics: ideas to spark your creativity, informative speeches topics for history and the humanities.

1. The Olympics in Ancient Greece

2. Explore the history of tattoos and body art

3. Economic divisions and the Vietnam War

4. Burial practices in ancient cultures and societies

5. How escaped enslaved people communicated along the Underground Railroad

6. Immigration history in America

7. Mahatma Gandhi and Indian apartheid

8. Innovations that came out of the great wars

9. The assassination of John F Kennedy

10. Sculpture in the Renaissance

11. The Salem Witch Trials

12. Colonization and its impact on the European powers in the Age of Exploration and beyond

13. The Gold Rush in California and its impact or significance

14. Fashion in Victorian Britain

15. Japanese Kamikaze fighters during World War II

16. The significance of the Stonewall Riots

17. The Spanish Flu

18. Rum running during Prohibition

19. Society and life in the Dark Ages

20. The mystery of Leonardo DaVinci’s Mona Lisa painting

Interesting Topic Ideas For English And Classic Literature

1. Depictions of classic literature in modern films

2. Depictions of the apocalypse in literature and fiction

3. Common themes in Victorian literature from the th century

4. How to beat writer’s block

5. Symbolism in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird

6. The history of spirits or the supernatural in classic literature

7. The concept of madness in William Shakespeare’s tragedies

8. War poetry from any period

9. How Shakespeare’s plays helped shape the modern language

10. Ernest Hemingway’s narrative on masculinity

11. How to define the canons of classic literature

12. Which books published today would be classic literature in the future?

13. Common themes in Gothic literature

14. Feminist theory and the works of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

15. The practice of banning books and literature from schools

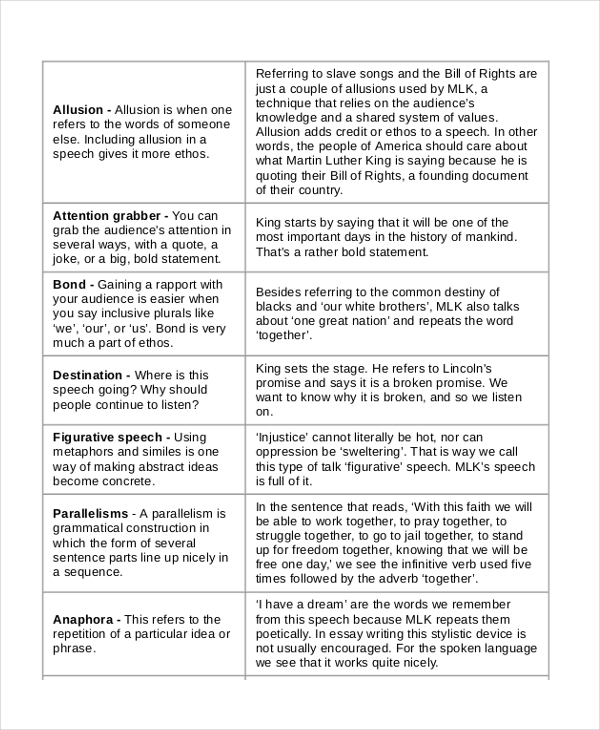

16. Rhetorical analysis of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech

17. Satire in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice

18. Human nature in Plato’s The Republic

19. The impact of modern technology on literature and publishing

20. Rationality in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies

Intriguing Topics About Current Affairs, Social Issues, And Human Rights

1. Current social movements such as Black Lives Matter or the Occupy Wall Street movement

2. The influence of cultural traditions on human rights in various countries

3. Benefits of social media for collective action in areas where human rights are being contested

4. Support and guidance for troubled children in the current foster care system

5. The prevalence of child abuse in modern society

6. The United Nations Human Rights Council and its purpose/function

7. Women’s rights/freedoms in third world countries

8. Human trafficking in first-world countries

9. Patterns in America’s fastest-growing cities

10. Generational divisions and tensions between Baby Boomers, Millennials, or Generation Z

11. The concept of universal human rights

12. What our society has learned from the COVID- pandemic

13. Uses of torture to extract information from high-level criminals or terrorists

14. The influence of Westernization on human rights in other countries

15. The role of the United Nations in the interest of global human rights

16. Racial prejudice in the workplace

17. Explore modern protest culture

18. Idolization of celebrities in modern society

19. “Viral” culture in today’s society

20. Social media influencers and Tik Tok stars and their celebrity status among Generation Z

Creative Ideas For Film, Music, And Popular Culture

1. Mythology in popular culture

2. Censorship issues in music

3. Superhero culture in society

4. Focus on a music subculture and how it has empowered that group of people

5. Modern horror films and “shock value”

6. The importance of teaching music in elementary and high schools

7. The impact of a historical musician or musical group and their impact on today’s music

8. How streaming services have changed the film/television or music industry

9. Domestic violence in the media

10. Disney princesses and their impact on young girls in society

11. The history of jazz music in New Orleans

12. Crime scene television – accuracies and inaccuracies

13. Which popular cultural artifacts will archaeologists study in the future to learn about our society?

14. The role of music in social movements

15. Originality in today’s music, movies, or television shows

16. Religious symbolism in Star Wars

17. The current status of the idea of the “Blockbuster” movie

18. Child stars and the problems they face as they age

19. Sexuality and messaging in film and television

20. The power of satire in comedy

What are some good topics for an informative speech?

Example Informative Speech Topics

Informational Topics For Speeches Informative Speech Ideas Informative Speech About A Person Informative Speech Essay Informative Speech Intro Informative Speech Introduction Informative Speech Meaning

Sample Informative Speech Topics

Topics To Do Informative Speeches On Things To Write An Informative Speech About What To Write An Informative Speech About What To Write An Informative Speech On

Get Help With Your Informative Speech Writing

Need help with your informative speech? Fret not! Essay Freelance Writers has your back. Our expert team excels in crafting top-notch speeches tailored just for you. How do I nail that conclusion for an informative speech? We’ve got the perfect formula. But hey, what exactly is an informative speech, you ask? It’s a dynamic way to inform the audience and share knowledge. Our skilled writers present information effectively and ensure your speech leaves a lasting impact. Whether you need to define informative speech elements or deliver a compelling information speech, our team guides you. So, why stress? Click that ORDER NOW button to make your informative speech shine!

What is an example of an informative speech?

An example of informative speaking could be a presentation on climate change, providing facts and data to educate the audience.

What are good informative speech topics?

Good informative speech topics include subjects like space exploration, sustainable living, or the history of ancient civilizations.

What is an example of an informative speech about objects?

An informative speech about objects could focus on the history and significance of a specific artifact, like the Rosetta Stone.

What is a good introduction for an informative speech?

A good introduction for an informative speech grabs attention, such as posing a thought-provoking question or sharing a relevant anecdote, setting the tone for the presentation.

With a passion for helping students navigate their educational journey, I strive to create informative and relatable blog content. Whether it’s tackling exam stress, offering career guidance, or sharing effective study techniques

People Also Read

- 78 Sports Informative Speech Topics To Wow Your Audience

- Master the Art of Writing an Informative Essay with These 10 Examples

- Top 293 Speech Topics for Students: Persuasive, Descriptive, Informative Speech Topics

Most Popular Articles

Racism thesis statement example, how to rephrase a thesis statement, capstone project topic suggestions, how to write an abortion essay, should students wear school uniforms essay, list causal essay topics write, respect essay, signal words, great synonyms, informative speech examples, essay writing guide, introduction paragraph for an essay, argumentative essay writing, essay outline templates, write an autobiographical essay, personal narrative essay ideas, descriptive essay writing, how to write a reflective-essay, how to write a lab report abstract, how to write a grant proposal, point of view in an essay, debate topics for youth at church, theatre research paper topics, privacy overview.

15 Informative Speech Examples to Inspire Your Next Talk

- The Speaker Lab

- May 13, 2024

Table of Contents

A good informative speech is one of the most effective tools in a speaker’s arsenal. But with so many potential topics out there, it can be tough to know where to start. That’s why we’ve compiled 15 informative speech examples to help you find your perfect subject. Whether you’re unearthing secrets from history for your listeners or delving into future technologies, informative speeches can prove to be the recipe for the perfect talk.

But crafting an effective informative speech is about more than just picking a topic. You have to research topics, put your thoughts in order, and speak up clearly and confidently. In this post, we’ll explore strategies for each step of the process, so you can create a speech that informs, engages, and makes a lasting impact on your listeners. Let’s get started.

15 Informative Speech Examples

If you’re looking for some inspiration for your next informative speech, look no further. Below are 15 examples of informative speech topics that are sure to engage and educate your audience.

- The history and evolution of social media platforms

- The benefits and drawbacks of renewable energy sources

- The impact of sleep deprivation on mental and physical health

- The role of emotional intelligence in personal and professional success

- The science behind climate change and its potential consequences

- The importance of financial literacy for young adults

- The influence of artificial intelligence on various industries

- The benefits of regular exercise and a balanced diet

- The history and cultural significance of a specific art form or genre

- The impact of technology on interpersonal communication

- The psychology behind procrastination and effective strategies to overcome it

- The role of diversity and inclusion in fostering innovation and creativity

- The importance of mental health awareness and resources for students

- The future of space exploration and its potential benefits for humanity

- The impact of globalization on local economies and cultures

These topics cover a wide range of subjects, from technology and science to psychology and culture. By choosing one of these informative speech examples, you’ll have plenty of material to work with to create an engaging and educational presentation.

Remember, the key to a successful informative speech is to choose a topic that you’re passionate about and that will resonate with your audience. Do your research, organize your thoughts, and practice your delivery to ensure that your message comes across loud and clear.

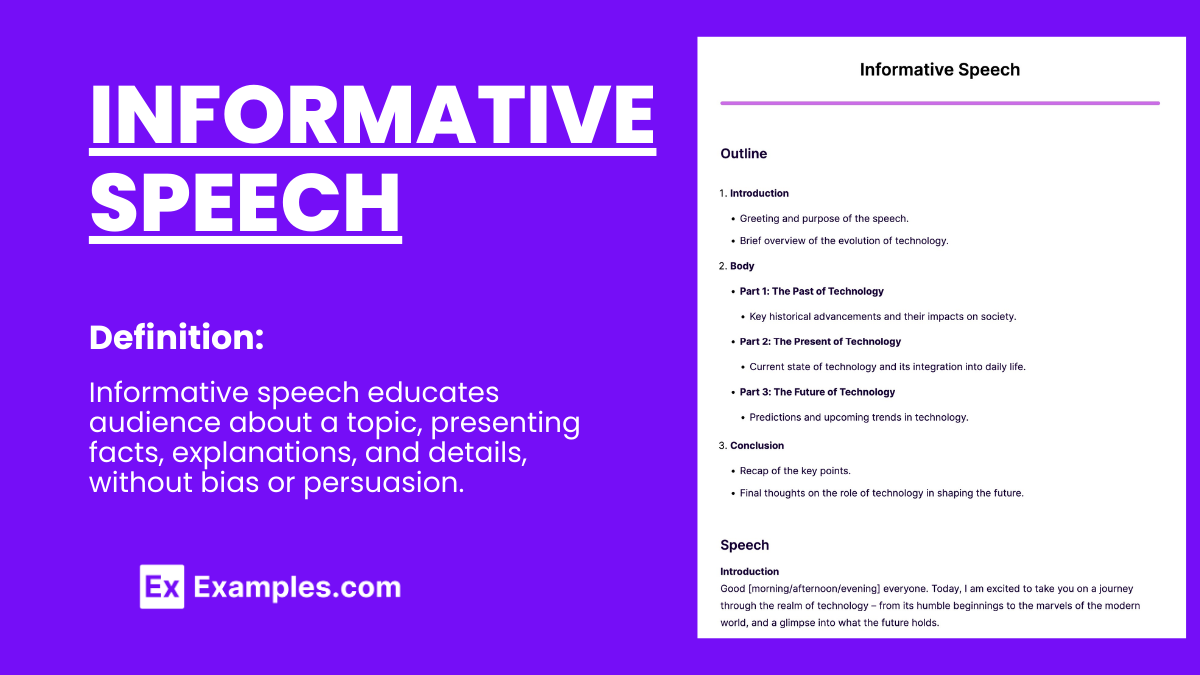

What Is an Informative Speech?

If you’ve ever been to a conference or seminar, chances are you’ve heard an informative speech. But what exactly is an informative speech? Simply put, it’s a type of speech designed to educate the audience on a particular topic. The goal is to provide interesting and useful information, ensuring the audience walks away with new knowledge or insights. Unlike persuasive speeches that aim to convince the audience of a viewpoint, informative speeches focus on explaining a subject clearly and objectively.

Types of Informative Speeches

Informative speeches come in various forms, each with its own purpose. The most common types are definition, explanation, description, and demonstration speeches. Depending on the objective, an informative speech can take on different structures and styles.

For example, a definition speech aims to explain a concept or term, while a demonstration speech shows the audience how to perform a task or process. An explanatory speech, on the other hand, provides a detailed account of a complex subject, breaking it down into digestible parts.

Purpose of Informative Speeches

At its core, the purpose of an informative speech is to share knowledge with the audience. These speeches are characterized by their fact-based, non-persuasive nature. The focus is on delivering information in an engaging and accessible way.

A well-crafted informative speech not only educates but also sparks curiosity and encourages further learning. By dedicating yourself to providing valuable information and appealing to your audience’s interests, you can succeed as an informative speaker.

Strategies for Selecting an Informative Speech Topic

Choosing the right topic is crucial for an effective informative speech. You want a subject that is not only interesting to you but also relevant and engaging for your audience. Consider their knowledge level, background, and expectations when selecting your topic.

One strategy is to focus on a subject you’re passionate about or have expertise in. This allows you to speak with authority and enthusiasm, making your speech more compelling. Another approach is to address current events or trending topics that are on people’s minds.

When brainstorming potential topics, consider your speech’s purpose and the type of informative speech you want to deliver. Is your goal to define a concept, explain a process, describe an event, or demonstrate a skill? Answering these questions will help guide your topic selection.

Find Out Exactly How Much You Could Make As a Paid Speaker

Use The Official Speaker Fee Calculator to tell you what you should charge for your first (or next) speaking gig — virtual or in-person!

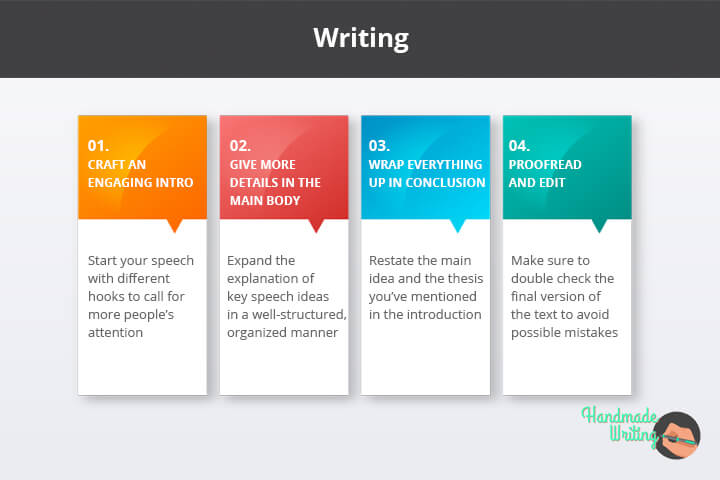

How to Write an Informative Speech

Now that you’ve selected your topic, it’s time to start writing your informative speech. The key to a successful speech is thorough preparation and a clear, organized structure. Let’s break down the steps involved in crafting an engaging and informative presentation.

Researching Your Topic

Before you start writing, it’s essential to conduct thorough research on your topic. Gather facts, statistics, examples, and other supporting information for your informative speech. These things will help you explain and clarify the subject matter to your audience.

As you research, use reliable sources such as academic journals, reputable websites, and expert opinions to ensure the accuracy and credibility of your information. Take notes and organize your findings in a way that makes sense for your speech’s structure.

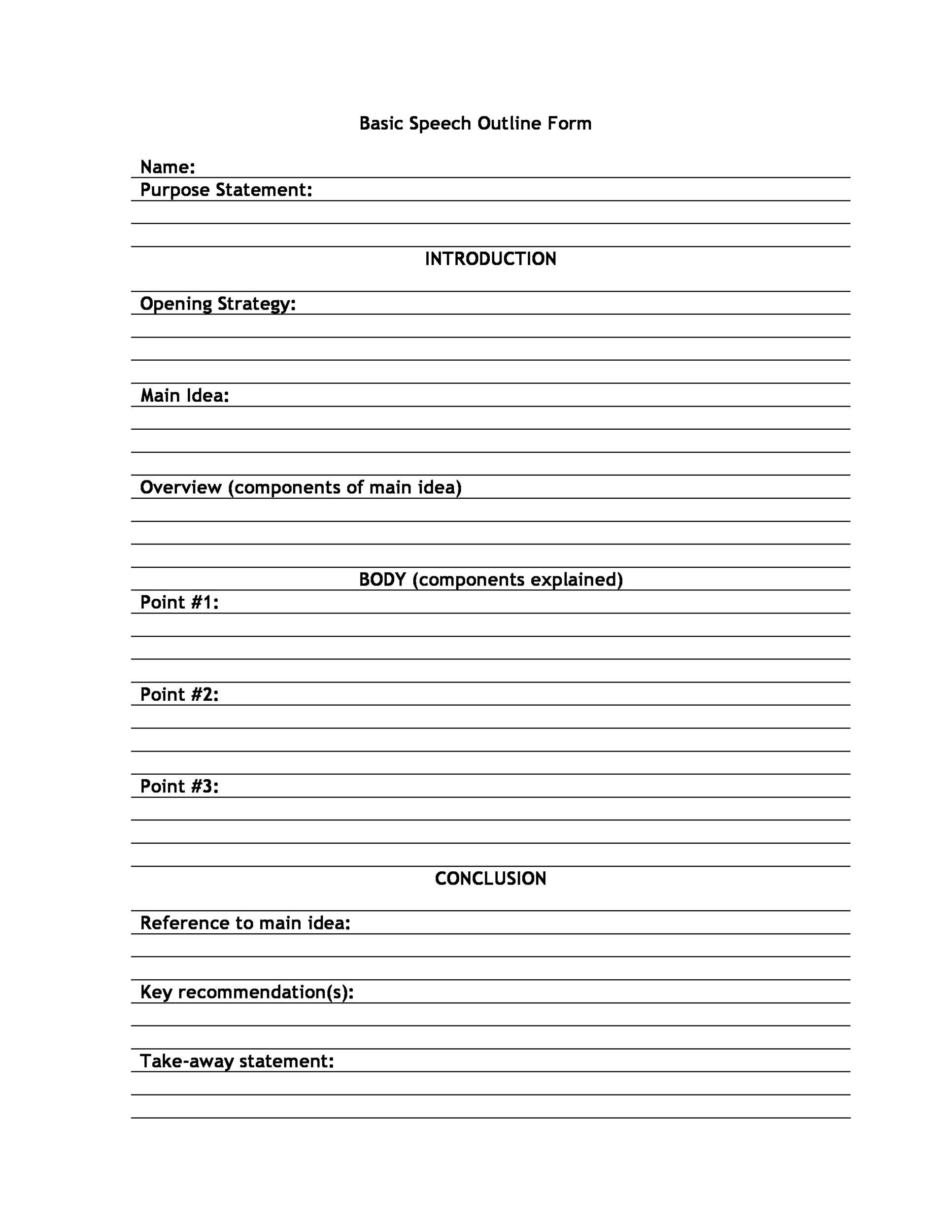

Structuring Your Speech

A typical informative speech structure includes three main parts, namely, an introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction should grab the audience’s attention, establish your credibility , and preview the main points you’ll cover.

The body of your speech is where you’ll present your main points and supporting evidence. Use clear transitions between each point to maintain a logical flow. The conclusion should summarize your key takeaways and leave a lasting impression on your audience.

Outlining Your Speech

Creating an outline is a crucial step in organizing your thoughts and ensuring a coherent flow of information. Start by listing your main points and then add subpoints and supporting details for each section.

A well-structured outline will serve as a roadmap for your speech, keeping you on track and helping you stay focused on your key messages. It also makes the writing process more efficient and less overwhelming.

Writing Your Draft

With your outline in hand, it’s time to start writing your draft. Focus on presenting information clearly and concisely, using simple language and avoiding jargon. Provide examples and analogies throughout your informative speech in order to illustrate complex ideas and make them more relatable to your audience.

As you write, keep your audience in mind and tailor your language and examples to their level of understanding. Use transitions to link your ideas and maintain a smooth flow throughout the speech.

Editing and Revising

Once you’ve completed your draft, take the time to edit and revise your speech. First, check for clarity, accuracy, and logical organization. Then, eliminate unnecessary details, repetition, and filler words.

Read your speech aloud to identify any awkward phrasing or unclear passages. Lastly, seek feedback from others and be open to making changes based on their suggestions. Remember, the goal is to create a polished and effective informative speech.

Delivering an Informative Speech

You’ve written a fantastic informative speech, but now comes the real challenge: delivering it effectively. The way you present your speech can make all the difference in engaging your audience and ensuring they retain the information you’re sharing.

Practicing Your Speech

Practice makes perfect, and this couldn’t be more true when it comes to public speaking . Rehearse your speech multiple times to build confidence and familiarity with the content. Practice in front of a mirror, family members, or friends to get comfortable with your delivery.

As you practice, focus on your pacing, intonation, and body language. Aim for a conversational tone and maintain eye contact with your audience. The more you practice, the more natural and engaging your delivery will become.

Using Visual Aids

Visual aids such as slides, charts, or props can enhance your informative speech by making complex information more accessible and engaging. When utilized in your informative speech, they can help illustrate key points, provide visual examples, and break up the monotony of a purely verbal presentation.

Of course, it’s important to ensure your visuals are clear, relevant, and easy to understand. Otherwise, they may end up obscuring your points instead of clarifying them. In light of this, avoid cluttering your slides with too much text or overwhelming your audience with too many visuals. Use them strategically to support your message, not distract from it.

Engaging Your Audience

Engaging your audience is crucial for a successful informative speech. Use rhetorical questions, anecdotes, or interactive elements to keep them involved and attentive. Encourage participation, if appropriate, and maintain a conversational tone to create a connection with your listeners.

Pay attention to your audience’s reactions and adapt your delivery accordingly. If you sense confusion or disinterest, try rephrasing your points or providing additional examples to clarify your message. Remember, your goal is to educate and inspire your audience, so keep them at the forefront of your mind throughout your speech.

Handling Nerves

It’s normal to feel nervous before and during a speech, but there are strategies to help you manage those nerves . Take deep breaths, visualize success, and focus on your message rather than your anxiety. Remember, your audience wants you to succeed, and a little nervousness can actually enhance your performance by showing enthusiasm and authenticity.

If you find yourself getting overwhelmed, take a moment to pause, collect your thoughts, and regain your composure. Smile, make eye contact, and remind yourself that you’ve prepared thoroughly and have valuable information to share.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

To deliver an effective informative speech, it’s important to be aware of common pitfalls and mistakes. One of the biggest errors is overloading your audience with too much information. Remember, less is often more when it comes to public speaking.

Another mistake is failing to organize your content logically or using complex jargon without explanation. Make sure your speech has a clear structure and that you’re explaining any technical terms or concepts in a way that your audience can understand.

Finally, don’t neglect the importance of practice and preparation. Winging it or relying too heavily on notes can lead to a disjointed and unengaging speech. Take the time to rehearse, refine your delivery, and internalize your key points.

By avoiding these common mistakes and focusing on the strategies we’ve discussed, you’ll be well on your way to delivering an informative speech that educates, engages, and inspires your audience.

Tips for Delivering a Compelling Informative Speech

Once you’ve chosen your topic and done your research, it’s time to focus on delivering a compelling speech. Here are a few tips to keep in mind:

- Start with a strong attention-grabbing opening that draws your audience in and sets the tone for your speech.

- Use clear, concise language and avoid jargon or technical terms that your audience may not understand.

- Incorporate storytelling, examples, and anecdotes to make your points more relatable and memorable.

- Use visual aids , such as slides or props, to enhance your message and keep your audience engaged.

- Practice your delivery and timing to ensure that you stay within your allotted time and maintain a natural, conversational tone.

By following these tips and choosing a topic that you’re passionate about, you’ll be well on your way to delivering an informative speech that educates and inspires your audience.

Get The #1 Marketing Tool To Book More Paid Speaking Gigs

This FREE tool helped one speaker book $36,000+ in speaking gigs before he had a website! Learn how you can use this tool to Get Booked & Paid to Speak™ on a consistent basis.

20 Bonus Topics for Informative Speeches

In case the informative speech examples above didn’t pique your interest, we have several more for you to consider. Ranging from topics like science and technology to history and education, these 20 topics are perfect for your next presentation.

- The history and development of virtual reality technology

- The benefits and challenges of remote work

- The science behind the formation of hurricanes and tornadoes

- The impact of social media on political campaigns and elections

- The importance of sustainable fashion and its environmental benefits

- The role of emotional support animals in mental health treatment

- The history and cultural significance of a specific cuisine or dish

- The impact of plastic pollution on marine ecosystems

- The benefits and risks of gene editing technology

- The psychology behind conspiracy theories and their spread online

- The importance of digital privacy and data security in the modern age

- The role of music therapy in healthcare and wellness

- The impact of deforestation on biodiversity and climate change

- The history and evolution of a specific sport or athletic event

- The benefits and challenges of alternative education models

- The science behind the human immune system and how vaccines work

- The impact of mass incarceration on communities and families

- The role of storytelling in preserving cultural heritage and traditions

- The importance of financial planning for retirement and old age

- The impact of urban agriculture on food security and community development

Choosing a Topic That Resonates With Your Audience

When selecting a topic for your informative speech, it’s important to consider your audience and what will resonate with them. Think about their interests, backgrounds, and knowledge levels, and choose a topic that will be both informative and engaging.

For example, if you’re speaking to a group of high school students, you may want to choose a topic that relates to their experiences or concerns, such as the impact of social media on mental health or the importance of financial literacy for young adults. If you’re speaking to a group of business professionals, you may want to focus on topics related to industry trends, leadership strategies, or emerging technologies.

By choosing a topic that resonates with your audience, you’ll be more likely to capture their attention and keep them engaged throughout your speech. And remember, even if you’re not an expert on the topic, you can still deliver an informative and engaging speech by doing your research and presenting the information in a clear and accessible way.

FAQs on Informative Speech Examples

What is an example of informative speech.

An example includes breaking down the impacts of climate change, detailing causes, effects, and potential solutions.

What are the 3 types of informative speeches?

The three main types are explanatory (breaks down complex topics), descriptive (paints a picture with words), and demonstrative (shows how to do something).

What are the 5 useful topics of an informative speech?

Top picks include technology advances, mental health awareness, environmental conservation efforts, cultural diversity appreciation, and breakthroughs in medical research.

What is an effective informative speech?

An effective one delivers clear info on a specific topic that educates listeners without overwhelming them. It’s well-researched and engaging.

Informative speech examples are everywhere, if you know where to look. From TED Talks to classroom lectures, there’s no shortage of inspiration for your next presentation. All you have to do is find a topic that lights your fire while engaging your audience.

Remember, a great informative speech is all about clarity, organization, and engagement. By following the tips and examples we’ve covered, you’ll be well on your way to delivering an informative speech that educates, enlightens, and leaves a lasting impression. So go ahead, pick your topic, and start crafting your own informative speech today!

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024

Explore Related Resources

Learn How You Could Get Your First (Or Next) Paid Speaking Gig In 90 Days or Less

We receive thousands of applications every day, but we only work with the top 5% of speakers .

Book a call with our team to get started — you’ll learn why the vast majority of our students get a paid speaking gig within 90 days of finishing our program .

If you’re ready to control your schedule, grow your income, and make an impact in the world – it’s time to take the first step. Book a FREE consulting call and let’s get you Booked and Paid to Speak ® .

About The Speaker Lab

We teach speakers how to consistently get booked and paid to speak. Since 2015, we’ve helped thousands of speakers find clarity, confidence, and a clear path to make an impact.

Get Started

Let's connect.

Copyright ©2023 The Speaker Lab. All rights reserved.

Informative Speeches — Types, Topics, and Examples

What is an informative speech.

An informative speech uses descriptions, demonstrations, and strong detail to explain a person, place, or subject. An informative speech makes a complex topic easier to understand and focuses on delivering information, rather than providing a persuasive argument.

Types of informative speeches

The most common types of informative speeches are definition, explanation, description, and demonstration.

A definition speech explains a concept, theory, or philosophy about which the audience knows little. The purpose of the speech is to inform the audience so they understand the main aspects of the subject matter.

An explanatory speech presents information on the state of a given topic. The purpose is to provide a specific viewpoint on the chosen subject. Speakers typically incorporate a visual of data and/or statistics.

The speaker of a descriptive speech provides audiences with a detailed and vivid description of an activity, person, place, or object using elaborate imagery to make the subject matter memorable.

A demonstrative speech explains how to perform a particular task or carry out a process. These speeches often demonstrate the following:

How to do something

How to make something

How to fix something

How something works

How to write an informative speech

Regardless of the type, every informative speech should include an introduction, a hook, background information, a thesis, the main points, and a conclusion.

Introduction

An attention grabber or hook draws in the audience and sets the tone for the speech. The technique the speaker uses should reflect the subject matter in some way (i.e., if the topic is serious in nature, do not open with a joke). Therefore, when choosing an attention grabber, consider the following:

What’s the topic of the speech?

What’s the occasion?

Who’s the audience?

What’s the purpose of the speech?

Common Attention Grabbers (Hooks)

Ask a question that allows the audience to respond in a non-verbal way (e.g., a poll question where they can simply raise their hands) or ask a rhetorical question that makes the audience think of the topic in a certain way yet requires no response.

Incorporate a well-known quote that introduces the topic. Using the words of a celebrated individual gives credibility and authority to the information in the speech.

Offer a startling statement or information about the topic, which is typically done using data or statistics. The statement should surprise the audience in some way.

Provide a brief anecdote that relates to the topic in some way.

Present a “what if” scenario that connects to the subject matter of the speech.

Identify the importance of the speech’s topic.

Starting a speech with a humorous statement often makes the audience more comfortable with the speaker.

Include any background information pertinent to the topic that the audience needs to know to understand the speech in its entirety.

The thesis statement shares the central purpose of the speech.

Demonstrate

Preview the main ideas that will help accomplish the central purpose. Typically, informational speeches will have an average of three main ideas.

Body paragraphs

Apply the following to each main idea (body) :

Identify the main idea ( NOTE: The main points of a demonstration speech would be the individual steps.)

Provide evidence to support the main idea

Explain how the evidence supports the main idea/central purpose

Transition to the next main idea

Review or restate the thesis and the main points presented throughout the speech.

Much like the attention grabber, the closing statement should interest the audience. Some of the more common techniques include a challenge, a rhetorical question, or restating relevant information:

Provide the audience with a challenge or call to action to apply the presented information to real life.

Detail the benefit of the information.

Close with an anecdote or brief story that illustrates the main points.

Leave the audience with a rhetorical question to ponder after the speech has concluded.

Detail the relevance of the presented information.

Before speech writing, brainstorm a list of informative speech topic ideas. The right topic depends on the type of speech, but good topics can range from video games to disabilities and electric cars to healthcare and mental health.

Informative speech topics

Some common informative essay topics for each type of informational speech include the following:

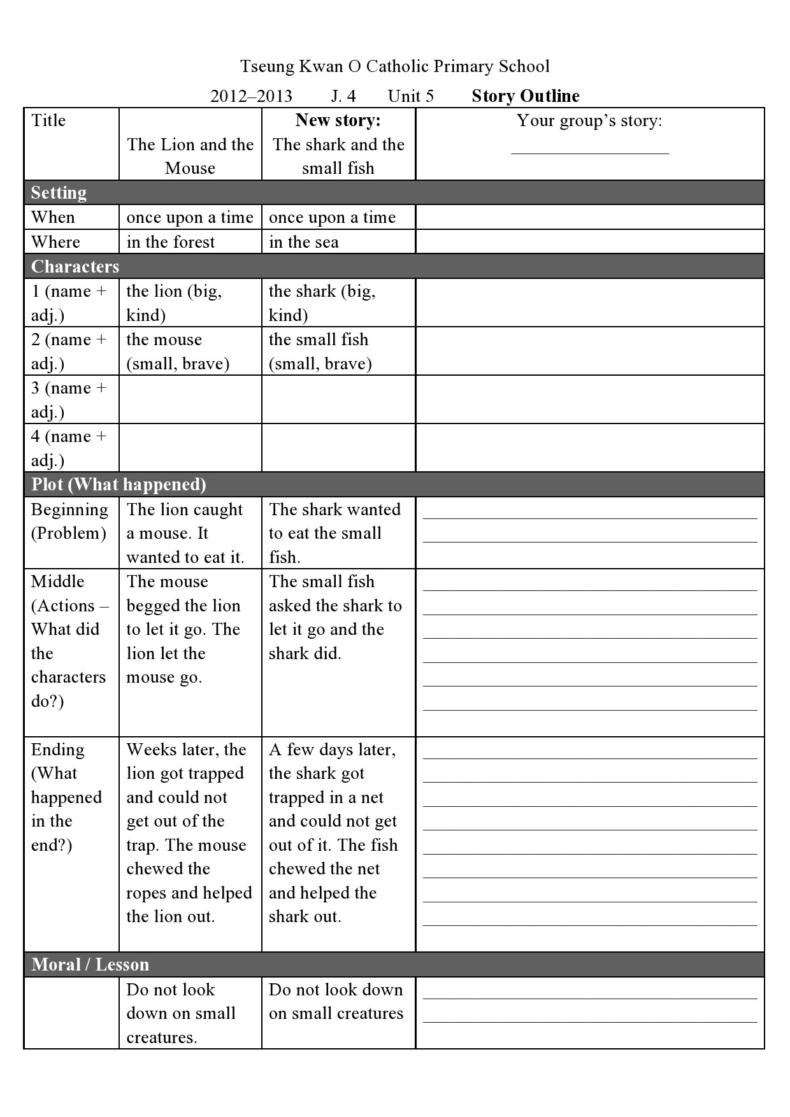

| What is the electoral college? | Holidays in different cultures/different countries | Best concert | Bake a cake |

| What is a natural disaster? | Cybersecurity concerns | Childhood experience | Build a model (airplane, car, etc.) |

| What is the “glass ceiling?” | Effect of the arts | Day to remember | Build a website |

| What is globalization? | How the stock market works | Dream job | Apply for a credit card |

| What is happiness? | Impact of global warming/climate change | Embarrassing moment | Change a tire |

| What is humor? | Important lessons from sports | Favorite place | Learn an instrument |

| What is imagination? | Influence of social media and cyberbullying | First day of school | Play a sport |

| What is love? | Social networks/media and self-image | Future plans | Register to vote |

| What is philosophy? | Evolution of artificial intelligence | Happiest memory | Train a pet |

| What was the Great Depression? | Impact of fast food on obesity | Perfect vacation | Write a resume |

Informative speech examples

The following list identifies famous informational speeches:

“Duties of American Citizenship” by Theodore Roosevelt

“Duty, Honor, Country” by General Douglas MacArthur

“Strength and Dignity” by Theodore Roosevelt

Explanation

“Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” by Patrick Henry

“The Decision to Go to the Moon” by John F. Kennedy

“We Shall Fight on the Beaches” by Winston Churchill

Description

“I Have a Dream” by Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Pearl Harbor Address” by Franklin Delano Roosevelt

“Luckiest Man” by Lou Gehrig

Demonstration

The Way to Cook with Julia Child

This Old House with Bob Vila

Bill Nye the Science Guy with Bill Nye

- Games, topic printables & more

- The 4 main speech types

- Example speeches

- Commemorative

- Declamation

- Demonstration

- Informative

- Introduction

- Student Council

- Speech topics

- Poems to read aloud

- How to write a speech

- Using props/visual aids

- Acute anxiety help

- Breathing exercises

- Letting go - free e-course

- Using self-hypnosis

- Delivery overview

- 4 modes of delivery

- How to make cue cards

- How to read a speech

- 9 vocal aspects

- Vocal variety

- Diction/articulation

- Pronunciation

- Speaking rate

- How to use pauses

- Eye contact

- Body language

- Voice image

- Voice health

- Public speaking activities and games

- Blogging Aloud

- About me/contact

Informative speech examples

4 types of informative speeches: topics and outlines

By: Susan Dugdale | Last modified: 08-05-2023

The primary purpose of an informative speech is to share useful and interesting, factual, and accurate information with the audience on a particular topic (issue), or subject.

Find out more about how to do that effectively here.

What's on this page

The four different types of informative speeches, each with specific topic suggestions and an example informative speech outline:

- description

- demonstration

- explanation

What is informative speech?

- The 7 key characteristics of an informative speech

We all speak to share information. We communicate knowledge of infinite variety all day, every day, in multiple settings.

Teachers in classrooms world-wide share information with their students.

Call centers problem solve for their callers.

News outlets (on and offline) issue reports on local, national and international events and issues, people of interest, weather, traffic flow around cities...

Health care professionals explain the treatment of addictive behaviors, the many impacts of long Covid, the development of new treatments...

Specialist research scientists share their findings with colleagues at conferences.

A pastry chef demonstrates how to make perfect classic croissants.

The range of informative public speaking is vast! Some of us do it well. Some of us not so well - largely because we don't fully understand what's needed to present what we're sharing effectively.

Return to Top

The key characteristics of an informative speech

So, what are the key characteristics or essential elements, of this type of speech? There are seven.

1. Objectivity

The information you give is factual, neutral and objective. You make no attempt to persuade or push (advocate) a particular viewpoint.

Your personal opinions: feelings thoughts, or concerns about the topic you're presenting are not given. This is not a persuasive speech.

As an example, here's an excerpt from a Statistics Department report on teenage births in New Zealand - the country I live in.

Although it's a potentially a firecracker subject: one arousing all sorts of emotional responses from outright condemnation of the girls and their babies to compassionate practical support, the article sticks to the facts.

The headline reads: "Teenage births halved over last decade"

"The number of teenage women in New Zealand giving birth has more than halved over the last decade, Stats NZ said today.

There were 1,719 births registered to teenage women (those aged under 20 years) in 2022, accounting for around 1 in every 34 births that year. In 2012, there were 3,786 births registered to teenage mothers, accounting for around 1 in every 16 births that year."

For more see: Statistics Department NZ - Teenage births halved over last decade

You present your information clearly and concisely, avoiding jargon or complex language that may confuse your audience.

The candidate gave a rousing stump speech , which included a couple of potentially inflammatory statements on known wedge issues .

If the audience is familiar with political jargon that sentence would be fine. If they're not, it would bewilder them. What is a 'stump speech' or a 'wedge issue' ?

Stump speech: a candidate's prepared speech or pitch that explains their core platform.

Wedge issue: a controversial political issue that divides members of opposing political parties or the same party.

For more see: political jargon examples

3. Relevance

The content shared in your speech should be relevant and valuable. It should meet your audience's needs or spark their curiosity.

If the audience members are vegetarians, they're highly unlikely to want to know anything about the varying cuts of beef and what they are used for.

However, the same audience might be very interested in finding out more about plant protein and readily available sources of it.

4. Organizational pattern

The speech should have a logical sequential structure with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

If I am giving a demonstration speech on how to bake chocolate chip cookies, to be effective it needs to move through each of the necessary steps in the correct order.

Beginning with how to spoon the mixture on to the tray, or how to cool the cookies on a wire rack when you've taken them out of the oven, is confusing.

5. Research and credibility

Informative speeches are based on thorough research and reliable sources to ensure accuracy and credibility. And sources need to be properly cited.

My friend told me, my mother says, or I saw it on Face Book is neither authoritative nor enough. ☺

Example: My speech is on literacy rates in USA. To be credible I need to quote and cite reputable sources.

- https://www.apmresearchlab.org/10x-adult-literacy

- https://www.thinkimpact.com/literacy-statistics/

6. Visual aids

Slides, charts, graphs, or props are frequently used to help the audience fully understand what they're being told.

For example, an informative speech on the rise and fall of a currency's daily exchange rate is made a great deal easier to follow and understand with graphs or charts illustrating the key points.

Or for a biographical speech, photos of the person being talked about will help hold the attention of your audience.

7. Effective delivery

To be effective your speech needs to be delivered in a way that captures and hold the audience's attention. That means all aspects of it have been rehearsed or practiced.

If you're demonstrating, you've gone through every step to ensure you have the flow of material right.

If you're using props (visual aids) of any sort you've made sure they work. Can they be seen easily? Do they clearly illustrate the point you're making?

Is your use of the stage (or your speaking space) good? Does your body language align with your material? Can your voice be heard? Are you speaking clearly?

Pulling together a script and the props you're going to use is only part of the task of giving a speech. Working on and refining delivery completes it.

To give a successful speech each of these seven aspects needs to be fine-tuned: to hook your audience's interest, to match their knowledge level, your topic, your speech purpose and, fit within the time constraints you've been given.

Types of informative speeches

There are four types of informative speeches: definition, description, explanation and demonstration. A speech may use one, or a mix of them.

1. Informing through definition

An informative speech based on definition clearly, and concisely, explains a concept * , theory, or philosophy. The principal purpose is to inform the audience, so they understand the main aspects of the particular subject being talked about.

* Definition of concept from the Cambridge dictionary - an abstract principle or idea

Examples of topics for definition or concept speeches

A good topic could be:

- What is global warming?

- What are organics?

- What are the core beliefs of Christianity?

- What is loyalty?

- What is mental health?

- What is modern art?

- What is freedom?

- What is beauty?

- What is education?

- What are economics?

- What is popular culture?

These are very broad topic areas- each containing multiple subtopics, any of which could become the subject of a speech in its own right.

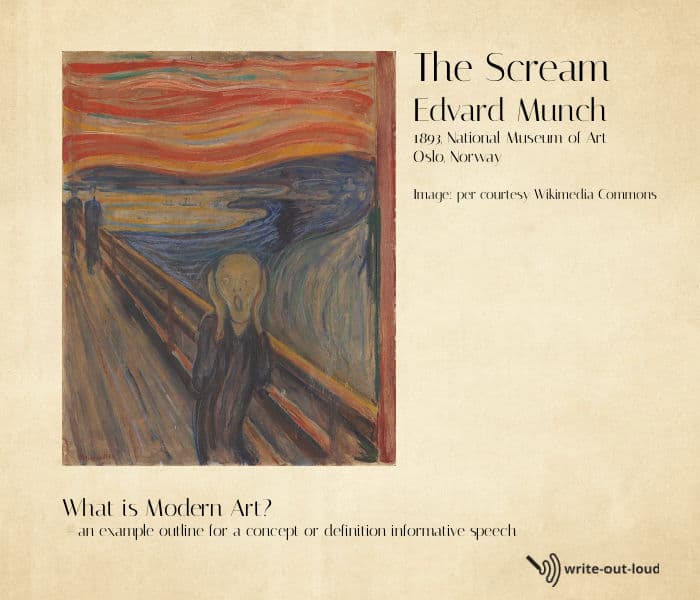

Example outline for a definition or concept informative speech

Speech title:.

What is modern art?

- people who want an introductory overview of modern art to help them understand a little more about what they're looking at - to place artists and their work in context

Specific purpose:

- to provide a broad outline/definition of modern art

Modern art refers to a broad and diverse artistic movement that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and continued to develop throughout the 20th century.

It is characterized by a radical departure from traditional artistic styles and conventions and encompasses a wide range of artistic styles, techniques, and media, reflecting the cultural, social, and technological changes of the time.

Key characteristics or main points include:

- Experimentation and innovation : Modern artists sought to break away from established norms and explore new ways of representing the world. They experimented with different materials, techniques, and subjects, challenging the boundaries of traditional art forms.

- Abstraction : Modern art often features abstract and non-representational elements, moving away from realistic depictions. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian explored pure abstraction, using shapes, lines, and colors to convey emotions and ideas.

- Expression of the inner self : Many modern artists aimed to convey their inner emotions, thoughts, and experiences through their work. This led to the development of various movements like Expressionism (See work of Evard Munch) and Surrealism (See work of Salvador Dali).

- Rejection of academic conventions : Artists sought to break free from the rigid rules of academic art and embrace more individualistic and avant-garde approaches. For example: Claude Monet, (1840 -1926) Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Édouard Manet

- Influence of industrialization and urbanization : The rapid changes brought about by industrialization and urbanization in the 19th and 20th centuries influenced modern art. Artists were inspired by the dynamics of the modern world and its impact, often negative, on human life.

- Multiple art movements : Modern art encompasses a wide array of movements and styles, for example Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art... Each movement brought its own unique perspective on art and society.

- Focus on concept and process : Modern artists began to emphasize the underlying ideas and concepts behind their work, giving greater importance to the creative process itself.

Modern art should not be confused with contemporary art. While modern art refers specifically to the artistic developments of the early to mid-20th century, contemporary art encompasses art created by artists living and working in the present day. The transition from modern art to contemporary art happened around the late 20th century- 1950s onward.

References:

- mymodernmet.com/abstract artists

- differencess.com/expressionism vs surrealism

- lorimcnee.com/artists who died without recognition

- industrial revolution the influence on art

- mymodernmet.com/important art movements

- theartstory.org/conceptual-art

- Image: The Scream, Edvard Munch

2. Informing through description

Informing through description means creating detailed, vivid verbal pictures for your audience to make what you're talking about come to life in the minds of those listening which in turn, will make your subject matter memorable.

Examples of good informative speech topics that could be used for descriptive speeches

- How I celebrate Christmas

- My first day at school

- My home town

- A time I feared for my life

- A time when I felt contented and happy

My first car

- An object I find fascinating: lotus shoes, bustles, corsets, panniers (These are historical items of women's clothing.)

- Working from home: the joys, the hazards

- My dream home, job, or holiday

- An event I'll never forget

- The most valuable or interesting thing I own

- Martin Luther King, Benjamin Franklin, President Lincoln... a notable person from the past or present, including someone you may know: a family member, friend or yourself, or a public figure (an artist, singer, dancer, writer, entrepreneur, inventor...)

Example outline for a descriptive informative speech

- to take the audience with me back to the time when we bought our first car and have them appreciate that car's impact on our lives

Central idea:

Our Austin A50 was a much-loved car

About the car:

- English, Austin A50, 1950ish model - curvy, solid, a matron of cars

Background to purchase:

- 1974 - we were 20 and 21 - young and broke

- The car cost $200 - a lot of money for me at that time. I raided my piggy bank to buy it.

- It was a trade up from the back of the motorbike - now I could sit side by side and talk, rather than sit behind and poke my husband, when I wanted to say important things like, 'Slow down', or 'I'm cold'. The romance of a motorbike is short-lived in winter. It diminishes in direct proportion to the mountain of clothes needing to be put on before going anywhere - coats, scarf, boots, helmet... And this particular winter was bitter: characterized by almost impenetrable grey fog and heavy frosts. It was so cold the insides of windows of the old house we lived in iced up.

- It was tri-colored - none of them dominating - bright orange on the bonnet, sky blue on the rear doors and the roof, and matt black on the front doors and the boot. (Bonus - no one would ever steal it - far too easily identified!)

- The chrome flying A proudly rode the bonnet.

- The boot, (trunk lid) was detachable. It came off - why I can't remember. But it needed to be opened to fill the tank, so it meant lifting it off at the petrol station and leaning it up against the boot while the tank filled, and then replacing it when done.

- There were bench seats upholstered in grey leather (dry and cracked) front and back with wide arm rests that folded down.

- The windows wound up and down manually and, in the rear, there were triangle shaped opening quarter-windows.

- The mouse-colored lining that had been on the doors and roof was worn, torn and in some patches completely missing. Dust poured in through the crevices when we drove on the metal roads that were common where we lived.

- It had a column gear change - 4 gears, a heater that didn't function, proper old-school semaphore trafficators indicators that flicked out from the top of the door pillars and blinked orange, a clutch that needed a strong push to get it down, an accelerator pedal that was slow to pick up and a top speed of around 50 mph.

Impact/benefits:

We called her Prudence. We loved, and remember, her fondly because:

- I was taught to drive in her - an unforgettable experience. I won the bunny hopping record learning to coordinate releasing the clutch and pressing down on the accelerator. Additionally, on metal roads, I found you needed to slow before taking corners. Sliding on two wheels felt precarious. The bump back down to four was a relief.

- We did not arrive places having to disrobe - take off layers of protective clobber.

- We could talk to each without shouting and NOW our road trips had a soundtrack - a large black portable battery driven tape player sat on the back parcel shelf blasting out a curious mix of Ry Cooder, Bach, Mozart's Flute Concerto, Janice Joplin... His choice. My choice. Bliss.

- My father-in-law suggested we park it down the street rather than directly outside his house when we visited. To him Prudence was one eccentricity too many! An embarrassment in front of the neighbors. ☺

- austinmemories.com/styled-33/styled-39/index.html

- wikipedia.org/Austin_Cambridge

- archive.org/1956-advertisement-for-austin-a-50

3. Informing through demonstration

Informing through demonstration means sharing verbal directions about how to do a specific task: fix, or make, something while also physically showing the steps, in a specific chronological order.

These are the classic 'show-n-tell', 'how to' or process speeches.

Examples of process speech topics:

- How to bake chocolate chip cookies

- How to use CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) correctly

- How to prepare and plant a tub of vegetables or flowers

- How to read a topographic map

- How to make a tik-tok reel

- How to knit a hat

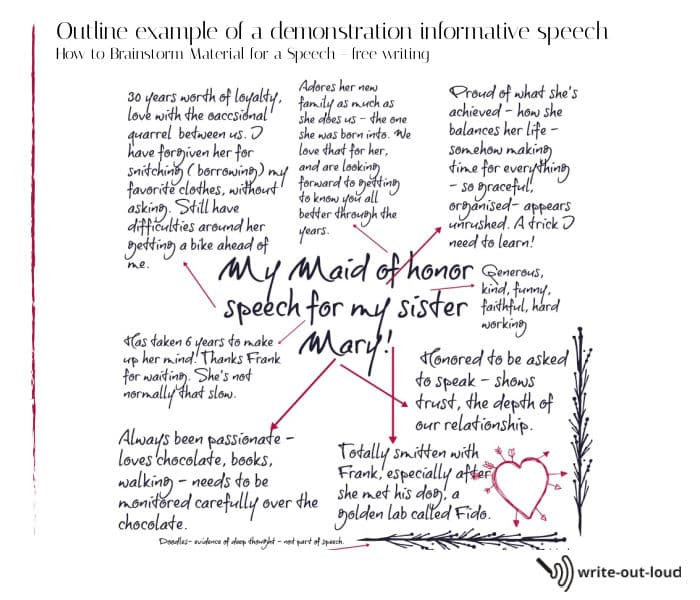

How to brainstorm material for a speech

For literally 100s more demonstration topic ideas

A demonstrative informative speech outline example

To demonstrate the brainstorming process and to provide practical strategies (helpful tips) for freeing and speeding up the generation of ideas

Main ideas:

Understanding brainstorming - explanation of what brainstorming is and its benefits

Preparing for brainstorming - the starting point - stating the problem or topic that needs brainstorming, working in a comfortable place free from distractions, encouraging open-mindedness and suspension of judgment.

Techniques for brainstorming : (Show and tell on either white board or with large sheets of paper that everyone can see) mind mapping, and free writing. Take topic ideas from audience to use.

Example : notes for maid of honor speech for sister

Benefits : Demonstrate how mind maps can help visually organize thoughts and connections, how free writing allows ideas to flow without stopping to judge them

Encourages quantity over quality - lots of ideas - more to choose from. May generate something you'd never have thought of otherwise.

Select, refine, develop (show and tell)

For more see: brainstorm examples

4. Informing through explanation

Informing through explanation is explaining or sharing how something works, came to be, or why something happened, for example historical events like the Civil War in the United States. The speech is made stronger through the use of visuals - images, charts of data and/or statistics.

Examples of explanatory informative speech topics

- How did the 1919 Treaty of Versailles contribute to the outbreak of World War Two?

- What led to The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865)?

- Why is there an increase in type two diabetes and problems associated with obesity in first world countries, for example, in UK and USA?

- How do lungs work?

- What causes heart disease?

- How electric vehicles work?

- What caused the Salem witch trials?

- How does gravitation work?

- How are rainbows formed?

- Why do we pay taxes?

- What is cyberbullying? Why is it increasing?

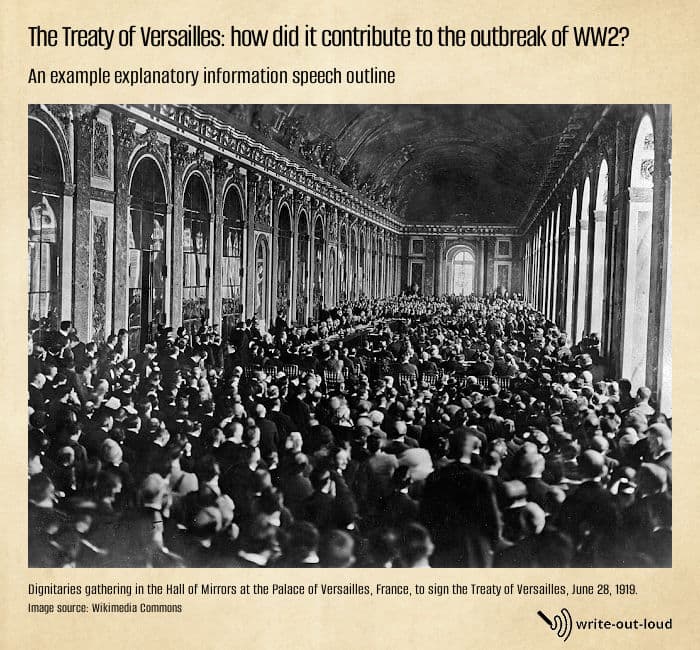

Example explanatory informative speech outline

The Treaty of Versailles: how did it contribute to the outbreak of World War Two

- to explain how the Treaty of Versailles (1919) was a significant causal factor leading up World War two

Central ideas:

Historical context : World War One, 'the war to end all wars' ended in 1918. The Allied Powers: USA, UK, France, Italy and Japan, met in Paris at the Paris Peace Conference 1919 to work out the details and consequences of the Treaty of Versailles, which would impact the defeated Central Powers, principally Germany.

These included:

- territorial boundary changes which stripped Germany of land in Europe, and established new nations - e.g. Poland and Czechoslovakia

- military restrictions - the disarmament of the German military, restrictions on weapons and technology, demilitarization of the Rhineland

- reparations - demands that they were unable to meet, plus being forced to accept a "war guilt" clause (Article 231) had an enormous impact, economically and psychologically. The country plunged into deep recession - albeit along with many other countries. (The Great Depression 1929-1939 which ended with the beginning of World War Two.)

The League of Nations - The League of Nations was an international diplomatic group developed after World War I as a way to solve disputes between countries before they erupted into open warfare. Despite being active in its set up, USA refused to join it - a stance that weakened its effectiveness.

Controversies within Germany: Public anger and resentment, plus political instability as result of reparations, territory loss and economic hardships

Controversies with Treaty partners: The Treaty's perceived fairness and effectiveness: Italy and Japan felt their settlements were inadequate compared to what had been taken by UK, USA and France.

The rise of 'isms' Simmering discontent eventually emerged as the rise of Fascism in Italy, Nazism in Germany and Statism (a mix of nationalism, militarism and “state capitalism”) in Japan.

Expansionist Nationalism Spread of expansionist nationalism - a state's right to increase its borders because it is superior in all ways. Therefore, Hitler was 'right' to take back what had previously been regarded as German territory (Czechoslovakia and Austria), and to go after more, all the while goading the Allied Powers to act. When his armies went into Poland, Britain declared war against Germany - 21 years after the end of the last.

- history.com/treaty-of-versailles-world-war-ii-guilt-effects

- tinyurl.com/Treaty-of-Versailles

- Image: tinyurl.com/signing-Treaty-of-Versailles

speaking out loud

Subscribe for FREE weekly alerts about what's new For more see speaking out loud

Top 10 popular pages

- Welcome speech

- Demonstration speech topics

- Impromptu speech topic cards

- Thank you quotes

- Impromptu public speaking topics

- Farewell speeches

- Phrases for welcome speeches

- Student council speeches

- Free sample eulogies

From fear to fun in 28 ways

A complete one stop resource to scuttle fear in the best of all possible ways - with laughter.

Useful pages

- Search this site

- About me & Contact

- Free e-course

- Privacy policy

©Copyright 2006-24 www.write-out-loud.com

Designed and built by Clickstream Designs

Informative Speech

Informative speech generator.

As a speaker, you’re given a special role. You’ve been given the power for your voice to be heard. For those who deliver an informative speech, this role can come as a challenge. Not only do you have to write a speech , but you also need to deliver it well. Of course, there’s also the challenge of making your speech interesting enough to capture the attention of your audience.

What Is an Informative Speech? An informative speech is a type of speech designed to educate the audience on a particular topic. It aims to provide interesting and useful information, ensuring the audience gains new knowledge or insights. Unlike persuasive speeches that seek to convince the audience of a particular viewpoint, informative speeches focus on explaining a subject matter clearly and objectively, without trying to influence the audience’s opinions or beliefs.

Download Informative Speech Bundle

An informative speech must be made memorable for it to be effective. Check out these examples and outlines of speeches that have tried to do just that. If they succeeded or failed, you’ll be the judge of that. Take what works and replicate it in your own speech drafts.

Informative Speech Format

Introduction.

Attention Getter : Start with a hook to grab the audience’s attention. This could be a surprising fact, an intriguing question, or a relevant story. Purpose Statement : Clearly state the purpose of your speech. This tells the audience exactly what they will learn. Preview : Briefly outline the main points you will cover. This gives the audience a roadmap of your speech.

First Main Point : Introduce your first key point. Support this point with evidence, such as data, examples, or expert quotes. Explain how this information is relevant to your topic. Second Main Point : Follow the same format as the first point, presenting new information and supporting evidence. Third Main Point : Continue with the format, ensuring each point is distinct and contributes to your overall topic. Remember to transition smoothly between points to maintain the flow of your speech.

Summary : Briefly recap the main points you’ve covered. This reinforces the information for the audience. Closing Statement : Conclude with a strong closing statement. You can reiterate the importance of the topic, share a concluding thought, or call to action if relevant.

Example of Informative Speech

The Impact of Technology on Society Good morning, everyone. Today, I am excited to delve into a topic that affects us all profoundly: the impact of technology on society. From the way we communicate to how we work and learn, technology has transformed every facet of our lives. But what does this mean for us as a society? Let’s explore this together. Imagine a world without smartphones, social media, or the internet. It’s hard, isn’t it? These technologies have become so integral to our daily lives that living without them seems almost unthinkable. My aim today is to shed light on both the positive and negative effects of technological advancements on our societal structures, behaviors, and relationships. We will explore three main areas: communication, privacy, and education. Technology has revolutionized the way we communicate. Social media platforms have made it easier than ever to stay connected with loved ones around the globe. While this keeps relationships alive across distances, it also raises questions about the depth and quality of these connections. The digital age has brought about significant concerns regarding privacy. Personal information is often collected by companies for targeted advertising, sometimes without explicit consent. This practice has led to a global conversation about the rights to privacy and the need for stricter regulations to protect personal information. Technology has transformed the educational landscape. Online learning platforms and digital textbooks make education more accessible than ever. However, this shift also presents challenges, such as the digital divide, where not all students have equal access to technology. In conclusion, technology’s impact on society is multifaceted, influencing our communication, privacy, and education. While it offers unprecedented opportunities for growth and connectivity, it also presents significant challenges that we must address. As we navigate this digital age, let us embrace the benefits of technology while also being mindful of its implications. By doing so, we can ensure that technological advancements serve to enhance, rather than diminish, the quality of our societal fabric. Thank you for your attention, and I look forward to any questions you might have.