Was the US Justified in Dropping the Atomic Bomb? Essay

Introduction, works cited.

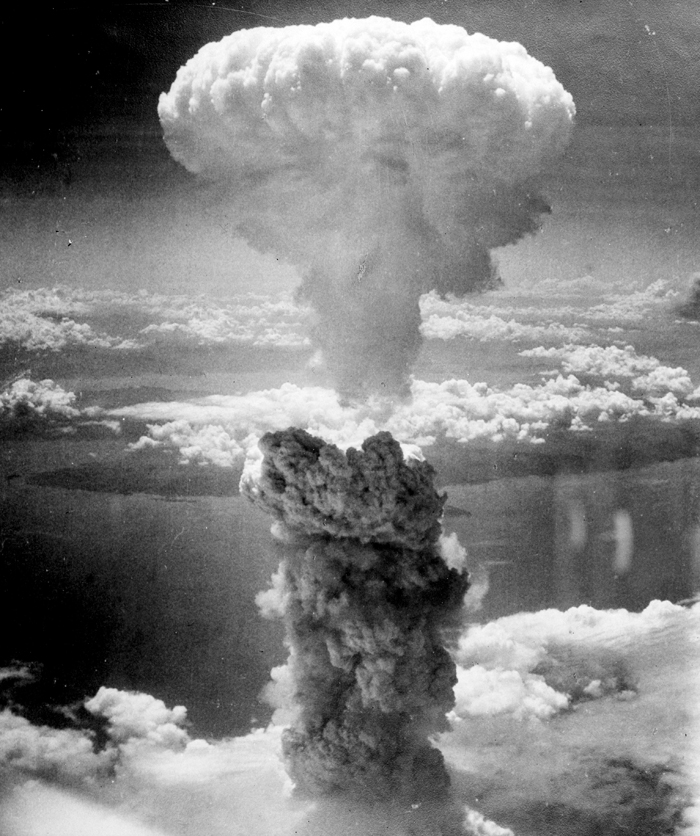

The United States is widely recognized for ending World War II by dropping atomic bombs on two cities in Japan; however, they also caused incalculable human anguish difficult to justify. This action introduced new concerns and conceptions regarding how wars would be fought in the future, called into question whether the human race would survive much into the future and began a worldwide debate regarding whether the action was truly warranted.

Questions regarding the bombings are multifaceted. While it is often suggested that the atomic bomb was the only means available to secure Japanese surrender, Japan at the time was requesting only one concession from the West – that it be allowed to retain its emperor as head of state. Had this been done, could the wanton destruction of a predominantly civilian population be avoided? Considering this, it is necessary to question the true motivations of President Truman in his authorization of the bombs’ use. Was it actually to bring about a swift end to the protracted deadly conflict and ultimately intended to save lives, American and Japanese, that would be lost in an overland confrontation? Or was it, as has been suggested, more a decision based on keeping the Soviet Union from having any input regarding the division of post-war Asia as it had in dividing post-war Europe? Even if the first bomb, dropped on Hiroshima could be argued as justifiable, the widespread destruction and collateral damage was devastating enough that the second bomb, dropped on Nagasaki, should have been called back.

The primary reasoning given for the bombs’ use was that it would save thousands of American and Japanese lives by eliminating the need for an overland confrontation between the two opposing armies. While the battles for the Philippines and Okinawa were taking place, President Truman, who had become president following the death of Roosevelt, was considering an invasion of the Japanese mainland. By now, the U.S. Navy had ships stationed just off the Japanese coast while its submarines were deployed in the Sea of Japan. Because the battles at Iwo Jima and Okinawa were very fierce, it was estimated that half a million to a million soldiers would be killed if the scheduled November 1, 1945 invasion of Japan occurred (“Decision to Drop”, 2003). However, what fails to enter the discussion is the comparison of the types of victims involved – enlisted men or civilians. The first blast leveled more than half of Hiroshima. Seventy thousand of its citizens were instantaneously killed.

On August 9, another bomb destroyed Nagasaki (Truman, 1945). Deliberately attacking a civilian population is not considered morally acceptable regardless of any real or perceived outcomes. This view was and remains popularly held by both American civilians and the military. Even for those individuals who do not find it difficult to accept that the first bomb was necessary, though, the issue regarding the morality of the second bombing remains in dispute. The saving of lives was not at issue by the time the second bomb was dropped.

In addition to considering the overland attack, President Truman and his staff realized that if the Japanese would surrender prior to Soviet involvement in the Asian field, set for August 15, Russia could not demand a part in the post-war settlement. At the same time, by 1945, the U.S. was a country weary of war and its citizens had become deeply prejudiced against both the Japanese and Germans, believing that both types of peoples were inherently evil. Following the end of the war, a poll conducted by Fortune Magazine found that nearly a quarter of the American people thought that the U.S. should have used “many more” atomic bombs on the Japanese before that country had the opportunity to surrender (Dower, 1986: 54). These polling results accurately reflected the intense hatred that Americans directed towards the Japanese people during the conflict. President Truman himself was not immune to these feelings of resentment towards the Japanese. In July 1945, less than a week prior to the Hiroshima bombing, Truman wrote in his diary describing the Japanese people as “savages, ruthless, merciless, and fanatic” (Dower, 1986: 142). When America unleashed the atomic bomb on Japan, the act infuriated the Soviet Union because it wanted its say just as it had in the carving up of Eastern Europe.

In addition to unleashing catastrophic damage upon the people of Japan, the dropping of the bombs was the beginning of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the U.S.

Although Truman shared a similar bias against the Japanese as did the American public, his intent was not to drop such a devastating bomb on civilian areas. “We have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world.

I have told the Secretary of War, Mr. [Henry] Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. The target will be a purely military one” (Truman, 1945). Both Hiroshima and Nagasaki were cities that produced military armaments but, of course, the devastation went well beyond military targets. It could be that the President and others did not realize the full power of the atomic bomb or simply did not care if the collateral damage went well beyond its intended target. No one will ever know and the answer can only be speculative. It is contingent on whether one relies on the written words of the President as proof of actual intent or one assumes that the bombing of civilians was justified by the President and/or Stimson given the excessively racist overtones that emanated throughout the country at that time. In addition to whatever personal feelings Truman had regarding the Japanese, he also had political consequences to consider in his decision to utilize the atomic bomb. The American public, according to polls taken at that time, supported by an overwhelming margin that the U.S. should only agree to an ‘unconditional surrender’ by Japan. This and the predominant anti-Japanese sentiment among most Americans assured that there would be little political backlash by ordering the bomb to be dropped.

Furthermore, Truman would have faced an uphill political battle attempting to explain to voters the reasoning for spending more than two billion dollars for creating a bomb that would not be used, particularly if many more American lives were lost had the war continued which, at the time was considered a very real possibility (Loebs, 1995: 8-9).

Also supporting the decision, the Japanese had amassed nine divisions comprised of 600,000 heavily equipped forces in southern Japan prior to the bombing of Hiroshima in preparation for a land attack. The speed at which this incredible number of troops and arms were assimilated deeply concerned Truman and the U.S. military who had previously expected far less resistance when planning Operation Olympic, the Japanese invasion force (Loebs, 1995). Surprised once by the continued determination and ability of the Japanese military, Truman did not want to be surprised yet again by an even larger resistance than was thought which the allies could encounter as it drove further north towards Tokyo. Truman considered the possibility that he could send many thousands of young Americans to their deaths in a final conflict that may not be winnable at all and could easily stretch out for many months or years. The Japanese not only had a large number of soldiers ready to defend their homeland, but they were also well-equipped and possessed strong supply lines so as to sustain a long-term attack. One can only imagine the carnage that would have ensued during a full-out battle of this magnitude had it occurred. The ferocious battles of Okinawa and Iwo Jima would have seemed as just a warm-up compared to a Japanese invasion.

Despite all these justifications, by the summer of 1945, the Japanese were in dire straits, militarily and economically. The U.S. had won great victories at Okinawa and Iwo Jima, killed hundreds of thousands of Japanese soldiers and had a full naval blockade of Japan’s mainland.

Shortages of everything, from oil for the machines to food supplies for the soldiers, had all but brought the Japanese empire to its knees, but its military showed no signs of quitting. In each battle, its soldiers fought ferociously to the last man in a victory or death mentality and suicide (kamikaze) missions were common. This led the American leaders to believe that an entire takeover of the Japanese island was necessary for final victory. The U.S. was well aware of the fanaticism displayed by the Japanese; therefore, military leaders were not anxious to encounter an entire population of a country that possessed this mentality and were militarized as well. The avoidance of this ensuing confrontation and the war-weariness of the American public is the common justifications for dropping the bombs. Finally, “it was the destruction of Hiroshima that finally brought Emperor Hirohito to confront the Japanese military and order the surrender of Japan” (Loebs, 1995: 10). Thus, it was and is argued that the atomic bombs ultimately saved many American and Japanese lives.

It has been argued that the decision to drop the atomic bomb actually gave little regard to the civilian population, was unnecessary and was based largely upon the Soviet’s aspirations in the region. The U.S. military had been unceasingly fire-bombing major cities in Japan including Tokyo for months leading up to the use of the atomic bomb. This massive bombing attack knowingly killed civilians by the hundreds of thousands and the tactic, along with the impenetrable naval blockade, would have eventually brought the war to an end without the need for a land assault. Of course this eventuality can only be argued because it can never be known if maintaining an attack with traditional bombing methods and a blockade of the seas would have forced the Japanese to surrender unconditionally. It is possible but many more Japanese civilians, probably numbering in the millions, would have been killed in the process. In addition, had the war been prolonged, the threat posed by the Soviets was imminent and daunting. Had they had a hand in postwar affairs in Asia, the boundaries of the world would be very different today. The Russian army had entered Korea a few days prior to August 6; the day of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima (Zimmerman, 2000). Within a short time, it would have conquered enough Korean territory to be able to claim a negotiating position at the post-war peace talks. Had this scenario occurred, the Soviets had plans in place to occupy both Japan and Korea to the familiar 38th parallel.

This would have been an offer the Allies couldn’t refuse because Soviet troops would already be occupying this territory. “The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki served three purposes: it terminated the conflict instantly, saving American lives; it insured a united Japan rather than leaving half of the country to the same fate as North Korea; and perhaps it provided an example which has deterred the use of nuclear arms for 55 years” (Zimmerman, 2000).

More than 60 years have elapsed since the atomic bomb was dropped, a long time to second guess and point out the flawed reasoning in that momentous decision. However, many prominent However, Americans at that time questioned the wisdom of using such a horrific weapon given the circumstances.

Top-level World War II military leaders such as Douglas MacArthur, William Halsey, William Leahy and Dwight Eisenhower amongst others, believed the bomb to be totally unnecessary from a military point of view (Takaki, 1995: 3-4, 30-31). The President of the Chiefs of Staff, Navy Admiral Leahy, in his address to the combined U.K. and U.S. Chiefs of Staff expressed his thoughts regarding the use of the atomic bomb. “The use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender. In being the first to use it, we adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages.

I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children” (Alperovitz, 2005: 3). In 1946, the Commander U.S. Third Fleet, Admiral Halsey Commander publicly announced that “The first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment. It was a mistake to ever drop it. The scientists had this toy and they wanted to try it out, so they dropped it” (Alperovitz, 2005: 331). The Supreme Commander of the Pacific Fleet in World War II, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz stated at an address given on October 5 at the Washington Monument, “The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace before the atomic age was announced to the world with the destruction of Hiroshima and before the Russian entry into the war. The atomic bomb played no decisive part, from a purely military standpoint, in the defeat of Japan” (Alperovitz, 2005: 329). Eisenhower was of the same opinion as to these other prominent commanders and vocally joined his colleges citing morality-based objections.

Japan was very close to surrendering by the time the atomic bombs were dropped on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Sixty of its larger cities had already been destroyed by the use of conventional bombing runs and the naval blockade had destroyed Japan’s economy. The Soviet Union was busy fighting the Japanese, but these battles were fought in China and were far from a mainland invasion as Russia had also been weakened following its war with Germany. If the U.S. would have allowed the Japanese to retain its Emperor, the country would have surrendered before the first bomb was dropped, a slight concession given the devastating consequences. A demonstration bombing in a remote area of Japan would have been sufficient to affect surrender without using it on a civilian population. The second bomb was entirely unnecessary even if the first could be justified. Simply put, the Japanese people were pawns used in a political power play, the first such power plays of the ‘Cold War’ between the U.S. and Soviet Union.

Alperovitz, Gar. “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb.” (1st Ed.). New York: Routledge. (2005).

“(The) Decision to Drop.” National Atomic Museum. (2003). Web.

Dower, John W. “War Without Mercy.” New York: Pantheon Books. (1986).

Loebs, Bruce. “Hiroshima & Nagasaki: One Necessary Evil, One Tragic Mistake.” Commonweal Journal. LookSmart Articles. (1995). Web.

Takaki, Ronald. “Hiroshima: Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb.” Boston: Little, Brown and Company. (1995).

Truman, Harry. “Atomic Bomb – Truman Press Release: August 6, 1945.” Truman Presidential Museum and Library. (1945). Web.

Zimmerman, Peter D. “The Atomic Bomb.” St. Petersburg Times. (2000). Web.

- Rights of Prisoners of War in the Geneva Convention

- Hiroshima and Its Importance in US History

- The Use of Atomic Bomb in Japan: Causes and Consequences

- Was the American Use of the Atomic Bomb Against Japan in 1945 the Final Act of WW2 or the Signal That the Cold War Was About to Begin

- Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Long-Term Health Effects

- The Neylam Plan Article. Critique of the Article.

- Pearl Harbor: A Look at the Historical Accuracy

- The Holocaust: Historical Analysis

- Air Power in the Pacific Air War of 1941-1945

- Shifting Images of Chinese Americans During World War II

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, September 21). Was the US Justified in Dropping the Atomic Bomb? https://ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-us-justified-in-dropping-the-atomic-bomb/

"Was the US Justified in Dropping the Atomic Bomb?" IvyPanda , 21 Sept. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-us-justified-in-dropping-the-atomic-bomb/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Was the US Justified in Dropping the Atomic Bomb'. 21 September.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Was the US Justified in Dropping the Atomic Bomb?" September 21, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-us-justified-in-dropping-the-atomic-bomb/.

1. IvyPanda . "Was the US Justified in Dropping the Atomic Bomb?" September 21, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-us-justified-in-dropping-the-atomic-bomb/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Was the US Justified in Dropping the Atomic Bomb?" September 21, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-us-justified-in-dropping-the-atomic-bomb/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

National Museum of Nuclear Science & History

Debate over the Bomb: An Annotated Bibliography

- Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

More than seventy years after the end of World War II, the decision to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki remains controversial . Historians and the public continue to debate if the bombings were justified, the causes of Japan’s surrender, the casualties that would have resulted if the U.S. had invaded Japan, and more. Some historians, often called “traditionalists,” tend to argue that the bombs were necessary in order to save American lives and prevent an invasion of Japan. Other experts, usually called “revisionists,” claim that the bombs were unnecessary and were dropped for other reasons, such as to intimidate the Soviet Union. Many historians have taken positions between these two poles. These books and articles provide a range of perspectives on the atomic bombings. This is not an exhaustive list, but should illustrate some of the different arguments over the decision to use the bombs.

Bibliography on the Debate over the Bomb

- Alperovitz, Gar. Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965.

——-. The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth . New York: Knopf, 1995.

Alperovitz, a prominent revisionist historian, argues that the bombs were unnecessary to force Japan’s surrender. In particular, he posits that the Japanese were already close to surrender and that bombs were primarily intended as a political and diplomatic weapon against the Soviet Union.

- Bernstein, Barton. “Understanding the Atomic Bomb and the Japanese Surrender: Missed Opportunities, Little-Known Near Disasters, and Modern Memory.” Diplomatic History 19 (Spring 1995): 227-73.

Bernstein challenges the notions that the Japanese were ready to surrender before Hiroshima and that the atomic bombings were primarily intended to intimidate the Soviet Union. He also questions traditionalist claims that the U.S. faced a choice between dropping the bomb and an invasion, and that an invasion would lead to hundreds of thousands of American casualties.

- Bird, Kai, and Lawrence Lifschultz, eds. Hiroshima’s Shadow: Writings on the Denial of History and the Smithsonian Controversy . Stony Creek, CT: Pamphleteer’s Press, 1998.

This collection of essays and primary source documents, written primarily from a revisionist perspective, provides numerous critiques of the use of the atomic bombs. It includes a foreword by physicist Joseph Rotblat , who left the Manhattan Project in 1944 on grounds of conscience.

- Bix, Herbert P. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan . New York: Perennial, 2000.

This Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of the Japanese emperor asserts that the Japanese did not decide to surrender until after the bombings and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria. Bix attributes responsibility for the bombings to Hirohito’s “power, authority, and stubborn personality” and President Truman’s “power, determination, and truculence.”

- Craig, Campbell and Radchenko, Sergey. The Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

A provocative study of the entrance of the atomic bomb onto the global stage. It questions the various influences impacting the United States’ decision to drop the bomb, and discusses the Manhattan Project’s role in orchestrating the bipolar conflict of the Cold War.

- Dower, John W. Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor/Hiroshima/9-11/Iraq . New York: W. W. Norton, 2010.

Dower states that the U.S. used the bombs in order to end the war and save American lives, but asserts that Truman could have waited a few weeks before dropping the bombs to see if the Soviet invasion of Manchuria would compel Japan to surrender. He argues that Truman employed “power politics” in order to keep the Soviet Union in check, and criticizes both Japanese and American leaders for their inability to make peace.

- Feis, Herbert. Between War and Peace: The Potsdam Conference . Princeton, NJ: Princton University Press, 1960.

Feis presents a blow-by-blow account of the proceedings at the Potsdam Conference that sought to plan the postwar world. He gives particular attention to the discussion of atomic weapons that took place at the conference, noting how it impacted the negotiations of Harry Truman and the American delegation.

- Frank, Richard B. Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire . New York: Penguin Books, 1999.

Frank contends that the Japanese were not close to surrendering before the bombing of Hiroshima. He also concludes that 33,000-39,000 American soldiers would have been killed in an invasion, much lower than the figures usually given by traditionalists.

- Fussell, Paul. Thank God for the Atom Bomb and Other Essays . New York: Summit Books, 1988.

In the title essay, Fussell, a World War II veteran, vividly recalls the war’s brutality and defends the bombings as a tragic necessity.

- Giangreco, D.M. Hell to Pay: Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan, 1945-1947 . Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2009.

Giangreco defends estimates that an invasion of Japan would have cost hundreds of thousands of American lives, and challenges the argument that using the bombs was unjustified.

- Gordin, Michael D. Five Days in August: How World War II Became a Nuclear War . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Gordin argues that Hiroshima and Nagasaki stemmed from American decisionmakers’ belief that the bombs were merely an especially powerful conventional weapon. He claims U.S. leaders did not “clearly understand the atomic bomb’s revolutionary strategic potential.”

- Ham, Paul. Hiroshima Nagasaki: The Real Story of the Atomic Bombings and Their Aftermath . Basingstoke, UK: Picador, 2015.

Ham demonstrates that misunderstandings and nationalist fury from both Allied and Axis powers led to the use of the atomic bombs. Ham also gives powerful witness to its destruction through the eyes of eighty survivors, from twelve-year-olds forced to work in war factories to wives and children who faced the holocaust alone.

- Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman and the Surrender of Japan . Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005.

In this history of the end of World War II from American, Japanese, and Soviet perspectives, Hasegawa determines that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria was the primary factor in compelling the Japanese to surrender.

- Hersey, John. Hiroshima . New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1946.

Hersey’s book-length article, which appeared in the New Yorker one year after the bombing of Hiroshima, profiles six survivors of the attack. It helped give the American public a new picture of the human impact of the bomb and brought about a groundswell of negative opinion against nuclear weapons.

- Lifton, Robert Jay, and Greg Mitchell. Hiroshima in America: A Half Century of Denial . New York: Avon Books, 1995.

Written from a revisionist perspective, this book assesses President Truman’s motivations for authorizing the atomic bombings and traces the effects of the bombings on American society.

- Maddox, Robert James. Weapons for Victory: The Hiroshima Decision Fifty Years Later . Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1995.

This analysis contends that Japan had not decided to surrender before Hiroshima, states that the U.S. did not believe the Soviet invasion would force Japan to surrender, and challenges the idea that American officials greatly exaggerated the costs of a U.S. invasion of mainland Japan.

- Malloy, Sean. Atomic Tragedy: Henry L. Stimson and the Decision to Use the Bomb Against Japan . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Traces the U.S. government’s decision to drop the atomic bombs on Japan, using the life of Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson as a lens. This biography frames the contested decision as a moral question faced by American policy makers.

- Miscamble, Wilson D. The Most Controversial Decision: Truman, the Atomic Bombs, and the Defeat of Japan . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

In this short history, Miscamble critiques various revisionist arguments and posits that the bomb was militarily necessary. He also discusses whether the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were morally justified.

- Newman, Robert P. Truman and the Hiroshima Cult . East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1995.

Newman argues that Truman made a legitimate military decision to bring the war to an end as quickly as possible. He claims the bombings ultimately saved lives and assails what he calls a “cult” of victimhood surrounding the attacks.

- Rotter, Andrew J. Hiroshima: The World’s Bomb . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

This international history of the race to develop the bomb asserts that Truman was primarily motivated by a desire to end the war as quickly as possible, with a minimal loss of American lives. Rotter states that the shocks caused by the atomic bombings and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria were both pivotal to Japan’s surrender.

- Stimson, Henry L. “ The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb .” Harper’s Magazine 194:1167 (February 1947): 97-107.

Writing a year and a half after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, former Secretary of War Stimson defends the U.S. decision. He documents the refusal of the Japanese to surrender and estimates that an Allied invasion would have resulted in one million American casualties and many more Japanese deaths.

- Walker, J. Samuel. Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

In a concise critique of both traditionalist and revisionist interpretations of Truman’s decision, Walker concludes that the primary motivation for the use of the bombs was to end World War II as quickly as possible.

- Zeiler, Thomas W. Unconditional Defeat: Japan, America, and the End of World War II . Wilmington, DE: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

This history chronicles the brutality of the fighting between the U.S. and Japan in the Pacific. Zeiler concludes that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were mostly motivated by military, rather than political, reasons.

If you have suggestions for resources that should be listed here, please contact us .

Truman announces Japanese surrender.

Hiroshima Atomic Dome Memorial. Photo by Dmitrij Rodionov, Wikimedia Commons.

Nagasaki, October 1945

Paul Tibbets and the Enola Gay. Courtesy of the Joseph Papalia Collection.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Atomic Bomb History

By: History.com Editors

Updated: November 9, 2022 | Original: September 6, 2017

The atomic bomb and nuclear bombs are powerful weapons that use nuclear reactions as their source of explosive energy. Scientists first developed nuclear weapons technology during World War II. Atomic bombs have been used only twice in war—both times by the United States against Japan at the end of World War II, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A period of nuclear proliferation followed that war, and during the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union vied for supremacy in a global nuclear arms race.

Nuclear Bombs and Hydrogen Bombs

A discovery by nuclear physicists in a laboratory in Berlin, Germany, in 1938 made the first atomic bomb possible, after Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassman discovered nuclear fission.

In nuclear fission, the nucleus of an atom of radioactive material splits into two or more smaller nuclei, which causes a sudden, powerful release of energy. The discovery of nuclear fission opened up the possibility of nuclear technologies, including weapons.

Atomic bombs get their energy from fission reactions. Thermonuclear weapons, or hydrogen bombs, rely on a combination of nuclear fission and nuclear fusion. Nuclear fusion is another type of reaction in which two lighter atoms combine to release energy.

Manhattan Project

On December 28, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the formation of the Manhattan Project to bring together various scientists and military officials working on nuclear research.

The Manhattan Project was the code name for the American-led effort to develop a functional atomic bomb during World War II . The project was started in response to fears that German scientists had been working on a weapon using nuclear technology since the 1930s.

Who Invented the Atomic Bomb?

Much of the work in the Manhattan Project was performed in Los Alamos, New Mexico , under the direction of theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer , the “ father of the atomic bomb .”

On July 16, 1945, in a remote desert location near Alamogordo, New Mexico , the first atomic bomb was successfully detonated—the Trinity Test . It created an enormous mushroom cloud some 40,000 feet high and ushered in the Atomic Age.

Watch Historic Footage of Atomic Test Explosions

This footage of two nuclear‑test explosions in Hawaii reveal a destructive power so massive it’s still hard to fathom. | Courtesy of the Department of Energy Nevada Operations Office

How Did Emperor Hirohito Respond to the Atomic Bomb Attacks?

After the devastating bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the leadership of Japanese Emperor Hirohito was put to the test.

Hiroshima And Nagasaki Bombings

Scientists at Los Alamos had developed two distinct types of atomic bombs by 1945—a uranium-based design called “the Little Boy” and a plutonium-based weapon called “the Fat Man.” (Uranium and plutonium are both radioactive elements.)

While the war in Europe had ended in April, fighting in the Pacific continued between Japanese forces and U.S. troops. In late July, President Harry Truman called for Japan’s surrender with the Potsdam Declaration . The declaration promised “prompt and utter destruction” if Japan did not surrender.

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped its first atomic bomb from a B-29 bomber plane called the Enola Gay over the city of Hiroshima , Japan. The “Little Boy” exploded with about 13 kilotons of force, leveling five square miles of the city and killing 80,000 people instantly. Tens of thousands more would later die from radiation exposure.

When the Japanese did not immediately surrender, the United States dropped a second atomic bomb three days later on the city of Nagasaki . The “Fat Man” killed an estimated 40,000 people on impact.

Nagasaki had not been the primary target for the second bomb. American bombers initially had targeted the city of Kokura, where Japan had one of its largest munitions plants, but smoke from firebombing raids obscured the sky over Kokura. American planes then turned toward their secondary target, Nagasaki.

Citing the devastating power of “a new and most cruel bomb,” Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s surrender on August 15—a day that became known as ‘ V-J Day ’—ending World War II.

Museums Still Can’t Agree on How to Talk About the 1945 Atomic Bombing of Japan

The Los Alamos Historical Museum halted a Japanese exhibition on the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki because of a controversy over its message of abolishing nuclear weapons.

“Father of the Atomic Bomb” Was Blacklisted for Opposing H‑Bomb

After leading development of the first atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer called for controls on nuclear weapons. It cost him his job.

Photos: Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Before and After the Bombs

Before the 1945 atomic blasts, they were thriving cities. In a flash, they became desolate wastelands.

The Cold War

The United States was the only country with nuclear weaponry in the years immediately following World War II. The Soviet Union initially lacked the knowledge and raw materials to build nuclear warheads.

Within just a few years, however, the U.S.S.R. had obtained—through a network of spies engaging in international espionage—blueprints of a fission-style bomb and discovered regional sources of uranium in Eastern Europe. On August 29, 1949, the Soviets tested their first nuclear bomb.

The United States responded by launching a program in 1950 to develop more advanced thermonuclear weapons. The Cold War arms race had begun, and nuclear testing and research became high-profile goals for several countries, especially the United States and the Soviet Union.

Cuban Missile Crisis

Over the next few decades, each world superpower would stockpile tens of thousands of nuclear warheads. Other countries, including Great Britain, France, and China, developed nuclear weapons during this time, too.

To many observers, the world appeared on the brink of nuclear war in October of 1962. The Soviet Union had installed nuclear-armed missiles on Cuba, just 90 miles from U.S. shores. This resulted in a 13-day military and political standoff known as the Cuban Missile Crisis .

President John F. Kennedy enacted a naval blockade around Cuba and made it clear the United States was prepared to use military force if necessary to neutralize the perceived threat.

Disaster was avoided when the United States agreed to an offer made by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev to remove the Cuban missiles in exchange for the United States promising not to invade Cuba.

Three Mile Island

Many Americans became concerned about the health and environmental effects of nuclear fallout—the radiation left in the environment after a nuclear blast—in the wake of World War II and after extensive nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific during the 1940s and 1950s.

The antinuclear movement emerged as a social movement in 1961 at the height of the Cold War. During Women Strike for Peace demonstrations on November 1, 1961 co-organized by activist Bella Abzug , roughly 50,000 women marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons.

The antinuclear movement captured national attention again in the 1970s and 1980s with high profile protests against nuclear reactors after the Three Mile Island accident—a nuclear meltdown at a Pennsylvania power plant in 1979.

In 1982, a million people marched in New York City protesting nuclear weapons and urging an end to the Cold War nuclear arms race. It was one of the largest political protests in United States history.

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)

The United States and Soviet Union took the lead in negotiating an international agreement to halt the further spread of nuclear weapons in 1968.

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (also called the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT) went into effect in 1970. It separated the world’s countries into two groups—nuclear weapons states and non-nuclear weapons states.

Nuclear weapons states included the five countries that were known to possess nuclear weapons at the time—the United States, the U.S.S.R., Great Britain, France and China.

According to the treaty, nuclear weapons states agreed not to use nuclear weapons or help non-nuclear states acquire nuclear weapons. They also agreed to gradually reduce their stockpiles of nuclear weapons with the eventual goal of total disarmament. Non-nuclear weapons states agreed not to acquire or develop nuclear weapons.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s, there were still thousands of nuclear weapons scattered across Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Many of the weapons were located in Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine. These weapons were deactivated and returned to Russia.

Illegal Nuclear Weapon States

Some countries wanted the option of developing their own nuclear weapons arsenal and never signed the NPT. India was the first country outside of the NPT to test a nuclear weapon in 1974.

Other non-signatories to the NTP include: Pakistan, Israel and South Sudan. Pakistan has a known nuclear weapons program. Israel is widely believed to possess nuclear weapons, though has never officially confirmed or denied the existence of a nuclear weapons program. South Sudan is not known or believed to possess nuclear weapons.

North Korea

North Korea initially signed the NPT treaty, but announced its withdrawal from the agreement in 2003. Since 2006, North Korea has openly tested nuclear weapons, drawing sanctions from various nations and international bodies.

North Korea tested two long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles in 2017—one reportedly capable of reaching the United States mainland. In September 2017, North Korea claimed it had tested a hydrogen bomb that could fit on top an intercontinental ballistic missile.

Iran, while a signatory of the NPT, has said it has the capability to initiate production of nuclear weapons at short notice.

Pioneering Nuclear Science: The Discovery of Nuclear Fission. International Atomic Energy Agency . The Development and Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. NobelPrize.org . Here are the facts about North Korea’s nuclear test. NPR .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The essay delves into the significant impact of the atomic bomb on global politics and warfare, particularly as a catalyst for the Cold War. It explores how the bomb fueled the …

OVERVIEW ESSAY ATOMIC BOMBS T P 37 The US decision to drop atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki altered the course of the Asia-Pacific war and …

atomic bomb, weapon with great explosive power that results from the sudden release of energy upon the splitting, or fission, of the nuclei of a heavy element such as plutonium or uranium.

The United States is widely recognized for ending World War II by dropping atomic bombs on two cities in Japan; however, they also caused incalculable human anguish difficult to justify.

This collection of essays and primary source documents, written primarily from a revisionist perspective, provides numerous critiques of the use of the atomic bombs. It includes a foreword by physicist Joseph Rotblat , who …

Eleven days later, on August 6, 1945, having received no reply, an American bomber called the Enola Gay left the Tinian Island in route toward Japan. In the belly of the bomber was “Little …

The essay delves into the significant impact of the atomic bomb on global politics and warfare, particularly as a catalyst for the Cold War. It explores how the bomb fueled the …

The atomic bomb and nuclear bombs are powerful weapons that use nuclear reactions as their source of explosive energy. Scientists first developed nuclear weapons technology during World War...