Healthcare and Hospital Cafeteria Design Consultants

SERVING YOUR AREA

Ready to improve or build your food service operations? Contact us to talk to one of our experts right away!

or call 800-899-6604

Balancing Regulations, Labor, and Costs

Hospital kitchens and cafeterias represent some of the most demanding commercial cooking and dining spaces. Not only do they need to meet the needs of patients with restricted diets, but they must also be capable of efficiently providing a variety of menu items for staff and visitors. Hospital kitchens must also be capable of complying with strict hygienic standards.

Rapids Contract has addressed these demands and more in designing and installing hospital kitchens and cafeterias. While designing spaces, we balance regulations, labor and costs with the need for smooth workflow and service patterns. And, with our decades of experience and dedication to communication, we have forged relationships with contractors and fabricators to provide efficient installation and to elevate any kitchen or cafeteria into an attractive custom design.

Flexible, Labor-Saving Healthcare Kitchen Designs

Commercial healthcare dining has evolved to place an emphasis on labor-saving flexibility in the kitchen, ordering, and service areas. Rapids Contract’s designers know how to incorporate practical, functional time- and energy-savers into versatile spaces suited for room service orders, grab-and-go service, and dine-in visitors and staff.

Our CADD technology enables you to view your kitchen design in three dimensions well before the build begins. Our LEED-certified designer selects the best available on-demand technology that meets code and saves on costs. This includes eco scrappers, a green replacement for the commercial disposal, and other state-of-the-art appliances and lighting.

Get Ideas From Experts in The Industry

Experience with all types of facilites.

Streamlined Dine-In, Room Service, and Pick Up

For today’s hospital patients and cafeteria visitors, flexibility and flow are key to fast, convenient service. Let us show you how to streamline remote ordering for hospital room service and make it easy for visitors to find and purchase a variety of hot and cold foods. In addition, we can help you select energy-efficient equipment for display and contactless pickup save money over the long run and reduce the pressure on kitchen staff.

Project Management and Communication

One of the most important considerations in selecting a hospital kitchen design firm is how they will manage your project. At Rapids Contract, our project manager will be with you throughout the entire process. He or she will be on site during construction to coordinate with the trades, from fabricators to installers, and architects to general contractors. We take relationships with you and these key partners seriously, guiding the buildout for your hospital kitchen and cafeteria to align with your specifications, timeline, and budget.

FAQs for Healthcare Cafeterias

How long does it take to install a healthcare kitchen.

The time it takes to install a healthcare cafeteria can vary widely based on several factors, including the size of the kitchen, the complexity of the design, the type of equipment being installed, local regulations and permits, the availability of contractors and skilled labor, and the efficiency of the installation process.

In general, smaller and less complex kitchens in an existing foodservice space might take a few weeks to a couple of months to install, while larger and more intricate kitchens could take several months. Here are some key factors that can influence the installation timeline:

1. Design and Planning: The design phase can significantly impact the installation time. If the kitchen’s layout and design are well-prepared in advance, it can help streamline the installation process.

2. Equipment Selection and Availability: The type of equipment needed for the kitchen can affect the timeline. If specialized or custom equipment is required, it might take longer to source and install.

3. Permits and Regulations: Obtaining necessary permits and complying with local regulations can sometimes be a time-consuming process that impacts the installation timeline.

4. Construction and Infrastructure: If any modifications or construction work is required to accommodate the kitchen, such as plumbing, electrical, or ventilation systems, this can add to the installation time.

5. Skilled Labor and Contractors: Availability of skilled contractors, electricians, plumbers, and other professionals can influence how quickly the installation can be completed.

6. Project Management: Efficient project management can help keep the installation on track and avoid delays.

7. Unforeseen Issues: Unexpected challenges or issues that arise during installation, such as equipment malfunctions or structural problems, can extend the timeline.

8. Size and Complexity: Larger kitchens with more intricate setups, multiple workstations, and specialized equipment can naturally take longer to install.

9. Coordination and Scheduling: Coordinating the various tasks involved in the installation, such as equipment delivery, construction work, and inspections, requires careful scheduling.

It’s recommended to work closely with a firm like Rapids who has solutions engineers, designers, project managers, project coordinators, and support teams experienced in commercial kitchen installations. we can provide a more accurate estimate based on the specific details of your project and help manage the process to ensure it’s completed as efficiently as possible.

How much does a healthcare kitchen cost?

The cost of setting up a healthcare cafeteria can vary widely depending on several factors, including the size of the kitchen, the type of cuisine you’ll be preparing, the quality of equipment and materials you choose, location, and local regulations. Here are some of the major cost considerations:

1. Location: The cost of commercial real estate can vary greatly based on the region, city, and neighborhood where you plan to set up your kitchen.

2. Size and Layout: The overall square footage and layout of the kitchen will impact costs. A larger kitchen will require more equipment, materials, and space planning.

3. Equipment: The cost of commercial kitchen equipment varies based on the type and brand. High-quality, specialized equipment can be more expensive. Equipment includes ovens, stoves, refrigerators, freezers, fryers, grills, ventilation systems, dishwashers, and more.

4. Ventilation and Exhaust Systems: Proper ventilation and exhaust systems are crucial for a commercial kitchen to ensure air quality and safety. These systems can be a significant cost factor.

5. Utilities and Infrastructure: Costs associated with plumbing, electrical work, and gas lines installation or modifications need to be considered.

6. Construction and Renovation: If you’re building or renovating a space to accommodate the kitchen, construction costs can vary based on the extent of the work required.

7. Permits and Regulatory Compliance: Obtaining permits and complying with health and safety regulations may incur fees.

8. Interior Design and Finishes: The quality of finishes, such as flooring, countertops, and wall coverings, can impact costs.

9. Furniture and Fixtures: If you’re setting up a restaurant or eatery within the kitchen space, the cost of furniture and fixtures for the dining area should also be considered.

10. Labor Costs: Labor costs include not only the salaries of kitchen staff but also costs for installation, construction, and any specialized services needed.

11. Contingency: It’s wise to budget for unexpected costs that may arise during the setup process.

Due to the many variables involved, it’s challenging to provide an exact figure. However, to give you a rough idea, setting up a basic small-scale commercial kitchen could start around $50,000 to $100,000. Larger, more complex kitchens with high-end equipment and finishes could cost several hundred thousand dollars or even more.

To get a more accurate estimate for your specific situation, it’s recommended to consult with our commercial kitchen design and construction professionals. We can assess your needs, provide cost breakdowns, and help you plan a budget that aligns with your goals.

What layout options are available when designing a healthcare kitchen?

When designing a healthcare cafeteria, the layout should prioritize efficiency, speed, and safety. There are several layout options to consider, each with its own advantages depending on the size of the space, the menu, and the workflow. Here are some common layout options:

1. Assembly Line or Linear Layout: This layout resembles an assembly line, with different stations for each step of the food preparation process. It’s ideal for fast food chains with a limited menu of items that can be prepared quickly. The workflow progresses in a linear fashion, from order taking to food assembly.

2. U-Shaped Layout: A U-shaped layout places the cooking equipment and prep stations along the three sides of a U shape, with the middle left open for movement. This allows cooks to access equipment and ingredients without having to cross paths frequently.

3. L-Shaped Layout: In an L-shaped layout, the kitchen equipment and workstations are arranged along two adjacent walls in an L configuration. This can be effective for smaller spaces and helps streamline the workflow between cooking and preparation areas.

4. Island Layout: An island layout positions equipment and stations in the center of the kitchen, allowing cooks to access equipment from all sides. It’s suitable for larger kitchens with ample space and can provide a more flexible workflow.

5. Zoned Layout: This layout divides the kitchen into distinct zones, each dedicated to a specific task such as cooking, preparation, dishwashing, and storage. It’s efficient for larger kitchens and helps prevent congestion by keeping different tasks separate.

6. Open Kitchen Layout: An open kitchen layout allows customers to see the food preparation process, which can add transparency and a sense of freshness. This layout requires careful organization to maintain a clean and presentable appearance.

7. Parallel Layout: In a parallel layout, equipment and stations are placed along two parallel lines. This is useful for kitchens with a linear workflow, where tasks progress from one end to the other.

8. Zone and Flow Layout: This layout combines zoned areas with a logical flow of food preparation. It ensures that tasks progress smoothly and avoids unnecessary backtracking.

9. Hybrid Layout: Depending on the specific needs of your restaurant, a combination of different layouts can be used to optimize space and workflow. For example, a U-shaped layout for cooking and an assembly line for order preparation.

Remember that the layout should be tailored to your restaurant’s unique requirements, menu items, and anticipated customer flow. It’s important to consider factors like the placement of cooking equipment, prep stations, serving areas, and storage to create a seamless and efficient kitchen environment. Consulting with Rapids’ professional kitchen designers and solutions engineers can help you make informed decisions and create a layout that maximizes productivity and safety.

Where do you get your supplies from?

You can obtain foodservice equipment and supplies from various sources, both online and offline. Here are some common options:

Online Retailers: There are numerous online retailers that specialize in selling foodservice equipment and supplies but clearly Rapids Wholesale’s Webstore is the best in the business! In fact, over 75% of the K-12 school systems in our home state utilize our website for ordering equipment and smallwares. We work neighboring state school buying groups and independent schools as well! Our team can prepare a “market basket” of items your school uses most and provide negotiated discount pricing on those items! Reach out to find out more!

Restaurant Supply Stores: These are specialized stores that offer a wide range of commercial kitchen equipment and supplies. You can find everything from cooking appliances to utensils, furniture, and cleaning supplies. Rapids currently has Restaurant Supply Store locations in St. Paul, MN and Marion, IA.

Wholesale Distributors: Some distributors cater specifically to businesses in the food industry. They often offer bulk purchasing options and may have discounts for larger orders. Rapids Account Management Team is standing by to assist.

When sourcing foodservice equipment and supplies, consider factors like price, quality, warranty, and customer reviews. Compare options from different sources to make informed decisions that align with your budget and needs. Additionally, be aware of any local regulations or codes that might affect the type of equipment you can use in your commercial kitchen.

Previous Work – University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital

When the University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital envisioned their cafe, they saw a welcoming environment that was not only easily able to handle the flow of patients and their families, but could also offer a number of meal options.

Rapids helped bring the plan to fruition using our cafeteria and kitchen design services, as well as our equipment and smallwares fulfillment program. Our dedicated team worked on both the cafeteria and the Level 12 kitchenette, ensuring both had the same high-end look and quality materials – including equipment that is all run on electric power.

LET'S FIND YOUR SOLUTION

Rapids Contract serves the United States with locations in Iowa, Minnesota, and Missouri!

Get in touch with one of our experts and let us know how we can help with any of your foodservice needs.

Talk to one of our experts right away and get immediate assistance. We are open Mon - Fri, 8am - 5pm CST.

How Hospital Food Service Can Improve Patient Experiences And Outcomes

Food is fundamental to the human experience, and that’s doubly true for the patient experience

By Michael Tolliver / Special to Healthcare Facilities Today

Hospital meatloaf and pudding jokes never seem to go away, do they? If today’s patients still expect hospital food “isn’t going to be that great,” as Press Ganey has found [1] , maybe there’s something to the staying power of hospital food jokes. Maybe they’re proof of an ever-fresh opportunity to emotionally connect with patients.

On the other hand, hospitals have a lot to prioritize when it comes to the patient experience, so why should food take so much focus? HCAHPS may not ask directly about food, but studies show food service quality contributes to overall satisfaction of a hospital stay, not to mention patient recovery. [2]

That interdependence of food service and patient experience makes sense. Food doesn’t poke or prod a patient. It offers a comforting choice. A menu is much easier to understand than treatment options, and ordering food is the chance to make a positive decision for yourself.

Delivering on that promise of a positive outcome is the goal of great food service. Food is fundamental to the human experience, and that’s doubly true for the patient experience, since nutrition is key to patient health. Almost half of all deaths attributed to heart disease, stroke, and Type 2 diabetes are linked to poor diet. [3]

So how are hospitals helping patients learn about long-term nutritional health? How are they making the most of that opportunity to connect with patients through food? And how are they making sure it benefits the bottom line and sticks with patients, improving outcomes? Here’s a specially prepared selection of choice strategies, so let’s dig in.

Stealth health

The general trend toward health-conscious consumption does put pressure on menu creation, but for many patients (along with their stressed family and friends), healthy options can’t compete with the desire for comfort food. Giving people what they want is usually a hallmark of great service, but hospitals have a clear interest in reducing the risk of readmission, and that means meeting nutritional standards that contribute to recovery.

But as parents and nurses know, providing healthy food doesn’t guarantee it’ll be eaten. More than half of patients leave half or more of their meals uneaten, according to a 2019 study. The same study also noted that diminished nutritional intake delayed recovery and increased risk of complications. [4]

People want French fries. Instead of taking choices away and increasing the chance that patients order something they don’t really want (and don’t end up eating), the “stealth health” strategy make fries, burgers, and comfort food like mac and cheese healthier. A lot of hospitals no longer deep fry, for instance, but the most successful “stealth health” strategies focus on the positive. An enhanced flavor model makes palatable options healthier, and healthy options more palatable.

The key to a successfully implemented enhanced flavor profile is finding ways to efficiently produce on demand at scale. Prioritizing healthy food and patient choice means being smart about costs. With nutritional needs in hand and creative chefs on board, menu plans need to take sourcing and logistics into account. Great food service teams apply clear metrics and analytics to find the efficiency and cost savings needed to keep quality food affordable.

Choosy patients choose information

There’s also expectation management for dietary restrictions, and the importance of having information at hand for patients and guests who want to make more informed choices. Informative labels are just the first step. Information technology is the next one. Access to menus online helps everyone compare choices for themselves. The best systems prioritize user access to up-to-date menu information, and speed the user experience with tools that sort for vegetarian, diabetic, or other key factors and restrictions (such as salt and fat content, or allergens).

Many hospitals are finding the personal touch does wonders. When a dietitian sits with a patient and talks through their needs and wants, that’s both a service win and a healthcare win. Low salt and less grease may taste different, but with an enhanced flavor profile, change doesn’t have to be bad. Setting expectations helps patients focus on the positive, instead of what’s missing. Following up the in-person attention with in-room touch menus or online access enables choice and showcases the quality menu planners work so hard to provide.

Here’s where quality food really shines. What the dietitian helps patients learn, the food helps them accept, with tasty options and great service.

Room service Is the way

Anyone can order almost anything from a smartphone. Patients of every age bracket want to order what they want when they want it, and hospital food is no exception. Instead of sending up trays of unordered food that staff will have to throw away later, a room service model gives patients choice.

The benefits of the room service model are clear. Less than half as much wasted food (29% waste with a traditional model against 12% for the room service model) means patients are getting significantly better nutrition. Moving Press Ganey scores from 64 th to 95 th for “quality of food” is also a pretty powerful indicator of the impact on patient experience. [5]

If “hotel-style” room service sounds like it’s more expensive to run, think about this: the benefits in the study above also came with a 15% decrease in patient meal costs. The increased costs of room service turn out to be mainly start-up costs in equipment, software and training. [6]

Once those initial costs are dealt with (or, perhaps better for the hospital, avoided by bringing on a service partner with technical scope and labor expertise already in place), food costs can be reduced by room service models by reducing stock and inventory and eliminating overproduction. [7]

Retail, retail, retail

If the patients are getting room service, how does the retail cafeteria impact the patient experience? Family members eat there. Nurses and staff eat there. Improved employee engagement scores are a clear chance to increase your HCAHPS top box scores: 85% of engaged hospital employees demonstrate a genuinely caring attitude with patients as opposed to only 38% of disengaged employees. [8] But when the cafeteria is terrible, people will say so, out loud, a lot. That impression sticks in the mind of patients and can color lots of other judgements. And let’s be honest, family members often fill out surveys for patients. If they had a bad experience in the retail area, they might overlook how great the room service was for the patient.

Rising food costs and budget cuts may be squeezing the bottom line, but the retail portion of hospital food service is a chance to put all that meal planning, logistics, and service to work increasing retail revenues. On-demand dishes and healthier options, alongside amenities like coffee kiosks and food carts, keep everyone satisfied.

Retail is the chance to capitalize more on all the logistics work you’re doing to locally source ingredients, cook from fresh, and enhance flavors for patients. Now you can replace that tired cafeteria experience, and deliver that café, bistro, or restaurant feel that draws people in and delivers.

In some locations, a hospital can become a true dining destination for the greater community. Especially if the community lacks healthier, affordable options, hospital dining can be a boon to seniors and other community members looking to improve eating habits. Hospitals can increase their draw by promoting their tasty, healthy menu for community groups.

Hospitals with great retail programs can often offer nutritious food to at-risk groups at prices lower than local restaurants, without having to subsidize meals. Outreach programs like this both serve the community and create efficiency by generating revenue when staff may normally be underutilized.

The real trend is production management

There’s lots of trends to spot. Authentic foods from across the cultural spectrum, celebrity chef recipes, even setting up gardens on-site to grow their own produce – there are a lot of great ideas out there. They all come with their own stumbling blocks and start-up costs. Making sure that innovative, expanded menu options work for your hospital and your patients takes production expertise. Great ideas must be adapted for the healthcare environment and made efficient with flexible, intelligent production management.

For instance, farmer’s markets and local sourcing still have to meet regulations and strict processes, like chain of custody (recording who has what to help ensure quality control). And when a menu relies on a certain ingredient, great production teams know how to adapt or shift menu strategies when it’s not available. Keeping taste and quality high while working with the reality on the ground efficiently puts the patient experience first.

And for dessert…

Hating hospital food may be as American as apple pie, but savvy hospital directors know that lower expectation is an opportunity to exceed it. Where hospitals used to subsidize food, including huge discounts for employees to eat there, rising costs of food and food preparation have put that model to bed. When it comes to the bottom line, everything can look like a cost center, but food service done well can be a revenue generator.

Driving patient satisfaction and reducing readmissions are a tall order for any department. The right menu, the right food sourcing, the right service model, every element takes planning, resources, and commitment to implement efficiently. The right partner is ready to dump legacy caterer worries and woes and bring innovation and excitement to the table.

Michael V. Tolliver is Vice President Healthcare Operations at ABM .

October 5, 2020

Topic Area: Food Service

Recent Posts

Hais are worse than you thought.

No standards exist requiring a hospital room to be free of bacteria or viruses in sufficient numbers to cause an infection.

Ground Broken on New El Paso VA Health Care Center

The healthcare facility is anticipated to be completed in 2028.

Authorities Issue Joint Advisory on RansomHub Ransomware

RansomHub has impacted at least 210 organizations across critical infrastructure sectors, including healthcare.

9 Steps to a Successful Healthcare Capital Project

Navigating the future of the healthcare industry can be challenging, but prioritizing these key drivers for healthcare capital projects can help senior leaders make future-proof choices.

Steward Health Care to Sell Wadley Regional Medical Center in Texarkana

The facility is being sold to CHRISTUS Health.

News & Updates | Webcast Alerts Building Technologies | & More!

All fields are required. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Awards + Events

- Architecture

- Interior Design

- Construction and Engineering

Operations and Facility Management

- Research and Theory

- Perspectives

- White Papers

- Ambulatory Care / Clinics

- Behavioral Health

- Cancer Care

- Emergency / Urgent Care

- Specialty Projects

- Landscaping / Exteriors

- FEATURED FIRMS

- Healthcare Design Showcase

- Breaking Through

- Remodel/Renovation Competition

- The HCD 10: Celebrating Healthcare Design Leaders

- HCD Product Innovation Awards

- HCD Conference + Expo

- Nightingale Awards

- Rising Star Competition

- HCD Webinar Schedule

- Furniture and Casegoods

- Building Products

- Ceiling and Wall Systems

- Infection Control

Good Taste: Designing Healthcare Dining Spaces

As competition surges among healthcare providers, delivering positive experiences for patients is inspiring projects that breathe new life into care spaces. But simultaneously, organizations are turning their attention to areas of the hospital that likewise improve staff and family satisfaction, and few spaces hold the potential to achieve this that the cafeteria does.

“The dining room in the hospital may not be a great source of revenue, but it does serve as an integral cog in the overall well-being and quality of the hospital services,” explains Yi Belanger, designer at Add Inc. , which is now with Stantec (Miami). “Patient and family member satisfaction ratings greatly rely on the overall experience of their hospital stay, and oftentimes, it means the hospital’s overall accommodations and service, including their dining space.”

On the flip side, hospitals with outdated dining facilities may suffer from perception coloring reality, leading patients and families to erroneously believe that the hospital itself is outdated.

A vast departure from the traditional single cafeteria line with limited food options and hours of operation, today’s hospital dining areas are designed as comfortable, hospitality-inspired spaces customized for the user experience. Embraced by staff and patient families, these spaces are viewed as a welcome amenity, particularly for those spending extended periods of time in the hospital.

Efficiency and flow To start, hospitals across the country are attempting to rectify the long-standing inefficiencies in cafeteria flow and service. Traditionally set up based on a lengthy serving line, entry and exit points were often unclear, and wandering patrons commonly threw a wrench in circulation.

To ensure a new space achieves optimal flow and space efficiencies, both in the serving/dining zones and back-of-house areas, Belanger says her team typically interviews the administrative, clinical, and kitchen staff to develop an understanding of workflow patterns in existing dining areas. Based on those conversations, the optimal amount of seating and square footage needed for circulation, serving, and egress emerges.

Another noted trend is breaking up the traditional food service line into multiple stations with varied food offerings: for example, a salad bar, prepackaged to-go meals, sandwich station, and condiment stands. “Signage can be used to effectively guide visitors, but the design team must create a flow that allows guests to visualize the menu offerings, traverse to the desired offering stations, and pay and exit from a controlled space in a minimal time frame. The design must also maximize the number of transactions within a specified time frame,” says David N. Moon, principal of Moon Mayoras Architects (San Diego).

Strategic seating When it comes to seating arrangements, the key is variety, incorporating options like a bar with stools, larger tables, smaller booths, and outdoor seating, if possible. “I like to create zones in these spaces for serving, dining, lounging, and personal space,” Belanger says. “These spaces can be equipped with movable furniture and modular systems that can be transformed for different functions during work hours and afterwards.”

Cindy Elkin, interior designer at RLF (Orlando), says that seating should support a variety of dining experiences and levels of social interaction. “To distinguish between these areas, we establish a flow of spaces and look at how we can manipulate the ceiling planes, wall boundaries, and seating heights to create spaces that are immediately identifiable as more intimate quiet areas or on-demand, energizing spaces,” she says.

For example, Kalloor recommends half-height walls to partition off small groupings of tables so that the numerous dining seats can be zoned into small compartments. These walls can also double as a barrier to shield these more private seating areas from traffic flow. “Patterned or colorful acrylic panels can also be used to serve as a vertical screen that helps to divide and organize space without the visual weight of a full wall,” she says.

To customize the space to specific user groups, Belanger recommends booth seating for the comfort and privacy of families, and unfixed tables and chairs in small and large clusters to support staff. Although preferences will vary from hospital to hospital, institutions generally require separate dining areas for doctors to support events like staff presentations, physician case studies, and educational programs often occurring during lunchtime. Some institutions may also require private areas for VIPs, such as hospital benefactors, foreign dignitaries, or celebrities.

Mastering materials As for how healthcare dining areas are being reimagined from an interiors perspective, the options for finishes are endless. “Dining spaces within a healthcare setting are the one place where designers can take more design risks,” says Margi Kaminski, senior associate vice president at RTKL (Chicago).

The materials palette can be much broader than that generally used in other healthcare spaces and may include accents such as high-gloss wall tiles in bold colors or patterned resin panels and textured glass. Kaminski also considers furnishings like sculptured chairs or decorative lighting for dining projects.

However, because dining spaces are housed within a high-use setting, designers must be “extra clever and creative in our material selections,” says Belanger, with furnishings and finishes specified that are durable and easily cleaned. “You want to create a space that performs like a high school cafeteria but looks more like a restaurant,” says Chris Youssef, an associate at Perkins Eastman (New York), “so mosaic tiles, glass, and wood laminates are the go-to materials that will give warmth, durability, and a higher-end look.”

Meanwhile, Belanger likes to introduce a lot of soft fabrics ingrained with stain-resistant properties and that fight wear and tear. Elkin adds visual interest to seating areas through texture, using rough and smooth surfaces to provide a backdrop while still maintaining cleanability and durability.

Kalloor turns to natural materials—in moderation—to finish a space. “While many natural materials may not be suitable for healthcare dining environments due to durability or sterility, when used selectively, they can add a lot of impact.” For instance, ceilings are a good place to incorporate the richness and beauty of wood, while natural stone tiles or glass mosaics can be integrated into the design in small doses and still deliver high design impact.

Another strategy, Kalloor says, is to use synthetic materials that mimic natural materials, colors, and patterns. “Examples include resilient flooring with a natural stone or wood look, engineered surface materials such as quartz or solid surface with visuals that imitate natural stone, and protective wall panels that are treated with a top layer that has an organic texture or wood panel appearance,” she says.

For flooring, Elkin recommends a balance of hard and soft flooring surfaces to create boundaries between different seating clusters and service areas. For example, hard-surface flooring, such as porcelain tiles, are typically installed in high-traffic circulation zones and at food service transition areas. Hard-surface flooring with minimal seams also minimizes crevices that may harbor dirt and germs. Poured composite floors like terrazzo o ffer can high-end visual appeal and come in a large variety of colors, visual textures, and custom patterns.

Up above An inherent piece of any dining space is all of the equipment required to operate, but one design trick is to shift attention elsewhere—specifically, up. “Designers use ceiling treatments as an opportunity to create interest and draw the eye up and away from the equipment in the serving areas and away from the cluster of chairs and tables in the dining room,” Kaminski says.

Kalloor adds that thoughtful ceiling design comes with even more benefits: “Ceiling treatments allow a large space to be visually compartmentalized into zones, they contribute the most to the acoustical quality within the space, and they tend be the only plane in the room that does not contain a lot of visual clutter.”

Belanger prefers gypsum ceilings in smaller dining and lounge spaces to create an upscale look, but in most applications specifies a smooth-finished acoustic ceiling tile. In place of standard 2-by-2-inch tiles, Kaminski recommends large-format, 48- by-48-inch options to create a more modern look. Barbara Bouza, managing director and principal at Gensler (Los Angeles), adds that high-performance mineral fiber and fiberglass materials will meet washability, noise level, anti-mold, and antibacterial requirements.

Let light in Lighting is another area where designers can boost the aesthetics of healthcare dining spaces. Whether it’s recessed down lights, decorative pendants, wall washers, rope lights, or indirect accent lights, there are plenty of options to help set the desired tone. For example, Kaminski says, “Mini-pendants over serving areas add a bit of fun, whereas clusters of drum fixtures in the dining area draw the eye upward to create a focal point above the sea of tables and chairs.”

Another trend Belanger sees is hospitals embracing LED lighting. “They understand that the initial cost is higher, but they save on the lifecycle cost almost immediately by reducing the frequency of maintenance calls to replace these fixtures,” she says. “I always like to give them direct/indirect LED fixtures with no more than 3500K for their general light over the food service and back-of-house areas,” she continues. Essentially, 3500K lighting provides a soft, warm light, whereas 4000K or higher takes on a more clinical/institutional look. With the softer light, a more restaurant-like environment is created.

“In the dining areas, I use recessed LED ‘high hats’ controlled by dimmers for different functions, ambience, and mood. LED decorative sconces and/or pendants make a world of difference in creating drama and appeal in a healthcare dining space. It also takes away the institutional look and makes the space feel like a restaurant,” she adds.

Of course, daylighting is also a desirable feature, driven by both newer energy code requirements and user preferences. “Allowing for daylight is key as this space is primarily used by hospital staff who are working in windowless spaces for much of the day,” Kalloor says. “If possible, the dining room should be designed along at least one exterior wall within the facility so that windows can stream light into the space.” Kalloor also recommends clerestory windows and skylights, in addition to conducting sunlight studies to optimize glazing placement and minimize glare.

Take out Moving forward, designers can anticipate that hospitals will continue prioritizing their dining areas, particularly given the elevated role that patient families are now playing in the healthcare process.

“With shortages in healthcare staff, specifically nursing, the family plays an important role in the caregiving experience and spends more time than ever in the hospital environment,” Bouza says. “These spaces offer visitors a welcome environment more conducive to working, having coffee, or even a small family meeting. A great dining space makes good business sense.”

Barbara Horwitz-Bennett is a contributing editor for Healthcare Design . She can be reached at [email protected] .

SIDEBAR : Back-of-house basics

Offering a take-away list of back-of-house best practices, food service consultant Richard Dieli of Dieli Murawka Howe (San Diego), suggests the following:

• Provide kitchen and ancillary spaces space for movement and storage of carts and mobile equipment in a safe and sanitary location.

• Provide more refrigeration than one thinks will be needed.

• Create a flow within the kitchen spaces that minimizes employee and mobile equipment cross traffic.

• Create a flow that allows easy access to refrigeration and storage for employees from all production areas.

• Install hand sinks in all production areas to promote food safety and reinforce a safe and sanitary work environment.

• Stay focused on utility costs. Utility and water usage are both deleterious to the environment and have a negative impact on the hospital’s bottom line.

• Optimize natural light. A pleasant work environment makes a healthier and happy employee, which in turn, will positively affect production.

Latest Operations and Facility Management

The HCD 10: UW Health, Outstanding Organization

The HCD 10: Tom Sorrell, Team MVP

The HCD 10: Stacey Johnson, Owner/Provider

The HCD 10: Deanne Avery, Facility Manager

Quality and standards of hospital food service; a critical analysis and suggestions for improvements

- September 2017

- Galle Medical Journal 22(2)

- Base Hospital Udugama

- University of Ruhuna

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Beraat Dener

- Hilal Betül Altintaş Başar

- Siti Hazimah Nor'hisham

- Nur Syazwani Mazlan

- Heng Chin Yee

- Mohd Shazali

- Amany M. Abdelhafez

- Lina Al Qurashi

- Reem Al Ziyadi

- Haneen Mograbi

- Vanessa A Theurer

- Andrew Fallon

- Mary Hannan-Jones

- J AM DIET ASSOC

- Patricia A. O'Hara

- Dan W. Harper

- Maris Kangas

- Nicole Lemire

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Step-by-Step Guide to Crafting a Business Plan for a Hospital

Get Full Bundle

| $169$99 | $59$39 | $39$29 | $15$9 | $25$15 | $15$9 | $15$9 | $15$9 | $19 |

Welcome to our blog post on how to write a business plan for a hospital! In today's rapidly growing healthcare industry, starting a hospital that focuses on providing quality, personalized medical services is a promising venture. According to recent statistics, the global healthcare market is projected to reach a value of $12.3 trillion by 2026, with a compound annual growth rate of 6.7%. This presents a great opportunity for entrepreneurs looking to make a difference in the lives of patients and contribute to the advancement of healthcare technology.

Before diving into the details of writing a business plan for your hospital, it's crucial to identify the market need and demand for this type of healthcare facility. Conducting a thorough market research will help you understand the current trends and assess the potential demand for specialized medical services. By analyzing competition and industry trends, you can gain insights into successful strategies and differentiate your hospital from others.

Developing a solid financial plan is essential for securing funding and partnerships. It involves outlining the hospital's projected revenue, expenses, and investment requirements. By preparing a comprehensive financial plan, you can demonstrate the viability and profitability of your venture to potential investors or lenders.

Defining the hospital's vision, mission, and values sets the foundation for its overall purpose. This helps in establishing a clear direction and guiding the decision-making process. Creating an organizational structure and identifying key roles ensures smooth operations and effective management of resources.

Formulating a comprehensive marketing strategy is crucial for attracting patients and building strong referral networks. It involves defining your target audience, identifying the best channels to reach them, and creating compelling messaging that highlights the unique benefits of your hospital.

Lastly, assessing the legal and regulatory requirements is vital to ensure compliance with healthcare laws and regulations. This includes obtaining the necessary licenses, permits, and certifications to operate your hospital.

By following these nine steps, you will be well-equipped to write a comprehensive business plan for your hospital. Stay tuned for our upcoming blog posts, where we will dive deeper into each step to provide you with practical insights and actionable tips.

Identify The Market Need And Demand

One of the first and most crucial steps in writing a business plan for a hospital is to identify the market need and demand for the services you intend to provide. Understanding the needs and preferences of potential patients is essential for developing a successful hospital that can effectively meet their healthcare requirements.

To gather this important information, conducting a thorough market research is key. This research should focus on the local healthcare landscape, demographics, and the specific services and medical treatments currently available in the area. By analyzing this data, you can identify any gaps or unmet needs in the market that your hospital can fulfill.

During the market research process, it is also important to evaluate the demographic trends and population dynamics in the area. Understanding factors such as age distribution, income levels, and prevalent medical conditions can help you tailor your services to the specific needs of the target population.

By thoroughly understanding the market need and demand for your hospital's services, you can develop a business plan that is aligned with the needs of the community you aim to serve. This will help ensure the success and sustainability of your hospital in the long run.

| Hospital Financial Model Get Template |

Conducting a Thorough Market Research

Conducting thorough market research is an essential step in developing a business plan for a hospital. This research will help you gain a clear understanding of the market need and demand, enabling you to make informed decisions about your hospital's offerings and target audience.

When conducting market research for a hospital, consider the following:

- Identify your target market: Determine the specific demographic and geographic characteristics of the population you intend to serve. This will help you tailor your services and marketing efforts accordingly.

- Analyze market trends: Stay updated with the latest trends in the healthcare industry. Identify emerging technologies, treatments, and practices that can distinguish your hospital from the competition.

- Assess competition: Study your competitors' offerings, pricing strategies, and marketing tactics. This will allow you to identify gaps in the market and position your hospital uniquely.

- Explore patient preferences: Understand what patients value when it comes to healthcare services. Conduct surveys or interviews to gather insights on their preferences, expectations, and experiences with existing healthcare providers.

- Evaluate regulatory factors: Familiarize yourself with the legal and regulatory requirements applicable to hospitals in your region. This includes licensing, documentation, and compliance with healthcare regulations.

Tips for Conducting Market Research for a Hospital

- Utilize online resources: Make use of online databases, industry reports, and market research tools to gather data on healthcare trends, market size, and consumer behavior.

- Engage with industry experts: Seek guidance from healthcare professionals, consultants, and experts who have in-depth knowledge of the industry. Their insights can provide valuable guidance during the research process.

- Consider qualitative and quantitative research: Combine qualitative methods like interviews and focus groups with quantitative techniques such as surveys and data analysis. This will provide a comprehensive understanding of your target market.

- Continuously update your research: Regularly review and update your market research to stay on top of industry developments and changing market dynamics. This will help you adapt your business plan accordingly.

By conducting thorough market research, you will be equipped with the necessary information to develop a business plan that aligns with the needs and expectations of your target market. This research will serve as a foundation for making informed decisions and ultimately contributing to the success of your hospital.

Analyze Competition And Industry Trends

One crucial step in developing a successful business plan for a hospital is to thoroughly analyze the competition and industry trends. This analysis provides valuable insights into the current market and helps identify opportunities and potential challenges that the hospital may face. Below are some important points to consider during this analysis:

Identify competitors: Begin by identifying existing hospitals and medical facilities that may be direct competitors. Research their offerings, facility size, capacity, and reputation within the community. Understanding their strengths and weaknesses will help you position your hospital effectively.

Study industry trends: Stay up-to-date with the latest trends in the healthcare industry. Identify key innovations, advancements in medical technology, and emerging treatments or services that could impact the hospital's success. This will help you adapt and stand out in a rapidly evolving industry.

Analyze market demand: Evaluate the current and projected demand for healthcare services in the target area. Consider factors such as population growth, demographic trends, and the prevalence of specific medical conditions. Understanding market demand will help in planning the hospital's service offerings and staffing requirements.

Evaluate competitive advantages: Identify what sets your hospital apart from the competition. This could include specialized services, unique treatment approaches, advanced technology, or a focus on personalized patient care. Highlighting these competitive advantages in your business plan will attract potential patients and investors.

- Use online resources, industry publications, and professional networks to gather information on competitors and industry trends.

- Engage with healthcare professionals, potential patients, and community members to gain insights into their expectations and preferences.

- Consider conducting surveys or focus groups to gather more specific feedback and opinions on the market and competition.

- Regularly revisit and update the analysis of competition and industry trends to stay ahead of the curve and maintain a competitive edge.

Develop A Solid Financial Plan

A solid financial plan is crucial for the success of any business, including a hospital. It provides a roadmap for achieving financial stability and sustainability. Here are some important steps to take when developing a solid financial plan for a hospital:

- Estimate costs and revenue: Start by estimating the costs involved in setting up and running the hospital. This includes expenses such as equipment, facility construction or lease, staff salaries, operational costs, and marketing expenses. Additionally, analyze the expected revenue sources, such as patient fees, insurance reimbursements, and potential partnerships or collaborations.

- Financial projections: Utilize the market research and competition analysis to make informed financial projections. This will include forecasting the number of patients, expected reimbursement rates, and expected revenue growth over a specific period of time. Be sure to consider factors such as seasonality, demand fluctuations, and potential economic changes.

- Budget allocation: Once you have estimated costs and revenue and made financial projections, prioritize how you will allocate your budget. Consider allocating resources for essential needs such as medical equipment, technology, employee training, marketing, and community outreach programs. Create a detailed budget plan that includes both recurrent and capital expenses.

Tips for developing a solid financial plan:

- Consult with financial advisors or experts in the healthcare industry to ensure accuracy and validity of financial projections.

- Consider different funding sources, such as private investors, loans, grants, or public funding programs specifically targeting healthcare projects.

- Account for contingency funds to handle unexpected expenses or emergencies.

- Regularly revisit and update your financial plan to reflect changing market conditions, trends, and regulatory requirements.

Developing a solid financial plan requires a thorough understanding of the healthcare industry, market dynamics, and financial management principles. It's essential to invest time and effort into this step to lay a strong foundation for the hospital's financial success.

Secure Funding and Partnerships

Once you have developed a solid financial plan, the next crucial step in starting a hospital is securing funding and building partnerships. This stage is vitally important as it determines the financial stability and sustainability of your hospital.

1. Identify potential funding sources: Start by exploring various funding options available to you. This may include approaching investors, applying for grants and loans, or seeking partnerships with other organizations. Assess the pros and cons of each option to determine the best fit for your hospital.

- Prepare a comprehensive business plan and financial projections to convince potential investors or lenders of your hospital's viability.

- Consider partnering with organizations that share a similar mission and vision to leverage their expertise, resources, and infrastructure.

2. Craft a compelling funding proposal: Develop a persuasive funding proposal that clearly outlines your hospital's mission, goals, financial needs, and potential benefits for investors or partners. Emphasize the unique value proposition and the impact your hospital can make in the healthcare industry.

3. Build strategic partnerships: Collaborate with other healthcare organizations, research institutions, or technology companies to access resources, expertise, and specialized services. Look for complementary strengths that align with your hospital's vision and objectives.

- Network within the healthcare industry to build connections and explore potential partnership opportunities.

- Consider joining professional associations or attending industry conferences to connect with potential partners.

4. Establish trust and credibility: Demonstrate your hospital's potential by showcasing the qualifications and expertise of your team, highlighting successful case studies, or sharing testimonials from satisfied patients or partners. Establishing credibility is crucial to attract investments and create fruitful partnerships.

5. Think beyond financial support: While securing funding is a primary concern, also consider the value that partners can bring beyond monetary contributions. Look for partners who can offer strategic guidance, business acumen, or access to a broader network of healthcare professionals and resources.

6. Seek legal and financial advice: Consult legal and financial experts to ensure that your funding and partnership agreements are robust and legally sound. They can assist in negotiating favorable terms and protecting your hospital's interests.

By carefully navigating the funding and partnership landscape, you can secure the necessary resources and allies to propel your hospital towards success. Remember, building strong partnerships is not just about financial support but also finding collaborative opportunities that align with your hospital's vision and values.

Define The Hospital's Vision, Mission, And Values

Defining the vision, mission, and values of your hospital is crucial for establishing its identity and guiding its direction. These elements serve as the foundation for your organization and shape its culture, goals, and strategies.

When crafting the vision statement , consider the long-term aspirations and purpose of your hospital. It should succinctly describe the desired future state and the impact you aim to make in the community. This statement should inspire and motivate both your staff and patients.

The mission statement clarifies the fundamental purpose and reason for the existence of your hospital. It outlines the primary services you will provide and the target population you aim to serve. This statement should be concise and clearly communicate the value you intend to deliver.

The values of your hospital outline the guiding principles and beliefs that underpin your organization's culture and conduct. These principles should align with the overall mission and vision. They provide a framework for decision-making, as well as help ensure consistency in providing patient care.

Tips for Defining Your Hospital's Vision, Mission, and Values:

- Involve key stakeholders, including staff, patients, and community members, in the process to gain diverse perspectives and foster a sense of ownership.

- Keep your statements concise and easily understandable to ensure clarity and coherence.

- Ensure that your vision, mission, and values are in line with the market need identified and the unique value proposition of your hospital.

- Regularly revisit and refine your vision, mission, and values to adapt to changes in the healthcare landscape and the evolving needs of your patients.

By clearly defining your hospital's vision, mission, and values, you establish a strong foundation that guides decision-making, fosters a sense of purpose among your staff, and communicates the unique value your hospital brings to the community.

Outline The Organizational Structure And Key Roles

In order to effectively run a hospital, it is crucial to clearly outline the organizational structure and identify the key roles within the healthcare facility. This will help ensure smooth operations, effective communication, and proper allocation of responsibilities. Here are some important steps to consider when outlining the organizational structure and key roles:

- Identify the leadership positions: Start by identifying the key leadership positions that will oversee the hospital's operations. This typically includes roles such as Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Chief Medical Officer (CMO), and Chief Nursing Officer (CNO).

- Define the departments: Next, outline the various departments within the hospital, such as administration, nursing, finance, human resources, and medical services. Each department should have a designated leader responsible for managing day-to-day operations and ensuring departmental goals are met.

- Establish reporting lines: Clearly define the reporting lines within the organizational structure to ensure efficient communication and decision-making processes. Indicate who reports to whom, and establish a hierarchical structure that promotes accountability and clarity.

- Identify key roles: Determine the key roles within each department and specify the responsibilities and qualifications for each position. This may include physicians, nurses, therapists, administrative staff, and other healthcare professionals required to deliver quality care.

- Promote teamwork and collaboration: Emphasize the importance of teamwork and collaboration among different departments and roles within the hospital. Encourage regular meetings, cross-functional projects, and open communication channels to foster a culture of cooperation and interdisciplinary care.

- Delegate authority: Delegate authority and empower individuals within their respective roles to make decisions and take ownership of their responsibilities. This encourages autonomy and accountability, and enables efficient problem-solving and decision-making processes.

- Consider developing an organizational chart to visually represent the hierarchical structure and reporting lines within the hospital.

- Regularly review and update the organizational structure to ensure it aligns with the evolving needs of the hospital and changing healthcare landscape.

- Communicate the organizational structure and key roles to all employees to ensure clarity and understanding of their responsibilities and reporting lines.

By carefully outlining the organizational structure and key roles, a hospital can establish a strong foundation for effective management, collaboration, and seamless delivery of quality healthcare services.

Formulate A Comprehensive Marketing Strategy

A comprehensive marketing strategy is essential for successfully promoting and positioning your hospital in the healthcare industry. It involves identifying your target audience, creating effective messaging, choosing the right marketing channels, and continuously evaluating and adapting your strategies to ensure maximum reach and impact.

When formulating your marketing strategy, keep the following key aspects in mind:

Tips for Formulating A Comprehensive Marketing Strategy:

- Identify your target audience: Determine the demographics and characteristics of the patients you want to attract. This enables you to tailor your marketing efforts towards their specific needs and preferences.

- Create compelling messaging: Develop a clear and persuasive message that highlights the unique value proposition of your hospital. Emphasize the personalized care, cutting-edge technology, and evidence-based treatment you offer.

- Choose the right marketing channels: Utilize a mix of traditional and digital marketing channels to reach your target audience effectively. Consider strategies such as search engine optimization (SEO), social media marketing, email campaigns, and referral programs.

- Build strong relationships: Cultivate relationships with referring physicians, healthcare professionals, and community organizations. Establish partnerships to increase referrals and enhance your reputation within the healthcare community.

- Monitor and evaluate: Regularly measure the effectiveness of your marketing efforts by tracking key performance indicators (KPIs). Analyze data, gather feedback, and adapt your strategies accordingly to ensure maximum impact and return on investment.

A comprehensive marketing strategy plays a vital role in attracting patients, establishing your hospital's brand, and maintaining a competitive edge in the healthcare industry. By understanding your target audience, crafting compelling messaging, choosing the right channels, and continuously evaluating your strategies, you can position your hospital as a trusted provider of high-quality and personalized medical services.

Assess Legal And Regulatory Requirements

Ensuring compliance with legal and regulatory requirements is crucial when setting up a hospital. This step involves researching, understanding, and meeting the various laws and regulations that govern the healthcare industry.

- Obtain necessary licenses and permits: Familiarize yourself with the licensing requirements specific to hospitals in your jurisdiction. Determine the necessary permits and certifications required to operate legally.

- Comply with healthcare regulations: Understand and comply with regulations related to patient privacy, data protection, health and safety standards, and medical waste management. Implement appropriate policies and protocols to ensure compliance.

- Stay updated with healthcare laws: Keep abreast of any changes or updates in healthcare laws and regulations that may have an impact on your hospital. This includes staying informed about reimbursement policies, billing regulations, and insurance requirements.

- Secure professional licenses and certifications: Ensure all healthcare professionals working at the hospital possess valid licenses and certifications. Perform necessary background checks and verification procedures to maintain quality and patient safety standards.

- Implement proper documentation and record-keeping practices: Establish systems for accurate and organized documentation to comply with medical record-keeping requirements. Adhere to guidelines for the storage, retention, and disposal of medical records.

- Seek legal counsel: Consult with healthcare attorneys or legal experts with experience in the healthcare industry to navigate the complex legal landscape.

- Stay updated with changes: Regularly review and update your knowledge on relevant laws and regulations to ensure ongoing compliance.

- Establish a compliance team: Assign responsibilities to a dedicated compliance team or officer to monitor and enforce adherence to legal and regulatory requirements.

In conclusion, developing a business plan for a hospital requires careful consideration and thorough research. By following the nine steps outlined in this checklist, you can ensure that your hospital is well-prepared to meet the market demand, provide high-quality care, and comply with legal and regulatory requirements. By focusing on personalized medical services, leveraging cutting-edge technology, and adopting a multidisciplinary approach to treatment, your hospital can strive towards providing the best possible outcomes for patients.

Related Blogs

- 7 Mistakes to Avoid When Starting a Hospital in the US?

- What Are The Top 9 Business Benefits Of Starting A Hospital Business?

- What Are Nine Methods To Effectively Brand A Hospital Business?

- Hospital Business Idea Description in 5 W’s and 1 H Format

- Own a Hospital Business: The Ultimate Acquisition Checklist!

- How To Name A Hospital Business?

- Hospital Owner Earnings: A Comprehensive Analysis

- How to Open a Hospital: Steps to Navigate Regulatory Requirements

- 7 Essential KPIs for Hospital Business Management

- How to Analyze Hospital Operating Expenses Efficiently

- What Are The Top Nine Pain Points Of Running A Hospital Business?

- Revolutionizing Healthcare: Unleash Success with Our Hospital Pitch Deck! Act Now.

- How to Improve Hospital Financial Performance: A Step-by-Step Guide

- What Are Nine Strategies To Effectively Promote And Advertise A Hospital Business?

- The Complete Guide To Hospital Business Financing And Raising Capital

- Strategies To Increase Your Hospital Sales & Profitability

- How To Sell Hospital Business in 9 Steps: Checklist

- Key Financial Aspects To Plan For When Starting A Hospital

- What Are The Key Factors For Success In A Hospital Business?

- Hospital Business: Evaluating its Worth

| Expert-built startup financial model templates |

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Please note, comments must be approved before they are published

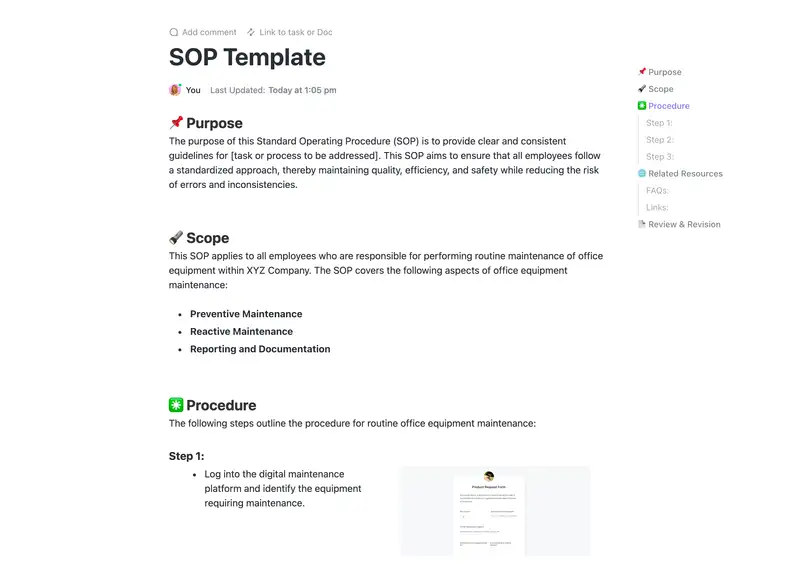

Hospital Canteen SOP Template

- Great for beginners

- Ready-to-use, fully customizable Doc

- Get started in seconds

Hospital canteens play a vital role in providing nutritious meals to patients, staff, and visitors. But ensuring food safety and maintaining high standards can be a challenge. That's where ClickUp's Hospital Canteen SOP Template comes in!

With this template, you can streamline your Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for the hospital canteen, ensuring that your team:

- Follows strict hygiene and safety protocols to prevent foodborne illnesses

- Maintains proper food storage, handling, and preparation techniques

- Adheres to dietary restrictions and special meal requirements

- Monitors and maintains equipment and facilities for optimal performance

Whether you're managing a small hospital canteen or a large-scale operation, this template will help you maintain the highest standards of food safety and quality. Get started today and ensure a healthy dining experience for all!

Benefits of Hospital Canteen SOP Template

When it comes to running a hospital canteen smoothly and efficiently, having a standard operating procedure (SOP) template is a game-changer. Here are some of the benefits of using the Hospital Canteen SOP Template:

- Ensures consistent food quality and safety standards

- Streamlines daily operations and reduces errors

- Provides clear guidelines for staff on food preparation, handling, and storage

- Improves customer satisfaction by maintaining high service standards

- Helps with training new employees and maintaining a well-trained team

- Enhances overall efficiency and productivity in the canteen

Main Elements of Hospital Canteen SOP Template

ClickUp's Hospital Canteen SOP Template is designed to help you create and maintain standard operating procedures for your hospital canteen operations.

This Doc template contains all the necessary sections and content to guide you in creating a comprehensive SOP. It also includes ClickUp features such as:

- Custom Statuses: Create tasks with custom statuses to track the progress of each step in your SOP, such as "To Do," "In Progress," and "Completed."

- Custom Fields: Categorize and add attributes to your tasks to provide additional information and manage your canteen operations effectively.

- Custom Views: Utilize different views, such as List, Board, or Calendar, to visualize and manage your SOP tasks in a way that suits your workflow.

- Project Management: Enhance your SOP creation process with ClickUp's features like Tags, Dependencies, Priorities, and Integrations with other tools.

How to Use SOP for Hospital Canteen

Running a hospital canteen requires careful planning and adherence to standard operating procedures (SOPs). Here are four steps to effectively use the Hospital Canteen SOP Template in ClickUp:

1. Familiarize yourself with the template

Before diving into the SOP template, take some time to familiarize yourself with its structure and content. Understand the purpose and scope of the SOP, as well as the specific guidelines and procedures outlined within it. This will help you navigate the template more efficiently and ensure that you're following the correct protocols.

Use the Docs feature in ClickUp to access and read through the Hospital Canteen SOP Template.

2. Customize the template to your hospital's needs

Every hospital has unique requirements and regulations when it comes to running a canteen. Take the time to tailor the SOP template to fit your hospital's specific needs. This may involve adding or removing certain sections, updating procedures to align with your hospital's policies, or incorporating any additional guidelines or regulations that are relevant to your canteen operations.

Utilize the custom fields feature in ClickUp to make necessary modifications and personalize the Hospital Canteen SOP Template.

3. Train your canteen staff

Once you have finalized the customized SOP template, it's crucial to train your canteen staff on its contents and expectations. Schedule a training session to go over each section of the SOP, explaining the procedures, guidelines, and best practices outlined in the document. Ensure that your staff understands their roles and responsibilities, as well as the importance of adhering to the SOP for maintaining a safe and efficient canteen environment.

Create tasks in ClickUp to assign training sessions and track the progress of each staff member.

4. Regularly review and update the SOP

SOPs are not set in stone and should be reviewed and updated periodically to reflect any changes in regulations, hospital policies, or best practices. Schedule regular reviews of the Hospital Canteen SOP to ensure it remains up-to-date and relevant. Encourage feedback from your canteen staff and consider their suggestions for improvement. By continuously evaluating and updating the SOP, you can ensure that your canteen operations stay in compliance and consistently meet the highest standards.

Set recurring tasks in ClickUp to remind yourself to review and update the Hospital Canteen SOP on a regular basis.

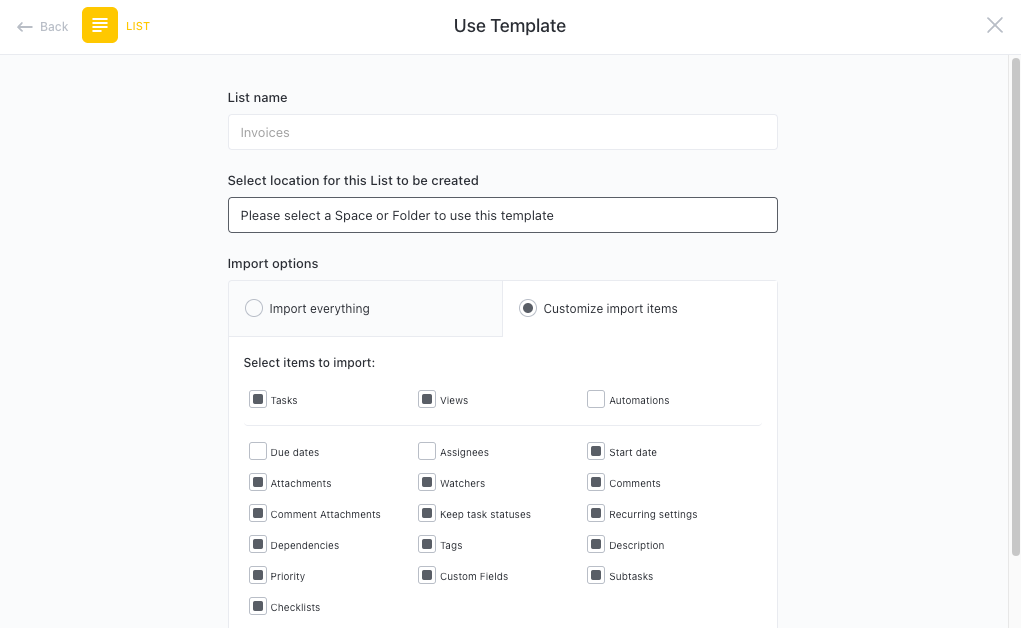

Get Started with ClickUp's Hospital Canteen SOP Template

Hospital canteen managers can use this Hospital Canteen SOP Template to streamline operations and ensure a smooth running canteen for staff and patients.

First, hit “Add Template” to sign up for ClickUp and add the template to your Workspace. Make sure you designate which Space or location in your Workspace you’d like this template applied.

Next, invite relevant members or guests to your Workspace to start collaborating.

Now you can take advantage of the full potential of this template to manage your canteen:

- Create Docs to outline the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for each area of the canteen, such as food preparation, cleaning, and cashier duties

- Assign tasks to team members to ensure everyone is aware of their responsibilities

- Utilize Checklists for daily opening and closing procedures to maintain cleanliness and hygiene

- Attach relevant documents such as menus, ingredient lists, and special dietary requirements for easy reference

- Set up recurring tasks to schedule regular equipment maintenance and cleaning

- Use the Gantt chart view to create a timeline for menu planning and ordering supplies

- Collaborate using Comments for seamless communication and feedback on menu ideas and customer preferences

Related Templates

- Applied Energy Management SOP Template

- Safety in Pharmaceutical Industry SOP Template

- Petroleum Engineering SOP Template

- Safety in Factory SOP Template

- Employee Onboarding SOP Template

Template details

Free forever with 100mb storage.

Free training & 24-hours support

Serious about security & privacy

Highest levels of uptime the last 12 months

- Product Roadmap

- Affiliate & Referrals

- On-Demand Demo

- Integrations

- Consultants

- Gantt Chart

- Native Time Tracking

- Automations

- Kanban Board

- vs Airtable

- vs Basecamp

- vs MS Project

- vs Smartsheet

- Software Team Hub

- PM Software Guide

Serving our Healthcare Providers

We service America’s hospital systems, doctor offices, and healthcare facilities. For these teams and visitors, taking care of the patient is their top priority. Often, they keep going and forget to grab a bite to eat. By partnering with us, we’ll help make it easy for these caregivers to take a break and refuel, so they can get back to what they need to do.

From open retail markets for the break room to markets with access-controlled doors for the lobby, our technology provides flexibility for a variety of spaces.

Our snack, drink, fresh food, and coffee vending machines offer the options you need for your break room or lobby.

It's Easy to Get Started

Let us know you're ready to provide the best break possible by completing our online form .

We’ll meet with you to review your service needs, space requirements, and develop a plan for you.

We’ll agree on what happens next and when.

Guangdong Grace Kitchen Equipment Co., Ltd

What are the main points of the design plan of the hospital canteen kitchen?

Quick Links

- Applications

- Western Cooking Range

- Bakery Equipment

- Refrigeration Equipment

- Snacks Food Equipment

Better Touch Better Business

For more products related question ,Welcome to inquiry us .

Follow us at

版权所有 © 2019 格雷斯厨房设备有限公司 | 版权所有

Hello, please leave your name and email here before chat online so that we won't miss your message and contact you smoothly.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Availability of Healthy Food and Beverages in Hospital Outlets and Interventions in the UK and USA to Improve the Hospital Food Environment: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review

Associated data.

Not applicable.

The aims of this systematic review are to determine the availability of healthy food and beverages in hospitals and identify interventions that positively influence the hospital food environment, thereby improving the dietary intake of employees and visitors. Embase, Medline, APA PsycInfo, Scopus, Google Scholar and Google were used to identify publications. Publications relating to the wider hospital food environment in the UK and USA were considered eligible, while those regarding food available to in-patients were excluded. Eligible publications ( n = 40) were explored using a narrative synthesis. Risk of bias and research quality were assessed using the Quality Criteria Checklist for Primary Research. Although limited by the heterogeneity of study designs, this review concludes that the overall quality of hospital food environments varies. Educational, labelling, financial and choice architecture interventions were shown to improve the hospital food environment and/or dietary intake of consumers. Implementing pre-existing initiatives improved food environments, but multi-component interventions had some undesirable effects, such as reduced fruit and vegetable intake.

1. Introduction

Overweight and obesity are extremely prevalent across the UK and USA. In 2018, it was estimated that 67% of men and 60% of women in the UK had overweight or obesity [ 1 ], along with 71.6% of American adults in 2015/2016 [ 2 ]. A high body mass index (BMI) is linked to a range of non-communicable diseases, such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease [ 3 ], which has led to a significant number of hospital admissions associated with weight-related disorders. Between 2014 and 2015, it was estimated that the economic cost of overweight and obesity-related health complications to the National Health Service (NHS) was GBP 6.1 billion [ 4 ], while the healthcare cost of obesity in America was approximately USD 149.4 billion [ 5 ].

In addition to the high prevalence of obesity and overweight in the general population, healthcare employees demonstrate similar weight-management issues. One study carried out by Kyle et al. (2017) used data from the 2008–2012 Health Survey for England and found that 25.1% of the nurses surveyed had a BMI of 30 kg/m 2 or higher, classifying them as ‘obese’. Furthermore, 32% of unregistered care workers, 26% of non-health-related NHS employees and 12% of other healthcare professionals also had a BMI of 30 kg/m 2 or higher. These values are similar among American hospital staff members, with 27% of American nurses estimated to be obese [ 6 ].

A key cause of obesity is eating an excess of unhealthy foods. In the UK, the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities advises infrequent consumption of foods high in fat, salt and sugar [ 7 ]. American guidelines reflect the same general recommendations; according to the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, a healthy diet should involve the restriction of saturated and trans fats, added sugars and salt [ 8 ]. Therefore, unhealthy foods can be defined as products that are high in these substances.

The range of healthy or unhealthy food and beverages available, food marketing techniques and the cost of food items in a specified setting can be referred to as the food environment [ 9 ]; this has a significant impact on the nutritional quality of food consumed by the general public. Studies have shown that there is an association between easier access to fast food and greater BMI and odds of obesity [ 10 ], suggesting that the food environment has a strong influence on weight status.