- HISTORY & CULTURE

Here's the history of basketball—from peach baskets in Springfield to global phenomenon

The first game used baskets as hoops and turned into a brawl. Soon after, basketball evolved into a pillar of American sports.

The nets used by athletes to dunk the ball and score points in the beloved game of basketball evolved from peaches, or rather the baskets used to collect peaches.

That’s what a young athletic director ultimately used on a cold day back in 1891 for a new game he created to keep his students engaged.

James Naismith was a 31-year old graduate student teaching physical education at the International YMCA Training School , now known as Springfield College, in Springfield, Massachusetts when students were forced to stay indoors for days due to a New England storm. The usual winter athletic activities were marching, calisthenics, and apparatus work but they weren’t nearly as thrilling as football or lacrosse which were played during the warmer seasons.

Naismith wanted to create a game that would be simple to understand but complex enough to be interesting. The game had to be playable indoors, and it had to accommodate several players at once. The game also needed to provide plenty of exercise for the students, yet without the physicality of football, soccer, or rugby since those would threaten more severe injuries if played in a confined space. ( See 100 years of football in pictures. )

Naismith approached the school janitor, hoping he could find two square boxes to use for goals. When the janitor came back from his search, he had two peach baskets instead. Naismith nailed the peach baskets to the lower rail of the gymnasium balcony, one on each side. The height of that lower balcony rail happened to be 10 feet. The students would play on teams to try to get the ball into their team’s basket. A person was stationed at each end of the balcony to retrieve the ball from the basket and put it back into play.

The first game ever played between students was a complete brawl.

“The boys began tackling, kicking and punching in the crunches, they ended up in a free for all in the middle of the gym floor before I could pull them apart,” Naismith said during a January 1939 radio program on WOR in New York City called We the People, his only known recording. “One boy was knocked out. Several of them had black eyes and one had a dislocated shoulder.” Naismith said. “After that first match, I was afraid they'd kill each other, but they kept nagging me to let them play again so I made up some more rules.”

For Hungry Minds

The humble beginnings of the only professional sport to originate in the United States laid the foundation for today’s multi-billion-dollar business. The current National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) March Madness college basketball tournament includes the best 68 of more than 1,000 college teams, stadiums that seat tens of thousands of spectators and lucrative television contracts.

Original rules of the game

Naismith didn’t create all of the rules at once, but continued to modify them into what are now known as the original 13 rules . Some are still part of the modern game today. Naismith’s original rules of the game sold at auction in 2010 for $4.3 million.

In the original rules: The ball could be thrown in any direction with one or both hands, never a fist. A player could not run with the ball but had to throw it from the spot where it was caught. Players were not allowed to push, trip or strike their opponents. The first infringement was considered a foul. A second foul would disqualify a player until the next goal was made. But if there was evidence that a player intended to injure an opponent, the player would be disqualified for the whole game.

Umpires served as judges for the game, made note of fouls and had the power to disqualify players. They decided when the ball was in bounds, to which side it belonged, and managed the time. Umpires decided when a goal had been made and kept track of the goals.

If a team made three consecutive fouls, the opposing team would be allowed a goal.

A goal was made when the ball was thrown or batted from the grounds into the basket and stayed there. If the ball rested on the edges, and the opponent moved the basket, it would count as a goal. When the ball went out of bounds, it was thrown into the field of play by the person first touching it. The person throwing the ball was allowed five seconds; if he held it longer, the ball would go to the opponent. In case of a dispute, an umpire would throw the ball straight into the field. If any side persisted in delaying the game, the umpire would call a foul on that side.

The length of a game was two 15-minute halves, with five minutes' rest between. The team making the most goals within the allotted time was declared the winner. If a game was tied, it could be continued until another goal was made.

First public games

The first public game of basketball was played in a YMCA gymnasium and was recorded by the Springfield Republican on March 12th, 1892. The instructors played against the students. Around 200 spectators attended to discover this new sport they had never heard of or seen before. In the story published by the Republican, the teachers were credited with “agility” but the student’s “science” is what led them to defeat the teachers 5-1.

You May Also Like

Your daily life is probably shaped by these 12 people—do you know their names?

Meet the inventor of the Bloodmobile

Antifreeze in ice cream? These unusual ingredients are found in everyday products

Within weeks the sport’s popularity grew rapidly. Students attending other schools introduced the game at their own YMCAs. The original rules were printed in a college magazine, which was mailed to YMCAs across the country. With the colleges’ well-represented international student body the sport also was introduced to many foreign nations. High schools began to introduce the new game, and by 1905, basketball was officially recognized as a permanent winter sport.

The first intercollegiate basketball game between two schools is disputed, according to the NCAA. In 1893, two school newspaper articles were published chronicling separate recordings of collegiate basketball games facing an opposing college team.

In 1892, less than a year after Naismith created the sport, Smith College gymnastics instructor Senda Berenson, introduced the game to women’s athletics. The first recorded intercollegiate game between women took place between Stanford University and University of California at Berkeley in 1896.

With the sport’s growth in popularity, it gained notice from the International Olympic Committee and was introduced at the 1904 Olympic Games in St. Louis as a demonstration event. It wasn’t until 1936 that basketball was recognized as a medal event. Women’s basketball wasn’t included as an Olympic medal event until the 1976 Montreal games. ( Wheelchair basketball in Cambodia changed these women's lives. )

As the sport continued its rapid spread, professional leagues began to form across the United States. Basketball fans cheered on their new hometown teams. The first professional league was the National Basketball League (NBL) formed in 1898, comprised of six teams in the northeast. The league only lasted about five years. After it dissolved in 1904, the league would be reintroduced 33 years later in 1937 with an entirely new support system, with Goodyear, Firestone, and General Electric corporations as the league owners, and 13 teams.

While professional sports leagues gained nationwide attention, college basketball was also a major fixture. The first NCAA tournament, which included eight teams, was held in 1939 at Northwestern University. The first collegiate basketball national champion was the University of Oregon. The team defeated Ohio State University.

Like most of the United States in the early to mid 1900s, basketball was segregated. The sport wouldn’t be integrated until 1950 when Chuck Cooper was drafted by the Boston Celtics. Prior to Cooper being drafted there were groups of black teams across the country, commonly known as “the black fives”, which referred to the five starting players on a basketball team. All-black teams were often referred to as colored quints or Negro cagers. The teams flourished in New York City, Washington, D.C., Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, and in other cities with substantial African American populations. They were amateur, semi-professional, and professional.

Of the more than 1,000 collegiate basketball teams across all divisions of the NCAA, 68 teams play in the annual March Madness tournament. The best college teams from each conference around the country compete for a place in the Sweet 16, Elite Eight, Final Four and, ultimately, the national championship. Though basketball might not be played the same way as it was when Naismith invented it—peach baskets have been replaced with nets, metal hoops and plexiglass blackboards—its evolution proves that the game has transcended a century.

Related Topics

- WINTER SPORTS

This ancient society helped build the modern world.

What's inside Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks?

Pickleball is everywhere. Here's why the fast-growing sport is good for your health

Thomas Edison didn’t invent the light bulb—but here’s what he did do

The Viking origins of your Bluetooth devices

- Paid Content

- Environment

- Photography

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Recent changes

- Random page

- View source

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Create account

How did basketball develop

Unlike other major sports, the origins of basketball are not very ancient and most historians agree that the sport was founded in 1891 by James Naismith. However, its development was at times complex and was able to thrive as other major sports enthralled audiences in the United States and later the world.

Early History

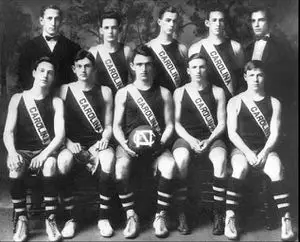

With the invention of basketball in 1891, a new game that was very different than its contemporaries formed. The specific founding of basketball are precisely known because James Naismith (Figure 1), who worked as a instructor at a YMCA, was given the task of creating an indoor game. This was seen as a way to keep children out of trouble and entertained during the winter months. Initially, Naismith tried to create versions of American football or soccer as indoor sports. However, all of these proved too violent, as they also caused damage to property in confined spaces. Within two weeks of Naismith's task, the first basketball rules were created. Although done in haste, six of the original thirteen rules Naismith created are still with us. This includes not using your fist, shoulder, and not being allowed to run with the ball. The first "nets" were, in fact, two peach baskets attached at either end of the court.

The first ball was a soccer ball, with the first court being in Springfield College's YMCA in Springfield Massachusetts. The first baskets were 10 feet high, something that has been retained, but the ball could not go through the basket and after each score the ball had to be retrieved. The name "basket ball" developed when one of the children playing the new game referred to the game as such after seeing it. [1]

Very quickly, in January 20, 1892, the first official game, with 18 players, using Naismith's rules was played, with the final score 1-0. The first games were simply about keeping the ball away from the opposing team and it took some time for the concept of offense to develop. By 1898, a professional league was already being founded, called the National Basketball League, although it did not prove to have long-term success, as it was abandoned within 6 years. In the next decade during the 1900s, the basketball net developed to be more like the modern one, with a net and backboard developed. The ball was replaced with a new type that is of more similar dimensions to those used today. [2]

Why Did Basketball Thrive?

As basketball was founded by the YMCA, which is a Christian institution, the spread of the game coincided also with missionary and medical activities undertaken. Soon, the YMCA used basketball as part of its work abroad and within North America. This helped to popularize not only the YMCA but also the game itself. [3]

Similar to American football, colleges became key places for spreading basketball (Figure 2). With long winter months in many parts of the United States, people increasingly sought recreation during this time. Colleges developed indoor gymnasiums that soon became taken over with basketball courts, spreading the popularity of the game. This soon led to the organization of college basketball teams. New rules, including dribbling and concept of fouling out of games, developed. By the end of the 1910s, most of the rules that are with us today had developed in the college game. However, what did not develop were professional teams, as the early professional teams had to fold. [4]

Similar to baseball, however, it was war and the rapidly changing economy that developed that helped to shape how basketball spread. In the 1910s and going into World War I, the spread of soldiers to different parts of the country and world brought basketball to new places. In fact, the first official international games occurred as a result of World War I, as the allies created teams that competed in the so-called Inter-Allied Games. Domestically, basketball continued to spread in colleges in the 1920s and 1930s, even as the professional leagues had still not developed. Disorganization and the Great Depression likely prevented basketball from becoming professional during this time. By 1938 and 1939, the development of the National Invitational Tournament (NIT) and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) tournament developed, which are still present. The University of Oregon was the NCAA's first winner with a score of 46-33 against Ohio State. [5]

In 1937 and 1946, the National Basketball League (NBL) and Basketball Association of America (BAA) were created respectively. While the NBL eventually had to fold, some of its teams and the BAA merged into what became the National Basketball Association (NBA) in 1949. [6]

The Modern Era

Like many other sports, the combination of superstars, radio, and then television helped to spread the popularity of the game and make the game modern with new stadiums purposely build for basketball. The first true superstar was George Mikan, who was six feet and ten inches tall. His height forced changes to the game, mainly the 3-second lane being widened as his large height made the sport less competitive for opposing teams as he simply dominated underneath the basket with his height. By 1950, the basketball color barrier, which was far less formidable than that in baseball, was broken by Chuck Cooper who played for the Boston Celtics. By the late 1940s, slam dunks were becoming part of the game. [7]

The college game continued to thrive and it was the college game that continued to be ahead of the pros, with TV rights signed in the 1950s that helped to increase the games popularity. Meanwhile, the professional leagues popularity stalled, as rules regulating time wasting and fouling were not developed in the NBA. This led to the game becoming much slower and less interesting for viewers. In 1954, Danny Biasone introduced the 24 second shot clock and foul limits that then revitalized the professional game. It now became a much faster sport, with higher scoring, where by 1958 average scoring topped the 100 mark, gaining more popularity. Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russel joining the professional game by the late 1950s helped to make the professional game popular. While Bill Russel helped found the Celtic dynasty of 1957-1969, Chamberlain is best remembered for his high scoring and being the first player to score 100 points in a game. Chamberlain's dominance led to the center lane being widened. The 1950s and 1960s were the first decades when television broadcasted games.

In 1967, the American Basketball Association (ABA) emerged as a threat to the NBA. It did have some major stars to its name because it began to actively recruit in college campuses. The NBA, meanwhile, developed its iconic logo that debuted in 1971. The ABA and NBA competed throughout the early 1970s. This was a period where the NBA grew from 9 to 18 teams, mostly because of the competition with the ABA forced the NBA to aggressively expand. By 1976, however, the ABA and NBA merged. Another period of declining interest started in the late 1970s. This time the introduction of the three-point shot (in 1979) and arrival of major stars that became international phenomena revitalized the game. The first two were Larry Bird and Magic Johnson, who famously battled in the 1984 finals. With the arrival of Michael Jordan in 1984, the game's popularity surged to new heights and helped develop what many think of basketball today, as his style of play and commercialization of many aspects of the game became major draws for investors and fans alike. [8]

Global Phenomenon

Although early in its history basketball had already spread globally, with the Olympics adopting basketball by 1936, the modern era's popularity is attributed to both TV and players. Stars such as Michael Jordan were at times more popular than national heroes in foreign countries. Slow motion replay, no doubt, helped those worldwide watch how Michael Jordan would effortlessly glide or slam dunk in a seemingly impossible move. The popularity of Michael Jordan awakened many firms in marketing basketball and the NBA promoting itself. The realization of how marketable Jordan was and the introduction of professional athletes to the Olympics in 1992 (so-called Dream Team) was part of the NBA strategy to expand its brand. This spread basketball's popularity, where it rivals football (or soccer) in many places. By 2014, the NBA itself had become international, with more than 100 players being foreign born. In 1992, only 23 players were foreign born. [9] This shows that the history of basketball will be one shaped by many nationalities despite the sports distinct American heritage.

Related DailyHistory.org Articles

- How did hunting become a symbol of the aristocracy/royalty

- How did the marathon emerge?

- How did the modern tennis emerge?

- Who integrated the NBA?

- How did the game of golf emerge?

- Did Theodore Roosevelt really save Football?

- ↑ For information on the invention of the game by Naismith, see: Rains, R. (2011) OCLC: 829926672. James naismith: the man who invented basketball. Place of publication not identified, Temple University Press.

- ↑ For more on the early games of basketball, see: Bjarkman, P.C. (2000) The biographical history of basketball: more than 500 portraits of the most significant on-and off-court personalities of the game’s past and present. Lincolnwood, Ill, Masters Press.

- ↑ For more on the early spread of basketball, see: Naismith, J. (1996) Basketball: its origin and development. Bison Books ed. Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press.

- ↑ For an early history on college basketball, see: Anon (2009) OCLC: 472605763. Summitt: a pictorial retrospective of college basketball’s greatest coach. Battle Ground, WA, Pediment Pub.

- ↑ For a post-war history of basketball, see: Mark Dyreson & J. A. Mangan (eds.) (2007) OCLC: ocm63397310. Sport and American society: exceptionalism, insularity, and ‘imperialism’. Sport in the global society. London ; New York, Routledge, pg. 46.

- ↑ For an early history of professional basketball, see: Nelson, M.R. (2009) OCLC: 431502825. The National Basketball League: a history, 1935-1949. [Online]. Jefferson, N.C., McFarland & Co. Available from: http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=1593750 [Accessed: 10 August 2016].

- ↑ For a history of the NBA and its rules, see: Surdam, D.G. (2012) The rise of the National Basketball Association. Urbana, University of Illinois Press.

- ↑ For history on the ABA and NBA, see: Pluto, T. (2007) OCLC: 153578380. Loose balls: the short, wild life of the American Basketball Association. New York, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

- ↑ For more on the internationalization of basketball, see: Markovits, A.S. & Rensmann, L. (2010) OCLC: 650308562. Gaming the world: how sports are reshaping global politics and culture. [Online]. Princeton, Princeton University Press, pg. 89.

- This page was last edited on 2 October 2021, at 21:43.

- Privacy policy

- About DailyHistory.org

- Disclaimers

- Mobile view

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

History of Basketball

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Race and sport Follow Following

- Basketball Follow Following

- Business Administration Follow Following

- Philhellenism Follow Following

- Paul Bowles's Short Fiction Follow Following

- Thomas Warton Follow Following

- Paul Bowles Follow Following

- Sports and race Follow Following

- Sports Communication Follow Following

- Albert Murray Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

THE PLIGHT OF THE PRE-PENSION PLAYERS Find out how the league's pioneer players are getting the short end of the stick. For more information on the Pre-1965 NBA Players Association, or to order copies of Vintage NBA from the Pre-1965 NBA Players Association [for only $20, including shipping], write to: Bill Tosheff XNBA.org The Pre-1965 NBA Players Association 1455 2nd Ave. Suite 1402 San Diego, CA 92101 619-899-2504 & 619-234-3500

BASKETBALL LOGO INDEX PAGE Major leagues [NBA, ABA, ABL, etc.], minor leagues [CBA, USBL, etc.], women's leagues [WBL, WNBA, ABL, etc.]

HISTORICAL BASKETBALL STATISTICAL DATABASE Online statistical database for the BAA/NBA, NBL and ABA [Courtesy of Bob Chaikin]

NBDL National Basketball Developmental League 2001-02 to Present NBL National Basket Ball League 1898-99 to 1903-04 NBL National Basketball League 1926-27 NBL National Basketball League1929-30 NBL National Basketball League1932-33 NBL National Basketball League1937-38 to 1948-49 NBL National Basketball League [Canada] 1993 to 1994 NPBL National Professional Basketball League 1950-51 NRL National Rookie League 2001 to Present NEBA New England Basketball Association 1904-05 NEBL New England Basketball League 1903-04 NEL New England League 1946-47 NYSL New York State League 1911-12 to 1916-17, 1919-20 to 1922-23 NYSPL New York State Professional League 1946-47 to 1948-49 NABL North American Basketball League 1964-65 to 1967-68 PCPBL Pacific Coast Professional Basketball League 1946-47 to 1947-48 PSL Pennsylvania State League 1914-15 to 1917-18, 1919-20 to 1920-21 PBL Philadelphia Basket Ball League 1902-03 to 1908-09 PBLA Professional Basketball League of America 1947-48 SBL Southern Basketball League 1947-48 to 1948-49 SBL Southwest Basketball League 1997-98 to Present ABA/EBA/UBA Atlantic Basketball Association/Eastern Basketball Alliance/United Basketball Alliance 1993-94 to Present USBL United States Basketball League 1985 to Present WBA Western Basketball Association 1974-75 WBA Western Basketball Association 1978-79 WMBL Western Massachusetts Basket Ball League 1903-04 WPBL Western Pennsylvania Basket Ball League 1903-04 WPBL Western Pennsylvania Basket Ball League 1912-13 WPBL Western Pennsylvania Basket Ball League 1914-15 WNBA Women's National Basketball Association 1997 to Present Women's Professional Basketball 1936 to Present · AllAmericanRedheads.com [John Molina] · EdmontonGrads.com [John Molina] · History of Women's Basketball [John Molina] · Machine Gun Moll - WBL Legend [John Molina] · Women's Basketball League [John Molina] WBL Women's Professional Basketball League 1978-79 to 1980-80 WBL World Basketball League 1988 to 1992

PRO BASKETBALL LISTS Team Abbreviations 100 Greatest Players of the 20th Century 10 Greatest Teams of the 20th Century ABA/NBA Exhibition Games Al Hoffman's Adjusted Stats - Introduction · 1946-1967 · 1967-1976 · 1976-1988 · 1988-2000 · 1967-1976 · 1976-1988 · 1988-2000 · 1967-1976 · 1976-1988 · 1988-2000 All-Star Game Participants All-Time Greats Bill Spivey's Professional Career Highlights History of Basket Bowl A fictional account of the ABA/NBA championship game Deceased Players European League Champions Hall of Fame Inductees Left-Handed Players Most Teams in a Career and a Season NBA/ABA Attendance History BAA/NBA/ABA Finals/Championship Series Participants Most Games With One Franchise Entire Career With One Franchise Relatives in the NBL/BAA/NBA/ABA Wilt Chamberlain Career Retrospective

BARNSTORMING TEAMS AND PROFESSIONAL TOURNAMENTS Harlem Globetrotters All-Time Roster Harlem Globetrotters - Minneapolis Lakers Box Scores Jackie Robinson and the Los Angeles Red Devils 1941 Rosenblum Tournament World Professional Basketball Tournament World Series of Basketball

AMATEUR BASKETBALL LISTS Amateur Athletic Union/National Industrial Basketball League History Olympic Games NCAA All-American NCAA Annual Awards NCAA Tournament NCAA Yearly Final Polls BAA/NBA/ABA DRAFT HISTORY BAA/NBA

- 1946-47 to 1959-60

- 1960-61 to 1969-70

- 1970-71 to 1979-80

- 1980-81 to 1989-90

- 1990-91 to 2000-01

- 2001-02 to 2010-11

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sports (Basel)

Improving Practice and Performance in Basketball

Basketball is ranked in the top three team sports for participation in the Americas, Australia, Europe, Southeast Asia, and Western Pacific nations, making it one of the most popular team sports worldwide [ 1 ]. The physical demands and high popularity of basketball present a wide range of potential applications in society. At one end, basketball may offer a vehicle to combat high inactivity rates and reduce economic health burdens for government officials and health administrators in many countries due to the popularity of the game combined with the evidence supporting recreational basketball eliciting intense physical demands with low perceptual demand [ 2 ]. At the other end, professional basketball competitions have emerged in over 100 countries with more than 70,000 professional players globally [ 3 ], creating a lucrative business that provides legitimate career pathways for players and entertainment for billions of people. Despite the wide range in application, it is surprising how little research has been conducted in basketball relative to other sports. For instance, a rudimentary search on PubMed showed basketball to yield considerably less returns than other sports with a similar global reach and comparable returns to sports governed in less regions of the world ( Table 1 ). Consequently, we sought to edit a Special Issue on “Improving Practice and Performance in Basketball” to provide a collection of studies from basketball researchers across the world and increase available evidence on pertinent topics in the sport. In total, 40 researchers from 16 institutions or professional bodies across nine countries contributed 10 studies in the Special Issue.

Returns on Scopus for basketball relative to other sports.

Note: Search conducted on August 9th 2019 via https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ and was restricted to past five years. * The number of countries identified as members by the international governing body; † field hockey included 137 member countries, while ice hockey included 76 member countries; ‡ rugby union included 119 member countries, while rugby league included 68 member countries.

Most research conducted in basketball has focused on athletic populations. For instance, a review of the 228 studies returned on PubMed for “basketball” in 2019 (up to August 9th) indicates over 25% of studies focused on the incidence, treatment, rehabilitation, or screening of injuries, while 11% of studies described physical, fitness, or functional attributes in competitive basketball players. These trends emphasize the strong interest in understanding injury prevention and treatment in basketball, as well as attributes which may underpin successful players, both of which are oriented towards optimizing player and team performance. Regarding enhancing performance, an increasingly popular field of research in basketball is examining monitoring methods (7% of PubMed studies in 2019) to better understand demands placed on players across the season and provide evidence for decision-making regarding player management. Several reviews have recently been published highlighting the interest in quantifying game [ 4 ] and training demands [ 5 ], using heart rate monitoring [ 6 ], and applying microsensors to measure player workloads [ 7 ] in competitive basketball. Available monitoring technologies provide basketball coaches and high-performance staff with a plethora of data regarding player fitness, workloads, and fatigue status to inform decisions regarding training prescription and recovery opportunities for minimizing injury risk and optimizing performance. In turn, basketball research has readily used game-related statistics (3% of PubMed studies in 2019) to describe player and team performance, which provide an expansive reservoir of data, usually publicly available, to link outcomes of interest to performance. Consequently, our Special Issue was open to research exploring various current topics that have potential to impact practice in basketball.

In keeping with the recent trends in basketball research, the Special Issue contains two reviews with one focused on exploring the utility of various monitoring strategies to detect player fatigue [ 8 ] and the other identifying issues to consider around the extensive travelling requirements in the National Basketball Association (NBA), the premier global basketball competition [ 9 ]. Both reviews highlight the practical aspects relating fatigue and travel in basketball, including potential implications for injury, workload management, recovery, and assessment in players. Furthermore, two applied studies in the Special Issue examine workload monitoring in basketball, with one exploring the impact of game scheduling on accelerometer-derived workload [ 10 ] and the other examining changes in jump kinetics and perceptual workload across the season [ 11 ]. An additional three studies in the Special Issue identified game-related statistics explaining game outcomes and regional differences in various elite competitions (Olympics [ 12 ], EuroBasket [ 13 ], and Continental Championships [ 14 ]). The remaining three studies described physical [ 15 , 16 ] and skill [ 17 ] attributes in various player samples. It should also be noted our Special Issue addresses an important issue of increasing research in female athletes, who have traditionally been under-represented in the literature compared to male basketball players, with seven of the eight original studies (88%) containing female basketball players.

The immediate future of basketball research in high-performance settings is highlighted by issues faced in practice. Specifically, key players are missing games or being rested for “load management” in the NBA to reduce player injury risk, despite some initial evidence suggesting greater rest during the regular season (6 ± 1 vs 1 ± 1 games) does not reduce injury incidence or performance in the playoffs [ 18 ]. Likewise, condensed game schedules [ 19 ] and the total minutes played in individual games [ 20 ] have been shown to have no significant effects on injury risk in NBA players. In contrast, other research suggests the total number of games played in a season impacts injury risk in the NBA [ 21 ], highlighting the need for further research on this topic to gather a definitive understanding regarding the effects of managing player workloads on injury risk. In fact, more research needs to build upon the extensive descriptive evidence already available and identify modifiable factors contributing to injuries in basketball players for coaches and high-performance staff to control risk as much as possible. In addition to injury, future basketball research should seek to further examine the efficacy of logical and practical intervention strategies on player performance. For example, an increasing number of studies are examining the utility of different training approaches, including resistance training [ 22 ], court-based conditioning [ 23 ], and games-based drills [ 5 ], as well as nutritional strategies [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ] and recovery practices [ 28 ] on performance outcomes. Furthermore, it is integral for future research assessing player performance to use basketball-specific assessments. In this regard, more research is recognizing the need for greater specificity in measuring performance in basketball, with an increased number of studies exploring the utility of basketball-specific testing protocols to assess relevant physical attributes [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ] as well as in-game statistics [ 33 ] and workloads [ 34 ] to quantify player performance in a robust manner with increased application to actual competition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The history of basketball: A timeline

- 1 The Early Years of Basketball

- 2 Late 1800s- 1930s

- 3 The 1940s - 1970s

- 4 1980s - Present

6 takeaways from "Life & Basketball: The Rise of Lethal Shooter"

Lethal Shooter

© Koury Angelo

Life & Basketball: The Rise of Lethal Shooter

Head behind the scenes to meet one of basketball's most incredible men – chris matthews, aka lethal shooter., the early years of basketball.

© Koury Angelo/Red Bull Content Pool

Top 25 college basketball arenas

Late 1800s- 1930s.

Arike Ogunbowale

© Sean Berry

The 1940s - 1970s

1980s - present.

Red Bull Half Court World Final in Cairo, Egypt on October 1, 2022

© Markus Berger / Red Bull Content Pool

Validity of 3-D Markerless Motion Capture System for Assessing Basketball Dunk Kinetics – A Case Study

Authors: Dimitrije Cabarkapa 1 , Andrew C. Fry 1 and Eric M. Mosier 2

- Jayhawk Athletic Performance Laboratory, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS

- Northwest Missouri State University, Maryville, MO

Corresponding Author: Dimitrije Cabarkapa, MS, CSCS, NSCA-CPT, USAW 1301 Sunnyside Avenue, Lawrence, KS 66045 University of Kansas E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +1 (785) 551-3882

Basketball is one of the most popular international sports, but the current sport science literature does not directly address on-court performance such as force and power during a game. This case study examined the accuracy of a three-dimensional markerless motion capture system (3-D MCS) for determining the biomechanical characteristics of the basketball dunk. A former collegiate (NCAA Division-I) basketball player (age=26 yrs, height=2.08 m, weight=111.4 kg) performed 30 maximum effort dunks utilizing a two-hands, no-step, two-leg jumping approach. A uni-axial force plate (FP) positioned under a regulation basket sampled data at 1000 Hz. Additionally, a 3-D MCS composed of eight cameras placed 3.7 m high surrounding the recording area collected data at 50 Hz, from which ground reaction forces were derived using inverse dynamics. The dunks were analyzed by both systems for peak force and peak power. Peak force (X±SD) was similar (p<0.05) for both systems (FP= 2963.9±92.1 N, 3-D MCS= 3353.2±255.9 N), as was peak power (FP= 5943±323, 3-D MCS= 5931±700 W). Bland-Altman plots with 95% confidence intervals for both force and power indicated all measurements made with the 3-D MCS accurately assessed peak force and peak power during a basketball dunk as performed in the current study. These data provide strength and conditioning professionals with a better understanding of the magnitude of forces and powers that athletes experience during a basketball game, as well as validate use of a novel technology to monitor athletes’ progress and optimize overall athletic performance.

NCAA Realignment: Impact upon University ‘Olympic’ Sports

Authors: Stephen W. Litvin, Crystal Lindner and Jillian Wilkie

Corresponding Author: Stephen W. Litvin, DBA Professor, School of Business College of Charleston 66 George Street Charleston, South Carolina 29424 [email protected] 843-953-7317

Stephen Litvin is a professor in the School of Business of the College of Charleston. Crystal Lindner and Jillian Wilkie are students at the College of Charleston and Research Assistants within the School’s Office of Tourism Analysis.

NCAA Realignment: Impact upon University ‘Olympic’ Sports

Conference realignment has in recent years led to a “case of intercollegiate musical chairs” (2, p. 254). This research paper looks at the issue from a new perspective. While past research has almost exclusively focused on football, this research considers the impact that affiliation change has upon universities’ non-football sports. The findings suggest the move has been challenging for these teams.

Special Edition: Refuting IOC’s Plan to End Modern Pentathlon Competition

The recent decision of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to drop the modern pentathlon from the Olympic Games has prompted Dr. Thomas P. Rosandich, president of the United States Sports Academy, and the editors of The Sport Journal to publish a special edition bringing attention to this grave matter. We join the call that has gone out from various quarters to retain the modern pentathlon. It is a vital component of the Olympic Games and an important historic tradition. The special edition features the opinions of several IOC members, reproduced from four sources.

The first source is an abridged version of a letter from Klaus Schormann, president of the Union Internationale de Pentathlon Moderne (UIPM), to IOC President Jacques Rogge:

Monaco, 5 November 2002

According to our discussion during our last meeting in Lausanne [Switzerland], the UIPM is sending a summary of its arguments and response to the Program Commission report which it feels appropriate to be considered for the sport of modern pentathlon to remain in the Olympic program. These arguments, which cover a larger spectrum than those developed by the Program Commission, should be given to the IOC executive board prior to their last meeting in November, and to the IOC members in case the matter would be voted during the session in Mexico.

I. Answer to the arguments of the Program Commission

— Lack of global participation by nations and individual athletes Ninety-four nations from five continents are now affiliated with the UIPM (more are coming, as they are in establishment procedure), while the Olympic Charter requires 75 nations in four continents. The sport meets the criteria of the Olympic Charter. We want to remind that Pierre de Coubertin founded the sport in 1912 from scratch, on the model of the ancient pentathlon, the symbolic and complete sport of the Ancient Games, which means that this sport has never stopped growing since its creation.

—Significant expense of practicing the sport, with resulting difficulties in major development Modern pentathlon is not more significantly expensive than most of the other Olympic sports or than those willing to enter the Olympic program. The change of its format to the one-day in 1992 and the new shooting system (air pistols instead of guns) have reduced the costs for organizing and training. Facilities already used by other sports are also for modern pentathlon, inside and outside of Olympic Games, for competing, training, and studying. The new compactness of venues in many cities gives new possibilities for modern pentathlon. The reduction of the costs for sport equipment (including horse riding) brings new possibilities. It is to be noted that pentathletes do not need to have a horse of their own, are not charged for that in competitions, and that the use of local horses does not require any guarantee.

—High operational complexity Experience with organization of UIPM events on all continents and in the previous Olympic Games shows that all organizers were able easily to offer facilities for the five disciplines of modern pentathlon (shooting, fencing, swimming, riding, running) within walking distance. It is to be noted that no specific venue is required for the modern pentathlon, and that UIPM has developed a policy of polyvalent international technical officials. Modern pentathlon helps to a more efficient use of venues used at Games time. The official report of the XXVII Olympiad made by SOCOG makes a clear statement on this.

— Relatively low broadcast and press coverage The relatively low broadcast stated by the Program Commission does not fit the statistics established by the UIPM, which can easily be checked. . . . All major UIPM events on all five continents were covered by international TV during the last seven years. Due to its TV coverage, the UIPM has developed a successful marketing program . . . which is in very good standing in comparison with other Olympic sports.

II. Arguments which should be taken into consideration by the IOC to keep modern pentathlon in the Olympic program

— Modern pentathlon is the only sport that has ever been created in its entirety by Pierre de Coubertin and the IOC, as the Ancient sports were created by the Ancient Greeks, and therefore [has] a symbolic value within the Olympic Games. It was especially designed on the model of the ancient pentathlon in order to show all possible skills developed, through five sport events, in one single athlete, and not for a massive number of participants. It is important for the sake of the Olympic tradition.

—Modern pentathlon, from the skills it develops, has an educational value. [It is] a complete sport: On the physical side, swimming, running are the basic disciplines; on the mental side, shooting requires stress control and a precise technique; on the intellectual side, fencing requires adaptability and intelligence; riding an unknown horse requires a mix of adaptability, self-control, and courage.

—Modern pentathlon has an entertainment function at the Olympic Games. Since the Atlanta Olympic Games and the introduction of the one-day format, the interest of spectators at Games time has grown dramatically, which can be easily shown by statistics on the number of spectators at the Sydney Games (full venue and 15,000 spectators per session) and by an independent survey published in the Olympic Review.

— An Olympic sport with reasonable number of athletes and with a high representation of NOCs. Only 32 women and 32 men, a total of 64 athletes (in fact around 0.5% of the total athletes number), competing for only two days (six medals), which means that modern pentathlon, as one of the 28 sports of the Olympic program, has a very limited impact on the overall number of athletes in the Games. Remarks: The average number of athletes for the other sports is (10500 – 64) /27 = 386/ At the same time, modern pentathlon gives to many NOCs the possibility to take part in the Olympic Games. In Sydney 48 pentathletes competed while 24 NOCs were represented. This means 50% of the quota was dedicated to NOCs’ representation, which is the highest value of all Olympic sports.

— A drug-free sport. Since the one-day format has been created and due to the permanent efforts of the UIPM, modern pentathlon has become a drug-free sport. The one-day format has discouraged prohibited behaviors, as there is no interest in using drugs for shooting when fencing comes right after it. Anabolic substances are not useful in a sport that does not place the success of the winner only on his physical skills, but in his overall physical and intellectual harmony.

—UIPM, a flexible organization. In addition to the changes in the modern pentathlon’s format, the UIPM has created an ad hoc commission looking at the optimal evolution of the sport for the future. The purpose is to keep to symbolic construction of modern pentathlon in placing its complete skills first, but looking, at the same time, at its events in order to fit with the evolution of sport practice in general. This commission already collaborates with the International Pierre de Coubertin Committee and intends to do the same with the other international federations and the IOC.

—Modern pentathlon is a symbolic sport for the Olympic Movement. Modern pentathlon is a true representation of the Olympic Movement. The five Olympic rings are reflected in modern pentathlon’s five events and participation from all five continents. It is a true sport of the Olympic Games, created by the founder of the Modern Games, Pierre de Coubertin, and reflecting the ideals embodied by the Olympic Movement. It has to remain an indefatigable part of it.

The concept and the philosophy of the pentathlon are 2,710 years old, as described by Aristotle: “The most perfect sportsmen are the pentathletes, because in their bodies strength and speed are combined in beautiful harmony.” Created by the Greeks and renovated by the founder of the [Modern] Games, it shows the symbolic complete athlete in his body, will, and mind as stated and described in Fundamental Principle 2 of the Olympic Charter. Let’s keep this part of the soul of the Olympics, let’s keep it on the field of play, let’s see it on the stadium, and not only in the Olympic Museum in the future!

The 28 Sports of the Olympic Program, Participating NOCs, and Disqualification Quotas

The second source reproduced in this special edition is HSH Prince Albert Monaco’s address to the IOC in Switzerland on behalf of the cause of the modern pentathlon:

HSH Prince Albert reaffirms Modern Pentathlon as soul of Olympic Movement, to be maintained for the sake of olympic tradition & values

I’m here not only because I am the honorary president of the UIPM, nor because Monaco is host to the headquarters of the UIPM. I’m here above all as an IOC member who is fearful that some very important part of the values and the philosophy of the Olympic Movement handed down to us by Baron Pierre de Coubertin might be lost forever if modem pentathlon should disappear from the program. The cultural dimension of this sport, its ancient roots and the educational value of its different components, are an important legacy for the IOC, for the Olympic Movement. This dimension is more important than the sport itself; the consequences of its demise larger than any one of us in this room.

Some people will argue that tradition and values are not the only elements that should guide us. If you look around you, watch TV, or read a newspaper article, you will find quite a few people saying the opposite: that a society has lost points of reference, that values have diminished. Why not continue to provide our youth with the kind of values and symbol that this sport possesses, and that they obviously are looking for? Why challenge a sport that celebrates and showcases the versatile, complete athlete? According to the latest figures from the Sydney Olympic Games, more people than ever seem interested in watching athletes test their abilities in combined events.

Is it right to deny the development of a sport that is growing in popularity and has sustained youth programs? There is a quotation from a young Cuban athlete in your brochure, “I want to compete in modem pentathlon at the Beijing Olympic Games.” Is it right to deny Jose Fernandez and his friends the opportunity to realize his dreams in an existing Olympic sport?

Having said all this, we are not stifled in tradition, we are not dinosaurs, we are willing to be open to change, if it is for the better.

The American philosopher and author Tom Wolfe once wrote, in his book The Search for Excellence, “We must learn to accept change, as much as we hated to in the past.” I’m sure he meant changes in our society, changes in behavior, changes in economics, etc., not changes in our values.

The values of education and culture, and understanding through sport, are everlasting and something we in the Olympic Movement should hold sacred.

The third source reproduced in the special edition is a further communication written by Klaus Schormann, UIPM president:

I am just back in my home after a lot of traveling. . . . In Busan during the Asian Games (modern pentathlon was included, with the whole competition-program: individual women/men and relay women/men and team-medal. I could speak with a lot of IOC members, NOC presidents, and media people. As you can see [Table 2], my schedule for the next weeks is very busy; therefore, I think we should meet in Colorado Springs at the GAISF meeting (20 to 24.11.2002). I send you some documents about the “IOC Program Commission” and our actions now, for your information. UIPM needs from all institutions of international-sport-scene support: Public statements . . . for modern pentathlon are needed.

UIPM President Klaus Schormann’s Schedule, September to December 2002

The fourth source reproduced in the special edition is an abridged version of a UIPM press release dated 8 October 2002:

UIPM Delegation Visits IOC Regarding the Olympic Program; HSH Prince Albert Reaffirms Modern Pentathlon as the Soul of the Olympic Movement, to be Maintained for the Sake of Olympic Tradition and Values; International Pierre De Coubertin Committee and DeCoubertin’s Family Call for Pentathlon’s Respect and Promotion

On 4 October, a UIPM delegation composed of President Klaus Schormann, Honorary President HSH Prince Albert of Monaco, First Vice President Juan Antonio Samaranch, and Secretary General Joel Bouzou was welcomed at the IOC headquarters by IOC President Jacques Rogge, accompanied by Sport Director Gilbert Felli and his new assistant, Olivier Lenglet.

The purpose of the meeting was to answer to the Program Commission’s recommendation to the IOC executive board and to present additional arguments to be considered by the IOC executive board before their final decision during their meeting in Mexico City, 26 and 27 November.

After the opening by IOC President Rogge, UIPM President Klaus Schormann referred to the letter sent to the IOC that answered the points raised by the technical report of the Program Commission. [As Schormann noted,] “We now have more than 95 countries in the five continents. . . . De Coubertin started the sport from scratch in 1912, and the media coverage of our events has dramatically increased since the adoption of the one-day format. Our sport is only using existing venues during the Games and therefore is not expensive, as stated in the report. Equally, compact venues in modern cities allow more and more pentathletes to practice the sport and combine it with studies.

President Schormann also mentioned the surveys made during the last Olympic Games by an independent observer, Prof. Dr. Mfiller from the research group of the Gutenberg University in Mainz, and by SOCOG, which both support the UIPM counter-arguments. Dr Rogge confirmed that he took into account the point made by President Schormann concerning the flexibility of UIPM in terms of the sports evolution.

UIPM Secretary General Bouzou recalled that modem pentathlon does not need any specific venue for the Games; that most modem cities have multisport complexes adapted to the organization of modem pentathlon; that nine modem pentathlon major competitions are seen on international TV in the five continents; that, as stated by SOCOG (in a post-Games report), “[T]he quality of competition and sports presentation, combined with the most comprehensive television coverage ever of modem pentathlon in Olympic Games history, ensured first-class viewing for live spectators and global television audiences.” He also acknowledged the fact that modem pentathlon is not, and will never be, practiced by millions of athletes throughout the world. However, it was never designed for this by the founder of the Games, Pierre de Coubertin, but to be used as a living symbol of all values within a single sport. This was the reason why exceptional personalities like General Patton or Chevalier Raoul Mollet chose this sport in their respective athletic times.

UIPM Vice President Samaranch reminded that 15,000 spectators attended each of the two days of modem pentathlon at the Sydney Olympic Games, in sold-out venues, and that there are only 64 athletes competing in modem pentathlon, which represents only 0.5% of the overall number, and, therefore, that taking the sport out of the program would not affect the reality in terms of cost.

IOC President Rogge, following the presentation of all the arguments, informed the UIPM delegation that he would ensure they would all be duly reported on to the IOC executive board.

Professor Dr. Norbert Muller, president of the International Pierre de Coubertin Committee, wrote a letter to the IOC president saying that he had been “informed with great regrets about the proposal of the program commission,” adding that, “this sport represents the real legacy of Pierre de Coubertin, which he elaborated personally when he wanted to showcase the Perfect Olympic Man or Woman.” [Muller] transmitted an appeal from the committee, saying, “[T]he personal legacy of Pierre de Coubertin should be respected and modem pentathlon permanently included.”

Mr. Geoffroy de Navacelle de Coubertin, the great-nephew of Pierre de Coubertin, also wrote to the IOC president, saying, “Let me tell you my astonishment and my emotion. I have always decided not to interfere with the IOC business. I am simply concerned in making sure that the achievements and the philosophy of Pierre de Coubertin will be respected. This sport is the most symbolic one in showing the perfect athlete. Should you not promote and support it in order to make it grow, instead of only promoting ‘specialists’ which media like so much?” De Coubertin had contacted Schormann . . . in order to create a permanent Pierre de Coubertin Commission within UIPM, that he would lead, the role of which will be to promote the philosophy of the founder “on the ground,” particularly through modem pentathlon events, in close cooperation with the International Pierre de Coubertin Committee, throughout the entire world. The Pierre de Coubertin Commission was established 1 October 2002, comprising the following members: de Coubertin, Schormann, Muller, Bouzou, and modern pentathlon Olympic champions Dr. Stephanie Cook [of Great Britain] and Janus Peciak [of Poland].

Author’s Note:

Correspondence regarding this articLEwhould go to:

Union Internationale de Pentathlon Moderne (UIPM) Tel. +377,9777 8555 Fax.+377 9777 8550 E-mail: [email protected] For more on Pentathlon, visit the website: http://www.pentathlon.org 08.10.2002/ JB

A Review of Service Quality in Corporate and Recreational Sport/Fitness Programs

This article is a review of the literature related to the study of service quality in corporate and recreational sport and fitness programs. It considers earlier discussions of conceptualization and operationalization aspects of consumers’ perceptions of service quality. It reviews several models used by researchers in the past, as well as more recent approaches to understanding the constructs of service and service quality and the various means used to measure them.

Quality of service has been studied within the discipline of business management for years, because the market is increasingly competitive and marketing management has transferred its focus from internal performance (such as production) to external interests like customer satisfaction and customers’ perceptions of service quality (Gronroos, 1992). However, the concept of service quality has only recently—over the last two decades—gained attention from sport and recreation providers and those who study them (Yong, 2000). The service-quality framework known as SERVQUAL comprises a traditional disconfirmatory model and was the first measurement tool to operationalize service quality. Although it made a contribution to the field of service quality and was very popular among service-quality researchers in many areas, SERVQUAL proved insufficient due to conceptual weaknesses in the disconfirmatory paradigm and to its empirical inappropriateness.

Later service-quality frameworks included a greater number of dimensions than SERVQUAL offered. Most recent models, such as Brady’s (1997) hierarchical multidimensional model, have synthesized prior approaches and suggest the complexity of service-quality perception as a construct. Because of this complexity, despite numerous efforts in both business management and the sport/fitness field, the study of service quality is still in a state of confusion. No consensus has been reached on its conceptualization or its operationalization of consumers’ perceptions of service quality.

Service and Service Quality

Service quality has long been studied by researchers in the field of business management. However, they have reached no consensus concerning how the service quality construct is best conceptualized or operationalized. In presenting the literature that reflects this lack of consensus, it is first necessary to focus on the definitions and characteristics of service and service quality. The concept of service comes from business literature. Many scholars have offered various definitions of service. For example, Ramaswamy (1996) described service as “the business transactions that take place between a donor (service provider) and receiver (customer) in order to produce an outcome that satisfies the customer”(p. 3). Zeithaml and Bitner (1996) defined service as “deeds, processes, and performances” (p. 5). According to Gronroos (1990),

A service is an activity or series of activities of more or less intangible nature that normally, but not necessarily, take place in interactions between the customer and service employees and /or systems of the service provider, which are provided as solutions to customer problems. (p. 27)

Some researchers have viewed service from within a system-thinking paradigm (Lakhe & Mohanty, 1995), defining service as

a production system where various inputs are processed, transformed and value added to produce some outputs which have utility to the service seekers, not merely in an economic sense but from supporting the life of the human system in general, even maybe for the sake of pleasure. (p. 140)

Yong (2000) reviewed definitions of service and noted the following features of service that are important to an understanding of the concept. First, service is a performance. It happens through interaction between consumers and service providers (Deighton, 1992; Gronroos, 1990; Ramaswamy, 1996; Sasser, Olsen, & Wyckoff, 1978; Zeithaml & Bitner, 1996). Second, factors such as physical resources and environments play an important mediating role in the process of service production and consumption (American Marketing Association, 1960; Collier, 1994; Gronnroos, 1990). Third, service is a requirement in terms of providing certain functions to consumers, for example problem solving (Gronroos, 1990; Ramaswamy, 1996). From these points Yong (2000) concluded that “a service, combined with goods products, is experienced and evaluated by customers who have particular goals and motivations for consumers for consuming the service.” (p. 43)

Among researchers generally, there is no consensus about the characteristics of service. According to Yong (2000), their various conceptualizations fall into two groups. First, there are those researchers who view the concept from the perspective of service itself. They pay attention to the discrepancy between marketing strategies for service and goods, in an approach that differentiates service (intangibles) from goods (tangibles). The suggestion is that distinct marketing strategies are appropriate for the two concepts. Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1985) as well as Zeithaml and Bitner (1996) identified the following features of service that distinguish it from goods: Service is intangible, heterogeneous, simultaneous, simultaneous in production and consumption, and perishable.

Pointing out the unique features of service advances understanding of the concept, but it has drawn criticism, for example because the identified features are not universal across service sectors. As Wright (1995) noted, first, a service industry depends more on tangible equipment to satisfy customers’ demands, while some customers do not care whether or not goods are tangible. Second, some service businesses are well standardized; an example is franchise industries (Wright, 1995). In addition, some customers value equality and fairness in the service provided. Third, many services are not simultaneously produced and consumed (Wright, 1995). Fourth, highly technological and equipment-based services could be standardized. Critics other than Wright (Wyckham, Fitzroy, & Mandry, 1975) have argued that the four-point approach to service ignores the role of customers.

The second group of researchers conceptualizing service comprises those who view service from the perspective of service customers. These researchers focus on the utility and total value that a service provides for a consumer. This approach points out that service combines tangible and intangible aspects in order to satisfy customers during business transactions (Gronroos. 1990; Ramaswamy, 1996). The approach implies that because consumers evaluate service quality in terms of their own experiences, customers’ subjective perceptions have great impact upon service businesses’ success or failure (Shostack, 1997).

Conceptualization and Operationalization of Service Quality

Although researchers have studied the concept of service for several decades, there is no consensus on how to conceptualize service quality (Cronin & Taylor, 1992; Rust & Oliver, 1994), in part because different researchers have focused on different aspects of service quality. Reeves and Bednar (1994) noted that “there is no universal, parsimonious, or all-encompassing definition or model of quality” (p. 436). The most common definition of service quality, nevertheless, is the traditional notion, in which quality is viewed as the customer’s perception of service excellence. That is to say, quality is defined by the customer’s impression of the service provided (Berry, Parasuraman, & Zeithaml, 1988; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1985). This definition assumes that customers form a perception of service quality according to the service performance they experience and in light of prior experiences of service performance. It is therefore the customer’s perception that categorizes service quality. Many researchers accept this approach. For example, Bitner and Hubbert (1994) defined quality as “the consumer’s overall impression of the relative inferiority/superiority of the organization and its services” (p. 77). But their definition of service quality differs from that of the traditional approach, which locates service quality perception within the contrast between consumer expectation and actual service performance (Gronroos, 1984; Lewis & Booms, 1983; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1985; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1990).

Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1985) viewed quality as “the degree and direction of discrepancy between customers’ service perception and expectations.” According to this approach, services are different from goods because they are intangible and heterogeneous and are simultaneously produced and consumed. Additionally, according to the disconfirmation paradigm, service quality is a comparison between consumers’ expectations and their perceptions of service actually received. Based on the traditional definition of service quality, Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1985) developed their gap model of perceived service quality. The model incorporates five gaps: (a) the gap between management’s perceptions of consumer expectations and expected service, (b) the gap between management’s perceptions of consumers’ expectations and the translation of those perceptions into service-quality specification, (c) the gap between translation of perceptions of service-quality specification and service delivery, (d) the gap between service delivery and external communications to consumers, and (e) the gap between the level of service consumers expect and actual service performance. This disconfirmation paradigm conceptualizes the perception of service quality as a difference between expected level of service and actual service performance. The developers of the gap model proposed 10 second-order dimensions consumers in a broad variety of service sectors use to assess service quality. The 10 are tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, competence, courtesy, credibility, security, access, communication, and understanding (Parasuraman et al., 1985).

Using these 10 dimensions, Parasuraman et al. (1988) made the first effort to operationalize the concept of service quality. They developed an instrument to assess service quality that empirically relied on the difference in scores between expectations and perceived performance. Their instrument consisted of 22 items, divided along the 10 second-order dimensions, with a seven-point answer scale accompanying each statement to test the strength of relations. The 22 items were used to represent 5 dimensions, ultimately: reliability, responsiveness, tangibles, assurance, and empathy. Yong (2000) described the five as follows:

Reliability refers to the ability to perform the promised service dependently and accurately. Responsiveness reflects the willingness to help a customer and provide prompt service. Tangible refers to the appearance of the physical facilities, equipment, personnel and communication material. Empathy refers to caring, individualized attention the firm provides its customer. (p. 66)

In their seminal study, Parasuraman and colleagues used SERVQUAL to measure service quality as the gap between expectation and perception in several venues: an appliance repair and maintenance firm, retail banks, a long-distance telephone provider, a securities broker, and credit card companies (Parasuraman et al., 1985). The study provided a comprehensive conceptualization of service quality, and it marked the first time, in service-quality research, that an instrument for measuring perceived service quality was used. It became very well known among service-quality researchers.

However, numerous researchers challenged the usefulness of the SERVQUAL scale as a measure of service quality (e.g., Babakus & Boller, 1992; Brown, Churchill, & Peter, 1993; Carmen, 1990; Cronin & Taylor, 1992; Dabholkar, Thorpe, & Rentz, 1996). Carmen (1990) selected four service settings that were quite different from those in the original test and found that in some situations, SERVQUAL must be customized (items added or edited), despite its introduction as a generic instrument measuring service quality in any sector. In addition, Carmen suggested that SERVQUAL’s five dimensions are insufficient to meet service-quality measurement needs, and that measurement of expectation using SERVQUAL is problematic. Finn and Lamb (1991) argued that “the SERVQUAL measurement model is not appropriate in a retail setting” (p. 487). Furthermore, they argued, “retailers and consumer researchers should not treat SERVQUAL as an ‘off the shelf’ measure of perceived quality. Much refinement is needed for specific companies and industries” (p. 489). According to Brown, Churchill, & Peter (1993) SERVQUAL’s use of difference between scores causes a number of problems in such areas as reliability, discriminate validity, spurious correlations, and variance restriction. Finally, Cronin and Taylor (1992) argued that the disconfirmation paradigm applied by SERVQUAL was inappropriate for measuring perceived service quality. The paradigm measures customer satisfaction, not service quality, and Cronin and Taylor’s study employing solely the performance scale SERVPERF showed SERVPERF to outperform SERVQUAL.

SERVQUAL’s shortcomings result from the weakness of the traditional disconfirmatory definition of service quality which it incorporates. Yong (2000) notes several problems in this traditional definition of service quality. First, customers’ needs are not always easy to identify, and incorrectly identified needs result in measuring conformance to a specification that is improper. Schneider and Bowen (1995) pointed out that

[C]ustomers bring a complex and multidimensional set of expectations to the service encounter. Customers come with expectations for more than a smile and handshake. Their expectations include conformance to at least ten service quality attributes (i.e., Parasuraman et al.’s 10 dimensions—reliability, responsiveness, competence, access, courtesy, communication, credibility, security, understanding, and tangible).” (p. 29)

Second, the traditional definition fails to provide a way to measure customers’ expectations, and expectations determine the level of service quality. Because customer expectations may fluctuate greatly over time (Reeves & Bednar, 1994), a definition of quality based on expectation cannot be parsimonious. It is invalid, empirically speaking, to use the disparity of scores for expectation and scores for perceived service quality to measure service quality.

Oliver (1997) is another researcher who pointed out the traditional model’s difficulty distinguishing service quality from satisfaction. While perception of quality may come from external mediation rather than experience of service, consumers must experience satisfaction in person. In addition, judgments and standards of quality are based on ideals or perceptions of excellence, while judgments concerning satisfaction involve predictive expectations, needs, product category norms, and even expectations of service quality. Moreover, while judgments concerning quality are mainly cognitive, satisfaction is an affective experience (Bitner & Hubbert, 1994; Oliver, 1994). Service quality is influenced by a very few variables (e.g, external cues like price, reputation, and various communication sources); satisfaction, in contrast, is vulnerable to cognitive and affective processes (e.g., equity, attribution, and emotion). Quality is primarily long-term, while satisfaction is primarily short-term.

Discussing various analyses in terms of their definitions of service quality, Yong (2000) pointed out that service quality should not be defined using a disconfirmation paradigm (i.e., by comparing expectation and perceived quality). Indeed, since service quality may not necessarily involve customer experience and consumption, the disconfirmation paradigm does not clarify service quality (Yong, 2000). Furthermore, it is easier to measure service quality if judgment occurs primarily at the attribute-based cognitive level. Yong (2000) stated as well that customer perception of quality to date has been the main focus of service-quality research; consumers’ overall impressions determine service quality. Yong (2000) argues that what constitutes service changes from one service sector to another, so each sector’s consumers may perceive service quality differently, and that service quality is multidimensional or multifaceted. Finally, according to Yong (2000), service quality must be clearly differentiated from customer satisfaction.

Several researchers have approached service quality from perspectives quite different from that of Parasuraman et al. (1988). On the one hand, some scholars argue for multidimensional models of service quality. At first, Gronroos (1984) used a two-dimensional model to study service quality. Its first dimension was technical quality, meaning the outcome of service performance. Its second dimension was functional quality, meaning subjective perceptions of how service is delivered. Functional quality reflects consumers’ perceptions of their interactions with service providers. Gronroos’s model compares the two dimensions of service performance to customer expectation, and eventually each customer has an individual perception of service quality. McDougall and Levesque (1994) later added to Gronroos’s model a third dimension, physical environment, proposing their three-factor model of service quality. This later model consists of service outcome, service process (Gronroos, 1984), and physical environment. McDougall and Levesque (1994) tested the model with confirmatory factor analysis, using the dimensions of the SERVQUAL scale (which provided empirical support for the three-factor model). The three components from the above models, together with Rust and Oliver’s (1994) service product, represent one important aspect of services. All of them contribute to consumers’ perception of service quality (Yong, 2000).

On the other hand, Dabholkar, Thorpe, and Tentz (1996) proposed a hierarchical model of service quality that describes service quality as a level, multidimensional construct. That construct includes (a) overall consumer perception of service quality; (b) a dimension level that consists of physical aspects, reliability, personal interaction, problem solving, and policy; and (c) a subdimension level that recognizes the multifaceted nature of the service-quality dimensions. Dabholkar and colleagues found that quality of service is directly influenced by perceptions of performance levels. In addition, customers’ personal characteristics are important in assessing value, but not in assessing quality.

The two lines of thought on the modeling of service quality were combined by Brady (1997). He developed a hierarchical and multidimensional model of perceived service quality by combining Dabholkar, Thorpe, and Tentz’s (1996) hierarchical model and McDougall and Levesque’s (1994) three-factor model (Brady, 1997). Brady’s model incorporates three dimensions, interaction quality, outcome quality, and physical environment quality. Each dimension consists of three subdimensions. The interaction quality dimension comprises attitude, behavior, and expertise subdimensions. The outcome quality dimension comprises waiting time, tangibles, and valence. Finally, the physical environment quality dimension comprises ambient conditions, design, and social factors. Brady’s hierarchical and multidimensional approach is believed to explain the complexity of human perceptions better than earlier conceptualizations in the literature did (Dabholkar, Thorpe, & Rentz, 1996; Brady, 1997). Furthermore, empirical testing of Brady’s model shows the model to be psychometrically sound.

In a study of service quality in recreational sport, Yong (2000) further developed Brady’s (1997) model, proposing that perception of service quality occurs in four dimensions. The first is program quality: the range of activity programs, operating time, and secondary services. The second is interaction quality, or outcome quality. The third is environment quality. Yong tested his model with a two-step approach of structural equation modeling, and he supported multidimensional conceptualization of service-quality perception.

Perception of service quality is quite a controversial topic; to date no consensus has been reached on how to conceptualize or operationalize this construct. In its summarization of the existing literature about service quality, this article explored the concepts of service, service quality, consumer perception of service quality, and the conceptualization and operationalization of the service-quality concept. It covered several models of service quality, the earliest one of which was SERVQUAL. An application of the traditional disconfirmatory model, SERVQUAL represents the first effort to operationalize service quality. Although it made a great contribution to the field and was very popular among service-quality researchers in many areas, SERVQUAL is now thought to be insufficient because of conceptual weaknesses inherent in the disconfirmatory paradigm and also because of its empirical inappropriateness. Service-quality researchers working after SERVQUAL’s introduction proposed models containing additional dimensions. Brady developed a hierarchical and multidimensional model of perceived service quality by combining the ideas of earlier researchers. The relatively recent approaches like Brady’s (1997) utilize ideas seen in earlier models, yet more fully represent the complexity of the concept of service-quality perception.

American Marketing Association (1960). Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World. Chicago, IL: AMA.

Babakus, E., & Boller, G. W. (1992). An empirical assessment of the SERVQUAL scale. Journal of Business Reaearch, 24, 253-268.