The Real Differences Between Thesis and Hypothesis (With table)

A thesis and a hypothesis are two very different things, but they are often confused with one another. In this blog post, we will explain the differences between these two terms, and help you understand when to use which one in a research project.

As a whole, the main difference between a thesis and a hypothesis is that a thesis is an assertion that can be proven or disproven, while a hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research.

We probably need to expand a bit on this topic to make things clearer for you, let’s start with definitions and examples.

Definitions

A thesis is a statement or theory that is put forward as a premise to be maintained or proved. A thesis statement is usually one sentence, and it states your position on the topic at hand.

You may also like:

The best way to understand the slight difference between those terms, is to give you an example for each of them.

If your hypothesis is correct, then further research should be able to confirm it. However, if your hypothesis is incorrect, research will disprove it. Either way, a hypothesis is an important part of the scientific process.

The word “hypothesis” comes from the Greek words “hupo,” meaning “under”, and “thesis” that we just explained.

Argumentation vs idea

A thesis is usually the result of extensive research and contemplation, and seeks to prove a point or theory.

A hypothesis is only a statement that need to be tested by observation or experimentation.

5 mains differences between thesis and hypothesis

Thesis and hypothesis are different in several ways, here are the 5 keys differences between those terms:

So, in short, a thesis is an argument, while a hypothesis is a prediction. A thesis is more detailed and longer than a hypothesis, and it is based on research. Finally, a thesis must be proven, while a hypothesis does not need to be proven.

| Thesis | Hypothesis | |

|---|---|---|

| Can be argued | Cannot be argued, and don’t need to | |

| Generally longer | Generally shorter | |

| Generally more detailed | Generally more general | |

| Based on real research | Often just an opinion, not (yet) backed by science | |

| Must be proven | Don’t need to be proven |

Is there a difference between a thesis and a claim?

Is a hypothesis a prediction, what’s the difference between thesis and dissertation.

A thesis is usually shorter and more focused than a dissertation, and it is typically achieved in order to earn a bachelor’s degree. A dissertation is usually longer and more comprehensive, and it is typically completed in order to earn a master’s or doctorate degree.

What is a good thesis statement?

I am very curious and I love to learn about all types of subjects. Thanks to my experience on the web, I share my discoveries with you on this site :)

Similar Posts

Centaurs vs satyrs: what’s the real difference, 5 key distinctions between centaurs and minotaurs, what’s the difference between talent and skill, wales vs ireland: 7 key differences explained, 7 differences between greek and roman gods you don’t know, comedy vs. tragedy: what’s the difference (with table).

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

17 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Hi” best wishes to you and your very nice blog”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Thesis Action Plan New

- Academic Project Planner

Literature Navigator

Thesis dialogue blueprint, writing wizard's template, research proposal compass.

- Why students love us

- Rebels Blog

- Why we are different

- All Products

- Coming Soon

How Do You Write an Hypothesis? Detailed Explanation and Examples

Writing a hypothesis is a fundamental step in the scientific research process. It serves as a tentative explanation or prediction that can be tested through experimentation and observation. A well-crafted hypothesis provides a clear direction for research and helps in drawing meaningful conclusions. This article will guide you through the process of writing a hypothesis, including understanding its concept, formulating it, and avoiding common pitfalls, with illustrative examples from various fields of study.

Key Takeaways

- A hypothesis is a testable and falsifiable statement that predicts an outcome based on certain conditions.

- There are different types of hypotheses, including null, alternative, and directional hypotheses, each serving a specific purpose in research.

- Formulating a hypothesis involves identifying research questions, conducting preliminary research, and crafting a clear and precise statement.

- A strong hypothesis is characterized by its testability, clarity, precision, and relevance to the research objectives.

- Common pitfalls in hypothesis writing include vague statements, overly complex hypotheses, and lack of testability.

Understanding the Concept of a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a foundational element in scientific research, serving as a preliminary statement that proposes a potential relationship between variables. It is essential for guiding the direction of your study and providing a basis for data collection and analysis.

Steps to Formulate a Hypothesis

Identifying research questions.

The first step in formulating a hypothesis is to identify your research question . This involves observing the subject matter and recognizing patterns or relationships between variables. Crafting a clear, testable, and grounded hypothesis is essential for research success. By pinpointing the exact question you aim to answer, you lay the foundation for a focused and effective hypothesis.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Once you have your research question, the next step is to conduct preliminary research. This involves gathering as much information as possible about the topic. Evaluate these observations to identify potential causes and effects related to your research question. This stage helps you understand the existing knowledge and gaps, which is crucial for developing a well-informed hypothesis.

Formulating the Hypothesis Statement

After conducting preliminary research, you can begin formulating your hypothesis statement. This statement should clearly define the variables involved and the expected relationship between them. Ensure that your hypothesis is specific, testable, and falsifiable. A well-crafted hypothesis not only guides your research but also provides a clear direction for your experimental design and data collection methods.

Characteristics of a Strong Hypothesis

A strong hypothesis is essential for guiding your research and ensuring that your study is both meaningful and scientifically valid. Here are the key characteristics that define a robust hypothesis:

Testability and Falsifiability

A strong hypothesis must be testable, meaning you can design experiments to verify or refute it. Falsifiability is equally important; there should be a possibility to collect data that could disprove the hypothesis. This ensures that your hypothesis is grounded in empirical research rather than mere speculation.

Clarity and Precision

Your hypothesis should be clear and precise, leaving no room for ambiguity. This clarity helps in designing experiments and interpreting results. A well-defined hypothesis often begins with a specific research question and is articulated in simple, straightforward language.

Relevance to Research Objectives

A strong hypothesis is directly related to your research objectives. It should address the core question of your study and be aligned with the goals you aim to achieve. This relevance ensures that your hypothesis is not just an isolated statement but a crucial part of your overall research framework.

Common Pitfalls in Hypothesis Writing

When crafting a hypothesis, it's crucial to avoid common mistakes that can undermine your research. Vague statements are a frequent issue; they lack the specificity needed to be testable. For instance, saying "exercise improves health" is too broad. Instead, specify the type of exercise and the health outcome you are measuring.

Overly complex hypotheses can also be problematic. A hypothesis should be straightforward and focused. If it includes too many variables or conditions, it becomes difficult to test and analyze. Simplify your hypothesis to ensure clarity and feasibility.

Another major pitfall is the lack of testability. A hypothesis must be testable through empirical methods. If you cannot design an experiment or collect data to support or refute your hypothesis, it is not scientifically valid. Ensure your hypothesis can be tested with the resources and methods available to you.

Examples of Well-Written Hypotheses

In this section, you will explore various examples of well-crafted hypotheses across different fields of study. Understanding these examples will help you grasp the nuances of formulating a strong hypothesis.

Hypotheses in Natural Sciences

A well-written hypothesis in the natural sciences is both specific and testable. For instance, consider the hypothesis: "If plants are exposed to higher levels of sunlight, then their growth rate will increase." This statement clearly defines the variables and the expected relationship between them, making it a robust hypothesis for experimental testing.

Hypotheses in Social Sciences

In the social sciences, hypotheses often address complex human behaviors and societal trends. An example of a good hypothesis in this field is: "Individuals who participate in regular physical activity are more likely to report higher levels of mental well-being." This hypothesis is specific, testable, and relevant to the research objectives, providing a clear direction for the study.

Hypotheses in Applied Research

Applied research focuses on practical problem-solving. A strong hypothesis in this area might be: "Implementing a new software system will reduce the time required to complete administrative tasks by 20%." This hypothesis is not only testable but also directly applicable to real-world scenarios, making it highly valuable for applied research.

By examining these examples, you can better understand how to construct hypotheses that are clear, precise, and aligned with your research goals.

Testing and Refining Your Hypothesis

Designing experiments.

Before you dive into any experiment, you first formulate what you think will happen. This is where your hypothesis comes into play. A hypothesis in experimental design is essentially a testable prediction. Ensure that your hypothesis has clear and relevant variables, identifies the relationship between its variables, and is specific and testable. Designing a robust experiment involves controlling the independent variable and observing the dependent variable to validate or refute your hypothesis.

Data Collection Methods

Once your experiment is designed, the next step is to collect data. This involves choosing appropriate methods to gather data that will support or refute your hypothesis. Whether you use surveys, observations, or experiments, the key is to ensure that your data collection methods are reliable and valid. Remember, the priority of any scientific research is the conclusion, so collect data meticulously.

Analyzing Results and Making Adjustments

After data collection, the next step is to analyze the results. This involves statistical analysis to determine whether the data supports your hypothesis. If the data does not support your hypothesis, do not worry. This is a normal part of the scientific method. You may need to refine your hypothesis based on the findings. Use the results to identify weaknesses in your hypothesis and revise it if necessary. This iterative process helps in honing a more accurate and testable hypothesis.

The Importance of Hypotheses in Academic Writing

In academic writing, hypotheses serve as foundational elements that guide the direction and structure of your research. A well-formulated hypothesis not only provides a clear focus for your study but also helps in organizing your research methods and analysis. This is crucial for ensuring that your research remains coherent and targeted.

Guiding Research Direction

A hypothesis plays an important role in the scientific method by helping to create an appropriate experimental design. By establishing a specific, testable statement, you can streamline your research process and avoid unnecessary detours. This focused approach is essential for producing meaningful and reliable results.

Facilitating Critical Thinking

Formulating a hypothesis requires you to engage in critical thinking and problem-solving. This process helps you to clarify your research questions and objectives, making your study more robust and intellectually rigorous. It also encourages you to consider various outcomes and their implications, thereby enhancing the depth of your analysis.

Enhancing Academic Rigor

A well-constructed hypothesis adds a layer of academic rigor to your work. It demonstrates that you have a clear understanding of the theoretical framework and existing literature related to your topic. This not only strengthens your argument but also makes your research more credible and persuasive. In essence, a strong hypothesis is a testament to the quality and seriousness of your academic endeavor.

In academic writing, hypotheses play a crucial role in guiding research and providing a clear focus for your study. They help in formulating research questions and determining the direction of your investigation. If you're struggling with your thesis and need a structured approach, our Thesis Action Plan is here to help. Visit our website to claim your special offer now and overcome the challenges of thesis writing with ease.

In conclusion, writing a hypothesis is a fundamental step in the scientific research process that requires careful consideration and a structured approach. By observing the subject, identifying variables, and formulating a clear and testable statement, researchers can lay a solid foundation for their experiments. A well-crafted hypothesis not only guides the research but also provides a framework for analyzing results and drawing meaningful conclusions. As demonstrated in this article, understanding the components and steps involved in hypothesis writing is crucial for academic success and contributes significantly to the advancement of knowledge in various fields. By following the detailed explanations and examples provided, students and researchers can enhance their ability to construct effective hypotheses, thereby improving the quality and impact of their scientific inquiries.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a hypothesis.

A hypothesis is a statement that predicts the outcome of a scientific study. It is an educated guess based on prior knowledge and observations.

Why is a hypothesis important in scientific research?

A hypothesis provides a focused direction for research. It helps researchers make predictions that can be tested through experiments and observations, thereby advancing scientific knowledge.

What are the types of hypotheses?

There are several types of hypotheses, including null hypotheses, alternative hypotheses, directional hypotheses, and non-directional hypotheses. Each serves a different purpose in research.

How do you formulate a hypothesis?

Formulating a hypothesis involves identifying a research question, conducting preliminary research, and then crafting a clear and testable statement that predicts an outcome.

What makes a hypothesis strong?

A strong hypothesis is testable, falsifiable, clear, precise, and relevant to the research objectives. It should be specific enough to be tested but broad enough to cover the scope of the research.

What are common pitfalls in writing a hypothesis?

Common pitfalls include making vague statements, creating overly complex hypotheses, and failing to ensure that the hypothesis is testable.

Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: A Fun and Informative Guide

Unlocking the Power of Data: A Review of 'Essentials of Modern Business Statistics with Microsoft Excel'

Discovering Statistics Using SAS: A Comprehensive Review

How to Deal with a Total Lack of Motivation, Stress, and Anxiety When Finishing Your Master's Thesis

Mastering the First Step: How to Start Your Thesis with Confidence

Thesis Revision Made Simple: Techniques for Perfecting Your Academic Work

Thesis Action Plan

Integrating Calm into Your Study Routine: The Power of Mindfulness in Education

How to determine the perfect research proposal length.

- Blog Articles

- Affiliate Program

- Terms and Conditions

- Payment and Shipping Terms

- Privacy Policy

- Return Policy

© 2024 Research Rebels, All rights reserved.

Your cart is currently empty.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

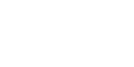

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

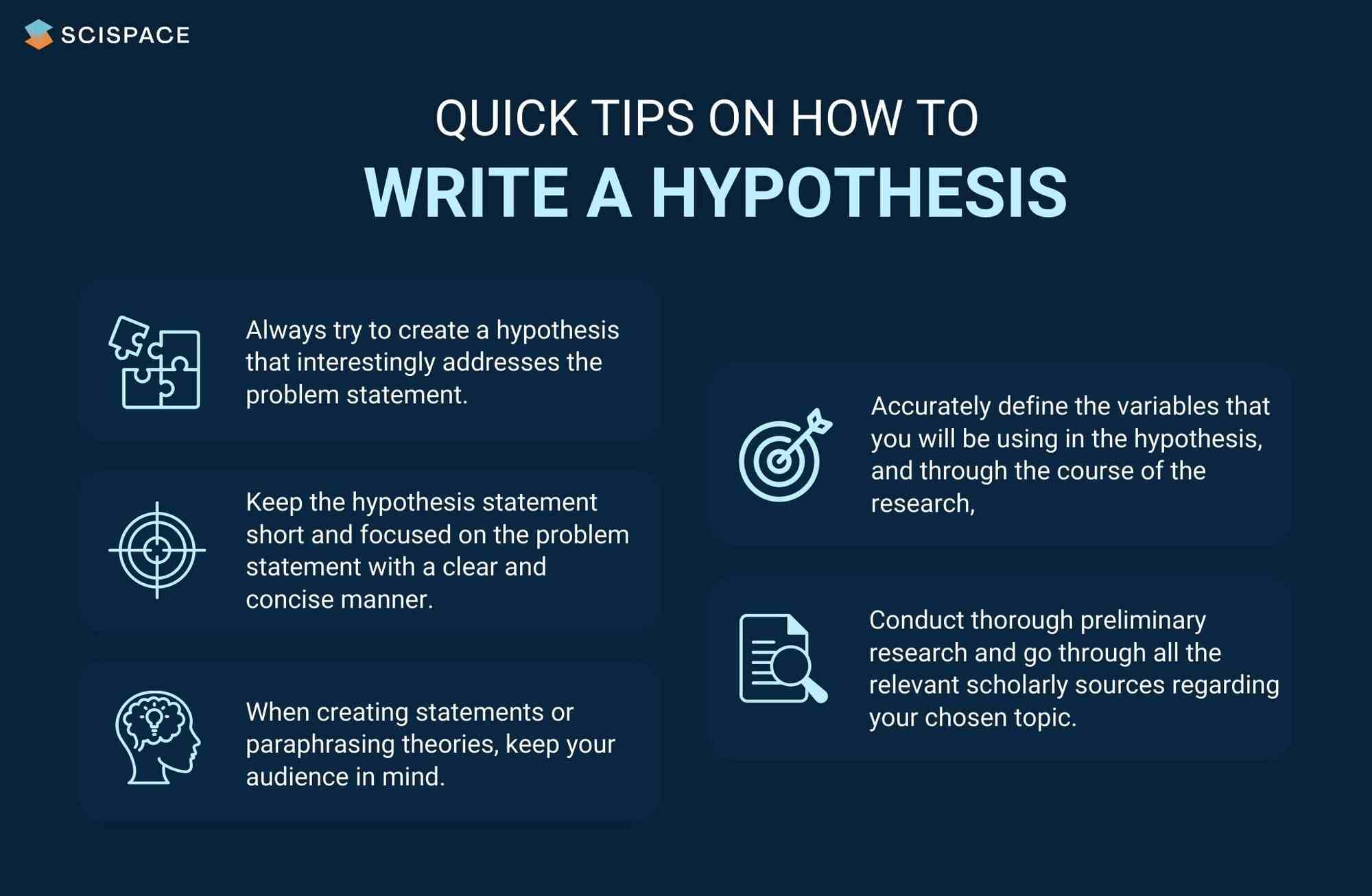

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

| Research question | Hypothesis | Null hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| What are the health benefits of eating an apple a day? | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will result in decreasing frequency of doctor’s visits. | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will have no effect on frequency of doctor’s visits. |

| Which airlines have the most delays? | Low-cost airlines are more likely to have delays than premium airlines. | Low-cost and premium airlines are equally likely to have delays. |

| Can flexible work arrangements improve job satisfaction? | Employees who have flexible working hours will report greater job satisfaction than employees who work fixed hours. | There is no relationship between working hour flexibility and job satisfaction. |

| How effective is secondary school sex education at reducing teen pregnancies? | Teenagers who received sex education lessons throughout secondary school will have lower rates of unplanned pregnancy than teenagers who did not receive any sex education. | Secondary school sex education has no effect on teen pregnancy rates. |

| What effect does daily use of social media have on the attention span of under-16s? | There is a negative correlation between time spent on social media and attention span in under-16s. | There is no relationship between social media use and attention span in under-16s. |

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

PSC 352: Introduction to Comparative Politics

- Getting Started

- Comparative Politics Overview

- Current World/Political News Feeds

- Choose a country

What is the difference between a thesis & a hypothesis?

- Find Books/eBooks

- Find Articles, Reports & Documents

- Find Statistics

- Find Poll & Survey Results

- Evaluate Your Sources

- Cite Your Sources

B oth the hypothesis statement and the thesis statement answer the research question of the study. When the statement is one that can be proved or disproved, it is an hypothesis statement. If, instead, the statement specifically shows the intentions/objectives/position of the researcher, it is a thesis statement.

A hypothesis is a statement that can be proved or disproved. It is typically used in quantitative research and predicts the relationship between variables.

A thesis statement is a short, direct sentence that summarizes the main point or claim of an essay or research paper. It is seen in quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research. A thesis statement is developed, supported, and explained in the body of the essay or research report by means of examples and evidence.

Every research study should contain a concise and well-written thesis statement. If the intent of the study is to prove/disprove something, that research report will also contain an hypothesis statement.

Jablonski , Judith. What is the difference between a thesis statement and an hypothesis statement? Online Library. American Public University System. Jun 16, 2014. Web. http://apus.libanswers.com/faq/2374

Let’s say you are interested in the conflict in Darfur, and you conclude that the issues you wish to address include the nature, causes, and effects of the conflict, and the international response. While you could address the issue of international response first, it makes the most sense to start with a description of the conflict, followed by an exploration of the causes, effects, and then to discuss the international response and what more could/should be done.

This hypothetical example may lead to the following title, introduction, and statement of questions:

Conflict in Darfur: Causes, Consequences, and International Response This paper examines the conflict in Darfur, Sudan. It is organized around the following questions: (1) What is the nature of the conflict in Darfur? (2) What are the causes and effects of the conflict? (3) What has the international community done to address it, and what more could/should it do?

Following the section that presents your questions and background, you will offer a set of responses/answers/(hypo)theses. They should follow the order of the questions. This might look something like this, “The paper argues/contends/ maintains/seeks to develop the position that...etc.” The most important thing you can do in this section is to present as clearly as possible your best thinking on the subject matter guided by course material and research. As you proceed through the research process, your thinking about the issues/questions will become more nuanced, complex, and refined. The statement of your theses will reflect this as you move forward in the research process.

So, looking to our hypothetical example on Darfur:

The current conflict in Darfur goes back more than a decade and consists of fighting between government-supported troops and residents of Darfur. The causes of the conflict include x, y, and z. The effects of the conflict have been a, b, and c. The international community has done 0, and it should do 1, 2, and 3.

Once you have setup your thesis you will be ready to begin amassing supporting evidence for you claims. This is a very important part of the research paper, as you will provide the substance to defend your thesis.

- << Previous: Choose a country

- Next: Find Books/eBooks >>

- Last Updated: Aug 6, 2024 3:25 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mssu.edu/PSC352

This site is maintained by the librarians of George A. Spiva Library . If you have a question or comment about the Library's LibGuides, please contact the site administrator .

- Richard G. Trefry Library

- Writing & Citing

Q. What is the difference between a thesis statement and a hypothesis statement?

- Course-Specific

- Textbooks & Course Materials

- Tutoring & Classroom Help

- 1 Artificial Intelligence

- 43 Formatting

- 5 Information Literacy

- 13 Plagiarism

- 23 Thesis/Capstone/Dissertation

Answered By: APUS Librarians Last Updated: Apr 15, 2022 Views: 129108

Both the hypothesis statement and the thesis statement answer a research question.

- A hypothesis is a statement that can be proved or disproved. It is typically used in quantitative research and predicts the relationship between variables.

- A thesis statement is a short, direct sentence that summarizes the main point or claim of an essay or research paper. It is seen in quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research. A thesis statement is developed, supported, and explained in the body of the essay or research report by means of examples and evidence.

Every research study should contain a concise and well-written thesis statement. If the intent of the study is to prove/disprove something, that research report will also contain a hypothesis statement.

NOTE: In some disciplines, the hypothesis is referred to as a thesis statement! This is not accurate but within those disciplines it is understood that "a short, direct sentence that summarizes the main point" will be included.

For more information, see The Research Question and Hypothesis (PDF file from the English Language Support, Department of Student Services, Ryerson University).

How do I write a good thesis statement?

How do I write a good hypothesis statement?

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 115 No 63

writing tutor

Related Topics

Need personalized help? Librarians are available 365 days/nights per year! See our schedule.

Learn more about how librarians can help you succeed.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question

The first step is to identify the research question that you want to answer through your study. This question should be clear, specific, and focused. It should be something that can be investigated empirically and that has some relevance or significance in the field.

Conduct a Literature Review

Before writing your hypothesis, it’s essential to conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. This will help you to identify the research gap and formulate a hypothesis that builds on existing knowledge.

Determine the Variables

The next step is to identify the variables involved in the research question. A variable is any characteristic or factor that can vary or change. There are two types of variables: independent and dependent. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated or changed by the researcher, while the dependent variable is the one that is measured or observed as a result of the independent variable.

Formulate the Hypothesis

Based on the research question and the variables involved, you can now formulate your hypothesis. A hypothesis should be a clear and concise statement that predicts the relationship between the variables. It should be testable through empirical research and based on existing theory or evidence.

Write the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is the opposite of the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis that you are testing. The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference or relationship between the variables. It is important to write the null hypothesis because it allows you to compare your results with what would be expected by chance.

Refine the Hypothesis

After formulating the hypothesis, it’s important to refine it and make it more precise. This may involve clarifying the variables, specifying the direction of the relationship, or making the hypothesis more testable.

Examples of Hypothesis

Here are a few examples of hypotheses in different fields:

- Psychology : “Increased exposure to violent video games leads to increased aggressive behavior in adolescents.”

- Biology : “Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will lead to increased plant growth.”

- Sociology : “Individuals who grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status will have higher levels of education and income as adults.”

- Education : “Implementing a new teaching method will result in higher student achievement scores.”

- Marketing : “Customers who receive a personalized email will be more likely to make a purchase than those who receive a generic email.”

- Physics : “An increase in temperature will cause an increase in the volume of a gas, assuming all other variables remain constant.”

- Medicine : “Consuming a diet high in saturated fats will increase the risk of developing heart disease.”

Purpose of Hypothesis

The purpose of a hypothesis is to provide a testable explanation for an observed phenomenon or a prediction of a future outcome based on existing knowledge or theories. A hypothesis is an essential part of the scientific method and helps to guide the research process by providing a clear focus for investigation. It enables scientists to design experiments or studies to gather evidence and data that can support or refute the proposed explanation or prediction.

The formulation of a hypothesis is based on existing knowledge, observations, and theories, and it should be specific, testable, and falsifiable. A specific hypothesis helps to define the research question, which is important in the research process as it guides the selection of an appropriate research design and methodology. Testability of the hypothesis means that it can be proven or disproven through empirical data collection and analysis. Falsifiability means that the hypothesis should be formulated in such a way that it can be proven wrong if it is incorrect.