The State of Not Belonging Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

The state of not belonging, benefits to be reaped, the host country reactions.

Immigrants are always faced by state of fear and impermanence because the host country and it citizenry never want to accept them as their own. This paper analyses the work of two writers on the issue; Rites of Passage and Rights in Citizenship in Post Millennial Ireland , authored by Dianna Shandy, and Female Literature of Migration in Italy , which has been authored by Lidia Curti, which paint to us a picture of what it is like to be a refugee immigrant.

The two authors draw to us a very clear image of the plight of African immigrants to foreign countries. The immigrants are in a state of lost owing to the fact that they are unwelcome in their host countries while at the same time they cannot go back home owing to the conditions of life back from which they were running from. This leaves them foreigners in their host countries as well as in their home African countries.

Shandy tells us of pregnant African women who run away from home to Ireland so that they can acquire rights and privileges of an Irish Citizen. The Irish Jus ….Policy which guaranteed citizenship to every individual born on Irish soil attracted many women to Ireland.

They were seeking a sense of belonging to a country which will provide them with an improved condition of life both for themselves and for their babies. For them, the right to citizenship of the babies they were carrying to be acquired upon birth would see them acquire various rights too in the country as the mothers of those baby, something they were willing to risk for if only for a better future for themselves as well as for their children.

Curti on the other hand presents to us a case of young African writers who are refugees in Italy. Their narrations tell us of how they got married to Italian men who became the fathers of their children but later abandoned them leaving them in a situation of loss and feelings of insecurity on their nationality.

Their marriage and subsequent bearing of children with Italian men had made them acquire a sense of belonging, unknown to them it was short-lived and soon they would be haunted by an everyday question of ‘where is home for me?’ Others were born within Italian families by Italian citizens and that must have given them hope that they belong in their host country.

But the only mistake was that they were born in black skins and still carried the ‘black blood’ in their veins. And as they grew up, they realize that they, just like all the others, are still foreigners.

In their new ‘home’, the immigrants will get everything that their original country could never have offered them. To start with, they are assured of a peaceful political stability as opposed to the scourge of war that persists in most African countries.

They can therefore relax knowing that they are not under the immediate danger of being mercilessly slaughtered by their neighbor next door and therefore their children will also be safe. They are also safe from harmful community practices which are performed back at home such as Female Genital Mutilation, (Curti, P.72), and Early marriages which are very common.

Further, the host countries have all the facilities necessary. The health facilities are inexpensive as they are availed by the state. Their babies will therefore be born safely as compared to Africa where mortality rate is very high. Further, their basic needs of food shelter and clothing will be easily satisfied since the standards of living are quite high so their children can say goodbye to hunger.

They will also get access to the highest educational facilities which will not be found back at home and they will take on degrees and other tertiary education something they would not have been able to do.

Moreover, when they are in the host country, it will be an opportunity to help those people back home by sending them some help. Most of them will send money and material items to help ease out the poor situation their kinsmen are encountering at home. They will even try to smuggle in some of their relatives to come and share in enjoying this vast benefits within the countries they would want so much to call home.

But underlying all this is the hostile reaction and rejection they encounter from the people they live with on a day to day basis. The people they so much want to identify themselves with as their brothers and sisters.

The people they work with, school with, rent houses from and live with, the people they are seeking acceptance from. Instead, they will call them niggers, abuse them and assault them, both physically and emotionally, (Shady, P.820). They refuse to have anything to do with them.

They overwork them and underpay their services and only want them working as underdogs not as honorable people, (Curti, P.70). They do not want to get into contact with them, they humiliate them and they want them to go back to Africa.

They do not want to be the one to grant them asylum as, they claim, they pollute their population and they are afraid they may out-reproduce them. The same individuals looked at as helpless and harmless, in need of care and protection, are now viewed as posing a social security issue to elicit legal measures from the state, aimed at driving them out.

Shandy hits the nail on the head in explaining this situation in Ireland, through the 2004 referendum which saw the Irish population unanimously seek to limit foreigners acquisition of citizenship, through what they called ‘unprecedented births’, namely births by non-national citizens, (Shandy, P.809), and mostly, Africans. Even the courts are making decisions to show a situation where black mothers may be deported back to Africa.

In Italy on the other hand, they are faced with incessant immigrant’s law and the bureaucracy that one has to go through just to “pass from the status of illegal immigrants to that of ‘non-EU citizens with work permit’ and to the long wonderings on the streets in Rome to escape police visits at home, (Curti, P. 70). The same state that was supposed to offer them protection and care has turned to be the one nightmare for them.

In the end, the immigrants are left in the middle not knowing whether to go back to their country of origin or to remain in their host countries. They do not know which culture or language to adopt, where their national loyalty falls and most importantly, the place to call home.

Africa is not so much of a home for them because the situation back there is unbearable and the host country is not a home either since the rejection and feeling of ‘foreignty’ is too great and so consciously incessant to ignore. They are now left in a state of fear, fear of not knowing what will happen tomorrow not just to them but also to their children.

Whether they will still be doing their normal activities or they will be forced to be on the move, like the nomads they have always been. Only they know they do not belong anywhere, they lack identity and are in what Curti calls, a state of impermanence.

Curti, Lidia. Female Literature of Migration in Italy . Feminist Review, No. 87, Italian Feminisms. 2007 pp. 60-75.

Shandy, Dianna. Irish Babies, African Mothers: Rites Passage and Rights in Citizenship in Post-Millennial Ireland , Anthropological Quarterly, Vol. 81, No. 4, Kids at the Cross Roads: Global Childhood and the Role of the State, 2008, pp. 803-831.

- Nationalism and Identity Among Middle East Immigrants in Australia

- Immigration and Multiculturalism in Australia

- President Obama's Justification for Killing bin Laden

- Sexual Harassment at the Workplace

- Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Theory of Just War

- Australian Nationalism and Middle East Immigrants

- Changing labor market as a potential causal factor in declining immigrant outcomes in Canada

- Migration and Development

- Relationship Between Japanese Population in the US and Illegal Immigrants

- How Illegal Immigrants Reduce the Earning Power of Americans?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, May 8). The State of Not Belonging. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-state-of-not-belonging-essay/

"The State of Not Belonging." IvyPanda , 8 May 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/the-state-of-not-belonging-essay/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'The State of Not Belonging'. 8 May.

IvyPanda . 2019. "The State of Not Belonging." May 8, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-state-of-not-belonging-essay/.

1. IvyPanda . "The State of Not Belonging." May 8, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-state-of-not-belonging-essay/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The State of Not Belonging." May 8, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-state-of-not-belonging-essay/.

More From Forbes

Missing your people: why belonging is so important and how to create it.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Belonging is a fundamental human need.

The pandemic has played havoc with our mental health, and a significant factor in our malaise is that we’re missing our people—terribly. We long for friends, family and colleagues. We are hardwired for connection, and with the need for social distancing and the reality of being away from the workplace—and everything else—for such a long period of time, we are struggling.

It’s all about our need for belonging—but belonging is more than what you might have thought. Understanding it can help contribute to our emotional wellbeing and it can pave the way toward a more fulfilling year ahead. Here’s what to know and how to create it.

Engagement and Social Identity

Belonging is, of course, that feeling of connectedness to a group or community. It’s the sense that you’re part of something. You feel attached, close and thoroughly accepted by your people. But belonging is more than just being part of a group. Belonging is also critically tied to social identity—a set of shared beliefs or ideals. To truly feel a sense of belonging, you must feel unity and a common sense of character with and among members of your group.

In his book, the Happiness Hypothesis , Jonathan Haidt calls this ”vital engagement.” It is a web of relationships and a sense of community in which you feel connected with activity, tradition and the group itself. Jeanine Stewart, senior consultant with the Neuroleadership Institute, whom I had the chance to interview, says when we share a sense of social identity with a group, we can lean in, use our strengths and be authentically who we are. “Being surrounded by other human beings doesn’t guarantee a sense of belonging. Belonging actually has to do with identification as a member of a group and the higher quality interactions which come from that. It’s the interactions over time which are supportive of us as full, authentic human beings.” All of these are important to fulfillment and to the success of the organization as a whole.

A study published in PlosOne found belonging was more than just about having friends. Group membership was also important, and it contributed to self-esteem. A large group of friends didn’t predict self-esteem but belonging to multiple groups did. Says Jolanda Jetten, the lead researcher, "Groups often have rich value and belief systems, and when we identify with groups, these can provide a lens through which we see the world.” One of the reasons work is such a powerful source of belonging is because we typically share identity and goals with our team.

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024

Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024, a fundamental need.

Belonging is a fundamental part of being human: We need people and this need is hardwired into our brains. A recent MIT study found we crave interactions in the same region of our brains where we crave food, and another study showed we experience social exclusion in the same region of our brain where we experience physical pain. Work at the University of British Columbia found when we experience ostracism at work, it can lead to job dissatisfaction and health problems. In a similar vein, a study at the University of Michigan found when people lack a sense of belonging, it is a strong predictor of depression. In fact, it is an even stronger predictor than feelings of loneliness or a lack of social support.

It’s also telling to look at animal examples. According to Stewart, “When something is conserved across species, it’s an indication that some elements of our behavior are driven by things that are more basic, and which we can witness.” Research from Florida Atlantic University provides a telling example in beluga whales. Their study found these whales form complex social relationships with close kin, but also with distantly related and unrelated whales. This is mirrored in human behavior as well, in our connections with close friends and family as well as with those who are more distant.

The Impact on Habits and Performance

The human desire for connection also drives behavior. Smartphone design and addiction are a case in point: A study published in Frontiers in Psychology found smartphones are compelling because they tap into fundamental needs to connect. According to the research, humans have a deep desire to monitor others and to be monitored by them—to be seen and heard and considered by others. It is this alignment with our social needs which makes smartphones especially hard to put down. Separate research related to teams at work found when people felt a great level of cohesion with their colleagues, they performed better and the desire for acceptance from the group was a greater motivator than money. People have a clear need to identify with a group and be accepted as a vital member of a community.

Creating Belonging

Since belonging is so important—and since the pandemic has exacerbated the need for belonging—we must be intentional about creating it with and among others. We can do this in tangible ways.

- Embrace groups . Build your friendships with individuals, but also consider joining personal or professional groups with which you feel a common sense of purpose and solidarity. Remind yourself of the identity you share with co-workers and consider joining or creating additional groups with your work colleagues. Join the running club at your company or start a readers group with others who work for your organization. Being part of something—and the coherence and alignment between your goals and the group’s purpose will help you feel a greater sense of belonging.

- Be authentic . According to some experts, trust is built when you are authentic, empathetic and perceived as competent. You can create the conditions for belonging when you are open and vulnerable as well as when you are empathetic toward others. Researcher John Cacioppo also found when people interacted more effectively with others, it tended to mitigate loneliness and pave the way toward belonging.

- Signal acceptance . When people lack a sense of belonging, they may feel threatened or alone, causing them to withdraw or hold back. On the other hand, Stewart points out, “When we are feeling a sense of comfort, we are in the best state physiologically to engage.” Colleagues can signal acceptance and help ensure the people around them feel safe, by asking questions, listening and demonstrating focused attention. The start of a meeting can be an opportunity according to Stewart, “Choose to take a moment, if you’re leading a meeting, to ask how people are doing and then really listen. Listening is the new super power,” she says. “If we can’t create belonging through physical closeness in the ways we used to, we can and must think about how we might create that through focused attention and listening.” Creating these kinds of conditions will contribute toward our collective willingness to invest ourselves.

Belonging is a necessary ingredient for our performance—individually, in teams and for our organizations—because we can more effectively engage and bring our best selves to work. And even more importantly, belonging is good for our wellbeing as humans. It’s important for individual physical, mental and emotional health and it’s critical to the health of our communities. The pandemic has brought belonging into sharpened focus and our opportunity is to find a way to create it for ourselves and others.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Increase Your Sense of Belonging

Jade / Getty Images

Sense of Belonging in Action

Effect of the sense of belonging, increase your sense of belonging.

The sense of belongingness, also known as the need to belong, refers to a human emotional need to affiliate with and be accepted by members of a group. Examples of this may include the need to belong to a peer group at school, to be accepted by co-workers, to be part of an athletic team, or to be part of a religious group.

What do we mean by the sense of belonging? A sense of belonging involves more than simply being acquainted with other people. It is centered on gaining acceptance, attention, and support from members of the group as well as providing the same attention to other members.

The need to belong to a group also can lead to changes in behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes as people strive to conform to the standards and norms of the group.

In social psychology , the need to belong is an intrinsic motivation to affiliate with others and be socially accepted. This need plays a role in a number of social phenomena such as self-presentation and social comparison .

What inspires people to seek out specific groups? In many cases, the need to belong to certain social groups results from sharing some point of commonality. For example, teens who share the same taste in clothing, music, and other interests might seek each other out to form friendships. Other factors that can lead individuals to seek out groups include:

- Pop culture interests

- Religious beliefs

- Shared goals

- Socioeconomic status

People often present themselves in a particular way in order to belong to a specific social group. For example, a new member of a high school sports team might adopt the dress and mannerisms of the other members of the team in order to fit in with the rest of the group.

People also spend a great deal of time comparing themselves to other members of the group in order to determine how well they fit in. This social comparison might lead an individual to adopt some of the same behaviors and attitudes of the most prominent members of the group in order to conform and gain greater acceptance.

Our need to belong is what drives us to seek out stable, long-lasting relationships with other people. It also motivates us to participate in social activities such as clubs, sports teams, religious groups, and community organizations.

In Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs , the sense of belongingness is part of one of his major needs that motivate human behavior. The hierarchy is usually portrayed as a pyramid, with more basic needs at the base and more complex needs near the peak. The need for love and belonging lie at the center of the pyramid as part of social needs.

By belonging to a group, we feel as if we are a part of something bigger and more important than ourselves.

While Maslow suggested that these needs were less important than physiological and safety needs, he believed that the need for belonging helped people to experience companionship and acceptance through family, friends, and other relationships.

A 2020 study on college students found a positive link between a sense of belonging and greater happiness and overall well-being, as well as an overall reduction in mental health outcomes including:

- Hopelessness

- Social anxiety

- Suicidal thoughts

How do we create a sense of belonging? There are steps you (or a loved one who is struggling) can take to increase the sense of belonging.

- Make an effort : Creating a sense of belonging takes effort, to put yourself out there, seek out activities and groups of people with whom you have common interests, and engage with others.

- Be patient : It might take time to gain acceptance, attention, and support from members of the group.

- Practice acceptance : Focus on the similarities, not the differences, that connects you to others, and remain open to new ways of thinking.

A Word From Verywell

A sense of belonging is a crucial for good physical and mental health. If you continue to struggle with loneliness or the sense of not fitting in, talk to your doctor or mental health professional. They can help you to identify the root of your feelings and provide strategies for achieving belongingness.

Schneider ML, Kwan BM. Psychological need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation and affective response to exercise in adolescents . Psychol Sport Exerc . 2013;14(5):776–785. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.04.005

Pillow DR, Malone GP, Hale WJ. The need to belong and its association with fully satisfying relationships: A tale of two measures . Pers Individ Dif . 2015;74:259-264. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.031

Kenrick DT, Griskevicius V, Neuberg SL, Schaller M. Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations . Perspect Psychol Sci . 2010;5(3):292–314. doi:10.1177/1745691610369469

Moeller RW, Seehuus M, Peisch V. Emotional intelligence, belongingness, and mental health in college students . Front Psychol . 2020;11:93. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00093

Fisher LB, Overholser JC, Ridley J, Braden A, Rosoff C. From the outside looking in: sense of belonging, depression, and suicide risk . Psychiatry . 2015;78(1):29-41. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2015.1015867

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Embarrassment

Stop trying to fit in, aim to belong instead, don't waste time and energy fitting in when you could truly belong..

Posted October 17, 2013 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Embarrassment?

- Take our Self-Disclosure Test

- Find a therapist near me

- "Fitting in" means changing oneself to be part of a group, whereas "belonging" means showing up as oneself and being welcomed.

- Acting intentionally in order to facilitate connection is not the same as changing oneself to "fit in."

- Giving up the effort to "fit in" leaves more energy for things that truly matter.

I confess that I haven't read Brene Brown's books yet, though I have seen the TED videos. Her books get bought most frequently together with mine on Amazon, so I really should learn more about her work. What I know of it, I have enjoyed reading.

Fitting in is not belonging

I recently read an article she wrote for Oprah.com , and was struck by her description of the concept of fitting in versus truly belonging. In Brene's words, fitting in is not belonging:

"In fact, fitting in is the greatest barrier to belonging. Fitting in, I've discovered during the past decade of research, is assessing situations and groups of people, then twisting yourself into a human pretzel in order to get them to let you hang out with them. Belonging is something else entirely—it's showing up and letting yourself be seen and known as you really are—love of gourd painting, intense fear of public speaking and all. "Many of us suffer from this split between who we are and who we present to the world in order to be accepted. (Take it from me: I'm an expert fitter-inner!) But we're not letting ourselves be known, and this kind of incongruent living is soul-sucking."

She says so well what I know to be true. During various seasons of my life, I have not fit in. I was too smart, too awkward, and too much of a "goody-two-shoes" in high school, plus I didn't have the right clothes. As you can probably guess, I felt different from the other docs-to-be in med school. I still feel a bit awkward when I'm around other medical doctors; it's hard to explain why.

My whole life I've known, usually painfully so, that I'm not very "normal" (even if I might appear to be, at first glance).

Are you aware that you spend a significant amount of energy trying to fit in? Have you noticed when you do it? Are you ready to give it up?

Committing to belonging

I've been in one social situation in the couple of days since reading Brene's article. I was meeting a new group of people, and something someone said triggered a response from me based on something I learned at a Harvard course last month. I mentioned Harvard in my comment, and noticed the person's face tighten a bit. At least I thought so; I'm pretty good at reading people and excessively aware of facial expressions and body language .

I cringed inside and felt that familiar shame . Darn. I probably looked like I was bragging or name-dropping when really I was just so excited about the information. To me, where I learned the information I referred to makes it more credible.

This brought up all my usual "shut up and try to act more normal" feelings, but because of Brene (and admittedly with some effort) I dismissed them. So what? I'm an info nerd and going to Harvard to learn stuff about mind-body medicine is more exciting to me than going to Disneyland.

If I don't spend so much energy worrying about what others think of the real me (or trying to hide the real me), I'll have lots more left over for dancing flamenco.

(Note: There is a difference between the wisdom of choosing words wisely in order to facilitate connection and real relationship versus feeling "not good enough" and trying to be something you're not in order to gain acceptance. The two feel very different, and I am writing about the latter.)

So will you take on this challenge? Will you commit to belonging based on who you really are, and give up the soul-sucking goal of always trying to fit in?

Copyright Dr. Susan Biali, M.D. 2013

Susan Biali Haas, M.D. is a physician who speaks and writes about stress reduction, burnout prevention, mental health, wellness and resilience.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Poet and Philosopher David Whyte on Belonging and How to Be at Home in Yourself

By maria popova.

“Sit. Feast on your life,” Nobel-winning poet Derek Walcott exhorted in his breathtaking ode to being at home in ourselves . “We feel safest when we go inside ourselves and find home,” Maya Angelou observed in Letter to My Daughter , “a place where we belong and maybe the only place we really do.” But how do we find that place to make a home in, to set the table at which we can feast on our lives?

That’s what English poet and philosopher David Whyte — who has written beautifully about what maturity really means , how to break the tyranny of work/life balance , and the true meaning of love and friendship — explores in this soulful, lo-fi short monologue on the essence of belonging and what it means to come home to ourselves:

To feel as if you belong is one of the great triumphs of human existence — and especially to sustain a life of belonging and to invite others into that… But it’s interesting to think that … our sense of slight woundedness around not belonging is actually one of our core competencies; that though the crow is just itself and the stone is just itself and the mountain is just itself, and the cloud, and the sky is just itself — we are the one part of creation that knows what it’s like to live in exile, and that the ability to turn your face towards home is one of the great human endeavors and the great human stories. It’s interesting to think that no matter how far you are from yourself, no matter how exiled you feel from your contribution to the rest of the world or to society — that, as a human being, all you have to do is enumerate exactly the way you don’t feel at home in the world — to say exactly how you don’t belong — and the moment you’ve uttered the exact dimensionality of your exile, you’re already taking the path back to the way, back to the place you should be. You’re already on your way home.

Complement with Vonnegut’s magnificent commencement address on belonging , Hermann Hesse on what trees teach us about belonging , and Tove Jansson’s philosophical vintage Moomin comics on our quest for belonging , then revisit Whyte’s wisdom on anger and forgiveness .

— Published June 29, 2015 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2015/06/29/david-whyte-belonging/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, culture david whyte philosophy psychology, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

Learn to build a world where everyone belongs. Take free classes at OBI University. Start Now

The Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley brings together researchers, organizers, stakeholders, communicators, and policymakers to identify and eliminate the barriers to an inclusive, just, and sustainable society in order to create transformative change.

- Faculty Clusters

john a. powell is an internationally recognized expert in the areas of civil rights, civil liberties, structural racism, housing, poverty, and democracy.

Launched in Fall 2018 as the Institute's official podcast, Who Belongs? is an ongoing series that demonstrates our commitment to public dialogue.

- Email Sign Up

- Publications

On Belonging

- Publication

- January 19, 2022

- By john a. powell & Stephen Menendian

< Previous page | Next page >

Introduction

“Belonging” is both a powerful and ambiguous concept. It reflects something essential to the human experience — a core need — but is not as tangible or easily comprehensible as shelter, nutrition, and rest. Appropriately, belonging rests in the middle of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. 1 This suggests that belonging is both tremendously important and central to the human condition. Yet exactly why that is so is less obvious. Defining belonging is no simple task.

This essay serves as a backdrop to the papers submitted for this volume. These papers cover topics ranging from motherhood-driven civic engagement by migrant mothers in Sweden, to “togetherness” oriented childhood education in Denmark, to refugee-led Covid-19 responses in Berlin and their impact on the experience of integration. As these papers draw upon a conception of belonging presented or prompted by us, we wish to describe the contours of our understanding of the term so the papers make sense in context. Our presentation is not exhaustive, but should be sufficient to the goal of making the papers comprehensible in their own terms.

Defining Belonging in the Negative

Perhaps the best way to understand belonging is through the light of contrast, by defining what it is not. Let’s start with Equity and Inclusion. Equity and Inclusion refer to how social groups are stratified across society and critical institutions. Inclusion is a concept that demands institutions and communities open themselves to members of formerly excluded social groups. For example, in the 1960s Yale University finally admitted women onto its campus as undergraduate students, decades after most public universities had done so. 2 Inclusion is a powerful regulative ideal, as well as a strategy or mechanism for reducing social inequality.

Equity moves beyond simple or formalistic notions of equal treatment. When groups are situated differently in society with respect to status, resources, and opportunities, then equal treatment can perpetuate rather than ameliorate social, economic, legal, or political inequality. This is where ‘equity’ comes in. Equity is a recognition that sometimes fair treatment requires differential treatment. Most European constitutional systems recognize equity in this form, as captured by the Spanish expression: “ igual a los iguales y desigual a los desiguales ”, also known as equal treatment.

This is obvious in some cases, as when we prioritize vulnerable groups for vaccines or create special accommodations for people with disabilities or pregnant women. But it is denied in other contexts in which formal equal treatment can lead to significant disparities.

While important concepts, neither equity nor inclusion guarantee belonging. It is possible for institutions to become accessible to formerly excluded groups, and for social or economic disparities to be ameliorated or even eliminated, even as social stigmas or feelings of exclusion persist. Women, for example, were admitted into Yale, but excluded from the social life of the university, from its social clubs to its dining halls. Tangible resources and measurable disparities can be equalized even as certain social stigmas persist, such as caste or gender associations. In India, for example, affirmative action programs can guarantee employment opportunities for lower caste social groups, but that does not mean that cultural assumptions have been extirpated. 3

In this sense, belonging goes beyond Inclusion and Equity, yet includes them in meaningful ways. It would be difficult to imagine that belonging can fully manifest in a society where social groups are excluded from key institutions or large disparities exist between those groups. Yet, belonging calls for something more.

Manifesting Belonging

In our conception, Belonging is both objective and subjective. It can be quantified and measured, but it is also perceptual, laying in the eye of the beholder. In this respect, Belonging, unlike both Equity and Inclusion, contains a psychological component — an affective component, which shapes the way social groups regard whatever it is they are regarding, an institution, a city, or even society writ large.

If members of a social group feel as if they belong, then belonging exists. But if they do not, despite being included and having little tangible resource inequities or other disparities between groups, then belonging is lacking. Thus, in biographies of women such as Sonia Sotomayor and Michelle Obama, they report a feeling of “not belonging” on Princeton’s campus of the 1970s. 4 Both women came from vastly different social and economic milieus — the Bronx and the south side of Chicago, respectively — than that which they encountered on that Ivy League campus.

Belonging can be measured by campus climate, and climate surveys, but these surveys must reflect both objective and subjective experiences. 5 This also explains the development of so-called “mindset” interventions, messages designed to signal or express greater belonging, and hopefully engender it in the process. 6

This reveals a core element of belonging: the expressive or communicative message that a group belongs. It can be expressed explicitly, through representation or by signaling that members of a particular group are welcome in a particular space, institution, or community. It can also be expressed implicitly, as when accommodations are made, such as when special food or holidays are provided for. For example, the French Military created accommodations for Muslim cultural traditions by having halal foods served in the military, and providing space for prayer and worship. 7 The absence of accommodations or sensitivities is an equally simple way to signal that members of certain groups do not belong.

Illustration by Peter Wood

Realizing Belonging

As important as these components are to belonging, there is still a missing component to a full manifestation of belonging. Belonging is perceptual and tangible; it is a feeling and a practice. But belonging requires more than accommodation; it also demands agency.

A board or council may be diverse and inclusive, but if members of socially marginalized groups are included without the ability or agency to re-shape and redesign the institution, then inclusion is realized without full belonging. In this model, members of the socially marginalized group are brought in as guests rather than as members. Simply revisiting holiday schedules or respective food traditions can help members of social groups feel more welcome, but they do not create a sense of ownership or control over the mission, values, or core operation of the institution.

Belonging is realized fully when included groups have more than a voice — they are actually able to reshape the institution together with existing stakeholders. Thus, hospitals and other anchor institutions are not just responsive to elite sensibilities, but oriented to serve communities’ needs. In the process, some institutions may need to be redesigned or their mission rethought. Efforts toward realizing this conception of belonging are already underway in examples like Germany’s requirement for employees to comprise a third of supervisory board seats in companies of at least 500 employees, and half in companies of 2000 or more. Research shows that this measure to provide a decision making role to employees broadens the issues and concerns companies give attention to while simultaneously increasing profits and productivity. In another instance of co-creative belonging, the organization Participatory City worked with the council of the Borough of Barking and Dagenham in the United Kingdom to address the area’s high levels of homelessness, violence, and unemployment. They worked with community members to create a welcoming committee for newcomers, plant community gardens together, and collaborate on community improvement projects. These activities have fostered a sense of togetherness and shared destiny among the residents of Barking and Dagenham, as people have overcome prejudices and isolation to strengthen bonds and deepen community. This kind of agency — co-creation — is the most radical and potentially transformative aspect of true belonging.

How, then, can these ideas be brought into practice? This digital volume makes significant headway into answering this question. Because Europe and America, and indeed, much of the world, are struggling with many of the same issues, we seek to transport the frame of belonging into the European context to explore models and exciting case studies, as well as to deepen our collective understanding of the problems that impede a sense of belonging. This volume is one fruit of this emerging work.

Toward Belonging

The papers brought together for this online publication illuminate our understanding of the nuances of belonging and model how we can realize it in practice. Exploring topics and themes such as refugee integration, civic engagement and mutual aid, human development and well-being, motherhood and race, as well as much more, this volume is a major step toward deepening our understanding of inter-group dynamics and processes, interventions, and case studies that can promote or lead toward greater belonging. What follows is a brief introduction to a few of the papers included in this digital collection.

Jessica Joelle Alexander’s paper on “Obligated Togetherness” or “ Fællesskab ” is a fascinating exploration of holistic cultural values and practices that emphasize well-being and inclusion in Denmark. Drawing upon a major national survey conducted in 2016, the author demonstrates how certain cultural practices, namely, intentionally and specifically incorporating lessons on social connection and wellbeing into parenting and education, contribute to societal well-being and belonging. She explores, in local terms, how the focus on togetherness and connectedness may lead to a correlation with happiness — in a country that is consistently described as one of the happiest in the world.

In his essay, Tom Crompton, the Director of the Common Cause Foundation, brings to the fore the role that values — and especially our perception of fellow-citizens’ and neighbors’ core values — plays in community cohesion, well-being, and a sense of belonging. Unsurprisingly, he finds that recognising our mutual core values and value commitments can bridge understanding and build community. Looking at programming his organization has conducted in Manchester, England, the author describes community based interventions work in the real world.

Jonelle Twum’s essay explores the grassroots activities of migrant mothers in the suburbs of Sweden. Making use of her fieldwork and interviews, she helps us understand processes of racialization, integration, and gender-informed interventions in Sweden’s exurban areas. In particular, she illuminates strategies employed by these women to thrive and to imagine spaces of greater belonging — even as official institutions and municipal leadership fail to provide the material resources needed to support their communities.

Daniel Stanley, the CEO and founder of the Narrative Futures Lab, deconstructs our understanding of polarization. Although conventionally understood in simplistic or categorical ways, such as racial or economic polarization, he suggests that polarization is best viewed as a byproduct of deeper forces and dynamics, and related to a number of other disturbing phenomena. This essay challenges assumptions about individual and group psychology and political conformity from the post-war period, while also arguing, more hopefully, that a better understanding of the problem can lead to belonging and social cohesion.

Evan Elise Easton provides a broader perspective on refugee experiences in Germany, as they relate to integration processes and activities that foster a sense of belonging. In particular, their essay describes and elevates the cutting edge work of refugee led organizations in Berlin during the Covid-19 Pandemic — allowing us the opportunity to see how integration relates to belonging and community building in a time of social turmoil.

Building Belonging

Belonging is a broad, encompassing concept, and there is no single prescription for how it can be manifested or realized, as the papers in this volume will amply illustrate. It is also a multi-faceted concept relating to agency, connection, place, identity, and security, among other elements. As a result, belonging can exist in many forms or be expressed or experienced in a myriad of different ways.

Belonging can exist in a superficial sense or a deeper sense. It can be experienced as a social dynamic between people or institutionalized in governance, organizations, and associations. It can become embodied in laws, codes, rules and regulations, or it can exist as norms and cultural values. Intergroup dialogue projects in the United States and Europe that not only create spaces for exchanging stories, but also teach how to communicate across boundaries of difference or realize shared values, advance belonging.

The pressures and challenges within our societies make the work of building belonging more complicated, but also more necessary. Economic inequality, displacement and migration, social media and technology, ethnic conflict and religious violence, wars and political oppression, are tectonic forces that build pressure under our societies. The pressure is often relieved through social fault lines, such as those of race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity and religion. If we are to build stronger and more cohesive societies, less susceptible to the dangers of demagoguery and division, then we need to find ways to retrofit our social structures and institutions to survive these pressures.

Art description: “As I read through the introduction for this article, I wanted to understand inside myself what it means to feel a sense of belonging. After some processing, I was drawn to the feeling of sitting around a campfire with friends — an activity that creates, within a foreign space, a sense of home and shelter. In this image the four figures gather around the flame, cradled within a nurturing, open gestured hand.”

Artist bio: Peter Wood is a British artist who was born in Bedford, England in 1991. He studied in London at Central St Martin’s College of Art and Design, and later at the University of Westminster, where he graduated with a degree in Illustration and Visual Communication in 2014. He has been living in Berlin since 2016 and works as an artist, selling prints at an outdoors art market, and through illustration commissions.

- 1 Maslow, Abraham. “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review 50, no. 4 (1943): 370–96.

- 2 Fetters, Ashley. “The First of the ‘Yale Women.’” The Atlantic , September 22, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/09/first-undergraduate-women-yale/598216/.

- 3 "Why India Needs a New Debate on Caste Quotas.” BBC News , August 29, 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-34082770.

- 4 Lithwick, Dalia. “Sonia Sotomayor, Outsider.” Slate , September 4, 2015. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2015/09/sonia-sotomayor-conversation-at-notre-dame-first-latina-doesnt-feel-like-she-belongs-on-supreme-court.html .

- 5 “My Experience Survey 2019: Campus Findings and Recommendations.” UC Berkeley Office of the Chancellor, 2020. ttps://myexperience.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/myexperiencesurvey2019-final.pdf .

- 6 Dweck, Carol. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success . New York: Ballantine Books, 2006.

- 7 Onishi, Norimitsu, and Constant Méheut. “In France’s Military, Muslims Find a Tolerance That Is Elusive Elsewhere.” New York Times , June 26, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/26/world/europe/in-frances-military-muslims-find-a-tolerance-that-is-elusive-elsewhere.html .

- Username or Email: Password: signup now | forgot password? Remember Me

- Additional Languages & Regions

- Arabic – بالعربية

- Farsi - فارسی

- Italy - Italian

- Netherlands - Nederlands

- New Zealand & Oceania

- South East Asia

EFT International

Advancing EFT Tapping (Emotional Freedom Techniques) Worldwide Since 1999

The Pain of “Not Belonging”

By: Carna Zacharias-Miller Categories: Anxiety , Core Issues , EFTfree Archives , Fear , Inner Child EFT , Self-Acceptance

Here are some thoughts about the feeling "I don't belong anywhere, and it hurts so much" with a tapping script. This is an issue that almost all of my clients have.

Where does this feeling of not belonging come from?

We all feel that way under certain circumstances. However, if it is a very painful feeling that comes up again and again, if it is the theme of one's life, then it originates in childhood (and, possibly, past lives).

It is often mixed with other emotions, like loneliness, deep sadness, feeling different, "what's wrong with me", and abandonment and rejection. As we know, it is a basic need for children to belong, to have a safe place, to be at least validated if not cherished.

There are several childhood scenarios that bring up this ongoing, basic feeling.

Definitely a “missing mother”, which is a mother who was very sick or died, or, more common, a mother who was emotionally not connected to the child. If we don’t belong to our mother, who do we belong to? An absent father who is physically or emotionally not a secure part of a child’s life can have that effect too.

If we did not have a safe, secure place as a child and at least one adult person who gave us that feeling of belonging, we will have this constant yearning to belong somewhere, with someone.

How does it play out in adult life?

In many ways, and all of them are painful and difficult to handle. There are two extremes: We are constantly looking for that place or person that gives us a feeling of belonging, we are needy and a people pleaser. Separation of any kind, like a divorce, the death of a parent, or a job loss is very hard on us, and we are re-traumatized when that happens.

The other extreme is never allowing ourselves to attach to any person or place and always defending our so-called independence, which is no emotional freedom at all. We roam from place to place, from person to person, never finding inner peace.

What is the difference between fitting in and belonging?

We force ourselves to fit in where we don’t belong. It’s the round peg in the square hole, or the swan trying to be a duck. Belonging is natural and organic. It supports who we truly are.

How do we know that we belong, and can we learn to belong?

When that happens with a place or person, or a group of people, we just know. All of a sudden, there appears the right man, woman, child or group, the right spiritual path, or the kind of work that makes us happy. We know when it is just right for us. ("I was born to do this/to belong to this family/to be at this place/to follow this path"). Like the Ugly Duckling who finally found his people, the swans.

How do we get there? Mostly by trial and error, that is why this feeling is especially painful when we are young. However, we have to be able to learn from our painful experiences. It takes awareness and courage. Out of that flows the right action.

Is there an upside, a hidden treasure to this very painful issue?

That is the whole point of my work. Because it is so very painful, we can’t ignore it. The first rule is to avoid being self-destructive, or at least to be aware of it. Like numbing ourselves with food or substances, playing out big emotional dramas that hurt our relationships, or even staying in abusive situations.

The very best way to handle this is to go on a spiritual journey. Finding out want we really want in life, who we really are, what people and places are good and supportive for us. At the end, we'll find out that there is no separation. We are all one and belong to each other and to Source.

Tapping on “I don’t belong”

You agree to take responsibility for yourself during this process. If it is emotionally very intense, please contact and work with an experienced EFT practitioner.

First, tune in to your general feeling of emotional (and/or physical) pain regarding this issue and put your discomfort on a scale 0 to 10. 0 is no pain at all, and 10 is extreme. Write this number down. Start tapping on the KARATE CHOP point (side of the hand), and say out loud:

Even though I feel lost, unsafe, and out of place everywhere, I deeply and completely love and accept myself Even though I don’t belong anywhere and it hurts so much, I honor and respect myself Even though I have never felt safe when I was a child, I allow myself to feel safe now.

Now tap on the following points while saying out loud:

Eyebrow : Always lost, unsafe, and out of place Side of eye : I don’t belong anywhere Under eye : I just don’t belong! Nose : I am a stranger in this world wherever I go Chin : Nobody wants me anyway Collarbone: Why am I here, what am I doing here? Under arm: This deep, old sadness Top of head: This constant yearning for a place where I belong

Eyebrow : This little kid inside me… Side of eye: …needs a home Under eye: This little kid inside me… Nose: …needs to belong Chin: This pain in my heart Collarbone: I am different, I don’t belong here Under arm: There must be something wrong with me Top of head: I want to go HOME

Take a deep breath.

Now, rate your global pain again on our scale 0 to 10.

If the intensity went down (or up) use Even though I STILL have/am/do… (adjust the grammar) as the new set-up phrase and go though the tapping sequence again. Repeat this process until you feel profound relief (an emotional shift), or as often as it feels right.

If your intensity did not budge at all (or the level gets “stuck” during the follow-up rounds) you have to get more specific.

If you were flooded with memories, thoughts, emotions, or body sensations while you were tapping, you already got more specific.

Since this script cannot be as personal as a private session, you have to adjust parts of it to your needs. The following sequence is a guideline, please fill in the blanks and extend it. There is no right or wrong when it comes to tapping. Often, out of the greatest mental and emotional mess, a gem (or a whole treasure chest) evolves. Trust the process.

Sometimes, you will release an issue in a jiffy. At other times, you have to do major excavation work.

KARATE CHOP: Even though I feel this …. (strong emotion like fear, desperation, sadness) I deeply and completely love and accept myself Even though I feel this emotion in my (body part like heart, throat, eyes), I love and appreciate my body Even though I have this memory of (give it a title like “Forgotten in the grocery store”), I allow myself to feel safe now. Eyebrow: This (emotion) Side of eye : This discomfort/pain in my (body part) Under eye : This memory of (title of memory) Nose : There is no place for me in this world Chin : I can never get over that Collarbone : It hurts too much Under arm : There is nothing and nobody I belong to Top of head : This deep yearning for a place where I belong

Continue with the specifics of your feelings, body sensations, beliefs, and memories.

What does this current emotional pain remind you of?

When did you feel that you don’t belong for the first time?

How did you feel generally as a child?

What specific situation comes up? Narrate the story.

Did the discomfort/pain in your body shift? Where is it now ?

What are your exact feelings now? Did they change?

Did another memory pop up?

Could you express your feelings as a child? If you did, what were the consequences? If you could not, how did you feel about that?

Continue to “dig” and follow the trail of your memories, thoughts, emotions, and body sensations. Talk it out, make notes, and tap until you get relief.

If you feel warm or dead tired, sigh, yawn, or get bored with the whole thing – those are good signs! Your energy is shifting.

Now you are ready for the last round:

KARATE CHOP: Even though a part of me still feels that I don’t belong, I choose to listen to the wiser part of me Even though I don’t know who I would be without this feeling, the truth is that this feeling is not who I really am Even though I am sensitive and vulnerable, I deeply and completely love and accept myself. Eyebrow : I give myself permission to let all that go now. Side of eye : I give the lost little child inside me a home Under eye : She (he) belongs with me Nose : The time for healing is now Chin : That was then and this is now Collarbone : I reclaim my sense of belonging Under arm : Separateness is an illusion Top of the head : Nobody can get lost in this world because we are all ONE Eyebrow : I let go of all this sadness and desperation now Side of eye : My life is joyful and connected Under eye : I am at home everywhere Nose : I feel safe and secure in my body Chin : I feel safe and secure with other people Collarbone : I feel safe and secure in Spirit Under arm : I trust the flow of life, I belong Top of the head : I am guided and protected wherever I am

Carna Zacharias-Miller is an EFT International Certified Advanced EFT practitioner in Tucson, Arizona. Her specialties are working with people who grew up in dysfunctional families, www.MissingMother.com , and introducing EFT into the dance community. Carna's new blog, www.sacredquestforlove , explores the spiritual side of emotions. You can also find her books on the site, The Way of the Ugly Duckling and, for dancers, It Takes Two To Tango .

From the EFTfree Archives , which are now a part of EFT International . Originally published Apr 13, 2014.

Samuel says

8 March, 2019 at 9:54 pm

Thank you. I believe I found this at the right time. You’re wonderful. I’m very grateful.

debbie wilson says

24 May, 2017 at 2:54 am

Thank you, this is so spot on! I am in my 50s and this sums up a lifetime of sadness and desperation, constantly moving every couple of years and searching…

Share Your Comments & Feedback Cancel reply

Contact, help & support.

Please use the Contact EFTi page to select which department you would like to reach.

EFT International John Greenway Building John Greenway Close Tiverton, Devon, EX16 6QF United Kingdom

EFT International (EFTi) is a not-for-profit Charitable Incorporated Organisation (CIO), registered in England and Wales, Charity number 1176538.

Our Mission

EFT International is dedicated to advancing and upholding exemplary standards for education, training, professional development, and the skillful and ethical application of EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques or "Tapping"). We are committed to supporting the growing body of evidence-based research into the efficacy of EFT, and are actively working to integrate EFT into the mainstream.

Quick Links

- Discover EFT

- EFT International Policies & Procedures

- EFT Practitioner Directory

- EFT International Volunteers

- Member Policies & FAQs

- Privacy Policy

Languages & Regions:

Privacy overview.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | 1 year | Records the default button state of the corresponding category & the status of CCPA. It works only in coordination with the primary cookie. |

| ts | 3 years | PayPal sets this cookie to enable secure transactions through PayPal. |

| ts_c | 3 years | PayPal sets this cookie to make safe payments through PayPal. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _gat | 1 minute | This cookie is installed by Google Universal Analytics to restrain request rate and thus limit the collection of data on high traffic sites. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AKA_MVT_ID | 10 minutes | No description available. |

Students’ Sense of Belonging Matters: Evidence from Three Studies

On Thursday, February 16, we hosted Dr. Maithreyi Gopalan to discuss her latest research on how students’ sense of belonging matters.

- Evidence has shown that in certain contexts, a student’s sense of belonging improves academic outcomes, increases continuing enrollment, and is protective for mental health. In some of the studies presented, these correlations were still present beyond the time frame of the analysis, suggesting that belonging might have a longitudinal effect.

- Providing a more adaptive interpretation of challenge seemed to help students in a belonging intervention make alternative and more adaptive attributions for their struggles, forestalling a potential negative impact on their sense of belonging.

Professor Gopalan began her talk by discussing how the need for “a sense of belonging” has been identified as a universal and fundamental human motivation in the field of psychology. John Bowlby, one of the first to conduct formal scientific research on belonging, examined the effects on children who had been separated from their parents during WWII (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). From his pioneering work, Bowlby and colleagues proposed that humans are driven to form lasting and meaningful interpersonal relationships, and the inability to meet this need results in loneliness and mental distress. Educational psychologists adapted the concept of belonging to indicate how students’ sense of fit with themselves and with their academic context can affect how they perceive whether they can thrive within it (Eccles & Midgley, 1989; Eccles & Roeser, 2011).

After providing this brief overview of what belonging means more broadly, Dr. Gopalan introduced the concept of “belonging uncertainty” pioneered by social psychologists Geoffrey Cohen and Gregory Walton at Stanford University (Walton & Cohen, 2007) to describe the uncertainty students might feel about their belonging when entering a new social and academic situation , which is most pronounced during times of transition (e.g., entering college). Research has shown that belonging uncertainty affects how students make sense of daily adversities, often interpreting negative events as evidence for why they do not belong. Belonging uncertainty may result in disengagement and poor academic outcomes. In contrast, a sense of belonging is associated with academic achievement, persistence in the course, major, and college (Walton & Cohen, 20011, Yeager & Walton, 2011). It is the concept of belonging uncertainty that is the focus of Dr. Gopalan’s presentation, with emphasis on the findings from the following key research questions:

- How do students’ sense of belonging in the first year correlate with academic persistence and outcomes at a national level?

- Can belonging interventions during the first semester of college lead to increased persistence and academic achievement in a diverse educational setting?

- How does a student’s sense of belonging amidst the COVID-19 pandemic correlate with mental health?

Study 1: College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A National Perspective (Gopalan & Brady, 2019)

Most research examining college students’ sense of belonging has come from studies looking at one or a few single four-year institutions. To examine how belonging differs across student identities and institutions, Professor Gopalan and colleagues looked at the responses from the only nationally representative survey of college students to date that had measured belonging. The Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS) (Dudley et al ., 2020) sampled first-time beginning college students from 4070 eligible two- and four-year institutions (N= 23, 750 students), surveyed during their first year and subsequently two years later.

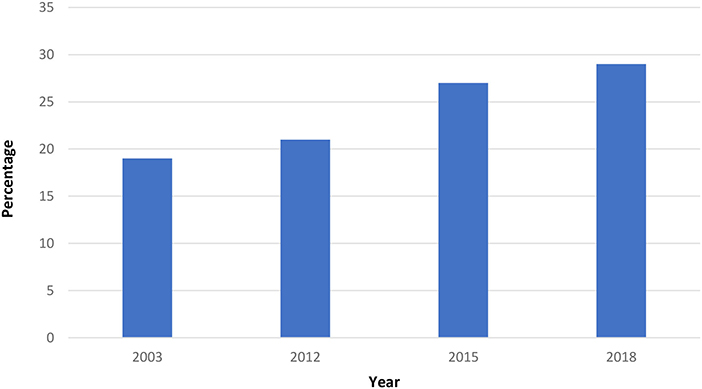

Professor Gopalan examined average measurements of belonging across institution type and student characteristics (Gopalan & Brady, 2019) and associations between belonging measurements and measurements of academic achievement, including GPA and persistence (continued enrollment), self-reported mental health, and self-reported use of campus services. The results, Dr. Gopalan explained, were striking: underrepresented racial and ethnic minority students (URMs) and first-generation/low-income students (FGLIs) reported a lower sense of belonging in four-year colleges than their non-URM and non-FGLI counterparts. 1 Importantly, they also found that having a greater sense of belonging is associated with higher academic performance, persistence, and is protective for mental health in year three of students’ undergraduate trajectory, suggesting that belonging might have a longitudinal effect (Gopalan & Brady, 2019). These findings were consistent with previous results from smaller studies involving single institutions. Sense of belonging is important not just in specific institutions but nationally, and social identity and context matter . One practical and policy-driven takeaway from this study is that only one national data set currently measures students’ sense of belonging using a single item. More robust measurements and large data sets might reveal additional insights into the importance of belonging for students’ educational experiences.

1 At two-year colleges, first-year belonging is not associated with persistence, engagement, or mental health. This suggests that belonging may function differently in two-year settings. More work is ongoing to try to understand the context that might be driving the difference. (Deil-Amen, 2011).

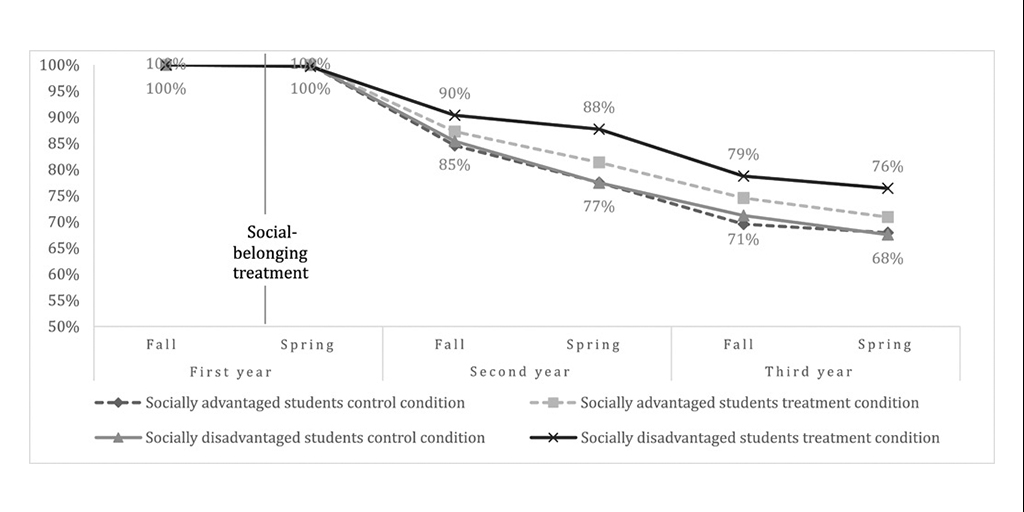

Study 2: A customized belonging intervention improves retention of socially disadvantaged students at a broad-access university (Murphy et al ., 2020)

Professor Gopalan and colleagues wanted to understand how to adapt existing belonging interventions to different educational contexts and dig deeper into underlying psychological processes underpinning belonging uncertainty. Because previous social-belonging interventions were conducted in well-resourced private or public institutions, Professor Gopalan was interested in examining whether the positive effects of belonging interventions could be extended to a broader-access context (context matters as not all extensions of belonging interventions have been shown to reproduce persistent changes in enrollment and academic outcomes). For this purpose, the traditional belonging interventions were customized for a four-year, Hispanic-serving public university with an 85% commuter enrollment using focus groups and surveys. Based on prior research, belonging interventions provide an adaptive lay theory for why students encounter challenges during transition times (Yeager et al ., 2016). Students, particularly those with little knowledge of how college works or those who have experienced discrimination, or are aware of negative stereotypes about their social group, may make global interpretations of why college can be challenging and may even associate challenges as evidence that they and students like them don’t belong. With belonging interventions, the lay theory provided to students aims to frame the experience of challenge in more adaptive ways—challenge and adversity are typical experiences, particularly during transitional moments, and should be expected; adapting academically and socially takes time—students will be more likely to persist, seek out campus resources and develop social relationships.

- They acknowledge that challenges are expected during transitions and that these are varied.

- They communicate to students that most students, including students from non-minority groups, experience similar challenges and feelings about them.

- They communicate that belonging is a process that takes time and tends to increase over time

- They use student examples of challenges and resolutions.

The Intervention

All students in the first-year writing class were randomly assigned to either the belonging group or an active control group. The intervention was provided to first-year students in their writing class and consisted of a reading and writing assignment about social and academic belonging. The control group was given the same assignment but with a different topic, study skills. In the intervention group, students read several stories from a racially diverse set of upper-level students who reflected on the challenges of making friends and adjusting to a new academic context. The hypothetical students reflected on the strategies they used, the resources they accessed, and how the challenge dissipated over time. After the reading exercise, the students in the intervention group were instructed to write about how the readings echoed their own first-year experiences. Then, they were asked to write a letter to future students who might question their belonging during their transition to college. Research has shown that written reflections help students internalize the main messages of the belonging intervention (Yeager & Walton, 2011).

Similar to previously published belonging interventions, results in persistence and academic achievement were significant for minoritized groups in the belonging cohort:

- Persistence. Compared to the control group, continuous enrollment for URM & FGLI students increased by 10% one year after and 9% two years after the intervention.

- Performance. The non-cumulative GPA from the URM & FGLI students increased by 0.19 points the semester immediately following the intervention and by 0.11 over the next two years compared to students in the control group.

Immediately following the intervention, a selected sub-sample of students in both conditions was invited to take a daily diary survey for nine consecutive days. The daily diary survey assessed students’ daily positive and negative academic and social experiences (students were asked to report and describe three negative and three positive events that they faced daily and to rate how positive and negative the events were), as well as their daily sense of social and academic belonging. The daily-diary assignment revealed another interesting finding: the intervention did not change the overall perception of negative events. URM & FGLI students in both groups had a statistically similar daily-adversity index and reported the same number of daily adverse events on average. However, there was no connection between the adversity index and sense of belonging for students in the belonging cohort. In contrast, students in the control group evidenced a negative correlation between daily adversities and belonging: “the greater adversity disadvantaged students experienced on a day, the lower their sense of social and academic fit” (Murphy et al ., 2020).

Providing a more adaptive interpretation of challenge seemed to help students in the belonging condition make alternative and more adaptive attributions for their struggles that did not connect to their sense of belonging. A follow-up survey one year after the intervention showed that minoritized students in the belonging intervention continued to report a higher sense of belonging in comparison to their counterparts in the control group.

Study 3: College Student’s Sense of Belonging and Mental Health Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic (Gopalan et al ., 2022)

Dr. Gopalan presented the third study, which turned out to provide a unique opportunity to assess whether sense of belonging had predictive effects on mental health. In the fall of 2019, researchers sent a survey to students at a large, multicampus Northeastern public university called the College Relationship and Experience survey (CORE), which included two questions about belonging, among other items. In the Spring of 2020, after students were sent home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a variation of the same survey was sent to students who had taken the CORE survey. After controlling for pre-COVID depression and anxiety, Dr. Gopolan and colleagues found that students who reported a higher sense of belonging in the fall of 2019 had lower rates of depression and anxiety midst-COVID pandemic , with the effects on depression more strongly predictive than those for anxiety. The correlation between a lower sense of belonging and higher rates of depression and anxiety was also found to be strongest for first-year students, who had little time during their first year to build community and adjust to college before the pandemic hit.

Dr. Gopalan concluded with some practical advice for instructors: “Stop telling students they belong, show them instead that they belong,” citing a recent op-ed from Greg Walton . We do this by modeling the idea that belonging is a process that takes time and by communicating to students that they are not alone , which can be done through sharing our own experiences with belonging, and by allowing students space to hear the experiences of their peers and learn from one another.

- Classroom Practices Library which includes Overview: Effective Social Belonging Messages are more.

- The Project for Education Research That Scales (PERTS) : a free belonging intervention for four-year colleges and universities.

- Research library on belonging

- Article on Structures for Belonging: A Synthesis of Research on Belonging-Supportive Learning Environments

- “Stop telling students ‘You Belong!’”

- Everyone is talking about belonging: What does it really mean?

- Post-secondary

- Academic Belonging : introduction to the concept and practices that support it.

- Flipping Failure : a campus-wide initiative to help students feel less alone by hearing stories about how their peers coped with academic challenges

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117 (3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Deil-Amen, R. (2011). Socio-academic integrative moments: Rethinking academic and social integration among two-year college students in career-related programs. The Journal of Higher Education , 82(1), 54-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2011.11779085

Dudley, K., Caperton, S.A., and Smith Ritchie, N. (2020). 2012 Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS:12) Student Records Collection Research Data File Documentation (NCES 2021-524). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved 2/27/2023 from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid-2021524

Eccles, J. S., & Midgley, C. (1989). Stage/Environment Fit: Developmentally Appropriate Classrooms for Early Adolescence. In R. E. Ames, & Ames, C. (Eds.), Research on Motivation in Education , 3, 139-186. New York: Academic Press.

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21 (1), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x

Gopalan, M., & Brady, S. T. (2020). College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A National Perspective. Educational Researcher , 49(2), 134–137. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19897622

Gopalan, M., Linden-Carmichael, A. Lanza, S. (2022). College Students’ Sense of Belonging and Mental Health Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic, Journal of Adolescent Health , 70(2), 228-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.010

Murphy, M.C., Gopalan, M., Carter, E. R., Emerson, K. T. U., Bottoms, B. L., and Walton, G.M., (2020). A customized belonging intervention improves retention of socially disadvantaged students at a broad-access university Science Advances, 6(29). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aba4677

Walton, & Cohen. (2007). A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82

Walton, G.M., & Cohen, G.L. (2011). A Brief Social-Belonging Intervention Improves Academic and Health Outcomes of Minority Students. Science, 331(6023), 1447-1451. DOI: 10.1126/science.1198364