- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

Steps in the literature review process.

- What is a literature review?

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- You may need to some exploratory searching of the literature to get a sense of scope, to determine whether you need to narrow or broaden your focus

- Identify databases that provide the most relevant sources, and identify relevant terms (controlled vocabularies) to add to your search strategy

- Finalize your research question

- Think about relevant dates, geographies (and languages), methods, and conflicting points of view

- Conduct searches in the published literature via the identified databases

- Check to see if this topic has been covered in other discipline's databases

- Examine the citations of on-point articles for keywords, authors, and previous research (via references) and cited reference searching.

- Save your search results in a citation management tool (such as Zotero, Mendeley or EndNote)

- De-duplicate your search results

- Make sure that you've found the seminal pieces -- they have been cited many times, and their work is considered foundational

- Check with your professor or a librarian to make sure your search has been comprehensive

- Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of individual sources and evaluate for bias, methodologies, and thoroughness

- Group your results in to an organizational structure that will support why your research needs to be done, or that provides the answer to your research question

- Develop your conclusions

- Are there gaps in the literature?

- Where has significant research taken place, and who has done it?

- Is there consensus or debate on this topic?

- Which methodological approaches work best?

- For example: Background, Current Practices, Critics and Proponents, Where/How this study will fit in

- Organize your citations and focus on your research question and pertinent studies

- Compile your bibliography

Note: The first four steps are the best points at which to contact a librarian. Your librarian can help you determine the best databases to use for your topic, assess scope, and formulate a search strategy.

Videos Tutorials about Literature Reviews

This 4.5 minute video from Academic Education Materials has a Creative Commons License and a British narrator.

Recommended Reading

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Literature Reviews: systematic searching at various levels

- for assignments

- for dissertations / theses

- Search strategy and searching

- Boolean Operators

- Search strategy template

- Screening & critiquing

- Citation Searching

- Google Scholar (with Lean Library)

- Resources for literature reviews

- Adding a referencing style to EndNote

- Exporting from different databases

PRISMA Flow Diagram

- Grey Literature

- What is the PRISMA Flow Diagram?

- How should I use it?

- When should I use it?

- PRISMA Links

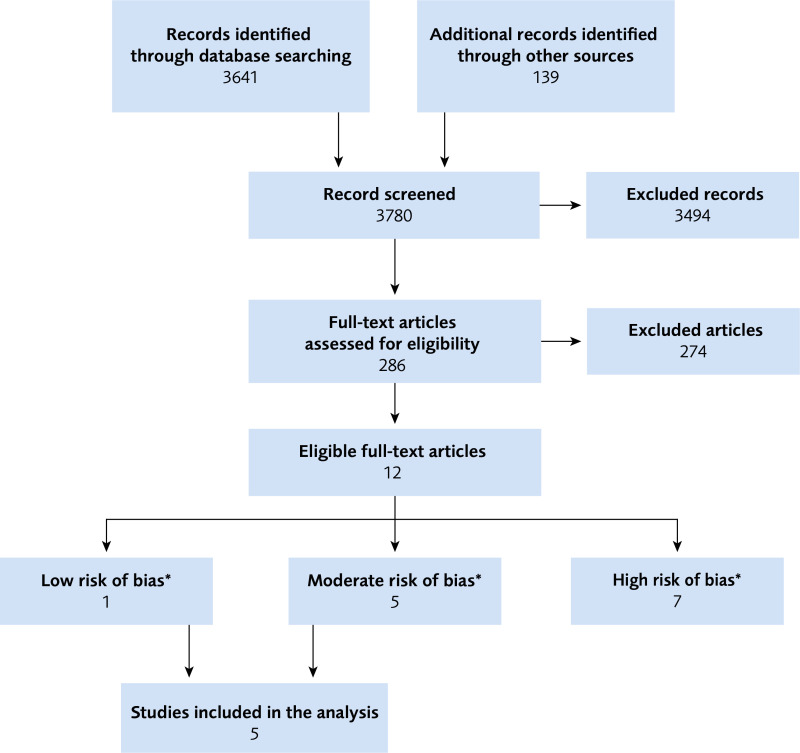

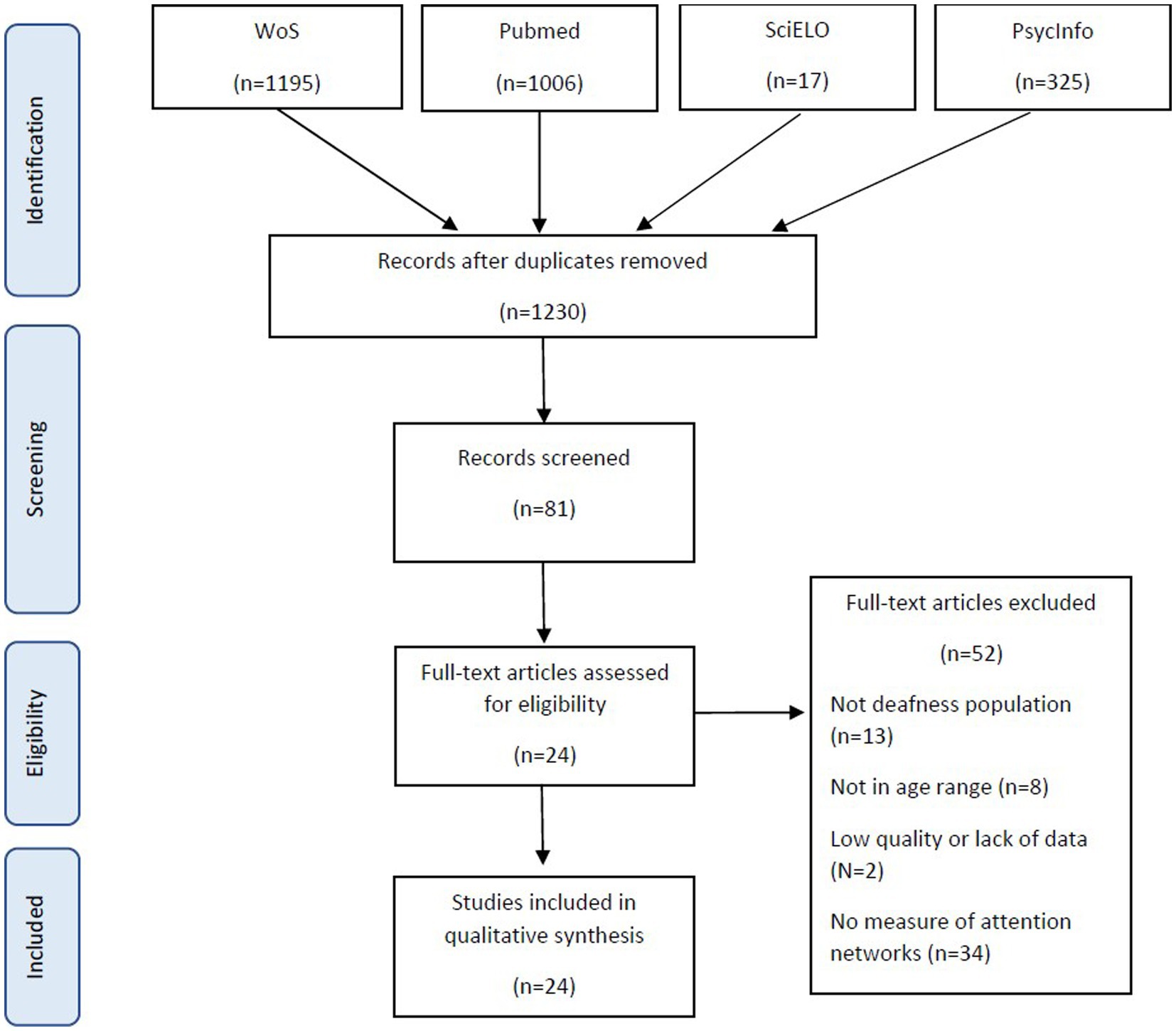

The PRISMA Flow Diagram is a tool that can be used to record different stages of the literature search process--across multiple resources--and clearly show how a researcher went from, 'These are the databases I searched for my terms', to, 'These are the papers I'm going to talk about'.

PRISMA is not inflexible; it can be modified to suit the research needs of different people and, indeed, if you did a Google images search for the flow diagram you would see many different versions of the diagram being used. It's a good idea to have a look at a couple of those examples, and also to have a look at a couple of the articles on the PRISMA website to see how it has--and can--be used.

The PRISMA 2020 Statement was published in 2021. It consists of a checklist and a flow diagram , and is intended to be accompanied by the PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration document.

In order to encourage dissemination of the PRISMA 2020 Statement, it has been published in several journals.

- How to use the PRISMA Flow Diagram for literature reviews A PDF [3.81MB] of the PowerPoint used to create the video. Each slide that has notes has a callout icon on the top right of the page which can be toggled on or off to make the notes visible.

There is also a PowerPoint version of the document but the file size is too large to upload here.

If you would like a copy, please email the Academic Librarians' mailbox from your university account to ask for it to be sent to you.

This is an example of how you could fill in the PRISMA flow diagram when conducting a new review. It is not a hard and fast rule but it should give you an idea of how you can use it.

For more detailed information, please have a look at this article:

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting,P. & Moher, D. (2021) 'The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews', BMJ 372:(71). doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 .

- Example of PRISMA 2020 diagram This is an example of *one* of the PRISMA 2020 flow diagrams you can use when reporting on your research process. There is more than one form that you can use so for other forms and advice please look at the PRISMA website for full details.

Start using the flow diagram as you start searching the databases you've decided upon.

Make sure that you record the number of results that you found per database (before removing any duplicates) as per the filled in example. You can also do a Google images search for the PRISMA flow diagram to see the different ways in which people have used them to express their search processes.

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PRISMA focuses on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials, but can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews of other types of research, particularly evaluations of interventions.

- Prisma Flow Diagram This link will take you to downloadable Word and PDF copies of the flow diagram. These are modifiable and act as a starting point for you to record the process you engaged in from first search to the papers you ultimately discuss in your work. more... less... Do an image search on the internet for the flow diagram and you will be able to see all the different ways that people have modified the diagram to suit their personal research needs.

You can access the various checklists via the Equator website and the articles explaining PRISMA and its various extensions are available via PubMed.

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., & Moher, D. (2021) ' The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews,' BMJ . Mar 29; 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 .

Page, M.J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., & McKenzie, J.E. (2021) 'PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews', BMJ, Mar 29; 372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160 .

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., & Moher, D. (2021) ' The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews,' Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, June; 134:178-189. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001 .

- << Previous: Exporting from different databases

- Next: Grey Literature >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 11:57 AM

- URL: https://libguides.derby.ac.uk/literature-reviews

How To Structure Your Literature Review

3 options to help structure your chapter.

By: Amy Rommelspacher (PhD) | Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | November 2020 (Updated May 2023)

Writing the literature review chapter can seem pretty daunting when you’re piecing together your dissertation or thesis. As we’ve discussed before , a good literature review needs to achieve a few very important objectives – it should:

- Demonstrate your knowledge of the research topic

- Identify the gaps in the literature and show how your research links to these

- Provide the foundation for your conceptual framework (if you have one)

- Inform your own methodology and research design

To achieve this, your literature review needs a well-thought-out structure . Get the structure of your literature review chapter wrong and you’ll struggle to achieve these objectives. Don’t worry though – in this post, we’ll look at how to structure your literature review for maximum impact (and marks!).

But wait – is this the right time?

Deciding on the structure of your literature review should come towards the end of the literature review process – after you have collected and digested the literature, but before you start writing the chapter.

In other words, you need to first develop a rich understanding of the literature before you even attempt to map out a structure. There’s no use trying to develop a structure before you’ve fully wrapped your head around the existing research.

Equally importantly, you need to have a structure in place before you start writing , or your literature review will most likely end up a rambling, disjointed mess.

Importantly, don’t feel that once you’ve defined a structure you can’t iterate on it. It’s perfectly natural to adjust as you engage in the writing process. As we’ve discussed before , writing is a way of developing your thinking, so it’s quite common for your thinking to change – and therefore, for your chapter structure to change – as you write.

Need a helping hand?

Like any other chapter in your thesis or dissertation, your literature review needs to have a clear, logical structure. At a minimum, it should have three essential components – an introduction , a body and a conclusion .

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

1: The Introduction Section

Just like any good introduction, the introduction section of your literature review should introduce the purpose and layout (organisation) of the chapter. In other words, your introduction needs to give the reader a taste of what’s to come, and how you’re going to lay that out. Essentially, you should provide the reader with a high-level roadmap of your chapter to give them a taste of the journey that lies ahead.

Here’s an example of the layout visualised in a literature review introduction:

Your introduction should also outline your topic (including any tricky terminology or jargon) and provide an explanation of the scope of your literature review – in other words, what you will and won’t be covering (the delimitations ). This helps ringfence your review and achieve a clear focus . The clearer and narrower your focus, the deeper you can dive into the topic (which is typically where the magic lies).

Depending on the nature of your project, you could also present your stance or point of view at this stage. In other words, after grappling with the literature you’ll have an opinion about what the trends and concerns are in the field as well as what’s lacking. The introduction section can then present these ideas so that it is clear to examiners that you’re aware of how your research connects with existing knowledge .

2: The Body Section

The body of your literature review is the centre of your work. This is where you’ll present, analyse, evaluate and synthesise the existing research. In other words, this is where you’re going to earn (or lose) the most marks. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think about how you will organise your discussion to present it in a clear way.

The body of your literature review should do just as the description of this chapter suggests. It should “review” the literature – in other words, identify, analyse, and synthesise it. So, when thinking about structuring your literature review, you need to think about which structural approach will provide the best “review” for your specific type of research and objectives (we’ll get to this shortly).

There are (broadly speaking) three options for organising your literature review.

Option 1: Chronological (according to date)

Organising the literature chronologically is one of the simplest ways to structure your literature review. You start with what was published first and work your way through the literature until you reach the work published most recently. Pretty straightforward.

The benefit of this option is that it makes it easy to discuss the developments and debates in the field as they emerged over time. Organising your literature chronologically also allows you to highlight how specific articles or pieces of work might have changed the course of the field – in other words, which research has had the most impact . Therefore, this approach is very useful when your research is aimed at understanding how the topic has unfolded over time and is often used by scholars in the field of history. That said, this approach can be utilised by anyone that wants to explore change over time .

For example , if a student of politics is investigating how the understanding of democracy has evolved over time, they could use the chronological approach to provide a narrative that demonstrates how this understanding has changed through the ages.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help you structure your literature review chronologically.

- What is the earliest literature published relating to this topic?

- How has the field changed over time? Why?

- What are the most recent discoveries/theories?

In some ways, chronology plays a part whichever way you decide to structure your literature review, because you will always, to a certain extent, be analysing how the literature has developed. However, with the chronological approach, the emphasis is very firmly on how the discussion has evolved over time , as opposed to how all the literature links together (which we’ll discuss next ).

Option 2: Thematic (grouped by theme)

The thematic approach to structuring a literature review means organising your literature by theme or category – for example, by independent variables (i.e. factors that have an impact on a specific outcome).

As you’ve been collecting and synthesising literature , you’ll likely have started seeing some themes or patterns emerging. You can then use these themes or patterns as a structure for your body discussion. The thematic approach is the most common approach and is useful for structuring literature reviews in most fields.

For example, if you were researching which factors contributed towards people trusting an organisation, you might find themes such as consumers’ perceptions of an organisation’s competence, benevolence and integrity. Structuring your literature review thematically would mean structuring your literature review’s body section to discuss each of these themes, one section at a time.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when structuring your literature review by themes:

- Are there any patterns that have come to light in the literature?

- What are the central themes and categories used by the researchers?

- Do I have enough evidence of these themes?

PS – you can see an example of a thematically structured literature review in our literature review sample walkthrough video here.

Option 3: Methodological

The methodological option is a way of structuring your literature review by the research methodologies used . In other words, organising your discussion based on the angle from which each piece of research was approached – for example, qualitative , quantitative or mixed methodologies.

Structuring your literature review by methodology can be useful if you are drawing research from a variety of disciplines and are critiquing different methodologies. The point of this approach is to question how existing research has been conducted, as opposed to what the conclusions and/or findings the research were.

For example, a sociologist might centre their research around critiquing specific fieldwork practices. Their literature review will then be a summary of the fieldwork methodologies used by different studies.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself when structuring your literature review according to methodology:

- Which methodologies have been utilised in this field?

- Which methodology is the most popular (and why)?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the various methodologies?

- How can the existing methodologies inform my own methodology?

3: The Conclusion Section

Once you’ve completed the body section of your literature review using one of the structural approaches we discussed above, you’ll need to “wrap up” your literature review and pull all the pieces together to set the direction for the rest of your dissertation or thesis.

The conclusion is where you’ll present the key findings of your literature review. In this section, you should emphasise the research that is especially important to your research questions and highlight the gaps that exist in the literature. Based on this, you need to make it clear what you will add to the literature – in other words, justify your own research by showing how it will help fill one or more of the gaps you just identified.

Last but not least, if it’s your intention to develop a conceptual framework for your dissertation or thesis, the conclusion section is a good place to present this.

Example: Thematically Structured Review

In the video below, we unpack a literature review chapter so that you can see an example of a thematically structure review in practice.

Let’s Recap

In this article, we’ve discussed how to structure your literature review for maximum impact. Here’s a quick recap of what you need to keep in mind when deciding on your literature review structure:

- Just like other chapters, your literature review needs a clear introduction , body and conclusion .

- The introduction section should provide an overview of what you will discuss in your literature review.

- The body section of your literature review can be organised by chronology , theme or methodology . The right structural approach depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your research.

- The conclusion section should draw together the key findings of your literature review and link them to your research questions.

If you’re ready to get started, be sure to download our free literature review template to fast-track your chapter outline.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

27 Comments

Great work. This is exactly what I was looking for and helps a lot together with your previous post on literature review. One last thing is missing: a link to a great literature chapter of an journal article (maybe with comments of the different sections in this review chapter). Do you know any great literature review chapters?

I agree with you Marin… A great piece

I agree with Marin. This would be quite helpful if you annotate a nicely structured literature from previously published research articles.

Awesome article for my research.

I thank you immensely for this wonderful guide

It is indeed thought and supportive work for the futurist researcher and students

Very educative and good time to get guide. Thank you

Great work, very insightful. Thank you.

Thanks for this wonderful presentation. My question is that do I put all the variables into a single conceptual framework or each hypothesis will have it own conceptual framework?

Thank you very much, very helpful

This is very educative and precise . Thank you very much for dropping this kind of write up .

Pheeww, so damn helpful, thank you for this informative piece.

I’m doing a research project topic ; stool analysis for parasitic worm (enteric) worm, how do I structure it, thanks.

comprehensive explanation. Help us by pasting the URL of some good “literature review” for better understanding.

great piece. thanks for the awesome explanation. it is really worth sharing. I have a little question, if anyone can help me out, which of the options in the body of literature can be best fit if you are writing an architectural thesis that deals with design?

I am doing a research on nanofluids how can l structure it?

Beautifully clear.nThank you!

Lucid! Thankyou!

Brilliant work, well understood, many thanks

I like how this was so clear with simple language 😊😊 thank you so much 😊 for these information 😊

Insightful. I was struggling to come up with a sensible literature review but this has been really helpful. Thank you!

You have given thought-provoking information about the review of the literature.

Thank you. It has made my own research better and to impart your work to students I teach

I learnt a lot from this teaching. It’s a great piece.

I am doing research on EFL teacher motivation for his/her job. How Can I structure it? Is there any detailed template, additional to this?

You are so cool! I do not think I’ve read through something like this before. So nice to find somebody with some genuine thoughts on this issue. Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This site is one thing that is required on the internet, someone with a little originality!

I’m asked to do conceptual, theoretical and empirical literature, and i just don’t know how to structure it

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Academic Process

- Systematic Reviews

- Step 8: Write the Review

Systematic Reviews: Step 8: Write the Review

Created by health science librarians.

- Step 1: Complete Pre-Review Tasks

- Step 2: Develop a Protocol

- Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches

- Step 4: Manage Citations

- Step 5: Screen Citations

- Step 6: Assess Quality of Included Studies

- Step 7: Extract Data from Included Studies

About Step 8: Write the Review

Write your review, report your review with prisma, review sections, plain language summaries for systematic reviews, writing the review- webinars.

- Writing the Review FAQs

Check our FAQ's

Email us

Call (919) 962-0800

Make an appointment with a librarian

Request a systematic or scoping review consultation

Search the FAQs

In Step 8, you will write an article or a paper about your systematic review. It will likely have five sections: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. You will:

- Review the reporting standards you will use, such as PRISMA.

- Gather your completed data tables and PRISMA chart.

- Write the Introduction to the topic and your study, Methods of your research, Results of your research, and Discussion of your results.

- Write an Abstract describing your study and a Conclusion summarizing your paper.

- Cite the studies included in your systematic review and any other articles you may have used in your paper.

- If you wish to publish your work, choose a target journal for your article.

The PRISMA Checklist will help you report the details of your systematic review. Your paper will also include a PRISMA chart that is an image of your research process.

Click an item below to see how it applies to Step 8: Write the Review.

Reporting your review with PRISMA

To write your review, you will need the data from your PRISMA flow diagram . Review the PRISMA checklist to see which items you should report in your methods section.

Managing your review with Covidence

When you screen in Covidence, it will record the numbers you need for your PRISMA flow diagram from duplicate removal through inclusion of studies. You may need to add additional information, such as the number of references from each database, citations you find through grey literature or other searching methods, or the number of studies found in your previous work if you are updating a systematic review.

How a librarian can help with Step 8

A librarian can advise you on the process of organizing and writing up your systematic review, including:

- Applying the PRISMA reporting templates and the level of detail to include for each element

- How to report a systematic review search strategy and your review methodology in the completed review

- How to use prior published reviews to guide you in organizing your manuscript

Reporting standards & guidelines

Be sure to reference reporting standards when writing your review. This helps ensure that you communicate essential components of your methods, results, and conclusions. There are a number of tools that can be used to ensure compliance with reporting guidelines. A few review-writing resources are listed below.

- Cochrane Handbook - Chapter 15: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - Chapter 12.3 The systematic review

- PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) The aim of the PRISMA Statement is to help authors improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Tools for writing your review

- RevMan (Cochrane Training)

- Methods Wizard (Systematic Review Accelerator) The Methods Wizard is part of the Systematic Review Accelerator created by Bond University and the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare.

- UNC HSL Systematic Review Manuscript Template Systematic review manuscript template(.doc) adapted from the PRISMA 2020 checklist. This document provides authors with template for writing about their systematic review. Each table contains a PRISMA checklist item that should be written about in that section, the matching PRISMA Item number, and a box where authors can indicate if an item has been completed. Once text has been added, delete any remaining instructions and the PRISMA checklist tables from the end of each section.

- The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews The PRISMA 2020 statement replaces the 2009 statement and includes new reporting guidance that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies.

- PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews This document is intended to enhance the use, understanding and dissemination of the PRISMA 2020 Statement. Through examples and explanations, the meaning and rationale for each checklist item are presented.

The PRISMA checklist

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) is a 27-item checklist used to improve transparency in systematic reviews. These items cover all aspects of the manuscript, including title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and funding. The PRISMA checklist can be downloaded in PDF or Word files.

- PRISMA 2020 Checklists Download the 2020 PRISMA Checklists in Word or PDF formats or download the expanded checklist (PDF).

The PRISMA flow diagram

The PRISMA Flow Diagram visually depicts the flow of studies through each phase of the review process. The PRISMA Flow Diagram can be downloaded in Word files.

- PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagrams The flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review. It maps out the number of records identified, included and excluded, and the reasons for exclusions. Different templates are available depending on the type of review (new or updated) and sources used to identify studies.

Documenting grey literature and/or hand searches

If you have also searched additional sources, such as professional organization websites, cited or citing references, etc., document your grey literature search using the flow diagram template version 1 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources or the version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources .

Complete the boxes documenting your database searches, Identification of studies via databases and registers, according to the PRISMA flow diagram instructions. Complete the boxes documenting your grey literature and/or hand searches on the right side of the template, Identification of studies via other methods, using the steps below.

Need help completing the PRISMA flow diagram?

There are different PRISMA flow diagram templates for new and updated reviews, as well as different templates for reviews with and without grey literature searches. Be sure you download the correct template to match your review methods, then follow the steps below for each portion of the diagram you have available.

View the step-by-step explanation of the PRISMA flow diagram

Step 1: Preparation Download the flow diagram template version 1 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only or the version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only .

View the step-by-step explanation of the grey literature & hand searching portion of the PRISMA flow diagram

Step 1: Preparation Download the flow diagram template version 1 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources or the version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources .

View the step-by-step explanation of review update portion of the PRISMA flow diagram

Step 1: Preparation Download the flow diagram template version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only or the version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources .

For more information about updating your systematic review, see the box Updating Your Review? on the Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches page of the guide.

Sections of a Scientific Manuscript

Scientific articles often follow the IMRaD format: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. You will also need a title and an abstract to summarize your research.

You can read more about scientific writing through the library guides below.

- Structure of Scholarly Articles & Peer Review • Explains the standard parts of a medical research article • Compares scholarly journals, professional trade journals, and magazines • Explains peer review and how to find peer reviewed articles and journals

- Writing in the Health Sciences (For Students and Instructors)

- Citing & Writing Tools & Guides Includes links to guides for popular citation managers such as EndNote, Sciwheel, Zotero; copyright basics; APA & AMA Style guides; Plagiarism & Citing Sources; Citing & Writing: How to Write Scientific Papers

Sections of a Systematic Review Manuscript

Systematic reviews follow the same structure as original research articles, but you will need to report on your search instead of on details like the participants or sampling. Sections of your manuscript are shown as bold headings in the PRISMA checklist.

Refer to the PRISMA checklist for more information.

Consider including a Plain Language Summary (PLS) when you publish your systematic review. Like an abstract, a PLS gives an overview of your study, but is specifically written and formatted to be easy for non-experts to understand.

Tips for writing a PLS:

- Use clear headings e.g. "why did we do this study?"; "what did we do?"; "what did we find?"

- Use active voice e.g. "we searched for articles in 5 databases instead of "5 databases were searched"

- Consider need-to-know vs. nice-to-know: what is most important for readers to understand about your study? Be sure to provide the most important points without misrepresenting your study or misleading the reader.

- Keep it short: Many journals recommend keeping your plain language summary less than 250 words.

- Check journal guidelines: Your journal may have specific guidelines about the format of your plain language summary and when you can publish it. Look at journal guidelines before submitting your article.

Learn more about Plain Language Summaries:

- Rosenberg, A., Baróniková, S., & Feighery, L. (2021). Open Pharma recommendations for plain language summaries of peer-reviewed medical journal publications. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 37(11), 2015–2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2021.1971185

- Lobban, D., Gardner, J., & Matheis, R. (2021). Plain language summaries of publications of company-sponsored medical research: what key questions do we need to address? Current Medical Research and Opinion, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2021.1997221

- Cochrane Community. (2022, March 21). Updated template and guidance for writing Plain Language Summaries in Cochrane Reviews now available. https://community.cochrane.org/news/updated-template-and-guidance-writing-plain-language-summaries-cochrane-reviews-now-available

- You can also look at our Health Literacy LibGuide: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/healthliteracy

How to Approach Writing a Background Section

What Makes a Good Discussion Section

Writing Up Risk of Bias

Developing Your Implications for Research Section

- << Previous: Step 7: Extract Data from Included Studies

- Next: FAQs >>

- Last Updated: May 14, 2024 12:50 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/systematic-reviews

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

- PRISMA flow diagram generator

Resource link

- PRISMA flow diagram templates

This tool, developed by PRISMA, can be used to develop a PRISMA flow diagram in order to report on systematic reviews.

The flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review. It maps out the number of records identified, included and excluded, and the reasons for exclusions.

The aim of the PRISMA Statement is to help authors report a wide array of systematic reviews to assess the benefits and harms of a health care intervention. PRISMA focuses on ways in which authors can ensure the transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

We have adopted the definitions of systematic review and meta-analysis used by the Cochrane Collaboration [9]. A systematic review is a review of a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Statistical methods (meta-analysis) may or may not be used to analyse and summarise the results of the included studies. Meta-analysis refers to the use of statistical techniques in a systematic review to integrate the results of included studies.

PRISMA (n.d.). PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator . Retrieved from: https://estech.shinyapps.io/prisma_flowdiagram/

PRISMA (n.d.). PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator . Retrieved from: http://prisma-statement.org/PRISMAStatement/

'PRISMA flow diagram generator' is referenced in:

- Systematic review

Back to top

© 2022 BetterEvaluation. All right reserved.

- Open access

- Published: 19 April 2021

How to properly use the PRISMA Statement

- Rafael Sarkis-Onofre 1 ,

- Ferrán Catalá-López 2 , 3 ,

- Edoardo Aromataris 4 &

- Craig Lockwood 4

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 117 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

70k Accesses

188 Citations

103 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Research to this article was published on 29 March 2021

It has been more than a decade since the original publication of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [ 1 ], and it has become one of the most cited reporting guidelines in biomedical literature [ 2 , 3 ]. Since its publication, multiple extensions of the PRISMA Statement have been published concomitant with the advancement of knowledge synthesis methods [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The PRISMA2020 statement, an updated version has recently been published [ 8 ], and other extensions are currently in development [ 9 ].

The number of systematic reviews (SRs) has increased substantially over the past 20 years [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. However, many SRs continue to be poorly conducted and reported [ 10 , 11 ], and it is still common to see articles that use the PRISMA Statement and other reporting guidelines inappropriately, as was highlighted recently [ 13 ].

The PRISMA Statement and its extensions are an evidence-based, minimum set of recommendations designed primarily to encourage transparent and complete reporting of SRs. This growing set of guidelines have been developed to aid authors with appropriate reporting of different knowledge synthesis methods (such as SRs, scoping reviews, and review protocols) and to ensure that all aspects of this type of research are accurately and transparently reported. In other words, the PRISMA Statement is a road map to help authors best describe what was done, what was found, and in the case of a review protocol, what are they are planning to do.

Despite this clear and well-articulated intention [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ], it is common for Systematic Reviews to receive manuscripts detailing the inappropriate use of the PRISMA Statement and its extensions. Most frequently, improper use appears with authors attempting to use the PRISMA statement as a methodological guideline for the design and conduct reviews, or identifying the PRISMA statement as a tool to assess the methodological quality of reviews, as seen in the following examples:

“This scoping review will be conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Statement.”

“This protocol was designed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) Statement.”

“The methodological quality of the included systematic reviews will be assessed with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.”

Some organizations (such as Cochrane and JBI) have developed methodological guidelines that can help authors to design or conduct diverse types of knowledge synthesis rigorously [ 14 , 15 ]. While the PRISMA statement is presented to predominantly guide reporting of a systematic review of interventions with meta-analyses, its detailed criteria can readily be applied to the majority of review types [ 13 ]. Differences between the role of the PRISMA Statement to guide reporting versus guidelines detailing methodological conduct is readily illustrated with the following example: the PRISMA Statement recommends that authors report their complete search strategies for all databases, registers, and websites (including any filters and limits used), but it does not include recommendations for designing and conducting literature searches [ 8 ]. If authors are interested in understanding how to create search strategies or which databases to include, they should refer to the methodological guidelines [ 12 , 13 ]. Thus, the following examples can illustrate the appropriate use of the PRISMA Statement in research reporting:

“The reporting of this systematic review was guided by the standards of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement.”

“This scoping review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).”

“The protocol is being reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) Statement.”

Systematic Reviews supports the complete and transparent reporting of research. The Editors require the submission of a populated checklist from the relevant reporting guidelines, including the PRISMA checklist or the most appropriate PRISMA extension. Using the PRISMA statement and its extensions to write protocols or the completed review report, and completing the PRISMA checklists are likely to let reviewers and readers know what authors did and found, but also to optimize the quality of reporting and make the peer review process more efficient.

Transparent and complete reporting is an essential component of “good research”; it allows readers to judge key issues regarding the conduct of research and its trustworthiness and is also critical to establish a study’s replicability.

With the release of a major update to PRISMA in 2021, the appropriate use of the updated PRISMA Statement (and its extensions as those updates progress) will be an essential requirement for review based submissions, and we encourage authors, peer reviewers, and readers of Systematic Reviews to use and disseminate that initiative.

Availability of data and materials

We do not have any additional data or materials to share.

Abbreviations

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols

Systematic reviews

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Caulley L, Cheng W, Catala-Lopez F, Whelan J, Khoury M, Ferraro J, et al. Citation impact was highly variable for reporting guidelines of health research: a citation analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;127:96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.07.013 .

Page MJ, Moher D. Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement and extensions: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0663-8 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z .

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850 .

Article Google Scholar

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 .

Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777–84. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2385 .

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. https://doi/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4.

EQUATOR Network: Reporting guidelines under development for systematic reviews. https://www.equator-network.org/library/reporting-guidelines-under-development/reporting-guidelines-under-development-for-systematic-reviews/ . Accessed 11 Feb 2021.

Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Sampson M, Tricco AC, et al. Epidemiology and Reporting Characteristics of Systematic Reviews of Biomedical Research: A Cross-Sectional Study. Plos Med. 2016;13(5):e1002028. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002028 .

Ioannidis JP. The Mass Production of Redundant, Misleading, and Conflicted Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 2016;94(3):485–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12210 .

Niforatos JD, Weaver M, Johansen ME. Assessment of Publication Trends of Systematic Reviews and Randomized Clinical Trials, 1995 to 2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1593–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3013.

Caulley L, Catala-Lopez F, Whelan J, Khoury M, Ferraro J, Cheng W, et al. Reporting guidelines of health research studies are frequently used inappropriately. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;122:87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.03.006 .

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2019.

Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. ed. Adelaide: JBI; 2020.

Download references

Acknowledgements

RSO is funded in part by Meridional Foundation. FCL is funded in part by the Institute of Health Carlos III/CIBERSAM.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Graduate Program in Dentistry, Meridional Faculty, IMED, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Rafael Sarkis-Onofre

Department of Health Planning and Economics, National School of Public Health, Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain

Ferrán Catalá-López

Department of Medicine, University of Valencia/INCLIVA Health Research Institute and CIBERSAM, Valencia, Spain

JBI, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia

Edoardo Aromataris & Craig Lockwood

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RSO drafted the initial version. FCL, EA, and CL made substantial additions to the first and subsequent drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rafael Sarkis-Onofre .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

CL is Editor-in-Chief of Systematic Reviews, FCL is Protocol Editor of Systematic Reviews, and RSO is Associate Editor of Systematic Reviews.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sarkis-Onofre, R., Catalá-López, F., Aromataris, E. et al. How to properly use the PRISMA Statement. Syst Rev 10 , 117 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01671-z

Download citation

Published : 19 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01671-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

Evidence synthesis & literature reviews education, what do you want to learn about, selected training, review types, evidence synthesis process, selected protocols, guidelines, & tools.

Training for Getting Started

This module series helps users gain a more in-depth understanding of the process of conducting a systematic review. Make sure you are connected to the VPN before registering for a free account.

This series covers the fundamental concepts and general procedure of searching the health science literature to ensure your search is comprehensive, methodical, transparent and reproducible.

Need more help?

Fill out our form to get personalized advice about review methodologies appropriate for your project.

Our librarians have co-authored hundreds of evidence synthesis articles. Our staff is continually trained on new search methodologies and processes.

We adhere to the requirements for authorship and contributorship of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE).

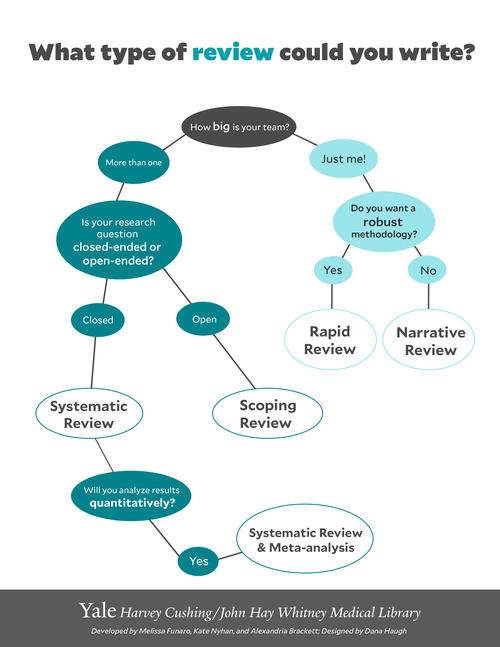

Title: "What type of Review Could You Write"

Top of chart begins Q: "How big is your team?"

- If "Yes" to robust methodology, then "Rapid Review"

- If "No to robust methodology, then "Narrative Review"

- If "Yes", then "Systematic Review and Meta-analysis"

- If "Open", then "Scoping Review"

Build your evidence synthesis team [preparation stage]

Review reporting guidelines, best practice handbooks, and training modules [preparation stage]

Formulate question and decide on review type [preparation stage]

Search for previous published literature and protocols [preparation stage]

Develop and register a protocol [write-up stage]

Develop and test search strategies [preparation stage]

Peer review of search strategies [preparation stage]

Execute search [retrieval stage]

De-duplicate results [retrieval stage]

Screen title and abstracts [screening stage]

Retrieve full-text articles [retrieval stage]

Screen articles in full-text [screening stage]

Search for grey literature [retrieval stage]

Quality assessment and data extraction [synthesis stage]

Citation chasing [retrieval stage]

Update database searches [retrieval stage]

Synthesize data [synthesis stage]

Manuscript development [write-up stage]

View this process as a graphic

Protocols & Reporting Guidelines

- PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses)

- MOOSE (Meta-analyisis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)

- ENTREQ (Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research)

Protocol Registries

- PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews)

- Open Science Framework: Registries

Quality Assessment Instruments

- CATevaluation : a listing of Critical Appraisal Tools assessed for validity and/or reliability

- GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Checklist

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools

- Risk of bias tools in systematic reviews of health interventions: an analysis of PROSPERO-registered protocols (article)

- Critical appraisal of nonrandomized studies: a review of recommended and commonly used tools (article)

Best Practices

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions

- CRDs Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care

- JBI Best Practices (Joanna Briggs Institute)

- MECIR (Methodological Expectations for Cochrane Intervention Reviews)

- Publications on systematic review / evidence synthesis methodology (EPPI-Centre)

- Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality)

- Yale MeSH Analyzer - helps identify the problems in your search strategy

- Covidence - manage bibliographic data, PDFs, forms for risk of bias, and data extraction

- EndNote - citation management software

- What Review Is Right For You? Interactive Edition - guidance for conducting and reporting evidence synthesis

- An Introduction to Systematic Reviews edited by David Gough, Sandy Oliver, James Thomas

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis by Jacqueline Corcoran; Vijayan Pillai; Julia H. Littell

- The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis edited by Harris Cooper, Larry V. Hedges, Jeffrey C. Valentine

- Searching the Grey Literature: A handbook for Searching Reports, Working Papers, and other Unpublished Research by Sarah Bonato

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.